UNFAIR

ADVANTAGE

Our Steel Pumpers. Your Steel Nerves. Fire doesn’t always fight fair. And you deserve every advantage you can get. You deserve an E-ONE Stainless Steel Pumper. The body is forged entirely of stainless steel including hinged doors and the sub-frame, providing the unmatched performance and durability you can count on with every call.

The bottom line: with E-ONE and your crew, fire doesn’t stand a chance.

10

EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS

As Laura King reports, a largescale mock disaster at the Bruce Power nuclear generating station and surrounding communities gave volunteer firefighters with the Saugeen Shores Fire Department an opportunity to train and learn from the province’s top special rescue teams, to work with dozens of agencies and to understand the magnitude of such an emergency.

14

SiMulAtiNG thE fiRE GRouND

The emphasis on prevention has resulted in fewer fires, and this has led to limited learning opportunities for future fireservice leaders. This lack of experience was headed toward severe inconsistency on the fire ground in Halifax, but, as John Giggey reports, a new command training program has led to the development of fire-tested operating guidelines for the city.

28

DiSAStER RESPoNSE

Often times, the first responders to a scene are not firefighters or emergency personnel, but regular people. The fire department in Amsterdam in the Netherlands has adopted new procedures to make use of ordinary citizens on scene and, as Joseph Scanlon and Jelle Groenendaal write, those in the Canadian fire service should follow suit.

By L AURA K ING Editor lking@annexweb.com

WAre we really prepared? comment

e didn’t plan to focus on emergency preparedness in this issue but a confluence of events made the topic an obvious choice.

In October, I sat in on a seminar in Burlington, Ont., called The Public Health of Emergency Preparedness, hosted by Public Safety 411 (www.publicsafety411.ca). The final presenter was Joe Scanlon, who has done considerable research on the role of ordinary people in masscasualty disasters. Scanlon also happens to be the journalism professor who taught me to chase fire trucks and write news stories; he has since developed considerable expertise in emergency response. Scanlon’s story on page 28 about what the Amsterdam-Amstelland Fire Department is doing to incorporate ordinary people into disaster response is compelling.

earthquake off the British Columbia coast. The next night on CBC’s The National, I watched Wendy Mesley quiz a provincial emergency response spokesperson about the delay in informing residents of a possible tsunami – almost an hour after U.S. authorities sent out their warning. At first, I was annoyed that Mesley didn’t have a better understanding of the protocol for such things, but I still haven’t seen a reasonable explanation for the less-than-rapid response; the standard line was that people in the quake zone knew to get to higher ground. Clearly there’s room for improvement.

oN thE CovER

Fire, police and dozens of other agencies participated in a mock disaster exercise on Oct. 18. See story page 10.

Two weeks later, I was part of the media contingent at Huron Challenge IV – Exercise Trillium Resolve in Port Elgin and Saugeen Shores, Ont., a massive mock-disaster exercise that involved a tornado, a nuclear generating station, hundreds of responders, more than 50 agencies and about nine months of planning.

Reporters weren’t allowed near Bruce Power but we were given access to its new emergency operations centre and witnessed several evolutions in nearby municipalities by the Ontario Provincial Police special response teams and the Saugeen Shores Fire Department. Our story on page 10 focuses on the magnitude of the event, the response, and the lessons learned.

Shortly thereafter, news of Hurricane Sandy hit. But before Sandy made landfall, my e-mail and Twitter feed lit up with news of the

Then came Sandy, the inability of responders to reach people in some areas within the 72 hours for which North Americans have been programmed to be self sufficient, and the ensuing head scratching over that message.

Interestingly, a Toronto Sun columnist ranted in the run-up to Hurricane Sandy about the Big Brother-like role of government agencies that tell people to evacuate or stock up on canned goods and batteries. The column was never posted online – likely for fear by editors that the ensuing barrage of vitriol from first responders would crash the system.

As Peter Sells notes in his Flashpoint column on page 38, how anyone prepares for emergencies should depend on geography and common sense. We can’t make people buy batteries. But as the researchers in Amsterdam and the responders in Saugeen Shores know, responders can learn from their peers and continuously re-evaluate emergency plans. We hope this issue of Fire Fighting in Canada helps you do that.

ESTABLISHED 1957 December 2012 VOL. 56 NO. 8

EDITOR LAurA KiNG lking@annexweb.com 289-259-8077

ASSISTANT EDITOR OLiViA DOrAZiO odorazio@annexweb.com 905-713-4338

EDITOR EMERITUS DON GLENDiNNiNG

ADVERTISING MANAGER CATHEriNE CONNOLLY cconnolly@annexweb.com 888-599-2228 ext. 253

SALES ASSISTANT BArB COMEr bcomer@annexweb.com 519-429-5176 888-599-2228 ext. 235

MEDIA DESIGNER KELLi KrAMEr kkramer@annexweb.com

GROUP PUBLISHER MArTiN MCANuLTY fire@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT MiKE FrEDEriCKS mfredericks@annexweb.com

PuBLiCATiON MAiL AGrEEMENT #40065710 rETurN uNDELiVErABLE CANADiAN ADDrESSES TO CirCuLATiON DEPT.

P.O. Box 530, SiMCOE, ON N3Y 4N5

e-mail: subscribe@firefightingincanada.ca

Printed in Canada iSSN 0015–2595

CIRCULATION

e-mail: subscribe@firefightingincanada.ca

Tel: 866-790-6070 ext. 206

Fax: 877-624-1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530 Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Canada – 1 Year - $24.00

(with GST $25.20, with HST/QST $27.12) (GST - #867172652rT0001)

uSA – 1 Year $40.00 uSD

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Periodical Fund (CPF) for our publishing activities.

Occasionally, Fire Fighting in Canada will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. if you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission ©2012 Annex Publishing & Printing inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

www.firefightingincanada.com

Photo by laura king

across canada: Regional news briefs statIontostatIon

New Wasaga Beach station boosts department’s visibility

Construction of the new fire station in Wasaga Beach, Ont., started in November 2011.

Less than one year later, on Sept. 6, 14 full-time firefighters and 20 volunteer firefighters of the Wasaga Beach Fire Department moved out of their old hall and into this new one.

The 1,394-square-metre (15,000-square-foot) station came in on its $3.3-million budget and replaces the old, 465-square-metre (5,000-square-foot) Station 1. Wasaga Beach’s other fire hall, Station 2, located in the western end of the town, remains open.

“We had outgrown the previous station,” Chief Michael McWilliam said.

“It was built in 1967, so it was 45 years old. When it was built, it wasn’t designed to be a full-time fire station. We made it work for a number of years, but [a new station] was overdue.”

The new station offers significant upgrades, in addition to sheer size. The old station

had space for just three vehicles, but the new station has four truck bays, each of which are two-trucks deep and open to drive through. The department added a training tower, which doubles as a space to hang hoselines to dry, and a training classroom.

“In the old station, we’d pull all the trucks out of the bay, and we’d train there – set up a few tables and a projector on top of a toolbox,” McWilliam said.

The station also features new shower facilities, locker rooms, a fitness room with new workout equipment, a new compressor and fill station for the SCBA, a board room, a meeting room, office space and lots of good storage space.

But one of the most significant improvements that the new station brings is its location. The old station was located in the heart of the town’s popular beach area, which, during the summer months, is often crowded with

the brass pole:

promotions & appointments

JIM WISHLOVE has been appointed assistant deputy fire chief for the New Westminster Fire and rescue Service in British Columbia. He has more than 23 years of service with the richmond Fire and rescue Service, where he served as a firefighter, company officer, training officer and deputy chief of fire prevention and staff development.

STEPHEN GAMBLE, fire chief for the township of Langley, B.C., has been elected president of the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs. He has served as the CAFC’s first vice president and

tourists. McWilliam said this made it difficult to reach, and be accessible to, the rest of the community.

“We moved the station away from the beach area,” McWilliam said. “It became difficult to respond because of the congestion during the summer months.

“We’re more visible to

has acted as an adjunct instructor with the Justice institute of B.C.

LARRy BRASSARD, a 37-year veteran of the Ontario fire service, has been appointed fire chief for the town of Gravenhurst. Brassard, who retired from the Waterloo Fire Department in October, was formerly the chief in Milton, Ont.

JAMES WALL is the new chief of King Fire and Emergency Services in Ontario. The 25-year

residents now. Before we were tucked into that beach area that a lot of residents wouldn’t go to,” he continued.

“I think the more visible a fire department is, the better. It’s a reminder for residents to check their smoke alarms; it’s a reminder [to be] fire safe.”

– Olivia D’Orazio

veteran began his full-time career in richmond Hill in 1989, and in 2011 was awarded the Paul Jackson Memorial Award for outstanding and selfless commitment to the fire service.

The new station in Wasaga Beach, Ont., is located closer to the residential areas of the town, and away from the busy beach strip that many residents don’t visit.

Richmond Hill achieves LEED standards with new station

Richmond Hill Fire and Emergency Services in Ontario opened a new station in the northern region of the town in September.

Fire Chief Steve Kraft said the new station was built in response to growth in the area.

“That area over the last couple of years has been built up,” Kraft said. “So the response times were the main priority; so we could get to an incident in the appropriate amount of time.”

As with anything new, Kraft said, this station –which measures 836 square metres (9,000 square feet) – is better equipped with technology. The station was built to a silver Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standard, is

fully backed up in the event of a power failure and houses a cascade system for filling SCBA bottles and a bunkergear washer.

“All the rainwater is captured in a cistern,” Kraft said “So we use that water to wash the fire trucks.

Environmentally, [the station] is definitely more friendly.”

Additionally, the station features a stand-alone gym and training room for the 16 new firefighters the town hired. Another four firefighters will be hired next year to complete the process of filling out the new station, which also included the purchase of a new pumperrescue truck with hydraulic rescue equipment.

The station, which cost

by

$2 million to build, is also equipped with a sprinkler system. As fire chiefs across the country push for residential sprinklers, Kraft said it’s

important for the department to lead by example.

“It really is a state-of-theart fire station,” he said. – Olivia D’Orazio

Globe provides volunteer department with new gear

In celebration of its 125th anniversary, Globe Manufacturing has given 125 sets of bunker gear to volunteer firefighters in Canada and the United States. Volunteer fire departments across Canada and the U.S. registered for the Globe giveaway in the hopes of being chosen as a gear recipient. One Canadian department – the Moose Creek Fire Department in Moose Creek, Ont. –

received 12 sets of gear for its volunteers.

“Pretty much all of our suits were from 1984 to 1992,” said District Chief Nicholas Forgues, “so they were all close to 30 years old.

“We were in need of new ones; we thought we had a shot at [being chosen to receive] some gear, so we decided to register.”

The 19 volunteer mem-

bers of the Moose Creek Fire Department serve a population of about 2,500. The department’s service area includes a large agricultural community, an environmental plant, an eco tire recovery and shredding facility, and a portion of the two major highways.

Receiving the bunker pants and jackets is a huge relief and reduces the strain on the department’s budget, Forgues

said, leaving a financial surplus that can be put to good use in other places.

“Twelve suits like that would have taken probably six to seven years to replace, so that’s a huge relief for us,” he said.

“With the money we’re saving, we’re probably going to try to upgrade SCBAs and other equipment that we’re in need of.”

– Olivia D’Orazio

LORNE McNEICE, fire chief for the Gravenhurst Fire Department in Ontario, retired Oct. 14, after serving 40 years on the Gravenhurst department. McNeice started his career as a volunteer firefighter in 1972, before being named volunteer chief in 1985.

JOHN MacDONALD, the

first fire chief for the Leeds and Thousand island Fire Department in Ontario, passed away in March. MacDonald was instrumental in the creation of the department, and served as its chief from 1958 to 1972.

DAVID CARTMEL died Sept. 3 at the age of 52. A firefighter for more than 30 years, Cartmel was appointed captain of the Brantford Fire Department in Ontario in 2006.

RON CLARKE, 76, died Sept. 7 of a sudden heart attack shortly after returning from a fire call. Clarke, a member of the Wembley Fire Department in Alberta, had acted as a fire chief from 1973 to 1981, before stepping down to deputy chief.

GORDON BREEN, retired fire chief, died Sept. 2. He served as a firefighter for the Owen Sound Fire Department in Ontario for 38 years, and founded the Grey County Mutual Aid Fire Service Association.

HAWTIN, district chief for the Brock Township Fire Department in Ontario, died suddenly on Sept. 28. He joined the department in 1972 at the Beaverton Fire Station.

TOM

Richmond Hill Fire and Emergency Services opened this new station in the northern region of the town in response to population growth in the area.

Photo

laura king

statIontostatIon

br I gade ne W s: From stations across Canada

The BRACEBRIDGE FIRE DEPARTMENT in Ontario, under Chief Murray Medley, took delivery in August of a Dependable Emergency Vehicles-built pumper. Built on an International 7400 chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a 330-hp Maxxforce 9 engine, the truck is equipped with a 1,500-IGPM Hale DSD pump, a 1,000-gallon co-poly water tank, a Hale FoamLogix foam system, a five-kilowatt Honda generator and two 500-watt FRC telescopic lights.

The SWANSEA POINT FIRE DEPARTMENT in British Columbia, under Chief Mike Melnichuk, took delivery in August of a Hub Fire Engines & Equipment-built tanker. Built on a Freightliner M2 chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a 330-hp Cummins ISC engine, the tanker is equipped with a 19-hp CET portable pump, a 1,600-gallon co-poly water tank, a FoamPro 1600 foam system, a Whelen LED light package, Amdor roll-up doors and custom Porta-tank storage.

The SWAMPy CREEK TRIBAL COUNCIL in Lynn Lake, Man., took delivery in June of a Fort Garry Fire Trucks-built pumper. Built on an International 7400 chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a 300-hp Maxxforce DT engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale Q-Flo pump and an 800-gallon co-poly water tank.

TABER EMERGENCy SERVICES in Alberta under Chief Michael Bos, took delivery in January of a Fort Garry Fire Trucks-built pumper. Built on an International 7400 chassis and powered by an Allison 3500 EVS transmission and a 300-hp Maxxforce DT engine, the truck is equipped with a 1,050-IGPM Darley PSP pump, a FoamPro 2001 foam system, an 800-gallon co-poly water tank, pump and roll capabilities, an enclosed heated pump compartment and a front bumper turret.

The TOWN OF DRUMHELLER FIRE DEPARTMENT in Alberta, under Chief Bill Bachynski, took delivery in May of a Fort Garry Fire Trucks-built emergency rescue pumper. Built on a Freightliner M2 chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a 350hp Cummins ISC engine, the truck is equipped with a 1,050-IGPM Darley PSP pump, an 800-gallon pro-poly water tank, a FoamPro 2001 foam system, a TFT front bumper, a 12-volt Wilbur LED light tower and Speedlay hose beds.

The PORT MCNEILL VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPARTMENT in British Columbia, under Chief Larry Bartlett, took delivery in August of a Hub Fire Engines & Equipment-built rescue truck. Built on a Ford F-350 chassis, the truck is equipped with a Whelen LED light package and a Warn M12000 hidden winch kit.

BRACEBRIDGE FIRE DEPARTMENT

SWANSEA POINT FIRE DEPARTMENT

TOWN OF DRUMHELLER FIRE DEPARTMENT

SWAMPy CREEK TRIBAL COUNCIL

PORT MCNEILL VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPARTMENT

TABER EMERGENCy SERVICES

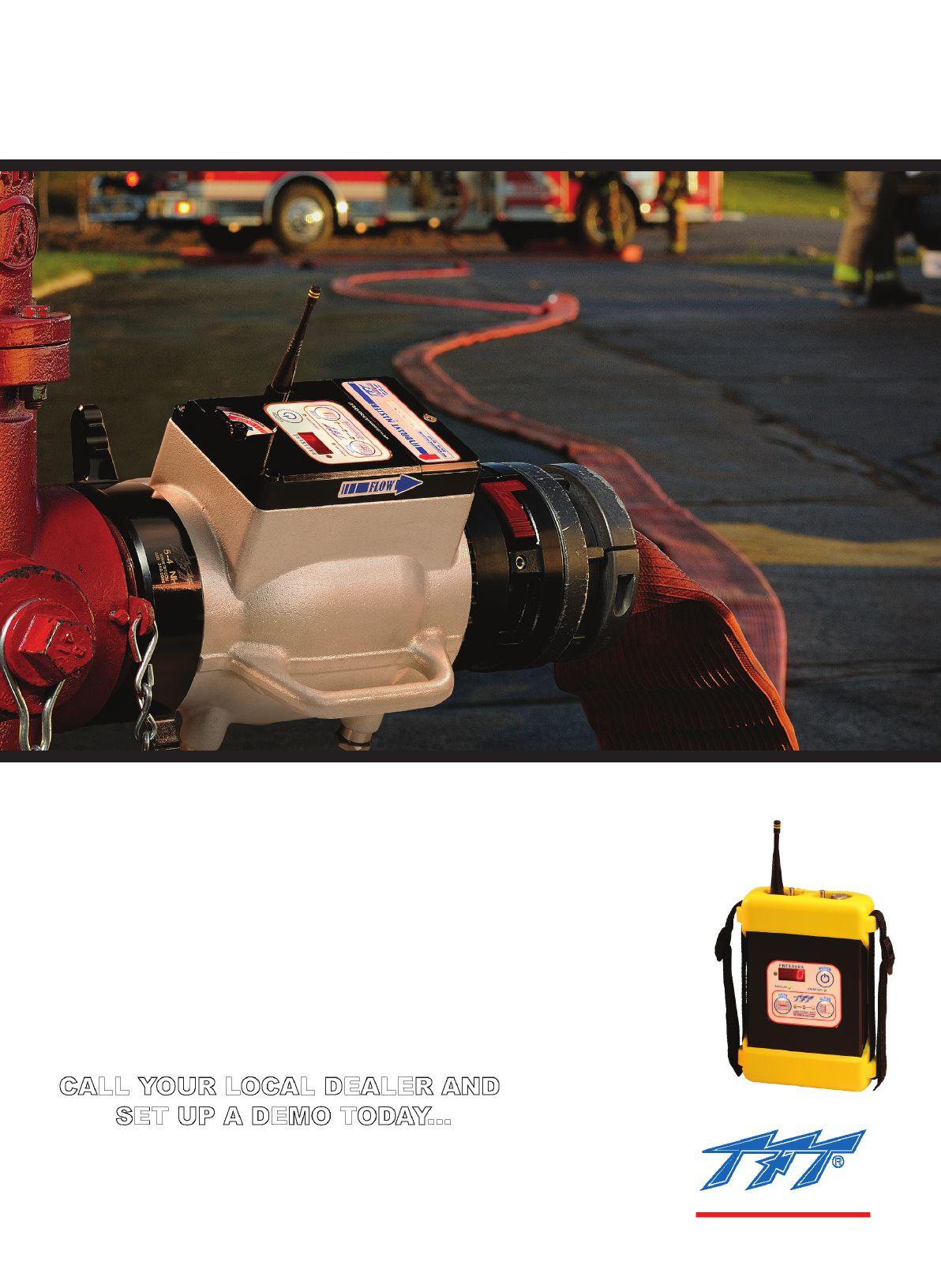

Remotely Control Your Water Supply…

Maximize the effectiveness of your crews with TFT’s Hydrant Master remotely controlled hydrant valve. Integrating reliable 900 MHz communications, pre-programmed slow open and close operations, and a digital pressure display at the pumper, this valve is the perfect tool for any pump operator establishing a hydrant water flow operation with limited staffing.

To learn more about how you can improve both effectiveness and safety during initial attack operations, contact your local TFT dealer today.

emergency preparedness

Mock-disaster exercise tests plans, agencies and co-operation and gives volunteer department training opportunities with specialized teams

By Laura King

saugeen Shores, Ont. – In 2009, the municipality of Saugeen Shores on Lake Huron was named a host municipality to the Bruce Power nuclear generating station.

That designation carries massive responsibility for Chief Phil Eagleson and the 58 volunteer members of the Saugeen Shores Fire Department, primarily planning for a nuclear emergency. That responsibility became much more real after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan in March 2011.

“In the wake of Fukushima we knew we had to do more,” says Eagleson. “We had to provide the highest level of emergency planning and preparedness we could for the citizens of Saugeen Shores as well as for citizens surrounding the nuclear plant.”

The Fukushima disaster – equipment failures, nuclear meltdowns, and releases of radioactive materials after an earthquake and tsunami – was the largest nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986.

l eft: Members of the Saugeen Shores Fire Department participate in rescue operations headed by the Ontario Provincial Police special teams during Huron Challenge-Trillium Resolve in October.

a bove : Saugeen Shores Fire Chief Phil Eagleson’s department played a significant role in the mock disaster that affected the Bruce Power nuclear generating station and surrounding communities.

The Bruce A and B nuclear generating plants near Kincardine, Ont., provide 30.1 per cent of the province’s power. Bruce Power regularly runs emergency drills but a mock disaster in midOctober that included 70 municipal, provincial and federal agencies, and 1,000 participants, was the largest to date.

The basis for the exercise at Bruce Power was a tornado similar in strength to the one that hit Goderich, Ont., in August 2011. The tornado resulted in a power loss at Bruce Power. Although the Bruce Power site was closed to reporters and spectators, the Saugeen Shores Fire Department partnered with the Ontario Provincial Police and other agencies to run a series of evolutions over five days that gave its members access to myriad specialties including high-angle and technical rescue and hazmat operations.

Eagleson, who was honoured in 2011 by the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs with the VFIS Award for improving recruitment and retention in his department, says the exercise – called Huron Challenge-

Trillium Resolve – gave firefighters access to specialized skills and operations taught by highly trained experts.

“When we were approached by Emergency Management Ontario and Bruce Power we said yes to the idea of the Huron Challenge,” Eagleson says.

“At the time, it definitely wasn’t an event; it was more a series of planning principles. And it has snowballed from there; we started with one event which led to three more which led to us sort of being the poster child for the whole exercise and we enjoyed it. We definitely got more out of it than any other municipality as most of the events were centred around Saugeen Shores. We met more players, interacted with more agencies and we really used it as a learning experience to network with other groups.”

Saugeen Shores is a mutual-aid partner for Bruce Power, but after Fukushima Bruce Power’s objective was to prove self-sufficiency. Bruce Power Fire Chief Brian Cumming says the facility’s new off-site emergency management centre – with its own AM radio frequency for communicating with area residents – its five new 3,000-U.S.-gallons-per-minute pumpers that were used to cool the reactors, and upgraded protocols between fire and security, all contributed to the ability to control the incident.

“The scope was a worst-case situation where there was no power and the infrastructure was damaged,” Cumming says.

“There were casualties not only at the nuclear plant but also at the site – there were injuries to people and damage to property. The whole pretence was to set up a command crew so that they would have to prioritize and deal with multiple tasks that the same time.”

The four Spartan trucks, built by Dependable in Brampton, Ont., pumped water for 24 hours to cool the reactors. There was no release of radioactive material.

“Really the intent was to demonstrate our capability to deploy emergency mitigating equipment,” Cumming says, “including portable pumps, which were our fire trucks, and to be able to sustain the operations. We ran the trucks for 24 hours to demonstrate that we had the ability to sustain operation. The trucks have 3,000-U.S.imperial-gallons-per-minute pumps – triple what municipalities have for their apparatuses. From a technical standpoint, all the discharges are flow metered so we know exactly what the flow and pressure is.

Photos by laura king

KOCHEK® LDH and Rural Systems Your Single Source of Water Supply

“Really the concept is to take a piece of emergency equipment that people are very familiar with, and, in extreme conditions, instinctively know how to operate this equipment – taking standard firefighting equipment and knowing how to deploy it in a different scenario.”

Aside from Bruce Power, there were 36 venues across 10,000 square kilometres at which municipalities, fire departments, special teams and other provincial and federal response agencies participated in drills. In Saugeen Shores – which comprises Port Elgin, Southampton and Saugeen Township – the five-day exercise started on Monday, Oct. 15, with high winds and flooding.

“Monday morning we experienced torrential rain and heavy wind in Saugeen Shores, which led to flooding and the damage of one building,” Eagleson says. “Monday afternoon, there was more extreme wind and a building was damaged. We responded quickly to the scene, and called for assistance from OPP UCRT team, because the building had collapsed and we could not reach the trapped victims.”

The scenario called for five people to be trapped in the building, a two-storey home on a suburban street in Saugeen Shores. The OPP’s Urban CBRNE Response Team (UCRT)) shored up the structure and worked with Saugeen Shores firefighters to stabilize the house then free patients from the basement using technical-rescue and high-angle rescue techniques, and from the attic using the aerial ladder.

While at the damaged home, responders discovered a clandestine lab on the grounds; OPP bomb technicians and hazmat technicians were called in to diffuse and decontaminate the scene.

“Firefighters were on standby for the duration of the exercise,” Eagleson says. “For four to five days, fire crews with fire pumpers looked after decontamination of victims and rescuers and provided standby support to rescue ops.

“The UCRT team was extremely welcoming and inviting to the volunteer firefighters in all of their operations – they never once completed an evolution without putting their arm around two or three firefighters and saying this is what we’re doing and how and why, and teaching them some tricks. In the dozens of evolutions they did at the house – inside, on the roof – they always involved the firefighters to show them why, where, how. It gave us as fire people a better appreciation for the UCRT team’s capabilities and how they perform their jobs.”

Through the entire exercise, the incident management system (IMS) was in place and the fire captain on scene was the

incident commander.

“There was never any friction between the OPP and fire,” Eagleson says. “The OPP led the rescue operations but the overall command of the scene remained with fire.

Bruce Power’s Frank Saunders, the vicepresident of nuclear oversight and regulatory affairs, says IMS was chosen because of its prevalence in North America.

“If you look at Fukushima or some of the big disasters in the Unites States, the first thing you realize is that an accident doesn’t happen in isolation; if you’ve got a big natural event, if it affects your nuclear plant it’s going to affect other things too, so we were looking for a system that’s going to work for everyone.

“The incident management system is the method of choice in the U.S. and in Ontario, so when you looked at it, that’s what it’s designed for; that was really the decision – something that could handle a broad set of situations. We also wanted something that would match with the province and municipalities and wasn’t something that they had to learn.”

More than 30 of Saugeen Shores’ volunteer firefighters were involved in Huron Challenge-Trillium Resolve; some were unavailable during daytime work hours but all members participated in some aspects of the exercise, from superior tanker-shuttle training to tours of the OPP base camp.

During the exercise, just as the Saugeen Shores Fire Department responded to the damaged home, the tornado hit Bruce Power and knocked out power to the municipality, which opened its emergency operations centre (EOC).

“And,” says Eagleson, “we were informed that there may be a risk to the nuclear plant – we weren’t given any more details then. We experienced more flooding and severe weather-related incidents in Saugeen Shores, at which point Public Safety Canada contacted us and asked for an area where they could set up their remote monitoring equipment. They arrived quickly with a helicopter and started to set up for radiation detection in the environment.”

Saugeen Memorial Hospital activated its emergency plan and set up a decontamination unit but was overwhelmed with casualties from the storm and requested help from the provincial Emergency Medical Assistance Team, or EMAT. Later, the Saugeen Shores Fire Department was informed through the provincial emergency operations centre that Bruce Power had requested it set up an emergency worker centre, or EWC, at the Southampton fire

Continued on page 36

Durable

Forged Storz Couplings and Hose Valves

Storz Adapters

Durable Rubber Covered LDH Hose 4” or 5”, Meets N F PA 19 61

Born bold.

If you’ve always been a fighter, only Dräger will do.

Dräger equipment isn’t for everyone. It’s for people who have expected nothing but the best of themselves from the very beginning. When expectations are this high, only optimum fire equipment can rise to the occasion. Dräger makes equipment bold achievers can have confidence in. Our integrated portfolio revolutionizes firefighting technology with streamlined components that work together as one. The result: power to perform at your personal best.

s imulating the fire ground

Command training increases knowledge, safety and consistency for Halifax department

By JoHn giggey

You learn from every fire.

That’s an old adage in the fire service, but there are two problems with that. First, the only people who learned from that fire were the members who fought it. Second, there are far fewer fires than there used to be. That’s a good thing, but it also means fewer learning opportunities, and that lack of knowledge and experience can show on the fire ground.

Brian Gray, deputy chief of operations with Halifax Regional Fire, noticed the problem a few years ago while still a platoon chief on the street: there was no consistency.

“In running promotional routines, sometimes the level of experience in running a fire

ground was nowhere near where I thought it should be,” he says. “And there was no consistency in the way we managed fires.

“Like many departments, we used to rely a lot on mentoring – senior officers teaching junior officers. If you were fortunate enough to have a good mentor then you would likely become a good officer. But if you had a poor mentor, well, you’re still going to become like your teacher.”

Gray wanted to bring it all together.

“I wanted some predictability as to what I would expect to see as a platoon chief when I come in and take command of a fire after the first incoming crews have arrived and set up.”

He took the idea of an officer-training

by

Brian Gray, deputy chief of operations, in the control room of the command training simulator at Station 7 of Halifax Regional Fire.

Photo

John g iggey

You protect the public

Let us heLp protect you

For your cleaning, decontamination, inspection, testing, repair and record keeping of your firefighter’s protective clothing... we have you covered!

• 24/7 access to Firetrack®, the online data base that provides you with complete details of your C&M Program with FSM. We do the work for you!

• ETL Verified

• ISO 9001 Registered

• Fast turnaround

• Complete Bunker Gear Rental Program – Toronto Location

Ontario (toronto) 1-888-731-7377

Western canada (calgary) 1-403-279-5095

Quebec (Montreal) 1-514-312-3708

Mid-West USa (Detroit, Mi) 1-866-877-6688

centre upstairs and secured a budget of $40,000. Then he put together his team: himself, Training Chief (now Division Commander) Chuck Bezanson and Steve Nearing, division chief of communications and technology.

The team was leaning toward a computerized virtual fire simulation system. The Phoenix Fire Department has been a leader in that field, so the team visited the Phoenix command training centre, meeting with project manager Don Abbott (recently retired). The team came back convinced to go with a similar program.

On their return to Halifax, team members began reviewing the software that was available.

As it turns out, training officers Andrew Bednarz and Vince Conrad had become familiar with the 50-hour Blue Card incident command certification program and had already completed it online. When the training officers brought this to the attention of Gray and his team, the decision was made to go with Blue Card.

Blue Card is based on Fire Command, a fire officer training textbook developed by retired Phoenix fire chief Alan Brunacini, and was developed by Brunacini and his sons, John and Nick.

An empty classroom at Station 7, which also includes a large training ground, was refurbished and cubicles were added. Computers and the necessary software were purchased and soon the command training centre was in place – and under budget. Bednarz loaded the system and he remains keeper of the centre, so to speak.

The payoffs started long before the new training program even got off the ground. Just setting up the simulator required inputting specific procedures on how to manage any kind of incident that would be involved in the training. In other words, it needed operating guidelines (OGs).

At that time, the department had many OGs but only a couple that pertained specifically to operations on the fire ground.

“I put together an OG committee and many, if not most, of the OGs we now have came out of this,” says Gray.

As the procedures were entered into the system and used in the simulated fires, an interesting thing happened: it became evident that some of the procedures were not as effective in certain scenarios as they should be. They were changed. It’s not unusual for operating guidelines to be updated or changed after the procedures are applied at a real fire. But now any flaws were being found in simulation, not on the street.

“We weren’t married to our OGs,” says Bezanson, one of the certified Blue Card instructors. “They have to be practical. No one had a problem if a written OG had to be changed.”

The department now has more than 60 operating guidelines, more than one-third directly relating to the fire ground. The OGs cover fires ranging from illicit drug labs to attached garages, and from strip malls and industrial buildings to forest fires. Thanks to the simulator, all of these scenarios were fire-tested without ever seeing an actual fire.

The OGs are a critical part of the officer training program. There are now four certified Blue Card command training instructors: two training officers and two division commanders (previously known as platoon chiefs).

To understand the complexity of bringing all fire officers to the same level of training and knowledge throughout the department, one must appreciate the geography of the City of Halifax.

When Halifax Regional Fire was formed in 1996, it incorporated two cities (Halifax and Dartmouth), four large communities that could best be described as towns, and scores of villages and settlements. Halifax Regional Municipality is spread over about 5,577 square kilometres. Toronto, by comparison, is about 630 square kilometres.

For the fire service, amalgamation basically meant joining two career city fire departments, four career/volunteer town departments, and 32 other departments, most of which were entirely volunteer.

Continued on page 23

B y L ES K ARPLUK

Fire Chief, Prince Albert, Sask.

AND

Ly LE Q UAN

Fire Chief, Waterloo, Ont.

cLEADERSHIPforum

Conspiracy theories and other challenges

onversations about leadership often revolve around senior fire department staff and how they encourage colleagues to become part of strong teams or part of the team working on a department project.

However, we have seen how newly promoted officers are expected to manage, lead and motivate staff with little experience in these areas. One can assume that newly promoted officers are up for the challenge, but if leadership were about giving people good news, the job would be easy. If leadership entailed only managing, leading and motivating staff, most officers would be successful. There are some dangers of leadership and newbie officers need to be aware of these dangers and expect challenges to their authority. Leadership is not just about leading the troops; it’s also about how you can build a strong team with a focus on getting the job done.

For the most part, members of the department know the histories, successes and failures of newly promoted officers. The challenge for new officers is that this change means moving from the known to the unknown; new officers will be tested by other officers to see how they have changed with the promotion.

Whether consciously or unconsciously, there are a few tactics for testing new officers: diversions; overwhelming the new officer with demands; and, in some cases, personal attacks. The fire service has a habit of testing everything and everyone to the max. This type of pressure can be good because it quickly tests the new officer; on the other hand, it doesn’t give the new officer the time to transition to team leader from teammate.

When new officers are expected to bring contentious policies to members, firefighters can consciously divert the leader’s focus to disrupt the policy directives. Let’s say a new officer brings forward a policy on training expectations that is different from the department’s usual policy. One diversion tactic is to put pressure on the new officer to superficially implement the policy, in other words, to do the bare minimum, fudge the records and make the members happy. After all, being

accepted by the group is a large part of being a leader. Another tactic is to bring up a different issue in order to have the officer redirect attention to the demands of the less critical issue. The less critical issue then takes on a life of its own and uses up time and resources. Author Warren Bennis describes this type of diversion as an unconscious conspiracy to get you off your game plan. Stay the course unless you are convinced that you need to refocus your priorities, but refocus only if it’s right for the betterment of the team and the department.

Occasionally, personal attacks are made to draw attention away from the key message or original plan. These attacks can target the character and competence of the new officer through claims that since the promotion, the officer has run around giving orders like a drill sergeant. Personal attacks hurt and can do damage. It’s very important for new officers to stay composed and understand that these types of challenges are growing pains that we have all experienced as we have moved up the ladder.

There are many positives to taking on leadership roles, such as undergoing personal growth and being able to affect change in the department.

On-the-job experience does not guarantee the development of leadership attributes. In fact, in many cases, on-the-job experi-

‘‘ i f leadership entailed only managing, leading and motivating staff, most officers would be successful. ’’

ence can present roadblocks for the person tasked with leading people. Use the experience as a foundation on which to build.

Les Karpluk (top) is the fire chief of the Prince Albert Fire Department in Saskatchewan.

Lyle Quan (bottom) is the fire chief of Waterloo Fire Rescue in Ontario. Both are graduates of the Lakeland College Bachelor of Business in Emergency Services program and Dalhousie University’s Fire Service Leadership and Administration program.

Developing people for officer positions requires a long-range plan and a sincere commitment by those wanting to be leaders. We need strong leaders in our departments today but we also need people in our departments who foster a culture that develops and nurtures leadership. Senior officers need to be mentors who share freely of their experiences and help to guide future leaders. Remember, there was a time when you were in their shoes.

A realistic assessment of leadership gaps in your department and the provision of development opportunities will go a long way to create successful leaders. Creating successful leaders is what senior management is all about, and passing the baton is also part of our culture and success.

BACKtoBASICS

Standpipe systems

By MARk vAN DER fEYSt

this month’s topic pertains to fire departments that serve buildings with either single or multiple standpipe systems. A standpipe system is defined by NFPA 14 as: “An arrangement of piping, valves, hose connections and allied equipment installed in a building or structure, with the hose connections located in such a manner that water can be discharged in streams through attached hose and nozzles, for the purposes of extinguishing a fire, thereby protecting a building or structure and its contents in addition to protecting the occupants. This is accomplished by means of connections to water supply systems or by means of pump tanks and other equipment necessary to provide an adequate supply of water to the hose connections (NFPA, 2003).”

Standpipe systems provide ways to deliver water from one area of a structure to another so that responders can fight fire, while at the same time shortening the length of the supply and attack lines. Standpipes can be intricate or simple systems, but the result is the same: water delivery. These systems are most commonly vertical, but they can be horizontal.

We tend to think of highrise buildings when we mention standpipe systems, but many types of buildings and facilities, both outdoor and indoor, have standpipe systems, including parking garages, shopping malls, warehouses, bridges, tunnels and large outdoor yards. I remember back in my engineering days with SimplexGrinnell designing several standpipe systems, for Weyerhaeuser in West Virginia for its outdoor yard – in which it stored all the incoming trees used for making oriented strand board sheets – for Dupont in Parkersburg, W. Va., for its two-storey building that housed a Teflon process machine, and for a state prison in Pennsylvania.

There are four types of standpipe but just one of them is a wet system (the other three are dry systems).

A wet system has water in the pipe at all times, supplied by a water source. The pressure in the system is constantly maintained.

One type of dry system is an automatic dry standpipe; in this case, air is always stored inside the standpipe at a constant pressure. When a hose valve is opened, the air escapes, allowing the water to enter into the standpipe system.

In a semi-automatic dry standpipe, air is stored inside the pipes, which can be pressurized or not pressurized. Once an actuation device – such as a manual pull station or an electrical switch – is activated, water enters the system.

The third type of a dry standpipe system is a manual dry standpipe. In this type of system, pipes feed the system with no air or water in them. A fire apparatus must be used to supply the water through the standpipe.

There are three classes of standpipe found within buildings: Class 1, Class 2 and Class 3.

A Class 1 standpipe is designed for firefighting personnel only, as it is equipped with a two-and-a-half-inch, or 65-millimetre, outlet (see photo 1). This outlet can be in a stairwell, in a cabinet, in the hallway or standing alone by an I-beam in an open area. The outlets

Photo 1: A Class 1 standpipe is designed for firefighting personnel only, as it is equipped with a two-and-a-half-inch outlet.

Photos by m ark

Photo

Photo 3: A variation on the Class 3 standpipe; it has only one valve, but can supply either a two-and-a-half-inch hose or a one-and-a-half-inch hose.

Photo 2: A Class 2 standpipe – accompanied by 100-feet of hoseline – is intended for use by building occupants only.

provided with this class of standpipe can vary in design; some will have a pressure-reducing device or valve attached to help regulate the discharged pressure from the system.

A Class 2 standpipe is designed for use by building occupants only (see photo 2). This standpipe system houses a 100-foot, or 30 metre, hoseline of one-and-a-half-inch, or 38 millimetre, hose attached to a reduced standpipe outlet. The Class 2 system allows occupants to safely escape the area of concern using the hose to provide a safe passageway by protecting the exit route. It is not designed for fighting fires. Firefighters could hook up to this type of standpipe, but doing so would involve undoing the occupant hose system and exposing the standpipe’s two-and-a-half-inch, or 65 millimetre, outlet.

A Class 3 standpipe is a hybrid version of Classes 1 and 2. It contains an exposed twoand-a-half-inch outlet, as well as occupant hose. This type of standpipe system is very common in buildings in which occupant load is consistent. In photo 3, you can see a variation of a Class 3 standpipe. It has only one valve, but there is an option to supply either a two-and-a-half-inch or a one-and-ahalf-inch hose.

An important area of concern for the fire department is supplying the standpipe system or tying into it with the fire apparatus. There will be a fire department connection (FDC) on the outside of the building for the standpipe system. The FDC allows firefighters to provide or add to the water supply and overall pressure inside the system. When connecting to the FDC, it is important to ensure that no debris is inside the FDC female couplings. Finding debris inside the coupling is common: the FDC is generally fairly close to the ground and kids often stuff things inside the pipe for no apparent reason. The FDC will be labelled Standpipe System immediately above the two outlets (see photo 4). This label lets you know which system to tie into, as there could also be a sprinkler system in the building. Sometimes there are separate FDCs for

each type of system and sometimes there are blended FDCs for all of the systems (see photos 5 and 6).

Be sure to gradually supply the water or increase the pressure inside the system. Standpipe systems are series of pipes that sit there and wait for use. They are sometimes filled with water or air and, after years of inactivity, they can deteriorate. Creating a water hammer in the standpipe system will only allow any deteriorated pipes, pipe couplings or standpipe valves to malfunction, causing more problems.

Next month we will examine the standpipe toolkit that should be assembled ahead

of time and brought with the highrise kit or apartment pack.

Mark van der Feyst is a 13-year veteran of the fire service. He works for the City of Woodstock Fire Department in Ontario. Mark instructs in Canada, the United States and India and is a local-level suppression instructor for the Pennsylvania State Fire Academy and an instructor for the Justice Institute of B.C. E-mail Mark at Mark@ FireStarTraining.com

Photo 4: The fire department connection will be labelled Standpipe System above the two outlets, making it easy for firefighters to distinguish between the standpipe system and the sprinkler system, if there is one.

Photo 5: Some buildings have separate fire department connections for each type of system – be it standpipe or sprinkler – in the building.

Photo 6: Other buildings have a blended fire department connection, which contains outlets for both the sprinkler system and the standpipe system. Regardless, the connection will be labelled.

By V INCE M AC K EN z IE Fire Chief Grand Falls-Windsor, N.L.

aVOLUNTEERvIsIon

Defining the role of a volunteer chief

s I wrote this in November, it was budget time for many fire departments. Fire chiefs – full-time and volunteer –struggle with a host of challenges, among them keeping municipal councils informed about service levels, standards and growing fire-service needs, and meeting local needs and circumstances while adhering to parameters set by elected officials.

Through my interactions with fire chiefs across Canada, I have realized that not all chiefs of volunteer departments enjoy the same co-operative relationships with their councils as I do. Where does a true volunteer fire chief sit in the eyes of council? Is a volunteer chief considered a department head and taken seriously? What influence does the volunteer chief have in the municipal arena? Does he or she behave like a department head and member of the team and is he or she treated as one?

The authority given to the chief should be clearly outlined in the fire chief’s job description, but it seems that these official descriptions are usually reserved for career chiefs. It has been eye-opening to learn that some smaller communities do not officially define the roles of their volunteer chiefs, although in most, if not all, provinces, provincial legislation defines the role under a municipalities or fire protection and prevention act.

In my opinion, volunteer fire chiefs should enjoy the role of a municipal department head in all aspects of the job and have some authority to shape the future of the department. This is done through co-operation as a valued team member of municipal government, especially on a financial and a policy level.

is how much of the department the chief actually manages, under the guidelines provided by council. Does council give the chief and the officers trust and autonomy to provide adequate service to its citizens? Council should certainly set the parameters for service and funding, then it is the chief’s job to provide that service as efficiently as possible, and to advocate for shortfalls. The fire chief should be able to exercise control over the department, the same as any career department head in the municipality.

Volunteer fire chiefs often struggle with the attitude of elected officials who refuse to acknowledge that the volunteer guy in the white shirt can and should manage the affairs of the department. How much respect is the chief given, other than as the nice guy who helps the community?

The volunteer fire department requires a tremendous amount of support from the community it serves on all levels, at all times. It is still a department within council – the same as any other. Just because the role is a volunteer one does not mean council’s expectations should be lower.

Sometimes, I meet chiefs who shrug their shoulders and say, “I am only a volunteer,” and they typically deflect difficult

The true effectiveness of volunteer fire chiefs is usually reflective of how well respected they are. ‘‘ ’’

The support afforded to a fire chief by council can vary from municipality to municipality. Also, fire chiefs are selected through many different processes and therefore the role can sometimes be as political as that of any councillor. Many communities rely completely on volunteers to do it all, including fund the fire department. Other departments are completely funded by taxpayers, as they should be, in my opinion. At the end of the day, the true effectiveness of volunteer fire chiefs is usually reflective of how well respected they are by council, regardless of the community’s size.

One of the first items fire chiefs and councils should examine

Vince MacKenzie is the fire chief in Grand Falls-Windsor, N.L. He is the president of the Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Fire Service, and a director of the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs. E-mail him at firechief@grandfallswindsor.com and follow him on Twitter at @FirechiefVince

management decisions. Today’s fire service needs leaders to take leadership of the department.

Part of being an effective fire-service leader is having the confidence in your ability to assert yourself to make sound decisions for your department in partnership with council. This is not easy but it is a skill that, when mastered, will increase credibility and among councillors and municipal staff. If council doesn’t already acknowledge your role as a competent leader and department head, you have to prove otherwise by actions and decisions.

Learn the strategies of marketing the fire department. Learn the municipal finance structure and the workings of it. Build a solid relationship with council.

Being a volunteer fire chief is no easy task, but taking the time to work together, learn leadership skills, and build sound relationships with all will position you and your department for success.

Continued from page 16

Today the department operates with 57 fire stations staffed by 471 career members and more than 640 volunteers. All members are at least Level 1 certified; they serve a population of 408,000.

With command training, the goal is to ensure a fire in downtown Halifax is fought the same way as a similar fire in outlying areas such as Moser River, 180 kilometres away at the eastern end of the municipality. The training is being taken to the volunteers via a portable command training centre. More officers, possibly including a couple of volunteers, will be trained as instructors.

In Halifax, as in other departments using the system, scenarios are based on the types of incidents that can be expected in the community.

“We had one officer go through a scenario as part of his training,” says Bezanson. “He called me the next day. ‘I just had that exact fire,’ he says. ‘I knew exactly what to do. It was the easiest fire I ever managed.’ ”

The program is not interactive. “There are winners and losers,” says Bezanson. “Some buildings will be lost no matter what. The aim is not to save the building. What’s important is how the incident commander reacts, how he handles it. How does he respond to information from other officers in the cubicles who are playing various roles? Is he following proper procedures, making the right decisions?”

It takes about 120 hours to build a scenario that focuses not just on procedures, but also on crew safety. “We now have drop boxes,” says Bezanson. “After we build a scenario we drop it on a site that can be accessed by all Blue Card users. All other departments in the world using this system now have access to our scenario, and we have access to what they’ve developed.”

The Blue Card certification is now also part of the promotional routine for career members aspiring to become officers. All career lieutenants, captains and division commanders have been through the course and training is well advanced among volunteer officers.

Training Officer Andrew Bednarz says 249 officers have been enrolled to date and 155 have been Blue Card certified. Another 35 are expected to be certified by the end of 2012. “That’s more than any other department in Canada or the U.S., and the most in the world so far as I know,” he says.

The training so far has had obvious results.

“It’s paying dividends already,” says Gray. “Consistency is evident now in how we are approaching fires throughout the municipality. Fireground chatter has changed. The transfer of command when a chief officer arrives on scene is smoother.”

Because of the portability of the simulator technology, Gray envisions carrying it to another level, such as pre-planning.

An officer doing a pre-plan of a particular building may do more than a walk-through – he/she may make a thorough photographic record of the structure. That can be used to build a scenario of that building in the simulator. “Now our pre-planning process can be moved into the classroom by creating various events that could happen in that structure.”

Likewise scenarios involving various types of commercial and residential buildings common to the municipality can be created and members can become skilled in fighting fires in those structures.

“I’d like to take this to a level,” says Gray, “that when captains step down from their fire trucks, they may be looking at a building they’ve never seen before and it’s on fire, and yet they’re also looking at a fire they’ve already fought in a virtual sense.”

John Giggey is a retired volunteer captain with Halifax Regional Fire. He works part-time in the department’s public affairs division. He is also a retired journalist, having acted as a supervising editor with the Canadian Press and Broadcast News in Toronto. E-mail him at giggeyj@halifax.ca

TRAINER’Scorner Get the most from your training

By ED BRouwER

If you are the go-to person for your department’s training, this column is a must-read.

In a recent conversation with a firefighter, it was brought to my attention that training nights often consist of the training officer reading out of the IFSTA manual. Are you kidding? In this day and age, having 14 firefighters sitting around a table while someone reads a chapter on ventilation is unacceptable, if not criminal. Our firefighters deserve better training than someone reading for 45 minutes; the only thing worse is taking turns reading – no one listens because everyone is too busy trying to figure out if the paragraph they have to read contains any hard-to-pronounce words.

Reading to your fellow firefighters as a training technique does little, if anything, to enhance participants’ learning. We remember only 20 per cent of what a good speaker says to us for up to 10 days, as long as we hear no other new information. However, if after 10 days we have not integrated that message into our lives, we forget it almost completely. Confucius said, “I hear, I forget; I see, I remember; I do, I understand.”

Learning is the ability to gain knowledge or information by means of understanding or experience. According to the adult-learning website www.joe.org, adults have special needs as learners and these needs should be considered when planning training sessions. Limited lectures, problem solving, case studies, scenarios and discussion groups are all effective adult-learning techniques, according to the site.

An article on adult learning by professors and graduate students at a Louisiana State University outlines effective learning techniques:

• Lectures are useful for presenting up-to-date information, summarizing material and focusing on key concepts or ideas. Lectures should be used in 10- to 15-minute sections, spaced with active learning activities to re-energize participants for the next wave of information.

• Problem-based learning is an instructional strategy that encourages critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

• Case studies bring real-world problems into the training. Use of case studies can result in better retention, recall and use of learning outside the training.

• Role play is defined as an experience around a specific situation. The situations should be realistic and relevant. The most successful scenarios develop a skill.

• Discussion encourages students to discover solutions.

Do you learn better by seeing, hearing or acting out the information you receive? Actually, everybody learns by a mixture of methods, but one method or type is usually dominant in each person.

Respect the fact that your department members have different learning styles. There are three general learning styles: visual, auditory and kinesthetic.

• Visual learners rely on pictures. They love graphs, diagrams and illustrations. Show me is their motto. You can best communicate with them by providing handouts or writing on the white board.

• Auditory learners listen carefully to all sounds associated with the learning. Tell me is their motto. They will pay close

attention to the sound of your voice and all of its subtle messages, and they will actively participate in discussions. You can best communicate with them by speaking clearly and asking questions.

• Kinesthetic learners need to physically do something to understand it. Their motto is Let me do it. They want to actually touch what they’re learning. They are the ones who will get up and help you with role-playing. You can best communicate with them by involving volunteers and allowing them to practise what they’re learning.

Any activity that gets your firefighters involved helps them learn; activities also keep people energized and engaged.

Part of your job as a trainer is to recognize teaching moments and use them. The continuing education section of the website www.about. com suggests that when a student says or does something that triggers a topic on your agenda, you should be flexible and teach it right then. If that would mess up your schedule, teach a bit about the subject and then move back to your plan.

The best instructors are positive and encouraging. Give your fellow firefighters time to respond when you ask a question. They may need a few moments to consider their answer. Recognize the contributions they make, even small ones. Give them words of encouragement whenever the opportunity arises. Most adults will rise to your expectations if you’re clear about them.

Fire department trainers should consider using tactics that work best for adults, including a combination of lectures and hands-on exercises.

Photos by laura king

Better outcomes demand exceptional CPR

Genuine encouragement from one person to another, regardless of age, is a wonderful point of human interaction. This is your challenge as a teacher of adults. Beyond teaching your subject, you have the opportunity to inspire confidence and passion in another human being. That kind of teaching changes lives.

One can lack any of the qualities of a trainer and still be effective and successful, with one exception. That exception is the art of communication. It does not matter what you know about anything if you cannot communicate to your people.

lEARNiNG StYlES

People learn best when:

• They are assured that they are respected.

• They can see that what they are being offered is what they need.

• The session content is organized around problems with which they are actively concerned

• Their learning takes into account what they already know and builds on that.

People learn from repetition; people learn from repetition; people learn from repetition; people learn from repetition, and of course, people learn from repetition. So do you know how people learn?

PRESENtiNG iNfoRMAtioN Lecturette:

• Organize information meaningfully.

• Include an introduction and a summary.

• Prepare interesting visual aids and interactive questions.

Brainstorming:

• Post the question.

• Record ideas and thoughts from the group.

• At the end, categorize the responses.

Buzz groups:

• Divide students into small groups.

• Assign a task or problem to the groups and set a time limit.

• Discuss each group’s findings.

Case studies:

• Write a real-life story (or download case studies regarding firefighter accidents or fatality reports).

• Pose questions that require solving and discuss responses.

Discussions:

• Create questions that support your teaching objectives.

• Promote involvement from all members of the group.

• Use in both large group settings and buzz groups.

tEAChiNG tiPS

• Adequately prepare for each lesson. Your best instructional tool is preparedness!

• Study the lesson outline well before you have to present it.

• Study the lesson objectives. You must know the goals for the lesson.

• Preview any videos and test your equipment.

• Prepare visuals (flipcharts, flashcards, posters).

• Use your imagination and coloured markers.

• Prepare your transparencies or PowerPoint ahead of time.

• Select or create appropriate questions and skill tests.

• Use the three Ds: describe, demonstrate and do.

• Allow students time to touch, take apart and put back together the new equipment.

• Keep the lecture to a minimum!

• Maintain a sense of humour.

• Encourage with positive feedback!

• Do not belittle people or laugh at their questions or answers.

• If you are training volunteers, keep in mind that your members may have just finished eight hours of hard work, wolfed down supper and are now more ready to sleep than to learn. Take note, as well, that for the most part, your students are not going into the fire service for a career. Your task is great!

Each trainer is held accountable to the NFPA 1041 standard. There are critical additions to the 2012 edition of NFPA 1041, which include:

• An emphasis on safety in the learning environment.

• New coverage on distinguishing different methods and techniques of instruction.

• A new job-performance requirement on preparing requests for resources.

• A new job-performance requirement on scheduling single instructional sessions.

• Information on developing techniques to recognize cultural diversity, bias and discrimination when considering instruction, materials and learning environment.

• Information on how to identify the elements of methodologies in a technology-based society.

Keep it simple: At one recent training night, we did a quick lesson (20 minutes) on fire behaviour. We used emergency candles, matches, coat hangers and cotton swabs. We demonstrated radiant heat, convection and conduction, and we proved white smoke could ignite.

Ed Brouwer is the chief instructor for Canwest Fire in Osoyoos, B.C., and Greenwood Fire and Rescue. The 21-year veteran of the fire service is also a fire warden with the B.C. Ministry of Forests, a Wildland Urban Interface fire suppression instructor/evaluator and a fire-service chaplain. Contact Ed at aka-opa@hotmail.com

disaster response

research, policies aim to incorporate ordinary people into plans for large-scale incidents

By JosepH sCanLon and JeLLe groenendaaL

Ordinary people are generally the first to respond to any natural disaster, such as the F2 tornado that struck Midland, Ont., in June 2010. The Amsterdam-Amstelland Fire Department has developed policies to include citizens in the response to large-scale incidents that help responders decide whether and how to co-operate with people, organizations and groups.

When a tornado tore through a trailer park in northeast Edmonton on July 31, 1987, the first responders were not Edmonton firefighters or Edmonton police or ambulance or even volunteer firefighters from the neighbouring forensic psychiatric hospital.

The first responders were uninjured and injured survivors. They did the initial search and rescue and they used their own vehicles to transport injured people to medical centres.

By the time volunteer firefighters arrived, those Good Samaritans and the people they had rescued had left: no one

remained to tell responders who was still buried in the wreckage.

There was another complication: the tornado struck at the start of evening rush hour. As firefighters and then police tried to sort out what needed to be done, they were besieged by arriving residents who were convinced, usually wrongly, that their relatives still needed rescuing. It soon became apparent that no one knew the precise situation; so police and the volunteer firefighters teamed up to do a systematic search of the wreckage. One at a time, they located trapped and severely injured victims, people the survivors had been unable to rescue.

Most emergency plans assume that an

Photo

R appel to S afet y

MSA’s Rescue Belt II System allows firefighters to rappel to safety in an emergenc y situation An integrated, NFPA- compliant device for emergenc y egress, the Rescue Belt II provides single -handed deployment of egress components The ergonomically-contoured Ara-Shield rescue belt pouch easily stores your rope, descender, Crosby hook or carabiner One belt fits all members of the fire depar tment

MSA provides you with the most advanced equipment available Our job is to be there so that EVERYONE goes home

Learn more about the new Rescue Belt II System w w w MSAsafety com Keyword: RescueBeltII

1-800-MSA-2222

emergency will be at a specific site or location and that the entire response will be by emergency agencies working together. Ordinary people will not be involved.

In fact, in a widespread destructive incident, this is not what happens. In Edmonton, for example, the tornado was on the ground for 65 minutes and it left behind a trail of destruction, injury and death that started south of the city, continued as the tornado headed north, passed briefly through part of Strathcona County, and reached the Evergreen Mobile Home Park. Long before then, Edmonton’s emergency agencies – fire, police and ambulance – were committed to other parts of the city. In addition, roads were blocked by debris and flooding. By then, too, emergency communication systems were overloaded. In short, individuals at the trailer park did the initial search and rescue because there was no else around to do it and because immediate assistance was required.

Events such as the Edmonton tornado – 26 dead, about 400 injured – are rare; but a response by ordinary people is not. The fact is that when there is a disaster – no matter what the cause of the incident or its size – ordinary people are not confused or in shock or in panic, and they don’t stand

around and wait for someone to help: they look around and do whatever they can.

When Swissair crashed into the Atlantic Ocean off Peggy’s Cove, N.S., in 1998, the first response was by local fishermen. When the first Royal Canadian Navy ship arrived, it welcomed the fishermen’s response and helped them form organized lanes for searching. Similarly, after the terrorist attack on New York City in 2001, hundreds of small craft helped citizens evacuate from Lower Manhattan. Even before that, it was ordinary people who decided to evacuate the twin towers while voice messages were telling them everything was all right.

Although the fact that ordinary people get involved in emergency response has been well documented, many emergency planners and emergency agencies resist this: some plans state explicitly that civilians should not be allowed to take part in the response.

The Amsterdam-Amstelland Fire Department, the largest fire department in the Netherlands, is taking a different approach. It is trying to figure out how to involve ordinary people in its response planning. It even staged an incident in front of a threatre just as patrons were

coming out so it could see what they did. The department started in 2004 staging workshops in which firefighters, police, local officials and disaster researchers discussed the role of ordinary citizens in emergencies. These workshops made it clear that ordinary citizens can become involved in different ways: they can act on their own as individuals or groups, just as the people did in Edmonton; or they can take on tasks assigned to them by emergency personnel.

In the wake of the Mexico City earthquake – where there were thousands of volunteer rescuers – the Los Angeles Fire Department decided it would be appropriate not just to accept that ordinary citizens might get involved in emergency response but to recruit and train citizens to perform or assist with a number of emergency tasks. The approach is known as Citizen Emergency Response Training (CERT). The 18-hour training course has been adopted by other U.S. communities and by some other countries, and includes light search and rescue, fire suppression, first aid, transportation of the injured, communication and leadership skills.

CERT is similar in many ways to the Canadian civil defence training for volunteers that took place during the peak of the cold war, but it is quite different from what the Dutch have in mind. They want to determine what untrained civilians do in emergencies so that these actions can be taken into account when firefighters and other emergency personnel respond.

Let’s assume that what happened in Edmonton happens again, and that ordinary people take injured civilians, stick them into their vehicles and drive them to the nearest hospital. What happens when these people arrive at hospital? Hospital personnel are not used to extracting victims from vehicles. Firefighters are used to doing that. That means it would make sense – given a widespread destructive incident – to have some firefighters respond to hospital emergency rooms to help safely handle the injured who arrive in private vehicles. That may sound absurd, but it is this kind of unorthodox approach that is being discussed in Amsterdam.

There are occasions when ordinary citizens can make a valuable contribution to the response by professionals because they do things that firefighters initially are unable to do: they provide assistance to less injured people, shelter people, evacuate and warn fellow citizens. And they often also assist professional responders: ordinary citizens may have better local knowledge, resources and expertise than the firstarriving units of emergency services.

WHERE QUALITY COMES FIRST

Although the fact that ordinary people get involved in emergency response has been well documented, many emergency planners and emergency agencies resist this: some plans state explicitly that civilians should not be allowed to take part in the response.

The point of the Amsterdam initiative is not to tell others how to plan, but to change the mindset of emergency personnel so that they better understand how to work with ordinary people at an emergency scene, rather than moving them out of the way. The goal is to have responders recognize what people will do before emergency personnel arrive, have a plan for enlisting their support, and make sure what they do enhances the response.

The Dutch project is still very much a work in progress and there are still serious issues to be resolved.

First, emergency responders are often unwilling to accept assistance from ordinary people due to the possibility of being held accountable if volunteers get injured. That, of course, is not an issue if the response occurs before emergency personnel arrive but it is an issue after that.

Second, professional responders find it difficult to assess whether ordinary citizens are able to make a valuable contribution. For instance, professional responders worried about how they could identify someone as a physician. In AmsterdamAmstelland, procedures require that professional responders ask ordinary citizens to show evidence that they have specialized skills and knowledge.

Third, it is now often a requirement that volunteers be screened if they are likely to be dealing with children to make sure that they have no record of sexual offences. This suggests that if emergency planners wish to integrate ordinary people into emergency response they need to consider how they will take whatever steps are required to make them acceptable.

To help professional responders make better use of ordinary citizens, the Amsterdam-Amstelland Fire Department has developed new procedures. The core of the new policies is a set of criteria that helps emergency responders decide whether and how to co-operate with ordinary citizens, organizations and emergency groups.

First and most important, the new policies specify explicitly that all emergency responders are allowed to accept assistance from ordinary citizens and organizations in the emergency work. Co-operating with citizens and allowing citizen’s response is therefore a (new) professional standard.

That does not mean co-operation with ordinary people is always desired; there are some conditions that must be met:

• Co-operation must be voluntary – no individual group or organization can be forced to participate in the emergency work.

• The tasks assigned should be without many safety risks.

• The tasks should add value to the overall emergency response.

• Ordinary citizens can only be asked to fulfil a task when they have the skills and knowledge to complete the task successfully.

To facilitate the use of these criteria in practice, the Amsterdam-Amstelland Fire Department developed a five-phase model.

• Phase one assumes that victims and bystanders will start by providing help and mitigate the crisis situation before emergency personnel arrive.

• In phase two, the first few professional responders will arrive. In

this phase, professional responders are taught to accept assistance and not to push ordinary people aside.

• Phase three starts when commanders in charge of the fire brigade, police and medical service arrive: when they are on hand citizen response will be discussed in the first structured meeting, and a decision should be made about

its effectiveness. If appropriate, arrangements will be made for registration of volunteers.

• Phase four occurs when the operation continues under control by the professional emergency agencies. In this phase, no new helping citizens will be allowed unless the incident commander requests it.

• Phase five requires that officials

thank citizens who made a contribution to the emergency response – and that officials explore the possibility of compensation for possible damage to personal belongings.

In short, private citizen involvement must be considered at all stages of emergency response.

The Amsterdam Fire Department believes it has a responsibility to provide leadership to others with fewer resources. However, it acknowledges that in largescale emergencies, it has too little capacity to help all those who need may help, especially in the first few hours; and – most important – there is a growing awareness within the department that the help of ordinary citizens is important for the effectiveness of the response by professionals. Ordinary citizens often make it better.

Joseph Scanlon is professor emeritus and director of the Emergency Communications Research Unit (ECRU) at Carleton University in Ottawa; he has been studying emergency response for 42 years. Jelle Groenendaal is a doctoral student who is working with the Amsterdam-Amstelland Fire Department.

The Amsterdam-Astelland Fire Department’s new protocol says that all emergency responders are allowed to accept help from ordinary citizens in the case of disasters such as tornados.

Photo courtesy m i D lan D Fire De P artment

Continued from page 12

hall to decontaminate workers leaving the Bruce Power site and register workers who would be required to report to Bruce Power.