ROSS DELIVERS

• Leading

• Impressive

• Strong Livability ROSS

• Highest Yield

• Excellent Breeder

Performance

• Exceptional Livability

From the Editor

by Brett Ruffell

Preventing a supply chain knot

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve covered the impact it’s had on poultry. Many people credit our supply managed system for poultry’s orderly response to the pandemic, and rightly so. But another key factor that deserves recognition is the hard work of poultry processors. They’ve persevered through numerous plant closures due to COVID-19 outbreaks to continue to ensure store shelves are stocked with poultry products.

And they’ve faced an array of other challenges along the way, the most pressing of which are labour related. In short, it’s gotten both harder to attract workers and harder to retain them. To find out more about how this is impacting the industry and how it’s responding, I spoke with JeanMichel Laurin, president and CEO of the Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council (CPEPC).

Late last year, his organization conducted a voluntary survey of its members around labour issues after several complained about staffing challenges. “The idea was to give us a yardstick of how significant an issue this was for our membership,” Laurin says. The results worried him.

Respondents reported having a total of 2,600 unfilled positions (Laurin suspects that number has grown to around 3,000 with the latest

pandemic wave). The majority of these openings were in primary and further chicken and turkey processing.

Nationally, 54 per cent of respondents said more than 10 per cent of their positions were unfilled while 13 per cent said that over 25 per cent of their positions sat vacant. The vast majority (87 per cent) of respondents said the situation had gotten worse or significantly worse in the last two years while 53 per cent expect things to deteriorate further.

The survey then dove deeper to uncover the reasons behind these vacancies. Absenteeism was an obvious issue given the pandemic. But what

sumers who buy our products and to the producers who rely on our members, which is great. But the pandemic has taken its toll.”

For one, some members lamented the loss of the social element in their workplace due to pandemic restrictions. One reported their work had become almost “robotic”. A few people Laurin talked to added that the heavy use of elaborate PPE and plexiglass dividers made the industry less appealing for potential workers. Thirdly, the industry has faced intense competition for workers from jobs that allow people to work from home during the pandemic.

canadianpoultrymag.com

Reader Service

Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Anita Madden, Audience Development Manager Tel: (416) 510-5183

Email: amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Associate Publisher

Catherine McDonald cmcdonald@annexbusinessmedia.com Cell: 289-921-6520

Account Coordinator Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer Alison Keba

Group Publisher Michelle Allison mallison@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $32.50 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $91.50 CDN

Laurin then followed up with some of the members who responded to the survey to get to the bottom of these turnover findings. He sums up those conversations: “We’re an essential service to the con“We’re struggling to find workers but also we’re having a hard time retaining existing workers.”

So, what’s the answer? “The only immediate solution we can really see is expanding access to the temporary foreign worker program,” Laurin says, noting that only onethird of his members are using the program.

stood out to Laurin was the high turnover rate. “We’re struggling to find workers but what the survey also tells us is we’re having a hard time retaining existing workers,” he says, noting that the survey found 40 per cent of respondents reported a turnover rate above 30 per cent.

CPEPC has been collaborating with a group of associations, with the support of poultry farming boards, to convince the federal government to make the program more accessible.

For most industries, including food processing, the program is currently capped at 10 per cent of a company’s workforce. The collaborative group wants that expanded to 30 per cent for about 18 months. They also want the application approval process sped up. After the coalition met with federal agriculture minister Marie-Claude Bibeau about the topic, Laurin says he’s optimistic the government will act.

Foreign – 1 Year $103.50 CDN

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2022 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

KEEP YOUR FLOCK HYDRATED AND LITTER DRY

Farmers around the world trust our drinking systems to deliver a consistent flow of fresh water to their flocks for the best laying performance, and with our littergard cup your litter will remain dry and your birds healthy.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664-3811

Fax: (519) 664-3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Les Equipments Avipor

Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263-6222

Fax: (450) 263-9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963-4795

Fax: (780) 963-5034

United Agri

Abbotsford, BC

webuildfarms@agrihub.ca

Tel: (604) 859-4240

Fax: (604) 859-3730

What s Hatching

Avian influenza forces 12,000 turkeys to be killed at N.S. barn

Officials with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency say 12,000 turkeys at a commercial barn in western Nova Scotia had to be euthanized after avian influenza was discovered at the farm. The news was revealed during an early February media briefing. Restrictions are now in place for commercial operations within 10 kilometres of the affected barn to prevent the virus from spreading.

Governments announce ag recovery fund after B.C. floods

Agricultural producers affected by devastating flooding in British Columbia last November can apply for recovery funds through a $228-million package announced Monday by the provincial and federal governments. The total losses for the agricultural sector from flooding that stretched across the Fraser Valley into the southern Interior are believed to amount to about $285 million, B.C. Agriculture Minister Lana Popham told a news conference.

Two poultry companies fined $300K each for animal cruelty

A Chilliwack company and an Ontario-based poultry processor have been fined $300,000 each after pleading guilty in September to two charges of animal cruelty for causing undue suffering to chickens. Elite Farm Services Ltd. of Chilliwack and Ontario-based Sofina Foods Inc. are also subject to three-years probation. The B.C. SPCA opened an investigation in response to the release of video footage showing hens stuck in mounds of feces and packed into wire cages with dead birds.

EFC doubles egg donations across country

is how many Egg Farmers of Canada announced it is contributing to food banks across the country.

20% is how much visits to food banks across Canada have risen by in the two years since the pandemic began, according to Food Banks Canada..

Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) announced it is contributing approximately 3.5 million eggs to food banks across the country. This comes as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact Canadian food security in every province and territory.

With the pandemic extending into the new year, Food Banks Canada appealed to Canada’s more than 1,200 egg farmers for more local eggs to ensure that fresh, nutritious food be made available to anyone and everyone who needs it.

As longstanding supporters of food banks across the country, Canadian egg farmers from B.C. to Nunavut to Halifax responded to the call to give back.

“Canadian egg farmers have always worked together in support of our communities and Food Banks Canada – with their dedicated team of people and volunteers – plays an essential role in our farmers’ continued support,” says EFC chair Roger Pelissero.

“We’re aware that these are especially challenging times for so many individuals and families. For this reason, it is crucial that we remain compassionate and continue to support people the best way we can.”

As we hit the almost two-year mark of the pandemic, visits to food banks across the country have risen by 20 per cent, according to Food Banks Canada.

“It’s been another tough year for those who struggle with hunger, including our neighbours and friends in all communities in Canada,” says David Armour, interim CEO of Food Banks Canada.

“With food bank use continuing at record levels, it’s more important than ever to come together as a country to find new and innovative ways to provide healthy, nutritious food for those who need it today, while moving the needle on policies that will prevent hunger tomorrow.”

You’re behind Canadian agriculture and we’re behind you

We’re FCC, the only lender 100% invested in Canadian agriculture and food, serving diverse people, projects and passions with financing and knowledge.

Let’s talk about what’s next for your operation.

FCC.CA DREAM. GROW. THRIVE.

What s Hatching

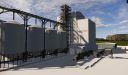

Trouw building new production facility in B.C.

Animal feed company Trouw Nutrition Canada, a subsidiary of Nutreco, announced today that it has begun building a new production facility in Chilliwack, B.C. Construction began in fall 2021 and is expected to be completed no later than fall 2023.

The Fraser Valley Regional District is essential to Canadian livestock production. Local farmers are leading the way in producing high quality meat and dairy products for Canadian and international consumers.

Trouw says it is dedicated to ensuring that livestock producers in the surrounding region receive the highest quality of animal nutrition and expertise in the market.

“As market demands have remained steady, especially with our bulk and lifestyle business, as an organization, we are always looking at ways to increase efficiency within our mills, through newly automated systems and process,” says Jared Webster, regional sales manager, Trouw Nutrition Canada.

“Our new production facility will help to increase the optimization and consistent flow of our

feed, so we can continue to meet the high demands of our customers,” he continues.

The new plant will occupy a total area of 40,000 square feet, 1,100 tons of structural steel and 5,000 m3 of concrete.

A sustainable concept is driving the project, exemplified on the new drainage system with an underground pond that will be installed for reducing flooding for surrounding properties.

The new facility will include cutting-edge technology to ensure food safety and quality, applying the vertical concept of ingredient flow and distribution.

Maple Reinders, who is the prime contractor of the project plans to finish the construction by the end of 2023.

“Investing in a new production facility will allow us to continue to provide consistent, high-quality products for all animals in a cost-effective and efficient manner,” says Maarten Bilj, managing director, Trouw Nutrition Canada. “Ninety-five per cent of the volume produced at this feed mill is consumed within a 50 km radius of the Fraser Valley.”

Coming Events

FEBRUARY

FEBRUARY 28, 2022

Western Poultry Conference poultryindustrycouncil.ca

MARCH

MAR. 2, 2022

PIP Innovation Showcase, Webinar poultryinnovationpartnership.ca

MAR. 16, 2022

BCPS Webinar Series bcpoultrysymposium.com

MARCH 21-22, 2022

AWC WEST 2022 Calgary, Alta. advancingwomenconference.ca

MARCH 22-24, 2022

MPF Convention Minneapolis, Minn. midwestpoultry.com

MAR. 26, 2022

PIC Raising Backyard Chickens, Webinar poultryindustrycouncil.ca

APRIL

APR. 6, 2022

PIP Innovation Showcase, Webinar poultryinnovationpartnership.ca

APR. 6-7, 2022

sustainable concept is driving the

by the new drainage system with an underground pond that will be installed for reducing flooding for surrounding properties.

CDX: Discover Poultry Production Stratford, Ont. dairyxpo.ca

APR. 20, 2022

BCPS Webinar Series bcpoultrysymposium.com

APR. 25-29, 2022

Shell Egg Academy Lafayette, Ind. shelleggacademy.org

JUNE 22-23 (NEW DATE)

National Poultry Show London, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

The Chilliwack, B.C. Trouw Nutrition team attending a groundbreaking ceremony for the new project

A

project, exemplified

LRIC Update

By Lilian Schaer

Livestock Research Innovation Corporation (LRIC) fosters research collaboration and drives innovation in the livestock and poultry industry. Visit www.livestockresearch.ca or follow @LivestockInnov on Twitter.

Modelling, AI open new avenues

Poultry research around the world is evolving, giving farmers more tools to address complex issues and improve the health and welfare of their flocks.

Reducing the carbon footprint of poultry production, avoiding the next global pandemic or finding alternatives to antimicrobial use in production are among a slew of issues facing the industry. And, increasingly, science is turning to artificial intelligence and modelling in the search for practical, workable solutions for the livestock and poultry sectors.

Enter Jennifer Ellis, assistant professor in Animal Systems Modelling in the University of Guelph’s Department of Animal Bioscience with a particular specialty in poultry and dairy cattle nutrition modelling.

Her research uses models to identify patterns in data, increase understanding of how biological systems work to better predict outcomes. She also works to build links between complex nutrition, health, genetics and management data to help farmers with on-farm decision making.

“We have a big data wave coming at us, but it is worthless if we don’t know what to do with it,” she explains. “We have to harness the tools we do have for better opportunity analysis and decision-making on the farm. “

That’s where artificial intelligence can help. It’s an entire knowledge field that includes

computer systems that can perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, like speech or image-recognition or decision-making.

According to Ellis, machine learning is a sub-group of that field that focuses on the development of algorithms to predict outcomes based on detecting patterns in data.

For poultry and livestock producers, this means a greater ability to track individual birds and animals instead of simply a pen, a herd, or a flock, and to do so without intensive labour involvement. It opens up new avenues for precision management, nutrition and feeding that can ultimately lead to healthier, more productive animals.

“We have a big data wave coming at us, but it is worthless if we don’t know what to do with it.”

Examples include activity sensors that monitor and analyze behaviour and can alert producers to possible health problems before an animal shows actual clinical signs of illness or image analysis that can count livestock or estimate their body weight.

“Precision feeding is one area where we are already seeing some prototypes come to the surface, mainly for swine and poultry in research environments, where a system will estimate the weight and growth trajectory of an animal

and customize its nutrition accordingly,” she says. “Also, if we can use technology to detect a health event before a vet can, that can offer huge economic return to the producer.”

Another area is precision nutrition formulation at the feed mill through the prediction of pellet quality and durability by analyzing the nutrient composition of inputs. Real-time formulation adjustments could provide more consistent feed.

“We can predict a lot of things already, but we also need to know what to do with that information. We are still in exploratory days with how we generate value from all this and ultimately, how we can improve efficiency, increase productivity, and make life easier on the farm,” she says.

Ellis currently has two research projects in this field underway. One, in partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) and Trouw Nutrition, is using machine learning algorithms to predict pellet quality at the feed mill.

The other, a collaboration with OMAFRA, Trouw and Wageningen University, brings together artificial intelligence and mechanistic modelling to develop a smart precision nutrition system that ties biological knowledge to predictability.

This article is provided by Livestock Research Innovation Corporation as part of LRIC’s ongoing efforts to report on Canadian livestock research developments and outcomes.

Jennifer Ellis of the University of Guelph has two research projects underway that explore the potential for data technology in poultry production.

NEMA4X LED LIGHTING FOR POULTRY

Fits most globe marine type fixtures (jelly jars)

2500V surge protection

UV resistant, high impact, corrosion resistant

IP66 Rated, NEMA4X

120 Beam angle - more light at floor level

5 year warranty (proper dimmer required for dimmable bulbs)

Building Bridges

By Crystal Mackay

Mackay is the CEO of Loft32, a company she co-founded with the goal to help elevate people, businesses and the conversations on food and farming. Her latest work includes an online training platform, www.utensil.ca with on-demand training programs and resources.

Improving conversations on food and farming

Definition of bridge (Merriam-Webster)

• A structure carrying a pathway or roadway over a depression or obstacle.

• A time, place, or means of connection or transition.

Do you remember when you first heard the term ‘rural-urban gap’? I experienced it first-hand when I volunteered to visit classrooms to talk about dairy farming when I was in high school. I was shocked that the kids in our very rural area didn’t know where milk came from, even though they drove by farms or even knew people who farmed. Fast forward a few decades. The gaps have grown well beyond rural-urban and are all over the map – between farmers and consumers; between types of farms; between regions and sectors across the food system. So what, you might ask. What does it matter if our

man health issues argued in public forums.

And finally, the third approach that hasn’t worked is sales and marketing thinking. Messages ‘brought to you by’ those that profit or including a sales pitch continue to be discarded and discounted more than ever. This is unfortunate, as those who work in the business often know the most about it. Farmers themselves continue to hold a halo effect as credible to most, even though they profit from their farmgate sales.

food system isn’t connected internally or externally?

The foundation for trust and support for our food system is best built through relationships and connections. Conversations lead to better understanding up and down supply chains and right through to the person who eats.

The logical approach to gaps is to build a bridge. According to Webster, we need bridges to help us get over obstacles and serve as a means of connection. Like many problems, the first step is acknowledging we have one and then preparing to do something about it. So, how best to build bridges to better conversations and relationships on food and farming?

A good place to start is with

what doesn’t work. Experience in pioneering agriculture awareness work proves, and Canadian Centre for Food Integrity research backs it up, that people don’t want to be educated. Cramming all your facts and data into a lecture about poultry hasn’t worked yet – unless they signed up for a degree in agriculture. It’s important to note many people are interested in knowing a bit more about where their food comes from. “Wow, I didn’t know white eggs come from white hens.”

The second approach that hasn’t worked yet is arguing with people or having them defend their food choices, opinions or ideals. Forcing someone to defend a position will only make them more deeply commit to it, even if their logic can see that it may be flawed. This has become increasingly obvious with hu-

Moving on from what doesn’t work to what works –let’s have a conversation about food that can lead back to the farm. People love talking about food. It’s personal, fun and interesting. It’s not a commodity or an issue or a sector for the majority of people who don’t work in agriculture. And the good news is we all eat, so we have that in common!

Our communications up and down and across supply chains and with Canadians should be framed up as an authentic conversation. This includes listening. It’s an interesting phenomenon when engaging with someone that if you listen to them they will listen to you.

The best bridges don’t get built in a hurry, without a plan or expertise. The same holds true for better conversations and connections to lead to trust and support for food and agriculture in Canada.

The is the first installment in a series of columns by Crystal Mackay on building bridges to better conversations on food and farming. Watch for her follow up columns in future editions of Canadian Poultry.

Crystal

World of Water

By Mary K. Foy

Mary K. Foy is the director of technical services for Proxy-Clean Products. The U.S. company’s cleaning solution is used in Canada as part of the Water Smart Program developed by Weeden Environments and Jefo Inc.

Water key to animal welfare

The legalities of how we should treat animals, and specifically food animals, can be debated for days. But the reality is that a good farmer instinctively knows that their livelihood depends on their animals flourishing.

I emphasize “good”. Calling yourself a farmer is easy. Succeeding and being “good” at it seems like a divine talent some days.

The list of what the grower cannot control is long – weather, the hatch history, etc. So, it is vital to a grower’s success that they do all they can to maximize what they can control. One of the things they can control, for the most part, is the quality of the water they give their birds.

As I’ve discussed columns, the properties of the water on the farm can have a direct impact on bird and equipment performance. How do you know if you have low-quality water? There are a few telltale signs you can look for and then there are some recommended tests to dig a little deeper.

Looking for water issues

Have the birds decreased the amount of water they drink?

Don’t know? Try putting a water meter on your water line and keeping a daily log of how much the birds drink. Most modern control panels can do that for you, too.

How often do you change filters?

Ok, how often should you be changing the filters? If you are changing the filters more than once every two weeks its time to up your filtration game.

How are your birds performing?

Are they flushing (have diarrhea)? This could be either a mineral problem, a bacterial problem or both. Do

they look great but just never put on any weight at a certain point? Lack of weight gain can also be an availability problem. Have you tested your drinker flow lately?

Are your drinkers sticking open and getting the floors wet?

When you walk the water line and trigger the drinkers are some sticking? Think about this – if you have five drinkers in a row and one is stuck shut, that’s a 20 per cent reduction in the available water for the birds in that area. Drinkers that are stuck open or shut could once again be caused by either a mineral problem, a bacterial problem or both.

Is there a slimy residue on the drinkers?

Open the water line at a joint and feel the inside. Slimy? Something is growing then. Keep in mind that even if you don’t see or feel a buildup on the parts of the water line, different kinds of bacteria produce different kinds of biofilm. Some have a hard, clear coating protecting them that you can’t see or feel.

Testing for water issues

Mineral

tests

Ph is what most growers think of first with mineral testing. A grower can test his own pH with some pretty reliable meters. Most agree that a pH of 5.5 to 6.5 is ideal for poultry drinking water. Sending off a sample of water for mineral testing can get you much more information than just pH, though. You cannot always see every present mineral just by looking at what catches on the filters in the system. Look for a lab that can test turbidity, calcium, iron, sulfates, chlorides, sodium, zinc, nitrates, magnesium and manganese. These are a few of the common

Most water quality issues can be solved with proper water treatment, filtration and maintenance of the water system.

minerals in source water that can impact bird performance.

Mineral tests are usually very easy to collect. Choose a spigot as close to the source as possible, let the water run until the pump kicks on, collect about 12 ounces or so in a clean (does not have to be sterile) collection container, seal it and send it to a proper mineral testing laboratory.

Bacteria tests

As I stated earlier, even if you don’t see a biofilm in the water system you may still have a bacteria problem. Some bacteria produce a hard, clear biofilm and some bacteria just cling to the walls of the water system without producing a protective layer at all.

The only way to know they are there is to test for them.

If you haven’t cleaned your water lines lately or if you don’t treat your water during grow-out you can assume there are organisms living in the water line.

The fact is that not all bacteria in our world are bad, but good or bad, you do not want them growing in the poultry water line.

5.5 to 6.5

is the pH level most experts agree to be ideal for poultry drinking water.

At the least anything growing in the drinkers can keep the drinkers from working properly and, at the most, “other” bacteria can help hide and protect pathogens such as Salmonella or Campylobacter. Contact a lab that tests water to get their specific instructions on collecting a bacteria sample. Bacteria sampling takes some preparation – follow the lab’s directions.

Most water quality issues can be solved with proper water treatment, filtration and maintenance of the water system. Sometimes it’s easy, sometimes it is not. Every farm is different, but when it comes to taking care of the animals that allow us to provide well for our own families, the “good” farmer is going to also make sure his animals are well cared for.

Catastrophic floods hit B.C.

Disaster struck the heart of the province’s poultry sector late last year. Here’s a look at the impact on poultry farms and the industry’s response.

By Treena Hein

In mid-November of last year, Dave and Sheryl Martens’ broiler operation was at the end of its production cycle. Suddenly, disaster struck.

The farm, called Bright Meadow Farms, is located on the Sumas Prairie east of Abbotsford, B.C. The area is home to the majority of the province’s poultry, dairy and pig farms.

The Martens family shipped out the 40,000 chickens on the second floor of the barn for slaughter on Sunday, November 14th. That was the day the Nooksack River in Washington burst its banks. But there was no news of this until the next day.

“The birds on the bottom floor were to be shipped on Monday,” Dave Martens explains. “The trucks were on the way, but they couldn’t get through. I dimmed the lights in the barn and called Trouw Nutrition to see about getting feed fast, as it might be difficult later.”

On Tuesday, Martens moved various pieces of equipment to

higher ground, just in case the farm was flooded. After lunch that day, 12 tonnes of feed arrived. But sure enough, at about 5:00 pm, Martens’ fears were realized. There was water lapping against the barn door. He faced limited options.

“If I turned off the breaker to the barn, the birds would die without ventilation,” he says. “We didn’t know the dike by the Sumas pump station had burst, but we saw the water was rising fast. I went to the neighbours’ house to warn them and by the time I left there, the water was close to a foot deep. There was nothing to do but leave the farm. At 8:00 pm, I knew the barn was flooded because the barn temperature was low. The sensors were clearly underwater.”

At the peak of the flood, the water depth at Bright Meadow Farms was over seven feet. Sadly, all 40,000 of the chickens on the bottom level drowned.

Like the Martens family, other producers in the region had their worlds turned upside down by the November floods. In total, “there were 61 poultry farms in the evacuation zones,” reported Amanda Brittain in mid-December, director of communications at B.C. Egg and the B.C. Poultry Emergency Operations Centre. Her comments also represent the B.C. Chicken Marketing Board. “The vast majority of the birds died by drowning. To the best of my knowledge, euthanasia was not needed on a large scale. That being said, common sense tells me that farmers must have euthanized a small number of birds that were suffering.” Carcasses

were removed and transported to several compost sites.

It was a heartbreaking total given to the press in mid-December 2021 of animals that died due to the flood: 628,000 birds (broilers, broiler breeders, layers and turkeys); 12,000 hogs; and 420 dairy cows/calves. In addition, 110 beehives were destroyed by the floods in lower mainland B.C. The historic rainfall in November had shattered more than 20 daily provincial records.

However, Brittain reported that the impact of the flood on chicken supply was minimal. She explained that there are poultry farms in many parts of the province and those not affected by flooding were able to supply most of what was needed at the time. Also, some poultry products came in from other provinces.

Collaborative effort

The Society of B.C. Veterinarians Chapter of the Canadian Veterinary Medicine Association organized communications and coordinated assistance efforts among veterinarians and other industry members. The Canadian military helped with flood issues and evacuated birds from one affected poultry farm.

In addition, the B.C. poultry industry associations worked collaboratively with the City of Abbotsford, the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries and the Abbotsford Police Department through the worst days of the flooding.

“Together, we ensured farms had feed, potable water and fuel,” Brittain says. “We were able to use

$228M is the size of the agriculture recovery fund governments announced in February in response to the B.C. floods.

several methods. The police or military would escort trucks to farms via flooded roads (only large vehicles could get through) and in other cases, boats (privately owned or provided by the city or police) would be used to take supplies to farms. In one case, a helicopter was needed to drop supplies to one farm. Finally, farmers helped each other out by driving tractors over flooded fields with fuel for generators.”

Heartache and stress

Dealing with any natural disaster takes a toll and “we are concerned about farmers’ mental health,” said Brittain, “as we’ve experienced a lot in the past few years including the pandemic, the heat dome, forest fires and now the flood.” The Ministry of Agriculture, Food and

Fisheries and AgSafe provided mental health resources. The heat dome incident in June caused the death of 595 people, at least 651,000 poultry and an estimated one billion marine animals.

At the same time, Brittain reported that the offers of help from individuals, church groups, sports teams and others has been overwhelming. “So many people called us wanting to donate cash that we created a page on our website that lists organizations accepting donations and organizing help,” she said.

For their part, the Martens are very grateful to over 40 people from their church and community (and some as far away as Vancouver) who helped clean out their house and assisted in other ways over many days. The barn and house will need complete renovation and

decades of memories have been destroyed.

However, on top of the devasting flood, on the weekend of December 11th, the Martens’ house and property were looted along with other nearby properties. “We saw them in our fields and got the police and some people were arrested,” Martens says. “I’d gone through a lot of emotions by that point, but I hit a new low when we discovered we’d been looted.”

Getting feed to farms

When the flood hit on November 15, it was all hands on deck for those at Trouw Nutrition and other companies in terms of getting feed to farms. Trouw has a mill in Chilliwack, B.C., on the east side of flooded zone, which was also cut off from ingredient supplies. Regional

The impact of the BC flood: a snapshot

Monday November 15th.

province

The Sumas Prairie area in the Fraser Valley east of Abbotsford was flooded and is home to most of B.C.’s poultry, dairy and pig farms

Sixty-one poultry farms were directly affected.

Water levels rose extremely quickly and the vast majority of the birds died by drowning.

In December, it was reported that 628,000 birds (broilers, broiler breeders, layers and turkeys), 12,000 hogs and 420 dairy cows/calves had died, with 110 beehives also destroyed

The historic rainfall shattered more than 20 daily provincial records.

Many types of assistance were provided and some financial help is available.

In November, a series of atmospheric rivers led to catastrophic flooding and mudslides in an area of B.C. known for its poultry farming industry.

The flood hit

The

declared a state of emergency on November 17th.

sales manager Jared Webster explains that on Tuesday the 16th, Trouw and other local feed mills started holding conference calls to collaborate on getting feed to farms.

“We split up customer lists so that each

feed mill would serve farms closest to it,” Webster says. “As a company, we worked around the clock with local emergency officials to nail down access routes and our drivers were amazing. They had to navigate in knee-deep water during the

HEADS UP!

SYSTEMS OPERATE AT DIFFERENT HEIGHTS TO PROMOTE EFFICIENT NO-SPILL DRINKING

Dedicated FEMALE drinker system with Big Z Shielded Drinkers.

HEADS UP DRINKING™ takes into account what broiler breeders have to do in order to drink - namely, lift their heads and let gravity do its work.

By incorporating gender specific drinker lines and gender specific Big Z Drinkers, water spillage is eliminated as the drinkers are positioned at the proper height for both males and females. The advantage with no-spill drinking is a healthy, ammonia free and a more productive breeder environment.

Benefits of Ziggity’s Broiler Breeder Concept include:

• Dramatically improved male uniformity, livability and performance

• Dry slats and litter means virtually no ammonia release

• Improved bird welfare

• More hatching eggs and improved hatchability

• No bacteria-laden catch cups

The Poultry Watering Specialists

night to deliver to farms they had never delivered to before. For one driver, the water on one farm was higher than his boots when he arrived, so he went in his bare feet to fill the farm’s feed bins. We all worked 24/7 for three weeks straight.”

By the week of December 8th, Hwy 1 (the TransCanada) was opened, along with other roads and rail lines. “I’m really impressed by the collaboration of our industry to make sure we could feed all the animals,” Webster says. “We learned a lot but we all hope this won’t happen again.”

“It’s one day at a time. I look for a glimmer of hope every day to find something positive.”

Recovering and rebuilding

Brittain reported in December that as the water receded, poultry associations have helped farmers clean and disinfect their farms so they can be ready to place new birds. Support will be provided in whatever form is needed, as long as it’s needed. “Everyone has been working very hard and we’re going to get out of it,” says one B.C. poultry veterinarian who doesn’t want to be named, “but there’s still a lot of work ahead.”

Heavy Duty Big Z Drinkers are twice the size and weight of

Learn more about Ziggity’s exclusive HEADS-UP™ breeder watering system at ziggity.com/HeadsUp

Like other farmers, Martens has been moving forward diligently since the flood. Some of the chicks intended for their farm were taken by other producers, which provides some income, and the Martens are luckily in a position to grow a remaining portion of their quota at their barn at another location that hasn’t been used for a while. Martens’ 95-year-old father Erwin lives nearby (his mother died some time ago). “He’s

Dedicated MALE drinker system with Big Z Drinkers.

Big Z TL

very supportive and is helping tend the chicks while I am busy coordinating the re-build,” the producer says.

However, the financial picture is difficult for him.

“Because it was an overland flood, the insurance company has rejected both flood damage and business interruption claims,” Martens says. “But rejection of the business interruption claim is hard to comprehend. I

am covered for loss of the last flock, which almost cover the feed costs for the last flock.

“Some of my quota has been leased out to other producers, which will provide some income over time, as will the birds on other farm. I’m hopeful my bank will provide bridge loans until compensation comes from the federal and/or provincial government. They need to step up. The costs to get the house and barn back to normal are many hundreds of thousands of dollars. The government also has to get involved in regulating the insurance industry in Canada.”

Martens notes that if the B.C. government and the federal government had not ignored recommendations from at least two reports on protecting the Sumas Prairie, this flood would have been prevented. The Sumas Prairie was once a shallow lake that was drained in the 1920s. “We are only 1,000 voters in this area but we produce a very large amount of food,” Martens says. “The government needs to get its chequebook out.”

He adds, “It’s one day at a time. I look for a glimmer of hope every day to find something positive.”

You welcome Cumberland on your farm because you expect performance. We welcome the opportunity. To help you reach your potential, with the highest quality systems you can count on and real support when you need it. So, you can raise your best birds and grow a thriving business.

Farmer Dave Martens lost 40,000 chickens due to the flood in Sumas Prairie in Abbotsford, B.C.

Functional feed

Can diet help broilers manage heat stress?

By Jane Robinson

Broilers in the finishing phase naturally generate a lot of heat. They are actively adding weight, and a high metabolic rate produces more body heat. Add in the potential impact of external heat stress as global temperatures rise, and broilers are dealing with heat stress that impacts productivity, and possibly welfare.

To take a closer look at ways to alleviate heat stress, a Saskatchewan research team is working together with an international micronutrient company to investigate the role of nutrition in managing heat stress in broilers.

Drs. Karen Schwean-Lardner and Denise Beaulieu of the University of Saskatchewan are collaborating with German-based Evonik Nutrition on a threeyear project looking at how to precisely formulate diets to deliver the appropriate ratio of ingredients broilers need to grow under heat stress. They’ll be studying the impact of changing the bird’s diet during the finisher phase on reducing heat stress.

“Evonik approached us because they were interested in whether we could help alleviate some of the heat stress broilers experience by changing nutritional components of the diet,” says Schwean-Lardner, an Associate Professor of poultry science in the Department of Animal and Poultry Science. “There has been work done recently on heat stress, but we are looking at some different components of the diet and different interactions.”

Schwean-Lardner recruited graduate student Dilshaan Duhra for the project. “I had been working on my masters in British Columbia during the 2021 heat wave, and when I saw the impact on animals it got me interested in studying heat stress,” says Duhra, who is working on his PhD as part of the project.

Heat, nutrition and productivity

All research trials are being conducted at the University of Saskatchewan’s Poultry Teaching and Research Facility, a site specially designed with rooms that can be

individually controlled for research purposes and also closely replicate an on-farm setting.

To create a heat stress environment, heat is cycled through bird pens, with 12 hours of increased temperatures followed by 12 hours of normal temperatures, each day during the approximately 14-day finishing phase. This environment will be used in all replications of each trial used to compare different diets.

Every bird is exposed to the cycling heat stress to allow the team to zero in on the effect of altering nutritional components. To evaluate the impact of different diets, Duhra is analyzing and comparing body weight, feed intake, feed-to-gain ratios, meat yield, health status, physiological biomarkers and other welfare factors.

What’s particularly interesting for Schwean-Lardner is the step-by-step approach of the research. The results of each year’s work will feed into the adjustments made to the diet components of the broiler finisher diet for the next year.

Broilers are cycled through 12 hours of increased temperatures followed by 12 hours of normal temperatures each day to study the effect of altering nutritional components on heat stress.

Year one feeding trials have finished, and Duhra is analysing the results. “We are looking at how the amount of starch, lipids and proteins will affect animal performance when the birds are under heat stress,” explains Duhra. “We looked at the starch to lipid ratio – in combination with the energy content of the diet – to see how these components interact with each other to influence the bird’s performance under stress.”

Duhra expects to have the year one analysis completed this spring, with the second feeding trial starting in early fall.

Research has already shown that increasing dietary fat in the diet helps alleviate heat stress, as well as decreasing crude protein. Schwean-Lardner says it’s already known which amino acids are limiting in the broiler diet, so they will seek to optimize amino acid concentrations when birds are under heat stress.

What about welfare?

For Schwean-Lardner, another interesting element of this research is to look at the welfare angle. “When broilers are under heat stress, a lot of things happen,” she says. “They become very inactive and lay on litter, which results in a reduced opportunity to dry. So birds are having more contact with that wet litter – leading to lesions in the foot pads, hocks and even the breast. If we can address that by changing components in the diet, maybe birds will be more active and we won’t see as many lesions. We don’t know the answer but hope we find some.”

A recipe to reduce heat stress

This research presents a unique opportunity for research/industry collaboration. “Working together with Evonik is a great experience to help develop practical solutions for the broiler sector,” says Schwean-Lardner. “Our ultimate goal is to create a recipe for managing heat stress that will provide nutritionists and producers with the best approach for feeding through the finishing stage to reduce the impact of heat stress on productivity.”

Broiler breeder male management

Using data to solve problems.

By Pieter Oosthuysen

Modern technology is increasingly being used on breeder farms, creating increases in data generation. The farmer can analyze this data to make smarter decisions to improve flock performance and efficiency. As genetics improve yearly, so will efficiencies and production performance.

But are improvements in line with expectations? And how does an operation compare itself to top-performing operations? Comprehensive data collection provides opportunities to predict future performance, supply chain demands, and future results. If the expected outcome is not achieved, then datasets are available to understand the issues.

Many breeder farmers are only using paper records and little electronic data. Conversely, some operations generate so much data that it becomes messy. Some data are unreliable due to staff completing tasks hastily such as weighing while also collecting eggs. Good data collection is important since many critical decisions, including feed allocations, are based on reliable bodyweight data.

Technology will never replace stockman skills needed for successful flock management. There are many missed opportunities where farmers and workers have missed vital and negative behavioural signs that affect flock performance. Many consultants offer data analysis services but lack the experience of stock-

man skills and breeder management. Interpretation of the data requires local knowledge such as seasonal effects or knowledge of breed-specific behavioural traits. For example, a consultant could possibly state that heavy hens produce fewer chicks.

However, the relationship is multifactorial because as hens age, they become

heavier and egg production declines. Moreover, chick production is a function of both fertility and hatch of fertile (incubation). Furthermore, fertility is most often attributed to male management, but it is female-related on rare occasions. Objectivity and experience are important when interpreting suboptimal performance data using regression graphs.

By analyzing data, broiler breeder farmers can learn how to improve flock performance and efficiency.

Pieter Oosthuysen is senior manager, accounts and technical (Africa) with Cobb Europe.

<i>Pieter Oosthuysen is senior manager, accounts and technical (Africa) with Cobb Europe.</i>

Comparing a farm’s performance to industry standards is a basic first step when analyzing data. It only shows how the farm compares to the industry. Data that can help to improve flock productivity and profitability is key, and with roosters, it is reflected in weight, condition, feed intake, and fertility.

In the production of hatching eggs or chicks, reproductive performance is always the main driver. The old adage, “If you can measure, it you can manage it” is very true, but how do you measure a certain biological event that cannot be measured or weighed?

First, find a way to quantify it, then work out the measurements and, finally, collect the data. For example, how do you know if the males are getting enough feed? How do you know the cause of low early hatchability or poor peak percentage of hatchability? This is where stockman skills are very important because the measurements are subjective but need to be quantified to produce data.

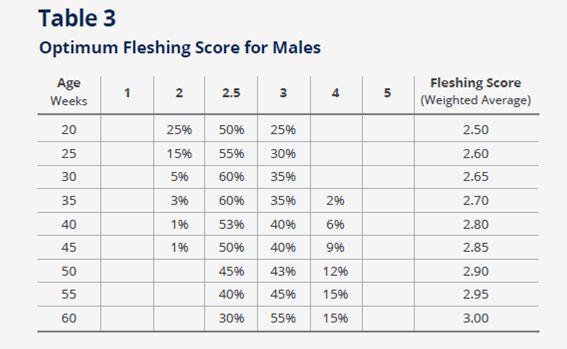

In the field case below, the breeder males were overweight and fertility was declining. The production graph indicated the males were heavy and considerably above their weight for target age. At the farm, the condition of the males was quantified based on a breast muscle scoring system (Figure 1). The male breast scores are explained in Figure 2 (see online).

In Figure 1, 65 per cent of the males had the desired fleshing score of 3, while 15 per cent of the males were too thin and 10 per cent were emaciated. Only 10 per cent were well developed with a fleshing score of 4, leaving no males with fleshing scores of 5, which would be deemed over weight and unfit for reproduction. This means that 75 per cent of the males were in good reproductive fitness condition, indicating they were not overfed.

The remaining 25 per cent were off target for 36 weeks of age, indicating that they may not be receiving enough feed, although they appeared “overweight.” Based on the bodyweight data alone, it appears the males were underfed to control the weight. This demonstrates the difference between weight and size the farmer experienced. Therefore, we increased the feed and fertility began improving. Figure 3 shows the fleshing target table based on ages.

In another case study of declining hatchability, the farmer collected and kept weekly breast scoring records for each house. There were 23 houses totaling 15,000 males represented in the data (Figure 4). Figure 4 indicated that the males develop rather fast in their fleshing scores from 23 to 35 weeks of age. The scores 3 and 4 increased too rapidly. The thinner males with scores 1

Figure 1: Male fleshing scores of a flock considered over weight.

Figure 3: Optimum fleshing scores for males.

Figure 1: Male fleshing

Figure 3: Optimum fleshing scores for males.

Figure 4: Hatchability and male fleshing conditions of 23 flocks and 15,000 males.

and 2 were well managed since their numbers declined and remained a small portion of the population. This would indicate that these males were removed.

The remaining males with a score of 3 reached a point at 35 to 40 weeks where they rapidly increased fleshing scores of 4 and 5, with a corresponding decline in score 3 males. This is the result of early and rapid increases in feed allocation through 32 weeks. Ideally, 70 per cent of males should score 3 as long as possible for optimal fertility.

In Figure 4, hatchability data was graphed with the fleshing scores. It is interesting to note that the decline in hatchability began around the same time as the decline in score 3 and corresponding increases in scores 4 and 5. This indicated that the males became too heavy to continue mating, and over time

the hatchability declined as the males developed bigger breast muscles. Using the data, it was ascertained that males

were overfed in early production (23 to 32 weeks). Therefore, producers can adjust future feed intakes to control early muscle development and improve the hatchability through conditioning males after 40 weeks.

Another important key performance indicator of males is their weekly weight gain. Following 32 weeks, they should gain very little weight (20 g to 25 g per week), and even large males should continue to grow.

In Figure 5 (see online), the males had good weekly weight gains after 30 weeks for a few weeks, and at around 35 weeks, the weight gains ceased abruptly. At that point, they started losing conditioning, so much so that by 40 weeks, they were losing weight. The decline in growth or weekly gains after week 36 had a direct impact on the percentage of fertility, which dropped by 4 per cent.

As seen in these examples, it is important to record measurable performance data. When there is a sudden change in production, the data can be used to identify the cause and prevent it from recurring in future flocks.

Figure 3: Optimum fleshing scores for males.

Figure 4: Hatchability and male fleshing conditions of 23 flocks and 15,000 males.

Figure 4: Hatchability and male fleshing conditions of 23 flocks and 15,000 males.

FARMER RESOURCE PORTAL

Chicken Farmers of Canada has released a new set of videos on the topic of pathogen reduction. The series features farmers, vets, and industry experts sharing best practices and advice.

Topics include controlling traffic in and around the farm, pest control and disease management, barn preparation, bird management, coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis, and cleaning & disinfection.

Check out the new video series and more at:

HPAI returns to Canadian shores

A close look at the threat for poultry, a global summary of the situation and the latest on prevention strategies. By

Treena Hein

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has once again reached Canadian shores.

By January 9th, two poultry sites in Newfoundland had confirmed outbreaks of HPAI, an H5NI sub-type that’s been recently circulating in Europe. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has stated that because these infected sites are not commercial, Canada maintains a status of “free from Avian Influenza.” HPAI hasn’t been detected in Canada since 2015, according to the World Organisation for Animal Health.

The two operations in Newfoundland are located on the Avalon Peninsula. At a hobby farm normally open to the public called Lester’s Farm Chalet, 350 birds of various heritage breeds died of infection in December and another 60 (including geese, peacocks and an emu) were euthanized to contain spread. At another premises with a small backyard flock,

three chickens died of infection in early January and the remaining 14 birds (ducks) were euthanized. Both locations had ponds where the domestic birds could mingle with wild birds.

CFIA quarantined both infected premises and established 10 km control zones around them with restricted movement and enhanced biosecurity. Government personnel are keeping in close communication with commercial poultry farmers in the province as well as with owners of backyard flocks. The public has been asked to refrain from feeding or handling wild birds such as ducks, pigeons and gulls.

Government agencies are also monitoring the presence of the H5N1 virus strain in wild birds in Newfoundland and beyond, after it was recently confirmed in wild birds in the province, and by mid-January, in South Carolina and North Carolina. It’s believed the strain may have reached North America when a major North Atlantic storm hit in early October 2021, perhaps

carrying in infected wild birds from northern Europe. It’s been confirmed that two novel European geese species are now present in Newfoundland.

However, Dr. Andrew Lang, a professor in the Department of Biology at Memorial University in Newfoundland, notes that, “We can’t know for certain how the virus arrived. It may have gone through Iceland or Greenland or it could have been that storm. We know that European barnacle geese are certainly being heavily impacted in Europe by this strain. It’s perpetually circulating in Europe and since spring 2021, we’ve seen prolonged outbreaks there, which is a new development.”

In addition to causing devastation in kept flocks and killing wild birds as well, this HPAI strain has the potential to cause disease in humans through direct contact with infected birds and contaminated environments. The risk to the general public is very low. Most human cases involve mild flu symptoms. There have been

Government agencies are monitoring the presence of the H5N1 virus strain in wild birds in Newfoundland and beyond after it was detected in a great black-backed gull collected at Mundy Pond in Newfoundland.

a few cases of AI in humans in 2021, and in early January 2022, an elderly man in England who has kept pet ducks at his home contracted this strain, but reported feeling well.

In 2021, a total of 40 countries experienced HPAI outbreaks and almost all cases have involved H5N1. Since September, at almost 900 locations around the globe, close to 35 million birds have been culled to control spread. Countries hit hardest to date, in order, are Italy, Hungary, the U.K., Poland, Germany and France. In Asia, South Korea, Japan and Taiwan have had significant outbreaks.

DETERMINING RISK

Dr. Tom Baker, incident commander at the Feather Board Command Centre (FBCC) in Ontario, explains that there are two risk factors that are normally considered in any potential change to a province’s ‘alert status.’

One is the potential presence of highly pathogenic AI strains in wild birds in the province or region. Regarding Ontario, according to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative, close to 10 per cent of live migratory waterfowl surveyed in the province in 2021 were carrying the H5 AI virus, although none found to date were highly pathogenic. Ontario is also within the same flyway as the eastern U.S. seaboard area, which may mean that the H5N1 strain that’s recently been detected in Newfoundland and the U.S. could arrive in Ontario this year.

The second risk factor – the chance of commercial poultry exposure – is difficult to assess in any jurisdiction. “It’s determined by the level of biosecurity in place – protocols and adherence to protocols,” Baker says. “Having said that, protocols in Canadian poultry are stringent and compliance is regularly audited by the boards. AI outbreaks are the result of biosecurity breaches and human error. There are multiple pathways for this virus to enter our commercial flocks and spread. Contaminated equipment or personnel apparel can carry this virus into a poultry barn.”

Backyard flocks exposed to infected wild birds could

become infected and potentially spread to commercial flocks, but it’s unlikely. The entire industry adheres to biosecurity protocols and, also, commercial poultry veterinarians and other service providers generally do not visit backyard flocks, nor vice versa. “These are different worlds,” Baker says, “and good biosecurity requires that there be absolute separation.”

In addition, small flock owners generally understand the importance of preventing contact between their birds and wild birds, but Baker notes that even commercial confined poultry could occasionally come into direct or indirect contact with wild birds that get into the barn.

“Obviously anyone with a backyard flock or freerange commercial operation should prevent interaction between their birds and wild birds and their habitats,” he says. “In Canada, outdoor access is required for organic poultry production, but when outdoor access represents an imminent threat to the health and welfare of poultry, access may be restricted.”

In the U.S., the precautions look to be similar to Canada. Guidelines have been provided to prevent AI transmission from wild birds to commercial birds. In the Implementation Plan for AI Surveillance in Waterfowl in the U.S. 2021-2022, various agencies outline how AI surveillance in wild birds is being conducted (mostly through wild bird sampling).

“Maintaining a high level of awareness amongst farmers is key to preventing an avian influenza outbreak.”

Baker reports that in Europe, where there have been so many AI outbreaks, authorities have imposed additional biosecurity measures. These include housing orders for free-range poultry operations to prevent commercial poultry from interacting with wild birds, prohibiting hunting by poultry workers and the banning of poultry fairs and markets, shows and races.

Despite the best prevention measures, preparedness is key. Baker notes that in Ontario, there are now 138 board and industry staff trained and certified as emergency responders. “In the event of an outbreak, they

Experts say avian influenza outbreaks in commercial poultry are usually the result of biosecurity breaches and human error.

HPAI quick facts

• Currently present in Africa, Asia and Europe, HPAI is a threat to economic stability, food security and livelihoods.

• Commonly known as bird flu, AI is a very contagious disease that affects several species of poultry as well as pet birds and wild birds.

• In 2021, an unprecedented genetic variability of subtypes has been reported in birds.

• H5N1, H5N3, H5N4, H5N5, H5N6 or H5N8 are the subtypes currently circulating in poultry and wild bird populations across the world.

• Most outbreaks occur during the winter of the Northern hemisphere. Outbreaks usually begin to increase in October, peak in February and continue through April.

Source: World Organization for Animal Health

will assist our government partners,” he says. “Regular simulations evaluate our readiness. In addition, the FBCC Board has recently expanded beyond a farmers’ organization to include all strategic partners in the Ontario poultry industry.

“FBCC has also partnered with Farm Health Guardian, which features geofencing and GPS technology to conduct a simulated disease outbreak, and track the movement of staff, visitors and vehicles in and out of farms in real time. Our hope is that this technology will allow for more risk-based mapping, speed up the notification process and facilitate trace backs.”

In addition, Ontario is strengthening systems for rapid culling operations and disposal of dead animals and contaminated waste. Poultry producers in provinces such as Ontario have also invested in strong AI insurance programs that cover losses beyond the CFIA compensation program.

Overall, Baker says, “Maintaining a high level of awareness amongst farmers is key to preventing an AI outbreak. In addition to following established protocols to the letter, all farmers must be aware of their farm-specific risk vulnerabilities and ensure these are controlled or mitigated.”

GET IT RIGHT THE FIRST TIME

When it comes to poultry systems, you can’t a ord to get it wrong – especially when industry standards are constantly changing. Count on Chore-Time to give you the right advice. The right innovative solutions. And the right customer support. It’s what we’ve been doing since 1952.

Talk to your independent authorized Chore-Time distributor today. And get it right the rst time.

Learn more at choretime.com/GetItRight

Chore-Time is a division of CTB, Inc. A Berkshire Hathaway Company

Turning research into action

Global Animal Partnership releases list of Better Chicken breeds following groundbreaking study.

By Lilian Schaer

One of North America’s largest animal welfare food labelling programs has released its initial list of broiler chicken breeds eligible for animal welfare certification.

Global Animal Partnership (G.A.P.)’s Better Chicken breeds list is a direct result of a wide-ranging University of Guelph study into slow-growing broiler chickens and chicken welfare that offered fascinating insights into the connections between modern poultry production and bird welfare.

The organization used those study findings to guide development of its Broiler Chicken Assessment Protocol and its initial list of Better Chicken eligible breeds.

It currently includes approved crosses from Aviagen, Hubbard, Cooks Venture and Cobb-Vantress.

G.A.P. first started working on revising broiler chicken standards in 2015, and according to executive director Anne Malleau, the process involved extensive stakeholder involvement with a scientific committee, producers, animal advocates and nutritionists, as well as public comment on proposed standards.

Feedback made it clear that although some issues could be addressed through a

welfare standard, others could not – particularly because traditional welfare standards were largely based on growth rate parameters.

“We were hearing that birds are harder to raise and that there were meat quality issues, but we were basing all of our decisions on data that didn’t reflect our program. For example, we are antibiotic-free, so that diet is different from what is used to develop growth tables,” Malleau explains, adding that G.A.P. certifies 416 million animals annually, of which 390 million are broilers.

“And from a consumer standpoint, how do you tell them that 52 grams per day (of growth) is better than 54? That means zero to them,” she says. “There was a fair amount of interest to try and do something about this – and when we first started, we talked about slower-growing birds, but it’s not about fast or slow. We

don’t want to turn the clock back to the 1920s and we’re not activists trying to get rid of meat production. We are just focused on animal welfare.”

Scientific approach

Ultimately, that led to a decision to take a scientific approach to the issue. G.A.P. commissioned a comprehensive study led by animal biosciences professor and Egg Farmers of Canada Chair in Poultry Welfare Tina Widowski, who was supported by a team of University of Guelph poultry welfare, nutrition, physiology and meat science experts.

The two-year study included more than 7,500 chickens from 16 genetic strains bred for four different growth rates (conventional, fastest slow strains, moderate slow strains and slowest slow strains) as well as other traits and raised over eight trials.

“Overall, we found that many indicators of welfare are directly related to the rate of growth,” noted Widowski in an interview last year.

Faster-growing birds had lower activity levels and were less mobile, and were more likely to have breast muscle damage such as woody breast or white striping, poor foot health and potentially inadequate organ development.

Applying the findings

Following release of the final report in July 2020, G.A.P. sent up a technical working group that included scientists, producers, animal advocates, and breeders to review the findings and discuss how the findings could be applied.

“We did things methodically; we started at the beginning and worked forward. While we had huge trust and faith in the study, it wasn’t meant to be the only thing

G.A.P.’s initial list of Better Chicken eligible breeds includes approved crosses from Cooks Venture, pictured here, as well as from Aviagen, Hubbard and Cobb-Vantress.

we were thinking of and by addressing things methodically, you can get buy-in and engagement and work through issues,” Malleau says. “There is no way that applying 65 variables is an economically viable solution so it’s about nice to have versus must have. Bringing people through that process was very important.”

According to Malleau, the Guelph study results provided metrics to develop a protocol to determine which breeds will have good welfare outcomes without simply relying on the traditional growth rate parameters. All the work was done blind, she noted, so no one had any preconceived notions about the breeds being evaluated and the outcomes could be kept as objective as possible.

G.A.P. is now working on a transition program for its partners to begin switching to the Better Chicken-approved breeds. This will include a label to clearly identify chicken that is both G.A.P.-certified and from a Better Chicken breed.

This will be available in the U.S. this year, but although G.A.P. has Canadian partners in Ontario and British Columbia, those conversations around transitioning to Better Chicken breeds haven’t taken place yet, Malleau says.

“There are many different players involved, and transition (to Better Chicken breeds) will be related to the ability to segregate,

processing time and having a market for all parts of the bird. You need to worry about carcass utilisation and processing minimums,” she says.

“It’s different than cage-free eggs where the egg tastes the same; here you will have different taste profiles, so there will be a certain group that will go out as early adopters.”

It’s also going to come with price, with birds growing a bit more slowly and taking longer to get to market, but some of that may be offset by lower mortality and condemnation rates. And with growing consumer interest in plant-based alternatives, animal-free meats, or cellular products, welfare-friendly chicken breeds could play a key role in the industry’s future.

“I think it is a way for the chicken industry to have a sustainable way forward that could help keep people eating chicken, but doing it mindfully and addressing questions and issues we know are there,” she says. “Transition will come in fits and spurts, but we are committed to a sustainable transition and bringing everybody along.”

Breeding companies interested in testing additional breeds using G.A.P.’s new protocol are asked to contact G.A.P. directly; more information on the Better Chicken breeds is available at globalanimalpartnership.org.

intake:

What’s going on in the gut?

Modelling helps study microbiome to improve poultry health.

By Jane Robinson

One of the biggest questions facing the Canadian poultry industry is how to maintain bird health with less reliance on antibiotics. University of Guelph’s Dr. Shayan Sharif is looking for solutions from a number of different angles with a diverse team of researchers from across Canada.

It’s not a simple, straightforward task. “The challenge to reduce our reliance on antibiotics while maintaining poultry health is a multifaceted one, and it requires a multi-pronged approach,” says Sharif, Professor and Associate Dean of Research and Graduate Studies, Ontario Veterinary College. That bigger picture view included reaching beyond the poultry researcher realm to partner with Dr. John Parkinson, a senior scientist at Sick Kids Hospital in Toronto. “John is a world-renowned expert in studying intestinal microbial communities, and he brings an incredible knowledge and experience through his research on human intestinal microbes,” says Sharif. Parkinson is focused on two main areas related to creating a healthy gut microbiome to support overall bird health. He’s been testing a number of dietary additives in broiler feeding trials to study the impact on bird health. And he’s developed a computer model to better understand how different gut bacteria interact and the consequences to the bird.

Researchers have been focused on finding ways to create a healthy gut microbiome to support overall bird health.

Parkinson has a long-standing interest in infectious disease, and more recently became interested in the impact of pathogens on gut health by studying the microbiome, or bacterial community, in the gut. Through the course of his work he realized much can be learned about the human microbiome from other species, including mice and poultry, which eventually led him to connect with Sharif on this research.

FEEDING THE COMMUNITY

Working in collaboration with animal nutrition manufacturer Lallemand, Parkinson and Sharif are interested in studying how additives including prebiotics and probiotics alter the bacterial community, and which ones help birds establish a healthy gut microbiome early in the chick’s life.

In these studies, probiotic additives are being monitored to measure the impact on bird health, specifically the bird’s

boosted ability to withstand infections from pathogens including Clostridium perfringens – the primary pathogen causing necrotic enteritis, as well as the food safety pathogens, salmonella and campylobacter. “Improving the microbiome and overall bird health will also improve food safety down the value chain by reducing the occurrence of pathogens of concern,” says Parkinson.

Parkinson and Sharif are not just focused on revealing how additives change the gut community, they are also applying cutting edge methods to understand what the consequences of these changes are. “Traditionally, studies of the microbiome have looked at what types of bacteria are present. What we are more interested in is what they are actually doing,” says Parkinson.

Parkinson’s group is currently analysing data from a trial performed with Dr. Doug Korver at the University of Edmonton to study the functional consequences of probiotics provided by Lallemand.

From the positive findings about the promising role of antibiotic alternatives in promoting gut health and bird health, Parkinson imagines a time when feed additive recommendations could be customized on a barn by barn basis, based on the gut health status of birds and makeup of the bacterial community in the microbiome. “I know that when we talk about a new product for widespread use on farms, we need to be sure the economics make sense, so we are very aware that cost-effective solutions are paramount,” says Parkinson.

The findings from this research will have direct implications for broilers and layers, and some of the strategies they develop may also apply to turkeys, according to Sharif.

MODELLING THE IMPACT ON GUT HEALTH

The second part of Parkinson’s project benefits from his previous work in computer modelling the microbial community to predict the effect of additives on gut health.

He created a computer model that pulls in layers of data and information – including the feed trial results – to predict the impact of particular additives on gut and bird health. “We already know which bacteria are in the chicken microbiome,” says Parkinson. “And with the feeding trial data, we are able to put these pieces together to predict the outcomes of various feed ingredients.”

One of the main ways to measure the impact of additives on bird health is to determine the metabolites produced in the gut from the addition of prebiotics or probiotics to the diet. “We are most interested in the ability of certain feed additives to produce short chain fatty acids that are known to promote a healthier chicken gut,” says Parkinson. “So, when we alter things like prebiotics or probiotics, the model shows how

these alter gut health and the bird’s ability to fight infection from pathogens like clostridium, salmonella and campylobacter.”

BARN-TESTING THE MODEL

With the computer modeling up and running, Parkinson will now work with Sharif to see how the model works outside the lab. “We’ve been predicting the effect of additives on the bacterial community in the microbiome, and now we want to test those predictions on live birds,” says Parkinson.

They’ve identified additives that, in theory, alter the microbiome of the chicken and produce more short chain fatty acids in the gut.

Next up are feeding experiments with broilers at the University of Guelph over the next few months to see if the models work in real life.

When that work is complete, Parkinson and Sharif will collaborate on another project to start developing a new probiotic product to support the microbiome and better bird health.

Not all poultry farmers maximise the full potential of their birds. Both kept in cage or floor systems, for a good performance during the production period, the management should be correct and efficient.

But how do you know that what you are doing is right? Your chickens continuously send out signals: about their health, how well they know their way around their surroundings and whether they feel happy and comfortable.

Layer Signals is a practical guide that shows you how to pick up the signals given by your animals at an early stage, how to interpret them and which action to take.

$69.99 Item #9087401245

Dr. Shayan Sharif, professor and associate dean of research and graduate studies, Ontario Veterinary College.

Dr. John Parkinson, a senior scientist at Sick Kids Hospital in Toronto.

“We hope this microbiome work will bring safe and efficacious antibiotic alternatives.”

“We hope this microbiome work will bring safe and efficacious antibiotic alternatives to the Canadian poultry industry to improve gut health, and also improve the quality and safety of poultry products for Canadian consumers,” says Sharif.

PREBIOTICS VS. PROBIOTICS

Prebiotics are metabolites such as insoluble fibre or oligosaccharides that can be added to the diet. While prebiotics are fed to chickens, they are designed to “feed” the bacteria in the gut (microbiome). Chickens can’t make nutritional use of prebiotics.

Probiotics are living organisms and can consist of single strain bacteria (Lactobacillus) or a community of bacteria. Some probiotics are actually cultured from chicken caecal material, freeze dried and used in chick diets. Probiotics work by adding good bacteria to the chicken gut to produce a better overall community of beneficial bacteria in the microbiome.

This research is funded by the Canadian Poultry Research Council as part of the Poultry Science Cluster which is supported by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada as part of the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. Additional funding was received from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, George Weston Seeding Food Innovation, Alberta Agriculture Funding Consortium, Lallemand Inc. and Compute Canada.

• Exacon’s brand name since 1987

• Polyethylene or fiberglass flush mount housings available in white or black

• Designed to meet the rigorous demands of farm/agricultural ventilation

• Energy efficient Multifan, MFlex, or AGI motors

• Available in sizes ranging from 12” to 72”

TPI WALL AND CEILING INLETS

• Produced out of high-quality polyurethane, TPI inlets are designed to optimize airflow

• High insulation value is ideal for cold weather climates

• Easy to assemble, maintain, clean and adjust to meet your specific ventilation needs

• Wall inlets, ceiling inlets and tunnel inlets

• TPI wind hoods are available with a builtin light trap option

MULTIFAN V-FLOFAN

• The V-FloFan creates a uniform climate in poultry houses

• Equipped with a water and dust resistant

IP55 rated, low noise

Multifan motor

• Helps control the humidity of the litter resulting in an active microclimate at bird level

• Special aerodynamic shaped conical outlet optimizes vertical airflow contributing to lower energy costs