TREENA HEIN

BY MADELEINE BAERG

Consumers are busier than ever, leading them to prioritize convenience. Here’s how meal kits are helping to fill that need and what it means for poultry.

BY TREENA HEIN

by Brett Ruffell

TREENA HEIN

BY MADELEINE BAERG

Consumers are busier than ever, leading them to prioritize convenience. Here’s how meal kits are helping to fill that need and what it means for poultry.

BY TREENA HEIN

by Brett Ruffell

One of my favourite times of year is our annual trip out west to the Poultry Industry Services Workshop. Held every October in Banff, Alta., it’s a must attend event, yes, partly for the breathtaking views but most importantly for the vital information and great networking opportunities it provides.

Over two days, experts share the latest research and insights around different aspects of poultry production. One of the most valuable parts of the event is the disease update, which typically kicks things off the first morning.

Each year two vets, one representing Western Canada and another for the east, look back at disease challenges affecting different sectors in each province, their impact, as well as which threats still loom and which ones were dealt with and how.

It’s such a useful update that starting with this issue we thought we’d make it an annual tradition to pass it on to give you the poultry health lay of the land (see page 12). We followed up with this year’s presenters, Neil Ambrose representing the west and Mike Petrik for the east, to expand on their updates and also to share any recent poultry health success stories.

While out west I heard a lot of discussion about how changes to antibiotics use would

impact the poultry health landscape. One interesting topic stood out to me. As you’re probably well aware, not only do you now need a prescription from a vet for antibiotics, but the changes also call for vets to be more active in dispensing these medicines as well.

I learned that some farmers were actually wary of becoming dependent on vets for their antibiotics supply.

“Producers were concerned vets would raise prices on these products if they were the only ones who could dispense,” says David Ross, vice president and chief marketing

“It’s a really interesting challenge –

I love it!”

officer with GVF Group, an animal feed, health and equipment supply company.

The change threatened part of GVF’s business as well. Previously, a good chunk of the company’s antibiotics sales was in large (25 kg) bags. These are popular with poultry farmers who want the ability to quickly react to disease outbreaks. But with the new regulations where access to these medicines is more restricted, GVF was poised to lose that side of its business.

However, Ross had a plan – open a livestock drugstore. After a daunting startup pro -

cess, GVF unveiled Farmers Pharmacy Rx in December. It’s thought to be Ontario’s first independent livestock pharmacy. Now, according to the regulations, with its own pharmacy GVF could fill antibiotic prescriptions it re ceives from vets.

Setting things up was an impressive feat. The company first had to obtain a pharmacy license – it purchased one that was more than 60 years old. Then the facilities had to be approved by the Ontario College of Pharmacists. Last ly, the company had to find the right druggist to man the operation.

Given that livestock is un charted territory for pharma cists, it would be a challenging role to fill. But Chris Mobbs was up for the task. Before he became Farmers Pharmacy Rx’s first pharmacist man ager, the University of Lon don grad had a lengthy career working in traditional retail drugstores like Rexall.

Now that he’s a pioneering livestock pharmacist, it’s a whole new learning curve.

“Everything we learned in humans is different in ani mals,” says Mobbs, who’s tak ing a veterinary pharmacy course to help him transition.

“But it’s a really interesting challenge – I love it!”

Having spent 10 years cov ering pharmacists for a different publication before joining Canadian Poultry , I have a strong appreciation for their skills and I’m confident they’ll make a good addition to this industry. In fact, Mobbs says he’s already prevented a few big dosing errors!

Editor Brett Ruffell

bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

National Account Manager

Catherine Connolly cconnolly@annexbusinessmedia.com 888-599-2228 ext 231

Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664.3811

Fax: (519) 664.3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Quebec

Tel: (450) 263.6222

Fax: (450) 263.9021 Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963.4795

Fax: (780) 963.5034

Nutrition company Jefo officially announced its plan to build a new 200,000 sq. ft production plant in Saint-Hyacinthe, Que. This new building, estimated at $30 million, will be located in the Théo-Phénix Industrial Park. The area, acquired in 2018, is strategic due to its proximity to the other Jefo Group facilities, which include a transportation company, a transshipment site, research centres for poultry nutrition, warehouses, the production plant and more.

A replica of an Aviagen hatchery and delivery truck are currently on display in a nine-by-36-foot poultry industry diorama – a miniature model exhibited at the Georgia Poultry Lab in Gainesville since 2017. Aviagen is a sponsor of the diorama, and the hatchery shown is based on the company’s Sallisaw, Okla., facility. A video walk-through of the entire diorama is available at gapoultrylab.org/ poultry-diorama.

Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) was named one of Canada’s Top Employers for Young People for 2019. The award recognizes the best workplaces across Canada for young people starting their careers right out of university. EFC’s employee-centric culture and a commitment to giving back to the community are just some of the reasons why young people want to work there, it says. Careers are enriched through professional development and specialized leadership training. Staff have a range of opportunities to grow in their role and take ownership of their projects..

million is the cost of Hendrix Genetics’ broader plan to establish its own turkey poult distribution network across North America.

After the ribbon cutting, guests toured the new hatchery to learn about its cutting-edge automation, incubation and hatching technologies.

Over 400 people, including representatives of the turkey industry, local community members and government officials, recently gathered to celebrate and tour Hendrix Genetics’ new commercial turkey hatchery in Beresford, S.D.

The 83,000 sq. ft facility joins Hybrid’s network of owned and partnered hatcheries that will provide day-old poults to customers throughout North America.

The $25 million hatchery has a 35 million egg capacity and features cutting-edge robotics and automation technologies from Zoetis and incubation and hatching equipment from Petersime.

After speeches and an official ribbon cutting ceremony, guests toured the hatchery to learn about its key features.

Highlights included a demonstration of its hatchery automation and a look inside the

facility’s incubation and hatching technology.

Attendees also learned how eggs will be received, incubated, hatched and then safely transported from the new facility to farmers throughout North America

Hybrid showed off specialized vehicles from Veit and Heering that will transport the day-old poults to family farms throughout the Midwest.

Jeff McDowell, the hatchery’s general manager, kicked off the speeches by highlighting the timeline of just over one year to complete the project.

“I am very proud of what we accomplished in such a short amount of time. This wouldn’t have been possible without the ongoing support of our customers and the local community. This, of course, is in addition to the hard work and dedication of our staff and partners throughout this project.”

Tina Widowski has had a long and distinguished career studying farm animal welfare. She grew up in Chicago and had wanted to become a veterinarian or zoologist, but discovered a love for animal agriculture instead. Farm animal welfare was a relatively new field at the time, and Widowski has greatly contributed to its growth. In 2018, she won the Poultry Science Association Poultry Welfare Research Award.

Why did you study poultry? When I discovered animal agriculture as an undergraduate student, I was inspired by the notion that I could apply that passion to the study of the millions and millions of animals used for food production. The majority of my lifetime work has been devoted to studying pigs and poultry, as these are the food animals that are kept in the largest groups and in close confinement. My goal is to understand and match their behavioural biology with the ways that they are housed and managed in order to meet their needs and the needs of farmers. My current work with laying hens is the perfect opportunity for this since the industry is transitioning to new housing systems.

List some career milestones. I finished a B.Sc. degree in Ecology, Ethology and Evolution, followed by a M.Sc. and Ph.D. in Animal Science, all at the University of Illinois-Urbana, in 1983, 1984 and 1988. I was appointed in the Faculty of Animal & Poultry Science at the University of Guelph in 1998, and appointed director of the Campbell Centre for the Study of

Animal Welfare in 2007. Two years later, I was appointed the University of Guelph Chair of Animal Welfare and two years after that in 2011, I was awarded Research Chair in Poultry Welfare from the Egg Farmers of Canada.

What is your most significant career achievement and why?

My relationships with my students. The most rewarding part of the job is to help young people find their passion, develop their skills, grow and succeed. So many of my students have gone on to successful careers in research and industry and I’m very proud of them.

How would you like to see the industry evolve?

Poultry producers will be facing many changes over the next 20 years. Egg producers will be transitioning to new housing and management systems. Chicken producers will be reducing the use of antimicrobials. All of the feather industries will be looking for ways to ensure environmental, social and economic sustainability. I would like to see the poultry industry view these changes as opportunities. From what I’ve seen, I think that the next generation of poultry farmers will be well-prepared.

What do you do to unwind?

I really enjoy travelling and take every opportunity to see the sights, meet the people and try the foods of all the interesting places around the world that my job takes me to. I also like going for long walks in the forest with my two beautiful yellow Labradors and flying with my husband in our gyroplane.

MARCH

MAR. 11-12, 2019

AWC WEST 2019 Calgary, Alta. advancingwomenconference.ca/ awca

MAR. 12-14, 2019

Midwest Poultry Federation Convention Minneapolis, Minn. midwestpoultry.com

MAR. 23, 2019

PIC Raising Backyard Chickens Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

APRIL

APRIL 3-5, 2019

Conference on Poultry Intestinal Health Italy ihsig.com

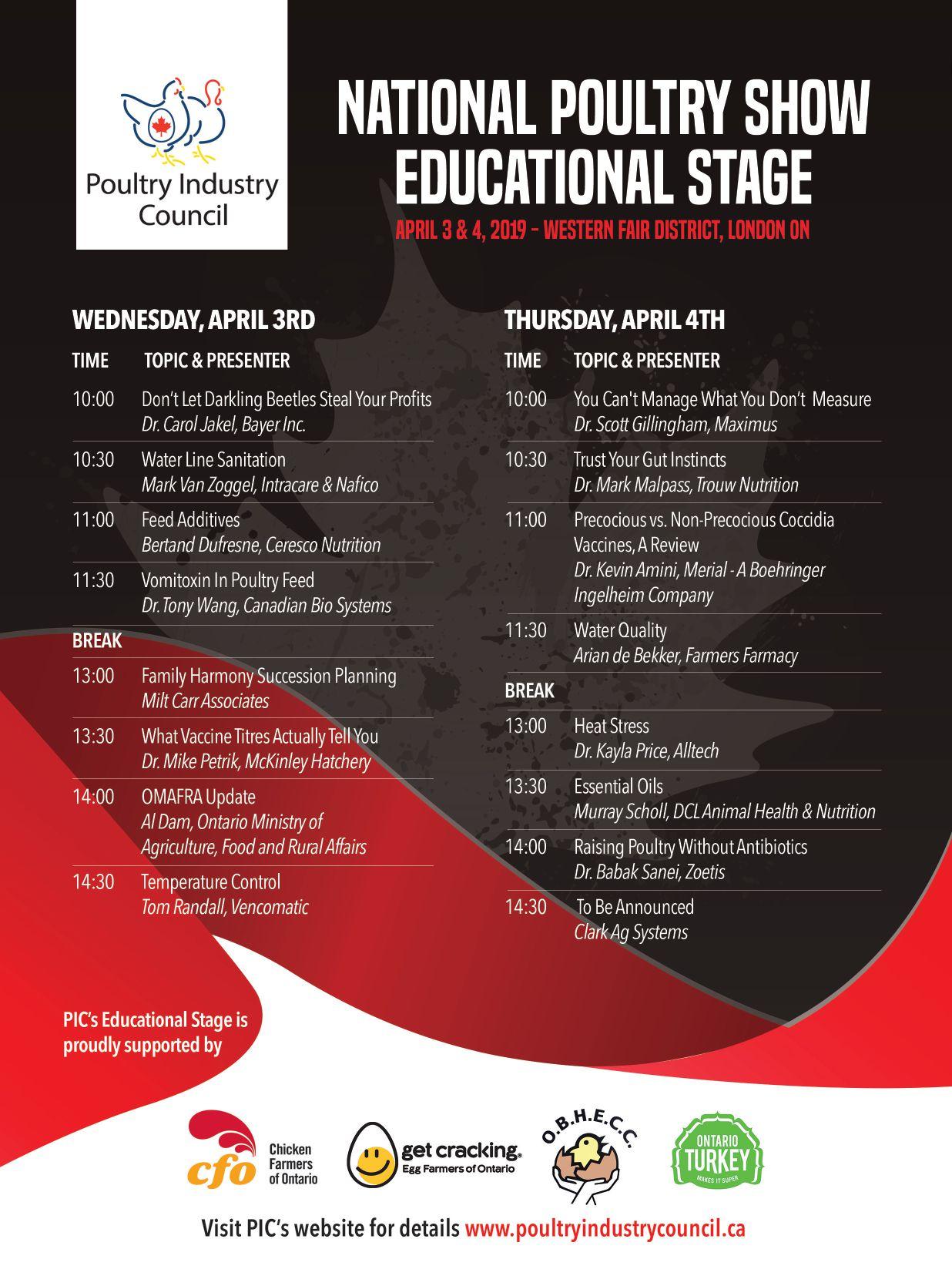

APR. 3-4, 2019

Canadian Poultry Expo London, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

Stay informed on infectious disease outbreaks with the latest alerts from Canadian Poultry Magazine. For more, visit: canadianpoultrymag. com/health/disease-watch

JANUARY 16

Infectious Laryngotracheitis (ILT) United Counties of Prescott and Russell, Ont.

JANUARY 8

Virulent Newcastle Disease (vND) Riverside Country, Calif.

DECEMBER 16

ILT

Saint- Felix-de-Valois, Que.

Health Canada unveiled a radically new food guide in January that eliminates food groups, encourages plant-based foods over meat and dairy products, and is likely to force changes across the country’s agricultural industry.

“I see the food guide as a challenge for many industries. How they adapt will be of interest,” said Simon Somogyi, a University of Guelph professor studying the business of food.

Meat enjoyed a dominant position in the previous food guide with a meat and alternatives category and a recommended two-to-three servings daily for adults depending on their sex and age. It now features meat much less prominently.

The new guide encourages people to “eat protein foods,” but choose those that come from plants more often.

It’s a win for plant-protein farmers, like those growing beans, chickpeas and lentils, but a potential threat to meat producers.

Somogyi believes consumers will favour high-quality beef when they choose to consume red meat and farmers will likely want to shift to producing niche products.

If Canadians eat less meat, there may be opportunities to export to Asian markets where a middle-class consumer wants safe, high-quality cuts.

“If the Canadian beef sector can provide that then their future looks bright.”

The industry may also want to collaborate with plant-protein producers, said Sylvain Charlebois, a Dalhousie university professor who researches food.

He recently spoke to hundreds of

people in the beef industry about the upcoming food guide, who he said were not overly happy with the plant-based narrative, and suggested they “befriend the enemy.”

That kind of partnership could promote a meat loaf recipe that contains beef and lentils, he said.

The new guide also minimizes dairy consumption.

It touts water – not milk – as the “drink of choice” and eliminates the previous milk and alternatives food group.

The visual guide shows a plate topped with a variety of produce, protein and whole grains, but the only dairy pictured is yogurt.

The encouragement to consume less dairy contradicts Canada’s supply management system and doesn’t leave a choice but to rethink the status quo, said Charlebois.

Canadians will eventually buy less dairy as they adhere to the new guide’s recommendations, he said, and grocers will shrink the amount of space allotted to dairy in stores.

Farmers will have to start looking at export markets, and that’s not possible under the current system, he said.

“You’ll end up with an imbalance. So obviously, I think you need to look at supply management 2.0 very seriously and commit to a reform as soon as possible.”

Somogyi suggests dairy farmers eye opportunities in export markets such as rising demand for infant formula in China and parts of southeast Asia.

“In some ways, the guide is a challenge for the Canadian dairy sector to look at what other markets there are and what those products are in other countries.”

Ontario’s Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Ernie Hardeman, recently launched a public awareness campaign to highlight mental health challenges suffered by farmers and encourage people to ask for help when daily struggles become too much to bear. As part of the campaign, Hardeman held a roundtable with members of the agricultural community and had a candid discussion on mental health issues in the sector. The ministry also supports a number of programs to help farmers, including research to evaluate mental health needs for farmers and farm business risk management programs.

Kemin Industries, a global ingredient manufacturer, is commemorating the first year of its expansion into Canada. In January 2018, Kemin acquired the assets of its longtime distributor, Agri-Marketing Corp., and has integrated this business into Kemin Animal Nutrition and Health, which has created more growth in the Canadian market. As Kemin completes its first year of business in Canada, it’s preparing for future expansions and increasing product awareness with Canadian producers.

Canadian Bio-Systems Inc. (CBS Inc.) has launched a new yeast-based feed additive. Yeast Bioactives technology is designed for use as a feed supplement in diets for poultry, swine and ruminants. The company says it fits as an enhanced yeast and grain management option with advantages for all types of production systems..

By Tom Inglis

Tom Inglis is managing partner and founder of Poultry Health Services, which provides diagnostic and flock health consulting for producers and allied industry. Please send questions for the Ask the Vet column to poultry@annexweb.com.

I heard I now need a prescription to treat my flocks as well as a valid veterinary-client-patient-relationship. What is this and how do I get started?

Avalid veterinarian-client-patient-relationship (VCPR) is simply the term given to describe the relationship the poultry farmer and the attending veterinarian share. They work together in common trust to raise birds by incorporating best management practices and state-of-the-art veterinary service. In doing so, they minimize bird health problems, meet accepted welfare standards and provide safe, wholesome food to the consumer. It is similar to the relationship we have with our family physician. It is important to appreciate that a VCPR is a relationship, not a contract, a legal document or an isolated piece of paper. However, there is a mutual need on the part of the poultry farmer and veterinarian to be able to confirm that a VCPR exists if called upon do so.

On December 1, 2018, Health Canada introduced regulatory changes and policies to reduce the development and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) that changed how antimicrobials (antibiotics) are used to prevent/treat infectious disease in food animals, including poultry.

These changes included:

1. Certain medications that were commonly used in poultry production for administration by feed and water will be designated Prescription (Pr). This means a poultry farmer will now need a veterinary prescription before the products can be purchased

Veterinary-client-patient-relationships should improve health and productivity on the farm.

and used on the farm.

2. If feed is to contain one or more prescription products but is used according to approvals on the label, feed cannot be manufactured or leave the mill until the prescription for that feed has been received.

3. Although feed mills can purchase prescription products for the manufacture of medicated feed, they can no longer sell medically important feed additives (category I, II and III antimicrobials) to farms or water administered products (medically important antimicrobials: category I, II and III). Medicated feed additives and water-soluble medications will also not be able to be sourced from farm outlet stores. These medications will

When executed properly, a valid VCPR improves overall health of the operation and does not cost – it pays!

be controlled like they are in human medicine. They will be dispensed only by pharmacists and veterinary clinics (every veterinary clinic is a pharmacy).

4. By provincial regulations, a veterinarian cannot write a prescription for a flock of birds without understanding the operation that raises the birds – a VCPR must be in place. As of December 1, 2018, for a producer to have feed medicated with virginiamycin, bacitracin, tylosin, or medicate a bird with potassium penicillin via the water, a veterinary prescription will be required. A veterinarian cannot prescribe a medication without knowledge of the poultry farm and its operational practices – a VCPR is required.

When birds are submitted to a veterinarian for postmortem without knowledge of the operation, they can render a diagnosis and suggest a possible treatment, but the

important dialogue with the poultry farmer concerning why the birds became sick may be missing.

A valid VCPR is an asset to the farm, as it requires the veterinary practitioner to understand the operation at a level where

they can help prevent future outbreaks of disease. When done properly, a valid VCPR improves overall health of the operation and does not cost – it pays!

Most poultry farmers have participated in a valid VCPR for many years even without having directly paid a veterinarian. It is common in the poultry industry for veterinarians to be hired by suppliers to the poultry operation. However, there are other poultry farmers that have not partnered with a veterinarian in a valid VCPR. If you are unsure if you have a current VCPR, ask:

• Is there a veterinarian who I know well and understands my farm?

• If I had a health problem on my farm which veterinarian would I contact?

If you answer no or I’m not sure, you likely don’t have a veterinarian who would consider themselves as “your vet” and you likely don’t have a valid VCPR. If these poultry farmers continued without a VCPR they would be putting the health and welfare of birds under their care at risk.

On a very practical note, it’s far from ideal for a veterinarian to learn about the operation and get to know a producer and their priorities during a disease outbreak – in fact, it’s a worst-case scenario that may result in delays and potentially costly mistakes.

While the regulations have changed to require a VCPR and prescription to treat food animals, in most cases this requirement should improve health and productivity of the farm.

The poultry farmer and veterinarian must each engage in outreach to find each other. Once they’ve made contact, and realizing that a VCPR describes a relationship, not a document, they can develop a description of the poultry enterprise for a good starting point. For ideas on what to include in that description, see the online version of this story at canadianpoultrymag.com. In summary, a VCPR is necessary and will surely contribute to a stronger poultry industry!

Vets assess current disease threats facing producers from coast to coast.

By Treena Hein

Last fall, poultry veterinarians Neil Ambrose and Mike Petrik together presented a national disease threat overview at the Poultry Service Industry Workshop held in Banff, Alta. Ambrose provided a western overview and Petrik an eastern perspective. Ambrose is director of veterinary services at Sunrise Farms, which has operations in Alberta, B.C., Manitoba and Ontario. Petrik is director of technical services at McKinley Hatchery in St. Mary’s, Ont.

Here we present a summary of their current disease updates. Specifically, we look at what’s stabilized, what’s sprung up and why. While not all the answers are ever apparent, one thing is certain –with the pace of antibiotic phaseout and the industry-wide changes in layer housing, the disease landscape in Canadian poultry production will continue to evolve.

In B.C., turkey producers are mainly seeing bacterial septicemia infections from E. coli, histomoniasis (Blackhead), gangrenous dermatitis and Bordetellosis. Layers are experiencing egg peritonitis,

Marek’s disease/leukosis, cannibalism and infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT). Ambrose notes that there is currently an ILT outbreak in B.C. that appears to be vaccine-related rather than a field strain. He says this emphasizes the importance of a robust and effective vaccination program where vaccines are applied as per label directions only.

In specialty and small layer flocks, Ambrose and others are watching MG/coryza. “It can be a single or duel infection and we’re seeing quite a few cases,” he says.

Broilers are facing bacterial infections from E. coli, such as omphalitis. There are fewer leg abnormalities from reovirus than two years ago, Ambrose adds, with better vaccination in place. There has also been vaccine reformulation for inclusion body hepatitis (IBH) for virus types being seen in the western provinces. Broiler breeders are facing bacterial septicemia from E. coli/staph, Salmonella, staph arthritis and cannibalism.

In Alberta, broilers are facing bacterial infections, low levels of leg abnormalities from reovirus and low levels of IBH. Broiler breeder flocks are facing bacterial infections, egg peritonitis, cecal coccidiosis at 19 to 26 days and staphylococcus aureus at six to 20 weeks. Layers in Alberta are facing fatty liver hemorrhagic syndrome, red mites, egg peritonitis and Brachyspira from dirty eggs.

Turkey producers are seeing bacterial infections, and turkey poult producers, brooder pneu -

monia from aspergillosis. “Gangrenous dermatitis at about 47 days seems to be an up-and-coming turkey disease,” Ambrose adds.

“There were five or six cases in November in Alberta, and it can all be controlled with good barn management. It also responds well to antibiotic treatment.

“There is no preventative or treatment medication for histomoniasis (Blackhead), however,” he continues. Producers know how devastating that disease can be, he says, noting that while feed ingredients for general health support (such as yeast-based or essential oil products) can be given, they may or may not make a difference.

“There is a treatment available in Europe that is not registered in Canada,” he adds, “but there is a group of veterinarians actively lobbying Health Canada and CFIA to approve its use here.” He observes there isn’t much willingness to discuss Blackhead management at the regulatory level.

Broiler producers are seeing bacterial infections and IBH, with bacterial enterococcus on the rise. Layers are facing cecal coccidiosis and cannibalism. Turkey producers are seeing high early mortality at startup, and broiler breeder producers are seeing staph arthritis, rare ionophore toxicity, sudden death syndrome and calcium tetany. Calcium tentany is easily prevented, Ambrose notes. He recommends large particle limestone, which stays in the gut longer, and oyster shell in the afternoons.

Broiler producers in Manitoba are seeing IBH. What’s more, in RWA production Ambrose says there have been outbreaks of coccidiosis/ necrotic enteritis (NE) in non-medicated flocks. Bacterial infections from E. coli, leg issues from reovirus and bacterial enterococcus are also present. Layer flocks are dealing with egg peritonitis/polyserositis, cannibalism as well as coccidiosis/enteritis.

Broiler breeder producers are seeing fowl cholera, male management issues and Salmonella (S. enteritidis). “We’re all on guard for Salmonella,” reports Ambrose. “Manitoba has been clean for this historically, it’s literally had zero isolations, and this year there was at least one case. It’s a little alarming. It is most likely a biosecurity breach

from mice or darkling beetles being the vector, although producers in Manitoba have done a fantastic job of rodent control historically. A vaccination program is now in place.”

Turkeys in Manitoba are currently facing bacterial infections, coccidiosis/enteritis, bone issues from tibial dyschondroplasia/rickets and hemorrhagic enteritis. Ambrose adds that turkey breeder flocks are in very good health.

In broilers, McKinley Hatchery’s Petrik reports that IBH has been increasing in incidence, and the impacts can be minor or more severe (up to two per cent mortality).

“Reovirus is a real problem, especially in the breeders,” he notes. “Some chicks were euthanized to deal with a particular situation.”

The following are key takeaways from Ambrose and Petrik’s disease updates.

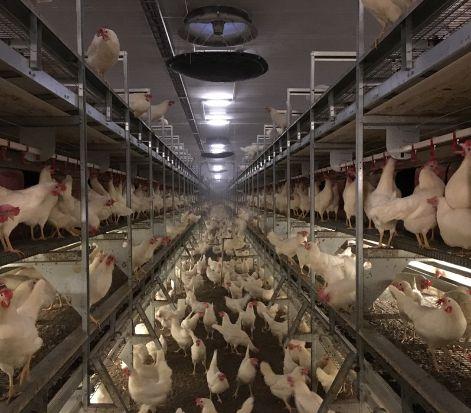

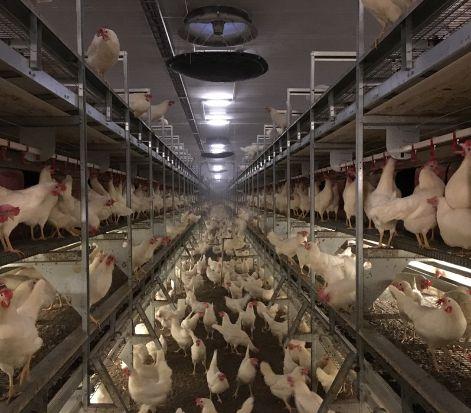

Housing changes

Layers now in free-run and aviary housing have access to their manure, so cocci, NE and E. coli infections are very important to try and prevent.

Holistic approach needed

All chicken farmers need to remember that therapy or vaccination alone is of little value unless they are accompanied with improvements in all aspects of management and biosecurity.

Food safety challenges

Cocci and NE are fairly stable, but Petrik notes that control programs are changing as broilers under RWA production are more susceptible.

Some bronchitis was apparent in Ontario broiler flocks this year as well. In layers, some ILT appeared in the last year, which was a bit surprising to Petrik and others, and he believes the cases were primarily due to issues around proper vaccinations.

Some broiler producers experienced bronchitis and Petrik says vaccination is effective to some extent. There was also some IBH, including one case with almost 15 per cent mortality. In Quebec’s layers, there were a few cases of false layer syndrome (see sidebar). Some major ILT infection was also apparent, 10 cases, and quarantine efforts were

Broiler farmers should be aware of the potential challenges that campylobacter and salmonella broiler infections play in food safety and be ready to play a role in their control.

Collaboration critical

Co-operative efforts are critical in dealing with disease issues. This was well demonstrated in 2017 with false layer syndrome.

put in place to stop the spread. “The industry also reached out to backyard flock owners in the risk zone and offered free vaccinations,” Petrik reports. Turkey producers had a couple of Blackhead issues.

Some broiler breeder flocks had reovirus. Some layer flocks had NE and some broiler flocks had NE, notes Petrik, as well as some bronchitis and wooden breast.

With layers moving out of conventional housing, the disease landscape is changing for them, Petrik explains. Free-run and aviary housing conditions allow birds to have access to their manure, so cocci, NE and E. coli infections are very important to try and prevent. Overall, both vets agree that Canada’s poultry industry is dealing with a lot of regulatory issues. “We’ll deal with it, but growers need to remember that therapy or vaccination alone is of little value unless they are accompanied with improvements in all aspects of management and biosecurity,” Ambrose says.

Petrik reports that before 2016, false layer syndrome had only been seen in Europe and China. But that year, there was an outbreak in Eastern Canada – about 22 flocks in Quebec and Ontario were affected. With industry action, however, there were only three cases in the last year (mostly in Quebec), with less severity as well (40 or 30 per cent of a flock had been affected previously and last year, it was only about six per cent).

It was a tough situation to deal with, as it’s not a condition that’s noticed until birds are ready to lay (19 weeks of age). Autopsies and other signs were used for diagnosis.

It appears that the strain in Quebec and Ontario is the same. “When we sequence a virus, we only sequence about eight per cent, but analysis of that eight per cent indicates that the viruses are more than 97 per cent identical,” Petrik explains. “No one is sure how it was spread, but layer pullets move back and forth over the Quebec/Ontario border, as do live broiler chicks.”

The great improvement in incidence and severity of the disease is due, says Petrik, to a highly-collaborative industry response. “The amount of communication and co-operation was really high,” he reports. “From our first inkling of what we had to having a response program in place was about a month. That’s pretty incredible. Everyone worked together on increased biosecurity and more.”

Madeleine Baerg

Just two years ago, blockchain was a relatively unknown concept. Today, however, it is being called the biggest technological innovation of the decade and most influential corporate game-changer across industries. The speed at which it has burst onto the business world leaves many – poultry producers included –wondering what on earth it is and why it suddenly matters so much.

A blockchain is a secure database that automatically and in real time captures fully transparent, encrypted (non-alterable) blocks of data from links in a value chain, and then freely shares that information with all parties in that chain. This data sharing allows increased product security and traceability, maximized efficiency and a resulting reduction in costs, the elimination of human error, and –when the information is provided through to the final link in the value chain – improved consumer confidence.

Blockchain depends on three prerequisites. First, all participating links in the blockchain must be open to complete transparency. Second, because it is a digital technology that depends on data, the processes within each participating company must be digitalized and standardized – every input and output must be recorded according to measurements understood by every other part of the blockchain. Finally, there must be broad participation of stakeholders along the value chain.

What does blockchain look like in real life application? The automotive industry is already using it for the delivery of parts and resources. In the event of a product shortage or defect, blockchain immediately notifies every value chain participant, pinpoints the exact origin of the fault and automatically selects an alternative source for the product to prevent a slowdown or a recall.

At this point, blockchain is only being

piloted or used in limited scale in the poultry industry. However, when fully implemented, a poultry blockchain could track individual birds from egg to dinner plate. This tracking could include every input and output from each link in the supply chain, from breeder, hatchery, producer, slaughter house, processor and retailer, to feed-mill, veterinarians, transporters, certification bodies, etc.

Bird health and growth rate, food and water consumption, origin and transport details, production results and more could all be transparent to the entire value chain. Ordering and payments between suppliers could be automatic and immediate. Even the exact arrival time of the trucks coming to pick up the fully-grown birds could be optimized to precisely maximize efficiency.

While the benefits of blockchain are obvious and significant, not everyone is keen

“Blockchain isn’t coming. It’s already here.”

to jump onboard with new technology. There may be little choice but to comply.

According to a Rabobank report from last December, “Companies that want to remain successful in the future food value chain should start to explore options for participating in blockchain initiatives…” Already, Dole, Kroger, McCormick and Company, Nestle, Tyson Foods, Unilever and many others are working towards implementing blockchain-enabled food tracking systems.

Last June, Walmart announced it intended to be fully blockchain compliant by 2022. Then, in September, it pushed an even tighter timeline for certain suppliers, announcing its leafy green suppliers would be required to participate in blockchain for full traceability within one year.

Blockchain is coming, whether producers choose to push it from within industry or wait to have it forced upon them from above.

Hendrix Genetics Innovations is among the first companies in the world to pilot the use of blockchain in the animal protein value chain. In 2017, the company and several of its value chain links conducted a proof of concept project to investigate the potential and limitations of blockchain as it relates to the animal protein.

Specifically, the project trialled replacing the existing Letter of Credit system with a blockchain based system surrounding deliveries and payments of eggs. In 2018, Hendrix Genetics Innovations began two more pilot projects, one relating to eggs and the other to animal welfare standards in turkeys in the Netherlands.

“For us, blockchain is an interesting technology as it has the potential to make supply chains safer, more efficient and more sustainable,” says Thijs Hendrix, portfolio manager of innovation projects at Hendrix Genetics Innovations.

“It can make the supply chain operate more efficient[ly] by sharing the relevant information. Blockchain also allows secure sharing of real-time data. This has benefits for all parties involved. Consumers will benefit from more transparency and improved food safety.”

“Blockchain technology surely has the potential to impact our value chains in the coming years. The technology is still in development and many applications are being developed. The pace of adoption will also depend on the success of these applications,” Hendrix says.

In 2014, Cargill derivative Honeysuckle White conducted a U.S.

Blockchain depends on high-quality, fully-automated, encrypted data. Multiple companies are jumping into the data capture ring, offering a wide variety of technologies capable of measuring and recording an endless spectrum of data points. Toronto-based Intellia has created the Compass System, specifically designed to measure poultry health and gain for the purpose of blockchain transparency.

“We’re beta collectors for blockchain,” explains Robert Lynn, an independent representative with Intellia. “Where we add additional value is that we also have an artificial intelligence (AI) component that analyzes the data so that what we hand over to the blockchain is already massaged or processed for results.”

Intellia offers broiler barn sensors including bin scales, water meters, gas (ammonia and C02) sensors, humidity sensors, etc. – measurements of virtually anything that could affect the growth of the birds. The data is pulled into Intellia’s central database along with bird weights measured in real time (typically every 15 minutes) by scales built into hanging perches. Based on all of this data, an AI algorithm churns out a constantly adjusting prediction of the exact date and time the birds will get to their target weight.

The system offers real-time visibility and learns through use, Lynn explains. Since every barn offers a different environment, light regimen, water pH, etc., every barn’s growth curve is slightly different. The Intellia algorithm compares the historic growth curves of previous flocks raised in that individual barn to the current flock to improve accuracy of growth predictions and to issue warnings when any sensor records an unexpectedly high or low result.

“There’s a lot of obvious benefit to the grower. You want to ship the birds at just the right time. If they are overweight, you’re going to pay for unnecessary feed. If they are underweight, they might not meet the cutter’s settings,” Lynn says. “Even if you can save a penny per bird on feed or efficiency, that can be millions of dollars in savings. Depending on your volume, the savings can keep going up and up.”

Lynn says that processors in the U.S. are “all over” this form of data capture because they own the birds during production. In Canada, producers are slower to jump aboard because they are smaller scale and more likely to be concerned about privacy. Still, once they hear the benefits to their individual bottom line, their interest spikes, Lynn says.

He has one other absolutely key message he reiterates to producers: “As a grower you are supposed to take a water bucket, dump it upside down in the middle of the barn, and sit on it in the middle of your flock. That’s the best way to understand first-hand whether they are well or not. Doing it that way was okay for the volume that growers used to have. Now, with the need to produce more food with less space, these are tools to make it possible while still prioritizing animal health. But nothing is ever going to replace the grower. That’s the first thing I was ever taught. Nothing will replace the grower.”

farming practices are more transparent is a huge win for the company.

In 2017, approximately 60,000 birds raised on four family farms participated in the Honeysuckle White pilot. In 2018, the company grew the program to include approximately 70 farms and 200,000 birds.

Though Honeysuckle White’s traceable birds are currently only available during the Thanksgiving and Christmas holiday seasons, Long says the company is planning to grow the program in the future.

Honeysuckle White’s tracking of product from farm to consumer is a very limited-scope blockchain. In its truest form, a blockchain’s data capture should be automatic and fully transparent rather than controlled by corporate messaging for marketing purposes. As such, a more authentic blockchain would offer a transparent, data-driven overview of each turkey’s production, rather than a sanitized story-based information chain.

The uncertainty surrounding just what qualifies as true blockchain is evidence that the technology is too new to have yet been fully understood and embraced by industry.

While the general consensus is that blockchain’s full implementation is still three to five years away, at least one blockchain expert says that timeline is entirely outdated.

John Greaves, the blockchain solutions architect for Lowry Solutions and recently appointed chair of the AIM Blockchain Council, points out that 18 months ago, just two companies had invested in blockchain. Now, he says, there are 2,000.

By 2020, he anticipates 20,000. Meanwhile, the International Organization for Standardization has already created an ISO standards group for blockchain: An unheard-of speed for a new technology.

“Blockchain isn’t coming,” he says. “It’s already here.”

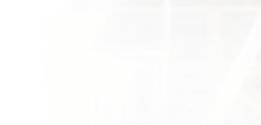

How the red-hot meal kit market is impacting poultry producers.

By Treena Hein

It’s hard for some to believe that the meal kit sector is booming. It’s strange to think that people would buy a kit with all the ingredients for a meal (or have it delivered) and cook it when they could just buy the ingredients themselves for a substantially lower price.

But today’s consumers are busier than ever – and let’s remember that a wide range of convenience foods has already been available for decades, from frozen pizza and boxed mac-and-cheese to taco kits and ready-to-BBQ skewers.

Meal kits are similar or cost less than restaurant meals, and they are also healthy, fresh and come with proportioned servings. And they allow Mom and Dad to cook with each other and the kids, creating some quality time with family, or even allow older kids to make a meal themselves (step-by-step instructions are provided), getting their cooking skills off the ground.

In terms of packaging and food safety, meal kits are a unique challenge, with various options containing just about everything from fresh meat, pasta and vegetables to sauces and herbs. Because ingredients must be protected against both cold and heat, the packaging needs to be well insulated. Meal kit companies are now exploring recyclable or compostable container options to replace Styrofoam, to both reduce environmental impact and please their customer base.

Meal kits are also flexible. Not only can consumers get them delivered several nights a week, they can also pick them up at the grocery store. Indeed, various meal

kit firms are selling their products in stores, while some grocers are acquiring meal kit companies and still others are creating meal kit lines of their own (see sidebar).

Partly because of meal kit demand, Hayter’s Turkey Products in Dashwood, Ont., bought a processing machine in 2017 just for supplying meal kit firms and other food service customers. The machine al-

lows for exact consistency in turkey breast meat portions.

Hayter’s sales and operations manager Sean Maguire notes that their meal kit customers use a lot of ethnic recipes, which helps consumers see the flexibility of turkey. Indeed, in October 2018, Canadian meal kit firm Chefs Plate (now owned by HelloFresh) announced a partnership with Turkey Farmers of Canada (TFC) to use only Canadian turkey year-round.

For example, some menu options include spiced turkey with roasted red pepper fajitas and turkey penne with rosé sauce on the menu.

“Chefs Plate delivers hundreds of thousands of meal kits across the country, so this partnership has a measurable impact on our industry,” states Janice Height, TFC director of corporate services, in a press release.

Echoing Maguire, Height adds that, “The partnership also represents an exciting new frontier for us to educate new consumers about the quality and integrity of our delicious product on a mass scale that goes well beyond the traditional grocery aisle.”

In the U.S., HelloFresh offered two box kit options this past November to feed Thanksgiving crowds, one which included enough roast turkey to feed up to 10 people. While the company’s Canadian brand didn’t offer the same box kits, it did offer some Thanksgiving-related turkey meal kit choices.

For its part, Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) is hoping to explore consumer interest in meal kits in early 2019 within its Usage and Attitudes Study. “My understanding is that it’s a $120 million-plus industry in Canada and it’s going to grow more and more,” says CFC communications manager Lisa Bishop-Spencer, citing 2017 research from consulting firm The NPD Group.

“We have been approached by a few

companies offering this service to Canadians, we can’t divulge which, and we are working with them to deliver the Raised by a Canadian Farmer logo to help consumers understand that the chicken in their dishes is local and raised to a set of national standards.”

Meal kits also make consumers feel as though they’re playing a bigger role in their food choices, Bishop-Spencer adds. “That’s important,” the communications rep says. “It’s also important for these companies to deliver on their consumers’ expectations for Canadian goods – which is where the Raised by a Canadian Farmer logo comes in.”

From a processor’s perspective, it’s not easy to provide details on the meal kit market, as the demands of these firms are not easily apparent to most primary and further processors, notes Robin Horel, president of the Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council (CPEPC).

“Frozen meals are often manufactured for retail sale by our further processing member companies, while fresh meat kits are made with separate ingredients purchased by the meal kit provider,” Horel explains.

“As processors, we often do not know if the purchased poultry part is going into a meal kit…We suspect some small meal kit makers may be buying their poultry and meat ingredients from supermarkets or retail stores.”

However, while CPEPC can report that

meal

When major food firms get into the meal kit game, you know there’s more growth ahead. Here are some of the latest North American developments:

• Amazon now sells meal kits on its platform.

• In Canada, the Metro grocery chain now has a majority interest in Montreal-based meal kit company MissFresh and is selling its kits in Ontario and Quebec stores.

• MissFresh online customers now have the option of picking up their orders in a Metro store, and receive a small discount on their total grocery store bill for doing so.

• Blue Apron, HelloFresh and Plated are all moving to make their meal kits available in grocery stores.

• Walmart is already rolling out its own meal kits in thousand of stores this year.

• Longo’s has already done so – its new Impress gourmet meal kits come in eight options.

• In late November, HelloFresh Canada (following its recent acquisition of Chefs Plate) announced that it expects to own 60 per cent of the Canadian meal kit market share in 2019. It delivers in every province.

• HelloFresh delivered 46.5 million meals to 1.84 million customers worldwide between July 1, 2018 and September 30, 2018.

• HelloFresh Canada will be instituting “a significant price drop” for its Chefs Plate meal kits, “which will make our kits more accessible for Canadians. Prices will start as low as $8.99 per serving as of early December 2018.”

consumer demand for meal kits appears to be growing, Horel notes that consumers who buy meal kits on a regular basis are likely visiting the supermarket less often. “Therefore, we are not sure we can count on this niche to increase chicken and turkey demand,” he says.

“To the extent that major retailers are getting into this segment, any growth would be reflected in their purchases and again, would not show up as a special request since they already buy portioned

breast meat.

As some retailers or retail concepts such as Amazon are successful, market shares for chicken and turkey sales can fluctuate, but overall chicken and turkey demand may not change much.”

The other factor in trying to piece out the impact of meal kits, Horel says, is the constant battle between food retail and food service.

Ziggity makes upgrading your watering system fast, easy and affordable with its lineup of drinkers and saddle adapter products, designed to easily replace the nipples of most watering system brands with our own advanced technology drinkers. So if your watering system nipples show signs of wear, leaking and poor performance, just upgrade to Ziggity drinkers to start enjoying improved results! See how easy it is and request a quote at www.ziggity.com/upgrade.

“Are meal kits drawing customers from the restaurant sector or only those that normally cook at home anyway?” he asks.

“Too soon to tell, but no doubt the fresh meal kits delivered at home will find a permanent place in the food market and perhaps replace some of the frozen dinners stored in the freezer.”

Horel also makes the point, however, that meal kits may not be as common if the economy takes a downturn.

All poultry and eggs in HelloFresh Canada and Chef’s Plate recipes are fresh and produced in Canada, notes the firm’s public relations specialist Jonathan Motha-Pollock. Currently, three out of the 12 HelloFresh weekly menu options feature poultry. Chef’s Plate offers at least one poultry option in each of its classic, family and 15-minute meal plans every week; eggs are also often included in its vegetarian plan.

While the company can’t get into specifics in terms of the demand for meal kits with poultry compared to other options, Motha-Pollock says he “can share that our customers love our chicken and turkey offerings.

For example, right now, Canada’s top-rated meal is our baked parmesan chicken.” He also notes that the cost of a HelloFresh or Chef’s Plate meal kit containing meat protein remains the same regardless of protein type.

“We expect to add more poultry meals as we expand choice for Canadians,” Motha-Pollock says. “Chicken is a staple protein for Canadians, and we’re always striving to provide our customers what they love.”

By Ashley Bruner

If you relied on Canadian media and politicians alone, you might think topics like the economy and health care were what Canadians cared about most. You would be wrong. Canadians’ top priority is much more fundamental than that – before they can worry about hospital wait times or the cost to heat their homes this winter, they first and foremost need healthy, affordable food to eat and feed their families.

Canadians have rated the rising cost of food and keeping healthy food affordable as their top priorities three years in a row. These findings from the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity (CCFI) annual public trust research provides valuable information for all food system stakeholders, including poultry farmers, when it comes to engaging on topics that matter most to consumers.

What are you doing that helps contribute to healthy,

affordable food for Canadians? Are you communicating your efforts with that lens on?

Food matters to Canadians, but how does the average Canadian perceive their country’s food system? This year, we saw a significant decrease on some key measures when it comes to public trust in the food system.

Only a third (36 per cent) of Canadians think the food system is headed in the right direction compared to four in 10 last year (43 per cent).

Along with this decrease, the proportion who feel the food system is on the wrong track increased a significant nine points and is back to 2016 levels (23 per cent).

The overall impression of agriculture in Canada also decreased for the first time in 12 years – falling from 61 per cent in 2016 to 56 per cent in our latest survey. This follows a steady increase since 2006. The decline in positive impressions is driven by a signifi-

This research demonstrates that the food system can’t take trust for granted – it must be earned.

cant increase in Canadians who say they don’t know enough to have an opinion (12 per cent up from two per cent in 2016).

While several years of data is required to indicate a truly negative trend, the erosion of perceptions should serve as a rally cry to food system leaders and a reminder of the CCFI mandate: “Helping the food system earn trust.” Trust and public goodwill cannot be taken for granted and can erode without long-term engagement and effort.

One way to better earn public trust is through transparency. In 2017, CCFI research focused on transparency and what it takes to achieve it to increase trust. In 2018, we asked Canadians how well different segments are doing

in providing open and transparent information about how their food is grown or produced so they can make informed food choices.

Unfortunately, ratings across all groups are low, with farmers getting the highest rating at only 34 per cent getting an 80 per cent or higher. Like many topics, numerous Canadians are unsure with 58 to 65 per cent being neutral.

This report card clearly shows that while there are many great efforts underway to be transparent and share the story of our food in Canada, the collective impact is not being perceived as enough or reaching consumers yet.

Food industries need to take targeted efforts to specific audiences to increase share of voice using new approaches to help improve this transparency report card in the future.

This research demonstrates that the food system can’t take trust for granted – it must be earned. Canadians desire balanced, credible information about food so they can feel confident in their decisions for themselves and their families. It’s up to the entire food chain to turn up the volume and efforts to openly share information about food and how it’s produced, processed and packaged with consumers.

Food loss and waste has significant environmental, economic and social consequences. This waste leads to increased disposal costs, produces greenhouse gases throughout the food value chain, and costs the Canadian economy billions of dollars. Despite the large amount of

food waste in Canada, there are still many people who are struggling daily with food insecurity.

This year, CCFI asked Canadians directly how they felt about this issue, where they fit into the problem, and what they thought could help them reduce their household’s food waste.

Like many issues, all the key food system stakeholders are viewed as responsible when it comes to reducing food loss and waste.

What is different than other issues?

The public accepts accountability, with 69 per cent of respondants saying consumers like themselves are responsible for reducing food loss and waste in Canada.

The main causes of household food loss and waste in Canada are throwing out leftovers, having food reach its “best before date”, and buying too much food. Seven in 10 Canadians say they are looking for tips to reduce food waste and CCFI answered that call.

Check out bestfoodfacts.org to read recent articles about reducing household food waste. Use this yourself or share with others while illustrating that reducing food waste will help save money in the long run. This ties back to what is most important to Canadians –the cost of food.

The 2018 Public Trust Research is a unique combination of building on trend and benchmark data. It’s a responding to emerging food system issues and using innovative methodologies to find new insights that inform efforts to earn trust more effectively. The 2018 web-based survey was completed from July 13-19, 2018 by 1,509 respondents who reflect the general Canadian consumer population aged 18 or older.

Download the CCFI Public Trust Research reports and listen to webinars about this research, transparency, millennials and more at foodintegrity.ca.

By Dr. Kayla Price

Dr. Kayla Price is poultry technical manager for Alltech Canada and is an expert in poultry intestinal health.

Global poultry production has entered an era of increased oversight of antibiotic use during live production. Being able to treat sick animals with antibiotics is important. As an industry, we must continue to do our part to maintain antibiotic effectiveness so they can be used as tools for sick animals. As with any change, there will be a learning curve moving forward. The focus has shifted toward management re-evaluation and intestinal (gut) health. Gut health has recently become a hot topic, yet there is still debate about what it means and how it relates to overall health and wellness.

One of the commonalities across commercial poultry is the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). Along with the skin, the GIT is one of the few areas of the body that constantly has access to the outside world. Simplistically, the monogastric GIT is just a tube that links the front end to the back end of an animal. The lumen of the GIT is the inside of this tube, where outside food and other particles can pass through.

As a result, the GIT has more functions than just digestion and absorbing nutrients that can be “translated” to meat or eggs. Due to this constant outside access, the complex GIT also must act as a barrier. This barrier allows nutrients to pass through while preventing damaging

molecules or organisms from leaking into the body.

The barrier can be separated into simple sections: 1) A physical barrier that contains cells, tight junctions and mucus; 2) An immune barrier that contains immune cells and byproducts; 3) The enteric nervous system barrier, which contains signaling molecules that connect the brain to the gut; and 4) The microbiota barrier that contains an array of microbes that can be “good”, opportunistic (i.e., “bad” under certain conditions) and “bad”.

Another way of thinking of this is as a fortress protecting the GIT, keeping bad forces from getting in but allowing good or tolerated forces to pass through. The fortress contains guards in the front (immune

byproducts), a surrounding swampy moat (mucus, microbiota and immune byproducts), a stone wall (cells) and mortar (tight junctions), messengers to the inside guard (enteric nervous system) and the fortified inside guard (immune cells and byproducts).

Based on the World Health Organization’s definition, health is more than just the absence of disease or weakness – it is a state of complete mental, social and physical well-being. In the context of the GIT, it has been suggested that health means a state of physical and mental well-being with an absence of gastrointestinal complaints. With animals, this definition may need to be modified to a state of physical and stress-free

well-being in the absence of gastrointestinal distress. Because the GIT acts as one of the many protectors of the body, maintaining this barrier and preventing leakage is essential for the overall health and well-being of the animal. This requires a balance between all sections and functions of the GIT. In a healthy state, these sections act positively in union. But if one or more sections are off-balance, then some or all parts may be unable to work together or may create a negative cycle.

All of this is happening inside the body, but when looking at the animal, you can only see the physical manifestations of the issues with regard to performance, mortality, behaviour, manure, feed and water consumption.

Many researchers consider the microbiota barrier within the GIT to be its own organ because of its complexity. Although the microbiota barrier can consist of many kinds of microorganisms, bacteria are often the focus because of their sheer numbers. Within the gut, there are more bacterial cells than animal cells; in humans, bacteria cells outnumber animal cells 10 times. The microbiota barrier is dynamic and can interact with itself as well as with immune and enteric nervous system barriers.

“That gut feeling” is more than just an expression. There are nervous system signal molecules that increase or decrease within the body during times of stress. In a poultry barn, stress can be anything

from disease to environmental changes. Some of these stress-triggered nervous system signals can act on the general immune status of the animal – the animal’s ability to protect its health – as well as within the GIT. Due to the complexity of the GIT, these signals can act not only on the immune and physical barriers but also on the bacteria.

Some bacteria can recognize these signals and react to them, but because there are many bacterial communities in the GIT, there can be a variety of reactions to these stress signals, such as increased bacterial population, biofilm formation and increased bacterial virulence. A simple change in stress levels, whether short or long-term, can impact the bacterial communities in the microbiota and, therefore, the bird.

The immune system is found throughout the bird, but a large portion of the immune system is part of the GIT barrier. Within the GIT, the immune barrier must determine what should be tolerated (e.g., nutrients, commensal bacteria) and what should be acted against (e.g., pathogens). How the immune barrier reacts can change depending on the stressor and the challenge load. When facing a major stress or challenge (e.g., disease), the immune barrier generally focuses on attacking that issue. If other stressors appear while the body is fighting the primary stressor, the immune barrier may have a difficult time protecting against that additional stress.

Although the immune barrier can multi-task to manage several small stressors, there is a threshold. Many stressors (e.g., wet environment, mycotoxins, water quality issues) attacking the bird simultaneously can result in immune suppression. In this state, the immune barrier does not work as well and is less able to fight against other challenges.

One of the first actions the immune barrier takes in reaction to stress or challenges is to start the inflammatory process. Inflammation can be a bit of a double-edged sword in the body; it can help a bird fight off challenges, but too much inflammation – especially over a long period of time (i.e., chronic inflammation) – can cause problems in the GIT.

When a bird is continually exposed to small challenges, the constant inflammatory reaction can break down the protective barriers of the gut, causing an interruption to normal GIT function. When opportunistic pathogenic bacteria flourish and the GIT is no longer a healthy environment, disease or changes in performance and production may manifest.

The microbiota within the GIT of a bird is dynamic, and a balanced GIT microbiota consists of a total population of diverse bacterial communities. Population numbers, communities and diversity can change depending on many factors, including the animal species, the location within the GIT, the age of the animal, parental microbiota and environmental impact (e.g., feed, water, housing, handling).

Bacteria, both individually and as part of a community, can release signal molecules and metabolites (byproducts of metabolism) that are able to “talk” with each other or have a function to act within or on the GIT. It’s becoming clear that not only the bacteria within the GIT but also how they interact with each

By Lilian Schaer

When it comes to animal welfare, Alexandra Harlander prefers to get her information straight from the horse’s mouth. Or, in this case, directly from the poultry she’s studying.

As a veterinarian and assistant professor in the University of Guelph’s Department of Animal Biosciences, she focuses on poultry behaviour and welfare, applying bird health and preference tests to current management practices to enhance poultry well-being and health.

“I always want to ask the animal what is good for them, that is my approach,” she explains, adding that when it comes to manure (feces and urine), for example, the birds are pretty specific.

Ammonia is one a big air quality challenge in poultry barns. Harlander teamed up with Bill van Heyst of Guelph’s School of Engineering on a project to determine the impact on laying hen behaviour of fresh air versus air contaminated with ammonia.

In fresh air environments, birds spent more time foraging and started foraging faster, and were more likely to spend a longer time foraging in air with naturally occurring ammonia instead of introduced synthetic ammonia.

This can have implications for recommendations on things like barn ventilation, manure management and litter quality in the national codes of practice for the care and handling of poultry, but will also impact how future behavioural research involving poultry and ammonia effects are conducted.

“Birds behave differently under different conditions and they can differentiate between natural and synthetic ammonia,” Harlander says. “Providing fresh litter substrate is very important.”

Enriched cages for laying hens provide scratch pads on the mesh floors for natural hen behaviours like foraging and dust bathing. When no litter material is provided, though, manure can accumulate on the pads.

Another of Harlander’s behavioural projects showed that while the birds prefer to rest in clean areas, they like to forage and will do so in soiled litter or on dirty scratch pads if they have no other forage material available.

“Other animals tend to avoid soil areas, but birds will not avoid poop on their scratch pads if that’s the only thing they have to forage in,” she says.

Another interesting angle to the manure story, according to Harlander, is that laying hens will also eat manure from other birds, especially if they’re forced to forage in dirty litter.

Although they had a clear preference for clean feed, hens in another Harlander study consumed an average of 61.3 grams per day of feed containing feces and urine. What’s not known yet is how this manure consumption affects birds’ gut and overall health and work is now underway to investigate this in more detail, including how this could be linked to abnormal behaviours and feather pecking.

For egg farmers, Harlander’s research provides some clear recommendations:

• Birds prefer fresh air: Clean litter substrate and good ventilation will keep barn air quality high.

• Laying hens like to forage: Providing small amounts of clean forage materials prevents foraging in dirty litter or on soiled scratch pads

• Hens will ingest manure: Keeping feed clean lessens the chance they’ll eat manure, the health and behavioural impacts of which are not yet known.

These three studies all received funding through the AgriInnovation program of Growing Forward 2.

This article is provided by Livestock Research Innovation Corporation as part of LRIC’s ongoing efforts to report on Canadian livestock research developments and outcomes.

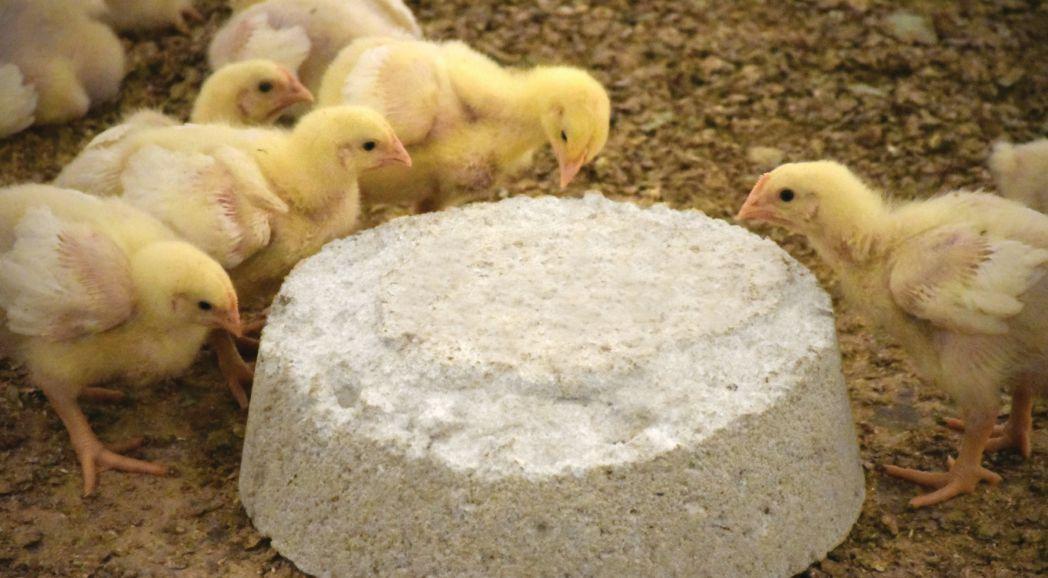

Background

The PeckStone has been sold in many countries around the world since 2013. “We are in talks with most of the main producers in Canada who are currently working with the PeckStones to adopt them as part of their enrichment programs,” reports Dr. Faraz Ansari, from the manufacturer ViloMix in Germany.

The PeckStone is a behavioural enrichment that promotes the search for food, consumption of feed and mobility. Beaks are also worn off, which can reduce pecking injuries. The PeckStone can be left in a food bowl, placed directly on the floor or on top of an upturned bowl. It can also be hung, which the manufacturer says is especially good for turkey husbandry. The product can be kept at activity height as the birds grow taller, raised once or twice throughout the growing period. Various degrees of hardness are being registered in Canada.

The shape of the PeckStone is designed to be well-accepted by birds. The mineral composition (95 per cent minerals) allows for added intake of calcium, magnesium, sodium and trace elements, supporting bone structure, better plumage and general health. Dr. Stephanie Torrey at the University of Guelph is studying enrichments for broilers, including this product. Read more on that at canadianpoultrymag.com.