FOOD BEVERAGE

Bringing together Canada’s energy efficiency experts to grow momentum for your business. Energy management is crucial to maximize profitability and combat climate change. This two day conference offers customer connections that will give you the power to save. Learn about realistic, turnkey solutions to help your organization thrive in today’s competitive environment.

SALES MANAGER

Jay Armstrong jarmstrong@ mromagazine.com (416) 510-6803

VICE-PRESIDENT

Tim Dimopoulos tdimopoulos@ canadianmanufacturing.com

COO

Ted Markle tmarkle@annexbusinessmedia.com

PRESIDENT & CEO Mike Fredericks

Rehana Begg

rbegg@annexbusinessmedia.com (416) 510-6851 ART DIRECTOR

Mark Ryan

ACCOUNT CO-ORDINATOR

Barb Vowles bvowles@annexbusinessmedia.com (416) 510-5103

CIRCULATION MANAGER

Beata Olechnowicz colechnowicz@ annexbusinessmedia.com (519) 376-0470 (866) 323-4362

Shawn Casemore • scasemore@emccanada.org

CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, TREASURER AND GENERAL MANAGER

Al Diggings • adiggins@emccanada.org

smcneilsmith@emccanada.org

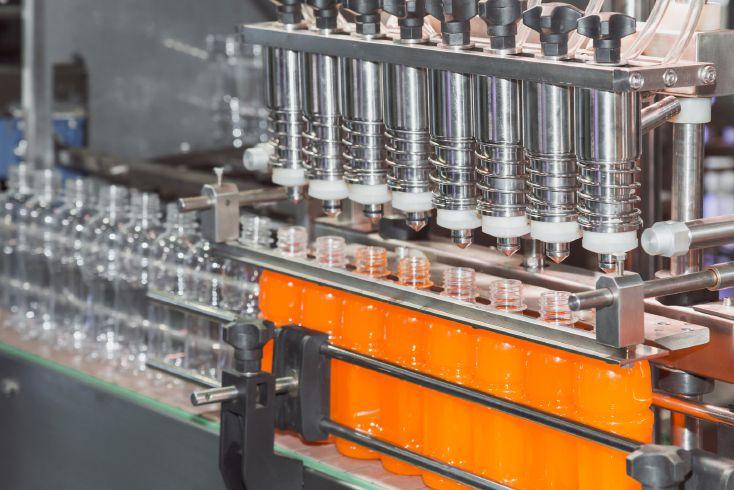

Tasting success

As I watch my nine-year-old niece pipe buttercream between two delicate meringue-based layers that hold together the macarons she’s baking from scratch, I marvel at the dexterity of this budding pastry chef. And I wonder why the classic, glamorous, Instagram-worthy sandwich cookie endures in the imaginations of our high-volume, fast-food, convenience-driven, fickle-foodie, highmaintenance, trend-chasing culture.

Food trivia junkies will have you believe that the French take credit for popularizing the macaron, even though it was first produced in Venetian monasteries around the eighth century. Or, perhaps it was a pair of nuns, affectionately known as Les Soeurs Macarons (The Macaron Sisters), who supported themselves by baking and marketing macarons in Nancy, France. Another popular legend, routinely debunked by food historians, tells us that the macaron made its way to France in the 16th century, after King Henry II married Catherine de Medici, a noblewoman reputed for introducing a long list of foods, techniques and utensils. No one knows for sure.

Focus instead on how the modern macaron has risen as a pastry du jour, and a plausible picture of the macaron unfolds. The art of filling the macaron

with ganache can be credited to the grandson of the founder of the famous Parisian patisserie, Ladurée, Pierre Desfontaines. In 1993 Ladurée was purchased by Francis Holder, chief executive of Holder Group, which has built its billion-dollar bakery business on taking the best of American industrial production, while staying true to the cachet of traditional French pastry-making techniques and artisanal methods.

Holder Group has three Château Blanc manufacturing sites located in Northern France – Marcq-en-Baroeul, La Madeleine and Arras. Marcqen-Baroeul has a logistics platform of 10,000 m2. It is here, at the Château Blanc research and development centre that macaron production kicks into high gear with 13 automated production lines (three are

certified organic) and a cutting-edge viennoiseries production line for yeast-leavened dough.

Château Blanc’s treats can be savoured in more than 45 countries – including 85 Ladurée boutiques and 620 Paul bakeries/cafés under the parent company’s umbrella. In Canada, Ladurée’s luxury brand has only recently landed in Vancouver and Toronto, but there are plans for growth.

As a prodigy baker, my niece has a head start on Francis Holder, who started out as a bakery apprentice at the age of 15, more than 60 years ago. And while she may not be interested in Holder’s story for now, she could benefit from learning how he wrapped his head around the idea that demand is driven by efficient operation. With more than 830-million euros in turnovers (in 2015), 33,000 tons of finished products each year, it’s safe to say he had a sweet idea.

Rehana Begg Editor, Food & Beverage Engineering & Maintenance rbegg@annexbusinessmedia.com www.mromagazine.com

CLEAR THE AIR

The essentials of good compressed air preparation.

BY DAVID GERSOVITZ

Germans take their sausages seriously. Back in 1997, a scandal erupted when trace amounts of mineral oil found a way into a vacuum-wrapped pack of würstchen. The cover of the national newsmagazine Der Spiegel screamed, “Oil in the Sausage!” The story is recalled in articles by Rod Smith, editor of the trade magazine Compressed Air Best Practices , who was working in Germany at the time. The problem was traced to contaminated process air. Oil vapours in the compressed air had been blown into the sausage packaging and condensed, showing up in testing by a consumer advocate. In hindsight, an activated carbon filter in the air preparation system would have absorbed the hydrocarbons. Much has changed in the two decades since. Food safety laws, industry standards and government inspections are generally more

stringent, in Canada, Germany and elsewhere. Consumers are more informed and have high expectations for food safety. Producers are careful about protecting their reputation and brands; bad headlines can’t be whitewashed from the digital ether. New compressed air systems, when well-maintained, are highly efficient and reliable. Today’s oil-free compressors and pre-lubricated drives – the latter pretty much industry standard now – virtually eliminate the possibility of “oil in the sausage.”

Food safety and food air safety are different topics; food processors need approaches for both. Food safety management programs have their own ISO standard (22000), as does compressed air purity (8573-1:2010). However, maintaining good compressed air quality in food preparation is not only a technical issue; persistently poor air preparation will raise energy, labour and spare parts expense in the

Service units for preparing compressed air may consist of different combinations of units.

Tip: Locate service units close to the consuming device to minimize the danger of recontamination.

short run, cause unplanned stoppages and shorten the working life of the system. You might end up with spoiled product, or worse, a recall. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFSA) has an online archive of all recalls back to 2014. So far in 2018, there have been more than 35 new and updated recalls. Safe food production is a perpetual challenge – as is maintaining good compressed air quality.

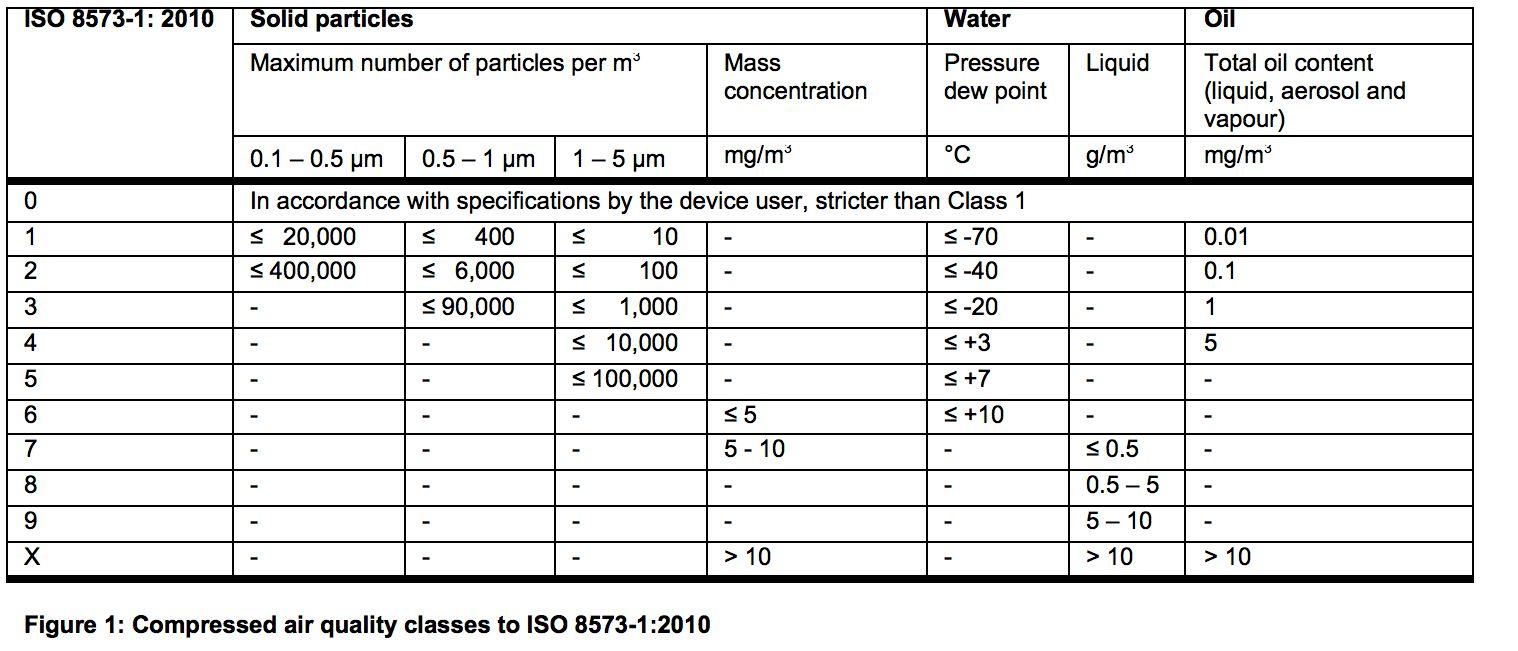

ISO SETS AIR PURITY CLASSES

One cubic metre of untreated compressed air may contain millions of dirt particles, oils, even heavy metals such as lead, cadmium and mercury. Water, in the form of natural atmospheric humidity, is released in large quantity when compressed air cools down. ISO 8573-1:2010 (Figure 1) sets different purity classes for allowable levels of contaminants and humidity

in compressed air in industry. It makes no determination which apply to food. Voluntary guidelines and recommendations by food safety and trade bodies are used.

Different compressed air qualities are required at different points within the production system. A proper plan should take into consideration the special requirements for the production of each type of food. A combination of centralized, basic compressed air preparation and decentralized auxiliary preparation is the most cost-effective approach.

COMPRESSED AIR AS PILOT AIR

Three ISO 8573-1:2010 purity levels are observed in food production, with different types of treatment applied within the compressed air system for each. For pilot air – air channelled exclusively to activate cylinders, valves, grippers, etc., with no contact with foodstuff – the recommended purity class is 7:4:4 (particulates-level 7; water/humidity-level 4; oil- level 4), achievable by locating a central refrigeration dryer

with oil separator and a coarse (40 micron) particle filter right after the compressor.

COMPRESSED AIR AS BLAST AIR OR PROCESS AIR

Significantly higher levels of purity are required for blast or process air when blowing out moulds or transporting products, or in cases of direct contact with foodstuff, such as mixing or moving ingredients.

(With packaging machines, when compressed air comes in contact with materials in which food will be packaged, the packaging material is considered part of the food zone.)

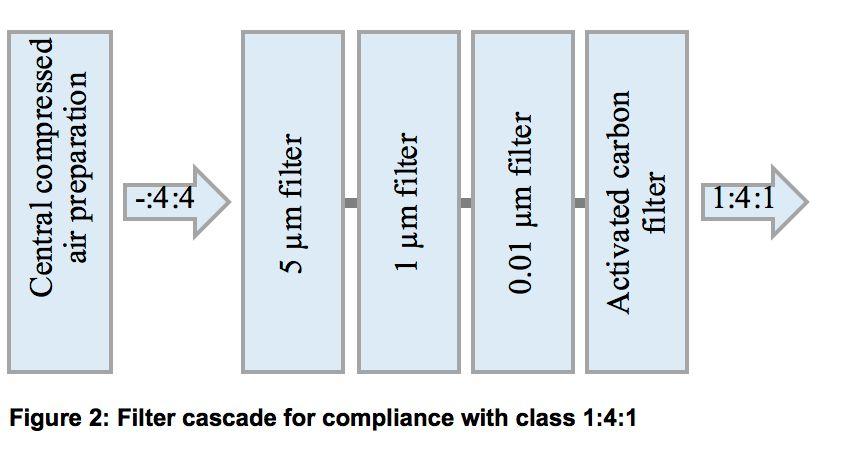

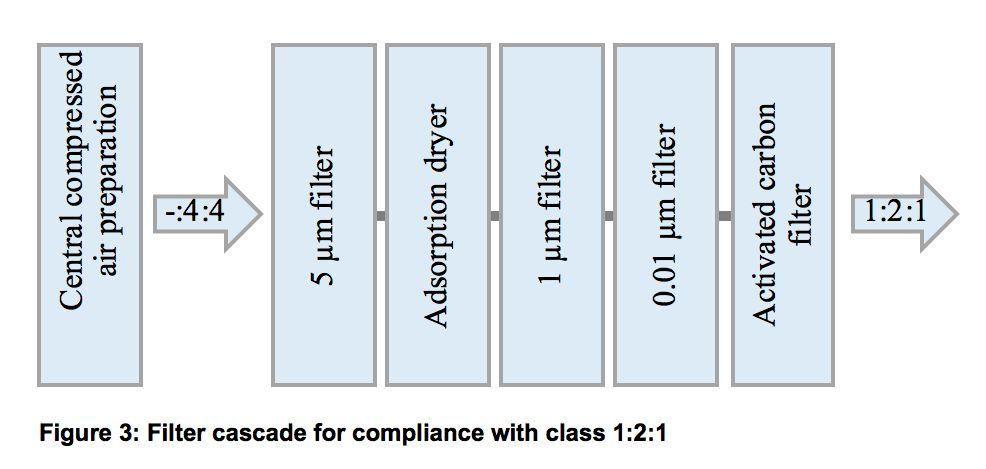

For compressed air that comes into contact with wet food, such as meat, fish or vegetables, it’s widely held that ISO 8573-1:2010 Class 1:4:1 should apply, and for dry foods like cereal or milk powder, Class 1:2:1. That’s what Festo, a leading

compressed air solutions provider, uses. (Some associations like the British Compressed Air Society use ISO 8573-1:2010 purity class 2:4:1 for wet food and 2:1:1 for dry. Classes 2:4:1 and 2:2:1 allow for a greater volume of particulates per m 3. On the other hand, many large food processers implemented in-house standards that exceed what is called for.

The purifying process for food

grade air takes pilot air (already filtered to Class 7.4.4 levels) and flows it through a filter cascade. Festo recommends filter cascades for both wet and dry that consist of a 5 micron,1 micron and 0.01 micron micro-filter – removing progressively finer particulates – and ending with an activated carbon filter to remove trace odours that can affect product quality. For dry foods, an inline adsorption dryer with a .01 micron pre-filter is installed after the 1 micron filter to further reduce the humidity level to comply with Class 1:2:1. If the compressed air system’s volumetric flow is throttled down to 70 per cent, it’s possible to lower the humidity dew point even further, to that of Class 1:1:1. (If sterile packaging is required, the purity class must be met and a sterile filter built into compressed air delivery as close as possible to the consuming device.)

FUNCTIONAL ROLES OF SERVICE UNITS

These particulate filters can be combined in a single service unit.

Service units may also contain components necessary or useful for proper control and monitoring of air distribution, like flow sensors, pressure and vacuum sensors, on-off and soft-start valves and quick exhaust safety valves like Festo’s new MS6SV-E. Another Festo innovation, the MSE6-E2M energy efficiency module, will shut off the air supply to idling machines to avoid energy waste and unnecessary wear and tear, and proactively check the system for leaks. Service units are available in standard pre-assembled

combinations for different applications, or can be user defined. They should be located close to the consuming device to minimize the danger of recontamination of highly purified air in the piping network, for instance with rust particles.

MAINTENANCE IS KEY TO COMPLIANCE

Vendors can help customers determine many system design and operational considerations, like the right air-flow rate and pressure settings. However, the onus is on

the food processor to maintain its system in good order. Good maintenance means being proactive – not just to avoid spoilage or worse, a food recall. Inadequate maintenance leads to higher energy bills as the system works harder, a proliferation of leaks (more energy waste), unscheduled downtime and premature replacement of mechanical components. It can also shorten the life of the compressor.

FOCAL POINTS FOR ON-GOING ATTENTION

Ambient air: Even if you have clean process air, you don’t necessarily have clean air in your process. If the ambient air quality is poor, it presents a danger of direct contamination and will likely require more aggressive filtering to become process air. Think of a bakery that uses process air to open plastic sleeves to slide in bread loaves. Even a minute amount of ambient air could mix in, which is why most large food processors maintain a sterile environment. Ambient air also is the raw

input for compressed air, so the greater the contamination, the harder the entire system has to work. If the ambient air is severely contaminated, it may be necessary to add more filtering capacity to achieve the necessary purity level. It pays to pay attention to air quality in general.

Passive versus active maintenance: Passive maintenance is something many small operators practice and often struggle with. Filters need regular replacing. Clogged filters reduce operational efficiency. An active maintenance approach would include installing sensors that can signal deteriorating performance. For example, a sensor can measure the pressure differential between the input and output around that filter. If the pressure drop exceeds a certain level, the filter needs replacing. The sensor can have a simple visual display – green means good, red means that filter element needs servicing.

Benefits of preventive mainte -

nance: More and more Canadian food processors are embracing preventive maintenance (PM) programs. While arguably more expensive at the front end, a PM program is a good assurance about remaining in compliance with your chosen ISO 8573-1.2010 purity classes. It assures system efficiency and optimizes the service life of equipment. A PM program, cleaning lines and nozzles, replacing filters, etc., should be based on each

operator’s experience with the intervals between passive maintenance interventions. Monitoring devices are the best way to ensure that a potential problem is addressed before it causes the process to fall out of compliance.

Ignorance is not bliss: Many smaller food processors aren’t as wellversed as they could be about what is expected of them in running a compressed air system today. “It’s really their responsibility to find out, but the reality is many are following the

same practices they did years ago,” says Willy Forstner of Festo Canada, whose previous role as the Food & Beverage Segment Manager provided him with a unique insight into this industry. “Typically, upon entering a facility, just from looking around I understood fairly quickly if they were following current food safety standards. In such situations, I would be proactive and discuss food safety topics with them and where to find the information to help them. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) or the U.S. FDA websites are great starting points. There’s an awful lot of good advice online that you can find with a Google search for food safety in Canada. And with all things compressed air, we’re here to help.”

This article was submitted by Festo Canada, a global manufacturer of process control and factory automation solutions. For more information, visit www.festo. com/cms/en-ca_ca/index.htm.

PLASTIC PARTS

Machined plastic components and parts for food-grade applications.

BY GORD SIRRS

Molded, extruded and machined plastic parts and components are often used in food equipment and systems. This includes equipment that process and prepare food, as well as equipment that packages the final product for delivery to customers.

In contrast to molded or extruded parts, machined plastic parts are produced on equipment especially designed to cut, shape and contour plastic materials. Equipment commonly used to produce these parts includes CNC mills, routers, and the like. These advanced technologies allow superior quality and finishing, greater precision and tolerancing, and lower costs since they

eliminate the expensive molds and tooling associated with other production methods.

Users of machined plastic parts for food-grade applications involve two broad groups:

1. Food processors and packagers: Companies involved with the processing, production, or packaging of food products often require aftermarket or replacement plastic parts for their equipment and systems. Custom machined plastic parts are often a good solution for these firms.

2. OEM food equipment manufacturers: Food processing equipment OEM’s often include machined plastic parts in the design and manufacture of their products.

Parts machined from food-grade plastics that are often sought by these user groups include nozzles, covers, wheels, wear parts and components. Machined plastic parts are also often used to replace the metal parts, components and assemblies that were originally supplied on food processing equipment, as well as the conveyors that are used to move ingredients and product within processing facilities.

UPSIDE OF PLASTIC

The term “food-grade plastic” refers to any plastic that comes into contact with consumable foodstuffs and beverages. Food-grade plastics must meet high standards for purity and safety and they are covered by governmental regulations and standards. In Canada, Health Canada oversees regulations governing food-grade plastics, while in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other agencies create the regulations. Food-grade plastics must not contain dyes or additives that are deemed harmful to humans, and they must not leach any harmful contaminants into foodstuffs with which they are in contact. Since many plastic parts used on food processing equipment are within the food zone and may come into direct contact with the product stream, the risk of contamination is significant. In addition, these parts are often subjected to intensive and frequent cleansing.

For these reasons, materials used in the manufacture of food-grade plastic parts should be selected carefully.

While stainless steel and metal components are widely used in food processing equipment, plastic parts offer the following advantages: Resistance to chemicals and

heat. Plastic parts can be machined from materials having low conductivities that can resist high temperatures. In addition, plastic materials are available that are capable of withstanding repetitive cleansing with harsh chemicals in wet/dry environments. Cleansing is often carried out with bactericidal compounds

and steam/water under high temperature and pressure.

Hygiene and safety. To help ensure health safety, food-grade plastic parts can be machined from plastic materials containing antimicrobial additives that help eliminate, kill and prevent the growth of bacteria and fungi, while resisting mildew and discolouration. In addition, parts machined from food-grade plastics will not leach

contaminants into the product stream, nor are they as prone to breakage and wear, as with metal components and parts. In applications where detectability is required, special metal or optically detectable plastics can be used to produce finished parts.

Reduced maintenance costs. Lightweight plastic parts are easier to handle and move during equipment maintenance and cleanings. Parts

Machined plastic parts often replace the metal parts and components that were originally supplied on food processing equipment.

The term “food-grade plastic” refers to any plastic that comes into contact with consumable foodstuffs and beverages.

machined from food-grade plastics are strong and durable and will require less maintenance interventions than those made from metal. Keeping equipment components lubricated is a significant challenge and cost in many food-processing facilities – the low friction properties of plastics mean these parts no longer require lubrication to function effectively. Approved food-grade plastics

that are often used to produce machined plastic parts include engineered plastics such as HDPE, UHMW, Polypropylene, Nylon, Etralyte and others, as well as high-performance plastics such as Kynar and other PVDF’s and Ketron HPV. Approved materials comply with the purity requirements set forth in applicable standards, including Health Canada, FDA, USDA, NSF/ANSI

51, 3-A Dairy, and others that may be applicable within a given jurisdiction.

Choosing machined plastic parts for food-grade applications involves working with a trusted supplier. Reputable suppliers of food-grade machined plastic parts use only approved materials and employ good manufacturing practices that will provide a safe product.

The challenge is always to determine the best plastic for your part and

application – experienced suppliers will have the materials knowledge to recommend the best option for any application and budget.

Gord Sirrs is president of Canada Rubber Group Inc. (CRG), a leading provider of custom fabricated solutions from rubber, plastics, and other materials. For more information, contact Gord at gsirrs@canadarubbergroup.com.

WRENCH TIME

Measuring the value of maintenance can be tricky, unless you’re clear on what’s being measured and what work needs to be done.

BY DOC PALMER

Wrench time explains why a company can get a 50 per cent boost in maintenance productivity! That means a good workforce completing 1,000 work orders each month could become a superior workforce completing 1,500 work orders per month, for free! That’s a big deal! But you don’t have to measure it. You probably should not measure it. But you might want to measure it. Decisions, decisions...

The concept of wrench time shows how a typical workforce can improve its productivity by 50 per cent or more. Wrench time is the percentage of time a person available (not on vacation or in training) typically is engaged in productive activities moving a job forward. Not counted as wrench time are “non-productive”

activities, such as break, travelling to jobs, obtaining parts or other similar instances, even though they are part of doing business. Maintenance forces at good plants usually have an overall wrench time of only 35 per cent. Amazingly, this seemingly low score is typical across companies, industries, countries and even cultures. These groups have the same wrench time because at about 35 per cent productivity, people “feel busy.”

Over the years, workforces around the world staff up (or staff down) in accordance with the growth (or decline) of the backlog of work at a productivity rate that keeps everyone busy and keeps the plant operating at a good capacity. The problem with this philosophy of staffing and backlog management is that it ignores the ability of the plant to move beyond

merely good capacity and merely good productivity. Most plants can achieve superior capacity by completing more proactive work with the same workforce.

Consider a 30-person workforce at 35 per cent wrench time versus 55 per cent wrench time. 55%/35% = 1.57. 30 persons x 1.57 = 47 persons. The 55 per cent workforce completes work at the rate as if it had 47 persons. If the 35 per cent workforce completes 1,000 work orders per month, the 55 per cent workforce would be completing 1,570 work orders per month. The extra 570 work orders per month are free. Planning and scheduling absolutely answers the question: How can we complete more proactive work to head off failures when we have our hands full of reactive work? That’s a big deal! But there are problems with measuring wrench time (other than just the time and effort involved). One problem is that conducting a study has great potential to upset the workforce. Another problem is that measuring wrench time does not improve wrench time. What the plant really wants is to improve its work order completion rate. Why not just accept that wrench time is 35 per cent and start doing

planning and scheduling properly? Plants that correct their planning and scheduling efforts should see their work order completion rates rise, which is what they really wanted anyway. They rose because of the concept of wrench time whether it was measured or not.

There is also another reason not to measure wrench time. Wrench time can be a terrible measure to begin with. A carpenter could show up at the wrong house and hammer slowly all day without taking a break. The carpenter might have 100 per cent wrench time inefficiently doing the wrong job. (But we do not consider wrench time to be the allin-all, one and only perfect KPI. Wrench time only measures available time working. We presume that considerations of proper work selection and working efficiently stay the same at 35 per cent and 55 per cent wrench time.) The problem here is that when management focuses on wrench time, it gives a signal for everyone to look busy (and possibly leads to gaming the system).

Nevertheless, a plant might want to measure its maintenance wrench time. A plant might want to prove that it is a

typical plant at 35 per cent or see whether it has an effective planning and scheduling program. If a plant does measure wrench time, there are improper and proper ways to do it.

Not all methods to measure wrench time are valid. First, productivity and delays self-reported by the personnel are generally not valid. Most such results are in the 70 per cent or higher range. It is

a study in which observers follow specific craftspeople around all day is also generally not valid.

Most of these studies show 50 per cent or higher wrench time. For one thing, the persons selected might not be “typical” craftspersons on “typical” days. For another, persons being followed generally do not act normally.

Third, studies where observers go at statistically set times into a shop

Email Doc Palmer at docpalmer@palmerplanning.com for a copy of an actual wrench time study with its methodology and results, a slide presentation of doing an in-house study yourself, and his current list of useful work and delay categories and definitions.

The best method to measure wrench time is usually with a statistical sampling method where each person in the workforce has an equal chance of being observed over a sufficient period to represent the actual workforce over time.

The concept of wrench time is a big deal. It is the key to understanding the dramatic gain possible in maintenance productivity through proper planning and scheduling. But you do not have to

measure it. Be cautious if you do.

Doc Palmer, PE, MBA, CMRP is the author of McGraw-Hill’s Maintenance Planning and Scheduling Handbook and as managing partner of Richard Palmer and Associates helps companies worldwide with planning and scheduling success. For more information visit www. palmerplanning.com or email Doc at docpalmer@palmerplanning.com.

difficult for craftspersons to recognize that a moment here or there is not actually “work.” Consider, if it is difficult for management to realize that typical wrench time is only 35 per cent, how can one expect mechanics to understand 35 per cent is “okay” and report themselves accurately? Secondly,

area to see what visible persons are doing is also not valid. These results are generally in the 50 per cent or higher range. These studies do not include personnel that are available, but not in the shop area. These unseen persons might have been travelling, in the storeroom, or in some other delay area.

APPRAISAL

Insulation

energy appraisers can help reduce energy costs and GHG emission.

BY STEVE CLAYMAN

It’s brutally competitive out there. The cost-reduction pressures are relentless – labour, suppliers, customers, energy… the list goes on. By now, the bigticket items have been or are being addressed. You’ve been active on increased automation, lighting, power sources and perhaps the building you’re in.

It now may be time to consider the impact on energy costs related to production, where refrigeration, heat, water and steam are necessary. More jurisdictions are mandating annual reporting on benchmarking energy and water use. Along with benchmarking comes greenhouse gas

(GHG) reduction requirements and, likely, an internal corporate policy to show your “green” bona fides.

The Thermal Insulation Association of Canada (TIAC), the national trade association representing the mechanical insulation industry, is a service provider with qualified insulation energy appraisers throughout Canada. TIAC members consist of manufacturers, distributors and specialty contractors, who address condensation control and corrosion prevention, but also help educate on how correctly specified and installed mechanical insulation can reduce energy costs, reduce GHG emissions and address personnel (burn and frostbite) protection.

situations were immediately evident:

A cent or two savings per can of peas or a bottle of beer falls right to the bottom line. When everything is on the table for review, the state of the pipe, duct and equipment insulation in a plant should be front and centre. With this in mind, let’s take a look at a few real-world situations:

CAMPBELL COMPANY OF CANADA

The project involved enhancing the efficiency of the condensate return system in the powerhouse. Two

• Some of the pipes used to transport the high temperature condensate were not insulated.

• The radiated heat from these pipes made it uncomfortable for the personnel working in the area.

An evaluation was undertaken to determine what the next steps were to be, including:

• Determining the heat loss and energy savings resulting from upgraded pipe insulation.

• Recommending the products and application procedure required to optimize the energy savings.

Campbell Company of Canada saved about $65,000.00 per year in natural gas costs as a result of the insulation project.

MAPLE LEAF FOODS INC.

“In 2001 and 2002, Maple Leaf Foods Inc. identified over $10 million in energy saving opportunities. By early 2005, more than $8 million had been saved,” reports the Canadian Industry Program for Energy Conservation (CPIEC), Office of Energy Efficiency, Natural Resources Canada.

Regular monitoring of the insulation on all process mechanical systems was identified as a contributor to these reported savings.

BREWERS ASSOCIATION (U.S.)

The Brewers Association, based in Boulder, CO, published a detailed report on the value of mechanical insulation in beer production. The report developed a basic protocol:

Four Steps for Effective Insulation

Step 1: Create a team to identify missing insulation

Step 2: Prioritize insulation

Step 3: Order and install insulation

Step 4: Install management program

The Brewers Association makes reference to mechanical insulation following the CIPEC Guide with respect to:

• Section 2.4.3 Tools for self-assessment

• Optimizing the insulation of boiler steam lines

• Section 7.5 Insulation

• Housekeeping, no or low cost

• Inspect the condition of process insulation regularly (include it in the afternoon or evening schedule).

• Repair damaged insulation on pipes and vessels with hot or cold media, without delay.

These case studies confirm that addressing mechanical insulation deficiencies pays off in several ways. At TIAC, we understand the meaning of budget constraints. It is costly to hire consultants and contractors, so where do you start?

The food and beverage industry employees people with superb qualifications – energy managers,

professional engineers, and longterm employees who know the plant like the back of their hand, as well as those that are keen to learn more.

It is with them in mind light that we prepared the “TIAC Operations & Maintenance Mechanical Insulation Preventive Maintenance Protocol.” The guideline is available on the TIAC website and is suitable for in-house personnel as they conduct assessments of the insulation on all plant systems. TIAC also provides access to free downloadable calculator tools to determine the effectiveness of the insulation in facilities, cost-benefit scenarios, condensation control, as well as personnel protection.

When plants reach the point where consultants and/or contractors have to be brought in, it will be with the assurance that you rationalized the initial approach.

Steve Clayman is director of Energy Initiatives, Thermal Insulation Association of Canada. For more information, visit www.tiac.ca.

Conferences, tradeshows, summits, forums, plant tours, EMC networking events and webinars

– there are a myriad of occasions for manufacturers to connect with peers, engage in discussion and participate in meaningful experiences throughout the year.

As the first quarter of 2018 unfolds, thousands of industry representatives have already taken advantage of opportunies to learn, and have participated in a variety of sessions, tackling everything from sectoral initiatives, business growth, innovation and product development, to the latest in legislation, human capital, health, safety, energy, sustainability and environmental issues. Regardless of the focus, the objective is undoubtedly the same – attendance is a way to gain knowledge and

broaden perspectives.

Whatever the activity may be, join in with an open mind, engage with your peers, and take the opportunity to review new products, services or concepts. When you return to your facility, pass along those key takeaways in a manner that sheds

new insight, improvement, product possibilities or savings to your company.

Like industry, the EMC (Excellence In Manufacturing Consortium) team also participates in these activities each year. In January, I attended an FBO Workshop highlighting

the opportunities to invite new immigrants into our businesses.

In February, our team exhibited and led a discussion at the EDCO (Economic Developers Council of Ontario) 2018 Conference. The forum connected us with key community partners who are ready and willing to assist you and your business needs.

And, recently, I attended the Ontario Fruit & Vegetables Growers Conference and the Restaurants Canada Show. These events showcased the latest in automation and new product development, along with knowledge-sharing opportunities with industry experts.

With learning always at the forefront this Spring, what follows are three excellent networking and learning options for processors across Canada.

14TH ANNUAL NORTH AMERICAN FOOD SAFETY SUMMIT

EMC is pleased to be a partnering once again at the 14th Annual Strategy Institute North American Food Safety Summit. This premier event brings together all-star speakers focused on the various aspects of food safety – from regulations to best practices. Every year, manufacturers and subject matter experts from across Canada and the U.S. gather to learn from each other. Early on, organizers recognized the value of peer interaction and, to that end, have worked at developing educational platforms, including timed meet-and-greets, an evening reception and long networking breaks. This year’s summit is scheduled for April 17 - 18, and will be held at the

Marriott Toronto Airport. For a complete agenda, which outlines all the speakers and some of the presentations, visit www.foodsafetycanada. com or click here to register.

ENERGY SUMMIT 2018

Hot on the heels of the Food Safety Summit, EMC and NRCAN are delighted to be hosting Energy Summit 2018. This is the third conference of this nature and strives to help attendees gain relevant insight on energy management, efficiency and innovation. Attendees can learn how Canadian industry is reducing its energy use and environmental footprint. This summit is always a dynamic forum, featuring engaging panel discussions and plant tours. There will be actionable learning and business cases for energy

management, innovation and sustainability. The Energy Summit 2018 program can be accessed at www. energy2018.ca.

EMC FOOD AND BEVERAGE SECTOR NETWORKING SEMINAR – NEXT GENERATION DIGITALIZATION

Our third learning activity takes place on June 5 and is a very special EMC Food and Beverage Sector networking seminar, as it looks at next-generation digitalization and automation solutions. Hosted by Siemens Canada, the seminar is the perfect forum for gaining insights from companies and technology leaders who have successfully embraced next-gen concepts. As we build on the concept of advanced manufacturing, it promises to be an interesting and educational session.

If you would like to join in, simply RSVP at bdeleeuw@emccanada.org.

Three great upcoming learning opportunities, three great ways to connect with peers, industry leaders and subject matter experts on issues of relevance to your business!

If you are interested in learning more about EMC (Excellence in Manufacturing Consortium) and the Food Sector Initiative, please feel free to touch base with Bren de Leeuw, Director – Field Operations Canada and EMC Food, Beverage and Bio Sector Program (bdeleeuw@emccanada.org) anytime!