ABOUT EDA

The Electricity Distributors Association (EDA) represents Ontario’s local hydro utilities, otherwise known as local distribution companies, the part of our electricity system closest to customers. Committed to sustainability, publicly and privately owned utilities deliver electricity to 5.4 million residential, commercial, industrial, and institutional customers – powering every community in the province. The sector owns more than $30 billion in electricity system infrastructure and invests more than $2.5 billion annually in the electricity grid – that is the Power of Local Hydro

TABLE OF FIGURES

LIST OF ACRONYMS

ACM Advanced Capital Module

AMI Advanced Metering Infrastructure

ADMS Advanced Distribution Management System*

BCA Benefit-Cost Analysis

CDM Conservation and Demand Management*

CIR Custom Incentive Rate-Setting

COS Cost-of-Service

CPI Consumer Price Index

DER Distributed Energy Resource*

DERMS Distribution Energy Resource Management* System

DOE Department of Energy (USA)

DR Demand Response*

DSO Distribution System Operator*

DSP Distribution System Plan

EAC Electricity Advisory Committee

EETP Electrification and Energy Transition Panel

EHRC Electricity Human Resources Canada

ESG Environmental, Social, and Governance*

EV Electric Vehicle

FERC Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

FIT Feed-in Tariff

* Defined in Glossary of Terms

GIS Geographic Information System

ICM Incremental Capital Module

IESO Independent Electricity System Operator*

IRM Incentive Rate-Setting Mechanism

ITC Investment Tax Credit

IT Information Technology

LBNL Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

LDC Local Distribution Company*

MDGR Modern Distribution Grid Report

NRCAN Natural Resources Canada

NWA Non-Wires Alternative*

OEB Ontario Energy Board*

OMS Outage management System

OT Operational Technology

P2D Pathways to Decarbonization

SAIDI System Average Interruption Duration Index

SAIFI System Average Interruption Frequency Index

SCADA Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition

TOU Time-of-Use

TWh Terawatt hour

TW Terawatt

VPP Virtual Power Plant

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

ADMS: Advanced Distribution Management System – a software platform that integrates numerous utility systems, including DERMS, and provides automated outage restoration and optimization of distribution grid performance

CDM: Conservation and Demand Management – programs or initiatives that address electricity system needs by helping or incentivizing customers to reduce their electricity consumption

DER: Distributed Energy Resource – an electricity supply source or controllable load that is connected to a distribution system, often through a connection on the customer-side of an ownership demarcation point, such as solar photovoltaic, battery energy storage, or DR

DERMS: Distribution Energy Resource Management System – a technology platform that manages DERs and that can be used to provide aggregated ancillary services to the grid from those DERs

DR: Demand Response – the process or action whereby a customer reduces energy use during times when the electricity system is experiencing high demand and in response to a dispatch signal from a utility or system operator

DSO: Distribution System Operator – a future distribution utility prepared and designed for a high-penetration DER future, including new capabilities and functions, e.g., DER forecasting, DER operations and dispatch, facilitation of local markets for distribution services, and transmission and distribution coordination

ESG: Environmental, Social, and Governance – standards that can be used to measure an organization’s environmental and/or social impact

IESO: Independent Electricity System Operator – the organization that is responsible for operating and maintaining the reliability of Ontario’s power system, administering the province’s electricity market, procuring electricity on behalf of the province’s electricity consumers, and various other responsibilities set out in law

LDC: Local Distribution Company – A utility that owns and/or operates a distribution system that delivers electricity to consumers

NWA: Non-Wires Alternative – a general term for any electrical grid investment that is intended to avoid, reduce, or defer traditional (i.e., “poles and wires”) infrastructure investments in electricity transmission and/or distribution systems

OEB: Ontario Energy Board – a Crown agency that regulates Ontario’s electricity and natural gas utilities, including protecting customers’ interest with respect to the price, reliability, and quality of electricity and natural gas service

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Electricity Distributors Association (EDA) is the trusted and vital source for advocacy, insight and information for Ontario’s local electricity distributors, the municipally and privately owned companies that safely and reliably deliver electricity to millions of Ontario homes, businesses and public institutions. We provide analysis, networking opportunities, and a collective voice on issues vital to our members’ business success.

We commissioned Power Advisory LLC, along with project partners at Elenchus Research Associates and the Centre for Urban Energy (CUE) at Toronto Metropolitan University to research and produce this report in coordination with our board steering committee.

Power Advisory is an energy sector management consulting firm focused on the North American electricity markets with expertise in wholesale market design and market products. Their consulting services are provided by seasoned energy sector professionals, offering a wide breadth and significant depth of industry knowledge. This experience and knowledge, combined with a detailed understanding of market fundamentals, yield the strategic insights that provide clients with market advice that achieves desired outcomes while mitigating project risk and delivering value to customers. Since their founding in 2007, Power Advisory has provided high quality and customized consulting services to clients across the sector, including the EDA. Power Advisory offers a well-balanced team of economists, engineers and policy experts with experience working with Ontario’s agencies, regulators, industry and decisionmakers. They serve a wide range of clients including distributors, transmitters, generators, regulators, system operators and investors.

Elenchus Research Associates is a recognized leader in the development and design of rates for regulated utilities, the design of regulatory mechanisms (including incentive regulation), regulatory compliance and strategy. Its clients include five Canadian regulators as well as regulated utilities and a wide range of stakeholders across Canada. Elenchus assists clients in all aspects of regulatory proceedings, policy development and strategic planning. Over the past 30 years, Elenchus has also been retained by dozens of stakeholders for energy regulation proceedings in Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Elenchus has extensive experience working with the full range of interested parties, including customer groups and regulators, making Elenchus ideally suited to anticipating the concerns of stakeholders.

CUE is an academic-industry partnership established in 2010 that is exploring, developing and commercializing sustainable, innovative, costeffective and practical clean energy solutions and technologies. CUE brings together industry and government partners, and top researchers from across Canada and around the world to undertake a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to the study of urban energy. CUE combines engineering, science, environmental issues, and infrastructure management to tackle immediate challenges such as the development of clean energy technologies; the advancement of smart grid technologies; the integration of energy storage, electric vehicles and renewables; energy conservation and demand management; alternative local energy generation; carbon footprint reduction; and net-zero buildings and infrastructure.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Ontario’s local distribution companies (LDCs) are pivotal in enabling Ontario’s low-carbon economy, navigating challenges posed by climate action policies, electrification trends, and evolving customer demands. With Ontario’s economy growing and the demand for housing intensifying, LDCs must innovate to effectively meet accelerating electricity needs and changing customer preferences. Projected electricity consumption in Ontario is expected to rise significantly, from 144 TWh in 2023 to 245 TWh in 2050. This rapid growth demands urgent attention to adopt new strategies and ensure LDCs can make the necessary investments in grid enhancements to expand the capacity and capability of the distribution system.

Electricity reliability and affordability remain paramount, though customers now expect additional value from their service. While Ontario customers are not a uniform, monolithic group, all customers assume that LDCs will be there to support their changing electricity needs, such as swift electric vehicle (EV) charger installations and other upgrades to increase electrical load. Furthermore, LDCs are more frequently interacting with businesses that seek utility partners to achieve their energy management and sustainability goals. In parallel, LDCs must also prepare to respond to increased climate changeinduced extreme weather events.

Recognizing the essential role of LDCs in the energy transition, we (the EDA), in collaboration with industry experts, outline a vision for the role of Ontario’s LDCs as they enable economic development, housing growth, and electrification. This report identifies urgent and practical steps that LDCs, in partnership with the Government of Ontario and its agencies, must take in the near term to be grid ready and to achieve the benefits of this transition. It underscores the need for clear policy direction and regulatory frameworks to support LDCs in making necessary investments with a continued focus on affordability and enabling customer choice. The paper also addresses workforce needs and emphasizes the essential role of human capital in enabling technological advancements.

Rising electricity demands will require LDCs to update their investment plans to enhance the capacity and capabilities of distribution system infrastructure. To address the growing peak demand, LDCs must allocate additional funds towards new infrastructure and the ongoing renewal of existing assets. Historically, annual LDC spending on gross capital additions has averaged around $2.5 billion across Ontario. By projecting future energy demands on the distribution system, we estimate that annual spending on gross capital additions may need to double by the mid-2040s under a net-zero scenario and increase by approximately 130% from current levels by 2050. Even with more moderate electrification assumptions, annual gross capital additions by all Ontario LDCs could increase by nearly 45% by 2050. Cumulatively, Ontario’s LDCs are projected to spend approximately $103 billion on gross capital additions from 2024 to 2050 with moderate electrification assumptions, and could spend up to $120 billion on gross capital additions from 2024 to 2050 under a net-zero scenario (see Section 4). Given the magnitude of potential investment required and the affordability imperative, we make recommendations regarding funding approaches to lessen the impact on ratepayers (see Section 7).

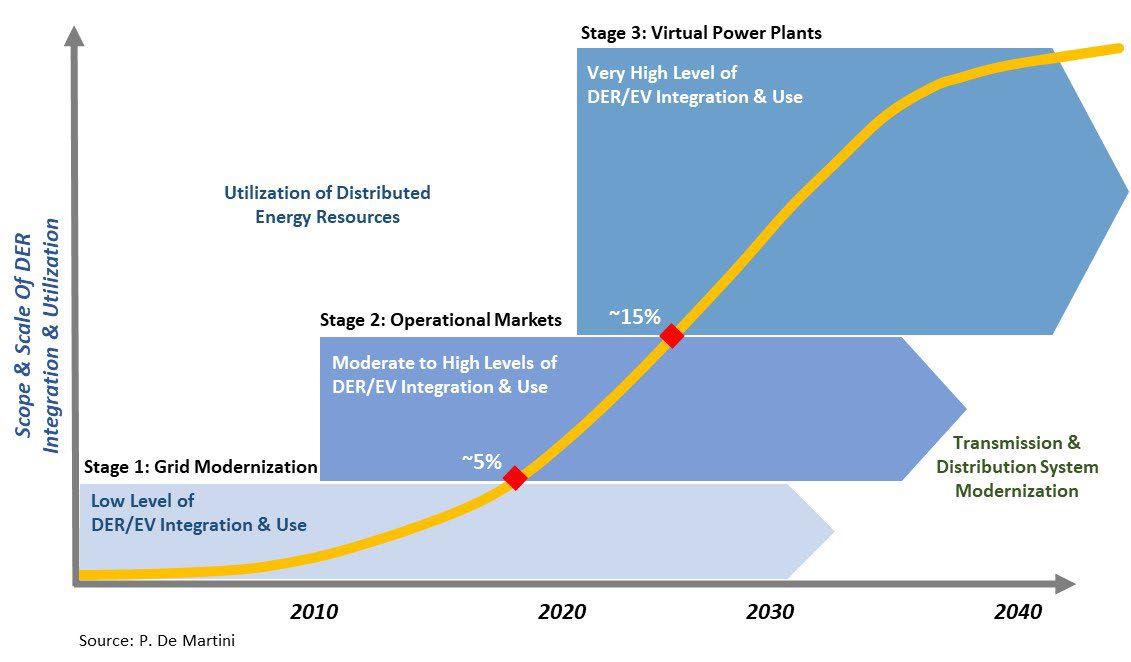

LDCs play a crucial role in enabling the integration of customer-driven distributed energy resources (DERs) and enhancing grid reliability through investments in enabling technologies. With the increasing connection of DERs, coordination with the Independent Electricity System Operator’s (IESO) wholesale market becomes essential, involving communication of distribution constraints and real-time outages affecting DER availability. By adopting the functions of a Distribution System Operator (DSO), LDCs can further facilitate the co-optimization of DER operations and dispatch, which is crucial for their integration into the wholesale market, particularly considering DERs may operate as IESO market participants, impacting LDC planning and realtime operations.

Notably, we estimate that DERs could offset distribution-level spending of between $200 million and $800 million annually by 2030 (see

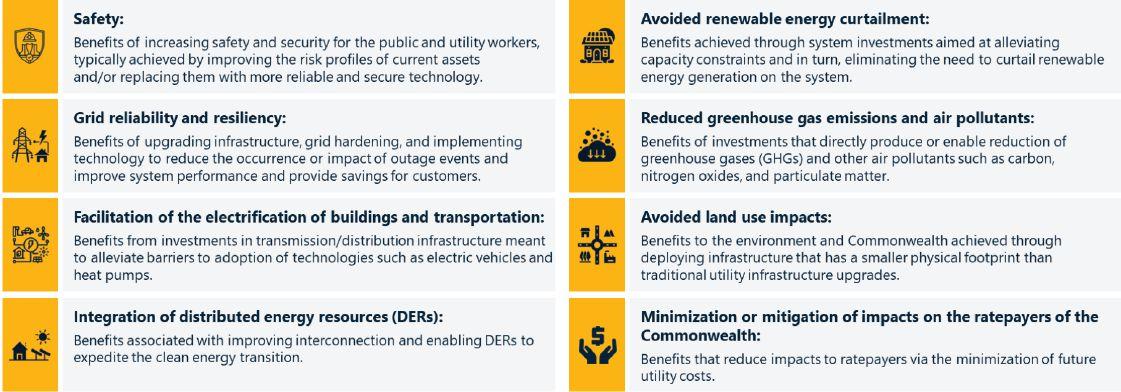

Section 5), with higher achievable savings if the barriers to achieving the full economic potential of DERs were addressed. Furthermore, we describe the many benefits that investments in grid-enabling technologies can bring to Ontario, including:

• Improved grid reliability and resilience

• Reduced greenhouse gas emissions

• Improved safety and cybersecurity

• Enabled electrification and integration of DERs

• Avoided energy costs (i.e., electricity supply costs)

• Avoided capacity costs (i.e., electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure costs)

• Enhancing economic competitiveness

This report outlines the challenges utilities encounter when assessing necessary grid-enabling investments. While performance metrics exist, broader system and societal benefits are often difficult to quantify monetarily, unlike costs and their subsequent rate impacts, which are more straightforward. Drawing on insights from other jurisdictions, we assert that certain grid-enabling investments are non-discretionary based on established need and policy priorities and that these non-discretionary investments should be assessed on a best-fit and reasonable cost basis rather than through benefit-cost analysis (BCA). However, for discretionary investments aimed at evaluating multiple potential options and reducing system costs, BCA should be utilized to evaluate cost-effectiveness.

To advance grid modernization and energy transition objectives, the report recommends specific policy and regulatory enablers that can be developed and implemented in the near-term, including the establishment of clear evaluation frameworks, performance metrics, and filing requirements for grid modernization investments. It calls for mechanisms to support LDCs in implementing grid modernization technologies and enhancing climate resilience, recognizing the urgent need for LDCs to prepare for increasing policy-driven and customer-driven demands on the distribution system.

We propose the following policy enablers, including:

• Developing, together with the Ministry of Energy and the Ontario Energy Board (OEB), a clear and shared

definition of electrification and grid modernization objectives for Ontario.

• Providing firm and clear direction regarding the need for foundational grid modernization investments.

• Clarifying the role of the OEB in advancing grid modernization.

• Defining clear criteria/path for adopting lessons learned from grid modernization pilots and moving to system-wide deployment.

• Supporting recommendations to address quantity, quality, and partnership aspects of the electricity sector workforce.

• Considering alternative funding approaches and reviewing current funding policies to support the required investments for the transition of the energy sector in Ontario.

From a regulatory perspective, we outline the following enablers:

• Aligned with policy directives, the OEB should take the lead in finalizing a comprehensive evaluation framework, encompassing performance metrics and filing guidelines for grid modernization investments.

• Exploration of regulatory measures to bolster grid modernization efforts, such as reducing thresholds for grid modernization investments to streamline approval processes and enhance cost recovery, allowing greater access to funds in an Incentive Rate-Setting Mechanism (IRM) term, mandating Distribution System Plans (DSPs) to incorporate a dedicated grid modernization segment, tracking progress in alignment with regulatory recommendation, and allowing the capitalization of digital technologies crucial for grid modernization to facilitate their implementation, amongst other recommendations.

Ultimately, the report highlights the urgency of action to ensure LDCs are equipped to meet the evolving needs of Ontario’s energy landscape and contribute to a sustainable and economically prosperous future for all Ontarians. We are encouraged by the progress made to date in Ontario and looks forward to being a supportive partner in enabling the energy transition, where LDCs play a pivotal role in empowering communities across the province in meeting their economic, environmental, and societal goals.

1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Ontario’s local distribution companies (LDCs) are at the forefront of the energy transition and the clean energy economy. Climate action and electrification policies, as well as changing customer preferences, are having a profound impact on Ontario’s electricity grid. Ontario’s economy is growing and electrifying, creating new opportunities for LDCs to support customers and putting new pressures on LDCs to innovate.

With the rising penetration of distributed generation from renewable sources, the direction of energy flows within the grid is becoming less predictable, often characterized by a reversal of power flow, even from distribution to transmission grids, requiring the deployment of new digital technologies.

International Energy Agency, Electricity Grids and Secure Energy Transitions (October 2023)

The pace of Ontario’s projected electricity growth is unprecedented. Ontario’s annual electricity consumption is forecast to increase from 144 TWh in 2023 to 245 TWh in 2050.1 Decarbonizing Ontario’s electricity supply could require the addition of 69 GW of non-emitting supply and 5 GW in demand reductions from energy conservation.2 In the near term, beginning around 2030, Ontario will require approximately 5 TWh of new energy. 3

Meeting Ontario’s electricity needs is going to require a coordinated approach across Ontario’s electricity sector and the integration of new enabling technology to modernize the electricity grid. While much of Ontario’s electricity needs will be satisfied by largescale investments in the bulk system, distributed energy resources (DERs), including renewable sources, energy storage, energy efficiency, and demand response (DR), are expected to play an important role in meeting electricity demands. Indeed, it is estimated that DERs could cost-

effectively satisfy 1.3 to 4.3 GW of peak summer demand by 2032.4

[S]ignificant infrastructure investment is needed to not only meet greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets, but to ensure a reliable, equitable and affordable energy system for Ontarians.

Climate Risk Institute. Ontario Provincial Climate Change Impact Assessment: Technical Report.

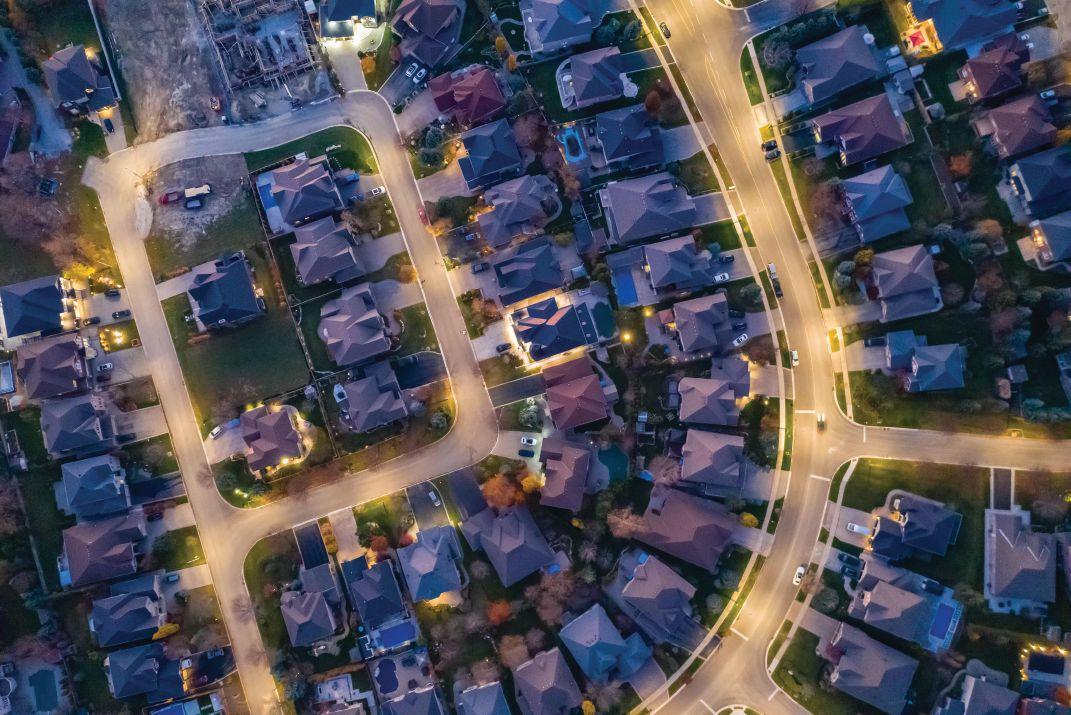

Although electricity reliability and affordability are table stakes, customers now expect additional value from their electrical service. For example, residential customers expect to connect new electric vehicle (EV) chargers expeditiously upon purchase, and businesses are seeking more options for renewable energy supply to meet their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) mandates. Ontario’s electricity grid needs to keep pace with economic development, housing development, and electrification. As electricity demand grows and increased volumes of DERs are connected, significant investments in distribution services are needed. LDCs require new tools, technologies, and processes to reliably operate an increasingly complex grid.

The strong link between the electricity distribution system and broader provincial objectives has been highlighted by the Ontario Energy Board’s (OEB) recent announcement that it is undertaking a policy review of electricity distribution system expansion for housing development, following the Minister of Energy’s Letter of Direction dated Nov. 29, 2023, requesting the OEB to “review its electricity distribution system expansion connection horizon and revenue horizon direction to ensure that the balance of growth and ratepayer costs remain appropriate ”56

1 IESO, Annual Planning Outlook (APO), March 2024, p. 30: https://www.ieso.ca/-/media/Files/IESO/Document-Library/planning-forecasts/apo/ Mar2024/2024-Annual-Planning-Outlook.pdf

2 IESO, Pathways to Decarbonization, December 2022, p. 2: https://www.ieso.ca/-/media/Files/IESO/Document-Library/gas-phase-out/Pathways-toDecarbonization.ashx

3 IESO, Evaluating Procurement Options for Supply Adequacy, Resource Adequacy Update to the Minister of Energy, December 2023, p. 4: https:// ieso.ca/-/media/Files/IESO/Document-Library/resource-eligibility/Evaluating-Procurement-Options-For-Supply-Adequacy.ashx

4 Dunsky Energy + Climate Advisors, Ontario’s Distributed Energy Resources (DER) Potential Study Volume I: Results & Recommendations, September 28, 2022, p. 16: https://www.ieso.ca/-/media/Files/IESO/Document-Library/engage/derps/derps-20220930-final-report-volume-1.ashx

5 OEB, Engagement on Electricity Distribution System Expansion for Housing Development, March 13, 2024: https://www.rds.oeb.ca/CMWebDrawer/ Record/843877/File/document

6 Minister of Energy, Letter of Direction, November 29, 2023: https://www.oeb.ca/sites/default/files/letter-of-direction-from-the-Minister-ofEnergy-20231129.pdf

In parallel, Ontario’s electricity grid requires investments to provide increased resilience because of climate changeinduced extreme weather. The electricity system is vulnerable to extreme heat, extreme precipitation, storms, wildfires, and other events that can damage, destroy, and shorten the lifespan of electricity infrastructure leading to electricity service failures, disruptions, outages, brownouts, blackouts, and reductions in efficiency 7

These events can have serious economic consequences for Ontario’s industries and businesses, not to mention health and safety impacts, particularly for vulnerable populations.

What becomes clear to us and our members from looking at the combination of the energy transition and climate change is that Ontario’s electricity system and LDCs will be called upon to play an increasingly central role as the backbone of not only serving Ontario’s energy needs, but also delivering its overall economic, environmental, and societal benefits.

LDCs will continue to be responsive to government policy direction, economic development, climate risks, and residential housing growth, as well as customer trends towards greater electrification (e.g., EVs, heat pumps, etc.) and DERs (e.g., solar, storage, etc.) – all while meeting ever-increasing affordability, performance, and reliability expectations To meet these challenges, we believe that LDCs must continue to transform and evolve to manage their systems more actively, using tools as varied as demand side management, wireless networks, and

Modernizing the electricity grid to maintain reliability, affordability, and sustainability, and to enable customer choice

weather forecasts and modelling. LDCs are responsible for facilitating DER connections, managing the balance of electricity flows on their system, and more actively engaging and understanding their customers’ preferences and trends.

On July 10, 2023, the Government of Ontario published Powering Ontario’s Growth, which sets out the government’s plans for the province’s energy system. It includes plans for new zero-emissions electricity generation, long-duration storage, and transmission lines, and tasks the Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) with several resource acquisition and system planning initiatives. The report highlights the essential role of the electricity sector in enabling a clean energy economy. A summary of recent policy developments influencing Ontario’s LDCs is provided in Appendix A

Energy and economic development have always been tightly linked. Access to reliable and affordable energy has been a key component of economic growth. Now too, the energy transition is seen as key to facilitating economic development, job creation, and attracting capital investment. Access to affordable, reliable, and clean energy is now seen as central to economic competitiveness, and Ontario’s “world-class clean electricity grid” as a “competitive advantage to drive investment and create jobs.”8

The ongoing changes in Ontario’s energy use and production landscape present a significant opportunity for LDCs to assist in meeting various governments’ climate-

7 Climate Risk Institute. Ontario Provincial Climate Change Impact Assessment: Technical Report. Report prepared by the Climate Risk Institute, Dillon Consulting, ESSA Technologies Ltd., Kennedy Consulting and Seton Stiebert for the Ontario Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks. January 2023, p. 403: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-provincial-climate-change-impact-assessment

8 Ontario Newsroom, New Ontario Clean Energy Registry Will Make Province Even More Attractive for Investment, January 2022: https://news. ontario.ca/en/release/1001486/new-ontario-clean-energy-registry-will-make-province-even-more-attractive-for-investment

Figure 1. Impacts of Energy Transition on Electricity Sector

1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

related, economic, and housing policies and targets, advance grid modernization, and ‘unlock’ capabilities of DERs to help meet Ontario’s electricity supply needs and economic growth. In fact, electrification and fuelswitching policies related to the energy transition are making the affordable, reliable, and resilient services of LDCs and the electric system in general more important than ever before for maintaining and enhancing provincial economic competitiveness and attracting capital investment.

We engaged Power Advisory LLC, along with partners at Elenchus Research Associates and Toronto Metropolitan

University, to support the development of this paper. Here we outline our vision of the role of Ontario’s LDCs as the economy transitions to a low carbon future and demonstrates how Ontario’s LDCs will continue to contribute to the prosperity of Ontario and the communities they serve. Further, this paper identifies practical and urgently needed actions that Ontario’s LDCs must take in the near term, working together with the Government of Ontario and its agencies, to unlock these opportunities and ensure Ontarians benefit from the energy transition.

2. ONTARIO’S LDCS IN THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Ontario’s LDCs are responsible for ensuring the safe, reliable, and affordable delivery of electricity to their customers. LDCs engage in the planning, investment, construction, and maintenance of distribution assets designed to meet the peak demand of customers within their service territory and address various other needs, such as having the capacity available to connect new homes and new businesses. While LDCs are responsible for customer metering installations and have access to customer metering data, additional visibility into day-today grid conditions has not, until now, been a necessity. This is due to the relatively low level of DERs connected and relatively predictable customer electricity usage patterns.

Over the last two decades, Ontario’s LDCs have consistently and continuously modernized their systems in response to government policy initiatives, regulatory requirements, and evolving customer preferences. Ontario’s LDCs successfully demonstrated leadership and a spirit of collaboration through such initiatives as:

• Implementing the smart meter rollout, implementation of time-of-use (TOU) pricing (including recent Ultra-

Low Overnight pricing), tiered pricing and systems integration with the Smart Metering Entity

• Implementing Green Button and providing data access to customers

• Connecting DERs through various programs, such as net metering, microFIT, and Feed-in Tariff (FIT) initiatives

• Delivering conservation and demand management (CDM) programs that delivered bill savings to residential and business customers as well as energy and capacity savings to the system

• Facilitating and implementing the government’s efforts to use electricity infrastructure for Ontario’s Broadband and Cellular Action Plan

• Undertaking innovative, forward-looking pilots assessing different LDC models/functions as well as facilitating electrification and the energy transition, such as Alectra’s York Region Non-Wires Alternative (NWA) Demonstrations, Essex Powerlines’ Distribution System Operator (DSO) Pilot-Powershare Project, Hydro One’s Vehicle-to-Home Project; and Hydro Ottawa’s Electric Vehicles Everywhere Project.

roles…

Emerging LDC Requirements

• Asset Ownership

• Asset Management

• Network Reliability

• Customer Metering, Billing, Settlement

• CDM / DERs

• Prepare for Electrification

• DERs as NWAs

• Enhanced DER Connections

• DER Rate Design

• Enhanced Load Forecasting

• Enabling Electrification

• Enhanced Customer Programs and Support

• Fully Support Electrification

• DSO Functions (e.g., DER Forecasting, DER Operation and Dispatch, Local Markets, T-D Coordination, etc.)

• Enhanced Data Management and Information Platforms

• Customer Choice (e.g., rate options, supply options, etc.)

• Climate Resilience

Figure 2. LDC Roles and Functions Emerging in the Energy Transition

Ontario’s LDCs are ready, willing and able to take on new challenges to prepare for the future and assist with broader government policy objectives and goals.

New Services to Customers

As the energy landscape undergoes a transformation towards the clean energy economy, LDCs will play an essential role in facilitating this transition by offering a suite of innovative services to customers. Ontario’s LDCs have a strong history of supporting customer programs and services through the delivery of CDM programs.

We recognize that Ontario’s electricity customers are not a monolithic, uniform group. Customers have diverse needs and preferences, and it is essential that LDCs engage with their unique communities and customers as they develop investment plans. However, broad electricity sector trends impacting the province cannot be ignored, such as a shift away from the use of fossil fuels, integration of new technologies, and desire for affordable, safe, and reliable electricity services.

One key area where LDCs can lead is in supporting electrification initiatives that enable customer adoption of EVs and heat pumps.9 This includes facilitating the connection of EV charging infrastructure to the grid, expanding access to charging infrastructure within an LDC’s service territory, and providing programs that remove barriers to heat pump installation.

To meet both customers’ preferences and Ontario’s emerging needs for non-emitting generation, LDCs can play a crucial role in enabling the integration of DERs. This involves streamlining the process for customers to connect their renewable supply to the distribution network, as well as implementing smart grid technologies to manage the variability of renewable generation and provide flexible hosting capacity where technically feasible. LDCs can also offer a range of programs to support customer choice in the adoption of renewable energy supply, such as green choice/green tariff programs.

LDCs can empower customers by offering greater choice through innovative rate design (e.g., interruptible rates, EV rates, etc.) and energy management solutions. By providing flexible pricing options, such as new TOU rates

The Green Choice program offers a new, simplified process for large-scale energy customers to procure renewable electricity. This program was designed to help governments, public institutions, corporate and industrial electricity customers in Nova Scotia to achieve their greenhouse gas emissions reductions targets. The new renewable energy projects procured through the Green Choice Program will generate renewable electricity for which participants can subscribe up to 120% of their annual electricity consumption.

Nova Scotia, Department of Natural Resources and Renewables, Green Choice Program Participant Guide (December 2023)

or DR programs, LDCs can incentivize customers to shift their energy usage to off-peak hours, thereby reducing strain on the grid and lowering overall energy costs. Moreover, by offering energy management tools and services, LDCs can empower customers to make informed decisions about their energy consumption and optimize their consumption or use of renewable resources.

Furthermore, LDCs can promote affordability initiatives and energy conservation efforts. These opportunities include implementing energy efficiency programs such as home energy audits and rebates to help customers reduce their energy bills and minimize their environmental impact. Additionally, LDCs can collaborate with community organizations and government agencies to provide financial assistance to low-income households for energy efficiency upgrades and weatherization measures.

As LDCs integrate new technologies and enhance their capabilities, they can leverage advanced analytics and data-driven insights to enhance their services and improve customer engagement. By providing access to real-time energy usage data and personalized recommendations, LDCs can empower customers to make smarter energy choices and optimize their energy consumption. Moreover, by investing in smart grid technologies and predictive analytics, LDCs can improve grid reliability and resilience, thereby reducing the frequency and duration of power outages and enhancing overall system performance. This is imperative for LDCs as regulators often lean on the system average interruption frequency

9 Natural Resources Canada describes heat pumps as electricity-driven devices that extract heat from a low temperature place (a source) and deliver it to a higher temperature place (a sink). The two commonly used sources are air-source and ground-source. Hybrid models also exist where heat pumps can be both electrically driven or natural-gas driven: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/energy-efficiency/energy-star-canada/about/ energy-star-announcements/publications/heating-and-cooling-heat-pump/6817#b

Bulk Transmission System

and duration (SAIFI and SAIDI) indicators to measure distribution system performance.

In terms of the types of programs that LDCs can offer, there are many examples from other jurisdictions from which Ontario can learn, as well as the experience of Ontario LDCs themselves:

• Customer-facing websites, online tools, calculators, and hosting capacity maps to inform customer decisions concerning connecting EV charging infrastructure, installing heat pumps, installing solar, etc.

• Enabling enhanced reliability and resilience service offerings, such as microgrids/islanding capabilities, to customers and communities, which are being piloted by utilities in Ontario and the United States.

• Green-choice programs or green tariffs are offered in multiple jurisdictions across North America, including Nova Scotia, Michigan, Colorado, Georgia, and Nevada.

• EV make-ready programs that support customer connection of EV charging infrastructure by offsetting connection costs are offered in multiple jurisdictions, for example in Massachusetts and New York.

• EV fleet advisory services are offered in multiple jurisdictions, including Illinois and Massachusetts.

• EV rates (i.e., delivery rates) are offered in multiple jurisdictions including Quebec, British Columbia, California, New York, and Massachusetts.

• Managed EV charging programs to mitigate system demand and infrastructure impacts of EV charging, as found, for example, in Connecticut and New York.

• Flexible (curtailable) connection arrangements allowing DERs to connect to feeders that may face technical capacity constraints (rather than waiting and/or paying for needed upgrades prior to connecting) in exchange for giving the distributor the ability to curtail output when system conditions warrant, as found, for example, in the United Kingdom and countries in the European Union.

• Load control programs and interruptible rates, which allow the LDC to either directly control or curtail a customer’s load (often air conditioners or electric water heaters) to help manage demand on the distribution system, or offer customers a reduced rate in exchange for the LDC having the right to call for curtailment of supply under specific circumstances. Load control

Figure 3. Increasing complexity and two-way flows in the distribution system

programs are common in many jurisdictions and have recently been reintroduced in Ontario via the IESO’s “Peak Perks” program. Interruptible rates are currently being piloted in Ontario’s electricity sector (having been common for many years in the natural gas sector) and are also available in other jurisdictions such as Quebec.

Further case studies are described in Appendix F

By embracing innovation and adopting a customer-centric approach across the sector, LDCs can not only drive economic development and foster social equity, but also play a vital role in accelerating the transition towards a cleaner, more resilient energy system.

Evolving LDC Roles & Responsibilities

With increases in DERs and electrification, there are pressures for LDCs to adapt, modernize, and change. LDCs will continue to be responsible for the safe, reliable, and affordable delivery of electricity to customers. However, the landscape is evolving with increasing customer connection requests for DERs, including solar, storage, and EVs, and the emergence of new energy service providers, such as DER aggregators, as illustrated in Figure 3

With advancements in technology and reduced costs of DERs and other technologies, LDCs are positioned to leverage DERs and NWAs as distribution system assets. This offers the potential of offsetting or deferring the need for traditional distribution assets and even mitigating the need for upstream transmission investments. This shift introduces heightened complexity to distribution system planning (as well as the bulk system), requiring serious consideration of customer DERs and NWAs, including storage, DR, CDM, and EV smart charging, among other opportunities.

Moreover, the day-to-day operations of distribution systems have become more intricate, demanding investments in grid visibility and controls to effectively coordinate the operations of NWAs. Despite these changes, LDCs maintain their status as non-dispatchable loads in the IESO’s wholesale market. Yet, forecasting LDC demand at “nodes” presents growing challenges for the IESO, driven by the increasing uptake of DERs and EVs for customer use, as well as DERs utilized by LDCs for NWAs. The inherent unpredictability of nodal demand on a day-to-day and minute-to-minute basis, compounded by

embedded DERs not visible to the IESO, adds complexity to the IESO’s forecasting process.

As LDCs engage in the procurement of DERs, it becomes imperative for these resources to be considered and accounted for in the IESO’s power system plans and broader procurement initiatives. This underscores the evolving role of LDCs in an energy landscape that is increasingly being shaped by the integration of decentralized and renewable energy resources and more active customers/users of the distribution system.

New Roles & Responsibilities

Amidst the significant and broad electrification across the sector and uptake of DERs, LDCs must continue their essential role of delivering electricity to customers. However, in addition to this core responsibility, LDCs will need to take on a much more active engagement in facilitating and controlling the operations and location of DERs in an efficient way. This will require undertaking tasks such as forecasting, communication, and dispatch management while navigating grid constraints. The administration of “local markets” stands out as a key function that can be performed by LDCs, and may consist of various platforms for procurements, programs, and price signals tailored to a spectrum of distribution services.

The increasing complexity of day-to-day and minute-tominute operation of the distribution system necessitates investments in grid visibility, monitoring and control, automation, communications, telemetry, and related technologies. This infrastructure is critical for effectively coordinating and dispatching DERs in response to dynamic conditions. Going forward, LDCs will play a more pivotal role in enabling efficient investments and operations by leveraging data management, information platforms, and responsive price signals.

These new functions are often described as “DSO functions”. As a DSO, LDCs would have multiple options to actively coordinate with the IESO’s wholesale market, such as communicating distribution constraints and real-time outages that impact DER availability. Co-optimization of DER operations and dispatch, facilitated by collaboration with the IESO, enables the integration of DERs into the wholesale market. Two-way operability coordination with the IESO is especially necessary recognizing that LDCs need to account for DERs operating as IESO market participants, which will impact LDC planning and real-time operations.

4.

from Extreme Weather Events in Ontario

Despite the growing imperative for LDCs to evolve and adapt to the changing energy landscape, several barriers and challenges impede progress towards realizing new roles and responsibilities as Ontario undergoes deeper electrification of our economy. For instance, there is policy uncertainty regarding a shared understanding of the expected roles and accountabilities of LDCs, including but not limited to the possibility of some undertaking DSO functions. A lack of coordination in the energy sector hinders the development of a cohesive approach to DER integration (and electrification more broadly), one which would recognize the value of DERs to the customer, distribution system, and bulk system. Moreover, there is a lack of guidance to LDCs regarding grid-enabling investments that would unlock new capabilities while optimizing and maximizing the existing distribution grid to provide overall ratepayer value. We observe that there is a need for greater clarity on the division of responsibilities and coordination among stakeholders to advance toward new LDC roles effectively. These challenges underscore the pressing need for proactive policy and regulatory interventions to address these barriers and empower LDCs to embrace their evolving roles in shaping the future of the energy sector.

Climate Resilience

While LDCs are preparing for changes to the distribution network resulting from changing customer needs and technology adoption, they also need to prepare for extreme weather events that are increasing in frequency and magnitude due to climate change. In northern climates such as Ontario, the scale of climate change is likely more pronounced in some ways than global averages. Accounting for extreme weather in electricity planning is a best practice. Extreme weather can impact electricity demand, supply, transmission, and distribution, leading to greater uncertainty and prolonged outages.

The Government of Ontario released its first Climate Change Impact Assessment10 in 2023. The report indicated that there was a high risk to electrical power generation and a medium risk to electrical transmission, control, and distribution, with a projection of medium to high risk expected in the 2050s. For electricity distribution, winter precipitation, extreme winds, and extreme heat are the greatest drivers of risk. Winter precipitation can cause significant equipment damage to distribution infrastructure. The build-up of snow on nearby tree branches and extreme winds may interfere with the lines and cause contacts or outages. Extreme heat can reduce the carrying capacity of distribution lines and damage substations and transformers.

10 Climate Risk Institute. Ontario Provincial Climate Change Impact Assessment: Technical Report. Report prepared by the Climate Risk Institute, Dillon Consulting, ESSA Technologies Ltd., Kennedy Consulting and Seton Stiebert for the Ontario Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks. January 2023: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-provincial-climate-change-impact-assessment

Number of Customer Interruptions

Number of Customer Hours of Interruptions

Figure

Electrical Interruptions

The OEB keeps records of electrical interruption incidents by LDC as shown in Figure 4 11 In 2015, there were approximately 570,000 customer interruptions with a sudden increase to approximately 1.6 million customer interruptions in 2018 due to extreme weather events, and then declining to 2015 levels in 2021. However, the greatest record for interruption was in 2022. In May 2022, Hydro One cited a record-breaking 1,90012 broken poles and nearly 652,000 customers interruptions due to a derecho windstorm. A derecho is a widespread, long-lived, straightline windstorm that is associated with a fast-moving group of severe thunderstorms known as a mesoscale convective system. Derechos can cause hurricane and tornadic-level winds, heavy rains, and flash floods. In Ottawa, the airport and water treatment plant lost grid power for more than 24 hours. In a letter to Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson, Hydro Ottawa described the damage dealt to its power distribution system as “beyond comprehension” and more severe than the 2018 tornadoes or the 1998 ice-storm, which impacted much of northeastern North America.

The challenge ahead is determining what adaptation and resilience steps must be taken to address the risk that climate change has on the distribution system. It requires being informed and mindful of the interconnectedness of electricity infrastructure on the five key systems stipulated by Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy, namely: disaster resilience, health and well-being (including considerations of equity), nature and biodiversity, infrastructure, and economy and workers. LDCs will need to evaluate alternative metrics and analytical techniques to

make investment decisions because current approaches rely on historical data and often do not consider long time horizons.

Ontario’s LDCs are already updating their load forecasting methodologies and equipment specifications based on anticipated climate change. The increasing risk of distribution equipment outages due to extreme weather also highlights the potential reliability and resilience benefits of new technologies. For example, advanced sensing and control technologies can enable fault location, isolation, and service restoration (FLISR) software, ultimately reducing the impact and duration of outages. LDCs should be able to take proactive steps to adapt to climate change and make their grids more resilient in the face of changing environmental conditions. One of these steps involves grid hardening, which is crucial to ensure the reliability and security of the power supply. Grid hardening to mitigate against climate change includes strengthening and upgrading the physical components of the grid, such as distribution lines, transformers, and substations. Reinforcing these elements makes the grid more robust and less susceptible to damage from severe weather events, natural disasters, or physical attacks. Some LDCs have already proposed such investments in rate applications to the regulator, and while some investments have been approved, others have been turned down. A shared understanding between LDCs and the OEB as to the importance of system hardening will be essential going forward given likeliness of more extreme weather events.

11 Ontario Energy Board, Natural Gas and Electricity Utility Yearbooks, September 29, 2022, System Reliability Microsoft Excel File: https://www.oeb. ca/ontarios-energy-sector/performance-assessment/natural-gas-and-electricity-utility-yearbooks#elec

12 Hydro One, Hydro One Restores Power to More Than 652,000 Customers Following Saturday’s Devastating Storm, May 26, 2022: https://hydroone. mediaroom.com/2022-05-26-Hydro-One-restores-power-to-more-than-652,000-customers-following-Saturdays-devastating-storm

3. THE NEED FOR ACTION

As the pace of growth and electrification accelerates, there is an urgent need to ensure a strong foundation for the clean energy economy. It is crucial to be proactive in safeguarding the system against potential disruptions and proactively address barriers to growth. LDCs need to work alongside governments and communities to establish a strong framework for the future, enabling collaborative efforts to address emerging needs and opportunities in the energy sector.

Inaction may lead to significant challenges for Ontarians in the future. The following presents anecdotal examples to illustrate the potential magnitude and significance of inaction.

• Potential for higher costs relative to a businessas-usual scenario: Maintaining the status quo risks perpetuating outdated infrastructure, leading to higher costs for consumers compared to investing in innovative strategies to optimize the use of existing infrastructure and resources. Failure to upgrade the grid may result in increased operational inefficiencies and maintenance costs, which could ultimately be passed on to customers through higher electricity rates.

For example, Eversource, located in Massachusetts, implemented a Volt/VAR optimization (VVO) grid modernization program starting in 2018 to deploy new equipment and software to adjust power flows to reduce line losses. The company has reported that feeders where VVO has been installed have seen a 2% reduction in energy use and 1.8% reduction in peak demand.13

In Ontario, PUC Distribution estimates that its Sault Smart Grid project, using a VVO, will result in a 2.7% reduction in energy consumption and deliver a net present value of benefits to customers of $12.51 million.14

• Lost opportunity to maximize the value of distributed resources to support resource adequacy: Without proactive investment in grid enhancements, Ontario may not realize the potential benefits of DERs as offsets to the need for bulk system supply. Ontario’s electricity outlook projects a need for significantly

more resources, so it is an opportune time to ensure the benefits from existing and new DERs are optimized and integrated into provincial procurement plans. DERs are expected to play an increasing role in the supply mix, due to ease of permitting and integration into existing sites. The IESO has already secured distributed energy storage resources as part of its Expedited LongTerm (E-LT) procurement and is expected to procure more distributed energy storage as part of the LongTerm 1 (LT1) RFP. Further, the IESO has stated a need to enable the participation of DERs in the energy-focused Long-Term 2 (LT2) RFP. The E-LT procurement resulted in costs of approximately $881/MW-business day for storage resources and $1,093.22/MW-business day for non-storage resources (i.e., gas-fired generation).

Ontario is tracking to spend just under $300 million per year on E-LT awarded capacity with a further $550 million per year possible from LT1 (results of which are expected sometime in the first half of 2024). Resource adequacy and real-time market efficiencies require that DERs awarded through the procurements have complete access to the IESO-Administered Markets. This requires grid modernization and enhanced integration between distribution network operation and the IESO-Controlled Grid.

• Lack of data protection/cybersecurity investments could compromise customer privacy and grid security: Inadequate measures to protect customer data and secure critical infrastructure from cyber threats pose significant risks, especially as more electricity infrastructure (both in front of and behind the meter) is automated and moved to digital technologies. Maintaining outdated systems and a lack of skilled cybersecurity professionals may leave the grid vulnerable to cyberattacks, potentially compromising customer privacy and disrupting essential services as well as the economy. For example, in 2023, estimates indicate that the global average cost of a data breach was $6 million, with the cost of a breach for the Canadian energy sector amounting to $9.37 million on average.15 The International Energy Agency has noted

13 Eversource, Electricity Sector Modernization Plan, January 2024, p. 445: https://www.eversource.com/content/docs/default-source/defaultdocument-library/eversource-esmp%20.pdf

14 PUC Distribution Inc., 2022 Incentive Rate-Making Application (EB-2021-0054), November 24, 2021, p. 10: https://ssmpuc.com/UploadedFiles/files/ PUC_2022_IRM%20Rate%20Application_20211124.pdf

15 IBM, Cost of a Data Breach Report 2023, July 2023: https://canada.newsroom.ibm.com/2023-IBM-Cost-of-a-Data-Breach-Report-Canadianbusinesses-are-being-hit-hard

that “there is increasing evidence that cyberattacks on utilities have been growing rapidly since 2018.”16

As a result, both the cyber and physical layers of existing systems could be affected by cybersecurity incidents, including but not limited to unauthorized interference with smart meters or other measurement devices, computer and telecommunication failures, attempts to gain unauthorized access to data, ransomware, or other destructive software. Although utilities can estimate the direct costs of cybersecurity concerns through a systematic approach including asset inventory, technology investments, and quantitative risk analysis, it is challenging to ensure that all indirect costs are quantified, e.g., loss of productivity, customer confidence, and investor trust.

Ultimately, it is estimated that revenue losses due to exposure to cyberattacks can be large for the energy sector. Depending on the scale of the company, the financial exposure of future utilities may result in, on average, up to 3.55% of their gross revenue being compromised, and up to 30.77% of estimated operating income.17 In 2022, the average cost of the most expensive email attack that surveyed energy utilities had experienced in the preceding 12 months was $1,316,000 (US dollars).18

• Grid capacity constraints and lack of a supportive policy environment foreclosing economic development opportunities: Failure to enact a supportive policy environment that encourages investment in grid expansion and capacity upgrades can constrain economic growth and development opportunities. Insufficient grid capacity may limit the ability to connect new businesses, industries, and residential developments, hindering economic prosperity and job creation.

The expansion of the electricity grid can contribute to economic development by meeting the growing

energy needs of businesses and industries, fostering innovation, attracting investments, and creating job opportunities. However, Ontario’s current approach has been to only build out the electricity system (largely focused on the bulk system) once the development project is firmly in place and commitments have been made. This approach is conservative and does not facilitate the practical realities of attracting economic growth. As building an electricity system may require significant time, industries will move to jurisdictions where the supply of power is reliable and readily available, where the connection process is quick and seamless, and, increasingly, where investors can achieve their ESG mandates (e.g., net-zero supply chains). This signals a need for a more proactive approach to capacity expansion, versus the current approach which could be considered a reactive one.

For example, the Windsor-Essex area is actively trying to attract new industry. However, transmission congestion in the area prevents connecting new generation, which in turn is needed to ensure adequate supply of electricity for the large new loads the region is seeking to attract. While the provincial government has taken steps to streamline approvals for a new transmission line, it will still be some years before the line is built. The IESO’s most recent Windsor-Essex Scoping Assessment Outcome Report specifically notes the role of economic development as a driver of electricity demand in the region. The provincial government also streamlined the process for two new transmission lines in northeastern Ontario to “support the production of clean steel [i.e., electric arc furnace] at Algoma Steel in Sault Ste. Marie, as well as economic growth, critical mineral development and new housing in northeast and eastern Ontario.”19 Further, the government has a plan to build 1.5 million new homes over the next 10 years,20 which will all need to be connected to LDCs’ systems.

16 International Energy Agency, Cybersecurity – is the power system lagging behind?, August 2023: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/cybersecurityis-the-power-system-lagging-behind

17 ThreatConnect, Risk quantification report: healthcare, manufacturing & utilities, 2023: https://threatconnect.com/resource/threatconnect-riskquantification-report-healthcare-manufacturing-utilities/

18 Barracuda, 2023 email security trends: the prevalence, impact, and cost of email-based cyberattacks on organizations around the world, February 2023: https://assets.barracuda.com/assets/docs/dms/2023-email-security-trends.pdf

19 Ontario, Province Powering Growth in Northeast and Eastern Ontario, October 23, 2023: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1003690/provincepowering-growth-in-northeast-and-eastern-ontario

20 Ontario, More Homes, Built Faster, October 2022: https://www.ontario.ca/page/more-homes-built-faster

Ontario’s economy is rapidly growing, with major investments such as Volkswagen in St. Thomas21 , Stellantis and LG Energy Solutions in Windsor22, and Umicore Rechargeable Battery Materials Canada Inc. in Loyalist Township.23 Collectively, these investments represent billions of dollars in economic development and thousands of new jobs. Further, the province is pursuing a strategy of Strategic Investment and Procurement Agreements24 with U.S. states to promote trade, investment, and economic development, resulting in the signing of economic cooperation Memoranda of Understanding with Indiana25 , Michigan26, and Nevada27 within the last twelve months.

That said, it is well documented that connection capacity challenges are thwarting the efforts of investors. For example, in Leamington, greenhouses have struggled to find a path forward given the length of time it takes to expand grid capacity. LDCs can be part of the solution through the delivery of local programs that can unlock grid capacity and alleviate the connection backlog. The IESO’s Local Conservation Initiatives, offered in conjunction with Ontario’s LDCs is an example of how LDCs can work together to remove connection barriers.

Further, some of Ontario’s largest trading partners in the United States have enacted policies to facilitate and implement the modernization of their electric grids. In 2020, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued Order No. 2222 to remove barriers to the participation of DERs in wholesale electricity markets, allowing DERs to provide energy to the market and

receive compensation.28 This order will have the effect of increasing the value of DERs in applicable markets and attracting capital investment, as well as requiring utilities to make the grid modernization investments necessary for successful implementation.

Ontario’s electricity system and LDCs need to keep pace with our biggest trading partners to stay competitive and attractive for capital investment and economic growth.

• Failure to achieve government emissions, electrification, and climate goals: Without proactive measures to modernize the grid and facilitate the integration of renewable energy sources, it may be challenging to meet emissions reduction targets, electrification, and climate resilience. Delayed action could impede progress towards a sustainable and lowcarbon energy future and, by extension, discourage investment by businesses seeking clean energy supply to meet their ESG mandates.

A recent report issued by the Government of Canada focusing on the perspectives of Ontario29 stated that “Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time. Rising atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases are altering the earth’s climate, driving increases in global average temperatures and variability and extremes of weather. These changes are causing unprecedented impacts, transforming ecosystem structure and function, damaging infrastructure, disrupting business operations, and imposing harm to human health and well-being. Physical climate impacts

21 Ontario Newsroom, Volkswagen’s New Electric Vehicle Battery Plant Will Create Thousands of New Jobs, April 21, 2023: https://news.ontario.ca/en/ release/1002955/volkswagens-new-electric-vehicle-battery-plant-will-create-thousands-of-new-jobs

22 Ontario Newsroom, Major Investments Secure Automotive Manufacturing Futures for Windsor and Brampton, May 2, 2022: https://news.ontario.ca/ en/release/1002141/major-investments-secure-automotive-manufacturing-futures-for-windsor-and-brampton

23 Ontario Newsroom, Governments of Canada and Ontario Finalize Agreement with Umicore Rechargeable Battery Materials Canada Inc. for New Plant in Loyalist Township, October 16, 2023: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1003655/governments-of-canada-and-ontario-finalize-agreementwith-umicore-rechargeable-battery-materials-canada-inc-for-new-plant-in-loyalist-township

24 Ontario, Ontario Moves Forward with New Strategy for U.S. Trade, February 7, 2020: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/55696/ontario-movesforward-with-new-strategy-for-us-trade

25 Ontario, Ontario and Indiana Sign Agreement to Boost Trade and Investment, January 23, 2024: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1004095/ontarioand-indiana-sign-agreement-to-boost-trade-and-investment

26 Ontario, Ontario and Michigan Strengthen Economic Ties, July 25, 2023: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1003318/ontario-and-michiganstrengthen-economic-ties

27 Ontario, Ontario and Nevade Strengthen Economic Ties, September 27, 2023: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1003556/ontario-and-nevadastrengthen-economic-ties

28 FERC, FERC Order No. 2222 Explainer: Facilitating Participation in Electricity Markets by Distributed Energy Resources, July 2023: https://www.ferc. gov/ferc-order-no-2222-explainer-facilitating-participation-electricity-markets-distributed-energy

29 Douglas, A.G. and Pearson, D. Ontario; Chapter 4 in Canada in a Changing Climate: Regional Perspectives Report, (ed.) F.J. Warren, N. Lulham, D.L. Dupuis and D.S. Lemmen; Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, 2022

3. THE NEED FOR ACTION

and risks to human, natural and built systems in Ontario are driven by average annual warming temperature and extreme heat, drought, changes to intensity and frequency of precipitation and other climate variables. Avoiding or reducing the worst impacts of humaninduced climate change requires action on parallel fronts: rapid and deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and proactive and planned measures to adapt to current and imminent future changes. While there are adaptation efforts underway to address these impacts, the rapid pace of climate change requires large-scale, accelerated action in all facets of our society and economy.”

One of the primary motivations behind electrification and DER integration is the desire to reduce carbon emissions and costs. However, this presents a significant challenge for LDCs as they must enhance their operations significantly to reliably manage a more complex grid. Without adequate grid modernization, LDCs may struggle to integrate DERs beyond a certain threshold, thereby limiting the extent of electrification and carbon reduction achievable.

In Ontario, for example, consider the benefits of an LDC modernizing its system to facilitate customer uptake of EVs. Estimates indicate that the average driver in the province can save between $1,500-$2,500 per year on fuel and maintenance costs compared to a fossil fuel car.30 Also, recent studies have reported on the health benefits of electric vehicles on air quality. For example, researchers at the University of Toronto modelled the impact of converting all cars and SUVs in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) into EVs, predicting that it would result in 313 fewer deaths per year with an estimated social benefit of $2.4 billion.31 More generally, failure to reduce emissions

will result in billions of dollars in healthcare costs for Ontario associated with climate impacts of heat-related productivity losses, heat-related deaths and groundlevel ozone-related illnesses and deaths.32

• Further, as noted above, several of Ontario’s largest trading partners in the United States have enacted policies to facilitate and implement the modernization of their electric grids. In many instances, these policies are part of broader government initiatives related to reducing emissions and achieving a net-zero economy. This further underscores the need for Ontario to keep pace with our biggest trading partners to stay competitive and attractive for capital investment and economic growth.

• Customer expectations and satisfaction with electricity service not met: Inadequate investment in grid modernization may result in subpar electricity service quality and reliability, failing to meet the expectations and satisfaction of customers. Outdated infrastructure may lead to increased downtime, slower response times to outages, and limited access to innovative services, diminishing overall customer experience.

We acknowledge Ontario’s LDCs are ready to lead the advancement of the clean energy economy by championing customer electrification and the widespread adoption of clean energy solutions. With their readiness to navigate the challenges of a dynamic and multifaceted electricity system, LDCs will continue to be at the forefront of innovation and progress. As the next section of this report outlines, LDC investments in distribution system infrastructure and enabling technologies in the near term are required to support a cost-effective and reliable energy transition.

30 Ontario, Low carbon vehicles and electric vehicles, October 2023: https://www.ontario.ca/page/low-carbon-vehicles-and-electric-vehicles

31 University of Toronto, U of T researchers model the health benefits of electric cars, find ‘large improvement in air quality’, June 8, 2020: https://www. utoronto.ca/news/u-t-researchers-model-health-benefits-electric-cars-find-large-improvement-air-quality

32 Climate Institute for Climate Choices, The Health Cost of Climate Change, June 2021: https://climatechoices.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ ClimateChoices_Health-report_Final_June2021.pdf

4. INVESTMENTS TO ENABLE THE ENERGY TRANSITION

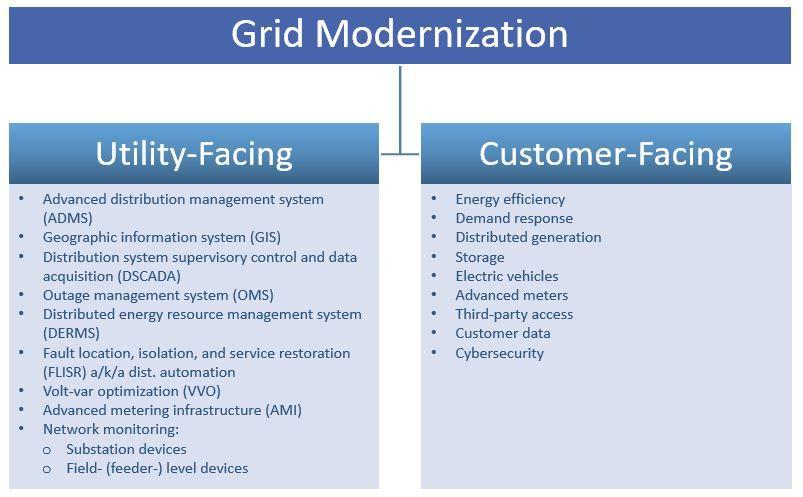

Many investments are required to expand the distribution system and enable LDCs to meet objectives related to the energy transition, customer choice, resilience to climate change, and delivering affordable, reliable, and safe electric service. The analysis in this paper focuses largely on investments made in the distribution system. These utility-facing investments are required to enable customer-driven investments (i.e., behind-the-meter), such as allowing for two-way flows and enabling the connection and operations of DERs.

Distribution Grid Expansion Investment Requirements

Increasing electricity demands will require LDCs to update their investment plans to increase the capacity of distribution system infrastructure. After years of steady or declining demand, Ontario is now entering a period of growth driven by population and housing expansion, with 1.5 million new housing starts required by the government by 2031, an increase in energy-intensive industries, and electrification. Additional grid capacity is also required to enable wide-scale electrification of the economy under a net-zero scenario. For example, the IESO’s Pathways

to Decarbonization (P2D) report shows the impact of rapid electrification of transportation and space heating required for a net-zero economy by 2050.33 The report noted that a decarbonized electricity sector by 2050 would require “a system more than double the size it is today at an estimated cost of around $400 billion.”34

That said, the P2D report focuses only on bulk system impacts, and explicitly states that it “does not consider the impact on local distribution systems.”35 As a result, it does not consider investment costs required for distribution grid expansion to connect and accommodate new load. To prepare for increasing peak demand, LDCs must invest more in new infrastructure and ongoing renewal of existing infrastructure.

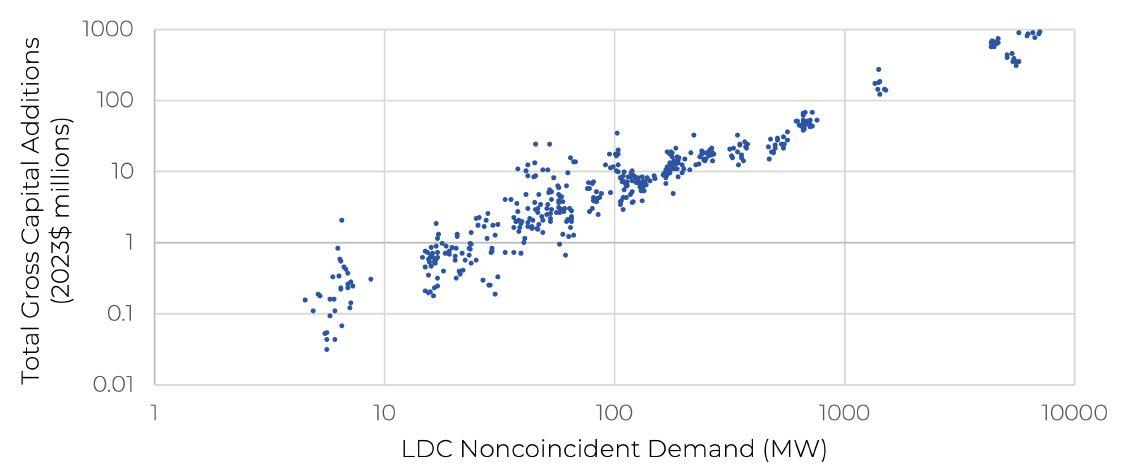

Figure 5 presents an estimate of gross capital investment by Ontario’s LDCs using the demand forecasts based on the IESO’s P2D Report (“Net-Zero Scenario”) and the IESO’s 2024 APO (“Reference Scenario”). While both scenarios assume electrification, the IESO’s P2D report projects significant uptake in air and ground source heat pumps and EVs, driving demand growth, particularly in the winter season. There is a consistent historical relationship

33 IESO, Pathways to Decarbonization, December 2022, https://www.ieso.ca/-/media/Files/IESO/Document-Library/gas-phase-out/Pathways-toDecarbonization.pdf

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

Figure 5. Gross Annual Capital Additions by Ontario LDCs, Historical and Forecast

between LDC peak demand and capital investment,36 as published by the OEB, 37 which can be used to estimate future distribution costs. See Appendix C for the methodology and scenario assumptions.

In both the Net-Zero Scenario and Reference Scenario, investment needs to increase from current levels to manage demand growth. The results show that the annual gross capital additions by all Ontario LDCs could double under the Net-Zero Scenario from current levels by the mid-2040s and increase by approximately 130% from current levels by 2050. Even under the Reference Scenario, with more moderate electrification assumptions, annual gross capital additions by all Ontario LDCs could increase by nearly 45% by 2050. Cumulatively, Ontario’s LDCs are projected to spend approximately $103 billion on gross capital additions from 2024 to 2050 (Reference Scenario) and could spend up to $120 billion on gross capital additions from 2024 to 2050 under a Net-Zero Scenario.

Distribution Grid Modernization and Enhancements

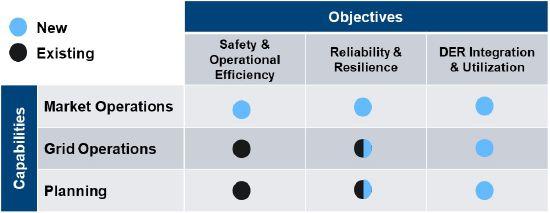

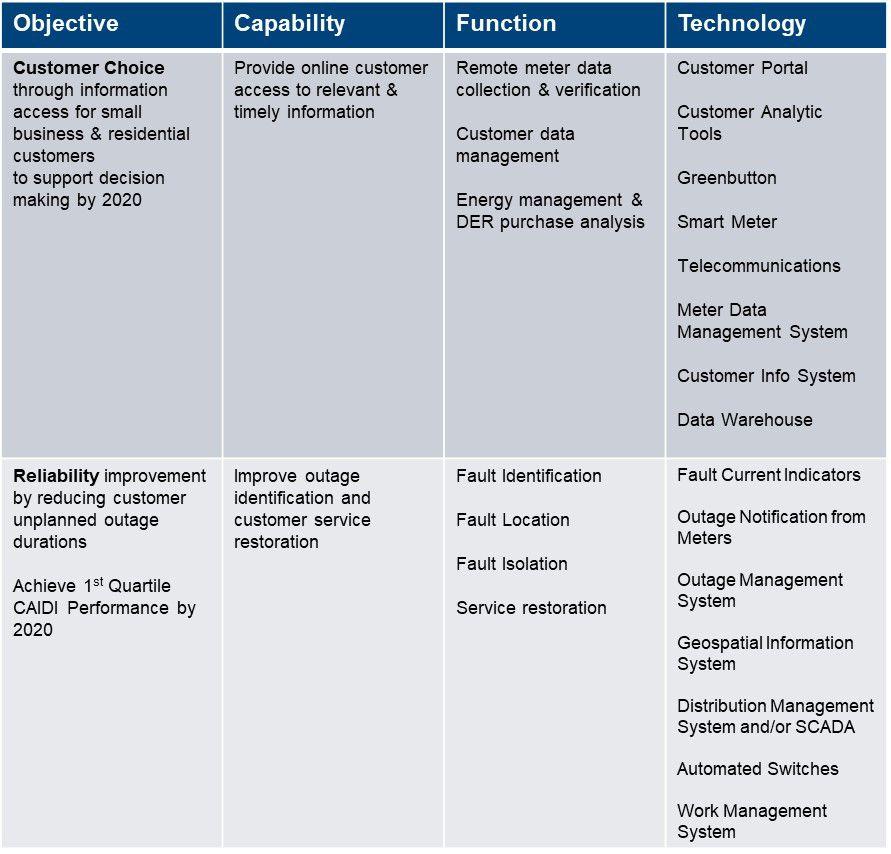

Grid modernization is not an end unto itself. As depicted in Figure 6, LDC investments in grid enhancement are guided by the objectives of the LDC and the evolving conditions on the grid to which the LDC must respond. Technology can augment an LDC’s capabilities and enable it to offer new or improved services to customers.

The distribution system is designed to deliver electricity on demand and maintain a reliable last-mile supply. Future enhancements should prioritize meeting this objective amidst deep electrification and increased DER integration. Today and in the future, various metrics can measure progress toward this goal, including cost-ofservice, reliability, resilience, and carbon emissions per unit of energy. For instance, LDCs often report SAIFI (System Average Interruption Frequency Index) and SAIDI (System Average Interruption Duration Index) metrics to gauge the frequency and duration of outages. Grid modernization efforts should align with this objective of providing reliable and affordable power, adhering to established standards for services.

LDCs are motivated to consider the development of grid modernization plans for a variety of reasons. As shown in Figure 7, the main drivers are meeting customer and stakeholder expectations, responding to a changing climate, enabling clean energy goals of customers and governments, responding to technological advancement, and social equity considerations. Grid modernization enables LDCs to respond to a range of customer preferences that are rooted in enabling the energy transition. It can also be driven in response to the realities of a changing climate and the need to focus on climate resilience as Ontario is confronted with more extreme weather. LDCs need to be prepared to adopt new or emerging technologies to safeguard aging infrastructure and integrate DERs that may be providing benefits to the local grid, customers, or bulk system. Grid modernization plans also enhance social equity, particularly through program designs that benefit customers who might be disproportionally burdened by the costs of the energy transition, by promoting fair and inclusive access to new services and opportunities and fostering community empowerment.

The main technologies that work together to enable new LDC functions are illustrated in Figure 8 Sensing and monitoring technologies offer the LDC real-time data on

36 Gross capital expenditures by LDCs include: System Access investments such as customer connections, modifications, or system modifications for infrastructure development; System Renewal investments such as distribution asset replacements and refurbishments; System Service investments which enhance system capacity, safety, and reliability; and General Plant investments such as land, vehicles, and computer hardware and software.

37 Ontario Energy Board, Natural Gas and Electricity Utility Yearbooks: https://www.oeb.ca/ontarios-energy-sector/performance-assessment/naturalgas-and-electricity-utility-yearbooks#elec

Drivers for Grid Enhancements

Enhanced LDC Capabilities Enabled Services

Figure 6. Framework for Grid Enhancement Needs

Drivers for Grid Enhancements

Sensors and Monitoring

• AMI

• Grid Sensors

• Advanced SCADA

• Modernized Protection Relays

Customer & Stakeholder Expectations

Changing Climate

• Service Reliability

• Economic Development

• Electrification

• Affordability

• Customer Choice

• Climate Resilience

• Emissions Reduction Plans

Clean Energy Goals

Technological Advancement

Social Equity

• Renewable Energy Integration

• Storage Integration

• Energy Efficiency

• Safety

• DER Integration

• Cybersecurity

• Social Acceptance

• Enabling Energy Transition

Technology Enablers

Information Technology

• Advanced Communication Networks

• Edge and Cloud Computing

• GIS

• EMS

• DERMS

• Cybersecurity Solutions

• Artificial Intelligence

Operational Technology

• Power Electronics

• Smart Inverters

• Remote-Controlled Switches

• Remote Terminal Units

• DMS

• ADMS

• Generation

• Energy Storage

• EVs

Figure 7. Drivers for Grid Enhancements

Figure 8. Technology Enablers

grid conditions. Information Technology (IT) processes and analyzes data gathered by sensors and monitoring technologies, encompassing digital infrastructure, communication systems, and software applications. Operational Technology (OT) translates insights into actionable steps for LDCs, concentrating on the physical devices and control systems that actively oversee and manage the grid’s operational processes, including DERs. The technologies chosen by LDCs should be considered in the context of the goals they are trying to achieve and the specific conditions they are responding to within their service territory (e.g., number of EV and DER connection requests, etc.).

A description of how foundational technologies enable LDCs to provide services to customers and the grid is provided in Appendix E. Additional case studies of grid modernization plans and frameworks are provided in Appendix F

The enhanced functionalities of the LDC that are enabled by technological investments are illustrated in Figure 9 and include the ability of the LDC to contribute to the overall efficiency, reliability, and adaptability of the system. There is some overlap among these functionalities, which highlights that improvements in one area often have positive effects on others. For example, grid visualization and analytics – components of system visibility – are essential for supporting initiatives within system flexibility.

• Non-Wires Alternatives

• Voltage Optimization

• Proactive Maintenance

• Integrated Planning

• System and DER Models

• Load and DER Forecasting

• Situational Awareness

• Data Visualization

• Hosting Capacity Maps

• Real-Time Reporting

• System Automation

• Load Management

• DER-Enhanced Operation

• Dynamic Resource Allocation

• Virtualization

Moreover, automated devices can dynamically adjust grid operations, reroute power, or isolate faulty components to minimize downtime and enhance both system availability and flexibility. Other investments, such as NWAs, can reduce the need for expansion of existing infrastructure (e.g., managed EV charging can mitigate the need to upgrade existing equipment).

With enhanced functionalities, LDCs are enabled to offer new services and supports that have value to customers and the broader electricity grid, as shown in Figure 10 This includes the ability to provide customized insights and tools to help customers manage their usage, or options to participate in new electricity rate designs. In addition, LDCs can leverage the new investments to offer demandside management services which could reduce customer costs, including serving as NWAs.

An illustrative grid investment roadmap is provided below for explanatory purposes, demonstrating how an LDC may plan to deploy new technologies and enabled services.

The figure outlines a roadmap for LDCs to embrace technological advancement and enhance operational efficiency for the next 10 years. The timeline ends in 2035 to highlight the alignment between LDC initiatives and the broader national objectives for the decarbonization of the electricity sector. Activities are categorized into three key areas: system adequacy, core planning and operation, and markets and customer platforms, reflecting the

Figure 9. LDC Functionalities Enhanced by Technology Adoption

Customer Engagement

Enabled Services

Demand-Side Management

Customer Support

modernization of existing systems and the adaptation to emerging trends.