EVALUATING WIND POWER

Providing an overview of wind energy performance using IESO data. P.28

INSIDE

+ Product certification for hazardous locations

+ Lighting case study: New York City’s Kleinfeld Bridal

+ Increasing motor reliability

Providing an overview of wind energy performance using IESO data. P.28

+ Product certification for hazardous locations

+ Lighting case study: New York City’s Kleinfeld Bridal

+ Increasing motor reliability

Climate change has been on my mind lately. When my mind turns to climate change, I inevitably begin to wonder whether alternative energy can save the day (speaking of, don’t forget to check out Greg Young’s article analyzing wind power in Ontario on page 28!).

Amid the focus on alternative energies lately, I was shocked to hear about the cancellation of the Nation Rise Wind Farm project in North Stormont, Ont. It seems like what we need right now are more sources of alternative energy, not fewer, and a 29-turbine wind farm seems like a great place to start!

When I visited ABB’s Dalmine factory in November, I spoke with Oliver Iltisberger, ABB’s global managing director of smart buildings, about ABB’s ultra-fast EV chargers, which have already started rolling out to select cities in the United States, Australia and across Europe. In part, this deployment is because electric delivery vehicles and other vehicles that travel long distances have been slow to adapt to the electric revolution.

“It’s easy to have electric cars available today that can drive around the city. Every EV can do that these days. Where the technology is not yet good enough is during a long-distance drive,” said Iltisberger.

While standard EV chargers take anywhere from 14 to 18 hours to charge a car to full, ultra-fast chargers can deliver up to 150kV, providing a full charge in about 15 minutes. That’s barely longer than it takes to pump gas!

Electrify Canada has also started rolling out ultra-fast charging stations in Ontario (currently located in Markham, Mississauga and Niagara Falls). Several more are set for large cities in Ontario and Quebec, and along highway 401.

“In order to allow people to use EVs not just in cities, fast charging infrastructure needs to be put in place and that’s why countries are investing into it, especially along highway corridors,” added Iltisberger. “I think more investments are required in order to have people feel more comfortable that they can get from point A to B without getting stranded somewhere.”

As for me, I mostly use public transit now, but if the time comes that I decide to get a car, I’m pretty sure I’ll be going electric.

An upgrade at New York’s Kleinfeld Bridal shows how the right lighting can open wallets.

Incorrect maintenance or modification of certified products can defeat the equipment protection.

Not your average CEO: Rene Gatien

A Q&A with the president and CEO of Waterloo North Hydro.

Industry reaction shows unprecedented unity against Ontario’s plan to create portable trades.

How Remote Waste found the right trace heating cables to keep the pipes running year-round.

Regularly checking a motor’s operating temperature can help prevent shutdowns.

Analyzing wind power performance in Ontario and what it means for clean energy production.

“What we wanted to do, ultimately, is to work with them on putting together a system that we can all look back on 20 years from now, and say, ‘we got that right.’ We want a system that’s going to stand the test of time, that’s going to be flexible enough that economic cycles won’t impact it, that is adaptable enough to work around new technologies that arise, while at the same time, still ensuring that Ontario produces the highest skilled and safest electricians,” added Aitken.

While the industry is still waiting to see what the government plans to do, there have been strong signals they are listening, particularly from Monte McNaughton, Minister of Labour, Training and Skills Development, who has been reaching out to a broad range of skilled trades representatives.

Electrical work is complex and dangerous, which is why we needed them to understand that we must maintain high standards for training.

“He is the first Minister I have worked with in decades to show such an interest in learning about the trades and is really doing what is right for the province. Without a doubt, his initial response has been positive, but we still have a lot of work to be done to get this right,” said Barry.

“I believe there are members of government who were impressed that we took a collaborative approach, that we went to them with a unified voice and we came armed with facts. Specifically, Minister McNaughton was very quick to react. He appears to be taking our advice seriously and truly trying to learn more about skilled trades so he can make an informed decision,” added Sherri Haigh, director of marketing and new business development for the Joint Electrical Promotion Plan.

Aitken agreed, noting there appears to be a strong indication that government is listening and wants to work with the industry. “I think shifting over the skills portion to the Ministry of Labour was a huge signal that there’s an understanding that we can’t lump all education under the same umbrella,” he said. “There’s something different about construction education. It also appears that the examination of going towards a skill set model and looking at skill sets that are common across trades has been abandoned. And that is also a strong and encouraging indicator that there’s an understanding of what is required.”

Barry added that Minister McNaughton also recently announced plans to reinstate a construction advisory council in an effort to get input from key players in the industry. “The test will be when there is actually some solid confirmation that they’re going to maintain the scope of practice and uphold the Red Seal. We’re still waiting for that,” said Barry.

“Sometimes work slows down a little bit and we want to be certain that those people can travel across the country, so that makes the Red Seal extremely important,” added Aitken. “If you’re not demanding that people get Red Seal, then arguably, you’re creating a lesser electrician in the province of Ontario, compared to the rest of the country.”

While the government continues to review the Skills and Safety Matter report, Barry and Aitken are busy building on that momentum with another report on what a proper regulatory framework could look like.

“I believe our role is more than just educating; we also need to help with the solutions. We are the ones who work in

the trade and it should be on us to help government create a system that works for everyone,” said Barry.

According to Aitken, ECAO’s most pressing concern is maintaining the integrity of the electrical trade. “There is an overall safety issue: people that don’t understand the entirety of an electrical system shouldn’t be installing any parts of that system. If unskilled, unknowledgeable persons are installing portions of electrical systems, our members would be in a dangerous position following up on such unskilled installations; whether completing the installation, repairing/replacing the work, or adding to the system.”

He also noted that his contractors are often put in the position of competing with companies that are using unskilled individuals to complete electrical work, which can be quite difficult because unlicensed workers haven’t paid for training or licensing, and therefore, tend to charge clients less.

When a new model is finally created, Barry says it will be important that it includes a system to deal with compliance of the rules. “There has to be qualified inspectors going to worksites to address the underground economy and ensure qualified people are doing the electrical work. Otherwise, you can have all the legislation you want, but it won’t mean anything. The public and workers will be at risk.”

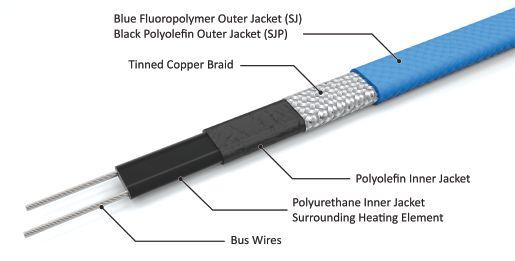

Remote Waste’s quest for rugged trace heating cables to keep the pipes running year-round / BY

ALAN WAGNER

Life in Canada requires heat tracing solutions that can operate in the most demanding environments.

The oil and gas sectors are particularly challenged as these facilities are often located in remote northern regions and require pipe and hose freeze protection in order to ensure fluids remain flowing year-round.

Water is an important part of the refining process for oil and gas. Wastewater created by these plants needs to be treated to prevent scaling, corrosion and souring prior to being released back into the environment. In fact, industry water quality and usability are directly impacted by wastewater’s microbial composition and has profound impacts on well production, quality and longevity in the oil and gas sector.

Remote Waste is a leader in wastewater, produced water and fracturing water treatment in Canada and the United States by utilizing premier technology and experienced personnel to supply, operate and maintain a mobile fleet of chlorine dioxide generators and wastewater treatment plants.

How does wastewater treatment work?

Wastewater treatment removes as much of the suspended solids from water before being discharged back into the environment. It is an essential service provided by the Remote Group of Companies, who are constantly pushing the boundaries of wastewater and potable water treatment in remote locations throughout North America.

Remote Waste uses proven water treatment and solids removal processes that allows for cost-effective cleaning of water, eliminating the need for disposal.

Using their specialized delivery system, Remote Waste offers reliable and safe treatment of any volume of water while maintaining a small footprint, which is important in remote locations. The success of these water services relies on the use of electric trace heating to keep fluids flowing during water treatment.

The water treatment process pushes wastewater and potable water that needs to be cleaned through a series of hoses

Hoses are transported onsite, moved where needed and must be operational in all temperatures and the harshest conditions.

and pipes. These hoses are transported onsite, moved where needed and must remain operational in all temperatures.

“We needed to install heat tracing cables that offer long service life and reliable performance, especially on plastic piping and tanks where freeze protection is so important,” said Scott Gaylard, president of the Remote Group of Companies. “Any down time can cost our operations – big time.”

Remote Waste’s guarantee to their customers is that their onsite wastewater treatment solution will perform under the harshest of conditions when things need to “just work”. They supply wastewater treatment to a diverse mix of industries, including: oil and gas, construction, forestry, mining and small-scale municipal applications.

When choosing a trace heating cable solution for wastewater applications, Remote Waste needed to ensure cables were certified to UL, CSA (CUS) and UL/ULC standards for use throughout North America and were suitable for both metal and non-metal pipes, tanks and vessels.

The trace heating cables they use should be designed to perform in the most demanding environments, including those where exposure to hydrocarbons or corrosives is a possibility for freeze protection of metallic and non-metallic piping.

The cables must also be rugged in order to withstand being constantly moved, loaded and unloaded from trucks for use in the field. The team at Remote Waste couldn’t afford to have their trace heating cables fail.

In the end, Remote Waste selected a vendor whose two solutions were able to serve in demanding environments, including hazardous and non-hazardous areas, as well as areas where corrosive exposure may be of concern.

One of those products is designed to perform, even in corrosive environments, while the second is a self-regulating heating cable suitable for freeze protection of metallic and non-metallic piping in aqueous/non-corrosive environments. Selecting the right tools for the job is a big part of how Remote Waste delivers their water treatment solutions in the field. With decades of combined experience, they can provide safe, reliable treatment options for tanks, pits, disposal sites or sour fluid on the fly. Without the use of electric trace heating cables, their cutting-edge technologies simply couldn’t successfully operate in the field to provide the water systems maintenance techniques and operations that Remote Waste is known for.

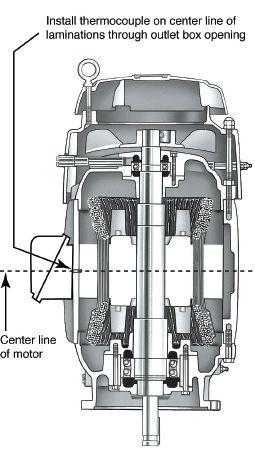

Regularly checking the operating temperature of critical motors will help extend their life and prevent costly, unexpected shutdowns / BY

THOMAS H. BISHOP, P.E.

It’s a striking fact that operating a three-phase induction motor at just 10°C above its rated temperature can shorten its life by half. Whether your facility has thousands of motors or just a few, regularly checking the operating temperature of critical motors will help extend their life and prevent costly, unexpected shutdowns. Here’s how to go about it.

First, determine the motor’s insulation class (A, B, F or H) from its original nameplate or the ratings for three-phase induction motors in the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) standard Motors and Generators, MG 1-2016 (hereafter MG1). The insulation class indicates the maximum temperature that the motor’s winding can withstand without degrading (see Table 1).

That sounds simple enough. To protect the motor, just keep its winding temperature below its insulation class rating. But there’s a little more to it.

The largest component of the winding temperature is heat from motor operation (called temperature rise), which is load-dependent.The rest is attributable to the ambient (room) temperature. Identifying both components of the winding temperature makes it possible to protect the motor winding under different operating conditions (e.g., a lower ambient temperature may permit a higher temperature rise). NEMA also incorporates a safety factor, but more on that later.

As with insulation class, every motor built to NEMA standards will have an ambient temperature rating (normally 40°C for three-phase motors). This is the maximum temperature for the air (or other cooling medium) surrounding the motor. Like the insulation class rating, you can find this rating on the motor nameplate or in MG1.

The next step is to measure the overall (“hot”) temperature of the winding with the motor operating at full load, either directly using embedded sensors or an infrared temperature detector, or indirectly using the resistance method explained below. The difference between the winding temperature and the ambient temperature is the temperature rise. Put another way, the sum of the ambient temperature and the temperature rise equals the overall (or “hot”) temperature of the motor winding or a component.

Ambient temperature + Temperature rise = Hot temperature

Figure 1. Hot spot temperature versus ambient and rise for Class B insulation system. Note that at 40°C ambient (horizontal axis), the rise is 90°C (vertical axis). The sum of the ambient and temperature rise will always be 130°C for a Class B insulation system.]

To avoid degrading the motor’s insulation system, the hot temperature must not exceed the motor’s insulation class temperature rating.

Given that MG1’s maximum ambient temperature is normally 40°C, you would expect the temperature rise limit for a Class B 130°C insulation system to be 90°C (130° - 40°C), not 80°C as shown in Tables 2 and 3. But as mentioned earlier, MG1 also includes a safety factor, primarily to account for parts of the motor winding that may be hotter than where the temperature is measured, or that may not be reflected in the “average” temperature obtained by the resistance method.

Table 2 shows the temperature rise limits for MG1 medium electric motors, based on a maximum ambient of 40°C. In the most common speed ratings, the MG1 designation of medium motors includes ratings of 1.5 to 500 hp for 2- and 4-pole machines, and up to 350 hp for 6-pole machines.

Temperature rise limits for large motors–i.e., those above medium motor ratings–differ based on the service factor (SF). Table 3 lists the temperature rise for motors with a 1.0 SF; Table 4 applies to motors with 1.15 SF.

of

The resistance method is useful for determining the temperature rise of motors that do not have embedded detectors–e.g., thermocouples or resistance temperature detectors (RTDs). Note that temperature rise limits for

medium motors in Table 2 are based on resistance. The temperature rise of large motors can be measured by the resistance method or by detectors embedded in the windings, as shown in Tables 3 and 4.

To find the temperature rise using the resistance method, first measure and record the lead-to-lead resistance of the line leads with the motor “cold”–i.e., at ambient temperature. To ensure accuracy, use a milli-ohmmeter for resistance values of less than 5 ohms, and be sure to record the ambient temperature. Operate the motor at rated load until the temperature stabilizes (possibly up to 8 hours) and then de-energize it. After safely locking out the motor, measure the “hot” lead-to-lead resistance as described above.

Find the hot temperature by inserting the cold and hot resistance measurements into Equation 1. Then subtract the ambient temperature from the hot temperature to obtain the temperature rise.

Equation 1. Hot winding temperature

Th = [ (Rh/Rc) x (K + Tc) ] - K

Where:

Th = hot temperature

Tc = cold temperature

Rh = hot resistance

Rc = cold resistance

K = 234.5 (a constant for copper)

Example. To calculate the hot winding temperature for an un-encapsulated, open drip-proof medium motor with a Class F winding, 1.0 SF, lead-to-lead resistance of 1.21 ohms at an ambient temperature of 20°C, and hot resistance of 1.71 ohms, proceed as follows:

Th = [ (1.71/1.21) x (234.5 + 20) ] - 234.5 = 125.2°C (round to 125°C)

The temperature rise equals the hot winding temperature minus the ambient temperature, or in this case: Temp. rise = 125°C - 20°C = 105°C

As Table 2 shows, the calculated temperature rise of 105°C in this example equals the limit for a Class F insulation system. Although that is acceptable, it is important to note that any increase in load would result in above-rated temperature rise and seriously degrade the motor’s insulation system. Further, if the ambient temperature at the motor installation were to rise above 20°C, the motor load would have to be reduced to avoid exceeding the machine’s total temperature (hot winding) capability.

Determining temperature rise using detectors Motors with temperature detectors embedded in the windings are usually monitored directly with appropriate instrumentation. Typically, the motor control centre has

TABLE 2. Temperature rise by resistance method for medium induction motors based on a maximum ambient of 40°C

Figure 2. It may be possible to determine the approximate temperature of the winding with a thermocouple.

panel meters that indicate the hot winding temperature at the sensor. If the panel meters were to read 125°C as in the example above, the same concerns about the overall temperature would apply.

What if you want to directly measure the operating temperature of a motor winding that does not have embedded detectors? For motors rated 600 volts or less, it may be possible to open the terminal box (following all applicable safety rules) with the motor de-energized and access the outside diameter of the stator core iron laminations with a thermocouple (see Figure 2). The stator lamination temperature will not be the same as winding temperature, but it will be nearer to it than the temperature of any other readily accessible part of the motor.

If the stator lamination temperature minus the ambient exceeds the rated temperature rise, it’s reasonable to assume the winding is also operating beyond its rated temperature.

The critical limit for the winding is the overall or hot temperature. The load largely determines the temperature rise because the winding current increases with load. A large percentage of motor losses and heating (typically 35 - 40%) is due to the winding I2R losses. The “I” in I2R is winding current (amps), and the “R” is winding resistance (ohms). Thus the winding losses increase at a rate that varies as the square of the winding current.

If the ambient temperature exceeds the usual MG1 limit of 40°C, you must de-rate the motor to keep its total temperature within the overall or hot winding limit. To do so, reduce the temperature rise limit by the amount that the ambient exceeds 40°C.

For instance, if the ambient is 48°C and the temperature rise limit in Table 2 is 105°C, decrease the temperature rise limit by 8°C (48°C - 40°C ambient difference) to 97°C. This limits the total temperature to the same amount in both cases: 105°C plus 40°C equals 145°C, as does 97°C plus 48°C.

Regardless of the method used to detect winding temperature, the total, or hot spot, temperature is the real limit; and the lower it is, the better. Each 10°C increase in operating temperature shortens motor life by about half, so check your motors under load regularly. Don’t let excessive heat kill your motors before their time.

Thomas Bishop is a senior technical support specialist at EASA, St. Louis, MO; 314-993-2220; 314-993-1269 (fax); www.easa.com. EASA is an international trade association of over 1800 electromechanical sales, service and repair firms in nearly 80 countries.

BY RAY YOUSEF, CODE ENGINEER

Ontario’s Electrical Safety Authority esasafe.com

IF YOU DARE!

Answers to this month’s questions will appear in the April issue of Electrical Business

QUESTION 1

A totally enclosed non-ventilated Class B motor requires conductors rated at 38 A. The minimum size copper multi-conductor cable can be used is:

a) No. 10 AWG TECK90

b) No. 8 AWG TECK90

c) No. 8 AWG TW75

d) No. 6 AWG TW75

QUESTION 2

A disconnect for luminaires with double ended lamps operating at 120 volts is required for:

a) Luminaires with a ballast

b) Luminaires with a ballast and LED lamps

c) Luminaires with a driver and LED lamps

d) All of the above

e) None of the above

QUESTION 3

For a single dwelling unit with 100 A breaker using No. 3 AWG Copper service conductors, is the marking required based on Rule 4-004 22) and Table 39?

a) Yes b) No

ANSWERS Electrical Business, December 2019

Question 1

A combination Arc Fault Circuit Interrupter provides:

d) Protections for both series and parallel arcing faults.

Ref. Rule 26-650, CE Code 2018.

Question 2

The integrity of an impedance grounded system shall be monitored, and the system shall have an audible or visual alarm if there is:

d) All of the above. Ref. Rule 10-302, CE Code 2018.

Question 3

Raceways which are less than 2 m above grade and subject to mechanical damage shall: d) Any of the above. Ref. Rule 12-934, CE Code 2018.

How did YOU do?

3 • Seasoned journeyman 2 •Need refresher training 1 • Apprentice 0 • Just here for fun!

Analyzing actual wind power performance in Ontario and what it means for clean energy production / BY GREG YOUNG

Wind power in Ontario has been in the news lately, especially with the recent cancellation of a project in Prince Edward County projected to cost taxpayers $231M in cancellation fees. While this case has an obvious financial impact, it also doesn’t fit modern day environmental trends that include investing in clean energy, not cancelling it.

By downloading and analyzing public IESO data, it is possible to evaluate how wind power technology is performing in Ontario. The goal of this article is to provide insight into actual wind power performance in the province, including amount of installed wind power, energy production, seasonal characteristics of wind and inconsistencies in wind energy output.

Wind turbines capture energy from the wind through their rotating blades, which then turn a generator to produce electricity. The finer detail of wind power is understanding the amount of power available to capture from the wind. These details are reviewed below.

Wind Speed has a “cubic relationship” with wind power. For example, if wind speed increases by a factor of 2, the amount of power available in the wind increases by 8! (2, cubed). Rotor Area is the circular area the blades cover while they are rotating. This is another fairly intuitive variable, as the larger the wind turbine, the more power it can generate. Rotor area has a 1-1 relationship with power. If the blade area doubles, power available doubles - no fancy exponents here. Air Density might not be as intuitive. Just like blade area, air density has a 1-1 relationship with wind power. To keep things simple, we just need to know that air is denser in cold weather (more power available), and less dense in warm weather (less power available).

To summarize, wind speed is definitely the most important variable. The second most important is likely rotor area since it can be controlled by the design engineers. Lastly, we have air density, which is location/weather specific.

Wind farms are fairly scattered across Ontario, with a large concentration located in Southern Ontario.

From an analysis standpoint, location is key for analyzing wind speed, but wind patterns are fairly consistent across Ontario.

The amount of wind power installed in the province is evaluated using two metrics: capacity (or nominal power rating of the wind turbine) and energy output. Power is an instantaneous measurement of electricity supplied to the grid, and energy has a time component, meaning for how many hours was a specific amount of power supplied. Electrical power is often measured using Watts (W), while energy is measured using Watt-hour (Wh) (energy = power x time).

The IESO provides wind power data on the transmission (high voltage) side of the grid before a local utility gets involved. A breakdown of the province’s generation types and performance numbers can be found at tiny.cc/lzq3iz.

This example shows that wind is 12% of our installed capacity, yet only produces 7% of the province’s electrical energy. Alternatively, we see that nuclear is 35% capacity, yet dominates on the energy end at 61%. The reason for the capacity and energy difference is the time aspect of energy. Nuclear plants rarely shut down, so they are running 24/7. Wind power is subject to wind speed, which is inconsistent.

Now we will look at actual energy output in each month of 2018 to start gauging how wind power is performing in Ontario. The monthly data from the IESO is plotted below.

Credit: Greg Young

As you can see, there is a clear pattern with higher production in the “winter” months and much less production in the “summer” months. Of the three major variables discussed previously that affect wind power, the two that are weather/ location related are wind speed and air density.

The first claim we can make to describe this energy pattern is the higher air density in the winter months due to the lower temperatures, allowing for more energy to be captured.

The larger factor in this case is seasonal wind speed patterns. IESO’s example of annual wind speed averages in London, Ont., an area located near many turbines (southwest Ontario).

This example shows that wind speeds in Ontario are typically higher in winter months compared to summer months, matching the same pattern in the energy output chart. Note that this similar wind pattern was seen in Toronto, Hamilton, and Windsor areas (other city data was not available from my source, but it is assumed this pattern is consistent across the province where the major wind farms are located).

A seasonal performance analysis can be done by understanding average seasonal monthly energy production and comparing the energy output to a maximum theoretical scenario. This max scenario is developed by taking the province’s installed capacity and multiplying it by the total amount of available hours over the defined seasonal time periods.

According to IESO data, graphed on tiny.cc/lzq3iz, wind energy output is nearly double in winter than summer (Winter: 1.11 TWh/mth | Summer: 0.58 TWh/mth).

Looking at the percentages, we can see that wind power in the wintertime generates 34% of the max theoretical amount it could produce, while summer lags behind at only 18%.

A clear theme is developing that during summertime, when Ontario’s demand for electricity is rising due to the increased requirement for electrical cooling, wind power is producing its least amount of energy. Of course, during this time, we have our solar panels performing at their best, but even that isn’t enough to avoid the use of natural gas peaking plants.

A lot of criticism about renewable power, especially wind and solar, revolves around their intermittent fuel sources. The wind isn’t always blowing, and the sun isn’t always shining. These clear inconsistencies with wind power is why energy storage is often cited as a key requirement to make renewable power more effective in the future.

We now have a good understanding of how wind power is performing in Ontario. The winter season is clearly the dominant energy producing season, and as suspected, there can be some large inconsistencies in power production on a daily basis. Hopefully the province will continue supporting wind power and monitoring industry advancements with large scale energy storage to further optimize our clean electricity grid.

Greg Young is a mechanical engineering graduate from the University of Guelph, with a specialization in sustainable energy systems. Greg now has a career in the energy industry and writes articles on various energy sector topics in his spare time.

For more detailed graphs, please visit tiny.cc/lzq3iz

Get a complete solution for all of your lockout needs

• Lockout padlocks, devices, and identification

• Procedure management software

• Training, program development and more

In Canada, all electrical equipment available for sale is required to be approved as per Rule 2-024 of the Canadian Electrical Code (CE Code). Almost all provincial Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJs) have similar requirements that prohibits sale, display, install or use of electrical equipment that has not been approved by the recognized certification body or field evaluation agency to the applicable product safety standards. Approved electrical products bear one of the recognized marks, such as CSA, cUL, cETL, etc. The complete list of recognized marks in Ontario is published on the Electrical Safety Authority (ESA) website.

In Ontario, the ESA looks after Product Safety regulation 438/07 which requires approval of all electrical products, including consumer, commercial and industrial products (before and after sale). The ESA is responsible for the safety of commercial and industrial electrical products (post-market issues), while Health Canada is responsible for the safety of consumer products (post-market issues) nationally.

“Third-party” approval requirements

In North America, electrical products are required to be approved by an independent “third party,” which refers to a certification body or field evaluation agency accredited by the Standards Council of Canada. In Europe, the safety of products is determined by a “first party,” which means that the manufacturer or supplier of that

product conducted the conformity assessment and made an attestation that the product complies with the applicable requirements.

A market survey was done to compare the safety of some consumer products (small household electrical appliances) in North America and Europe that were assessed by first- and third-party evaluation. The published results show that third-party testing, inspection and certification provided higher levels of compliance: 17% of self-declared products showed dangerous faults, compared to less than 1% for products that were third-party certified. The market survey was done from 2014 to 2016 by the International Federation of Inspection Agencies and the International Confederation of Inspection and Certification Organisations.

For products evaluated by a “third party,” a series of safety tests were conducted at an independent lab against established standards. The safety tests were based on applicable safety clauses (e.g. heating, abnormal operations, double insulations, warnings, etc.) within the standards.

This indicates a large safety risk with unapproved electrical products.

Over the last decade, the internet has changed how consumers shop and businesses advertise and sell their goods and services. Europe’s OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) has found that a range of non-compliant products, which have been prohibited from sale, recalled from the market or present inadequate product labelling and safety warnings remain available for sale online. The OECD noted that 68% of banned or recalled products were supplied online. In addition, 55% of some selected products offered online did not comply with safety standards.

Before online purchasing:

• Know who are you buying from.

• Know which products to avoid. Visit local and global recall databases for unsafe products.

• Read safety warnings and instructions to make the best choice.

• Check ratings and reviews.

• Buy products approved for Canada.

After purchase:

• Consider registering a product with the manufacturer.

• Double-check the product bears a recognized approval mark.

• Report any safety issues to Health Canada or the local authority.

The Canadian Advisory Council on Electrical Safety (CASES), Health Canada and provincial AHJs are working together to address the online sale of unsafe electrical products.

Always consult your AHJ for more specific interpretations.

Tatjana Dinic, P.Eng., is the Code Engineer at Electrical Safety Authority (ESA) where, among other things, she is responsible for code development and interpretation, improving harmonization between codes and standards. She is a Professional Engineer with M. Eng. degree from University of Toronto and a member of CSA CE Code-Part I, Sections 4, 10 and 30. Tatjana can be reached at tatjana.dinic@electricalsafety.on.ca.

FIRE SPRINKLER SYSTEM CONNECTIONS

EZ-LOCK® 74ASP SNAP-IN MC CABLE CONNECTORS

MIGHTY-HOLD® UCS SERIES UNIVERSAL CLAMP STRAPS

TRANSITION AND CONNECT MC CABLE TO EMERGENCY LIGHTING

MIGHTY-MERGE® 5157-DC EMT TO MC COMPRESSION TRANSITION COUPLINGS

EZ-LOCK® 39ASP SNAP-IN MC CABLE CONNECTORS

SINGLE AND DUPLEX STEEL QUICK INSTALL CONNECTIONS

EZ-LOCK® AMC-52QI MC CABLE CONNECTORS

EZ-LOCK® AMC-50QI MC CABLE CONNECTORS

CONNECT AND SUPPORT MC-PCS LUMINARY CABLES

MIGHTY-HOLD® USD SERIES DUPLEX UNIVERSAL STRAPS

EZ-LOCK® 590 SERIES MC CABLE CONNECTORS

With more ways to earn loyalty points and redeem great prizes, the new and improved AD Rewards program allows you to capitalize on the power of your purchases from AD distributors like never before.

With over 6,000 valuable merchandise and travel rewards, your relationship with your AD distributor has never been more powerful…or lucrative.

Join today at any of these participating AD distributors.