VISUAL GUIDES FOR

SPECIAL EDITION: DRAINAGE DONE DIFFERENT

SEPTEMBER 2025

Reader Service

Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal, Customer Service Rep.

Tel: 416-510-5113

Fax: 416-510-6875

Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor | Bree Rody brody@annexbusinessmedia.com 437-688-6107

Sales Manager | Sharon Kauk skauk@annexbusinessmedia.com 519-429-5189

Account Coordinator | Melissa Gates mgates@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager | Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5183

Media Designer |Lisa Zambri lzambri@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher | Michelle Bertholet mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

CEO | Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

Subscription rates:

Canada – 1 yr $17.85 CDN

Canada – 2 yrs $25.50 CDN

USA – 1 yr $35.19

From time to time, we at Drainage Contractor make our subscription list available to reputable companies and organizations whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you do not want your name to be made available, contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2025 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

Sections

THE BASICS

5: The hard sell

8: A model for the future

BUFFERS AND BIOREACTORS

9: Buffers and bioreactors 101

11: Deep dive: ROI

12: The innovators

14: In conversation: Jacob Handsaker

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DRAINAGE WATER RECYCLING

16: Controlled drainage 101

18: Deep dive: ROI

19: The innovators

21: Drainage water recycling 101

22: In conversation: Chris Hay

23: DWR in action: Iowa

24: DWR in brief

26: DWR in action: Ontario

SPACING AND LAYOUT

27: Terracing 101

28: Spacing 101

30: Deep dive: Clay soils

Your inbox, every two weeks Drainage Contractor continues to bring you the best of the web, with the new, the now and the relevant coming straight to your inbox via our free, biweekly eNewsletter. Subscribe today at DrainageContractor.com.

New eNewsletters

Notice something new in your inbox? Earlier this year, we launched two new free eNewsletters: Just The Good News – for a dose of industry optimism – and Cover Stories – for deeper drainage dives.

Think different (but hopefully not for long)

I"There are opportunities for sophisticated new systems that create more efficiency."

by Bree Rody

t’s hard to imagine that Apple – which as of 2025, produces the phones of approximately 155 million Americans, the personal computers of about one quarter of the country’s population and, for better or worse, reinvented the way we consume music – would ever label itself as “different” or an alternative to anything. But in the 1990s, Apple’s market share wasn’t what it is today. The iconic "Tink Different" campaign ran counter to Intel’s "Think" campaign at a time when Apple was struggling – between 1992 and 1997, Apple saw about 80 percent of its market value deplete, in contrast to the tech-heavy Nasdaq index, which was rising and strong. Despite being on the brink of bankruptcy, the brand went big on its media buy – it was massive – and its creative strategy, honoring divisive thinkers – “misfits” and “rebels” – like John Lennon, Muhammad Ali and Einstein.

We all know how the story ended. It’s not just those nine-figure user stats; it’s the fact that Apple is now in a position where it doesn’t have to (or, frankly, get to) play the “different” card. That’s the dream, isn’t it?

You could say that’s the dream here – that hopefully in only a few years’ time, a “Drainage Done Different” eBook won’t need to exist. There are already signs that the innovative solutions explored here – everything from drainage water recycling to two-stage ditches and combination systems – are making their ways into the mainstream. This is especially applicable in areas where drainage is net-new – and believe us, drainage is making its way into new jurisdictions. There are opportunities abound for the introduction of edge-of-field and in-field practices, or sophisticated new systems, that focus on creating more efficiency within drainage systems, cleaner water being discharged into waterways and –everyone's ultimate goal – not a drop too much water being taken away from the crops that need it.

Of course, with the massive investment that goes into drainage and farmland and even conventional drainage systems, producers naturally want to know the ROI of something like a saturated buffer or bioreactor before installing. Although there is research in this eBook that shows potential yield and ROI benefits to these systems (see pages 11, 18 and 24), we know it will still likely take more to get these innovative practices onto fields, whether that’s contractors being incentivized to offer certain installations, cost-sharing programs or some other solution.

But if there’s one thing we know this industry can do, that’s innovate. Hopefully there will come a day when this is the type of drainage that is not done differently.

Read on, and thank you for your continued interest in draining differently.

THE HARD SELL

Before we dive deeper into drainage done different, let’s learn more about the what, the why and – most importantly – the how much behind what’s known as edge-of-field practices, which some of the practices in this ebook fall under.

With growing concerns about climate change and water quality, edge-of-field practices are coming into sharper focus since they’re designed to slow, filter, and process both surface and subsurface runoff from farm fields.

by JACK KAZMIERSKI

Respondents in the Midsouth, South and Southwest were more likely to report little to no competition in their area, but all report increases in competition in the last five years. Image courtesy of Matt Helmers.

“Leading at the Edge,” a report published in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy, the Meridian Institute and the Soil and Water Conservation Society, outlines some of the benefits of edge-of-field practices:

“Conservation drainage practices such as bioreactors, saturated buffers, and constructed wetlands are designed to intercept tile flow and provide the conditions needed for nutrient assimilation and retention.”

The report explains that once these practices are put into place, they require little hands-on management. And, the report explains, many practices "can provide additional ecosystem service benefits including carbon storage, pollinator and wildlife habitat, flood water storage, and streambank stabilization.”

WIDESPREAD ADOPTION

Although the benefits of edge-of-field practices are clear, North American farmers aren’t jumping on the bandwagon in large numbers just yet – at least not in numbers large enough for us to see the desired impact on our environment.

Putting these practices in place on a larger scale will take time, and most experts agree that we need more awareness, more incentives and more financial resources.

“I think we need more education about the importance of these practices, and the need for these practices,” says Matt Helmers, professor in ag and biosystems engineering at Iowa State University, and director of the Iowa Nutrient Research Center. “We also need to create a sense of urgency, and we need to make people aware that there is a problem with water quality, and

THE BASICS

Projects such as bioreactors and saturated buffers are large projects – literally – and advocates agree they can be a tough sell, because they aren’t readily visible to the naked eye. Image courtesy of Matt Helmers.

that we need to do something about it.”

Raising awareness is the first step. “There’s still the hurdle of how to implement these practices most efficiently,” adds Helmers. “If someone says they want a bioreactor, saturated buffer, wetland or controlled drainage, then how do we make it easy for them to do that? I think that’s a barrier to adoption in many cases.”

The challenge, argues Helmers, is that paperwork and bureaucracy can get in the way. “They don’t want to wait 18 months to get this in place,” he explains. ‘They want to see it happen quickly, and in certain cases, there’s just too much red tape.”

Another hurdle, says Helmers, is money. “In some cases, the finances aren’t there for the cost share,” he adds. “We are very fortunate in Iowa, because we have a state agency that understands the importance of these practices, and has put a lot of resources in place. But I wouldn’t say that’s the case across the board as we look at the whole Upper Midwest. So, I do think that in many cases, there’s a need for greater investment in these practices.”

STICK VERSUS CARROT

The question about widespread adoption of edge-of-field practices often boils down to the need for incentives vs. the need for more laws. In other words, which approach will convince more individuals to pay attention to the need for these practices?

“Our current framework is a voluntary approach, and I foresee that it will stay that way for quite some time,” says Helmers. “Under our current framework, we need more incentives and more opportunities to make this as efficient as possible.”

Stu Frazeur, independent contractor and board chairman for the Minnesota Land Improvement Contractors of America (MNLICA) says while education is a must, there are times when appealing to benefits can be even more compelling.

“What I find is that there are some farmers who are looking at the situation and they see bioreactors and the saturated buffers, which fall in a different category because they really don’t see results from those with the naked eye,” explains Frazeur. “It’s an easy sell for tile, because people look and say, ‘Man, you put that in, now my crops are growing great!’”

Buffers and the bioreactors, he says, are a harder sell. He says there’s a need to educate everyone involved, not just farmers. “We held a big field day back in 2014,” he recalls, “And it was attended by quite a few NRCS people, which is good, because they’re the ones who need to see how this works.”

The better informed everyone is, the more likely we can move ahead collectively towards the greater implementation of edge-of-field practices, argues Frazeur, offering the following scenario as an example: “My thinking is that when people go to get a permit, the local government unit can say, ‘Have you thought about a saturated buffer? Have you thought about this or that option?’ And then we can start talking about some of those structures and some of those edge-of-field treatments.”

Frazeur believes that there’s more than one way to spread the word about best practices. “We need to piggyback on events farmers are already attending,” he explains. “When we have seed meetings, we can

take 10 or 15 minutes and talk about how to control drainage, for example. And we really need more farmer-to-farmer discussions, where the early adopters explain the benefits to others.”

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

While educating individual farmers is key to promoting edge-of-field best practices, more ground can be covered with a collaborative approach. Keegan Kult, executive director of the Agricultural Drainage Management Coalition (ADMC) is part of a “batch and build” initiative in Polk County, IA.

“Instead of working with one individual landowner at a time,” explains Kult, “We looked at the whole watershed, found all the suitable outlets, and packaged them together. We also had a fiscal agent who had agreements with all the landowners. They assigned all their payment programs over to the fiscal agent, and that agent then managed the project and hired the contractors to do the actual installs.”

By assigning one individual fiscal agent to represent all the landowners and their properties, “the contractor was able to go up and down the stream and do all the installations, without having to deal with multiple decision makers,” explains Kult. One of the other stakeholders in this project was the NRCS. “They were great partners,” adds Kult, “And they actually did a lot of the technical assistance, the design work, and updating conservation plans within Polk County.”

INNOVATIVE STRATEGIES

During the planning phase for the batch and build initiative, Kult, along with some of the key stakeholders, decided to adopt a proactive strategy. “We decided on a direct outreach campaign, instead of waiting passively for farmers to come to us and sign up for these practices,” he explains. “Farmers have a million things going on, and it’s not that they don’t want to focus on conservation, but they’re busy, and they’re not going to come to us.”

Rather than sit by and wait, Kult and his team sent out mailers to farmers they thought might have a suitable site. “We had a model to show where the suitable sites might be in the watershed, and in our

letter we explained that one of our project managers would be contacting the farmer within the next two weeks to discuss details. And that’s exactly what happened.”

The strategy worked, opening the door for the team to survey over 300 outlets, 120 of which resulted in installations. “Taking on projects like this in batches makes the process more efficient,” adds Kult. “The design engineers can go out and survey 10 sites in a day instead of only two, for example, so the cost of engineering goes down because they’re able to visit so many more sites per day.”

COUNTING COSTS

While the batch and build project didn’t cost farmers anything to implement, they did have to agree to maintenance contract. “We had 100 percent cost share on this project because the benefits are downstream,” explains Kult. “So although the producers weren’t paying for the installations, they are responsible for managing them. They have to sign up for a 10-year maintenance agreement, so they

do have skin in the game on that front.”

Although the success of the batch and build program in Polk Country can serve as a template, Kult says some details still have to be ironed out. “We’re looking at how we can use the approach in other areas,” he says. “So, part of the process is evaluating the infrastructure. How many people have job approval authority in that state? And what kind of \financing is available?”

Kult and his team have put together a handbook that can take interested parties through the process with less mistakes and hiccups along the way. “Through a project funded by the Iowa Department of Ag and Land Stewardship, we put together a toolkit that we can share with other potential project coordinators showing the framework of this batch and build program,” he says.

The key to success, Kult adds, is finding a “local champion,” which is someone who would be willing to spearhead the effort in each county or region. “To get things started, you need a local leader who

THE BASICS

An open house at Farmamerica, an agriculture outreach facility near Waseca, MN, observing a controlled drainage system. Image courtesy of Stu Fraseur

can bring all the potential partners into a room to start the discussion,” he says. “For anyone who would be willing to do so, we have the toolkit, and we’d be more than willing to partner with them and offer guidance. We might not be able to have boots on the ground, but we definitely would help them get their project off the ground.” DC

THE BASICS

A MODEL FOR THE FUTURE

Understanding recommendations – such as spacing, controlled drainage or edge-of-field practices – can come from understanding the future.

by BREE RODY

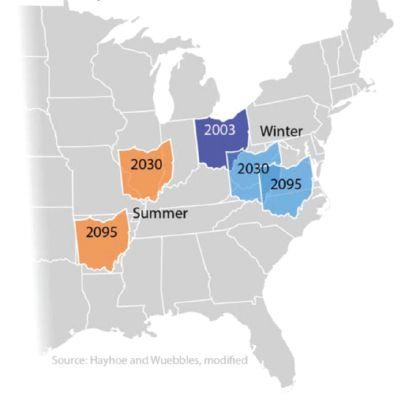

A visualization using what’s known as the Shifting States Model to show what future climates in Ohio might look like. Image by Hayhoe and Wuebbles.

In order to make the future better, one must look to the past.

Elizabeth Schwab, research scientist at Iowa State University, hopes to help the industry look to the future informed by history. Her work, which introduces the world of “future Ohio,” isn’t concerned with robots and rockets. Future Ohio refers to the state’s climate conditions.

The project began at the Ohio State University, with fellow researcher, Toni Chinchar, an instrumental contributor in running the simulations. Schwab's supervisor had an interest in creating visuals to support what is known as the shifting states model, an easy-tounderstand graphic representation of an area’s climate and change over time.

Scenarios were put together using information on temperature, humidity and precipitation, incorporating climate models to understand what the same states might look like in the future, and likening those results to present-day states. In 2030, Ohio summers will feel like the 2003 summers in southern Illinois. By the end of the century, summers in Ohio will feel like present-day summers in Arkansas.

“If I hear that we’ll see an increase of X degrees by the end of the century, I can’t contextualize that. If you say, ‘it’s going to feel like summers in Arkansas,’ I can picture that and I don’t like it.”

FACILITATING CONVERSATIONS

For years, climate change has been a taboo subject in agricultural industries.

Farmers and other industry professionals sometimes feel blamed or scrutinized.

This research, says Schwab, can bridge those gaps. “Anytime you have communication, you want create a space where people feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and experiences, avoiding polarizing languages when you can... Framing [conversations] in terms of changes in weather, and year-toyear variability... paint a picture.” For example, she says, it’s handy to discuss droughts using tangible or real examples, rather than hypotheticals or alarming language. Connecting changing weather to recent events allows farmers to think about how they might use their resources differently in the future or plan for similar extraordinary events.

CHANGING DRAINAGE NEEDS

Schwab is among the many who believe drainage decisions should not be made just for today, but for years in the future.

Her models predict fewer days with saturated conditions and less drainage discharge overall, at both spacings. On one hand, this means less nutrient export. But with more potential drought conditions, the priority for drainage systems then becomes keeping the water where it needs to be: available to the plants.

It’s less a matter of the scale of drainage more using innovative tools or new angles. Some producers consider splitting laterals, but Schwab says there are other resources for investment, such as drainage water management (like controlled drainage),

BUFFERS AND BIOREACTORS

BUFFERS AND BIOREACTORS 101

The what, the why, and the “who’s going to pay for that?”

In this section, we explore the world of saturated buffers and bioreactors, which are part of the family of edge-of-field practices that clean water, removing excess nutrients from that water before it makes its way downstream.

by ROBYN ROSE | Files and intro from BREE RODY

These systems are both edge-of-field practices and have many similar functions and benefits. Both are designed to remove excess nutrients such as nitrates and phosphorus. They can be implemented together or separately.

Conceptually, a buffer is just that – a buffer between one thing and another. A saturated buffer is an area of vegetation between agricultural fields collecting nutrient-laden water, leeching contaminants from the runoff water. Buffer strips can also serve dual purposes, incorporating native plants to foster pollinator populations while also reducing the amount and turbidity of water entering waterways.

A bioreactor, also known as a denitrifying bioreactor, is a device that can be as large as a small studio apartment, buried at the edge of a field and filled with woodchips (or another carbon

source – see page 12). The bacteria from that source converts nitrates into nitrogen gas. They’re preferred by some because, being underground, they don’t impact in-field management. The woodchips only need replacing every 10 to 15 years. The practice has been around a little over a decade, but is still considered new and niche (only around 80 farmers between Iowa and Illinois are using bioreactors as of 2024).

Consistent figures on cost can be hard to quantify – some experts say they can cost up to $10,000 to install, including material costs. Others say, depending on carbon source, it can cost up to $30,000. Programs like EQIP and CRP can help cover up to 100 percent of costs, and some programs offer a one-time cost-share – but most landowners aren’t so lucky, or haven’t made those connections yet.

But would they be more motivated to make the investment if they knew the numbers?

SUCCESS, BY THE NUMBERS

According to some data, bioreactors are helping farmers in the Midwest reduce their nitrogen (N) loss up to 62 percent.

Reducing N loss is a focal point of a study conducted by Laura Christianson and the team at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. For the past decade, Christianson has studied tile drainage, and she and her team monitor about 15 bioreactors across the state of Illinois.

This study used a modified bioreactor to determine whether design improvements could treat more water and reduce N loss by a greater percentage.

An overhead view of a bioreactor, which typically measure between six and 22 feet wide and 50 to 100 feet long. Images courtesy of Laura Christianson.

BUFFERS AND BIOREACTORS

HOW BIOREACTORS CONTRIBUTE TO CONSERVATION

The efficiency of bioreactors’ annual N load removal has ranged from nine to 62 percent across varous studies. But the right environmental conditions must be achieved. Therefore, biochemical

engineering is required in the design phase.

Many factors can impact bioreactors' effectiveness, beginning with the nutrient concentrations (such as pH and dissolved gases) in the bioreactor, as well as external seasonal and temperature changes.

Upstream, an inline water control structure routes the water correctly in the wood chips. A bypass flow pipe prevents drainage water backup. “The bypass flow pipe is an important part of the design for practices like bioreactors, or even saturated buffers or other practices.”

BALANCING AGRONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL GOALS

“There’s this concept of conservation drainage practices that we promote to meet both agronomic goals of crop production and environmental goals of making sure we keep our water clean, and making sure that we’re good upstream neighbors,” says Christianson. “The states in the Midwest that drain to the Mississippi River basin all have nutrient loss reduction strategies that guide each state’s efforts to meet a 45 percent nitrogen and phosphorus reduction goal,” Christianson says. “That is one goal that each state is trying to meet.”

As farmers look to upgrade existing tile systems and improve drainage structures, demand for drainage contractors who have

EVERYTHING YOU WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT BIOREACTORS BUT WERE TOO AFRAID TO ASK

A quick Q&A with Laura Christianson

DC: Could you explain in the simplest terms how bioreactors work?

LC: It’s basically an excavation or trench filled with woodchips, where woodchips serve as the food source or the carbon source for denitrifying bacteria – natural, native, good bacteria –that clean nitrate out of the water as the drainage water flows by them.

DC: What’s the simplest way you would sell someone on bioreactors?

LC: I all of the years [where] we monitored bioreactors in Illinois, in no year, at no site, did the water leave the bioreactor with more nitrogen in it than the water that entered. That’s the whole point. Some of the conservation practices we promote – nitrification inhibitors, moving nitrogen fertilizer applications from the fall to the spring or using a cover crop –those other practices don’t always work exactly right in every year, because it’s hard to predict sometimes when nitrogen mineralization happens.

DC: A lot of landowners understand the benefit, but there’s not a direct ROI to bioreactors. How can we reconcile that when promoting them?

LC: One of the selling features for me is that this is an engineered technology. Challenges or problems we face with getting bioreactors to work better are just an engineering problem. Those are easy to solve. Timing a cover crop right so you can get it to germinate, or figuring out the ROI for doing an alternative crop, getting those conservation practice to really take off will require a lot of social investments, policy investments, changes in infrastructure. Engineering-oriented problems are the easy problems to solve.

experience implementing conservation drainage practices will increase.

“It’s a lost opportunity to not also be thinking about water quality, things like bioreactors, saturated buffers, drainage, water recycling and wetlands,” Christianson says. “All of these practices are things that drainage contractors can do.”

While contractors are the obvious choice to install and plumb the bioreactor, farmers need to work with organizations like the NRCS when designing a bioreactor for their specific field.

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

For three-and-a-half years, Christianson and her team studied their modified bioreactor, measuring the level of N in the subsurface flow before and after it entered the bioreactor.

In the end, the specially designed bioreactor with the increased width and added baffles treated approximately 40 percent of the annual drainage flow volume, resulting in a 22 to 24 percent N removal at the edge of the field. While this demonstrates the bioreactor was effective, it did not result in more water being treated or an increased N reduction percentage.

“The bioreactor still worked, and it still worked on par with what we expect bioreactors to do, so it was kind of a mixed bag. It didn’t work as well as we wanted it to, but it did work very consistently with what we would have expected otherwise,” Christianson says.

Despite this modified design not performing as well as expected, the team continues their research to discover how bioreactors can treat more water.

To effectively sustain agricultural production in the Midwest and around the world, both the growing cycle and environmental impact need to be considered.

“We know tile drainage moves nitrogen from our fields, and we know that nitrogen is going downstream. And so, my personal belief is that our farmers and our drainage contractors are good environmental stewards and know in their hearts that we need to be good upstream neighbors,” she says. “There’s a better way to do agriculture.” DC

Laura Christianson digs a trench for a bioreactor in Illinois.

BUFFERS AND BIOREACTORS

DEEP DIVE: ROI

by Drainage Contractor staff

Edge-of-field practices such as saturated buffers and denitrifying bioreactors require significant upfront costs, such as excavation, material and consultation – and not all landowners have access to cost-sharing programs or other grants. In summer 2025, Iowa State University posted interviews with two specialists – Tom Isenhart, professor of natural resource ecology and management, and Michelle Soupir, agricultural and biosystems engineering professor – to discuss factors impacting the ROI of both practices.

SATURATED BUFFERS

Isenhart is known for his work developing and promoting saturated buffers as an edge-of-field practice. He also studies other BMPs, including saturated grass waterways, a new practice being developed at the University of Iowa. His work mainly focuses on using those BMPs to reduce nitrate-nitrogen, although he and his colleagues are also looking at the potential of BMPs to reduce phosphorus.

Since 2010, Isenhart has led water quality research at more than 15 locations, which represent almost 100 "site years" of data. This allows the team to track the efficacy of the practice over time, including through variable weather. “People often focus on an edge-of-field BMP’s ability to reduce nutrient concentration from the point water flows into the BMP for treatment to where it leaves and enters a waterway or ditch,” said Isenhart in the ISU post. “However, what really has the most significant impact on water quality is how much water flows through the practice. If a BMP can capture a lot of flow, you gain a much greater reduction in the mass of nitrogen it treats, even if the reduction in concentration is lower. Tracking a variety of parameters, which include flow, increases confidence that our results realistically reflect different locations and conditions.”

Isenhart added more monitoring is needed at the small watershed scale where enough practices have been installed so that that "we might be able to see the needle moving." This will then allow researchers to compare the practices to other sites. “It’s fairly easy to see improvements from

individual practices, but does that hold up at the watershed level?”

BIOREACTORS

Michelle Soupir's research has focused largely on bioreactors and how to make them not only effective but also practical. For more than a decade, her lab team has overseen a pilot bioreactor system on a research farm near Ames, IA, featuring nine mini bioreactors filled with wood chips, monitored from inflow to outflow, in order to measure their efficacy. The bioreactors removed from nine to 54 percent of incoming nitrate concentration, depending on various factors. Quicker flow could result in lower percentages being removed (Editor's note: For another innovative carbon source from Soupir's team, see Page 12)

Like Isenhart, Soupir says scale is needed to see how results stack up. “We’ve started to get enough bioreactors on the ground to potentially move the needle in some watersheds,” she said. “With additional funding from a variety of sources, we’re working around the state with Batch and Build type projects, pioneered by the Polk County, Iowa, Soil and Water Conservation District and the Iowa Soybean Association. At this point, 24 new bioreactors are designed, 15 installed and nine more are planned. We’re also running tracer studies on these to continue to follow their hydraulic properties and water quality benefits.”

The estimated cost to install a bioreactor ranges from $15,000 to $30,000 depending primarily on size and carbon source.

“At a time when farmers are facing major economic challenges, it’s more important than ever to provide good guidance to make sure that conservation practices will provide the desired return on investment for private – and public –dollars,” Soupir said. DC

THE INNOVATORS

The latest in carbon sources

Anew Iowa-based research project hopes to provide landowners with more options, flexibility and resources to implement bioreactors.

by BREE RODY

For all its potential links to adverse water quality, subsurface drainage also has an undeniably positive relationship with crop yield and quality. With only about 80 farmers between Illinois and Iowa using bioreactors, there are some prohibiting factors – namely cost and accessibility. Additionally, access to a carbon source for the denitrification process is a sticky issue for some.

That high-carbon material used in bioreactors is, most commonly, woodchips. But the Iowa project looks at a potential alternative to woodchips. And, in the Midwest, what better material than corn?

Well, corn cobs, to be exact.

Michelle Soupir, professor of agricultural and biosystems engineering at Iowa State University, explained that the primary

purpose of this project was to explore corn cobs as an alternative to woodchips, for a few different reasons.

According to Soupir, lab studies showed that corn cobs are more biologically active than woodchips, which could increase nitrogen removal. But corn cobs could also be a viable alternative because of the cost and demand for bioreactor woodchips.

A HIGHLY SPECIALIZED CARBON SOURCE

Soupir explained to Drainage Contractor that the woodchips found in bioreactors must fit very particular specifications. These aren’t just any woodchips – they’re highly specialized.

“The woodchips need to be at least one inch, and most chippers do not produce a chip size that meets that requirement,” she

ABOVE: A research team Iowa State University examines a site of minibioreactors near Ames. Image courtesy of Michelle Soupir.

BUFFERS AND BIOREACTORS

explains. “There’s [only] two facilities that produce woodchips that are the appropriate size to meet NRCS specifications.”

These chippers will chip up the logs, and the chips then enter into a separate screening process with a screen that is between three-quarters and one inch, in order to screen out the too-small pieces. This is not the most efficient process, says Soupir. “Because they have to screen out all of the smaller pieces, by our estimate, [they lose] about 40 percent – almost half of the wood product.”

Then, she says, there’s the logistics piece: adding on the cost of transportation, and the timing of getting woodchips where they are needed, when they are needed. “It does get complicated, because there are so few places where the woodchips can be sourced from in the state.”

In short, even though these woodchips literally grow on trees, they don’t exactly “grow on trees” when it comes to immediate and easy availability.

For some contractors and companies, like Illinois-based Grade Solutions, the solution is to manufacture their own woodchips. But not every company has those resources.

“You would think… if there’s a clearing, we might say, ‘Oh, here’s all this wood, let’s just put it into some bioreactors!’ But the equipment required to get the chips to the size that we need, is not easily available. So that’s a big barrier, to get us from where the wood is available to where it’s needed.”

As such, the Iowa project began in 2018.

THE STUDY

With the base knowledge that corn cobs are valuable because of their biological activity, as well as their similar size properties to the woodchips, Soupir’s research team set up an experiment at Iowa State’s pilot-scale, mini-bioreactor research site near Ames. The bioreactor cells were fitted with: 75 percent woodchips and 25 percent corn cobs by volume; 25 percent woodchips and 75 percent corn cobs; and 100 percent woodchips. Each set of the three carbon treatments had a bioreactor operated at two-, eight- and 16-hour hydraulic residence times.

Monitoring the systems, which took

place over four years, revealed that the bioreactors with corn cobs present had higher nitrate removal rates than the bioreactors whose carbon sources were made of entirely of woodchips. The 75 percent corn cob/25 percent woodchip mix performed best. That mix also showed the best hydraulic efficiencies, and clogging has not been a concern so far.

On the topic of efficiencies, the 75 percent corn cob mix also showed relative costs per amount of nitrogen was lower than the 100 percent woodchip mix, with costs ranging from 22 to 60 percent lower. Soupir says it’s better to look at costs in terms of a “per removal basis.” “It could cost the same to build two bioreactors, but you may get a better investment for your money if you remove more nitrates.”

"By our estimate, [chippers lose] almost 40 percent of the wood product."

For lifespan, woodchip bioreactors are predicted to have a lifespan of about 10 years before they require a new carbon supply. Initially, the team thought that because corn cobs are a different kind of carbon source, they would break down more quickly than the woodchips. Now in their sixth year, Soupir says they did not see the drop-off in the ability to remove nitrates.

BIGGER PICTURE: BIOREACTOR ADOPTION

The importance of bioreactors in the broader picture of water quality can’t be overstated, with their ability to reduce nitrates at an average of 15 to 60 percent. But with bioreactors coming with a hefty price tag, the goal of the corn cob study, says Soupir, is to provide landowners with more options to reduce nitrates in their water, ultimately resulting in the adoption of more bioreactors.

But it’s not as though corn cobs are

regarded as a waste product; Soupir says that getting the corn cobs gathered and available for bioreactors has been “harder than expected” and that feed corn facilities have been the more common source of corn cobs. “There’s not a ton of corn cobs just sitting around; we had to work rather hard to source the corn cobs, almost as hard as gathering the woodchips.”

But Soupir is hopeful that because of the biological activity of corn cobs and their many benefits in the broader agricultural sphere, they can not only become more readily available but also help provide producers with another revenue source.

As for further adoption of bioreactors, Soupir acknowledges that efforts from various agencies such as the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (IDALS) and the Department of Natural Resources have helped increase not only adoption, but also awareness.

“There have been a lot of efforts to get more practices on the ground, and to streamline some of the processes so that they can be a little more efficient for the contractors, for the engineers and for the farmers.” She credit’s the state’s batch-andbuild approach to getting more bioreactors built and in the ground.

“It’s allowed contractors to do the ‘batch’ part, where all the things that are needed for a bioreactor can be delivered; [contractors have built] multiple bioreactors within a relatively close area, and so that makes installation go much more quickly, which makes a more profitable operation.”

In 2012, an assessment as part of Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy suggested that the state needed anywhere from 76,000 to 133,000 bioreactors, in combination with other practices, to meet the nutrient reduction goals. The state is still far from those numbers, but more research and incentives can play a part in adoption.

As for the Iowa research team, this year, the team will study a bioreactor comprised of 100 percent corn cobs as a carbon source, with funding from a Conservation Innovation Grant through the NRCS. They are also looking at other carbon sources, including different types of woodchips, and other ways to increase bioreactors’ effectiveness. DC

BUFFERS AND BIOREACTORS

IN CONVERSATION: JACOB HANDSAKER

An Iowa entrepreneur says bioreactor initiative “has paid in dividends”

by BREE RODY

In 2008, Jacob Handsaker was farming with family on his fifth-generation farm. But as more family wanted to join the operation, there wasn’t enough work for everyone. The family looked to diversify.

“We’d had a backhoe for years,” Handsaker explains. When he connected with an old friend with excavation experience, the business blossomed from there.

These days, Hands On is “pretty busy.” The company places an emphasis on proactivity, “trying to head off problems before they start… Our approach is a proactive approach, rather than a reactive approach.” Among his achievements, he’s one of Drainage Contractor’s 2023 GroundBreakers, an honor bestowed largely because of that proactivity.

“When the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy started 10 years ago, we made a commitment to look at that and see that that’s going to be the future.”

He says the company knew they’d be involved “whether we liked it or not,” and chose to lean into it hard and focus on that. “It’s paid dividends for us.”

Handsaker has worked in partnership with agencies and initiatives such as the Agricultural Drainage Management Coalition (ADMC), the Iowa Agricultural Water Alliance and the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (IDALS)’ Batch and Build program. The mission is simple: get more bioreactors in the ground and buffers at the edge of fields, in order to get more nitrates out of waterways. The buffers and bioreactors aren’t only installed on net new drainage

systems; Handsaker told attendees of the 2024 North American Drainage Conference many of the installations he’s done have been on existing clay tile.

“Bioreactors can be placed anywhere,” he says. And because of the Batch and Build model, landowners are more incentivized to agree to the installation.

“We’d been doing these [installations] for several years before the Batch and Build program came in, but it was the farmer taking the lead, and it took so long, and it wasn’t efficient for the farmer. We had customers who were waiting up to three years for a simple design on a bioreactor.”

The program took that out of the hands of the farmer, says Handsaker.

“It’s a cost-share initiative. The farmer’s not going to be out much, or sometimes, anything, depending on [the] program.”

Handsaker says the company’s involvement with organizations isn’t to set them apart competitively, but to set a good example and do some good. “We all need clean water to drink, to recreate in, for our livelihoods. These organizations, they’re really focused on that, and being a part of these organizations takes us to a level at which we’re able to learn and motivate others to be involved – maybe kind of leading the way.”

He recommends contractors envision themselves as changemakers – they “really can do these things,” says Handsaker, who is glad that more contractors are displaying that leadership and involving themselves in such organizations. Speaking at the 2024 North American Drainage Conference,

Handsaker said it doesn’t require a major reinventing of the wheel – once you’re familiar with the programs that can share costs and support the installations, it’s best for a contractor to integrate them into what they’re already doing.

“What I would recommend or push people to do is integrate [edge-of-field installations] into what you already do as a tile contractor and drainage professional,” he says. “Understand what practices are going to fit where, how we’re going to be able to integrate these things. When designing a system, if you’re along a stream [and] they have a buffer, what are some opportunities to offer the customer a net good for water quality?”

One attendee asked Handsaker about grass clogging the buffer line during low drainage periods. “We really haven’t seen that as an issue,” he replied. “The grasses that are typically involved with these buffers are not deep-rooted grasses.” Other attendees wanted to understand advice on preparing bids or estimates for bioreactors and buffers.

“It’s just like any other excavation,” he explained. “There’s no smoking gun for these things. You’re installing tile, you’re digging a pit. You’re buying supplies, [and] you’ve got manual labor. Don’t overthink it, but don’t sell yourself short. Oftentimes, there are opportunities for them to be done during the off-season. So, your tile flow is not going to run when the crops are in the ground, typically – you could be putting in saturated buffers, or the excavators could be running on bioreactors.” DC

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DWR

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE 101

It’s a simple concept: Drain only what you need to, when you need to. What more could you want?

In this section, we look at forms of drainage water management – like controlled drainage, which, in its essence, involves regulating the water table, keeping it at a depth favorable for crop growth throughout the season.

This is achieved through a flow-restricting device, placed strategically inline with tile drainage pipes. The structures control the level of water at the outlet – full, partial or no drainage.

The idea is similar to controlled irrigation systems: by regulating the water table level, this helps mitigate water issues many growers face. In many environments – increasingly, in the age of extreme weather – one can go from having too much water to not enough in the same growing season, sometimes in a matter of weeks.

It goes with a broadly accepted goal in drainage: to drain only what is needed and not a drop more.

There are different types of control structures, but the two main types are open-ditch flashboard riser structures or inline control structures. The open-ditch structure is used either in ditches for small area control or at a drainage outlet. Inline control structures are attached to subsurface drainage pipes, and can either control the flow from individual pipes or on a subsurface outlet drain. The control structure is often a square drain box with the top above ground. It’s installed to intersect with the subsurface drain tile and a stop log is added to or removed from inside the control structure.

The stop log is usually a composite or aluminum board set at about 50 to 60

centimeters below the surface inside the control structure. These are also called flashboard risers, plates, mini-check dams or control gates.

Since the 1980s, controlled drainage has been applied to reduce nutrient losses in North America. Yet as of 2022, the practice hasn’t been widely adopted. The first iteration of the technology was considered cumbersome, and the wood used to dam the drainage water tended to swell, making the boards difficult to move. However, new technology has refined

files from BREE RODY, ROBYN ROSTE and JACK KAZMIERSKI

the system, making controlled drainage a viable option for many landowners and crop producers who farm on fields with slopes less than 0.5 percent. Smart technology offers further enhancements, such as notifications to raise or lower the boards based on weather forecasts and automated systems.

THE OHIO ANGLE

One name you’ll see pop up a lot in this section is Vinayak Shedekar, an assistant professor in water management in the Department of Food, Agricultural and Biological Engineering at the Ohio State University. This is for two primary reasons, both of which are connected: one, although Shedekar’s research areas of interest and extension specialization include many aspects of agricultural water management, agroecosystem sustainability, environmental quality, soil health, environmental BMPs and more, controlled drainage applies to many of those goals. Two, drainage has historically been part of a wider issue for farmers and Ohio.

“For more than 200 years, we have known that you can’t grow crops in the area without draining the soil,” he explains. The regions now largely known as the “corn-belt” have notoriously poorly draining soil, which means it’s going to need some assistance from tile systems.

A field-installed drainage water management structure. Image courtesy of Ohio State University Extension.

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DWR

We now know crop yield can double when land is properly drained. However, that’s only part of the problem. The other issue is the variability in the amount of rain Ohio might get in a given year. Some years might be very wet, while others might be very dry. In undrained lots, some years resulted in no yield at all. The land that was properly drained, on the other hand, did not experience years where they had zero yield. “In their cases,” Shedekar adds, “the variability in yield was plus or minus 20 percent.”

The practice of controlled drainage, often called drainage water management (more on that below) came into existence when that 20 percent variability was no longer seen as acceptable.

TERMINOLOGY, EXPLAINED

Drainage water management, Shedekar says, is more of an edge-of-the-field practice, and he warns that there may be a bit of confusion about the terminology. “Drainage water management

Inspecting and adjusting boards to manage water table level. Image courtesy of USDA-ARS Soil Drainage Unit.

and controlled drainage are used interchangeably,” he explains. “But drainage water management can also be a broader term for managing the drainage water. So you could take that water from the field, collect it in a reservoir, and recycle

that water back into the system using overhead irrigation or a sub-irrigation type of a system.” (Our drainage water recycling features go deeper into this – but remember, these systems are not interchangeable. They can work together, or separately).

This is the approach Shedekar says has worked well in Ohio. Collecting excess water in a reservoir during the wet months and then using that same water to irrigate crops in the drier months simply makes sense. “We have already tested this drainage water recycling system, even adding a combination of wetland in there, and we found good results,” he says.

To take it further, drainage ditches can be employed as part of a drainage network, “So if you’re managing water at the ditch levels, that still would be considered drainage water management,” he adds.

Even today, Ohio farmers struggle with water issues. “Very few farms in Northwest Ohio have irrigation, and the challenge is that we don’t have a source of water to rely on during the summertime,” he says. DC

TIMEWELL DELIVERS WHAT CONTRACTORS NEED

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DWR

DEEP DIVE: ROI

Controlled drainage is great in concept – but how can you make it work for your farm?

by ROBYN ROSTE

Controlled drainage has been applied to reduce nutrient losses in North America since the 1980s. Yet, 40 years later, the practice hasn’t been widely adopted. The first iteration of the technology was considered cumbersome, and the wood used to dam the water tended to swell, making the boards difficult to move.

It’s difficult to put a fixed cost on installing a controlled drainage system, because there are so many variables: slope, hydrology, number of gates, adding submains to create water management zones, multiple in-line stop log structures, field elevation, engineering design, soil type, soil variability, drainage intensity and more.

Purdue Agriculture estimates initial costs to range between $20 and $110 per acre. Mel Luymes, executive director of the Land Improvement Contractors of Ontario says, from her experience, installing controlled drainage costs about 15 percent more than a conventional system. (Editor’s note: for more on Luymes' experiences with controlled drainage in her own words, see Page 25).

“You need to make it curvy and then... your control gate can blow your costs out of the water,” she says.

The most suitable and cost-effective installations are on flat fields with a pattern drainage system, so one control structure can manage the water table within two feet without affecting adjacent landowners. In general, controlled drainage requires one control structure for every two feet of elevation change in a field.

There have been extensive studies in the U.S. on controlled drainage, with a focus on corn and soybean crops. However, there is

no research indicating which crop varieties respond best to controlled drainage. NC State Extension reports that for the past 20 years, North Carolina has documented the benefits to yield from controlled drainage. Generally, corn and soybean yields are increased by an average of 10 percent and up to 20 percent.

In a 2022 Drainage Contractor webinar, moderated by Luymes, Will and Rick Woodworth of Flying W Farms in West Virginia shared their experiences. On a previously poorly drained field, which produced typically between 160 to 180 bushels of corn, controlled drainage led to an increase of 90 to 110 bushels, and decreased water runoff.

Despite positive indications, yield research is still limited or inconclusive and most studies focus on nitrate reduction benefits. But general sentiment shows that controlled drainage has a positive effect. NC State Extension has said losses of N and P in drainage water can be substantially reduced by controlling drainage outlets during both the growing season and the winter months. Multiyear experiments on a wide range of soils reduced N losses to surface waters by more than 40 percent and P losses by about 25 percent.

Controlled drainage can both improve yields and profitability while also benefitting the environment by reducing nutrient runoff. And while it may not be available for every field at present, research is moving forward to determine how to best add this BMP to fields with elevation or existing tile drain systems. DC

Mel Luymes, LICO executive director, explains and demonstrates controlled drainage at Huronview Demo Farm. Images by Drainage Contractor magazine.

by JIM TIMLICK

THE INNOVATORS

Controlled drainage can accomplish some lofty goals. Can it do it on its own?

On Page 18, Mel Luymes and some of her LICO members alluded to a degree of automation that can be beneficial to controlled drainage. A new pilot project being conducted by researchers at The Ohio State University is looking to speed up adoption of controlled drainage through improvements to automated systems, which are considered less onerous to operate.

Automated drainage systems use sensors, solar-powered controllers and web-based software to monitor water levels and adjust built-in valves remotely through a computer or mobile device. The valves open or close based on real-time water level data, which helps ensure the water table in a field remains optimal

throughout the growing season.

The ongoing project is being sponsored by multiple sources including the Ohio Water Development Authority and the AgTech Innovation Hub, a joint collaboration between OSU’s College Food, Agricultural and Environmental Services, Nationwide farm insurance and the Ohio Farm Bureau.

The focus of the project is to study new, automated controlled drainage technology and how it could aid in addressing latesummer water deficiencies and reduce the loss of nutrients from the soil. For the project, Vinayak Shedekar and three of his colleagues have installed automated controlled drainage systems at four paired field sites across the state.

Each field site has both automated and manually controlled drainage systems installed side-by-side with the results being used as part of a comparison. The same farming practices are being used in each field. The study, which was launched two years ago, will look at a number of different variables including water table fluctuations, soil moisture fluctuations, subsurface drainage, water quality, crop respiration, and crop yield response.

The second phase of the project, which is being funded through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), was scheduled to begin earlier this spring. As part of it, 10 automated controlled drainage structures were installed last fall along the banks of a creek in Defiance County, OH. The purpose is to study the small watershed scale impact automated

In automated controlled drainage systems, solar-powered controllers open or close the system based on real-time water level data. Image by Vinayak Shedekar.

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DWR

controlled drainage systems can have on tile drainage discharge into the creek and how it could potentially impact nitrogen and phosphorus losses in the water.

Shedekar's hope is the study will provide evidence to convince growers controlled drainage is effective and doesn’t have to as burdensome a task as they may think.

Data from the Ohio Department of Agriculture and the U.S. National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) indicates that of the three to four million acres of farmland located in Ohio, only 30,000 to 50,000 of those acres has some form of controlled drainage.

Shedekar says many farmers are reluctant to use controlled drainage because manually controlled systems can be demanding on their time, cumbersome and labor intensive. Because drainage structures are installed between four and six feet deep, the pressure from the soil makes it difficult to remove or reinstall the boards that regulate the flow of water. As well, they are often located next to a ditch which makes them difficult to reach in the spring when that ditch is full of water. Doing so at 15 or 20 locations might not seem appealing to all farmers.

“Bringing some automation to the whole process is the future for this practice,” he explains. “Everything you can imagine on the farm has been automated in the last 20 to 50 years, except drainage outlets. Our drainage outlets look exactly the same as they used to 100 years ago.”

The beauty of automated systems is they can be opened or closed with the click of a button. That allows the operator to release water during heavy rains but also retain it for when crops need it during the dog days of summer in July and August.

THE MORE WE KNOW

Shedekar says it will likely require two or three more growing seasons worth of data before he and his colleagues can provide definitive analysis of the automated technology, but preliminary results have been interesting nevertheless. Comparisons using both manual and automated controls indicated that there was “a little more moisture retention” in the zone that had automated controlled drainage.

Shedekar says this will allow growers to be both reactive and proactive when it comes to controlling the water table in a field. Automated controls can allow farmers to retain as little as 1 to 1.5 inches of water, which can sustain crops for up to 10 additional days during drought periods and benefit crops, especially during their important reproductive stage.

“With the automated structure, you have the ability to look at the future forecast and make adjustments so that you can get a little more aggressive with it because you don’t have to go out and pull the boards out,” he says. “You can remotely control a valve at the bottom of that structure to release water whenever it gets too wet during the growing season. You don’t have that luxury when you’re trying to do it for manual structures.”

The first two years of data from the study also showed a corresponding crop response in the fields with automated controls. Photosynthetic activity was greater in these zones. Shedekar says that was likely the result of more moisture being available to plants when needed.

The OSU researchers are still analyzing data on yield impacts, and Shedekar says more time is needed to “crunch some numbers” before reaching any conclusions.

While a form of automated controlled drainage has been around in countries like the Netherlands since the 1980s, it’s still a relatively new concept here in North America. One of the commercially available systems in Canada and the U.S. is manufactured by Agri-Drain. It provides remote access to the system’s control structure via computer or mobile device. It also lets users see what the water level is in the structure in real-time.

But it doesn’t come cheap. A manual system costs between $3,000 and $8,000 including installation; an automated system can cost up to $15,000 including setup. “It’s a very high cost for a farmer to justify unless that one single outlet controls 25 or more acres. If it’s controlling 10 or 15 acres that’s a $1,000 per acre which is very high,” says Shedekar.

The good news for U.S. growers is that agencies like the NRCS offer rebates of up to 75 percent of the cost of purchasing and installing an automated system. Shedekar also points out that manufacturers are working on providing more affordable alternatives. Some now offer cheaper versions that can be programmed through an on-site control unit or via a phone app.

As useful as automated controlled drainage can be, the technology does have limits. It doesn’t currently provide any recommended prescription for water table management, meaning most users must endure some trial and error to start.

“Right now, that seems to be a big obstacle. If I zoom in on my field, I don’t have a prescription for my field as to when to set these boards, at what depth should I set my points, and when is it time for me to open the valve,” notes Shedekar.

“One of the things that is expected to be an outcome from our research … [is] we’re hoping to develop a decision tool that farmers can utilize to at least get some kind of a recommendation on how to manage these structures. Right now, they have to rely on experts or sales people from the country to give them prescriptions for how to manage them.” He would also like to see future iterations be more user-friendly. He says it took him nearly a year to learn how to operate one system. DC

Agri-Drain makes one of a few commercially available controlled drainage systems in North America. Image by Ben Reinhart.

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DWR

DRAINAGE WATER RECYCLING 101

Figuring out if drainage water recycling is right for you

by JESSIKA GUSE

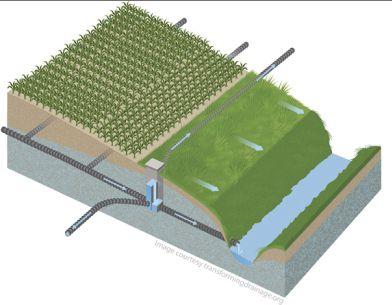

One of the many resources is dubbed EDWRD, which stands for Evaluating Drainage Water Recycling Decisions. It helps answer common installation questions. Photo courtesy of TransformingDrainage.org.

Drainage water recycling is still considered by some to be an up-and-coming water management system and conservation practice. But support for the strategy is growing.

Thomas Van Wagner, USDA-ARS staff with Lenawee County Conservation District, says the practice is "50 percent science and then it’s going to be 50 percent the art of managing it."

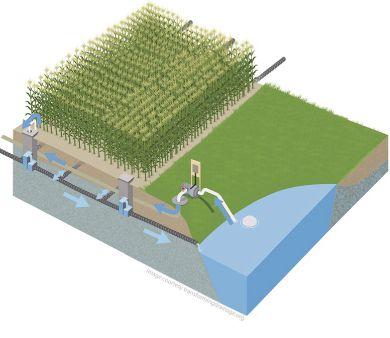

Drainage water recycling (DWR) is, in the most basic terms, any system that reroutes and/or saves drainage water – keeping it on the farm instead of immediately draining it – and then recycles it into an irrigation or subirrigation system. It’s worth noting that while these systems can be combined with controlled drainage (and often are), DWR is not, in and of itself, controlled drainage.

Being one of the developers for a system that debuted at the 2020 Michigan Land Improvement Contractors of America field day, Van Wagner adds they’re going to learn a lot from it in the coming years.

When it comes to tricks for this new trade, Bob Clark II, president of Clark Farm Drainage, points to automation. “This isn’t going to happen in a year or two, but ultimately, (I believe) in 10 years, because technology gets better all the time,” Clark says.

“A lot of these drainage water recycling systems can already be monitored and controlled remotely, at the farmer’s office on [their] desktop or on [their] laptop in the truck . . . I do believe with the right soil, and all the weather variability the farmer has, why not try to remove the guessing game as much as possible all while you’re improving water quality.”

RESOURCES AT YOUR FINGERTIPS

Transforming Drainage, a multi-state project looking at innovative and beneficial drainage practices, developed tools for contractors and landowners, which still exist on the TransformingDrainage. org site, to help them figure out if a system, like DWR, is right for them –like EDWRD, which stands for Evaluating Drainage Water Recycling Decisions.

“A lot of times, when you might be approaching a project, you know, one of the initial questions is, ‘well how big of a pond do I need? Or how big of a reservoir do I need?’ and so, EDWRD is a tool that runs a water balance for drained fields, as well as for a reservoir,” says Ben Reinhart, who served as a project manager with Transforming Drainage. The calculation estimates the amount of water coming from the field to the pond and it takes into consideration a range of different reservoir sizes that a user would input.

“Once it estimates the amount of water coming in, it can estimate how much can be stored in that pond and then goes one step further in terms of when it’s supplying irrigation, how much water is used from the pond, back up onto the field.”

It simulates the flow of water within a system to get an idea of:

• How much irrigation can I apply?

• How much tile drainage can I capture?

• How much can I capture and reuse?

Although the Transforming Drainage project concluded in the last several years, the TransformingDrainage.org site, including all free tools like EDWRD, remain available and open to the public to use. DC

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DWR

IN CONVERSATION: CHRIS HAY

Promoting DWR in the Midwest and beyond

by BREE RODY

A prominent researcher and educator in the Midwest, Chris Hay, independent water management consultant and former senior research scientist with the Iowa Soybean Association, has advocated for the benefits of DWR. He’s also a 2023 GroundBreaker and a frequent podcast guest with Drainage Contractor and other drainage podcasts.

“I came from water-short areas, where everyone argued over too little water, as opposed to too much,” Hay explained in his 2023 GroundBreakers interview. During his PhD at SDSU, which focused primarily on irrigation in the early days, he began to also look at questions about drainage, which was relatively new to South Dakota at the time. “As an engineer, I think I’m a problem solver, and when there’s a problem, I want to solve it.”

During his near-decade with the Iowa Soybean Association, Hay dove deep into his work on drainage water recycling. He found it exciting, because it combined his two areas of expertise. “There’s been this revived interest in capturing drain water and using it as irrigation,” he said, adding that there are benefits to water quality.

While DWR as a concept was not new, it “didn’t really enter the conversation” as a practice to promote until the formation Transforming Drainage – it “bubbled up to the surface” (pun likely not intended) as a strong practice that can benefit the environment and yields alike.

“In the Eastern U.S. and Canada, for the most part, we’ve got enough water to grow good crops, but it doesn’t always come at the right time,” he said. “Most years, there’s going to be some periods in

the summer where we’re a little short on water, and some extra water would help.”

There are many different configurations – any suitable site can simply have the water put back through the system. “[You] raise the water table back up below the root zone and let the crops access it that way,” he said. That requires closer tile spacing and works better on flatter fields, but is a plus because it doesn’t require a separate irrigation system.

Ideally, there’s a clay or restrictive layer somewhere below the root zone to hold the water. “But you don’t want too heavy a soil on top so that the water won’t move,” Hay added. “Probably, the idea would be something a little sandier, loamier on top.”

“The big one for the landowner is that increase in crop yield,” said Hay. Across the Midwest, studies have shown both an increase in yield and a decrease in yield variability, both in the field within one growing season, and year-to-year. “It makes planning a little easier.”

While these benefit the environment, Hay uses terms that should appeal to farmers: “Really, it’s a risk-management practice,” he said. He echoes the voices recommending TransformingDrainage as a resource, and for new info, recommends the Conservation Drainage Network.

“The big question now is when and where does it pay to make that irrigation investment for the farmer,” he said. Storage is a major investment, but Hay is excited to see what the future provides for funding opportunities. Considering the many downstream and ecological benefits, Hay says there is potential for these to be incentivized in the future. DC

Chris Hay has advocated for, and researched, drainage water recycling systems as a “risk management” practice. Photo courtesy of Iowa Soybean Association.

CONTROLLED DRAINAGE AND DWR

DWR IN ACTION: IOWA

Promoting DWR in the Midwest and beyond

by DRAINAGE CONTRACTOR STAFF

A new publication from the Iowa Soybean Association penned by Chris Hay and Iowa State University professor Matt Helmers has provided an update into the status of research on drainage water recycling (DWR) in the generally precipitation-heavy Iowa. The report, Drainage water recycling for crop production and water quality in Iowa, is available for free through the association. But beyond the emphirical data provided by the numbers, the report also provides real-life experience from producers using DWR on their farms.

Kellie and A.J. Blair, who grow corn and soybeans near Dayton, IA, are the participating landowners of one of the three new systems added to the study. The Blairs' system had been installed in 2022. The reservoir exists in a corner of their field, and can irrigate approximately 106 acres of land.

In a publication with Iowa State University promoting the new report, Kellie Blair said the couple is already experiencing the benefit of what Hay calls a risk management practice with DWR.

“We are already experiencing more unstable weather [in Iowa] and know this may become a greater concern in the future, so we wanted to be prepared,” Kellie Blair stated in the report. “We also had the chance to work with researchers interested in monitoring this kind of system in our area and thought that would be a good opportunity. We’ve only had one year of operation so far, so it will take some time to know how well it is going to work and pencil out.”

BEYOND PREDICTABILITY

The predictability of water availability amidst variable precipitation conditions is usually the first benefit one thinks of when recommending drainage water recycling. However, the new report emphasizes the water quality benefits of the practice –supported not only by science, but also by the Blairs' own experiences.

The Dayton site saw a 92 percent reduction of nitrogen per four site years. The site with the lowest reduction observed was 63 percent, at Lake City. More data on phosphorus reductions will be available as the observations and study continue.

DWR improves water quality by the nature of capturing and holding excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus back from flowing downstream into waterways. Those nutrients also have a better use on the field – thus, storage in the reservoirs can reduce concentration of the nutrients downstream but recycle them back onto the fields, through the irrigation systems, where they're needed.

In addition to the concentration of nutrients, some DRW reservoirs can serve as a habitat for waterfowl.

BENEFITS AND COSTS

“Drainage water recycling is not a new practice,” said Helmers in the report.

So why did it not take off? Cost was a primary concern, said Helmers.

“Early research in Iowa from the late 1980s and 1990s showed that these systems have promise," he said. It was simply due to the costs associated – Helmers said the practice became seen as something

that had "the greatest potential... for high value crops or areas where there were significant water quality concerns."

Helmers and other advocates, like Hay, see the potential for DWR increasing, with modelling suggesting the practice will become more profitable over time.

Of course, there are still upfront costs associated. Systems usually require new underground drainage lines in fields and some type of irrigation equipment. The construction of an on-site reservoir, as outlined by Hay on Page 22, is also a major expense. And, if a stream is impacted, permits will be required.

But the status report from the Iowa Soybean Association shows proof that the sites with crops irrigated with DWR systems had consistently greater yields than those from rainfed areas. The site in Iowa with the longest production record showed corn yields improved by about 35 bushels per acre on average.

While Hay says there are still "unanswered questions" before the official recommendation is to scale up DWR adoption, "the new report provides more evidence that these systems can deliver ‘win-win-wins’ for production and environmental benefits.”

Hay and ISA have been working with ISG on a feasibility assessment for four areas of Iowa. Several locations are being considered, and new funding proposals are being developed to support research. This work was supported in part by the Iowa Nutrient Research Center, Iowa Soybean Association and IDALS, with support from the EPA Gulf of Mexico Office. DC

DWR IN ACTION: BRIEF

Kelly Nelson, agronomist with the University of Missouri Extension, speaks at a field day where study results showed an increase in corn yield when using drainage water recycling. Image from University of Missouri Extension.

CORN YIELD RESPONSE TO DWR

A report from Transforming Drainage backs up specifically what advocates have been saying for years: drainage water recycling systems and controlled drainage not only provide a benefit to the environment, but can also improve corn yields.

Researchers found the systems helped to make yield more predictable, reducing yield variability by 28 percent over 53 site-years of work. The biggest increases were seen in dry years, when corn is most vulnerable. However, soil characteristics also play a major role in yield benefits of drainage water recycling – deep soils with high water capacities are less likely to be affected by short, dry periods, thus benefitting less from irrigation.

This increases the resilience of crop systems and improves food security, says Kelly Nelson, agronomist with University of Missouri Extension. The average yield increase of corn, compared to free drainage, was 19 bushels per acre. The study has been ongoing for several years across seven different Midwest sites. The benefits of drainage water recycling have been relatively well-known for some time – the act of saving excess water during wet seasons for later use during dry periods are known to help save on costs of water for irrigation, while also keeping nutrients from going downstream and preserving water quality – but new data also looks at the effects on crop yield. Researchers also found that yields gain most in the second half of vegetative development (nine-leaf or greater) to early grain filling (blister stage). They found no yield difference between free drainage and drainage water recycling before the V9 stage or after R2.

A combination of drainage and subirrigation also protects the environment by keeping nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus from entering downstream waterways, he says. That nutrient-rich water is recycled through irrigation.

Copy by Addison DeHaven, SDSU SDSU LOOKS CLOSER AT CONTROLLED DRAINAGE

Researchers in South Dakota State University’s Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering have joined the fray in those investigating the potential of controlled drainage – specifically, automated controlled drainage – as an answer to issues with yield and water quality.

“Controlled drainage has been around for a while and has proven benefits for farmers with tile drainage systems installed in their fields,” said John McMaine, an SDSU associate professor and the Griffith Chair in Agriculture and Water Resources. “Automated controlled drainage takes this technology one step further.”

Maryam Sahraei is a graduate research assistant in SDSU’s Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering. Her research seeks to understand how farming practices affect downstream water quality. “My research looks to improve water quality,” Sahraei said. “One of the biggest potential issues is that if outflow from

tile drainage contains high levels of nitrate, there is no buffer before this water enters a river or stream.”

According to previous research, controlled drainage has resulted in a 40 to 50 percent nitrate reduction in water being discharged into nearby lakes or rivers. However, Sahraei’s research has also found that nitrate loss varies across drainage outlets, from around 2 mg/L to over 60 mg/L. The research being conducted by McMaine and his graduate students on automated controlled drainage will take the technology one step forward by creating algorithms that will automatically let water go when drainage is needed, eliminating the guesswork and improving the system’s effectiveness. By utilizing real-time data, the system will utilize precision water management principles to use resources as efficiently as possible.

DRAINAGE WATER RECYCLING DONE

Turning site constraints into a first‑of‑its‑kind, multi‑benefit solution.

In Whittemore, Iowa, ISG partnered with local landowners, state agencies, and industry experts to recycle and treat tile drainage runoff from about 633 acres in Kossuth County Drainage District (DD) No. 9.

Challenge: Early fieldwork revealed a sand vein running through the proposed pool, along with property line restrictions and existing private tile mains that could not be disturbed.

Solution: ISG designed a unique tiered pond‑wetland system. A lift station will channel water into a 55 acre‑foot storage pond, enabling irrigation of nearby sandy fields. Excess water will flow into a lower wetland for nutrient treatment before entering the Lateral 6 Open Ditch.

From Excess Rain to Essential Irrigation

Drainage water recycling (DWR) helps balance when and how water is available for crops. Wetter springs and drier summers are becoming more common, creating both water supply challenges and water quality concerns. DWR systems capture excess rainwater and runoff often through tile drainage and store it in basins, reservoirs, or wetlands. During dry periods, that stored water is reused for irrigation at critical growth stages. This process keeps nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus in the field, improves soil and plant health, increases yield potential, and reduces strain on downstream drainage systems.

Discover the Full Potential of Drainage Water Recycling bit.ly/drainage-recycling-blog-isg

DWR IN ACTION: ONTARIO

Promoting DWR in the Midwest and beyond

By Mel Luymes

So, there are a lot of eyes on the Huronview Demo Farm, just south of Clinton, ON. The 47-acre silt loam field is owned by the County of Huron and, since 2015, it has been farmed by the Huron County Soil & Crop Improvement Association (HCSCIA) to demonstrate no-till and cover cropping in a corn, soy and wheat rotation.