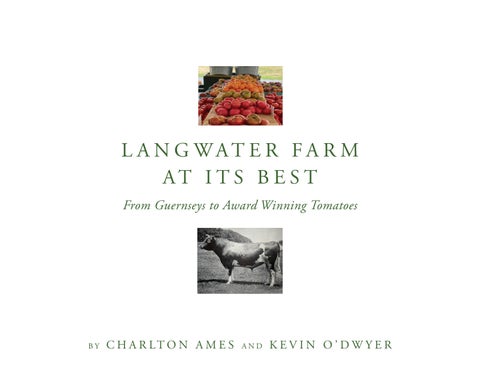

INTRODUCTION

From Farm Stand to Farmstore

The beautiful fall Sunday, September 18th, 2022 was a special day. It marked the day that ART shareholders and their families were invited to an open-house of the newly constructed Langwater Farmstore. Our farmers, Kevin and Kate O’Dwyer hosted the event with the help of Minnie, myself, and Noni. It was a time to celebrate. Kevin, with the help of a two man crew, had just completed the construction of a 7,491 square foot Farmstore in about eight months. He acted as his own general contractor at the same time the fields were planted and harvested. Farm stand sales were maintained from the original farm stand across the parking lot. That first farm stand project cost about $42,900 in 2010; whereas, the new Farmstore project of 2022 would ultimately cost close to $1.7 million.

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

1884-1960

The Guernsey Era

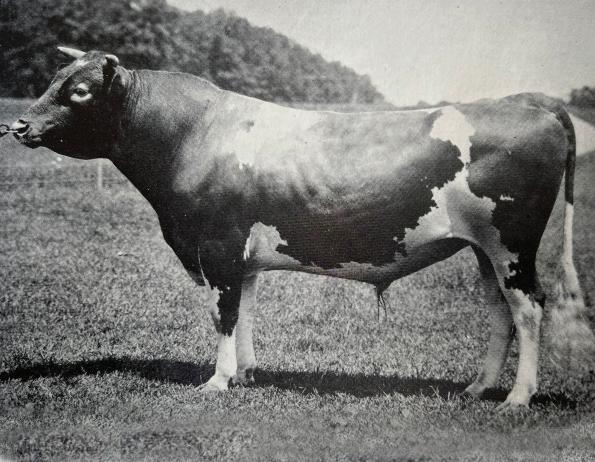

Contrasting today’s Langwater Farm with the Guernsey Era is pretty dramatic. Imagine what Grandpa would think to see rows of crops in his fields and busy farm hands attending those crops with all kinds of mechanized equipment. He would be wondering what happened to those beautiful and stately cows so peacefully grazing in the pastures? The cow barns would no longer exist and he would see Kevin’s gigantic compost operation where the bull barn used to be. His was a more leisurely time but still intense in its own way.

Guernsey cattle at Langwater go back to Grandpa’s father, Frederick L. Ames, who started the herd as early as 1884 but it was his son and Grandpa’s older brother, Lothrop, who took on the task of building a herd according to the laws of heredity. Lothrop purchased his first cows in May, 1901, and with the help of Edward Burnett, Lothrop selected the foundation herd. In 1902 he bought Imp. King of the May for $2,000 which was then a big price. It proved to be an inspired purchase because sixteen daughters of Imp. King of the May sold for $31,500 in 1916 at an average price of $1,968 per head. At his death in

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

1901

Lothrop Ames selects the Foundation Herd

1884

Frederick Lothrop Ames introduces the Guernsey to Langwater

1921, Lothrop was the most famous breeder of Guernsey cattle in the world according to Louis McL. Merryman who wrote the “Langwater Story” for the Guernsey Breeders’ Journal. The 1922 dispersal sale held for Lothrop’s estate generated a huge amount of interest. Ninety six head were sold for $262,930 for an average of $2,738 per head. Langwater Cleopatra brought the top price of $19,500 which was quite something for 1922. During his twenty years of developing the herd, Lothrop registered two hundred and six bulls and three hundred and forty four cows. He sold his best seed stock to other breeders. This meant he improved Guernsey herds from Iowa, Wisconsin, California, Massachusetts, and even back to the Island of Guernsey.

Lothrop might have died in 1921 but his work was to go on. Grandpa (John S. Ames known as “Jack”) took up his brother’s work by buying thirteen head from the 1922 dispersal sale. He paid tribute to his brother by becoming the foremost Guernsey

1922

John S. Ames continues Lothrop’s work

1921

Lothrop Ames dies at forty-four years old

breeder of his day. Grandpa followed Lothrop’s basic plan so that the broad genetic base of the herd did not change from one brother to the next. The goal was to economically produce Golden Guernsey Milk with better cows and that is what Langwater Farm did.

Grandpa was a quiet and talented man. He loved his collection of azaleas and he was a student of genetics much like his brother. He could not see the animals bred by Lothrop “dispersed to the four winds” and so he acted. Fortunately for Grandpa he had married Nancy Filley in 1909. She was a gracious hostess and she had a keen eye for the best cattle. They made a formidable team at auctions and as breeders.

Let’s go back to June 6th in 1930. This was a time when Langwater Guernsey cattle were well established and Langwater was viewed as being at its best. Grandpa and Grandma picked a beautiful day in June to host an outing for breeders devoted

1930-1960

at its Best”

to the advancement of the Guernsey. Lunch was served under a tent on the lawn and guests were greeted with a souvenir pamphlet which gave the name, date of birth, sire, and record of every animal on the place. The animals were numbered so that guests could go into the pastures and check the number of the cow with that in the pamphlet. The manager, F. C. Shaw, assisted the guests to identify particular animals. Guests had an opportunity to visit the bull barn, not too far away, and the day was considered a great success.

This was a busy time for Langwater (1930 – 1959). Multiple events were held for the Guernsey Breeders’ Association. In 1940 twenty eight head sold for an average of $1,821. Langwater Charm fetched the highest price at that auction ($4,500) due to her especially good udder. There were sales in 1947 and again in1954. The 1954 sale brought in $58,550 from thirty five head and included buyers from many states as well as South America. Grandpa and Grandma held a luncheon for a potential buyer, Antonio Pradilla from Bogata, Columbia. I

remember the day well because it was an opportunity for me to spy on the fancy lunch. Unfortunately, Mr. Pradilla had bodyguards who discovered me prowling the grounds and I was lucky to escape unharmed from Langwater that day.

Grandpa died in the summer of 1959. His will required the sale of the herd and his executors did just that with a dispersal auction in 1960. One hundred and thirteen head sold for $187,725 ending fifty nine years of breeding supremacy. Over that period Langwater was the source of the breed’s best blood. The family had used their ability and resources to build the Guernsey breed but not without help. Tribute was paid to F.C. Shaw manager, twenty seven years; Joe Nagle herdsmen, forty five years; Arthur Heath, thirty nine years; Archie Freeman, forty three years; William Marshall, thirty eight years; Lorimer Mac Donald, thirty five years; William Chesley, twenty years; Richard Greene, twelve years; and Mrs. Mildred Moore secretary, twenty nine years of employment.

“Langwater

1959

John S. Ames dies 1960

The final dispersal sale

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

The 1960 dispersal sale was financially disappointing. Some say it was because of competing Guernsey sales. However, one wonders if Golden Guernsey Milk was on the decline because the consumer was becoming more health conscious. There was another factor which might have worried Grandpa.

Guernsey cows were having trouble competing with Holstein cows. Top producing Holsteins, milked three times a day, could produce seventy two thousand pounds of milk a year. What did it matter that Golden Guernsey Milk had twelve percent more protein and thirty percent more cream than milk produced by Holsteins? The industry started to go with volume. Today there are only slightly more than six thousand Guernsey cattle registered in the U.S. as compared to about nine and one half million Holsteins. Nine out of ten U.S. milk producers now milk Holsteins. Yet, back in 1960, the sale was well attended with over five hundred people paying tribute to Langwater. The one hundred and thirteen head sold went to forty five buyers from nineteen

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

1969

Ames Realty Trust (ART) is founded

1974

United States Post Office buys 1.5 acres

1968

Nancy Filley Ames dies

1973

John S. Ames Jr. dies

states and Canada. I was there that day along with many of my cousins who would later become ART shareholders.

At the 1960 sale Grandma is pictured with her four children who would become the original four trustees of ART. Aunt Bun (Mrs. David Ames) sits with Aunt Becky and Grandma in the front row. Their expressions are somewhat muted and it must have been the start of a sad period particularly for Grandma. The fields were now vacant and the buildings that housed the cows and bulls would start to come down. Between 1960 and Grandma’s death in 1968 it must have been decided to create the Ames Realty Trust (ART) with empty pastures surrounding the estate. ART was limited to approximately 91 acres of woods and fields forming a protective collar of preserved land around the main house and the Lodge.

1983

Rebecca Ames Thompson is bought out of ART

1991

David Ames dies

1997

United States Post Office buys 0.73 acres

Photo needed: The Staff photo

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula. Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna.

Photo needed: Grandma is pictured with her four children who would become the original four trustees of ART.

2004-2009

ART

As of 2004, Uncle Oliver remained the only original trustee. He still was our President and patriarch but it became clear that the next generation should start to be more active. David Ames Jr. and myself were now the co-trustees so we began to try to be helpful. David’s first contribution was to help Uncle Oliver develop a more active relationship with NRT. It was hoped that NRT could take over maintaining the fields after the death of John Marshall. There was the belief that growing hay could make money if we improved the soil by liming, fertilizer, and/or possibly cover crops. NRT proposed using Bridgewater correctional crews to clear brush from the walls along Main Street and Washington Street. NRT proposed the clean out of drainage ditches, rehanging of gates, and other services. Unfortunately, NRT needed to be paid more than ART could afford so the initiative broke down. David responded by looking for alternatives. He proposed using Charlie McNamara for haying and he made contacts to sell more hay. He arranged wall clean up with Pat Raymond and keeping the roads mowed with Dave McNeil and Jack Mowatt.

Then in 2007 Uncle Oliver died. His loss was a big blow at ART and the family. The next generation had no choice but to take over. We had become eleven shareholders with the addition of Aunt Esther, Olly, Minnie, Sam, and Abby. I conducted a shareholder Opinion Survey in 2008 so that shareholders could become more active in decision making. Here is how the survey helped to sharpen our thinking:

1 Exploring opportunities for ART land became a greater priority with particular emphasis on the Route 138 field.

1 Balancing the budget became imperative.

1 We recognized the need to seek outside help.

1 Keeping control of the property remained a high priority but shareholders were open to selling development rights.

1 Agricultural uses were attractive but improving the soil without a plan was too expensive.

David Ames was now ART’s president, replacing Uncle Oliver, and he continued to develop earlier contacts such as Sarah Kel-

2007

ley of the Southeastern Massachusetts Agricultural Partnership Inc. (SEMAP). Sarah did a good job providing ART with soil tests focusing on ph and organic matter. There was no doubt that ART could improve the quality of its fields but for what purpose?

It was then that David contacted Bob Bernstein of Land for Good. They didn’t provide market research but what they did do was put together young farmers, without land, together with land owners who needed a use for their land. We knew the Farm to Table movement was gaining traction in the northeast and the timing seemed right. ART had the land but not the skill to farm it. Land for Good told us that they could find the right farmer for ART and they did.

However, attracting the right farmer was not an easy task. ART had to be practical about its goals and clear about what could be offered to prospective farmers. Retaining ownership of the land was a given, but all other aspects of the land were on the table. Land for Good wanted us to consider: vehicular access and parking; commercial/retail development; housing

units; aesthetics; the woodlot; and a barn location. We did all of that and at last a Request for Proposal was ready for the candidates. We had six finalists. There were four selection criteria: the person, the business, compatibility with ART goals, and compatibility with the land and community. The candidates were all very different in terms of skills, personality, and background. Our due diligence was uneven but we had enough information to move forward and select Stone Soup LLC.

I still have a copy of the Stone Soup LLC Business Plan dated April 26, 2010. It was submitted by Rory O’Dwyer, Alida Cantor, Kevin O’Dwyer, and Kate O’Dwyer. The plan is only five pages long but it tells a compelling story from a Summary of Resources to Finances at the end. I was impressed by Kevin’s over fourteen years of experience at Ward’s Berry Farm. Rory and Kevin were to be the primary full-time farmers and they recognized the need for a well thought out marketing plan. Emphasis on Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) or the sale of CSA shares for working capital made a lot of sense. Their mission statement supported all the right goals including “We want to contribute to our local community by providing

Oliver F. Ames dies

2009

Stone Soup is selected by ART 2010

The farm stand is built

2012

Langwater Farm barn is built 2022 The Farmstore is built

good food and a beautiful place to visit. We want our community to support us and value us as an asset”.

Developing the ART/Stone Soup Relationship

The lease agreement dated September 1, 2009 and subsequent leases document ART’s relationship with Stone Soup. The importance of being able to use the farm house at 183 Elm Street is on page One. Use of the fields is set at a low fee which recognizes the fact that farming requires inexpensive land. ART’s compensation comes from participation in the retail sales which do not include pick-your-own operations, CSA sales, or other contractural Stone Soup customers. The rationale for this arrangement was that ART provides an attractive retail location for walk-in customers and should be compensated by those retail sales. Permitted uses of the property are broadly drawn to allow for normal activities associated with farming.

“Maintenance, Repairs, and Improvements” is an important part of the lease because it documents how improvements will be handled including building the new farm stand or barn. Stewardship standards are documented but they are hardly an issue because ART and Stone Soup are closely aligned about

how to treat the land. Drafting the lease was a big effort aided by a template provided by Bob Berenstein of Land for Good. ART was represented by Olly, David, and Minnie. Stone Soup was represented by Rory O’Dwyer, Alida Cantor, and a Vermont lawyer named Annette Lorraine. Olly guided the process of creating a lease which has stood the test of time and anticipated almost all issues which have confronted ART and Stone Soup.

Early on we recognized that all shareholders could not be allowed to interact freely with the farmers. Our idea was that communication with Stone Soup had to be done in a thoughtful and efficient way to avoid chaos. The solution was to create a liaison position between ART and the farmers in order to create a long-term relationship coming from one voice. We needed a person who could engage the farmers in an on-going dialogue that respected boundaries as well as the relationship of landlord to tenant. That person was Minnie Ames who took on the ART liaison role in 2010 and she has held that position to this day.

Another key to building a successful relationship was to bring in professional help. ART engaged landscape architect, Stephen Mohr of Mohr & Seredin to help layout and plan for the new farm stand. Stephen was entertaining and bright. He guided Stone Soup and ART through a complicated process. He worked well with Kevin as we considered location, how to allow access for vehicles entering and exiting the property, an expanded area for CSA pick up, visibility from Route 138, electrical service to the farm stand as well as water supply for produce wash-down. Everything had to be considered with an eye to expansion and in accordance with requirements of the Easton Planning Board. Thanks to Stephen, ART and Stone Soup worked together and successfully navigated the process.

Stone Soup’s willingness to trust ART also helped to build the relationship. The first lease went only five years from 2009 to 2014. Stone Soup made investments, such as planting fruit trees, with no hope of making a return unless the lease was extended. Every day Kevin made decisions that would have consequences beyond the lease term and ART appreciated his eye towards the future. In the second year of operations Kevin made the case that, with a long -term lease, major decisions could be made. He wrote a 2011 memorandum for ART entitled “Stone Soup LLC’s future vision based on different lease lengths”. He was already thinking beyond the first five -year lease to one being extended by thirty plus years. Kevin’s 2011 road map of improvements has largely been accomplished with the exception of a glass propagation house and the lease has been extended to December 31, 2043.

The 2011 memorandum was clairvoyant and comprehensive because it included “Life plans and personal factors”. Kevin and Kate wanted to earn financial security through retirement age and relocate to Easton with their family. With the opening of the expanded Farmstore, most of Kevin’s physical wishes, belonging to infrastructure development and buildings, had been accomplished but the non-physical wishes were still a work in progress. Those wishes are important. For example, we should be concerned about career development and financial security for Stone Soup and their employees. Is it possible that Langwater Farm could initiate a development program for young farmers who might work for Stone Soup but then go on to contribute to other farms? This would be analogous to the way Lothrop and Grandpa sold their best seed stock to other breeders in order to uplift the whole dairy industry?

Sale of 183 Elm Street to Kevin and Kate

Art and Stone Soup had successfully collaborated on the building of a barn in 2012. Stephen Mohr again provided the siting and circulation plan. Then about 2015 Kevin approached Fred and myself about purchasing 183 Elm Street. By that time Rory and Alida had moved out of the house. It had been cleaned, and lead paint removed so that Kevin and Kate were living there with their young daughters. ART understood why Kevin and Kate would want the security of home ownership so their request could not be ignored. However, it was a difficult request. The rental income from 183 Elm Street had been ART’s only consistent source of revenue since inception. Some of us regretted selling off the land to the US Postal Service and the idea of selling more property was not easily endorsed.

We thought that perhaps ART could help the O’Dwyers to purchase a house other than 183 Elm Street but this did not seem wise because we would be removing them from the property and; therefore, we would be making it more difficult for them to farm. Could a long-term lease with low rental rates and broad rights to change the house demonstrate that they would be better off financially not owning the house? Yes, but this would not make up for the satisfaction of home ownership.

The way we ultimately moved forward was to think about mutual benefits. ART had struggled keeping tenants and upkeep of the property was never easy. Kevin had proposed to renovate the house to make it a better living environment for his family and we could see that Kevin’s renovations would be an upgrade for the house. ART would benefit if we could take back the house after Kevin and Kate no longer needed it. Stone Soup would benefit by having Kevin and Kate living in a house adapted to their needs and if they were compensated for renovations.

The solution to selling 183 Elm Street was a buyback provision. The Buyback Provision allows Art to repurchase the property at an amount equal to Kevin and Kate’s purchase price, adjusted by the percentage change in the Standard & Poors Case-Shiller Index for Boston-area real estate, plus the depreciated value of the renovations made by Kevin. Unlike a “right of first refusal,” ART will be able to calculate exactly what is owed to Kevin and Kate. The funds generated by the sale of 183 Elm Street have been put to work with the help of Reynders McVeigh Capital Management so that when the funds are needed they should be ready.

The Future

At this point in the story let’s pause to consider what Stone Soup has accomplished by farming Grandpa’s pastures.

Art expected that Kevin would be an excellent farmer. After all, he had a track record of over fourteen years of experience working at Ward’s Berry Farm. We thought he would need a significant amount of acreage and we weren’t surprised by his impressive composting operation so that Langwater Farm could be certified “organic”. It wasn’t surprising that Stephen Mohr could come up with a sophisticated site plan for a modest farm stand. However. the surprises started to happen when ART realized that Kevin and Kate were moving much faster than we believed possible. ART knew that gaining community support was a Stone Soup goal but we thought achieving support would be difficult and take time. This was not the case. With hindsight it seems that Kevin and Kate knew all along how to attract community support. They sold CSA shares with skill and in extraordinary numbers. They handled the logistics of CSA pick-ups and encouraged customers to come back more

often for seasonal treats such as apple cider donuts and signature crops such as strawberries and tomatoes.

We didn’t imagine That Langwater Farm could generate community excitement but it did with a series of events such as: Pizza Saturday, a Winters Farmers Market, a Summers Farmers Market, a Spring Food Festival, a lobster truck, a Blanche Ames Elementary School Day, pick-your-own tulips, pickyour-own pumpkins, and of course hay rides are all part of the fun. There must have been mistakes along the way but none have been visible. Kevin knows how to make farming exciting. Stone Soup’s newsletter often describes what the farmers do from day to day. For example, “March is here, which means it’s time to seed in the greenhouses – Go little seeds, go!”.

The Langwater Farm shopping experience deserves a special mention. It starts when drivers are attracted by beautiful crops and flowers being grown in the Washington Street field. They become customers when they drive in to be greeted by attrac-

2023–?

tively displayed produce and friendly employees providing assistance. In the early years this happened at the farm stand and now it happens even more so at the Farm Store. Customers sense the are in a welcoming place where employees enjoy their work. The informal atmosphere rubs off on customers and they don’t mind standing in line or they might even socialize with one another.

Retail success has brought on the need for more produce and therefore more land to farm. ART’s acreage was not enough and had to be supplemented. The Town of Easton helped out by providing acreage at the historic Wheaton Farm. The Wheaton Farm’s distance was a challenge which Kevin has overcome. More land and fewer rocks has made the Wheaton Farm effort worth it. In addition, the Olivers have graciously provided more land at the much more convenient Marshall Farm. All told Stone Soup now farms close to eighty acres or roughly twice the amount of farm land available at ART.

Looking to the future, one has to make simplifying assumptions. I am assuming that Kevin will be able to farm with

Kate’s help and run Langwater Farm for many years, perhaps thirty. ART will be reorganized in 2027 and leadership will be passed to the next generation. This assumption is not too difficult to make because the Olivers are so much younger than the rest of us. A third assumption is that the Ames Family will successfully develop a comprehensive plan for ART, Langwater Estate, and the Marshall Farm. If the above assumptions are valid, then Langwater Farm can play a synergistic role bringing all three Ames properties together. The Stone Soup events could be expanded to include all three properties. Demonstration projects, to support farming in the Northeast, could attract collaboration from various institutions. A wide variety of vendors are being attracted to Langwater Farm and that list could be greatly expanded. The Farm Store could be used as a model to help other farming operations. It was designed to enhance the customer experience but also to help employee efficiency and job satisfaction. Kevin’s ability to inspire young farmers and immigrant workers could be harnessed in several ways. Farming is exciting and I believe ART is willing to embrace opportunities with the help of Stone Soup.

Modern Day Photo

BY KEVIN O’DWYER

Modern Day Photo

BY KEVIN O’DWYER

From Pasture to Retail and Row Crops

After signing the initial lease with the Ames Realty Trust in September of 2009, we (Stone Soup) were excited to break ground and begin our new farming venture on the beautiful former pastures of historic Langwater Farm.

Fall planted garlic would be the first crop to go in. We took soil samples to assess the pH, organic matter, nutrient levels, and other soil qualities. The soil test results showed the pH in the range for vegetable production with slightly low organic matter and elevated levels of calcium and magnesium, likely from recent heavy applications of dolomitic lime. Nitrogen and potassium levels, along with some micronutrients, were low- perhaps from hay crops being taken off the land without returning much nutrition for decades since the cows’ manure had fertilized the pastures. Invasive weed species such as horsenettle and quackgrass had also crept in over the years. Informed by the soil test results and soil surveys from the USDA we knew we had work to do to improve the soil, remove the abundant rocks that filled the fields, and return the land to productivity. In the infancy of our farm business, we had precious little

startup capital and nearly no equipment. Without a tractor and needing to get the garlic stock planted, we hired an old Langwater friend, Charlie Mac, to till the soil in October 2009.

Charlie opened up two acres in the Washington St. field and two acres in the Post Office field with his disc harrow. After picking some rocks into the bed of our “new to us” pick-up truck, we set up string to mark out beds, hand-casted some fertilizer, and hand-planted three beds of hardneck garlic into the boney, coarsely prepared soil. The volunteer crew included Kate, her friend Michele, my mother, and myself. That sunny October Sunday was a monumental day for our young business and the beginning of a new era for Langwater Farm.

The winter of 2010 was a busy one. There was much work to do to develop a more detailed business plan, create a vision for the farm, plan the upcoming season’s crops, and apply for organic certification of the fields and operation. There was also the challenge of transforming the raw farmland and future retail site along Washington St. into a productive farm and

viable business and building the critical infrastructure needed to support it. Our limited start up capital was woefully inadequate to do all this and we needed to raise funds immediately. For this we turned to our family, the community, ART, and Farm Credit East.

My mother graciously offered to lend us upwards of $10,000. We appealed to the community through the CSA model, marketing shares through Facebook and our new website. We were overwhelmed by the response and support from the community. New to the community, we were complete strangers to the people of Easton yet somehow we compelled over fifty families to purchase crop shares for the upcoming season totaling close to $30,000. We used this capital to purchase our first tractor down in Lancaster County, PA along with some essential tillage and mowing equipment. We procured and erected our first greenhouse, to propagate our seedlings for transplanting in the fields, and acquired an irrigation pump, various growing supplies, and fertilizer.

ART offered a loan at a very reasonable interest rate to fund the installation of a new driveway and parking area for the retail area off Washington St. The promissory note funded much of the nearly $18,000 cost of the new driveway and parking area and the work was completed by the Easton excavation company, Endriunas Bros in May 2010. Daily expenses and money for the little labor we could afford during those early months was covered by a $10,000 revolving operating line of credit provided by FCE.

The stoney fields, rife with invasive species, lacked fertility. However, this was a challenge we understood how to take on. Armed with our newly acquired tractor, equipment, and our strong, young backs we tilled up an additional acre for crops at the top of the Main St. field and beat back the invasives where we intended to plant with heavy tillage, mowing, and hand removal. We laboriously picked and stockpiled hundreds of yards of stones from the fields by hand. We spread compost brought to us by the Easton DPW and amended the fields with fertilizers as directed by our soil test results. By late April we were ready to plant the first annual crops of the season. Beets, carrots, radishes, and greens were direct seeded by an inexpensive walk behind Earthway Seeder while broccoli, kale, and cabbages were transplanted as we crawled across the fields on our hands and knees. By late spring, summer crops like peppers, eggplant, and tomatoes were going in and it was starting to look like a real diversified vegetable farm. Although we lacked much mechanization and the work was grueling at times, we felt a great satisfaction and sense of accomplishment as we brought these first crops to harvest.

While the improvement and planting of the agricultural fields was familiar to us, the work to carve out the retail site and build the infrastructure was far more daunting and less familiar. The land aroud the site was raw with no access from the street and no water supply, electricity, or other utilities. It would be a difficult and messy endeavor to reclaim the land and make way for the Farmstand, driveway, and parking area. Through the winter and early spring we spent much time cutting and clear-

ing away thick, nasty vegetation such as poison ivy, bittersweet, and devil’s walking stick. The dense brush was mixed with rusty barbed wire, jagged iron fence posts, and old rubble foundation walls from what was a former homestead. Equipment access to the site had been restricted by the dense growth and lack of maintainence for what appeared to be decades. Once the unpleasant work of clearing the land at the retail site was complete, the excavation work for the road and parking could commence. With the last of our quickly dwindling capital, we were able to pay for a water and electric service for the site. By June, we were barely able to afford the purchase of four $150 pop up tents to start selling and distributing our first harvested crops from under. The tents would serve as our temporary farmstand until we had earned enough revenue to purchase the materials for something more permanent.

Minnie had been an excellent choice to serve as the liaison between ART and Stone Soup. Minnie’s acumen and her thoughtful and genuine personality made her a great fit to navigate town and state regulations and interface with local officials and Stone Soup members as we went through the planning process. We felt she shared many ideals and had common goals for the farm and we trusted her and what she represented as the ART’s intentions. It was largely due to this important relationship that we were emboldened to invest our time, sweat, and capital in a long term vision and devote ourselves wholeheartedly into developing the farm. We trusted that if we executed our plan and proved ourselves capable, Stone Soup would be rewarded with a long term lease extension and an opportunity to grow our business. We planted close to seventy peach trees that spring, with a minimum five year ROI, and later that sum-

mer had generated enough capital to further invest in the site, purchasing lumber and materials and beginning construction of the original Farmstand. We completed the building around Labor Day and hosted the community in the fields for pickyou-own pumpkins through the autumn season.

Our first year in business had gone as well as we could have hoped for. The crops yielded fairly well and ART and the community was supportive and encouraging. We were ready to grow the business and were very fortunate that winter when we applied for and received a matching grant award from the MA Dept of Ag for equipment. The grant was for $10,000 and with our match we were able to afford three critical pieces of tractor drawn equipment: a precision seeder, a plastic layer, and a transplanter. These pieces of equipment served as a springboard for our vegetable production. Our days of crawling on our

hands and knees transplanting crops would be fewer. Anticipating the capacity to produce more crops, we sold more CSA shares to the community hungry for local, organic food. The additional revenue generated allowed us to also purchase and construct a second propagation greenhouse and two unheated high tunnels in the winter of 2011 to support the expanded production. With the equipment and greenhouse to produce transplants in, we were able to jump from five to fifteen acres in production.

Our family was also starting to grow alongside the business. In February of 2011, Kate and I celebrated the birth of our first daughter, Madison. Kate would leave her job in social work the following year to join the farm full time and manage the Farmstand and assist with administrative duties.

Modern Day Photo Modern Day Photo

Modern Day Photo

By the end of 2011, the business was growing rapidly and there was a glaring need for additional infrastructure. We desperately needed a barn to house supplies, equipment, and tools. ART again supported our eagerness to grow the business by extending the lease and offering access to timber in the farm’s woodlot for constructing the barn. In coordination with Minnie and the forest manager, Phil Benjamin, two stands of red pine were selected for harvest. The stands of red pine were ideal for the situation. The red pines were likely planted around the 1930’s and 40’s - perhaps by the herdsman, John S. Ames, and perhaps related to or inspired by the conservation efforts of Roosevelt’s New Deal - and are not native to southern New England. As with many red pine stands that were planted in southern New England around that time, the trees were in decline with several already dead. We were able to harvest close to forty red pines

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

that were still in good condition and mill the timbers on site into posts, beams, and boards to build the 3,200sqft barn. We completed the construction of the main building in the spring of 2012.

We expanded production and acreage again in 2012. We were now utilizing nearly all of the tillable acreage at Langwater, totaling close to thirty acres in organic vegetable and fruit production. At this point, to continue to grow the business and meet the demand for local, organic produce we would need to access more land. It had felt like much longer but in three seasons historic Langwater Farm had gone from idle pasture lands to cultivated row crops and again being a food source for the community. However, this time the golden Guernsey milk had given way to organic fruits and vegetable.

Modern Day Photo

BY CHARLTON AMES AND KEVIN O’DWYER

BY CHARLTON AMES AND KEVIN O’DWYER

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

Pellentesque tempus ut libero quis consectetur. Aenean in nisi interdum, faucibus sem nec, tempor magna. Integer nulla nisi, mollis eu auctor quis, feugiat posuere ligula.

Modern Day Photo

BY KEVIN O’DWYER

Modern Day Photo

BY KEVIN O’DWYER