FALL 2020

STORY BY ANNA WATERS

PHOTOS BY NIK LAYMAN AND STEVE WOOD

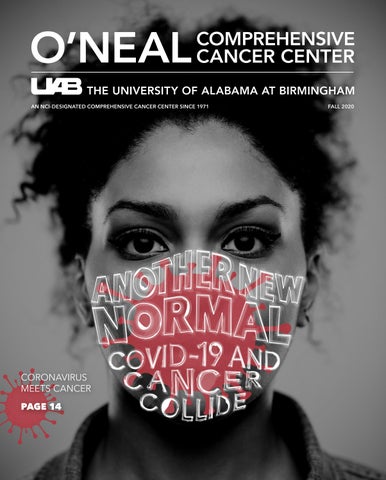

“IT’S HARD ENOUGH TO TRY TO MAKE SURE THAT I’M ADOPTING THE RIGHT SAFETY PRACTICES SO THAT I WON’T HAVE A RECURRENCE. BUT NOW, ON TOP OF THAT, I HAVE TO BE CAREFUL THAT I DON’T GET COVID-19, SO IT’S JUST A LOT.”

MARIE SUTTON O’NEAL CANCER CENTER PATIENT AND SURVIVOR

The surgery removed 30 of Sutton’s lymphnodes, requiring her to now wear a compression sleeve to protect her right arm.

Sutton works as the director of marketing and communication for the UAB Division of Student Affairs, but she is also a patient at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB.

“It’s hard enough to try to make sure that I’m adopting the right safety practices so that I won’t have a recurrence,” Sutton said. “But now, on top of that, I have to be careful that I don’t get COVID-19, so it’s just a lot.”

Once her blood work was done, Sutton made her way back to the parking garage, noting a set of additional temperature check tables and the lines of patients forming behind them.

For Sutton, the familiar rituals she’d grown accustomed to during her cancer treatment had changed, now replaced with new rituals to defend against a different enemy.

“Before, I could walk through The Kirklin Clinic with my eyes closed because I was on every floor, every time, every day,” she said. “It was like the ‘Cheers’ bar. Everyone knew my name because I was there all the time.

“Now, everything has changed, including certain entrances and exits. There were chairs facing in opposite directions so you wouldn’t be in the breathing stream of someone else. It was very different, but I believe that they are good changes.”

Sutton admits she was nervous about visiting The Kirklin Clinic during a pandemic, but she trusted her care team at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center and says she even felt a sense of relief to see the measures that UAB had taken in response to the state’s rising case numbers.

“Leading up to my surgery, I had to go to The Kirklin Clinic a lot. So just knowing that I would be back in that environment, where it was wall-to-wall with sick people, and knowing the potential of getting COVID-19, that was very nerve-wracking,” she said. “But luckily, as soon as I got out of the car, there’s the temperature gun guy, there’s hand sanitizer everywhere, and I’m always booted up with a mask and everything so that I’m protected.”

CANCER NEVER SLEEPS

For the majority of O’Neal Cancer Center patients like Sutton, who are now facing the threat of COVID-19, care can’t stop, global pandemic or not.

The same is true for many people across the country who receive their cancer diagnoses from routine cancer screenings. Without regular screenings, a lot of these patients might not discover they have cancer until it is too late to effectively treat it.

However, some are now forgoing their treatments and routine cancer screenings out of fear of contracting COVID-19. In an editorial published in Science in June, National Cancer Institute Director Ned Sharpless, M.D., explained that this fear of becoming infected with the virus in a clinic, hospital or other health care setting has discouraged many people from getting treatment and preventive care for diseases other than COVID-19. Models from the NCI also suggest that these delays will result in nearly 10,000 excess deaths from breast and colorectal cancers alone over the next 10 years.

“ Even a short-term delay in screening and care can lead to more deaths,” said Barry Sleckman, M.D., Ph.D., director of the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB. “A missed diagnosis of cancer now can pose a bigger problem later if it progresses to a later stage, leading to a worse prognosis.”

Because screenings can detect cancer at the beginning of its progression, patients who get screened are able to be diagnosed earlier and, therefore, have the opportunity to begin treatments that can curb, or even cure, their cancer sooner.

Sleckman says that this is why the O'Neal Cancer Center has spent the majority of the pandemic fighting to continue providing patients and the public with safe access to preventive care and cancer treatments, including those that are offered exclusively through clinical trials.

“ We have done everything to ensure the safest environment possible for our patients, and we are continuously urging patients to talk to their providers and get the care they need,” Sleckman said. “We realize some cancer treatments can safely be delayed, while others simply cannot.”

Marie Sutton, M.A.

“WE BELIEVE THAT, WITH THE RIGHT SAFETY PROTOCOLS IN PLACE, WE CAN ASSURE OUR PATIENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES THAT THEY ARE SAFE TO COME TO UAB FOR CANCER CARE.”

JORDAN DEMOSS, MSHA CANCER SERVICE LINE VICE PRESIDENT

SAFETY FIRST

Sutton’s home is in Birmingham where UAB is only a five-minute drive away, but while visiting The Kirklin Clinic for her cancer treatments, she realized she was often one of the only oncology patients there who lived nearby.

“There are people who come from surrounding states to get their treatment at UAB because UAB has really great cancer care,” she said. “But not everyone along the way, and not every location along the way, is taking the same precautions that UAB takes.”

Sutton says she knows that, for many patients who travel from outside of Alabama to UAB for cancer treatment, the potential risk of exposure to COVID-19 is much higher while they are on the road than it is for those who live nearby, especially if those out-of-state patients have compromised immune systems.

“You are vulnerable until you make it into the arms of UAB,” she said.

According to the American Cancer Society, people with cancer face an elevated risk of developing infections in general, especially those who are receiving treatments that can further weaken their immune systems.

“For example, chemotherapy and radiation therapy are used to kill cancer cells, but they can also kill healthy white blood cells, making some of these patients more vulnerable to infections,” Sleckman said. “So do immunosuppression drugs, which are often given to transplant patients to keep their immune systems from rejecting their new organ, stem cells or bone marrow.”

For these patients, Sleckman says that public health measures, such as social distancing, hand hygiene and, most importantly, universal use of face masks, are the first line of defense against potentially lethal diseases, COVID-19 or otherwise.

“Many of our patients at the O’Neal Cancer Center can have weakened immune systems, and so they can have a harder time fighting off infections,” Sleckman said. “This is one of the reasons why we are taking so many safety precautions in the clinic and the hospital to protect these patients from germs and viruses that can cause things like pneumonia or COVID-19.”

As Sutton noted during her visit to The Kirklin Clinic, UAB Medicine has instated a variety of new policies this year that require and enforce safe social distancing and masking practices for all patients, visitors and employees.

Like Sutton, each of these individuals must complete a temperature check to screen for fever symptoms before entering any campus or clinical building and must wear a face covering while in these spaces, which are disinfected by staff multiple times per day. UAB Medicine has also implemented strict visitation guidelines for its hospital and clinic locations, limiting the number of visitors who can accompany patients on their visits, and has rearranged all clinic seating so patients and visitors remain at least six feet apart while waiting for their appointments to begin.

Jordan DeMoss, MSHA, the vice president of the UAB Cancer Service Line, says these new policies were established to make clinical spaces safer for patients like Sutton, as well as for families, visitors and staff.

“We believe that, with the right safety protocols in place, we can assure our patients and their families that they are safe to come to UAB for cancer care,” DeMoss said.

“Through our intentional efforts, we have created a way for patients to access our care while maintaining patient-centered principles, such as the presence of a compassionate caregiver during their visits, which is critical for a patient undergoing cancer treatment.”

For services that do not require patients to be physically present, UAB Medicine also offers telehealth alternatives that have replaced many in-person visits with virtual ones.

Through UAB eMedicine, patients can easily and securely speak to their care team via a phone or video call initiated by a text message sent to the patient before their scheduled appointment time. Patients also have access to the UAB Medicine patient portal, which allows patients and their care teams to send secure messages to one another, request medication refills and view lab results online.

“One bright spot in the pandemic is that it’s pushed us to support and invest in telemedicine,” Sleckman said. “Because of this, we were able to compress years of infrastructure and systems management into a single month so that, now, telemedicine is a fairly standard method of caring for patients who don’t need an in-person test or physical exam.”

Chairs are arranged to follow social distancing guidelines in the waiting room of The Kirklin Clinic of UAB Hospital on May 19.

“NOW, PERHAPS, THE WORLD KNOWS WHAT IT’S LIKE TO BE A PERSON WHO FEELS VULNERABLE TO DISEASE. THAT’S HOW I THINK WE ALL FEEL EVERY DAY."

MARIE SUTTON O’NEAL CANCER CENTER PATIENT AND SURVIVOR

UNMASKING THE VIRUS

When it comes to how COVID-19 impacts people with cancer, much is still unknown, but researchers at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center are working to uncover the nature of the virus and its relationship with cancer.

The biggest push in this endeavor comes from the NCI COVID-19 in Cancer Patients Study, or NCCAPS, which is a long-term, natural history study of how COVID-19 and its symptoms develop and change in people with cancer. According to the NCI, the findings from NCCAPS could influence how cancer patients with COVID-19 are treated in the future.

As a natural history study, NCCAPS isn’t testing a new treatment for COVID-19 or cancer but is, instead, collecting information on cancer patients' medical history, cancer history, cancer treatment, COVID-19 treatment and possible disease management changes in order to learn more about the effects of COVID-19 on people with cancer, as well as the effects of cancer on those with COVID-19.

UAB is one of more than 700 clinical trial sites across the country contributing to this nationwide longitudinal study. Charles A. Leath III, M.D., MSPH, a senior scientist at the O’Neal Cancer Center, is UAB’s principal investigator on the NCCAPS trial.

Leath says he hopes this study will highlight the factors that are associated with the short- and longterm outcomes of COVID-19, such as a patient’s individual characteristics, including pre-existing comorbidities and cancer type and treatment, among others. He also says that COVID-19 and cancer share many comorbidities that could affect the severity or fatality of the disease in cancer patients who are undergoing treatment.

“Increasingly, data suggests a negative consequence for cancer patients receiving active anti-cancerrelated therapy, which may be differential based on the specific type of treatment,” Leath said. “In addition, underlying medical problems that impact the cardiovascular or respiratory system – which are often more common in medically underserved individuals, including minorities and those in rural areas – also impact cancer treatments to begin with and, perhaps, accentuate the effects of COVID-19 infections.”

TRANSLATING THE SCIENCE

By Anna Waters

eyond the work being conducted through the National Cancer Institute, some scientists at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center are using what they’ve learned in their cancer research to fight COVID-19.

Keshav Singh, Ph.D., a senior scientist at the O’Neal Cancer Center, is considered an expert on the role of mitochondria in cancer but has recently turned his attention toward their role in COVID19. In a study published in the American Journal of Physiology in June, Singh and his co-authors investigated how the novel coronavirus, also called SARS-CoV-2, avoids the cell’s immune response by hijacking the mitochondria within it.

Mitochondria serve as a hub for antiviral signaling. They can detect viral infection in a cell and cause the cell to self-destruct before the virus can spread further. Singh says viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 can impair the functionality of mitochondria, but so can cancer, especially for people who are older or have African ancestry.

Mitochondrial dysfunction induces mutations in nuclear DNA, leading to the immortalization of cells common to cancer, as well as the ability of SARSCoV-2 to evade host cell immunity and replicate. With his colleagues at Kings College Hospital in London, England, Singh recently validated mitochondrial hijacking in COVID-19 patients and found a strong correlation between the increased expression of mitokine, a mitochondrial stressinduced cytokine, and the severity of COVID-19.

“These observations suggest that drugs that can either interfere with the hijacking of mitochondria or restore host mitochondrial function may prevent or treat COVID-19 and cancer,” Singh said.

The role of cytokines is an important area of study for COVID-19 research. When the body’s immune system overreacts to an infection, it can result in a cytokine storm, which is thought to be responsible for many of the deaths related to COVID-19.