Hear from leaders in Boone ’ s top industries about how Helene affected daily life in the High Country and its journey to a new normal

Throughout my time at Appalachian State University, I have grown to love the rich community present here in the High Country. Boone has been a supportive environment in which I have been able to grow as an individual and find my way in the world. In my final semester, I wanted to utilize the skills acquired through my degree program at ASU to create a piece of media that celebrates the community that welcomed me with open arms.

On September 27, 2024, communities in western North Carolina were devastated by Hurricane Helene. Sept. 27 and the days that followed were filled with feelings of confusion, hopelessness and grief. Some community members had lost everything.

Despite the feelings of defeat, the community quickly jumped to action. Within hours, community members were going door-to-door to check on their neighbors and to see how they could help. In the wake of disaster, individuals were relying heavily on members of their community for answers and help. Despite the tragedy that the High Country faced, the community persevered and continues to persevere to this day.

As a journalist, I knew there were people out in the community with an important story to share. High Country Humanity was created with the intent to give a voice to those individuals. I hope this magazine will be visited and utilized by many so we can all celebrate the way that the High Country came together in unity after a tragedy.

Helene originates from a Central American Gyre (CAG)3, broad lower-tropospheric cyclonic circulation, over Central America.

The circulation developed into a tropical storm located roughly 175 miles south of the western tip of Cuba. Tropical Storm Helene was producing 40-kt winds.

SEPTEMBER 20

SEPTEMBER 23

The large cyclonic circulation began to straddle Central America and the northwestern Caribbean Sea. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) issued tropical cyclone advisories for the area.

24

Helene enters the Gulf of Mexico as a category 1 hurricane. Tropical storm force winds expanded outward 360 miles from the center of the hurricane.

SEPTEMBER 25

SEPTEMBER 25

The center of the storm was located 50 miles east of Cozumel, Mexico. The storm was now producing 55-kt winds. Six hours later, Helene developed into a hurricane, just east of Cancun.

Helene makes landfall 10 miles southwest of Perry, FL, as a category 4 hurricane. Helene is recorded as the strongest hurricane to make landfall in the Florida Big Bend region since roughly 1900.

Helene weakened to a 60-kt tropical storm located roughly 30 miles east of Macon, Georgia.

Helene intensified into a major hurricane producing 105-kt winds, with the eye of the storm being located 150 miles southwest of Tampa, FL.

Helene moves extremely quickly through inland Florida, moving northwest towards Georgia.

Helene quickly approached the Georgia-South Carolina-North Carolina border region. Hurricaneforce wind gusts spread from the coastal region of Georgia and southern South Carolina, to the mountains of western North Carolina.

A: Boone Mall parking lot filled with mud after the flooding went down.

B: NC-105 collapses into Laurel Fork. Photo Courtesy of Laine Garrison.

C: Parking lot at Graystone Lodge fills with flood waters. Photo Courtesy of Laine Garrison.

D: Road flooding in front of the Boone Airport.

E: Wilson Ridge Road collapses after Mutton Creek rises exponentially with flood water.

To hear the voices of individuals directly affected by the destruction of September 27, 2024, click on the icon to the right.

By Anna Haydel

In the wake of a disaster, affected individuals are often left searching for information and guidance.

Journalism plays a vital role in these situations, as the role of a journalist is to inform their community.

In the days following Hurricane Helene, news outlets from different cities and states flocked to parts of western North Carolina to document the disaster and devastation left by the storm. Information about how to recover was missing from many of these national stories.

Watauga County residents felt disconnected and worried. For many, their only sources of information were their local news outlets.

The Watauga Democrat is a news outlet located in Boone, North Carolina that covers Watauga County. It’s part of Mountain Times Publications, which includes five publications in Watauga, Ashe and Avery counties.

“I felt our role was to inform people on how they can get help and move forward from this,” said Moss Brennan, editor of the Watauga

Democrat and executive editor of Mountain Times Publications.

The Watauga Democrat staff overcame numerous obstacles in an effort to serve and inform their devastated community. Without access to the internet and navigating spotty cell service, local journalists had to create solutions to these obstacles.

“For the first few days after the storm, I had no internet,” Brennan said. “My house had a cell signal, but my hot spot wouldn’t work, so I was working at a McDonald’s parking lot because, for some reason, they had Wi-Fi.”

Brennan and his team worked tirelessly trying to provide as much information as possible to as many people as possible. They understood their role as journalists was to inform their community, and they did just that.

The Wednesday following the storm, the Watauga Democrat put together a print product to deliver to places without internet access. “Some people were saying, you know, this is the first news I’ve had since Friday. We didn’t have power. I didn’t have internet or cell service, nothing,” Brennan said.

For many individuals stranded in their homes, the extent of the damage was unknown to them. Many areas of the county were initially inaccessible, and

cell service was nowhere to be found.

Over the first few weeks after the storm, the Watauga Democrat reported stories they felt were important to the community. These reports included information about what was happening around the town of Boone, how to get assistance from FEMA and how to apply for aid.

Though much of the information for the Watauga Democrat’s reporting came from Watauga County Emergency Services, local fire departments and government officials, members of the community played a major role in the journalistic process. Through community members’ posts on social media, the Watauga Democrat was able to focus on the questions and stories that mattered.

important that is,” Brennan said.

“We are really about community and serving the community. We want to be the voice for the community.”

When the community started to return to a new normal and the town meetings and high school sports returned, the Watauga Democrat covered these events. “Everything was touched by Helene,” Brennan said. “So I would say that even though we were covering other stories, it was still touched by Helene.”

To hear about Jane

“Having local news that has dedicated reporters — that this is their job — they’re going to interview people and talk to people is super important. This storm showcased how

In the days following the storm, and even to this day, community members relied heavily on the Watauga Democrat for information, which highlighted the need for local news. “We are really about community and serving the community,” Brennan said. “We want to be the voice for the community.”

By Anna Haydel

North Carolina is among the top states for diversification of crops in the country. The High Country, more specifically Watauga County, relies heavily on the diverse agriculture industry for economic health and community engagement. September 27, 2024 changed all of that.

When Hurricane Helene worked its way through the mountains of western North Carolina, it destroyed many acres of farmland in her path. As a result, the agriculture community has suffered great losses and faces a long future of rebuilding ahead.

“Hearing that there was a hurricane passing over, I assumed, well, this is just one hurricane, we went through two,” said Jim Hamilton, the Watauga

County extension director, referring to when Hurricanes Frances and Ivan swept through the mountains of western North Carolina in 2004.

“I saw power lines down, saw where the larger creek was cresting that was flowing into Boone, and that’s when I realized it was going to be bad.”

Watauga County is home to several organizations that directly support and assist local farmers and producers. Following the storm, many of these organizations collaborated with others in the agriculture industry to provide for locals’ needs.

The NC Cooperative Extension is an organization that originated from the land-grant university system. North Carolina State University and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University serve as the two landgrant universities in North Carolina.

The cooperative extension has an

office in each of the 100 counties in North Carolina, as well as in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. This organization facilitates county offices in taking research developed by the two universities and applying it in their agricultural communities.

In the days, weeks and months following the storm, the Watauga County office played a vital role in the rebuilding of the agriculture industry. “My first thought was, I need to check on people,” said Kendra Phipps, extension agent for the Watauga County office.

Right after the storm, Phipps focused her efforts on making contact with all of the farmers and producers who work with the extension to figure out essential needs for the agricultural community.

The first call outside of local farmers and producers was to the executive director of the North Carolina Cattlemen’s Association.

Phipps expressed the immediate need for temporary fencing to contain livestock, as many farms experienced damage to their enclosures.

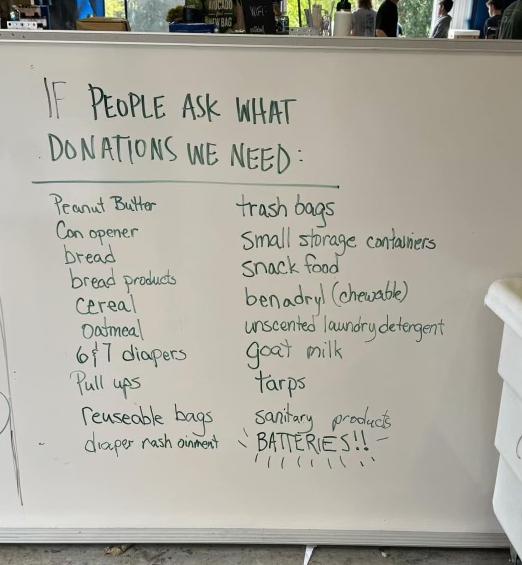

Calls were pouring in from agricultural communities, some as far as Arizona, offering donations for western North Carolina farmers and producers. The Watauga County office quickly realized that they were going to need to establish a place for donations to be dropped off and then distributed.

Contact was made with the Brown family, the owners of Corbett’s Produce in Deep Gap, as they had a flat, easy-to-access piece of land in a part of the county less affected by the storm. This area became the distribution center, welcoming countless trucks full of donations.

As Hurricane Helene became

Continued from Page 11

national news, connections began forming through social media and online platforms. An Ohio media influencer involved with the agricultural industry organized a convoy of roughly 50 trucks carrying various donations.

In the days immediately after the storm, farmers and producers needed temporary fencing, hay and bags of feed. “It came in waves, we would get, I remember, two pallets of barbed wire and fencing,” Hamilton said. “And it would be gone the next day.”

High Country Food Hub, a Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture program, provided storage for refrigerated and frozen goods since they had large freezers and refrigerators that never lost power.

Despite the efforts of the Watauga

County office and the agricultural community, some farmers and producers had lost more than they could recover. One farmer decided to leave the industry altogether, while many had to sell cattle due to the lack of resources and money. The effects brought about by Hurricane Helene are still being experienced by farmers and producers across the county. Obstacles such as unfarmable land and loss of revenue will affect the agricultural community for years to come.

With the help of the local community, as well as others in the agriculture industry, local farmers and producers continue to work toward rebuilding what Helene destroyed. “It was amazing what came. It was really neat to see the level of help and volunteerism that kicked in within days,” Hamilton said.

Volunteers gather at Carringer Farms in Avery County, NC.

By Anna Haydel

For many communities in the mountainous region of North Carolina, the month of October shepherds a huge increase in tourism. Festivals and football games, in addition to the changing of leaves, lure many visitors to the streets of the High Country.

“Sept. 27 was a day that I think everybody’s going to be able to kind of say where they were and what they were doing when they really started to realize what had gone on.”

- David Jackson

Autumn in Boone is typically filled with endless traffic, busy stores and the constant parade of new faces. However, when October rolled around in 2024, many businesses were closed indefinitely and the streets were often empty, except for the movement of supplies and donations.

“Sept. 27 was a day that I think everybody’s going to be able to kind of say where they were and what they

were doing when they really started to realize what had gone on,” said David Jackson, the president and CEO of the Boone Area Chamber of Commerce.

The Boone Area Chamber of Commerce works closely with local ventures to build and maintain relationships among the businesses that make up the community. In this role, the chamber of commerce works to advocate and provide for the needs of local enterprise.

“This is a community that is built on tourism and people. Whether they’re university students or travelers, visitors, second home people, whatever, that’s who we are,” Jackson said.

Throughout active recovery, the Boone Area Chamber of Commerce took on various roles throughout the community. As luck would have it, their office space went virtually

untouched, so Jackson and his team knew they had to get to work, and they knew they had to act quickly.

“Our first steps were to get information. Like many people, it was hard to understand really, the totality of anything because your trusted sources of where you get that stuff from didn’t exist or weren’t available,” Jackson said.

In the first days after the storm, the chamber’s office building was without internet access. Jackson and some of his colleagues set up at a table in Appalachian State University’s student union and used the internet access available to begin communicating with individuals and start making connections.

The chamber of commerce organized themselves into various groups in order to meet the needs that arose in the first few days. Following a press conference that

involved community stakeholders and government officials, the Boone Area Chamber of Commerce took on the official role of managing supply, distribution and delivery.

Summit Pickleball, in Boone, N.C., had reached out to the chamber of commerce to offer their warehouse area as a storage and staging area. Summit Pickleball became the distribution center for supplies needed throughout the High Country.

Trucks and 18-wheelers brought supplies, volunteers moved the donations from trucks to cars, and then the cars would transport these supplies to areas that needed them the most. For weeks, the movement of supplies in and out of the warehouse continued.

In addition to distributing supplies for the community, the chamber of commerce played a key role in assisting and supporting their business partners.

“We’ve had a long-standing relationship here in this community as a trusted source, and we really try to lean into that in good times and in bad,” Jackson said.

Tourism, Page 17

Volunteers gather at Summit Pickleball in Boone, NC to help organize and distribute supplies for the community.

Despite the Damage Experienced, Local Businesses Still Opened Their Doors to Help.

Continued from Page 15

Many local businesses sustained physical damage to their property. Boone was not in a place to welcome tourists at the time, leading to the difficult decision for many to close their doors at a vital time in the tourist season.

October makes up roughly 60-70% of total revenue for some businesses in Boone. Jackson explained the decision to turn away tourists was a balancing act between needing the money to heal, while simultaneously needing the space to heal.

The chamber of commerce was also involved in the decision to welcome Appalachian State University students back to Boone. After allowing businesses the space to address some of the damage, Jackson felt the local economy needed to return to some normalcy to give the businesses a fighting chance to survive.

After weeks of no tourism, businesses were struggling financially. The Boone Area Chamber of Commerce started raising money for their small business disaster fund, “Hope for the High Country: Hurricane Helene Business Resiliency Disaster

Grants,” in late September 2024.

Through donations from individuals and corporations, the chamber was able to raise around $800,000 in a short period of time. This fund targeted two major areas.

The first was the childcare industry. Jackson and the chamber felt this was a vital industry that needed to be up and running so families could focus on rebuilding their homes. The chamber of commerce paid $206,000 to local childcare providers to pay down the debts they incurred throughout October.

The remaining $470,000 was used to help the chamber’s 162 business partners with whatever needs they had. Grants to the businesses ranged anywhere from $500 to $25,000.

Grants were given to businesses without the expectation of receiving any money back. The chamber of commerce wanted to use this money to allow their business partners a chance to remain open to serve the community. Only 2 of the 162 businesses that received financial aid had to close their doors.

“You know, this is a community that takes care of its own,” Jackson said.

Ospeakers.

n January 27, 2025, Appalachian State University held the “Post-Helene Community Resiliency Forum. This forum was a part of ASU’s Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP), “Pathways to Resilience.” This event was held in the Parkway Ballroom in the Plemmons Student Union. Starting at 6:00 P.M., this forum featured a panel of speakers who served as community leaders within different areas of living and wellbeing. Speakers included Liz Whiteman, Executive Director of Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture, Andy Hill, High Country Regional Director and Watauga Riverkeeper for Mountain True, Kellie Reed Ashcraft, Executive Director of the Watauga Housing Council and David Jackson, President and CEO of the Boone Area Chamber of Commerce. In addition to hearing from the panel of speakers, those in attendance were able to view Dr. Beth Davison’s, short film titled “We Begin Again at 9:30,” which covered Todd, NC’s response to Hurricane Helene. The event concluded with the opportunity for community members to ask panel speakers, as well as Kelly McCoy and Renata Dos Santos, owners of RiverGirl Fishing Co., any questions they had regarding Helene and community recovery.

To listen to the discussion among panel speakers at the forum, click on the icon to the right.

Amy Forrester is the owner of FizzEd, a restaurant located off Howard Street in Boone, NC. FizzEd opened in February 2024. Being a relatively new restaurant when Hurricane Helene hit, Forrester got creative and offered free meals to first responders, linemen and anyone else who was hungry. Forrester saw this as an opportunity to keep staff employed and give back to the community. For their work throughout Helene recovery Mike and Amy Forrester were awarded the Dogwood Award in December 2024.

Consider donating to organizations that are still actively involved in relief efforts.

NCCF Disaster Relief Fund

Boone Area Chamber of Commerce

Samaritan’s Purse

Consider visiting the High Country and spending your money with local businesses.

Consider buying food locally to support farmers and producers who are in the process of rebuilding their farms.

With support from the community, Boone continues to work towards a new normal.