Sydney’s hydrofoils

Sydney’s hydrofoils

WELCOME TO THE SPRING EDITION of Signals.

As spring unfolds, we continue to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with our series of exhibitions and talks entitled The World Remade. With so much uncertainty in the world, it is timely to reflect on our history – we can always learn from the past.

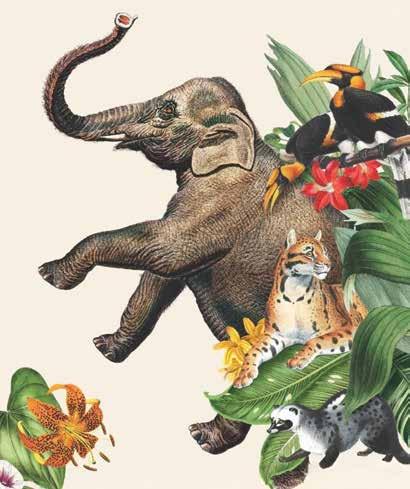

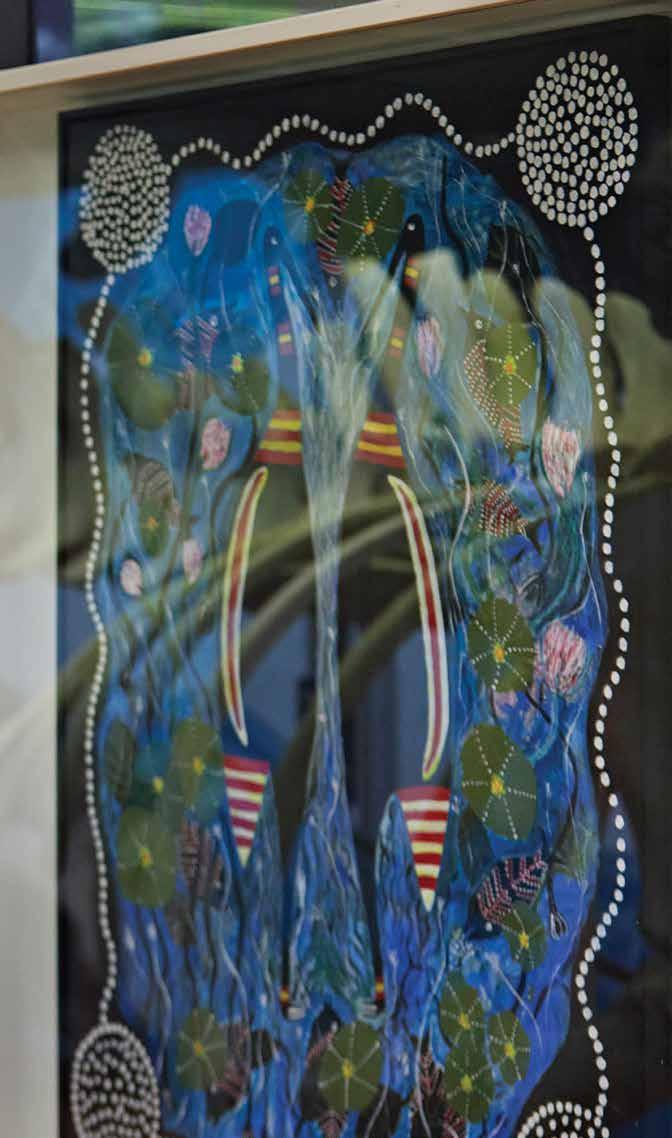

We are proud to launch a wonderful Indigenous exhibition, Ur Wayii (Incoming Tide), featuring the work of Torres Strait Islander Brian Robinson.

Robinson is a Waiben (Thursday Island) artist who also has Maluyligal and Wuthathi heritage. His work explores imagery drawn from ancestral iconography of the Torres Strait (Zenadth Kes), which he uniquely interweaves with images from popular culture and science fiction. His work is in great demand around the world, and we are so pleased to feature it in a solo exhibition.

We also have a small exhibition called Frozen Witness: Aurora’s polar voyages , which brings to life the extraordinary story of a remarkable vessel – a timber whaling ship turned Antarctic explorer – whose legacy spans sealing, science, survival and ultimate sacrifice.

Built in 1876 in Dundee, Scotland, the 580-ton SY Aurora was originally designed for Arctic whaling. But the ship’s destiny lay far to the south. Over four decades, Aurora became a silent witness to some of the most dramatic chapters in polar exploration, including the heroic expeditions of Sir Douglas Mawson and Sir Ernest Shackleton.

The exhibition features a selection of historic objects donated to the National Maritime Collection by family members, including a lifebuoy, the only remaining

item from the vessel’s disappearance in 1917, a most evocative artefact. The exhibition invites visitors to rediscover this remarkable vessel and the people whose lives were entwined with it. Their story is one of endurance, innovation and the power of the human spirit in the face of the unknown.

In November, the 2025 Ocean Photographer of the Year exhibition will have its world premiere here at the museum. We are so proud of shepherding it alongside Oceanographic Magazine off the printed page and computer screen into museums and galleries around the world.

As this edition goes to press, we are delighted to announce the appointment of The Hon Hieu Van Le AC as the new Chair of the Australian National Maritime Museum Council. He was governor of South Australia from 2014 to 2022 and is a former chair of the South Australian Multicultural and Ethnic Affairs Commission. A fuller profile will appear in the next issue of Signals

As always, I am happy to hear from the museum family about what matters to you, so please, if you have any ideas, drop me a line to thedirector@sea.museum I may not be able to respond directly to every person, but please be assured, different voices are both welcome and encouraged.

Daryl Karp AM Director and CEO

Acknowledgment of Country

The Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all traditional custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language.

Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased.

The museum advises there may be historical language and images that are considered inappropriate today and confronting to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The museum is proud to fly the Australian flag alongside the flags of our Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea Islander communities.

Cover Two youth sail trainees aboard traditional sailing ship STS Leeuwin II

See article on page 2. Image Leeuwin Ocean Adventure Foundation

2 New respect for old ways

Youth sail training and tall ship traditions

10 The fast and the futuristic

The brief, exhilarating reign of Sydney’s hydrofoils

14 The weird and the wonderful

Our Head of Registration chooses her favourite collection items

20 Len Randell OAM

Western Australia’s first naval architect

26 Top-secret transmissions

A teenaged telegraphist’s wartime mission

30 Zane Grey’s quest

The epic hunt for a monster shark

36 Keeping historic boats afloat

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust restoration projects

42 David Attenborough’s plea for the ocean

A milestone event on World Ocean Day

44 A flotilla of model ships

Sydney Model Shipbuilding Club’s Expo 2025

46 Foundation

Donations make a difference

48 Members news and events

The latest talks and tours this spring

52 Exhibitions

What’s on display this season

56 Maritime heritage around Australia

The distinctive maritime culture of the Cocos Atoll

62 Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme

Highlights of the 2024–25 program

68 Research

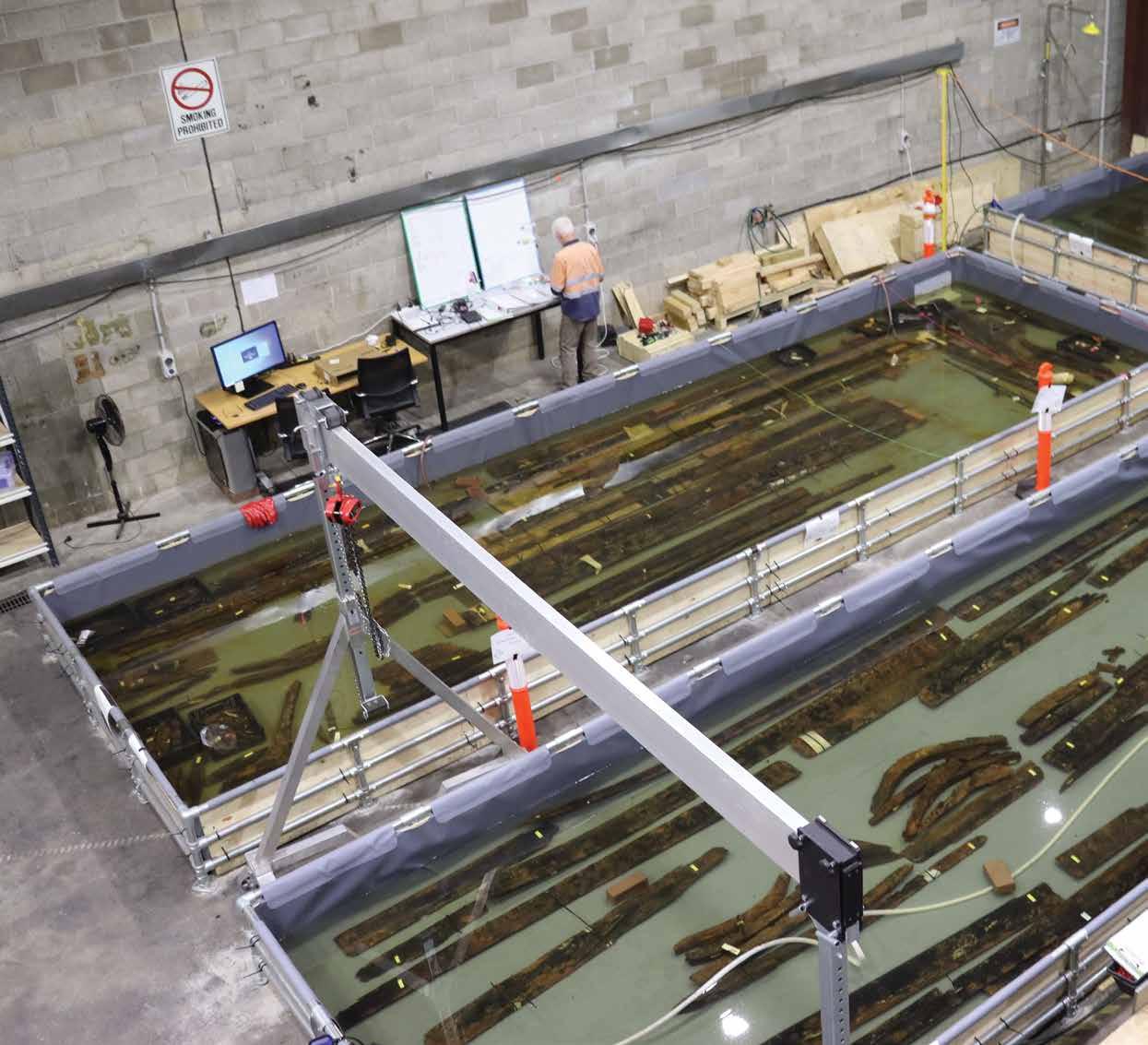

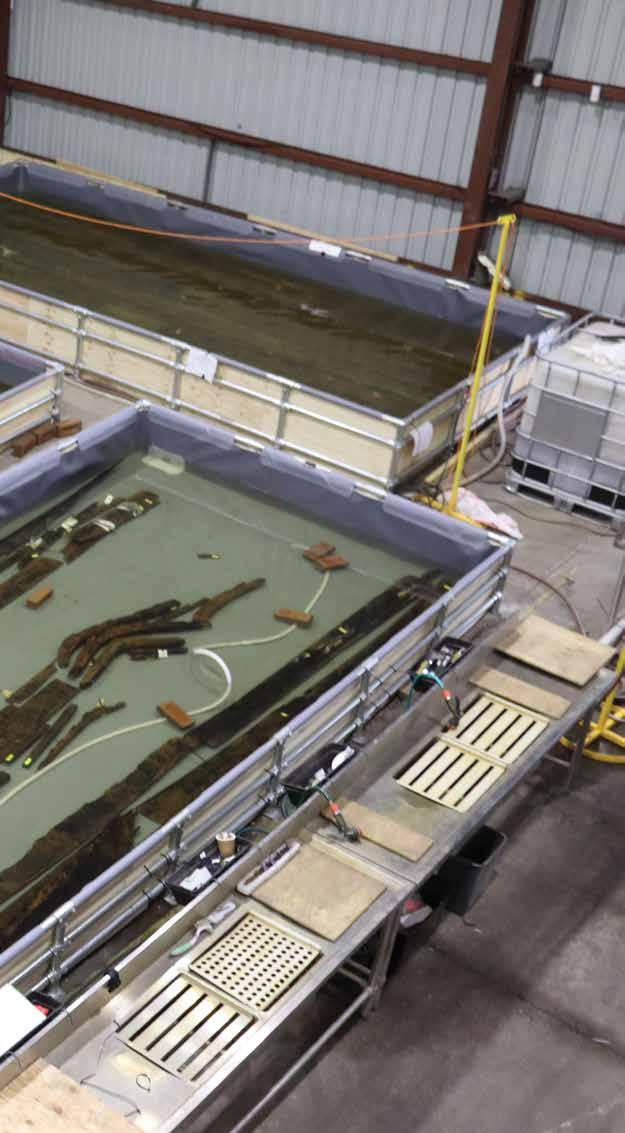

Conserving the Barangaroo Boat – a rare colonial vessel

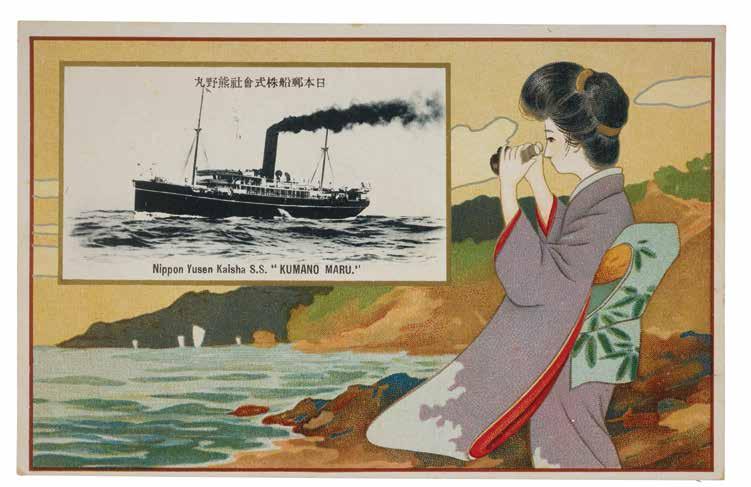

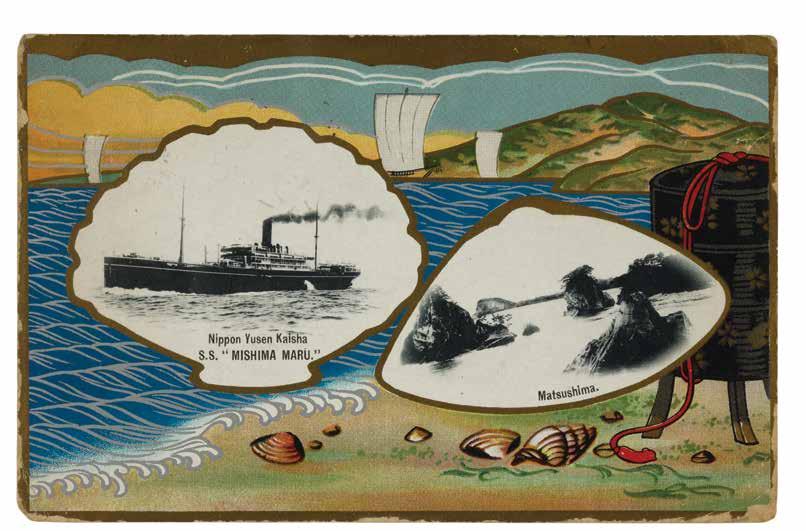

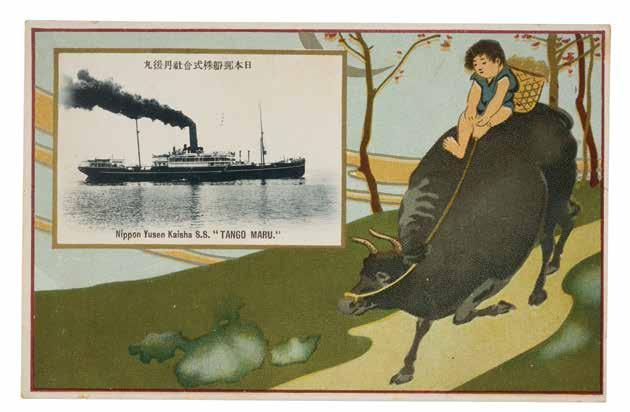

74 Collections

Japan’s maritime history in postcards

78 National Monument to Migration

Celebrating journeys to a new life

80 Readings

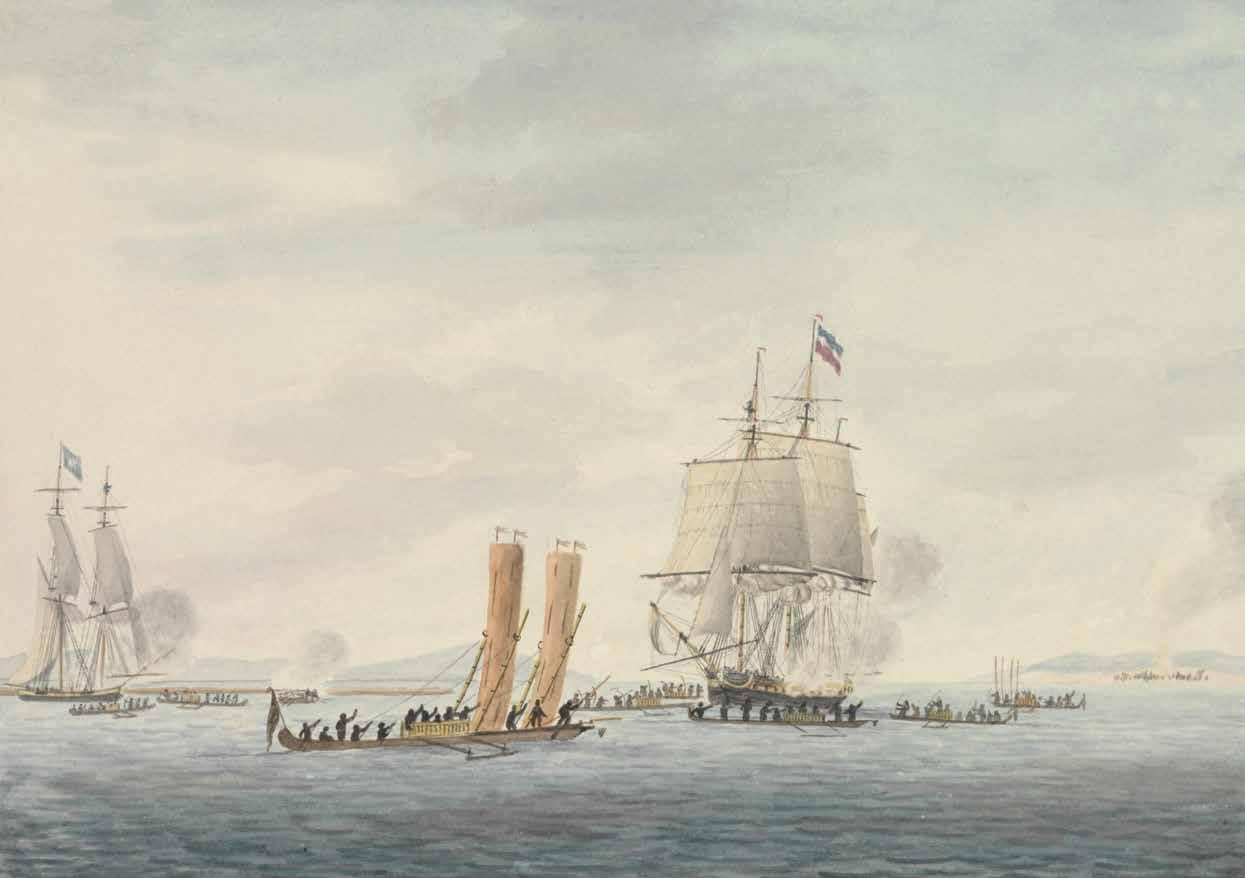

The Tinpot Navy ; Dangerous Passage

86 Currents

Vale Hugh Treharne OAM; Tunku & Ngaadi at Vivid Sydney

Tall ship sailing is growing in popularity around the world, including in Australia, where a fleet of restored, replica and newly built vessels with traditional sail configurations routinely ply the nation’s waterways. Jane Dargaville profiles the vessels and those who maintain and sail them.

South Australia’s modern-built brigantine One and All, whose design was inspired by that of a 19th-century schooner, conducting a public cruise on the Derwent River, Hobart, during the 2025 Australian Wooden Boat Festival. This biennial event brings tall ships from all around Australia to celebrate traditional marine craft. Image Michelle Bowen

The expansion of Australia’s tall ship fleet owes much to the immense success of youth sail training

Tall ship rigs involve complex arrangements of masts, booms, sails, ropes, cables, chains and tackle, and often unique pieces of gear

A VAST NUMBER OF SAILING SHIPS contributed to Australia’s development in the first 150 years of European settlement. The first mechanised ships –hybrid vessels, with both sails and steam-driven paddle wheels – began operating in Australia as early as the 1830s, but sailing ships continued to play a vital role in Australia’s commercial maritime trade for at least another century.

The term ‘tall ship’ is a modern generic name for a large, traditionally rigged sailing vessel.1 Accelerated industrialisation during World War II led to a decline in tall ship numbers, and by the 1950s a tall ship was a rare sight anywhere in Australia. But when tall ships from 30 countries figured large in national celebrations to mark the 1988 bicentenary of European colonisation, the public imagination was captured. Today, tall ships operate out of all the major cities, and from various regional and remote coastal locations, providing everything from brief harbour cruises to extended blue-water passages.

The rise in tall ship numbers over the last four decades has been driven by the passion, determination and hard work of a community of individuals and groups of dedicated tall ship devotees.

In Sydney Harbour, tall ships are a relatively common sight. The Australian National Maritime Museum has two working square riggers, a replica of Captain James Cook’s Endeavour and a replica of Duyfken, the original of which is believed to have been the first European ship to make landfall in Australia, off the northwest coast in 1606. The volunteer-run Sydney Heritage Fleet sails James Craig , a fully restored 1874 square-rigged, iron-hulled barque –one of only three remaining worldwide. The commercially run Sydney Harbour Tall Ships sails three historic square riggers, including two – Søren Larsen and Southern Swan (formerly Our Svanen) – that participated in the 1988 First Fleet re-enactment voyage. Sydney stages a tall ships ‘race’ each year on Australia Day. Britain’s gift to the people of Australia for the 1988 Bicentenary was a modern-design, 44-metre, steel-hulled, two-masted brigantine named Young Endeavour, which was handed over to the Royal Australian Navy to conduct civilian youth sail training.2

The expansion of Australia’s tall ship fleet owes much to the immense success of youth sail training, which is popular worldwide and promoted and supported by the global charity Sail Training International (which also organises a hugely popular annual tall ship race in European waters).

Over four decades, tens of thousands of young people aged between 14 and 25 have participated in Australian tall ship youth sail training programs. The benefits of sailing for building youth self-esteem and capability were well understood in Australia before the arrival of Young Endeavour, and in the two years before that vessel came onto the scene, two not-for-profit organisations, Leeuwin Ocean Adventure in Western Australia and One and All in South Australia, began operating tall ships to conduct youth development sail training.

In Tasmania, that state’s Sail Training Association runs sail training and youth adventure cruises on a two-masted brig named Lady Nelson, a replica of an 18th-century ship that played a major role in the early exploration and surveying of Australia’s southern coastal waters and in passenger transportation between Tasmania and the mainland. Also in Tasmania, the Windeward Bound Trust operates Windeward Bound, a modern-built, 33-metre, 120-tonne topsail schooner based on a traditional mid-19th-century design and made of Tasmanian hardwood timbers.

In Victoria, the trust-owned 27-metre topsail schooner Enterprize, a replica of a vessel of the same name which was built in Hobart in 1830, has been offering youth sail training since the 1990s. Another tall ship will soon put to sea for youth sail training once the Waypoint Foundation’s restoration of Alma Doepel is completed at Melbourne Docklands’ North Wharf. This 45-metre, three-masted topsail schooner and former cargo ship was built in Bellingen, New South Wales, in 1903.

The Sail Training Association of Queensland provides sailing adventures for school children and youths on a modern-design 30-metre gaff-rigged schooner named South Passage, which was built and launched in the 1990s and sails out of Moreton Bay.

In North Queensland, a 1902 Dutch-built squarerigger, Solway Lass, operates as a tourist vessel in and around the Whitsunday Islands, while several original early-20th-century ketches with gaff rigging, which are considered part of the tall ship fleet, sail in different locations around Australia.

Costly endeavours

Building, restoring, maintaining and sailing tall ships is costly and time-consuming. The tall ships run by notfor-profits fund their operations through their sailing activities and from hard-won sponsorships, grants and donations. Along with both youth and adult sail training, most also conduct commercial public cruises, charters and sea voyages. The service organisation Rotary is a strong supporter of tall ship youth sail training, providing different types of financial assistance, including individual scholarships to several vessels, such as Young Endeavour, Windeward Bound, Lady Nelson, Enterprize, South Passage and One and All. Apart from Young Endeavour and the Australian National Maritime Museum’s Endeavour and Duyfken, no Australian tall ship receives recurrent government funding.

Tall ship rigs involve complex arrangements of masts, booms, sails, ropes, cables, chains and tackle, and often unique pieces of gear, which might vary from one ship to another and which require a competent, experienced and fit crew to operate. Tall ship sailing also requires a knowledge and understanding of an extensive vocabulary of traditional nautical terminology. While some crew members are paid, the not-for-profits rely heavily on volunteers, and it is a constant challenge to train and retain good crew.

Over four decades, tens of thousands of young people aged between 14 and 25 have participated in Australian tall ship youth sail training programs

For ordinary crew members, an accredited deckhand qualification is offered by vocational training institutions in most states, but organisations also develop and implement their own training regimes. Senior crew members – masters, mates and coxswains – on vessels over 24 metres must hold qualifications recognised by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority. The Sydney Heritage Fleet, whose James Craig is Australia’s largest tall ship, requires its masters, all of whom are former senior naval or merchant mariners, to hold the Nautical Institute’s square rig endorsement.

Challenge and camaraderie

Eminent among Australia’s tall ship community is Captain Sarah Parry AM . In the 1960s, as a young navy sailor at Garden Island, she witnessed the entry into Sydney Harbour of a big three-masted schooner named New Endeavour. Mesmerised by its grace and beauty, Parry resolved to build one for herself, but it was another 30 years before Windeward Bound was launched in Hobart in 1996. The Windeward Bound Trust was set up in 1999 and has graduated more than 6,000 young people from all walks of life, including some of the most disadvantaged, from its sail training program.

For young people in particular, Parry says the experience is life changing:

It’s about learning to do something that’s going to bring them out of their comfort zone and enable them to move forward … sometimes you can see a shiver passing through them as they realise they’ve got control of a 120-tonne vessel in their hands. It makes magnificent changes in them.

01

James Craig crew member Pi Jeffares describes tall ship sailing as ‘beautiful to be a part of and to share with others’.

Image John Bowen

02

Former Windeward Bound youth sail trainee Mia Scicluna, left, is now a regular volunteer crew member on the vessel, as is Fenn Gordon, right. Many youth sail trainees go on to volunteer as crew members on tall ships in Australia and abroad. Image Windeward Bound

‘When you’re at sea, it’s about how you pull through. That’s the addictive side of it’

01 James Craig on Sydney Harbour, May 2025. John Dikkenberg (right) is one of its five Masters, all of whom are former naval or merchant mariners. Left is Head Bosun Brett Ryall and centre is longtime Mate Ainslie Robinson. Image Michelle Bowen

02

Since its launch in 1986, the purpose-built youth sail training barque Leeuwin II has hosted more than 40,000 young people from Western Australia on its voyages. Image Leeuwin Ocean Adventure Foundation

A plea for Leeuwin II

Australia’s tall ship community was stunned and saddened in August last year when the magnificent 55-metre three-masted barque Leeuwin II, while alongside at its homeport of Fremantle, WA, was struck by an out-ofcontrol container ship.

Two crew members who were asleep on board escaped serious injury and the ship’s hull was less damaged than it might have been. However, its masts, sails and rigging were completely destroyed.

Annie Roberts, CEO of the South Australian not-forprofit that operates One and All, which has seen more than 10,000 participate in its youth sail training, talks about the ‘camaraderie, the bonding, the feeling of belonging, of being needed and wanted’ experienced by young people:

They find that those they’ve met only five days earlier quickly become like family members. It gives a great sense of belonging and it doesn’t matter what background you come from. When you’re at sea, it’s about how you pull through. That’s the addictive side of it; that’s why people keep coming back.

Pi Jeffares began as a regular volunteer crew member on the Sydney Heritage Fleet’s James Craig at the age of 16 in 2022 and has also crewed on Leeuwin and Duyfken

She usually sails as a ‘topman’, climbing high into the rigging to work the sails, a role that demands skill and endurance, and one she loves:

Once we’ve set all the sails, we send two crew up each of the masts to tend the ropes to make them billow. We get sent up in any weather even if there’s a high wind.

Jeffares says she had always been fascinated by history but knew little of Australia’s maritime history before going for a public day sail on James Craig on Sydney Harbour:

It was so much fun to see how everything was working as it was in 1874. I was interested and wanted to know more … I soon fell down the rabbit hole and now I can’t leave. It’s beautiful to be a part of and to share with others.

Since its launch in 1986, the purpose-built Leeuwin has hosted more than 40,000 sail trainees in its program that targets disaffected young people aged 14 to 25. Leeuwin is Australia’s biggest youth sail training tall ship – with berths for 55 – and the only one that caters for people with disability.

Leeuwin ’s Master James Rakich, a former sail trainee on the ship himself, says:

Leeuwin’s program is incredibly popular, and the ship was busy conducting almost back-to-back voyages when it was damaged ... one of our promotional slogans is a quote from a young participant who said, ‘The only thing better than going on the Leeuwin is going on it twice’.

Last year the philanthropic Minderoo Foundation, established by Andrew Forrest and Nicola Forrest, granted the Leeuwin Ocean Adventure Foundation $3.5 million to help cover operating expenses over a three-year period and establish long-term financial sustainability. Even with this endowment, Leeuwin ’s restoration faces significant financial and practical challenges. Donations to assist with this project can be made at sailleeuwin.com/support/make-a-donation/

1 The term ‘tall ship’ was popularised by John Masefield in his poem ‘Sea Fever’ (1902): ‘I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky, / And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by’.

2 At the time of writing, the original Young Endeavour was on its farewell voyage, circumnavigating Australia with groups of young sail trainees embarking and disembarking at different locations, and its replacement, a three-masted Dykstra-designed brigantine, Young Endeavour II, was nearing the final stages of construction at a shipyard in Port Macquarie, NSW.

Jane Dargaville is a freelance journalist and a volunteer with the Sydney Heritage Fleet.

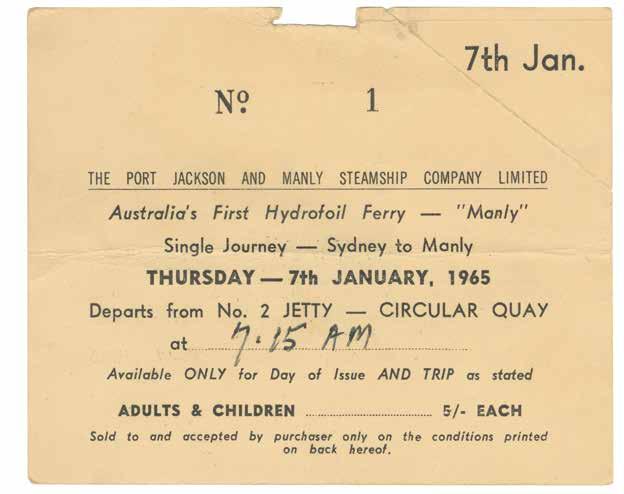

Sixty years ago, in January 1965, the first hydrofoil in Australia hit Sydney Harbour, revolutionising the Manly commute. Rob Egan looks back.

EARLY EXPERIMENTS in hydrofoil vessels began in the second half of the 19th century, and in 1965 the technology came to Sydney. The first passenger service left Circular Quay at 7.15 am on Thursday 7 January 1965. The vessel Manly was powered by a 1,350-bhp V12 Mercedes Benz–Fiat diesel motor capable of a cruising speed of 35 knots while planing on its foils. This halved the duration of the run from Manly to Circular Quay, taking 15–20 minutes compared with the regular ferry’s 35-minute trip.

Decades of change

In the decade or so following World War II, Sydney’s transport system underwent a series of rapid, dramatic and far-reaching changes. Public passenger transport, especially ferries and trams, was the area most affected. The last line on the tramway system closed in 1961. Ferry travel had revived somewhat during the war years, from 28 million passengers in 1939 to 37 million in 1945, but began declining after the war, and its patronage fell

to a low of 11 million in 1963 (although it has since risen slightly).1 Part of the cause was the growing acceptance of the motor car. In the 1950s, the remaining ferries were gradually converted from coal-burning engines to diesel power. This may have increased speed, but only marginally. For many people, trips appeared shorter and more convenient using private cars.

The future was seen as belonging to the motor vehicle: motor buses would soon be the major form of public transport serving the city and suburbs. At the same time, private motor cars were owned by more and more people.2 The Warringah Freeway was in the works, splitting the lower north shore in two and prioritising vehicles across the now eight lanes of traffic over the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

With the tram network removed by 1961 for the benefit of buses, and the Warringah Freeway yet to be completed, the hydrofoil was the ultimate traffic buster. Not only did it halve the travel time of the traditional ferry, it rivalled the fastest bus trip through the north shore – and avoided any inconvenient Spit Bridge openings.

Hydrofoil Manly, in its original livery, on its regular run from Circular Quay to Manly. Printmax c 1965. Postcard from the author’s collection

As a hydrofoil’s speed increases, the hull is raised entirely clear of the water by the lifting force of the foils

In the decade or so following World War II, Sydney’s transport system underwent a series of rapid, dramatic and far-reaching changes

01

The National Maritime Collection recently added ticket number one from the first journey. ANMM Collection 00056621

02

Passengers board a hydrofoil at Manly for the trip to Circular Quay. Photographer Curly Fraser. State Library of New South Wales, Australian Photographic Agency –18258

03

A souvenir ticket from an early journey, another recent addition to the National Maritime Collection. ANMM Collection 00056622

04

A souvenir keyring depicts a hydrofoil zooming towards Circular Quay. Author’s collection

The Port Jackson and Manly Steamship Company’s popular slogan trumpeted Manly as a location ‘seven miles from Sydney and a thousand miles from care’. Until bridges and roads connected Manly directly with the city, the locality remained largely the haunt of the wealthy or those with established sea legs. After World War II, however, aged and deteriorating facilities, combined with changes to the tourist market, led to a significant decline in stopover visitors. This became acute by the early 1960s. The rise of both the car and the backyard swimming pool also undermined harbourside resorts as people drove to surf beaches or swam at home. Enter the hydrofoil – part traffic buster and part novelty. For the first 18 months or so, you could even get a personalised souvenir ticket. From the mid-1970s, a burst of successful local protest reversed the decline of traditional ferry services, which had been exacerbated in part by the establishment of hydrofoils as a faster commuting option. This contributed to a period of urban gentrification which continues in the 21st century. 3

Manly was the third ferry to carry this name and had a capacity of 72 passengers. It was a PT20 type built by Hitachi Shipbuilding and Engineering in Japan under licence from Sachsenberg Supramar. Manly arrived in Sydney aboard the Japanese cargo ship Kanto Maru on 31 December 1964. The hull was aluminium alloy, with two foils of tempered steel. As a hydrofoil’s speed increases, the hull is raised entirely clear of the water by the lifting force of the foils, which enables the vessel to navigate at high speeds without wave and friction resistance on the hull.

The vessel was certified to travel as far as Port Stephens and Jervis Bay, but only one such trip went beyond the proposition stage. In 1967 Manly, along with the

The rise of both the car and the backyard swimming pool undermined harbourside resorts

traditional ferry North Head, travelled to Melbourne to provide tourist trips during the Moomba Festival. It took 30 hours to complete the 385-nautical-mile journey, with one fuel stop at Eden. The vessel was damaged in a wind squall in Port Phillip Bay on 16 January 1967. Manly served until 1978, when limited passenger capacity and reliability issues relegated it to a spare boat.

Manly was withdrawn and sold in 1979 to Hydrofoil Seaflight Services in Queensland and renamed Enterprise for use between Rosslyn Bay and Great Keppel Island. The service was unsuccessful and Enterprise was sold to a private owner, who removed the foils and engine. In 1991 the hull was transported to Mildura, Victoria, where it was intended for use as a floating restaurant on the Murray River. In 1995 the hull was transported to a private property north of Sydney for conversion to a private cruise boat. It remained there until around September 2021, when the vessel was finally broken up.

Hydrofoils ceased operation in 1991 and were replaced by JetCat catamarans. These operated from 1990 to 2008 but proved unreliable and expensive. Both hydrofoils and JetCats led the way for the current services, provided by Manly Fast Ferry and the Emerald class of vessel, to continue the legacy of Manly

1 Wotherspoon, G (2008). Transport. The Dictionary of Sydney <https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/transport>. Ferry patronage has risen slightly since, to 15.5 million passengers per year today.

2 Ibid.

3 Ashton, P (2008). Manly. The Dictionary of Sydney

Rob Egan works in a local history role for Blacktown City Libraries and is a volunteer with the museum’s Vaughan Evans Library.

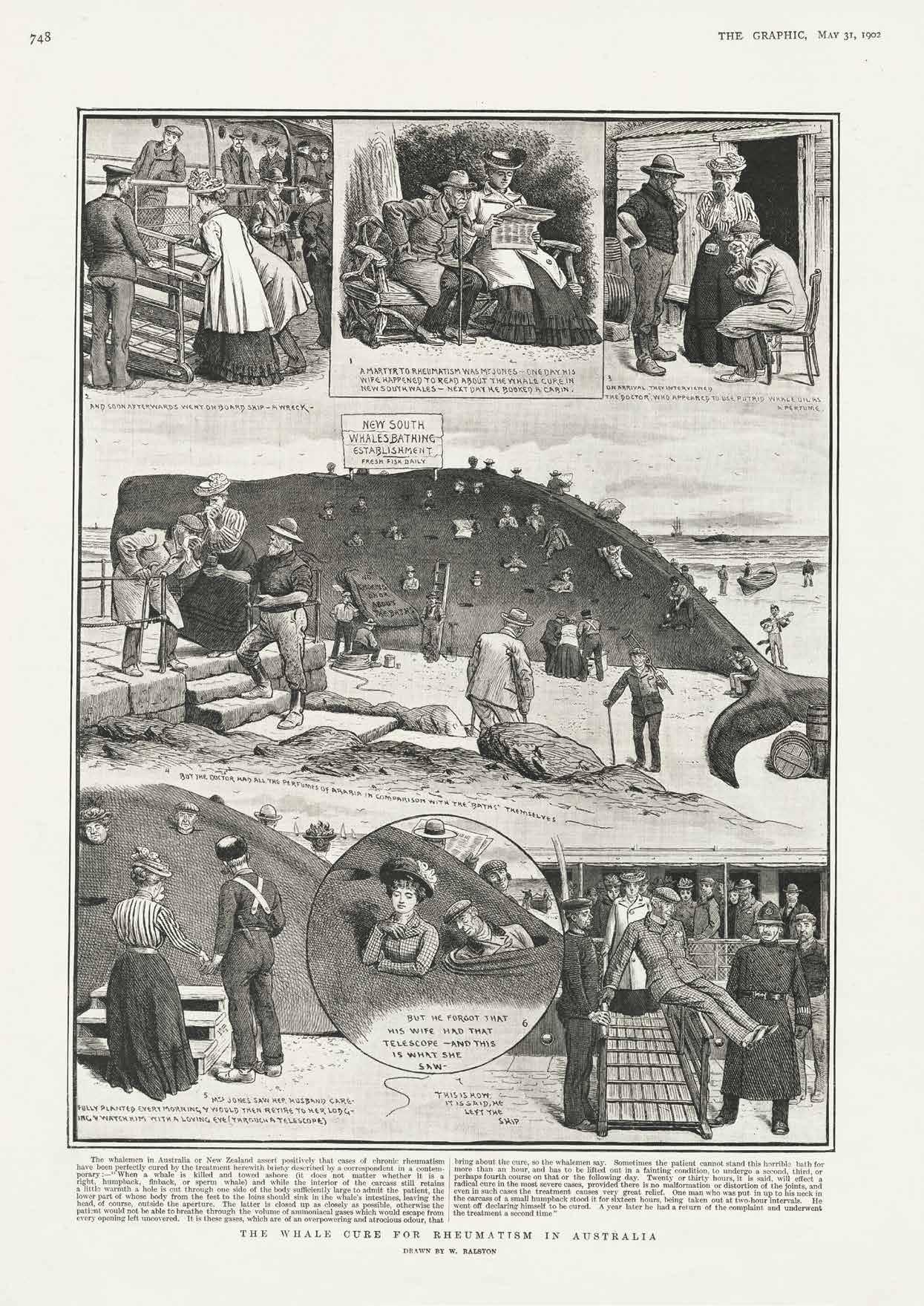

Seven individual engravings tell a story about Mr Jones, ‘a martyr to rheumatism’, as he undergoes the whale cure. ANMM Collection 00006998

A founding staff member of the museum, Sally Fletcher has been overseeing the collection since the late 1980s

Sally Fletcher, Head of Registration, is the woman who knows how to find anything among the 162,000-plus objects in the museum’s collection. She shares some of her favourite items with Tim Barlass.

THERE’S A WOODEN SIGN pushed into the back of what looks to be a decaying sperm whale washed up on the beach. The sign says, ‘New South Whales bathing establishment’. Languishing in holes cut into the putrefying carcass are 30 or so men and women, some literally up to their necks in it. One is reading a newspaper despite the evident appalling smell of ‘ammoniacal gases’.

This image, published in The Graphic in May 1902, is captioned ‘The whale cure for rheumatism in Australia’. Whalemen of the time asserted that chronic rheumatism could be perfectly cured by the treatment outlined above. ‘Sometimes the patient cannot stand this horrible bath for more than an hour and has to be lifted out in a fainting condition, to undergo a second, third, or perhaps fourth course on that or the following day.’

‘I wouldn’t do it,’ says Sally Fletcher, who is the museum’s Head of Registration and has chosen the item as one of her favourites among the collection.

A founding staff member of the museum, Sally has been overseeing the collection for decades, even before the museum’s opening in 1991. She is responsible for ensuring that all objects purchased or on loan, however large or small, however delicate or valuable, are accurately catalogued and stored where they can be readily found by curators preparing them for exhibition.

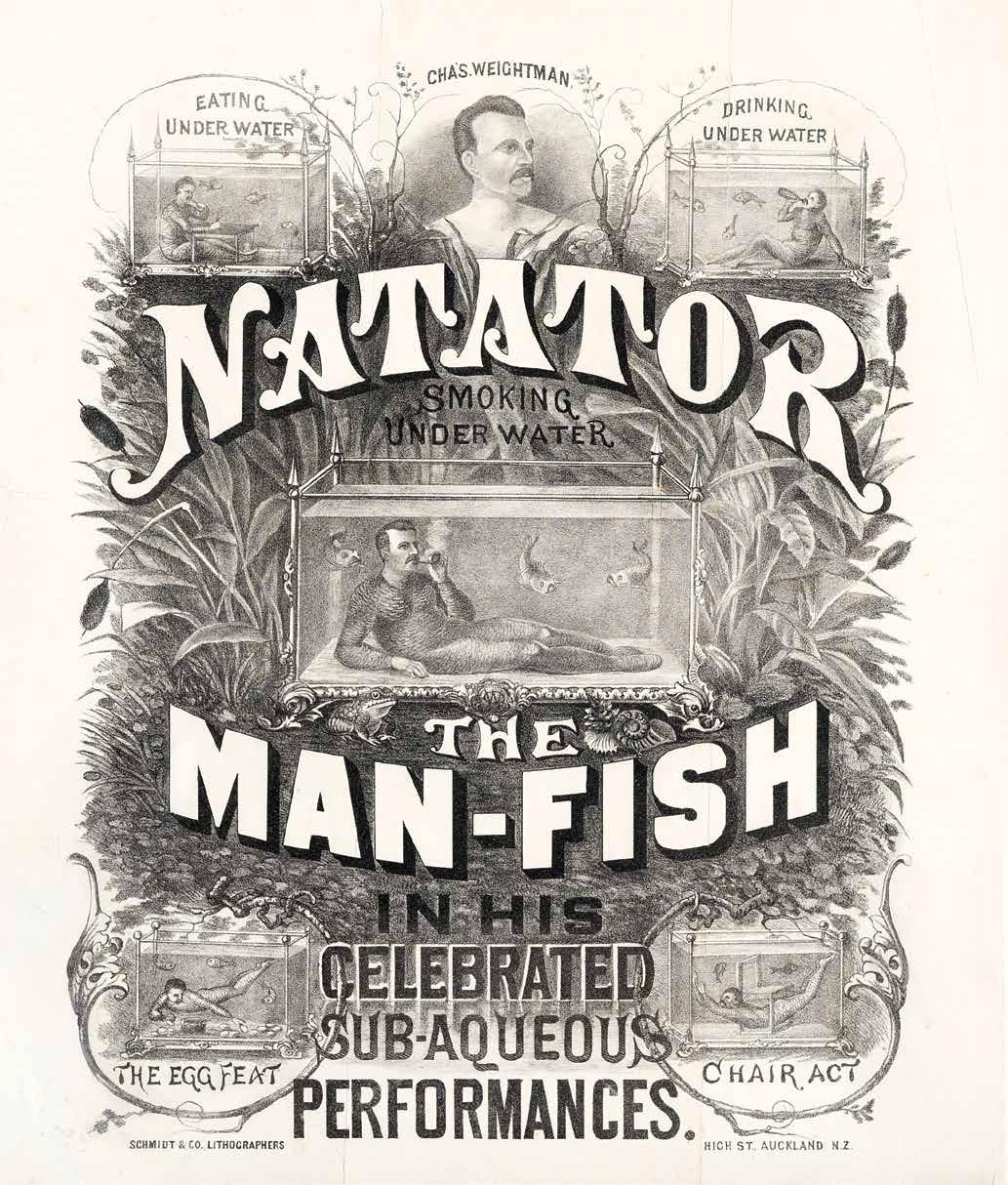

Sally’s chosen favourites include other objects bound to raise a smile, such as the lithograph poster advertising sub-aqueous entertainer Charles Weightman. He could, apparently, smoke a pipe underwater, and performed in England, Australia, New Zealand and America from the 1860s to 1880s.

Titled ‘Natator The Man-Fish’, the poster, which Sally says has never been on display, includes five vignettes from his stage performance – ‘Eating underwater’, ‘Drinking underwater’, ‘Smoking underwater’, ‘The egg feat’ and ‘The chair act’.

‘Man-Fish’ demonstrated his skills at the Queen’s Theatre in York Street, Sydney, from August to September 1874, followed by a performance as part of a Christmas festival at Sydney’s Exhibition Building in December 1874.

He would dive to the bottom of the tank, where he sat and ate a plate of bread and butter and then drank a bottle of milk. His next feat was to smoke a pipe, before performing the chair act, which involved repeatedly swimming with fish-like ease between the legs of a chair secured to the bottom of the tank.

‘The Chair Act?’, Sally asks. ‘What’s not to love about the Chair Act?’

As you would expect, Sally and her team know the precise number of objects in the collection – it stands at 162,454. Of those, 590 were accessioned (added to the collection) in 2024. Last year 2,760 items were digitised, 3,713 items were photographed, and 18,794 objects were moved or inventoried. Sally notes:

Our role is quite diverse, with a skill set ranging from forklift driving to computer coding. When we acquire things for the collection, whether it’s a donation or a purchase, we work with the curatorial and conservation teams to assess whether we’ve got the resources to care for it and whether we should bring them in. So if it’s a very big acquisition, then I would try to get some additional funds to process it.

It is important to us that the collection is documented and accessible to our staff and the public. My team will then accession the item, give it a unique number and description in the database, photograph it, locate it and put it in storage and keep track of it from then on.

We work with the exhibition teams to physically move objects on or off display. If we borrow objects from other individuals or organisations, it’s my team who negotiate and issue loan agreements, so there’s a lot of risk assessment.

‘Man-Fish’ would dive to the bottom of the tank, where he sat and ate a plate of bread and butter and then drank a bottle of milk

Illustrated poster advertising English-born entertainer Charles Weightman, who performed aquatic feats as part of popular stage entertainments from the 1860s to the 1880s.

ANMM Collection 00051367

We also work with international freight agents on pieces like James Cameron’s DEEPSEA CHALLENGER submersible, for instance – that was a massive job. It came from the United States, from Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut. Every step of the way was very carefully planned and managed

Of course, many objects are of perhaps greater historical significance than the examples above. Among the ten massive sliding racks in the small objects storage area is the remarkable log of Henry William Downes, master of the appropriately named whaling barque Terror during its round trip from Sydney into the Pacific Ocean in 1846–47.

Terror was one of many whaling ships owned by the colourful and controversial entrepreneur Benjamin Boyd, a Scottish adventurer and a prominent figure in the history of whaling in early colonial Australia. It was Boyd who established the whaling base Boyd Town in Twofold Bay in southern New South Wales.

01 Inside front cover of a journal of the whaling barque Terror, written and illustrated by the ship’s master, Captain Henry William Downes. The 90-page manuscript describes a journey out of Sydney from 7 September 1846 to 17 July 1847. ANMM Collection 00038301

02 The skull of a merino ram forms the base of the Intercolonial Sailing Carnival trophy. ANMM Collection 00048268

Sally and her team know the precise number of objects in the collection –it stands

at 162,454

Senior curator Daina Fletcher recognised the importance of the logbook when it came up for auction and persuaded the museum’s management and governing Council to provide the additional funding needed to purchase it.

Downes was a skilled and lively writer, and he conveys vividly the spirit and the language of those intrepid times. He was also an accomplished watercolour artist, and his written account is complemented by his own illustrations. The log contains about 50 views of different places visited during the 10-month cruise, along with 25 illustrations of whales and 25 paintings of ships, rigging and crew members.

He writes of their first kill of a whale:

His spout about this time was nearly all blood an evidence that he was deeply wounded. Still he was not all ours for unfortunately the boats got foul of each other & ours had to pay out line & retire a little from the active warfare – fortunately we left him in able hands the 2nd Mate whenever he had a chance driving his lance into the whale & Jackey Nahoe (3rd Mate) alternately swearing and roaring out like a madman in broken English as he sent his lance home, hit him hard he has no friends hurrah, hurrah, look out for your boats, he is dying,

he is in his flurry, and so he was going round at no small rate, described a complete circle turned his head up towards the Sun & resigned himself over to the slayers. This terminates my first encounter with a Whale ‘thank God’ without any incidents Sure a plank or two being smashed in one of the boats the Ship worked up to us & the monster was secured alongside his length can not be less than 50 feet ...

‘I think it’s a rollicking story!’ Sally remarks. ‘Our volunteers have transcribed it and we have photographed it. I think it is quite beautiful.’

Closer to home is one other item that is among Sally’s chosen objects. It’s the John Walker Intercolonial Sailing Carnival trophy in the form of a cigar and cigarette stand with silver ashtray and lid set into a merino ram’s skull. It was awarded to the Australian champion 22-foot skiff from 1896.

‘It’s like an urn on little wheels,’ says Sally. ‘I think that’s one of my favourites. I don’t think it has ever been on display – I don’t know why!’

Tim Barlass is a journalist who has worked for The Sydney Morning Herald and is now researching stories for the museum’s Journeys project, which will revitalise its permanent galleries.

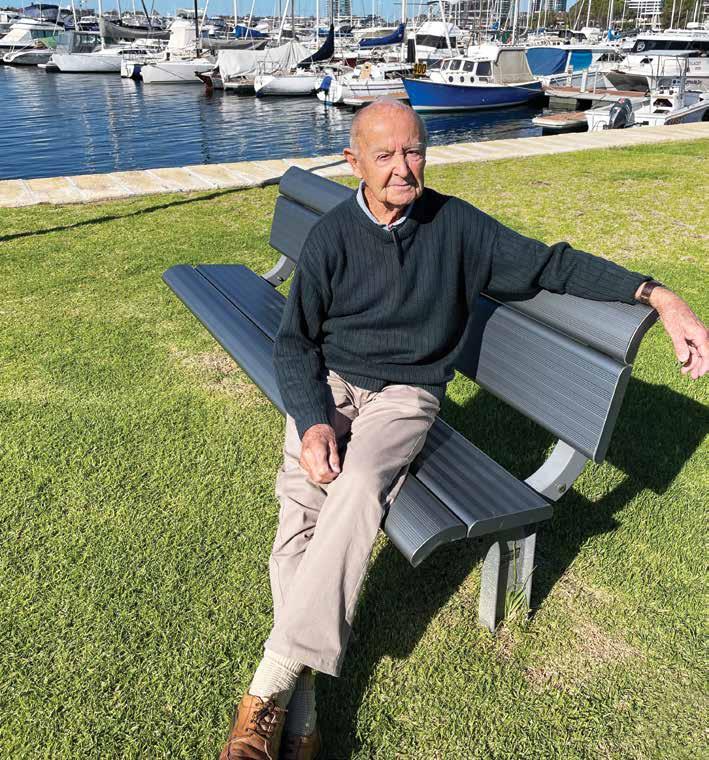

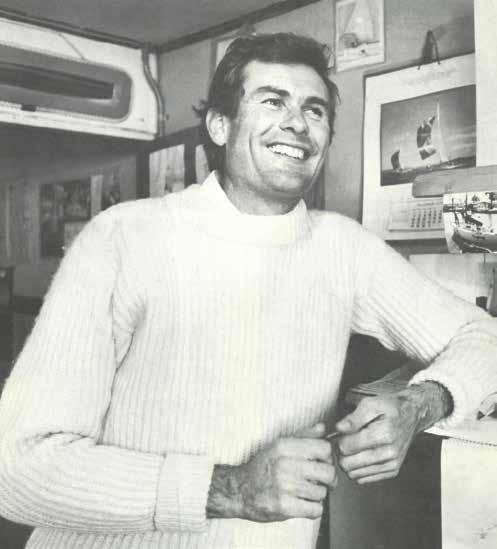

Len has always emphasised giving equal importance to the artistic quality of his designs

Highly regarded Western Australian naval architect, boatbuilder and yachtsman Len Randell was honoured in 2024 with an OAM for his contributions to the maritime industry. David O’Sullivan chats with Len about his approach to vessel design and of notable memories from his long career.

LEONARD ‘LEN’ RANDALL is known for his innovative and ‘do it yourself’ approach to boatbuilding, which has won over fans to his practice far beyond the reaches of his native Swan River. His name is widely associated with a broad range of recreational and service vessels across Australia, from champion racing dinghies to tall ships, cray boats and ferries. While investigating historic boats in my own work, I have often found myself exclaiming with a smile, ‘Oh, it’s another one by Len’.

Len was born in 1926 in Perth, Western Australia, and spent most of his childhood down on the Swan River waterfront and surrounding waterways. He started sailing at the age of eight, as a bailer boy with one of the founding members of the Maylands Yacht Club. In 1941, aged 15, he constructed his first vessel, a 16-foot hardchine dinghy. Len remembers this first build and how the process of boat design came naturally to him:

The only way I could earn money was as a postman in the school holidays. So any money I could make I would save, and that went towards sheets of plywood and whatever I could find in the way of timber. I made the sails myself and it was quite a successful little boat. I sort of knew about design intuitively – the mathematics of displacement and trim sort of all came naturally before I studied naval architecture. I had already been designing model aircraft when I was 12 and this helped.

Len left school at an early age to become an apprentice electrical fitter with the Public Works Department. A year after he completed his apprenticeship he was appointed as an assistant supervisor, and then a supervisor, for infrastructure projects across regional Western Australia. At age 22 he covered projects across three-quarters of the state, including large stretches of the Kalgoorlie water pipeline.

When Len was struggling to get going with his own business, a saviour came in the form of the crayfishing industry

During his time with the Public Works Department Len studied naval architecture books in his own time, formalising early design skills he had developed. He then began to create his own designs, initially focusing on keelboat racing yachts. In 1952 Len made a submission of his work to the Royal Institute of Naval Architects and was accepted as an associate. He was the first person to achieve this accreditation in Western Australia. Some of his notable early designs include Rugged, the winner of the first Cape Naturaliste Yacht Race in 1955, and Rebel, an 18-foot keelboat and the second of its kind on the Swan River. Despite these early successes Len did struggle to get going with his own business:

From my point of view I battled, because no one knew what a naval architect was, and I had to take jobs helping to build boats and working in the retail industry, whatever was available.

A saviour came in the form of the crayfishing industry, where Len saw an opportunity to improve upon the old-fashioned heavy displacement sailing boats used at the time. He recalls the proposition he made in the late 1950s to a worker in the industry in Geraldton:

I said why don’t we do a high-speed boat, you’re not carrying a heavy product, you haven’t got a huge range to go to catch the crays, so I’ll design a 30-footer to do about 13–14 knots instead of 6–7 knots.

To say this design took off would be an understatement. For the next 50 years Len was designing high-speed cray boats for the industry. These designs included large 70-foot multihull vessels with maximum speeds of up to 30 knots. His cray boat success provided a gateway to other fishing boat designs, including the first 54-foot prawn trawler for Shark Bay, on the far north coast of Western Australia.

Len’s name started getting around following his successes with fishing vessels, and he began designing a wide range of different watercraft. He designed tugboats for Geraldton Harbour, workboats for Port Hedland and Dampier, ferries in Perth, and patrol boats. In the early 1970s, he recalls, he designed 26 boats of differing sizes in one year. Throughout this period he preferred to work by himself, aside from two years where he employed an engineer–designer to help with prawn trawlers. Len has always emphasised giving equal importance to the artistic quality of his designs:

Everything had to look nice, no matter what it was. If the proportions weren’t right, I wouldn’t do it. I’ve heard it said that John Longley [crew member of Australia II ] said he’s never seen me design an ugly boat. Well, that’s quite correct, I wouldn’t have an ugly boat!

Len Randall on the Swan River in front of the Perth Flying Squadron, 1945.

Image courtesy Len Randell

Wootakarra served as the primary tug for Geraldton Harbour during the 1970s. Image courtesy Len Randell

Len studied naval architecture books in his own time, formalising early design skills he had developed

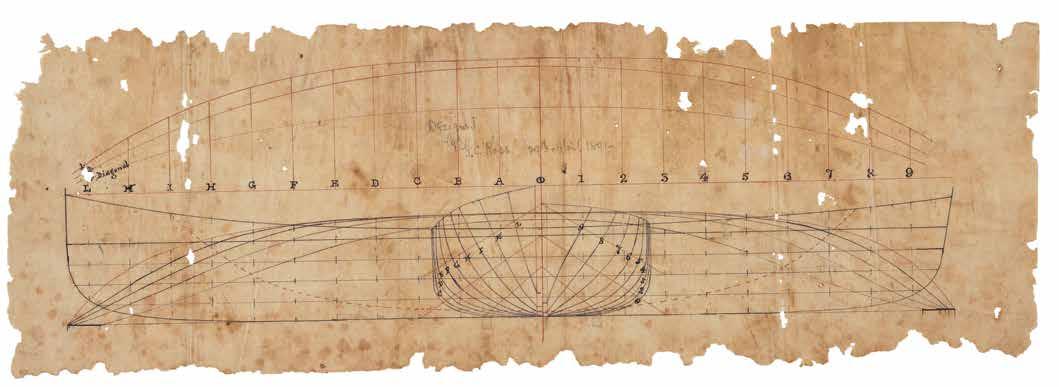

One of Len’s most visually impressive designs is the tall ship STS Leeuwin II, built in 1986 for the Sail Training Foundation of Western Australia

01

STS Leeuwin II off the Kimberley coast of Western Australia, 2008.

Image courtesy Leeuwin Ocean Adventure Foundation

02

Len Randell at the South of Perth Yacht Club in 2024.

Image courtesy Western Australia Museums

One of Len’s most visually impressive designs is the tall ship STS Leeuwin II, built in 1986 for the Sail Training Foundation of Western Australia. The 180-foot, three-masted barquentine is Australia’s largest sail training ship and offers programs enabling young people to develop core life skills. Sadly, in August 2024 Leeuwin was hit by a container ship and sustained extensive damage to its rigging. In May 2025, Leeuwin was moved to the Australian Marine Complex in Henderson, Western Australia, where it will receive a full set of sails and a new rigging system. The STS Leeuwin Foundation intends to have the ship sailing again by the end of 2025.

When asked to name his favourite design, Len stressed that what he most liked was the design process. The 73-foot Hydroflite ferry, launched in 1973, was one vessel where Len believes he got the design perfect. This was the first fast ferry for Rottnest Island. Built with a composite aluminium frame and plywood shell, it had a top speed of 29 knots on an almost silent engine. RV Flinders was another design dear to Len, the first research vessel specifically designed and built for the State Fisheries Department. Local sailors might nominate as their favourites Len’s champion 14-foot sailing dinghies, many of which won Australian titles in the 1950s.

Len notes that he is ‘always looking for the next day ahead, not the one behind’. In this spirit, at the age of 54 he took up glider flying. This was an easy skill to learn for someone who had been sailing for 46 years:

Soaring in a sailplane is a bit like going to windward in a racing yacht. You’re up as high as you can without stalling, you’re at an angle of 45 degrees just before the stall, so you can get the maximum lift at minimum speed. It takes a lot of skill to get it perfect, and you get to love the feeling when you do, it’s just like a good racing yacht. I only gave up gliding when I was 90.

Now 99 years of age, Len continues to skipper his Sparkman & Stephens 34-footer in the Wednesday races at the South of Perth Yacht Club. Len has contributed much to the maritime industry and, in the most genuine way possible, is a true inspiration to both newcomers to the boating world and his peers. Congratulations on your OAM, Len, and here’s hoping we see you out on the water for many more years to come.

David O’Sullivan is an Assistant Curator in the Maritime Heritage Department of the Western Australia Museum.

This article originally appeared in the Australian Association for Maritime History Newsletter Issue 160, September 2024, and is republished here with permission.

Gwenda Moulton (later Garde) was one of the first recruits to serve in the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service during World War II. Now aged 102, she lives in Orange, NSW, and recently recalled her wartime experiences during a video interview with museum staff.

GWENDA MOULTON, AGED JUST 19, sat with several other young women in their green uniforms in a small room at HMAS Harman outside Canberra.

It was 1942 and the newly qualified telegraphist had been listening to Japanese Morse code messages over her headphones. She was well into her evening shift when, without warning, came the most important signal that she knew.

It was ‘RS NO’ (the telegraphists knew it as ‘RS negative’) – the Japanese codeword for ‘submarine’ – which always caused great excitement.

‘As soon as you heard that, you called out to your leading hand,’ Gwenda said:

She would then dial the direction-finder operator who was way out up on a hill in the country. He would contact other direction finders and they would cross reference their bearings to get a fix on where the Japanese submarine was.

Other Morse messages that Gwenda received were sent by teleprinter to Melbourne, where they were decoded. There were Japanese submarines all up and down the east coast of Australia at the time, but Gwenda and her colleagues were never told if any of them had been sunk.

It was a time of change for the forces in Australia, notes Margaret Otter, former Acting First Officer of the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service:1

What! Women in the Royal Australian Navy? Good gracious no. The response from officialdom was if women wanted to dress up and do something to help the war effort, why, they could work in a canteen or take a job in a factory or carry on with their knitting in a woman’s proper place, the home.

But even before World War II was declared on 3 September 1939, several women’s voluntary organisations had sprung up, despite the derision heaped upon them.

One was the Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps, started in Sydney by Florence McKenzie. At the time, girls and women were barred from joining any of the services in Australia, but ‘Mrs Mac’, as she was affectionately known, foresaw a future need, and voluntarily trained those who were willing to learn wireless telegraphy.

Such was the bureaucracy that not until 18 April 1941 – 18 months into the war – did the Minister for Navy reluctantly approve the employment of telegraphists for HMAS Harman, the navy’s communications base. But there was a proviso – no publicity should be given to the break in gender tradition.

‘Mrs Mac’, as she was affectionately known, voluntarily trained girls who were willing to learn wireless telegraphy

01

Petty Officer Gwenda Moulton outside the cottages at HMAS Harman. Image courtesy Gwenda Garde

02

Florence McKenzie, the founder of the Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps (WESC), was known to her students as ‘Mrs Mac’. Image Australian War Memorial P01262.001

Gwenda was among those first 48 recruits:

I heard about Mrs McKenzie and went to her classes in Clarence Street. She was the first female electrical engineer, founder of the Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps and a lifelong promoter for technical education for women. She was a little woman, not much bigger than me at five foot, but about 20 years older. She was quite stern with you; you had to do what she said.

One day Mrs Mac said that the girls were going for a Morse test, and that Gwenda had better come for the experience. Gwenda passed, and the next thing she knew she was joining the navy in late December 1941.

Mrs Mac got the navy, with great difficulty, to take girls – I was WRANS number 36. When we got to our accommodation, they wanted us to paint the place, to camouflage it. The male telegraphists went off to sea and we moved into their cottages.

They ate in the mess, the girls on one side and the remaining men on the other. There was a dance every Saturday night in nearby Canberra. Gwenda would dance with boys from the army and air force but she and the other telegraphists weren’t allowed to date naval officers, who were considered to be above them.

Gwenda didn’t speak about her wartime role to anyone until the COVID-19 pandemic

01

Gwenda, front left, and her fellow telegraphists on pay day at HMAS Harman. Their dark green and gold uniforms were designed by Florence McKenzie.

02

Studio portrait of Gwenda Garde, taken for the project ‘Reflections – Honouring our World War Two Veterans’, 2015–17, Australian War Memorial. Image AWM2017.520.1.1183, photographer Melissa Montagliani

As soon as the war ended, Gwenda was taken off Japanese transmissions and was charged with listening to the Russians instead: ‘I thought that was terrible because the Russians were our allies.’

Later, Australian prisoners of war came through Townsville after their release: ‘They were so emaciated; it was so sad to see them,’ Gwenda recalls.

Gwenda didn’t speak about her wartime role to anyone until the COVID-19 pandemic, when she sat down with her daughter Robin and told her the complete story.

The female telegraphists were divided into two lots of 12. One lot went to the regular station and did ordinary communications, but Gwenda’s group went to a separate location, called Y Hut. Theirs was important work, but so secret they didn’t know what the other people on the base were doing. They weren’t allowed to talk about it and they had to learn the Japanese Morse, which was slightly different from the Australian version:

The Japanese didn’t know, but we had their code books and we knew, for instance, what their signal was for ‘submarine’. It was dit dah dit / dit dit dit / dah dit / dah dah dah [ .-. ... -. ---].

The telegraphists knew quite a lot of the frequencies that the Japanese used, and would listen in to different frequencies until they heard something they knew was Japanese. After writing it down in Morse code, they then had to transcribe it into letters (kana) so it could be sent on the teleprinter to Melbourne. They were never told what kana was.

‘It’s a funny thing, but you got to know the Japanese a bit’, Gwenda remembered. ‘They could be very cross with each other, you could hear the tension in their sending.’

By 1944, Gwenda was a petty officer in charge of 42 girls, based in Townsville. Dengue fever was rife and everyone seemed to get it eventually.

At the start of the war, Gwenda had had a steady boyfriend, Robert, a Spitfire pilot who was killed when he was shot down over the North Atlantic. After the war she married his best friend, John, who had flown Kittyhawks in New Guinea. They had three children and their eldest daughter, Robin, said: ‘Mum may be 102, but she’s as bright as ever and playing bridge four times a week – and still winning!’

Australian National Maritime Museum historian and curator Dr Roland Leikauf, who interviewed Gwenda, sees the Morse code WRANS as another case in which a wartime shortage helped women break gender barriers in a reluctant, male-dominated world.

Florence McKenzie’s school later trained men as well as women, and by August 1945 it had instructed some 12,000 men in Morse code, visual signalling and international code. After the war, the school continued its work, training 2,450 civil airline crewmen and 1,050 merchant navy seamen by 1952. The school closed in 1955. ‘Mrs Mac’ was awarded an OBE in 1950 and died in 1982.

1 Margaret Curtis-Otter, 1975, WRANS: The Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service, Naval Historical Society of Australia, Garden Island, Sydney. Vaughan Evans Library 359.00994 CUR

Written by Tim Barlass, based on a video interview conducted with Gwenda Garde by museum curator Dr Roland Leikauf.

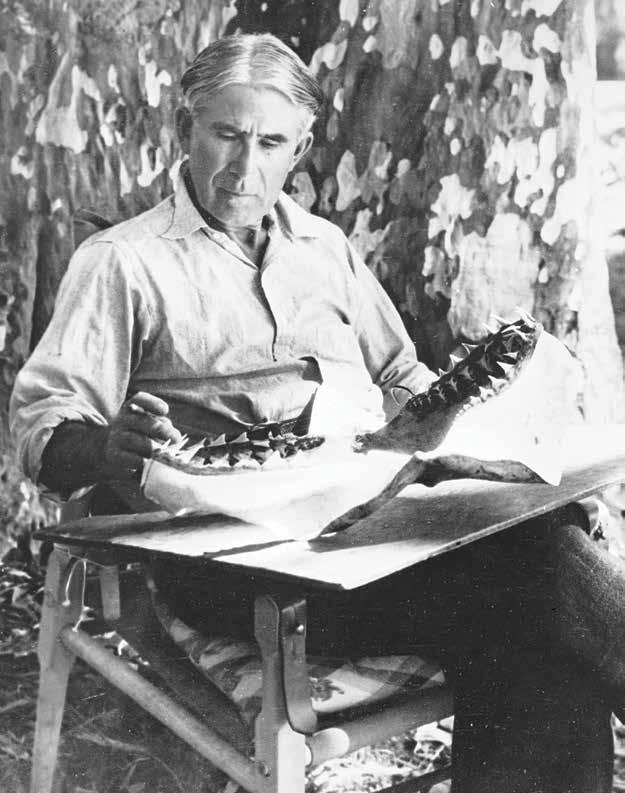

Zane Grey was the world’s first millionaire author, inventor of the Western in both literature and Hollywood films, and globally feted as a celebrity adventurer. He made two trips to Australia in the 1930s to pursue the new sport of game fishing. The following extract from Vicki Hastrich’s new biography, The Last Days of Zane Grey, describes his catch of a world-record tiger shark off Sydney in 1935.

UNDER A CANOPY OF BLUE SKY on the morning of Thursday 9 April, just before the Easter weekend, the ocean was finally calm. It was a perfect day for fishing, warm and still, and Zane Grey left the Palace Hotel early. Out through the Heads they motored with the wily Billy Love on board, who soon had them trolling for bait on the way to Bondi. Then the serious fishing began. First, they chugged out to sea about sixteen kilometres, then north and in towards Manly Beach, at length settling to anchor directly in front of the entrance to the harbour and scarcely a kilometre and a half out – Billy’s favourite shark ground. There could not be a more scenic place to fish. In short time a small shark was caught.

Telling the story in An American Angler in Australia, Grey says Billy Love was gleeful: ‘Shark meat best for sharks. Now we’ll catch a tiger sure!’

With the care and expertise of a modern-day sushi chef, Billy tied a well-cut piece of shark to the hook and added a fillet to hang from the point. Then he let the unweighted bait sink around 45 metres. It was noon.

Zane Grey fishing from the Avalon on location for the filming of White Death, Hayman Island, Queensland, 1936, with shark expert Billy Love (left) and boatman Peter Williams. Courtesy Ed Pritchard

Grey, who had caught thousands of fish, shook at the possibilities of this one

After lunch Grey settled into his fishing chair and the patient game of waiting began. In the hot sun, with his feet up on the gunwale, there was no place he’d rather be. The sea had the slicked look that calmness sometimes brings, beautiful in the extreme and compelling. Time became atrophied, inconsequential, uncountable, irrelevant in the long lazy lull of the afternoon. The crew dozed. Hours slipped by, but Grey was content watching the water and the birds. He stayed in his fishing chair, dreamy but attuned.

By four o’clock in the afternoon and still with no bites, the crew were bored, ready to give up and go home. But Grey demurred, mildly reproaching them, reminding them of the time he fished for eighty-three days without a bite before catching his giant Tahitian striped marlin on the eighty-fourth (the incident is said by some to have inspired Hemingway’s novel The Old Man and the Sea). The boatmen, the cameramen – he was paying their wages, and there was no question of any real dissent. He was their boss. But it was clear to Grey his crew thought staying was a waste of time.

‘We’ll get one tomorrow,’ said Billy Love.

‘Ump-umm. We’ll hang a while longer,’ drawled Grey, in what he confessed was cowboy parlance.

‘The afternoon was too wonderful to give up,’ he wrote of that moment. ‘A westering sun shone gold amid dark clouds over the Heads. The shipping had increased, if anything, and all that had been intriguing to me seemed magnified.’

A feeling of sureness grew in him. Something was out there. It was as if, in his languid state of alertness, he was calling it up, patiently creating the right conditions for it to arrive.

And then it happened. Slowly but firmly, the line on Grey’s reel began to pull out. Slowly, steadily, potently, it slipped off the big Kovalovsky reel. Grey told Peter Williams it was like nothing he’d ever felt before, like someone with their fingers on his coat sleeve drawing him slowly towards them. Grey, who had caught thousands of fish, shook at the possibilities of this one.

01

Zane Grey examining the jaws of a great white shark at his writing desk, Batemans Bay camp, NSW, 1936. Courtesy L Tom Perry Special Collections

02 Grey with catches at his Bermagui camp on the New South Wales south coast, 1936.

by TC Roughley, courtesy State Library of NSW

Time became atrophied, inconsequential, uncountable, irrelevant in the long lazy lull of the afternoon

Beside the boat the water boiled, then split to show the wide, flat back of an enormous shark

01

Courtesy State Library of NSW

02

A radiant Billy leaped forward to pull up the anchor: ‘Starts like a tiger!’

Emil Morhardt rushed to help. Peter Williams got the engine going.

Three hundred, four hundred metres of line the mystery fish took – and more – until Grey threw on the drag and struck, reeling fast and hard and repeating the action four or five times. When he finally came upon the full weight of the fish, the response was so violent it lifted him clear of his chair.

What sort of fish it was they still couldn’t tell for sure, but they knew it wasn’t a marlin. Its behaviour was changeable. For a while it went light, then it went heavy – heavy in the way of something more-than-ordinarily huge. Forced after one run to apply more drag on his reel than he’d ever done in his life, Grey thought it must be a shark, but maybe a species no one had ever seen.

With the creature taking line and Grey struggling to get it back, the fight seesawed, becoming more and more operatic as the afternoon wore on, played out just as Grey had originally envisioned, albeit with a different fish, in front of one of the world’s great backdrops. Sunset came, lighting the sandstone cliffs of the Heads and turning the sea gold-blue. And as the sky further darkened, a procession of five ocean liners passed close by, towering over [their fishing boat] the Avalon, lights glittering, all of them getting out before the shutdown of the port on Good Friday. Passengers on deck waved, recognising the Avalon and the famous man struggling with bended rod at the stern.

Just as the battle between man and fish reached a desperate stage, the revolving beam of the Hornby Lighthouse switched on, raking the Avalon ’s deck and surrounding ocean.

The sea had the slicked look that calmness sometimes brings, beautiful in the extreme and compelling

Grey, drawing on his last reserves of energy, got back more line, and when finally the leader sprang into view, men leaped to action. Beside the boat the water boiled, then split to show the wide, flat back of an enormous shark, pearl-grey in colour, with dark tiger stripes and an immense, rounded head. Grey, expecting a hideous beast, was shocked by its beauty.

Amid churning water and roaring shouts, the shark rolled, showing its white belly and opening its mouth wide enough to take a barrel before snapping its jaws audibly shut. In a deluge of splashing water, Billy Love roped the tail, the barefoot boatman instinctively using the leverage provided by the movement of the boat to his advantage.

Grey had a world-record shark.

The Last Days of Zane Grey is published by Allen & Unwin, Sydney, ISBN 9781761471452, RRP $35.00.

Vicki Hastrich is a Sydney writer and oral historian. She is the author of Night Fishing , The Great Arch and Swimming with Jellyfish

On Sydney’s Cockatoo Island/Wareamah, two very different historic vessels are being brought back to life under the stewardship of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.

THE SYDNEY HARBOUR FEDERATION TRUST (Harbour Trust) manages sites around Sydney’s foreshore that have both national and international significance. They are places of natural beauty, and also feature heritage structures and remnants from different eras. Two current projects aim to restore historic vessels. Fast Motor Boat (FMB) No 45802 Sydney (dating from 1945) served as captain’s launch on aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney (1948–1973). The ferry Fitzroy (1928) had a much humbler, workaday existence, transporting dockyard workers to and from Cockatoo Island. In their different ways, these vessels played vital roles in Australian maritime history and are now the focus of meticulous restoration efforts blending traditional craftsmanship with modern conservation techniques. There’s something deeply moving about restoring vessels like Fitzroy and FMB Sydney. You’re not just repairing wood and metal – you’re reviving the stories of the people who built them, sailed them, travelled in them and kept them alive. Every detail we preserve is a tribute to their legacy.

The Fitzroy ferry in Fitzroy Dock in June 2025 awaiting restoration, with three of the Harbour Trust’s heritage cranes behind. Image Ed Hurst

Dating from 1928, Fitzroy is one of only two remaining vessels constructed by Cockatoo Island Dockyard apprentices

Tides of time on Cockatoo Island

Cockatoo Island sits at the confluence of the Parramatta and Lane Cove rivers in Sydney Harbour. It’s been much developed over the last two centuries, and it’s hard to picture the smaller, wooded island that was there before colonisation.

When you visit Cockatoo Island, there are many layers of history and heritage. You can see the dockyards overlaid on the convict history. In turn, all of that was layered onto First Nations history, as people have been living for tens of thousands of years in and around the valleys that flooded to form Sydney Harbour. When you arrive, all these layers hit you at once and it’s hard to grasp what you’re looking at. The Sydney Harbour Federation Trust’s vision is not just to preserve heritage but to make all of the layers accessible and meaningful – for everyone to enjoy and appreciate.

Janet Carding (Executive Director), Sydney Harbour Federation Trust

From 1839, the island was a convict gaol, and many of the buildings from that period survive to this day. From these beginnings, Cockatoo Island’s dockyards came to play an important role for well over a century, including as a major shipbuilding and repair facility (in use from 1857 to 1991). Cockatoo Island served the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), which was critical in enabling the Allies to fight during both world wars. By the 1960s, commercial work was declining. The last ship was built on the island in 1984; the final submarine was refitted in 1991. After 134 years, history had caught up with Cockatoo Island shipyard and it closed the following year.

Much equipment was removed and some buildings were demolished. Yet so much remains that the island has become a time capsule. The Harbour Trust’s master plan explains that the island’s future is in ‘telling its stories’ in accessible and interesting ways. It’s about bringing the historical people and crafts of the island to life –something which is certainly aided by the restoration of boats.

Of course, the Harbour Trust covers more than Cockatoo Island. It also runs North Head Sanctuary in Manly, Sub Base Platypus in North Sydney and the precincts of Headland Park, Mosman – Chowder Bay/ Gooree, Georges Heights and Middle Head/Gubbuh Gubbuh. The agency also manages Woolwich Dock and Parklands, Macquarie Lightstation in Vaucluse and the former Marine Biological Station at Camp Cove.

The rebirth of a navy motor boat

Dating from 1945, Fast Motor Boat (FMB) No 45802 is a 30-foot timber captain’s launch, built in England by Vosper for the aircraft carrier HMS Terrible (renamed HMAS Sydney when it was sold to Australia in 1947). It features double diagonal mahogany plank construction, making it strong and light.

HMAS Sydney operated as the flagship of the RAN and saw action during the Korean War before being modified as a fast troop transport and deployed to Malaysia. It conducted 25 trips to Vietnam between 1965 and 1972. In 1973 it was decommissioned and broken up in South Korea.

Thankfully, the vessel survived and is now the only cabined captain’s launch of this vintage surviving in Australia, making it of great historical interest (it was listed as part of the Naval Historical Collection in 1984). After an extended period out of action on Spectacle Island in Sydney Harbour, in 2000 the Harbour Trust took custody of it and moved it to be restored at Chowder Bay. The captain’s launch became a Work for the Dole project; local people received training in boat building and repair, making a significant contribution. It was at this time that the vessel was named Sydney

By 2008, the next overhaul was required, and this took place at the vessel’s new home, Cockatoo Island, by Harbour Trust restoration volunteers. The trip from Chowder Bay was made using the original Crossley engine; the term ‘fast’ motor boat no longer really applied, but the venerable machine made it eventually! That repair involved a replacement engine, overhaul of the propeller shaft and steering, restoration of the woodwork and an overhaul of the electrical system –before a major relaunch in 2010.

In 2019, its third restoration began, and after delays during the pandemic, it is now complete – with work having been carried out on the hull, engine and the interior. The main tasks that lie ahead before relaunch are the survey process and steps required to permit it to carry the public.

01

Original Crossley engine from Fast Motor Boat Sydney, which was replaced after it was used to move the vessel from Chowder Bay to Cockatoo Island before the restoration that began in 2008. Image Sydney Harbour Federation Trust

02 Harbour Trust Executive Director, Janet Carding, Cockatoo Island heritage restoration volunteers and Director of Heritage and Design, Libby Bennett, stand proudly in front of Sydney at an event on 17 June 2025 to celebrate its completed restoration. Image Ed Hurst

02

FMB Sydney is now the only cabined captain’s launch of this vintage surviving in Australia, making it of great historical interest

Fitzroy ferry comes home

While FMB Sydney travelled widely, the 30-foot ferry Fitzroy is genuinely an unsung hero. Dating from 1928, it was designed by naval architect David Carment and is one of only two remaining vessels constructed by Cockatoo Island Dockyard apprentices. It was built from spotted gum and fitted with a large two-stroke engine, its exhaust point exiting through the roof. The engine used ‘direct air start’ – a system that involved charging two large gas canisters with compressed air. Reversing required the engine to be stopped and run in the other direction. Coolant was circulated through a system of tubes outside the hull.

The vessel played the vital role of ferrying dockyard workers to and from the island. It was also deployed to move materials around the island.

Upon its retirement in 1963, the ferry was sold and replaced by a 40-foot workboat, also named Fitzroy The 1928-built vessel passed into private ownership, changing hands several times. It was renamed Burgundy Belle before reverting to its original name. It resided in Pittwater and underwent a series of modifications, including work in 2008 to fit a Volvo Penta 40-horsepower engine.

Remarkably coming full circle, Fitzroy was offered to the Harbour Trust and they took ownership on 24 April 2024. Fitzroy travelled back to Cockatoo Island under its own power, where it awaits restoration – hopefully in time for its centenary in 2028. What could be better than a group of volunteers playing a major part in returning to service a vessel that was built on the island to serve dockyard workers, in many ways their direct predecessors, so that we can all enjoy it?

The volunteers behind the vision

Janet Carding notes:

There are over 150 Harbour Trust volunteers with a range of different roles and talents. Across all Harbour Trust sites, they contribute over 20,000 hours per year to the organisation – they are amazing and indispensable, and we are in awe of their passion.

Volunteers are not only involved in restorations; they also staff visitor centres, carry out gardening, do conservation work and run tours, among many other things. Many volunteers have ready-made skills, such as engineering, woodworking, metalworking and welding; some have marine and automative backgrounds; others come with nothing more than a desire to help

and a willingness to learn after a lifetime of white-collar work. The Harbour Trust defines and oversees projects, procures materials, ensures safe working methods, provides induction and ensures that everything is certified. But the volunteers do the lion’s share of the work and make ‘the magic’ possible.

Ivan Miklos, a Cockatoo Island heritage restoration volunteer, explains:

The main work in the restoration of the FMB were timber hull and cabin repairs, propulsion system updates, electrical wiring renewal, epoxy resin/glass hull layout and full paint finishing.

This impressive team of volunteers has recently been recognised for their work – winning a ‘Highly Commended’ award in the ‘Enduring’ category at the 2025 National Trust (NSW) Heritage Awards.

People are surprised when they learn that I was a dentist ... The crew is a wonderful collection of people. I have never heard a cross word and everyone is happy to advise and train others where appropriate. The range of skills exercised is remarkable. I can’t think of a task that is outside of our collective skill set.

Andy Moran, Cockatoo Island heritage restoration volunteer

These vessels are now the focus of meticulous restoration efforts blending traditional craftsmanship with modern conservation techniques

Cockatoo Island from the north-west in February 1944. Clockwise from left, TSS Niarana lies at the Plate Wharf; HMAS Hobart is at the Cruiser Wharf; Bataan is being fitted out at the Bolt Shop Wharf; HMAS Arunta is at the Destroyer Wharf during refit; USS Gilmer is in the Fitzroy Dock; HMAS Barcoo is under construction on No 3 slipway; the floating crane Titan lies at the Fitzroy Wharf; LST 471 is at the Sutherland Wharf; HMAS Australia is in the Sutherland Dock; and the cargo ship River Hunter is on No 1 Slipway. From the collection of the late John Jeremy

Of course, restoring a historic vessel is one thing – but being permitted to operate it and carry the public is another. The requirements before FMB Sydney can be registered with the Australian Maritime Safety Authority are complex, especially as it has never been a private vessel, so it will need to be fully ‘in survey’. Fitzroy is on the Australian Register of Historic Vessels (HV000822), which makes the process somewhat less arduous.

Once they are back in use, both vessels will be kept on Cockatoo Island: FMB Sydney on a slipway, as it was constructed to be dry for extended periods; Fitzroy will, by contrast, live in the water, as its construction means that the hull tends to shrink if dry.

Imagine a day, not too far away from now, when both vessels are available for use. It might be possible to travel to a Cockatoo Island Open Day either on a vessel that used to travel the high seas aboard an RAN aircraft carrier, or on a workaday boat built on the spot. Perhaps the boats may circumnavigate the island or even travel to the Harbour Trust’s Woolwich site. This is all possible because of the work of the Harbour Trust and its talented volunteers.

If you haven’t been to Cockatoo Island for a while, now is the perfect time to return and discover new experiences inspired by the island’s rich dockyard history.

To mark World Ocean Day 2025, the ANMM secured a grant to offer free screenings at maritime museums worldwide of the documentary film David Attenborough: Ocean, in partnership with the International Congress of Maritime Museums. By Jasmine Heffernan.

‘If we save the seas, we save ourselves.’

– Sir David Attenborough in Ocean

AMID THE EBB AND FLOW of global environmental and political affairs, museums offer a space for communities to engage with various forms of human expression and historical transformation. Above all, museums are repositories of stories and cultural heritage, continuously adapting to the contemporary world as dynamic institutions of education and inspiration. Maritime museums are uniquely positioned to represent the ocean identity and landscape of their locale, becoming leaders in nurturing environmental empathy and empowering visitors with messages of hope for

the global future. To nurture hope is to also support related organisations in achieving their aims in ocean engagement and awareness.

The theme for the 2025 World Ocean Day, ‘Wonder: Sustaining What Sustains Us’, was perfectly heralded by Sir David Attenborough’s latest documentary –and perhaps his magnum opus – David Attenborough: Ocean. Premiering globally on 8 May, exactly a month before World Ocean Day and the landmark UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France, the documentary urges government bodies to enforce the protection of at least 30 per cent of the global ocean by 2030 – a substantial increase from the current figure of less than 3 per cent.

Playing a greater role than simply that of narrator, in Ocean Sir David leads audiences through his case for hope, with a certitude that the ocean sustains life and is our greatest hope against climate catastrophe. While the documentary flourishes in bringing the playful and magical wonder of underwater realms into focus, it is equally successful in bringing to light appalling episodes of destruction. Following vibrant shots of coral reef oases is neverbefore-captured footage of bottom trawling, a largescale industrial practice that transforms ecosystems once teeming with life into desolate, barren landscapes. And scenes of bycatch, hauled onto ships by the tonne to be then discarded as waste, project a harrowing vision of unregulated overfishing and its indisputable effects on ecosystems and local communities.

But no David Attenborough documentary ends with despair. The chance for recovery is witnessed on-screen within one of the largest marine protection areas in the world, Papahānaumokuākea, a 2,200-kilometre stretch of coral islands in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Such optimistic images of marine protection areas are the crux of the film. Ocean renders what was once hidden in the deep sea visible to an international audience, the message to viewers equally hopeful and daunting: the ocean can recover faster than imaginable, but only if we act now.

The documentary’s timely release provided an opportune moment to propel ocean awareness on an international scale through museum-led World Ocean Day programming. The Australian National Maritime Museum requested permission to organise free screenings at maritime museums worldwide, and subsequently secured a grant from Minderoo Pictures to enable this aim. Twenty-three museums, from Finland to Hong Kong, participated in this global first, collaborative screening event, achieved in partnership with the International Congress of Maritime Museums (ICMM).

An outdoor screening of David

The ocean can recover faster than imaginable, but only if we act now

Housing centuries of exploration stories, knowledge, culture, and artefacts shaped by the sea, maritime museums anchor us to the past and grant insight into the future of our ocean. Maritime museums around the world are supported through the ICMM as a centralised point of contact. An enduring network of maritime museums, diverse in language and locality, further strengthens universal objectives towards ocean engagement and sustainability.

The World Ocean Day screening was a milestone event that demonstrated the strength of international collaboration and unity between maritime museums in supporting the future of our ocean.

Jasmine Heffernan is the museum’s Curatorial Assistant, Ocean Futures.

The museum wishes to thank Minderoo Pictures and the International Congress of Maritime Museums for their support.

Participating museums

AIMS Museo Maritimo, Philippines

Åland Maritime Museum, Finland

Albany’s Historic Whaling Station, Australia

Australian National Maritime Museum, Australia

Bass Strait Maritime Museum, Australia

Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, USA

Hong Kong Maritime Museum, Hong Kong

Maritime Museum of San Diego, USA

Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Canada

Maritime Museum Tasmania, Australia

Mary Rose Trust, UK

Museu Marítim de Barcelona, Spain

Mystic Seaport Museum, USA

National Maritime Museum, Royal Museums Greenwich, UK

New Bedford Whaling Museum, USA

New Zealand Maritime Museum, New Zealand

Promotori Musei Mare, Italy

Seaworks Maritime Precinct, Australia

South Street Maritime Museum, USA

The Tall Ship Glenlee, UK

Vancouver Maritime Museum, Canada

Western Australian Museum, Australia

THE ANNUAL EXHIBITION of the Sydney Model Shipbuilders Club brings together modelling clubs from across New South Wales. This year’s expo, the 11th, will take place in Sydney on 18 and 19 October, and is sponsored by the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Last year’s event was great success, with more than 400 visitors, over 40 exhibitors and nine participating clubs. A great variety of models will be on display this year. Some are built for exhibit only; others can be sailed by radio control. Models made from kits will join others that are ‘scratch built’, meaning constructed from original plans or their maker’s imagination. The models are created from a great variety of materials – wood, metal, plastics, printed resin or even paper – and range in size from a Titanic that is almost two metres long to a tiny 10-centimetre model of HMS Sirius, the lead ship of the First Fleet. Sirius is depicted anchored in Port Jackson in 1788, with its boats alongside ready to row to shore. Ships in bottles always fascinate visitors, and the collection this year includes Titanic sinking, historically accurate with its front funnel collapsed and smoke still emanating from the two middle funnels. The ship has somehow wiggled its way into a whisky bottle supported on an old sailor figurine, and the sea has been angled to compensate for its slope. Mike Kelly will be on hand to demonstrate how he managed to do it.

Each of the exhibiting clubs has a different focus. Many members of the Sydney Model Shipbuilders Club build models of historic sailing ships –HM Bark Endeavour, HMS Victory and clipper ships

are popular choices, while smaller subjects include the schooners that serviced the Australian coast until the early 20th century. Other modellers choose more modern vessels: the fishing trawlers that operated out of Sydney Harbour between the wars, or more exotically, a Chinese junk.

Our sister club in Canberra always makes the trip northward, and among the models they will be bringing is Chindwara, a postwar refrigerated cargo ship of the British India Line, modelled in harbour and about to sail.

Task Force 72 build all of their models 72 times smaller than the real thing, hence their name, and sail them together at regular events. Ships of the Royal Australian Navy are favourites, although many modellers choose warships of World War II as subjects.

The plastic modelling clubs, the Australian Plastic Modellers Association and the International Plastic Modelling Society, show both scratch-built models and those made from kits. Throughout the exhibition, modellers will demonstrate the techniques of their craft. They are happy to answer questions about their methods and to encourage new people into the hobby.

After the show closes at 3.30 pm on Sunday, we will draw a raffle and present awards to the models that visitors have chosen as their favourites. The venue, the Wests Ashfield Leagues Club, has ample parking as well as multiple food outlets. Children of all ages are welcome, and our exhibitors always enjoy talking to them. It makes a great day out and entry is free!

When and where

10 am–8 pm Saturday 18 October

10 am–3.30 pm Sunday 19 October

Wests Ashfield Leagues Club, 115 Liverpool Road, Ashfield, Sydney FREE ENTRY

For queries or more information, please phone Michael Bennett on 0411 545 770 or email mjbennett@ozemail.com.au

01 Visitors to last year’s event admire the models on display.

02

The 2025 expo will feature this model of a Chinese junk. Images courtesy Anelia Bennett

Some models are built for exhibit only; others can be sailed by radio control

THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM FOUNDATION is the museum’s philanthropic arm. With oversight from the Foundation Board and Museum Council, the Foundation offers a transparent, trusted avenue for donors to make a lasting cultural impact.