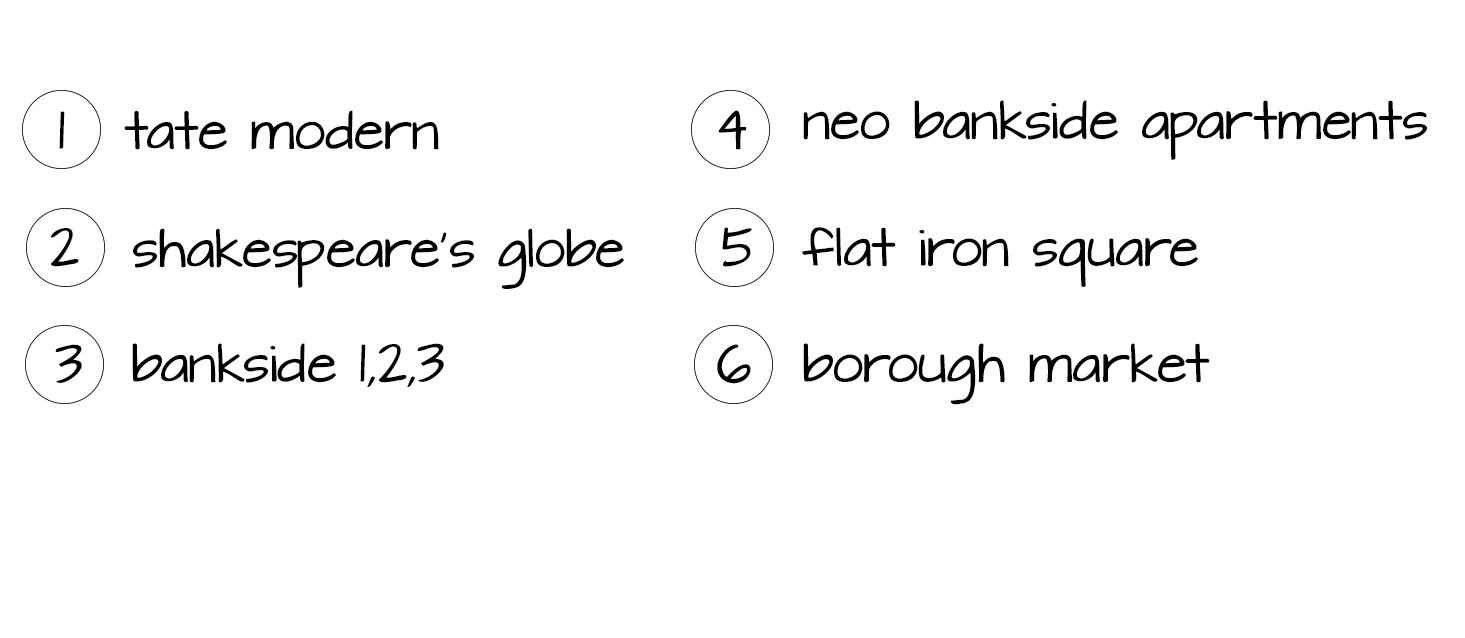

London’s industrial heritage adapted to host the contemporary museum of modern art received more than 40 million people since its opening in May 2000. Bankside’s rich historical layer and the addition of the Tate modern to its urban fabric, forced accelerate an expansion around its surrounding areas. The area encircling the Tate started to be occupied by a ring of commercial buildings, a pattern of growth that has gradually transformed it into a highly desirable place

to work, invest and live. But like much of London, this highly embedded urban scenario brings about the question of a balance between hyper development and considerate urban planning decisions. Tate modern proved to be a great economic success for London and although its success story is much celebrated, did its urban re-generation and integration really take place in a coherent form?

The light industrial sites directly adjacent to the Tate Modern have been transformed into luxury apartment blocks and office buildings, with the social housing estates including the Peabody state and Sumner building in close proximity. This makes it a very discrete mix of low and high-priced residential blocks around Bankside. Although urban regeneration is happening at a substantial scale, some public spaces in Bankside are facing challenges in providing permeability and a sense of accessibility to a certain range of users.

How can design interventions make these historically layered spaces more accessible? How can design interventions make spaces more engaging, and inclusive for the people, take account of its local texture and more collective in the process?

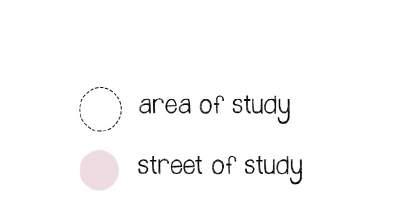

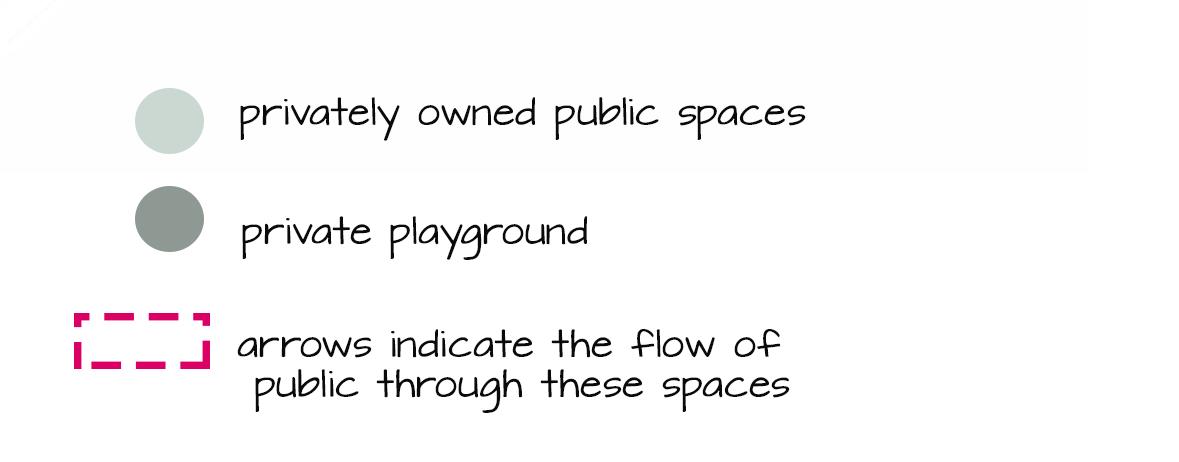

Our research stems from the study and analysis of the public realms in Bankside and their current scenario. Through our investigation of these spaces, we have learned that most of the notable public spaces around Bankside are privately owned and are bound with regulations and restrictions even though they seem barrier free.The Tate’s existence and the many surrounding luxury apartments that have sprung up over the years, has attracted high end business and restaurants catering to the needs of the high-end user groups in the area.

Moreover, the public spaces around them are designed for the tourists, failing to engage other user groups in the area such as the residents, the office workers working in the highly commercialized Southwark street or the decent population of construction workers due to the high number of constructions going on in Bankside.

(Rishbeth,2001)

Our project identifies some notable public spaces in Bankside that seem public but are actually owned by private corporations.When studied, it was found that these places have social and physical inaccessibility issues that exclude a certain user group. This is causing them to lose their “sense of community” and ownership in the area.

The FLAT IRON SQUARE, a railway arch that is an integral part of the historic DNA of Southwark is also a public space but owned by a private body. Currently, its a destination for events, food, and drinks but our studies reveal that like the other public spaces in Bankside, this too has accessibility issues. Our design for a equitable design aims to propose a space that continues to enrich Southwark’s history as a cultural hotspot. The proposal involves design interventions that can help bring the diverse community together, set a stage for civic connections and actively engage them to revive the “sense

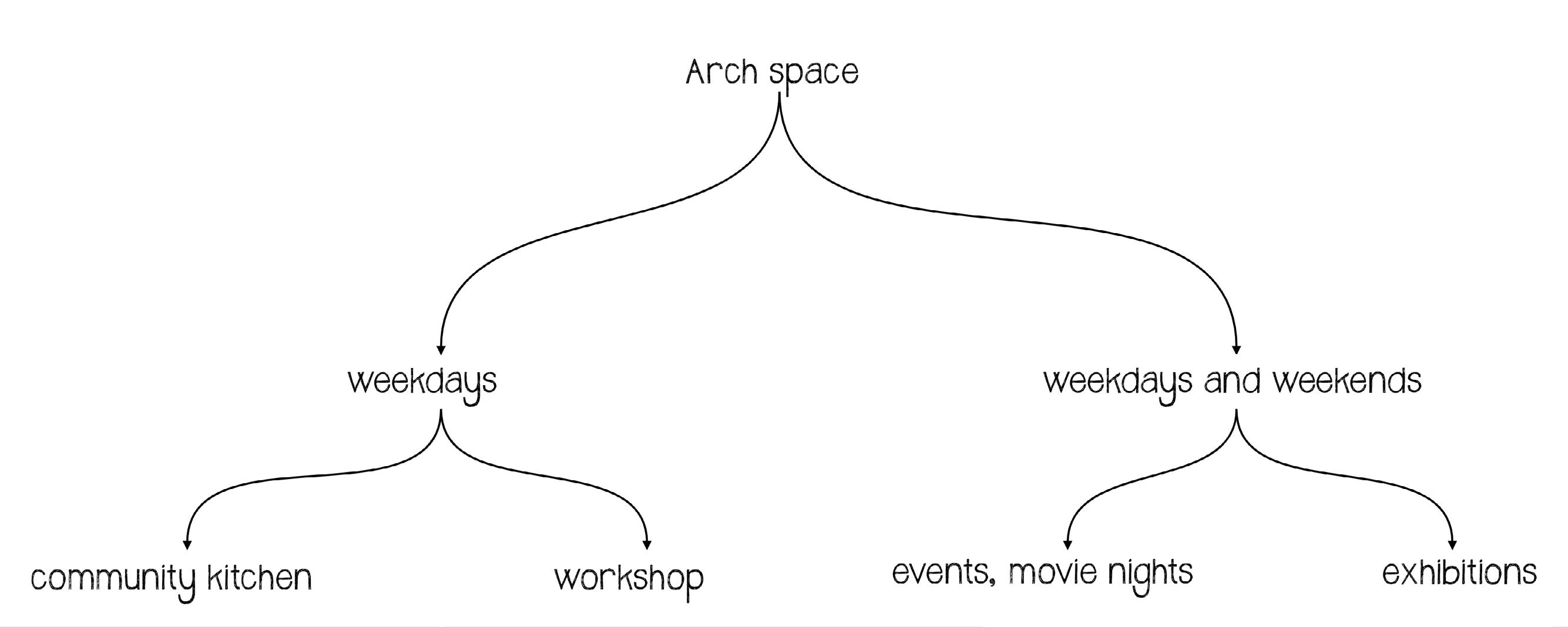

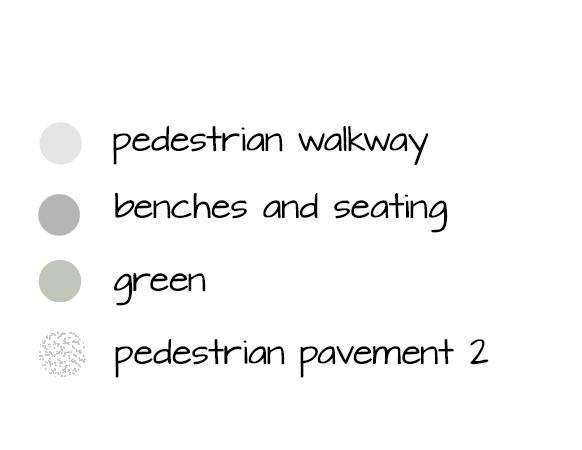

The design incorporates an integrated plaza that will be a place of recreation, social interaction, and relaxation whilst simultaneously roofing a self-managed community space for diverse spatial practices. The community spaces will host community engaging activities such as a Community Kitchen, and Workshop Areas which will help amplify the “sense of place”and the lost “community spirit”.

This project intervenes to help elevate the unnoticed essentials of urban life. It aims to bring new life to vacant railway arches that run through the historic streets of the Bankside neighbourhood and reclaiming it as a space for inclusive social and cultural interaction.

of belongingness” that is lost at present.

“Sometimes what feels ideal and welcoming for a specific group might be emotionally alientating for others..”

CHAPTER 02

“We need to acknowledge that places are no longer just spatially bounded, but instead defined by the interactions of different cultures and multiple identities within and beyond the static space.”

(Massey, 1993)

The changing nature of London’s population has led to a diversity of people and it is important that these places are public for all. Some public spaces in Bankside have the look and feel of a public accessible place but are governed by restrictions enforced by private landowners or private security companies. The public realm around the tate and its surrounding,

although being one of the most prominent public spaces with alluring landscaping and gen erous seating arrangements only “seems” accessible to the tourists and office goers in the area.Through analysis of the spatial properties of these places, it has been observed that they do not attract the residents and workers in the area who spend longer time.

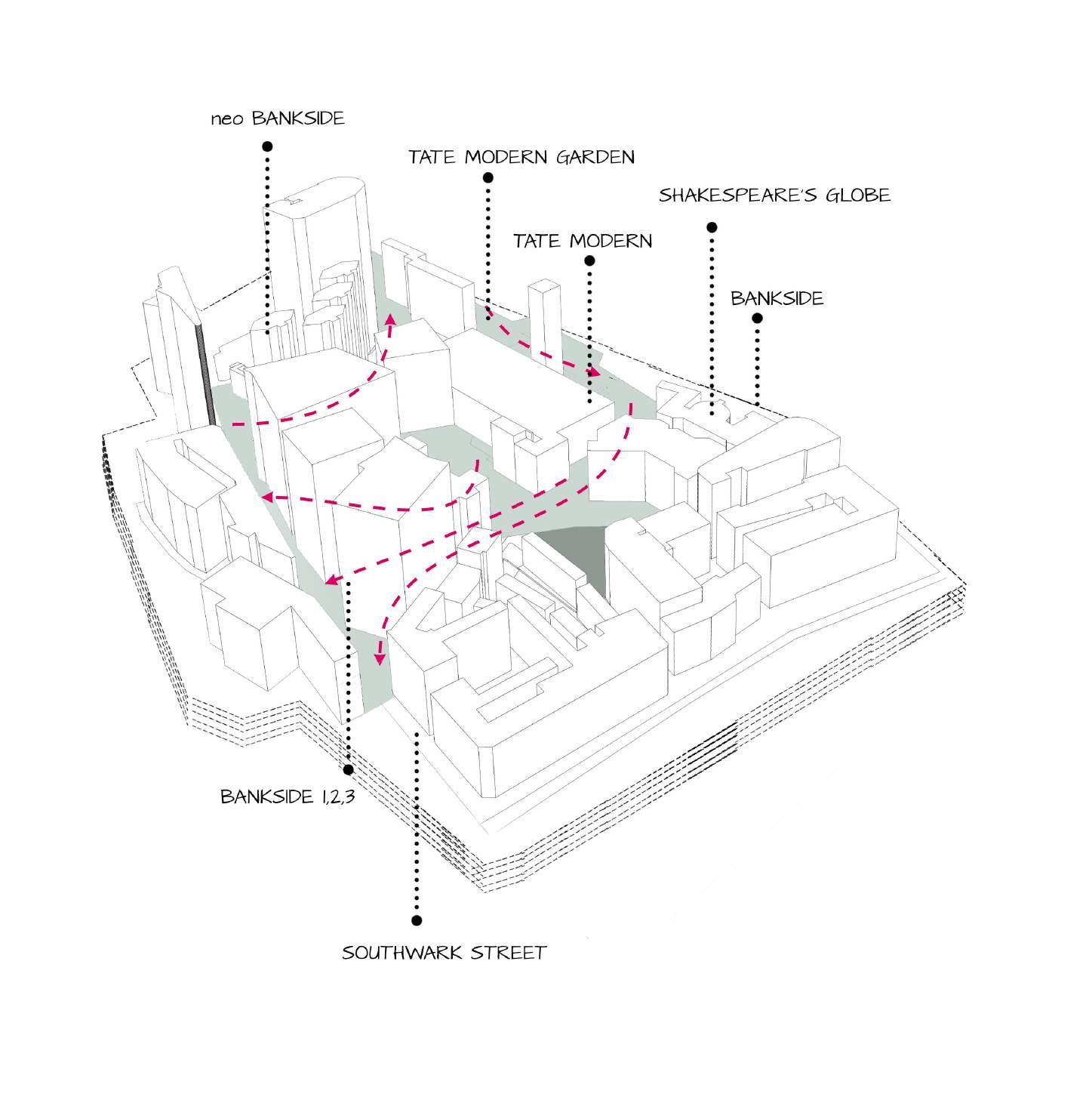

Anyone walking along the Southwark street can walk through the pathway between Bankside 1,2 and 3 buildings directly to the backyard of the Tate and its garden. Further along the southwark stretch from Bankside 1,2 & 3 blocks, there are no peripheral features around the Neo Bankside blocks either, which

also forms a direct connection to the backyard of the Tate. This gives the idea that people can move around through these spaces freely as there are no visible boundaries.

However, the exquisitely designed places are not truly public and are meant to attract only a certain range of user. These seemingly public spaces impose visible and invisible modes of control by restrictions in entry time,booking systems or through their spatial properties.

The public spaces in Bankside are designed to serve tourists and office goers in the area but there are hardly any activities that involve the other user groups in the community.

The materiality and surface differences in the spaces designed between the three high rise office blocks Bankside 1,2 & 3 is visually fascinating but due to the

absence of relaxed sitting arrangements,these spaces are only mostly occupied by the office workers during their lunch hours.

“People tend to sit most where there are places to sit”

(Whyte, 1980)

These seating arrangements are robust looking and meant for tourists who are there to visit the Tate or enjoy Bankside and its amenities. It doesn’t engage with the common user groups and doesn’t create a connection in terms user-spatial

experience. They evoke a kind of “temporality” which seems like it is not meant for people to spend longer times or feel relaxed.

The lush landscaping around the Neo Bankside blocks with the private gardens and statues offer a visual amenity for the public but there are no seating arrangements anywhere.

It provides a barrier free route directly from the southwark street to the Tate modern backyard but has accessibility restrictions controlled by time.

The public realm in front of the TATE with generous seating arrangements look very disconnected and is mostly occupied by visitors at the TATE.

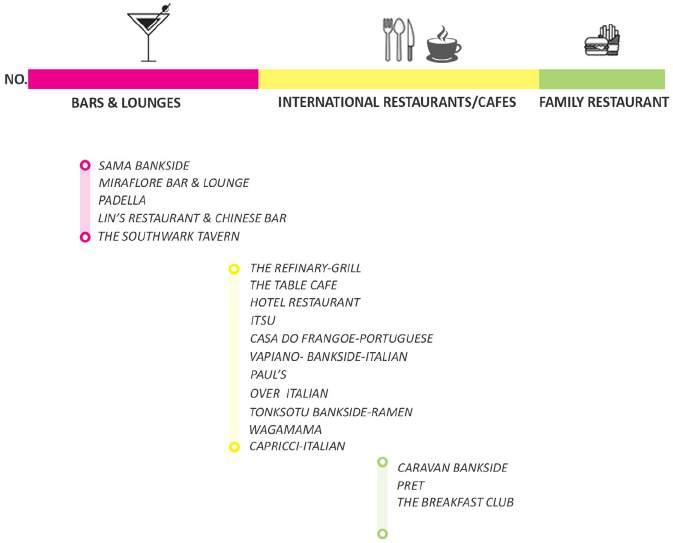

The Southwark Street is mostly inhabited by high end commercial buildings and there are only a few residential blocks which have been here for decades. Most of these high-rise commercial blocks along the east west stretch of Southwark are mixed use buildings and have restaurants, cafes, and bars, and international food chains. These makes it unaffordable for the residents in the community and socially excludes them as more ordinary shops

or family restaurants are not available along the streets.These restaurants are mostly visited by tourists only who are here to spend a generous amount of money on food and by office workers who work here. With the social boundaries and limited usage in the area they gradually lose the “sense of belongingness”.

“you know we are in desperate need of ordinary shops and cafes where people with children can walk into and also afford them. Most people here are not 30,000 a year...”

(southwark resident,2021)

“I wish there were more ‘don’t-book-in advance spaces” for us to just walk in..”

(southwark resident,2021)

There are no ordinary shops along the streets but only high end bars and cafes. Hence these are mostly visited by tourists and office goers during lunch.

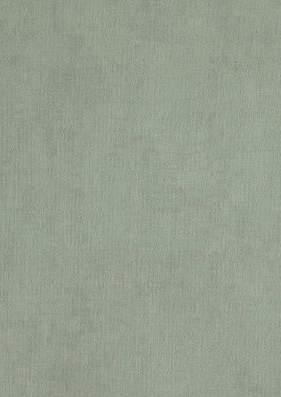

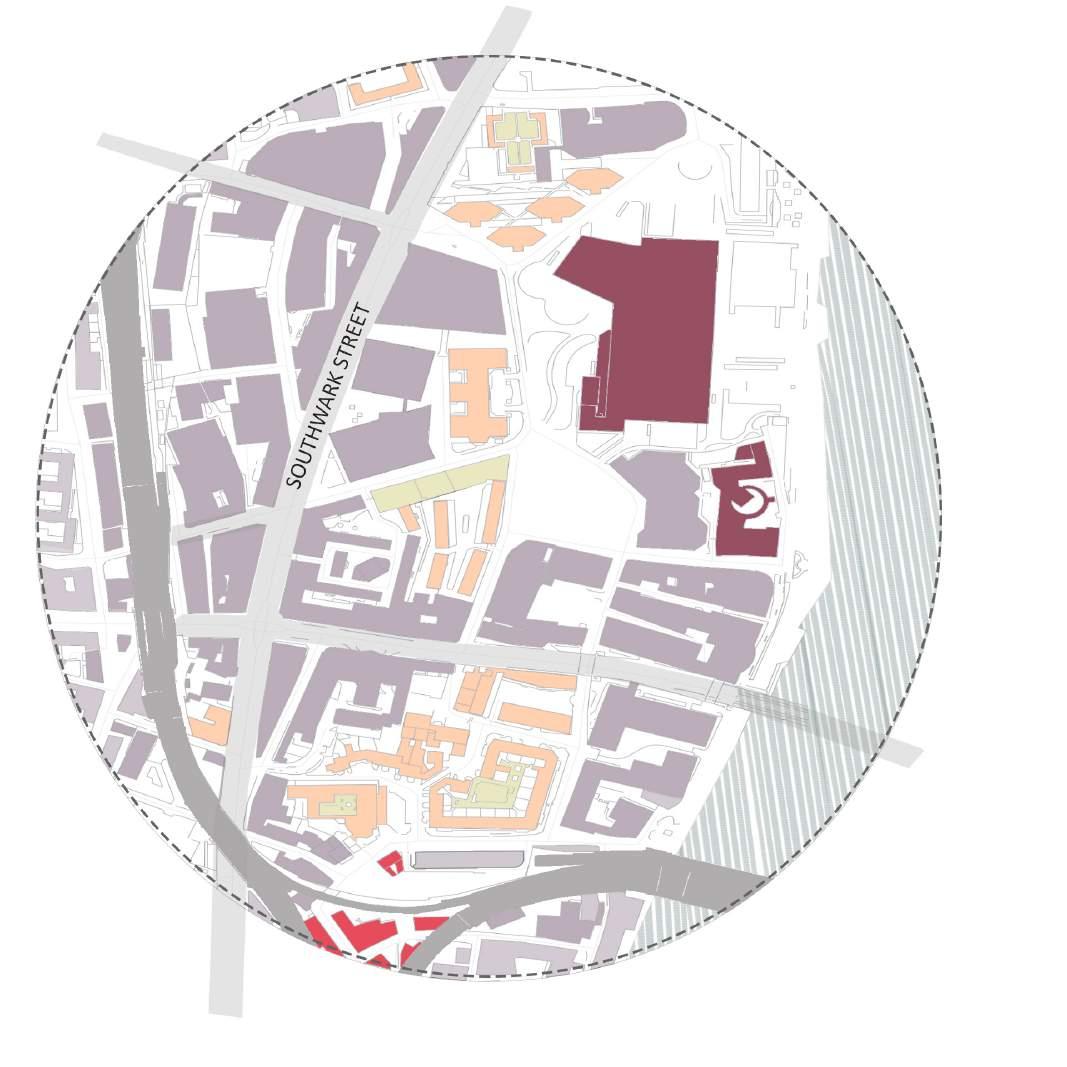

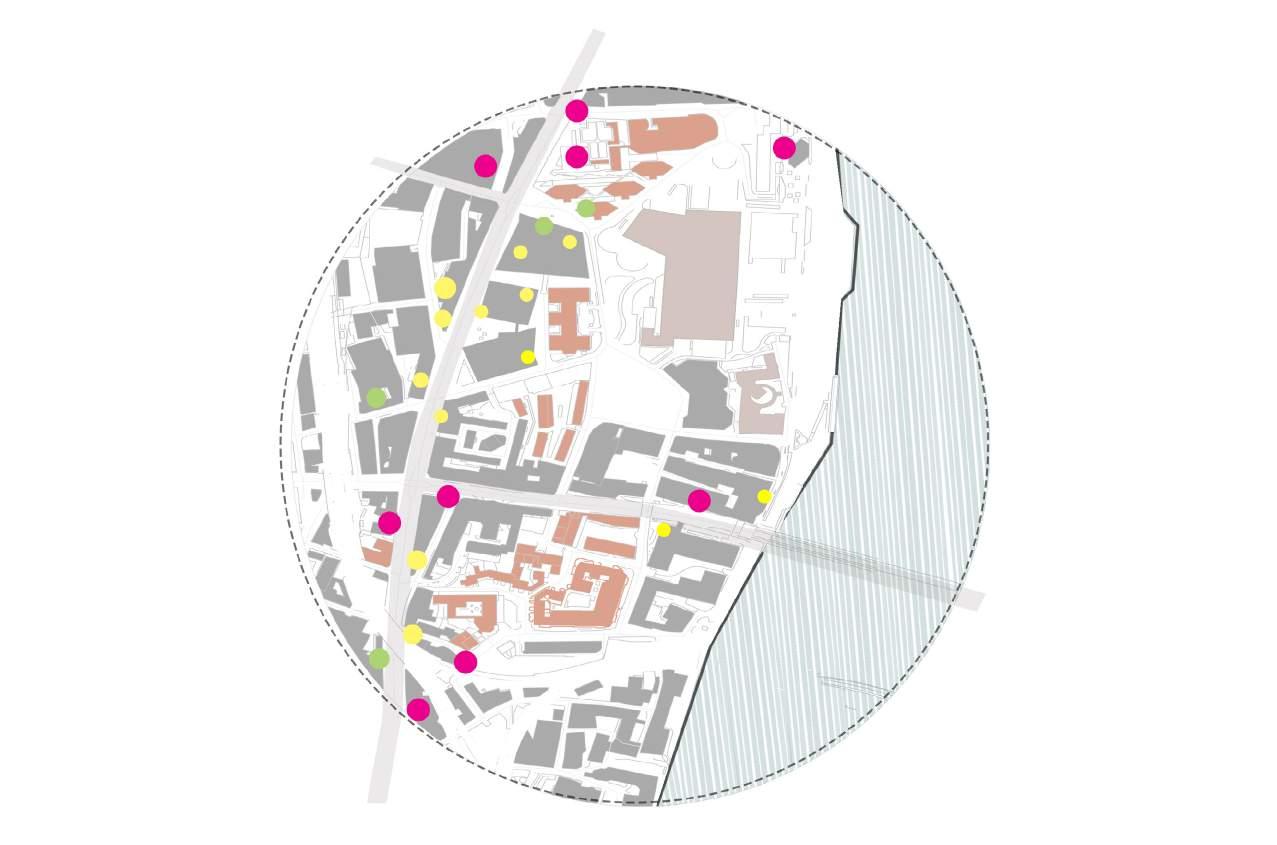

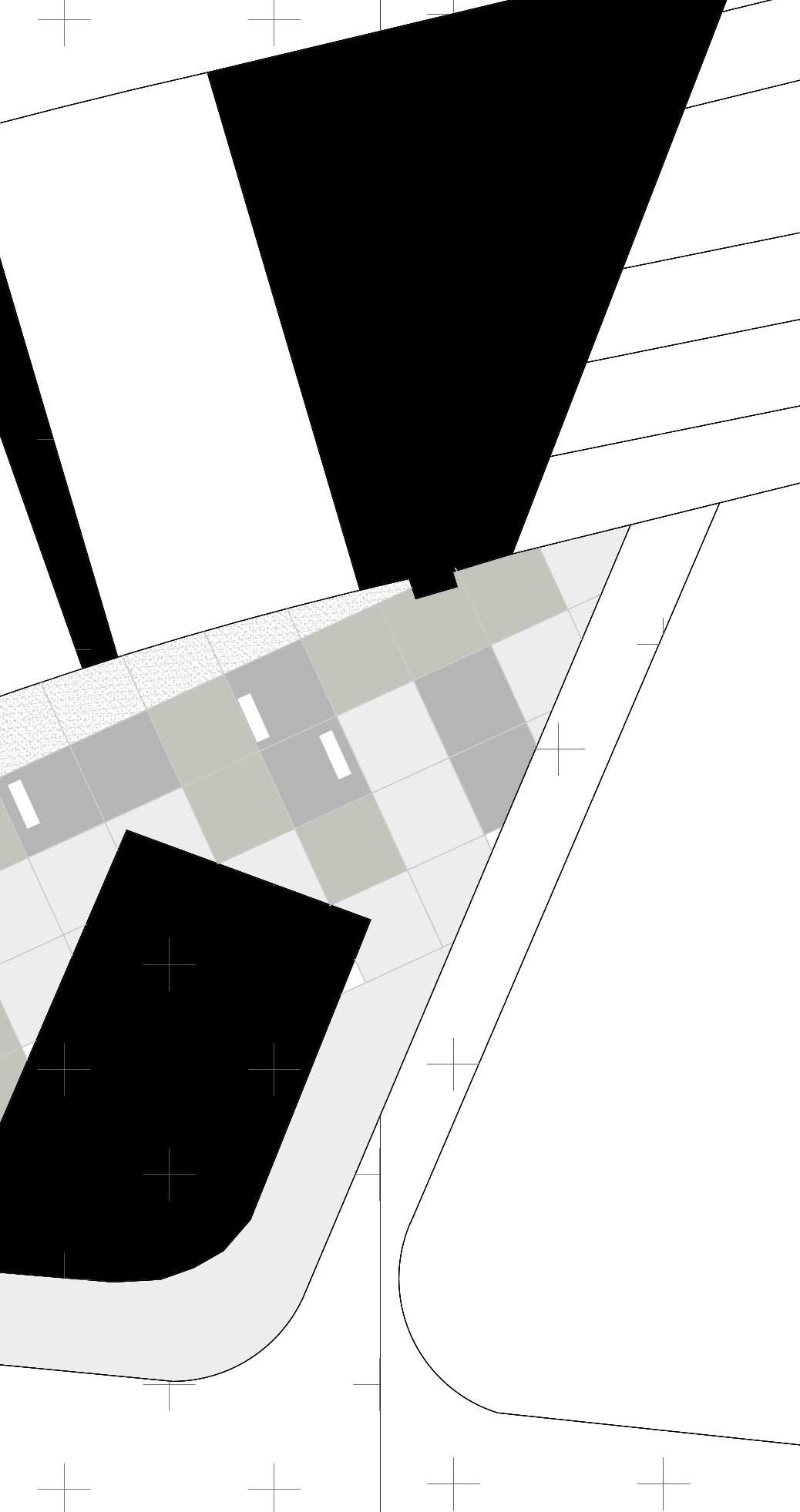

The land map analysis shows how the area of Southwark has been highly corporatized. Its dominantly inhabited by high rise mixed use blocks compared to the residential blocks.

This analysis confirms that although there is a residential community in Southwark area, the number of family restaurants are the lowesst while bars,lounges and international food chains are the highest in number.

The rapid corporatization has led to these high number of bars and “advance book-in” spaces which seem to catered towards serving he tourists or the office workers,or the residents at the luxury apartment blocks.

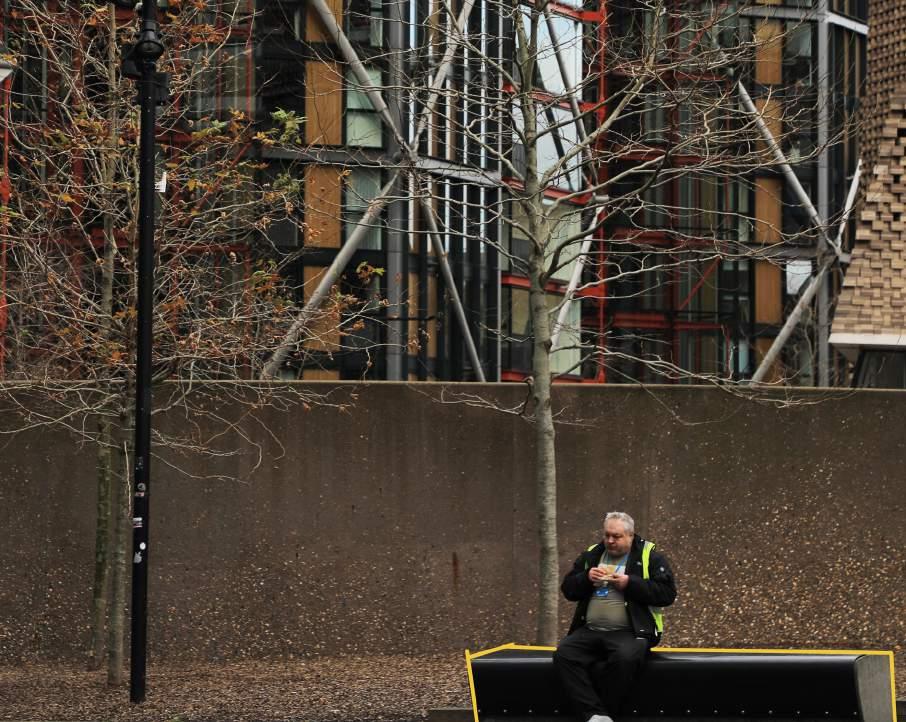

With the rise of land value around the area, there is a large number of constructions for luxury apartment and office building and a decent number of construction workers are always present here throughout the day. But looking

closely at the scenario, it can be observed that there is no place for them to relax and have food as these places give a feeling of robustness.

“Ideally, sitting should be physically comfortable—benches with backrests, wellcontoured chairs. It’s more important,however, that it be socially comfortable.”

(Whyte,1980)

It seems like they have been designed to serve a certain group of people but not catering to the needs of the people who are present for most parts of the day and failing to make them feel at ease.

The imposing Victorian viaduct that cuts a path through Bankside, London Bridge are an integral part of London’s industrial heritage. Around a third of these are currently derelict or underused but some are being used for a wide range of business across London.One such railway arch is the Flat Iron Square in London Bridge,an iconic railway arch space for food, drinks and events.

These functions are accommodated within the arch spaces and although known as a “public space” it is also privately owned and is governed by restrictions in time and booking systems which doesn’t make it completely accessible a square.

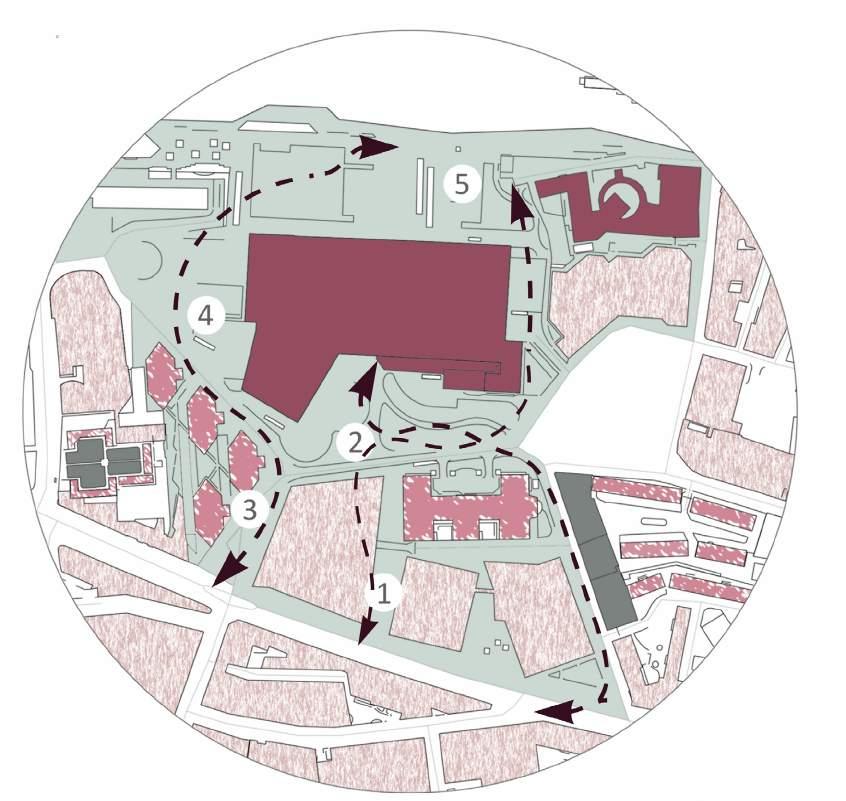

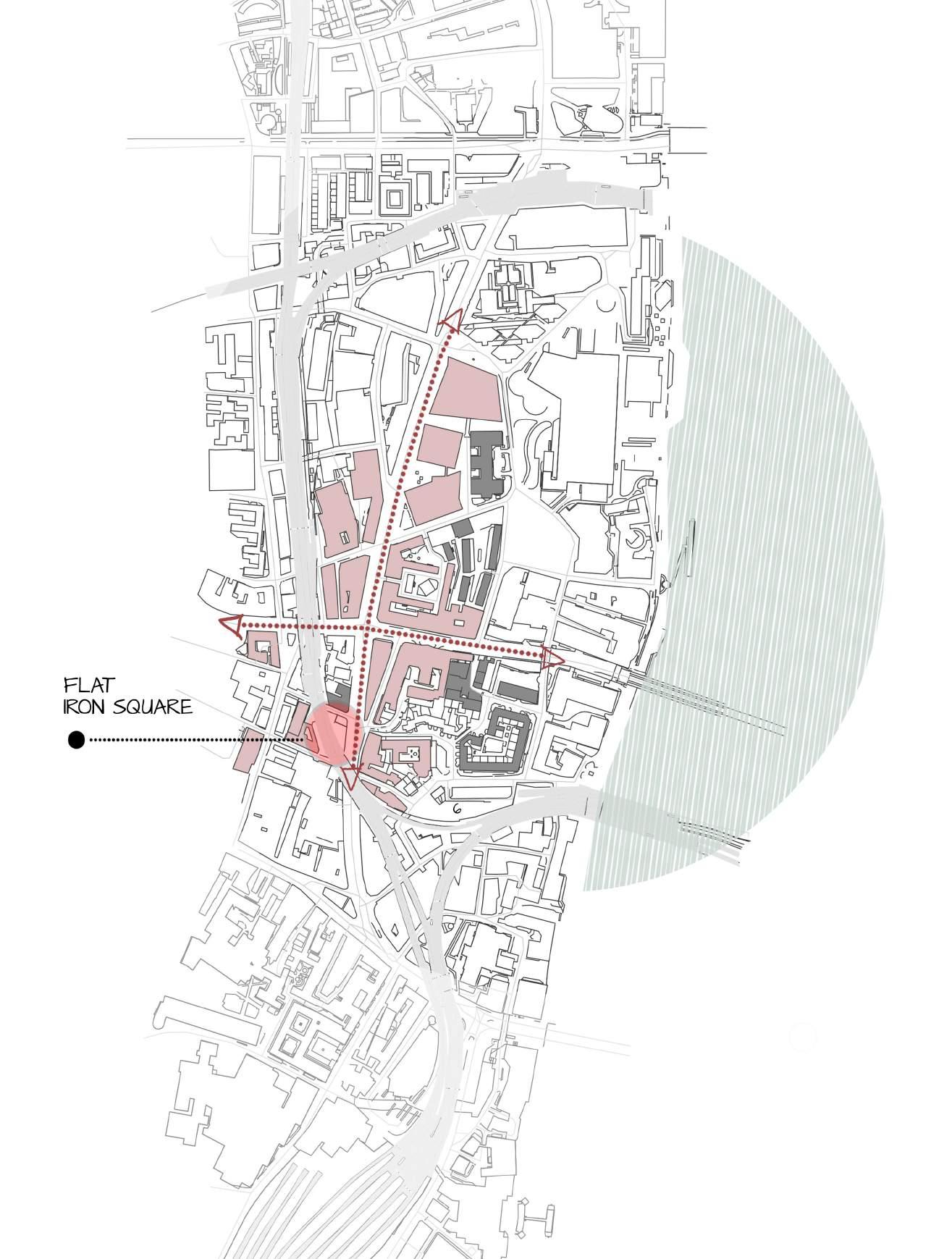

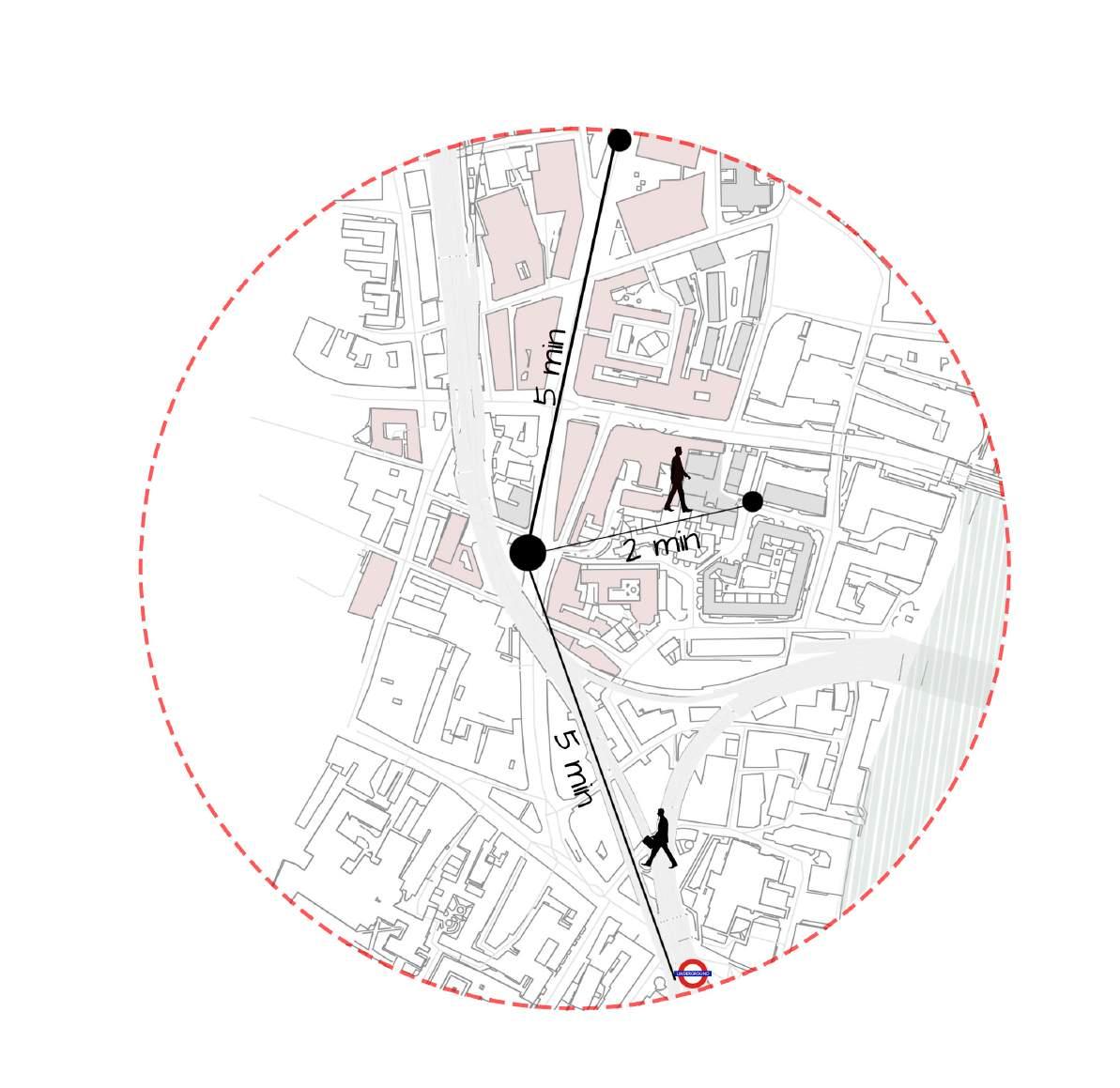

We began by understanding the site adjacencies, its physical and current situation.The Flat Iron Square is a five-minute walk from the London Bridge underground station, and a five minute walk to Southwark commercial zone.

It is located centrally in the commute road that office goers who work in the Southwark commercial street, travel across everyday. It is centrally located and also opposite the social housing blocks who at present, have no recreational avenues.

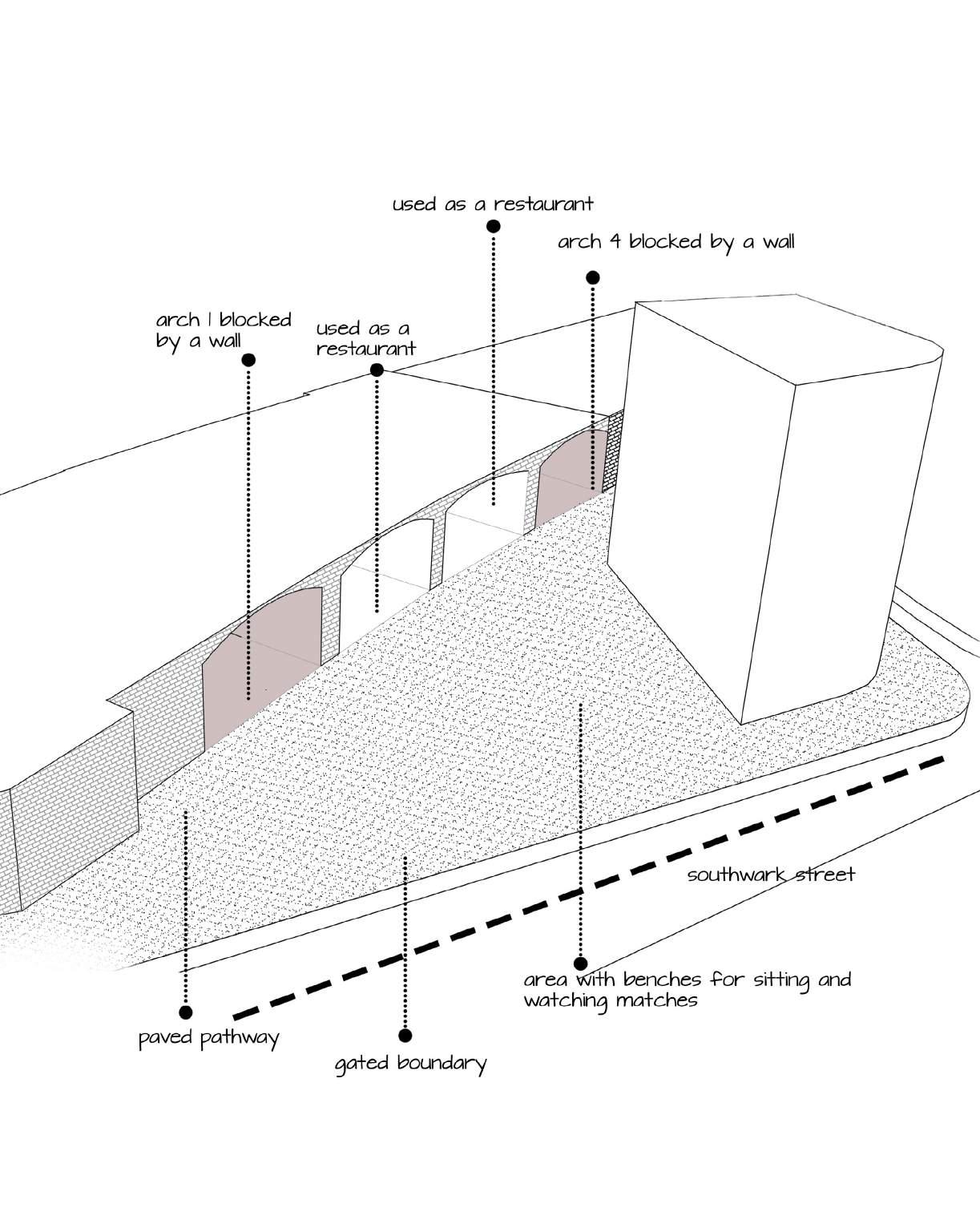

At present, only two arches are being used at the Flat Iron Square. The first and the fourth arch is blocked by a wall while the second and third are being used as a place for gaming, food and drinks.

The outdoor space is designed with seating arrangements and is shaded. It has tv screens hung along the tables where people gather during match season and food. The adjacent small food stalls were once in use but now have been closed down.

Alike the other public spaces that have been studied, the flat iron square is a privately owned property. The two arches that are being used for food and drinks are not making optimum use of the space.

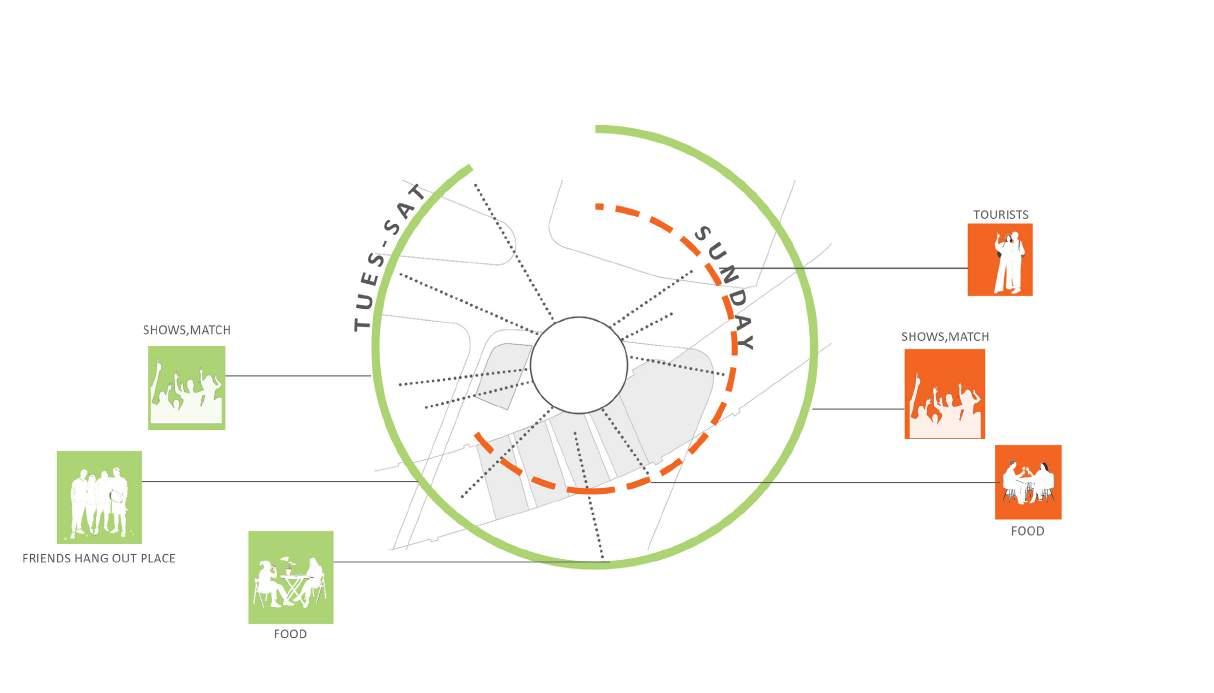

From our site analysis, we have identified a few problems with the square even though it seems to be a very successful public realms. This too is only catering to the needs of a certain range of users

It has restaurants that serve food and beer but its not a place where people with families can visit

It requires prior booking through website and appointment.

It is governed by restrictions in time. Its closed on Mondays, its open from 12pm to 11pm on TUESSAT. On sundays its open from 12pm-8pm.

Whyte details insights into seven basic factors of successful public spaces: suitable space, interaction with the street, the sun, food, water, trees, and, finally, a term Whyte calls triangulation, or the ability of a public space to bring people together”

(Whyte,1980)

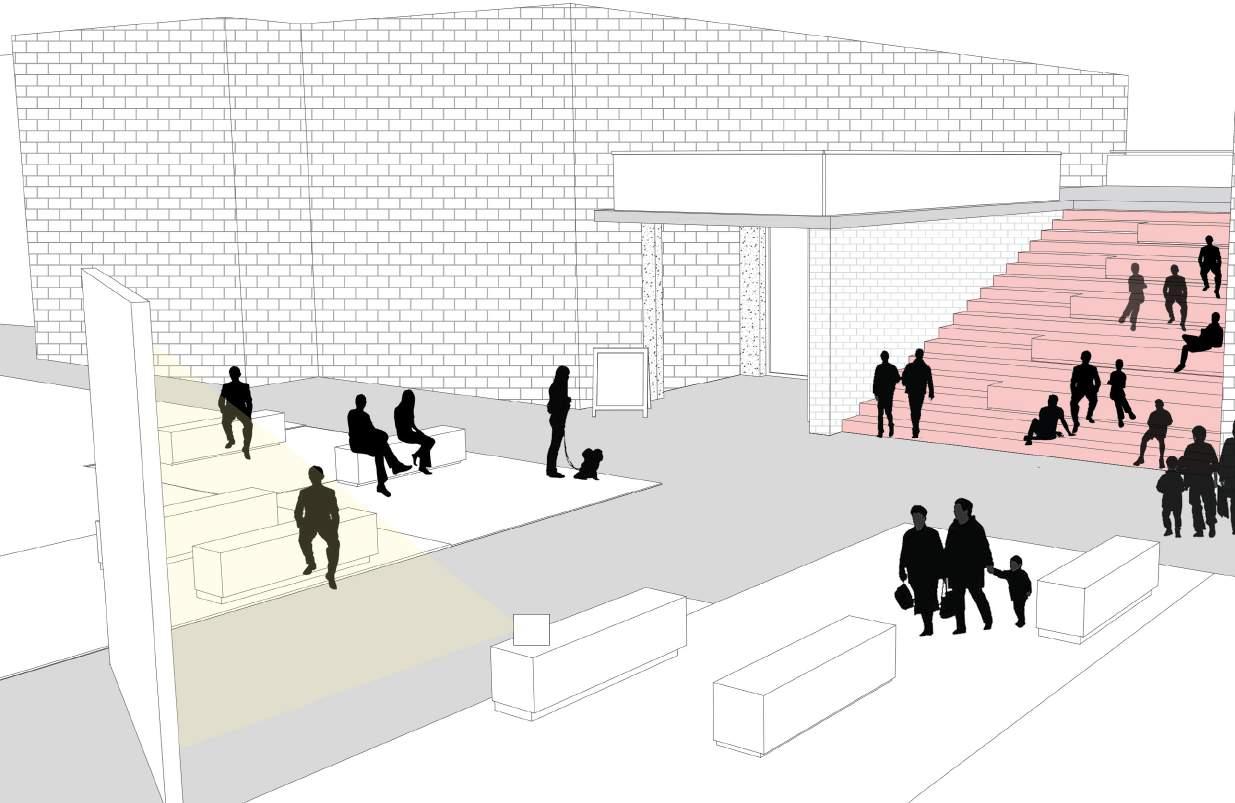

The aim of our design proposal is solely based on the idea that reinvigorating an iconic square that is at the heart of Bankside, will bring about an opportunity to bring diverse groups within the community together. It will not have just seeming features of a public place but also feel like one.

Our design involves a space that can be used for diverse spatial practices notably, community engagement activities. It will also be a space for interaction, sharing and collaboration so that the lost “sense of belongingness” in the people can be revived.

“The dining table is as much a site for a practice of ecological care, as for building social connections”

A space to bring diverse groups of the community together

To engage them in community activities

A self managed collecive space

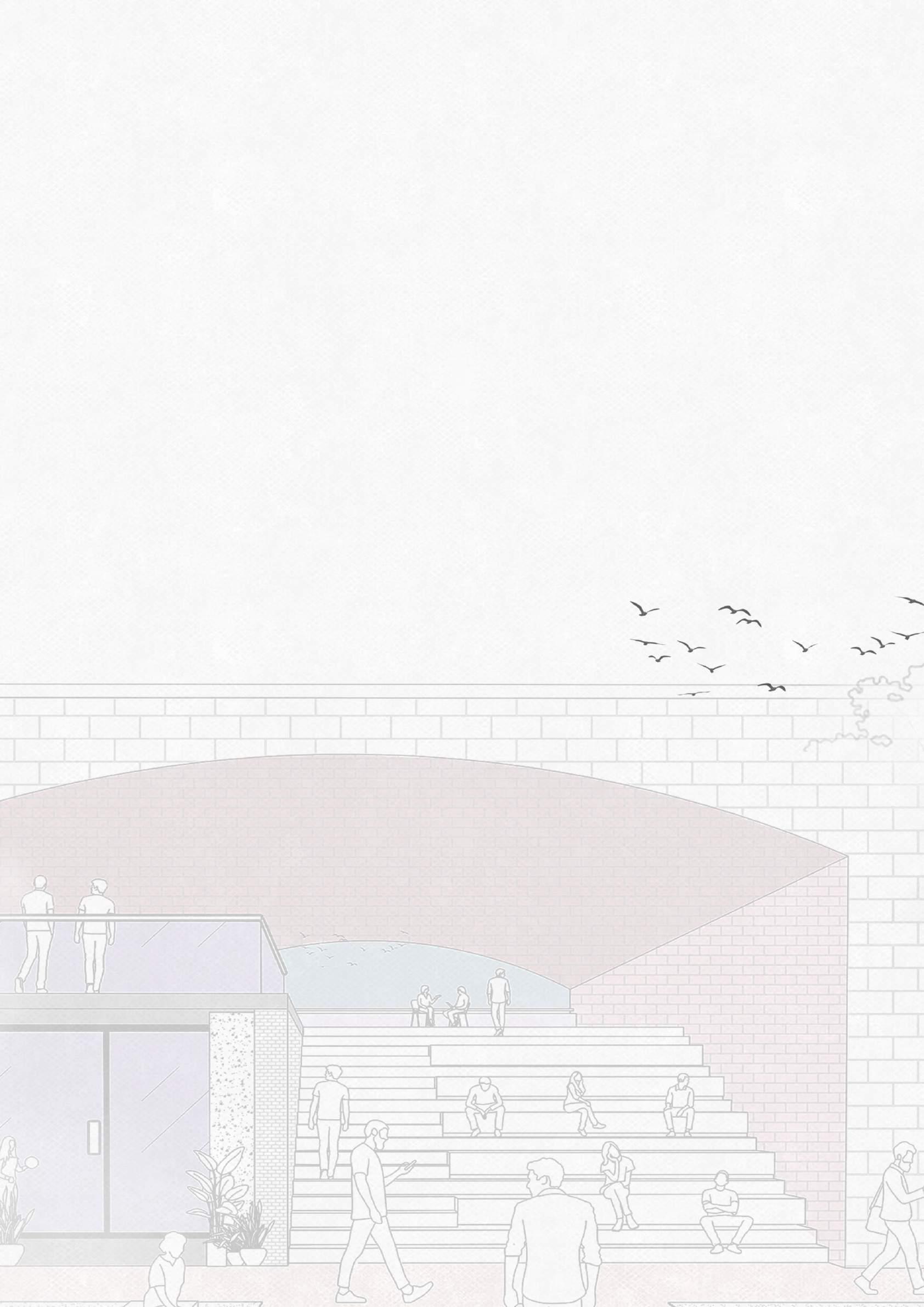

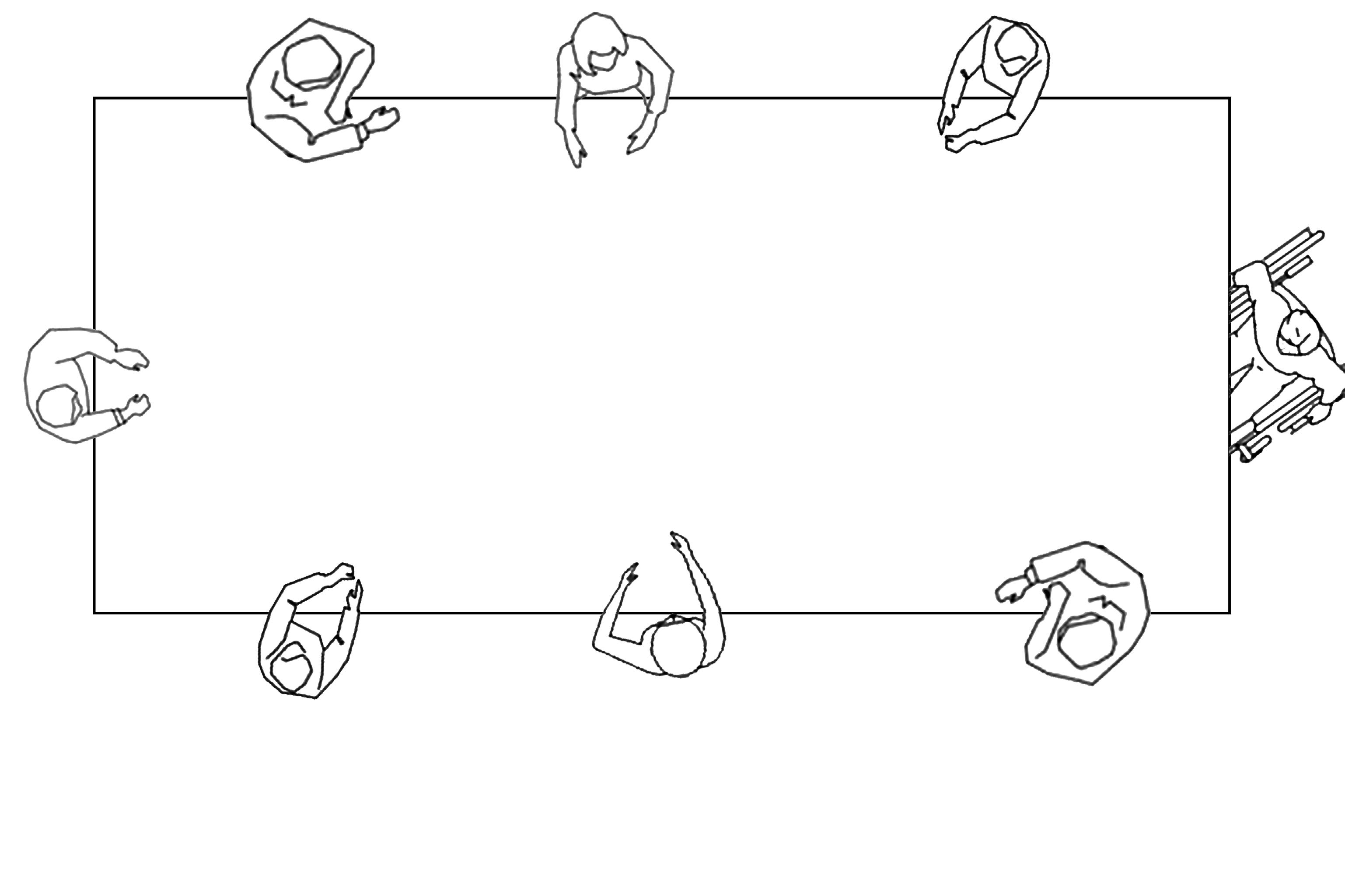

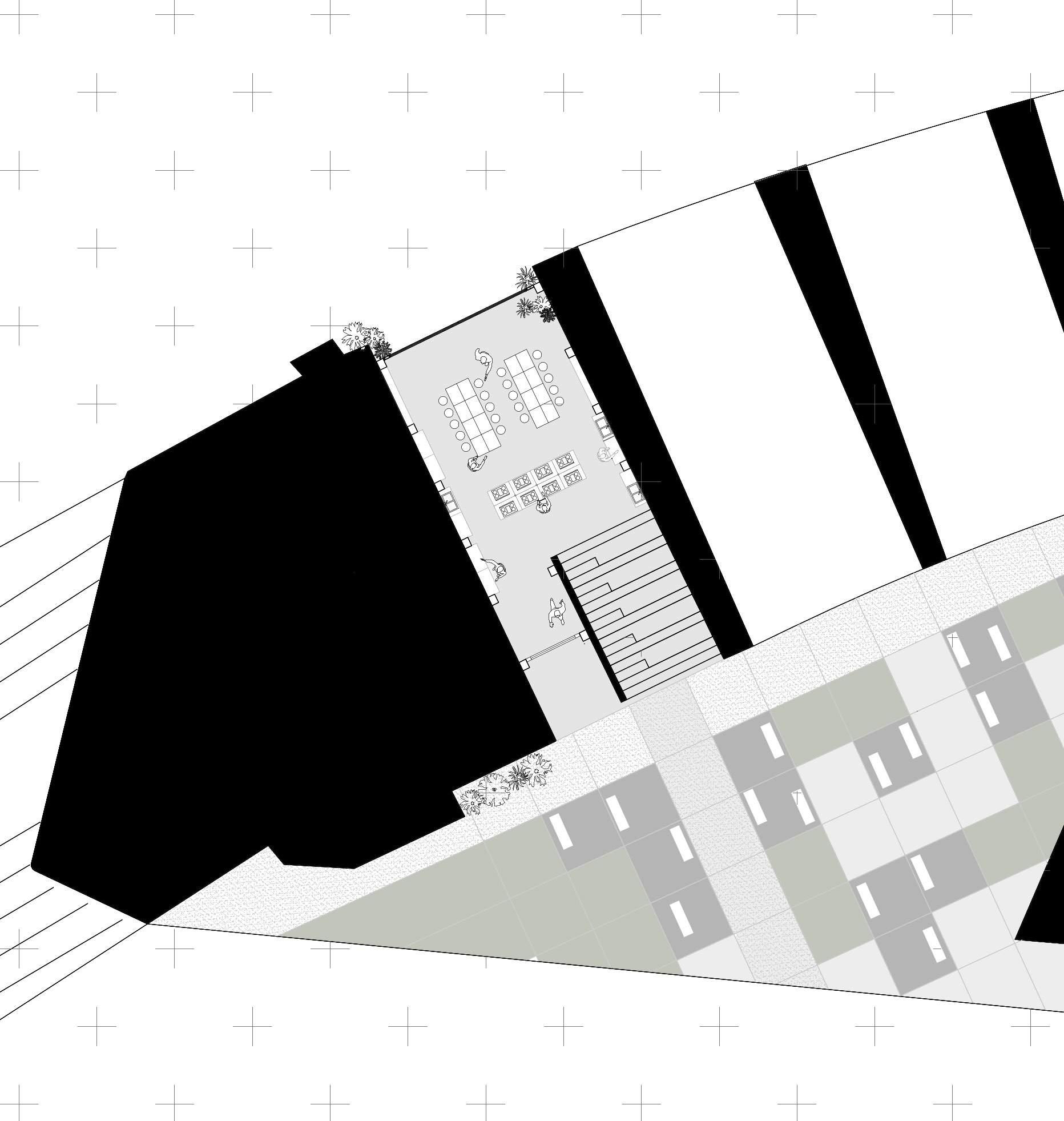

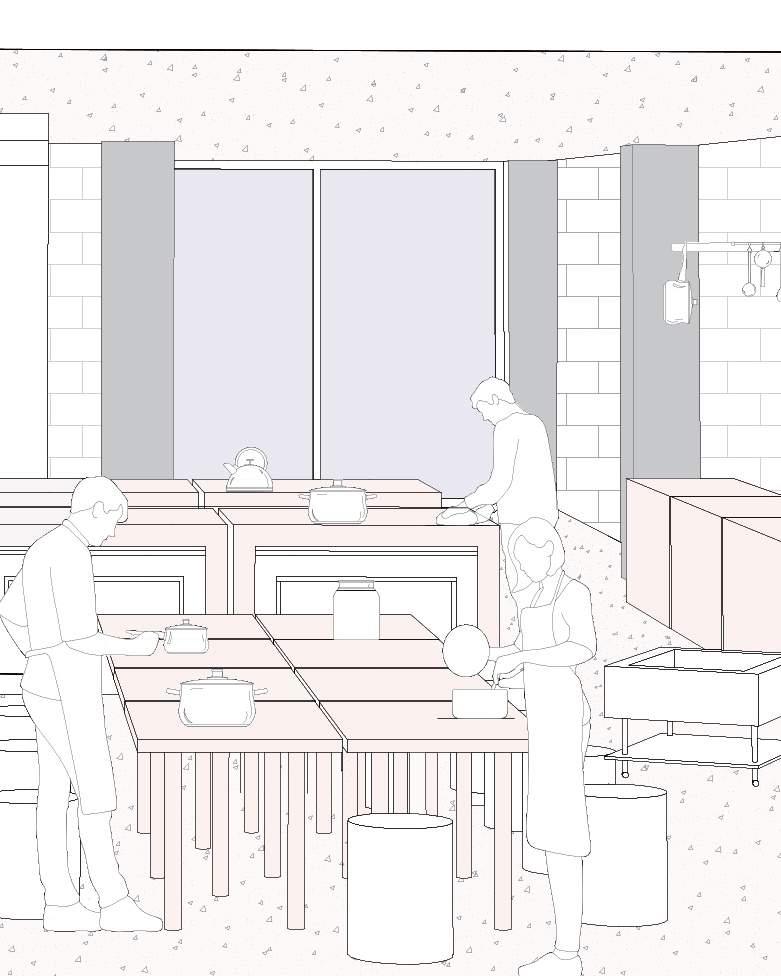

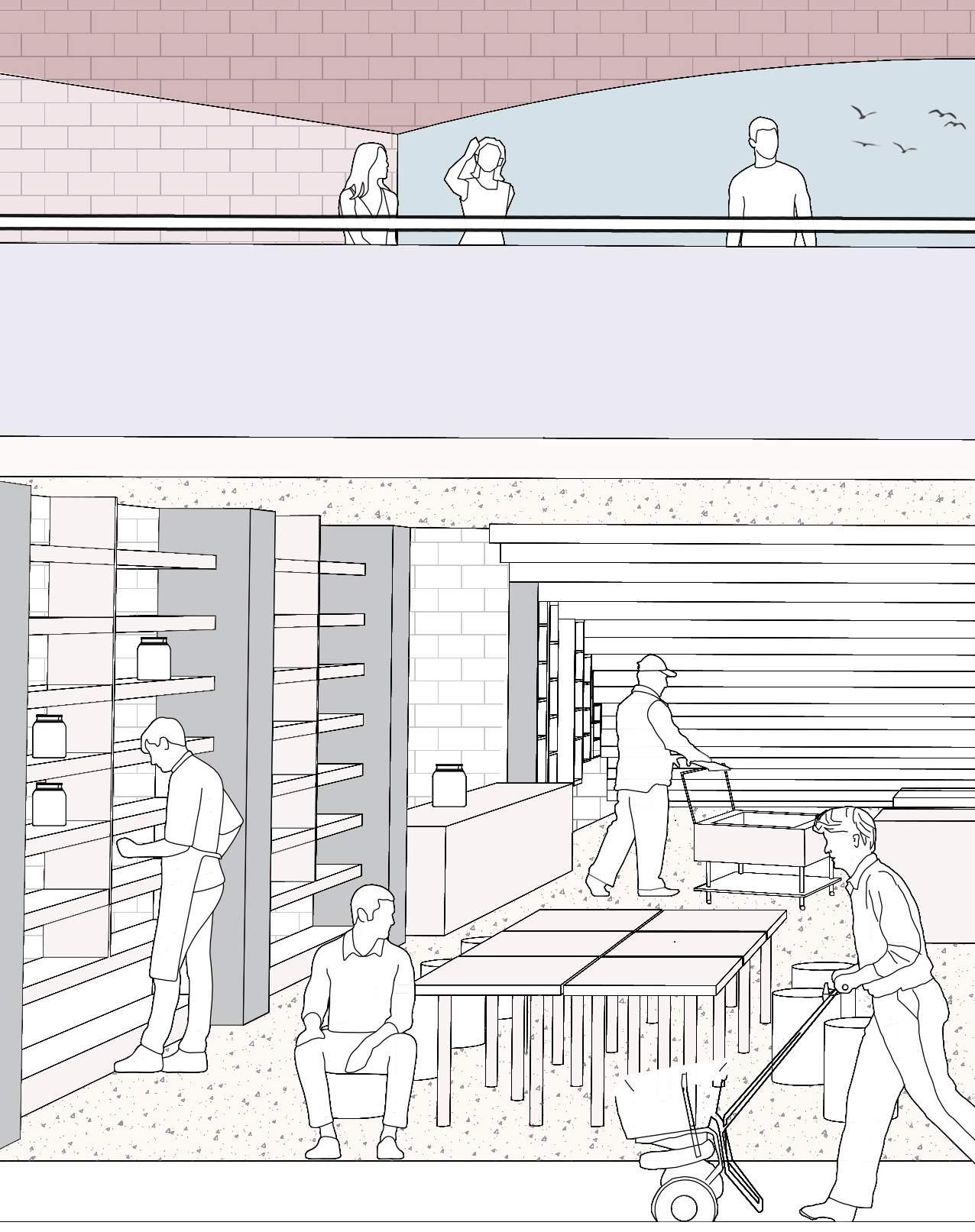

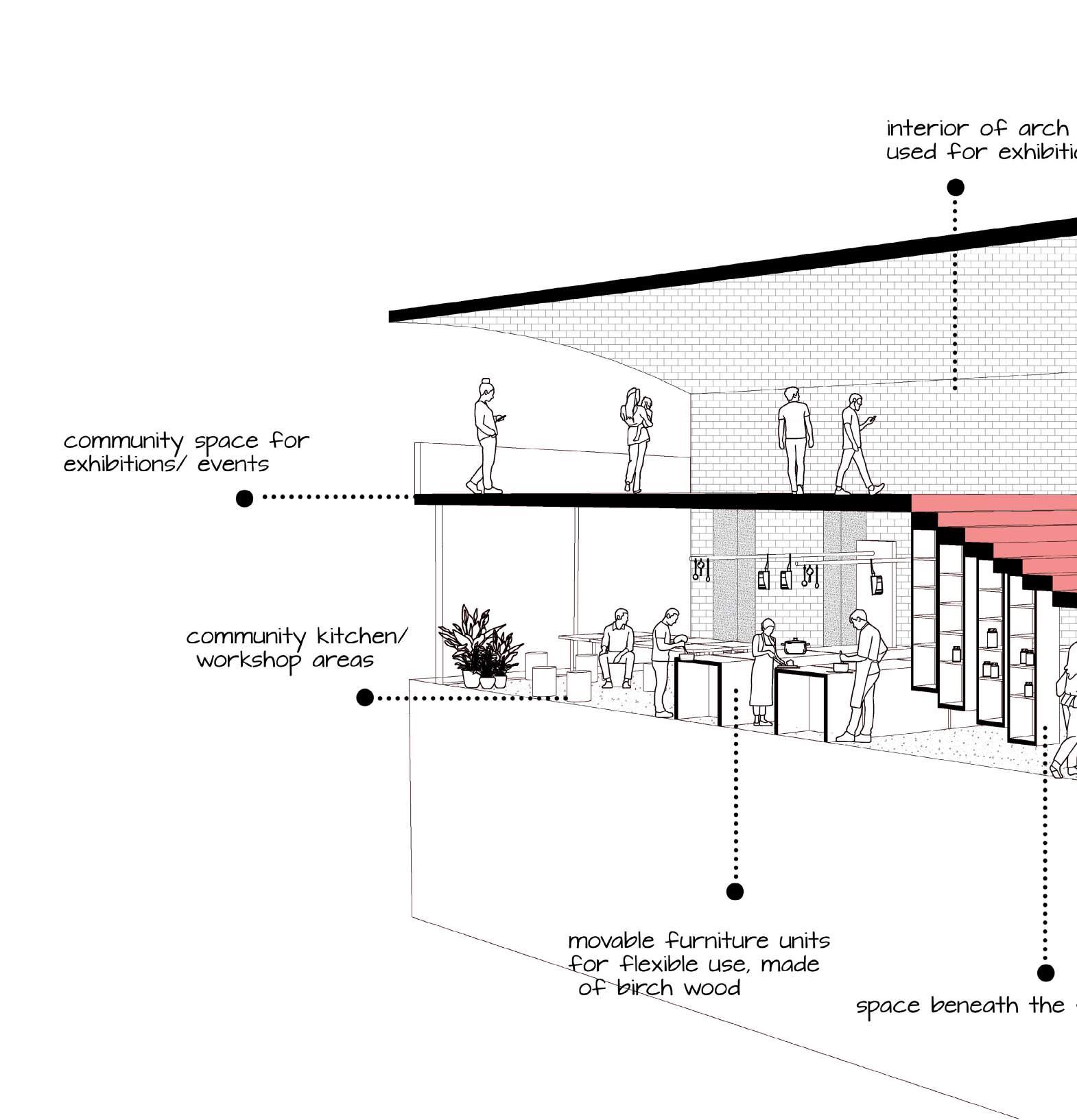

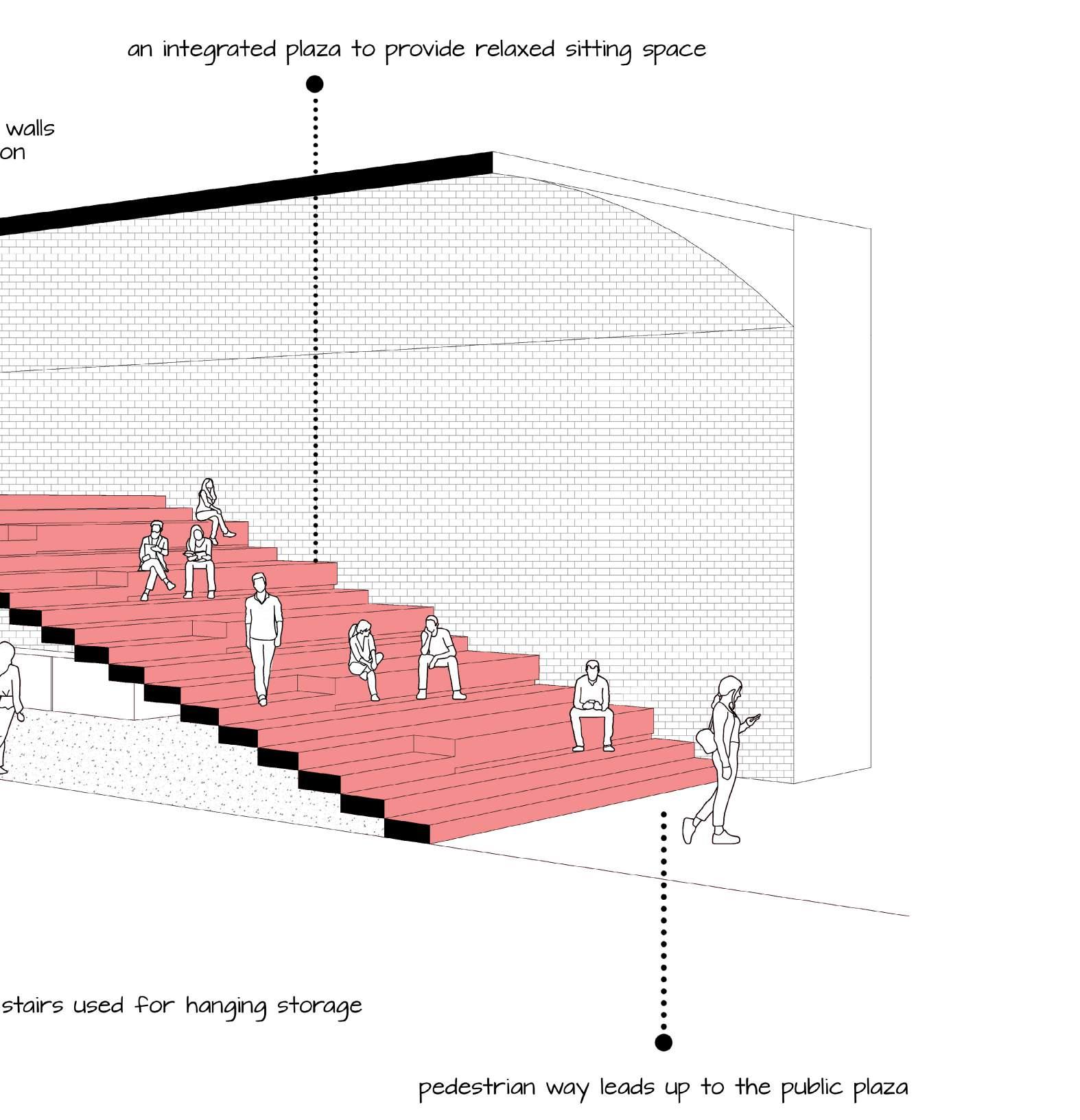

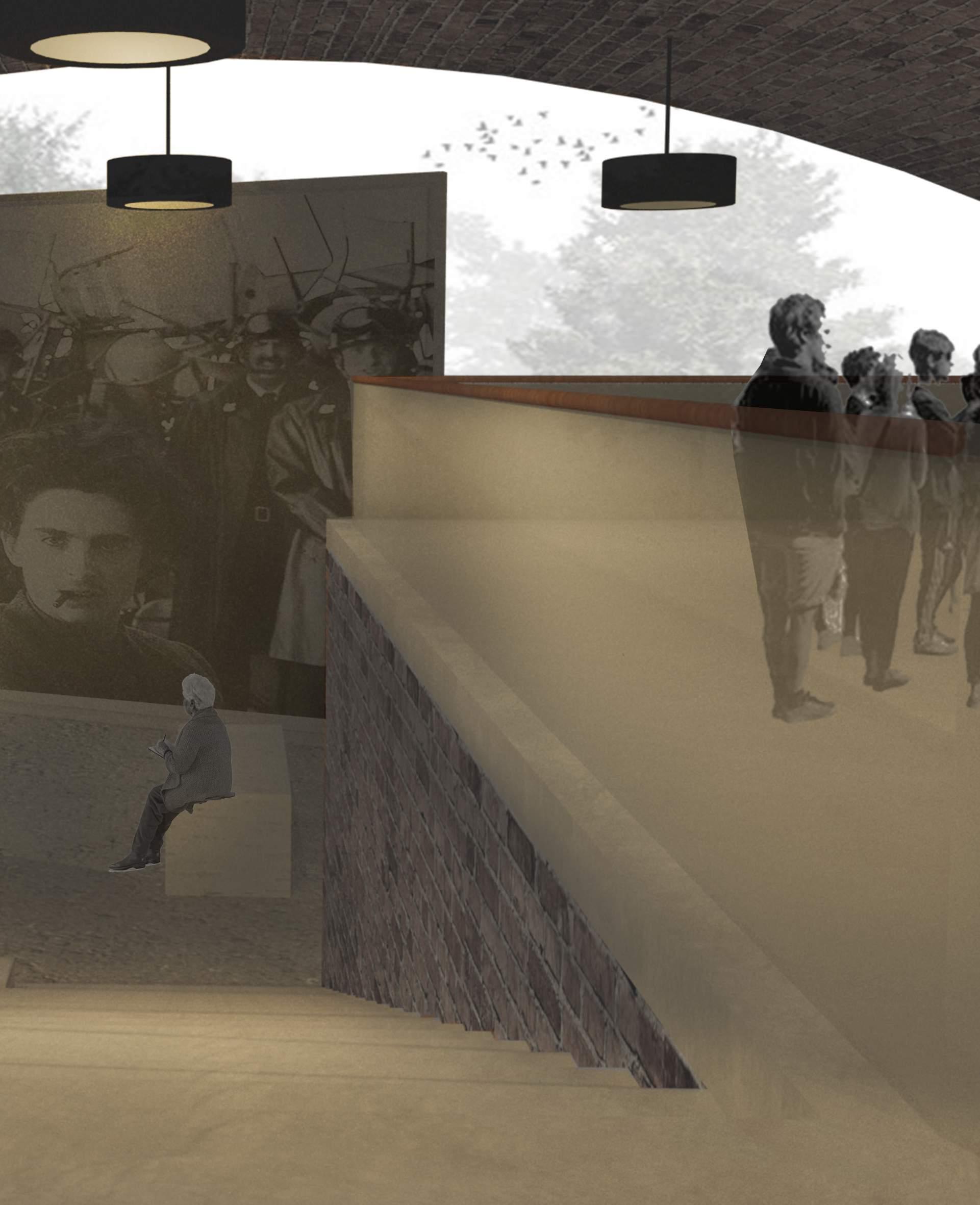

Making optimum use of the double height space of the arch, our design proposal integrates a relaxed sitting area for the public through a creatively designed indoor plaza. The plaza roofs a community space below it and leads to a public space

The community kitchen, workshop space will be open for the public on WEEKDAYS. The public space above, the indoor plaza will be open throughout the WEEKDAYS and WEEKENDS.

(Zegarra,2021)

The design proposal incroporates a space that can be widely used for public and private benefits.The community kitchen will be a self managed collective space that will be controlled by the residents of the community. The indoor plaza will be designed to be a hotspot for social and cultural interaction and integrates itself to the plaza outside.

The plaza space outside the arch will be a continuation of the interior space. It will be occupied with more temporary seating arrangements. and open for flexible use,or simply as a relationship space. People can use the indoor plaza as a backdrop for events like fairs, markets, movie and show nights.

REINVIGORATING THE SQUARE

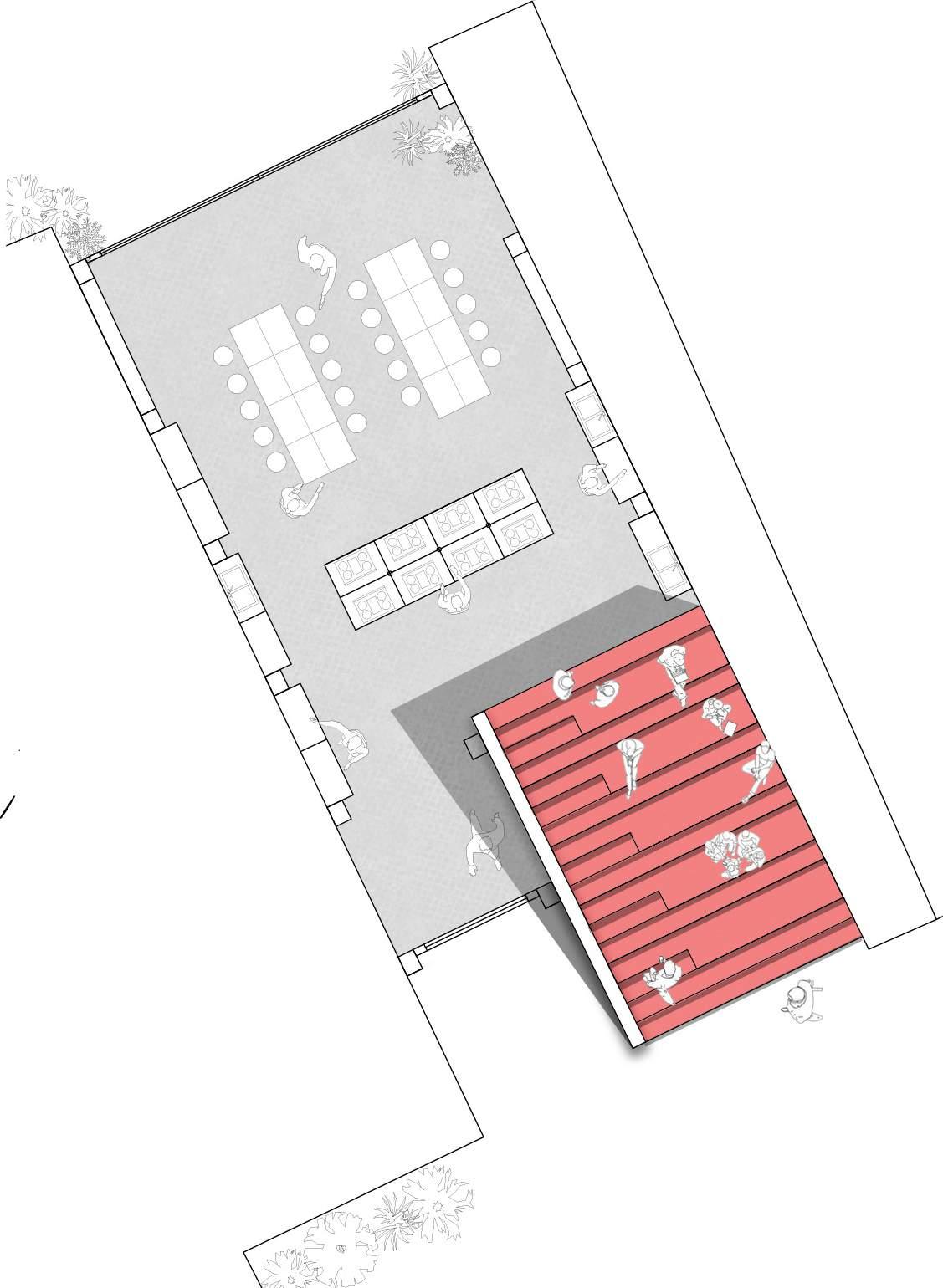

Ground floor plan as WORKSHOP AREA

First floor plan for event/ exhibition space

The open stairs lead to the upper level which is open for events and exhibitions held by the community and overlooks the plaza outside. Temporary moveable furnitures are designed inspired by the birchwood trees in Bankside which can be used for multiples uses.

The original walls of the arches are retained in its original condition and will be used to display exhibitons. The characteristic masonry here forms the central atmospheric element.This will bring the visitor into contact with the historic element of the railway arch. The stairs of the plaza are illuminated whilst still maintaining the dark nature of the victorian arches which elevates the materiality even more.

Detailed Sectional perspective of the designed arch in Flat Iron Square

Whyte calls triangulation, or the ability of a public space to bring people together. Triangulation – Things, actions, or activities that act as magnets to bring people together e.g. art installations, buskers, skating rinks, dance floors; performers provide a connection between strangers and acquaintances; art has “a kind of Venturi affect”, stimulating pedestrian flow and attracting people.

(Whyte,1980)

One of the most important elements of our design proposal was the indoor plaza, that forms a backdrop for all the activities happening in the plaza outdoor. It simulataneously roofs the community spaces below and leads to the an open public space above.

The indoor plaza can be used for multiple uses and it flows very naturally into the plaza outside, invigorating the public realm of the Flat Iron Square.

This infrastructure leftover converted to a plaza space will help reclaim the lost “ sense of place ” addressing the disuse groups in the community

Indoor plaza used as a relaxed seating space for the public where construction workers, office workers and others can relax during lunch and anytime of the day

Indoor plaza used as a backdrop for events or activities going on in the outdoor plaza like watching movies,shows etc. will attract people into the square

Indoor plaza wall becomes part of the exhibition that takes place on the first level. The characteristic masonry and its darkness has been retained to form a distinct exhibition wall

BOOK

Whyte, W. The social life of small urban spaces.

Sue McGlynn, Ian Bentley, Graham Smith. (1985). Responsive environments: a manual for design

• ARTICLE

Silva,L (2016). URBAN COLLECTIVES A NEW PERCEPTION ON SPACE

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311777746_

Tolue, S (2016). Design of a spatial database to analyze the forms and responsiveness of an urban environment using an ontological approach

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01527605

Bankside, Borough and London Bridge Characterisation Study, 2013

https://www.southwark.gov.uk/regeneration/borough-bankside-and-bermondsey?chapter=5

Inclusive by Design: Laying a Foundation for Diversity in Public Space, 2019

https://www.pps.org/article/inclusive-by-design-laying-a-foundation-for-diversity-in-public-space

Understanding ‘Inclusiveness’ in Public Space, august 2019

https://sustain.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/2019-50_Understanding%20Inclusiveness%20in%20 Public%20Space_Zhou.pdf

WEBSITE

School of Architecture & Community Development | University of Detroit Mercy. (2022). Retrieved

28 August 2022, from

https://www.udmercy.edu/academics/catalog/undergraduate2022-2023/ colleges/arch/

Shoreditch Community Kitchen - Thomas Damerham. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https:// cargocollective.com/thomasdamerham/Shoreditch-Community-Kitchen

John Pawson - The Design Museum. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from http://www.johnpawson. com/works/the-design-museum

Plaza Life Revisited - SWA Group. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.swagroup. com/idea/plaza-life-revisited/

It, N. (2022). Now You See It - Film. Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://monocle.com/film/design/now-you-see-it/

Zegarra, G., Zarzycki, L., Puijganer, A., Steel, C., Astbury, J., & Pascual, D. et al. (2022). Kitchen aid: care through collective cookery - Architectural Review. Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https:// www.architectural-review.com/essays/kitchen-aid-care-through-collective-cookery

Community Kitchens: The Challenge of Generating Roots in Displaced Communities. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.archdaily.com/966201/community-kitchens-the-challenge-of-generating-roots-in-displaced-communities

On the Grid : Leftys. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://onthegrid.city/cape-town/ east-city-precinct/leftys

Zoran Perin, h. (2022). CHROFI, architectural practice based in Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 28 August 2022, from http://www.chrofi.com/project/tkts-times-square

Search | ArchDaily. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.archdaily.com/search/ all?q=london%20railway%20arches&ad_source=jv-header

Revealed: the insidious creep of pseudo-public space in London. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/jul/24/revealed-pseudo-public-space-pops-london-investigation-map

Refurbishment Viaduct Arches / EM2N. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.archdaily.com/629237/refurbishment-viaduct-arches-em2n?ad_source=search&ad_medium=projects_tab

Adaptive re-use of empty and derelict arches ← News ← The Low Line. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.lowline.london/news/breathing-new-life-underused-and-derelict-rail-arches/

World, Z. (2022). Have You Discovered Bankside in London? The Latest Design District?. Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.zayahworld.com/have-you-discovered-bankside-in-london/ (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.dezeen.com/2020/12/04/ottolenghi-test-kitchen-design-studiomama/

Waterloo City Farm. Education and farm facilities Waterloo London. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://www.feildenfowles.co.uk/waterloo-city-farm/

The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. (2022). Retrieved 28 August 2022, from https://courses.planetizen.com/course/social-life-urban-spaces