NEOLIBERAL CONDITION of the the Seaport District

introduction to urban design sara jensen carr, phd

final project: zine

by ani dobbins

1. the ideology

“WHAT IS AN UP-AND-COMING NEIGHBORHOOD AND

2. before the seaport

3. the seaport district

4. the seaport has a scale issue

5. the architecture

WHERE IS IT COMING

6. the public realm

7. the branding

FROM?”

8. the future

THE NEOLIBERAL IDEOLOGY EXPLAINED

The neoliberal ideology is a nebulous one, one that is ill defined by nature, but works off of a set of core principles.

The first is to deregulate, so that private capital can take over from the state.

Secondly, weaken collective power wherever possible. This takes form in union busting, isolating individuals from the state, and by distancing landlords from tenants through management companies, and by distancing employers from employees, thereby eliminating the visible connection to power.

The next step is to decrease taxes on the wealthy, investments, trade agreements, and any other way the global movement of capital is hindered, while also limiting the movement of labor.

Next comes defunding public services, thereby further weakening public goods and public power, making the individual more dependent on private services. Simultaneously, they encourage public spending in private development, in the form of tax subsidies, infrastructure, low interest loans, and government easements.

THE ONLY ROLE THE STATE MAY PLAY IS THAT OF BODYGUARD FOR CAPITAL, WHERE THE BENEFITS OF PROFITS ARE HELD PRIVATELY, BUT THE TASK OF SECURITY AND LAW IS BURDENED BY THE STATE.

BEFORE THE SEAPORT

FROM PORT TO DISTRICT

The Seaport, as a neighborhood, is unique in many ways. It doesn’t have the history as a residential neighborhood, as the land doesn’t have much history at all beyond 200 years, as much of the site is reclaimed land. This isn’t unusual at all for Boston; most of the city sits on old marsh or other formerly brackish conditions. In a city with a housing crisis, though, it is strange that the Seaport seems to have no residential history. This is because the history of the Seaport is largely industrial. Railways connected the interior of the state and country to the ports that would unload goods from all over the world. There are still port functions taking place and now cruises have been added to the micro economy, but much like the rest of this country, the economy has shifted away from industry and manufacturing or blue collar labor, and has left a hollow shell of itself behind. For a while, the seaport was just a collection of parking lots, under-used railyards, and warehouses. It still is that mostly, but recently there’s been an uptick in interest from developers and a select few corporations, namely General Electric, Amazon. com, PrincewaterhouseCoopers, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Fidelity Investments, and a slew of reality enterprises and trendy restaurants to follow suit. And so the planning began, restructuring the Seaport into a yuppie paradise with high end housing, ample nightlife, and stunning views of the city and harbor.

What they forgot to plan for was the human experience.

district

THE SEAPORT DISTRICT

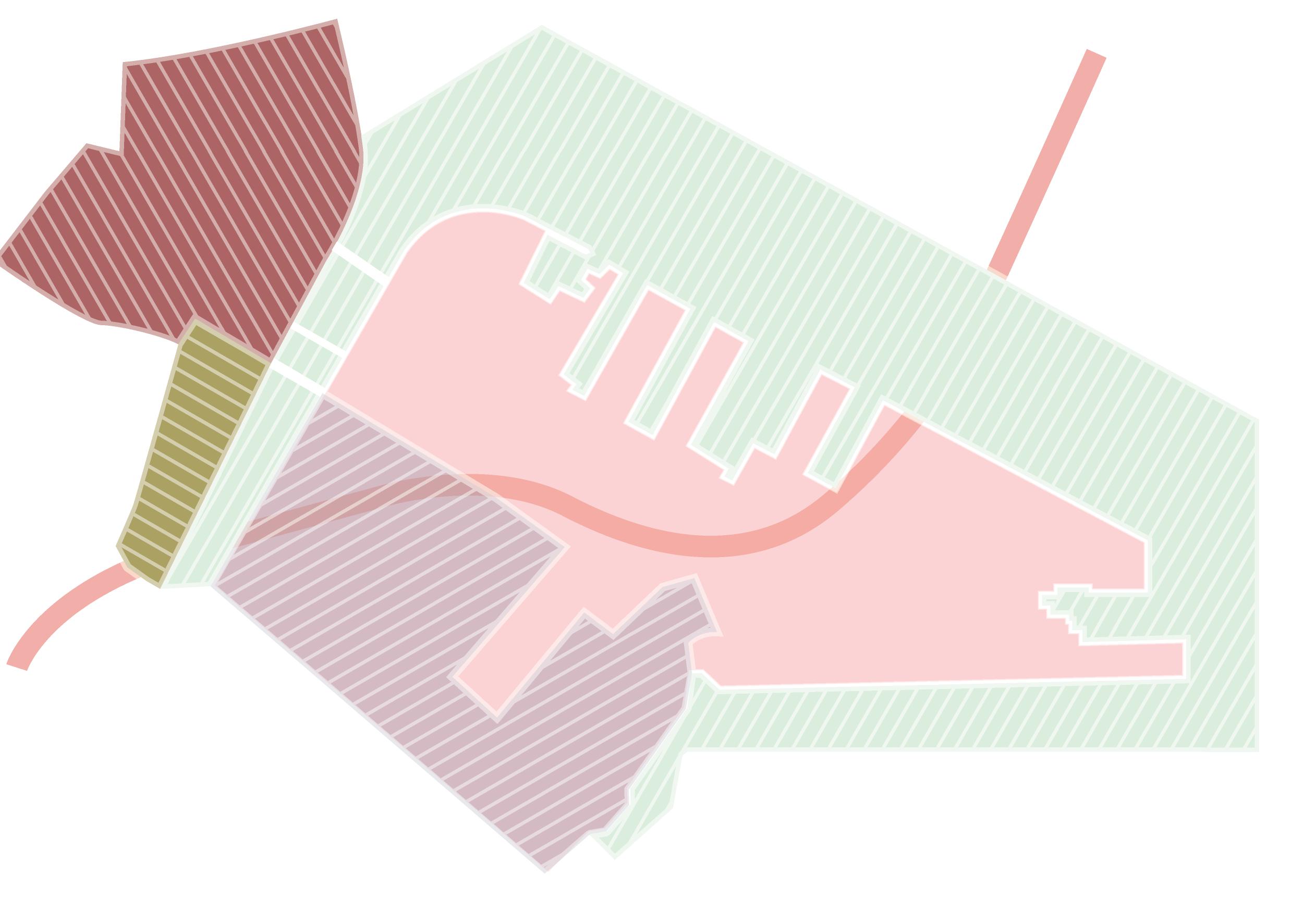

Physically, the Seaport is a peninsula, with the Fort Point Channel, the Reserved Channel, and the harbor surrounding the land on three sides. The Seaport is also a penisula in terms of its limited pedestrian access, allowing one way in by foot. There seems to be an isolated nature to the Seaport, one that can be explained by its aforementioned history. The parking lots and railway yards cut off the waterfront from South Boston aka Southie, the historically working class history that was mostly inhabited by the citizens who worked on the waterfront. The harbor and Reserved Channel still act as the two other sides of the peninsula, but the Fort Point Channel is erased by three currently accessible bridges that connect the Seaport to the Financial district.

The highway, here, also acts as a buffer. Unlike historical examples where highways cut through low income or predominately minority neighborhoods, Interstate 90 actually acts as a guiding line as to where develop will go. Almost every plot north of the line is developing quickly into skyscrapers with much more planned for the future.

By having those who enter the Seaport carefully funneled through a few limited arteries, who is allowed in can be managed in a very subtle way. Unless you are walking over from the financial district, the streets are largely unforgiving to pedestrian access, and does not inspire any bicycle travel either. So you either need a car to enter, or you need to work in the financial district. This is an economic barrier emerging.

“I FELT LIKE I WASN’T SUPPOSED TO BE WALKING THERE, I HAD TO LEARN WHAT STREETS TO WALK ON” =INTERVIEWEE WHO WORKED IN THE SEAPORT

IF AT ANY TIME PLANNERS

HAD BEEN ASKED TO DESIGN CITIES THAT WOULD MAKE LIFE DIFFICULT AND DISCOURAGE PEOPLE FROM BEING OUTDOORS, IT ... WAS FOR ALL THE CITIES DEVELOPED IN THE 20TH CENTURY ON THIS IDEOLOGICAL BASIS =JAN GEHL

THE SEAPORT HAS A SCALE ISSUE

This is the welcoming into the Seaport from almost any angle; long, wide roads with very little happening at the pedestrian scale. There are sidewalks though, and even a few bike lanes that I enjoyed while documenting the neighborhood, however they were severely under utilized. Jan Gehl, in studying public life, pointed out that people are no longer on the streets in cities with highly developed economies, as there are fewer people who have to sell trinkets, work, or do errands on the street to make a living. The highly developed economy is ever present with the financial logos and rapid development everywhere, but there is still more towards understanding why the streets are empty. Gehl also points out that we can only recognize human activity at around 100 meters, and then

hear loud human expression at 35 meters, and then understand emotion at less than 22 meters. It is only within 7 meters however that genuine conversation can take place. Clearly, the length of these streets far exceed 100 meters, the larger ones exceed 35 meters and the smaller ones mostly exceed 22 meters. Even the sidewalk in the top right is pushing 7 meters.

Gehl stated that we are geared towards looking ahead of us, and down rather than up, and that communication with the street happens in the first two stories, is feasible from the third and fourth stories, and then is completely lost from the fifth floor and above. Where the Seaport excels in verticality, it also succeeds in removing dozens of floors from the urban fabric below.

THE ARCHITECTURE

“Developments in society, economy and building technology have gradually resulted in urban areas and standalone buildings on an unprecedented scale. Greater wealth has spawned a greater need for space for all functions. Factories, offices, shops and housing: all units have grown. Building structures and commissions have grown correspondingly and the construction tempo is faster. Building technology has kept pace, with rational production methods that allow new broader, longer and higher edifices to be built . Whereas in the past cities were built by adding new buildings along public spaces, today new urban areas are often collections of random, spectacular stand-alone buildings between parking lots and large roads.”

=Jan Gehl

The human being forgotten in the scale has led to a very boring architectural experience on the ground. Even when looking up into the sky at these behemoths, these marvels of engineering, the viewer could be quickly bored by the repeated elements. It would make sense if these building were designed our the mid-century, when planners like Le Corbusier designed away what he saw as unhygienic slums, but these buildings are much more recent. These planners are anticipating some great economic influx that is yet to happen. In a city with a housing crisis, one wouldn’t think that it would be so hard sell of these apartments, but that’s because these apartments aren’t responding to a demand for low-income housing, they are creating a demand for high end condos. Each little room is its own individual world, meant to highlight the power of the individual over the power of the collective, this also is shown in the treatment of the public realm in the Seaport.

THE PUBLIC REALM

There is very little in the Seaport to remind you that you might be a citizen of a country, state, township, or any other collective body. The public “dog park” in the top row is a sad peak into the life of a resident pet of the Seaport, but an even sadder look at how much public space is allocated to the people as well. Although the newly installed Pier 4 park and “Public Green” exist within walking distance, pets are not allowed and so they are relegated to do their business on a fake fire hydrant on astroturf the size of a parking space.

There are no public schools in the Seaport, no public swimming pools, no community centers, and no public libraries. The only explicit reminder (roads, sewage, and other services being more subtle

ones) that a state still exists is the courthouse and the very present police. This works well with the neoliberal ideology, as it outsources the cost of security. The courthouse sits in the Northern corner of the Seaport, like a watchtower over the whole site. The only state presence here is punitive. This helps the neoliberal ideology also gather public support ironically, as it reinforces the idea that you should be unhappy with where your taxes go, when you fail to see any public good coming from them.

By removing your imagination for a public, you start to see yourself as an individual rather than as something more. This individuality can turn into isolation, and this isolation can become loneliness, and this loneliness can be capitalized on.

“IN

A CAPITAL-ALIGNED STATE, IT IS IN THE STATE’S INTEREST TO SHAPE INDIVIDUALS’ SOCIAL IMAGINARIES TO EMBRACE THE DISCOURSES OF THE FREE MARKET AND INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS AND

TO DOWNPLAY COLLECTIVE RESPONSIBILITY” = KATHERINE B. HANKINS

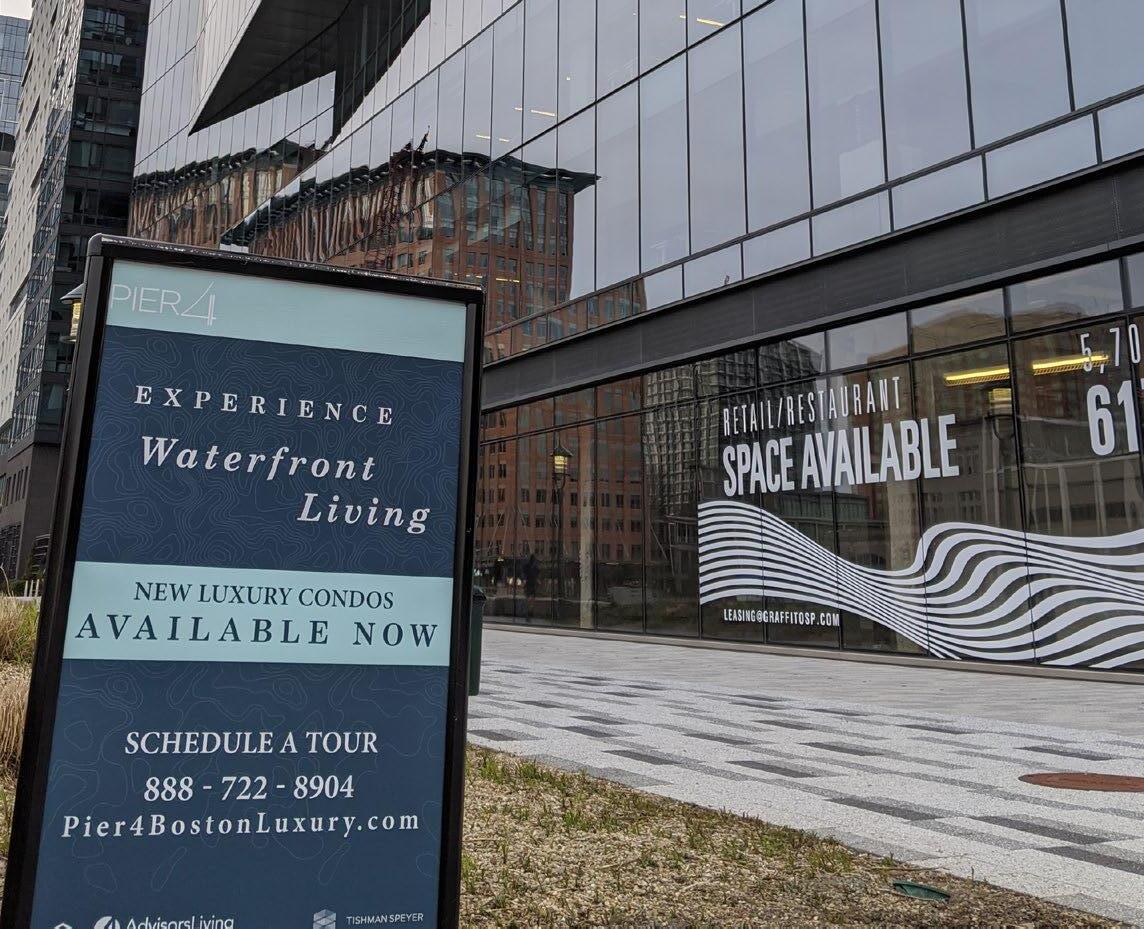

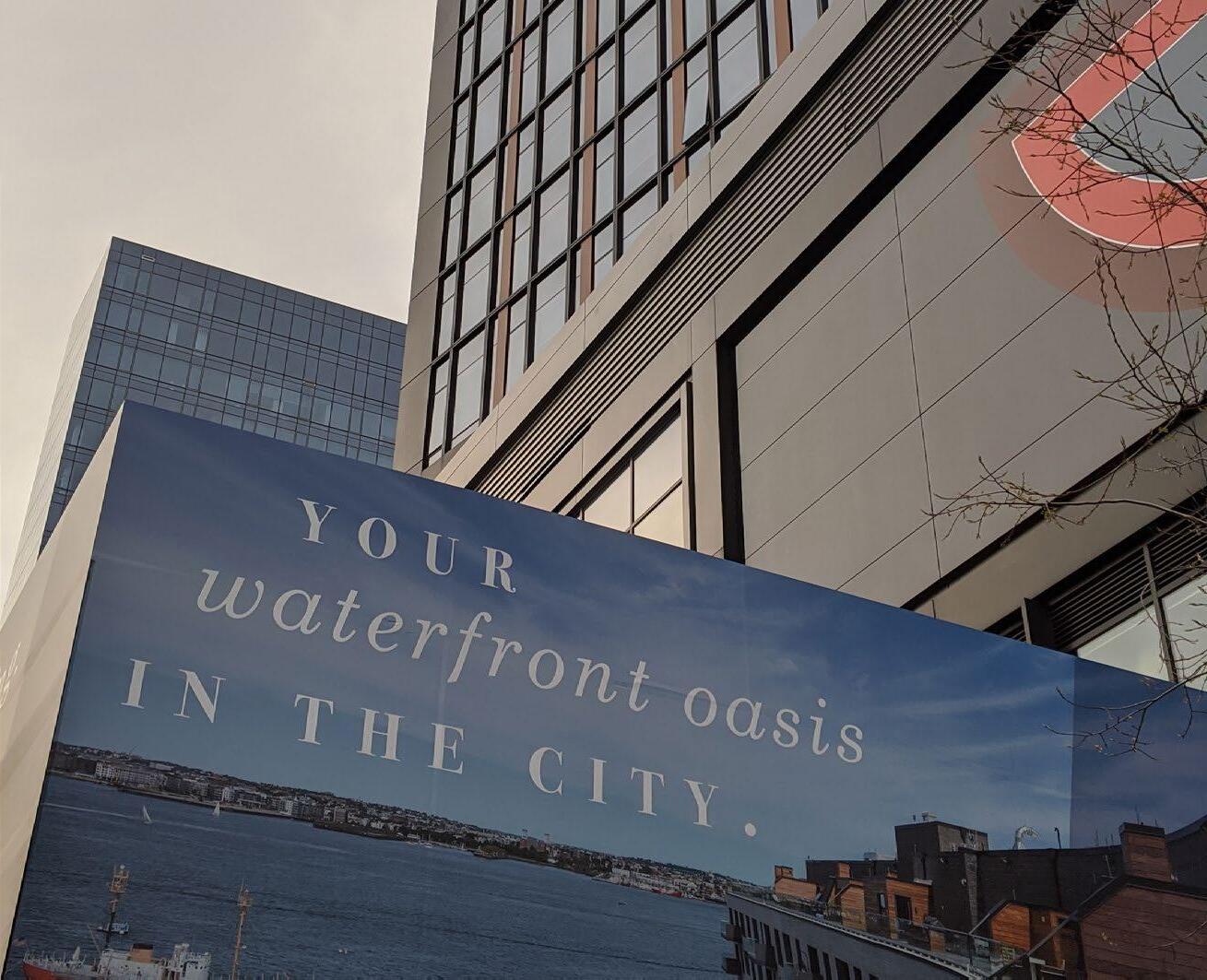

THE BRANDING

To capitalize on the loneliness, the apartments of the Seaport market a lifestyle rather than just a couple rooms and some kitchen appliances. All the advertisements below seem to offer stability, community, or escape. When you feel alone, you want to fit in and, if you can afford to buy it, you will purchase a ticket into a certain social space for $2,866. Will it solve your feelings of isolation? Probably not, but that’s why they include gym memberships and maps to the nearest restaurants.

BRANDING

“PEOPLE WHO NEED HOUSING DON’T NEED IT MARKETED TOWARDS THEM”

THE FUTURE

So will all this be enough? Will we see a vibrant neighborhood with connection to place, spontaneous social interactions, and lots of activated street space and everything else that makes for a healthy street life? I doubt it. Since according to most projections much of this real estate is incredibly vulnerable to rising sea levels and the increased extreme weather events brought on by climate change.

There seems to be an air of optimism coming from developers who are preparing by moving electrical components up a floor and by creating flood walls. The St. Regis condo tower is currently be constructed to allow for the lobby to rise by four feet. The developer hopes that his neighbors will do the same.

But this brings up the issue, these are all private fixes to a public issue. Will the streets also be raised by four feet? Will the consumer still want to take their chances in a partially flooded neighborhood? I doubt it.

This is what happens when you render the state invisible through capital accumulation and 40 years of efforts to promote measures of austerity, trickle down economics, and government so small it can do little now to interfere with the snowball of private real estate. Too much energy has been spent on making sure there are still business opening when the floods come, and not enough time worried about if there will even be customers left to patronize these places. The Seaport is not alone in this crime, however, and will be merely one island in an archipelago of doomed, short-sighted ventures dotting the oceans.

“GLASS HARDLY BENDS BEFORE IT BREAKS”

Armborst, Tobias, et al. The Arsenal of Exclusion & Inclusion. Actar, 2017.

BDPA Neighborhood Overview - http://www.bostonplans.org/planning/climate-changeenvironmental-planning/south-boston-waterfront

Bookchin, Murray. The Limits of the City. Black Rose Books, 1991.

Carlock, Catherine. “Here’s the New Vision for Boston’s Seaport Neighborhood.” Bizjournals. com, 8 Feb. 2017, www.bizjournals.com/boston/news/2017/02/08/here-s-the-new-vision-forboston-s-seaport.html.

Gehl, Jan, and Birgitte Svarre. How to Study Public Life. Island Press, 2013.

Gibson, Amber. “How The Seaport District Became Boston’s Hottest Neighborhood.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 29 Nov. 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/ambergibson/2019/11/29/how-theseaport-district-became-bostons-hottest-neighborhood/.

Gopal, Parshant, and Brian K Sullivan. “Boston Built a New Waterfront Just in Time for the Apocalypse.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 18 June 2019, www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2019-06-18/boston-built-a-new-waterfront-just-in-time-for-the-apocalypse.

Gurley, Gabrielle. “Boston’s Rendezvous with Climate Destiny.” The American Prospect, 5 Jan. 2018, prospect.org/environment/boston-s-rendezvous-climate-destiny/.

Hankins, Katherine B., and Emily M. Powers. “The Disappearance of the State from ‘Livable’ Urban Spaces.” Antipode, vol. 41, no. 5, 2009, pp. 845–866., doi:10.1111/j.14678330.2009.00699.x.

Pier 4, 100. “UDR Apartments 100 Pier 4.” UDR.com, 2020, www.udr.com/boston-apartments/ seaport/pier-4/.

Seaport Marketing Website - https://www.bostonseaport.xyz/

“Sense and Scale.” Cities for People, by Jan Gehl, Island Press, 2010, pp. 32–59.

Stein, Samuel. Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State. Verso, 2019.

“To Measure - Vitality, Livability, and Sense of Place .” Urban Transformation Understanding City Design and Form, by Peter Bosselmann, Island Press, 2014.

Urban Transformations Chapter 3 (Jan 27 Reading)

Wide Awake! - Parquet Courts (2018) - Rough Trade Records