The Caretaker’s Cookbook

An Architectural Future of Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, Year 2051

And Accompanying Samples of Experiences and Strategies to Inspire a Thriving Post-Dystopian Community of Your Own

Hailey Algoe & Ania Yee-Boguinskaia Water Futures: A Desert Imaginary Advanced Studio Fall 2021, UTSOA Professor Stephanie Choi

In the legends, they say the River was once green, teeming with life. It cared for us, giving people food, healing, and nourishment. And in turn, we took care of it.

But, as more and more settlers came to the land now known as Los Angeles, they didn’t understand that the River’s floods were life-giving. It washed away the structures they insisted should be permanent. So, they paved over the River’s course, confining its waters, and in turn, they paved over most of the rest of the city, too.

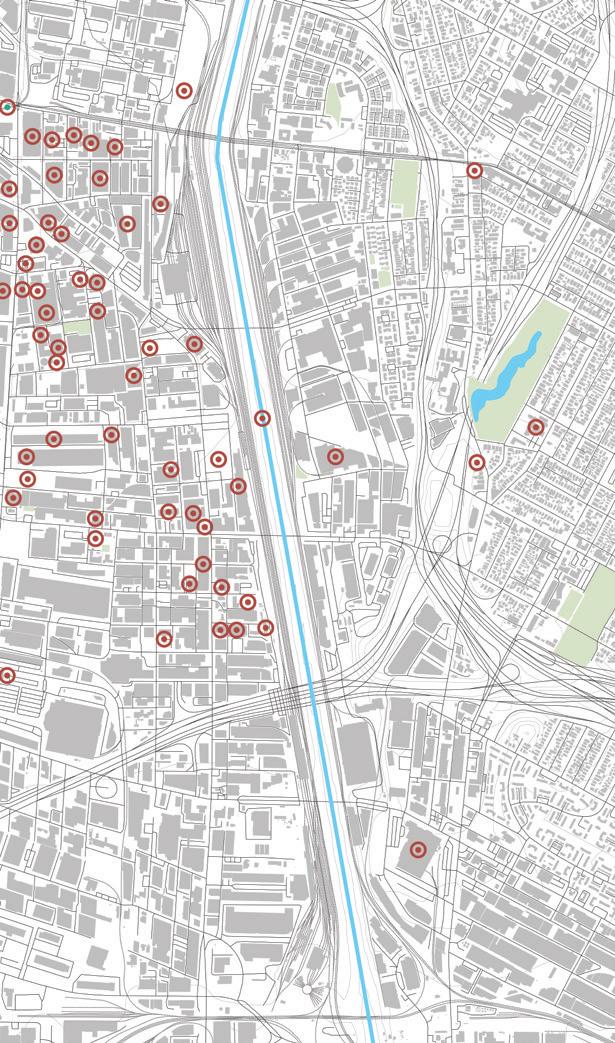

By 2021, the River all but forgotten in the backdrop, developers came to the Arts District and began pushing out the people who had made a home there among the neglected warehouses. Architects built massive projects atop sites that once held communities of artists, and communities of Native peoples in harmony with the River long before them.

Proposed Major Development

Major Development Under Construction Completed Major Development

Abandoned by Development Comapny/Landlord

But as society began collapsing in on itself, they were abandoned, one by one.

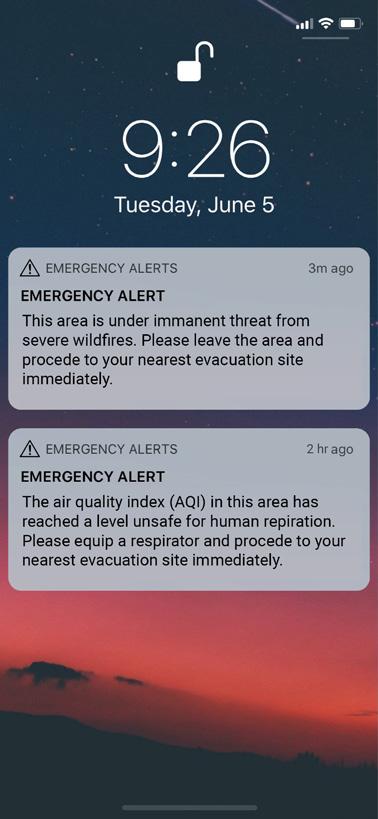

Climate collapse came to California faster than anyone expected, though in retrospect, we all should have seen the signs. First came the wildfires. Then, we ran out of water. By the dawn of the 2030s, Santa Monica was underwater, and life as we knew it was gone.

As fires and flooding decimated the hills and the coasts, those who could afford to fled north. Those who couldn’t came Downtown, where at least things weren’t underwater or up in flames. But, among the decaying structures and chaos of economic collapse, it was dangerous here, too. Central Valley farmers had slowed their production to a trickle. Food was scarce. Water was scarcer.

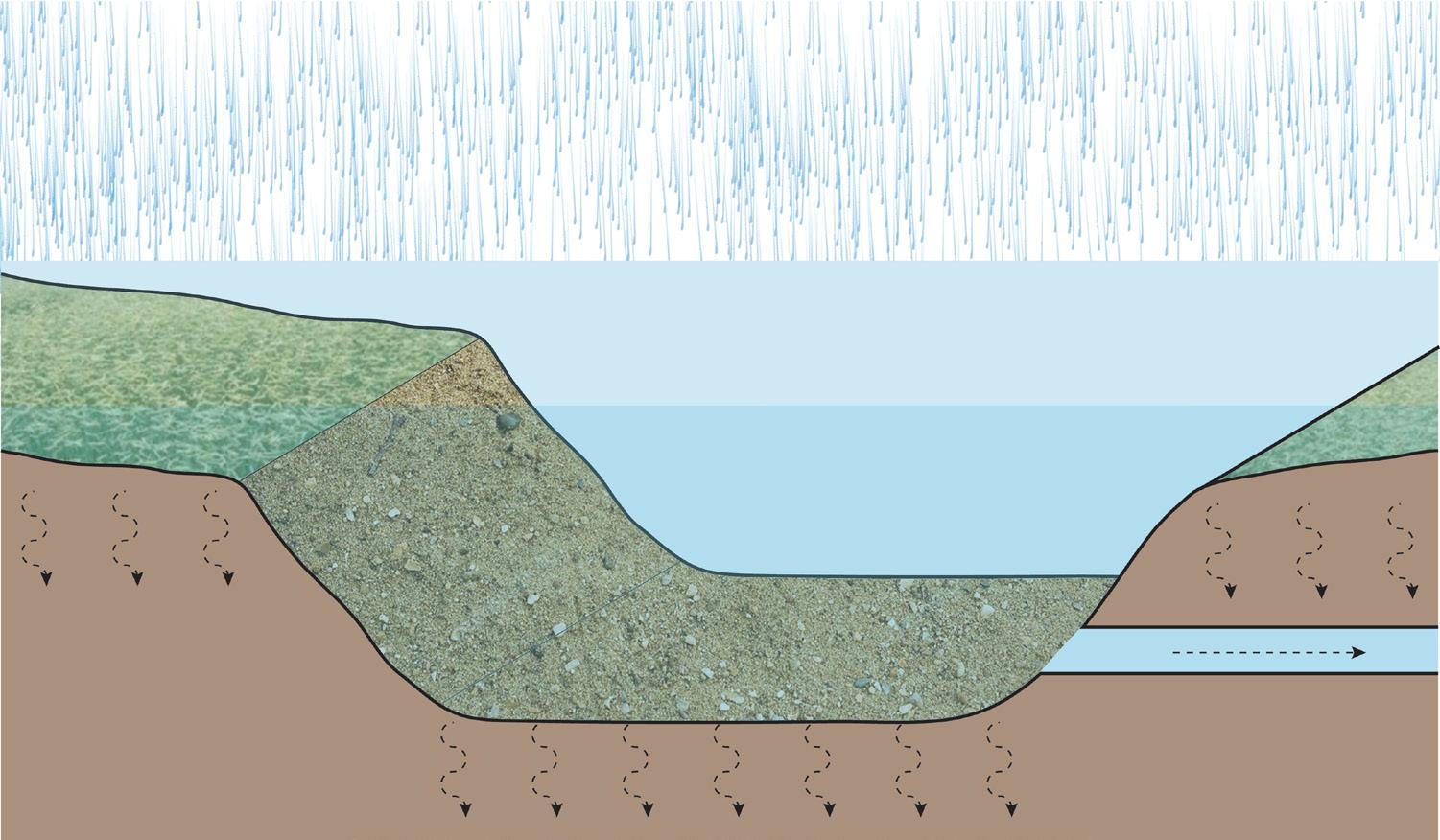

Polluted stormwater runoffcollects across LA

Channelized concrete prevents flooding, but also groundwater inflitration

Impervious surfaces throughout LA prevent groundwater infiltration

Desalinated water from plants off of the coast was prohibitively expensive. Meanwhile, as occasional torrential rains increased amidst the worsening climate disaster, the water held in the River’s concrete banks was far too polluted to drink. It flowed out to the ocean, as though slipping away between our fingers.

But, the people of my community had an idea. Boyle Heights banded together and began chipping away at the River’s concrete, finding ways to harvest the water through diversion and treatment technologies, but also allowing the floods to return.

Native riparian planting

Floodwaters wash over riverfront land, absorb into soil

Water diverted for treatment, community use

Now, with each flood, we can store the water, treat it, and save it for times of drought later. Everything we can’t contain goes back to the soil, enriching it for our own agriculture. We can produce our own food and water now. We have no need for the desalination plants.

Permeable riverbed allows infiltration, replenishes groundwater

Permeable riverbed allows infiltration, replenishes groundwater

In the decades since we first began tearing out the concrete, our community has been resilient in the face of climate collapse and urban decay around us. By utilizing models of collective governance, mutual aid, and environmental caretaking, we have all joined together with our existing skills to create a new heartbeat for our community along the River.

By showing you a few sites in Boyle Heights and the strategies we have used to form a self-sufficient, thriving community of care, I hope that you can utilize some of these tactics to create new societies of your own.

Mariachi Plaza Theodore Roosevelt High School

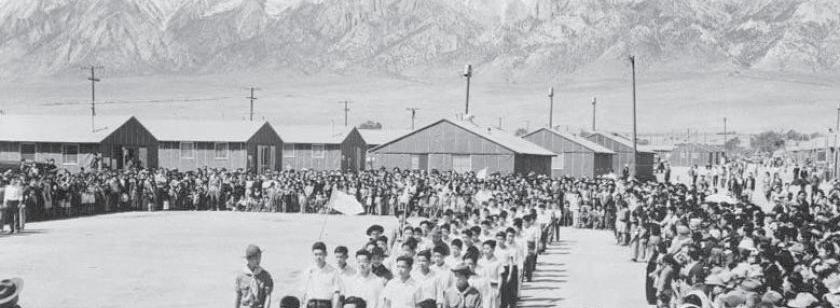

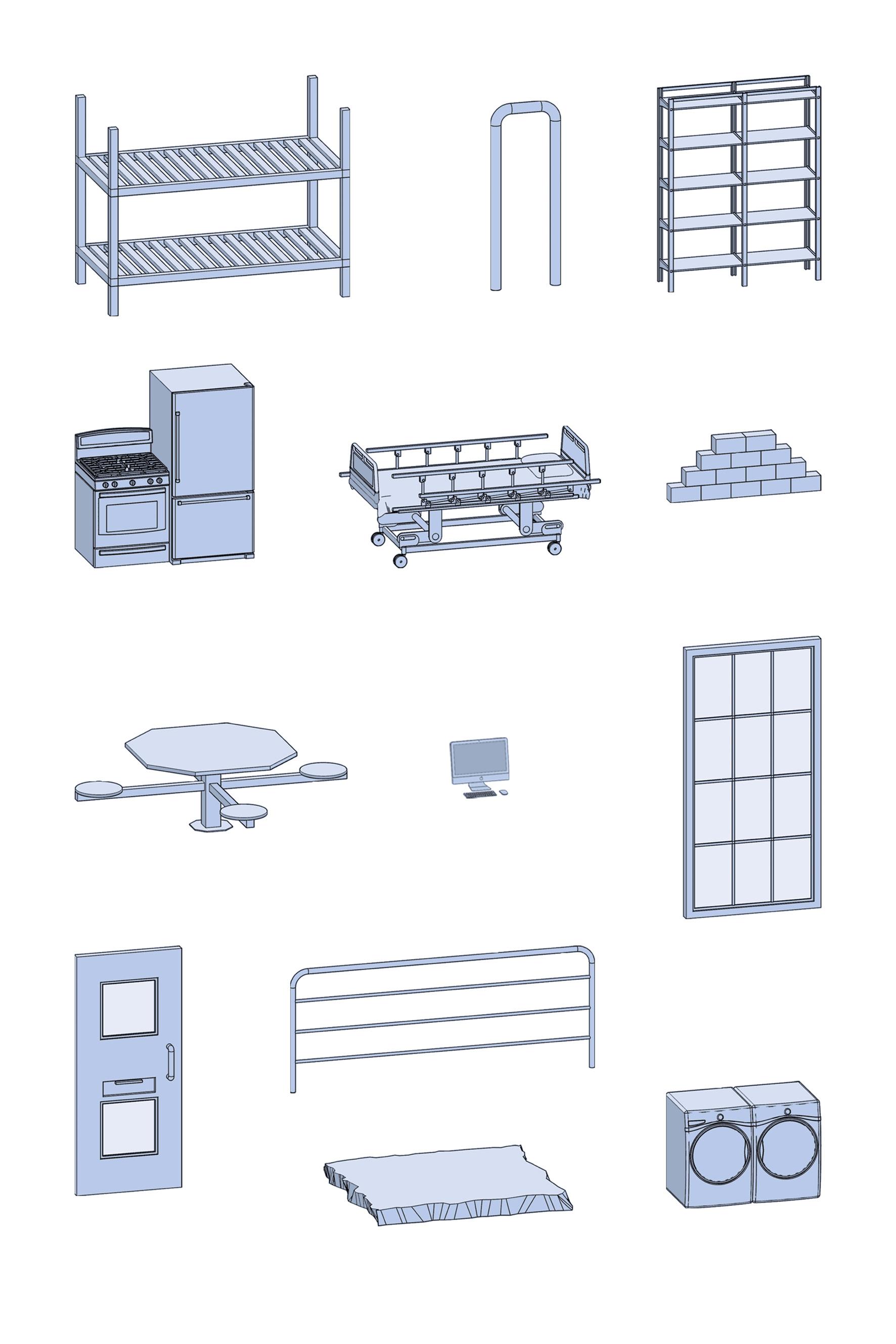

In the earliest days of the chaos Downtown, as societal systems collapsed, there was a great victory. The Twin Towers Correctional Facility had always loomed over us just across the River, incarcerating our community members and forcing cruelty and abuses upon them. The prison was liberated, and we began working towards new models of community justice.

We couldn’t just leave the buildings there, a shadow of so much cruelty and ugliness cast over the new community we were trying to build. So, the structure was dismantled, its materials salvaged to create new structures from the ruins of the old, and a memorial was left in its place: a memorial to all of the victims of police brutality and the prison industrial complex. A memorial to all of the lives that were destroyed by the building which once stood here.

1500x stainless steel bunks

0.5 mi metal pipes, plumbing

100x industrial shelving units

2000x intact cinder blocks

Industrial kitchen equipment

10x industrial stove units

15x industrial refrigerators

15x industrial freezers

Assorted cooking implements, utensils

100x metal tables

Medical equipment

100x inpatient beds

Assorted medical monitoring devices

Assorted antibiotics, medications

15x computers

300x iron railing modules, assorted sizes

500x steel doors

3 tons concrete, to be reused in rubble masonry

100x interior windows, various sizes

Industrial laundry equipment, 50 units

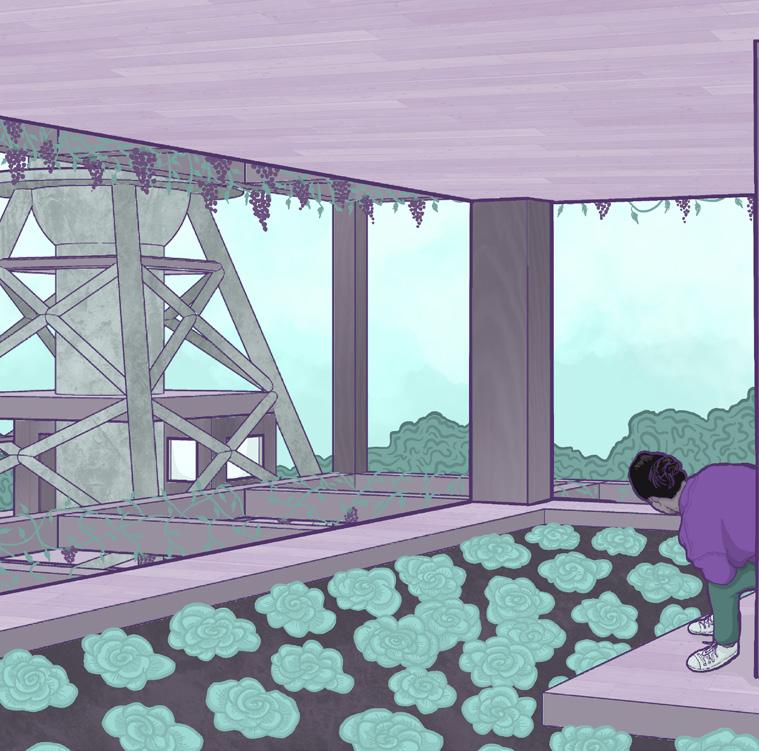

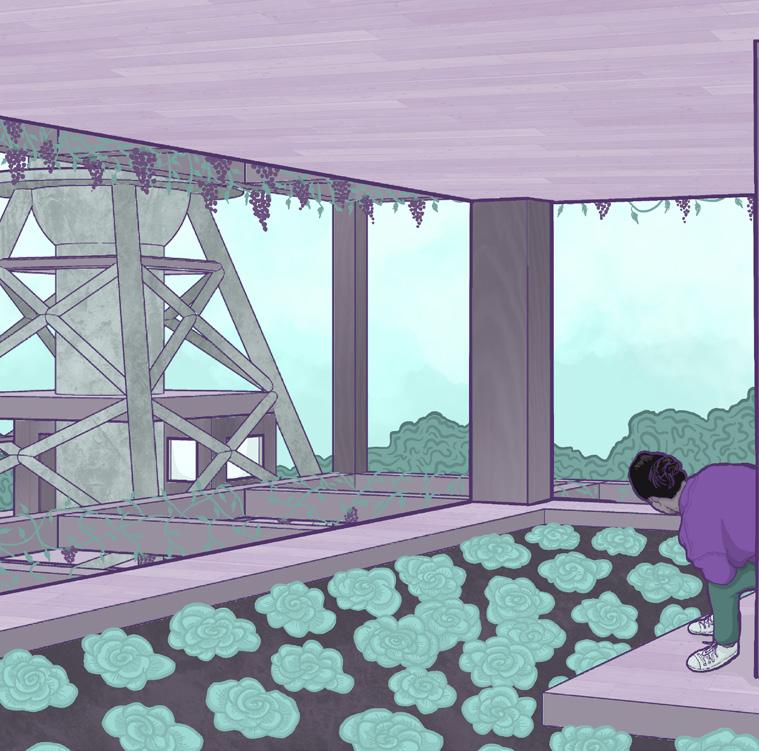

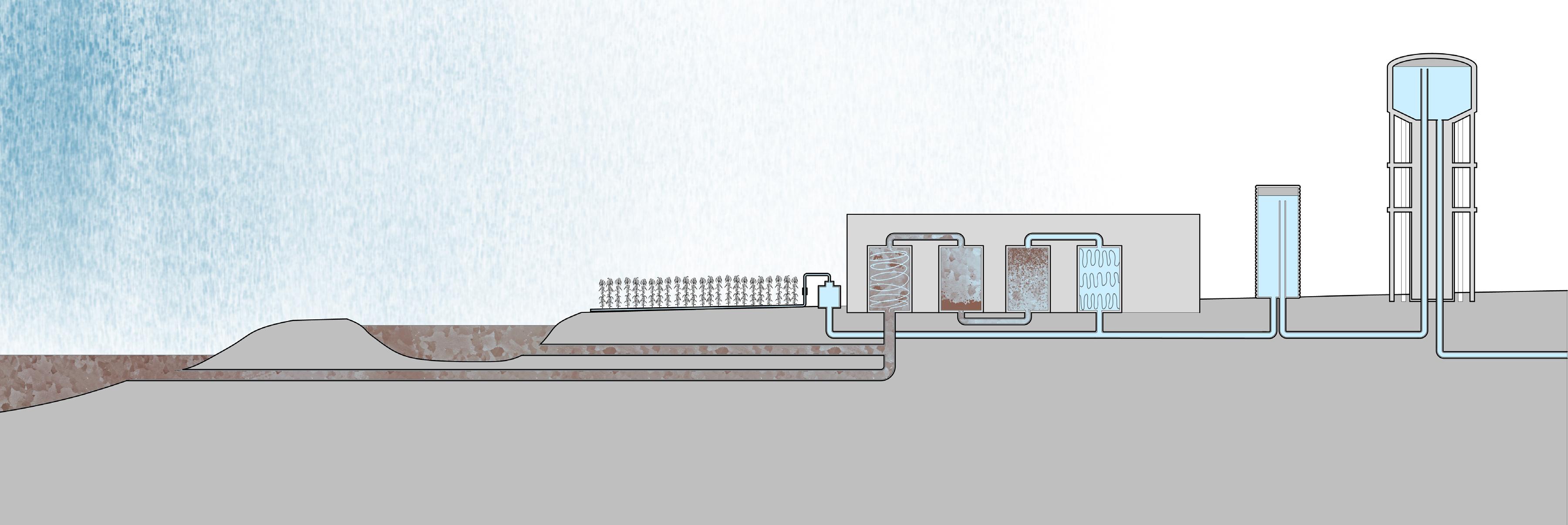

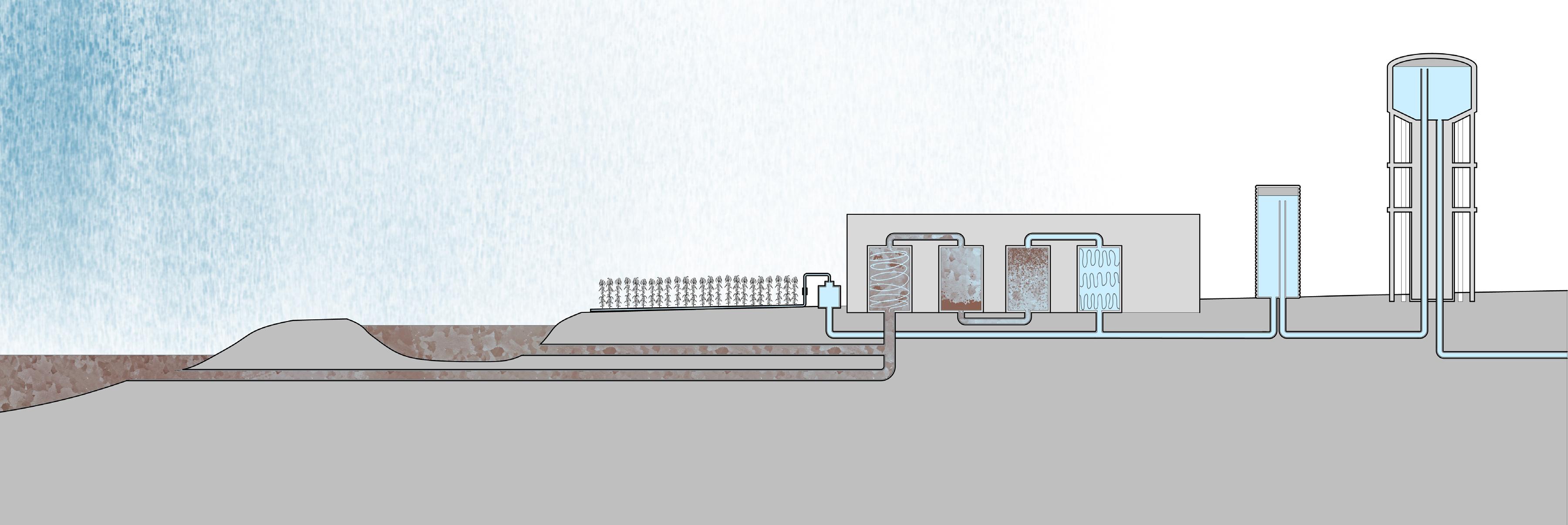

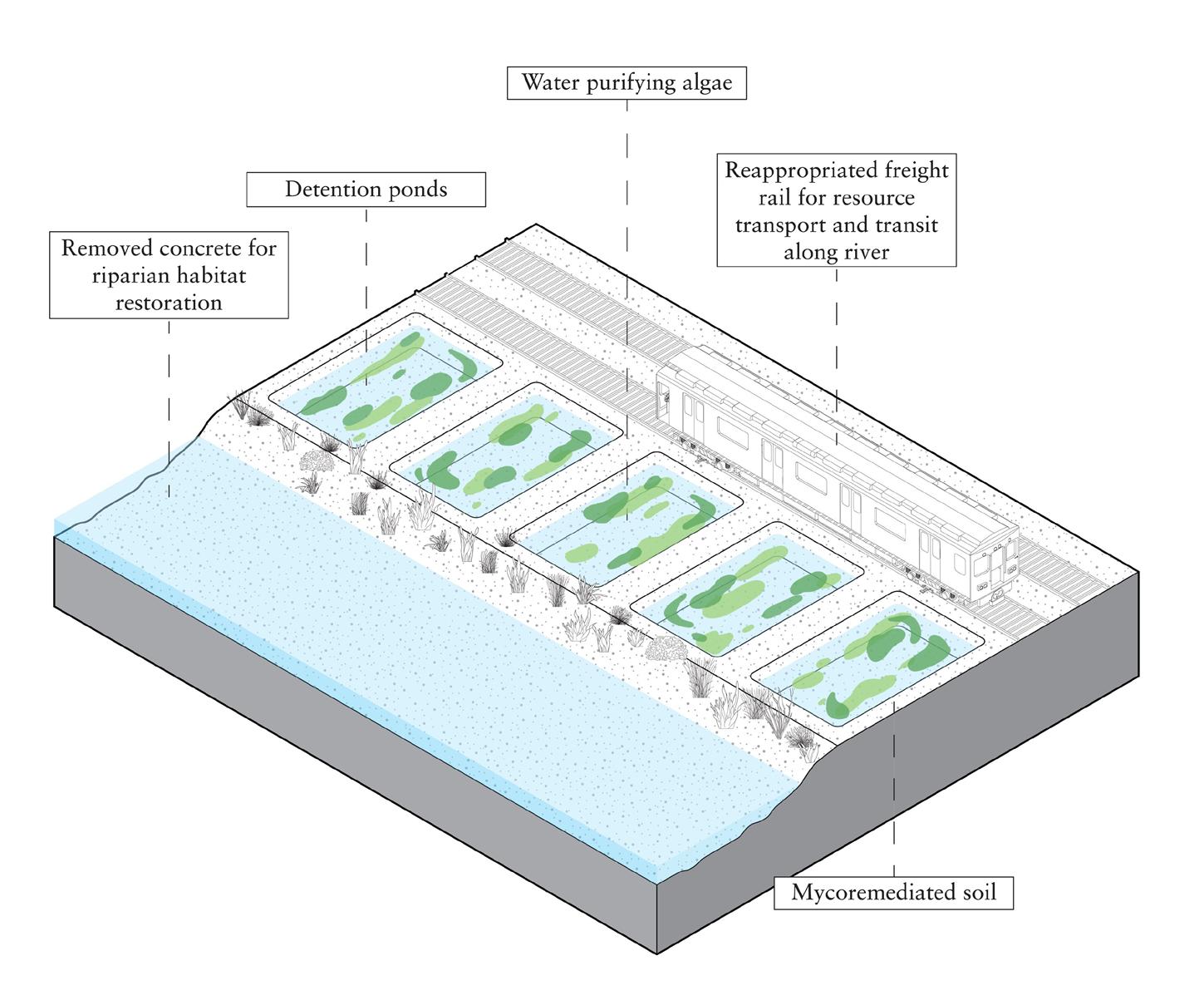

The warehouses lining the banks of the LA River hold tremendous importance in our community: they are the starting point of the water purification process which supplies our whole community with much needed irrigation and potable drinking water. The torrential rains that fall occasionally throughout the year cause the River to surge with polluted stormwater runoff from all over Los Angeles. We divert this excess water using detention ponds and diversion pipes lining the river, purifying it in the warehouses along the banks. Some of the water is then stored in cisterns or used to irrigate agriculture incorporated into the warehouse agricultural and water co-ops, and the rest is distributed to the remainder of Boyle Heights.

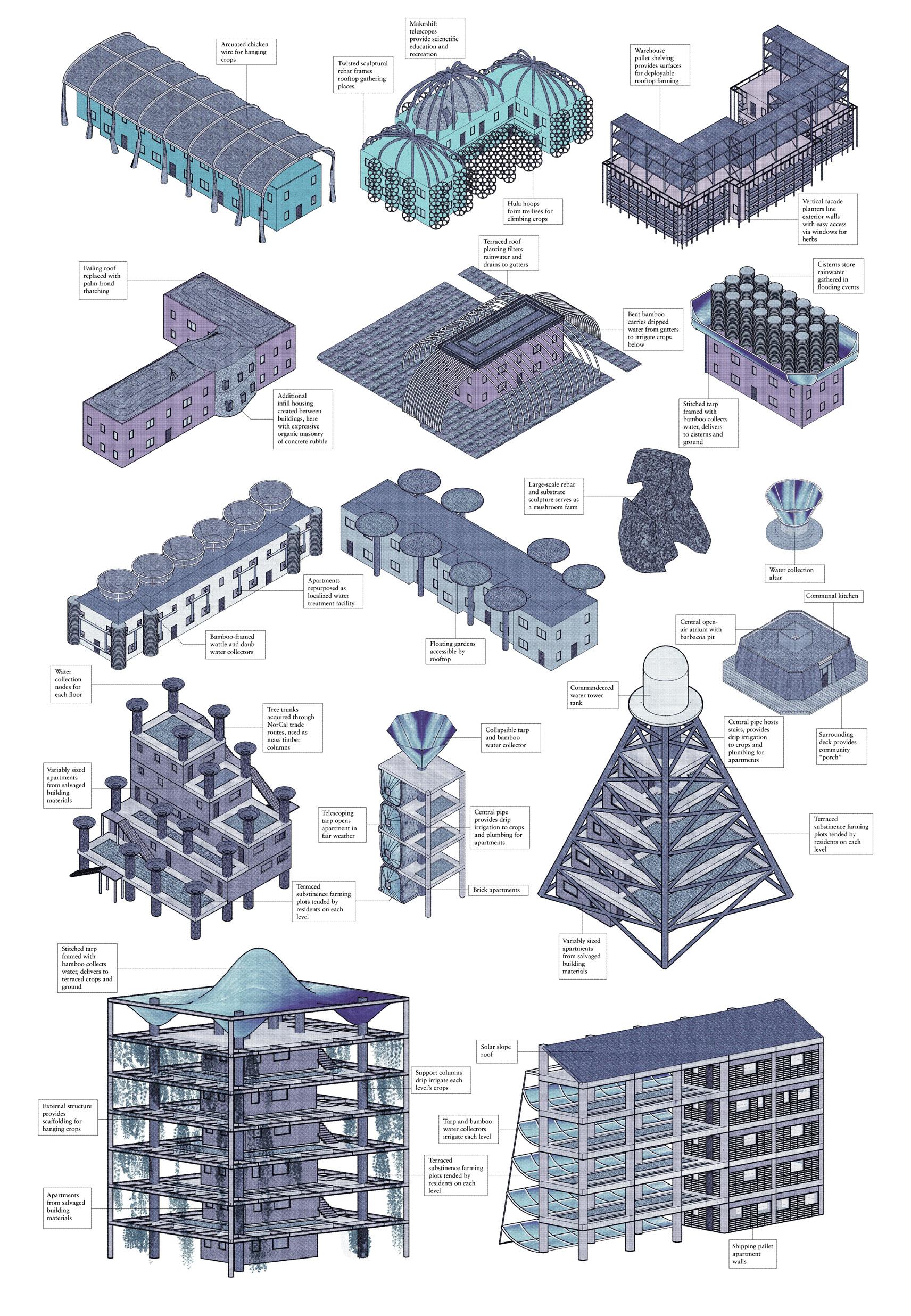

The residents of the Boyle Heights Produce and Water Collective are engaged in a cooperative living structure. Several of their warehouses serve as water treatment, which they maintain for the rest of the city. Additionally, agriculture is incorporated both in and on top of the existing warehouse structures. Outside of their water and agricultural caretaking responsibilities, residents inhabit cooperative studio units where they create art in fellowship programs with local organizations.

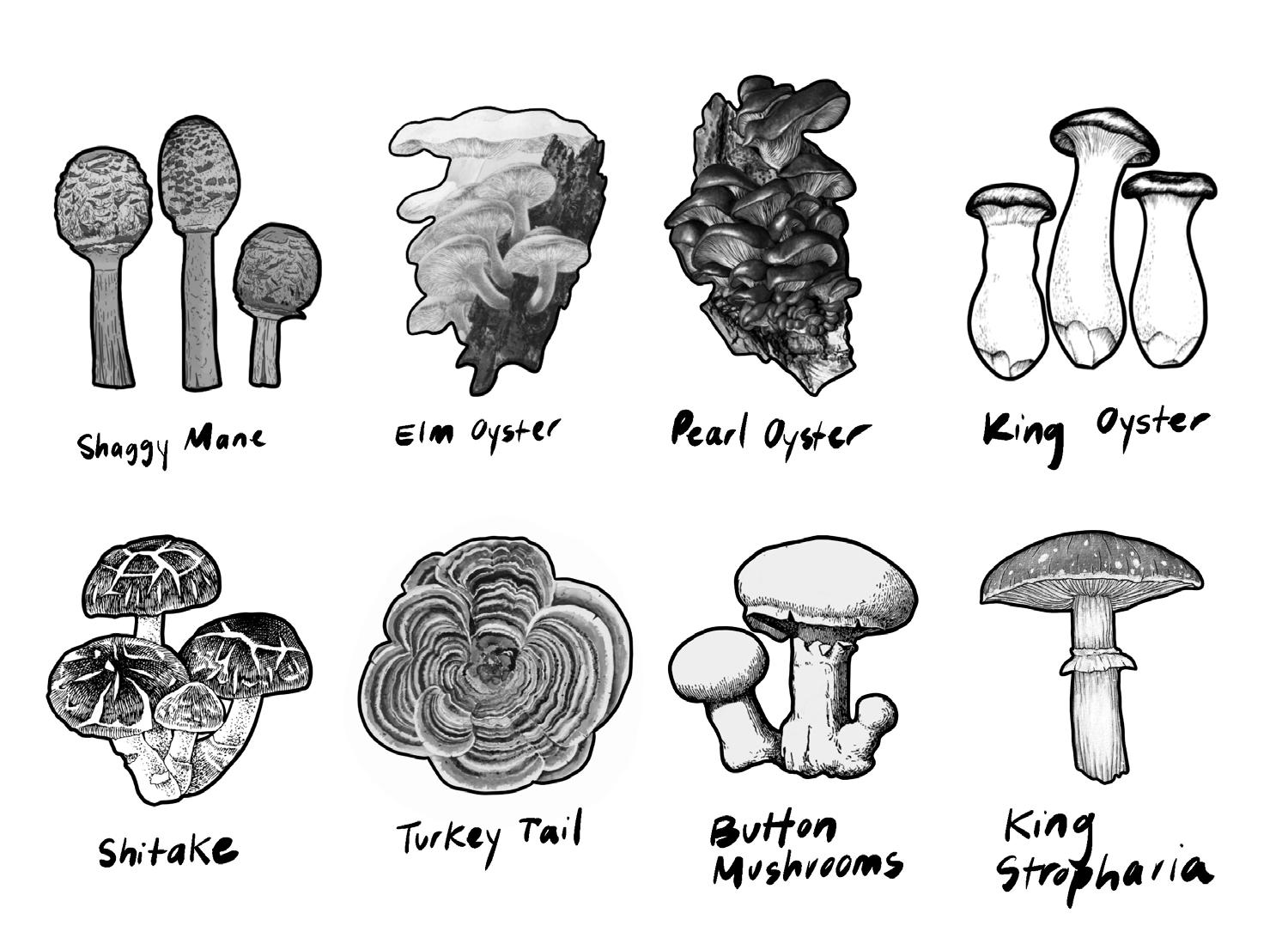

With Los Angeles’ drought-flood cycles growing more extreme due to the increasing effects of climate change, our newly liberated society needed to take immediate action to ensure water security during times of drought. We rehabilitated The Union Pacific Railyard— previously an expansive site polluted by shipping containers, railroad tracks, and contaminated soil— and turned it into a key infrastructural, ecological, and cultural site with caretaking of water as the principal objective. We restored riparian habitat along the riverfront, employed bioremediation techniques, and built detention ponds to store excess water.

After the LA Unified School District disbanded in the early years of society’s collapse, we joined together to create the New Boyle Heights School District. The curriculum is based on principles of caretaking across all levels of society, educating kids to carry on the work of maintaining our community for years to come. Here at Roosevelt High School, housing is provided for teachers and their families on campus. Pictured here is a structure of repurposed freight containers.

In addition to a core curriculum, numerous trades are taught across the school in pavilions and outbuildings scattered around campus. Welding, carpentry, construction, childcare, arts, and more are all integrated in strong programs. Pictured here is a geodesic greenhouse from salvaged glass, used to grow produce for student meals and traded with the rest of the community.

New Boyle Heights School District Theodore Roosevelt High School 456 S Mathews St, Los Angeles, CA 90033

Principal: Nicolette Morales

Vice Principal: Liliana Mendoza Vice Principal: Danielle Rulante

Welcome to your first year here at Theodore Roosevelt High School, Rough Riders!

We are so excited to make the 2051-2052 school year a great one!

Over the course of your first semester, you will have the opportunity to experience many of the wonderful caretaking disciplines offered here at RHS. At the beginning of the spring semester, you will be asked to declare your Focus, or the caretaking track which you would like to dedicate your primary course of study to over the next four years, in addition to our core curriculum. Every single one of our programs here will prepare you for an essential element of caring for our community here in Boyle Heights, so you can’t go wrong! Please see below a list of the caretaking Focuses offered here at RHS. Have a great first semester, and go Rough Riders!

The New Boyle Heights School District’s Caretaking Curriculum Mission Statement is as follows: We seek to educate and empower our students with the trades, knowledge, and techniques to care for their community, their environment, themselves, and each other.

Body Care Focuses: Childcare Meal Care Healthcare Fitness Care Mind Care Focuses: Spiritual Care Mental Healthcare Guidance Care Educational Care Environmental Care Focuses: Energy Care Waste Care Nature Care Animal Care Water Care Construction Care Agricultural Care Planning Care Infrastructural Care

Community Care Focuses: Cultural Care Safety Care Transportation Care Resource Care Market Care Building Care Machine Care

The the banal, repetitive, and spatially wasteful suburban housing models constructed by developers on S Utah St & E 3rd St were making their residents miserable. There was too much space allotted to cars and not enough for quality community space, farming, and resource collection. Families longed to be able to house multiple generations under one roof to reincorporate traditional means of cohabitation.

Some families in the neighborhood fled the city, which gave residents the opportunity to demolish their houses to create a shared central green space and community garden. The leftover materials, along with those brought from other sites, were reused to build a much more dense and self-sufficient generational community. The demolition of private fences and the maintenance of a shared perimeter fence serves as a symbol of mutual care and protection for the block.

Collapsible tarp water collector

Solar panels

Greenhouse with water collecting roof

Collapsible tarp water collector

Solar panels

Greenhouse with water collecting roof

The residents of Wyvernwood. a historic garden apartment complex, have begun creating new structures in addition to adapting their existing buildings to a new, self-sufficient mode of living. “Garden apartments” take on a new definition in various subsistence farming towers constructed from salvaged materials and lumber sourced from trade routes with Northern California.

Community kitchens complete with central barbacoa pits accent the model of cooperative living among the residents of this densified community, its previously open grassy fields now stippled with new structures for the climate refugees arriving in Boyle Heights.

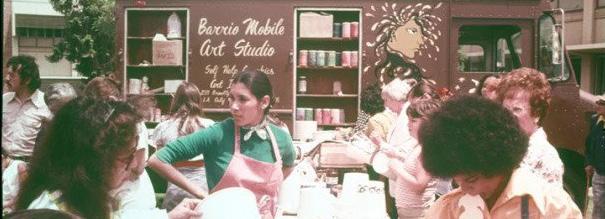

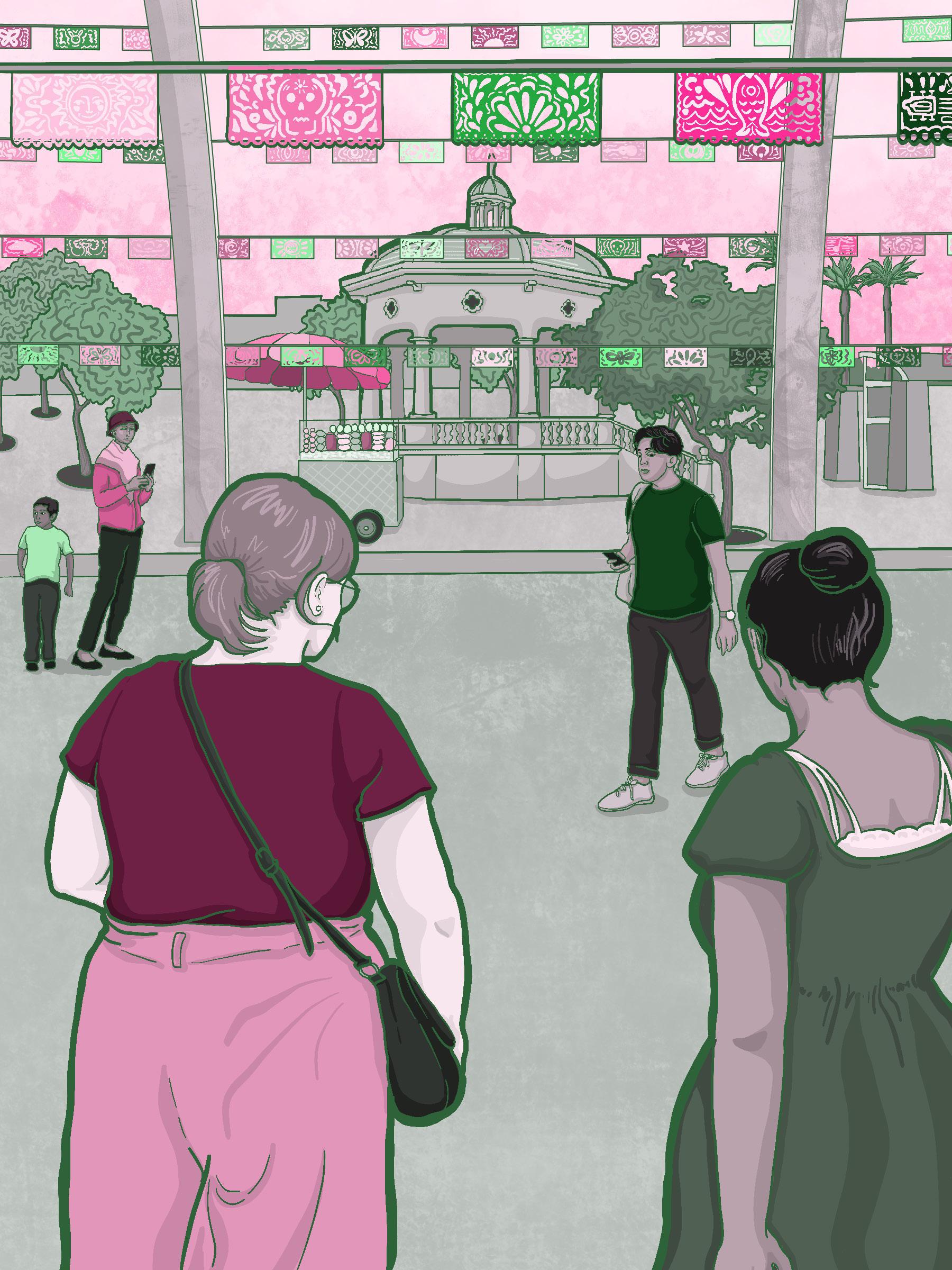

Mariachi Plaza has always been the heart of Boyle Heights. The sounds of mariachis playing, advertising their services for all who might wish to hire them, held fast against the tide of gentrification in the years leading up to society’s collapse. As less and less people could afford cars and gas, we had less need for the parking lots surrounding the plaza, so we converted them into expansions of the public space. One lot became a park with playgrounds and pavilions for hosting quinceñeras, connected to the plaza across 1st street by a series of arches hung with banners of handmade papel picado. Another lot hosts a large market hall for hosting swap meets, another a community garden and orchard... And of course, loncheras and fruit carts carrying food grown and prepared in our own community still line the street.

Here, the heart of Boyle Heights beats on for a new generation.

Against all odds, we have managed to build a thriving community here among the wreckage that capitalism and climate change wrought on our world. And now, there are promising signs of other communities across the city doing the same thing. Principles of care have a real chance to build a better society for everyone. I hope that in reading about Boyle Heights, you have drawn some inspiration for techniques you can apply in your neighborhood.

And through it all, the connecting force is the River. I imagine it one day flowing through all of Los Angeles restored to its former self, providing us with food, water, and healing. Taking care of us— as long as we take care of it in turn.