ACTIVE URBAN LANDSCAPE

for the Park Station Precinct in Johannesburg

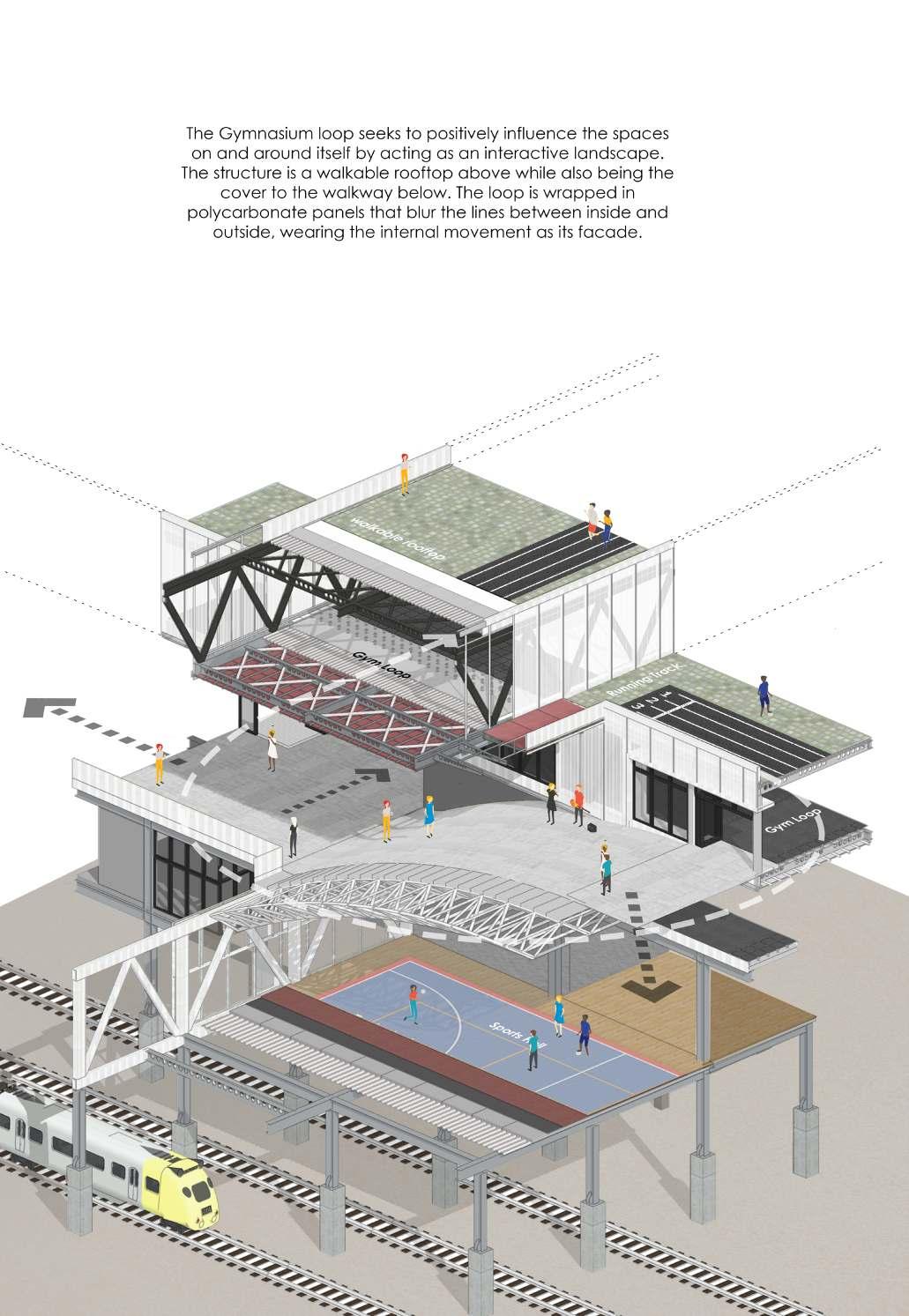

Figure 1. Johannesburg City isometric with Intervention (by author)

Figure 1. Johannesburg City isometric with Intervention (by author)

Submitted in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters in Architecture Professional.

School of Architecture

Nelson Mandela University PO BOX 77000 Gqeberha 6031 South Africa

Date of Completion : November 2022

Declaration

I hereby declare that the thesis titled,TheDesignof anActiveUrbanLandscapefortheParkStation precinct in Johannesburg, has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been submitted , in whole or in part , in any previous application for a degree. External sources are marked by reference or acknowledgment, the rest of the work presented is entirely my own.

Andrew Ian Park Proudman s217643515

I hope that this stamp will be used by other Technology Students as we show the pride in our roots.

Acknowledgments

Masters

Thank you to Andrew Palframan for your wisdom and guidance during this year. My understanding and enthusiasm towards architecture has grown leaps and bounds. Because of this I have been able to produce something that I am proud of. We did this!

Technology

This treatise is a culmination of the years of teaching and influence during my 6 years at Nelson Mandela University. The time spent in the department of Architectural Technology and Interior Design was absolutely fundamental in the development of my skills. I whole heartedly believe in the work that is done by them in preparing students for the architectural industry and will forever advocate that students start their studies in technology before making their way to the more 'theoretical work'.

I am happy to call myself a "Techie" and hope to carry on the legacy of the people that have taken the same path and succeeded. Thank you to all the lecturers that had a hand in my growth. We did this!

Family

To my mom and dad, thank you for allowing me to choose my own path in life, while giving me nothing but love and support along the way. I hope that I can continue to make you proud. I love you so much. Thank you for everything. We did this!

Friends

Here's To the long nights, the early mornings and the endless streams of coffee. Thank you to each and every person that made the hard work bearable. We might not all head in the same direction, but I have faith that we are all going to do awesome things. I am blessed to call you my friends. We did this!

Barriers and buffer zones are re-imagined into highly connected places for people. Central Johannesburg Became the test bed for the model, exploiting its energies of informal trade and transport as fuel for the production of this social architecture.

This treatise was developed from an interest in creating urban place that is centered on physical, social and environmental wellness. The aim of the research was to understand the role of architecture in city space. By drawing on influences like Rem Koolhaas' Delirious New York, Japanese Metabolism and social space philosophies, a set of principles were generated for a public urban space model.

Plagued by a history of modernist and apartheid urban planning that generated disconnected urban environments, South African cities offer an opportunity for a unique kind of public urban space.

III | Formailties

"METRO, BOULOT, DODO"

[may

- tro - boo - lo - do - do]

Born out of the Paris 68' protests, "métro, boulot, dodo" is an phrase synonymous with civil unrest aimed at poor public environments in cities, The informal French expression is a colloquial way of saying that you 'live to work'. It emphasises the importance of quality public spaces that can help citizens to break the monotony of urban life. It is similar to the English phrases like 'the rat race' and 'work, work, work', but these phrases don't quite capture the same sense of constant movement as their French counterpart.

'Metro'-Raliways / Transit

'Bolout'-Work (informal)

'Dodo'-Sleep (baby talk for 'Sleep')

Developing a model for a new type of Public Space in South African Cities

Throughout history, people, cities and architecture have had a symbiotic relationship. People gathered and formed communities, who used architecture as a way to lay their claim on the earth (Ortman, Lobo & Smith, 2020). As societies grew and became more complex so did the urban environment, finally becoming the cities we know today.

Cities and their architecture have influenced cultures and social interactions by moulding physical space. if cities are understood as places of interaction, then public urban space is its most vital facilitator, serving as the melting pot of urban society (Buchanan, 2013). These spaces allow citizens to gather, interact and socialise in the city. They are important spaces that break the monotonous rhythm of urban life; transit, work, sleep, repeat. Great cities have been able to develop their own forms of desirable public urban spaces.

Modernist city planners used a 'Functional city' approach that separated urban functions and organised them into zones(Gold, 1998). These zones were then connected by transportation, with an emphasis on automobiles and railways. This way of creating cities has since led to highly disconnected urban environments (Levy, 1999). In South Africa, this was exacerbated by the apartheid regime, which used transport infrastructure, and other spatial elements, to intentionally racially segregate people. This has left South African cities with a plethora of barriers and buffer zones that form a highly disconnected urban landscape.

"Citiesaretheplaceswherepeople meettoexchangeideas,trade,or simplyrelaxandenjoythemselves. Acity’spublicdomain~itsstreets, squares,andparks~isthe stageandthe catalystforthese activities."

Richard Rogers in read (Gehl, 2010: IX).

This treatise deals with the development of a model for public urban space in South African cities. The model will transform these barriers and buffer zones from elements of disconnection, into vibrant urban connectors. To demonstrate the model, the principles will be implemented in the design of an urban park in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Johannesburg, the City of Gold, is a boomtown situated in the Gauteng Province. Dubbed ‘South Africa’s Manhattan’, it is a city that is fuelled by an extraordinary energy generated by its diverse citizens, complex urban landscape, and prospects of economic opportunity (Samin, 2009). At the heart of this sprawling metropolitan, is the historical Central Business District (CBD). The urban condition is generally poor, with inadequate service delivery, vehicle-centred streets and a lack of public space options. Despite this, the area is alive with people, taxis, and informal trade. Where the city has failed to provide adequate traditional public spaces types such as squares or plazas, the people have created their own in the streets. Bustling markets and rambunctious taxi ranks have become generators of this unique urbanity.

Urbanity, city space and place-making are at the core of this treatise. Understanding these concepts requires an exploration of urban theories and literature. Rem Koolhaas and his book Delirious NewYork(1978) provided a fundamental lens for understanding the architecture of a city. In particular, his theories of Manhattanism and The Social Condenser offered a unique insight into urban culture. In the book, the culture is generated by the relationship between the city, its people, and the architecture. Koolhaas was also interested in Japanese Metabolism, an established architectural movement with principles for the creation of an architecture in dense urban environments (Self, 2011). Metabolists had a particular interest in the adaptability and flexibility of architecture, one that can grow and diminish with the flux of the contemporary city (Tamari, 2014). Hedonistic Sustainability, Third Space Theory and Terrain Vague are also explored as tools for regenerating particular types of urban space.

Like a city system, one of organised chaos, the theoretical framework is a complex series of theories and ideas culminating in a coherent set of principles, for the redevelopment of unproductive and disconnected urban space.

Aims & Objectives

The treatise aims to design a recreational urban park in the Johannesburg CBD. The landscape will become a social condenser within the city, one that can grow, respond, and thrive within the flux of the urban landscape. The main objectives that this treatise will undertake are:

Developing a set of principles for a model, which can be used to regenerate urban spaces in South African cities.

Contextualising theories and research into a set of appropriate design drivers.

Understanding the complex nature of Johannesburg’s urban landscape by responding to the culture of the street.

Understanding the nature of adaptable and modular architectural construction techniques for flexible architecture.

Creating a landscape that embodies continuity and connectivity.

The implementation of active design principles into public urban space.

Structure

The document is comprised of two parts.

PartAhas four chapters. Chapter 1 is a literature review that provides the theoretical framework for the design. Chapter 2 deals with the nature of the context, culminating in a series of constraints and informants. Chapter 3 seeks to understand the nature of the building type through research and the study of precedents. Chapter 4 contains the principles exploration of theories that are discussed in Chapters 1 through 3.

PartBhas three chapters. Chapter 5 & 6 contain elements from the design development such as the brief, model explorations, sketches, and diagrams. Chapter 7 contains the final design, including plans, sections, elevations, and renders. Finally chapter 8 includes all the sources of information used in the treatise. The Structure allows the document to flow from chapter to chapter, developing the argument ,ultimately acting as one coherent body of work.

Methodology

“Whatisveryimportantistodistinguishtwotypesofwriting: onethatIwouldcallwritingaboutarchitectureandonethatI wouldcallwritingofarchitecture.Writingaboutarchitectureis themostcommon…thetextsaregenerallydescriptive…butin themselvestheyarenotarchitecture…since1968,anumberof textswerewrittenthatarearchitecture…Theyarearchitectures inthemselves.Inotherwords,theyproposeformsofarchitectural strategies,literallyintheformofasubstitute”

Bernard Tchumi (Cerra, n.d.)Aresearch methodology outlines the overall strategy for the undertaking of academic research. It serves to show an understanding of the research process, thus providing the body of work with a level of reliability and validity in the field of academia (Crossley, 2021).

This project deals with a public urban architectural design in Johannesburg CBD, South Africa. The aim of the project is to establish a set of principles for an architectural model for public urban spaces in South African cities. These principles are generated from the analysis and interpretation of architectural theory, precedent, and the existing context in order to create the model. Architects and urban planners often deal with the topic of public urban space, this treatise aims to add value to these ongoing conversations and generate a useful tool for designers.

I believe that architecture is a creative science. It deals with contrasting fields such as engineering, construction, art, and philosophy, to name a few. Design processes can take on statistics, surveys, and other forms of data rooted it in the real world, while other design processes take on a more philosophical and phenomenological approach that deals with creative interpretation, human experience, and metaphorical representation of concepts. These philosophies and processes are used to generate a final physical product. It is important that the research philosophy reflects that of the design philosophy in order to create a coherent body of work.

The process of architectural design normally follows an applied research strategy due to the development of a physical product but, as I am a student, the treatise forms part of pure or basic research, resting in academia, used only to further develop architectural thinking within particular areas of the discourse (Britannica, 2021).

Within research there are four main philosophies, namely : Realism, Positivism, Interpretivism Pragmatism.

Realism is rooted in research that is outside of the human experience, often used in science. Positivism deals with knowledge gained and interpreted objectively through the analysis and production of data sets, using quantitative research methods and statistical analysis. This method allows for reading and capturing of data observed from the real world, without subjective interpretation. Interpretivism opposes the positivist philosophy, integrating the human element into the interpretation of research data, allowing for subjectivity. This philosophy therefore utilises qualitative methods over quantitative, allowing for the exploration of concepts and experience in more depth (Dudovskiy, 2011).

Pragmatists believe that there are multiple ways to interpret the world and research, allowing for a broader understanding of the problem being investigated. This philosophy allows researchers to apply mixed methods in order to resolve different questions, rather than the mutually exclusive methods of the positivist and interpretivist philosophies (Dudovskiy, 2011).

In an ideal setting the design research would involve a pragmatic mixed methods approach. However, due to the limitations of being a student in architectural education, the research will all be qualitative in nature.

This treatise, therefore, follows an interpretivist philosophy, incorporating interpretative research methods. It uses a deductive research analysis of information from books, websites, and architectural media to create a set of design drivers usedin the design and production stages of the project. The research process utilises established theories, and information to formulate novel solutions to existing problems, as opposed to trying to formulate a new theory from the research (Dudovskiy, 2011).

Through the application of this methodical research structure, I hope to create a valuable and coherent argument with the research producing a series of design informants that can be used to develop the final architectural product. My aim is not to give an absolute response to the problems outlined but to create a valuable conversation that can add to a wider public argument on the development of a unique public space for South African cities.

Figure 7. Figure Methods, Strategies, Philosophies for Research Methodologies (Dudovskiy, J. 2011)

Figure 7. Figure Methods, Strategies, Philosophies for Research Methodologies (Dudovskiy, J. 2011)

A.

Research & Analysis

CHAPTER 1: Literature Review

CHAPTER 2: Nature of the context

CHAPTER 3: Nature of the Archetype

CHAPTER 4: Principle Exploration

A

The literature review aims to show an understanding of existing knowledge and theories, providing the design with a base from which to establish its position within the discourse (Jansen & Warren, 2020). In this chapter, I will explore a set of theories, movements, and philosophies in architecture, endeavouring to gain an understanding of how they grappled with different challenges in society.

This treatise was inspired by Delirious New York (1978), a book written by Rem Koolhaas. It was here that the treatise became about understanding the inner workings of dense urban environments. Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) was established by Koolhaas in 1975 as a collective that is concerned with the urban condition. Their designs were centred on the production of fields for social encounters. They focused on flexible responses that can change and adapt to the present moment, responding to the specific needs of the client and context without enforcing preconceived ideologies of form. (Yaneva, 2010).

Further exploration of other theories and philosphies led to architectural movemnets that dealt with the theme of the urban condition. Most notably was the exploration of two movements from the 1960s; Japanese Metabolism and Archigram. Both sought to provide models for means to inhabit dense urban environments (Garcia, 2015). These movements share similarities, but Metabolism was of particular interest for Koolhaas, going on to influence areas of his thinking and aid in the generation of his architectural visions.

Understanding these movements, and philosophies will provide a toolset used in this treatise to develop a model for the regeneration of public urban space in South African cities.

Establishing pragmatic-urbanmetabolism as a tool to generate desirable public environments within a city's 'left-over' spaces.

"A Pragmatist, A Metabolist and

Philosopher walk into a bar..."

Figure 9. 'Architects atop a Skyscraper' (by author) 10

Figure 9. 'Architects atop a Skyscraper' (by author) 10

This chapter is written in the same format as DeliriousNewYork(1978). This structure allowed Koolhaas to emphasise contrasting or related topics, while still providing a coherent narrative. It reads much like a city. The reader explores the city blocks, streets lined with a collection of themes, curiosity leading them to an understanding of urbanity.

Figure 11. Image by author of DeliriousNewYorkcover(OMA website, n.d)

Figure 11. Image by author of DeliriousNewYorkcover(OMA website, n.d)

“…intermsofstructure,thisbookisasimulacrumofManhattan’sgrid:acollectionofblockswhoseproximityandjuxtaposition reinforcetheirseparatemeanings”

(Koolhaas, 1994 : 11).

Koolhaasianism

Considered by many as the mastermind of the Dutch Pragmatist movement, Rem Koolhaas has developed a multitude of theories and design processes that pertain to the urban condition. He has been able to implement these through the OMA, which has influenced some of the most prominent architects today, such as; Bjarke Ingels, Winy Maas and Zaha Hadid (Gupta, 2018). Architectural theorist Sandford Kwinter would critique poor reproductions of Koolhaas’s theories, labelling them “Ill digested Koolhaasianism”, indirectly commenting on the immense influence these theories had on architecture at the time. (Mallgrave & Goodman, 2011). Koolhaas’s polemic persona and his critical thinking are a large part of his success in the world of architecture, actively challenging the modernist ideologies of aesthetics, in favour of an open and unbiased design process.

Koolhaas began his career in journalism and movie script writing which served as a fundamental tool in developing his architectural process. He saw writing as a tool for thinking about architecture, without prescribing form or aesthetics.

Here architecture became a tool for the division of people, disabling their transition from the ‘bad side’ to the ‘good side’. Through the thesis, he was able to design architecture in the same mode, but instead of generating division, the ‘wall’ became a set of layered recreational urban activities within a large strip of central London. Citizens would become voluntary prisoners of this wall (Cerra, n.d.). The thesis became the catalyst for him to embark on his journey to understand urban environments, uncovering their driving forces while enabling the development of his theoretical ideas. (see Cahpter 4 pg for reference to ‘Exodus’)

Manhattanism

Koolhaas’s Delirious New York (1978) was a retroactive manifesto for the early development of New York City. The previous modernist way of planning involved writing manifestos that informed new urban conditions, but in Manhattan, the architects had improvised spatial conditions faster than they had time to validate them. (Cerra, n.d.) This meant Koolhaas could both describe the city and prescribe it. The manifesto established a polemic architectural text, in a tone of fascination and admiration, for the city that would become fundamental in the development of his design dogma.

Edward Soja (2014), reflecting on his theory of the Third, stated, “Rather than an actual force in the shaping of society and theory, space became a reflective mirror of societal modernization.” However, this can be used as a way of understanding the phenomena of Manhattanism.

Going on to write a plethora of journals and books, Koolhaas was able to establish his ways of thinking about culture, space, and design in the urban environment, without building anything. In 1971, his obsession with cities became apparent, with the publishing of his final project at the Architecture Association (AA), titled Exodus. The thesis explored the idea of architecture as a tool for controlling or influencing space, with the Berlin Wall as its muse.

Through exploring the history of Manhattan and engaging with many of the designers of the time, Koolhaas was able to piece together his version of Manhattans development, focusing on architecture’s role in the generation of a culture, and vice versa (Koolhaas, 1994). Through this process of discovery, he would go on to establish Manhattanism as the unformulated urban movement that shaped New York City. This theory set up a way of understanding the metropolitan condition and led him to further explore how architecture can be a tool for the generation of vibrant urban space. For Koolhaas, architecture was a catalyst of the ‘event’, facilitating the major socio-cultural activities within the city.

Figure 12. figure : ‘KOOLAGE’ (by author) embedded portrait of Rem Koolhaas by Stefan Vanfleteren“Maybe,architecturedoesn’thave tobestupidafterall.Liberated fromtheobligationtoconstruct, itcanbecomeawayofthinking aboutanything-adisciplinethat representsrelationships,proportions,connections,effects,the diagramofeverything”

(Koolhaas in Cerra, n.d.).

...Emergingfromtheelevatorontheninthfloor, thevisitorfindshimselfinadarkvestibulethat leadsdirectlyintoalockerroomthatoccupiesthe centreoftheplatform,wherethereisnodaylight.

Thereheundresses,putsonboxinggloves andentersanadjoiningspaceequippedwitha multitudeofpunchingbags(occasionallyhemay evenconfrontahumanopponent),Onthesouthern side,thesamelockerroomisalsoservicedbyan oysterbarwithaviewovertheHudsonRiver.

Eatingoysterswithboxinggloves,naked,onthe ninthfloor–suchisthe‘plot’oftheninthstorey,or the20thcenturyinaction.”

(koolhaas, 1994 :155)

(koolhaas, 1994 :155)

Skyward

One of Manhattan’s manifestations was the Downtown Athletics Club. The skyscraper would offer an uncanny example of Manhattanism at work. The 38-floor mixed-use building provided an image of what the culture had produced, each floor a new and undiscovered reality. The elevator is the only medium for connection to the seemingly endless supply of programmatic possibilities.

The ninth floor shows how this type of architecture allows the imagination to create its reality from a strategy of mixing uses. This provided two particular discoveries for Koolhaas.

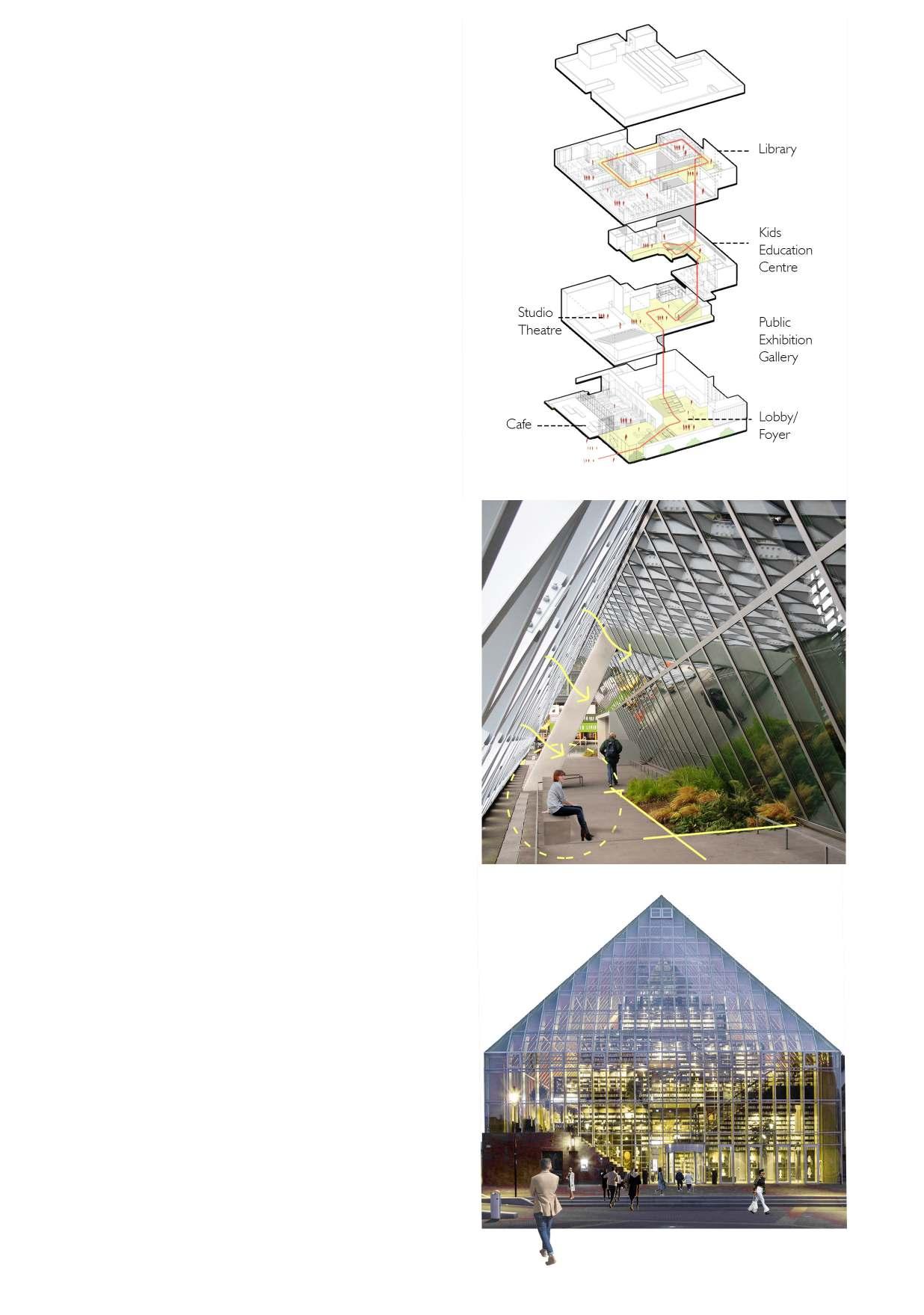

Vertically stacked elements in the form of a skyscraper would inevitably create disconnected space. It was this that encouraged him to develop theories and models for a way to create a vertically connected space (Garcia, 2015). He would eventually implement his solution through the design of OMA’s Seattle Public Library, which showed that by using a series of ramps and manipulated floor planes, one could create a continuous landscape, imbuing a sense of connectivity and continuity in the space.

Downtown Athletics Club inspired his philosophy of creating ‘the Event’ through the use of highly diverse programming, linking both physically and visually to the urban environment (Dovey & Dickson, 2002). .

This ‘Cross-programming’ technique has been used by Koolhaas, and his fellow pragmatists, with the intention of creating vibrancy and interest for the people that utilise the architecture.

Figure 14. figure : Plan And section of Downtown Athletics Club (koolhaas, 1994 : 155)16Big Soft Orange

Pragmatists in architecture can be defined by their analysis and interpretation of relevant data into drivers, their response to the requirements of the client and context, as well as the creation of ribbons of programme (Mallgrave & Goodman, 2011). This is a move away from theoretical ideals to a more exuberant and playful design thinking that comes from the diagrammatic abstraction of information into an informant, and sometimes even into literal formal expression.

Cities offered pragmatists a number of constraints and informants to analyse and respond to, exploiting the urban forces and flows to create their architectural projects. By utilising a toolbox of maximum flexibility and general freedom from predetermined ideals, they were able to generate new ways of experiencing urban space (Mallgrave & Goodman, 2011). This allowed them to succeed internationally, creating architecture that responded to its particular social, cultural, and political environment.

In 1999, architect, Michael Speaks, criticised the pragmatist’s adaptability by labelling them the ‘Big Soft Orange’ (Mallgrave & Goodman, 2011). This was a name given to the many Dutch firms willing to take on any, and all, large architectural projects. Pragmatists, however, regard this flexibility as a strength, advocating for architecture as a reactive endeavour.

Generic

Modernisation and globalisation have challenged the rigid characteristics of the classical city, leading to a more flexible and adaptive urban condition. The generic city is a concept, theorised by Koolhaas, that advocates for the advantages of ‘blankness’, to shy away from strong, rigid elements and styles for a city’s architecture. Koolhaas makes the argument that perhaps in the absence of a style or identity, it could allow for an easier expansion, reinterpretation, and renewal of a city over time (Akcan, 2008).

He advocates for flexibility and adaptability in design, allowing the ‘poetic mutations’ of the city to exist. In this model, the architecture facilitates the vibrant culture of the people. It is the culture of urbanity that provides the richness of identity in contemporary cities, rather than imposing it through architectural interventions. Elements of this theory resonate with earlier movements that offered models for flexible architectural strategies.

Plug ‘n Play

At the beginning of the 1960s, five architects banded together to form the Avant-Garde movement, Archigram. These architects rebelled against the mainstream architecture of the times in favour of amusement, technological innovation, and the human experience (Pickering, 2006).

Artistic collages and pop culture references helped them to express their vision of the future in a whimsical but unique way. Among the over nine hundred illustrations and drawings, The Plug-in City was a techno-utopian model that visualised a future where technological innovation was exploited to generate megastructures, made up of interchangeable parts with links to mass transport systems (McAndrew, 2019). This was a response to the rapid flux of cities of the time. By generating customisable urban lifestyles for citizens, the megastructure could expand, adapt, and change with the flux of the urban environment. The model provides ways of thinking about the architecture in cities which are of the culture, flexible in its construction and vibrant in its aesthetics.

“Itiseasy.Itdoesnotneedmaintenance.Ifitgetstoosmallitjustexpands.Ifitgetstooolditjustself-destructsandrenews.Itisequally exciting-orunexciting-everywhere.

ItisSuperficial-likeaHollywood studiolot,itcanproduceanewidentityeveryMondaymorning.”

(Koolhaas, Mau, Sigler & Werlemann, 1998: 1250).

Metabolism

Also born out of the 1960s, Metabolism would become what Koolhaas regards as the first non-western Avant Garde movement. Conceived in Japan, by architect Kenzo Tange, it brought together Japanese students and architects to see its conception. The movement, while a search for identity in Japanese architecture, was a response to catastrophic events, including World War Two and subsequent natural disasters, that led to the destruction of parts of Japanese cities. Tange wanted to create architecture that could be the face of a new and prosperous Japan (Tamari, 2014).

Embedded in biology, the movement was rooted in the idea that cities and architecture could emulate organic processes (De Oliveira, 2011). Much like an organism, the architecture would respond to its environment and to the passing of time, developing resilience or succumbing to the pressures of the urban condition.

It was the biological abstraction and inherent cultural philosophies that helped to develop the model that could regenerate and rebuild their cities. Driven by

a period of impermanence and uncertainty, themes of modularity, adaptability and expandability would characterise their designs. These would allow their architectural ‘organisms’ to be in a perpetual state of growing and mutating, withering, and regenerating.

Utopias

One can understand that after catastrophic events, there would be a yearning for a utopian future, and in a sense, optimism as dogma. The Metabolists were convinced that their architecture would influence a new-and-improved socio-urban fabric, fixated on the viability of centralised organisms, and fully integrated systems (Tamari, 2014). They paradoxically wanted to increase autonomy by designing highly functional and rigid systems, manifesting as a form of socialist architecture; a way to control society’s movement and interactions. Unfortunately, the urge to plan whole cities and megastructures, coupled with economic collapse, ultimately saw an end to the movement. However, the Metabolist’s principles of adaptability and flexibility live on through their influence on architectural pedagogy.

“Onceyou’reinterestedinhowthingsevolve,youhaveakindof never-endingperspective,becauseitmeansyou’reinterestedin articulatingtheevolution.”

Rem Koolhaas tweet. (Self, 2011)Figure 16. ‘Capsule tower poster collage’ (Author, 2022) embedded poster by Kisho Kurokawa 1972. Figure 17. Kenzo Tange & "Cities in the Air" model by Arata Isozaki (by author) 20

Condensation

Using architecture to influence socio-behavioural systems in cities, was not a new idea. In 1917, after the Great October Socialist Revolution, the social condenser was an architectural strategy for propagating new ways of interacting under the socialist regime (Murawski, 2017).

The social condenser was used to make the new socialist ideals appealing to the masses. It integrated housing schemes, work, and public cultural activities into combinations never seen pre-revolution. The social condenser would be a tool to generate new kinds of social interactions. Koolhaas has since appropriated this strategy, going as far as to patent it, along with a series of other models, in the Universal Modernization Patent (Koolhaas, 2004). The social condenser reinforced his theory that diverse programmatic combinations could generate desirable social interactions. It would become Koolhaas’s tool for a type of programmatic placemaking, a method to provide vibrant social spaces that serve social sustainability.

Hedonism

In Delirious New York, Koolhaas explores moments of architectural hedonism; interventions with the sole purpose to provide vibrant social spaces for the entertainment of the citizens. In recent years Bjarke Ingles has coined the term Hedonistic Sustainability. This is a design philosophy that responds to the need for creating spaces for play, leisure, and interaction. It insists that architecture can be both human-centred and maintain ecological efficiency (Estika, Kusuma, Prameswari & Sudradjat, 2020). This is a ‘both-and’ mindset that puts holistic wellness at the centre of the design. This philosophy encourages thinking in terms of architecture influencing the wellness of both social space as well as physical space and as a tool for the regeneration of urban environments.

Wellness

Architecture has a clear influence on society with regard to physical wellness. Studies show that it takes as little as 30 minutes of daily moderate aerobic exercise to see benefits such as increased brain function, increased longevity, weight management, reduced depression and anxiety, improved sleep (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2016). The importance of physical activity has grown in popularity in recent years as people have become more aware of the negative impact of our increasingly sedentary urban lifestyles. There is a need to look to design strategies that help to integrate more movement into our daily lives.

Active Cities is a planning strategy promoting active leisure, diverse movement types and social inclusion within cities (Sallis, et.al. 2015). The strategy utilises active design principles to inspire movement through opportunities for passive and active forms of physical activity. Well-designed circulation can promote walkability, bikeability, and visibility, thus generating a connected landscape with a diverse range of physical activities.

Active design can generate spaces filled with human activity working as a tool for injecting vibrancy into public spaces. Active landscapes, like urban parks, provide people with opportunities to play, rest, and socialise. In the book, The Great Good Place (2005), Ray Oldenburg expresses the fundamental role of these places in the generation of healthy social spaces. His Third Place Theory promotes the integration of recreational public places between work and home where people gather to feel a sense of inclusion.

Third

The idea of the third space is found throughout philosophy. It is used to describe an ‘other-ness’ or a ‘between-ness’. Edward Soja uses Henri Lefebvre’s concept of trialectic reasoning as the base for his Third Space Theory. Simplified, the theory articulates how people exist in socially produced spaces.

He describes three elements that make up space. The first space is physical space; the urban built environment as a measurable landscape. The second space is the representational space; it lives in our

minds and relates to how people perceive space. The third space is a combination of real and imagined space and is a fully lived space. The third space is the human experience of the first space, mediated through the lens of second space expectations (Soja, 2014).

According to Lefebvre, this is the socially constructed space that the people hold in their collective memories. This space becomes important in understanding human interactions in society.

andtheunimaginable,therepetitiveandthedifferential,structure andagency,mindandbody,consciousnessandtheunconscious,the disciplinedandthetransdisciplinary,everydaylifeandunending

Figure 19. Henri Lefebvres 'trialectics of space' model (by author)“Everything comes together… subjectivity and objectivity, the abstractandtheconcrete,therealandtheimagined,theknowable

history.”

(Soja,2014).

Vague

Urban environments can contain an element of third space. Ignasi de Solà-Morales, also influenced by the teachings of Lefebvre, classifies these spaces as Terrain Vague. His term is given to islands of unproductive space in a city that are void of any activity due to the consequential nature of their creation, like ‘knitting with imperfections’ (De Solà-Morales, 1995). It encompasses the leftover spaces that are either irregular, hard to reach, or undesirable. These spaces can include parking lots, traffic islands, railway infrastructure and highway overpasses. Terrain Vague speaks to the provocative nature of these spaces. He suggests that these spaces imbue a sense of mobility and freedom in their blankness or placelessness.

The indefinite and uncertain nature of these spaces is not seen as solely negative. De Solà-Morales believes that they present an opportunity for desirable forms of internal expansion. He sees the evocative potential in unused islands of space and in weaving them back into the tapestry of the city. If these unproductive zones are understood in this nature, terrain vague can become a unique urban strategy for creating a sense of connectedness in otherwise disconnected urban landscapes.

Establishing Principles for a Pragmatic-Urban-Metabolism

DeliriousNewYorkoffers an insight into a world of architectural hedonism, with experiential realities created to serve the culture of the people. While some might see the negative effects of congestion, density, and the urban condition, Koolhaas expresses its poetic essence. It is an urban space that is bursting with diversity and delight around every corner. It is a lens that frames the generation of urban architecture rooted in urbanity.

This chapter has informed the development of pragmatic-urban-metabolism, a package of eight principles that can aid in the regeneration of urban spaces in South African cities. These principles will be used to convert third space into a vibrant third place:

Flexibility of the design will be crucial to dealing with the flux of the urban environment. Flexibility in spaces and structure will ensure the longevity of the intervention as it responds to the needs of the context.

Adaptability can be achieved through the use of modular elements and construction techniques that will allow the intervention to grow and wither over time.

Programmatic diversity is essential to generate vibrant social spaces and accommodate a diverse range of people.

Verticality to increase the overall density while maintaining Connectivity and Continuity of space.

Active Design principles will be utilised, ensuring physical wellness for the users.

Terrain Vague offers a lens for discovering sites; Third spaces that can be used to facilitate this type of intervention.

Figure 21. ‘Delirious Johannesburg’ ( by author) Edit of photo by Henni Stander

Figure 21. ‘Delirious Johannesburg’ ( by author) Edit of photo by Henni Stander

Delirious Johannesburg

The treatise aims to develop a model for public urban space in South African cities. The model will be used to reactivate unproductive and derelict spaces within the urban environment.

Chapter 2 uses the themes from the literature review as a lens through which to analyse the nature of the context. It investigates elements of social, cultural, and environmental structures in and around the project’s location. This analysis takes the form of mapping, tracing and photographic studies that help to fully understand the site and its informants.

The city of Johannesburg has been chosen as the test bed for the model. This chapter investigates the metropolitan condition, prospecting for energies, and searching for barriers. Third space and terrain vague help to determine sites with the potential for regeneration. It is important to understand the nature of the social fabric, structuring elements, and programmatic potentials in order to generate a set of constraints and informants that inform a holistic intervention.

“ Certainlythecityisaplaceof tradeandmanufacture,residenceand recreation,educationandwelfare. Butthequintessentialandmost elevatedpurposeofthe cityisasthecrucibleinwhich culture,creativityandconsciousness continuallyevolve.

- ‘The Big Rethink’ (Buchanan, 2012)

A Culture of Flux

Understanding the nature of the modern urban societies.

The Culture of Congestion represents how architecture has been able to influence urban culture and the role that citizens played in the success of those interventions (Koolhaas, 1994). The architecture was the proponent of the event, often momentarily successful, but inevitably losing the interest of people as they looked to satisfy their desire for new and exciting activities. This led to many structures becoming obsolete within a few years.

Modernist urban planners sought to implement their preconceived ideologies of order and control on the chaos of the urban environment (Levy, 1999). The metropolitan condition is complex and contradictory. It is an unstable force that cannot be controlled, only facilitated. It is an organism in a constant state of flux. Rem Koolhaas advocates for the creation of resilience through understanding this ever-changing, ever-growing and ever-mutating nature of the modern city (Koolhaas, Mau, Sigler & Werlemann, 1998). He asserts that the moment one seeks to concretize the present, one becomes irrelevant, lost in the fleeting nature of the urban

procession. Planning should always happen with the future in mind and with designs that can respond to the flux of the urban condition. There is a need for the role of planners and designers to be reconsidered, not as dictators of urban structures, but rather as facilitators of its forces and flows. The Metabolists offered theories for resilient urbanism, one that accepted growth, destruction, and renewal in all aspects of life (Schalk, 2014). It is an ideology that embodies flexibility in the generation of new systems, being able to respond to the flux of the urban environment and always striving for balance.

Rapid urbanisation has caused cities to develop from skyscrapers to urban sprawl, changing from hyper-density to rambling suburbia. This has occurred through the integration of the automobile into modernist planning strategies. This union has led to urban decentralisation and a low-density urban sprawl that rips the energy from a city’s core (Park & Andrews, 2004). In recent years, sustainable development models have focused on the regeneration of these city centres, a return to density, and a form of inward expansion.

Urbanismwillneveragainbeaboutthe ‘new’,onlyaboutthe‘moreandthe‘modified’.Itwillnotbeaboutthecivilized,but abouttheunderdeveloped.Sinceitisout ofcontrol,theurbanisabouttobecome amajorvectorofimagination.Redefined, urbanismwillnotonly,ormostlybeaprofession,butawayofthinking,anideology:toacceptwhatexists.Weweremaking sandcastles.Nowweswimintheseethat sweptthemaway.

What ever happened to urbanism’(Koolhaas, Mau, Sigler, Werlemann, 1998).

The South African urban landscape

Cultural geographer, Philippe Gervais Lambony has stated, “The urban landscapes of South African cities are significantly readable”, (Samin, 2009). It gives a strikingly poignant statement about the generic structure of the South African city. Original urban planning in South Africa was used as a tool for control. Influenced by the modernist urban planners, the apartheid government imposed racially motivated structural segregation. Industrial infrastructure and land barriers were typical elements used to segregate communities of People of Colour (POC) from white communities. Almost 30 years post-apartheid, through inevitable and much needed reform, these planning strategies are no longer in effect, yet, the echoing outcomes of the apartheid-era planning are still considerably noticeable in the layout of cities, with a social hierarchy still based almost solely on racial differences and economic inequalities.

With South African cities still imbuing a sense of division, designers are left to pick up the pieces, dealing with disconnected urban environments, derelict public infrastructure, and poor public spaces. If the ‘rainbow nation’ is to prosper, division needs to be eradicated through the creation of connected urban organisms, and a collective South Africa.

“ This way I salute you:/My hand pulses to my back trousers pocket/ Orintomyinnerjacketpocket/For mypass,mylife…/Itravelonyour blackandwhiteandrobottedroads, /Throughyourthickironbreaththat youinhale/Atsixinthemorningand exhalefromfivenoon…” (Serote, 2002: 4).

Noun. [ bar·ri·er ]

1 : something that blocks the way.

2 : something that keeps apart or Makes Progress Difficult.

White. Developed. Suburbia.

People of colour. Underdeveloped. Informal settlement.

Road Infrastructure. Open space. Coarse grain plots. Low density.

Minimal open space. Fine grain plots. High density.

Land buffer

"BARRIER" Railway or IDZ

Noun. [ bar·ri·er ]

1 : something that blocks the way.

2 : something that keeps apart or Makes Progress Difficult.

White. Developed. Suburbia.

People of colour. Underdeveloped. Informal settlement.

Road Infrastructure. Open space. Coarse grain plots. Low density.

Minimal open space. Fine grain plots. High density.

Land buffer

"BARRIER" Railway or IDZ

MIDDLE CLASS

UNDERPRIVILEGED

WORKING CLASS

UNDERPRIVILEGED

MIDDLE CLASS

UNDERPRIVILEGED

MIDDLE CLASS

MIDDLE CLASS

UNDERPRIVILEGED

MIDDLE CLASS

MIDDLE CLASS

UNDERPRIVILEGED

VIGOROUS, CRUDE AND BRAWLING, FILLED WITH THE INSISTENT PULSE OF LIFE”

– Is how Allen Drury describes Johannesburg in his book A VeryStrangeSociety:A JourneytotheHeartofSouthAfrica(Drury, 1967 :181)

Johannesburg has grown into a metropolis. A boomtown, conceived at the end of the 19th century through the discovery of gold deposits in the Witwatersrand, the city was quickly flooded by prospectors, causing it to grow at an unprecedented rate in the South African context. To adapt to the growing activity, city planners quickly laid down rigid grid systems to achieve maximum capital gain, selling off plots of land to a multitude of acquisitive companies and tycoons. In this whirlwind of development, the CBD became the core from which the city grew. The CBD ushered in banks, mining company headquarters and eventually the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. The face of the city quickly went from quaint Edwardian aesthetics to vertically extruding Art Deco towers. Referred to as South Africa’s Manhattan, the architecture would start emulating that of New York’s metropolis, even going as far as to borrow the names of its buildings, such as the Chrysler House and Astor Mansions. During the 1950s, the skyscraper would become the means by which the city showed its dominance, with more than fifty being built in just over a decade (Murray, 2011).

The Ring Road is a highway system constructed to facilitate connectivity in and around the metropolis. It subsequently induced an urban sprawl that saw the decentralisation of the city’s core. The collapse coincided with the abolishment of apartheid, and consequently, the Group Areas Act, which saw a flood of POC to the CBD, in search of economic empowerment. The corporate vitality in the CBD

would be short-lived as the urban landscape was quickly reconstituted into a forest of residential towers. This led to the generation of elements like overcrowding, informal and illegal trade, and crime (Sudjic, 2006).

Without major reconstruction, the new social class was expected to thrive in a sterile and neglected public space. This produced resilience within the people who were forced to be adaptable and responsive to rapid change.

Writing Johannesburg: from the labyrinth to the map is a journal that analyses stories produced in South African novels, narrating on the complexity of reading the Johannesburg urban landscape. It suggests a dichotomous relationship between the map and the experience on street level (Samin, 2009). For planners and architects, the position above the clouds allows for the reading of a particular urban condition of order and connectedness. Conversely, the experience of place and memory is fundamentally different. The pedestrian sees the city for what it is, a labyrinth or a maze that was not designed at eye level but from an eye in the sky.

“BIG,

The model seeks out dense urban environments, places that are able to provide fuel for the urban generator.

It is Here that the social condenser can be established, feeding off of the energies, generating connections and creating positive urban space for the city of Johannesburg.

JOHANNESBURGJOBURGJOZITHE CITY OF GOLD

Locating the model within Johannesburg Metro

The urban condition that has been conceived is admittedly flawed, much like the development of South Africa. There is a need for some level of acceptance of the current state of our urban environments. From this rises a challenge for all designers, to develop a unique spatial response for a diverse urban community. This can be achieved through the exploitation of the city’s culture and its forces and flows. In the absence of adequate public urban space to support the congestion, people take to the streets to meet, trade, and socialise. This, along with particular modes of transportation, has led to a vibrant and bustling street culture. The system is imperfect, the socio-cultural condition tattered and torn, but the people have been able to generate their own space.

Figure 32. 'Railway as a barrier' through Central Johannesburg (by author)

Figure 32. 'Railway as a barrier' through Central Johannesburg (by author)

“... a quality of form, of architectural form, of urban form, something essentially material, yet naturally affecting, reverberating uponthebehaviourandwellbeingofpeople,whenimmersedinthe publicspace.”

(Vieira de Aguiar, 2013)

PROSPECTING FORENERGY

Density Data from the 2011 Census along with activity data generated extracted from Google maps (AfriGIS, 2022) established high usage areas. Much of these areas were focused around the Commercial and transport activities with secondary areas being cultural, residential and recreational activities. Energy is

distributed centrally around Park station. This area is home to markets, retail and taxi infrastructure.

The sunken railway infrastructure creates a ‘Dead zone’ through the center, void of human activity. This infrastructure breaks the flow of energy between the suburbs.

Central Johannesburg is a web of Transportation, with infrastructure at every scale;

The Railway and Newly established Johannesburg international transport interchange services greater Joburg and beyond.

Rea Vaya is the BRT system for the city, with stops and Stations scattered throughout.

The M1 Runs through the South western edge of the area.

Marshalltown and Park Station precinct facilitates Taxi ranks with MTN Noord being one of the largest in the country. The Taxi infrastructure forms the primary movement system for inner city inhabitants.

The northern suburbs of Parktown and Braamfontein contain large amounts of greenery and vegetation compared to the city centre. As you move southerly towards the mining belt it becomes increasingly sparse, seemly chopped off by the railway infrastructure.

The city centre has a plethora of green parks, but due to their lack of integrated activities, find themselves poorly maintained and often occupied by the homeless community. These recreational landscapes have become highly unsafe and derelict environments. With-in the centre there are 2 prominent urban parks; Joubert park and End Street North Park. They are close in proximity, but have no obvious connection. There is a possible opportunity to manage a connection within the intervention to create a better-connected green system.

Figure 35. 'Green System' : Central Johannesburg (by author)

Figure 36. 'Movement Networks' : Central Johannesburg (by author)

Movement networks

Figure 35. 'Green System' : Central Johannesburg (by author)

Figure 36. 'Movement Networks' : Central Johannesburg (by author)

Movement networks

‘Third places’ can be churches, coffee shops, gyms, hair salons, post offices, main streets, bars, beer gardens, bookstores, parks, community centers, and gift shops ~ inexpensive places where people come together and life happens. In other words, they’re a community’s living room.

(Oldenburg, R. 2005.)

Discovering Energy in the Park Station Precinct

Tracings of the urban environment offer an insight into the nature of the urbanity. They explore the urban landscape, looking to understand where the energies are, where the connections might be, and where the intervention can facilitate these connections. The Social condenser seeks out Terrain vague, for barriers in the minds and lives of the city dweller. It is Here that the design can begin to grow, fueled by the energy of the city, manifesting vibrant public urban space.

Terrain vague provides the lens for seeing the unrealised potential of this sunken railway infrastructure. An element of division in the centre of city life, re imagined from a space-separator into a space-connector. A new productive landscape that generates connections, social interaction, and recreational activities. A new type of public space in the city.

A Situationists guide to the CBD

The 'Situationists'werea collective of artists, philosophers and writers that rebelled again modern society. They believed that mass media was negatively influencing social space, making people socially distant and apathetic towards public space.

'Psychogeography' is a method of representing city space, through drifting and playfulness, it seeks to develop a social geography of cities (Sadler, S. 1999). The Situationist was fascinated by people-driven places, the ambiance of socially active buildings and spaces that made people stop and take a moment.

This style of mapping focuses on the experience of the pedestrian, wandering the streets, using landmarks and thoroughfares to make their way to their destination. It offers a different perspective of cities, one that diagrams relationships to places through the eyes of the urban nomad.

DEVIANT

VIBRANT

Flaneur

Noun · [fla - ner] · French

Flaneur refers to an individual that strolls the city in order to experience it, deliberately wandering in in search of the essence of urbanity (Siu, 2012). This method of representation seeks to understand the urban condition from the eyes of the pedestrian. Understanding the good and the bad aspects of what makes the city’s spaces unique.

Searching for terrain vague leads the design to the railways system. Can this infrastructure be re-imagined into a connected landscape?

Terrain Vague

The Energy of the street is concentrated to the banks of the sunken railway. Taxi ranks, street markets and other recreational activities line its edges, a potentially viable public space in the sky?

Figure 43. Figure : 'Third Space' in the Park station precinct (by author)

Figure 44. 'Urban Energies' : Park station precinct (by author)

Figure 43. Figure : 'Third Space' in the Park station precinct (by author)

Figure 44. 'Urban Energies' : Park station precinct (by author)

In the CBD, the energy of the street is generated from two primary sources, public transport and informal trade. The minibus taxi, a rapid mode of transport with little regulation has stepped in to facilitate the congestion (Murray, 2011). This form of transport, while unpredictable and sometimes flawed, is a highly efficient way for citizens to reach their day-to-day activities. Taxi ranks have become high activity nodes for the city. Emanating from these zones, vendors, clothes merchants and hawkers feed off the radiating foot traffic.

In the early development of Johannesburg, the main railway, Park Station, served as a crucial connector for the people both locally and regionally. It has since fallen into disrepair, becoming derelict through poor maintenance and vandalism (Zack, 2017).

While it is still well positioned to maintain its status as a major connector within the system, its physical nature is perceived differently by someone on the street. Like a scar on the landscape, the railway line becomes an element of division.

The sunken infrastructure divides various communities within the city’s core, with Braamfontein housing the university of Witwatersrand, which offers a vibrant student life, Hillbrow, an adjacent residential community, Newtown with cultural facilities, and Marshalltown, a platform for transport and trade.

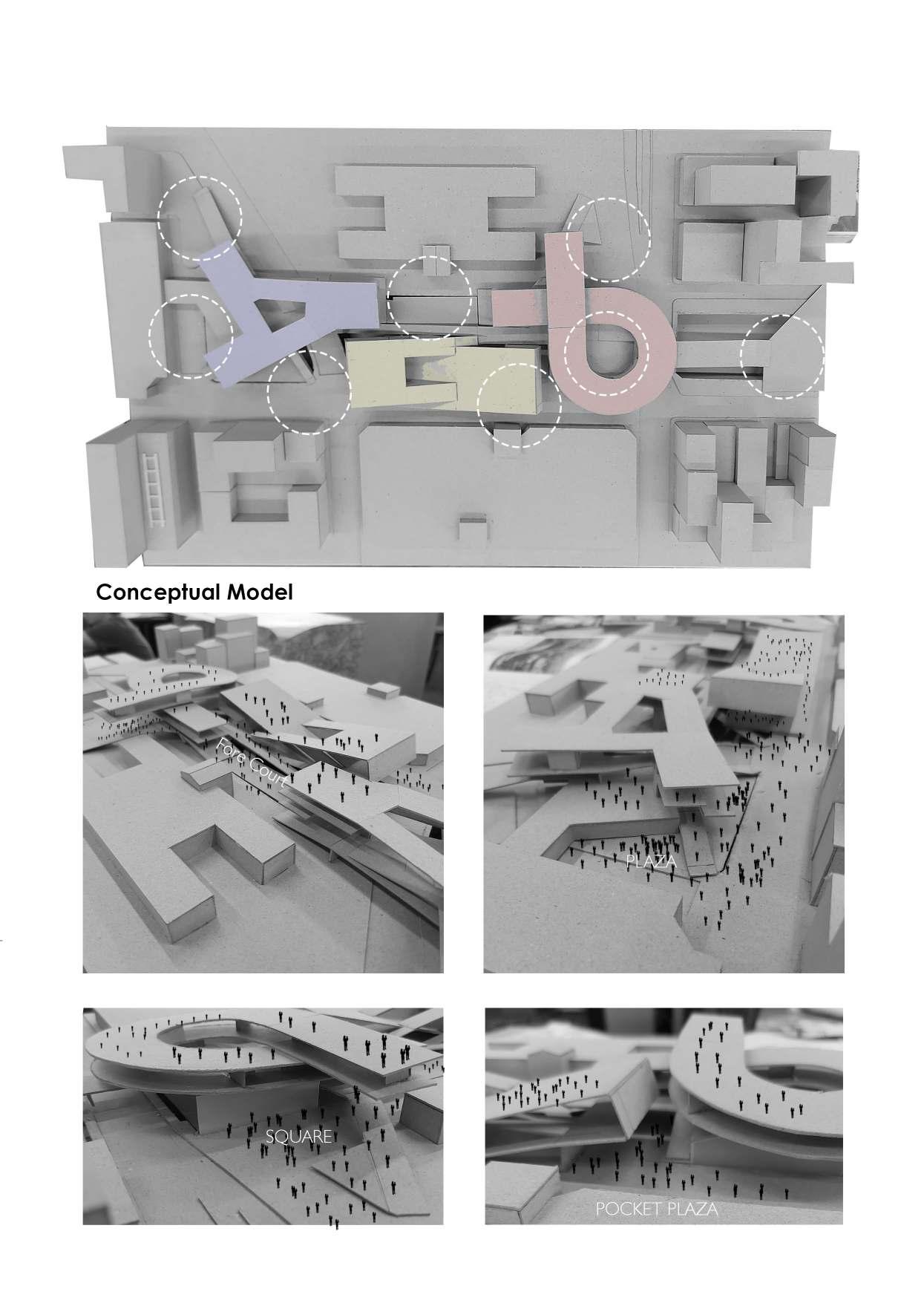

Towards a Connected Urban Landscape

The Designs primary focus will be to facilitate connections between key nodes in the landscape. These nodes are identified by their proximity to energies, public infrastructure and activities. The connection will bridge the divide caused by the railway infrastructure, generating social interactions and activities along the way.

There is an Understanding that the railway has fallen into disrepair. The Design will act as if it is in use, there is a belief that it can be reinstated as am important connector within the city and greater south Africa. The intervention will need span the gap, creating a 'recreational bridge' for pedestrians.

It is important that the design responds to the needs of the ‘streets’, sprawling out to meet the energies, attracting pedestrians onto its social landscape. The Intervention will use elements of culture, sport, art and leisure to generator the social condenser, becoming a vibrant public space within the urban environment.

Imagining the nature of a

Hedonistic Urban Landscape

Figure 51. 'Hedonistic Urban Landscape : the game' (by author)

Figure 51. 'Hedonistic Urban Landscape : the game' (by author)

This chapter uses different analytical methods to understand the nature of the design in relation to existing archetypes. These methods look at structuring elements, programmatic requirements, and construction information, of architectural projects, to establish particularities for the design. This process allows for well-informed design decisions based on the principal insights gained from these precedent studies.

This treatise aims to provide a model for public space in South African cities. The model looks to reimagine unproductive and surplus urban infrastructure and buffer zones, into vibrant public spaces.

The Johannesburg CBD is full of life streets bustling with trade and transport, however, the urban condition is poor and unsafe. Derelict infrastructure and inadequate public spaces have created a sense of disconnection. There is a need to create hedonistically sustainable architecture that focuses on generating holistic wellness within the urban environment. By re-imagining the railway infrastructure into a recreational landscape, the design will stitch together the urban landscape and incorporate elements of active leisure. This holistic response can regenerate the urban environment and increase the wellness

of its inhabitants by imbuing a sense of movement, connectivity, and continuity.

This chapter will establish the urban type as well as particular archetypes for intervention. Principles of public space will be used to assess and extract strategies from precedent studies. This analysis will provide an understanding of how the design can begin to function as a positive public urban space.

Figure 53. Chapter 3 process (by author)What makes positive public urban space?

Public space is vitally important within the urban environment. These spaces provide citizens with a break from the monotony and repetitive city life cycle of; commute, work, and sleep. They are the streets, parks, plazas, and squares that the public can freely access. Each urban type is structurally different, but the same elements make them successful. These spaces are easily accessible, they offer opportunities to gather, play, or relax. They are people-centered spaces that offer various opportunities for social interactions.

Large open urban area surrounded by buildings. Similar to 'Squares', but with no specific activity.

Open urban area preceding a prominent structure, generally public or civic in nature

Movement through between structures, different scales will allow it to become a Lane, Street or Boulevard.

Large open green area in the city/ town, surrounded by buildings. Variations include; Pocket Parks, Neighborhood parks and large City parks.

Figure 54. Gathering in Braamfontein (Lee, n.d.)The urban environment is a complex organism. Knowing what makes it function takes a good amount of research and understanding. Jan Gehl is an urban theorist, analyst and designer that has spent many years observing the urban environment. In his book, Cities for People (2010), he shares his insights and ideas into what makes positive urban spaces. Gehl (2010) suggests that good public space is filled with public life and that this is achieved by providing a diverse range of activities for people. He presents a particular table that categorises these activities into essential, optional and social activities, each with a plotted respective influence.

Comfort focuses on how people can interact with the space by providing high degrees of accessibility to provide maximally inclusive spaces. It should create opportunities to sit, watch, linger, and chat. It should also facilitate various forms of play and exercise throughout the day.

Enjoyment focuses on how people feel in these spaces. Are elements of the building on a human scale? The spaces should create diverse opportunities for the enjoyment of positive aspects of the climate, as well as other positive sensory experiences.

Further distilled into a set of design criteria, these values become the principles that are used as a litmus test for the precedent studies. These principles help to understand how designers may have taken advantage of some of the criteria in each of their particular responses.

Principles for Positive Public Urban Environments :

Designing for human scale.

Ensuring comfort, shelter, and safety.

The Table illustrates the key influences that optional activities can have. They are directly proportional to the quality of the spaces, offering a diverse range of options for a diverse range of users. Choice is crucial in attracting people, who want to participate in leisure activities, to spaces that add value to their lives. Diversity can help create interesting public spaces.

CitiesforPeople(2010)provides three values that can be integrated into designs to ensure their success: protection, comfort and enjoyment.

Protection focuses on how space works for the people. It should insist on the separation of pedestrians and vehicles, creating more walkable and bikeable spaces. It is also about providing shelter from the elements and any other unpleasant sensory experiences. Day or night, these spaces should utilise passive design elements to facilitate a safe environment for people.

Incorporating diverse programming.

Providing diverse movement options that imbue continuity.

Ensuring connectivity, both visually and physically, to space and activity.

Integrating levels of hierarchy into spaces, movement, and activity.

Ensuring sustainability both environmentally and hedonistically.

Creating a design with maximum integration with the urban system.

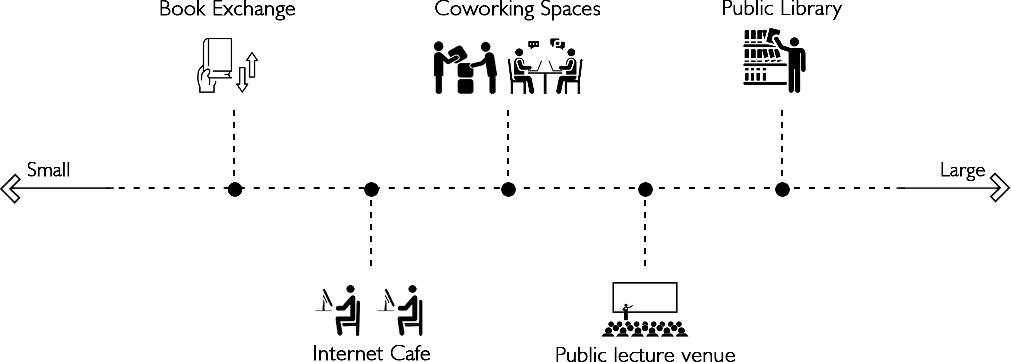

The Urban Park as a base.

The model seeks out terrain vague to find unproductive and surplus spaces within the city. Generally, these are open spaces or derelict infrastructure. The model will often become a form of urban landscape while maintaining its focus on incorporating various forms of physical activity. A park can be defined as a large area of land used by the public for recreational activities or leisure. They come in a variety of forms, from amusement and themed, to nature or urban (DPLA, 2022).

In recent years there has been a boom in urban parks as a tool for regeneration. They are used to revitalise dead zones or derelict industrial infrastructure within a city. These elements are re-designed and reused in new ways. The urban park brings together a collection of social activities that help to activate these spaces.

Urban parks, like an oasis within the city, are open areas of land that provide citizens with opportunities to play, rest and socialise. Historically, these parks were incorporated into cities as public squares, open grounds, fairgrounds or simply as a tool for

beautification (Ellis & Schwartz, 2016) In modern cities, urban parks have gained popularity as citizens feel the negative effects of dense city spaces. As cities have grown, the ‘concrete jungle’ has failed to adequately provide open green spaces for its citizens, who miss out on the wellness benefits of nature and recreational activities. These spaces function as community centres and places for people to gather, away from work and home. In line with Ray Oldenburg’s (1989) theory, they would be classified as third places, key components to the success of a city system.

HIGH LINE

Architect and urban designer, Susannah Drake (Drake,2013), talks about the importance of reengineering these spaces into vibrant public parks. Distressed urban environments can be revitalised with ecologically conscious solutions, regenerating these environments into productive urban spaces. Through this process, the they can serve as tools to stitch together urban communities, improving the health and wellness of citizens and the urban space. This Narrative is embodied in the development of the Highline in Manhattan.

Constructed as an Elevated Railway system in the 1960’s, the infrastructure runs through a dense urban community. Development saw the infrastructure challenged and nearly demolished. The Cities Governance decided against this in favor of converting it into public space. A design was divided into 3 sections, allowing for the redevelopment to happen in phases. The space would integrate green spaces, landscaped seating and various recreational activities. Since its conversion, which began in 2006, the park has become one of New York’s most popular public spaces. (Aitani and Sathaye, 2017)

Connection to bellow

Varied landscaping

Green integration

Partofsection2

Multiple activities

The park contains different moments for play, rest and performance, generating various experiences for users. Moment for rest, peering at 'framed' urban life Landscaping-to-seat Figure 58. Collage : The High line Analysis (by author)Urban Park

Positivespacebetween

Establishing The Archetypes

Within architecture, public recreational buildings serve the same purpose as their urban counterparts. Libraries, nightclubs, gymnasiums, cafes, casinos, and theatres are examples of spaces where people come together to seek entertainment or leisure. Rem Koolhaas believes that these are the spaces people actively seek out and are fundamental in establishing the social condenser.

The urban park serves as a base for a series of recreational activities. The design itself will look to one key section of the park as the catalyst for the development. Although the whole park will incorpo-

rate various recreational activities with commercial attachments, this section will consist of three main archetypes: urban sport, theatre, and library. Previously scattered throughout the city, these elements come together to create a multi-functional urban landscape. The analysis will look at establishing the particularities of each type in order to find opportunities for cross-programming. Due to the nature of the design becoming an active urbanscape, sports and active leisure are given priority, having the greatest influence on the structuring elements.

"Typical Structure of Public Activities"

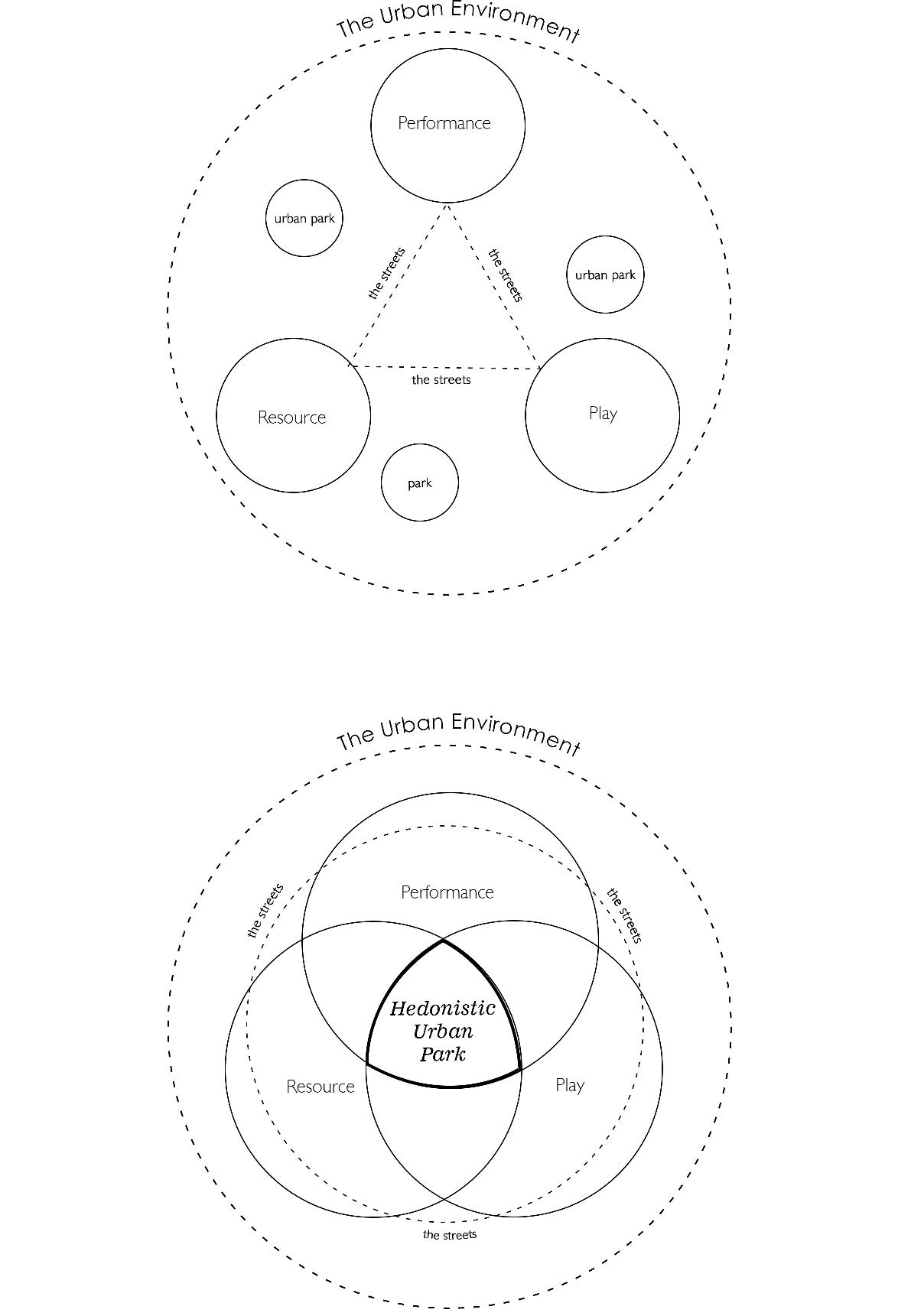

"The Hedonistic Urban Park"

PLAY.

Traditionally, sports facilities are disconnected from the urban environment. They have been placed on the outskirts of cities, as isolated and mono-functional interventions, often closed off from the general public (Casas Valle & Kompier, 2012: 1). Physical activity has become increasingly important for the modern lifestyle. The city dweller makes use of gyms or parks for diverse types of active leisure. This has led to sports facilities adapting and changing to be more integrated into the urban environment. Even sports themselves have evolved to facilitate the needs of the city dweller. This has seen a rise in the popularity of urban sports like climbing, skating, futsal, and parkour (Kural,1999). Cities are seeing the modern sport typology become a new form of public urban space.

Sports and recreational exercise can have a positive effect on the regeneration of communities. It plays a vital role in the development of society and can have various carry-over benefits like :(Houlihan & Malcolm, 2016.)

Improved social skills.

Values found in sports are often reflective of what is deemed ethical in society. They provide a framework of reward for good behaviour and penalties for disobeying the rules. Sport provides role models and examples of desired behaviour, where hard work and commitment to a craft are rewarded and violence and cheating are punished.

Social integration.

Integrating sport into communities enables people the opportunity to be part of a collective or group, part of something greater than themselves. This creates social cohesion and allows people who feel lonely or lost the opportunity to feel included. Sports can give strangers a common goal and purpose to strive for, thus, forming bonds and revealing the benefits of teamwork in a social setting.

Social mobility.

Sport can level the playing field when it comes to social status. There are a large number of famous sportsmen and women that have overcome hardships and poverty. Through hard work and perseverance, they were able to use sport as a way to earn a living and increase their social status.

Different activities at various scales

Figure 62. 'Street Soccer in third space' (reference)

Figure 63. Physical Activities at various scales

Figure 62. 'Street Soccer in third space' (reference)

Figure 63. Physical Activities at various scales

As the need for new kinds of sports facilities grow, designers are focused on developing a set of tools to ensure that they become a productive part of urban society. A paper written by Daniel Casa Valle and Vincent Kompier (2012), titled Sport in the city, provides a toolbox for how these facilities can become successful public urban spaces

.

no.ToolDescription

1 Sport size/ typology

2 Position in the city

Sports have particular spatial and functional requirements, these are the starting point of the design phase.

Combining sports with other recreational facilities like; Malls, restaurants and hotels helps to increase passive participation in sports. This encourages mixed crowds and allows the design to become a hub in the city.

3 Relation with public space

Sports facilities can become an extension of public spaces, allowing interior activities to flow outwards.

4 Visibility Todays sports create the need for a stage; for watching, showing and chatting. Highly transparent facades shout, 'You can Exercise here!'.

5 Distance and proximity

Focus on creating attractive connections within the program and to public space to become an extension of urban life.

6 Accessibility Continuity is key, between programs and the public. Encourage passive forms of exercise through slow traffic routes Include bicycle facilities.

7 Public access and lock-ability

Spaces generally need to be locked during unused hours. Avoid using absolute barriers like walls or fences wherever possible.

8 Flexibility Sports Facilities generate large volumes, able to adapt to many different activities. Create functionality to generate multi-use spaces.

Table 02: Toolkit for sport facilities (Casas Valle & Kompier ,2012).

Table02Shows how sports facilities share the same goals as public space and the treatise model. Understanding these connections will help to generate an inclusive sports element in the urban park. This shows that sports and active leisure can become vital contributors to the creation of a successful public environment.

The design should incorporate physical activity at various scales, from public outdoor equipment to private gymnasiums. These can be connected by movement, like bicycle amenities and running tracks, generating a multi-functional and inclusive urban landscape.

Precedents for Play

Park 'n' Play

/JAJA Architects

Location : Copenhagen Denmark

Program : Public Space on Parking Garage

Scale : 2400 m²

The Architects looked to redefine 'parking structure'. They Understood that a multi-strorey parking structure would create a 'dead zone' within the public realm. They used 'Play' to create a vibrant public space on the roof of the structure, promoting exercise and social interaction within the community.

" I can see the ski slope from here"Figure 64. Park 'n' play aerial view (reference)

The design generates a landscape for play, ustilising colour , supergraphics, varied surface forms and textures, as well as multiple interactive elements. The Scheme creates different pockets of space for different intentions; Single person seating, swings, exercise stations and green areas.

" A secluded spot to read "

" A place to gather with friends and family"Figure 66. Park and play aerial view (reference) Figure 67. Park 'n' play seating (reference) Figure 69. Park 'n' play aerial (reference) Figure 70. Plan And Elevation (reference)

Street Dome

/ CEBRA + Glifberg - Lykke

Location : Haderslev, Denmark

Program : Urban Sports Park

Scale : 1500m² dome + 4500m² park

" A concrete landscape of hills, ramps and rails"

The design of a skate park where the building is enticingly 'Skate-able'. The architect uses the dome shape to create edges that are interactive, with slopes or seating. The Dome houses other urban sports like basketball and climbing walls, generating a multi-functional urban sports landscape

"The edges of the dome are primed for play"

"The sidewalk is activated for play, next to sport facility"

Born Skateplaza

/PMAM

Location : Parc de la Ciutadella, Barcelona

Program : Public Space

Scale : 500 m²

"Urban landscaping for play, simple form, multiple uses"

Figure 71. Elevation of Street Dome (reference)

Figure 72. Street Dome plan (reference)

Figure 73. Street Dome diagram(reference)

Figure 74. Born Skate Plaza Photo(reference)

Figure 75. Born Skate Plaza Aerial Photo(reference)

Figure 71. Elevation of Street Dome (reference)

Figure 72. Street Dome plan (reference)

Figure 73. Street Dome diagram(reference)

Figure 74. Born Skate Plaza Photo(reference)

Figure 75. Born Skate Plaza Aerial Photo(reference)

A composition of sports elements and public spaces

Gammel Hellerup Gym

expansion /Bjarke Ingels Group

Location : Hellerup, Denmark

Program : University Gymnasium & Sports field

Scale : 2500 m²

BIG Architects have a knack for generating interactive landscapes. They used the constraint of "minimum heights for sports " below to inform the roof landscape for the plaza above. Instead of the courts becoming a building, they are able to become multifunctional landscape for play and social interaction.

" Plaza becomes interesting landscape to inhabit above"

"Height Requirements for sport generate form of roof structure"

Figure 77. Gym Interior (reference)

Figure 79. Aerial view of Gammel Hellerup (reference)

" Plaza becomes interesting landscape to inhabit above"

"Height Requirements for sport generate form of roof structure"

Figure 77. Gym Interior (reference)

Figure 79. Aerial view of Gammel Hellerup (reference)

Jong-Am Sqaure

/ Simplex Architecture

Location : Seongbuk- gu, South Korea

Program : Public Sports Courts

Scale : 693 m²

"Movement uninterrupted, activities Exposed"

The architects saw the void left by transport infrastructure. They sought to activate the space beneath the overpass with an element of play. The traffic island becomes a public space for sports and other activities.

The design utilises a minimal material pallet with the focus on create highly flexible internal spaces with maximum visibility to the urban environment

"Play in Third Space"Figure 80. View to Jong-Am Square from adjacent street(reference)

"Varied multi-functional spaces for public use"

Prefabricated modular Construction

"Highly Visibility between the space and the city"

The Simple form is achieved through the use of timber and steel flames that create a structure that spans the area without interruption.

The timber adds a natural element to the concrete environment.

Figure 82. Flexible interior play spacesStreet Mekka

/ EFFEKT

Location : Viborg, Denmark

Program : Community Sports Centre

Scale : 3170 m²

This community sport centre reuses an old warehouse space for a collection of Urban sports. Industrial construction is a good fit for sports due to its large spanning structure being highly flexible for these types of activities. The architects organised a series of urban sport activities, focusing on connectivity between them.

"Structure opens to spill out"

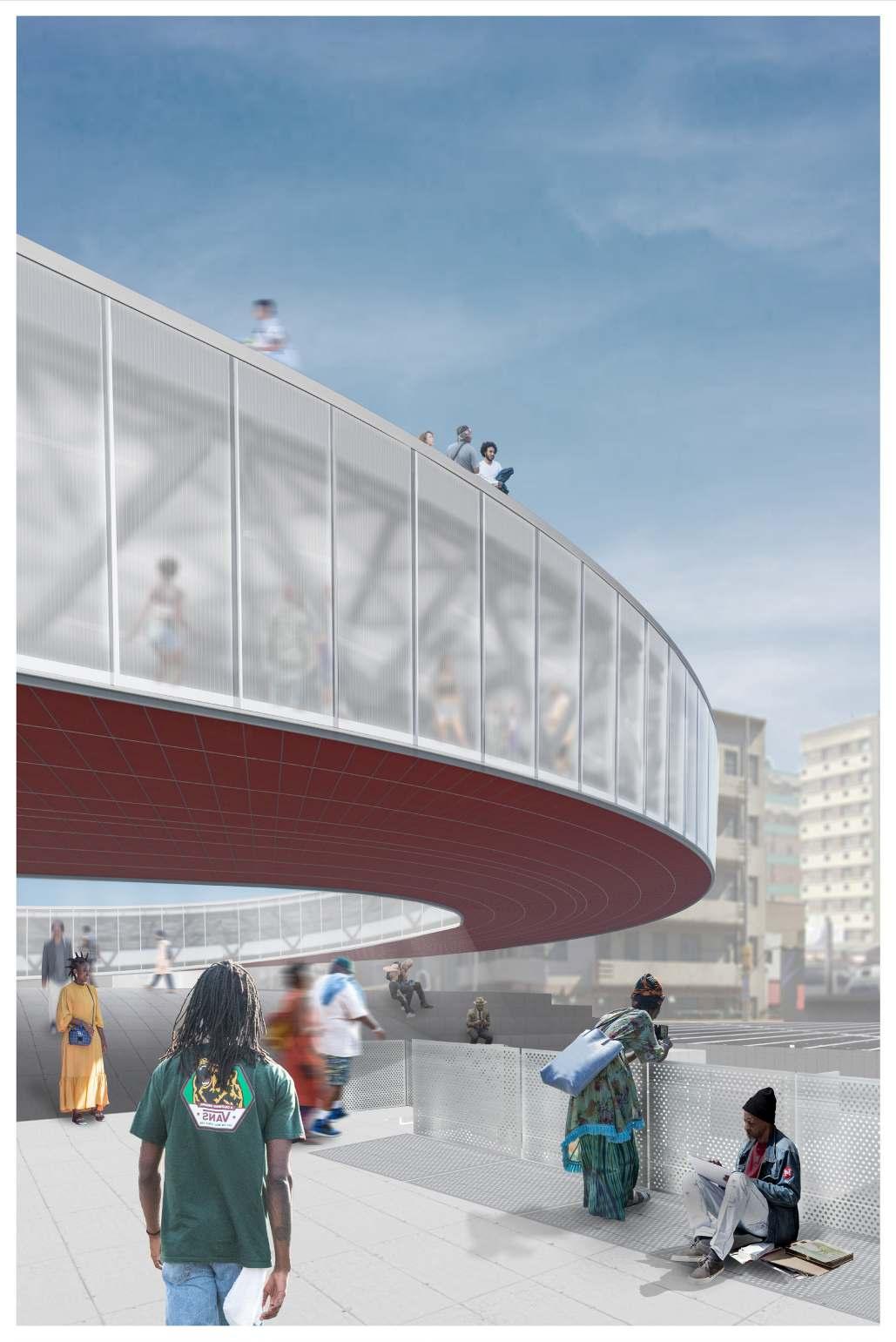

"Beacon At Night"Figure 84. Entrance : Inner glow through polycarbonate facade Figure 85. Site Plan

Multiple Elements where suspended on the concrete substructure to create enclosed office and table sport spaces.

Polycarbonate panels where the materials of choice for create a connection between inside and outside. This was further aided by varying degrees if 'InsideOutside' spaces.

"Visible Interior Movement"

"Inside - Outside"

"Technical Detail "

"Visual Connections"

Figure 87. Interior : Visually connected between spaces

Figure 90. Interior : 'warehouse' space

Figure 88. Inside outside space occupied by urban sports

Figure 91. Polycarbonate facade detail

"Visible Interior Movement"

"Inside - Outside"

"Technical Detail "

"Visual Connections"

Figure 87. Interior : Visually connected between spaces

Figure 90. Interior : 'warehouse' space

Figure 88. Inside outside space occupied by urban sports

Figure 91. Polycarbonate facade detail

Camp del Ferro

/ AIA, Barceló Balanzó Arquitectes, Gustau Gili Galfetti

Location : Barcelona, Spain

Program : Recreational Sports Centre

Scale : 7237 m²

"Steel Trusses Popular for large spanning volumes"

"Natural Light through Facade"Figure 93. Site Diagram showing density Figure 92. Aerial view of forecourt Figure 94. Interior of sports court on ground level