7 minute read

Time in art and literature

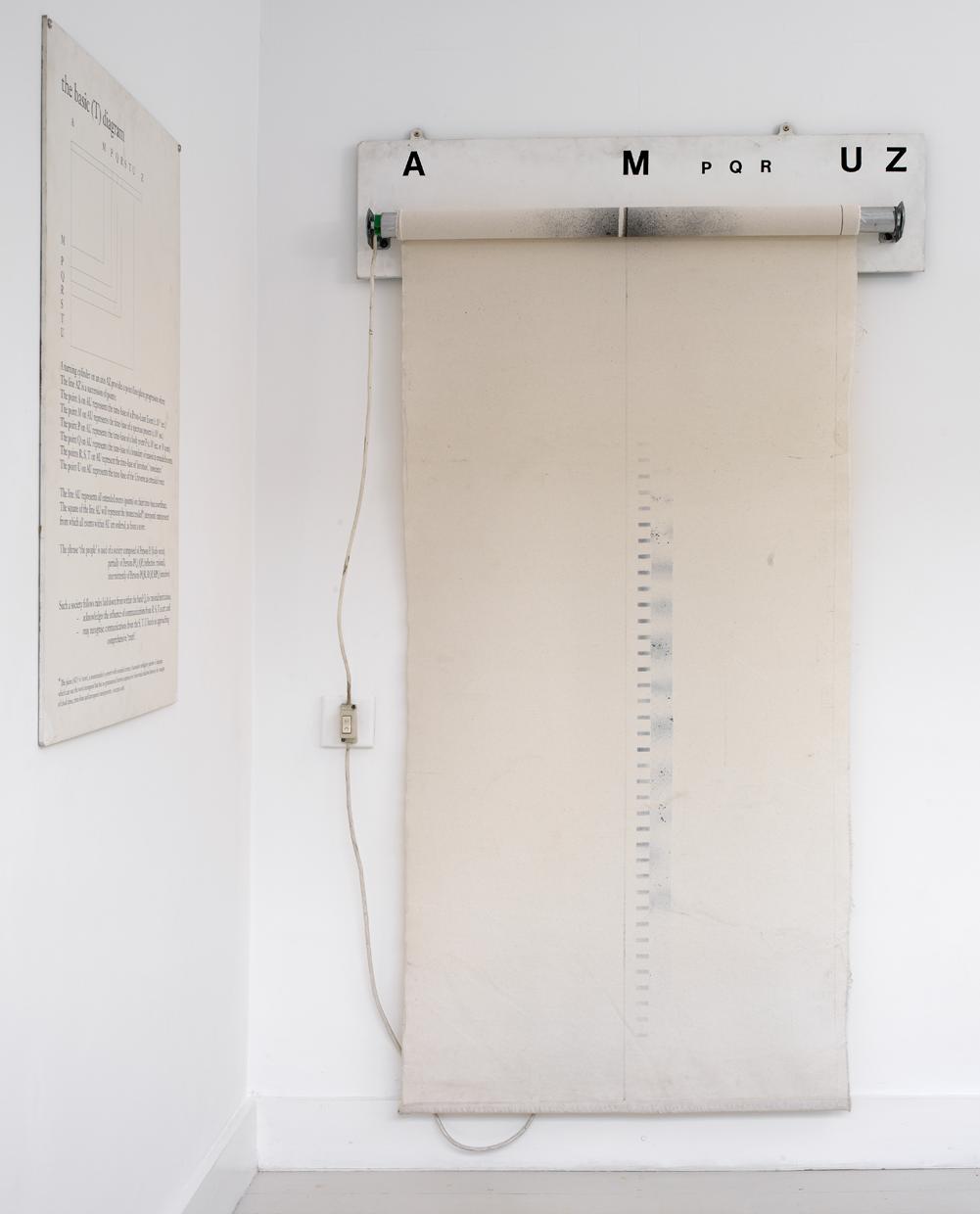

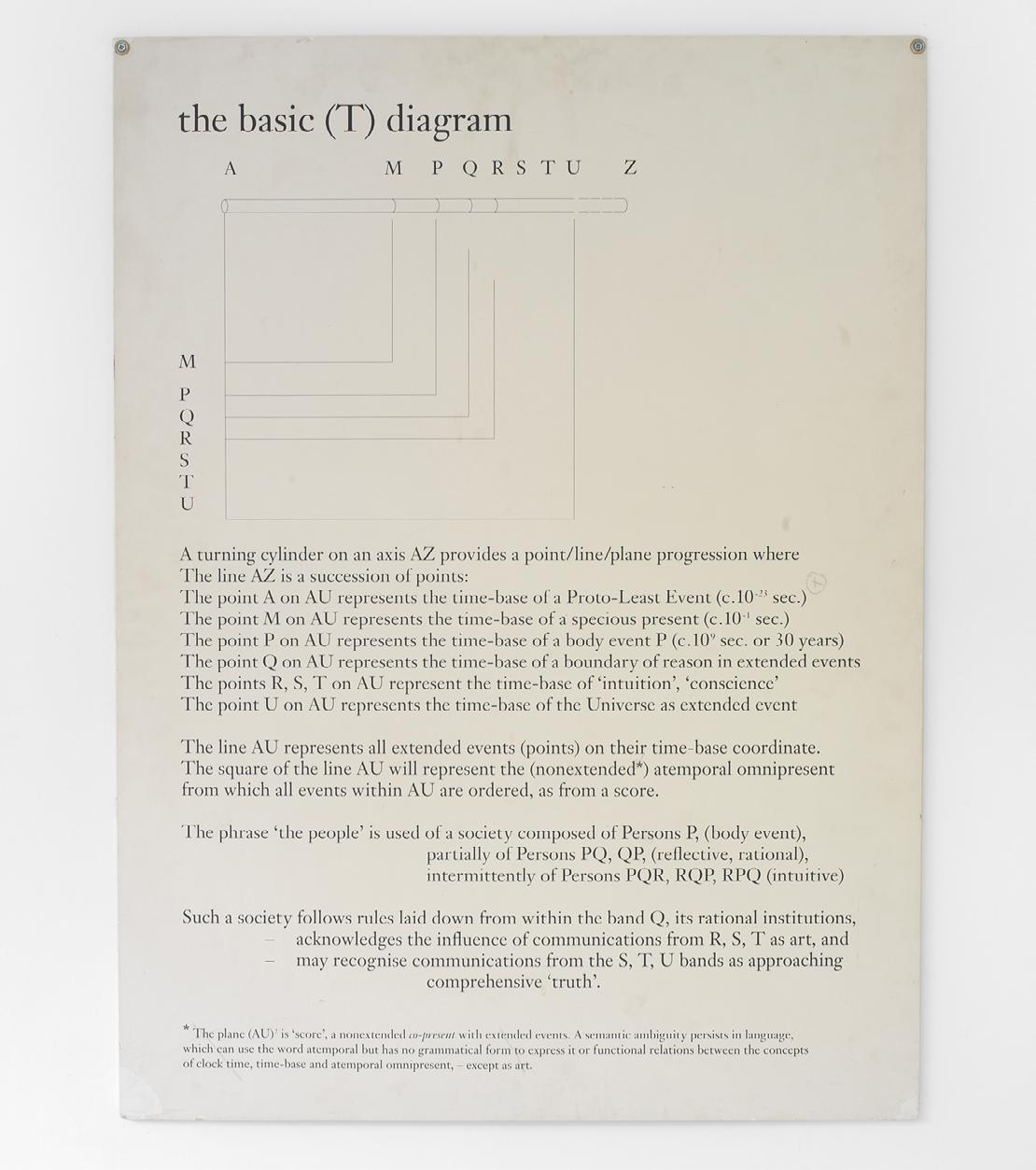

Time-Base Roller with Graphic Score (1987) Canvas, electric motor operating metal bar, wood, graphite. Photo: Ken Adlard, Flat Time House The Basic T Diagram (1991) Text on hardboard, Photo: Ken Adlard, Flat Time House

Advertisement

John Latham’s ‘Flat Time’ Theory

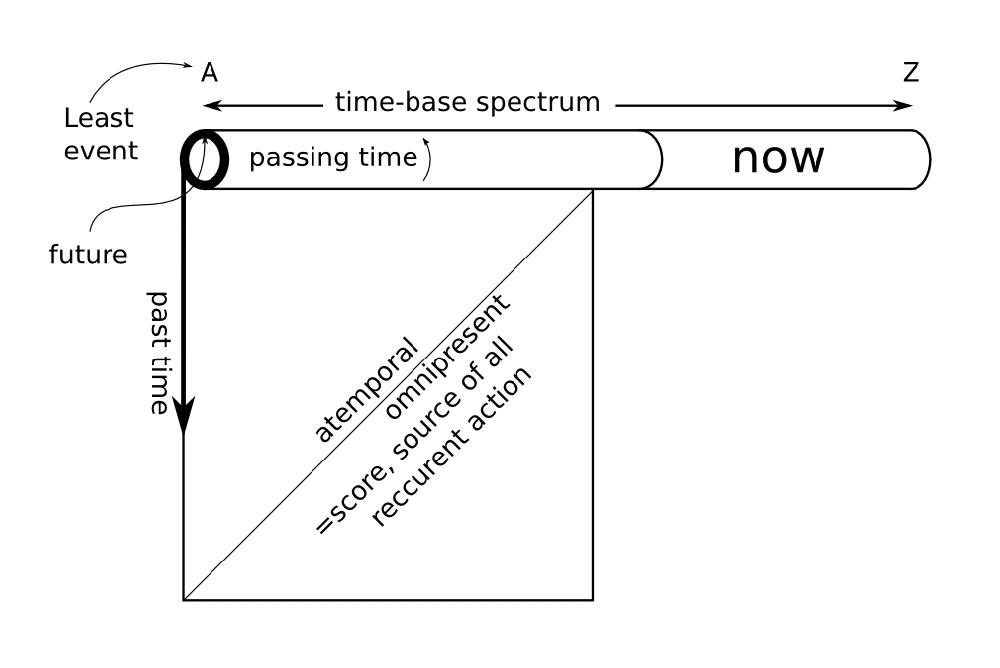

The long Time-Base Roller canvas is painted in strips and is wound round a turning barrel operated by an electric switch. As the barrel turns, more of the canvas is unrolled until the whole length is unfurled. The expanse of the rolled canvas represents an entire model of the universe understood timelessly like a musical score. The front side of the canvas is only momentarily visible to the viewer as it passes over the front of the cylinder before falling down behind, where its length is visible only in reverse. Most of the canvas remains obscured from our view most of the time, as it is either rolled up around the barrel or visible only from behind. Our understanding of the universe is therefore restricted to our lived experience of it, i.e. the narrow strip, briefly visible. The continuous change in what can be seen on this narrow strip represents the passing of time. The marks on the front of the canvas represent events occurring on different frequencies, or time-bases, as described by the letters along the top edge (see Basic T Diagram). The way the flat canvas is able to represent an entire Universe by it’s length and breadth is the root of the term Flat Time.

Zoogeographical map of the Soviet Union, c. 1928.

Fedorov’s Geography of Time, Trevor Peglan

‘Indeed, for Fedorov, such an undertaking would collapse the distinction between theoretical and practical knowledge/ action. The solution to the nature-culture divide is the total geo-engineering of the earth. Now, we see echoes of this attitude in some of the more stupid versions of ‘Anthropocene’ theory ‹ i.e., the idea that nature doesn’t exist and so we should just get on with it. But the much more radical proposal in Fedorov is that we can apply that same idea not only to the planet, but to time. Not only does Fedorov want to collapse the distinction between humans and nature, he wants to collapse the distinctions between the past, the present, and the future in a great project of temporal engineering. This temporal engineering is related to the second of the great Fedorovian projects, which is of course the resurrection of the dead. The following quote is at the crux of it: Death can be called real only when all means of restoring life, at least all those that exist in nature and have been discovered by the human race, have been tried and have failed.

And finally, “although stagnation is death and regression is no paradise, progress is truly hell, and the truly divine, truly human task is to savethe victims of progress, to lead them out of hell.” So, for Fedorov, the problem with the notion of progress, and history more generally, is that it produces alienation ‹ alienation from one generation to the next, and from the present to the past. And just as Fedorov’s geo-engineering seeks to collapse the philosophical and the practical.’ ‘In sum, Fedorov’s notion of time is very different from a Newtonian conception of time as an arrow or of a great clock counting off the seconds. It’s also different from the eschatological notions of time we find in the Abrahamic religions and Jewish, Christian, and Islamic theology. For Fedorov, time isn’t an arrow so much as it is a landscape. And just as Fedorov’s ideal of kinship connects us to distant galaxies, it connects us across time to generations of people who have died in the past and who will be resurrected in the future. Time for Fedorov is not linear but a topology whereby the past can be the future, the future can be the past, and where humans are central to the ethical stewardship of temporality.

In the end it seems that in Fedorov’s philosophy, the full realization of kinship would spell the end of time and space. Space would be fully connected and managed through kinship, and the universe would have no ÒoutsideÓ ‹ there would be no frontiers. Similarly, full kinship seems to indicate an end to time, where the past, present, and future exist simultaneously and everyone who had ever lived is present and immortal. Indeed, this is what Fedorov seems to mean when he concludes his Philosophy of the Common Task with the following passage: “For the vast intellect able to encompass in one formula the motions both of the largest celestial bodies in the Universe and of the tiniest atoms, nothing would remain unknown; the future as well as the past would be accessible to him. The collective mind of all humans working for many generations together would of course be vast enough all that is needed is concord, multi-unity”. ’

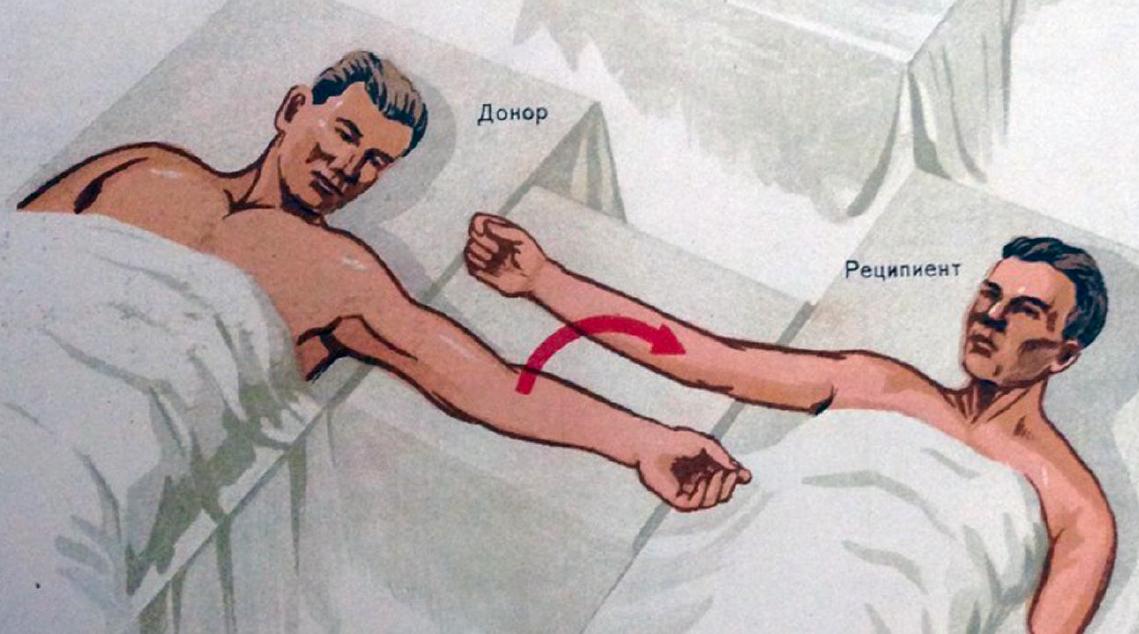

An illustration from a Soviet manual describes the setup for a blood transfusion.

Cosmic Catwalk and the Production of Time, Anton Vidokle and Hito Steyerl

“Nikolai Fedorov. Fedorov believed that death is not natural and is more like a flaw in our design. Like a disease, death is something to be fixed, cured, and overcome by technological, scientific means. This becomes the central point of his philosophy of the Common Task: a total reorganization of social relations, productive forces, economy, and politics for a single goal of achieving physical immortality and material resurrection. Fedorov felt that we cannot consider anyone really dead or gone until we have exhausted every possibility of reviving them. For him the dead are not truly dead but merely wounded or ill, and we have an ethical obligation to use our faculty of reason to develop the necessary knowledge, science, and technology to rescue them from the disease of death, to bring them back to life. From this point of view history and the past is a field full of potential: nothing is finished and everyone and everything will come back, not as souls in heaven, but in material form, in this world, with all their subjectivities, memories, and knowledge. What appears to be a graveyard is in fact a field full of amazing potential.“

“Financial capitalism does not care about the dead because they do not produce or consume. Fascism only uses them as a mythical proof of sacrifice. Communism also is indifferent to the dead because only the generation that achieves communism will benefit from it; everyone who died on the way gets nothing. It seems that only indigenous cultures at this point keep some reverence for the dead. Fedorov writes that a true religion is a cult of ancestors.”

“This intersects with thought experiments to contain the dangers of Artificial General Intelligences (AGI). People think AGI could be dangerous and override human control and even extinguish humans. Like the dead, AGIs are seen as potentially dangerous creatures and there are questions of timing or containment. Within the AGI debate, several ‘solutions’ have been suggested: first, to program the AGI so it will not harm humans, or, on the alt- right/fascist end of the spectrum, to just to just accelerate extreme capitalism’s tendency to exterminate humans and resurrect rich people as some sort of High-Net-Worth Robot race.

“These eugenicist ideas are already being implemented: cryogenics and blood transfusions for the rich get the headlines, but the breakdown of health care in particular ‹ and sustenance in general - for poor people is literally shortening the lives of millions, curtailing the possibility for them to pass on their genes. Negating, preventing, or destroying social health care programs is the most important accelerationist policy, and it has already been underway for some time. There is another aspect to this: the maintenance and reproduction of life is of course a very gendered technology - and control over this is a social battleground.”

“In the present reactionary backlash,oligarchic and neoreactionary eugenics are in fullswing, with few attempts being made to containor limit the impact on the living. The consequences of this are clear: the focus needsto be on the living first and oremost. Because if we don’t sort out society ‹ create noncapitalist abundance and so forth ‹ the dead cannot be resurrected safely (or, by extension: AGI cannot be implemented without exterminating humankind or only preserving its most privileged parts).”