9 minute read

A frozen repository

Methane seeping through Alaskan lake

Advertisement

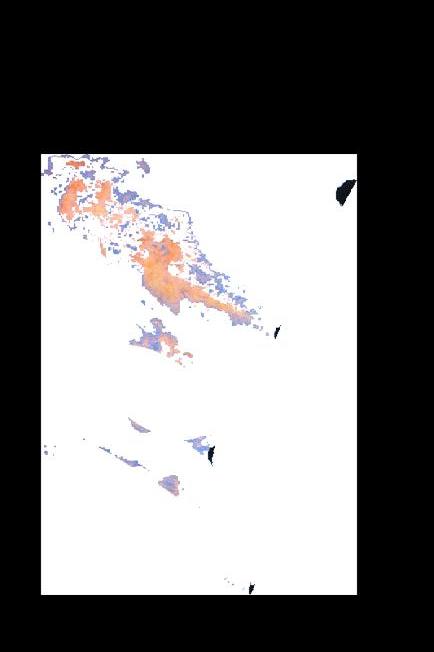

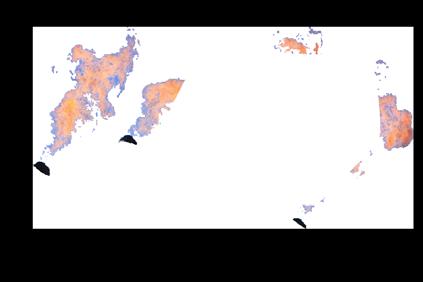

Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment, NASA Airborne Science Program

Gas fields and mercury deposits

A 2014 study in Environmental Research Letters estimates that thawing permafrost could release around 120 gigatons of carbon into the atmosphere by 2100, resulting in 0.29°C of additional warming (give or take 0.21°C). By 2300, another study in Nature Geoscience concludes, the melting permafrost and its resulting carbon feedback loops could contribute to 1.69°C of warming. (That’s on the high end. It could be as low as 0.13°C of warming.) The logic here is simple: The more warming, the greater the risk of kick-starting this feedback loop. A study published in Nature Climate Change in 2017 predicted that 1.5 million square miles of permafrost would disappear with every additional 1°C of warming. A new study in Geophysical Research Letters finds that the Arctic permafrost is the largest repository of mercury on Earth. Mercury is a potent neurotoxin. And scientists now think there is around 15 million gallons frozen in permafrost soils — nearly twice the amount of mercury found in all other soil, the ocean, and atmosphere combined. “The release of heavy metals, particularly mercury, and other legacy contaminants currently stored in glaciers and permafrost, is projected to reduce water quality for freshwater biota, household use and irrigation,” the IPCC reports.

Methane oxidation

Arctic lakes are sensitive indicators of global changes in the environment and climate, as well as the effects of regional and transboundary transport of pollutants. Mercury is present in many of the world’s gas fields causing harmful emissions and damage to human health via exposure. As the soil thaws further, the 56 thousand tonnes of mercury also get released contaminating the ecosystem and reducing water quality for freshwater biota, household use and irrigation .

Methane oxidation is a microbial metabolic process for energy generation and carbon assimilation from methane that is carried out by specific groups of bacteria, the methanotrophs. Methane (CH4) is oxidized with molecular oxygen (O2) to carbon dioxide (CO2).

Methane gas extraction infrastructure is seen in Lake Kivu in Gisenye, Rwanda, 2010. Photo by Eric LAFFORGUE/Gamma-Rapho

Methane gas extraction from lakes

Lake Kivu contains exceptionally large amounts of dissolved carbon dioxide and methane in its deep waters. These gases have accumulated over 800 to 1000 years.

The carbon dioxide originates from two active volcanoes at the lake’s northern side: the Nyiragongo and the Nyamuragira. These 20,000 year-old volcanoes are among the most active in the world. The methane comes from the degradation of organic matter produced at the lake’s surface (representing one third of the methane produced in Lake Kivu) and the second process – which produces most of the methane in the lake – is the conversion of carbon dioxide into methane. The concentrations of carbon dioxide are five times higher than the concentrations of methane.Such a large accumulation of methane in a lake is unique, and has never been reached in any other lakes.

Simply put, this particularity is caused because the gases are being trapped in the deep waters by an inflow of deep sub-aquatic spring containing warm, salty and carbon-dioxide rich water. This effectively creates a seal.Currently, 45km3 of methane are economically viable for extraction, which could generate as much as 500 MW of electricity over 50 years. But the electricity produced is highly dependent on the technology and the achieved efficiency. Methane extraction is beneficial for two reasons. First, the dissolved gases pose a risk to the local population, as they could potentially erupt from the lake. Explained very simply, a large disruption – such as a landslide – could trigger gas bubbles to rise to the surface and erupt without warning signs. Gas bursts, such as this, took place twice in Cameroon. Lake Monoun’s gas burst in 1984 killed 37 people, and a gas burst at Lake Nyos in 1986 caused the death of 1,700 people. By removing methane, the chances of a gas eruption are strongly reduced because there’s less pressure.

Secondly, extracting methane will produce electricity, which is crucial for Rwanda’s development. Currently only about 30% of Rwandans have access to electricity through the national grid. The installed capacity is 218 MW. Methane extraction could significantly contribute to Rwanda’s electrification and there are several projects underway to extract the gas.

The Rwandan government plans to reach an electrification rate of 100% by 2024. KivuWatt power plant – run by Contour Global – already extracts methane to generate electricity. The first phase already generates 26 MW of electricity. It will reach 100 MW in the second phase.

A public-private partnership – between Shema Power Lake Kivu Limited, formerly Symbion Energy, and the Rwandan Government – has a project to build a plant to provide 56 MW and to upgrade a pilot plant from the current 3.6 MW to 25 MW.

sediment, ice and methan bubbles natural gas extraction site

discontinuous permafrost Tundra

ice wedges Thaw lake

CH4 production

Talik - unfrozen ground under permafrost Taiga-Tundra Ecotone

buffer layer: snow and vegetation

soil surface interface

Active layer: annual freeze-thaw cycling Taiga

Permafrost layer

discontinuous permafrost

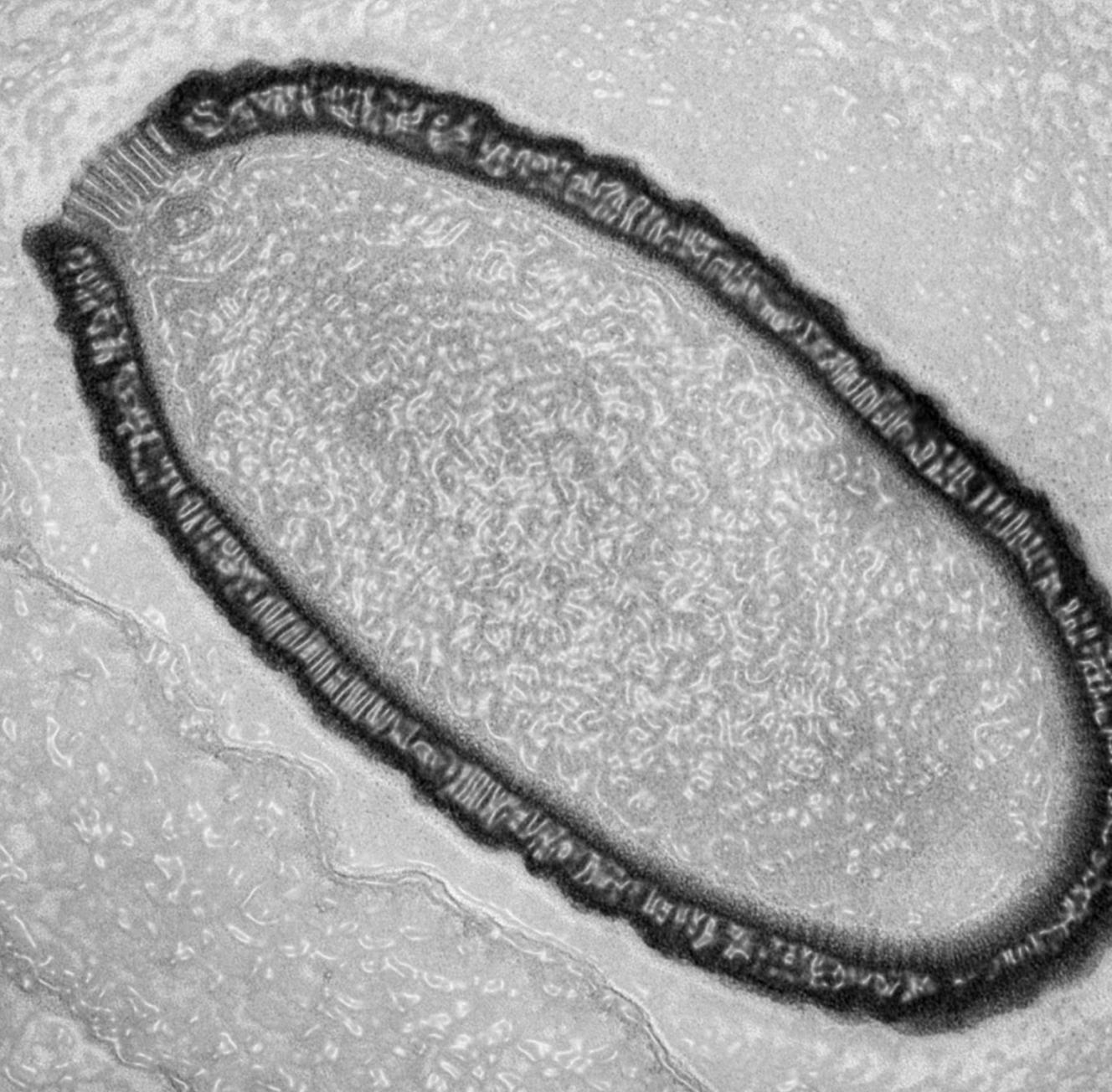

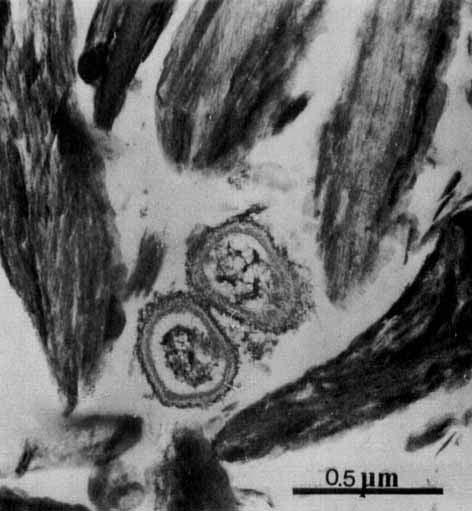

A Pithovirus (above, as viewed by electron microscopy) was found to be still active and able to infect an amoeba.

Permafrost, in its frozen state, can hoard materials for thousands of years without allowing them to decay. It can suspend bacteria in a kind of cryo-sleep—still alive for millennia.

Viruses trapped in cryosleep

The pithovirus itself is very different from any known virus. At 1.5 micrometres long by 0.5 micrometres wide, it is around 30 per cent bigger than what had been the largest known virus – the pandoravirus, researchers found. Yet despite being physically larger, the pithovirus has only a fifth as many genes as the 2500 in the pandoravirus. The two giant viruses share just five genes. Reviving the pithovirus needed no sophisticated techniques.

The researchers tracked and filmed the pithovirus’s entire life cycle. Once inside an amoeba, it migrates to the wall of a chamber called a vacuole. It does this with the help of an unusual structure at one end that the team discovered, which serves as a kind of cork. “Its function is to seal and protect the amphora-shaped particle, but as soon as it enters a vacuole, the cork is removed to initiate the infection,” says Chantal Abergel. “It allows the internal membrane of the virus to fuse with that of the vacuole,” she says.

Next, material from the virus spills out into the vacuole and turns it into a factory for making components of daughter virus particles. After a few hours, these assemble and mature into thousands of new pithoviruses which gather at the vacuole’s edges before bursting out of a completely emaciated amoeba to find new host cells to infect. “It literally sucks the life out of the cell within 12 to 14 hours,” says Abergel.

Reindeer grazing in Summer on Yamal, photo: Thomas Nilsen, The Barents Observes

Anthrax outbreak, Yamal 2016

Livestock have been raised along both branches of the Ob river of the Yamal Peninsula for several hundred years, especially since the Soviets took power in the 1920s and agriculture was designated a priority. The most important animals were horses, primarily larger types for draft purposes, followed by cattle for meat and dairy, followed by pigs. Further upstream to the south about a 1000 km on the Barabinsk steppe (prairie) is found the area which supplied much of Europe during the last century, especially Britain, with the famous Barabinsk butter and cheese. Since 1991 and the dissolution of the Soviet Republic, the importance of Yamal’s domestic livestock industry has been reduced considerably in the larger communities due to their access to modern means of transportation, but reindeer meat is still in high demand.

At the time the Soviets were expanding the Yamal livestock industry, the region became infamous for its anthrax. By the late 1920s, the disease had devastated the livestock and reindeer industries to such a degree that it became known in Russia, a country already well-known for anthrax, as Yamal disease. Some years it virtually wiped out the reindeer industry. Of the anthrax outbreaks that I have heard of, this was the largest in terms of numbers.

July 2016 had been the warmest on records over much of Siberia including the Yamal Peninsula. Sergey Semyonov, Rosgidromet’s Director of the Global Climate Change and Ecology Institute tells TASS that July 2016 turned out the warmest ever in Siberia since systematic weather observations began. Temperatures on Yamal have climbed above 30 degrees Celsius.

The 2016 anthrax outbreak is believed to come from an old burial site with reindeer that died of the disease more than 70 years ago. As a consequence, over 200 reindeer had to be put out while dozens of people, including children, had been infected.

Tusk hunters find a caramel-coloured mammoth tusk from the soil where it had been frozen for at least 10,000 years

Mammoth bones lying near the Kolyma river

The Siberian mammoth tusk gold rush

As permafrost soils thaw, Siberia is revealing its ancient treasure hoard faster than ever. Now, fuelled by Chinese demand for ivory, tusk hunters are racing to retrieve so-called “ice ivory” from the Siberian permafrost.

An estimated 80 per cent of Siberian mammoth tusks end up in mainland China, via Hong Kong, where they are carved and turned into elaborate sculptures and trinkets. Russia exported 72 tonnes of mammoth tusk in 2017 but exports have dropped off as a growing underground trade in tusks appears to be eating into the official trade. While collectors can obtain licences, they increasingly complain of pressure from the authorities who confiscate their finds and demand high tariffs. To avoid losing business, many are sidestepping existing regulations and selling their tusks quickly but for less money to Chinese dealers who come to buy them directly. Some see the legal mammoth trade as a relief valve that gives consumers an alternative to elephant ivory.