5 minute read

The Yamal Megaproject

The human scale at the Bovanenkovo gas field

Advertisement

Approximately 15 reindeer herding units travel through the area during summer along 21 migration routes. Reindeer herding among the Nenets people is nowadays organized in large enterprises, formerly as state managed agricultural farms. Each reindeer herding enterprise is composed of several brigades according to the number of the herds. Several herders work together and migrate with their families all year around in a brigade. In addition, there are also a great number of private herders. Many Nenets herders begin their migrations from the wintering areas in the south in mid-late March. It is home to approximately 270,000 reindeer and about 1,000 fully nomadic households, comprising ca. 5,000 nomadic people live on the Yamal peninsula. Herders can move up to 30km on a good winter day. As the snow melts, the distance is often limited to 7km depending on weather, total distance to summer pastures, ground conditions, dynamics and coordination with the migrations of other herders and the ecology of their reindeer.7

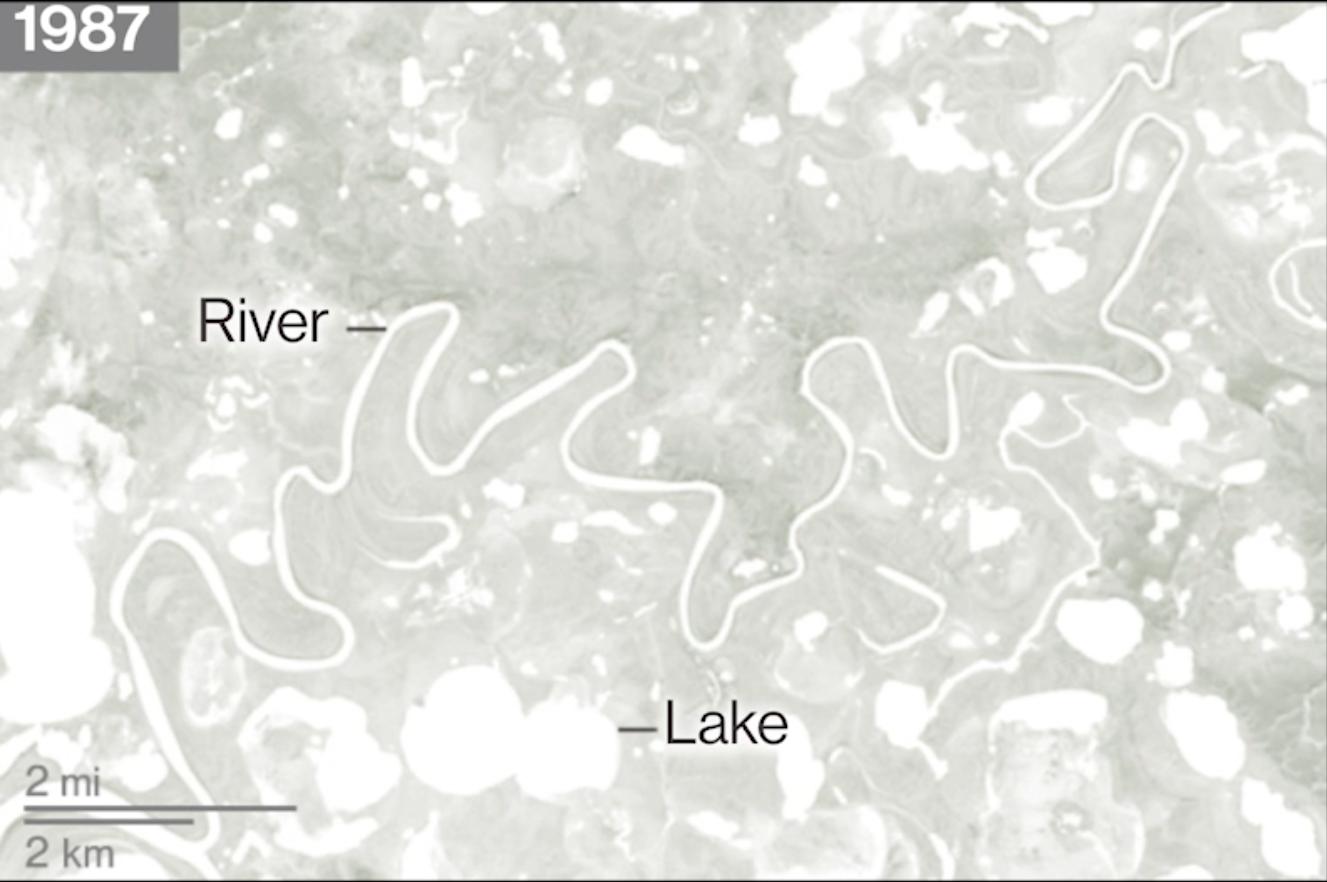

Traditional pastoralists are confronted with increasing competition and possible loss of seasonal pastures as infrastructure such as roads, pipelines, power lines and dams, along with urban development and settlement, interfere with their migration patterns. Their shamanistic and belief system, which stresses respect for the land and its resources, clearly contrasts the notions of living imposed upon them directly through interventions such as the Yamal Megaproject.

Furthermore, several studies have shown that important grazing ranges are lost disproportionately and become unavailable, as development tends to target the same type of rugged terrain for construction. Development has also been shown to impact much greater areas beyond that of the initial footprint, including abandonment of calving grounds by caribou and reindeer. Rugged terrain is crucial to the reindeer herders and their animals for travel, access to dry camp sites and grazing.8 The physical footprint of Bovanenkovo installations is small, but for the three herding units migrating through these bottlenecks, the industrial development resulted in blockage of two out of four possible routes, loss of major grazing areas and subsequent loss of access to at least 18 traditional campsites and one sacred site along their traditional route, which in turn delays the timing of their migratory cycles. Continued industrial development will further compromise the Nenet peoples’ ability to adapt.

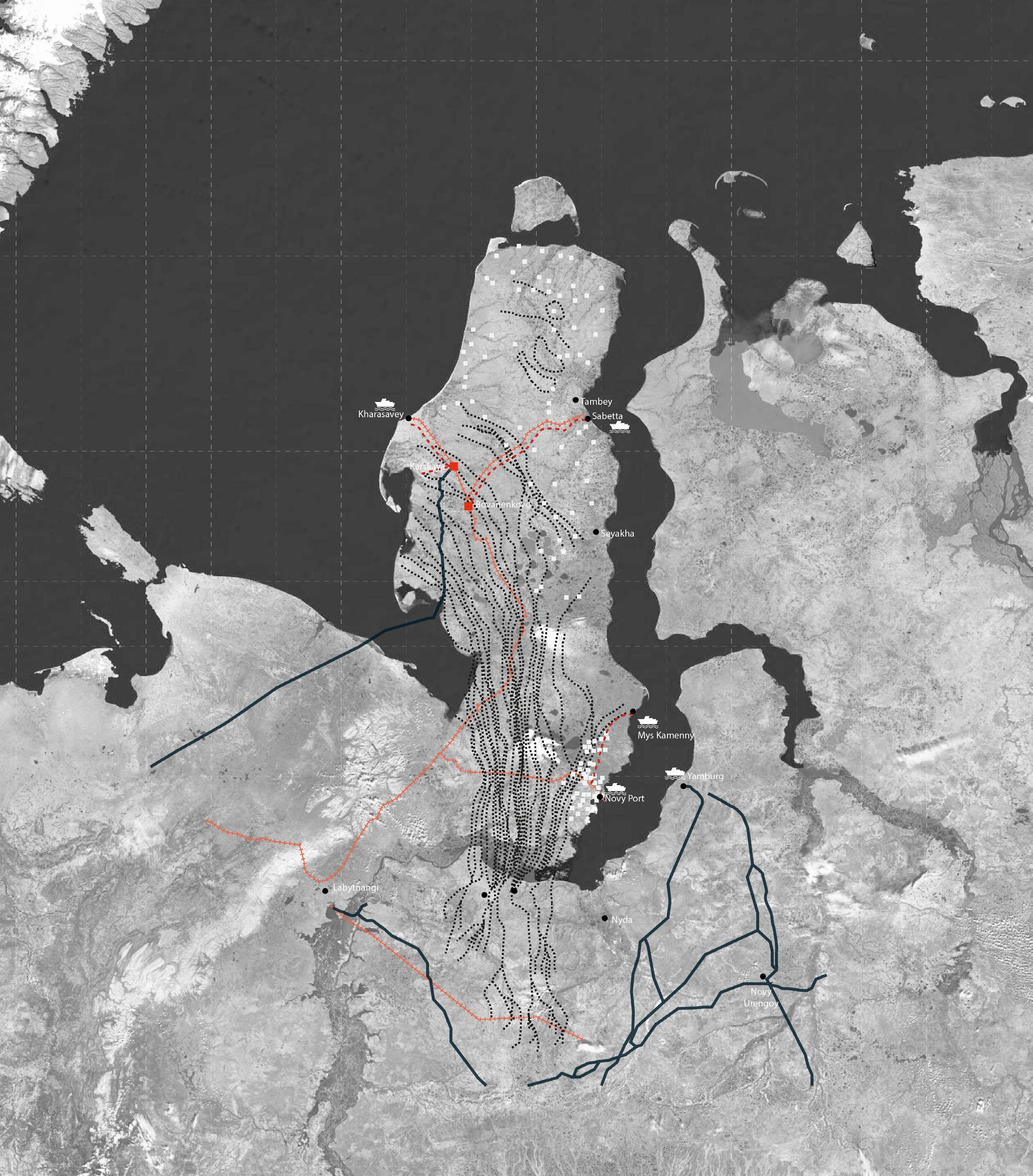

The regional scale

World politics, particularly in the Arctic, has long been about flows of capital, humans and non-humans between cities and across jurisdictional boundaries that are regulated in ad hoc and patch worked ways rather than through the singular workings of absolute sovereignty over clearly bounded territorial spaces.

The Arctic is receiving increasing attention not for the numerous indigenous peoples inhabiting the region but for its rising role in the global energy and mineral supply. Home to the nomadic Nenets people, The Yamal-Nenets Autonomous district holds around 90% of Russia’s and 20% of the world’s gas production.5 Its strategic importance for the Russian Federation and the European energy supply cannot be understated. The industrial development on the Yamal Peninsula commenced in the late 1980s, slowing down after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and subsequent financial crisis during the mid-1990s in Russia. It increased substantially again in 2004 when the world prices for hydrocarbons rose and the government could afford to subsidize a massive port for liquified natural gas tankers, an airport, a powerplant and the use of nuclear-powered icebreakers in the transportation the construction materials. The Bovanenkovo industrial complex is composed of an extensive infrastructure network consisting of roads, gas fields, living quarters, production facilities, power and pipelines, and gravel pits and quarries which interfere with the local wildlife and nomadic communities.6

5 T. Kumpula, B. C. Forbes, and F. Stammler, ‘Remote Sensing and Local Knowledge of Hydrocarbon Exploitation: The Case of Bovanenkovo, Yamal Peninsula, West Siberia, Russia’, ARCTIC , 63.2 (2010), 165–78 (p. 166) <https://doi. org/10.14430/arctic972>. 6 Anna Degteva and Christian Nellemann, ‘Nenets Migration in the Landscape: Impacts of Industrial Development in Yamal Peninsula, Russia’, Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice , 3.1 (2013), 15 (p. 8) <https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-71363-15>.

The human scale

Approximately 15 reindeer herding units travel through the area during summer along 21 migration routes. Reindeer herding among the Nenets people is nowadays organized in large enterprises, formerly as state managed agricultural farms. Each reindeer herding enterprise is composed of several brigades according to the number of the herds. Several herders work together and migrate with their families all year around in a brigade. In addition, there are also a great number of private herders. Many Nenets herders begin their migrations from the wintering areas in the south in mid-late March. It is home to approximately 270,000 reindeer and about 1,000 fully nomadic households, comprising ca. 5,000 nomadic people live on the Yamal peninsula. Herders can move up to 30km on a good winter day. As the snow melts, the distance is often limited to 7km depending on weather, total distance to summer pastures, ground conditions, dynamics and coordination with the migrations of other herders and the ecology of their reindeer.7

Traditional pastoralists are confronted with increasing competition and possible loss of seasonal pastures as infrastructure such as roads, pipelines, power lines and dams, along with urban development and settlement, interfere with their migration patterns. Their shamanistic and belief system, which stresses respect for the land and its resources, clearly contrasts the notions of living imposed upon them directly through interventions such as the Yamal Megaproject.

Furthermore, several studies have shown that important grazing ranges are lost disproportionately and become unavailable, as development tends to target the same type of rugged terrain for construction. Development has also been shown to impact much greater areas beyond that of the initial footprint, including abandonment of calving grounds by caribou and reindeer. Rugged terrain is crucial to the reindeer herders and their animals for travel, access to dry camp sites and grazing.8 The physical footprint of Bovanenkovo installations is small, but for the three herding units migrating through these bottlenecks, the industrial development resulted in blockage of two out of four possible routes, loss of major grazing areas and subsequent loss of access to at least 18 traditional campsites and one sacred site along their traditional route, which in turn delays the timing of their migratory cycles. Continued industrial development will further compromise the Nenet peoples’ ability to adapt.

“White carpet” treatment from Gazprom, the company that operates Bovanenkovo, as the herd crosses the gas field. The geotextile is supposed to make it easier for reindeer bulls to pull the sleighs across the road.