HAVE HORSE, WILL TRAVEL

Key

Analysing

HAVE HORSE, WILL TRAVEL

Key

Analysing

This issue includes the results of our important survey of European Thoroughbred Racehorse Practices. This survey was the first to be conducted on a Europe wide scale, based specifically on the needs of the racehorse.

With responses from over 141 trainers and pre-trainers from nine countries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland (Republic and Northern), Spain and Sweden, the thorough survey demonstrates the level of care and understanding that trainers have for the welfare of the horses in their care.

But what impact will the results of the survey have? The survey was prompted by the review currently being conducted by the European Commission (EC) on animal husbandry, and its specific focus on horses. The EC has engaged its scientific advisors, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), to produce a scientific opinion on the protection of horses, and a technical report on current practices for their keeping.

So first and foremost, the results of the survey will be shared with the likes of the EFSA as well through the European Horse

Network (of which the European Trainers’ Federation is a member). The EHN regularly advises politicians in the European Parliament on equine related issues.

A big thank you to all who took the time to respond to the survey and especially to Dr. Paull Khan who has painstakingly pieced together an extensive article based on the survey results which can be found in this issue of the magazine.

Our cover profile trainer needs little introduction. Now in his 47th season with a training license, Nicky Henderson has won pretty much every major National Hunt race – bar one. As Alysen Miller discovered, a Grand National trophy is missing from the mantlepiece at Seven Barrows.

In this issue, we include a fascinating article on the latest research into the biomechanics of jumping. Biomechanics is the scientific study of the movement of a living body, in this case a racehorse, looking at how muscles, bones, tendons and ligaments all work in sync to produce a specific movement.

Our nutrition feature in this issue explores the role of gut health in racehorse performance, the risks posed by modern feeding practices, and the latest published research including recent field trials carried out on a novel gut supplement containing pre-biotics, digestible fibres, B-vitamins and postbiotics to show how trainers can give their horses a competitive edge.

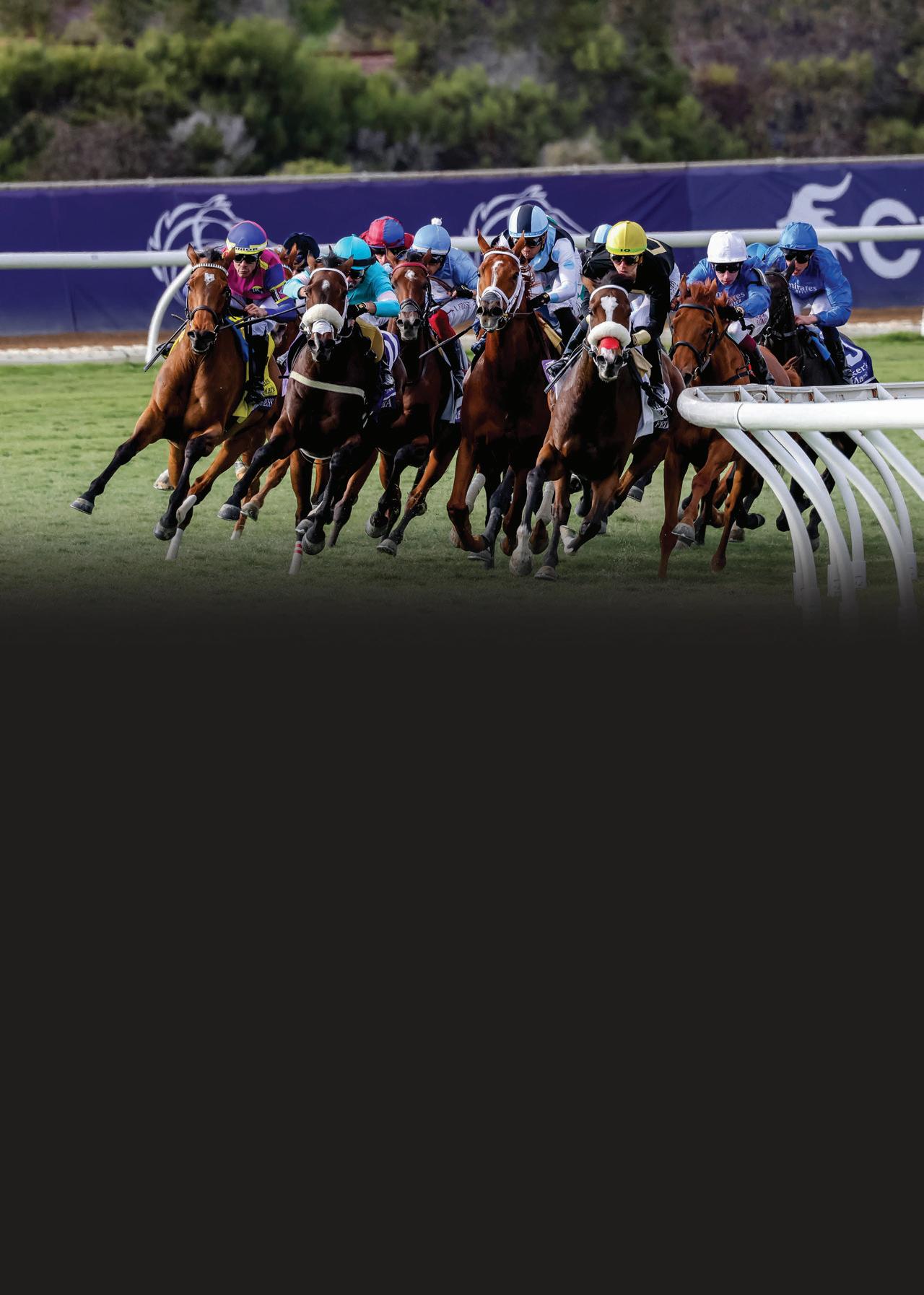

The ‘Have Horse Will Travel’ series focuses on opportunities at the Breeders’ Cup meeting in Del Mar at the end of October. The international festivals in Morocco, Bahrain, Hong Kong, Dubai and opportunities at the Pegasus World Cup next January also come under the spotlight.

For our jumps trainers, we highlight the changes of qualification for Grade 1 Novices’ and Juvenile Hurdle races as well as looking at the Go North Series, which culminates in Finals weekend at Kelso, Musselburgh and Carlisle racecourses in late March.

Wherever your racing takes you this autumn - good luck!

download our current digital editions and access back issues of both European and North American Trainer

06 Cavalor Trainer of the Quarter

Lissa Oliver talks to Eoin McCarthy – who had six winners at the recent Listowel Festival. Quite an achievement for a yard with just 36 horses riding out at present.

08 A vision for victory

Alysen Miller profiles six-time champion trainer Nicky Henderson on his fortyseven seasons at the top table of National Hunt racing.

20 The race starts in the gut

Sorcha O’Connor looks at the new research available for optimising digestive health for peak performance.

30 Have horse, will travel

Lissa Oliver looks at the international racing opportunities that trainers should be targeting this winter.

40 Racing on the edge

Laura Steley reviews the new research perspectives on SDFT and SL injuries in thoroughbreds.

48 Forces in flight

Laura Steley helps us understand how biomechanics and training can optimise a horse’s jumping performance.

56 The results are in!

Paull Khan reports on the results of the survey conducted into the husbandry practices that are adopted in the training of racehorses across Europe.

66 AI in the Equine Sector

David Doherty reports from the 2025 AI in the Equine Sector Conference on the latest advances in AI technology in racing and breeding.

70 Elie Hennau interview

Katherine Ford speaks with France Galop CEO Elie Hennau discussing the way forward for French racing.

74 Diagnostic testing

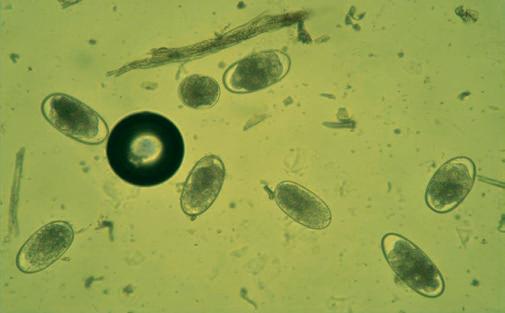

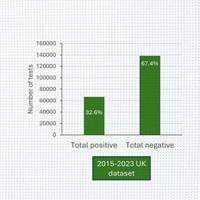

Jacqui Matthews gives top tips on how trainers can develop effective worm control strategies that help safeguard the effectiveness of wormers.

80 A look at ‘Learning Theory’

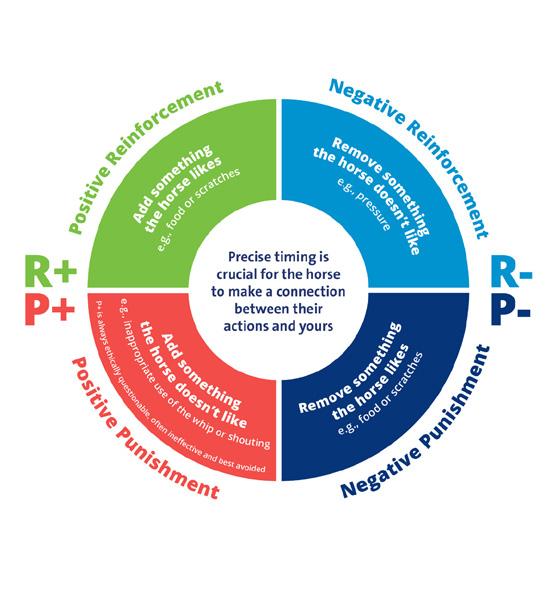

Jackie Zions interviews Sally King and Dr. Katrina Merkies on how learning theory can reduce stress and aid the development of top performers.

Pre-Entry Opens Online October 1

Breeders’ Cup World Championships

14 Grade I Championship Races • Over $34 Million in Purses and Awards

It’s time to take your place among the world’s greats. Pre-entry for the 2025 Breeders’ Cup World Championships opens online October 1 and closes at Noon (PDT), on Monday, October 20. All Breeders’ Cup World Championships races are non-invitational and are open to all thoroughbreds competing around the globe.

Offering purses and awards over $34 million and each race pays through the 10th finish position! Each Breeders’ Cup World Championships starter receives a travel award up to $10,000 for domestic horses and $40,000 for international horses shipping into California.

Enjoy exclusive world-class hospitality on racing’s biggest stage, including premium reserved seating for you and your guests, participant hotel accommodations including a credit for your stay, access to hospitality lounges, executive car service, and invitations to exclusive events.

To pre-enter online beginning October 1 and access the digital Horsemen’s Information Guide, visit members.breederscup.com.

Editorial Director/Publisher

Giles Anderson

Sub-Editor

Nico Jeeves

Design/Production

Damian Browning

Advert Production

Lauren Godfray

Circulation/Website

Lauren Godfray

Advertising Sales

Giles Anderson

Cover Photograph

Georgina Preston

Trainer magazine is published by Anderson & Co Publishing Ltd.

This magazine is distributed for free to all ETF members. Editorial views expressed are not necessarily those of the ETF. Additional copies can be purchased for £8.95 (ex P&P). No part of this publication may be reproduced in any format without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Printed in the European Union

For all editorial and advertising queries please contact:

Anderson & Co. Publishing

Tel: +44 (0) 1380 816777

Fax: +44 (0) 1380 816778

email: info@trainermagazine.com www.trainermagazine.com

Issue 91

Jackie Bellamy- Zions is communications manager at Equine Guelph for the past ten years, Jackie has over 30 years of experience in the horse industry in the capacity of coach, trainer, stable manager, competitor, judge and journalist.

David Doherty is a technology consultant with a background in medicine and nearly four decades of experience using biosensor technologies with elite racing animals. In 2017, he founded the HorseTech Conference at the Royal Veterinary College, London, to advance innovation in equine health and technology.

Katherine Ford was born in Yorkshire where she was raised with ponies, hunting and point to pointing. After completing a degree in languages and the BHA Graduate Development programme, she moved to France for a season with the International Racing Bureau’s Paris office. Three years later she joined French racing channel Equidia’s international department which took her on travels to racecourses from Brazil to Japan, California to Cape Town. She now splits her time between Equidia, Sky Sports Racing’s French coverage and freelance writing and translating, and dreams of future successes for the progeny of her two broodmares.

Paull Khan, PhD. is an international horseracing consultant. He is a member of the Executive Council of the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (the global peak body for thoroughbred racing) and Chief Executive Officer of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation. His other clients include the British Horseracing Authority. Previously, Dr Khan held many senior roles at Weatherbys, including Banking Director and Racing Director.

Prof. Jacqui Matthews qualified as a vet before completing a PhD in parasitology. She worked in academia for >25 years, leading projects valued >£14M. Outputs include >150 peer-reviewed papers, plus patents and lay articles. She is a fellow of the RCVS and Royal Society of Edinburgh and RCVS Specialist in Parasitology.

Alysen Miller is a writer, editor and producer based in London. She has written about racing for publications including The Sunday Times. She launched and produced CNN International’s first dedicated horseracing magazine show, Winning Post. She has ridden on the Flat as an amateur and currently competes in eventing on her retrained racehorse, Southfork.

Sorcha O’Connor graduated with her MVB from University College Dublin in 2017. After six years in equine and mixed practice, she joined Connolly’s Red Mills equine technical support team. Passionate about nutrition and preventative medicine, she has undertaken research in antimicrobial resistance, equine nutrition and hindgut health.

Lissa Oliver lives in Co. Kildare, Ireland and is a regular contributor to The Irish Field and the Australian magazine, Racetrack. Lissa is also the author of several collections of short stories and two novels.

Laura Steley BSc Hons in Equine Sports Science, is the Senior Stud Secretary at Shadwell Stud in Newmarket, alongside being the regular contributor for the Equine Health Update Section in Owner Breeder magazine. She has previously gained invaluable experience within the thoroughbred pre-training and rehabilitation sector, as well as fulfilling the role of an International Racing Data Analyst. Laura has a deep-rooted passion for equine science and feels passionately about applying scientific findings to sustain and improve equine welfare standards.

AIMS and OBJECTIVES of the ETF:

AIMS andOBJECTIVES of theETF:

a) To represent theinterests of allmembertrainers’ associationsinEurope.

a) To represent the interests of all member trainers’ associations in Europe.

b) To liaise with politicaland administrative bodies on behalf of European trainers.

b) To liaise with political and administrative bodies on behalf of European trainers.

c) To exchange information between members for the benefit of European trainers.

c) To exchange information betweenmembers forthe benefitofEuropeantrainers.

d) To provide anetwork of contacts to assist each member to developits policyand services to member trainers.

d) To provide a network of contacts to assist each member to develop its policy and services to member trainers.

Chairmanship:

GuyHeymans (B elgium)

CHAIRMANSHIP: Gavin Hernon (France)

Tel:+32(0)495389140

tel: +33 (0)7 87 16 02 48 email: contact@aedg.fr

Email: heymans1@telenet.be

Vice Chairmanship:

NicolasClément(France)

Tel:+33(0)344572539

Fax:+33(0)344575885

Email:entraineurs.de.galop@wanadoo.fr

VICE CHAIRMANSHIP: Paul Johnson (United Kingdom)

tel: +44 (0) 1488 71719 email: p.johnson@racehorsetrainers.org

Mrs Živa Prunk

Tel: +38640669918

Email: ziva.prunk@gmail.com

Joseph Vana

ITALY

Tel:+42(0)602429629

Ottavio Di Paolo

Email: horova@velka-chuchle.cz

tel: +39 328 355 95 81 email: ottaviodipaolo@gmail.com

Aggeliki Amitsis

Tel:302299081332+

Email: angieamitsis@yahoo.com

SWEDEN

GERMANY

Jessica Long

ErikaMäder

email: jplong@live.se

Tel:+49(0)2151594911

Fax:+49(0)2151590542

Email: trainer-und-jockeys@netcologne.de

Vice Chairmanship:

Christianvon derRecke (Germany)

Tel:+49(02254)845314

Fax:+49(02254)845315

Email: recke@t-online.de

VICE CHAIRMANSHIP: Christian von der Recke (Germany)

tel: +49 171 542 5050 email: recke@t-online.de

Mr Botond Kovács

Email: botond.kovacs@kincsempark.hu

BELGIUM

Agostino Affe

Email: affegaloppo@gmail.com

tel: +32 (0) 495389140 email: heymans1@telenet.be

Geert van Kempen

Mobile: +31 (0)6 204 02 830

Email: renstalvankempen@hotmail.com

GERMANY

Erika Mäder

Are Hyldmo

Mobile: +47 984 16 712

tel: +49 (0) 2151594911

Email: arehyldmo@hotmail.com

www.trainersfederation.eu

Treasu ship:

MichaelGrassick(Ireland)

TREASURERSHIP:

Tel:+353(0)45522981

Mobile:+353(0)872588770

Fax:+353(0)45522982

Feidhlim Cunningham (Ireland)

Email:office@irta.ie

tel: +353 (0) 45522981 email: office@irta.ie

Rupert Arnold

Tel:+44(0)148871719

Fax:+44(0)148873005

Email: r.arnold@racehorsetrainers.org

RUSSIA

Olga Polushkina

Email:p120186@yandex.ru

Birkje Hoorens Van Heyningen

tel: +31 (0) 250 930 016

email: birkjehvh@gmail.com

Jaroslav Brecka

Email: jaroslav.brecka@gmail.com

NORWAY

Tom Lühnenschloss

SWEDEN CarolineMalmborg

mobile: +47 (0) 46445345

Email: caroline@stallmalmborg.se

email: lynet3108@yahoo.no

TRAINER OF THE QUARTER

The Cavalor Trainer of the Quarter award has been won by Eoin McCarthy. McCarthy and his team will receive a Cavalor voucher of €1,000 for Cavalor supplements and care products as well as a consultation with one of their senior product specialists.

WORDS: LISSA OLIVER PHOTOGRAPHY: HEALY RACING

Our Cavalor Trainer of the Quarter, Eoin McCarthy, was selected not for one outstanding performance but for six! McCarthy sent out the six winners, plus four placed horses at his local meeting, the prestigious Listowel Festival, and in doing so topped the Leading Trainer table, ahead of such powerhouses as Willie Mullins. Quite an achievement for a yard with 36 horses riding out at present.

McCarthy has been training National Hunt, Point-to-Point and Flat horses since 2012, as well as providing pre-training and breaking, from his family-run yard in Templethea. The yard sits in the tranquil countryside of County Limerick in the West of Ireland and while McCarthy says he has “the basic” in terms of

a four-furlong (800m) woodchip gallop and arena, less run-ofthe-mill is the access to a river for the horses to walk through and 40-acres of forest with a good mile of trekking paths, keeping his horses fit in both body and mind.

As a local trainer, Listowel is of huge importance to McCarthy, “it’s like a blood bank, if you don’t perform well at the meeting others do and they’re soaking up new owners.” Horses are individuals, but McCarthy has shown he can have them all ready for that one important week. “It’s not an overly big yard so it’s very easy to keep an eye on them, I took some horses to work at the Curragh on The Old Vic gallop, while others never went away and did everything here, you get to know what works best for each horse.”

LEFT: Fast Felix and Thomas O’Connor win the Adare Manor Opportunity Handicap Hurdle — the second of six winners at the week-long 2025 Listowel Harvest Festival for trainer Eoin McCarthy.

The results were Carla’s Pet opening the meeting with a win, a double the following day with Shadow Paddy and Fast Felix, and topping it all the following afternoon the first treble of McCarthy’s career with Ollie La Ba Ba, Regards To Rose and Tropical Image. Throw into the mix the placed runners Moon Sky, Wholelotofbusiness, Jekiki and Elusive Ogie and it was something of a bonanza for McCarthy.

“It’s something that you only dream of, it’s unbelievable,” he admits. “The amount of people still coming over congratulating me, it’s very special as racing moves forward so quick, yesterday’s race forgotten. Without the owners and staff it won’t work, and my family are working alongside me, too.

Trainer

“I’m riding out every lot each morning, it’s my favourite part, I love being hands on. It might sound silly, but I only train because I love horses, I love working with them, and I really enjoy it when the three-year-olds start coming in and getting them jumping.

and

“I don’t look at it like a business, if a horse takes two years to come along so be it, let him. It’s probably not the best business model and it takes time, but it’s beginning to pay off now and we’re going in the right direction.”

CAVALOR FREEBUTE & CAVALOR LACTATEC

Cavalor FreeBute supports muscles and joints for improved mobility. FreeBute will offer relief from discomfort in the recovery process after heavy effort.

Cavalor LactaTec is a complete supplement that supports muscle activity, stimulates muscle recovery and prevents stiffness, damage, and fatigue in a variety of ways.

“I’VE BEEN VERY, VERY LUCKY... IT’S BEEN FUN. AND IT’S STILL FUN. AND I INTEND TO GO ON HAVING FUN.”

Of course, they’d never let me have a driving licence,” chortles Nicky Henderson. We are in his jeep hurtling across the Lambourn Downs on our way to watch first lot get put through their paces. I reach reflexively for my seatbelt.

“I drive around here [‘here’ being, naturally, the historic Seven Barrows] but I wouldn’t see a car coming until it’s 50 yards away. Which is not a very safe way of driving,” he admits.

Henderson suffers from macular degeneration – an eye disease that affects central vision. People with macular degeneration can’t see things that are directly in front of them. Henderson started experiencing blurred vision 10 years ago. Since then, his eyesight has become progressively worse. “When you lose those these things gradually, you don’t notice it to start with,” he says.

While living with the condition certainly comes with challenges, it cannot be said that Henderson’s failing eyesight has dulled the six-time champion trainer’s enthusiasm for the game. “There are a lot of things I can’t do, and there are definitely things that I miss,” he explains. “The worst thing is not being able to see people’s faces. I can’t really read without putting it in great big letters [on his iPad], and even then it still doesn’t work particularly well. I read what I have to read.”

This includes reading the Racing Post cover to cover every day. “Well, the greyhounds get a miss,” he says. “But I don’t read a daily newspaper. I’m probably the only person you’ve ever written an article about who will never read it,” he quips. “But I can see horses. That’s the one thing I can see. Once they’re out, I know exactly who’s who and what’s where. If that was a human, I couldn’t tell you who it was if I didn’t know them at that distance. But I can see the whole horse.”

There is little that hasn’t already been written about Nicholas John Henderson LVO OBE, obviating the need for him to read my humble contribution to the canon. He is the son of Johnny Henderson, a banker and racehorse owner (not to mention

aide-de-camp to Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, whom he tapped to be Nicky’s godfather) who was instrumental in keeping Cheltenham Racecourse out of the clutches of property developers when, in 1963, he and other Jockey Club members formed Racecourse Holdings Trust, a non-profit-making organisation that raised £240,000 (approximately £4.4 million today) to purchase the racecourse and safeguard its future, and that of the Cheltenham Festival.

Henderson père’s name was added to the title of the Grand Annual Handicap Chase in 2005. It had been expected that Henderson fils would follow his father’s well-healed footsteps into pinstripe suited respectability. “And I did, in a roundabout way,” he says. He spent a year in the Sydney offices of aristocratic private stockbroker Cazenove. He had been “mucking about in Western Australia with sheep and cattle and horses” when he was summoned back to London to start his City career. “I didn’t like the idea of it, so they came up with a great idea,” he says. “I could go back to Australia and be in their Sydney office, which had two people in it. That was going to suit me an awful lot better than sitting in London. So off I went, back to Australia, until it was eventually time to go back to London and get serious.” He lasted a year and a half. “I just couldn’t sit behind a desk and stare at a wall,” he says.

Instead, he became assistant trainer to the legendary Fred Winter. “I was at Fred’s for five years,” he says. “Then it was either a matter of going elsewhere to see if I could learn something else or kicking off [on my own] and seeing what happened.” So the legend goes, in 1978 he was at the pub when he agreed to purchase Windsor House Stables from Roger Charlton. “We just dreamt it up one night. Roger was going to go and be Jeremy Tree’s assistant and he said, ‘Well, why don’t you buy my place?’” he reminisces. “So he went off to Jeremy’s and I went down the road from Uplands, which was where Fred was. We had about five horses to start with. I hadn’t got a clue what we were doing, but it sort of got off the ground, miraculously.”

The Windsor House Stables purchase came with two amenities – an equine swimming pool (something of a novelty at the time) and Head Lad Corky Browne. “Roger said to me, ‘I’ve got this amazing head lad who you really want to take on.’” Corky would become Henderson’s right-hand man and remain an integral part of the team for more than four decades. He eventually retired in 2019.

“And then somebody said to me, ‘I’ve got a really good travelling head lad,’ which was Johnny Worrall,” Henderson continues. “And there was only one other person we needed: Jimmy Nolan, who used to ride for Fulke Walwyn. So I had the best head lad you could have, the best travelling head lad you could have, and a really good rider in Jimmy.”

The second half of the twentieth century was a golden age for National Hunt trainers in Lambourn. “There was Fred and Fulke, and then Richard Head and Jenny Pitman came along later,” he says. “They were great, legendary, men that you just looked up to and spoke to very quietly, if required to speak. We had such enormous awe and respect for those guys. They were icons. They were gods.”

Now Nicky Henderson is one of those icons. His accolades include nine Champion Hurdles and six Champion Chases. Amongst currently active trainers only Willie Mullins has won more races at the Cheltenham Festival than Henderson, making him Britain’s most successful trainer at the Festival. His encyclopaedic list of winners runs from Altior to Zongalero, the latter of whom was second in the Grand National in Henderson’s first year as a trainer. “A horse like him comes along and you nearly win the Grand National in your first year… Well, that would have been daft,” says Henderson. “Fred Winter did it, incidentally. But to come second in the Grand National in our first ever year? That’s how lucky you can be,” he says self-deprecatingly.

I put it to him that Napoleon famously said he’d rather have lucky generals than good ones. “I don’t think Monty would appreciate that!” Henderson laughs. Monty – Field Marshal Montgomery – and Henderson maintained a correspondence throughout the general’s life. “He was a fascinating man, and we got on very well. We had some very funny times together. We did write to each other a lot. But if I had said, ‘God, you were lucky,’ I think he’d think was a bit more skill in it than that!”

Zongalero’s second place in the 1979 Grand National – beaten by two lengths by Rubstic, the smallest horse in the race – has yet to be bettered by a Seven Barrows runner. But Henderson remains grateful for his first flag bearer. “He was the first horse I was ever asked to train,” he remembers. “He was quite a well-known horse. Tom Jones – who trained him – was becoming more and more of a flat trainer, so he was giving up the jumpers. He had this great big thing and he thought it was better for him to go somewhere else and, blow me down, I got this amazing letter one day – before we’d even opened the yard – saying, ‘I’ve got this horse. I’d like you to train it for me.’ I thought he was mad. Anyway, Zongalero came along with a few others, and, you know, the bits and pieces suddenly turned up and it sort of got the ball rolling. But I see him as the first great horse.”

If Zongalero was the first great horse, he certainly was not the last. Henderson’s current stable stars include Jonbon, Constitution Hill, Sir Gino, Lulamba and Jango Baie. “Those top horses are as good a string as anyone could have,” says Henderson. “They’re all genuine Group 1 horses, the top of their categories.”

But after four decades at the top of the game, does Henderson ever worry about the Young Turks snapping at his heels? “There are a lot of very good young trainers coming through, particularly National Hunt,” he says. “I think we’re probably all competitive. I know I am. You wouldn’t do this if you didn’t want to win. There’s no point in going out there thinking, ‘I’m just going to do this for fun.’”

So what’s the secret to his longevity? “There are two things you need: good horses and good people. You’ve got to have an awful lot of good people,” he says firmly. “That is essential.” He is quick to pay credit to Charlie Morlock –whom he describes in Montgomerian terms as his aide-de-camp – and Assistant Trainer George Daly as well as his wife, Sophie. “I know you’re trying to write about me,” he says, breaking the fourth wall. “But it’s not about me. Gosh, no. It’s the whole operation.

“We were talking about eyes,” he continues. “I have actually got three different pairs of eyes,” he says, “in Charlie, George and Sophie. I would be in serious trouble without them. They’re vital.” Morlock previously assisted Henderson for 10 years before striking off to train in his own name. “And he did fine,” says Nicky. “But it was a mutual idea that we get back together again. And he’s been here for God knows how long this time. George is my assistant trainer, he’s Charlie’s aide-de-camp. We just do everything together.” It all sounds a bit like being a field marshal, I suggest. “I suppose so,” he says. “It has to be reasonably regimented with that number of people and that number of horses. We pull out at 7.30am every single morning, 365 days of the year, except Sundays.” Every evening Henderson goes round half the yard. “I’m feeling their legs, looking at them. ‘You’ve got lighter,’ ‘You’ve put weight on,’ ‘I don’t like your leg,’ ‘You look well,’ ‘You look shocking.’ Not many yards would do evening stables like we do here. It’s still very old fashioned.”

Despite his insistence on his antiquity, Henderson is not immune to the proliferation of technology that has swept through the racing industry in the past decade. “It’s got its advantages,” he admits. “We use heart rate monitors. There is blood testing and scoping, all the modern technology. It filters through.” But there are limits to his embrace of technology: “It’s not like I’m still going to school like these guys are, or have been over to Australia and America to learn all the new technology they have over there that you can bring to this country. We’ll pick it up somewhere along the line,” he says. Henderson has also revealed an unexpected gift for social media. (“I hate it,” he says.) And yet few among us will ever look at a photo of a printed page of Calibri the same way again.

In the course of researching this profile I managed to turn up a news report from 1979 (written by one Brough Scott) that describes Henderson’s training as showing “a mastery and skill beyond his years.” It is submitted that, more than four decades later, the reverse is true: the septuagenarian Henderson trains with an energy and enthusiasm that belies his age. As Henderson looks ahead to yet another National Hunt season – his 47th – there is one prize that eludes him: the (English) Grand National. “We’ve won all the Champion Chases and Champion Hurdles and Gold Cups, a couple of King Georges. I think most of them have got ticks by them,” he says. “But a Grand National is the obvious thing [that’s missing].

Fallen Angel winning the Group 1 Matron Stakes at Leopardstown. Congratulations to trainer Karl Burke, owners Wathnan Racing and all connections involved.

“Since

- Karl Burke

“Embarrassingly, there are no Grand Nationals [in his trophy cabinet] whatsoever. Except for the American, which I really can’t count because it’s a two-and-a-halfmile hurdle race.” The obvious candidate to capture Henderson’s white whale is Hyland. “He ran in it last year and I think he would have probably grown up from the experience. And I would think it’s probably on his agenda this season.” One can’t help but hope that Henderson will get to see a Seven Barrows runner crossing the winning post in first place at Aintree, even if he has to watch it on TV. “One thing I don’t see particularly well is on a racecourse. I can’t see even with binoculars,” he says.

With Henderson’s eyesight failing it’s tempting to think of Ludwig van Beethoven, who produced arguably his greatest works when completely deaf. Even as he rages against the dying of the light, Henderson has no intention of calling time on his training career. “I’m first to admit it, I’ve been very, very lucky. But we’ve done our best to make the most of it, and it’s been fun. And it’s still fun. And I intend to go on having fun.”

“The horses seem to find the products palatable and since using the brand from the start of 2024, we had a record-breaking season.

After kicking off 2025 well and adding a first international winner to the CV we couldn’t recommend Cavalor’s products enough and will continue to use them.”

Tom Clover Racehorse trainer

Introduction

We all know that winning races depends on far more than what happens on the day at the track. The health, fitness, and mentality of a racehorse are built long before race day. Increasingly, science tells us that one of the most powerful drivers of performance is hidden inside the horse: the gut. Understanding this hidden half of the body is key to understanding health and disease.

Gut health is central not only to digestion but also to energy supply, recovery, immunity, behaviour, and resilience against disease (O’Brien et al ., 2022). When the gut is compromised, the impact is felt in poor performance, poor recovery, and increased veterinary bills. On the other hand, when the gut is healthy, horses can perform at their best more consistently.

In this article, we explore the role of gut health in racehorse performance, the risks posed by modern feeding practices, and the latest published research including recent field trials carried out on a novel gut supplement containing pre-biotics, digestible fibres, B-vitamins and postbiotics to show how trainers can give their horses a competitive edge (O’Connor and Mulligan, 2024).

Unlike us, horses can digest fibre. Up to 70% of a racehorse’s energy can come from the fermentation of fibre in the hindgut, where microbes break it down into volatile fatty acids that fuel endurance and sustained performance. A healthy hindgut microbiome also contributes to the synthesis of B-vitamins (vital for energy metabolism and red blood cell production), it supports immune function and plays a role in hormone balance and even a horse’s behaviour (Kauter et al., 2019). Although we are only beginning to understand the many functions of the horse’s microbiome, we do know how to fuel it with a diversified, fibre-based diet (Raspa et al., 2024).

Recent research highlights how much gut health influences a horse’s career. The Well Foal Study at the University of Surrey followed thoroughbred foals from birth to three years of age and found that those with more diverse gut microbiota early in life experienced fewer illnesses and went on to have more successful racing careers (Leng et al., 2024). This connection between gut diversity, health, and future performance directly shows the importance of looking after gut health from the very start of a racehorse’s life (Fig. 1).

For trainers, the practical implication is clear: a horse’s ability to perform at its peak depends on the stability and balance of its gut microbiome. A compromised gut means reduced energy extraction, more risk of conditions like colic and laminitis, and behavioural changes such as nervousness or lack of focus (Boucher et al., 2024).

The natural diet of the horse is based on grazing and high-fibre forages. Modern training, however, demands higher energy intake than forage alone can provide. This has led to the widespread use of cereals and high-starch concentrates. While effective at delivering energy quickly, they also pose risks when fed in large amounts.

Studies show that feeding more than 2.5–5kg of cereal per day increases the risk of colic nearly fivefold. Horses fed more than 2.7kg of oats daily were almost six times more likely to colic (Tinker et al., 1997; Hudson et al., 2001). These figures are illustrated in Fig. 2 below.

2.5 – 5 kg of cereal per day = 4.8 x colic risk

>5 kg of cereal per day = 6.3 x colic risk

2.7 kg of oats per day = 5.9 x colic risk

Fig. 2: Concentrate amount versus colic risk.

We had one horse who was underweight and looked very dull in his coat. I was struggling to get the work in to him so I could then run him. Clinical tests all came back fine so we changed his feed and added in NUTRI-GARD. The change in the horse was extraordinary, gained condition, top line and even in depth of winter had a shine to his coat. The horse went on to win two competitive races. I could not recommend NUTRI-GARD more.

PAUL NICHOLLS

Scientifically advanced gut supplement formulated to support stomach and hindgut health and maintain overall digestive function.

Postbiotics to promote optimal gut and immune health

Prebiotics to support a healthy hindgut microbiome

Added B-vitamins to promote appetite and optimise feed utilisation

Pectin helps to buffer stomach acid

Formulated with amino acids, L-threonine and DL-methionine to support a healthy lining in the digestive tract

Contains oat fibres, naturally rich in beta-glucans

FOR Digestive health

UK: Adam Johnson T: +44 7860 771063 IRE: Nicole Groyer +353 83 477 3873 Email: info@foranequine.com

Similarly, research on equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) shows that feeding more than 2g of starch per kilogram of bodyweight per meal raises the risk of squamous ulcers by over threefold (Luthersson et al., 2009). This is illustrated in terms of scoops in Fig. 3 below (based on average starch levels in a racehorse cube or muesli).

For a 500kg horse, per meal maximum amount in Stubbs scoops, would be the equivalent of:

1 X 1.5

Fig.3: Safe starch volume per meal based on average starch content of compound racehorse feeds.

Why? Because the horse’s digestive anatomy is poorly adapted to digest large starch meals. Horses produce no amylase in their saliva, and their stomach and small intestine, the sites of starch digestion, are relatively small. When there is an overload of cereal, the starch bypasses these sections and enters the hindgut, where it disrupts microbial fermentation (Julliand & Grimm, 2017). The result is increased acidity, microbial imbalance (dysbiosis), and a cascade of problems ranging from ulcers and colic to poor recovery and unpredictable behaviour (Bulmer et al., 2019).

On top of diet, the stresses of a modern racehorse’s life: transport, intense training, and routine veterinary interventions put further pressure on the microbiome. Each of these factors can disrupt gut balance, setting the stage for both health issues and reduced performance (Mach et al., 2020).

Despite these risks, trainers have good tools to support gut health. The first step is to respect the horse’s natural digestive design:

• Forage first: Provide ad lib hay or haylage where possible to keep the digestive system functioning as nature intended. Offering at least a small bit of hay before the morning hard feed has recently been shown to slow gastric emptying meaning a slower, steadier arrival of grain to the gut to allow for better digestion (Jensen et al ., 2025). This small amount of hay can create a fibrous mat in the stomach that acts as a buffer against gastric acid. This reduces the risk of acid splash onto the more sensitive squamous region of the stomach lining, thereby helping to protect against ulceration.

• Small, frequent meals: Avoid overloading the stomach and small intestine with large concentrate feeds. Horses are trickle feeders, designed to eat little and often.

• Controlled starch intake: Keep starch levels per meal controlled as described in Fig. 2 to not overwhelm the digestive capacity of the gut.

• Consistency: Avoid sudden changes in feed or forage sources, which can disrupt microbial populations. The horse’s digestive system needs a time period of at least 10-14 days to adjust to a change in their diet.

Beyond feeding management, nutritional science has delivered additional aids. These should only be considered once the main dietary and forage management is in order.

• Prebiotics: Specific fibres that serve as food for beneficial microbes and help support microbial balance.

• Probiotics: Such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (a yeast proven to improve fibre digestion), or Saccharomyces boulardii can stabilise the hindgut in horses on high-starch diets.

• Postbiotics: More recently, attention has turned to these beneficial compounds produced during fermentation, which can positively influence gut function and whole-body health.

TARGETED AT

Æ Digestive upsets or hind gut acidity

Æ Those with loose droppings

Æ Those that have been on antibiotics

Æ Travelling or competing horses

Æ Sick horses or those on box rest

Æ Those receiving low amounts of fibre

Æ Scouring foals (consult your vet)

Æ Underweight horses

A unique support package (prebiotics, probiotics and postbiotics) for the horse’s microbiome to help promote optimum gut health

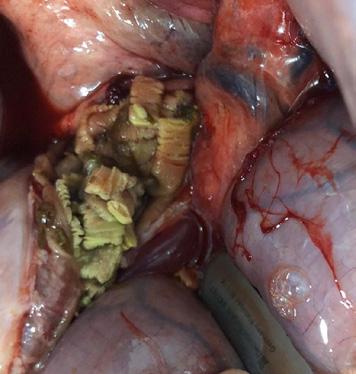

Recent field research involving thoroughbreds in training has provided new evidence on how targeted nutritional support can shape the gut environment. A novel gut supplement, a nutritional combination containing prebiotics, digestible fibres, B-vitamins, and a fermented yeast postbiotic was trialled on 34 thoroughbreds in training over an eight-week period. The horses in the trial receiving this supplement showed a significant reduction in faecal pH compared to the control group as shown in Fig. 4, indicating a healthier, more stable hindgut environment (O’Connor and Mulligan, 2024).

Why does this matter? Faecal pH has been shown as a practical measure for assessing the condition of the rest of the hindgut (Costa et al , 2015). High acidity (low pH) in the hindgut signals excess starch fermentation and an increased risk of acidosis, colic, and poor nutrient absorption. By reducing faecal pH, the supplement supported a more balanced microbial population and more efficient fibre digestion.

For trainers, the benefits of a more stable hindgut:

• Consistent energy supply: Better fibre fermentation means a more reliable source of slow-release energy, supporting stamina.

• Reduced digestive upset: Lower risk of colic, acidosis, loose droppings, etc.

• Improved recovery: A healthier gut environment supports nutrient absorption and immune resilience.

• Mental focus: Balanced microbiota have been linked to calmer behaviour and reduced stress responses.

This research positions postbiotics as a promising new tool in equine nutrition. While probiotics deliver live organisms and prebiotics provide fuel for the microbiome, postbiotics are the beneficial by-products themselves. They can modulate inflammation, support immunity, and stabilise the gut environment without the storage and survival challenges associated with live probiotics (Valigura et al., 2021).

While supplements are valuable, they are only one small piece of the horse’s diet. Trainers should consider gut health as a wholeyard management issue. Consistency of forage supply is key. Sudden changes in hay or haylage batches can disrupt microbial populations. Hydration must be monitored closely, as dehydration increases the risk of impaction colic. Stress management, from minimising unnecessary transport to keeping consistent training plans and providing adequate turnout or downtime, also play key roles in keeping the gut stable.

Veterinary practices should also be considered. Antibiotics, while sometimes necessary, are known to disrupt the gut microbiome for months after use. Avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use and working with vets to target treatments carefully will help protect long-term gut health and performance. The gut microbiome is made up of thousands of bacteria and other microbes that can be destroyed by an antibiotic course and may take months to recover. Antibiotics should only be used when truly necessary. When they are required, ensure the horse is on a high-quality, fibre-rich diet to help keep the gut supported during this stressful period (Collinet et al., 2021).

DID YOU KNOW?

A horse cannot consistently perform to the best of its ability with a gut flora imbalance. ProSol is a unique probiotic solution tailored to each horse, containing live beneficial bacteria harvested from the horse’s own faecal sample, which helps to restore gut flora PLUS the IEC has a bacterial cryopreservation service to preserve these bacteria for the horse’s lifetime –providing a safety net for your horses’ lifetime.

Using ProSol ensures your horses gut flora is healthy thereby helping to increase immunity, prevent disease & ensure consistent performance.

I have been using the ProSol probiotic service for some time and I appreciate its innovative concept and the fact that it’s a natural product.

It has become an important tool for training my racehorses and maintaining their wellbeing.

ProSol contains only the horse’s own beneficial bacteria suspended in sterile water.

Contact the Irish Equine Centre to talk to our experienced microbiologists who will formulate the probiotic unique to your horse.

IRISH EQUINE CENTRE, Johnstown, Naas, County Kildare, Ireland +353 (0)45 866 266 • microlab@irishequinecentre.ie • www.irishequinecentre.ie

Equine microbiome research is still in its early stages, but the message is already clear, gut health is tightly connected to race performance. Trainers who prioritise digestive stability through smart feeding, careful management, and targeted nutritional support will not only reduce veterinary costs but also gain a competitive advantage on the track.

The next generation of supplements, including those using postbiotic technology, offers exciting potential to further support racehorses in training. By nurturing a healthier hindgut environment, these tools can help horses get more from their feed, recover faster, and maintain focus under the pressures of racing.

The race truly does start in the gut. By trusting and supporting that hidden engine, trainers can help their horses reach the finish line stronger, healthier, and more consistent than ever.

The gut microbiome of a foal as early as one month old plays a key role in shaping its future health and performance. The foal begins its colonisation through contact with the microbiota of the mare’s vaginal and skin surfaces and its surrounding environments. Its gut microbiome reaches a relatively stable population by approximately 60 days in age. For this reason, sourcing well-reared, high-quality stock is essential to give young horses the best start. A healthy microbiome should be supported throughout the racehorse’s career to give him the best chance of success.

For hundreds of years, the thoroughbred industry has focused on genetics, breeding from elite bloodlines to produce the fastest, strongest, and most resilient horses. Emerging research, however, suggests another layer of inheritance that may have been overlooked. A foal acquires much of its gut microbiota from its dam, meaning these microbes could prove just as influential as pedigree in determining future health and performance.

References:

• Boucher, L., Leduc, L., Leclère, M. & Costa, M.C. (2024) ‘Current understanding of equine gut dysbiosis and microbiota manipulation techniques: comparison with current knowledge in other species’, Animals (Basel), 14(5), p.758. doi:10.3390/ani14050758.

• Bulmer, L.S., Murray, J.A., Burns, N.M. et al. (2019) ‘High-starch diets alter equine faecal microbiota and increase behavioural reactivity’, Scientific Reports, 9(1), p.18621. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54039-8.

• Collinet, A., Grimm, P., Julliand, S. & Julliand, V. (2021) ‘Sequential modulation of the equine fecal microbiota and fibrolytic capacity following two consecutive abrupt dietary changes and bacterial supplementation’, Animals (Basel), 11(5), p.1278. doi:10.3390/ani11051278.

• Costa, M.C., Silva, G., Ramos, R.V. et al. (2015) ‘Characterization and comparison of the bacterial microbiota in different gastrointestinal tract compartments in horses’, Veterinary Journal, 205(1), pp.74–80. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.03.018.

• Hudson, J.M., Cohen, N.D., Gibbs, P.G. & Thompson, J.A. (2001) ‘Feeding practices associated with colic in horses’, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 219(10), pp.1419–1425. doi:10.2460/ javma.2001.219.1419.

• Jensen RB, Walslag IH, Marcussen C, Thorringer NW, Junghans P, Nyquist NF. The effect of feeding order of forage and oats on metabolic and digestive responses related to gastric emptying in horses. Journal of Animal Science. 103:skae368. doi: 10.1093/jas/skae368. PMID: 39656737; PMCID: PMC11747703.

• Julliand, V. & Grimm, P. (2017) ‘The impact of diet on the hindgut microbiome’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 52, pp.23–28. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2017.03.002.

• Kauter, A., Epping, L., Semmler, T. et al. (2019) ‘The gut microbiome of horses: current research on equine enteral microbiota and future perspectives’, Animal Microbiome, 1(1), p.14. doi:10.1186/s42523-019-0013-3.

The gut microbiome of a foal as early as one month old plays a key role in shaping its future health and performance.

• Leng, J., Moller-Levet, C., Mansergh, R.I. et al. (2024) ‘Early-life gut bacterial community structure predicts disease risk and athletic performance in horses bred for racing’, Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.17124. doi:10.1038/ s41598-024-64657-6.

• Luthersson, N., Nielsen, K.H., Harris, P. & Parkin, T.D. (2009) ‘Risk factors associated with equine gastric ulceration syndrome (EGUS) in 201 horses in Denmark’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 41(7), pp.625–630. doi:10.2746/042516409x441929.

• Mach, N., Ruet, A., Clark, A. et al. (2020) ‘Priming for welfare: gut microbiota is associated with equitation conditions and behavior in horse athletes’, Scientific Reports, 10(1), p.8311. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65444-9.

• O’Brien, M.T., O’Sullivan, O., Claesson, M.J. & Cotter, P.D. (2022) ‘The athlete gut microbiome and its relevance to health and performance: a review’, Sports Medicine, 52(Suppl 1), pp.119–128. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01785-x.

• O’Connor, S. & Mulligan, F. (2024) ‘A field study of a novel nutritional combination containing prebiotics, digestible fibres, B-vitamins, and postbiotics’ effects on equine gut acidity’, presented at the 28th Congress of the European Society of Veterinary and Comparative Nutrition, Dublin, 9–10 Sept.

• Raspa, F., Vervuert, I., Capucchio, M.T. et al. A high-starch vs. high-fibre diet: effects on the gut environment of the different intestinal compartments of the horse digestive tract. BMC Veterinary Research 18, 187 (2022). www. doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03289-2

• Tinker, M.K., White, N.A., Lessard, P. et al. (1997) ‘Prospective study of equine colic risk factors’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 29(6), pp.454–458. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb03158.x.

• Valigura, H.C., Leatherwood, J.L., Martinez, R.E., Norton, S.A. & WhiteSpringer, S.H. (2021) ‘Dietary supplementation of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product attenuates exercise-induced stress markers in young horses’, Journal of Animal Science, 99(8), skab199. doi:10.1093/jas/skab199.

There is no doubt that training and racing place stress on the horse’s digestive system and mitigating that stress is key if horses are to perform at their best. Poor health means lost training time which ultimately impacts race performance and so it’s in everyone’s interest to feed sympathetically.

Often undervalued as an energy source, fibre can actually provide a significant amount of energy for the working horse and recent studies have shown that high fibre diets are not a barrier to performance. Research has shown that horses in training fed a combination of chopped and pelleted alfalfa at 80% of the bucket feed with just 20% oats performed just as well as those fed cereals alone, demonstrating that high levels of cereals are not required to support high intensity exercise (Martin et al., 2021).

A high fibre feed can provide plenty of energy especially when combined with other energy dense ingredients such as oil. These types of feed provide czomparable energy levels to a traditional racehorse mix or cube but with up to 10 times less starch making them particularly useful for those prone to ulcers.

Studies have shown that performance horses can utilise fibre as an energy source – the key is ensuring there is sufficient, high quality fibre in the ration for the horse to make use of. The amount of energy supplied depends on the digestibility of the fibre source which is influenced by plant type, environmental conditions and the plant’s maturity at the time of harvest. The more mature a plant, the less digestible it will be and therefore the less energy it will provide, so choosing an early cut forage is usually a good place to start when it comes to feeding the performance horse.

When it comes to choosing a suitable fibre feed to go in the bucket, the type used is important to consider. Some so-called performance products contain straw which is sun-dried and contains many more mould spores – not something we would suggest is ideal for maximising respiratory health for horses in higher levels of work.

Alfalfa, grass and sugar beet are examples of feedstuffs that contain highly digestible fibre and so are much better suited to the performance horse. Alfalfa and grass in the Dengie range are precision dried making them very clean sources of fibre – studies have shown alfalfa pellets were better than steamed hay for horses with respiratory health issues.

Super-fit performance horses can have reduced appetites and in these situations, a pelleted fibre feed is a way of continuing with a high fibre ration in a more concentrated volume of feed. Whilst some chopped fibre is still good for encouraging chew time, it can be mixed with feeds like alfalfa pellets to reduce the amount of feed the horse needs to eat.

Feeding sympathetically is key to your horse’s health and therefore performance. Our team of nutritionists can help you to maximise your horse’s potential.

The 42nd running of the Breeders’ Cup World Championships will be held for a fourth time in Del Mar, California on Friday 31st October and Saturday 1st November. Consisting of 14 Grade 1 races with purses and awards totalling more than $34m (€29m/£25m).

Each race pays prize money through to tenth position. Each international starter receives a travel award of $40k for horses shipping directly from their home country to California.

The “win and you’re in” series consists of 69 of the best races from around the world, from June to October, awarding each winner an automatic and free entry into the Breeders’ Cup World Championships.

Pre-entries open online from October 1st (via members.breederscup.com) and close at noon (pacific time) on Monday 20th October. All races are noninvitational and open to all thoroughbreds.

With an emphasis on quality Purebred Arabian racing, the international races staged in Morocco during November for thoroughbreds can easily slip under the radar, but the prize money available is attractive.

The 2400m (12f) Grand Prix de Sa Majesté Le Roi Mohammed VI – Défi Du Galop for three-year-olds and up tops the purses at €133,000 (£116,000), while the Grand Prix des Eleveurs for threeyear-old fillies, run over 1750m (9f) carries €71,600 (£62,500). Entry fees are €650 (£567) and €350 (£305) respectively.

The 1900m (10f) Grand Prix des Proprietaires for three-yearold colts is worth €61,500 (£53,600), entry fee €300 (£262) and there is also a 1750m (9f) race for juveniles offering €28,500 (£25,000), the Prix Jean-Pierre Laforest.

The incentives to owners and trainers are also attractive, with flights paid for by SOREC for the owner plus one, trainer plus one and the jockey. Hotel accommodation is also provided by SOREC at the official hotel and transport to and from the racecourse and training centre. Grooms stay at the Bouskoura Training Centre in La Cité du Cheval, where the horses will stay. A transport subsidy is awarded to participating horses that come overland, Spain €2,000, France €2,500 and UK and Ireland €3,000 (£2,600).

For the temporary admission of horses, all horses must have a veterinary health certificate validated by the official veterinary service, and originals of test reports from the laboratory.

For most European countries, with which SOREC has sanitary agreements, there are two analysis that are requested, the test of Equine Infectious Anemia (Coggins test within 30 days of loading) and the test of Equine Viral Arteritis at the intervals indicated, within 21 days (Spain) or 28 days (France) of loading (Serum neutralisation test). For horses regularly vaccinated against this disease, a second test within a minimum 14 days is required. Horses must be properly vaccinated against Equine Influenza and Equine Viral Rhinopneumonitis.

With the addition of public holidays, racing takes place throughout the winter twice a week, with meetings at Happy Valley on most Wednesdays and at Sha Tin mostly on Sundays. All 31 Group Races are open to international horses. The highlight is the Hong Kong International Day 14th December at Sha Tin, with four Gp.1 races, the €4.4m (£3.8m) Hong Kong Cup 2000m (10f), the €3.9m (£3.5m) Hong Kong Mile 1600m (8f), €3m (£2.7m) Hong Kong Sprint 1200m (6f) and €2.9m (£2.5m) Hong Kong Vase 2400m (12f). Champions Day is held at Sha Tin 26th April 2026, with three Gp.1 races, the €3.3m (£2.9m) QEII Cup 2000m (10f), the €2.6m (£2.3m) Champions Mile 1600m (8f) and the €2.6m (£2.3m) Chairman’s Sprint Prize 1200m (6f).

Connections of selected overseas horses for Hong Kong’s seven feature Group 1 races, Longines Hong Kong Cup, Longines Hong Kong Mile, Longines Hong Kong Sprint, Longines Hong Kong Vase, FWD QEII Cup, FWD Champions Mile and Chairman’s Sprint Prize, will enjoy travel and accommodation packages provided by the Hong Kong Jockey Club.

Flights will be provided for the owner plus one, trainer plus one and the jockey, plus two persons per horse (groom, exercise rider, etc.) and five nights hotel accommodation for each of those listed. This also includes free transfers from the airport and transport between the official hotels and Sha Tin Racecourse for morning track work and race meetings, plus transport between the official hotels and the venues for official functions.

The Club also offers shipping incentives to selected overseas horses for the same seven feature Group 1 races, covering the costs of return transport by road from home stable to departure airport, and return air transport for each selected horse.

The Quarantine Stables are located at Sha Tin Racecourse, 45 minutes from Hong Kong International Airport. The Club strongly recommends shipping horses at least eight days before the date of the race to allow for the recovery from, and appropriate treatment of, any potential travel-related illness.

During the 90 days prior to export to Hong Kong, but not within 14 days, a horse must be administered either a primary course of approved vaccinations against Equine Influenza comprising of at least two doses with an interval of 4 to 6 weeks (or according to the terms of vaccine registration with the relevant government authority) or a booster vaccination given within 12 months of a primary course.

During the 14 days prior to export, specific disease testing is to be performed. No less than 10 days prior to a horse departing for Hong Kong, irrespective of the country in which the horse is located at the time, the trainer must submit the First Medication Declaration Form (MDF1) to the Club via the online Equine MediRecord system.

Between six days (maximum) and three days (minimum) a pre-travel veterinary inspection must be performed by a Club-approved veterinary surgeon. At the time of this inspection, the inspecting veterinary surgeon must obtain from the horse’s trainer a completed and signed copy of the Second Medications Declaration Form (MDF2), which records any additional medications administered to the horse since the submission of the First Medications

There are six Championship categories, with qualification achieved through either a minimum of three runs on the all-weather track and a high enough BHA rating, or by winning a Fast Track Qualifier.

There are also qualifiers in Ireland at Dundalk and in France at Cagnes-sur-Mer and Deauville.

Finals Day is the richest day of all-weather racing in Europe with prize money over £1m (€1.1m) and takes place at Newcastle on Good Friday, 3rd April 2026.

The Championship races comprise the Marathon over 3200m (2m) for four-year-olds up, The Fillies’ and Mares’ over 1400m (7f), the Sprint Championship over 1200m (6f) for four-year-olds up, the Three-year-old Championship over 1200m (6f), the Easter Classic over 2000m (10f) and the All-Weather Mile (1600m) for four-year-olds up.

Racing takes place fortnightly at Mons from October through to February, the highlight on 4th December being the 1500m (7.5f) Prix Open Mons worth €25,000 (£22,000), for three-year-olds and up who have not won or been placed second or third in a Group or Listed race. Prize money at each meeting ranges from €5,000 up to €8,000 (£4,000-£7,000).

The Bahrain Turf Series is an initiative designed to attract international runners to compete in Bahrain. The series targets horses rated between 85+ to compete against domestically trained horses. For 2025/26, the Bahrain Turf Series has been expanded to comprise ten handicap races, and two condition races, now worth a total of $1m (€852,000/£743,500), with a further $80,000 available in bonuses.

The programme starts on 19th December and runs until 5th March, with the final two handicaps, each worth $100,000 (€85,100/ £74,300), run as part of the King’s Cup Festival. Additionally, the expansion of the Bahrain Turf Series last year means that all the premier races in the second half of the season fall within the dates of the international programme. This enables horses to progress from Bahrain Turf Series races to Bahrain’s premier races, such as The Crown Prince’s Cup, The Shaikh Nasser Cup, the Al Methaq Mile and The King’s Cup, along with further valuable races.

Edward Veale, Director of Racing and International Relations, tells us how important and rewarding it is to bring people to Bahrain. “The development of internationallyrecognised racing has been very rewarding and we need to continue to build our international profile in order to keep improving the quality of our racing. Significant investment has gone into the Bahrain Turf Club and the racing programme, and international competition is integral to the improvement of the domestic core of horses. For example last year, of the 18 races we promoted as international, nine were won by visiting horses and nine domestically-trained horses. It is important to maintain this balance.”

To nominate for stabling, email Max Pimlott, max@irbracing.com by Thursday 6th November.

The Dubai Racing Carnival opens in November at Meydan Racecourse, the world’s largest racing facility hosting 17 meetings throughout the season, concluding in March with the 30th renewal of the Dubai World Cup on a card totalling $30.5m (€26.1m/£22.8m).

There are a number of valuable opportunities all season, beginning in November with the €125,600 (£106,912) Listed Dubai Creek Mile on dirt for three-year-olds up. January is busy, with 11 black type races from 1000m (5f) up to 2810m (14f) and ranging from €125,600 (£106,912) for Listed up to €213,489 (£181,719) for Group 2s and €924,282 (£786,662) for the Gp.1 Al Maktoum Challenge, 1900m (9f) on dirt. On turf, the Gp.1 Jebel Hatta, 1800m (9f) carries a purse of €464,658 (£395,469).

Beyond Meydan, the Abu Dhabi Equestrian Club hosts the Listed 1600m (8f) Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan National Day Cup in December, and the Listed 1400m (7f) HH The President Cup, both on turf with a prize of €95,443 (£81,242) each. Jebel Ali Racecourse hosts the Listed Jebel Ali Sprint, the third leg of the Emirates Sprint Series, 1000m (5f) on dirt for a prize of €125,600 (£106,912), and the Gp.3 Jebel Ali Mile on dirt, €175,840 (£149,677). Fifteen black type races from Listed up to Group 2 are run at Meydan during February and March, again from 1000m (5f) to 2810m (14f) and with similar valuable prizes, all of which lead through to the end-of-season highlight of Dubai World Cup night.

The 10th Running of the Gr.1 The Pegasus World Cup Invitational at Gulfstream Park Saturday 24th January will be worth $3m (€2.56m/£2.2m). For four-year-olds and upward, the 1800m (9f) dirt race is by invitation only, with no fees to enter or start, and is the finale on a star-studded 12-race card.

Also on the card is the Gr.1 The Pegasus World Cup Turf Invitational, over the same distance and under the same conditions, worth $1m (€852,000/£743,500), and the 1600m (8f) Gr.2 Pegasus World Cup Filly and Mare Turf Invitational, with a purse of $500,000 (€426,000/£372,000).

Entries close at noon on Sunday 18th January. The Pegasus World Cup Selection Committee will publish a list of invitees 31st December. There are automatic qualifiers into the 2026 Pegasus, the winner of the Sussex Stakes at Goodwood receives an automatic invitation to the Pegasus World Cup Turf and the winner of the Qatar Nassau Stakes (Gp.1) receives an automatic invitation to the Pegasus World Cup Filly and Mare Turf, and at Woodbine the invitation will be extended to the winner of the Dance Smartly, plus all receive a $25,000 travel allowance and VIP hospitality for the winning connections.

All of the connections of runners are assured they will be looked after better than anywhere else in the USA, with 5-star hotels available, ground transport and VIP accommodations on raceday.

Supporting the invitationals are the 2400m (12f) Gr.3 William L. McKnight Turf race for four-year-olds and up, and the 1400m (7f) Gr.2 The Inside Information Dirt race for fillies and mares four-year-olds and up, both worth $200,000 (€170,000/£149,000).

Free nomination by 11th January, $2,000 (€1,700/£1,500) to enter. There are also three $150,000 (€128,000/£111,500) races, with free nomination by 11th January, $1,500 to enter, namely the 1000m (5f) The Gulfstream Park Turf Sprint for four-year-olds and up on Turf, the Gr.3 1600m (8f) The Fred W. Hooper on Dirt, and the 2400m (12f) Gr.3 The Christophe Clement for fillies and mares four-year-olds and up. Run on Tapeta over 1600m (8f) for $100,000 (€85,200/£74,300) are The South Beach for fillies and mares fouryear-olds and up, and The Carousel Club for four-year-olds and up, both handicaps.

In Britain, £3.2m (€3.7m) will be invested in prize money for developmental races in 2026, comprising novice and maiden races on the Flat and over Jumps, 20% of the race programme. Over Jumps, a total of approximately 50 novice and beginners’ chases will be programmed in 2026, with minimum values at £20,000 (€23,000) for Class 2 and £15,000 (€17,000) for Class 3. The same values will apply to novice and maiden hurdles. Class 4 races will be permitted with a minimum value of £10,000 (€11,500).

A new bonus scheme will be introduced for point-to-point horses, with the aim of strengthening the programme as a development ground for future stars progressing to race Under Rules. The Maiden Series, which will be supported by £250,000 (€286,000) of funding, will take place at selected Point-toPoint Authority (PPA) tracks during the 2025/26 season. It will comprise 15 maiden races for four and five-year-old horses, with the winners of those races qualifying for a bonus when they win their first developmental novice or maiden race over hurdles or fences Under Rules.

A significant number of Class 3 Novices’ Limited Handicap Chases have been removed from the programme and replaced with ‘Chasing Excellence’ Beginner/Novices’ Chases, each run for an increased minimum value of £12,000 at Class 3 rising to £15,000 in 2026. The new Chasing Excellence initiative will see more Class 2 and 3 Beginners’ Chases weight-for-age contests restricted to horses that have not yet won a race over fences, and Novices’ Chases replacing a significant number of Class 3 Novices’ Limited Handicap Chases, from October 2025 and into 2026.

New requirements for Grade 1 Novices’ and Juvenile Hurdle races mean that horses will only be permitted to run in Grade 1 Novices’ and Juvenile Hurdle races if they have been allotted a rating or an assessment of 110 or more by the BHA Handicapper, taking account of races run up to and including the day prior to confirmation. The change brings the novice and juvenile hurdle division into line with Open Grade 1 Chases and Hurdles and Grade 1 Novices’ Chases, all of which require a minimum rating to participate.

Adjustments have also been made to the Junior National Hunt Hurdles programme. The start of the Junior NH Hurdle season has moved to the beginning of November (from October) to allow trainers more time to develop these horses at home. The number of races for the season will remain the same.

A penalty for a win in a Junior NH Hurdle will not be carried into other race types in future, except in other Junior NH Hurdles and in Class 1 races. This includes in Juvenile and Novices’ Hurdle races during the same season, but winners will still lose their maiden status over Jumps.

Non-winners of Junior NH Hurdles will be permitted to drop back to ‘Junior National Hunt Flat races’, three-year-olds only before the end of the year or four-year-olds only after 31st December, run until the end of the season.

In addition, several changes have been made to the Go North Series, which culminates in Finals weekend at Kelso, Musselburgh and Carlisle racecourses in late March. The Go North Series provides meaningful end-of-season targets for connections and this season’s series Finals will be run for increased minimum values, with a prize fund of at least £40,000 (€45,700) per race.

A new ‘Forgive ’n ’Forget’ Novices’ Handicap Chase Series will have Class 4 and 5 Novices’ Handicap Chases qualifiers and the Final will be run over 2m 5f 133y (4200m) at Kelso. A new ‘Night Nurse’ Handicap Hurdle Series will have qualifiers made up of Class 2-4 Juvenile and Novices’/Maiden WFA Hurdle races, and the Final will be for four-year-olds and up and run over 2m 3f 171y (3800m) at Musselburgh.

The Jumps Weekend concludes the season at Auteuil on November 15th and 16th, with 15 races over two days - eight over hurdles and seven steeplechases including four Grade 1 races.

The programme includes the Gr.1 Prix Renaud du Vivier, a 3900m (2m3f) hurdle for four-year-olds with a purse of €280,000 (£245,000). The €363,000 (£317,000) Prix Serge Landon Hurdle over 4800m (3m) for five-year-olds up; the €355,000 (£310,500) Prix Maurice Gillois Steeplechase over 4400m (3m2f) for four-year-olds; the €278,000 (£243,000) Prix Cambacérès Hurdle over 3600m (2m2f) for three-yearolds and the €580,000 (£507,000) Prix La Haye Jousselin over 5500m (3m4f) for five-year-olds up.

To learn more about the opportunities to train & race in Belgium this year contact Bernard Sto el +32 475 933 457 or by email contact@bgalopf.be RACE IN BELGIUM! TRAIN

Belgium is at the crossroads of horse racing in Europe: UK, Netherlands, Germany, France are only a stone’s throw from our training centers!

Coral Gold Cup Handicap Steeple Chase (Class 1) (Premier Handicap) 3m 1f 214y (4yo+)

The “Bet-In-Race” With Coral Intermediate Handicap Hurdle Race (Class 1) (Registered as The Gerry Feilden) (Premier Handicap) 2m 69y (4yo+)

The Coral Get Closer To The Action Handicap Steeple Chase (Class 2) (For The Jim Joel Memorial Trophy) 2m 92y (4yo+) (0-145)

The Sir Peter O’Sullevan Memorial Handicap Steeple Chase (Class 2) 2m 6f 93y (4yo+) (0-145) £250,000

The Coral John Francome Novices’ Steeple Chase (Class 1) (Grade 2) (Formerly known as the Berkshire) 2m 3f 187y (4yo+)

Coral Long Distance Hurdle Race (Class 1) (Grade 2) 3m 52y (4yo+)

Coral Racing Club Handicap Steeple Chase (Class 2) 2m 3f 187y (4yo+) (0-150)

“Bet-In-Race” With Coral Fillies’ Juvenile Hurdle Race (Class 1) (Listed Race) 2m 69y (3yo)

£55,000 £5k increase £50,000 £5k increase £50,000 GOLD CUP

£75,000 £15k increase

The Coral Challow Novices’ Hurdle Race (Class 1) (Grade 1) 2m 4f 118y (4yo+)

The Coral Mandarin Handicap Steeple Chase (Class 2) 3m 1f 214y (4yo+) (0-145)

£100,000 ENTRIES CLOSE TUES 28 OCT £250K International entries close day before

Injuries to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and suspensory ligament (SL) are sadly a common occurrence in racehorses, with jump racing in particular placing these structures under intense mechanical stress. In a large UK study of 1223 UK National Hunt racehorses over two seasons, the rate of tendon and suspensory ligament injuries (TLIs) in training was 1.9 per 100 horse-months at risk. Of these, around 89% were SDFT injuries, with the remainder being SL injuries. The study also found that risk of TLIs varied by trainer and increased with the horse’s age. (Ely et al., 2009). Another noteworthy study performed regular ultrasonography on 263 National Hunt horses over two seasons, concluding that 24% of them showed structural changes of the SDFT, even before an injury was clinically evident. (Avella et al., 2009).

Focussing primarily on the SL, a study found SL injuries in racehorses to have an incidence of 2.7 per 1000 starts, with a prevalence range of 3.6% to 10% depending on type of race and population studied. (Davies et al., 2021). In flat thoroughbreds, rates of SDFT tendinitis in training/populations range between roughly 3.4% and 11.1%, and SDFT injuries are responsible for a significant portion of horses retiring from their racing careers. (Kasashima et al., 1999).

These two structures lie at the heart of the suspensory and passive stay apparatus, functioning like elastic springs which absorb energy and aim to prevent excessive extension of the fetlock. When the strain placed upon them is too great, too frequent, or inadequately managed, micro-damage builds up over time, leaving the limb vulnerable to more serious breakdown. This makes SDFT and SL injuries among the most significant welfare, performance, and economic concerns in the horse racing industry.

It is for this reason veterinary scientists and researchers alike will not be deterred from trying to find answers to the critical questions of; why the prevalence of this type of injuries is so high, what we can do to help prevent them occurring and what is the best rehabilitation strategy when the worst happens.

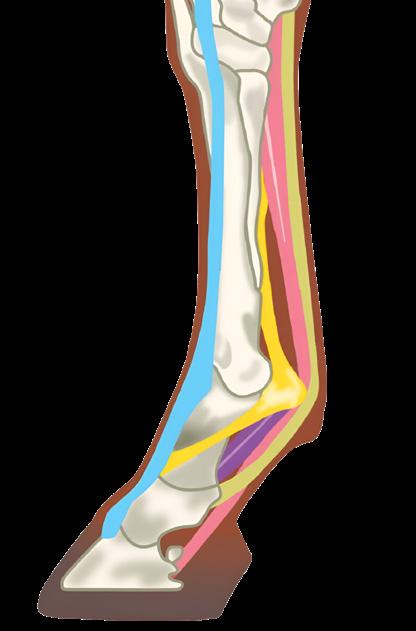

The SDFT is the continuation of the superficial digital flexor muscle, the top of the tendon attaches to the humerus, radius and ulna. The tendon properly begins on the back of the lower radius and extends down the surface of the limb, lying superficially to the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) and making it readily palpable along the length of the metacarpus or commonly known, cannon bone. Enclosed within the flexor tendon sheath, the SDFT glides over the DDFT and suspensory ligament, maintaining close anatomical relationships that are critical to their function. Just above the fetlock, the superficial flexor tendon forms a small “tunnel” of tissue that the deep flexor tendon passes through before continuing down the leg. At the level of the pastern, the SDFT divides into two branches that insert on both the long pastern (P1) and the short pastern (P2). Functionally, the SDFT acts not only as a flexor of the pedal bone/foot (P3) but also as a vital part of the passive stay apparatus, resisting over-extension of the fetlock and pastern joints. Its elastic properties allow it to store and release energy during locomotion, making it a key contributor to the horse’s stride efficiency.

The SL is a highly modified ligament that originates from the upper, back area of the cannon bone, with fibres also arising from the bottom row of carpal bones. From its broad origin, the SL runs downwards along the cannon, positioned deep (or below) to

Long Pastern Bone (P1)

Extensor branch of suspensory ligament

Short Pastern Bone (P2)

Pedal Bone (P3)

Superficial digital flexor tendon

Proximal suspensory ligament

Deep digital flexor tendon

Superficial distal sesamoidean ligament Suspensory ligament

Deep digital flexor tendon

both the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons. In the midregion of the cannon its fibres become more discrete and near the bottom third of the cannon the ligament divides into medial and lateral branches. Each branch curves around the outside of the upper sesamoid bones at the back of the fetlock, before continuing forward as the extensor branches, which attach into the main extensor tendon running down the front of the leg.

Functionally, the SL is the cornerstone of the suspensory apparatus, supporting the fetlock and preventing its overextension under the heavy loading of movement. Together with the sesamoid bones and lower sesamoidean ligaments, it acts as a dynamic support structure, storing elastic energy and releasing it to aid forward propulsion. Its critical role in both stability and energy efficiency explains why the SL is so frequently impacted by injury and disease.

In conclusion, the SDFT and SL are very interconnected, both anatomically and functionally. The SDFT primarily provides flexion of the foot and helps support the fetlock and pastern, while the SL suspends the fetlock and forms the foundation of the suspensory apparatus. Both are integral to the horse’s remarkable efficiency of movement and endure significant forces during training and on the racecourse.

A study at the Royal Veterinary College (Hertfordshire) by Hanousek and colleagues (2024) investigated how injury to the palmar supporting structures of the fetlock, the SDFT in the forelimb and the SL in the hindlimb, affects limb biomechanics. Using a retrospective cohort of clinical cases, the authors measured limb stiffness and fetlock conformation in injured and uninjured horses with a validated, non-invasive technique combining floor scales and electrogoniometry (electronic sensors to measure joint angles during movement).

In uninjured horses, forelimb stiffness was found to be significantly greater than hindlimb stiffness, reflecting their different roles in locomotion, while fetlock conformation did not differ between limbs. Age did not influence stiffness in this mature population (aged between 3yo and 35yo). This corresponds with the knowledge that tendon maturity is thought to be reached between 2 and 3 years old.

In horses with forelimb SDFT injuries, there was no long-term difference in stiffness or conformation between the injured and opposite uninjured limbs, even with follow-up examinations extending beyond three years. This suggests that SDFT injuries, despite fibrotic healing, may recover mechanical function sufficiently to restore overall limb stiffness. By contrast, hindlimb SL injuries were associated with both increased limb stiffness and greater fetlock extension, consistent with elongation of the ligament following injury. These changes persisted regardless of injury duration, indicating a lasting alteration in the biomechanics of the hindlimb fetlock after SL damage.

The findings highlight important distinctions between the biomechanical consequences of SDFT and SL injuries. While SDFT lesions appear to permit functional compensation within the limb, SL injuries lead to measurable and persistent changes in stiffness and fetlock angle. Clinically, these differences may explain the poor prognosis often associated with chronic suspensory disease and underline the importance of fetlock support during rehabilitation.

A review paper published last year, by Guest and colleagues provides a comprehensive analysis of the SL, emphasising its central role in athletic performance and its high susceptibility to injury. The review highlights that, despite the clinical significance of SL disease across a range of equestrian disciplines, research into its anatomy, biomechanics, and pathology falls short of that of the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons. The SL is described as a unique structure; an evolutionary adaptation from a muscle to a predominantly fibrous ligament that functions both as a key component of the suspensory apparatus and as an elastic energy store during movement.