5 minute read

Install Trash And Recycling Receptacles In Public Space

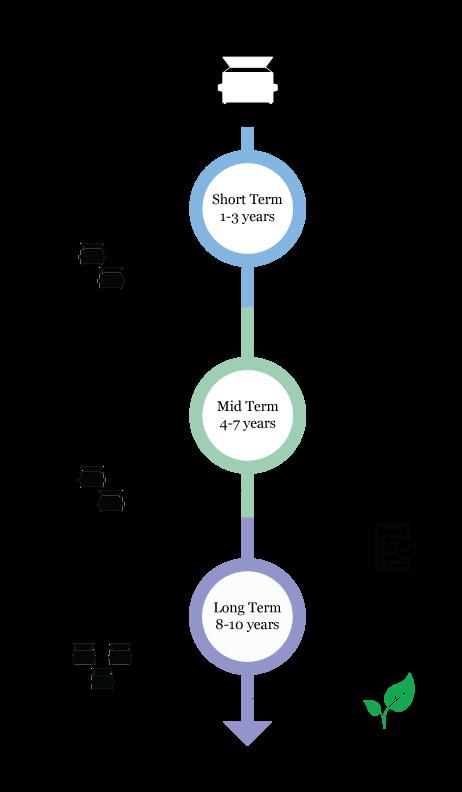

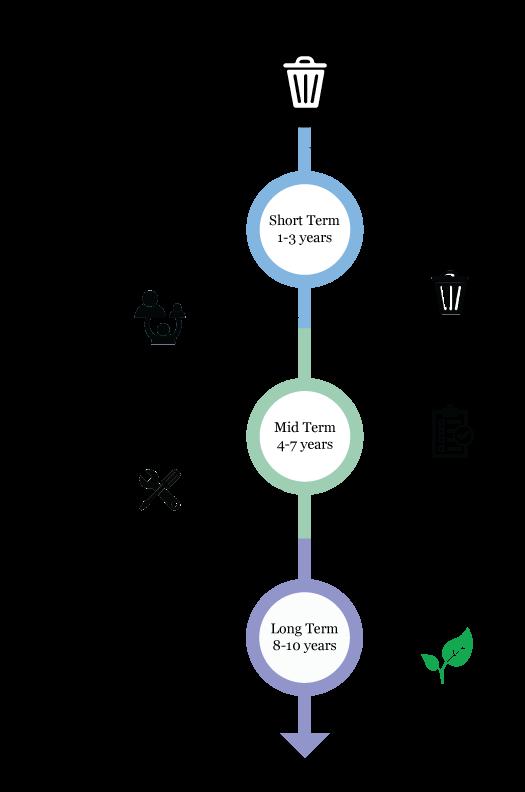

146 Dumpsters Timeline once installed, their effectiveness depends on the City of São Paulo. If dumpsters are emptied irregularly or are at capacity too frequently for any reason, trash will overflow into the streets or residents will stop making the walk out to the dumpsters. If residents cannot rely on the dumpster, dumping, burning, and littering will become the most feasible solid waste disposal option again.

COSTS:

Intervention Per Unit Cost Total Cost Dumpster PHASE 1 $800 per dumpster $800 Dumpster PHASE 2 $800 per dumpster $800

Dumpster PHASE 3 TBA after reassessment TBA

INSTALL TRASH AND RECYCLING RECEPTACLES IN PUBLIC SPACE

Public trash and recycling receptacles should be installed throughout the Occupation. This recommendation is a response to ideas voiced at the community meeting as well as the scattered litter, piles of burning trash, and precarious landfills, dumping, and contaminated water observed. Decentralizing solid waste collection through the installation of refuse containers, will make the current system more effective, efficient, and could potentially improve economic opportunities for residents.

The current recycling system that involves the few women in the Occupation who collect the recycling and sell them outside the Occupation. As well as the trash collection by families, usually children, into municipal dumpsters – are the main waste management systems in place. Prior research has shown that when attempting to improve waste management systems, incorporating informal

147 Recycling Receptacles in Brazil

systems are more successful than creating new ones (Wilson et al., 2006). Therefore, this proposed intervention honors the informal recycling economy and waste collection system identified by the Taubman College Team on site and strives to build upon them.

There are a number of actors responsible for implementing this intervention successfully. Since Instituto Anchieta Grajaú is the landowner and the receptacles will remain with the physical property over time, the Institute could partner with donors for purchasing and installing the receptacles. To maintain and create economic opportunities, IAG should hire Occupation residents to maintain the receptacles. This hiring process could be facilitated by the Association because they are trusted in the Occupation. The current women who work as the Occupation’s recyclers will be able to maintain their current door-todoor collection and will now have additional opportunities to pick up recyclables in public space and be paid to do so. These roles need to be clearly defined and this network of actors must be held accountable through signed contracts that detail each role, collection schedules, and worker compensation.

The trash and recycling receptacles should be placed next to each other and clearly labeled in a way that distinguishes them. The receptacles should be located in public spaces such as outside of the Association headquarters, bars, bakeries, restaurants, and even convenience shops. These spaces are frequented by residents. Additionally, the proposed cultural center (Cultural Anchieta) and the proposed public space around the creek and springs (Creek Revival) should have with these receptacles as well. It is important that the public has a designated place to put food wrappers, empty beverage containers, and similar trash and recycling items that may be generated in these public spaces. To reinforce proper receptacle use the colors of the receptacles should be distinct and consist with Brazil’s formal waste management system. Therefore, receptacles

CASE STUDY: Managua, Nicaragua

The Manos Unidas Waste Management Program was established in 2009 through support from a local NGO, Habitar, and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Nicaragua. Manos Unidas is a cooperative of 18 men who use carts to collect household waste from several informal settlements. The first year of the program involved career development for the workers and environmental campaigns for the public. After the first year, the City of Managua and Manos Unidas signed a formal agreement that detailed specific routes within the district for which Manos Unidas would be responsible. The program was successful in helping to decentralize the waste management system in Managua until the program’s end. When the project ended in 2012, Habitar in UNPD continued to support Manos Unidas, but the city has not stayed committed to the original signed agreement (Zapata, 2013).

148 Difficult Street Conditions for Waste Compaction Trucks.

for plastics should be red, receptacles for glass should be green, and trash receptacles should be black or gray (Utsumi, 2015 ).

Although the primary purpose of this intervention is to provide alternatives to littering in the public sphere, it could also be a way to mitigate the insufficient efforts of distracted children or those who cannot walk to the communal dumpster. However, for this to be a feasible recommendation, receptacle capacity and management structures will need further consideration.

Barriers to implementing this recommendation successfully include costs, establishing management, and educating the public to use receptacles properly. Trash and recycling receptacles are a low to midrange cost compared to other proposals. However, the Institute has to be willing to front the costs for actual containers and, secondly, has to be willing to pay residents to manage them. This will require IAG to play a role in the informal waste management economy that is present in developing countries around the globe. If IAG is unwilling, the Association and Occupation residents may want to consider creating their own funding structures. The waste management systems that have funding to pay informal workers are far more successful than those that do not. This is evident in the Managua, Nicaragua case. Lastly, addressing issues around educating the public about the importance

149 Timeline

of solid waste management, as well as how to handle solid waste properly, will require an educational component. Proposed educational activities are discussed later in this chapter.

COSTS:

Intervention Per Unit Cost Total Cost Receptacle $300 USD per receptacle $2,100 USD

Bags/ Receptacle Liners $25 USD per 1,000 bags $50 + USD 150 Produce from the Green Exchange Program

CASE STUDY: The Green Exchange Program, Curitiba, Brazil

Established in 1991, The Green Exchange Program is a city-wide initiative that allows residents to trade recyclable materials for fresh produce. The program was made possible through a partnership between two city agencies (Secretaria Municipal do Meio Ambiente [SMMA] and Secretaria Municipal do Abastecimento [SMAB]). Funds from SMMA buy surplus crops from regional farms that belong to an association of small-medium farmers in the metropolitan area. The city trades the crops for resident-collected recyclable material throughout the year. Therefore, this initiative promotes recycling and discourages pollution while supporting local agriculture and providing healthy food to low-income residents, especially (Cather, 2016).