PORTFOLIO OF WORK

AMY VAN DE RIET Student Work, Professional Work,and Research

•

•

• ARCH 108: Architectural Foundations I

• ARCH 109: Architectural Foundations II

• ARCH 209: Architectural Design II

• ARCH 508: Materials and Techtonics Design Studio

• ARCH 600: Special Topics in Architecture: Historic Preservation Workshop

• ARCH 600: Special Topics in Architecture: Applied Historic Preservation Technologies

• ARCH 649: Historic Preservation Technology

• Courtyard Restoration of the Otto Kahn House, Convent of the Sacred Heart School

• Brooklyn Bridge Park Pier 2

• Existing Conditions Assessment for the Historic Campus Core of Georgian Court University

•

• Grotesque Replication Project

• Documenting the Work of Kansas Architect Charles McAfee

• 3D Drone Scanning Archaeological Ruins

1. DRAWING (FREEHAND)…Learning to see with our mind and eyes

An introductory design studio directed towards the development of spatial thinking and the skills necessary for the analysis and design of architectural space and form. This course is based on a series of exercises that include direct observation: drawing, analysis and representation of the surrounding world, and full-scale studies in the making of objects and the representation of object and space. Students are introduced to different descriptive and analytical media and techniques of representation to aid in the development of critical thought. These include but are not limited to freehand drawing, orthographic projection, Paraline drawing, basic computer skills, and basic materials investigation.

Prerequisite: Approval from the Dean of the School of Architecture, Design & Planning.

Admission to the Master of Architecture (M.Arch.) program leads to a degree that is fully accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) and meets the certification requirements of the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB). The NAAB establishes Student Performance Criteria to help accredited degree programs prepare students for the profession while encouraging education practices suited to the individual degree program.

Architecture Foundations covers the NAAB Student Performance Criteria (SPC): A2 (Design Thinking).

1. DRAWING (FREEHAND)…Learning to see with our mind and eyes;

1a CONTOUR - drawing objects & continuous line drawings of buildings

1b PERSPECTIVE - constructing boxes in line & tone

1c SPACE - perspectives of buildings

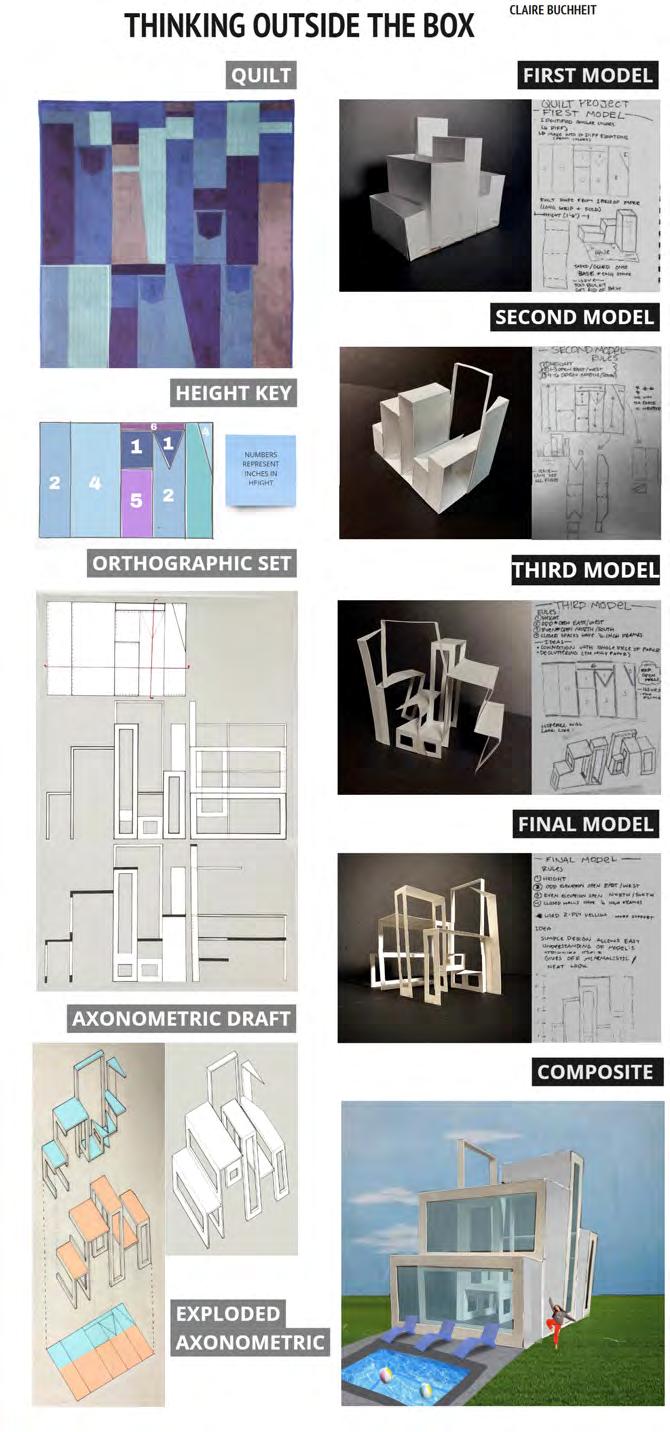

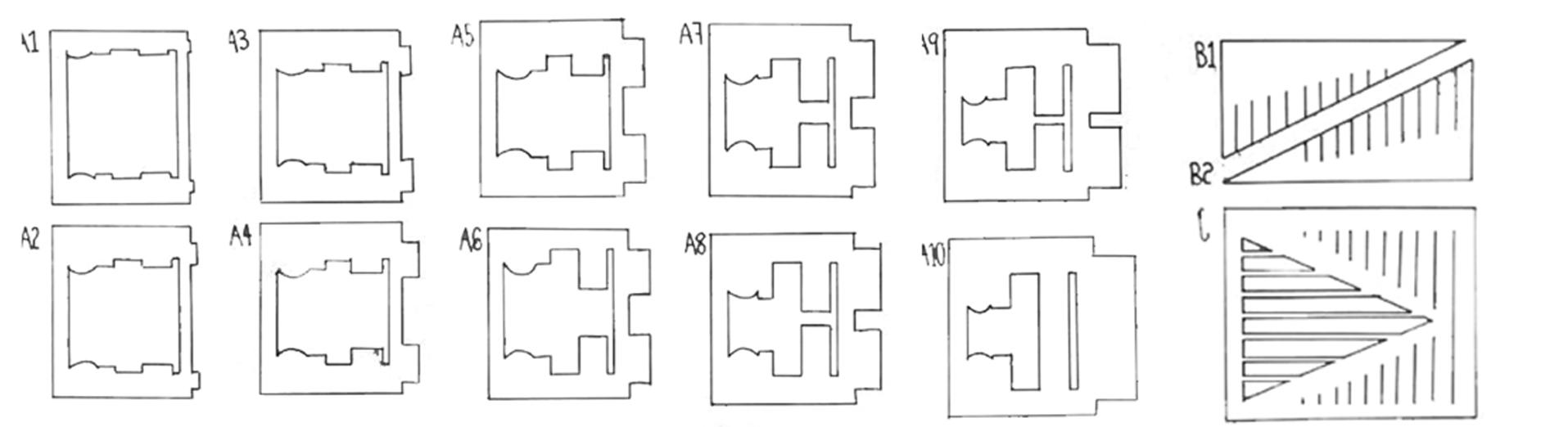

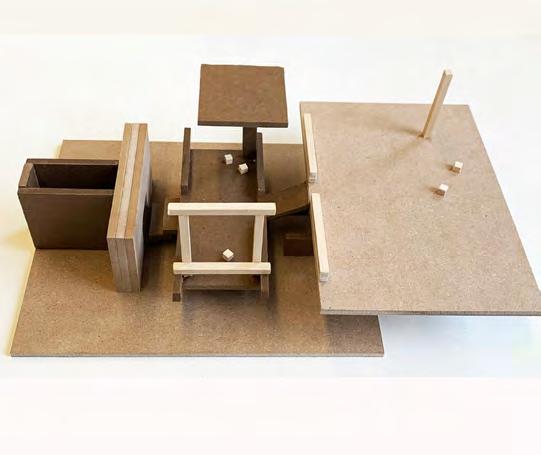

2. LINE (LAYER MODEL)… Exploring plan-generated form-making

2a SLICE - Analyzing an image

2b EXTRUSION - Making models

2c PARALINES - Exploring exploded axonometrics

3. OBJECT (WALL SYSTEM)

3a TRANSFORMATION - Exploring sculptural form-making and transformation diagramming

3b WALL SYSTEM - horizontal pattern-making and discovering systems

4. SPACE (LIGHTBOX)

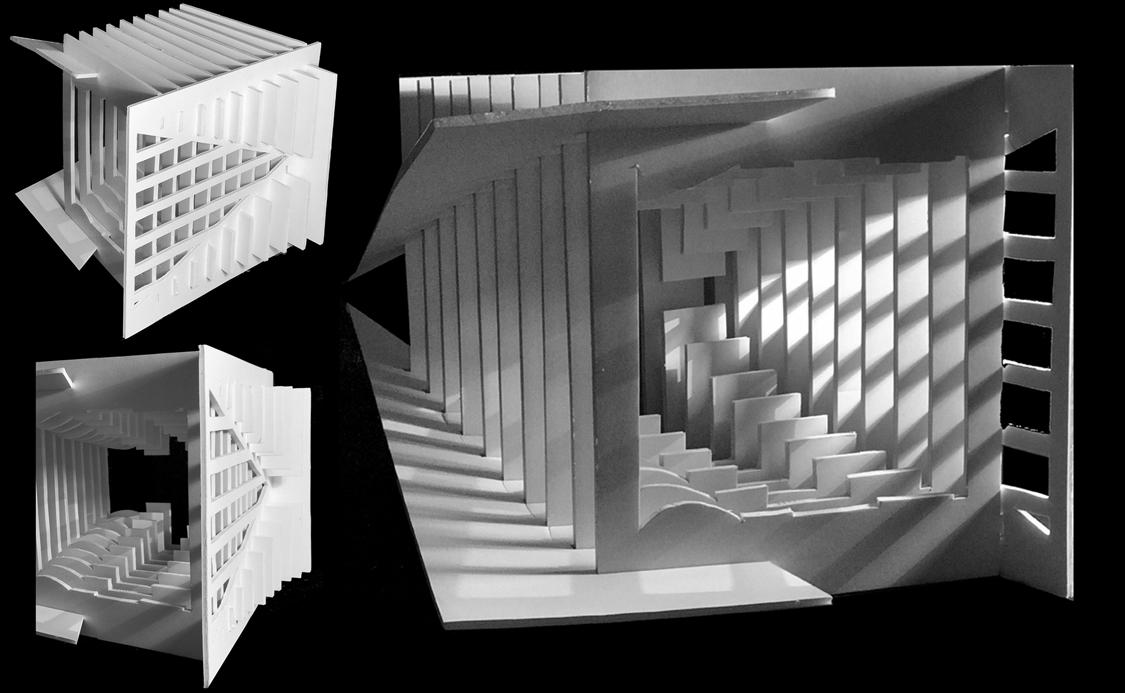

4a LIGHTBOX - Exploring the relationship between section and space,

4b ASSEMBLY - assembly drawings, photos, and presentation

Karis Buendia

Brittany Perez

Haleigh Strebe

Jasmine Nguyen

Claire Buchheit

Matthew Garrett

Danielle Voelkerding

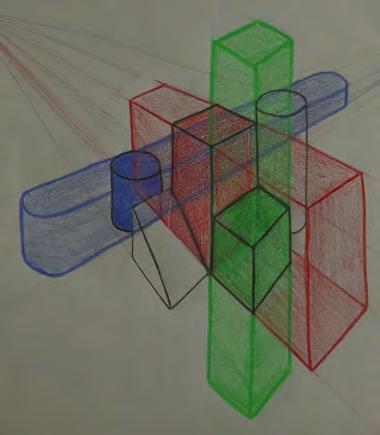

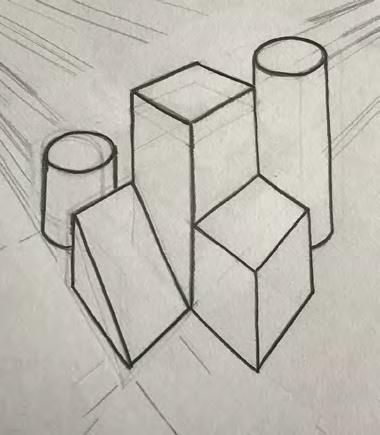

1a CONTOUR - drawing objects & continuous line drawings of buildings

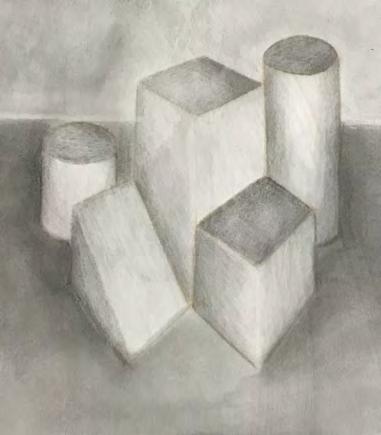

1b PERSPECTIVE - constructing boxes in line & tone

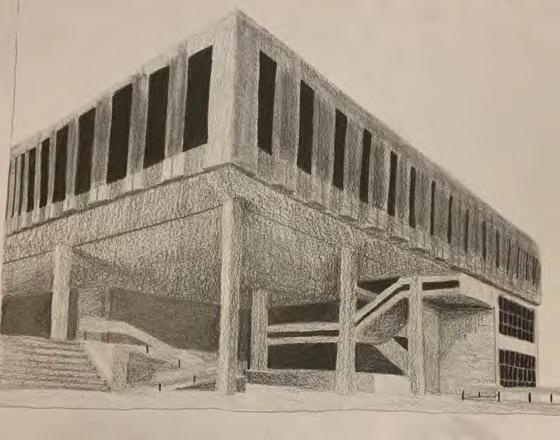

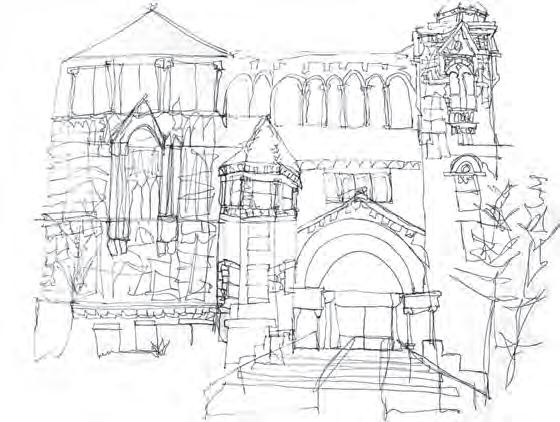

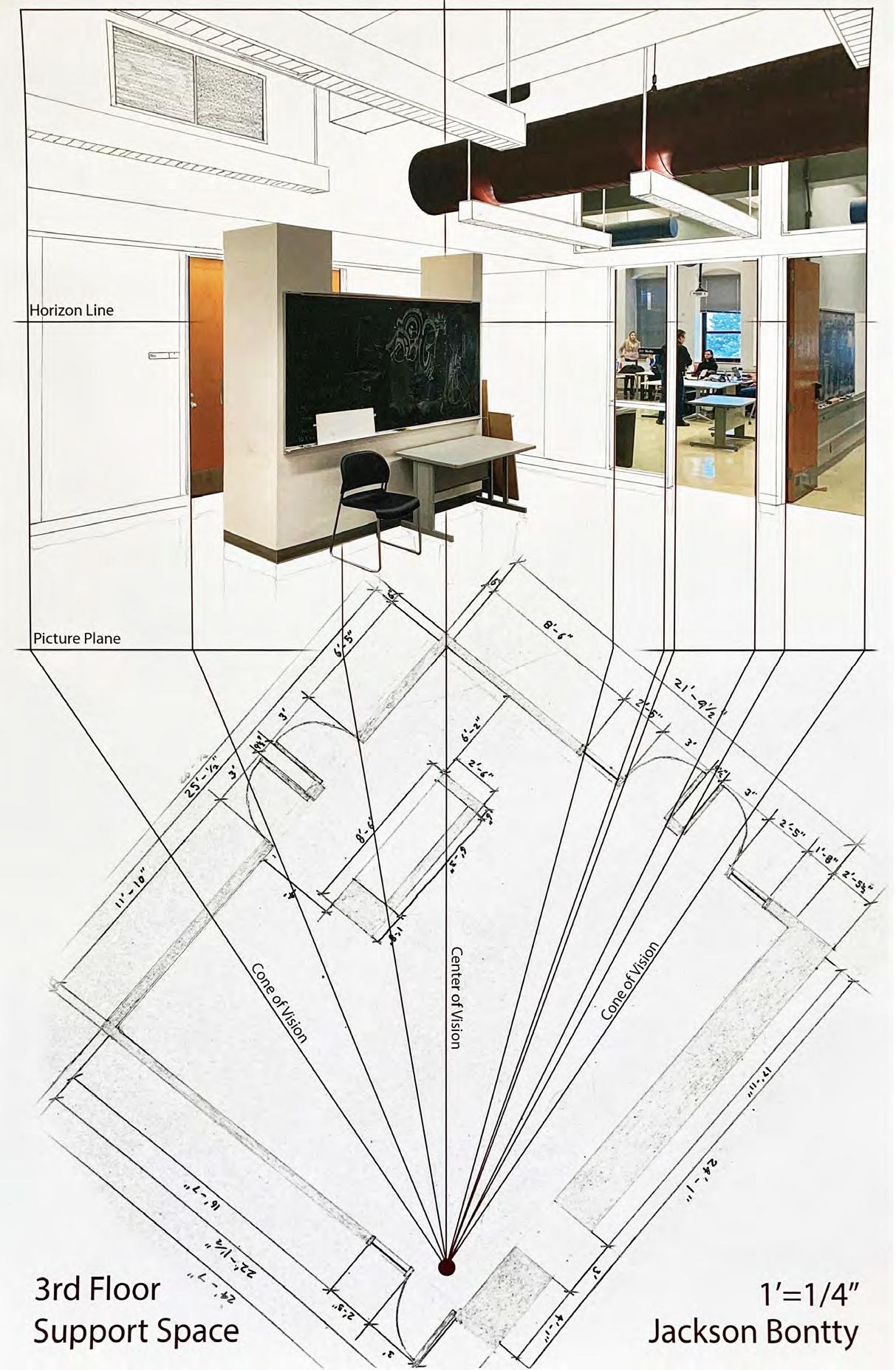

1c SPACE - perspectives of buildings

4a LIGHTBOX - Exploring the relationship between section and space 4b ASSEMBLY - assembly drawings, photos, and presentation

ARCH 109 is a continuation of ARCH 108 with a major emphasis on the design relationships among people, architectural space, and the environment. The course is based on a series of exercises leading to the understanding of architectural enclosure as mediating between people and the outside world. Issues of scale, light, proportion, rhythm, sequence, threshold, and enclosure are introduced in relation to the human body, as well as in relation to architectural form, environment. Students will engage in freehand drawing, perspective projection, model building, and basic computer graphics.

Prerequisite: ARCH 108

Admission to the Master of Architecture (M.Arch.) program leads to a degree that is fully accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) and meets the certification requirements of the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB). As an accredited degree, this course addresses the following NAAB student performance criteria (SPC)…

A.1 Professional Communication Skills: Professional Communication Skills: Ability to write and speak effectively and use representational media appropriate for both within the profession and with the general public.

A.2 Design Thinking Skills: Ability to raise clear and precise questions, use abstract ideas to interpret information, consider diverse points of view, reach well-reasoned conclusions, and test alternative outcomes against relevant criteria and standards.

A.4: Architectural Design Skills: Architectural Design Skills: Ability to effectively use basic formal, organizational and environmental principles and the capacity of each to inform two- and threedimensional design.

A.5 Ordering Systems: Ability to apply the fundamentals of both natural and formal ordering systems and the capacity of each to inform two- and three-dimensional design.

A.6 Use of Precedents: Ability to examine and comprehend the fundamental principles present in relevant precedents and to make informed choices about incorporation of such principles into architecture and urban design projects.

PROJECTS

1. PLACE… analyzing how we see a place. 1a PRESENCE 1b VIEWFINDER 2. SCALE/MOTION … documenting and analyzing human motion. 2a MOTION 3. SEQUENCE … designing a new condition. 3a SPATIAL JOURNEY 3b ORTHOGRAPHICS 3c STORYBOARD/PERSPECTIVE 4. ENCLOSURE… working with reality. 4a SITE 4b POD

SELECTED

1. PLACE… analyzing how we see a place. 1a PRESENCE

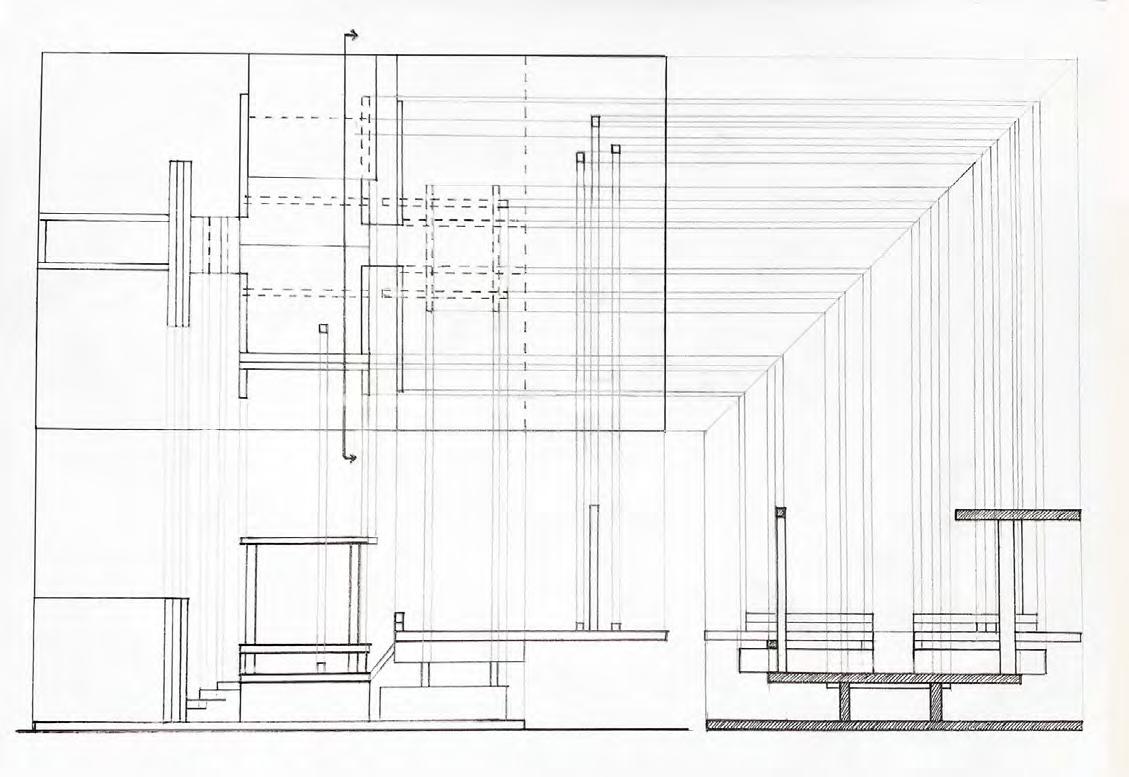

The Viewfinder is created by selecting a building from a list of a wide-range of architects provided by the instructor. Students must find a scaled floor plan and a photo of an interior space of the building. They then find the location of the photographer on the floor plan and create some of the architectural features of the space. The photograph is scaled to accurately depict the perspective of the photographer, and strings are used as guides to show the view from the photographer’s camera.

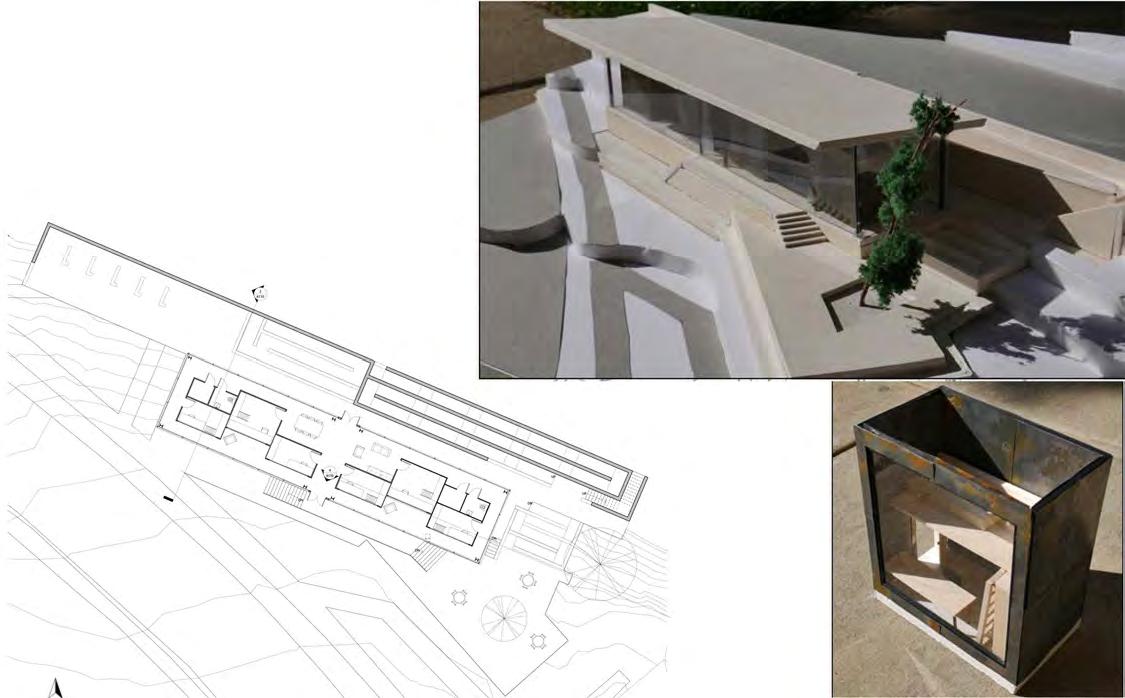

This project utilizes a “kit of parts” of specific architectural elements. Each student creates their own journey through the site. The resulting model is then documented in drawings.

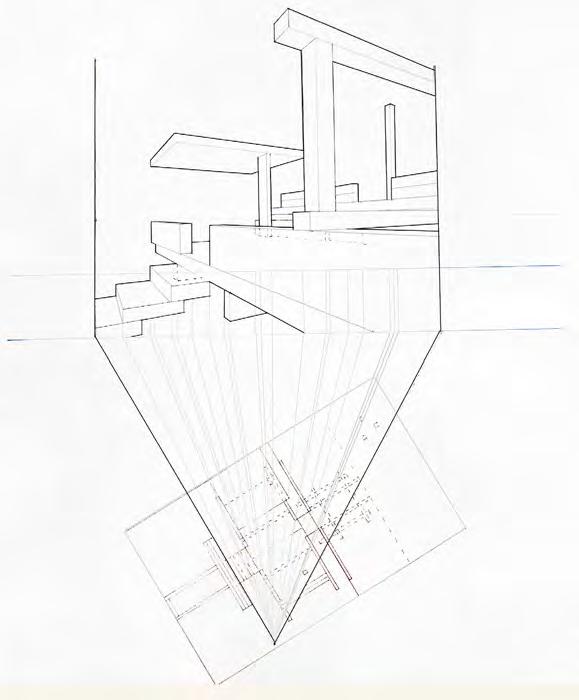

This project begins with a study of the site - located behind Watson Library on KU campus. The students then create spaces for individual study and group gathering. Shown here is the plan, model of building, and a detailed model of individual study space.

The second year design studios are responsible for introducing students to the basic form determinants of architecture – from limited scope exercises to complete building designs. Using diagrams and sketches, plans, sections, elevations and models, students explore the spatial ordering of human activity, site and landscape analysis, light and air modulation, simple environmental controls and energy conservation, basic framing systems, volumetric organization and the materials of buildings skins and envelopes.

A continuation of ARCH 208 with an emphasis upon the synthesis of basic form determinants in the context of a medium-sized, multistory public building in the urban environment. Students will demonstrate competence in basic architectural design, and preparedness for the third-year focus on materials and methods of building construction. Prerequisite: ARCH 208. LAB.

NAAB Criteria (National Architectural Accreditation Board)

Admission to the Master of Architecture (M.Arch.) program leads to a degree that is fully accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) and meets the certification requirements of the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB).” The NAAB establishes Student Performance Criteria (SPC) to help accredited degree programs prepare students for the profession while encouraging education practices suited to the individual degree program. Student Performance Criteria (SPC) Addressed in Arch 209:

Introduction:

A3: Investigative Skills

B2: Site Design

B3: Codes and Regulations

B5: Structural Systems

B6: Environmental Systems

B10: Financial Considerations

Understanding:

A2: Design Thinking Skills

A4: Architectural Design Skills

B7: Building Envelope Systems

Ability / Demonstration:

A1: Professional Communication Skills

A5: Ordering Systems

A6: Use of Precedents

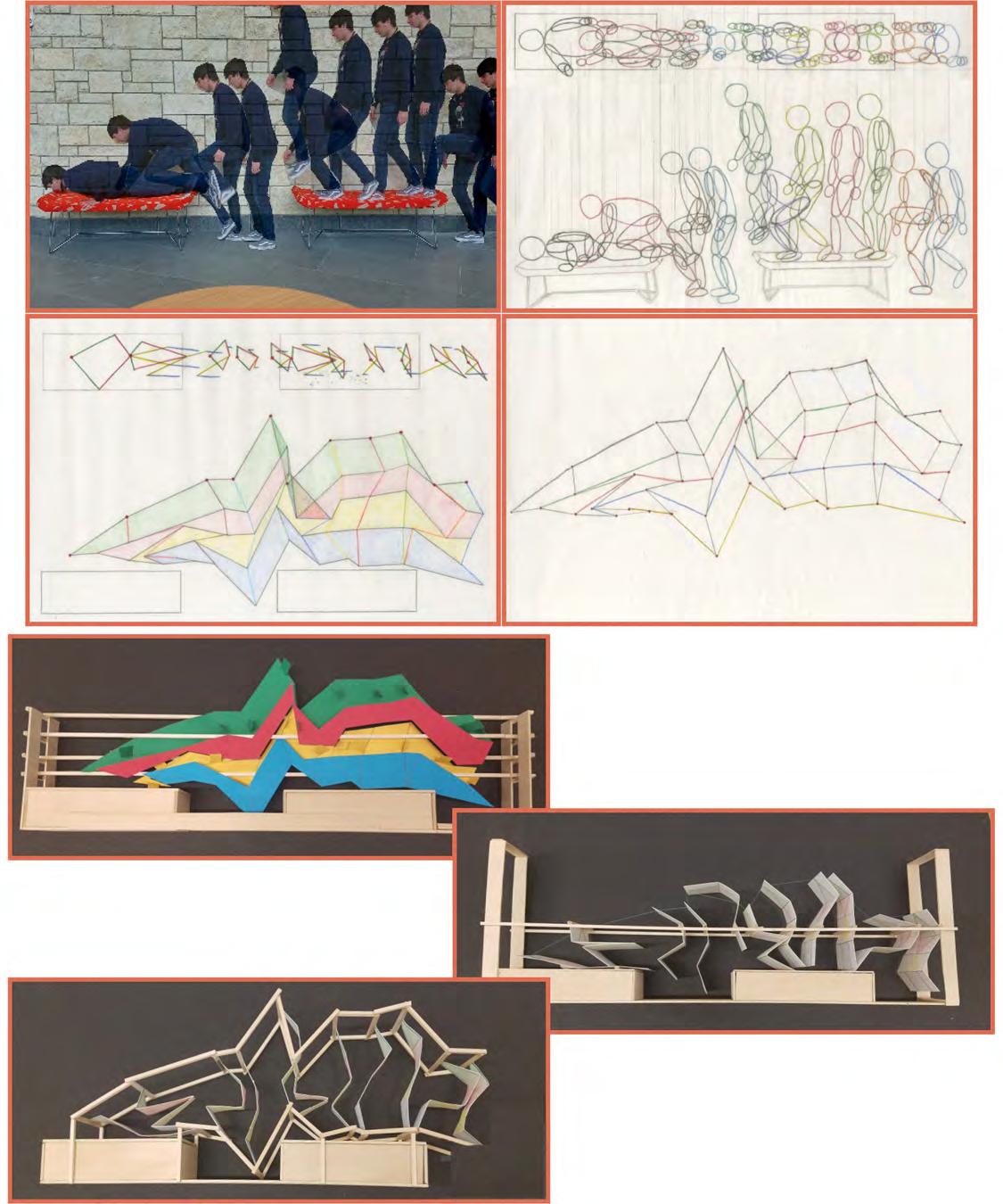

1. SCALE/MOTION… documenting and analyzing human motion.

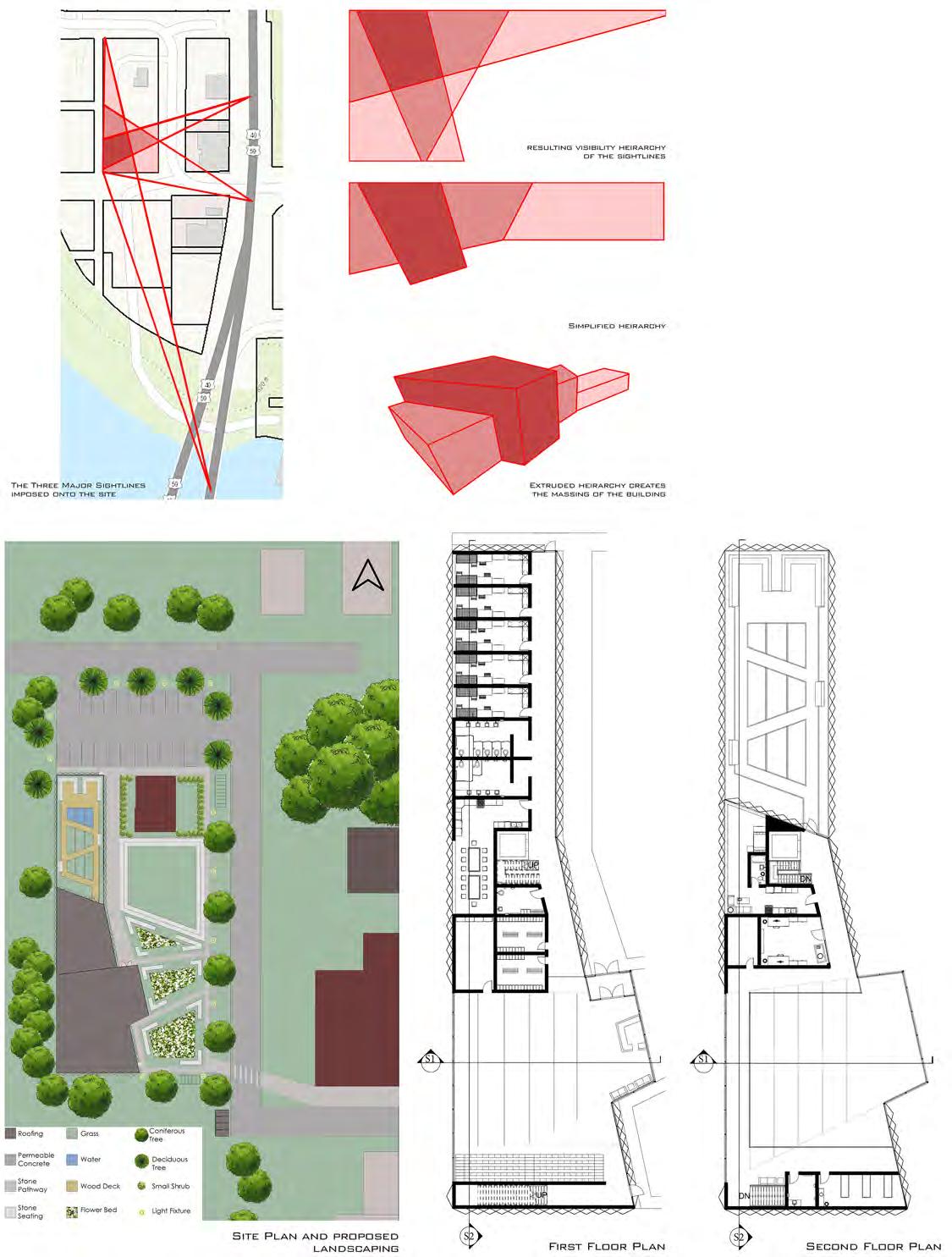

2. THE LAST CARNIVAL … working with reality

-SITE STUDIES… studying context and finding “place”

-PRECEDENCE STUDIES… look to the past to move forward

SELECTED STUDENT WORK: Brooke Pogue

Nikola Braynov

We began the semester with an exploration of highly specialized movement as it interfaces with design. A contortionist must move their body in a range of flexible positions not natural to most humans. As part of our semester of study of the relationship of space and how human movement shapes architecture, we started with a small piece of performance furniture.

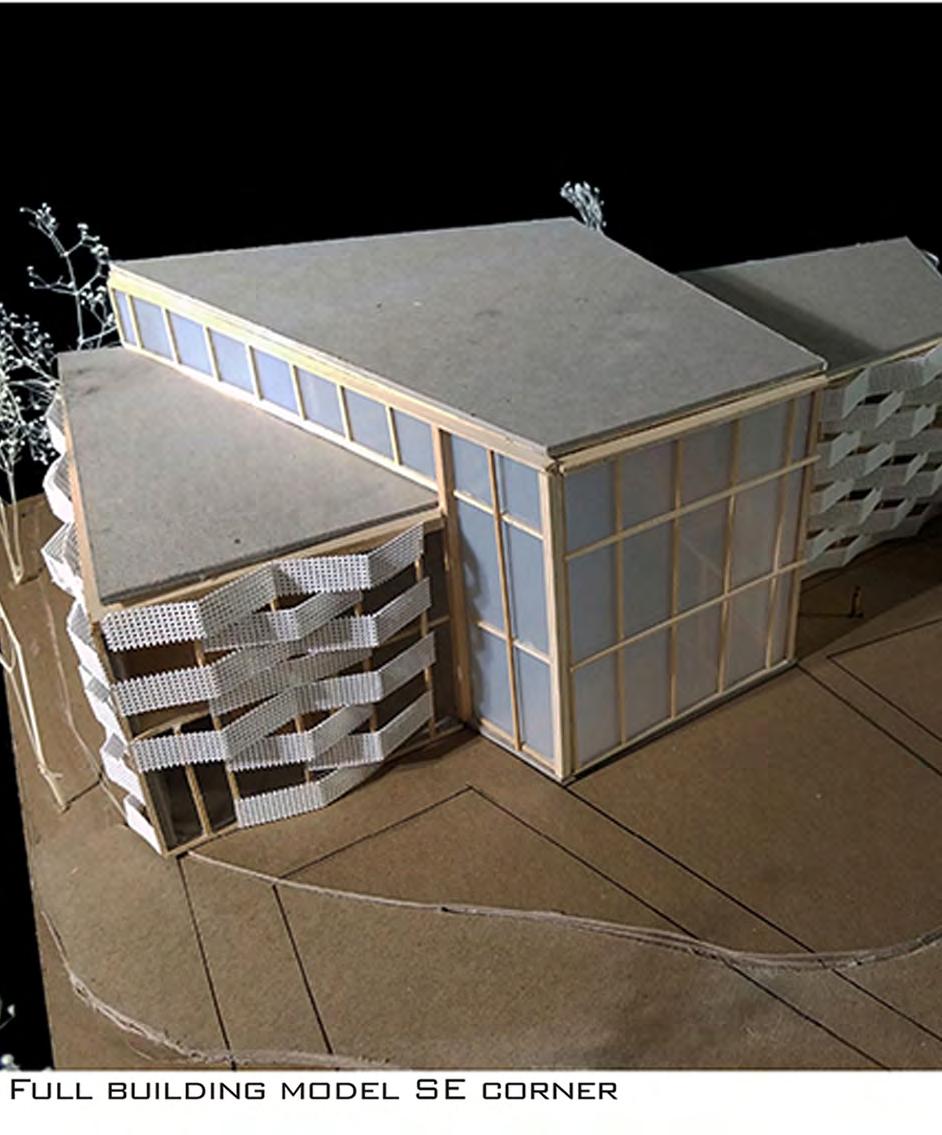

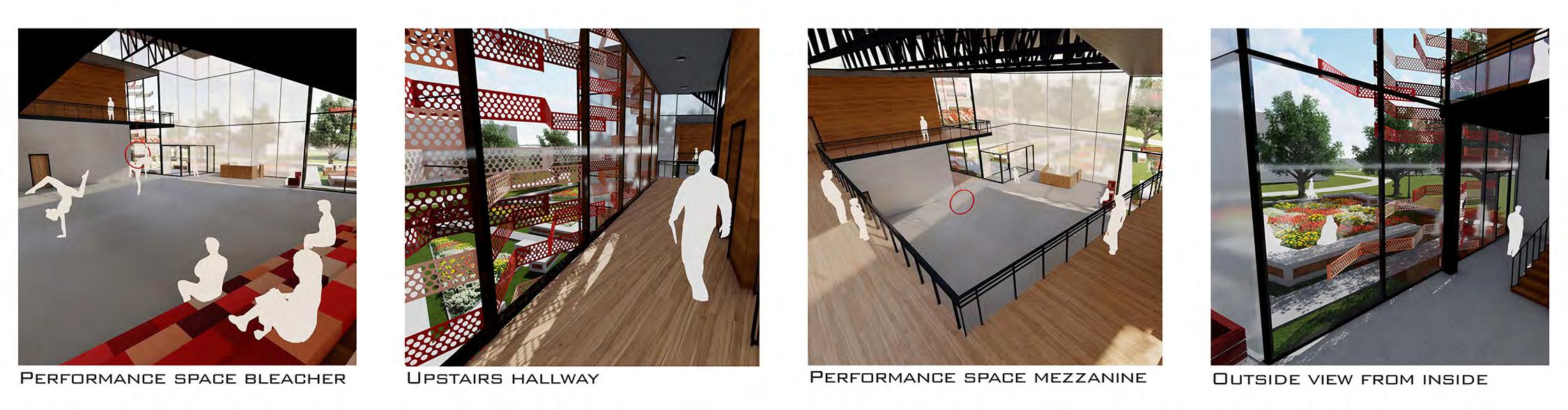

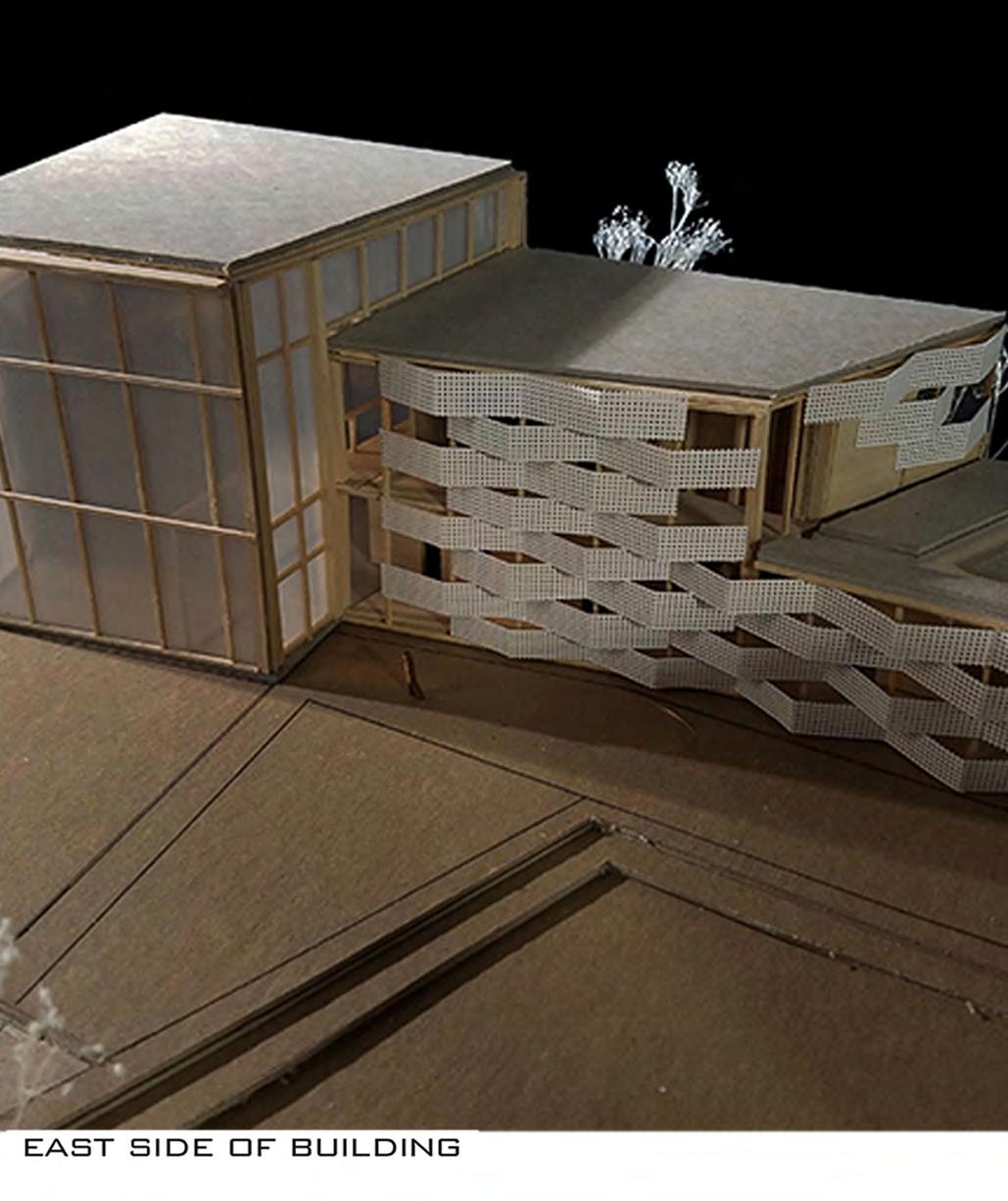

We created architectural ideas for a real business in Lawrence, KS. The Last Carnival is a circus arts school founded and owned by Sihka Ann Destroy. Previously located in the intersection of Locust Street and North 2nd Street in Lawrence, KS, the school has been relocated to east Lawrence. Students prepared ideas and inspiration for the owner to consider as possibilities for future development.

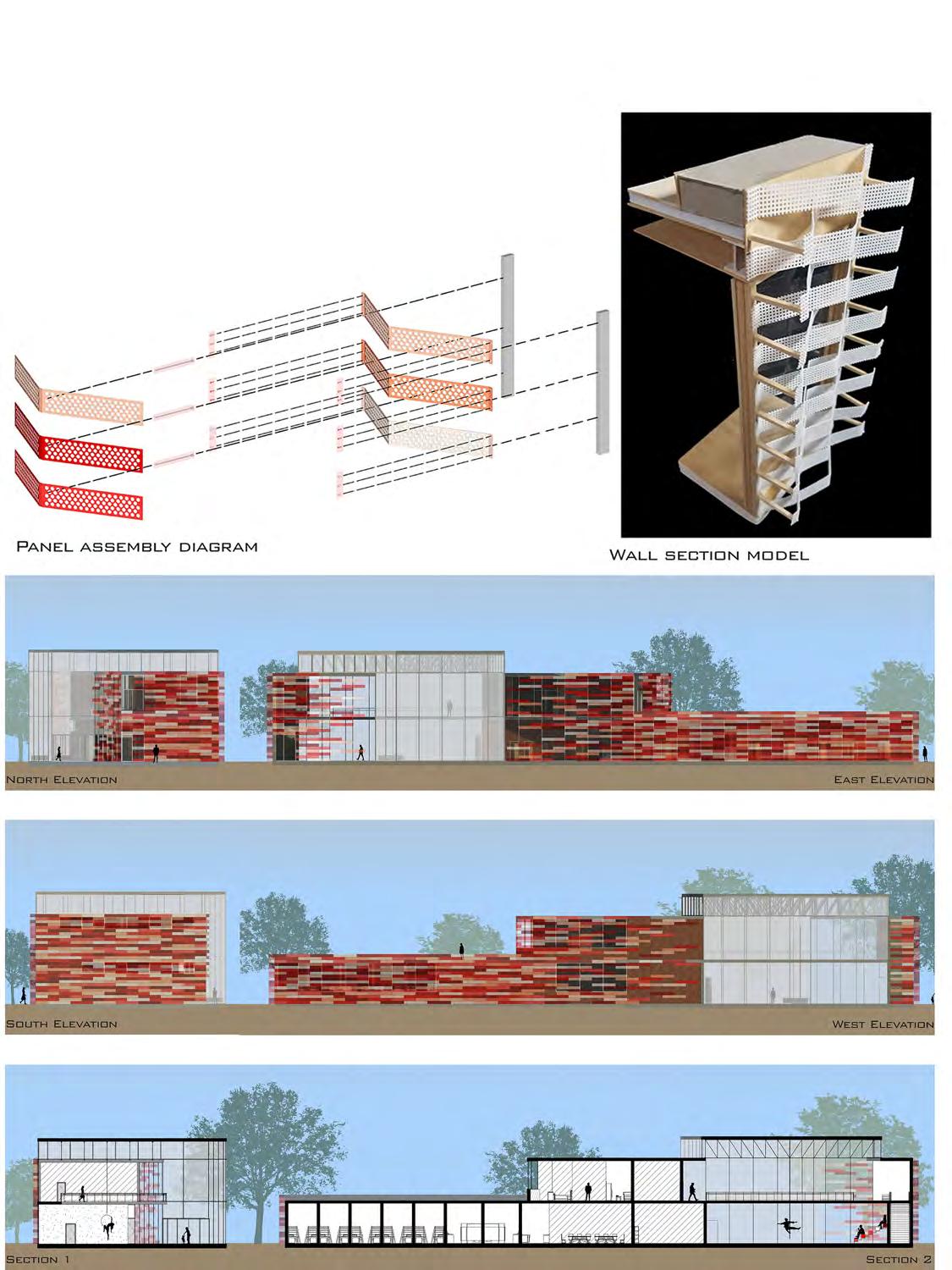

Students utilized working with physical models and digital models in their building design. Different types of building materials were studied, and the construction of the building envelope was analyzed both digitally and physically in model form. The impact of the building skin and how it controls natural light into the different spaces was also studied and integrated into the design.

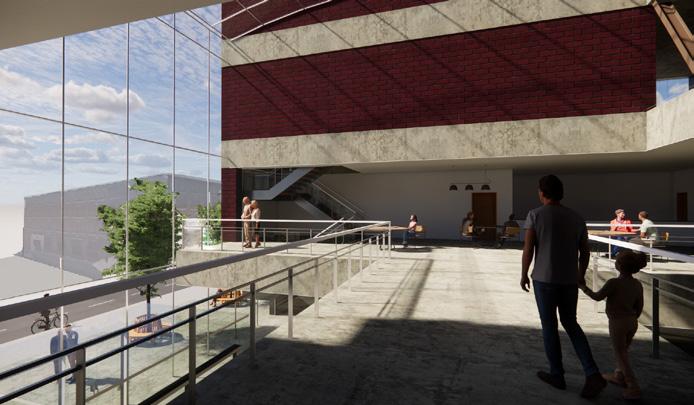

A continuation of the Architectural Studio sequence with major emphasis on studies in urban spaces and design development of building envelopes as related to urban public-life, structural and mechanical systems, and principles of sustainability. Students shall work individually on an advanced building design. Work will focus on medium scale, multi-story, urban-infi ll buildings developed to an appropriate level of technical resolution as evidenced in clear schematic wall sections and structural proposals. Students shall demonstrate an understanding of formal ordering and building-concept development as related to the tectonic form determinants.

Prerequisite: ARCH 209/502.

NAAB Criteria (National Architectural Accreditation Board)

NAAB Criteria (National Architectural Accreditation Board)

Admission to the M.Arch program leads to a degree that is fully accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) and meets the certification requirements of the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB).

Arch508 covers the 2020 NAAB Criteria:

PC. 2 Design

PC. 2.1 Design thinking skills

PC. 2.2 Investigative skills

PC. 2.3 Architecture Design Skills

PC. 2.4 Ordering Systems

PC. 2.5 Use of Precedents

PC. 2.6 Integrate multiple factors at different scales of development, from buildings to cities

PC. 3 Ecological Knowledge & Responsibility

PC. 3.1 Holistic understanding of the dynamic between built and natural environments

PC. 3.2 Design to mitigate climate change responsibly

PC. 5 Research & Innovation

PC. 5.1 Research

PC. 8 Social Equity & Inclusion

PC. 8.1 Further and deepen understanding of diverse cultural and social contexts

PC. 8.2 Translate understanding of diverse cultural and social background into built environment

Understanding

SC. 1 HSW in the Built Environment

SC. 1.1 Human health, safety, and welfare at buildings’ scale

SC. 1.2 Human health, safety, and welfare at cities’ scale

SC. 3 Regulatory Context

SC. 3.1 Life Safety SC. 3.2 Land Use SC. 3.3 Codes and Regulations SC. 3.4 Site Design

SC. 4 Technical Knowledge SC. 4.1 Technical Documentation SC. 4.2 Structural Systems SC. 4.3 Environmental Systems (B.6) SC. 4.4 Building Envelope Systems and Assemblies SC. 4.5 Building Materials and Assemblies

Pre-Ability Level

SC. 5 Design Synthesis SC. 5.1 Design Decisions that Demonstrating Synthesis of Multiple Factors SC. 5.2 User Requirements SC. 5.3 Regulatory Requirements SC. 5.4 Site Conditions SC. 5.5 Ecological Concerns and Consider Measurable Environmental Impacts SC. 5.6 Accessible Design

SC.6 Building Integration SC. 6.1 Integrated Decision-Making Design Process SC. 6.2 Integrating Building Envelop Systems

As we initiate ARCH 508 we shall engage the historical, current and future understanding of the urban environment of downtown Wichita, Kansas. The complex racial injustices of this Midwest city are part of the broader understanding of white settler-colonialism, segregation, and ongoing discrimination for BIPOC and LGBQTIA+ identifying peoples.

As the population grows, the need to establish and maintain strong communities becomes imperative to sustain the quality of life for a broad base of participants. A place to explore and share ideas of smart growth - sustainable both in terms of being environmentally responsive and equitable in accessibility to everyone is part of the balance of regenerative design. A growing concern for “gentrification” can create friction in a community and warrant divisive growth of an area.

This semester our site will focus on an urban in-fill in the downtown vicinity of Wichita, Kansas. The site will be analyzed as part of the studio project. The “Center for Equitable and Sustainable Design” will be a combination of the center, apartments and other supporting programmatic areas. The idea will be to provide an inclusive experience where Wichita’s historical past can participate in its future.

Now, more than ever, Tectonics (building pieces) are imperative to understand what is a safe and flexible built environment. We shall investigate solid vs. porous and how thoughtful component selection allows a building to breath naturally with intentional manipulation atmospheric forces.

SELECTED STUDENT WORK: Orla Lamb

Summer 2018

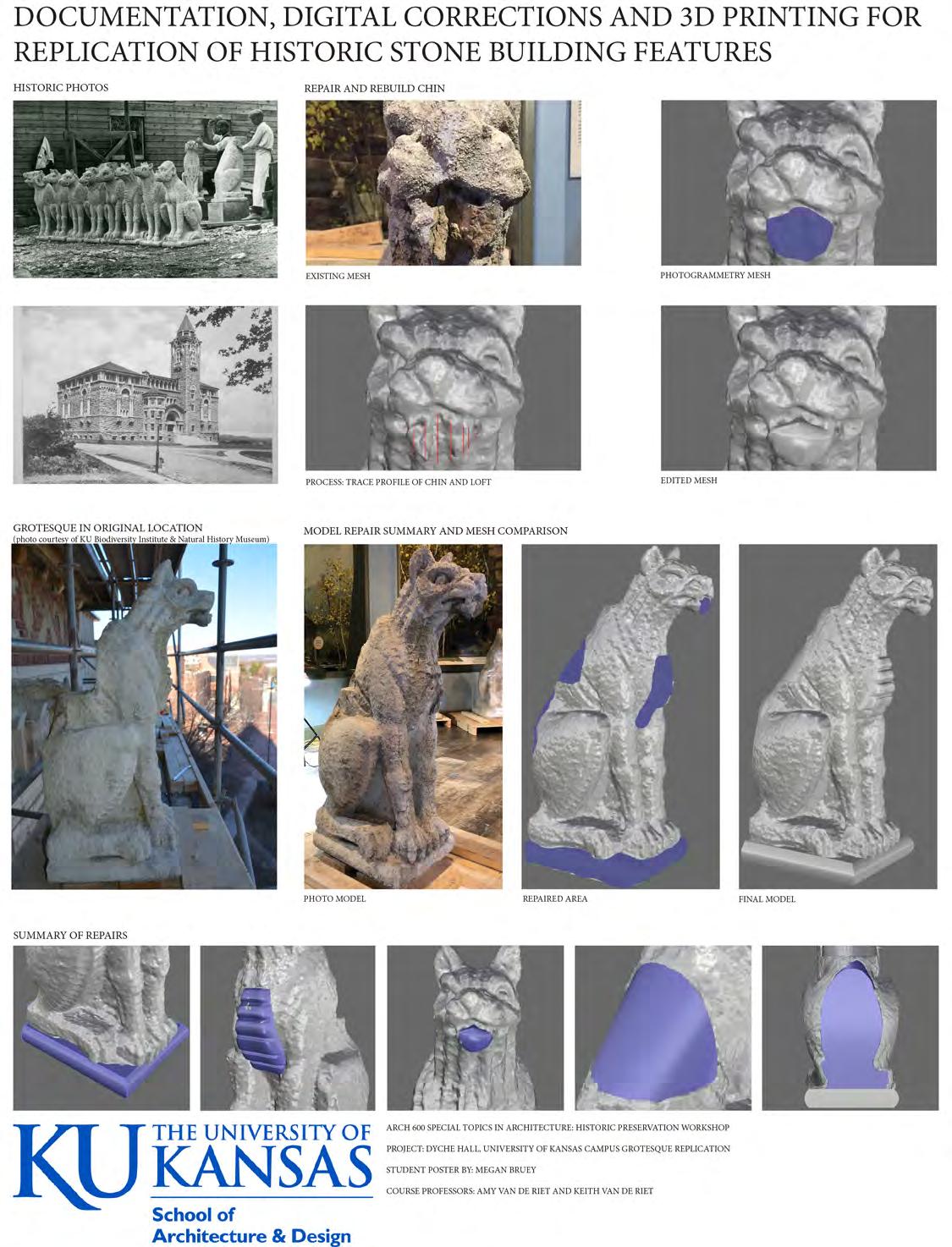

We will be pursuing an understanding of how technology can assist in the craft and replication of historic artifacts. As noted, this is an educational framework applied to a professional project. In 2017 it was determined that the grotesque statues on Dyche Hall at the University of Kansas were deteriorated beyond repair. They have been relocated inside Dyche Hall, but KU wishes to replicate them in their original condition and install the new grotesques at the original locations on the building. This workshop is the first step in the process. We will be scanning the grotesques, correcting and “repairing” the digital meshes in Rhino software using historic photos for reference. Upon completion of the digital models, small scale 3D prints of the grotesques will be made. The stone carvers (Karl and Laura Ramberg) will use the 3D prints as their maquettes in creating the new sculptures in Cottonwood Limestone (the original stone used for the historic grotesques).

1. EXISTING CONDITION DOCUMENTATION… taking dimensions, photos and recording deterioration of the grotesque statues after their removal from the exterior of Dyche Hall.

2. PHOTOGRAMMETRY...utilizing photogrammetry technology, each grotesque will be 3D scanned and a digital model of the historic grotesque will be created.

3. DIGITAL REPAIRS...using Rhino software, each digital model of the grotesque will be “repaired” and prepared for 3D printing.

4. OUTCOMES...3D models of each grotesque will be printed in PLA at 1/4 scale of the original. These maquettes will be given to the stone carvers for their use.

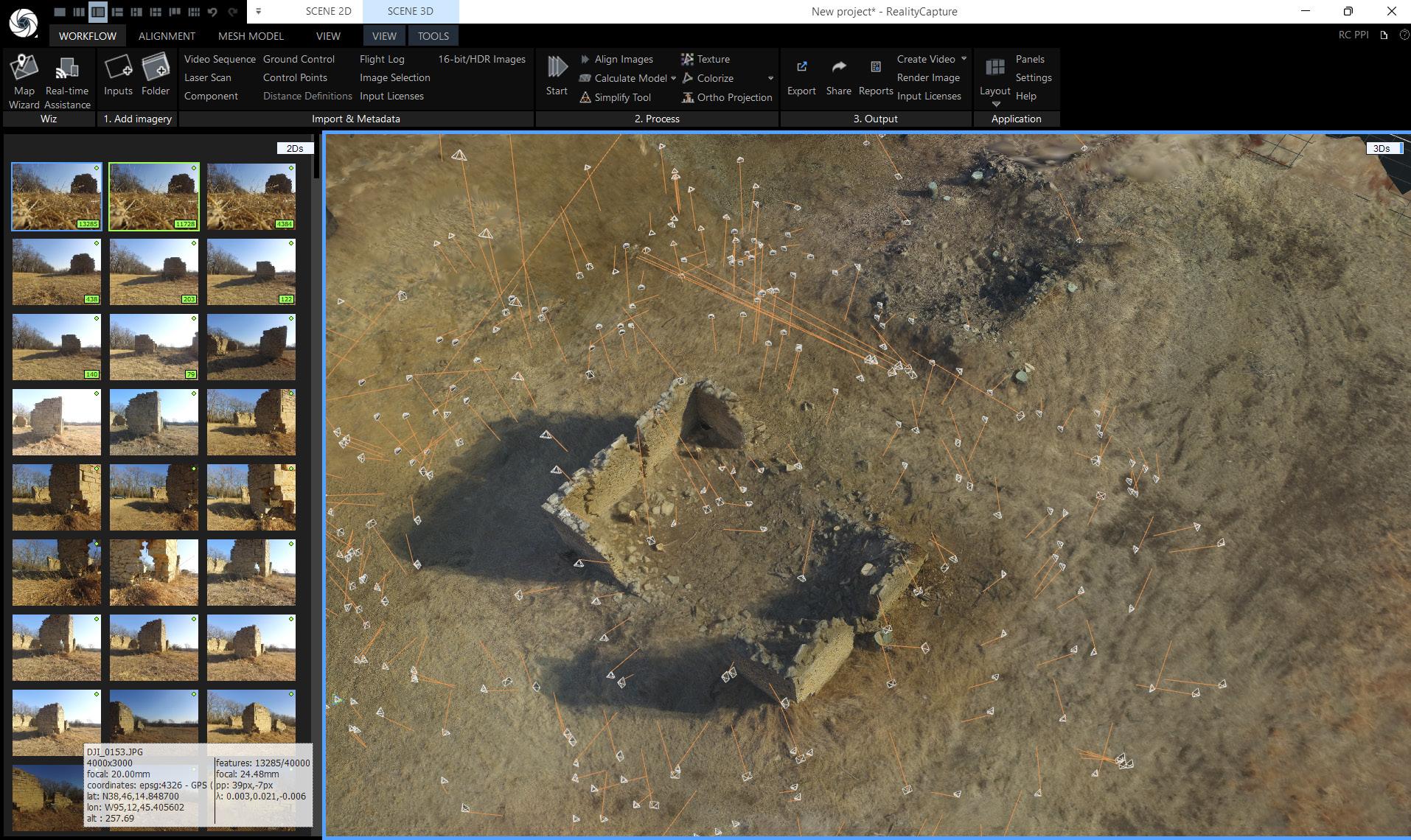

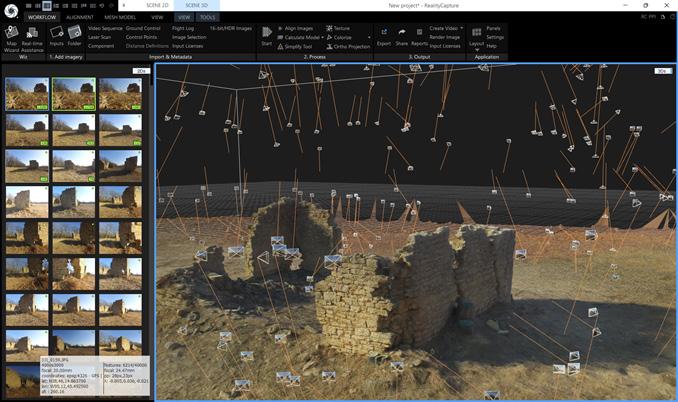

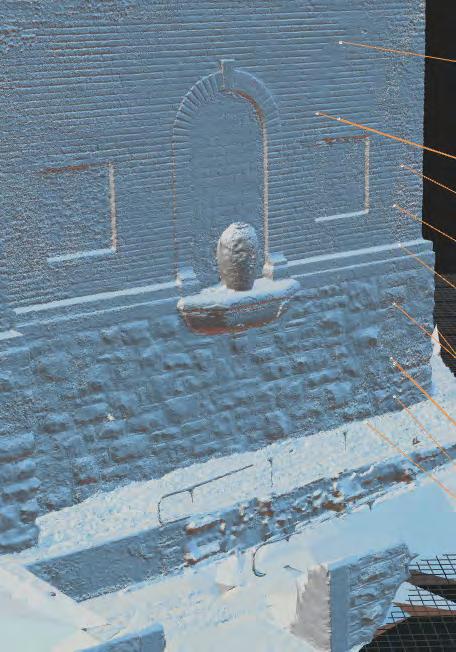

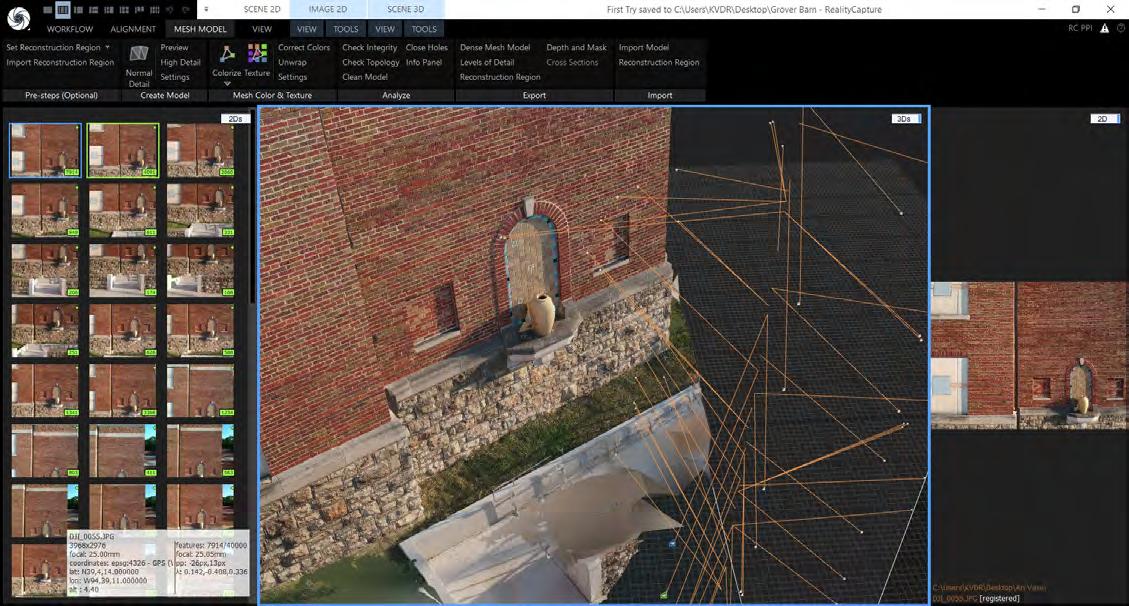

SELECTED STUDENT WORK: Megan Bruey Student Poster of Work from the Arch 600 Class Presented by student at the KU School of Architecture and Design Architectural Symposium Fall 2019The class will be organized into three different scanning case studies: scanning the entire exterior of a historic building using drone technology, scanning interior spaces using photogrammetry, scanning the newly completed stone Grotesque sculptures at Dyche Hall. Each of these case studies will lead to the student’s choice of Final Project based on their own interests.

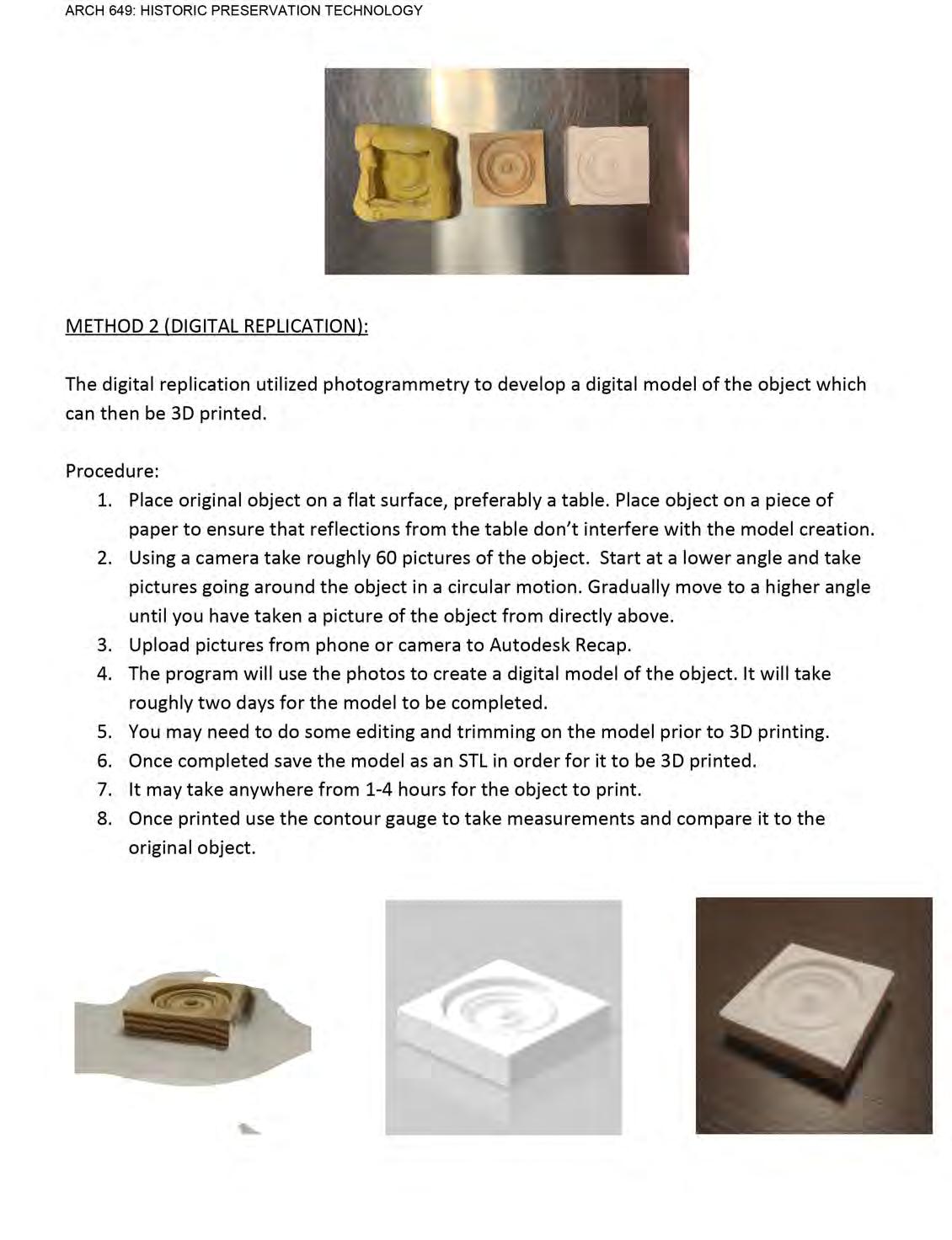

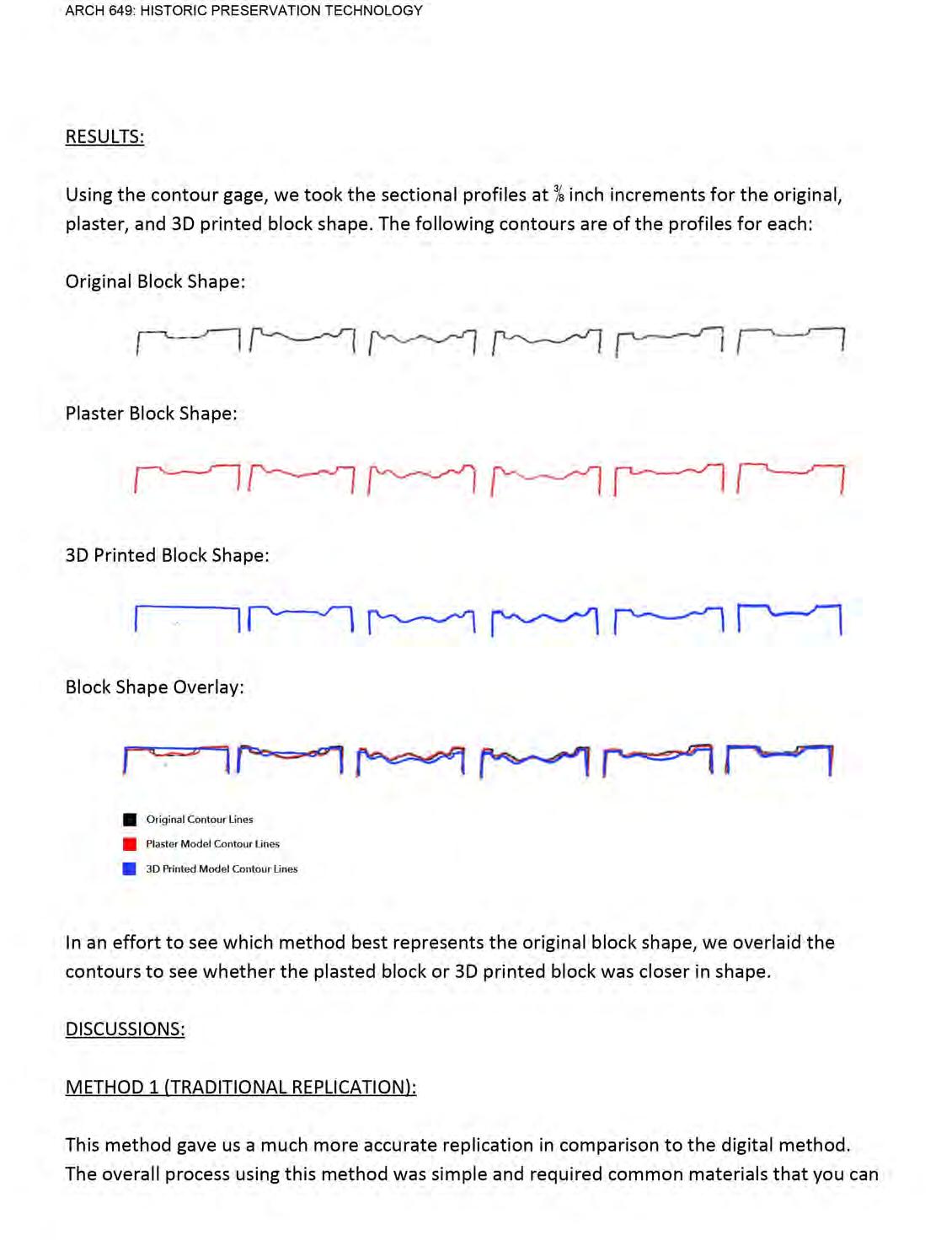

The purpose of Project 1: Replication is to introduce students to traditional replication procedures and digital replication techniques. Students are expected to select a simple object and 3D scan it using photogrammetry. Using Autodesk ReCap, a 3D model will be created. We will then 3D print the model (to scale if applicable).

The purpose of Project 2: 3D Models of Buildings and Space is to introduce students to using photogrammetry to scan interior spaces, and using drones to scan building exteriors. Students are expected to select a room and 3D scan it using photogrammetry. Using Autodesk ReCap, a 3D model will be created. We will also (as a class) be using drones to 3D scan building exteriors. Students should watch the videos (or attend in person), and see the entire process of scanning the exterior of buildings.

The purpose of the Final Project: Creative Interventions is to allow students the opportunity to explore their own ideas and creative experimentations using photogrammetry. Students can choose an exercise similar to the Project 1 and Project 2 studies, or they can explore some other idea they are interested in. Students can also expand on the 3D models created during class (exterior building drone scans and the Grotesque scans).

SELECTED STUDENT WORK: Ari LeyvaThe student used a drone to take multiple photos of an architectural detail outside of a building. We used the software “Reality Capture” to create a photogrammetry model from the photos.

This course introduces students to architectural historiography and preservation technology. It covers a range of curatorial issues in preservation and adaptive reuse of historic buildings. The topics include technical documentation of historic buildings, archival research, causes of decay in historic buildings, assessment of preservation needs, selection of preservation strategies, and techniques of building material preservation. Also covered are the integration of sustainable technologies into historic construction and examination of the ecological advantages of adaptive reuse and preservation.

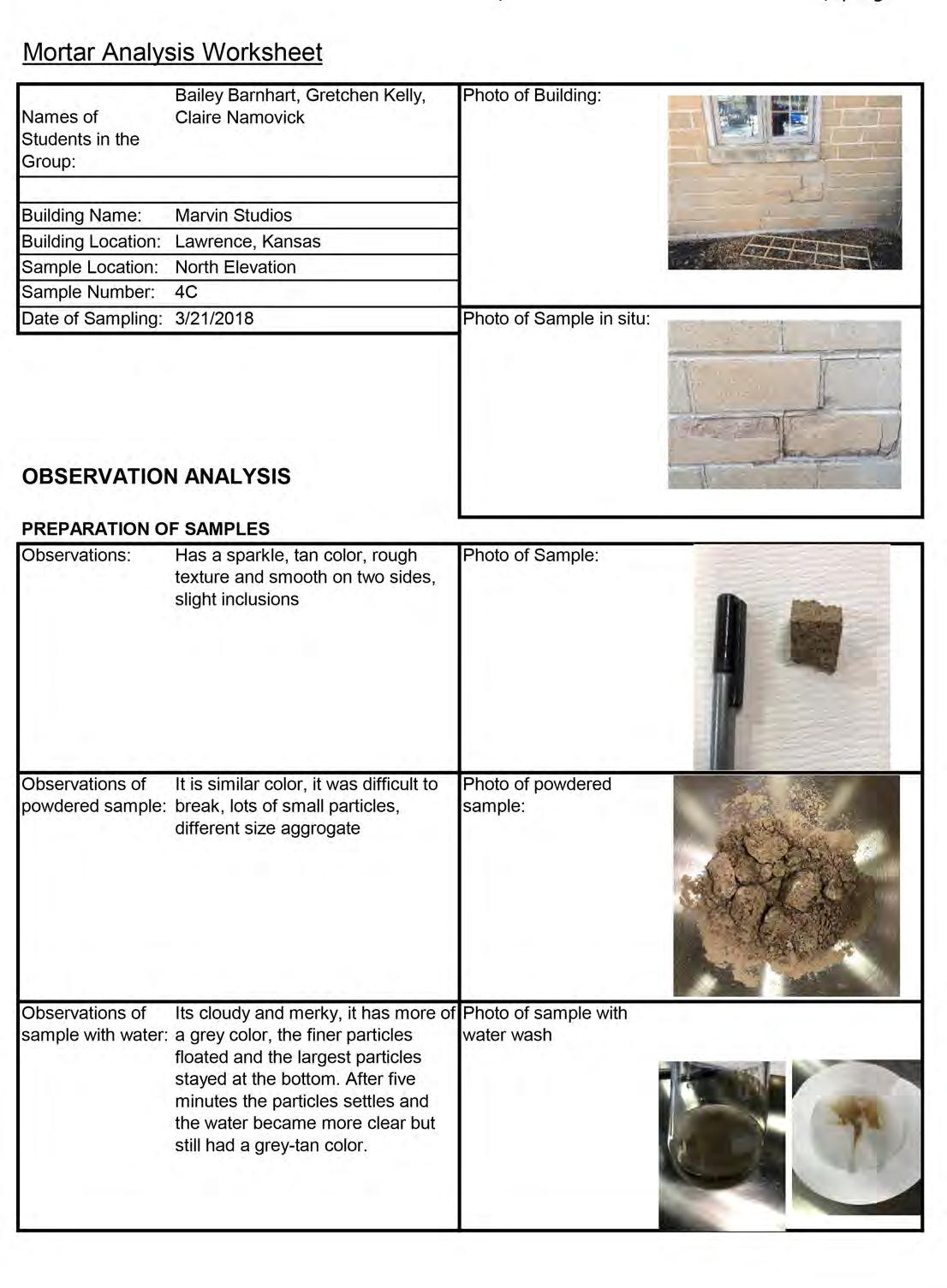

The purpose of the Basic Mortar Analysis experiment is to introduce students to a simplified version of a mortar analysis.

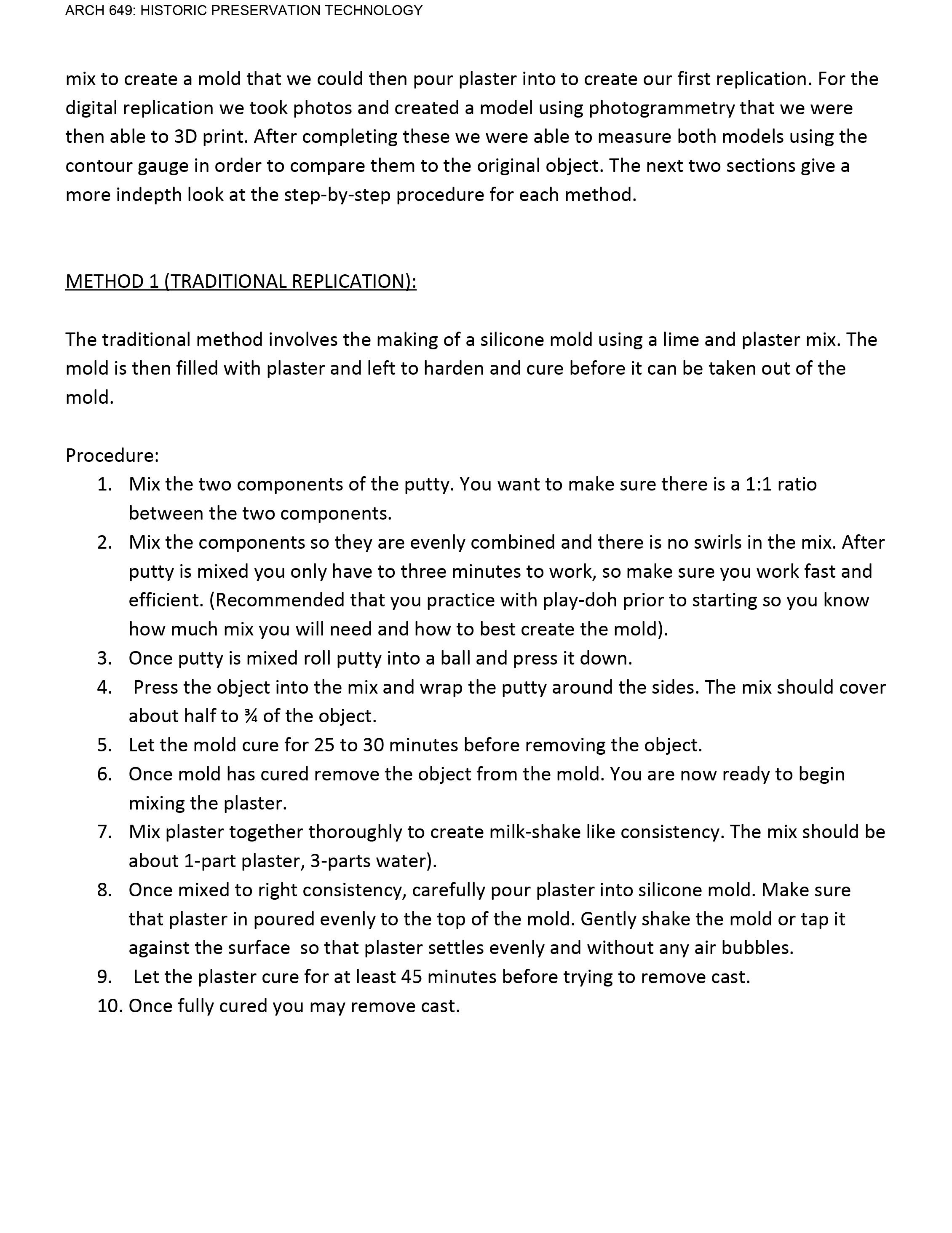

The purpose of the Replication Analysis is to introduce students to traditional replication procedures and compare the results to digital replication techniques. Students are expected to work in teams of two. Each team is to select an object (approximately 3”x3” in size), replicate the object with traditional replication procedures, replicate the object with digital replication techniques, and then compare the results. Student groups will format results into a paper using the Scientific Research Paper format.

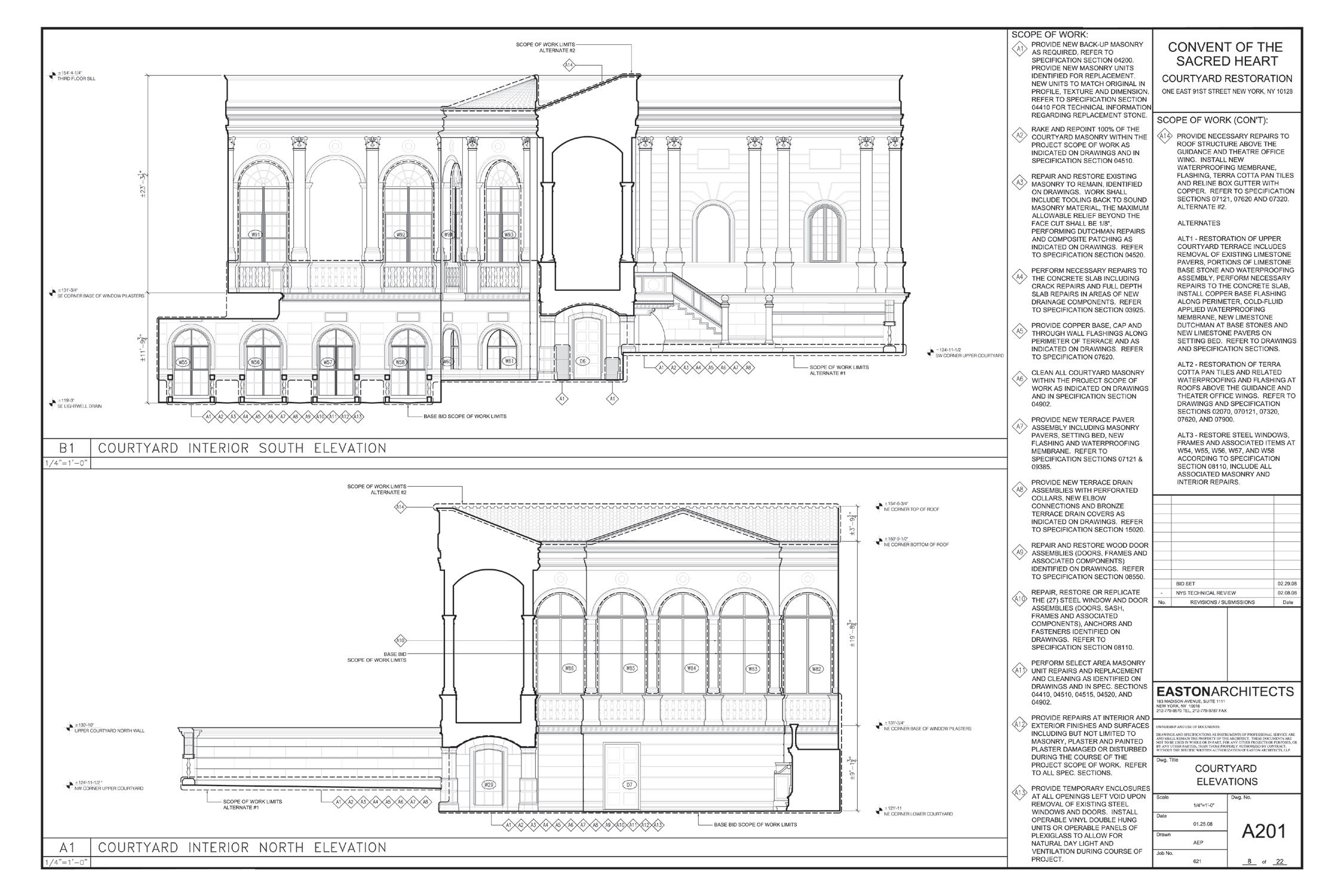

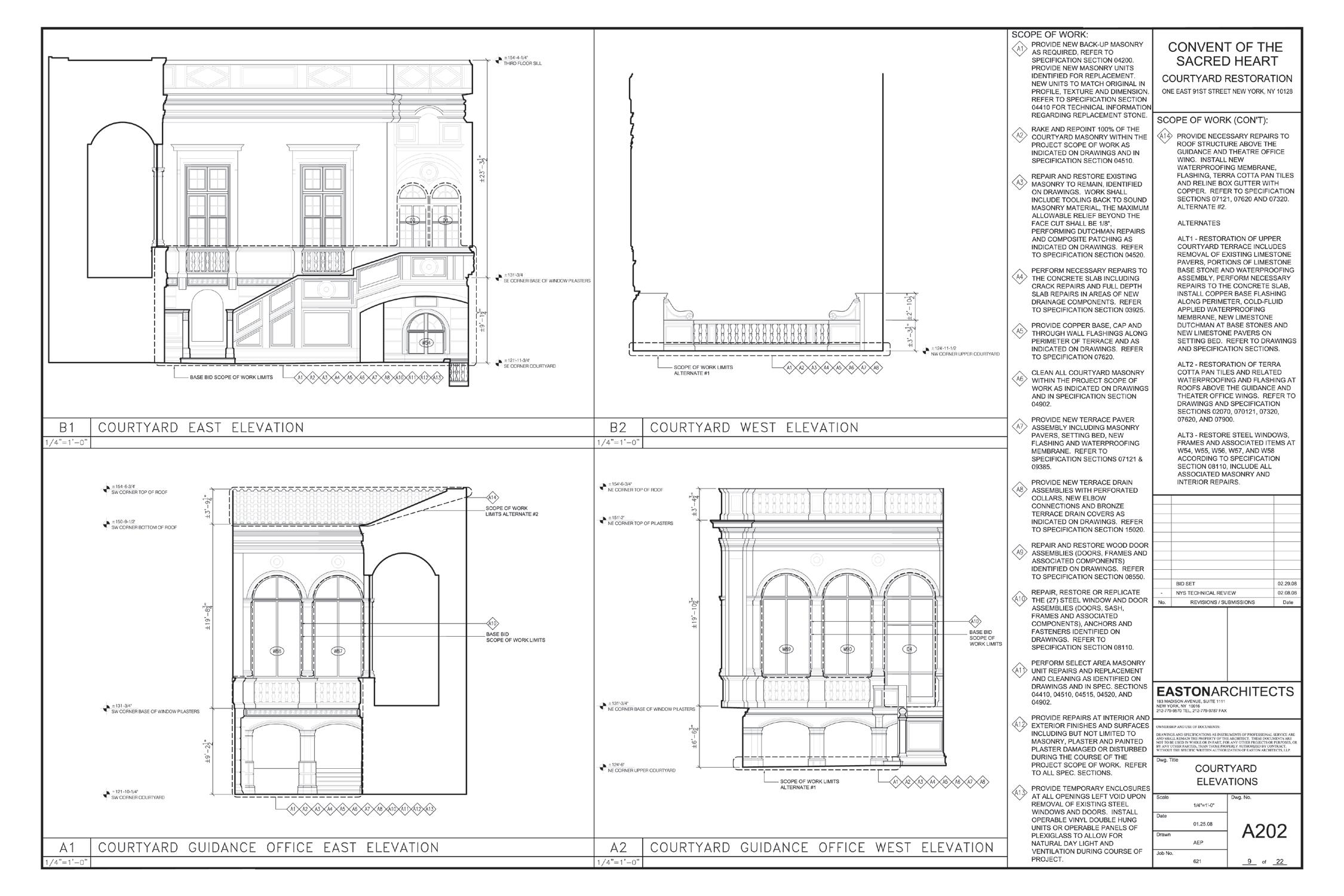

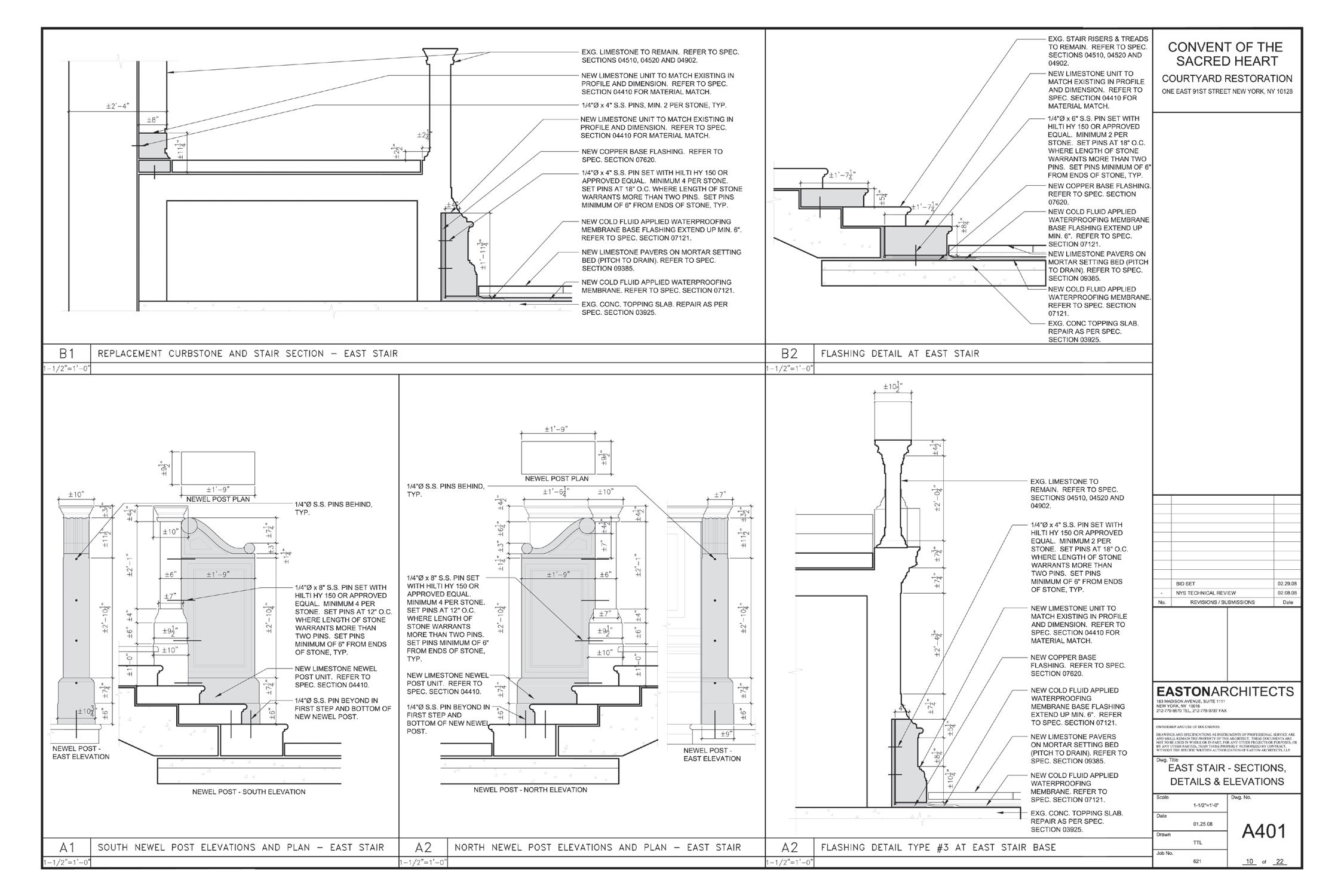

PROJECT: Courtyard Restoration of the Otto Kahn House, Convent of the Sacred Heart School

PROJECT LOCATION: 1 East 91st Street, NYC

Client: Convent of the Sacred Heart School

Preservation Architect: Easton Architects, LLP

-Lisa Easton, Partner

-Amy (Peterson) Van de Riet, Designer

-Tellina Lui, Intern

Structural Engineer: Robert Silman Associates

Conservator: SUPERSTRUCTURES

Restoration Contractor: DNA Contracting & Waterproofing LLC

Contractor – Steel Window Restoration: Seekircher Steel Window Repair Corp.

Contractor – Glazing Fabricator/Installer: Custom and Historic Windows

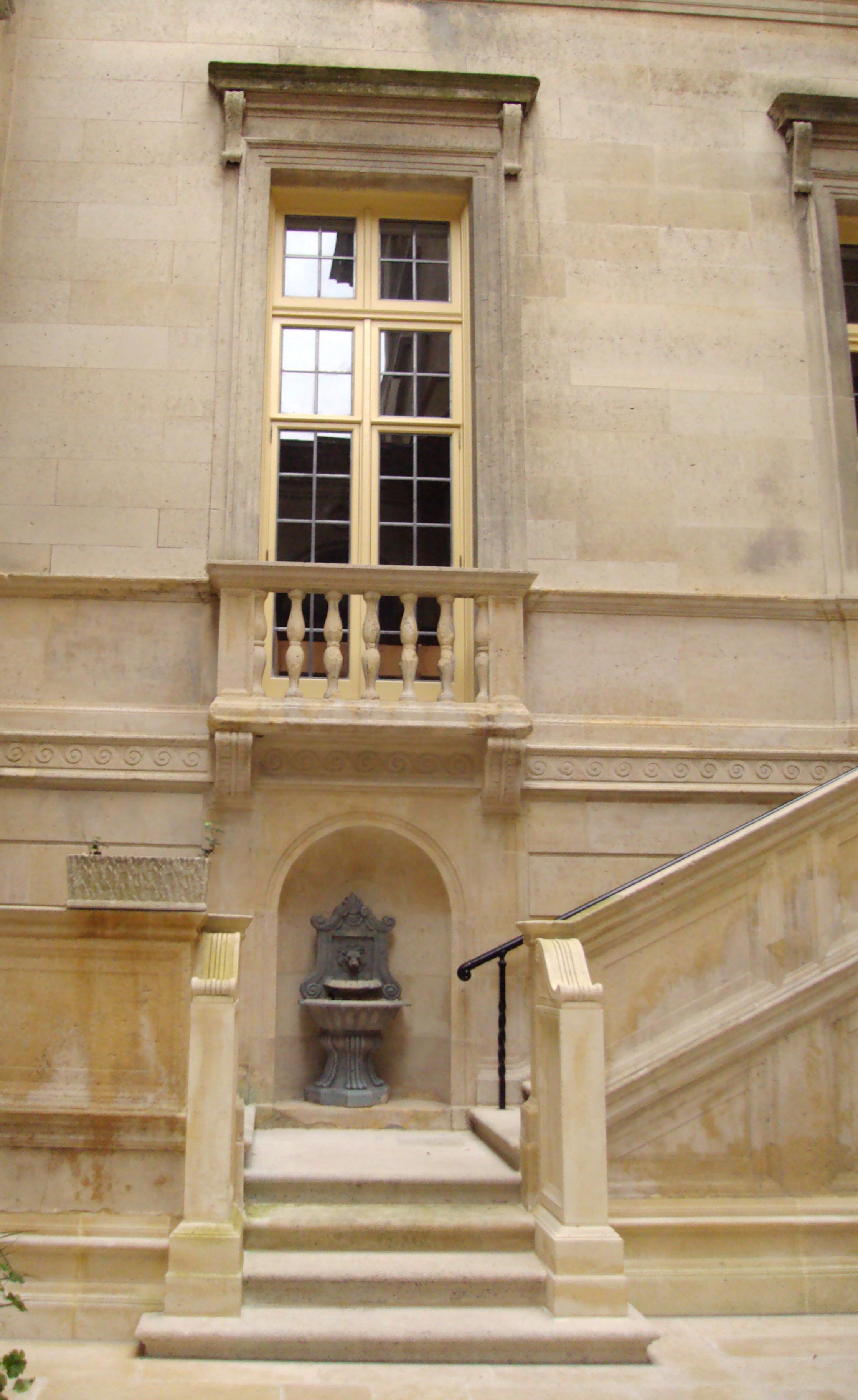

The Convent of the Sacred Heart School (CSH) of New York, occupies the Otto Kahn and James Burden houses which were acquired by the school in 1934 and joined to house the lower, middle and upper school functions for grades pre-K through 12. The buildings are located in the New York City Carnegie Hill Historic District, they are individual New York City Landmarks and have been recognized for their architectural and historical significance through listing on the New York State and National Registers of Historic Places.

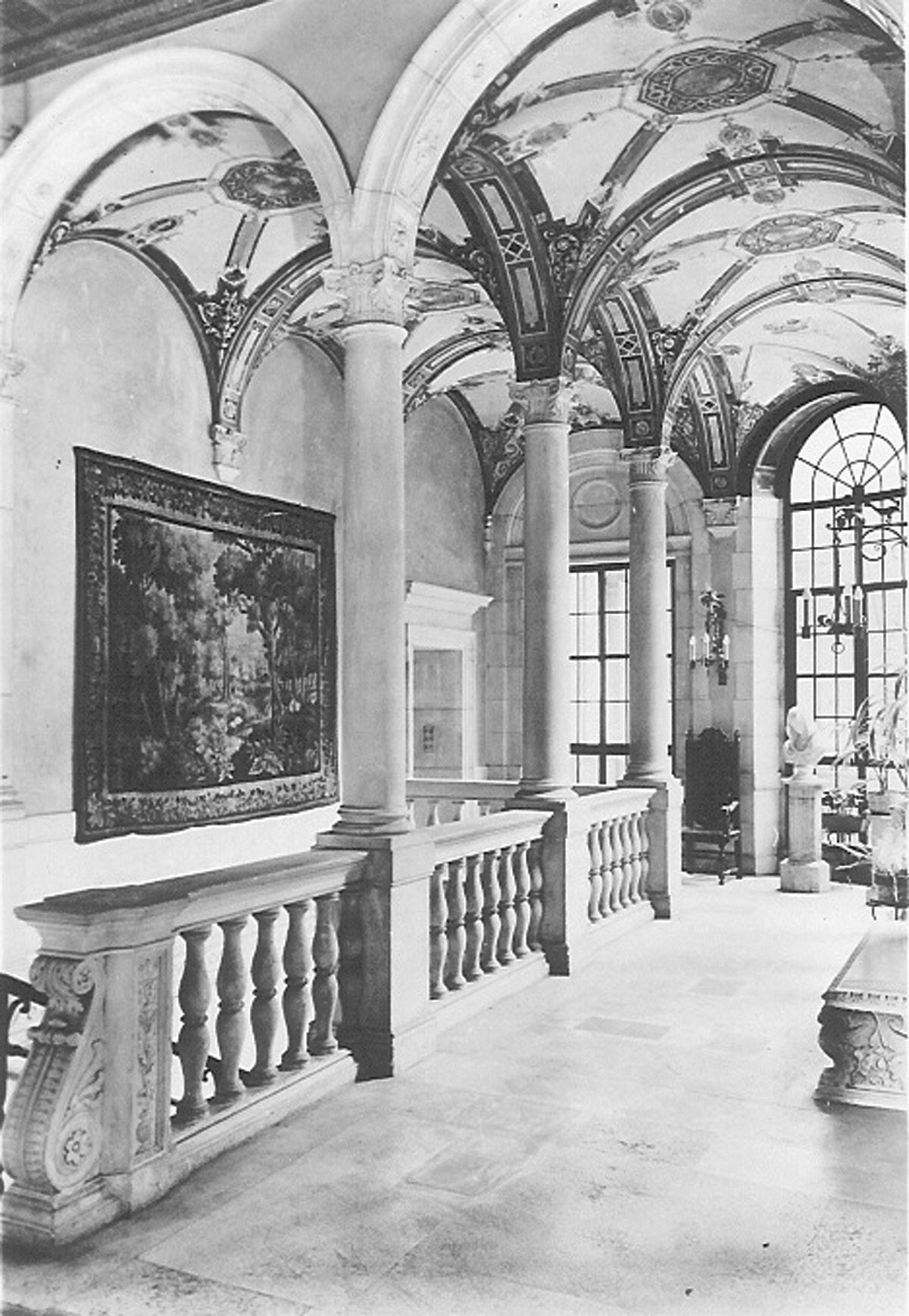

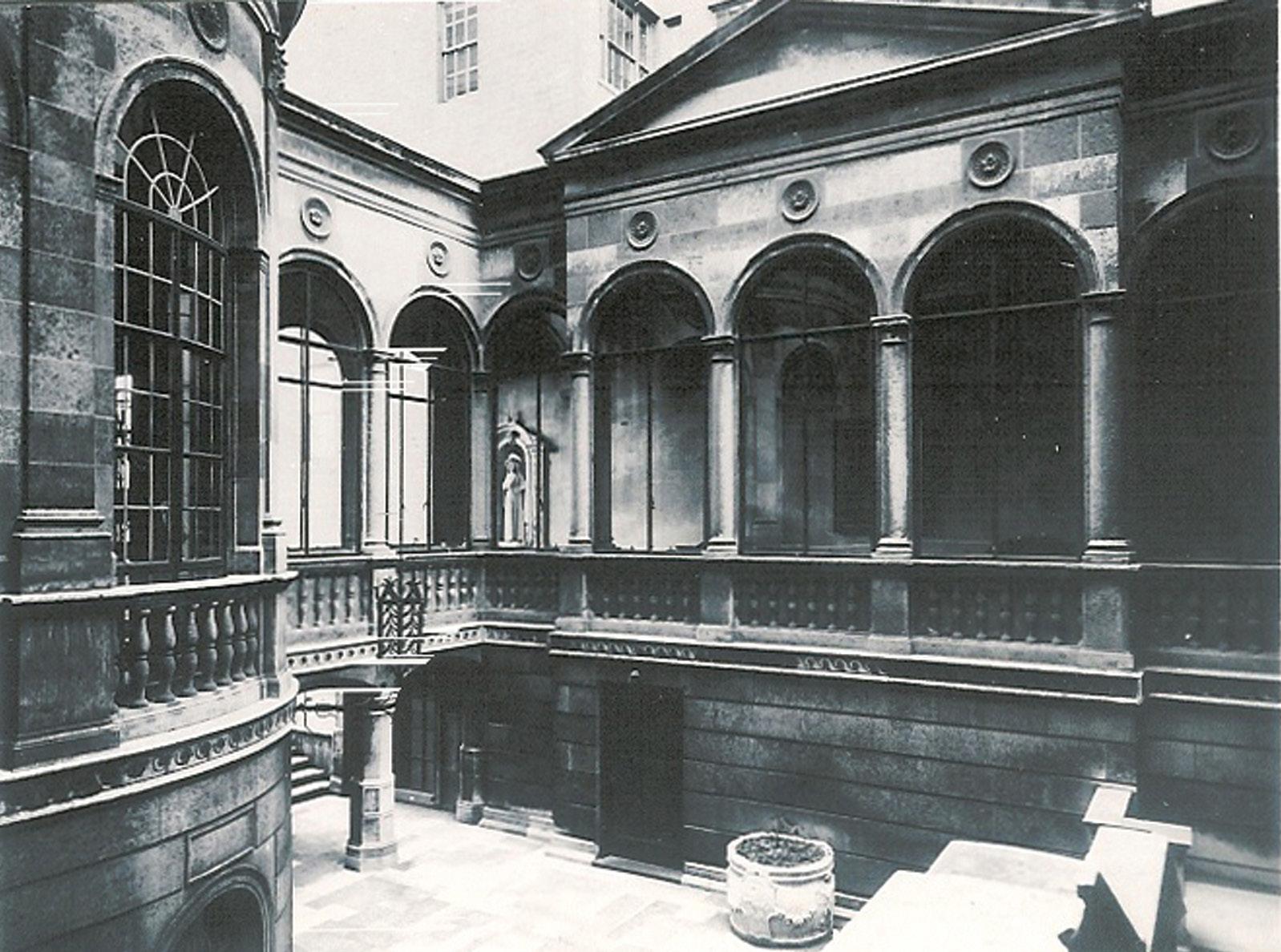

The Otto and Addie Kahn House, located at 1 East 91st Street on the corner of Fifth Avenue, built between 1913 and 1918, was designed by the noted British architect J. Armstrong Stenhouse with C.P.H. Gilbert acting as associate architect. The Kahn House is a four-story, neo-Italian Renaissance palazzo, modeled on the Palazzo Cancelleria in Rome. The sophisticated design and refined detailing make the Otto Kahn House one of the finest Italian Renaissance style mansions built in New York City.

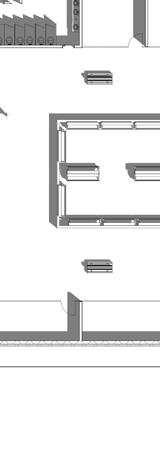

The project scope of work included the restoration of the courtyard including masonry restoration, metal restoration, wood door restoration, steel window and door restoration and replication, installation of waterproofing, flashing and drainage components, terrace restoration and terra cotta roof restoration. To accommodate the school’s schedule, work took place over the summer breaks only requiring the work to be phased over the course of two summers. Removal and disassembly work was phased during Summer 2008 and installation and restoration work was completed in Summer 2009.

The scope of work for the steel window restoration and replication consisted of the restoration of one steel and leaded glass doors 10’-1” x 4’-7”; fourteen steel and leaded glass windows varying in size from 5’-0” x 4’-6” to 15’-6” x 4’-6” with arched top transom panels, six of these units curve in plan as well. Windows and doors at the second floor Guidance Office and Theatre Office wings were replicated by Hope’s Windows, the original fabricator of the windows. There were 3 steel and leaded glass doors varying in size from 7’-11” x 3’-2” to 14’-5” x 5’-8”, and nine steel windows 11’-2” x 5’-6” with arched top transom panels.

New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation - Environmental Protection Fund

Historic photos of courtyard (top), interior hall (left) and exterior of the building from 5th Avenue looking northeast. Photos courtesy Convent of the Sacred Heart archive.

Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award, New York Landmarks Conservancy 2010 Preservation Award, Friends of The Upper East Side Historic Districts 2010

Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award, New York Landmarks Conservancy 2010 Preservation Award, Friends of The Upper East Side Historic Districts 2010

The courtyard restoration for CSH began with a Window Survey and existing condition survey executed as part of the Existing Conditions Assessment and Master Plan for the Convent of the Sacred Heart.

The Existing Condition Assessment of the courtyard revealed that the terrace surface was essentially flat and was covered in a heavy film of biological growth indicating long-term moisture saturation. The terrace drains were the original solid cast units that collect water only from the terrace surface. Due to the excessive moisture, the stone had eroded away leaving the drains at the high point of the terrace and completely ineffective. The terrace assembly consisted of limestone on a setting material on top of the original roofing membrane with areas of patch repairs done with EPDM roofing membrane. There was no base flashing at the intersection of the vertical building walls and the terrace allowing water to infiltrate the walls and the sills surrounding the courtyard.

The courtyard sits in the shade of the building most of the year and therefore never receives direct sunlight preventing it from properly drying. The terrace assembly was not effective and not watertight allowing water to penetrate through to the structural slab assembly. The lack of base flashing at the building edges led to severe deterioration of the limestone walls, sills, window surrounds and excessive corrosion of the steel windows and frames.

The masonry deterioration included sections of spalling, sugaring, exfoliating and severely weathered stone, large cracks, open joints and significant amounts of biological growth adhering to the stone.

The Window Survey determined the state of deterioration of the windows ranged from extreme to moderate. The extent of deterioration was the result of age, usage, long-term exposure to the elements and minimal maintenance. Many of the windows were inoperable, were bolted shut because of the fragile state of the frames and sash, glass breakage routinely occurred when the windows blew open and smashed against the building because they could no longer be secured shut and there was no longer operable hardware to control the position of the windows as they deformed, warped and no longer closed. The weatherstripping was no longer weathertight. The glazing putty was scaling and disintegrating. The severe deterioration of the windows had compromised the watertight integrity of the building envelope.

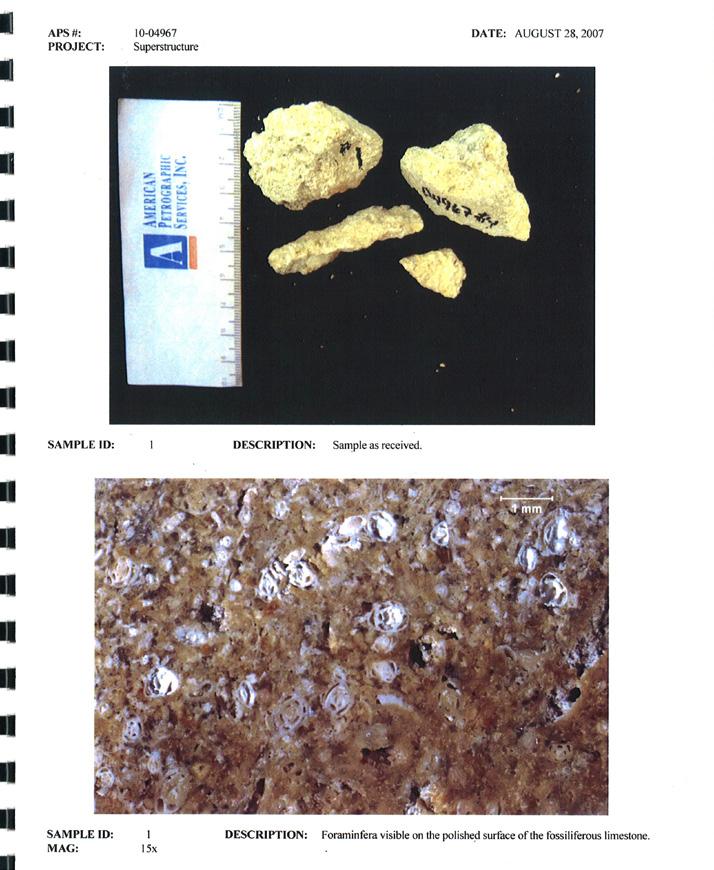

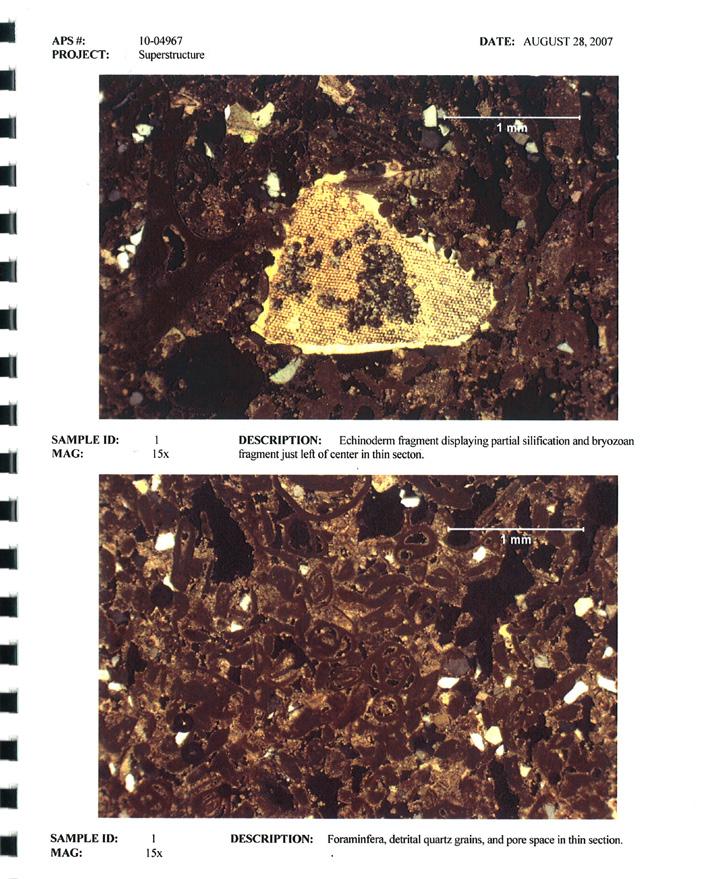

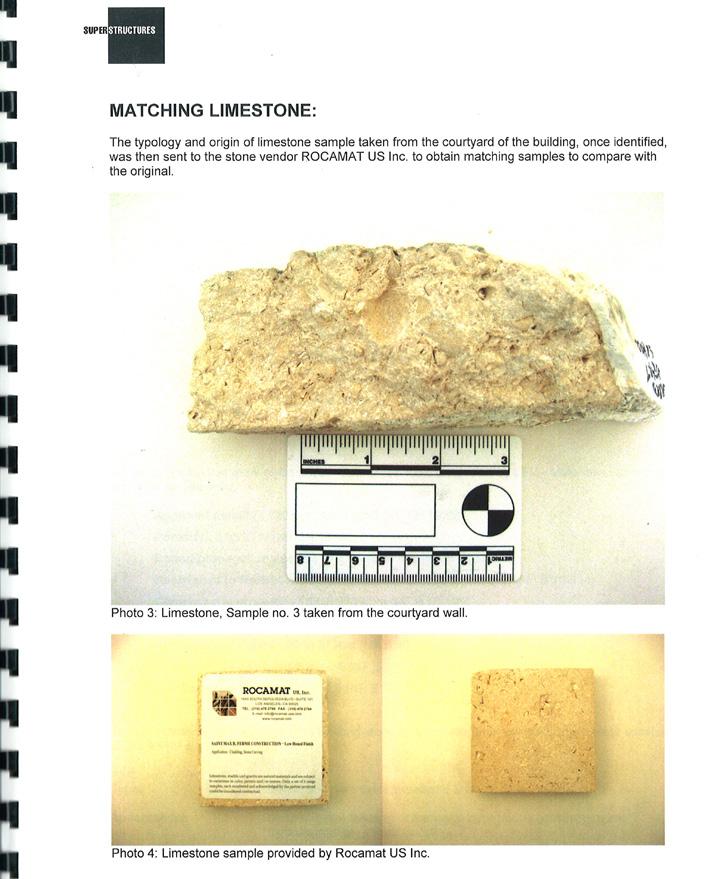

Conservation testing was performed and included testing on the original limestone to understand the compressive strength and porosity which assisted in determining compatible replacement stone for the courtyard restoration and future work related to the masonry cladding. This analysis determined an exact match of the original stone to the Saint-Maximin Ferme Construction and Saint-Maximin Franche Construction as quarried in the Picardie region in Northern France which is where all replacement stone came from. Mortar analyses was also conducted to characterize the historic mortars, separate components, determine weight percentages, view original aggregates and formulate the most appropriate replication mixes.

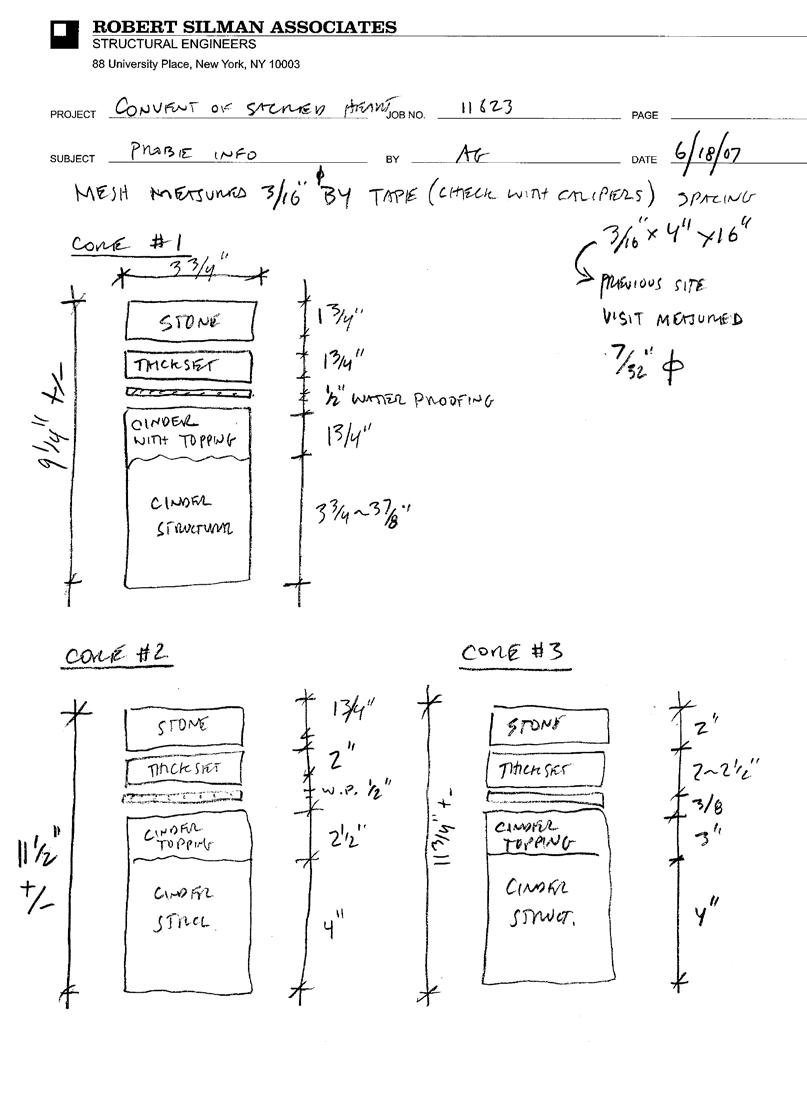

The structural analyses included observation of the conditions of all exposed existing structural elements identified through probes. As part of this investigation the structural engineer reviewed available original drawings and historic photographs. They also examined the exposed structural elements for areas of structural damage associated with water infiltration. As part of the structural analysis, three probe and core locations were located and core samples were analyzed by mechanical testing to determine structural integrity. The exposed structure was documented to create a structural framing plan of the courtyard.

Finally, through cleaning tests it was determined to use the gentlest means possible to clean the masonry using the Rotek Vortex system which uses a very low pressure water wash (30psi) combined with compressed air and an aggregate. The end result is a very natural clean to the stone without over-cleaning or scarring the stone.

The scope of work for the courtyard terrace and roofs included removal and disassembly of masonry units at the base of the wall along the entire perimeter of the courtyard; identification of each terrace paver (size and location) and removal of the terrace assembly including all setting materials and waterproofing down to the concrete slab. Removal of existing terrace drains and all associated components including but not limited to drain covers, drain bodies, elbow connections was required. In addition the existing terra cotta pan tile roof assembly, waterproofing, flashing and underlayment on the roof of the Guidance and Theatre Office Wings was removed. The installation of new waterproofing membrane at the courtyard terrace and roofs of the Guidance and Theatre Office wings was completed.

In total, nearly 1000 square feet of terrace pavers were documented and recreated. There was approximately 120 linear feet of carved limestone base stone at the perimeter of the Courtyard that was replicated precisely to match the original profiles and dimensions. Over 30 linear feet of new curb was set at the lightwell at the south portion of the Courtyard and select replacement of the limestone at the lightwells and staircase was also completed. All new stones were anchored to the existing fabric with stainless steel attachments.

Work completed during the summer of 2008 included disassembly of all limestone perimeter base stones and select decoratively carved stones along the stair, lightwells, balustrade and columns. The entire limestone terrace assembly was removed down to the concrete slab. All necessary structural repairs were made to the concrete, new waterproofing membrane, flashing and drainage was installed. In addition the terra cotta tile roof was disassembled and significant repairs were made to the underlayment prior to the installation of new waterproofing and flashing. The steel windows identified for restoration were completed. The months between summers were used to produce detailed shop drawings and fabricate all new limestone units, new steel windows and new terra cotta tile.

During the summer of 2009, the new limestone units were installed, all with stainless steel anchors. The limestone pavers were installed, matching the original pattern exactly (no two stones are the same size). The new steel windows and doors were installed. The ornamental ironwork was restored. The terra cotta tile roof was completed and the two existing wood doors were restored on site. All courtyard masonry was cleaned at the completion of the installation work using a very gentle and environmentally friendly cleaning process, and the project was finished by the start of school in September 2009.

During the course of the Window Survey work, all 23 steel frame windows, 4 steel frame doors, and 2 wood doors within the courtyard were identified and documented for replication or restoration. The associated masonry repairs and flashing replacement also needed to be replaced/restored in order to address the failing conditions of the materials and inappropriate and ineffective detailing original to the design and construction which, if left unaddressed would have continued to undermine the stability and safety of the window assemblies and compromised the integrity of the historic building fabric of this landmark structure.

Aside from the size and diversity of the windows themselves, one of the most challenging obstacles was to improve the performance of the restored and replicated windows while preserving the original characteristics and historic appearance of each window type. The steel framed windows were upgraded to have laminated glass with low E coating within the lead came assembly, an ambitious undertaking as a new method of assembly had to be developed to combine the lead caming with the modern laminated glass. Through analysis of mockups submitted by the contractor and working in close collaboration with the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, the methodology was approved and utilized to create the new window glazing assemblies.

With the change to laminated glass with low E coating, the school has benefited from the improved safety factor of laminated glass over single pane glazing, ideal in a school environment. Additionally the new assembly has improved energy efficiency, the ability to internally apply a low E coating reduces the UV light transmission through the glass, which is healthier for the children, faculty and staff and also helps protect the historic fabric of the interiors. The sound absorption is three times better than the single glazed option.

The lifespan of the new windows is estimated at 100 years of serviceable life, and the investment in improving their efficiency without at all compromising the aesthetic has been achieved.

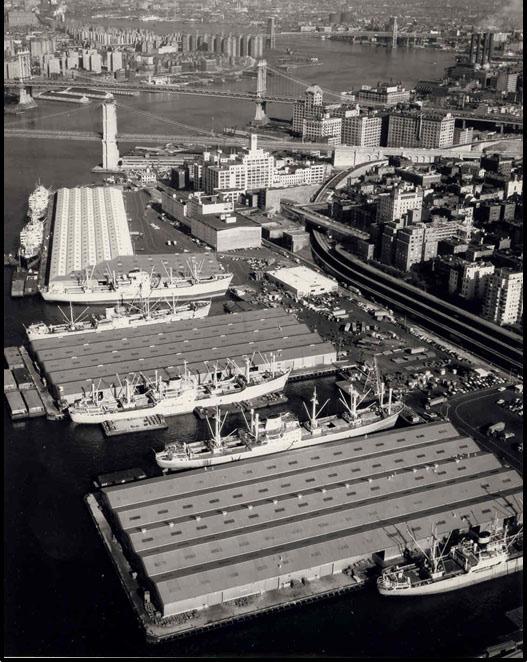

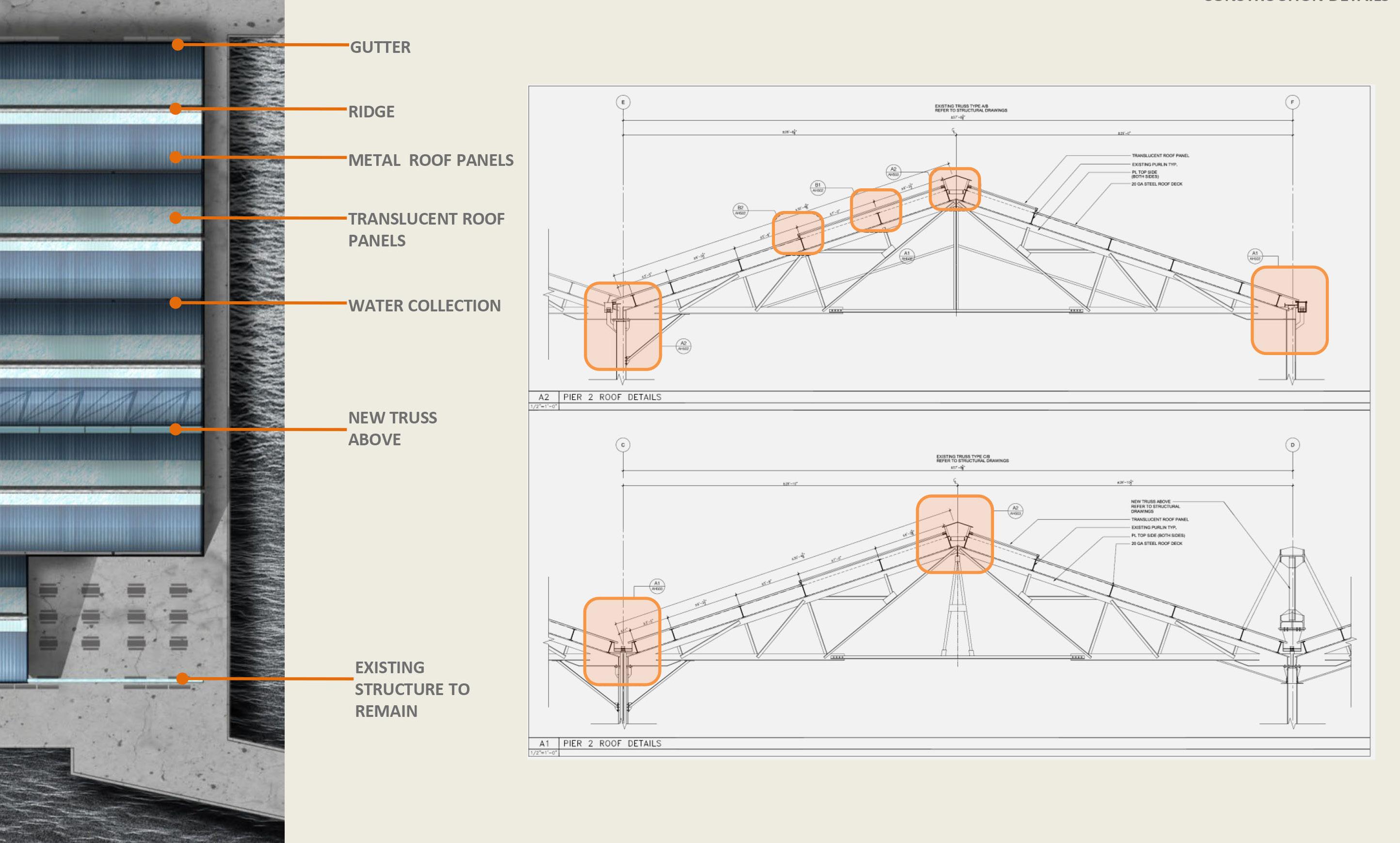

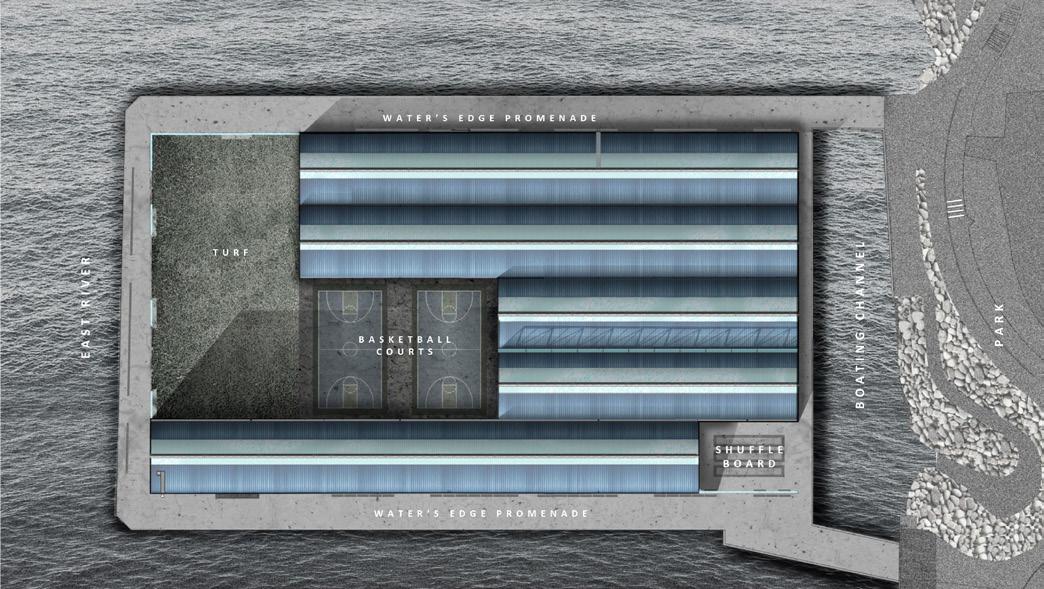

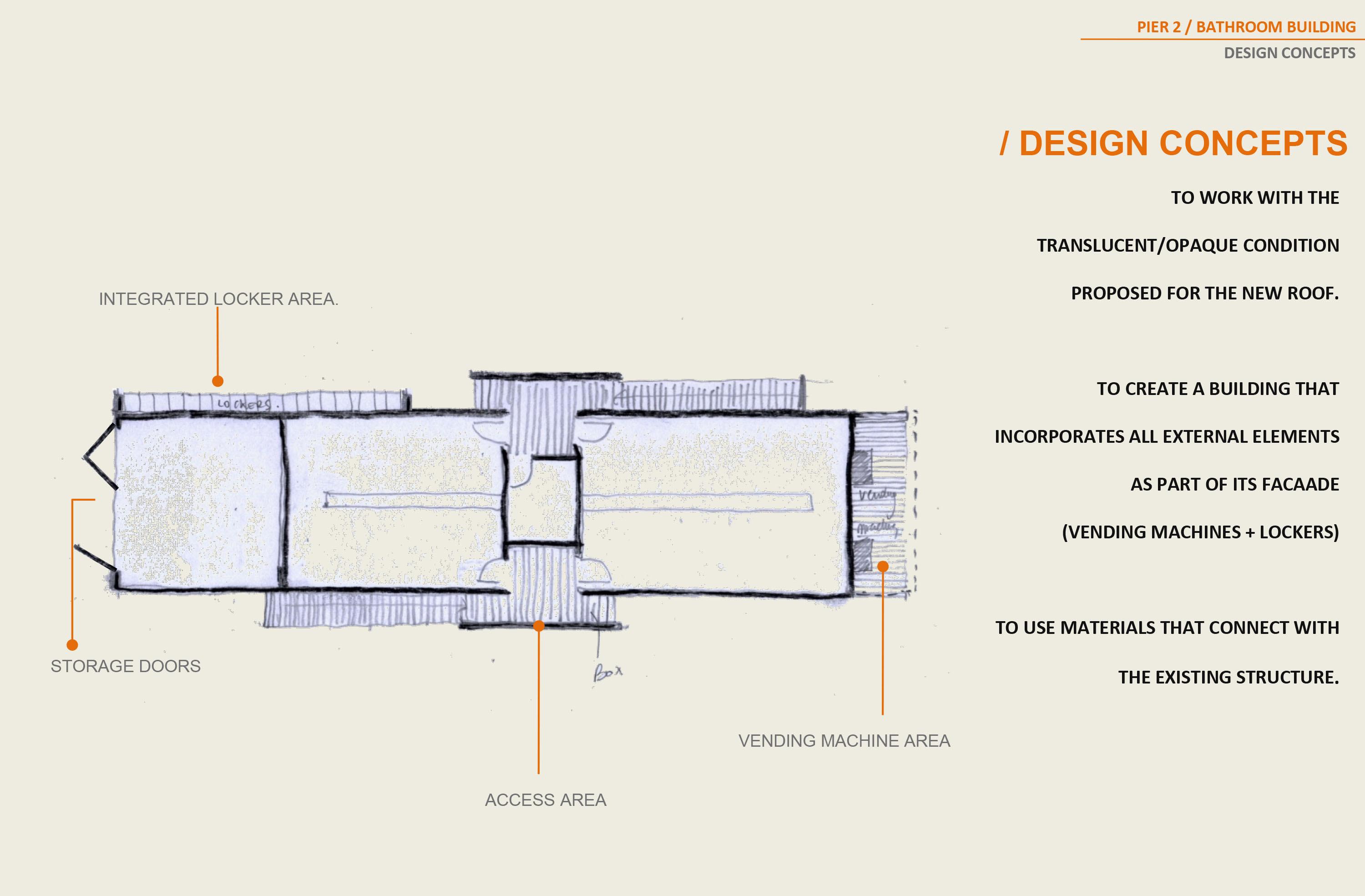

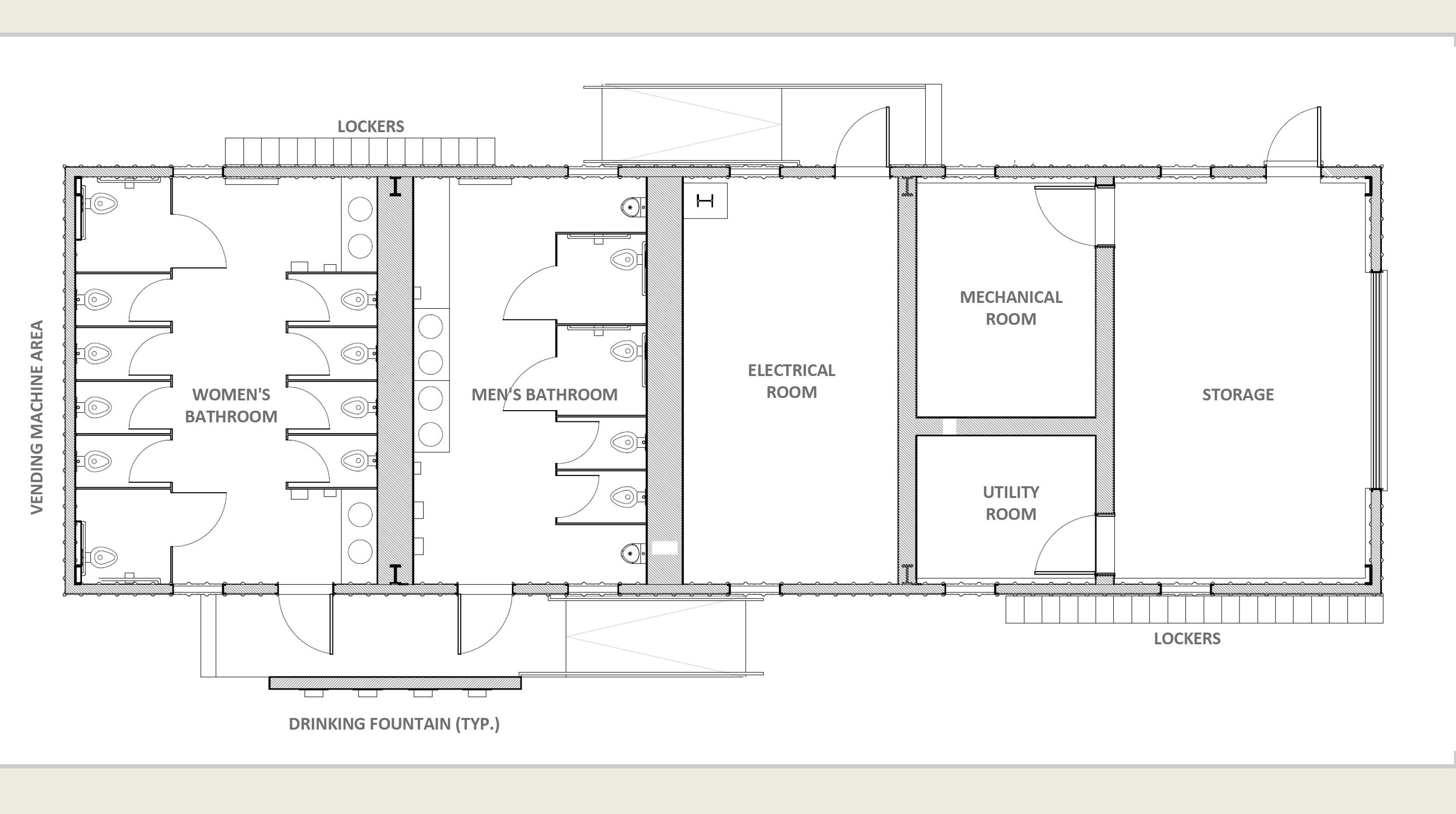

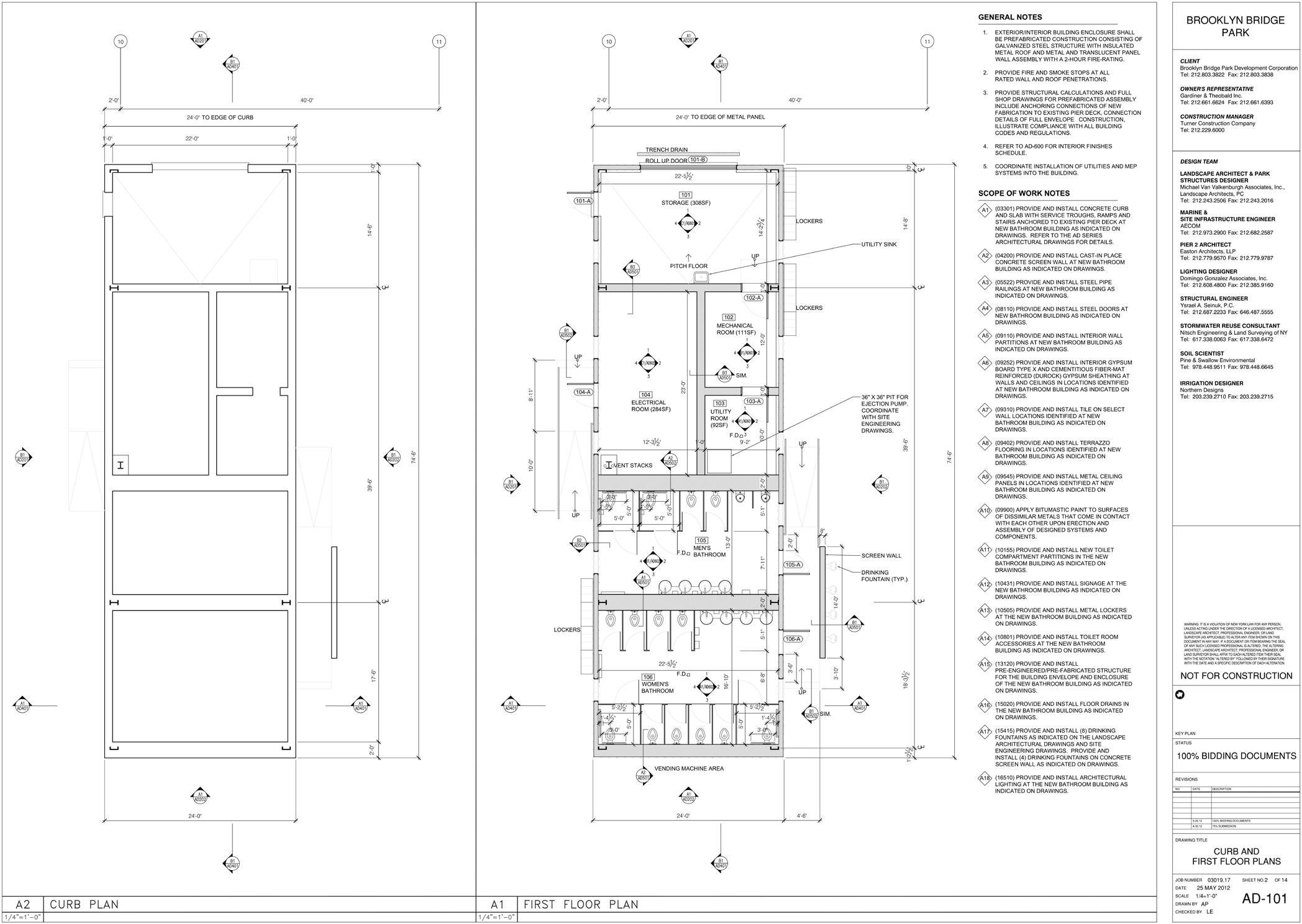

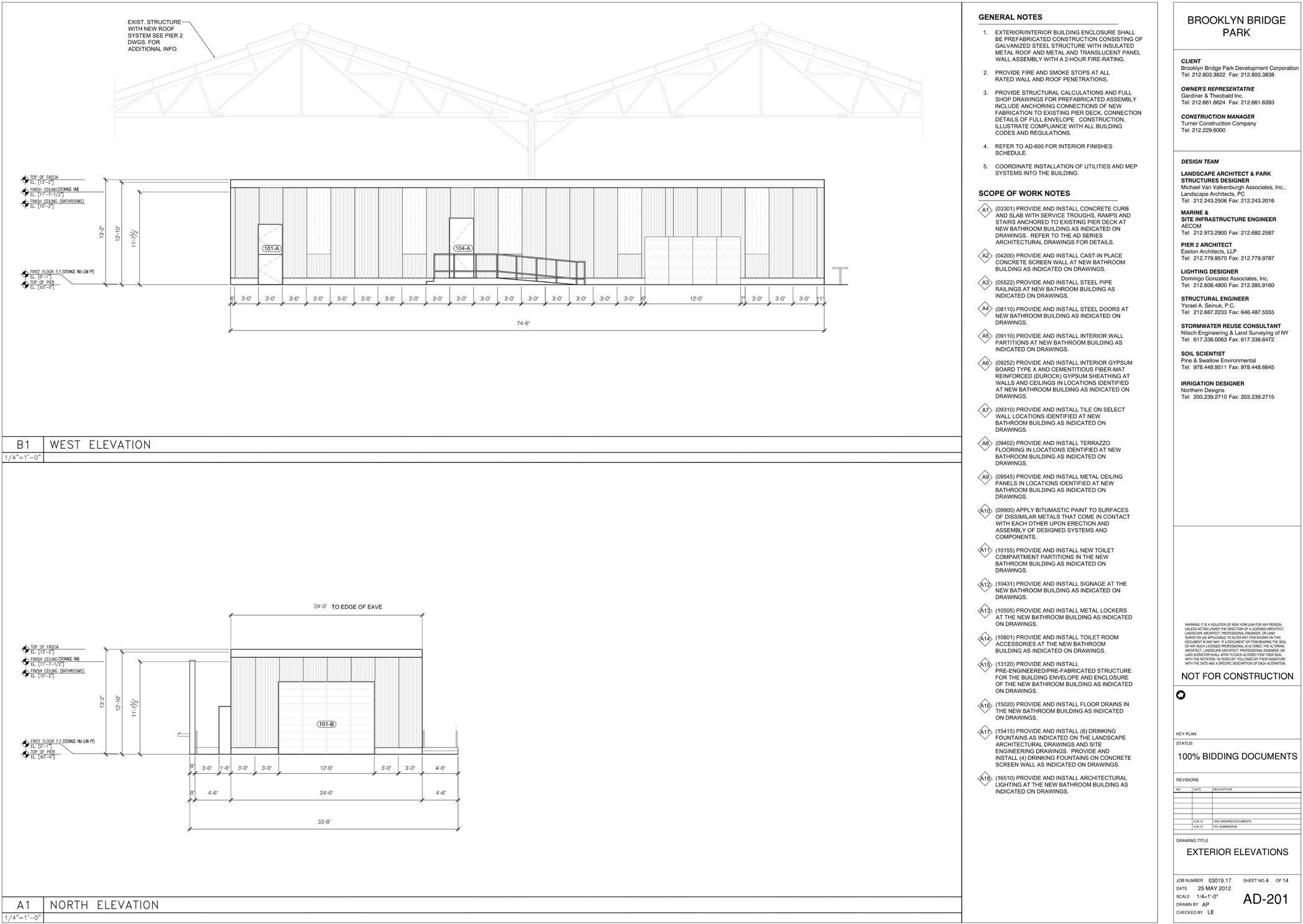

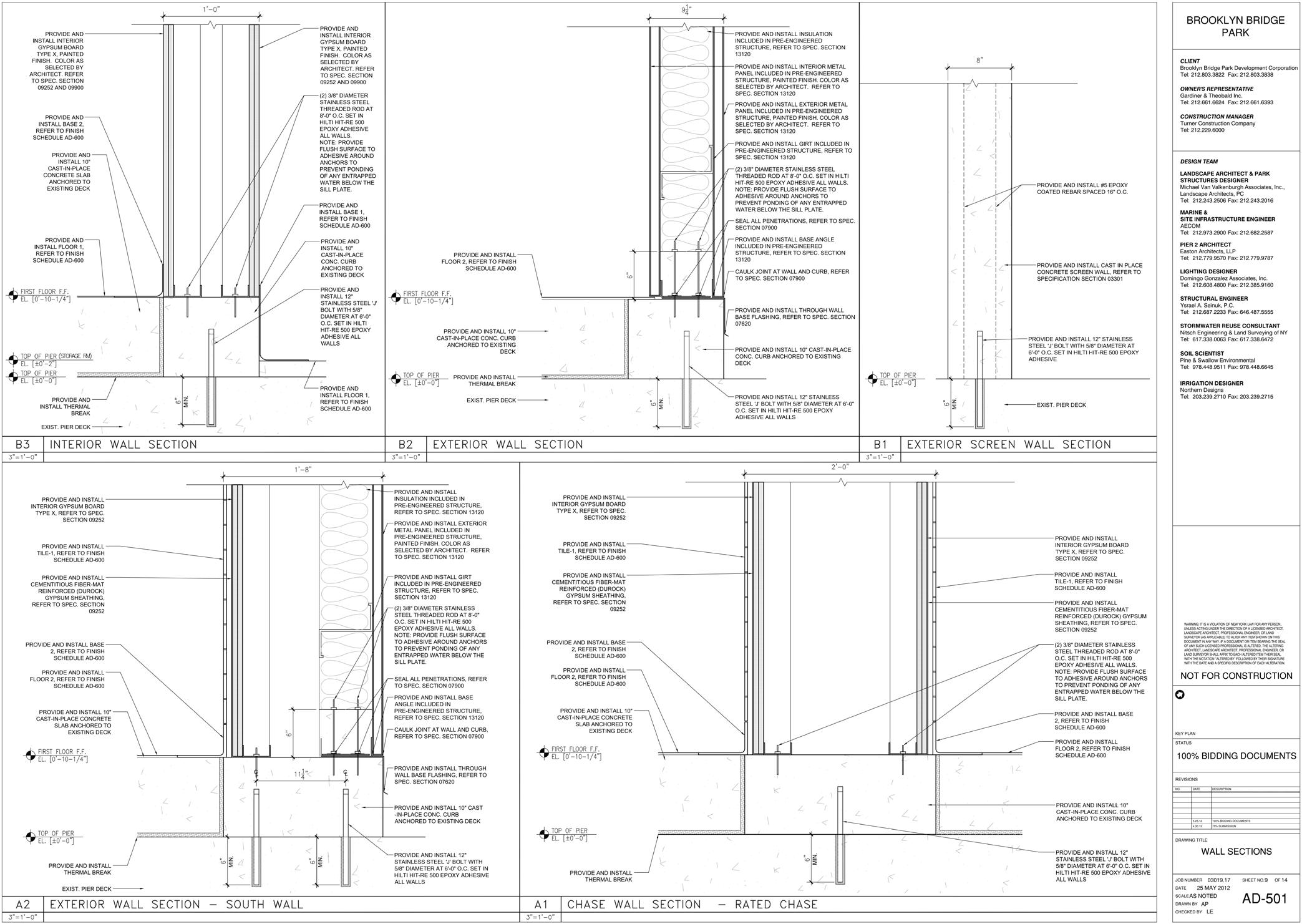

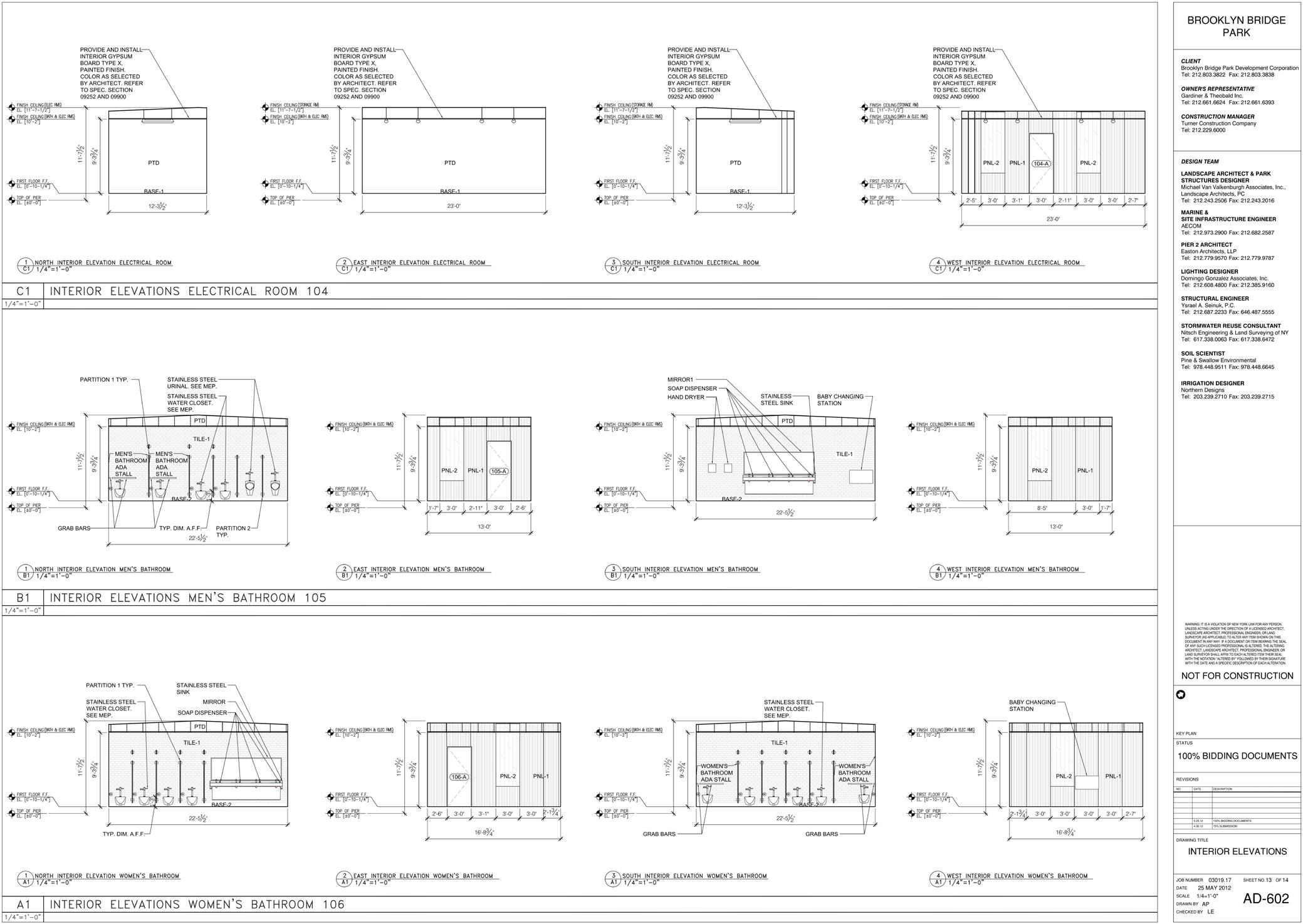

PROJECT: Brooklyn Bridge Park Pier 2

PROJECT LOCATION: Brooklyn Bridge Park Pier 2, Brooklyn, NY

Client: Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corporation

Landscape Architect & Park Structures

Designer: Michael Van Valkenburgh & Associates

Architect of Record (bathroom and enclosure): Easton Architects, LLP

-Lisa Easton, Partner

-Amy (Peterson) Van de Riet, Designer

-Lorena Perez, Designer

-Leo Krakowicki, Detailer

Structural Engineer: Ysrael A. Selnuk, P.C. Marine & Site Infrastructure Engineer: AECOM

MEP: Becht Engineering

Lighting Designer: Domingo Gonzalex Associates, Inc.

Sormwater Reuse Consultant: Nitsche Engineering & Land Surveying of NY

Soil Scientist: Pine & Swallow Envionmkental Irrigation Designer: Northern Designs

The first ferry landing at the land which is now Brooklyn Bridge Park’s Empire Fulton Ferry section was in 1642. By the beginning of the 19th century, the waterfront community was thriving with multiple docking points, the first steamboat ferry landing (which would eventually be linked with the Brooklyn City Railroad lines by the 1850s). Additional changes happened in the waterfront with the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge (completed in 1883), and the Manhattan Bridge (completed in 1909). The waterfront was effectively cut off from the nearby residential neighborhood, Brooklyn Heights, in the 1950s with the construction of the Brooklyn Height Promenade and Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

During the 1950s, many of the piers along the waterfront were altered to accommodate larger cargo ships. The use of the Brooklyn waterfront for cargo ship operations ended in 1983 by authorization of the Port Authority. Upon closing the shipping operations, Port Authority began the process to sell the piers for commercial use. Although the name has changed several times since 1984, the Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy ultimately guided the conversion from the industrial waterfront into recreational use. 1

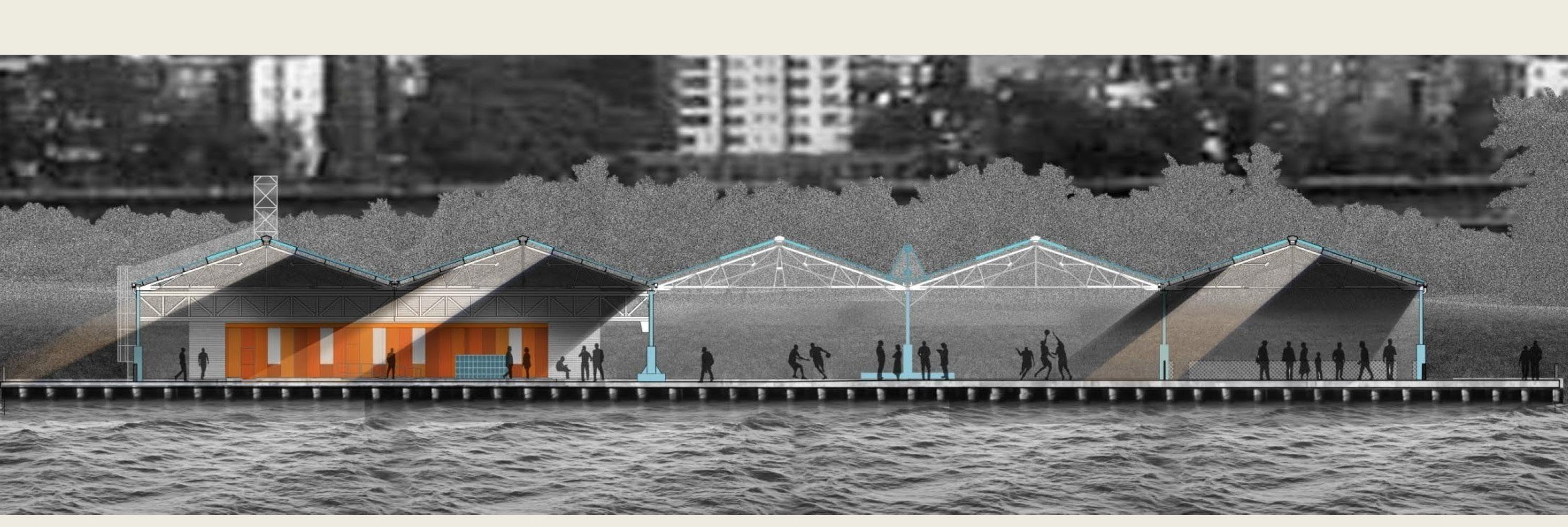

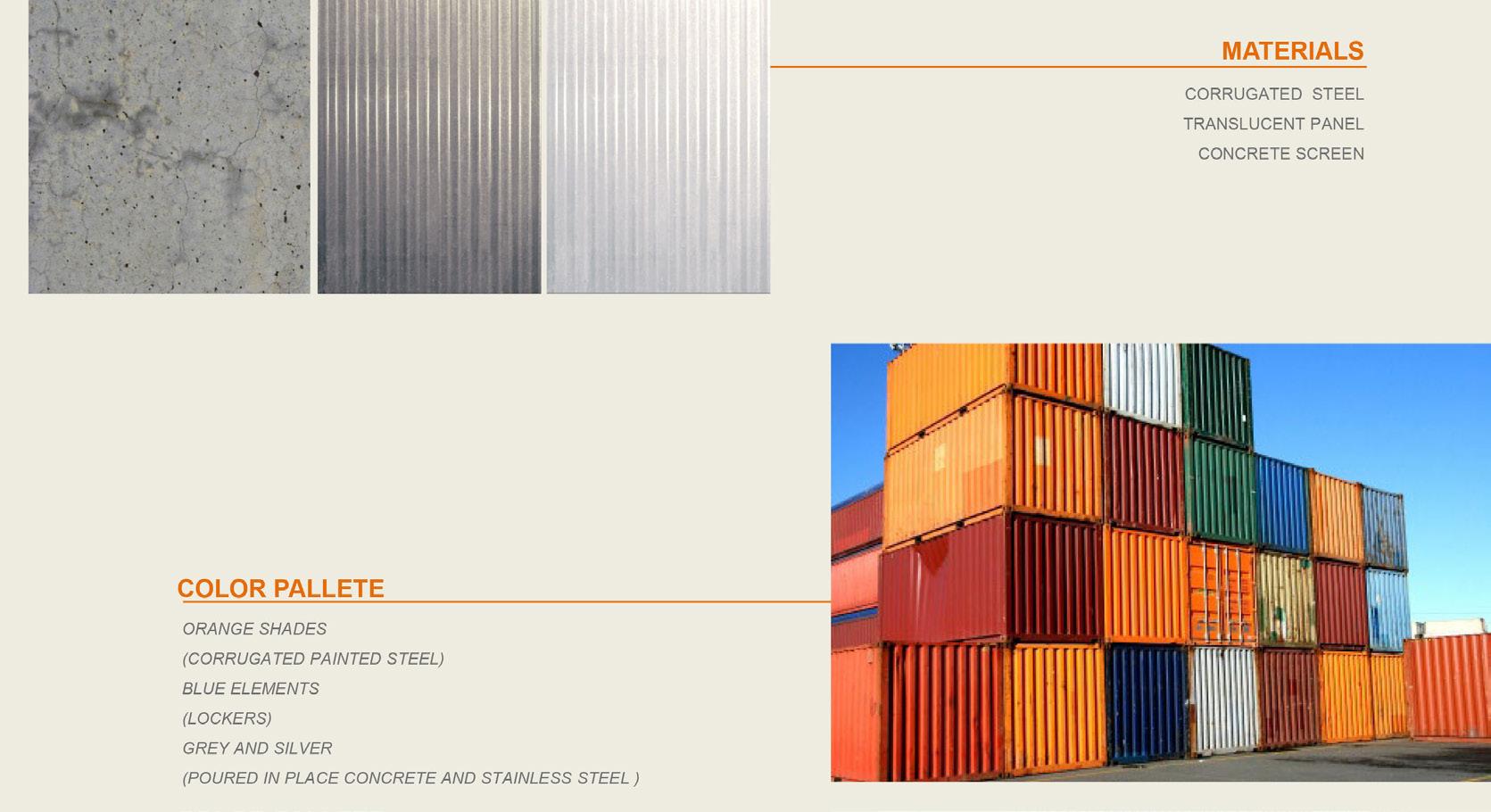

The Brooklyn Bridge Park is an 85 acre park along the East River which has revitalized 1.3 miles of Brooklyn’s post-industrial waterfront from Atlantic Avenue to the south to Jay Street north of the Manhattan Bridge designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh & Associates. Easton Architects was the Architect of Record for the Adaptive Reuse of the circa 1958 Pier 2. The pier, once used for lumber storage, has been reused for active recreation and features amenities ranging from a hockey rink, outdoor turf field to a variety of sport courts. Pier 2 is the only pier of the six recycled for park use that retains a significant amount of its original structure.

New York AIA Chapter Award of Merit for Design Excellence

1Information from this section was derived from the Brooklyn Bridge Park website https://www.brooklynbridgepark.org/about/history/

Historic photos of Brooklyn waterfront. Top photo shows Pier 2 (middle pier) being actively used for shipping. The photo is from the Port Authority archive from circa 1960. The bottom photo shows the warehouses on Pier 2 constructed in circa 1958. The photo is courtesy of the Brooklyn Historical Society, John D. Morrell photograph collection. The cladding on the structure was removed prior to the start of the project. The first survey of the site had only the existing structure to preserve.

Site location indicated with rendered blue roof. Pier 2 is the second pier south from the Brooklyn Bridge.

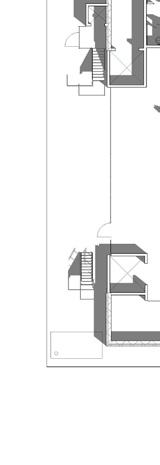

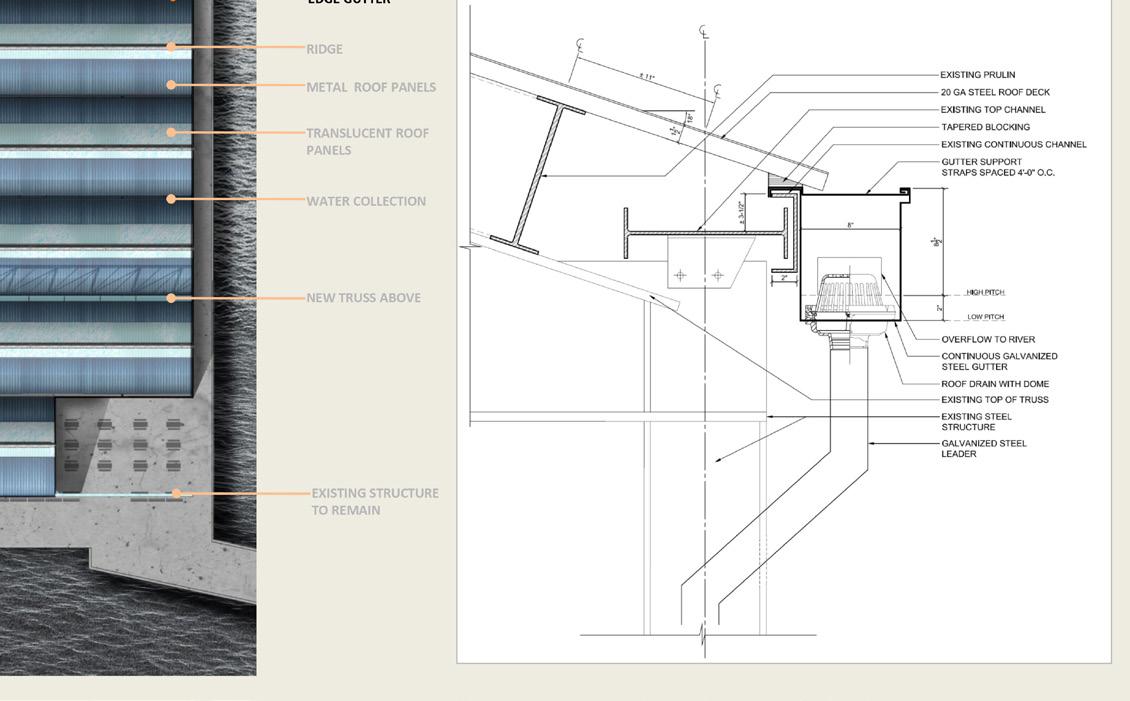

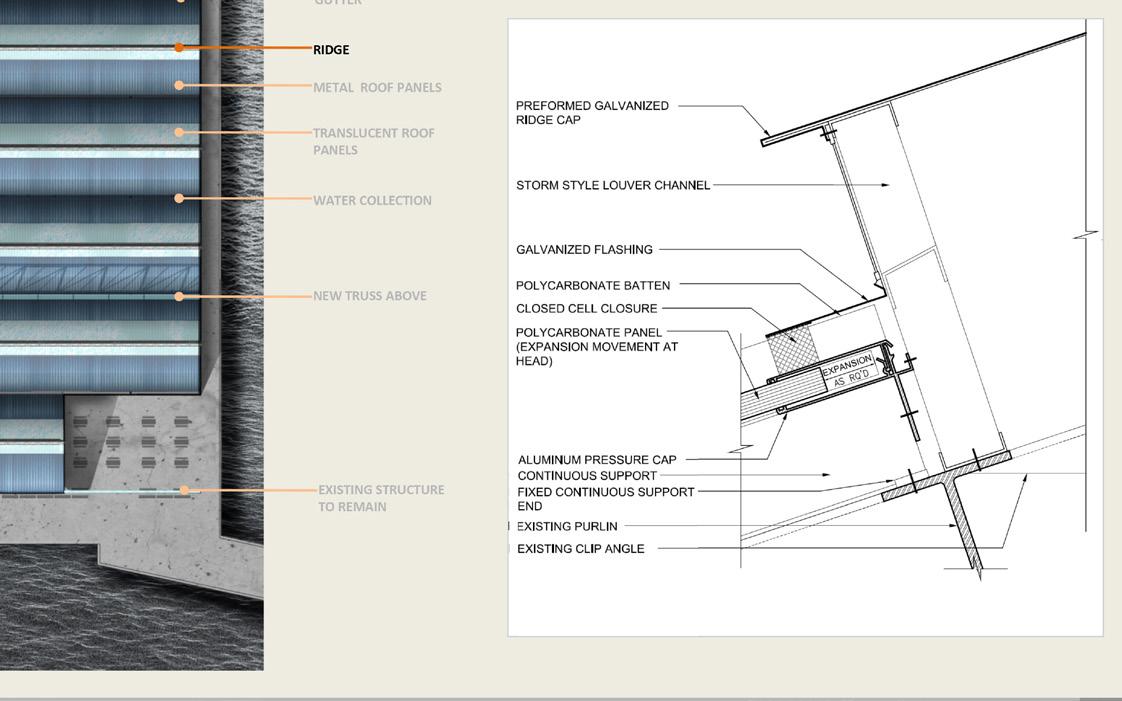

Rendering of existing structural system, and proposed new roofing.

Schematic drawings of proposed polycarbonate roof system on existing structure.

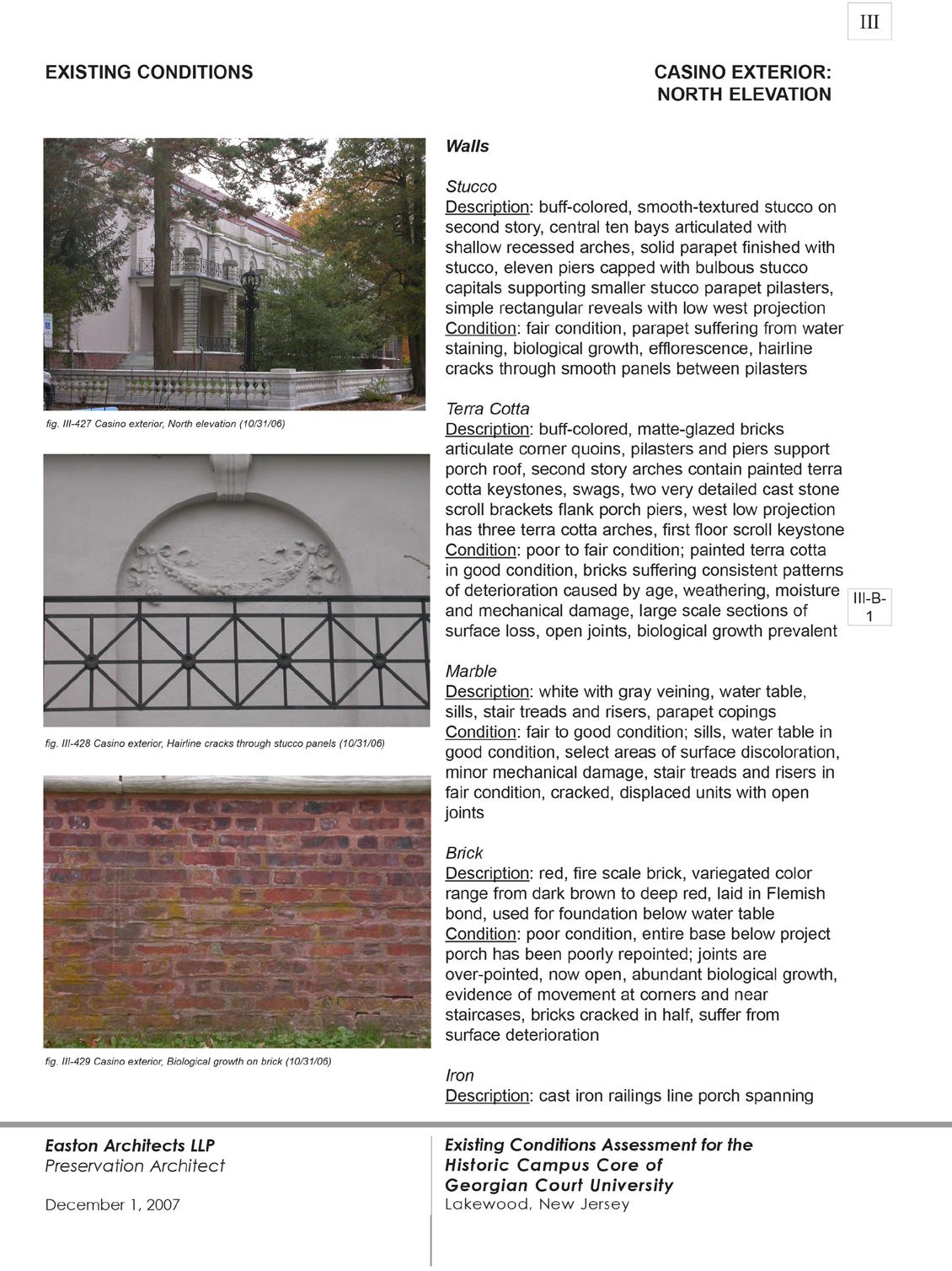

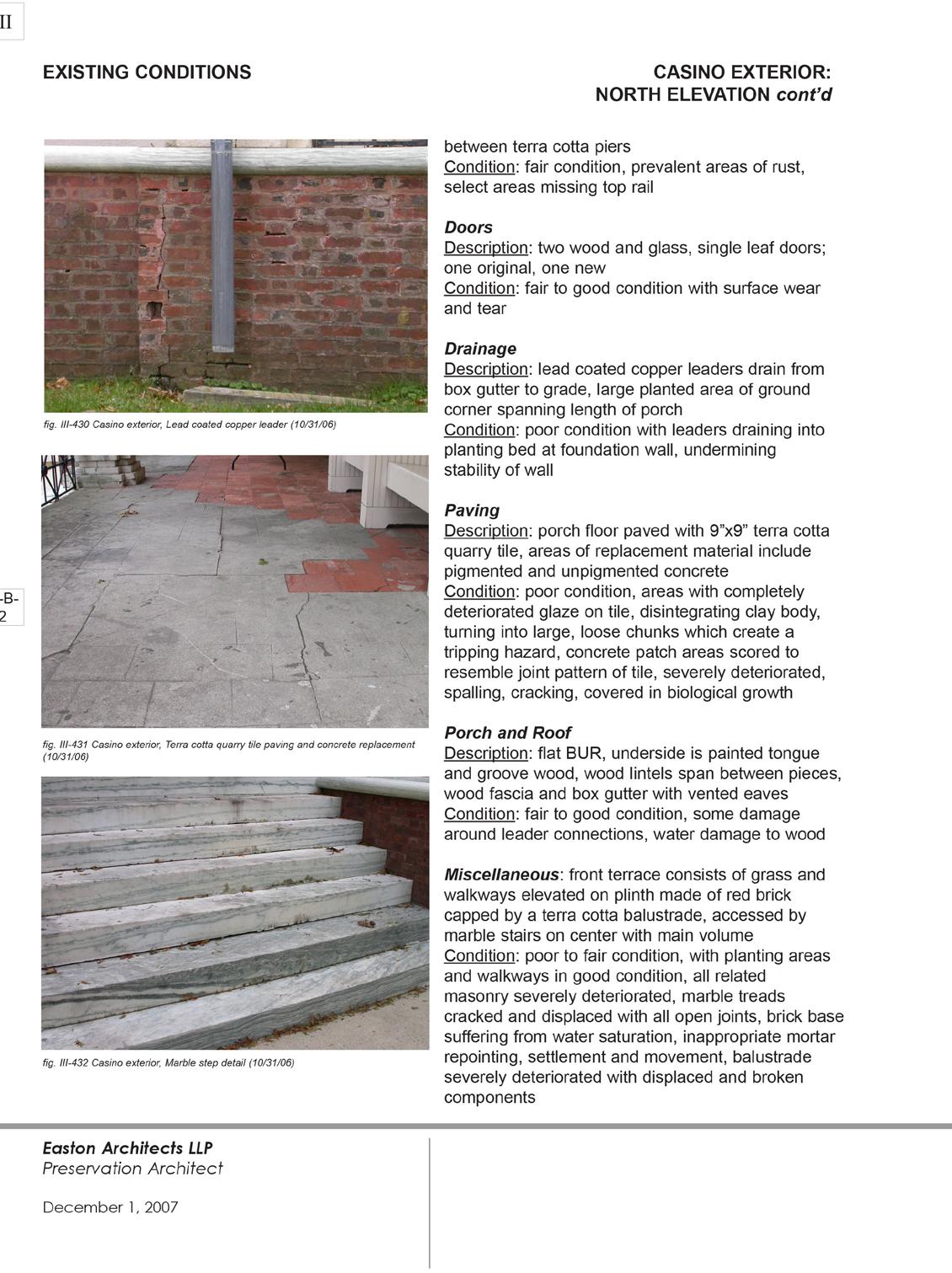

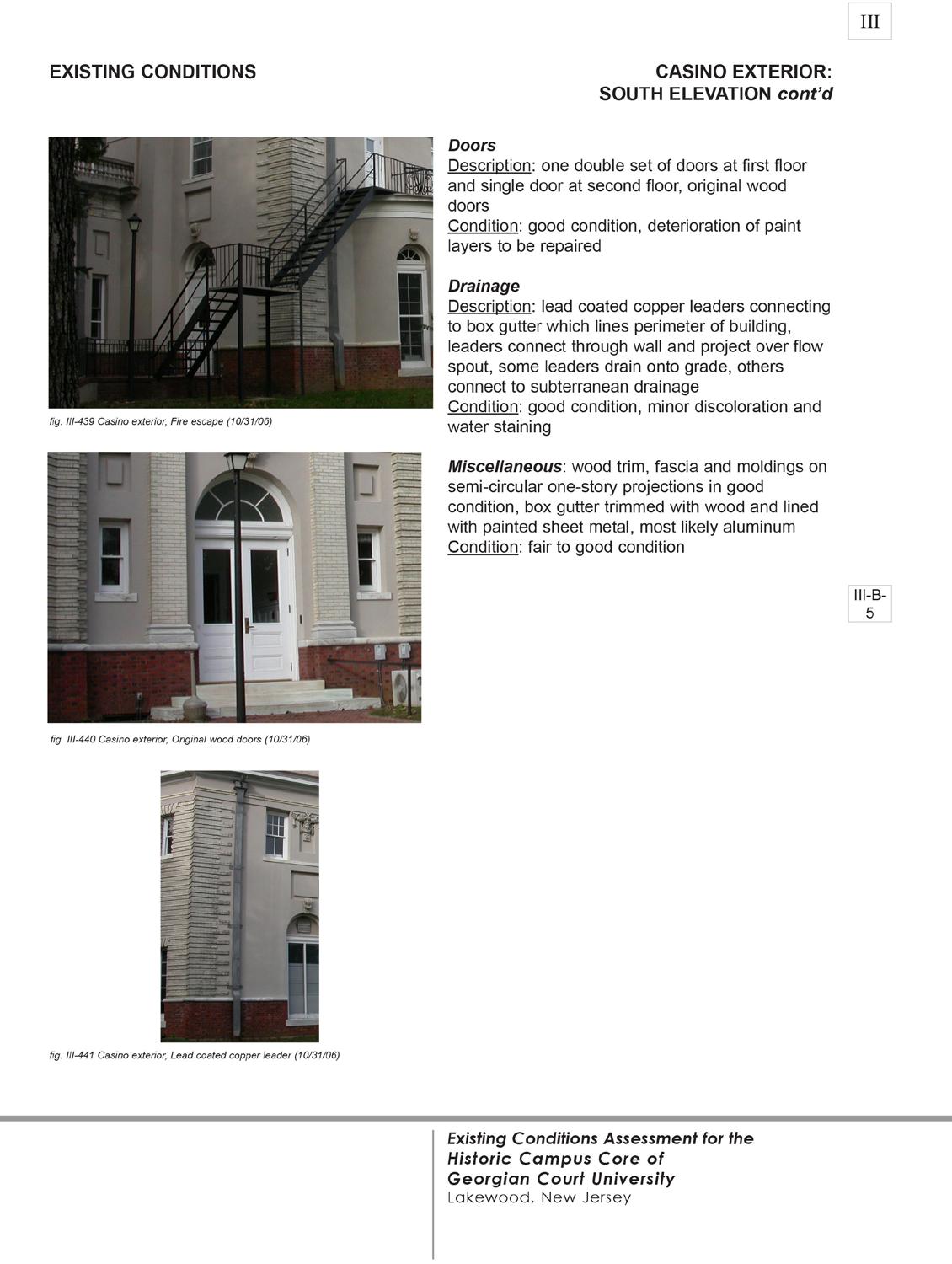

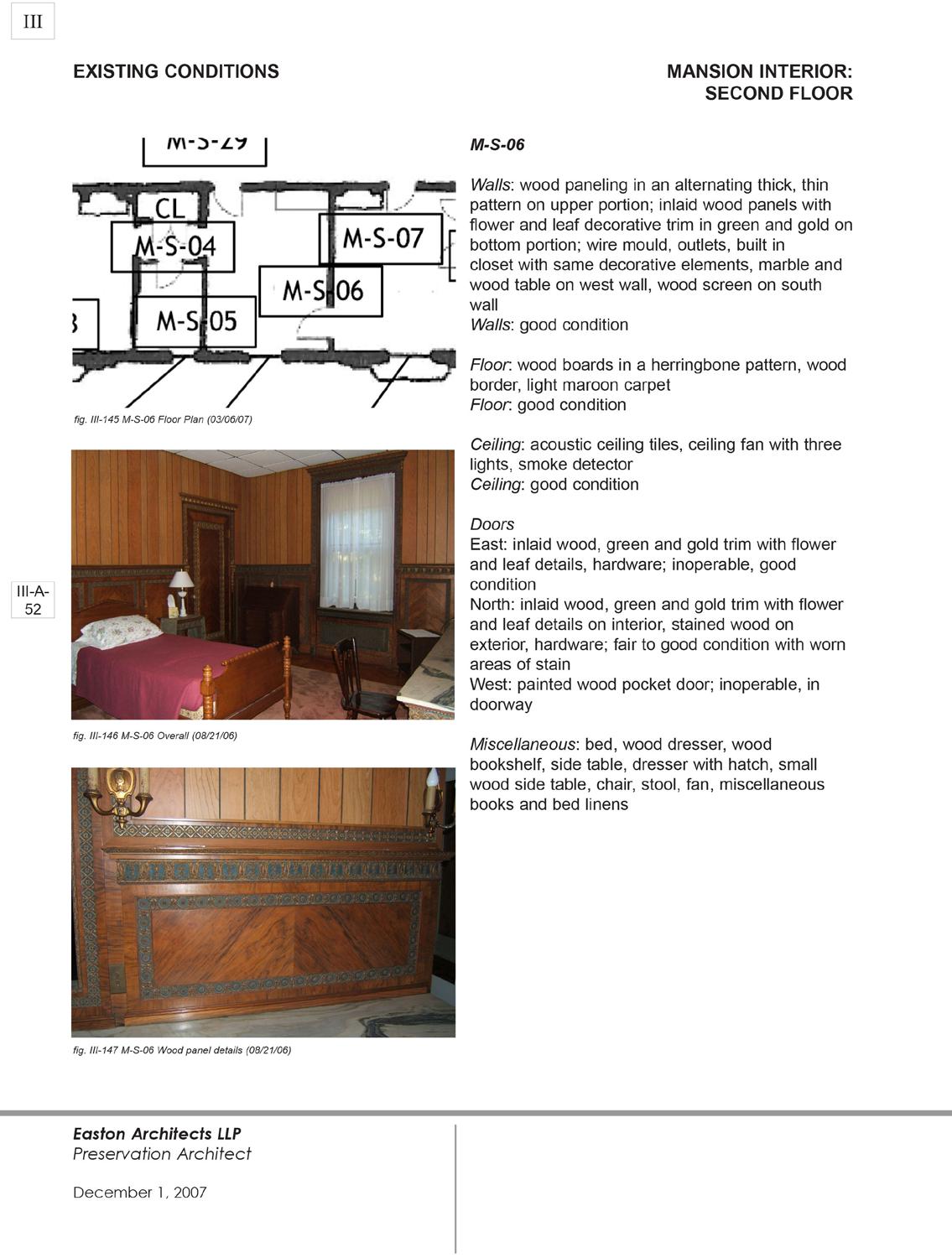

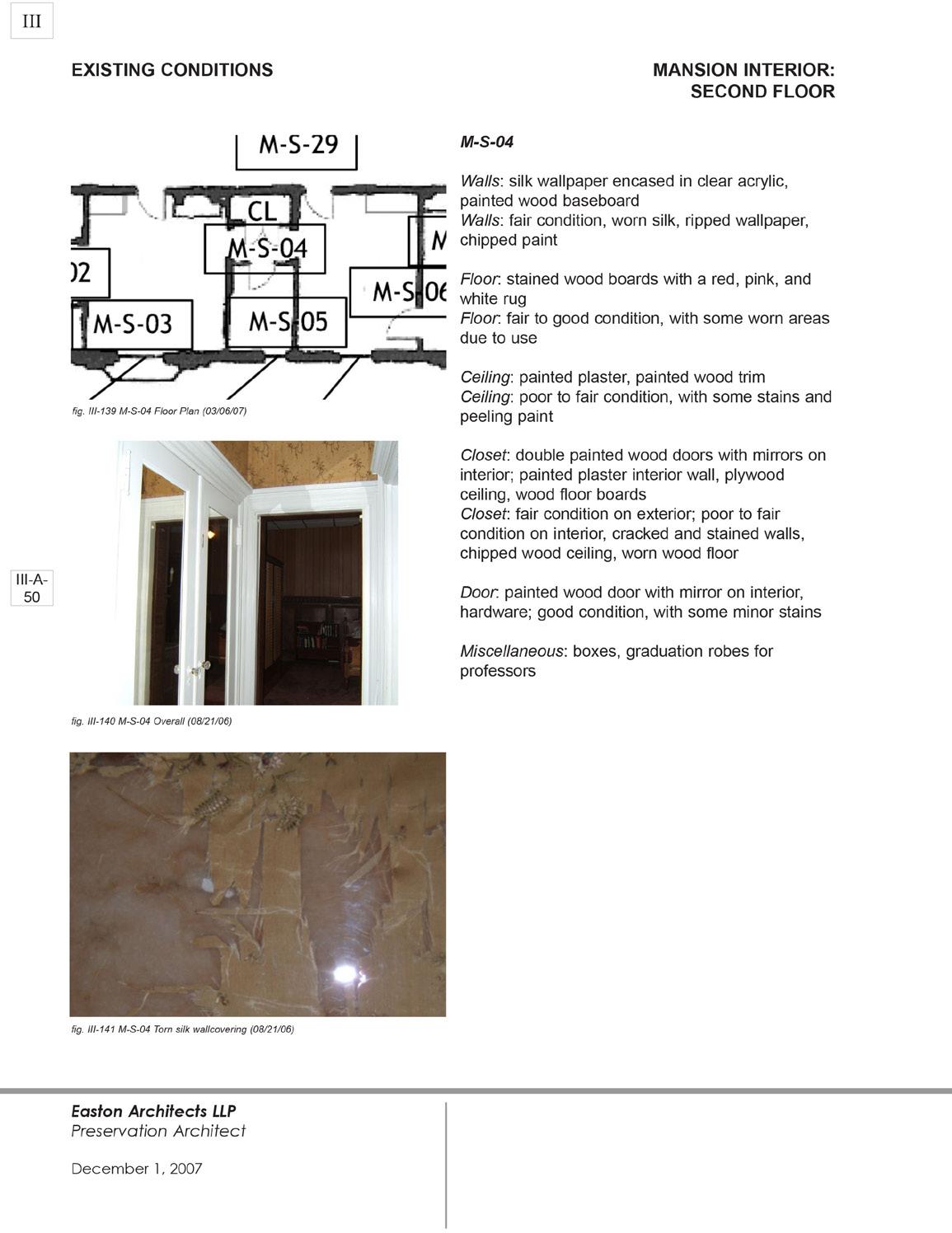

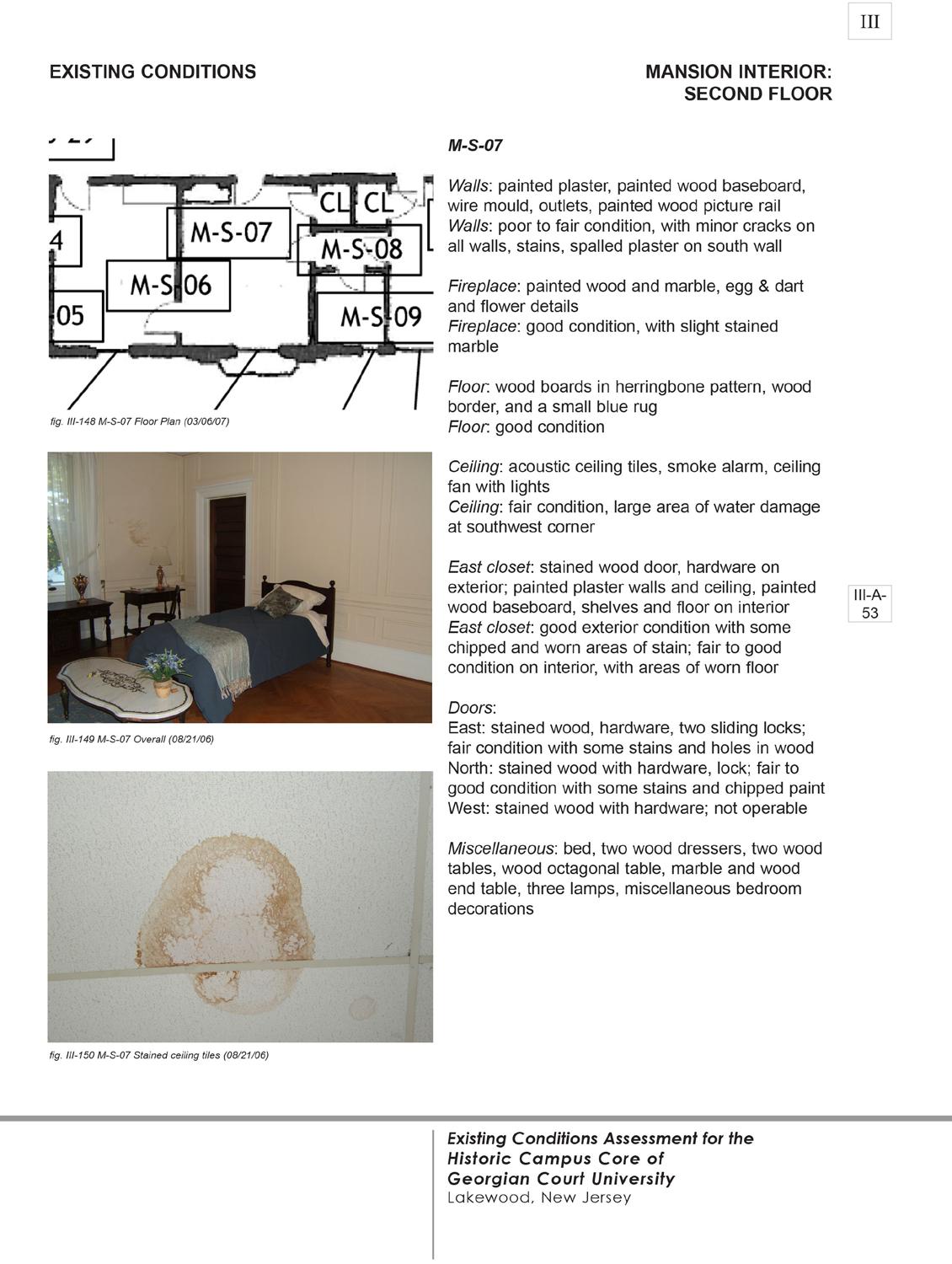

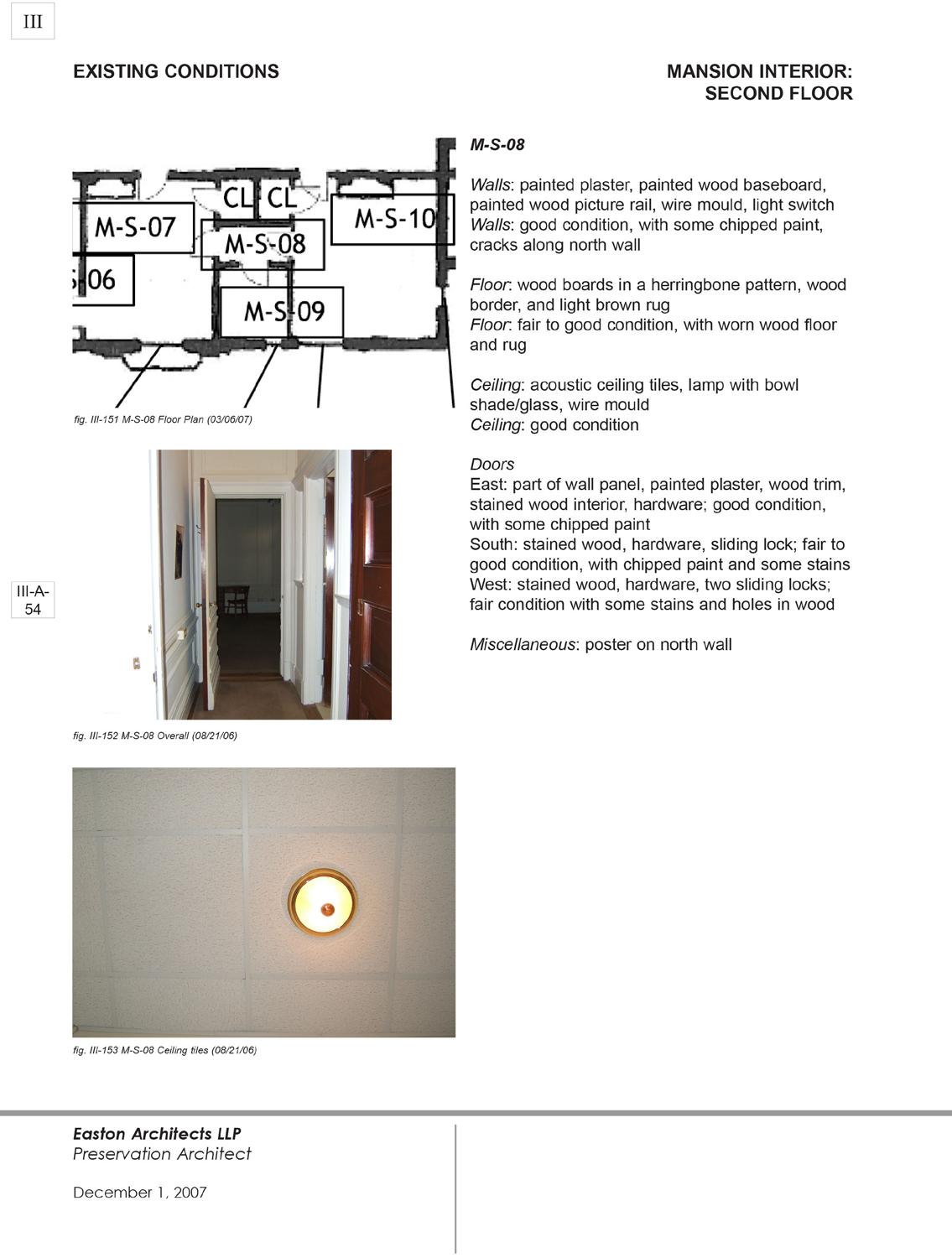

PROJECT: Existing Conditions Assessment for the Historic Campus Core of Georgian Court University

PROJECT LOCATION: Lakewood, New Jersey

PROJECT TEAM:

Client: Georgian Court University

Preservation Architect: Easton Architects, LLP

-Lisa Easton, Partner

-Amy (Peterson) Van de Riet, Designer -Tellina Lui, Intern

Structural Engineer: Robert Silman Associates Conservator: Jablonski Berkowitz Conservation Inc.

MEP: Becht Engineering

Cultural Landscapes specialists: Elmore Design Collaborative

Cost Estimator: G2 Project Planning

Stained Glass Consultant: Julie Sloan

PROJECT SCOPE:

Our team understands the historic, cultural, social and architectural significance of the Georgian Court Campus, and supports the development of a holistic restoration and preservation approach that comprises the Existing Conditions Assessment for the complex and its landscape. The University understands the importance of initiating an effort to investigate the conditions of all seven structures and four gardens; after more than 100 years and many repair campaigns.

The project’s major objective was to prepare an Existing Conditions Assessment to analyze all components of the buildings’ envelopes and infrastructure, provide recommendations for the most appropriate and effective watertight solution for the exteriors while retaining and maintaining as much of the original historic fabric as possible, develop a restoration methodology for interior finishes and character-defining features, and develop a landscape conservation plan that will appropriately balance history, use and maintainability while framing a vision for the future of the historic campus core. It is our intention that the original character-defining features of the complex and its landscaping be preserved when possible and rehabilitated or restored when preservation is not possible. The Existing Conditions Assessment will be used to assist in making informed capital expenditures and act as a road map for future restoration and rehabilitation work on the buildings and site. All work done will reflect the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties and the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes.

The Comprehensive Existing Conditions Assessment has been separated into 3 components:

PART 1) Existing Conditions Analysis: The team identified all conditions, evaluated materials and infrastructure. All information is contained in Section III Existing Conditions Analysis.

PART 2)

Detailed cost estimates have been prepared for all aspects of the ECA, complete with a phasing strategy.

A long-term capital funding program has been outlined to allow work to proceed accordingly along a multi-phased path.

Historic Sites Management Grant from the New Jersey Historic Trust

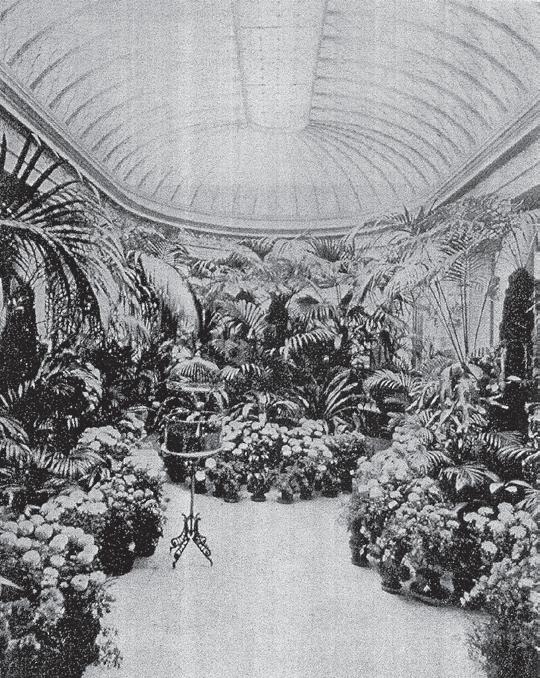

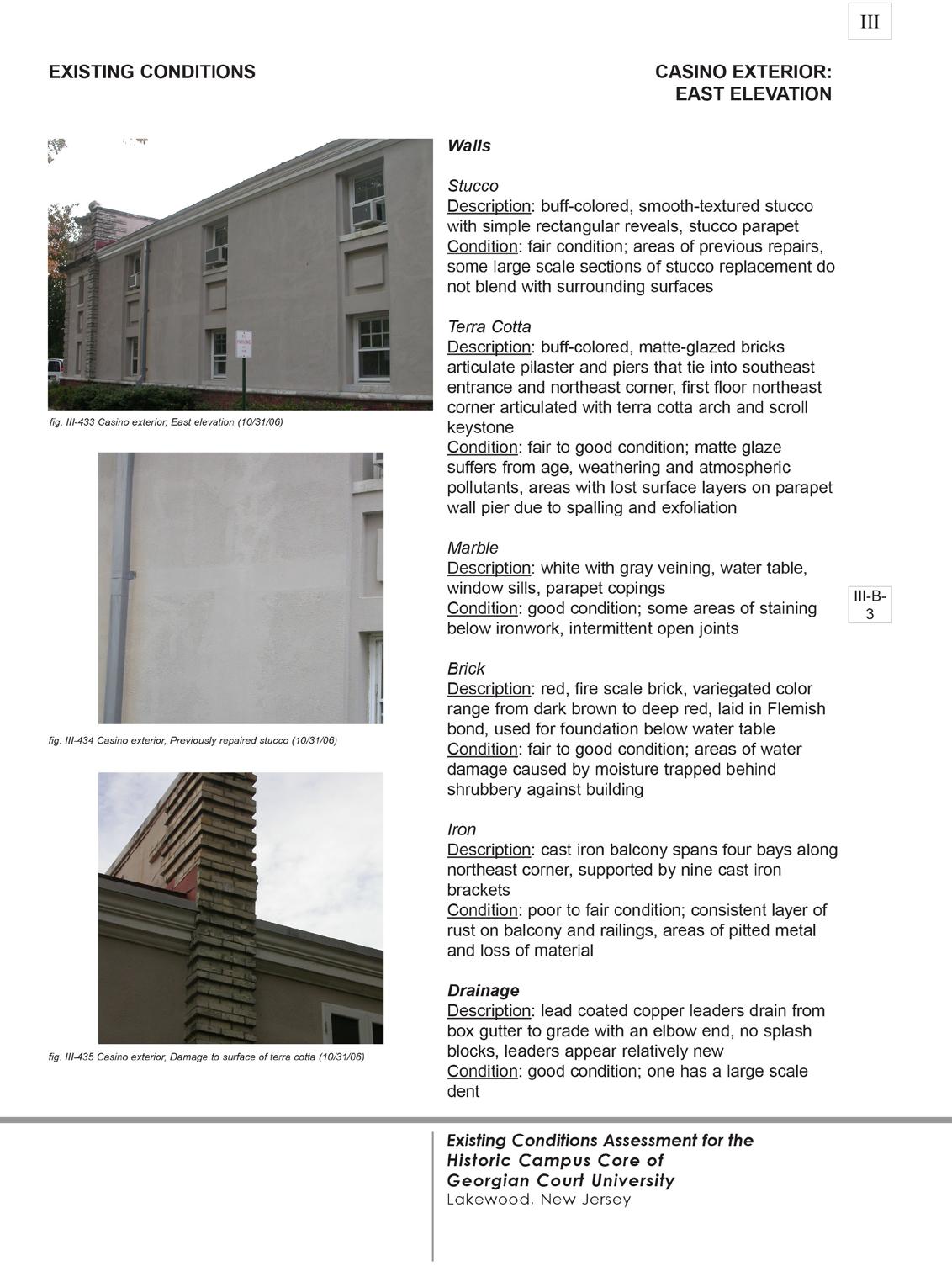

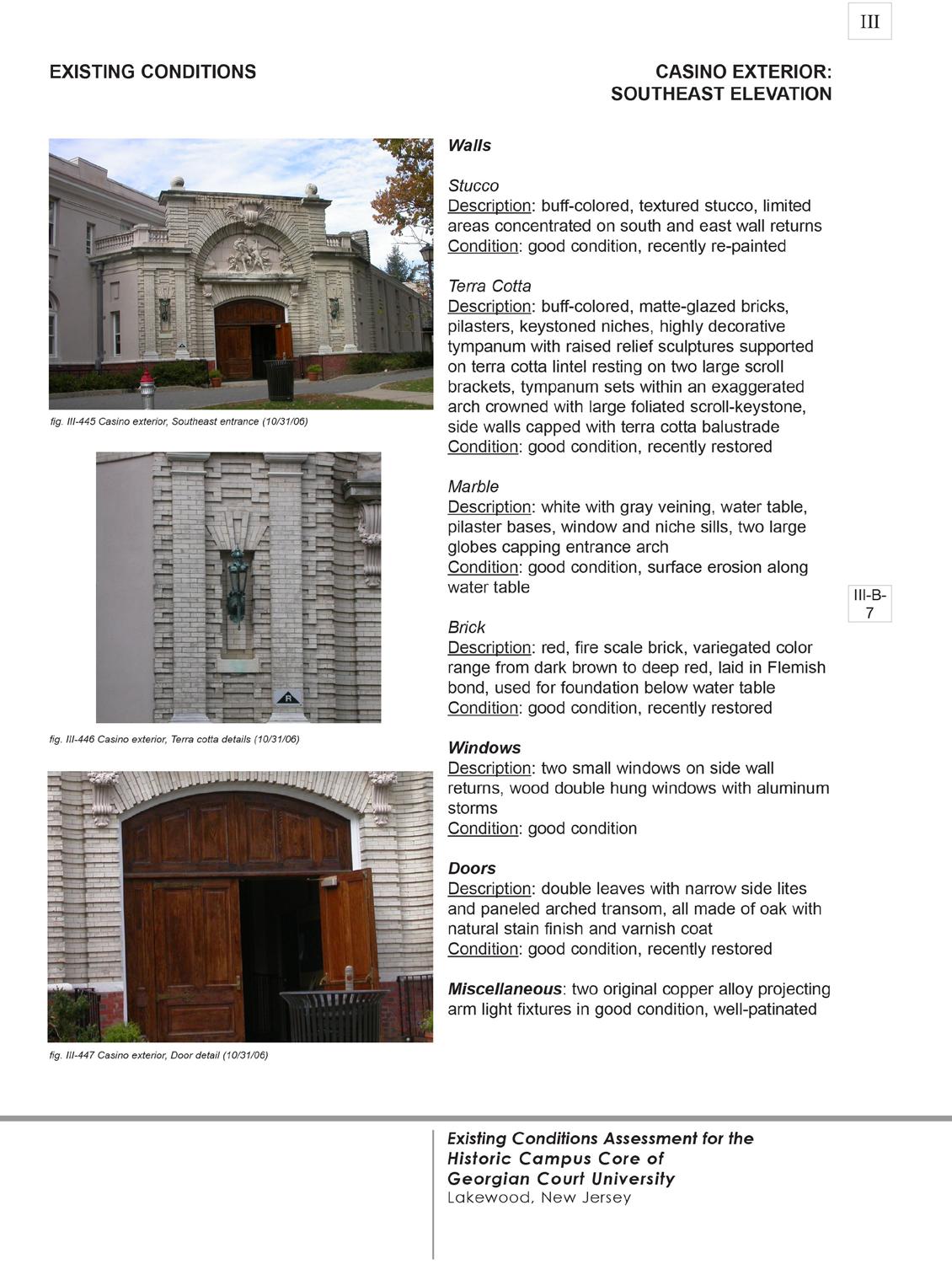

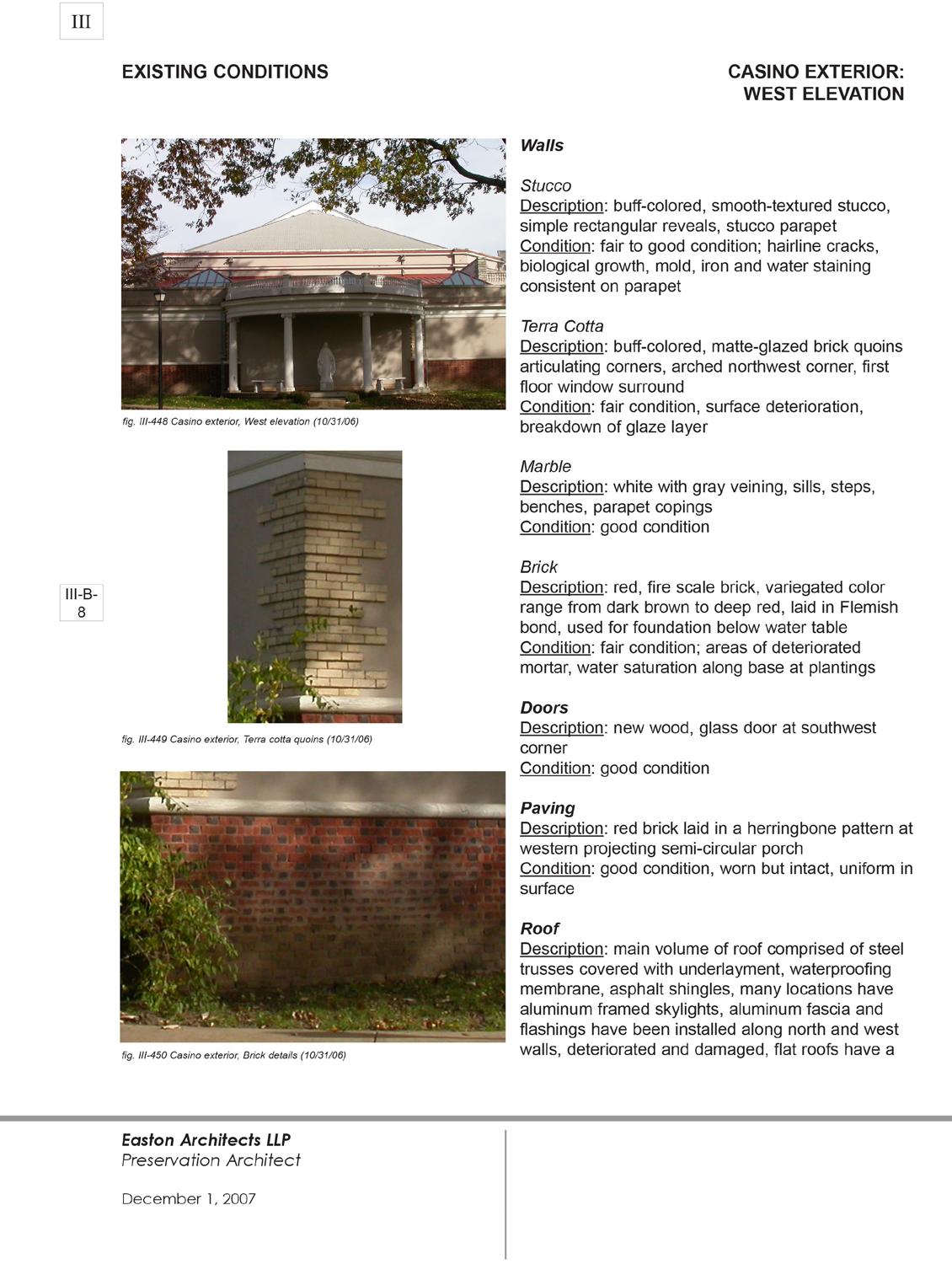

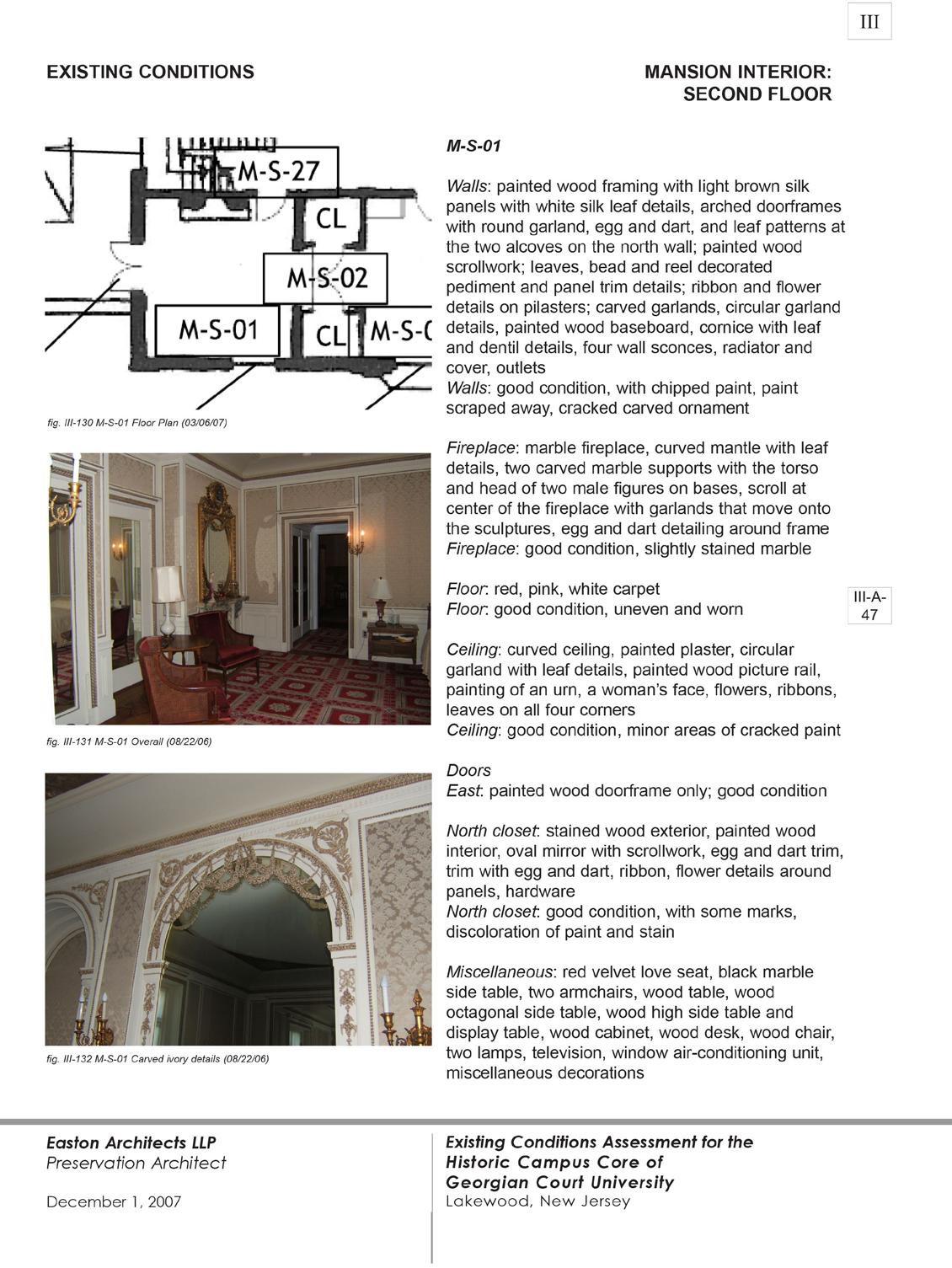

Georgian Court University, located along the shores of Lake Carasaljo in Lakewood, New Jersey, was once the estate of George Jay Gould, the eldest son of Helen Day Miller and Jay Gould, financier and railroad magnate. The core of the site consists of a collection of seven historic buildings: Mansion, Casino, Raymond Hall, Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Kingscote, Hamilton Hall and Lake House and four historic gardens: Formal Garden, Sunken Garden, Italian Garden and Japanese Garden. The Gould era portion, designed in the style of an English estate of the Georgian period, was known as Georgian Court and was designed by renowned New York architect Bruce Price between 1896 and 1898.

For the design, George shared his thoughts of the great estates in Scotland and England with Price. Price also drew upon his extensive experience of designing country homes for the wealthy. The two men soon agreed upon the style of an English estate of the Georgian period, which would provide an ordered collection of objects within the wooded terrain. The estate’s name, Georgian Court, was derived from the architectural style of the buildings.

Bruce Price designed the landscape to maintain a harmony between landscape and built form. As Price notes in an interview when questioned about designing a country house:

“Not going in opposition to nature. It is too frequently the case that an architect will insist that his building is the chief thing in a landscape; that one must look at it whether he wants to or not; that everything must make way for it; that the work of man must surpass in visibleness the work of nature. As a matter of fact, a house is but part of a scene, and the more complete the more complete the scene, the more naturally the house is adapted to it surroundings, the better it fits into the landscape, the better the result. It is not a matter of choice; but a matter of actuality readily determined and easy to see in advance if the surroundings are properly studied. It is so easy to invent; and so extremely difficult to design.”1

Today the site is home to Georgian Court University and the campus was listed on both the State and National Registers of Historic Places and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1978.

1Barr Ferree, “A Talk with Bruce Price.” Great American Architect Series, no. 5, Architectural Record (June 1899): 66.

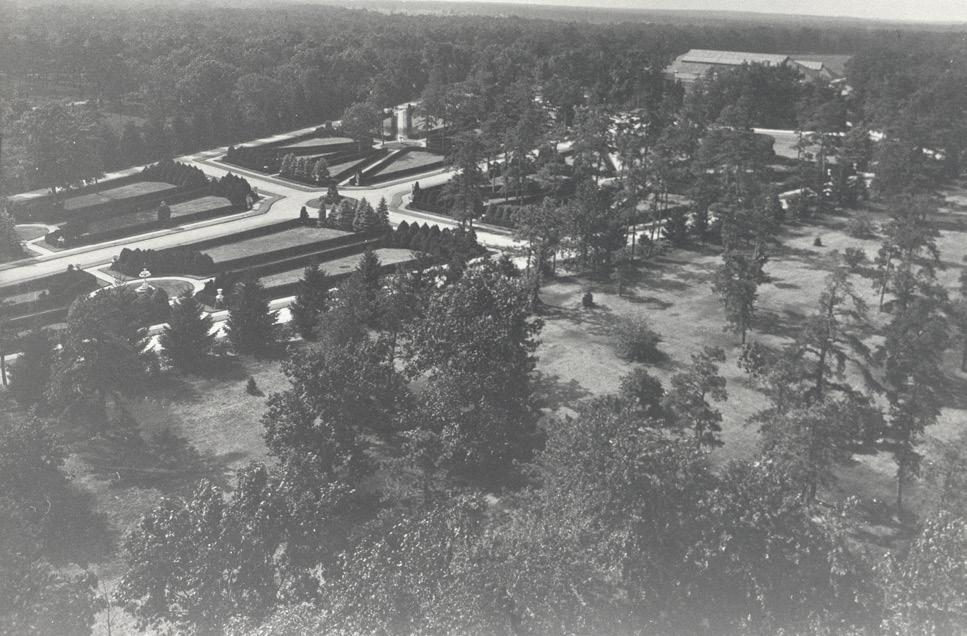

Aerial Photo of Georgian Court (ca. 1900s) Courtesy of Georgian Court Archive

Mansion Great Hall (ca. 1900s) Courtesy of Georgian Court Archive

Conservatory (ca. 1890s) Architectural Record, June 1899. 106.

Casino interior (ca. 1905) Courtesy of Moss Archives, Pach photo. Georgian Court: An Estate of the Gilded Age. By M. Christina Geis. Philadelphia: The Art Alliance Press, 1991. 59.

Aerial Photo of Georgian Court (ca. 1900s) Courtesy of Georgian Court Archive

Mansion Great Hall (ca. 1900s) Courtesy of Georgian Court Archive

Conservatory (ca. 1890s) Architectural Record, June 1899. 106.

Casino interior (ca. 1905) Courtesy of Moss Archives, Pach photo. Georgian Court: An Estate of the Gilded Age. By M. Christina Geis. Philadelphia: The Art Alliance Press, 1991. 59.

PROJECT: Replication of Historic Grotesques

PROJECT LOCATION: Dyche Hall, University of Kansas Campus

Client: University of Kansas

Architects: Amy Van de Riet & Keith Van de Riet

Stone Carvers: Laura Ramberg and Karl Ramberg

The history of the construction of Dyche Hall coincides with the rise of the study of natural history. Dr. Francis Huntington Snow, for whom Snow Hall at KU is named after, started and collected for the Cabinet of Natural History from 1866 to 1889. Other contributors were Lewis Lindsay Dyche who secured the building for the Cabinet and E. Raymond Hall who made the Natural History Museum thrive. Snow Hall was erected in 1887 which became the Museum Building and became the home to the growing collection.

Undeniably integral to the creation of Dyche Hall, Lewis Lindsay Dyche began his association with KU in 1877 first as a student, then in 1888 as a professor. Photos of Dyche from his time at KU show him as an explorer, taxidermist and innovator of new exhibition techniques as seen in the dramatic Panorama of North American Animals originally shown at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (currently still a permanent exhibit at Dyche Hall). His ability to promote the public understanding and appreciation of natural history was integral in the formation of Dyche Hall.

Quoted from the architects of Dyche Hall (Siemen & Roots) in the Lawrence Daily Journal World, January 1, 1902: “The plan as we present it is substantially Professor Dyche’s and the arrangement proposed, though unique in our experience, entirely meets with our approval….We have sought to design an exterior capable of being executed in some of the excellent native materials. Stone for the exterior seemed to be the most appropriate possible material…. We have thought the Romanesque style of southern France would be the most available…. Indeed the entrance in both of our designs is after the lines of St. Trophime at Arles….[The] entrance it is our desire to carve beautifully with all manner of birds, beasts and reptiles. We think the exterior should represent the uses of the building in its detail, and in a general sense that its architectural character should be sufficiently dignified and beautiful to fittingly express the dignity of the institution. We wish to build a building which will be unique in itself, yet not inharmonious with the other buildings, and which will be a beautiful crown to this unusual site, and a source of pride to the citizens of the state always.”1

This project implemented a novel integration of technology within preservation education, where historic models of collaboration between architect and sculptor were revisited with modern digital technologies. The process involved academic and practical aspects of preservation through replication of (8) grotesque statues adorning an historic façade on the University of Kansas (KU) campus. Architecture students pursuing an historic preservation certificate at KU learned photogrammetry and 3D modeling software to digitally document and repair severely eroded stone carvings from the original construction of Dyche Hall, also known as the Natural History Museum. The collaborative workflow involved an interdisciplinary team of architects and artists, as well as students in architecture, sculpture and museum studies. The “apprentices” of each discipline were introduced to new technologies that facilitated the process of collaboration and final execution of the carved Cottonwood limestone grotesques, while at the same time exposing these students to a variety of fieldwork utilizing these technologies that can be applied to a variety of project typologies.

1 Carol Shankel, Dyche Hall: University of Kansas Natural History Museum 1903-2003. (Lawrence, Kansas: Historic Mount Oread Fund, 2003) 14.

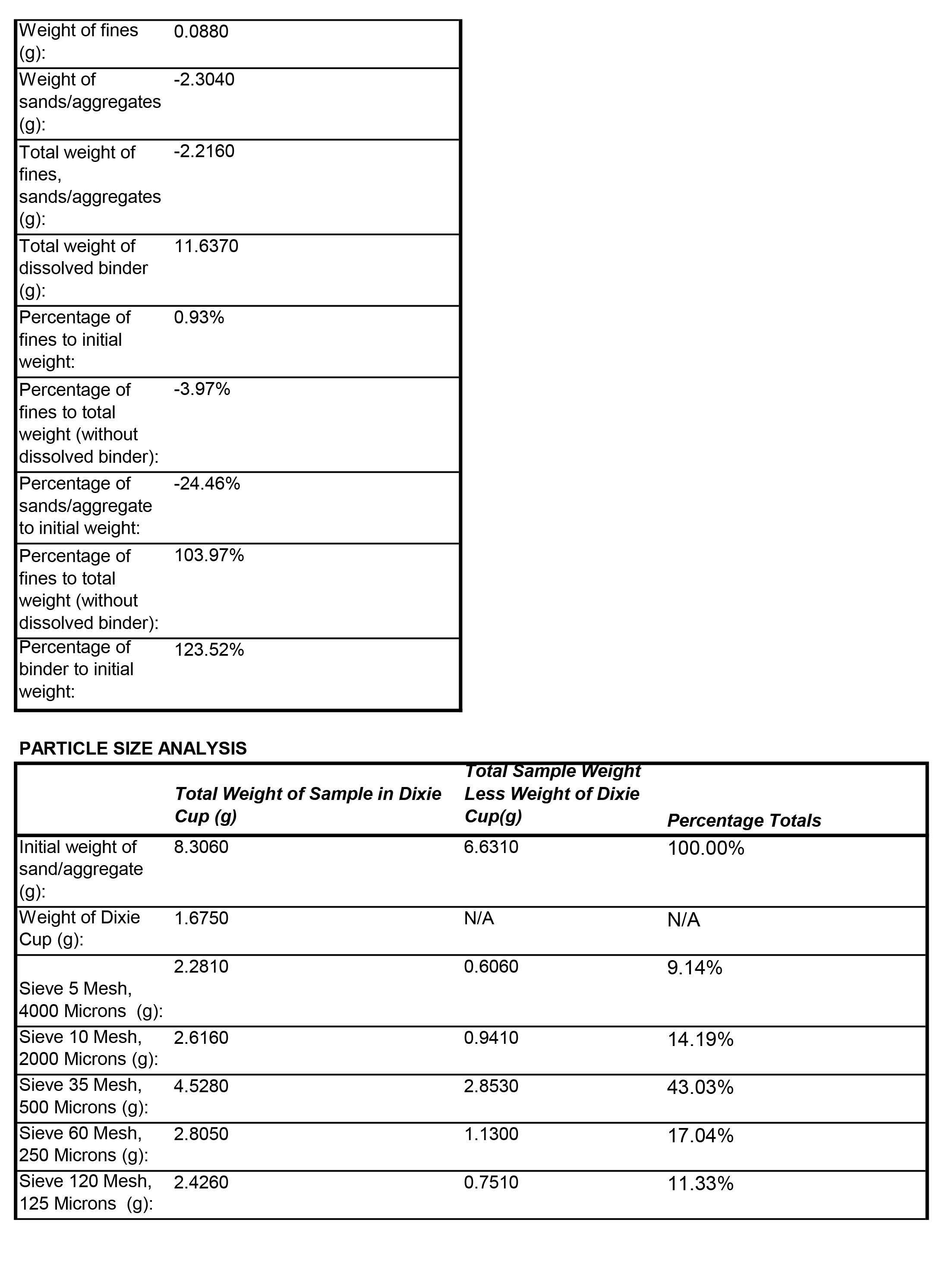

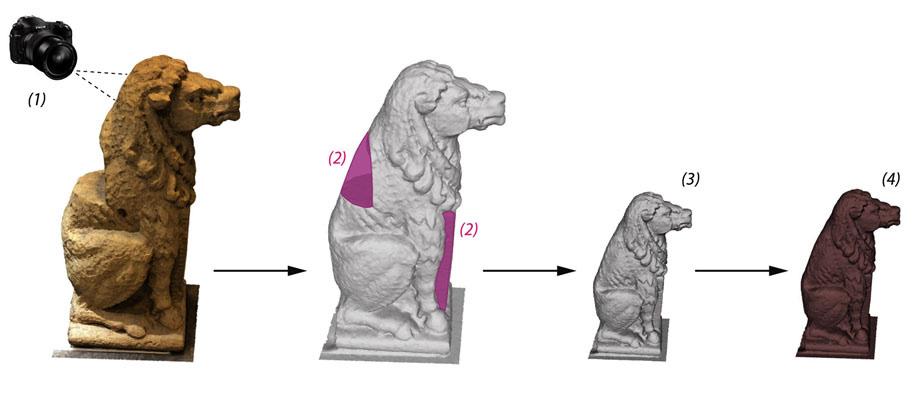

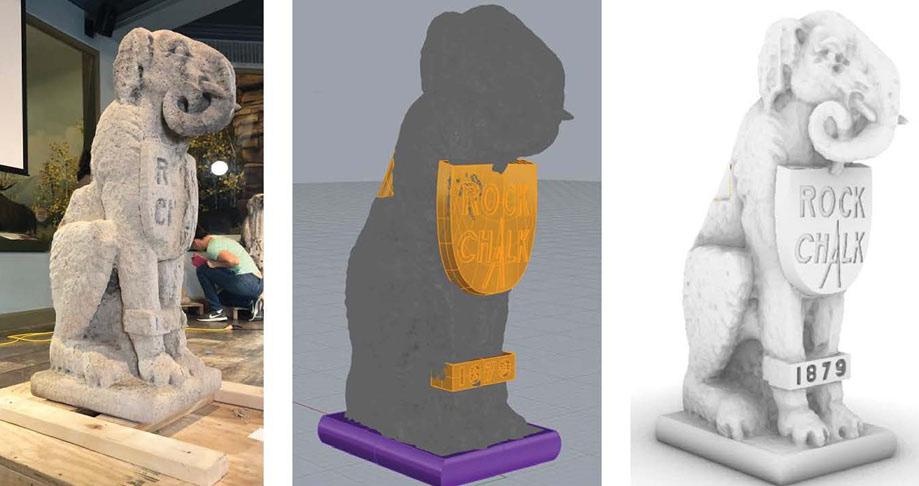

Methodology for documentation, repair and creation of maquettes for final approval, prior to purchasing cottonwood limestone blocks: (1) grotesques were documented with photogrammetry and other means to create a database on each statue, (2) digital models were repaired in areas of significant deterioration, replaced lettering or in the case of the back notch where the statues were inserted into the building, (3) each grotesque was 3D printed at ¼ scale, and (4) 3D printed models were enhanced with modeling clay by the sculptors and presented for approval to relevant stakeholders at the museum and KU campus facilities.

Survey of deteriorated areas on grotesques, with prevalent delamination of limestone bedding planes visible (on left). Image of one grotesque to show holistic typical deterioration (right).

Historic photo of Dyche Hall (top) c. 1904. Historic photo of Grotesques being carved by Joseph Roblado Frazee and his son Vitruvius (bottom) c. 1903. Photos courtesy University of Kansas Archive.

Historic photo of Dyche Hall (top) c. 1904. Historic photo of Grotesques being carved by Joseph Roblado Frazee and his son Vitruvius (bottom) c. 1903. Photos courtesy University of Kansas Archive.

Once the models were 3D printed, a variety of molds and castings were explored to assist the museum with replication of the scaled models for use in promotion and gifts to donors. A silicone mold was taken from the 3D print and used to cast in concrete and plaster. (right) Five of the final maquettes presented in a meeting with the museum director, facilities manager and KU campus architects.

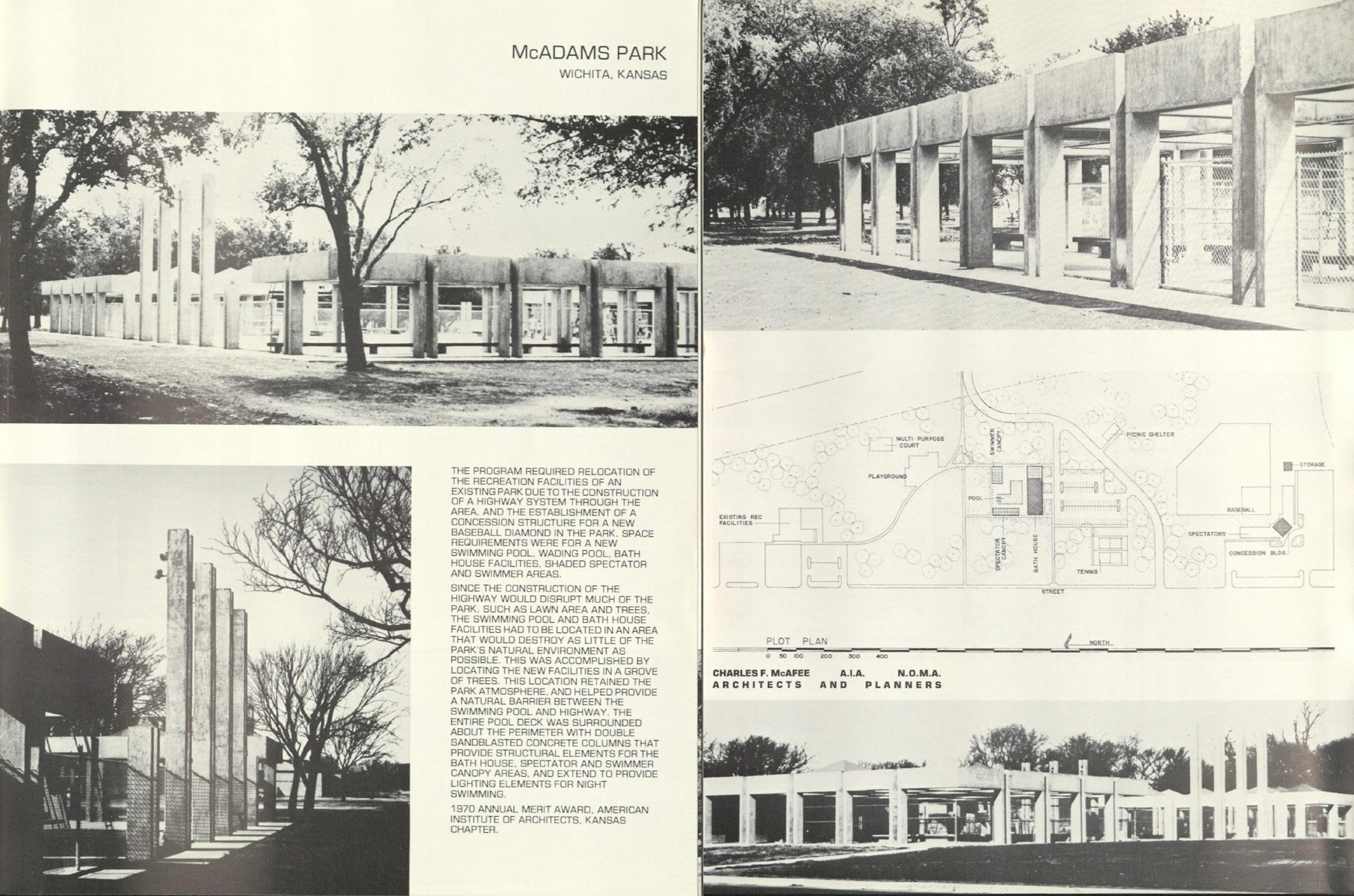

PROJECT: Documenting the Work of Kansas Architect Charles McAfee

PROJECT LOCATION: Wichita, KS

Architect/PI: Amy Van de Riet

Undergraduate Research Assistants: Monet DeFreece & Brittany Perez

The architecture profession in the United States has largely consisted of white male professionals since the creation of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1857. In the last five years, only 18% of licensed architects are women and only 9% of licensed architects identify as racial or ethnic minorities.1 Only 2% of licensed architects are Black/African American and Black/African-American women are just .2% of that total based on information from the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA).2 Underrepresentation of Black/African American architects has been a consistent trend and grows from the low percentage, only about 5%, of Black/African American architecture students enrolled in accredited programs.3

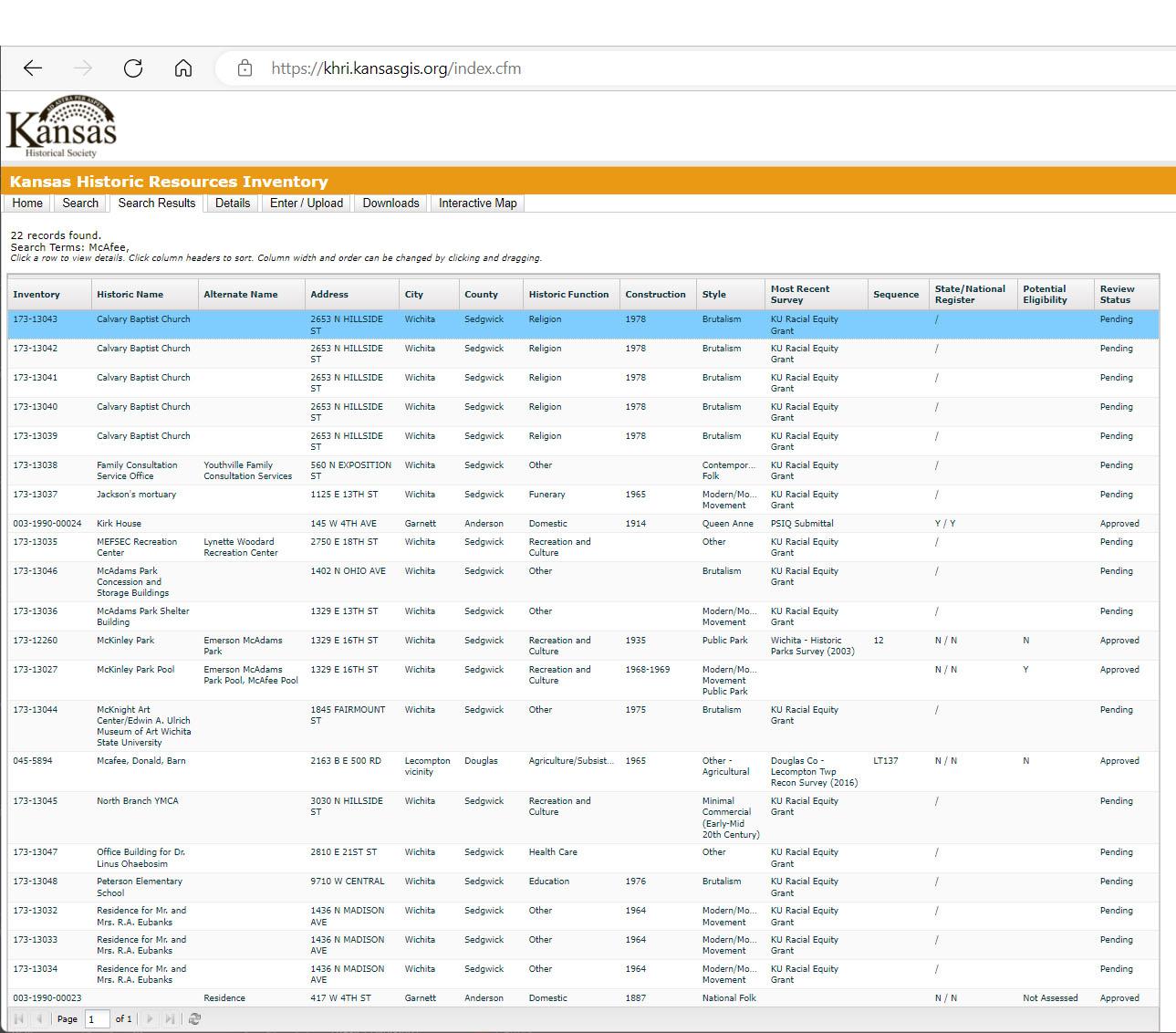

Since there is a small percentage of practicing Black/African American architects, the representation of their work is very limited. For emerging architecture students, lack of representation in the work is unequal and recognition of Black/African American architects is challenging to find. There are three comprehensive resources used to document historic architecture of significance. The most known is the National Register of Historic Places. Typically, buildings tend to be thought of as “historic” in the United States when they reach the fifty-year mark. Buildings completed as recently as 1971 are eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The Historic American Building Survey (HABS) and the Kansas Historic Resource Inventory (KHRI) are large, online collections of historic building information. These three collections house the bulk of documentation and research of historic buildings accessible for all people interested in learning.

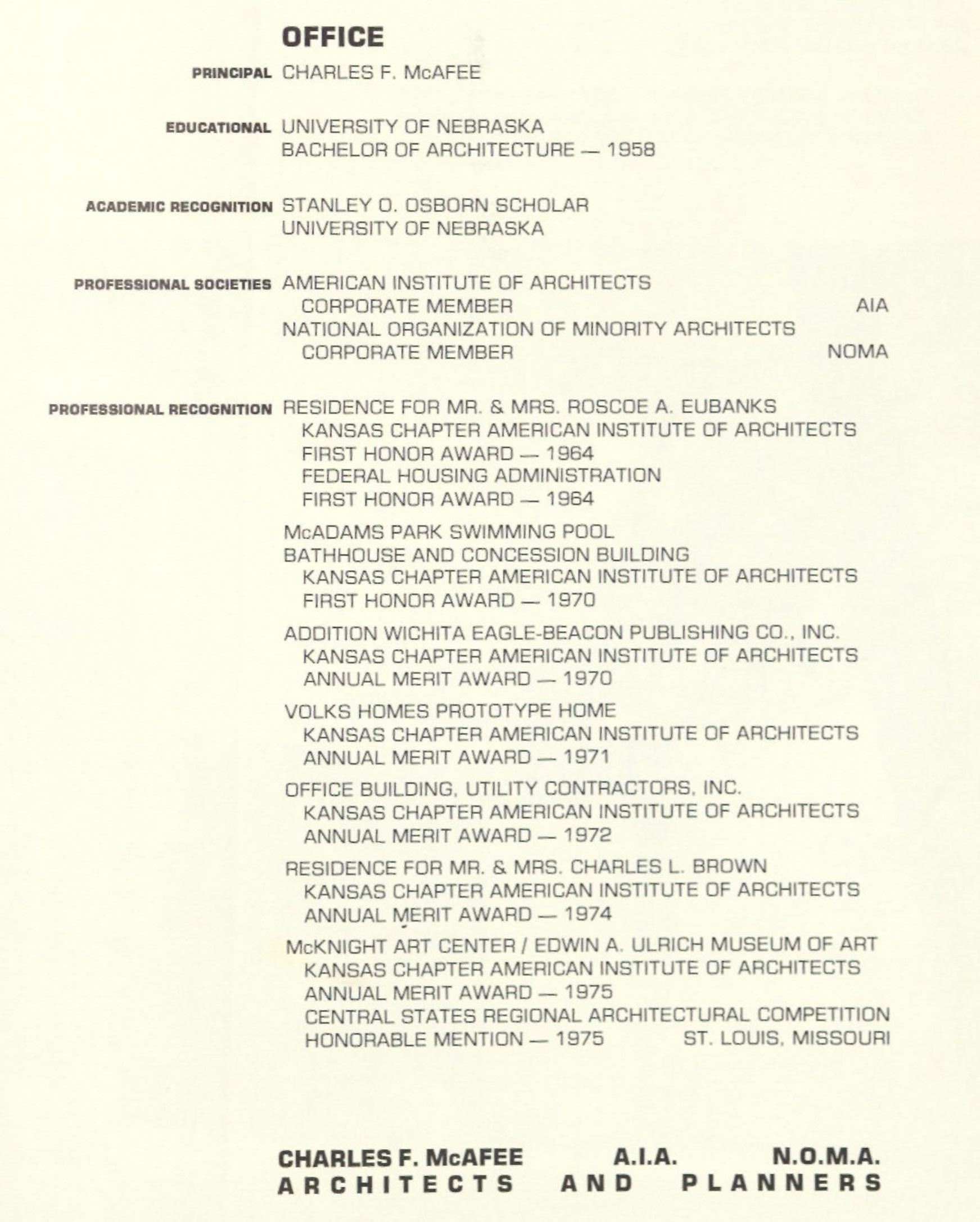

Charles F. McAfee was born in 1932 in Los Angles, California. His family moved to Wichita sometime in his early childhood. He graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Nebraska in 1958. He opened his own practice in 1963, and completed his first award-wining project, “Residence for Mr. & Mrs. Roscoe A. Eubanks” soon after. This project won the Kansas Chapter American Institute of Architects First Honor Award and the Federal Housing Administration First Honor Award both in 1964. To understand the value of this honor, the other winners of the Federal Housing award in 1964 included Pritzker Prize winning architect I.M. Pei, Mies van der Rohe, and architecture powerhouse – Skidmore Owings and Merrill (SOM). More projects and awards followed including multiple Kansas AIA awards. Mr. McAfee was also awarded the honor of the induction into the AIA College of Fellows (FAIA), a prestigious award bestowed upon the most outstanding members of the profession.

The goal of this grant is to strategically document and share the work of Charles McAfee up until 1980. This is of high priority as his work is in danger of demolition, renovation, and being forgotten. There are no buildings designed by licensed Black/African American architects in Kansas in the HABS database. The KHRI database has only one of Charles McAfee buildings credited, and some of his most prominent work gives no name in the entry space for “architect”.

1“NBTN 2016 Demographics” (NCARB - National Council of Architectural Registration Boards, June 28, 2017), https://www.ncarb.org/ nbtn2016/demographics.

2Sunra Thompson, “On Race & Architecture,” Curbed New York, February 22, 2017, https://archive.curbed.com/2017/2/22/14677844/ architecture-diversity-inclusion-race.

3“NAAB 2015 Annual Report” (NAAB, 2015), https://www.naab.org/wp-content/uploads/2015-NAAB-Report-on-Accreditation-in-Architec ture-part-I.pdf.

The project began with research. The Kenneth Spencer Research Library (located at KU), was utilized since the “Kansas Memory” collection had one very important document - the c. 1981 portfolio of Charles McAfee. This document had the work of Charles McAfee from his first project in 1964 (Eubanks Residence) up until work in 1980. In 1981 his daughter Cheryl McAfee joined the practice as the first licensed African American/Black female architect in the state of Kansas. Her work was not included in the scope as she should be recognized as part of a separate study once more of her buildings are nearing the 50-year age mark indicating “historic” status. Newspaper searches, and contacting other archives did not yield much additional information.

Mr. McAfee is still alive, and contacted by phone to discuss work and add information. Multiple recorded interviews are available online, and those were watched to garner any additional information. The images on this page are all from Charles McAfee portfolio accessed from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library “Kansas Memory” collection.

The work completed in summer of 2022 included two undergraduate students, Monet DeFreece and Brittany Perez. The KU Racial Equity Grant provided funding to pay them for their work and travel to Wichita, Kansas. Using the portfolio of work of Mr. McAfee as a guide, twelve buildings were identified as potential sites prior to starting the site visits. Each building was surveyed in person, one student would take photos while the other student filled out the KHRI database form. Then the students would switch roles for the next building. We met with some, but not all property owners. The property owners all received a mailing prior to the survey to let them know about the project and when we would be on site.

Our outcome for the first phase was uploaded to the KHRI database and finalized hopefully by fall 2022. We also identified several buildings that would be potential subjects for the HABS project to be completed summer 2023. That work will also be completed by students paid through the grant for their time and travel.

All photos on this page are from survey of sites.

COMPLETION…updated KHRI database

PROJECT: 3D Drone Scanning Archaeological Ruins

PROJECT LOCATION: Near Baldwin City, Kansas (exact locations of archaeological sites cannot be revealed)

Architect: Amy Van de Riet

Archaeologist: Dr. Nicholaus Pumphrey, Baker University

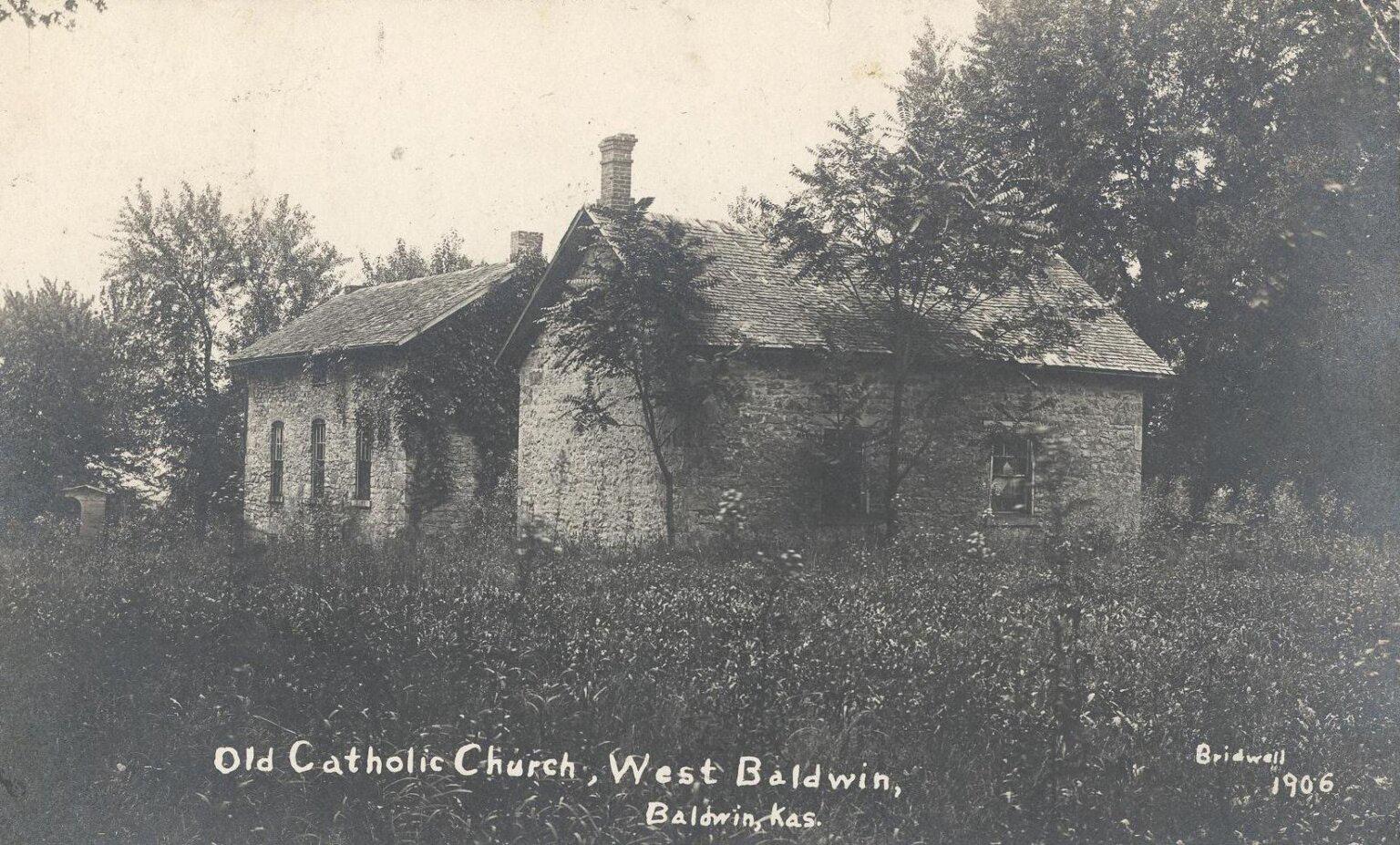

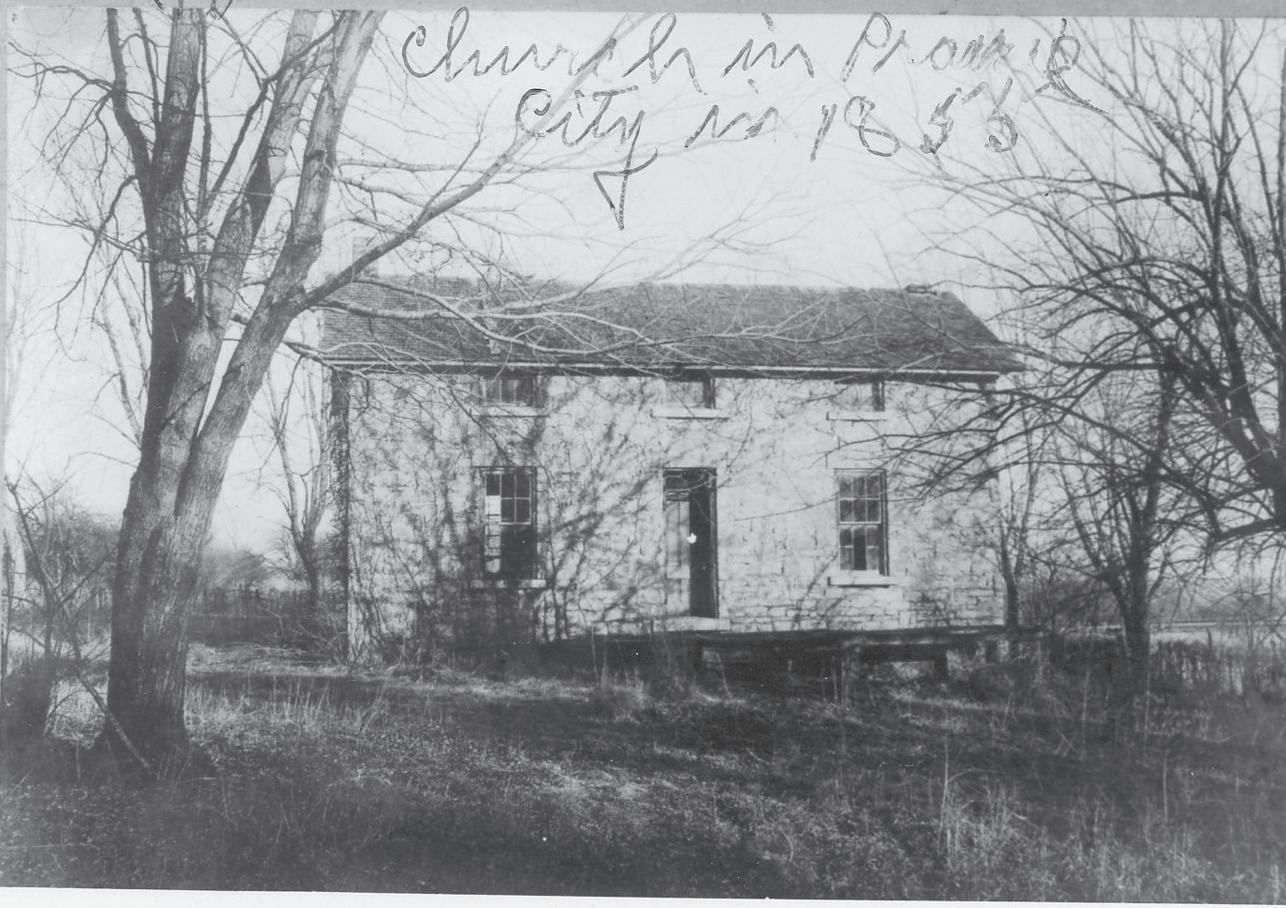

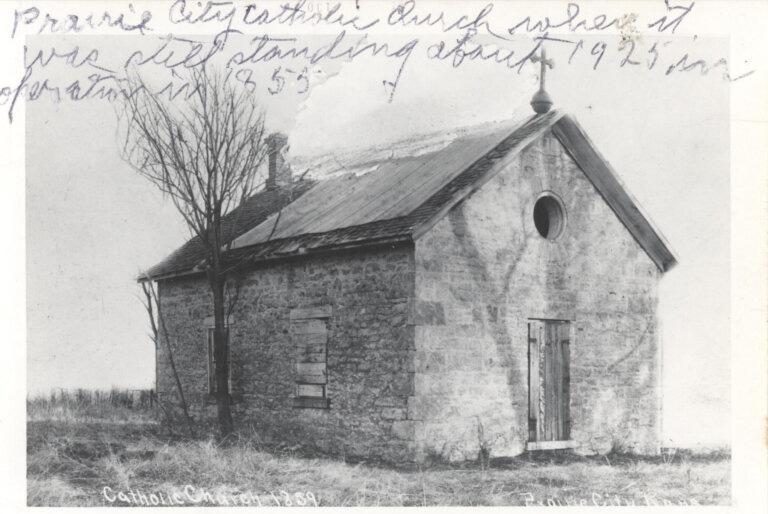

The stone church constructed in 1859 was the home of the Catholic Mission Church until about 1893. The site originally had a log cabin in use as the first Jesuit Missionary in 1857, remains of this building have not been identified. To the south of the Annunciation Catholic Church, the stone seminary was constructed in 1870. The stone church was about 20’x30’. The stone was quarried from nearby, the quarry now used as a pond, but stone around the edges matches the church.

The project was derived from collaboration with archaeologist Dr. Nicholaus Pumphrey (Associate Professor Religious Studies at Baker University). During the online education era of Covid, Dr. Pumphrey was creating a course “Digital Archaeology” and wanted to include the study of a nearby ruin. Because the students would be online, they would not be able to make a site visit. Dr. Pumphrey and I decided that the site could be “accessed” by creating digital content of the site, and use that for educational purposes. I first used drone scans to document the site in photographs. Then took terrestrial photos as well. The drone photos were then generated into a 3D model using photogrammetry (RealityCapture software). The 3D models were used for study in the class. The site is also on private land, and landowners were interested in ways in which the site could be digitally accessed. The project continues to evolve as we generate more digital content. Utilizing VR, a 3D “site visit” will be generated next. This will allow for “tourism” to the site without compromising the integrity of the site as both an archaeological ruin and privately owned.

1859 Stone Catholic Mission Church viewed from the front (West) from 1920 photograph (top left). 1870 Stone Catholic Seminary and Priest Home viewed from the front (West) from 1920s photograph (top right).

1859 Stone Catholic Mission Church (Rt) & 1870 Seminary & Priest Home (Lt), old Prairie City, view from East (rear) – 1906 Bridwell photograph (bottom)

All photos are courtesy of the Santa Fe Trail Historical Society.