PATRICK WILSON

PATRICK WILSON

THE CONDITION OF COLOR

By Dan Cameron

Artists today have enough to contend with in satisfying a demanding public that insists on both a singularity of vision and an instantly recognizable style. Still, the most self-aware among them also remain closely attuned to the seldom-voiced principle that every work of art, regardless of its apparent content or genre, maintains a parallel life as a snapshot, or possibly an X-ray, of the time, place, and circumstances that made its creation not just possible, but necessary.

When it comes to the rarefied compositions and finely tuned palette that define the paintings of the Southern California artist Patrick Wilson, one doesn’t have to search far to locate the presentday conditions that conspire to make such refined work seem like an antidote found in an oasis.

As recently as the dawn of this century, it would have been difficult to collectively picture a world in which so many among us appear to have surrendered their sensorial autonomy to the roving panopticon of flat rectangular surfaces with built-in cameras, all illuminated from within, that operate simultaneously all around us as portals to infinity and perceptual traps. Sometimes, we even find ourselves peering longingly into their simulated depths, much as Narcissus gazed into his fateful pool, while we gamely strive to confirm who we are and what we really want—comparing prices of things we might buy and checking to see who liked that photo we posted a few hours ago. Try as we might, we can’t seem to keep ourselves from taking one more peek.

Wilson wisely takes as a given our mass addiction to pads, smartphones, laptops, and watches, largely because the alternative that effectively ups the ante is paintings, which instead of catering to the whims of passive engagement deploy subtlety and visual seduction to pull viewers inside the composition and compel them to keep looking for a pattern or formula that holds everything

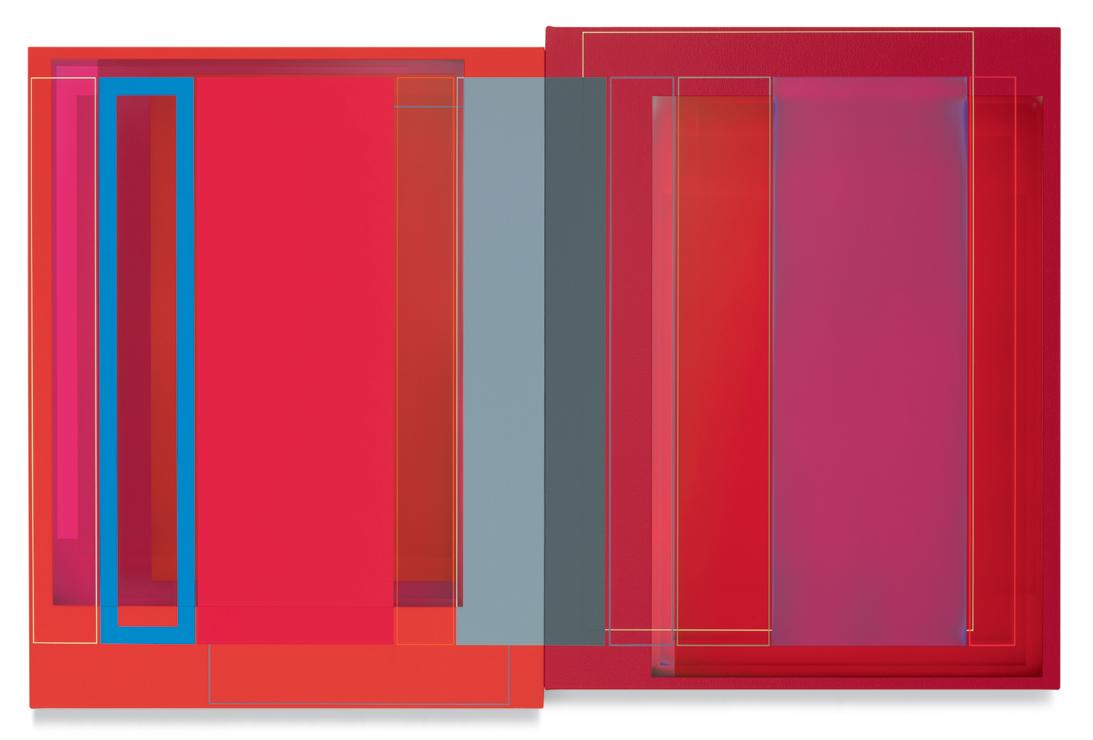

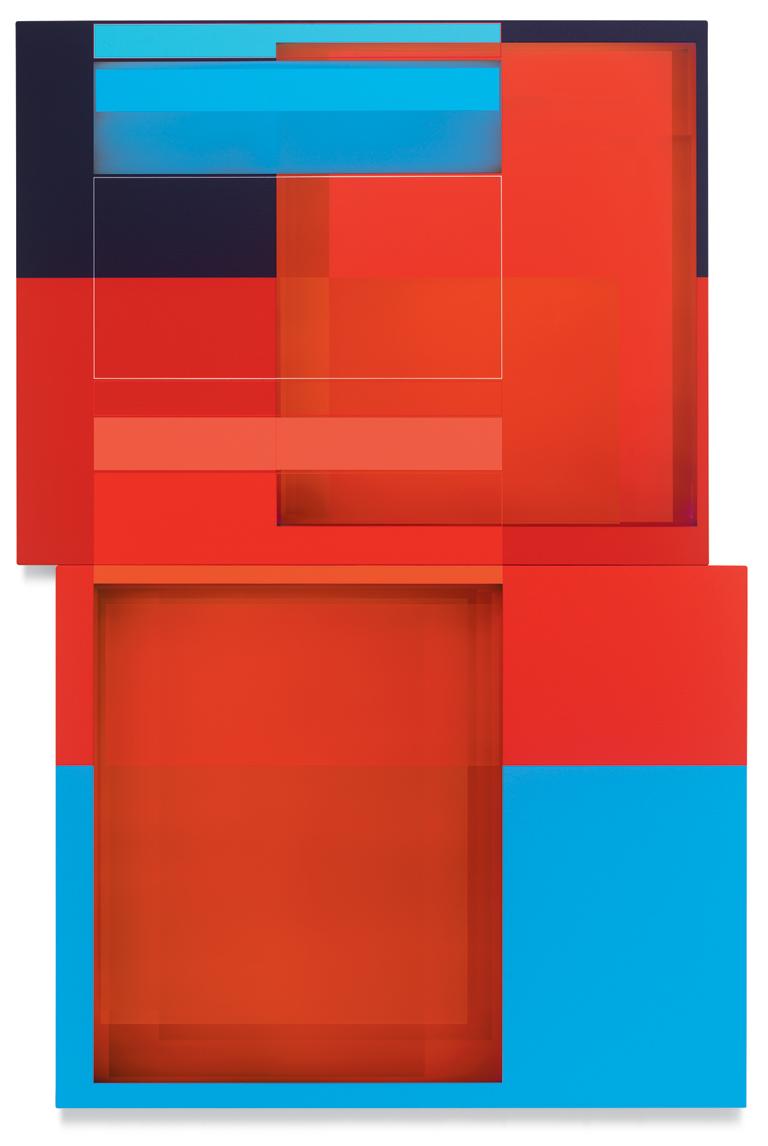

together. A master of color who isn’t shy about keying up the intensity level of brightness and saturation in his palette, Wilson builds up his compositions by using every conceivable size and proportion of rectangle to offset and highlight the other rectangles, with narrow gaps and outlines transformed into dynamic parts of the composition. One of his favorite devices is to exploit the ambiguity of a painting’s depth of field by positioning shapes so they seem to be floating in front of, adjacent to, or behind other shapes, even with all of them appearing to be either opaque or partially translucent. Our cognitive faculties struggle to establish where certain forms are positioned relative to other shapes, but the incoming visual data is both methodically precise and maddeningly ambiguous. In the painting Premium Velocity, two narrow, standing rectangular shapes made by banded outlines stand on opposite sides of a pair of asymmetrically connected panels. One of the rectangles is rendered in red on a blue ground, while the other is blue on red, and as our view shifts from left to right and back again, whichever one we are looking at directly winds up in the foreground, even while our brain gently insists that it needs to be either one or the other.

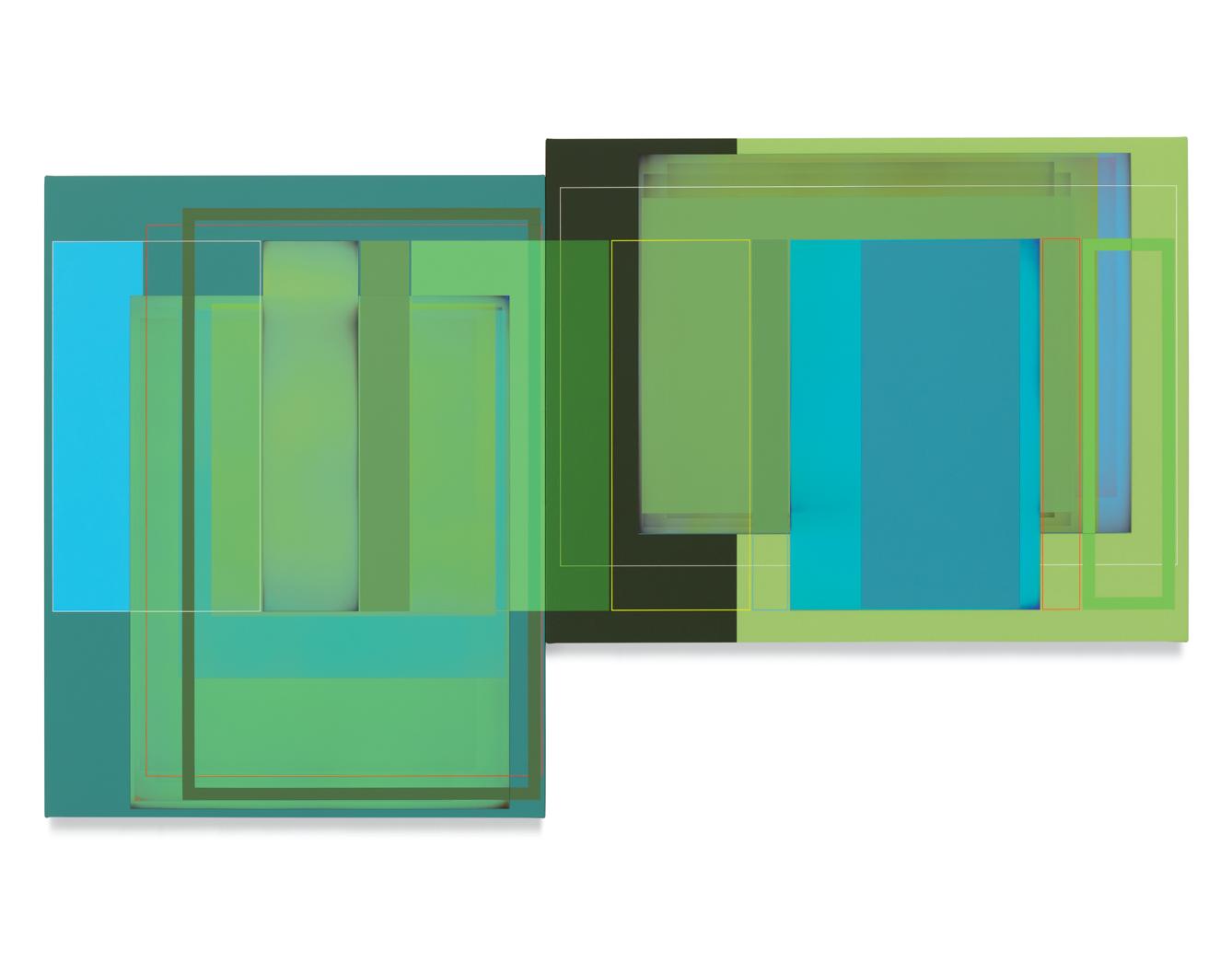

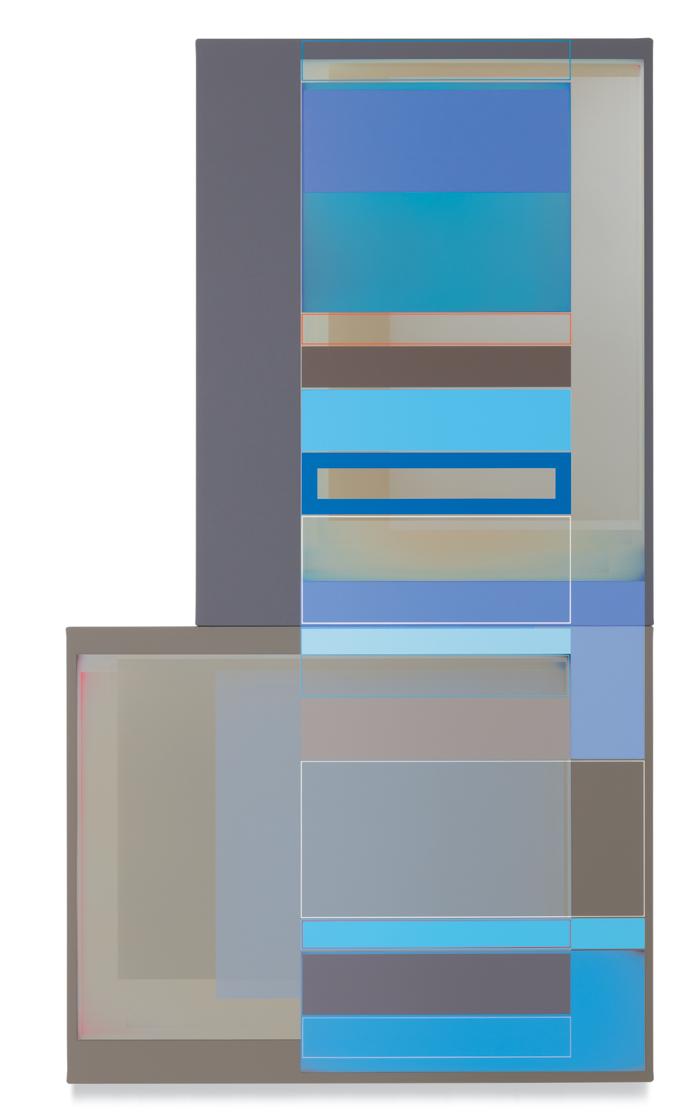

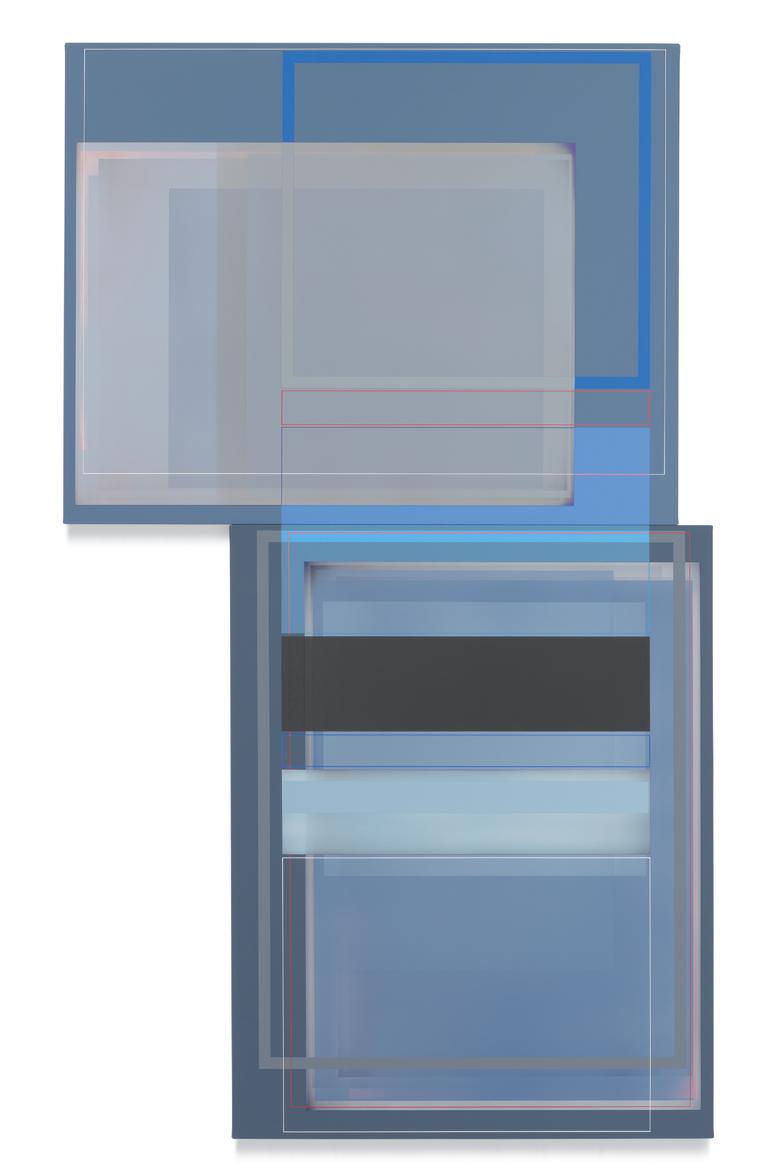

Until recently, Wilson limited his chromatic experiments to a single rectangular format within which pyrotechnics were kept in relative check by four rigid boundaries, but he has now raised the bar of complexity by combining individual panels into binary compositions that are aligned either vertically or horizontally, and are always offset by an inch or three. Within those fixed limits, nearly every variation is permitted. There’s a vertical two-painting stack in which a horizontal panel sits atop a vertical panel, with the left edges flush (Verde Sauce), and another vertical stack in which a vertical panel rests on an horizontal, their right edges flush (Low Down Dirty Blues). Methodically working through every possible variation within strict parameters has long been part of Wilson’s m.o., and by drawing our attention to the repeated compositional asymmetry within each diptych, he is somehow conversely able to visually reinforce the many passages where both halves dovetail with exquisite precision. Like the others in the series, the panels in Power Chord are conspicuously askew, but the linear continuity between the internal horizontals

stays consistent between them, and that intentional visual contradiction tugs gently at the human compulsion to see all our rectangles lined up in a neat, rational order.

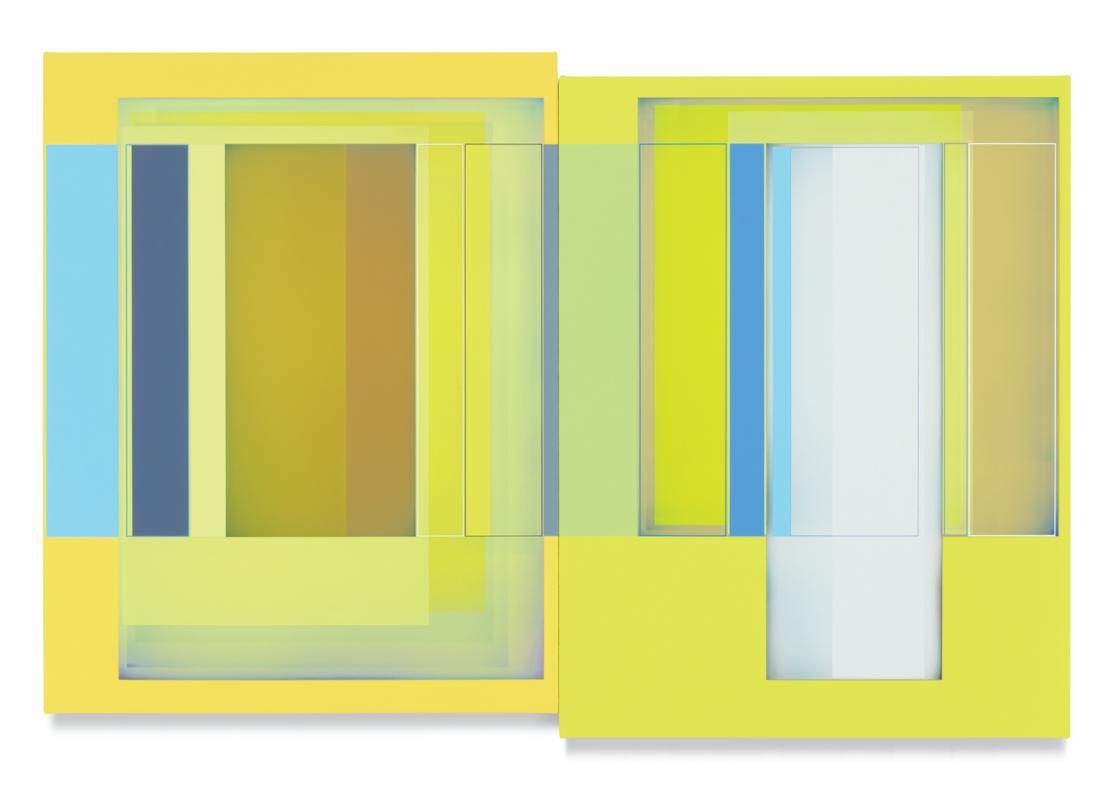

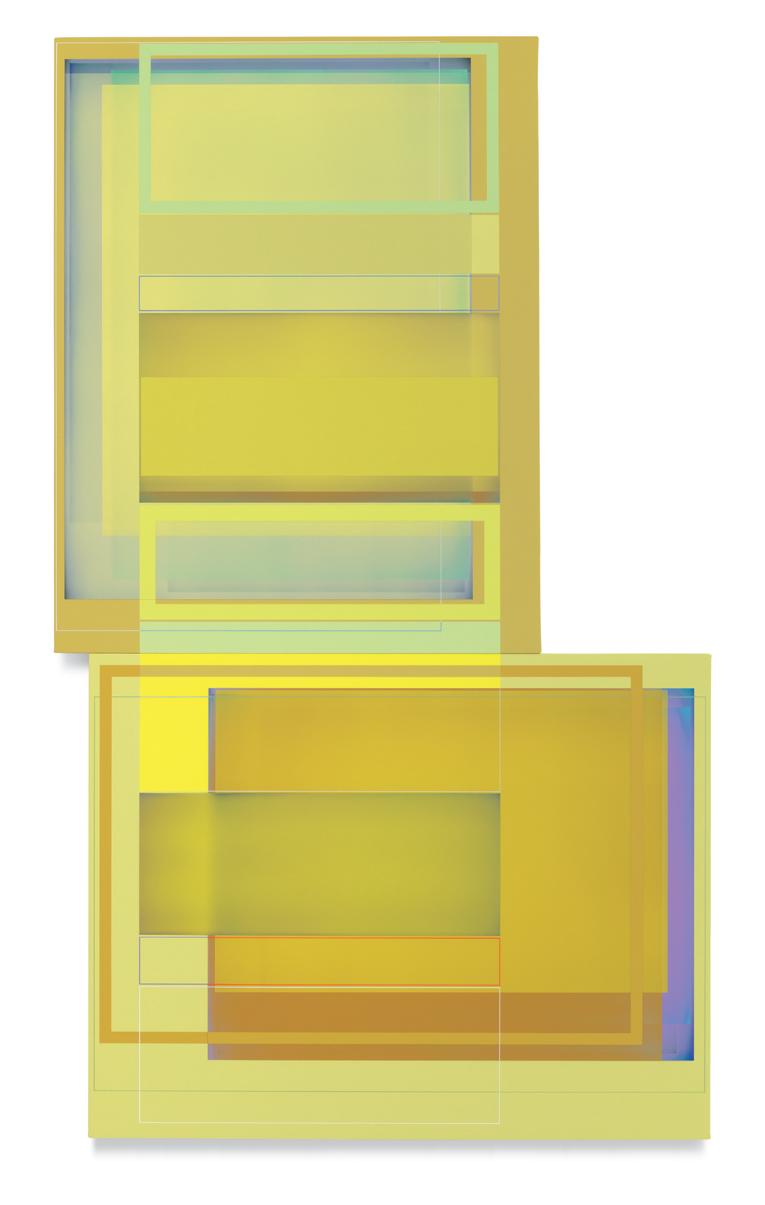

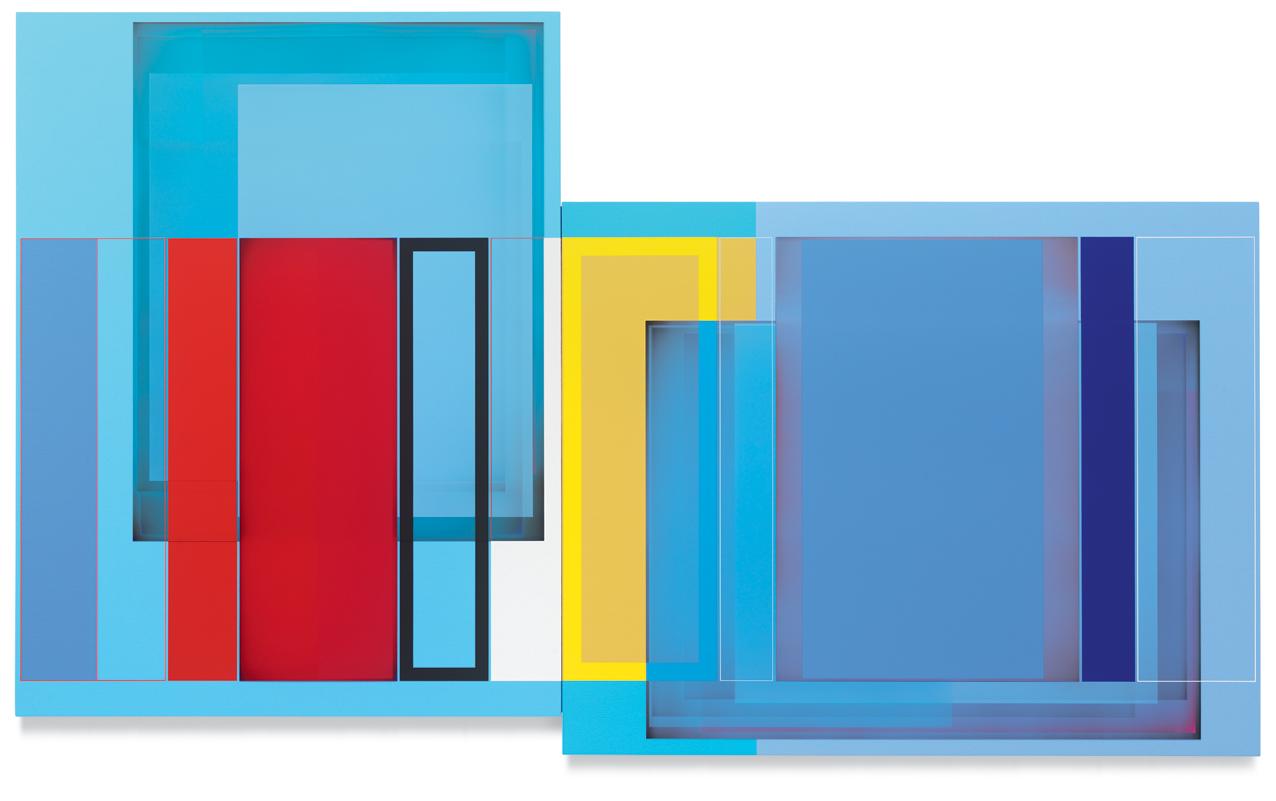

One suspects that Wilson is immeasurably more interested in coaxing maximum chromatic expressiveness from his self-imposed limitations than in providing a visual apologia for rationality. Notwithstanding Wilson’s harder edges, there is a degree of Richard Diebenkorn-like eloquence in his ability to orchestrate more than a dozen blues and purples alongside each other, each with a distinct presence, within a work like Much Later, while interacting in a way that effortlessly moves our gaze from one side to the other. The complementary flash of red at the picture’s center, which in turn brings out faint hints of umber and orange concealed around the edges of other rectangles, offers a visual anchor within a seemingly nocturnal luminosity. A similar effect is achieved with the side-by-side panels of Pacific Gold, wherein the vertical discontinuity of the two parts is mirrored by the paintings’ respective base colors—clashing shades of yellow that don’t easily reconcile. But everything happening inside those discordant boundaries has been gently balanced, in particular the multicolored horizontal band that seems to lash the two sides together in a snug embrace.

To better appreciate Wilson’s accomplishments as they are tied to the history of abstraction, it might be helpful to think of him approaching the problems of color and composition from two markedly different directions. At the art historical end, his European roots extend to such early Constructivist progenitors as Alexander Rodchenko and Theo van Doesburg, and their belief that the vocabulary of abstraction constitutes a perceptual gateway to better principles of social organization. Through the utopian principles behind Constructivism and Suprematism, Wilson’s links extend through the glory days of the American Abstract Artists (AAA) group from the late 1930s through the 1940s, which provided a critical framework for painters like Ilya Bolotowsky and Burgoyne Diller, who sought to articulate a philosophical order through the geometric language of visual expression. Although the AAA’s accomplishments were soon overshadowed by the triumphs

of the New York School, and the Abstract Expressionist movement in particular, the broad defense of abstraction in the face of establishment resistance to nonfigurative art helped pave the way for a later generation of artists to push the limits of abstraction to ever-greater extremes, leading to the conceptually based methodologies of Sol LeWitt or the structural complexities of Frank Stella.

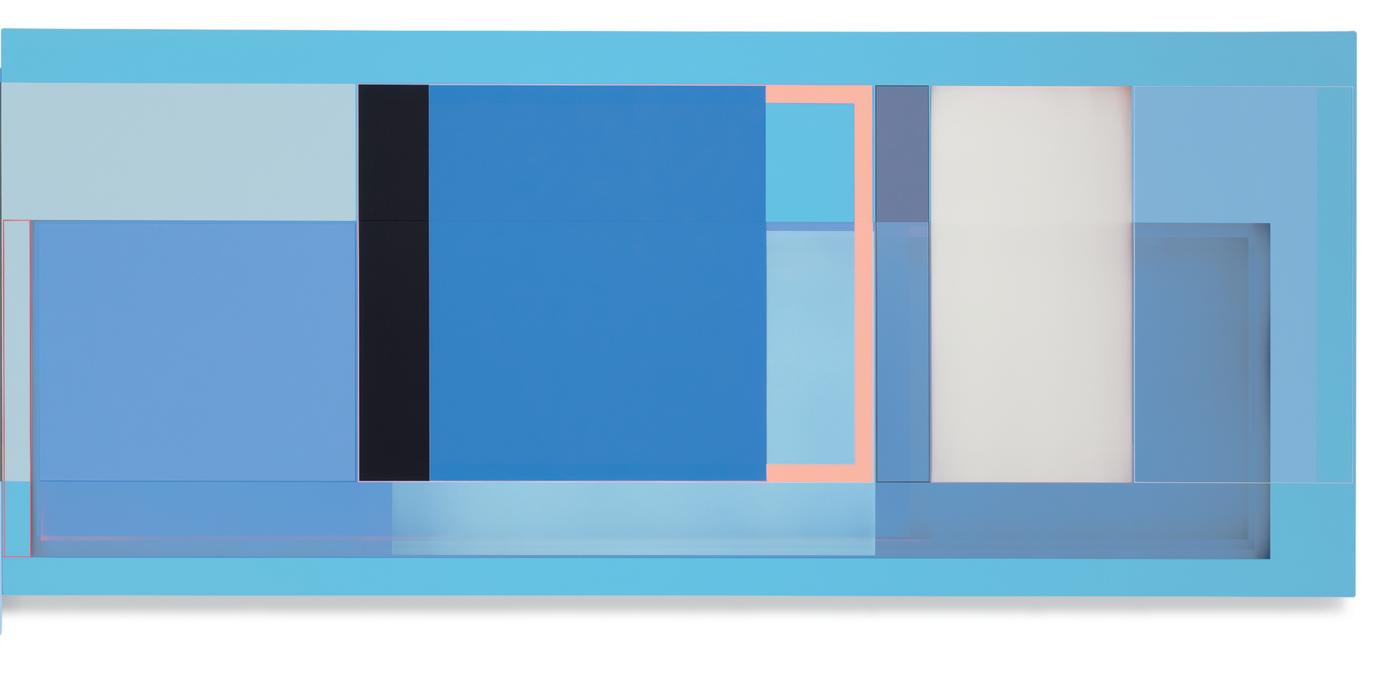

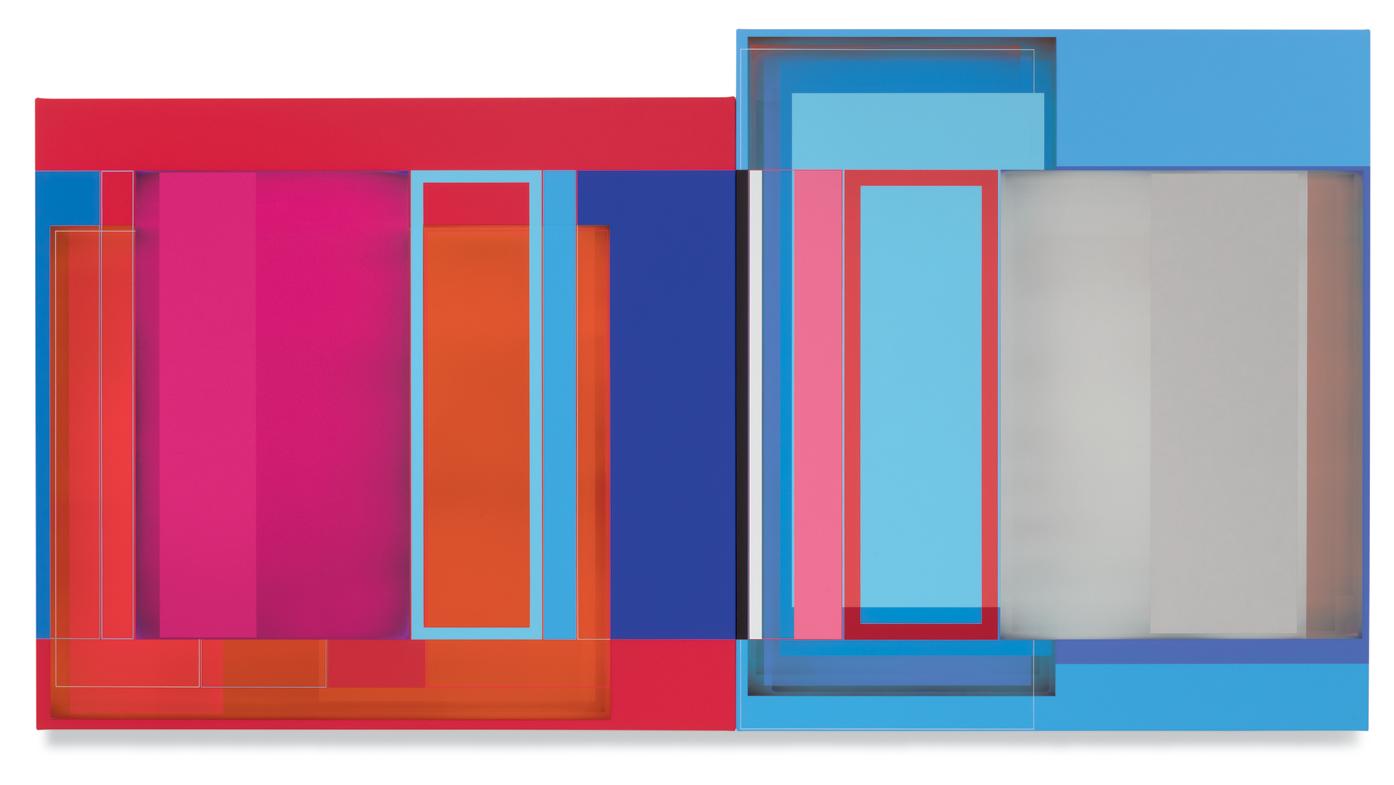

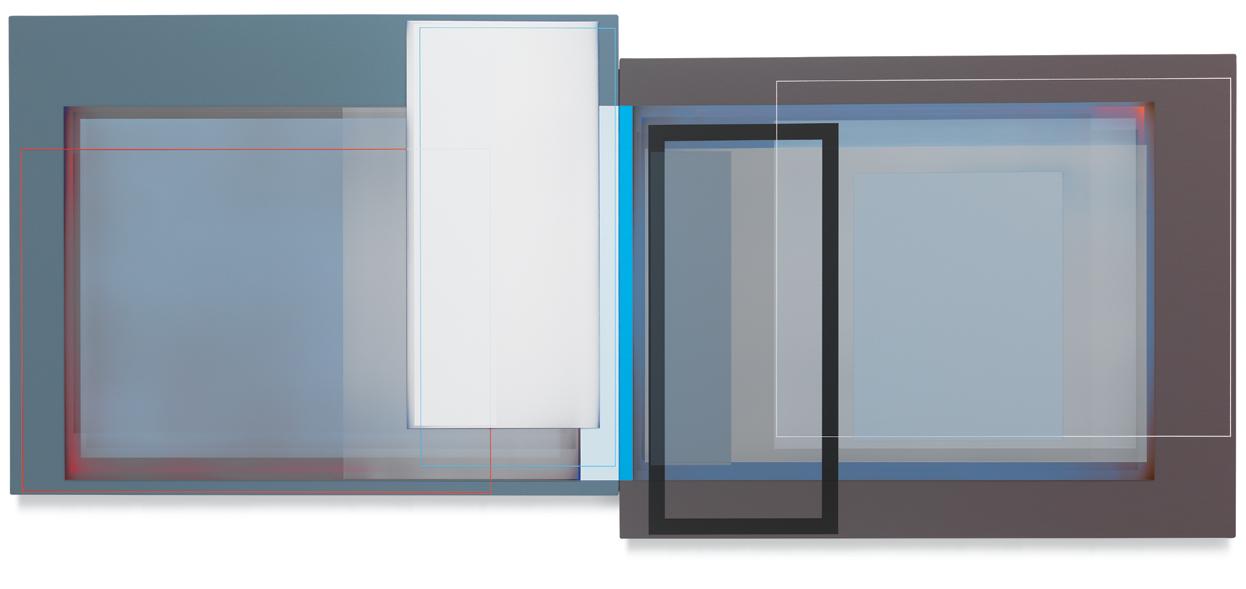

At that stylistic juncture, Wilson’s evolution as a West Coast abstractionist indicates a decisive turning away from formalist approaches to abstraction, moving into the more luminous, metaphysical embrace of the Light and Space generation, whose apotheosis can be seen in the shimmering oases created by James Turrell, Robert Irwin, Doug Wheeler, and others. Like them, Wilson’s choice of palette is grounded in the apparent belief that the sheer intensity of our experience of color is a major determinant of its capacity to affect us at the deepest levels of subjectivity, in a sense bypassing the gatekeepers of referential color to mine its limitless sensuality. As much as they adhere to fundamental ideals of composition and structure, Wilson’s paintings nonetheless invite us to look into and through them, to experience their chromatic exuberance as a different sort of portal. Despite their complete absence of representational imagery, his works even seem to stand for an idealized approach to color organization—an equilibrium forged out of difference. The two halves of First Flight, for example, are each structured according to distinct visual principles: The right half is dominated by a royal blue shape distinguished by a black band running along the left side and a bright orange “handle” extending from the right, while by comparison the more harmonious left half appears to recede slightly in space. (It also hangs a few inches lower.) Adding to the ungainliness of the match is the exaggerated horizontality of the full diptych, with a combined length nearly five times its height. Wilson’s pairing of them as a merged composite enables him to emphasize a unified compositional structure that runs the full length of the two rectangles, again visually contradicting the imbalance suggested by their varying heights. As if to further complicate our experience, Wilson’s choice of title, First Flight, hints at a possible reading in which the right-hand panel exists at a slightly later moment in time, and at a slightly closer distance to heaven.

Quite apart from his artistic roots in early abstract painting, and in light of his commitment to a keyed-up, almost visceral, palette, Wilson goes to considerable lengths to avoid the use of color as a tool of perceptual manipulation. His thrumming blues and electric reds are indeed turbocharged in order to stop viewers in their tracks, but purely as an enticement for us to study them more closely and, perhaps, to unpack some of the hidden structural riddles that bind each composition together. That Wilson is presenting pairs of rectangles to contemplate in place of singular images slyly underscores the simple reality that our view of the outer world is through pairs of eyes, while our brains do the job of stitching the separate data streams into a unified field of perception. Conversely, the diptychs appear to be most in sync with us when our gaze is actively traversing them back and forth, or up and down. That leads us to the conditional suspension of disbelief that in turn gives us the short-term ability to keep two autonomous pictorial compositions in our range of vision at the same time. Geometrically derived abstraction is barely a hundred years old, and yet somehow it has managed to reinvent itself with each passing era. At this juncture in the 21st century, when constant digital bombardment has the infinite potential to induce a numbing sensorial fatigue, abstract painting as Patrick Wilson practices it astutely demonstrates that it can be more than a match for the visual cacophony of the streaming age—primarily by seducing our eyes into doing the journeying for us.

Dan Cameron is a New York-based curator and art writer.

Figurative Painting, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

74 x 31 inches

188 x 78.7 cm

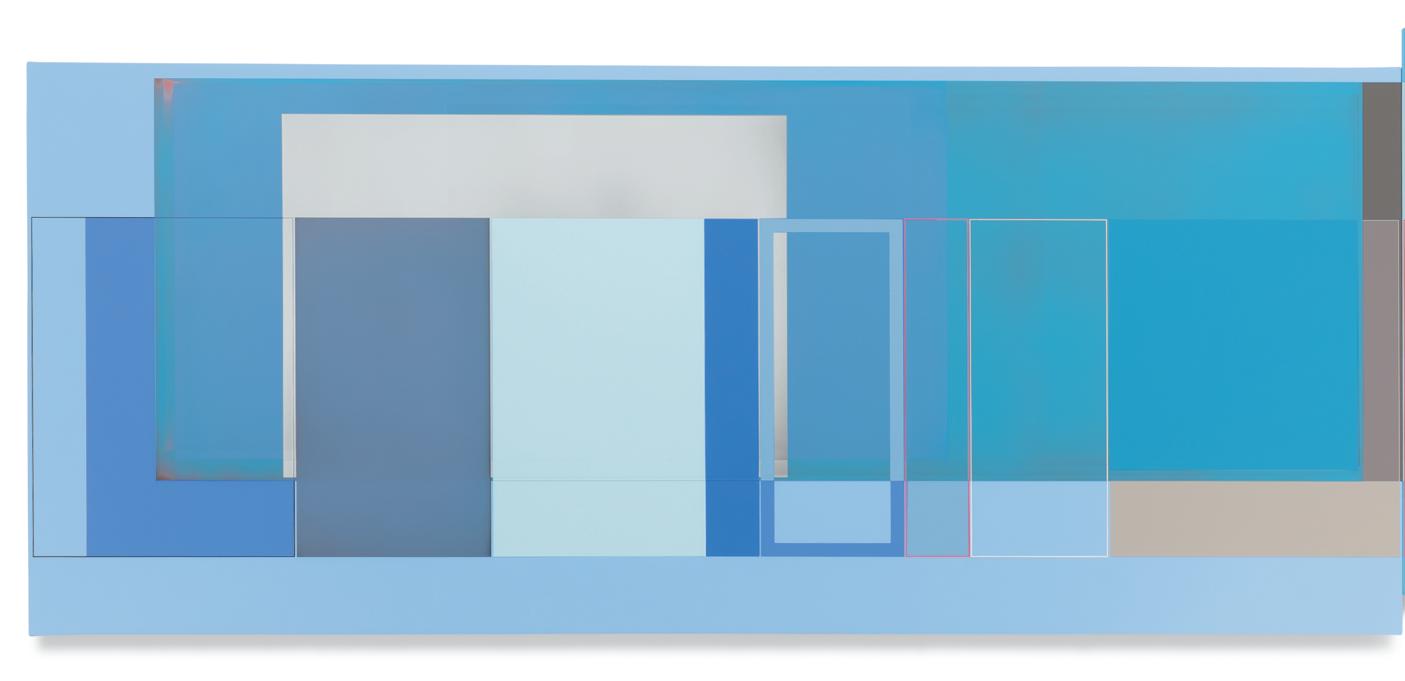

First Flight, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

32 x 144 inches

81.3 x 365.8 cm

Lady Luck, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

39 x 66 inches

99.1 x 167.6 cm

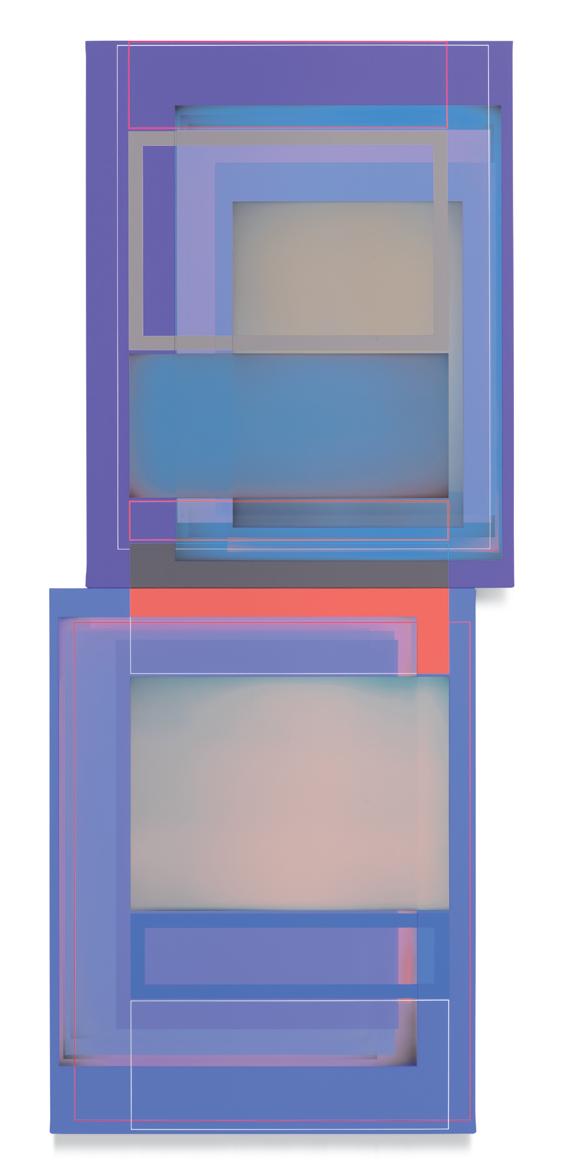

Low Down Dirty Blues, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

48 x 27 inches

121.9 x 68.6 cm

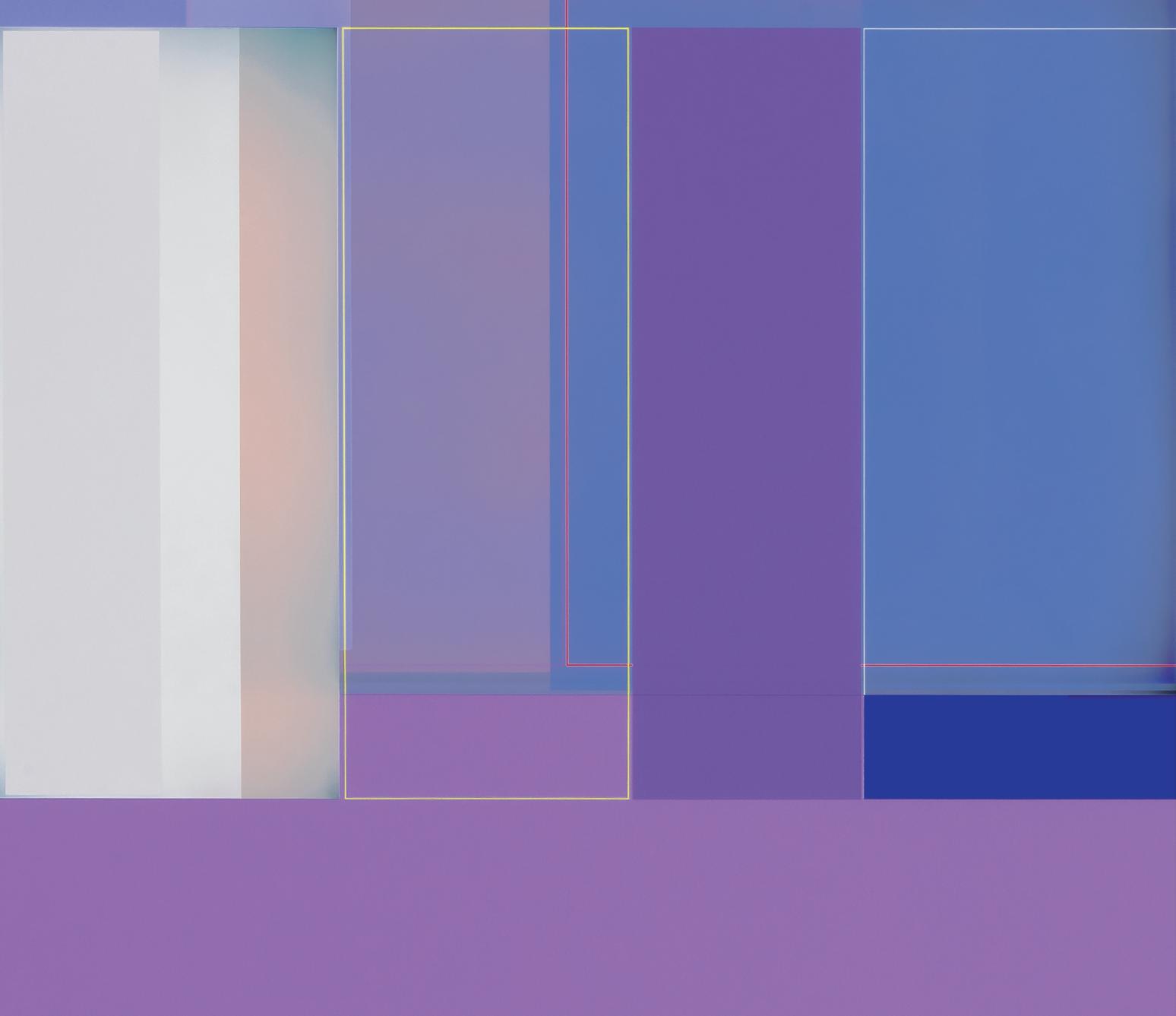

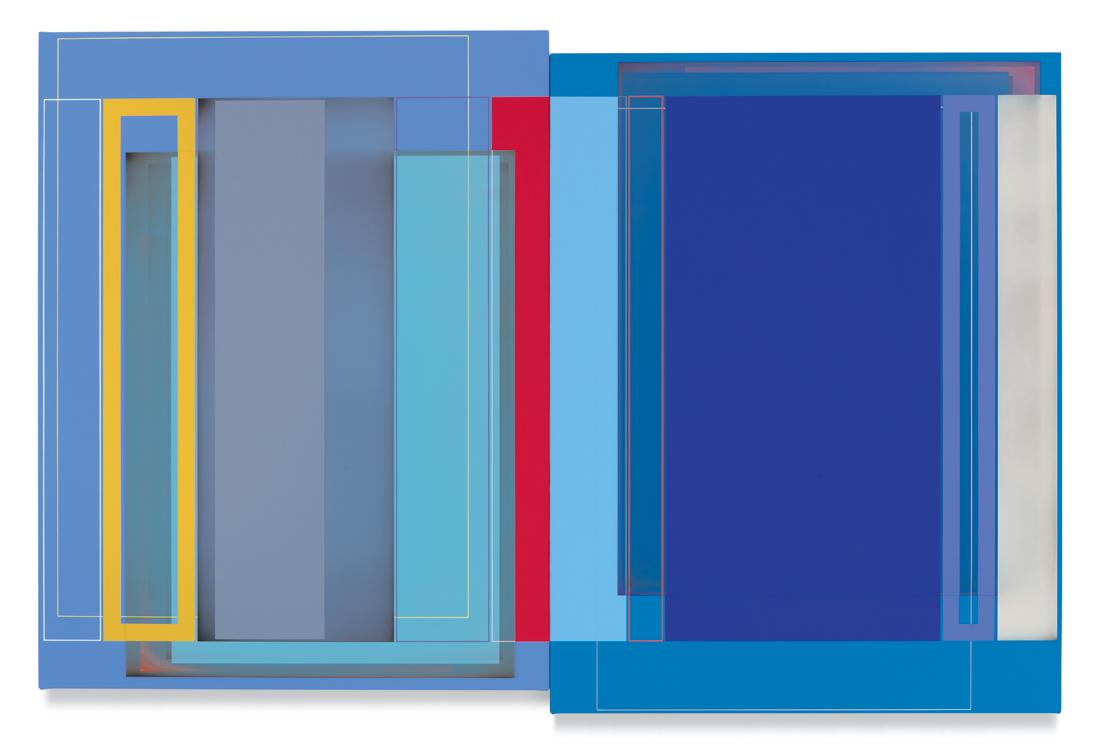

Much Later, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

41 x 78 inches

104.1 x 198.1 cm

Pacific Gold, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

28 x 42 inches

71.1 x 106.7 cm

Best, 2021

Personal

Acrylic on canvas

66 x 39 inches

167.6 x 99.1 cm

Power Chord, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

28 x 42 inches

71.1 x 106.7 cm

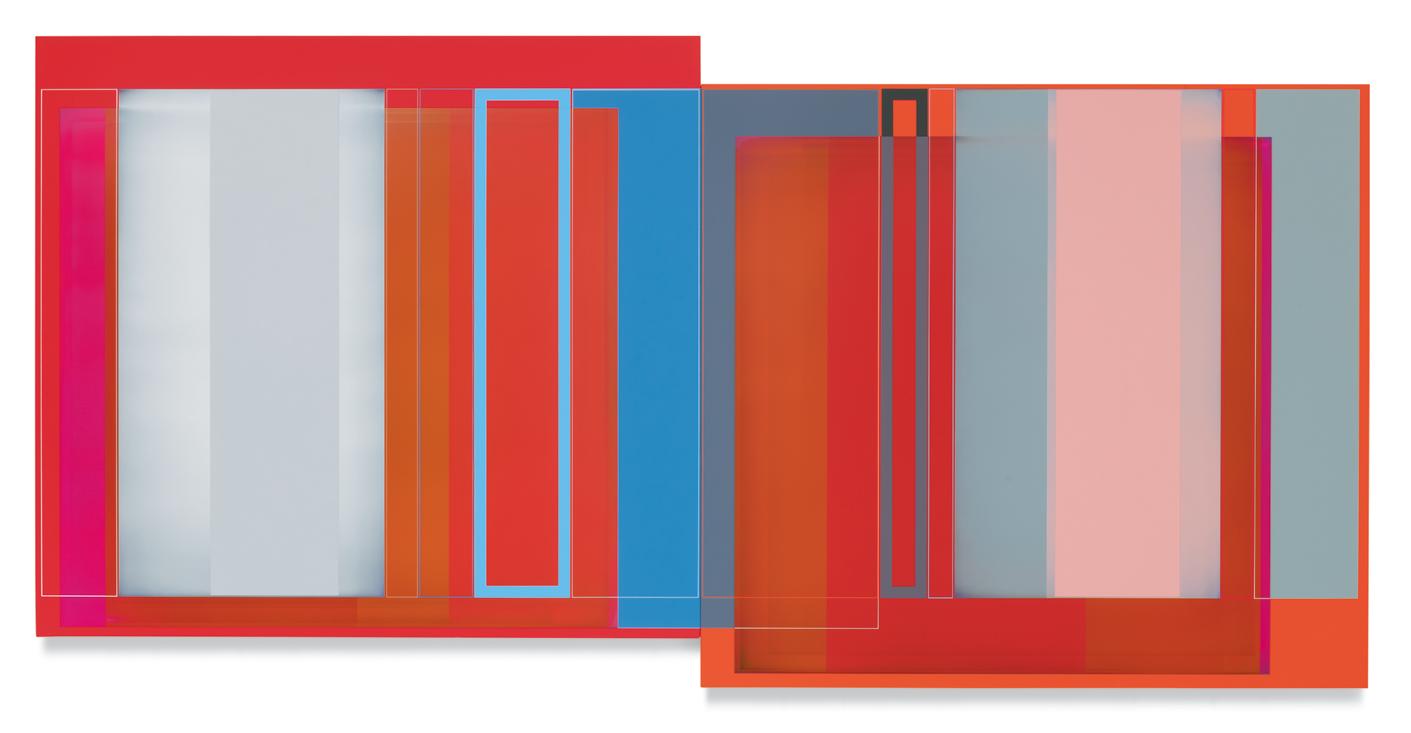

Premium Velocity, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

41 x 78 inches

104.1 x 198.1 cm

Shark Water, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

66 x 39 inches

167.6 x 99.1 cm

Smokestack, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

54 x 23 inches

137.2 x 58.4 cm

in Numbers, 2021

Strength

Acrylic on canvas

28 x 42 inches

71.1 x 106.7 cm

Sunset Strip, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

40 x 82 inches

101.6 x 208.3 cm

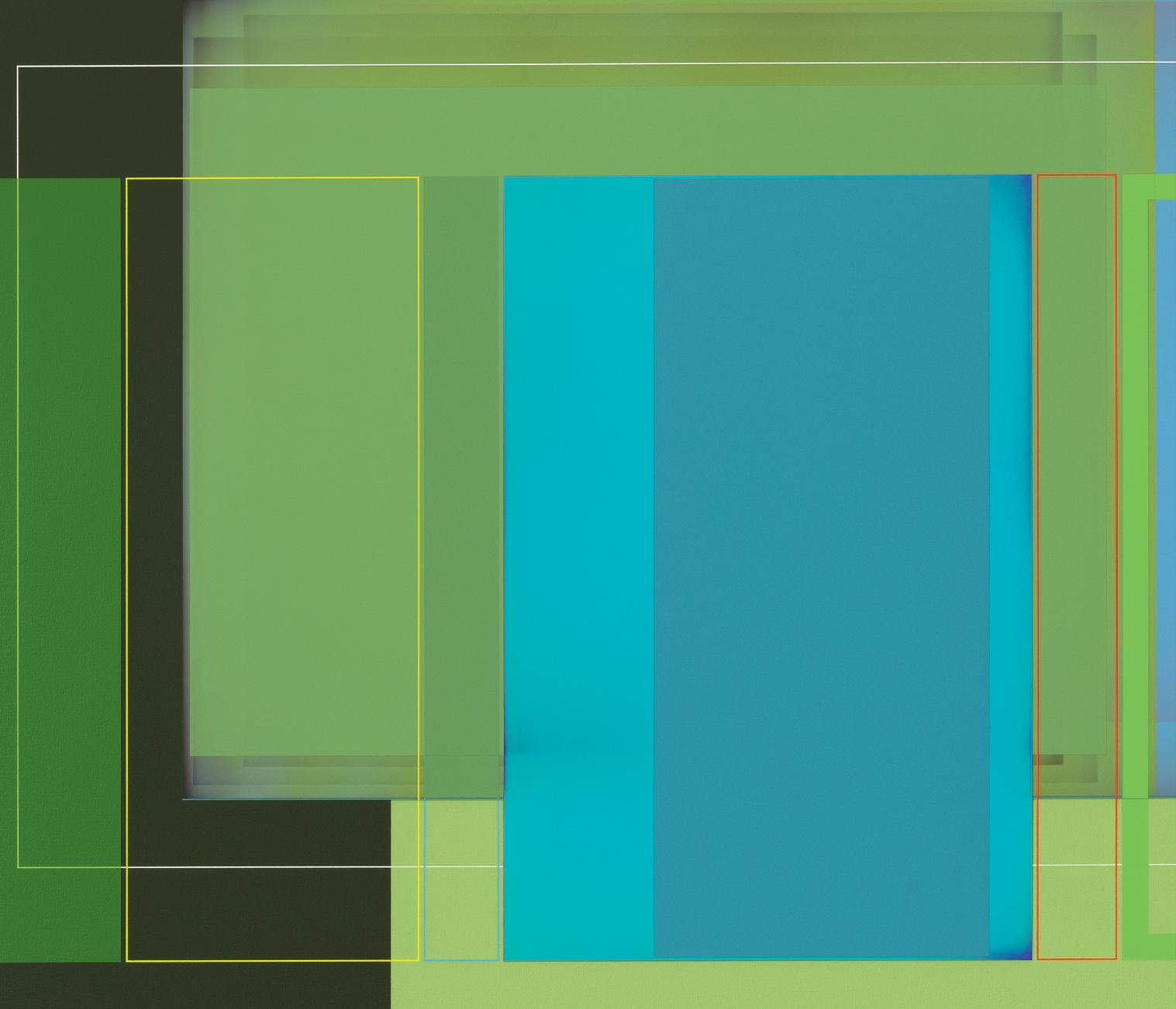

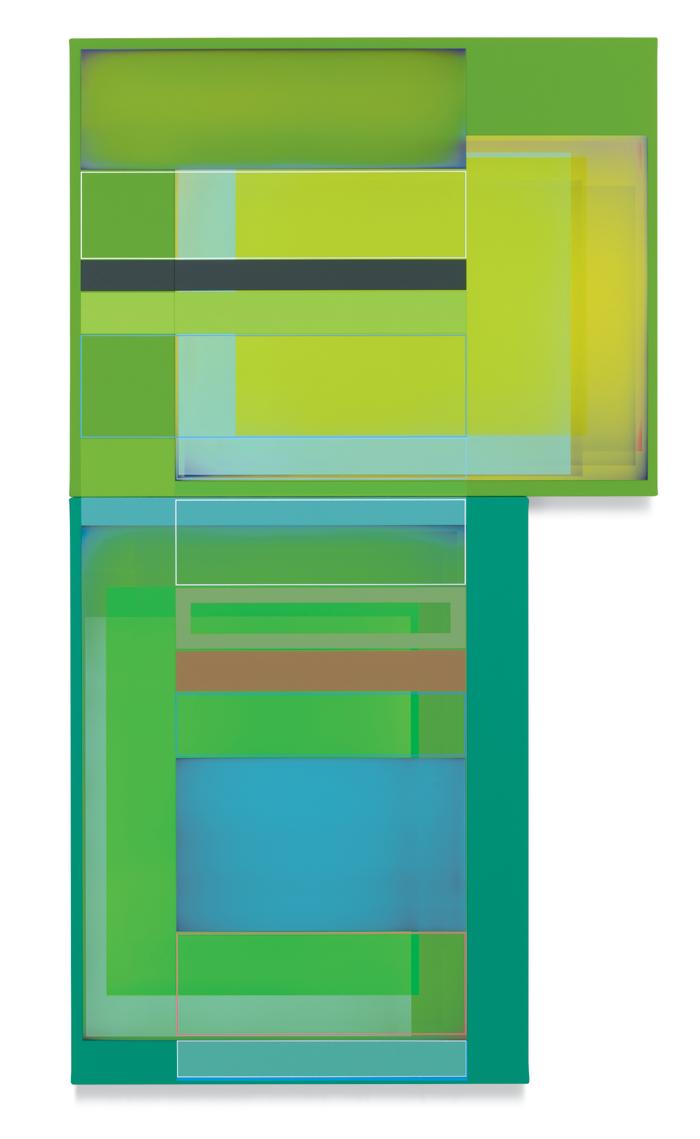

Verde Sauce, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

48 x 27 inches

121.9 x 68.6 cm

December Smoke, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

23 x 54 inches

58.4 x 137.2 cm

From Below, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

58 x 39 inches

147.3 x 99.1 cm

Ice Fishing, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

54 x 23 inches

137.2 x 58.4 cm

Marching Band, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

39 x 66 inches

99.1 x 167.6 cm

PATRICK WILSON

Born in Redding, CA in 1970

Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA

EDUCATION

1995

MFA, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA

1993

BA, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2022

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2021

“Keeping Time,” Vielmetter Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

2019

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2018

Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

2017

Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2015

Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2014

“Evolving Geometries: Line, Form, and Color,” Center for the Arts at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA

“Steak Night,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

2012

“Patrick Wilson: Pull,” University Art Museum, California State University Long Beach, Long Beach, CA

“Slow Motion Action Painting,” Marx & Zavaterro, San Francisco, CA

“Color Space,” Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2011

“Good Barbeque,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

2010

“The View From My Deck,” Marx & Zavattero, San Francisco, CA

2009

“Slow Food,” Curator’s Office, Washington, D.C.

“Always For Pleasure,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

2008

“Considering Truth and Beauty,” Marx & Zavattero, San Francisco, CA

“Selections from the Suite for Mount Washington: New Works on Paper,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

2007

“Some Things I Like,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

2006

“The Chandler Paintings,” Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

“Hothouse Flowers,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

2005

“The Course of Empire,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

“Two-Fold: Patrick Wilson - Richard Wilson” (curated by David Pagel), Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA

“Patrick Wilson: West,” Fusebox, Washington, D.C.

2004

“New Paintings,” Brian Gross Gallery, San Francisco, CA

“Oil Fields” (with Stefanie Schneider), Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

2003

“1:00pm,” Fusebox, Washington, D.C.

2002

“L.A.,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA

Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

2001

Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA

2000

Stefan Stux Gallery, New York, NY

Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

1999

Ruth Bachofner Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

Stefan Stux Gallery, New York, NY

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2021

“FROM THE COLLECTION OF ANONYMOUS,” North Dakota Museum of Art, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND

“Break + Bleed,” San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

2020

“20 Years: Anniversary Exhibition,” Vielmetter Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

“Do You Think It Needs A Cloud?,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“20 Years,” Vielmetter Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

2019

“The Responsive Eye Revisited: Then, Now, And In-Between” (curated by David Pagel), Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2018

“Michael Reafsnyder & Patrick Wilson,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“Belief in Giants,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2017

“Pivotal: Highlights from the Collection,” Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA

“On the Road: American Abstraction,” David Klein Gallery, Detroit, MI

2016

“Geometrix: Line, Form, Subversion,” Curator’s Office, Washington, D.C.

2014

“NOW-ISM: Abstraction Today,” Pizzuti Collection, Columbus, OH

2013

“California Visual Music – Three Generations of Abstraction” (curated by Marcus Herse and David Michael Lee), Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University, Orange, CA

2012

“Local Color,” San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

2011

“Sea Change: The 10th Anniversary Exhibition,” Marx & Zavaterro, San Francisco, CA

2010

“California Biennial” (curated by Sarah Bancroft), Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA

“Inaugural Group Exhibition,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

“Summer Selections,” Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

“Tomorrow’s Legacies: Gifts Celebrating the Next 125 Years,”

Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

“Abstractive Measures,” Arena 1 Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2009

“Broodwork,” Center for the Arts Eagle Rock, Los Angeles, CA

“Electric Mud” (curated by David Pagel), Blaffer Gallery, University of Houston, Houston, TX

“Summer ‘09,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

2008

“iCandy: Current Abstraction in Southern California” (curated by Carl Berg), Cypress College Art Gallery, Cypress, CA

“Swim,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

2007

“Keeping it Straight: Right Angles and Hard Edges in Contemporary Southern California Art” (curated by Peter Frank), Riverside Art Museum, Riverside, CA

“Liquid Light,” DBA 256 Gallery, Pomona, CA

2006

“Claremont Connections: Selections from the Permanent Collection,” Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, CA

“Abstraction,” Mulry Fine Art, West Palm Beach, FL

2005

“Into the Light,” Scape Gallery, Corona Del Mar, CA

“Fabulous,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

“Gyroscope,” Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

2004

“New,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

“A War Like People” (curated by Laura Taubman), Shade Projects, Scottsdale, AZ

“Tremelo” (curated by Dion Johnson), Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

2003

“Place,” Harris Art Gallery, University of La Verne, La Verne, CA

“Unstable,” Fusebox, Washington, D.C.

2002

“Chromophilia,” Fusebox, Washington, D.C.

2001

“Heat,” Margaret Thatcher Projects, New York, NY

“New Work: LA Painting,” Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco, CA

“The Permanent Collection: 1970-2001,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

“Monochrome/Monochrome?” (curated by Lilly Wei), Florence Lynch Gallery, New York, NY

2000

“Cool Painting 2000,” Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

“Maximal/Minimal,” Feigen Contemporary, New York, NY

“2000 Anos Luz,” Instituto Óscar Domínguez de Arte y Cultura

Contemporánea, Tenerife, Spain

1998

“Cool Painting,” Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

“Four: Painting in the Abstract,” The Living Room, San Francisco, CA

“Transcendence, An Exhibition Celebrating Works of Irish and Irish American Artists,” Mount San Antonio College, Walnut, CA

1997

“Generational Abstractions,” Ruth Bachofner Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“L.A. Emerging,” Marcia Wood Gallery, Atlanta, GA

1996

“Drawn Conclusion, Southern California Drawing,” Riverside Art Museum, Riverside, CA

“California Focus: Selections from the Collection of the Long Beach Museum,” Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, CA

“Time Splits Open: Fifteen Narratives,” Marcia Wood Gallery, Atlanta, GA

1994

“Next,” California State University, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

SELECT COLLECTIONS

Achenbach Collection, Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA

Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, OH

Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

Elmhurst Art Museum, Elmhurst, IL

Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, MN

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, CA

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

Minnesota Museum of American Art, Saint Paul, MN

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

North Dakota Museum of Art, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND

Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA

Pizzuti Collection, Columbus, OH

Phyllis and Ross Escalette Permanent Collection of Art, Chapman University, Orange, CA

San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

University Art Museum, California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, CA

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

PATRICK WILSON

28 April – 4 June 2022

Miles McEnery Gallery 515 West 22nd Street

New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2022 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved Essay © 2021 Dan Cameron

Director of Publications

Anastasija Jevtovic, New York, NY

Photography by Robert Wedemeyer, Los Angeles, CA Christopher Burke Studio, Los Angeles, CA

Color separations by Echelon, Santa Monica, CA

Catalogue designed by McCall Associates, New York, NY

ISBN: 978-1-949327-72-4

Cover: Much Later, (detail), 2021