Bridget R. Cooks

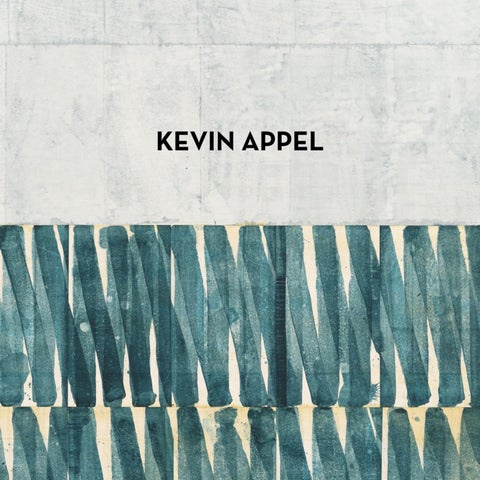

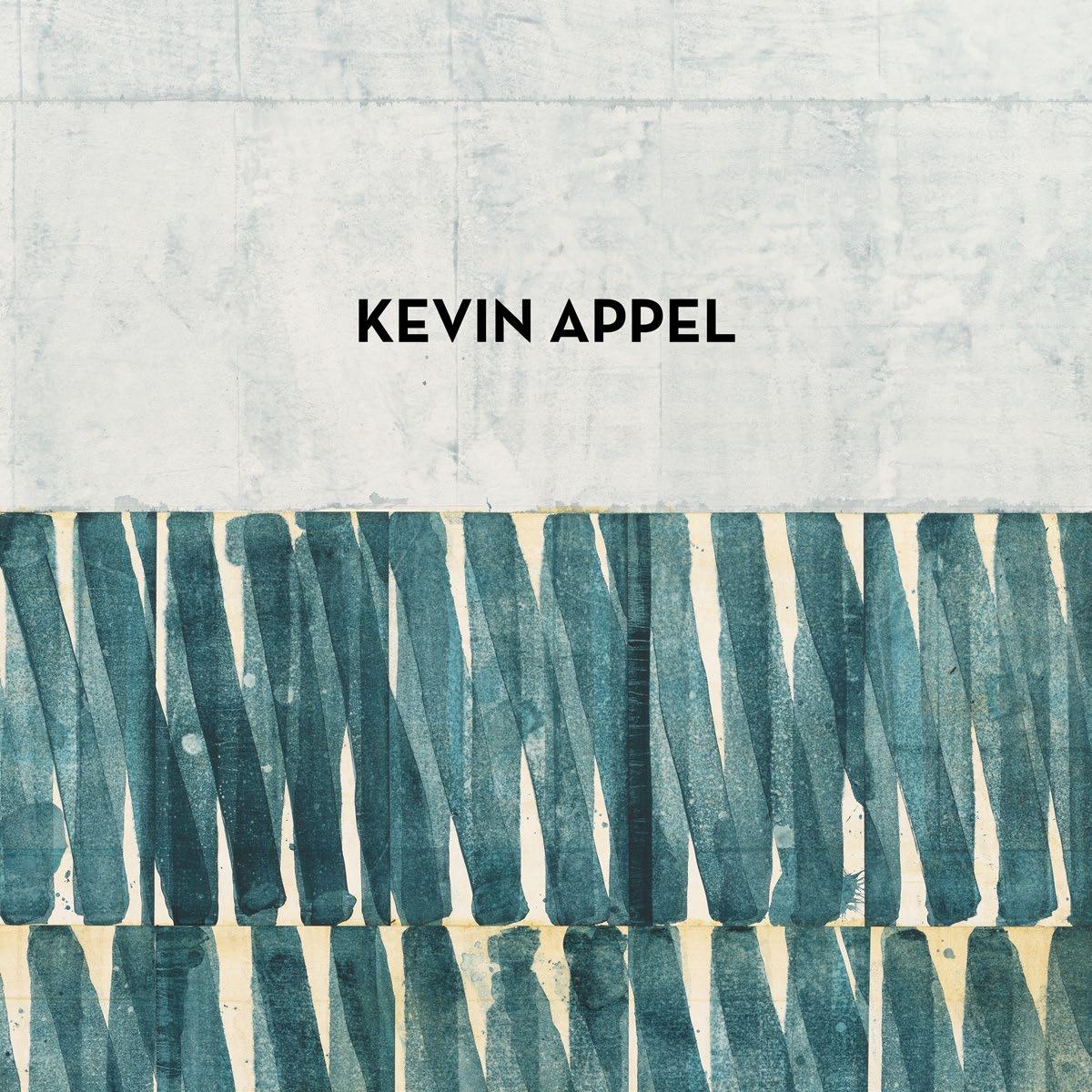

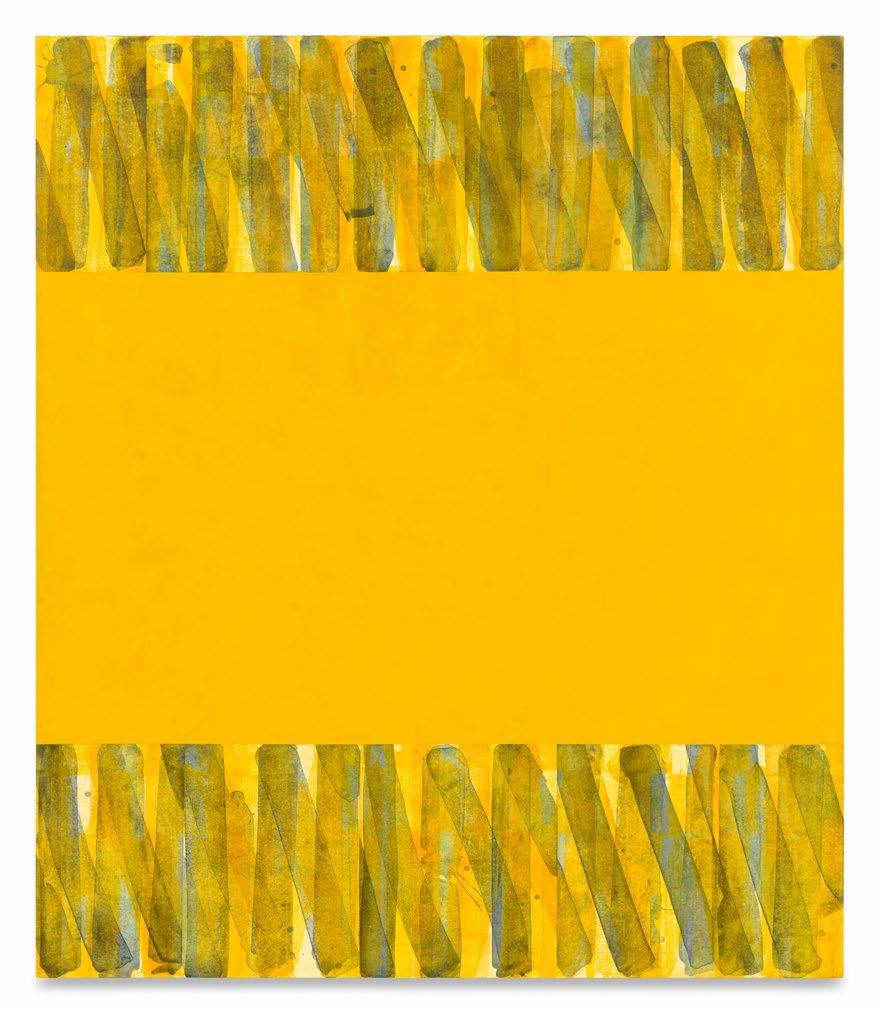

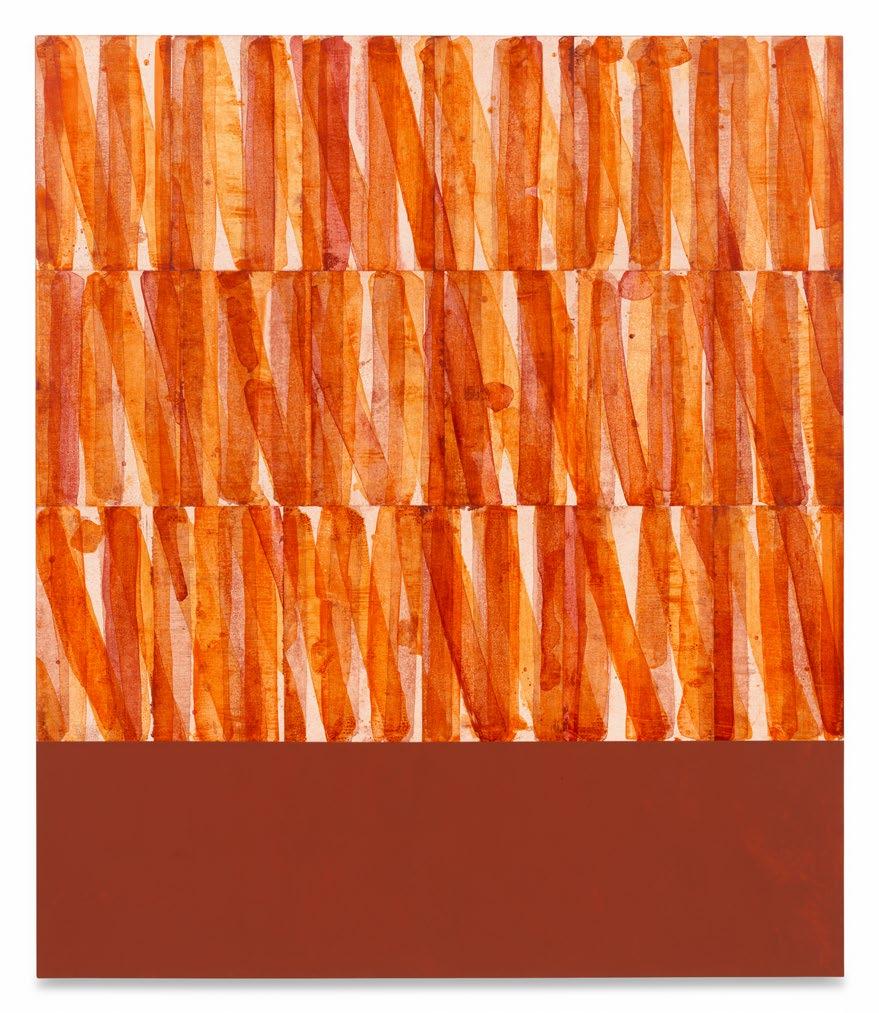

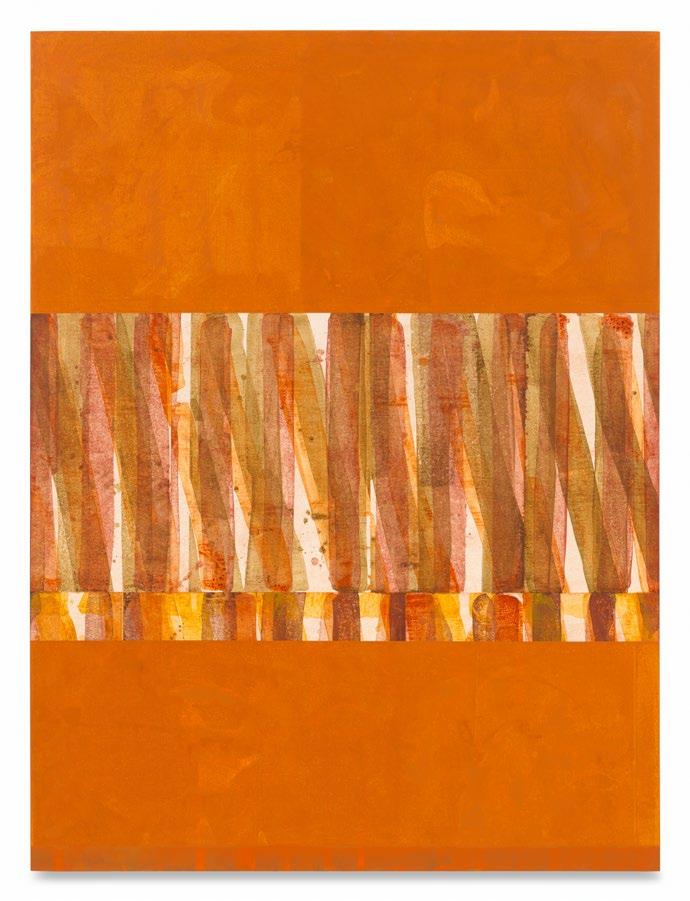

In his latest exhibition, Intervals, Kevin Appel presents a suite of twelve contemplative large-scale paintings and nine watercolors. Each work is organized into bands of opaque colors and rhythmic line arrangements. The varied registers of the paintings oscillate between motion and stillness, and their visual play compels viewers to engage in a conversation about temporality and change. Appel’s affective color palette ranges from reserved pastels to jewel tones. The color combinations, selected with intention, create distinct moods and encourage communion.

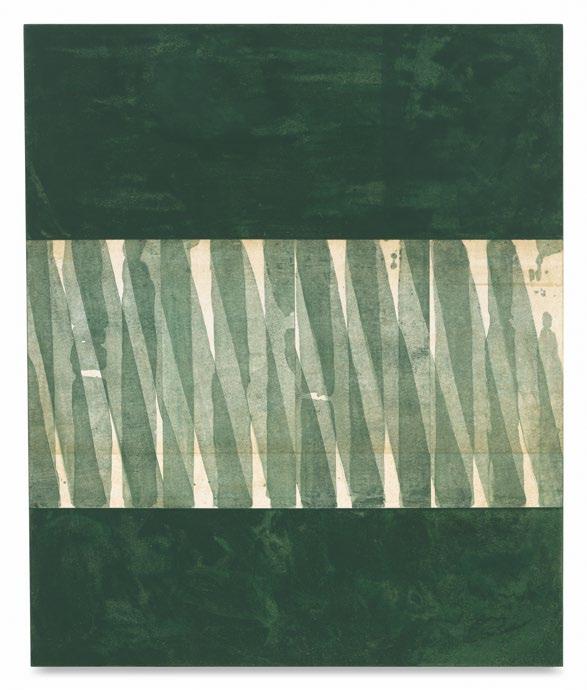

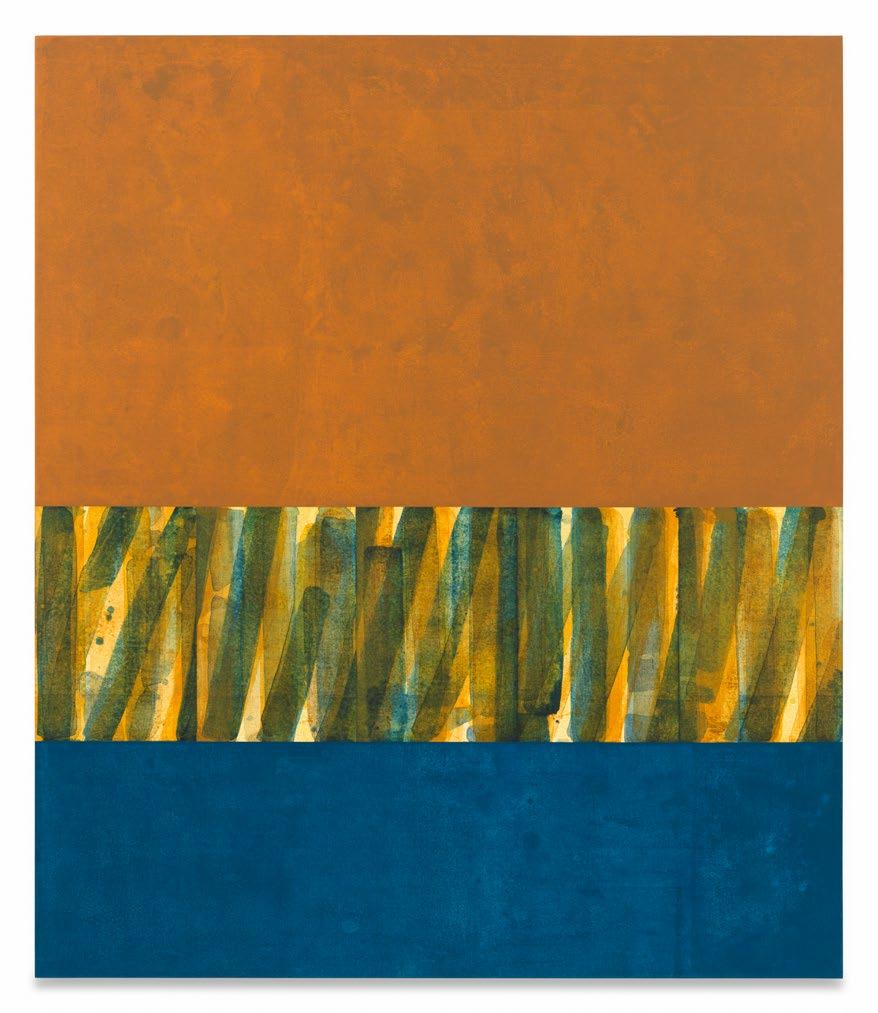

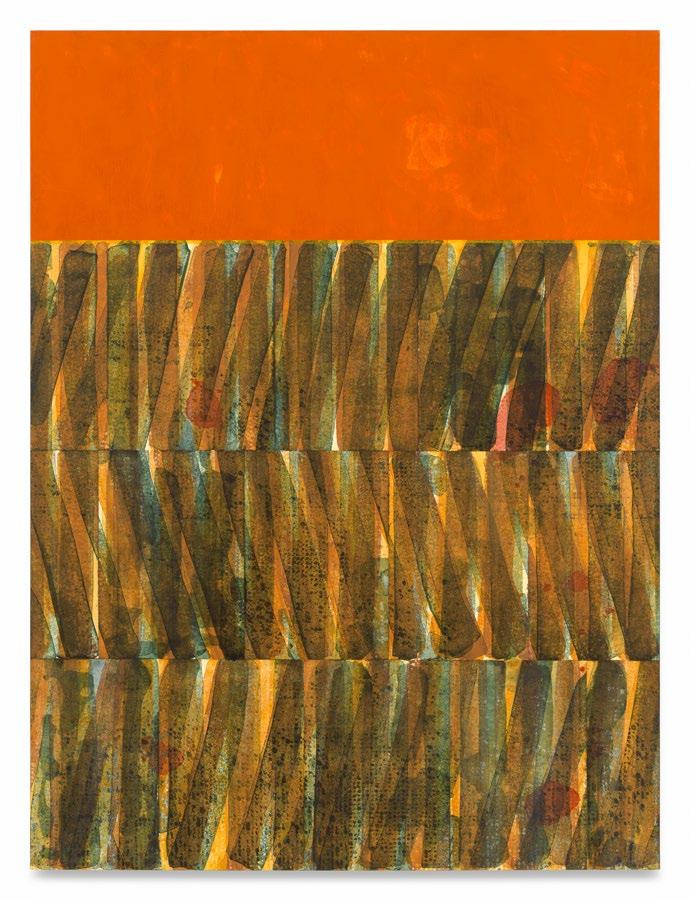

Since his 2023 exhibition at Miles McEnery Gallery, Appel’s paintings have pivoted from intricate, densely patterned surfaces toward an airier treatment of color and line. Although he maintains his interest in the grid as a basis for organization, the paintings have become more open. He explores the defining organizational system through a sophisticated and restrained choice of colors. In some of the paintings, the patterned area recedes while the variation of a single color comes forward. For example, Untitled (3 Bands Sienna/Indanthrone) (2025) is structured into a block of sienna and a block of blue, with a restless strata of loose yellow, blue, and green lines standing between them. The weighty sienna bar drops down below eye level from the painting’s top edge. It hangs like a curtain over the colorful lines that perform on the supportive blue stage below. The walls of sienna and blue close in on the flurry of stains and casual drips that keep the two colors apart. Viewers seem to catch a last glimpse of the painting’s vibrating interior.

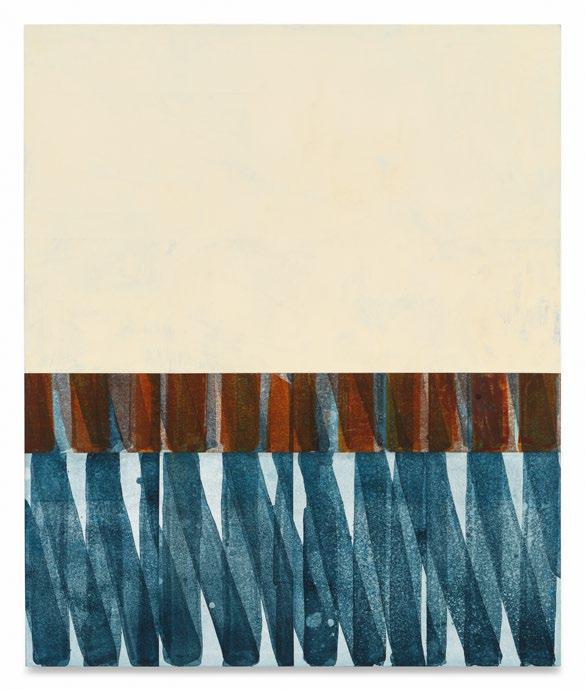

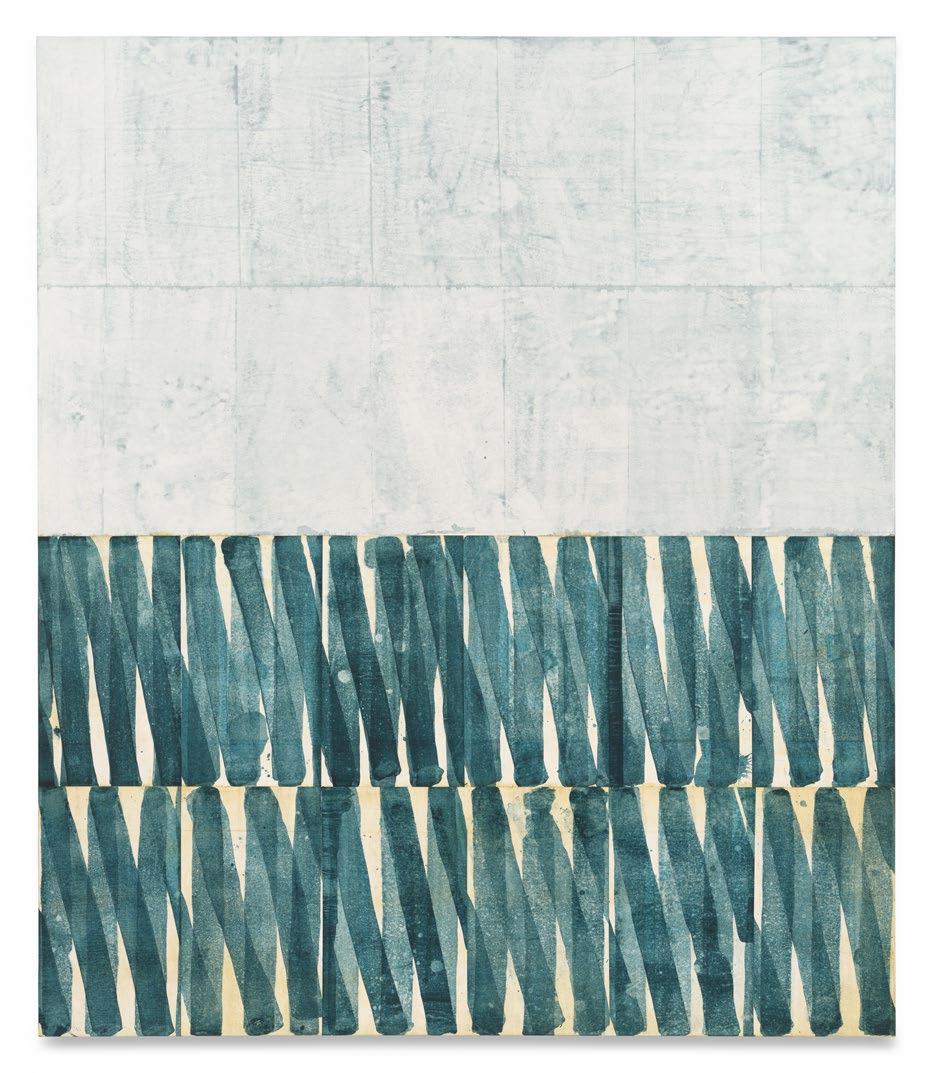

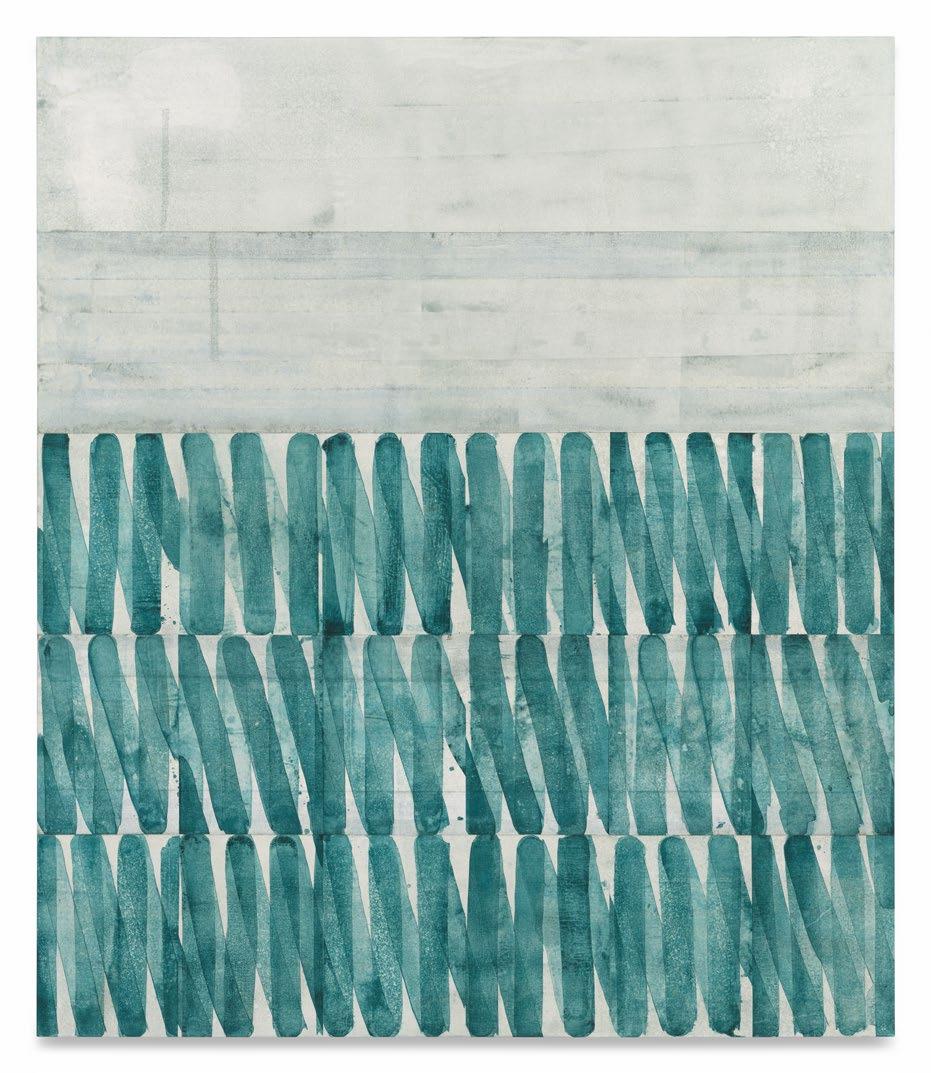

In other paintings, the linear design advances toward the viewer while the delimited monochromatic wash presents the illusion of an endless horizon. In Untitled (5 Bands Mineral Wash) (2025), the top two registers are structured into long strips of pale grayish blue. The pools and streaks of the milky variegated pigment hover like a heavy sky. On the left side, two drips of blue echo one another like a

pillar with its shadow or a watery reflection. These bands of blue provide just enough information to suggest a landscape. They take viewers deep into the painting, breaking through the surface into another dimension. The painting’s three bottom registers are patterns of alternating vertical and slanted blue lines that dance across the canvas like a tight coil of cord. The forms appear to move from left to right, and the viewer reads them like writing. Although the marks are made from repetitive gestures, each stroke is a unique combination of translucent paint layers that texture the surface like ceramic glaze. Like clay, the surfaces want to be touched. In turn, viewers want to find out if what reads as texture is haptic or is a smooth impression on a polished surface. To experience the entire painting, viewers must focus on the lines that claim the shallow surface of the picture plane and then refocus to see beyond the painting’s skin into open space. The contrast between the strokes that travel across the surface in the registers below and the illusion of depth in the misty bands above is a negotiation that the viewer both witnesses and enables.

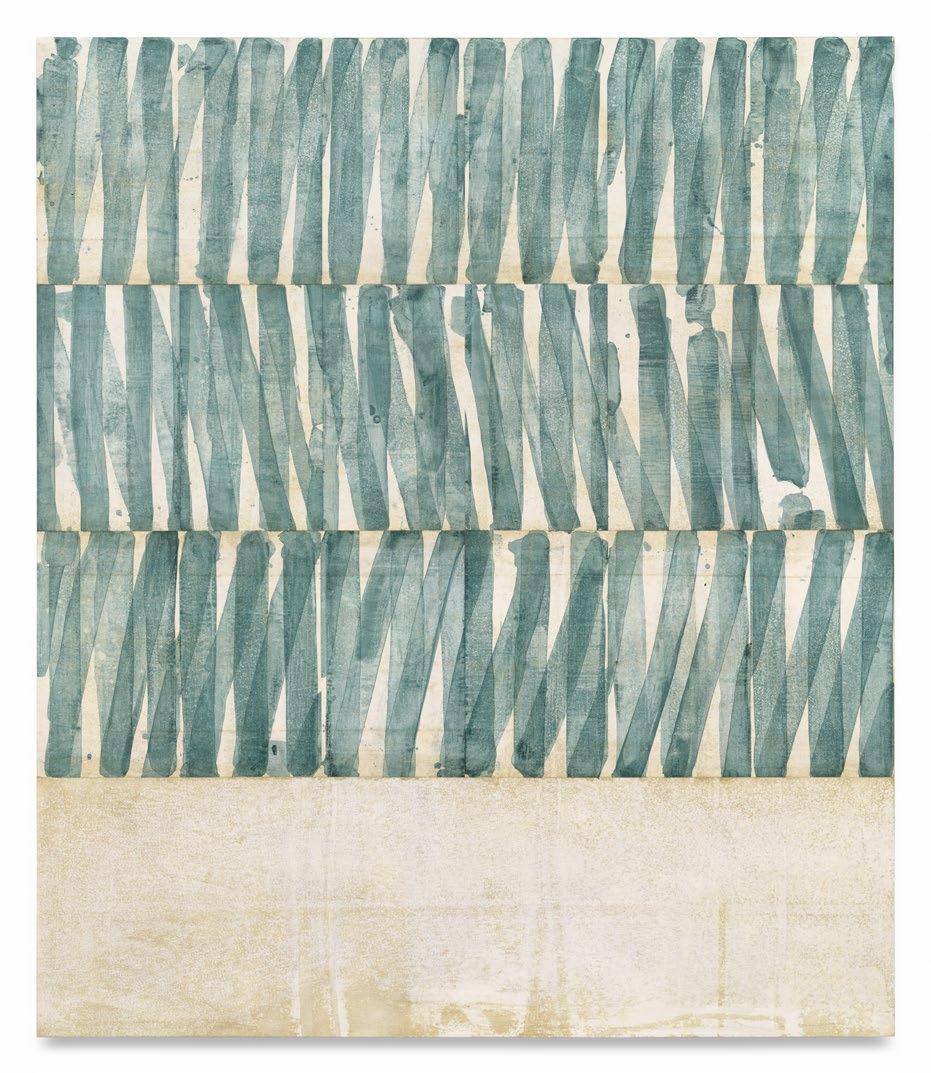

Untitled (4 Bands Blue Salt) (2025) is a blue and gray counterpart to Untitled (5 Bands Mineral Wash) The bottom register is imprinted with textures that give it the palimpsest appearance of an exterior wall. Its horizontal and vertical lines mimic building blocks that form a foundation for the structure of the painting. The slanted blue marks worked into the registers above move in alternating directions that give the painting a rhythm and hum. Viewers may imagine the combination of vision and sound as a kind of calligraphic sheet music. Regular measures are marked by the subtle breaks on the surface that organize the linear gestures into sections.

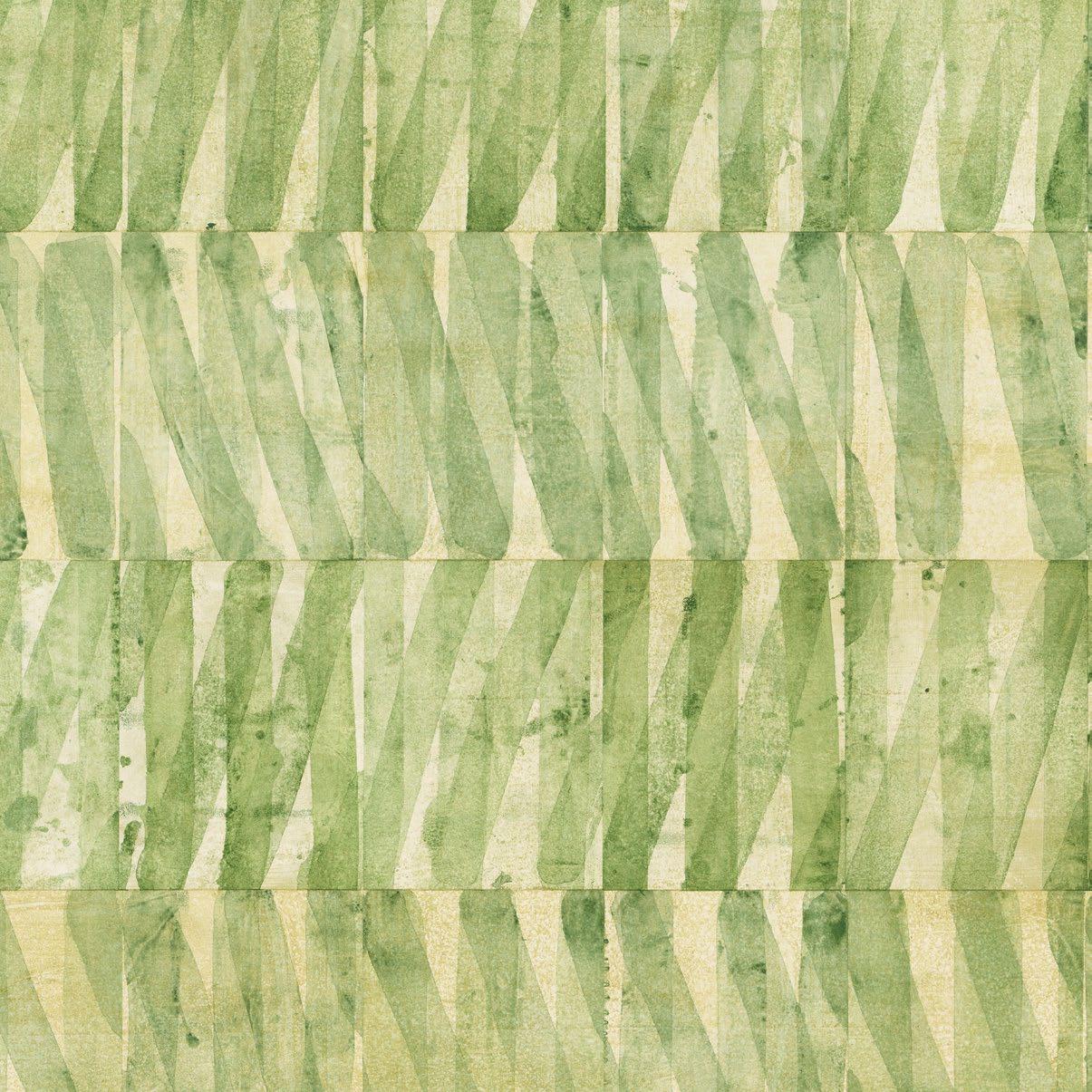

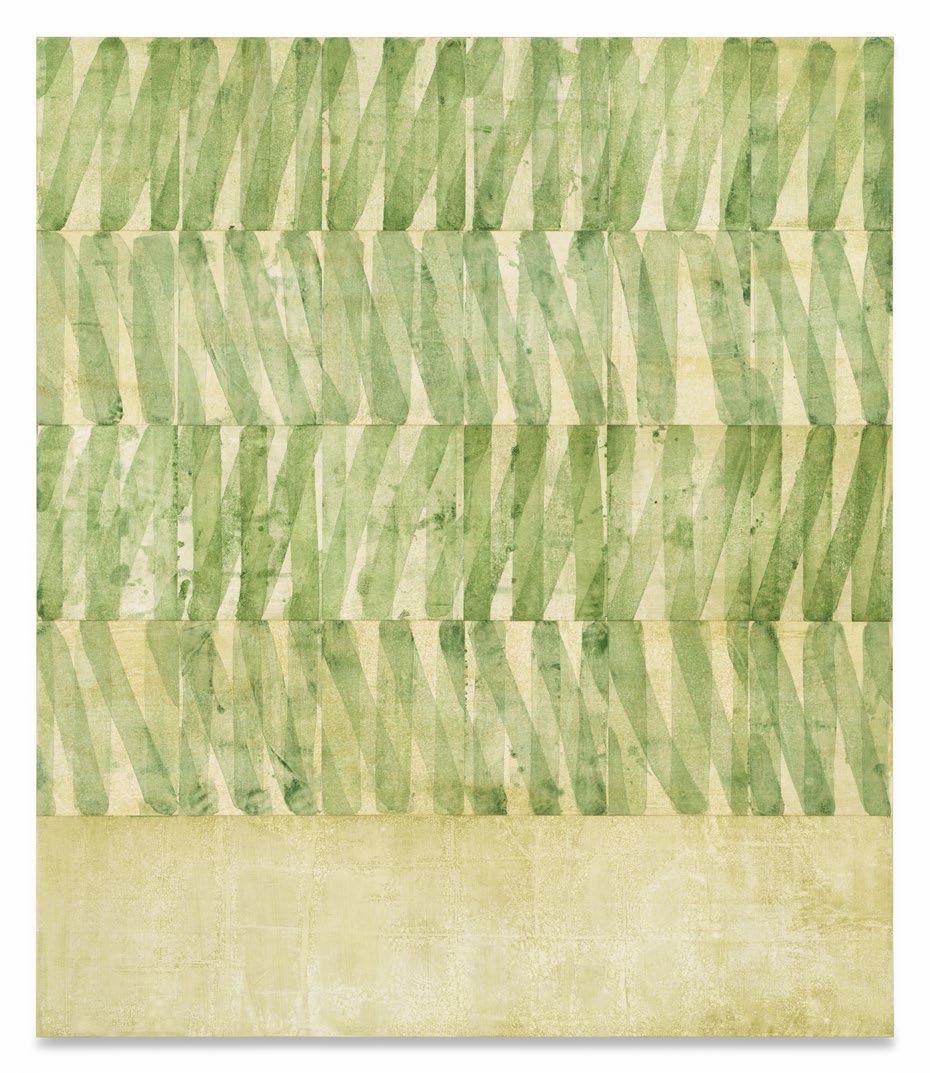

Appel takes cues from organic colors that occur in nature. Perhaps this is most apparent in Untitled (5 Bands Terre Verte) (2025). The tranquil tints of green suggest the new growth of spring. Its four layers of lines punctuate the canvas with movement. The lichen-green of the painting’s lowest expanse evokes a softness echoed in its worn surface. Here, Appel prepares a place for the eye to wander in the subtle changes of color.

Appel’s selection of watercolors displays the artist’s deference to materials, faith in experimentation, and play within a determined space. Born from this protocol, each composition demonstrates

creative, seemingly endless color-filled variations of geometric abstraction. The works on paper, different in size, scale, and medium, have a relationship to the paintings, but they also stand as serious works in their own right. Made intuitively and with immediacy, Appel’s saturated surfaces appear as sketches—expressions of the artist’s curiosity about the limits of the materials. The paintings are made at a different tempo. Their collisions of brushstrokes are permanently recorded on the surface. They require a deliberate methodical approach with an eye toward the completed picture. Appel’s work in both media maintains an organic quality from the fluidity of its making that actively resonates long after the paintings have dried. Ultimately, this group of warm and cool paintings invites viewers to experience a spectrum of fresh rifts on color, form, and structure.

Bridget R. Cooks, PhD is Chancellor’s Fellow and Professor of African American Studies and Art History at the University of California, Irvine.

October 20, 2025

BRIDGET R. COOKS: Thank you for inviting me to your studio and agreeing to a conversation about your new work!

KEVIN APPEL: It’s an honor to have you here.

BRC: Would you please describe your ritual process for creating these paintings? Would you also speak about the discipline of painting and how that informs the final work?

KA: Ah yes, rituals. Important. In the morning, I usually meditate or exercise early. Yes, there’s dog walking—something to prime the pump. Then I take a second coffee downstairs to the studio and sit with the work for a while before touching anything. I like that quiet moment of looking. I love mornings—that time when the day still feels endless. The studio has great light in the morning. It changes a lot through the day— getting more golden as the day moves on.

It’s interesting that you ask about discipline,

because it’s been on my mind lately. The work is shifting, and right now it feels crucial that I don’t have an end result in mind. There’s always some image hovering, but holding onto it can cloud the process. So lately it’s been more about being present and disciplined in the process. Doing the thing I’m doing, when I’m doing it.

That sense of presence carries into the physical rhythm of these paintings—applying a layer, waiting for it to settle, sometimes covering it, sometimes letting elements show through. But a change is that even the covering-up is transparent now. The medium has shifted, so the paintings are less forgiving and more direct. Every mark is evident, even when I redact it. You can see the thinking—the hesitation, the revision.

So the surface really does record time. It’s a kind of slow accumulation, but through transparency rather than weight. And working this way has let me get to a more immediate, less distanced way of painting—to stay in flow. For now, anyway.

BRC: Would you say more about your shift in media for these new works?

KA: Sure. I’m working with pigment dispersion. Basically, a pure liquid pigment, and I mix in different binders depending on how dense or open I want the layer to feel. The binder shifts the body of the paint, how it settles, how much light it holds. It’s a very immediate material. There isn’t a lot of hiding with it.

I’m also doing a lot to unsettle the surface before it dries. Wiping, spraying, lifting, sometimes just letting gravity move things around. The paint stays active only briefly, so the timing becomes part of the process. Partially because of this, I work in smaller modules that build to a grid-like structure.

It’s changed how I work. The material demands a kind of responsiveness. It pushes back, it misbehaves. That unpredictability is what gives the surface its life. I come in with oil at the end of the works—the oil layers tend to get a similar amount of disturbance before they are dry.

BRC: What ideas inspire you to paint?

KA: That’s a tough one because the ideas shift

all the time. I’m a bit restless by nature. I think what keeps me painting is the not knowing. That the act itself will draw something unexpected in. I’m drawn to the moment when a painting begins to undo the structure that held it together or the idea that began the process.

BRC: Which components of your visual language do you return to, day after day? What repeats?

KA: There are things I keep returning to. Walls, textures, framing devices, architectonic hints, screens, textiles, grids, thresholds, strata, landscape, and structure. But lately, those structures are starting to dissolve. I’m less interested in holding the image in place and more in letting it breathe, letting the geometry fall apart a little. The work feels like it’s moving toward something more porous, less resolved. Breath is important to these, literally and metaphorically.

BRC: Which elements are consistently generative and bottomless? What is the chase?

KA: Color is another chase. I never quite know what it’s going to do until it’s there. I’m after a kind of temperature or hum that’s not descriptive but felt—a vibration between clarity and

murk. There also quite often needs to be a collision in the work. A redaction, a covering, and edge to come up against—or a foundation for something lighter or more agitated to sit on or lean on. Something perhaps a bit more robust in its opposition or counterbalance.

So if there’s a big idea behind all this, it’s probably the act itself. The back and forth between control and release, image and material, knowing and not knowing. Between direct and indirect application. Immediate and tempered mark. That’s what keeps me coming back every day. It’s never settled.

BRC: What is the role of improvisation in your work? How much of the painting is planned before you make the first mark?

KA: That’s interesting, because right now very little is really planned. That wasn’t always the case. In earlier bodies of work, I needed to be more deliberate. To think about how two patterns might interact, to test or lay something out first. To measure for screens. But with these new paintings, I’ve let go of that kind of mapping.

But it’s not free association; there’s still a structure to how things begin. I start with a rhythm

of gestures, a loose grid that anchors the surface. It’s almost like a warm-up or a pattern of physical movement, a way to locate myself in the painting. From there, everything is built on response. To color, to density, to the surface.

Something that has stayed consistent is a tendency to work blind or semi-blind. That was always the case with screening in the last body. You can’t see it while doing it. In these, it’s less so, but I am working flat and in modulated sections, so there isn’t a sense that I can take in the whole thing until I prop the work back up and see what I’ve done.

The shift really started when I began repeating a form from an earlier watercolor series, but on a larger scale. The pattern itself came from thinking about facades—architectural screens, or brise soleil. That repetition opened the paintings; it gave me a familiar point of entry but allowed the rest to unfold in real time. So now, the improvisation is the structure.

BRC: You were an inaugural artist-in-residence at the Clyfford Still Museum in 2024. Did what you saw in Still’s work influence your approach to painting for this new body of work?

KA: The Still residency was important. I already had a deep connection to his work. One of my earliest art memories is of seeing a room of Still paintings at the old SFMOMA and having a rather transformative experience. There was something so severe, so believed, and also somehow ethical that came through. It wasn’t just about form or gesture; it was about conviction, about painting as a way of being in the world. I was little, 9 maybe. I’m not saying I understood this at that age—but I felt something, and it stuck with me.

When I went to Denver for the residency, I arrived thinking I was going to do my thing. And I brought tools to do that thing. The things you bring when you think you’ll just continue your practice somewhere else. I drove there, and that was the first change—the landscape I took in along the way. And after living with Still’s work, especially his works on paper, I let my plans go. I started working in watercolor for the first time in a long while.

The watercolors I worked on there were brain on paper—immediate, direct, unfiltered. They allowed me to see how discipline and source material could coexist with freedom and experimentation. The residency gave me permission

to strip things down and start again. This new body of work really comes out of that moment— that sense of immersion, of letting the work lead instead of the plan. The clarity and commitment I felt in Still’s paintings—that deep presence—still anchors how I’m working now. Although my practice involves interference—perhaps in a way that his didn’t.

BRC: For me, the relationship between the watercolor paintings on paper and the large canvases shows your exploration of scale, rhythm, and repetition. What do you discover in the watercolor works that you want to develop further on canvas? How would you describe the experience of translation, a repetition with a difference? What is worth repeating?

KA: Well, they’re wet. [laughs] Sometimes I feel more like a mason than a painter—working with cement. The water changes everything. It’s looser, more transparent, more unstable. There’s no hiding in watercolor. I feel a bit naked working that way.

On paper, everything happens fast—there’s no time to overthink. The rhythm becomes instinctual, and the patterning is more direct. That immediacy is what I’ve been trying to carry

into the larger canvases. The scale slows things down, of course, but I want to keep that same sense of fluidity, of the painting arriving before I can name it.

There’s still some screening, some opacity, and revealing that happens as well, but the initial moves—the patterns, the rhythms—are much more immediate now. So the repetition between watercolor and canvas isn’t really about copying a form. It’s about translating that wet, unstable openness into something bigger, denser, and slower. The watercolors often have a force working against that openness. An opacity. An opposition. The paintings contain a similar point of resistance.

BRC: There’s something here that I want to bring out. I would think that the watercolors have an openness that is about translucency of the materials. Could you say more about how you think about openness in terms of pigment and pattern?

KA: For me, the openness in the watercolors isn’t just about translucency, although that’s part of it. It’s also about the repeated mark, the looseness of the gesture, the way the marks don’t lock into a structure right away. There’s a

kind of unstable release there. Things remain somewhat unanchored in that watercolor is fugitive; it lifts back up if it’s made wet again.

But even in the watercolors, there’s often a counterforce. The repeated stroke starts to build a kind of architecture. A blocking or a rhythm that pushes back against all that openness. Then there are actual areas of opacity that come up against the translucent marks, like a conversation. Maybe not quite an adversary. That tension interests me.

When I move into the larger paintings, I’m basically translating that conversation into something bigger, slower—filling the field of vision. The paintings are where the opposition becomes more explicit. The large fields of color, or the large areas of exposed ground—the pressure of those planes against the looseness of the repeated marks.

The watercolors hold it more lightly, while the paintings give it weight.

BRC: Do you think about the viewer when you make the work or even after it is completed?

KA: I try not to. Honestly, I think most painters

are painting for other painters—or maybe for painting. It’s not that I don’t care about the viewer, but if I start thinking too much about how the work should be received, I lose the thread.

BRC: What experience do you want to give the viewer?

KA: If there’s an experience I hope for, it’s one of shifting distances: the brick in the face of the long view, the wonder of the mid-view, and the analysis of the close-up. I want the work to hold at all those distances, to draw the viewer in and then disorient them a bit, to let the eye wander and find its own footing.

Ideally, the viewer feels like they’re inside a kind of constructed space—not exactly architectural, but built. The painting should feel occupied, like it has its own gravity and air. The aggregated impact often points to a structure felt but unnamed —an old wall, a brutalist mosaic, a bruised surface—not a picture, but a suggestion. When it becomes too much of a picture, it’s failed for me. Something that stays out of reach. I’m not interested in reading.

Painting, for me, is a kind of offering. A way of giving shape to pleasure and attention. A

moment of clarity or connection that reaches beyond myself. When it’s working, the painting holds a real feeling, something steady and human in the middle of everything else. If the work can give someone a little space, a bit of recognition or resonance in the face of the world as it is, then I feel like it’s doing its job.

BRC: Your previous paintings, particularly the ones in your 2023 exhibition at Miles McEnery Gallery, are provocative in their dense patterns, layers, and restrained palette. They challenge viewers to linger and figure out how the paintings are made. They also make viewers aware that some areas of the compositions are deliberately hidden while others want to be seen. The works in this exhibition have become less dense. Could you talk about this shift in your work and what you want viewers to discover now?

KA: There’s variable density in these paintings; it comes through transparency now instead of weightiness or aggregated pattern. In the last show, things were built up in layers—dense, patterned, also kind of withholding. You could feel the labor and the control. With this new work, I wanted to let a little more air in.

I’ve been thinking about Colin Rowe’s idea of literal versus phenomenal transparency. The difference between something that’s physically see-through and something that just feels transparent, where layers and forms overlap in a way that suggests depth and movement. You see that in cubism for instance. That suggested depth is closer to what I’m after. It’s not about revealing what’s underneath but about how one gesture breathes through another, how space can be sensed rather than seen. Something about time is in all of this as well.

So yes, they might look less dense at first glance—some clearly are. There are a few paintings in this group that are a single layer over a ground. But the density is often still there—it’s just lighter, more optical. The top surface has become a place you can read through, not just look at. I want the viewer to feel that sense of openness—of things slipping in and out of view, always hovering between the seen and the sensed. And also, struck through with a sense of decay, of mold, of collapse, or a loss of structural integrity. The ruin … again, time …

48 x 40 inches

122 x 102 cm

70 x 60 inches

178 x 152 cm

dispersion, acrylic, and oil on linen over panel

48 x 40 inches

122 x 102 cm

Pigment dispersion, acrylic, and oil on linen over panel

70 x 60 inches

178 x 152 cm

dispersion and acrylic on linen over panel

64 x 48 inches

163 x 122 cm

dispersion and acrylic on linen over panel

77 x 66 inches

196 x 168 cm

dispersion and acrylic on linen over panel

77 x 66 inches

196 x 168 cm

77 x 66 inches

196 x 168 cm

dispersion, acrylic, and oil on linen over panel

64 x 48 inches

163 x 122 cm

70 x 60 inches

178 x 152 cm

(5 Bands Rust Interval), 2025

dispersion, acrylic, and oil on linen over panel

64 x 48 inches

163 x 122 cm

dispersion and acrylic on linen over panel

77 x 66 inches

196 x 168 cm

Born in 1967 in Los Angeles, CA

Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA

EDUCATION

1995

MFA, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

1990

BFA, Parsons School of Design, New York, NY

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2026

“Intervals,” McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2023

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2018

Miles McEnery Gallery at The Art Show, New York, NY

2017

“slip collapse then and,” Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2014 Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2013

Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2012

“Paintings,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA

2009

“Drawings,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

2008

The Suburban, Chicago, IL

Two Rooms Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

2007

Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY

2006

Wilkinson Gallery, London, United Kingdom

Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2004

Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY

2003

“Descripcion sin lugar: Una Seleccion de Obras de Kevin Appel,” Museo Rufino Tamayo, Mexico City, Mexico

2002

Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2001

Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY

1999

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

1998

Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2025

“Selections from the Collections,” Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, La Jolla, CA

2024

“All Bangers, All The Time: 25th Anniversary Exhibition,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“L.A. Story,” Hauser & Wirth, West Hollywood, CA

2018

“EVOLVER,” L.A. Louver, Los Angeles, CA

“Belief in Giants,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2016

“Instilled Life: The Art of the Domestic Object from the Permanent Collection of UCR Sweeney Art Gallery,” Sweeney Art Gallery, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA

2015

“BLACK/WHITE” (curated by Brian Alfred), Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

“Endless House: Intersections of Art and Architecture,”

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

“Transcendent Abstraction in Painting: Selections from the Permanent Collection of UCR Sweeney Art Gallery” (curated by Tyler Stallings), Sweeney Art Gallery, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA

“Kaleidoscope: abstraction in architecture,” Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

“XL: Large-Scale Paintings from the Permanent Collection,” Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY

2014

“BLACK/WHITE” (curated by Brian Alfred), LaMontagne Gallery, Boston, MA

2013

“The Ghost of Architecture: Recent and Promised Gifts,” Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

“Lovers” (curated by Martin Basher), Starkwhite Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

“The Symbolic Landscape: Pictures Beyond the Picturesque” (curated by Juli Carson), University Art Gallery, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA

“Paradox Maintenance Technicians,” Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA

“Los Angeles Nomadic Division ‘Painting in Place,’” Farmers and Merchants Bank, Los Angeles, CA

“Painting Two,” Two Rooms Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

2012

“Kevin Appel, Canon Hudson, Betsy Lin Seder,” Samuel Freeman Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2011

“LANY,” Peter Blum Gallery, New York, NY

“Beta Space: Kevin Appel and Ruben Ochoa,” San José Museum of Art, San José, CA

“Goldmine: Contemporary Works from the Collection of Sirje and Michael Gold,” University Art Museum, California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, CA

2010

“Small Paintings,” Two Rooms Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

“Haute,” Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art, Chaffey College, Rancho Cucamonga, CA

“FAX” (curated by João Ribas), Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA; traveled to Burnaby Art Gallery, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada

2008

“Works on Paper,” Two Rooms Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

2007

“Counterparts: Contemporary Painters and Their Influences,” Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art , Virginia Beach, VA

“The Last Show Cambridge Heath Road,” Wilkinson Gallery, London, United Kingdom

“Summer Stock,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2006

“L.A.: NOW,” Galerie Fiat, Paris, France

2005

“New Works on Paper,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

“California Modern,” Orange County Museum of Art, Costa Mesa, CA

2004

“ARTitecture,” Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA

“From House to Home: Picturing Domesticity,” Museum of Contemporary Art Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles, CA

“Seeing Other People,” Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY

2003

“Variance,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2002

“Drawing Now: Eight Propositions,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

“Trespassing: House X Artists,” Bellevue Art Museum, Bellevue, Washington; traveled to MAK Center, Los Angeles, CA

“New Economy Painting,” ACME, Los Angeles, CA

2001

“New to the Modern: Recent Acquisitions,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

“It’s a Wild Party and We’re Having a Great Time,” Paul Morris Gallery, New York, NY

“furor scribendi, Works on Paper,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

“Works on Paper,” Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland

“010101: Art in Technological Times,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA

“Against Design,” Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, La Jolla, CA

“Painting at the Edge of the World,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

“Next Wave Prints,” Elias Fine Art, Allston, MA

2000

“Do You Hear What We Hear?,” Paul Morris Gallery, New York, NY

“Painting Show,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland

“Drawing Spaces,” Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL

“2 x 2, Architectural Collaborations,” Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA

“Shifting Ground: Transformed Views of the American Landscape,” Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

“Against Design,” Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, PA

Palm Beach Institute of Contemporary Art, Lake Worth, FL

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO

“Architecture and Memory,” CRG New York, NY

1999

“Farve Volumen / Color Volume,” Kunstmuseum Brandts, Odense, Denmark

“Down to Earth,” Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY

“Drive-By: New Art from L.A.,” South London Gallery, London, United Kingdom

“The Perfect Life: Artifice in L.A. 1999,” Duke University Museum of Art, Durham, NC

“Local Color,” Harris Art Gallery, University of La Verne, La Verne, CA

“1999 Biennial,” Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA

“New Paintings from L.A.,” Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Switzerland

1998

“proof.positive.,” Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, CA

“Abstract Painting Once Removed,” Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Houston, TX

“Architecture and Inside,” Paul Morris Gallery, New York, NY

“Painting From Another Planet,” Deitch Projects, New York, NY

“Paintings Interested in the Ideas of Architecture and Design,” PØST, Los Angeles, CA

1997

“Inhabited Spaces: Artist Depictions,” Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, CA

“In Touch With…,” Galerie + Edition Renate Schröder, Cologne, Germany

“Kevin Appel, Francis Cape, Jorge Pardo,” Janice Guy Gallery, New York, NY

“Beau Geste,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

“Ten Los Angeles Artists,” Stephen Wirtz Gallery, San Francisco, CA

“Bastards of Modernity,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

1996

“Interiors,” Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA

AWARDS

2024

Fellow, Institute Residential Fellowship Program, Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO

2011

California Community Foundation Fellowship of Visual Artists, Los Angeles, CA

1999

Citibank Private Bank Emerging Artist Award, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

2023

Professor and Department Chair; Executive Director of University Art Galleries, Claire Trevor School of the Arts, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA

Fogg Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, La Jolla, CA

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

The New York Public Library, New York, NY

Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR

Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI

Saatchi Collection, London, United Kingdom

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

19 February – 28 March 2026

Miles McEnery Gallery 515 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2026 Miles McEnery Gallery All rights reserved

Essay © 2026 Bridget R. Cooks

Associate Director

Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Christopher Burke Studios, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-6117-7

Cover: Untitled (4 Bands Midnight), (detail), 2025