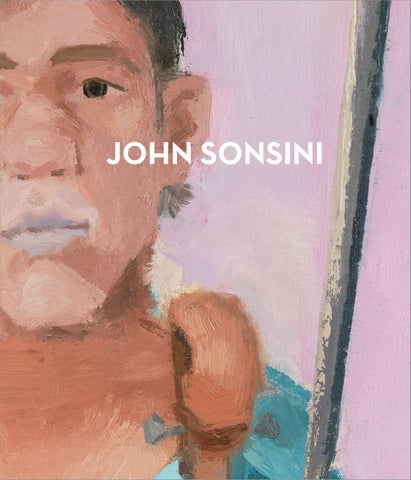

JOHN SONSINI

JOHN SONSINI

EMPATHY

By David Pagel

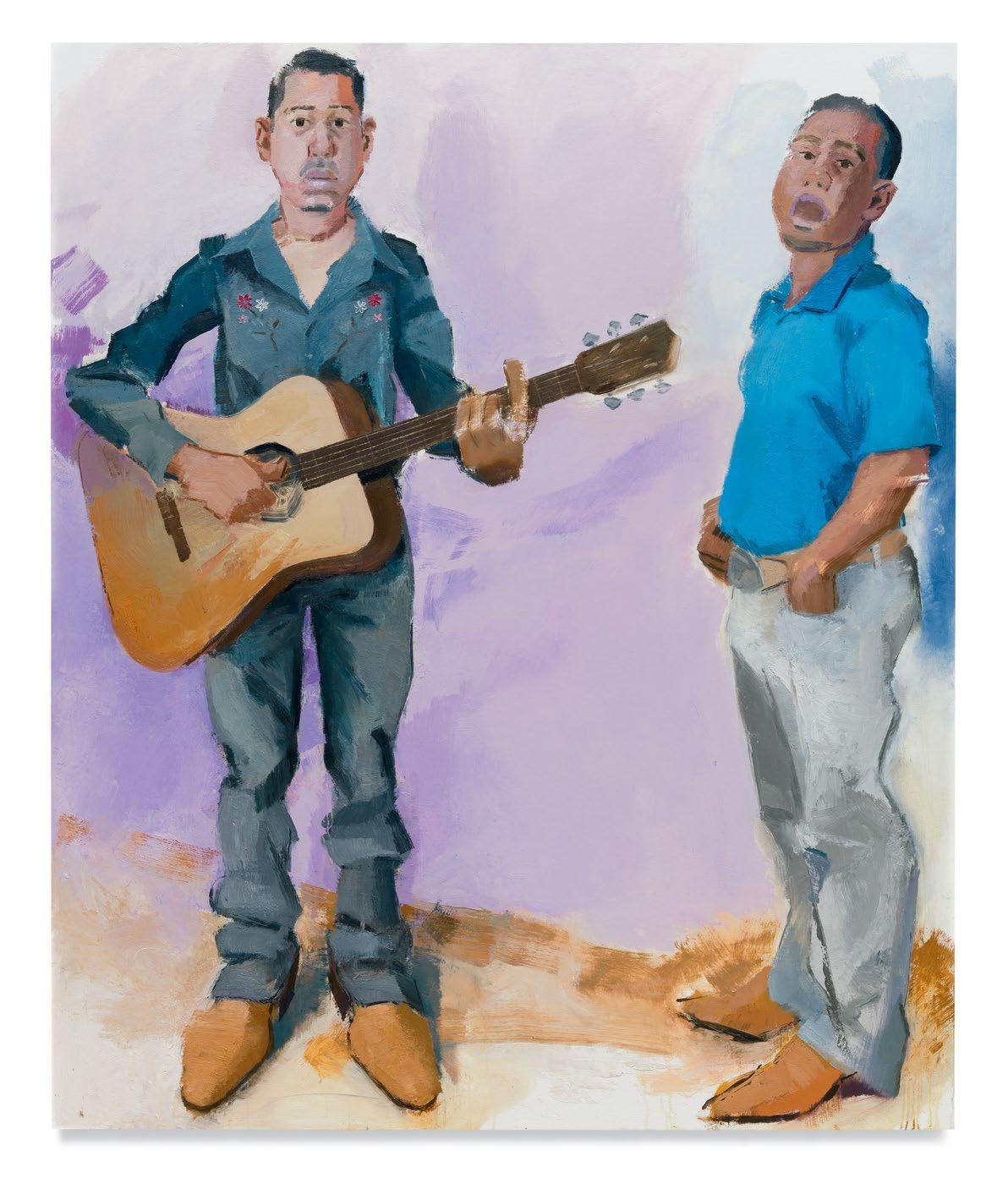

John Sonsini’s new works fall into four groups: 1.) paintings made from life, 2.) paintings made from memory, 3.) paintings made from watercolors, and 4.) paintings made from tableaux vivant—their live models posed to duplicate, in three dimensions, the compositions of watercolors Sonsini had painted before the pandemic began.

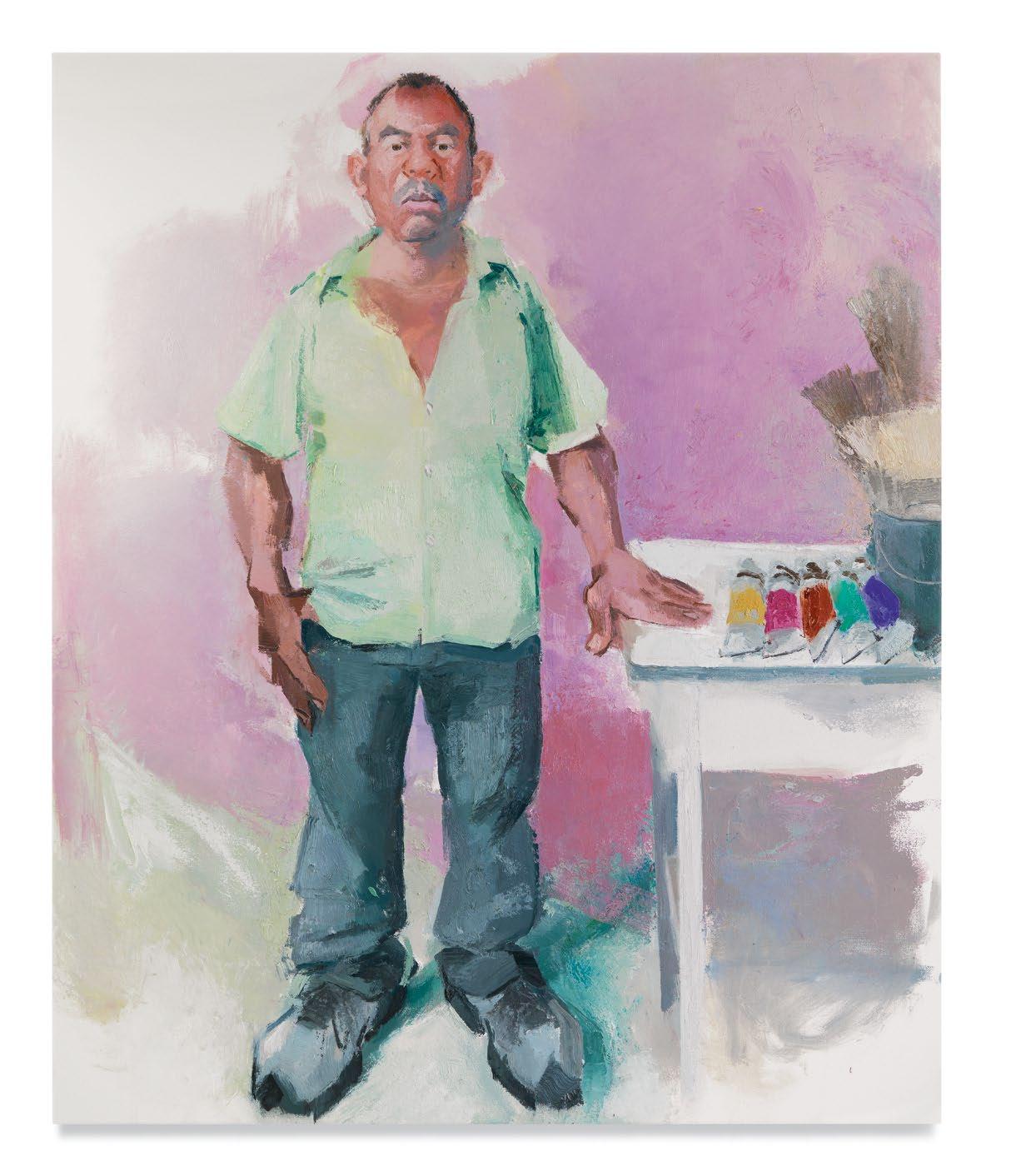

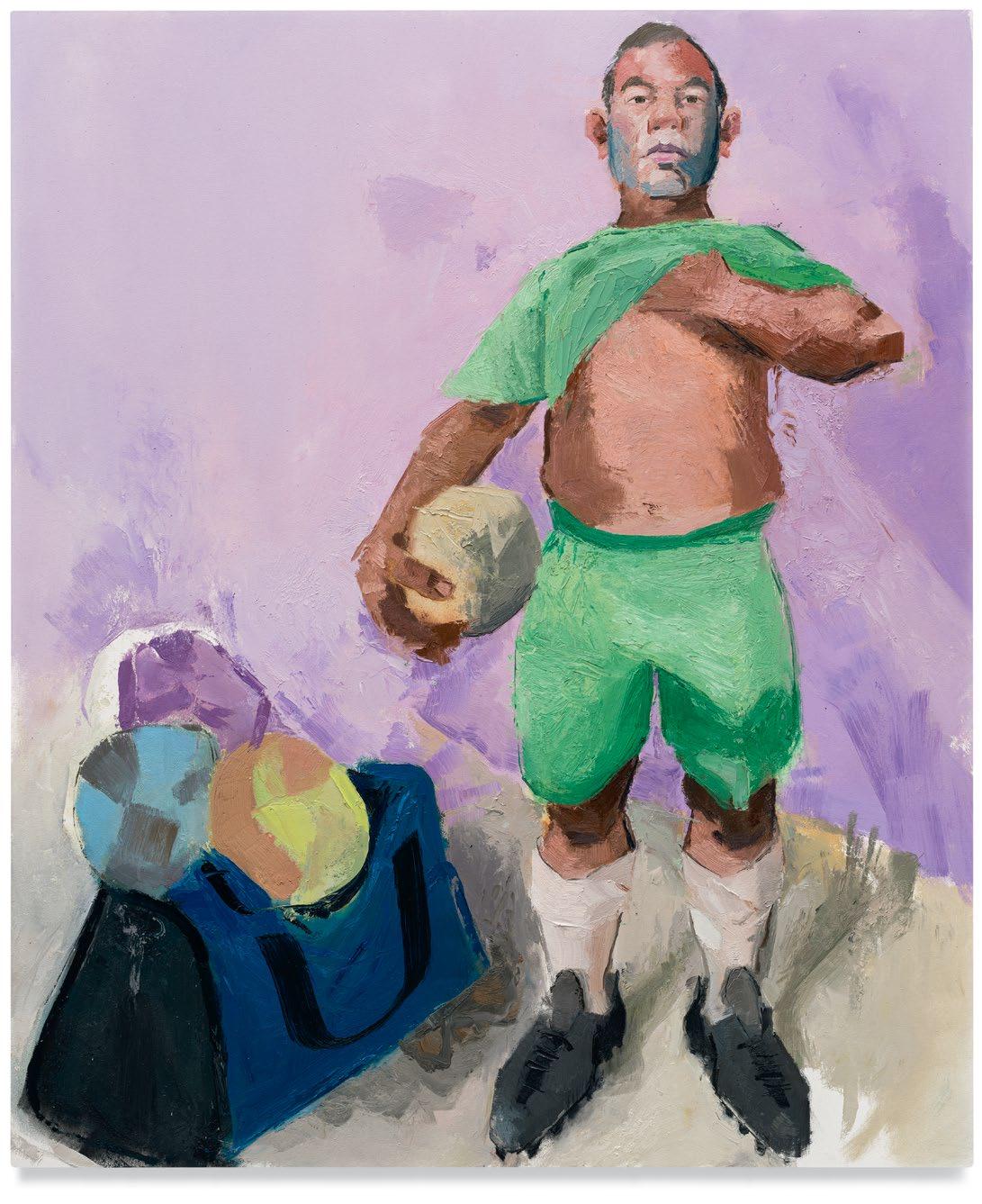

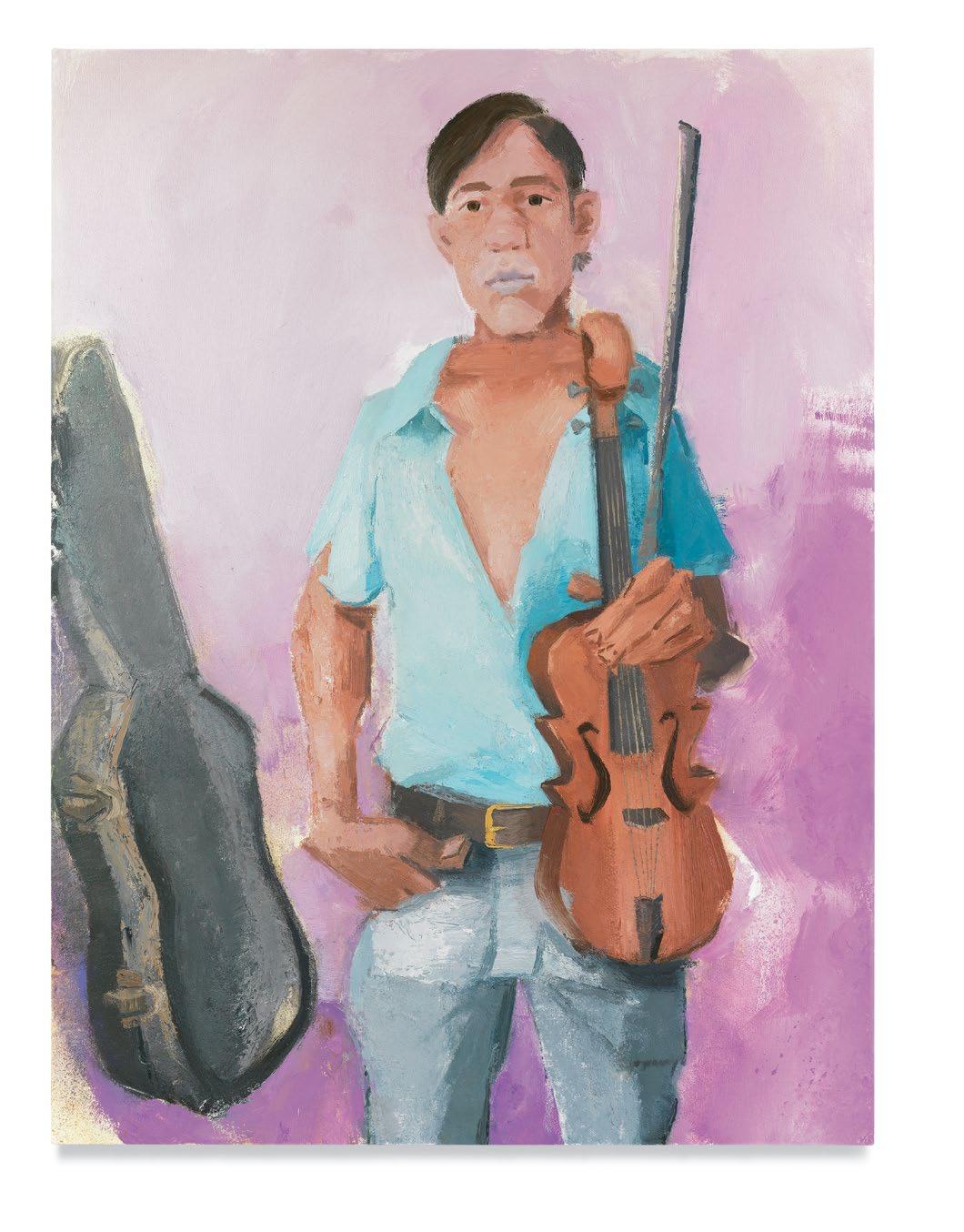

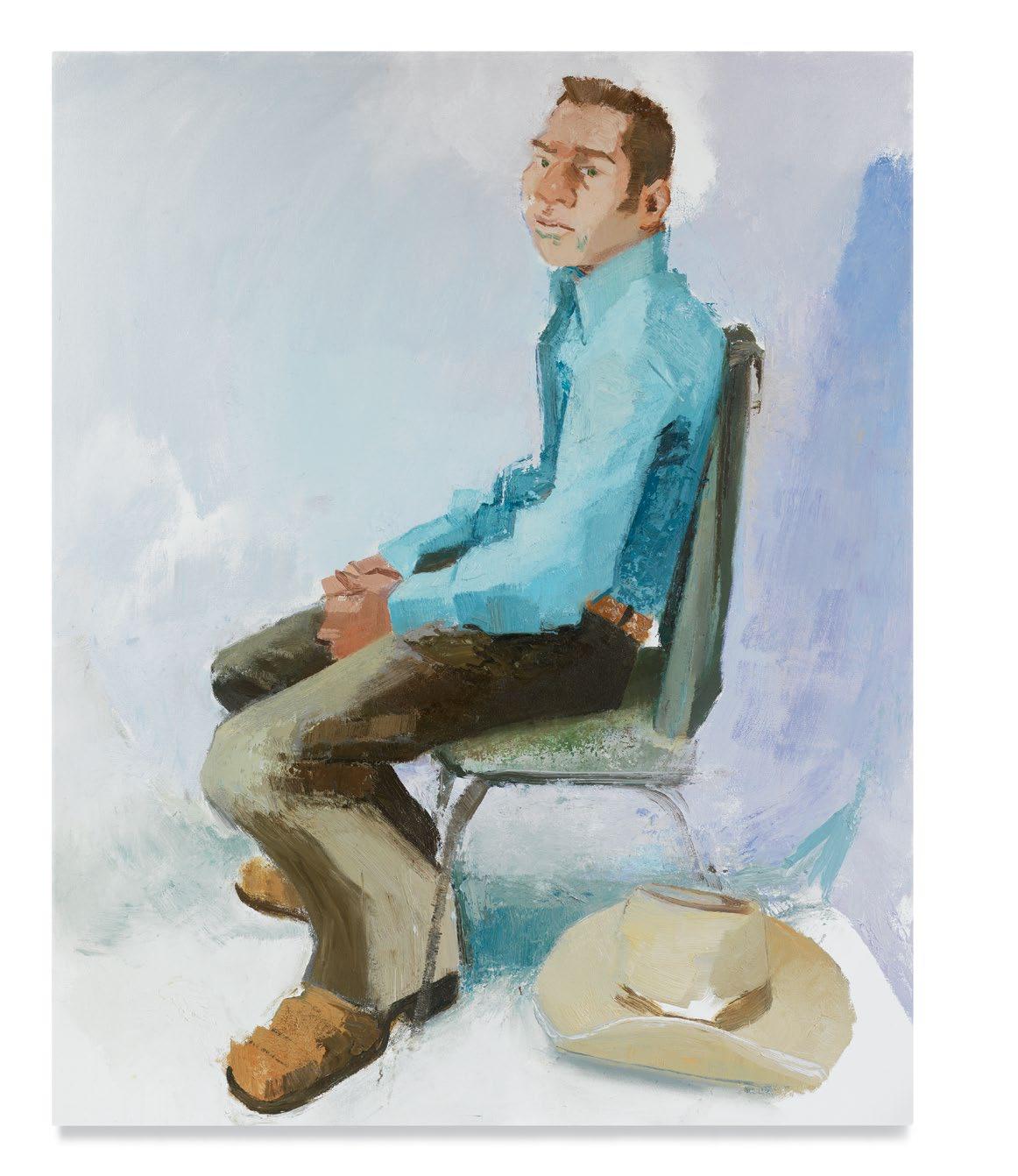

These four categories are not the usual groupings by which pictorial art, particularly painting, usually gets discussed. Those groups would be: still life, landscape, and portraiture, as well as abstraction. Subcategories such as vanitas, interior, historical, closeup, gestural, or geometric would further distinguishing various approaches. But the specificity—even idiosyncrasy—of the categories into which Sonsini’s paintings fall points viewers in the right direction if we want to come to understand just what it is that the singular—even idiosyncratic—Los Angeles painter is up to with his powerful pictures of individual men whose livelihoods depend on their physical skills, such as digging, hauling, and all manner of rough construction; as well as seat-of-the-pants acrobatics, like juggling and unicycle riding; along with ad hoc performances of traditional and improvised songs, o en with guitars, violins, and drums.

Sonsini’s paintings are portraits, of course, but they are portraits of a peculiar sort. Like portraits throughout history, they give form to the relationships that transpire whenever a painter regards a si er and strives to commit the si er’s likeness to canvas or paper. But Sonsini’s portraits do not end there. In fact, that’s where they become especially interesting—when we viewers begin to see what has happened while the portraits were being made and start to experience some of that identityshi ing drama for ourselves.

As Sonsini spends long periods of time with the men he has chosen to paint—who are themselves taking a break from their manual, artisanal, and performative labors—he embarks on his own manual, artisanal, and performative labors. For Sonsini, the act of painting is a process that is hands-on and open-ended. Its twists and turns are

unpredictable and far more physical than the cerebral machinations that drive and define idea-obsessed art, which prioritizes rational plans and good intentions, o en at the expense of bodily impact. As Sonsini works in his studio—looking closely, making studies, studying appearances, and striving to get beyond them—the boundaries between painter and si er loosen, the former finding himself wholly focused on just what it is in the si er that has captured his a ention and compels him to capture that fascination in an image.

The result of that back-and-forth, between painter and si er, is a painting whose subject is not just the person depicted, but the dynamic interaction that takes place as Sonsini goes outside of himself to convey in paint the otherness that a racted him in the first place. That interaction cannot be conveyed abstractly or symbolically; knowing about it is far different from experiencing it for oneself. And that’s what Sonsini’s portraits do for viewers: They translate his desire-driven engagements with others into a form that invites us to experience similar identity-confounding engagements—imaginatively and contemplatively, of course, but they are no less resonant for their introspective, soul-searching nature. When we viewers enter the picture, metaphorically and more, our interactions with Sonsini’s subjects pick up where his le off. His portraits present us with images in which it’s difficult to determine who’s revealing more of their themselves. The more deeply we engage with Sonsini’s pictures of men we’ve never met, the more evident it becomes that what’s revealed in these bewitching point-blank paintings is ourselves: our most intimate and definitive understanding of who we are as individuals, and what that means when it comes to how we perceive others, as well as how we treat them as people.

Empathy is Sonsini’s great subject. The bedrock of everything he does as an artist resides in his exploration of how an individual’s emotional involvement with another shapes both perception and knowledge, o en transforming one’s relationship to everything around one—including one’s self. The fundamental connection between people is at the core of his work as an artist. And, as a painter to whom process is everything, Sonsini refrains from telling us what to think. Instead, he shows us how it is with him and invites us to see how it might be with us. His paintings argue silently and passionately, hiding nothing as they lay it all on the line.

The first of the four groups into which Sonsini’s new paintings fall, paintings made from life, have been a part of Sonsini’s repertoire the longest. It began in 1986, when he invited neighborhood guys into his studio and painted their portraits. It continued, from 1996–2001, when he limited the focus of his portraits to a single subject: his partner, Gabriel Barajas. It includes his portraits of day workers, the majority of which he painted from 2001 to 2010, as well as his portraits of recreational soccer players, cowboys, mariachis, and street performers, both musicians and acrobats, which he has painted since 2010 and continues to paint today.

Sonsini’s series of day-worker portraits began at the corner of West Olympic Boulevard and South Mariposa Avenue, in the heart of what is now Korea Town, where he would hire day workers for, appropriately, a day. A er that session of nonstop drawing, he would know if he wanted to continue, with more days of making studies before he would know if he would proceed with a painting—a much bigger time commitment. At the beginning, the men were suspicious, both uncomfortable and distrustful about ge ing paid to spend long days in an artist’s studio while he worked. That tension and vulnerability are palpable in the portraits, whether the men are depicted individually or in groups, seated or standing, up close or from a distance, head on or in three-quarter profile. It’s countered by the equal and opposite presence of curiosity and surprise. The knowledge that time marches on also suffuses these portraits, suggesting that all things, good and bad, eventually pass, and that whatever happens today might very well be different tomorrow, simply because nothing is permanent.

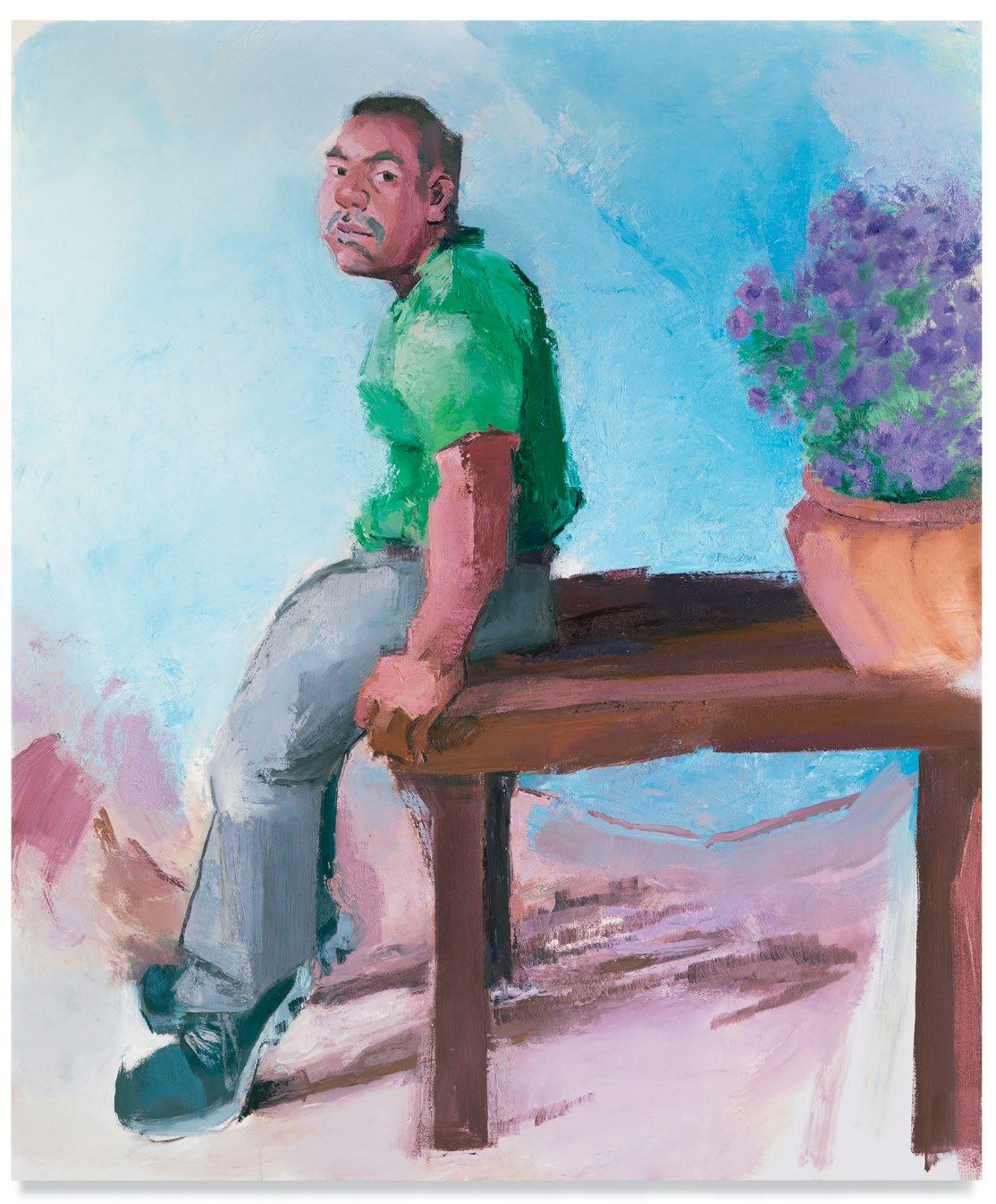

Over the years, Sonsini has painted many of his si ers again and again, establishing and sustaining relationships with them, both professional and personal. He has captured, in oil on canvas, not only the physical changes that inevitably take place as people age, but his own changing relationship to the men he has depicted. That’s evident in the so ening and strengthening of their physical presence, a deepening and widening of the emotional resonance between si er and artist, and, as a consequence of those transformations, the basis for more complex interaction between individual viewers and individual sitters—with the boundaries between self and other loosening in the process.

In this exhibition, the first to present all four of the ways in which Sonsini works, the canvases painted directly from life include both portraits and still lifes. The portraits

depict Barajas, his partner of more than 20 years. The still lifes feature shirts models le behind in Sonsini’s studio. The still lifes are, in a sense, portraits of shirts. They have the feel of talismans or relics, evoking the presence of the absent men while emphasizing that no picture captures the totality of an individual. Their impact, like the impact of all portraits, resides in the imaginations—and interior emotional lives—of viewers.

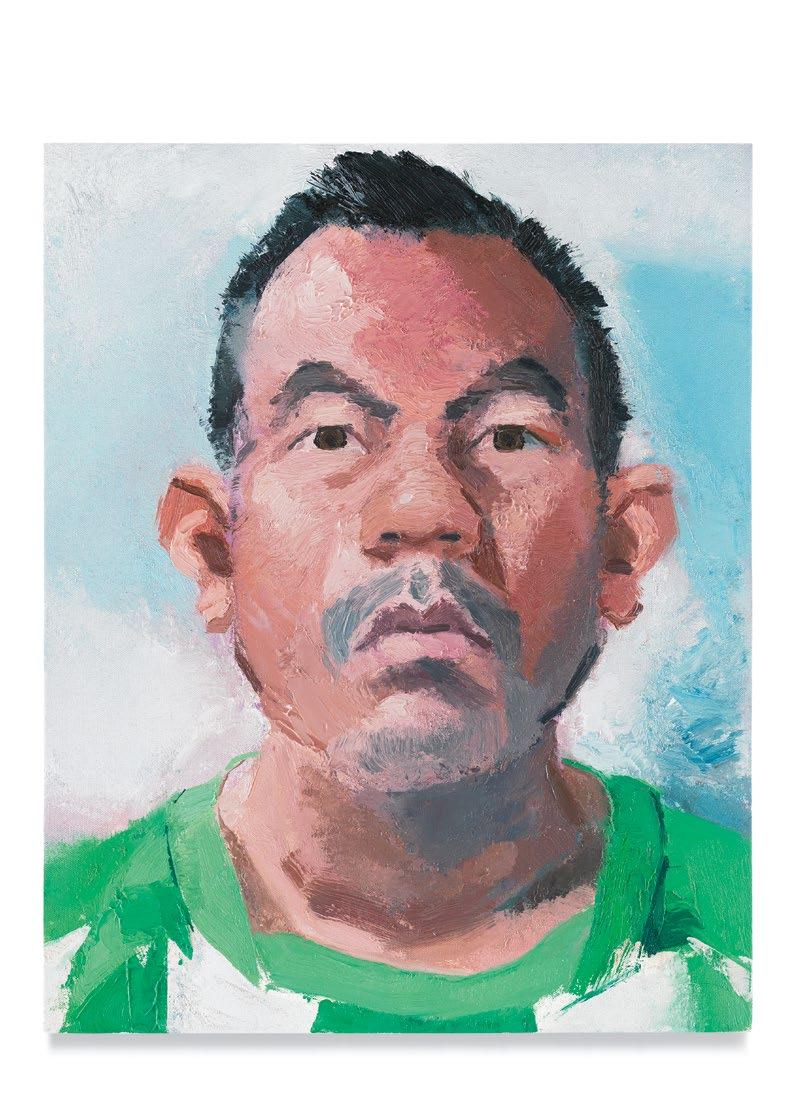

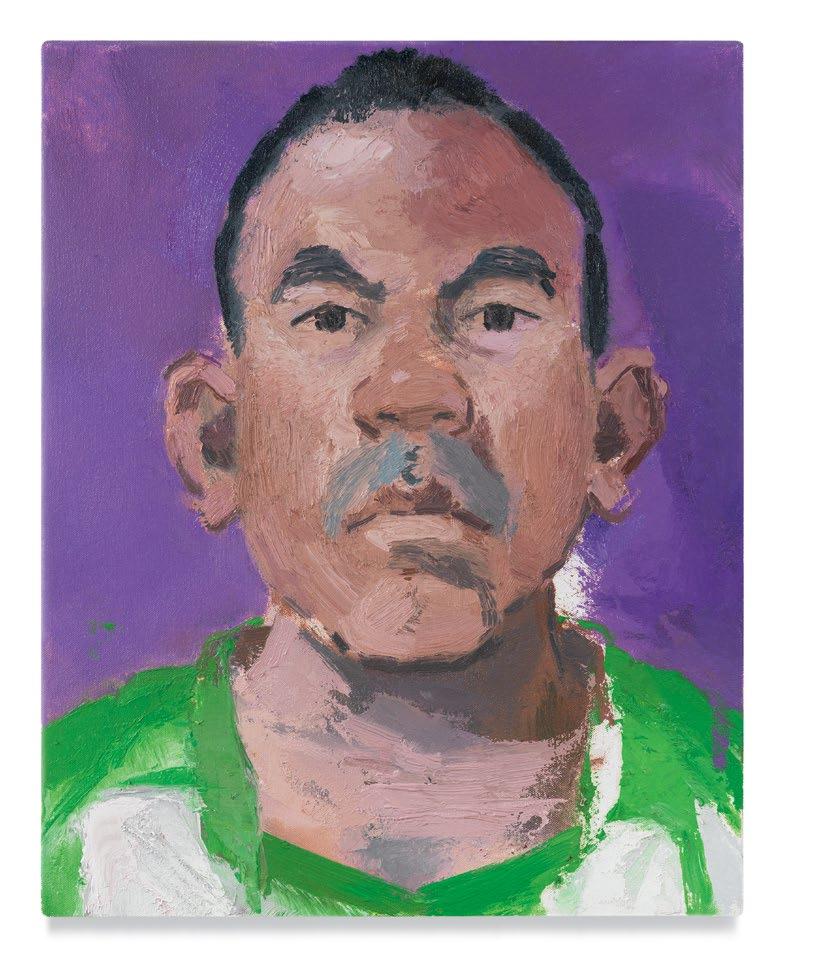

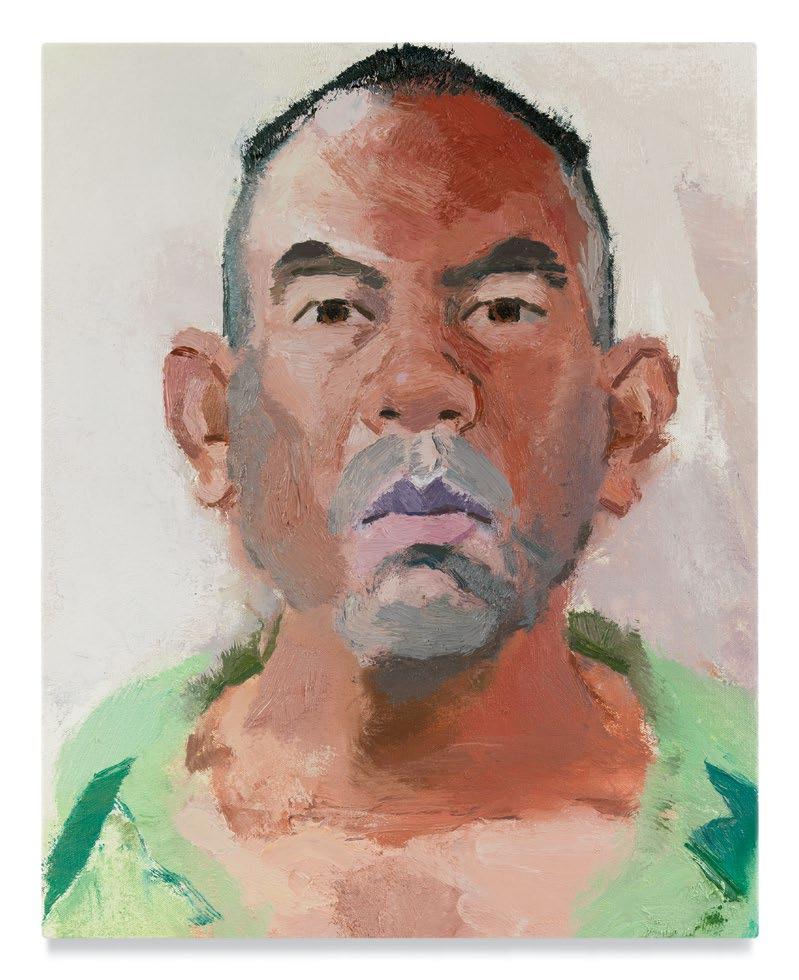

Sonsini’s portraits of Barajas, who he painted, exclusively, from 1996 to 2001, function similarly. Portraying someone Sonsini knows intimately—perhaps be er than himself— these riveting pictures of an individual invite viewers to step up close and to stand where we would stand if we were having a conversation with someone. Of course, the paintings are silent, and the only conversations that unfold take place in our heads. What’s most remarkable about Sonsini’s approximately lifesize depictions of Barajas is the math-defying distance he has built into the space between Barajas’s face and each viewer. To stand before these portraits is to feel that despite your proximity to the painting, which is about an arm’s-length away—an unbridgeable expanse separates you from the person in it. What you know and what you feel are incommensurate with one another. You get caught in the crossfire of your inner

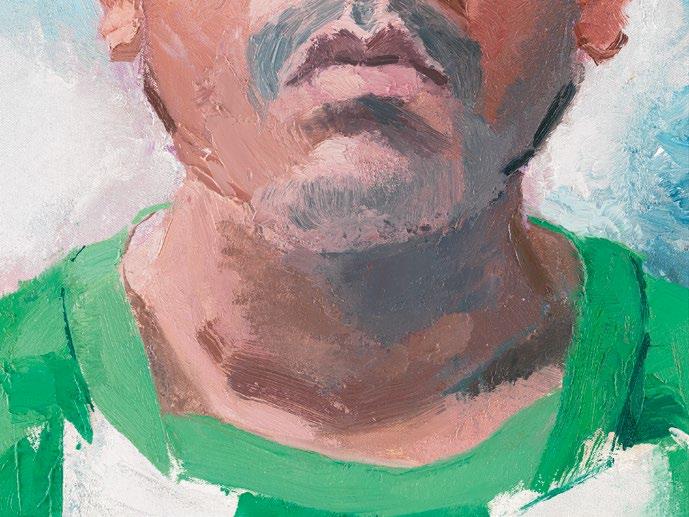

Gabriel, (detail), 2021, Oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches, 50.8 x 40.6 cm

sentiments. Although Sonsini has painted Barajas in a casual, collarless shirt (its bright stripes and glossy sheen suggesting a polyester soccer jersey) and in a pose no more highbrow than those of DMV photographs, Barajas’s physical presence is anything but informal: Self-possessed, even noble, he embodies the dignity of true leaders, something that politicians once strived for but that seems to have fallen out of fashion. A sense of unflappable equanimity—or intrinsic poise—emanates from his interior, revealing that he is not one to be trifled with, nor one who sweats the small stuff. It doesn’t take a great leap to imagine that he has seen a lot in life, yet is still open to the moment, ready and eager to see what the future might bring. A kind of sanguine fatalism lives in Sonsini’s portraits of Barajas.

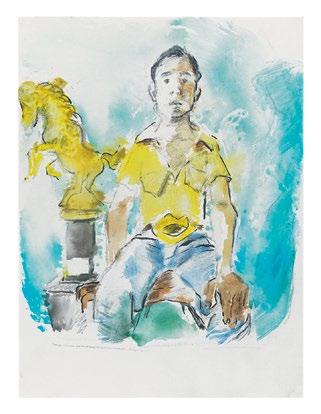

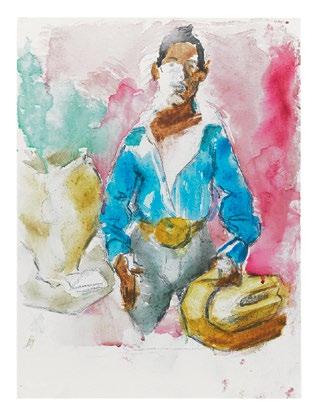

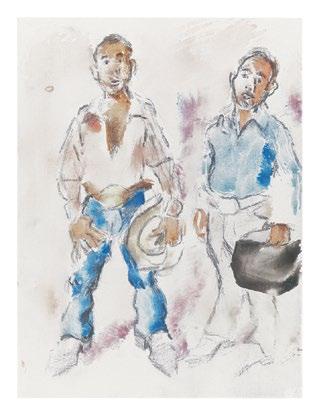

A similar dynamic unfolds in the second group of works that Sonsini has painted, which includes several versions of Study for Byron and Trophy, several versions of Study for Francisco, and several versions of Study for Roger and Francisco. All were made with no si ers present, just Sonsini alone in his studio during the lockdown. Until four or five years ago, he made all his studies in pencil on paper. But when he needed to zero in on some boldly colored soccer jerseys in a still life, he gave watercolors a try. And he liked what he discovered. The medium provided just the elusiveness he was a er, just the right amount of suggestiveness to make it clear that the point of his portraits was not resemblance or likeness or fidelity to surface appearances, but something less tangible, less literal, less articulate-able: the singular presence of the man before him, the ineffable yet undeniable reality of him as himself.

Sonsini also found that using watercolors on inexpensive canvas board intensified the elusiveness he was a er because the roughness of the surface obscured resemblance in ways that perfectly suited his purposes, le ing him get past appearances so that his pictures might capture the reality that does not immediately meet the eye but that still can be sensed or intuited or felt, that can be known in ways that go beyond logic and rational assessment.

The pandemic forced Sonsini to be a solitary painter. Rather, the working with a model—or several models—before him, he found himself alone in the studio. The conversational back-and-forth—of instructions and inquiries, suggestions and requests, cha er and banter—disappeared under quarantine. And Sonsini was surprised by what he discovered: that he was not only a social painter but that he was also a

Le to right: Study for Byron & Trophy, 2021, Watercolor on canvas board, 16 x 12 inches, 40.6 x 30.5 cm; Study for Francisco, 2021, Watercolor on canvas board, 16 x 12 inches, 40.6 x 30.5 cm; Study for Roger & Francisco, 2021, Watercolor on canvas board, 16 x 12 inches, 40.6 x 30.5 cm

solitary painter, an artist who could work alone in the studio, his studies and memories grounding his work in the world. Initially, Sonsini assumed painting solo would be very different than painting from life. But as he got more deeply into it—initially because the pandemic kept models out of his studio but eventually because painting solo allowed him to sharpen his focus—he found substantial similarities between the two.

Painting from life, a er all, consists of innumerable moments of observation and brushwork—of looking and applying paint to canvas—o en flipping back and forth very swi ly. Because of the rapidity of the two activities, it’s o en forgo en that the painter, when painting from life, is still working from memory—just very short-term memory—from what he has just seen to what he paints, and then again, when he observes the marks he has made and looks back at the si er to check his work, to confirm its accuracy or adequacy before making another mark. So, when Sonsini paints from memory, he simply draws out that in-between moment, prioritizing the image that has imprinted itself in his mind’s eye, assessing what has been le there by a lifetime of looking and thinking, wondering and willing, painting the world outside himself as he made a place for himself in it. Decades of doing what he has done in the studio sustain him, the muscle memory of innumerable brushstrokes and wrist-flicks delivering details that add up to images that bypass the control—and limitations—of conscious deliberation and decision-making. Plus, when Sonsini

paints from life, he o en works on his canvases a er a si er has departed for the day, sometimes repainting their faces so that his portraits get past surface appearances. Such freehand revisions are o en thought of as poetic license, suggesting that painters are creators who do what they like to express themselves. With Sonsini, it’s more accurate to think of such a er-hours portraiture as fidelity to something to deeper and truer. He’s not winging it or making stuff up or transforming his si ers into his fantasy of them. He’s trying to get down in paint their physical singularity or electrifying presence, something some people might call their soul or spirit or essence— terms Sonsini would never use because they are too presumptuous and high-flown, lo y and idealized. As a painter, he sticks to what he knows of the material world, to what he experiences in his interactions with others—and with paint.

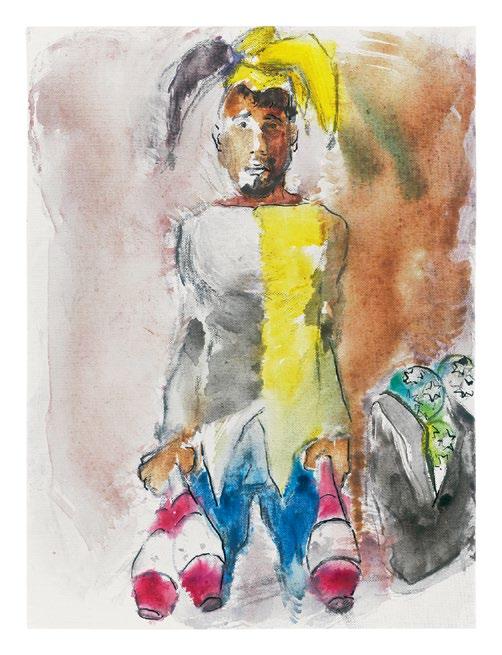

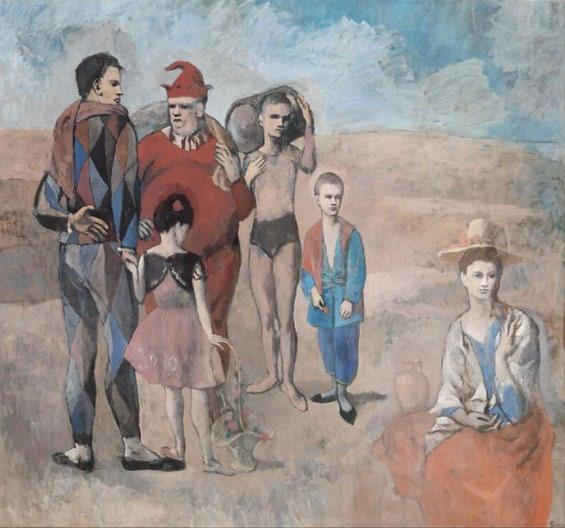

A series of watercolors Sonsini painted from life, in Querétaro, Mexico—where he and Barajas have lived, four months each year, since 2017—are the basis of the third group of works in this exhibition: the approximately lifesize oils on canvas that he has made from watercolors. This series of portraits introduces a new subject to Sonsini’s oeuvre: the street performers—known as malabaristas—who stage quick performances for the passengers of vehicles stopped at busy intersections throughout the city of two million, which is located about 130 miles northwest of Mexico City. When Sonsini first saw the malabaristas performing their fugitive concerts and DIY acrobatics he was riveted. Images of Pablo Picasso’s saltimbanques flashed through his head, as did his own very early still life paintings of the outfits and costumes from Bob Mizer’s legendary photography studio, Athletic Model Guild, not to mention Sonsini’s paintings of day workers, who sometimes came to the studio dressed for the weekend—to play soccer, ride horses, or in their Sunday finest: o en in the hats, belts, and boots of vaqueros. The fascination Sonsini felt on first seeing the malabaristas is integral to all his paintings; the jaw-dropping, a-ha moment of this-is-it excitement is there at the start of each portrait. Without it, Sonsini would never begin the laborious process of making a portrait—of finding a si er, doing study a er study, first in pencil and then in watercolor, and only then going to oil on canvas and working day a er day, week a er week.

When Sonsini hired the malabaristas to sit for individual and group portraits, he made dozens of studies, each taking a day. He completed three oils on canvas, each

taking about a month. At the end of his time in Querétaro in 2019 he packed up his studies and returned to Los Angeles. His plan was to resume painting the malabaristas when he returned to Querétaro in March of 2020. But the pandemic confined him to his studio in Los Angeles. A er months of restlessness, he decided to make oil paintings from the watercolor studies he had made in Mexico. Working alone in his studio he discovered that his studies had more information in them than he had thought. They astonished Sonsini in the same way the malabaristas did when he first saw them. They triggered more connections between what he saw and what he felt, what he wanted and what he needed. They had everything necessary to make a painting—the solid foundation for a singular portrait. Not having the models in his studio did not get in the way of him homing in on the essentials. He found that he could get out of himself and into the images the men presented just as effectively as if they were there. So Sonsini painted jugglers and musicians, as well as a stilt walker and a unicycle rider, with the reserve and seriousness that suffused his portraits of

Study for Enrique, 2021, Watercolor on canvas board, 16 x 12 inches, 40.6 x 30.5 cm

Barajas and the day workers, soccer players, and cowboys. His malabarista portraits crackle with silent energy. Their stillness has the presence of an ongoing activity that has been paused—neither frozen nor arrested, just momentarily suspended— and poised on the cusp of erupting, like a tautly coiled spring. That sense of incipient, impending action is integral to all of Sonsini’s portraits. It takes its sharpest form in his malabarista paintings, which make us see his earlier works more fully and deeply, animated or electrified by a similar energy, albeit in a more subdued form. Like all his paintings, his malabaristas bring viewers face to face with others who are, simultaneously, like us and not like us. The overlap and tug of shared and distinct characteristics enlivens the interaction, fueling our curiosity about others and our uncertainty about what we thought we knew about ourselves.

The fourth group of works in this exhibition shows Sonsini going full circle: working from life, working from memory, and working from watercolors—all in one work. Since the restrictions from the pandemic have ended and he has been able to have

Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, 1905, Oil on canvas, 83 3⁄4 x 90 3⁄8 inches, 212.8 x 229.6 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Chester Dale Collection, Accession Number 1963.10.190

© 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

models in the studio once again, he has directed them to stand and sit so that their arrangements and postures match those of the compositions of some of the watercolors he made before the quarantine. In a sense, Sonsini has used his studio to set up, for an audience of one, DIY tableaux vivants. Whether he starts with a watercolor made from memory or one made from life, he uses that image to pose his si ers so that he can make another portrait of them. The elaborate, somewhat circuitous process emphasizes that the whole point of Sonsini’s endeavor is to loosen the boundaries between himself and his si ers, to relax the distinctions between what he’s looking at and what he’s doing, so that we viewers might find ourselves in the mixture of images and bodies, selves and others: intimately engaged with his portraits and the men in them, initially confused by our relationships to them and eventually convinced that we share more than we assumed. Like all Sonsini’s portraits, these incite the soul-stirring self-expansion that happens whenever we see something or someone who takes us out of ourselves, beyond our ordinary relationship to reality, and into a world that’s bigger and be er than the one we began with—more inclusive and nuanced, more expansive and labile, riper and richer than anything we imagined, much less experienced. Sonsini’s paintings don’t simply tell us how important such transformations are to him: They show us how it happens for him—always with the conviction that it doesn’t end there.

The eyes of Sonsini’s si ers are essential to the dynamic that unfolds when we look at his portraits. Sonsini paints his si ers as if they are looking directly into his eyes— and, by implication, into ours. But there’s something more to the eyes of Sonsini’s si ers. While they are clearly fixed on us, they simultaneously look somewhere else—beyond, and above us. Initially, it’s tempting to imagine—or fantasize—that they’re looking into themselves. But that’s wrong. To look into their eyes is to see that Sonsini has painted them as if they are looking at themselves from a distance— as if in a mirror, which o en seems to be located overhead, to the le or right of where we viewers are standing. The impact of that fact is complex and far reaching. It reveals that the si ers are not simply the objects of our gazes. While they know that they’re being regarded by us, they are actually regarding themselves. Most important, they see themselves not through our eyes but from another, external position. It’s a kind of double vision, a way of seeing the world not from a single perspective or fixed point of view, but one that grasps the multifaceted reality of the world

around us and the social relationships that define it in a more complex, nuanced, and sophisticated manner.

That’s what Sonsini gives viewers: the opportunity to experience reality from more than one perspective, one position, one point of view. His is an art of multiplication, of not just imagining what it might be like to be someone else, but of actually, physically, phenomenologically experiencing a kind of doubleness—or a dual perspective. Once experienced, that kind of consciousness makes one-dimensional ways of seeing seem...well, one dimensional: shallow, flat, and impoverished—mere shadows of the rich, psychologically complicated and o en contradictory relationships that make up the real world.

That’s a form of Realism that gets beyond appearances—and the o en-wrongheaded goal of resemblance or likeness—to get to what really ma ers: understanding that people, like paintings, cannot be understood from a single perspective, much less known completely or fully, and that part of the excitement of being alive is knowing that you can’t know everything—about anyone or anything—while understanding that that’s far be er than presuming to know it all. The mystery intrinsic to identity is embodied by the men in Sonsini’s portraits. So, too, is the distance intrinsic to all human relationships. A er all, empathy begins in distance—and grows from there.

That’s what Sonsini offers viewers: Taking us outside ourselves, his portraits draw us into their worlds—and beyond.

David Pagel is a Los Angeles-based critic and professor of art theory and history at Claremont Graduate University. An avid cyclist, he is a seven-time winner of the California Triple Crown.

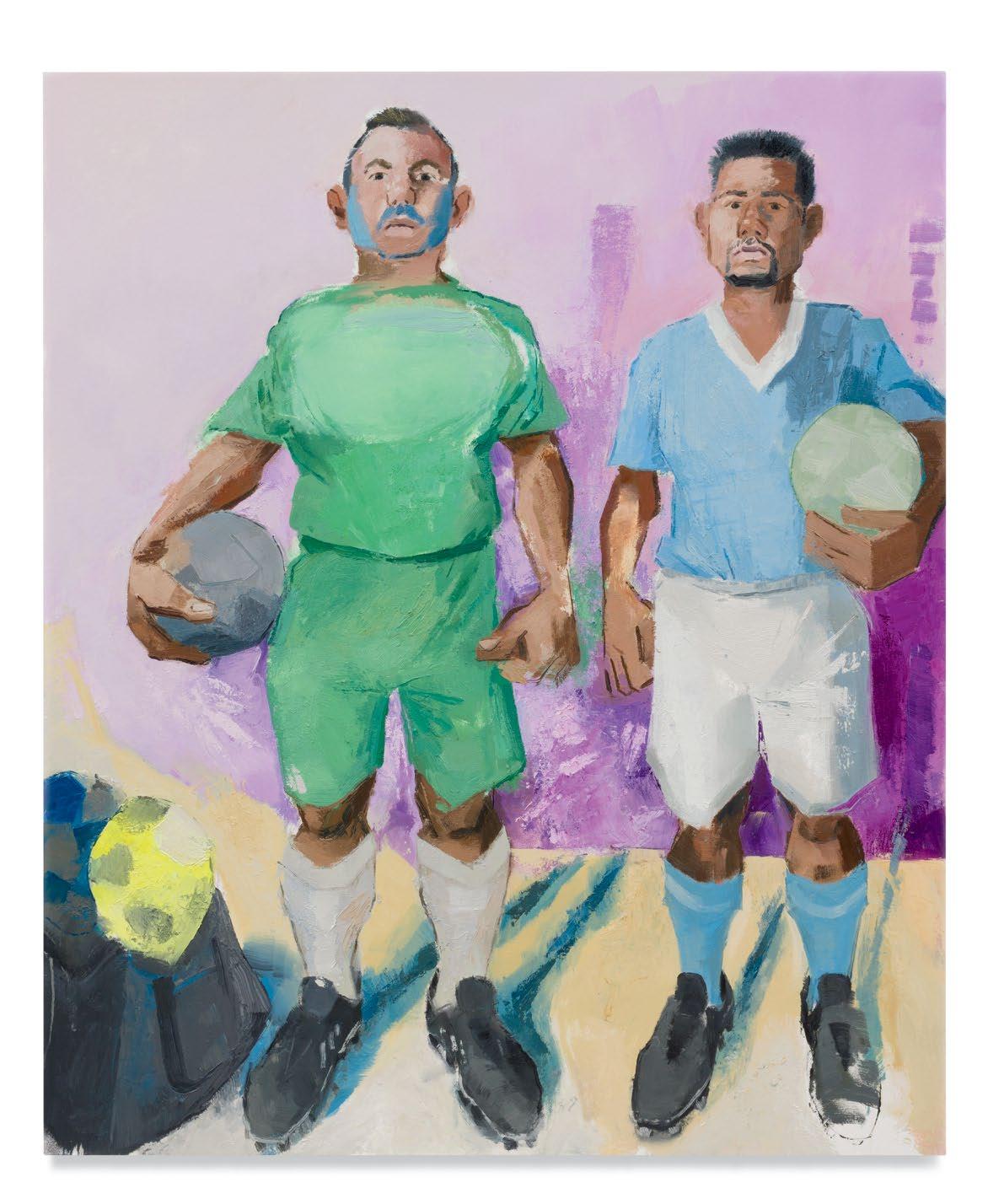

Duo, Will & Francisco, 2019

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 inches

182.9 x 152.4 cm

Apt. 206, 2019

Oil on canvas

45 x 36 inches

114.3 x 91.4 cm

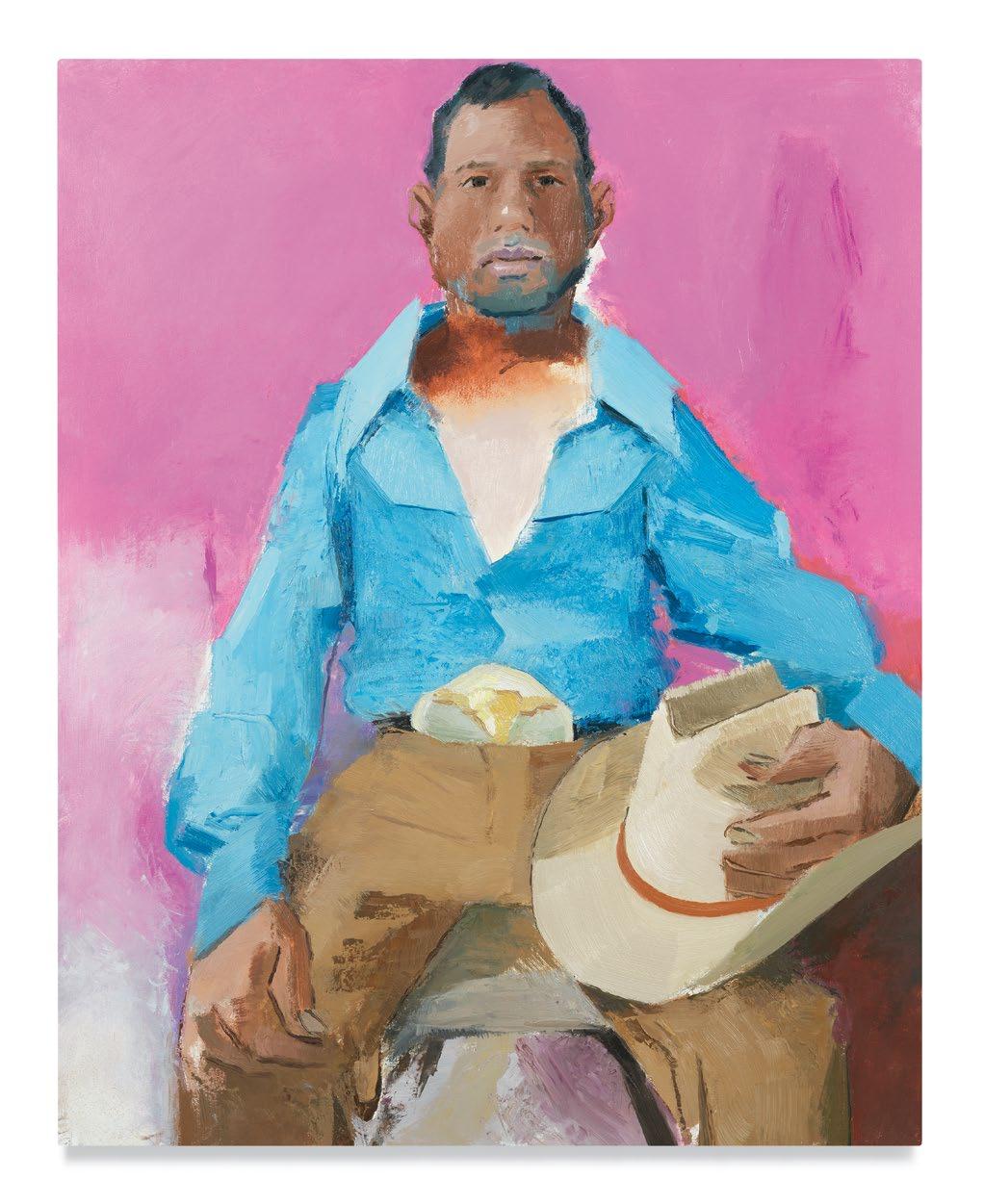

Francisco, 2020

Oil on canvas

48 x 36 inches

121.9 x 91.4 cm

Gabriel & Francisco, 2020

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 inches

182.9 x 152.4 cm

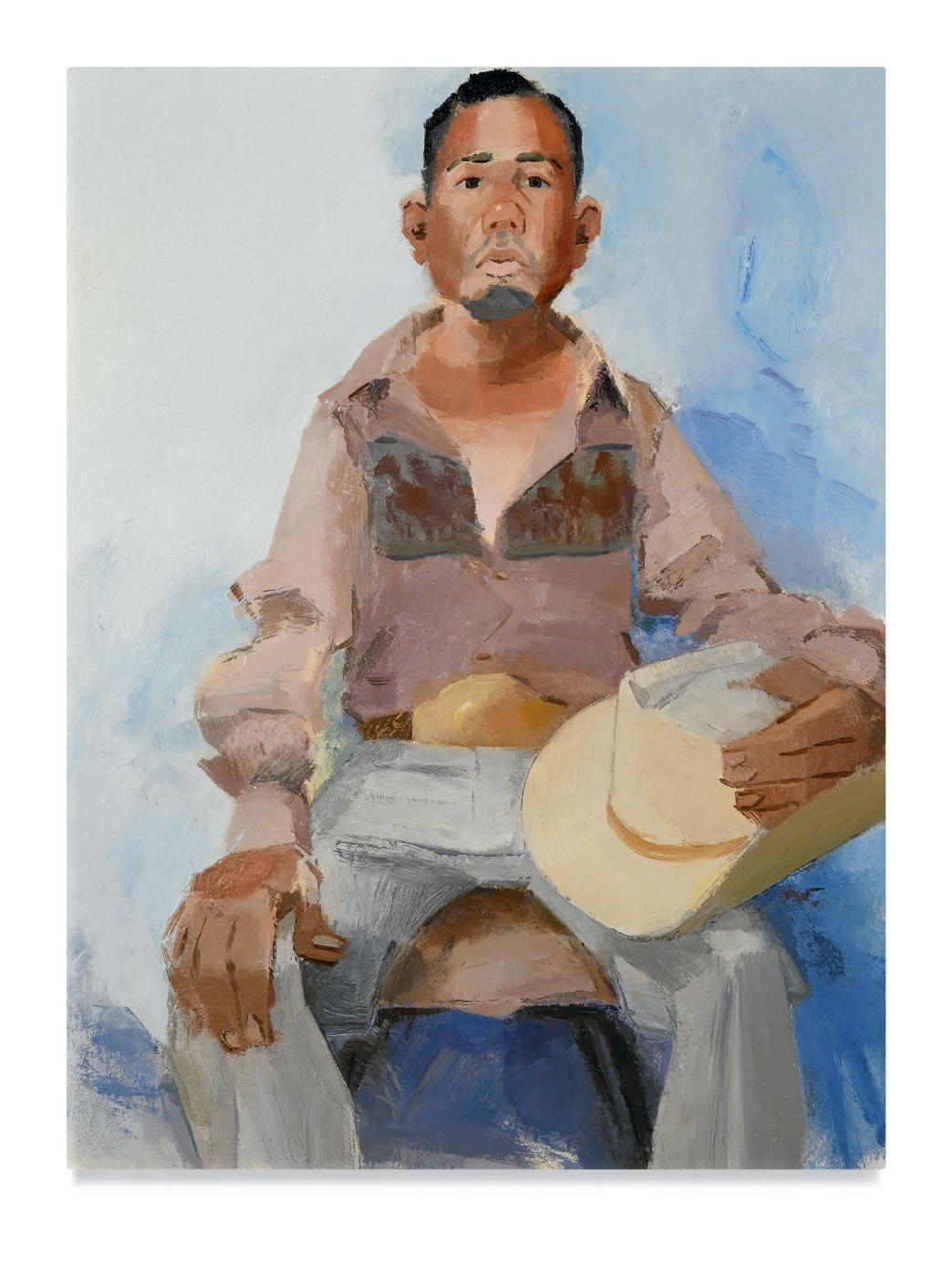

Guillermo, 2020 Oil on canvas

45 x 36 inches

114.3 x 91.4 cm

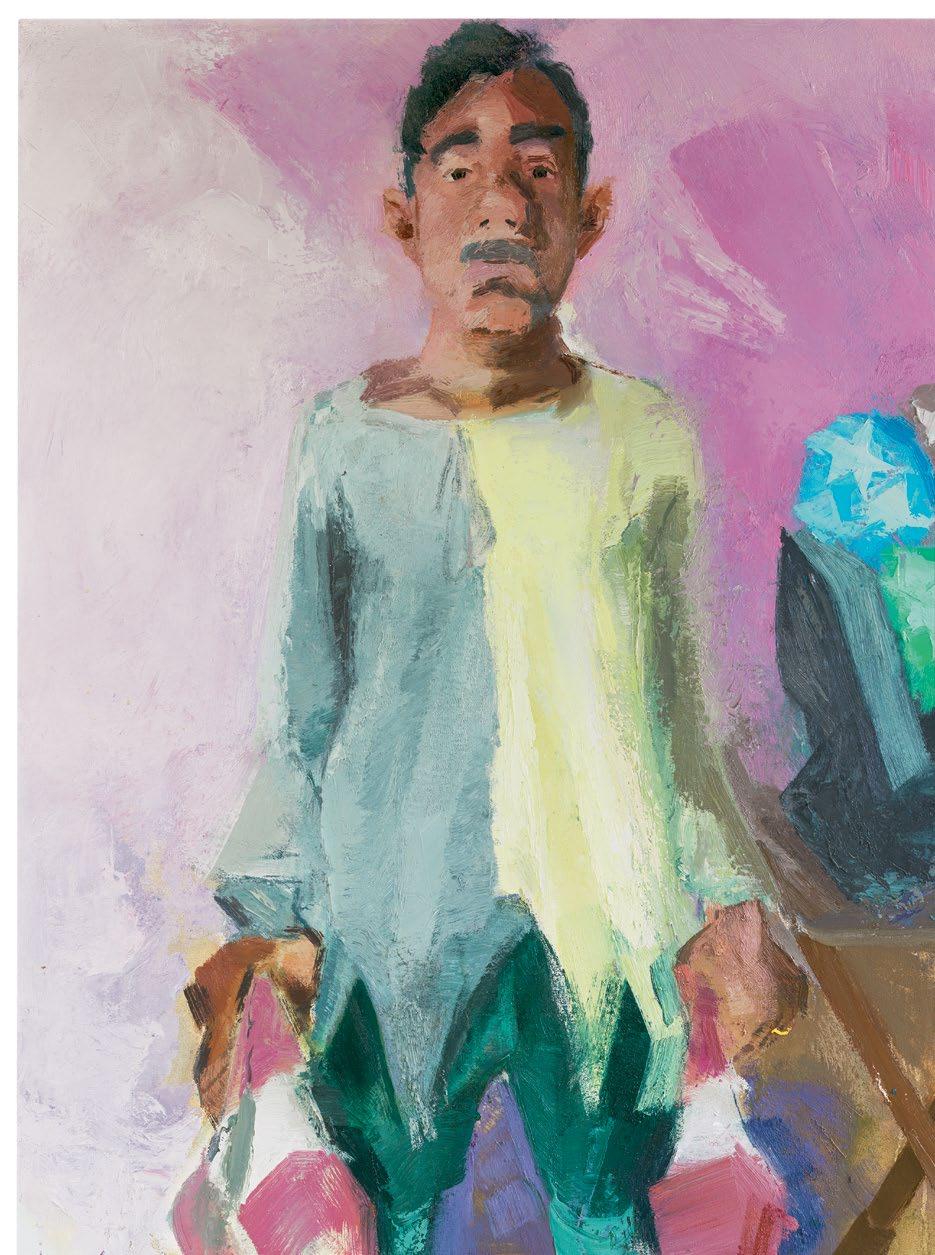

Apt. 210, 2021

Oil on canvas

48 x 36 inches

121.9 x 91.4 cm

Enrique, 2021

Oil on canvas

48 x 36 inches

121.9 x 91.4 cm

Gabriel, 2021

Oil on canvas

20 x 16 inches

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Gabriel, 2021

Oil on canvas

20 x 16 inches

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Gabriel, 2021

Oil on canvas

20 x 16 inches

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Gabriel, 2021

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 inches

182.9 x 152.4 cm

Gabriel, 2021

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 inches

182.9 x 152.4 cm

Gabriel, 2021

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 inches

182.9 x 152.4 cm

Josef, 2021

Oil on canvas

48 x 36 inches

121.9 x 91.4 cm

Raul, 2021

Oil on canvas

60 x 48 inches

152.4 x 121.9 cm

JOHN SONSINI

Born in Rome, NY in 1950

Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA and Querétaro, Mexico

EDUCATION

1975

BA, California State University, Northridge, CA

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2021

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2020

“Cowboy Stories & New Paintings,” Susanne Vielme er | Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA

2019

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“A Day’s Labor: Portraits by John Sonsini,” Art Design & Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA

2018

“Daywork: Portraits,” Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, CA

2016

Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2015

“John Sonsini,” Patrick Painter Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2013

“John Sonsini: New Paintings,” Bentley Gallery, Phoenix, AZ

2012

“John Sonsini: Paintings,” Kucera Gallery, Sea le, WA

“John Sonsini: New Paintings,” Inman Gallery, Houston, TX

2011

“Los Vaqueros,” James Kelly Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM

“John Sonsini: Men,” Hamilton College, Emerson Gallery, Clinton, NY

2010

“Broad Reminders: The Paintings of John Sonsini,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

“Portraits from Los Angeles,” Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, Logan, UT

2008

“New Paintings,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

2007

“John Sonsini: Paintings and Drawings,” Atkinson Gallery, Santa Barbara City College, Santa Barbara, CA

2006

“John Sonsini,” Cheim & Read, New York, NY

2005

“New Paintings,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

“John Sonsini,” Anthony Grant Gallery, New York, NY

“Cerca Series: John Sonsini,” Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA

2003

“Portraits,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

2002

ACME., Los Angeles, CA

“John Sonsini,” Peter Blake Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA

2000

“Gabriel,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

1999

“Gabriel, New Paintings,” Dan Bernier Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1998

“John Sonsini, New Photographs,” David Aden Gallery, Venice, CA

1997

“Photographs of John Sonsini,” Tom of Finland Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1995

Dan Bernier Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

1986

Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1983

Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1982

Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2021

“Art and Hope at the End of the Tunnel” (curated by Edward Goldman), Fischer Museum, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

2020

“Really.” (curated by Inka Essenhigh & Ryan McGinness), Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“20 Years Anniversary Exhibition,” Vielme er Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

2019

“The Warmth of Other Suns: Stories of Global Displacement,” The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

“Collecting on the Edge,” Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, Logan, UT

2018

“Belief in Giants,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“Modern and Contemporary,” Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, Stanford, CA

“From the Collection of Karen & Robert Duncan,” The Assemblage, Lincoln, NE

2017

“The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers,” National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

“¡Cuidado! - The Help,” Greg Kucera Gallery, Sea le, WA

2016

“Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

“Us is Them,” Pizzuti Collection, Columbus, OH

2015

“The Human Touch: Selections from the RBC Wealth Management Art Collection,” Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester, NY

2014

“The Triumph of Love: Beth Rudin DeWoody Collects,” Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL

“Who we are, Selections from the Collection of Karen & Robert Duncan,” Clarinda Carnegie Art Museum, Clarinda, IA

“Concrete Infinity, Selections from the Permanent Collection,” Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA

2013

“Art of the West,” (on view through to 2020), Autry National Center of the American West, Los Angeles, CA

“The Human Touch: Selections from the RBC Wealth Management Art Collection,” Sco sdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Sco sdale, AZ

“Mr & Mrs,” James Salomon Contemporary, New York, NY

2012

“Body Language,” Orange Coast College, Costa Mesa, CA

“All I Want is a Picture,” Angles Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“SFMOMA: Contemporary Painting, 1960 to the Present: Selections from The Permanent Collection,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA

2011

Tobey C. Moss Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“Works of Paper,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

“Mise-en-Scène,” Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, OR

2010

“Personal Identities: Contemporary Portraits,” University Art Gallery, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, CA

“Private Display,” New York Academy of Art, New York, NY

“Disquieted,” Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR

“Think Pink,” Gavlak Gallery, Palm Beach, FL

“The Human Touch,” Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE

2009

“Posture,” Peter Blake Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA

“With You I Want to Live,” Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale, Fort Lauderdale, FL

2008

“The Sum of Its Parts,” Cheim & Read, New York, NY

“Other People,” UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA

2006

“Selected Paintings - Los Angeles,” Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA

“Twice Drawn,” Tang Teaching Museum, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY

“Art on Paper,” Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC

2005

“Plip, Plip, Plipity,” Richard Telles Fine Art, Los Angeles, CA

2004

“Rogelio,” (curated by JoAnne Northrup), San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

“About Painting,” Tang Museum, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY

“Singing My Song,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

“SPF, Self-Portraits,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2003

“ACME. @ Inman,” Inman Gallery, Houston, TX

“intimates,” Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

2002

“L.A. Post Cool,” The San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

“nude + narrative,” P.P.O.W., New York, NY

“Representing L.A.,” Frye Art Museum, Sea le, WA

2001

“Made in California: Art, Image, and Identity 1900-2000,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

1999

“Portraits from L.A.,” Robert V. Fullerton Museum, California State University, San Bernardino, CA

“Painting: Fore and A ,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

Mark Moore Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1998

“Photographs,” David Aden Gallery, Venice, CA

“Examining Sexuality,” Marc Arranaga, Los Angeles, CA

1997

“Private Reserve,” Photo Impact Gallery, Hollywood, CA

1996

Rosamund Felsen Gallery, (curated by Michael Duncan), Santa Monica, CA

“L.A. Nude,” Photo Impact Gallery, Hollywood, CA

1994

“L.A. Nude,” Photo Impact Gallery, Hollywood, CA

“LAX the L.A. Biennial,” Otis Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1992

“Contemporary Figure,” (curated by Peter Frank), Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA

1991

“L.A. Nude,” Photo Impact Gallery, Hollywood, CA

1990

“Feminine/Masculine,” Christopher John Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

“Time,” Marc Richards Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

“Humans Being,” Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1986

“Issues,” Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1985

“Contemporary Monotypes,” Security Pacific Plaza, Los Angeles, CA

“Paintings/Invitational Candidate Exhibition,” American Academy & Institute of Arts and Le ers, New York, NY

“Perspectives,” California State University Northridge, Northridge, CA

1984

“Pastels,” Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“Seventeen Self Portraits,” Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA

“No Finish Line,” Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“From Los Angeles,” Eason Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

1983

“Figure Fascination,” Jan Baum Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“Monoprints from Angeles Press,” Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1982

“Domestic Relations,” Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“Four L.A. Painters,” The American Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

SELECT COLLECTIONS

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA

ADA Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA

Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles, CA

Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL

The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica, CA

Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York, NY

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

The Frances Young Tang Museum, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY

Fundación AMMA, Mexico City, Mexico

Hammer Museum, University of California, Los Angeles, CA

Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Sea le, WA

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX

The Mulvane Art Museum, Washburn University, Topeka, KS

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA

Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA

Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County College, Overland Park, KS

Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, Logan, UT

Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL

Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, CA

Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, CA

The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY

The Weatherspoon Museum, Greensboro, NC

The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

JOHN SONSINI

9 December 2021 – 29 January 2022

Miles McEnery Gallery

511 West 22nd Street

New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2021 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved Essay © 2021 David Pagel

Director of Publications

Anastasija Jevtovic, New York, NY

Photography by Christopher Burke Studio, New York, NY

Jeff McLane, Los Angeles, CA

Robert Wedemeyer, Los Angeles, CA

Pages 15, 17, 21 and 39: Image courtesy of the artist and Vielme er Los Angeles

Page 19: Image courtesy of Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, Museum purchase, gi of Agnes Gund, 2021.1

Color separations by Echelon, Santa Monica, CA

Catalogue designed by McCall Associates, New York, NY

Special thanks to Vielme er Los Angeles

ISBN: 978-1-949327-53-3

Cover: Josef, (detail), 2021