MARCH 2023 Vol. 23 | No. 1

CCKs & TCKs AMONG WORLDS

Cover Photo by Loic Leray (Unsplash)

Rachel Hicks

Copy Editor: Pat Adams

Graphic Designer: Kelly Pickering

Taylor

You are (figuratively) holding in your hands the last magazine issue of Among Worlds! In case you missed it, AW is moving from a quarterly digital magazine to our new website home! Check us out at amongworlds.com!

And what better way to celebrate our last issue than by wading into controversy? In this March 2023 issue, we’ve chosen to look more closely at the terminology used by and about third culture kids (TCKs), particularly as those terms relate to a broader category called cross-cultural kids (CCKs). CCK is a term that TCK researcher Ruth Van Reken came up with as she wrestled with why the feelings and identity issues of “traditional” TCKs seemed to resonate with others who had experienced significant crossing of cultures but had not, for example, moved to another country. In these articles and stories, we learn why TCKs are considered a subgroup of CCKs, which also includes bi- and multiracial children, international adoptees, children of refugees, and more.

We’re fortunate to have Ruth Van Reken herself kick off this issue with the story of “How CCK Came To Be.” Ruth’s piece explains the tension between definitions that feel exclusionary to some and those that open the “umbrella” so wide that terms are rendered effectively meaningless. Consider this piece one of our two anchor pieces in this issue, the other being Tanya Crossman’s “Cross-Cultural Intersectionality.” These two pieces help frame the issues for us, while the other contributors show us what those issues look like in their own stories about crossing cultures.

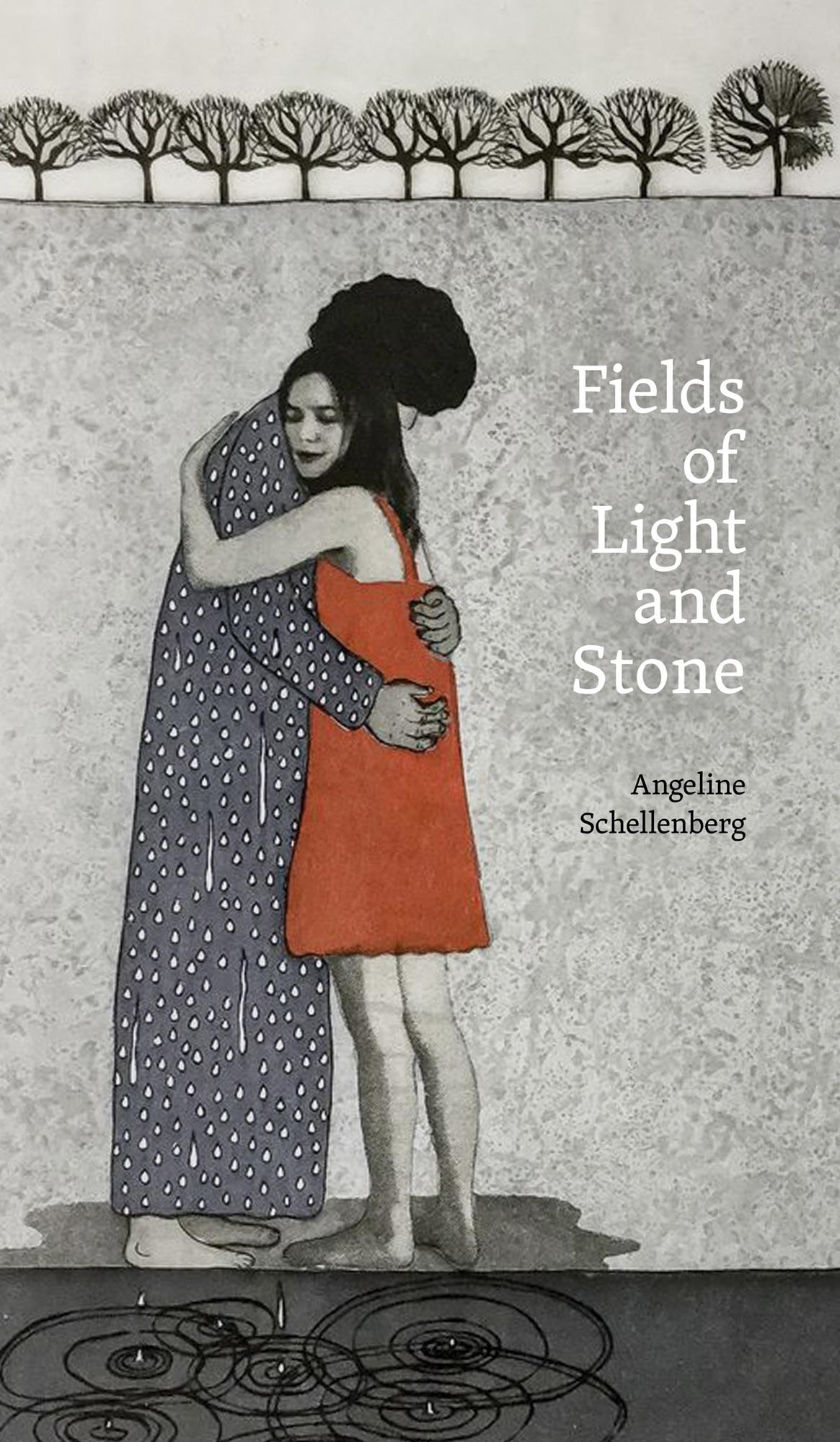

Editor’s Letter CCKs & TCKs Contents 1 Among Worlds How CCK Came To Be Ruth Van Reken Confusing Terms: Learning the Language of Cross-Cultural Experience Hannah Clark Maynard Hold Me Down Ina Grace The Guilt of Not Belonging Iona McHaney Marcellino That One Week in Paradise Claire Friesen Book Review: Fields of Light and Stone by

Cheryl

TCKs: A CCK Subgroup Zoe Krueger Weisel Everywhere and Nowhere All at Once Mayako Kruger One Move Too Many Christina Hoag Cross-Cultural Intersectionality Tanya Crossman Spotlight Interview: Maddie Thies Unexpected Treasures Katha von Dessien 5 11 15 17 23 27 31 35 39 43 49 57 Editor:

Angeline Schellenberg

Barkman Skupa

Digital

Publishing: Bret

March 2023 • Vol. 23 • No. 1

“No generation before now has had so many of its members simultaneously living in, between, and among countless cultural worlds as is happening today.”

- Lois Bushong (2013)

Among Worlds is on Instagram! Follow us at amongworlds.

The mission of Among Worlds is to encourage adult TCKs and other global nomads by addressing real needs through relevant issues, topics, and resources.

As Among Worlds transitions to our new website home (amongworlds.com), we hope you will join the conversation there! Among Worlds is the longest-running publication for TCKs, and that publication is just changing format. We’re excited to feature new stories, articles, poetry, photography, art, book and film reviews, and more by TCKs on a regular basis. In addition to new posts, like Iona McHaney Marcellino’s “The Loneliness of Being Unknown,” you’ll also find all of our past magazine content there, searchable by topic. As always, we welcome your submissions: check out our submission guidelines and details here!

Finally, be sure to join us on Instagram: amongworlds.

We look forward to hearing from you in our new space!

AMONG WORLDS ©2023 (ISSN# 1538-75180) IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY INTERACTION INTERNATIONAL, P. O. BOX 863 WHEATON, IL 60187 USA. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT THE PRIOR PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER. WE LOVE WORKING WITH INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS AND NGOS AND WILL NEGOTIATE A RATE THAT WORKS WITHIN YOUR BUDGET. CONTACT US AT AMONGWORLDS@ INTERACTIONINTL.ORG OR CALL +1-630-653-8780. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN AMONG WORLDS DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEW OF AMONG WORLDS OR INTERACTION INTERNATIONAL.

December 2022 2 Rachel

A TCK is an individual who, having spent a significant part of the developmental years in a culture other than the parents’ cultures, does not have full ownership of any culture. Elements from each culture are incorporated into the life experience, but the sense of belonging is in relationship to others of similar experience.

– David C. Pollock

How CCK Came To Be

By Ruth Van Reken

By Ruth Van Reken

5 Among Worlds

When I saw that Among Worlds had chosen to focus on “CCKs and TCKs” rather than “TCKs and Other CCKs,” I thought of Ecclesiastes 1:9—“there is nothing new under the sun.” The word and in the title makes it seem as if these are two distinctly separate groups. The word other indicates what they did write in the explanation of this topic— that TCKs are part of a greater whole of others who also grow up cross-culturally. But let me explain why I felt so weary with a “been there, done that” feeling when I initially saw the “CCKs and TCKs” theme.

Forty years ago, I knew I was a missionary kid (MK) but had never heard the term third culture kid (TCK). In 1984, a few months before the first International Conference on Missionary Kids (ICMK) held in Manila, my mother sent me a twopage article by David Pollock simply titled “Third Culture Kids.” That was my first awareness of that term, and while there were points of connection with it, some statements didn’t particularly resonate for me. I mostly put the idea aside.

When I attended that first ICMK, I don’t remember the TCK term being used much. All attendees came from the mission community and MK was a familiar, understood, and accepted term used in most sessions and private conversations as well. No problem.

By 1987 when the second ICMK convened in Quito, the TCK term had more visibility. Dave Pollock had begun to travel around the world to talk about the TCK profile of common characteristics he had noticed after many years of working primarily with young people who had grown up in other cultures due to a parents’ career choice. This was the same basic cohort of children Ruth Useem had studied during her time in India. For all the differences in details between different “sectors” of those living overseas for reasons of their careers—military, missionary, foreign service, and corporate— common themes began to emerge for how their

children responded to such a lifestyle of crosscultural mobility.

At that second ICMK the discussions on what our terms do and don’t mean began, and they are apparently still going on!

Some questioned the very concept of “the Third Culture.” How could there be some type of culture that had no geographic or ethnic boundaries? The discussions raged on about not only what the third culture might mean, but if it was even a legitimate name at all!

Many adult MKs who were there definitely did not want to lose the name they had always been called. One said to me, “I don’t want to be a TCK. MKs’ issues are too different and they [other TCKs] would never get us.”

Later, I realized many military offspring felt the same way about their original name. “We’re Army BRATS.* We don’t want to be TCKs.” This is what Janet Bennet called a sense of “terminal uniqueness.”1 They believed their story was so special no one else who had a story with different details could possibly understand them.

As time (and discussions!) went on, it became obvious there were other ways people were accompanying parents into other cultures for reasons other than the parents’ career. Dave Pollock became interested in the parallels of the TCK and refugee experience in his last years. He also noticed that some who had made many cultural moves within national borders also related to the traditional TCK profile even though they hadn’t lived internationally. The question then became “Do we let all of these people in the

“

Some questioned the very concept of the Third Culture.”

6

*BRAT most likely originated from 'British Regiment Attached Traveler,' referring to dependents accompanying a soldier enlisted in a regiment. March 2023

‘TCK club’ or not? What is the essence of what it means to be a TCK anyway?”

This is when what I might call the “turf wars” began. As different sectors finally began to agree that they were not only MKs or Army BRATS or whatever, but also TCKs in the sense of growing up as some form of “expat kids” like those first named as TCKs, they didn’t want to let others in. For TCKs, as for people of any specific background, it is often easier to identify by difference rather than likeness.

At the same time, still others said, “Let everyone in! Anyone who has interacted with many cultural worlds as a child for whatever reason can be a TCK.” While it was an appealing idea, the result would have been what Norma McCaig, founder of Global Nomads, cautioned years ago. “If you don’t define why TCKs accompanied parents into another culture, you cannot do research or properly understand any story as the variables will be far too many.”

She was right. Yvonne Kallane, a researcher on matters related to global family living, wrote me the following after a recent conversation we had on this matter.

“The major reason for construct clarity (n.b., having clear definitions) is that unless you have it, then you cannot compare studies… and advance the field. There needs to be some underlying baseline for who is and who is not part of the concept… and that needs to be rationalised over some period of time and then put out into the field for discussion and improvement… and then published…. I am starting to see a very clear picture now as to why TCK research does not have the rigorous base I had hoped to find it would. I am frustrated that after five decades since the Useems’ work that there is still no established construct that we all agree on about this in the academic research. 2

At the same time all of these endless discussions were going on about who was or wasn’t a “true TCK,” more and more people came to me after seminars explaining the TCK concepts and profile and made comments like, “I related to almost everything you said but I never went overseas. Why am I relating?”

When I would then ask them to tell me their story, there was always an overt or a silent crosscultural experience in that story. Maybe their parents were from two countries. Maybe they were international adoptees. Maybe they were from a minority community but went to school in the majority cultural context. I certainly wanted them to feel included in our topic and talks since it seemed they resonated deeply with the benefits and challenges of the TCK profile. But then we were back to the stuck points mentioned above. So, did they or didn’t they fit? And on what basis could we include or exclude them as TCKs?

Who knew? But in my mind this stalemate needed to be broken because we were beginning to miss the forest for the trees.

The emerging reality was that something much bigger than what we had considered was happening in our world. In 1984 at the first ICMK, sociologist Ted Ward had remarked that MKs (then extrapolated to TCKs later) were the prototype citizen of the future. It seemed that time had now come. But how could we look at what was going on and use what we had learned to examine these global shifts if we were still stuck in fussing about the TCK language?

To be honest, I felt rather boxed in. How could we move to future explorations if we were stuck in the past conversations?

After a particular incident in a local school where the administration there proudly showed me what they considered a “multicultural program”

7 Among Worlds

“

To be honest, I felt rather boxed in.”

but that had no understanding for what I meant by TCKs, I decided something had to change… at least for me. I needed to find a both/and way to look at things, not this either/or choice I kept encountering.

The next day I returned to the school and said “How about if we change the language from TCK or ‘multicultural’ and use new language so all of us have to consider what we are talking about rather than assuming we already know? Let’s try ‘cross-cultural.’”

And it worked! I simply said CCKs were those who had grown up meaningfully interacting with two or more cultural communities for whatever reason. It did not depend on a parent’s job or where geography did or didn’t take them. Simply that they had grown up amid many cultural worlds. This is the basic model that began that day.

not change presidents, types of currency, etc., in the moving. I wrote my first article explaining this new model in the Intercultural Management Journal in 2005 with my friend, Paulette Bethel.3

In order to better assess what were the universals creating this strong emotional sense of connection between CCKs of all groups and what might be the distinctives in their responses that was sector or subset specific, I called the TCK cohort initially studied by Useem and Pollock “traditional TCKs.” I named those who had made the cross-cultural moves within their own country “domestic TCKs.” It had nothing to do with ranking if one was better or more prestigious than the other. I simply wanted to know if it made a difference in outcome if you did or did

Immediately after the seminar in which I first displayed the CCK model, the magic happened. Without long discourse, people saw where they fit. Some came up to tell me they had just recognized the cross-cultural aspect of their story and how it explained so much—similar to the many times traditional TCKs had told me of their “Aha!” moments in the past. I was a happy camper!

The bigger surprise, however, came when someone asked if you could be in more than one circle at the same time. While I had thought of these as separate experiences, this person said she was in five circles right off the bat!

Wow! The window to looking in fresh ways at what was going on in our globalizing world had begun to open! I had never thought of how this model might reveal the increasing cultural complexity so many in our world now experience. Unlike my “simple” TCK story of yesteryear, I soon realized many traditional TCKs were also in multiple other circles as well. It became clear as I listened to all these disparate stories that the themes of identity confusion and loss of a sense of belonging we talk about in traditional TCK circles were common for virtually all CCKs.

March 2023 8

The Cross-Cultural Kid (CCK) Model

The question then is why? Is there something about growing up cross-culturally for any reason that creates these voids? If so, what is it and what can we do to help ameliorate that internal sense of isolation many have? In the traditional TCK studies, we link our losses and resulting unresolved grief to frequency of mobility and losing our worlds. Most CCK circles seem to identify with hidden loss and grief, but they may not relate to physical mobility. Are there other themes here we can explore? How can we also identify and build on common gifts such as using cross-cultural skill sets, being potential cultural bridges, thinking outside the box, and so on?

To look in more depth at those questions, it also became clear we needed to consider how different details of each group could also shape their stories. I realized I had been a minority growing up in Nigeria, but mine remained a position of privilege, where that is not true for all minorities. Growing up in a faith-based system rather than a military system meant how I did or didn’t practice that faith as an adult would influence how others in my community saw me in a different way from how the military or corporate child might be perceived.

Whether children of immigrants physically resemble their new country or not may or may not intensify their sense of belonging or sense of alienation. For me, taking the many things I have learned in studying the traditional TCK “petri dish” and the common characteristics that come from growing up with a cross-cultural lifestyle and one with high mobility resulted in the most common challenges being questions of identity and unrecognized and unresolved grief. Each circle in this updated model can add more so researchers

can try to better understand what factors do or don’t matter in creating both the commonalities and the things unique to that subset.

For example, under Children of Immigrants, were they born in the new country? Do they look similar to or different from the dominant culture in which they live? Depending on that, how/is their sense of identity affected? And so it goes.

To me this was the next logical step up the ladder in the TCK chain. It made life so simple for me and so expansive to keep growing in all I saw happening around me in so many new ways and places. It helps us join our understandings from the TCK world to what others are learning in their groups. If we are all in the same basic circle, we can gather for these wonderings. I felt I could finally run towards this goal instead of limping to get there.

But in the last couple of years, it seems the same patterns of long ago are being repeated. I see the same resistance that MKs or military kids (or other sectors of TCKs) expressed to me about not wanting to be TCKs playing out in that TCKs are now resisting being part of the CCK circle. I have been told I am an elitist as I simply don’t want to

9 Among Worlds

This model might reveal the increasing cultural complexity so many in our world now experience...”

“

The Cross-Cultural Kid (CCK) Model Expanded

share the TCK label with others of less privilege. Others tell me it is simple: just let all your CCKs be TCKs and then the issue is over.

For sure I am not trying to keep anyone “out,” but if you say all can be named as TCKs, then please tell me how you define “third culture” in this overarching context. Maybe there are better words than either TCK or CCK to name what is going on globally. In the name of “construct clarity” we need to figure out what we are talking about before we can say who we are talking about.

So yes, I felt tired when I saw the topic raised once more. I keep hoping we can move ahead and past these circular (to me) discussions of the past forty years. There is so much that is amazingly interesting to think about and learn about as our world changes. Why are we so seemingly afraid to take what we have learned from our stories and journeys and join with others to explore it all? Bottom line, I simply don’t understand why it seems so hard for TCKs to agree they are also CCKs anymore than I understood why my MK friend of years past didn’t want to be a TCK. What is the loss of being both/and rather than either/or?

But I will wait to see what others say here. Perhaps this will be a most insightful process of comparing and contrasting the stories in ways that fulfill my dream of understanding more. I hope so. Just because something feels like how it has been doesn’t mean it is. I knew at the beginning of creating the CCK model that I might not live long enough to fulfill the dream of organizing a cross-disciplinary, cross-experience gathering where researchers into each of these subsets would gather and share their wisdom and see what common themes or distinctives arise from an academic approach as well. And who will consider what happens developmentally to a child who is in many of these CCKs circles all at the same time? Maybe some of you will be those folks who take the topic on. It really is an interesting, thought-provoking world, and we are part of the discovery process as we discuss how

this impacts us all and how we can be positive change makers in the process. Have fun!

Ruth Van Reken is a second-generation third culture kid* (TCK) and mother of three now-adult TCKs. She is co-author of Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds, 3rd ed., and author of Letters Never Sent, her personal journaling seeking to understand the long-term impact of her cross-cultural childhood. For more than thirty-five years (pre-COVID19!) Ruth traveled extensively speaking about issues related to the impact of global mobility on individuals, families, and societies. Since 2001 she has expanded her interest to work with those she calls cross-cultural kids (CCKs)—children who grow up cross-culturally for any reason. She is co-founder and past chairperson of Families in Global Transition. In addition to her two books and many articles, she has written a chapter in other books including Strangers at Home, Unrooted Childhoods, and Writing Out of Limbo. In 2019 she received an Honorary Doctor of Letters degree from Wheaton College for her life’s work. She now lives in Indianapolis, Indiana (US) with her husband, David.

References

1 Schaetti, Barbara. Phoenix Rising. A Question of Cultural Identity. https://transitiondynamics.wordpress. com/resources-and-products/articles-and-publications/ phoenix-rising/

2Yvonne Kallane, personal email, January 11, 2023

3https://eurotck.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ etck_2013_cross_cultural_kids.pdf

March 2023 10

*A child who spends a significant period of time during his or her developmental years growing up in a culture outside the parents’ culture.

11 Among Worlds

Confusing Terms Learning the Language of Cross-Cultural Experience

By Hannah Clark Maynard

As I was growing up as a third culture kid, my mom was always on the hunt to find spaces where I would “fit in.” I went to missionary kid camp, I attended an international student youth group, and I went to TCK homeschool conferences. She was always wanting to find other people who were like me. As soon as she learned the term TCK, she started trying to see everything and everyone from a TCK lens.

“You know, TCKs are more than just missionary kids and military brats,” she would say. “I mean, think about it: your cousin (adopted from China into an American family) is a TCK. The refugee kids on the news are TCKs. Children of immigrants are TCKs. It’s a much broader term than I thought.”

While my mom had the best of intentions, whenever she would share with me another group of people she categorized as TCKs, I usually felt a little confused and uncertain. After all, I did have a lot in common with some of these people. I knew what it was like to have to balance more than one culture, to know when to speak a certain language or when to express different

cultural norms. I had experienced standing out or not fitting in due to my background.

However, I always felt like something was different. I have never experienced being displaced the same way a refugee child has. I have never known what it is like to be adopted, let alone be adopted by someone who has a different country of origin than me. And those people do not know what it is like to walk in my shoes either. In Thailand they would use the phrase, “Same, same…but different.”

This led me to do some research on what exactly a third culture kid is. Sure, I knew I was one, but who else was in the same boat? After doing the research, the definition from Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds, 3rd Edition caught my eye:

A traditional third culture kid (TCK) is a person who spends a significant part of his or her first eighteen years of life accompanying parent(s) into a country that is different from at least one parent’s passport country(ies) due to a parent’s choice of work or advanced training.

March 2023 12

This was it. This was me. I had spent a significant part of my first eighteen years overseas. My experience occurred while my brain was still forming. While I appreciate the good intentions of many adults who have tried to understand the TCK experience, there is a reason it is TCK (third culture kid) and not TCA (third culture adult). This experience is so important because it happens during the formative years of one’s life, while they are still creating their views of the world, their personal identity, and their literal knowledge of how things work. This is not to undermine the experiences of those who move overseas as adults, but it is to signify there is a significant difference in experiences for kids who move and live internationally.

We went to a country (actually, we ended up moving to more than one) that was different than my parents’ passport country. Instead of learning to cook casseroles, I learned how to cook in woks. Instead of watching American football, I learned what “real” football was. My childhood was going to be very, very different from the way my mom and dad were raised.

The other important part of this definition that stood out to me was the fact we moved because of my parents’ choice of work. They already had a job when we arrived overseas. They were moving there for a reason, with specific intentionality. It was not because they were being forced to move or because they wanted to start a better life somewhere else. They moved because they chose a new job in a different country.

When processing this definition of a TCK, I knew this was me. It was more than just a definition for me though, it was a part of who I was, part of my story. But if this was who I was, what word should I use to describe my internationally adopted cousin, the refugees I learned about on the news, the children of immigrants, or any other group that may have similarities to me as a TCK?

This is when I discovered the term CCK (crosscultural kid). Ruth E. Van Reken, in her book Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds defines cross-cultural kids as the following:

A Cross-Cultural Kid (CCK) is a person who has lived in—or meaningfully interacted with—two or more cultural environments for a significant period of time during developmental years.

“Accompanying parents”—this part of the definition meant that I was not merely a study abroad student. This was a familial experience. I was not the only one undergoing changes and transitions. We were going through it together as a family unit. We were all learning to live away from extended family, our home church, and even Chick-fil-A.

The broad umbrella term describes TCKs and others who understand what it is like to walk the tightrope of knowing more than one culture. However, TCKs have been categorized as a subgroup of CCKs. We know what it is like to have to struggle with identity issues due to interacting with more than one culture in a meaningful way. We know what it is like to try

13 Among Worlds

to find the identity balance in our formative years of brain development. However, there are some distinct differences that create the subgroup of TCKs. This means that all TCKs are CCKs. However, not all CCKs are TCKs.

Therefore, knowing I am a CCK helps me realize I can connect with people who come from all kinds of different backgrounds in a meaningful way. However, knowing I belong to the TCK subcategory helps me find people with similar stories easily. Finding other people “like me” has its benefits. And, just like my mom, seeing things from a TCK lens can help me see some of own strengths and weaknesses.

While these terms are not my sole identifying factors, they are important to me. As Michael Pollock once shared about using the terminology of TCK on the podcast TCK Care, “It really is an ongoing conversation.” Because every person has their own story, labels can sometimes help and sometimes hurt. However, it is extremely beneficial to me to have the vocabulary to start this ongoing conversation.

Hannah Clark Maynard has lived in seven states and three countries (including two in East Asia). Using her experience as a TCK, she now trains, debriefs, and works with teenage TCKs professionally in Virginia, USA.

March 2023 14

“

Because every person has their own story, labels can sometimes help and sometimes hurt.”

Ina Grace is a triple citizen (American, Filipina, Spaniard), who has also lived in Germany, Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden. She dedicates herself to the art of homemaking, which involves both planning and administering domestic affairs as well as monitoring the healthy development of family dynamics in her home. She’s a philosopher at heart, always interested in the “why” of things. happianywhere.com

15 Among Worlds

Hold Me Down

Ina Grace

A river, though it slows, It always passes by And are the blueish hues its own Or borrowed from the sky?

A piece of clay can take a shape, And then so many more And every wall that bears a paint What is it, at its core?

And those who knew no home to last New form to fit new place Ceaselessly forever ask Which roads they must erase

Which strings are those that I must cut And from my heart renounce And will there after be enough To ground and hold me down

If I let go

What I hold close Will there still be Inside of me

Enough to hold me down?

March 2023 16

The

17 Among Worlds

Guilt of Not Belonging

By Iona McHaney Marcellino

Every April, our mission board used to have a meeting in South Africa. A team from America would volunteer to come and teach the children whatever programme had been used for their Vacation Bible Schools the previous year.

One year the theme was “Route 66 – A Road Trip Across the United States.” It was a pretty glamorous theme. My friends and I were used to road trips across Sub-Saharan Africa. Some of them rode with their families for two or three days to attend these meetings. I was used to road trips in Angola being halted and rearranged due to de-mining fields or washed out log bridges or Marburg outbreaks.

A roadtrip across the US, even an imaginary one, must be just as exciting.

We wore t-shirts, gorged ourselves on American candy, and made key chains designed like little license plates. We listened to the song “Life is a Highway” every day and watched the movie Cars at the end of the week. We practiced a song called “Route 66” with some vague message about finding God along the way. I had no idea what Route 66 was. I didn’t know I was even

March 2021 42

The

March 2023 18

Often, TCKs minimise because we have to survive.

singing about a real road; the roads in Angola did not have names. But it was fun to sing and it was fun to be a part of something—until I realised I wasn’t a part of it at all.

During one afternoon, the American volunteers brought in a massive map of the United States. Each state was outlined, and pictures of the state flowers or landmarks stood out in bright colours. Route 66 (I guess it really does exist) was a solid orange line with a little van to represent our “journey along the highway.”

They handed out stickers to us and said cheerily, “Okay, put the sticker where you were born so we can see which states we are all from!”

I stared at them. I stared at my sticker. I stared at my friends.

My friend next to me stared back—he was born in Botswana. He looked at his brother, who had been born in South Africa. I shot a look at my best friend’s younger brother, who was also born in South Africa. Then I looked around at my other friends: Zimbabwe, Western Europe, Mozambique. I couldn’t see where we were going to put our stickers.

I raised my hand; something had been overlooked and the adults needed to know.

“I’m sorry, but I can’t put my sticker on the map.”

“Oh, sweetie, you can! Tell me where you think you were born and I’ll help you find it on the map!”

I stared some more. The incredulity was astounding. As a ten-year-old, I didn’t know a lot about the world, I didn’t know where Route 66 went, I didn’t know the references made in the film Cars, and I didn’t know what a zip code was, but I knew where I was born and I knew the Royal Infirmary of Perth, Scotland, UK, was not going to be found on a map of the United States.

“Where I was born is not on the map,” I said politely.

“Well… where do your grandparents live? Were you born near them? I can help you put the sticker there!”

19 Among Worlds

“

Where I was born is not on the map.”

“No—I wasn’t born in the United States.”

The volunteer stared at me, eyes widening. “But you’re American, sweetie, so you just need to remember where you born—not where you live now!”

“I was born in Perth, Scotland.”

More stares. My friends added their voices.

“I was born in Gaborone!”

“I was born in Johannesburg!”

“I was born in Mozambique!”

Eyes widened even more.

In that moment, I felt sorry for this American volunteer. She had run this whole VBS programme in her home church where all the kids were probably born a few counties apart. She didn’t know that she was being sent to teach the same programme to a bunch of kids who would mess up all her activities on an international scale because of where their parents decided to give birth.

And, yet, there it was. That niggling feeling of shame. Guilt with no cause. A feeling I was aware of and familiar with—because this was not my first encounter with Americans who did not understand me.

We all felt it. The mis-belonging. The mis-placing of ourselves and the utter inconvenience we caused the volunteers. We didn’t mean to—we were children—but we could see it. We weren’t so much in the way as just extra afterthoughts on a page, no one quite sure what to do with our answers. No one quite sure what to do with us. I’ve encountered this same misplaced guilt and unintentional inconvenience throughout my life as a TCK.

It’s in the long pause when I answer someone’s question, “Where are you from?” I can tell they

are taken aback by my response; it’s not what they wanted. Most people want a one-country answer, not a seven-nation saga.

I see it in the frustration of friends and family who are not TCKs and don’t know what it means for me to “not be American” or not feel at home in one place or another.

There is hesitation at every introduction. Do I bore or overwhelm this person with the truth, or do I minimise my life for their comfort?

Often, TCKs minimise because we have to survive. We know that we require community, and to have community we need to be tolerated by other people, and in order to be tolerated we cannot keep overwhelming or correcting other people with our multicultural identities. We simply have to assimilate and be who they expect us to be: American, British, Kenyan, or any other nationality that fits on their map.

And in this assimilation, we lose a lot of ourselves—not always in a drastic, self-effacing way but in a quiet “Oh, this bit of me doesn’t quite fit here” way. Sometimes that “bit” is our second language, sometimes it’s our politics, sometimes it’s our favourite books or hobbies, sometimes it’s all of our childhood memories, sometimes it’s our high school experiences.

March 2023 20

It’s difficult to feel like you belong when everyone is sharing their stories of driving to Sonic with their friends after high school and you mention that after school you and your friends ran alongside abandoned train tracks in the Rift Valley, watching out for gunmen. Or that your school trips were to climb Mount Kenya while your university peers went to SeaWorld.

It’s difficult to belong when your peers talk about their favourite shows and ask you what you watched growing up. You respond that you had no electricity so you often watched the lizards running back and forth on your concrete wall.

It is difficult and self-estranging. The conversation is immediately doused and the participants forced to stand about in awkward silence. So, we TCKs minimise our stories. We preface our stories with the disclaimer, “Oh, my life wasn’t that different! I understand life here too!’

I’ll confess, we’re lying through our teeth. But the guilt of lying is somehow more comfortable than the guilt of being an inconvenience, the guilt of not belonging. We alter our stories to make our audience, friends, family, peers, or dates more comfortable and more likely to stick around for the long haul.

We need community and often we’ll do anything to secure it.

Tapering our stories is a skill TCKs learn at a young age; adapting to our environment to maintain acceptance is natural. But what I don’t think is understood by those around us, and what is so keenly felt by the TCK, is the very guilt of simply having a TCK existence. An existence that wasn’t our choice, but one with consequences we feel acutely. An existence that we will have to explain and compensate for over and over and over and over again (and again). An existence that will not be understood, or accounted for, or given space. We are required to give grace repeatedly for those misunderstandings.

Because if we don’t, we’ll be isolated.

Is this guilt just another part of the TCK identity? Is this just another aspect of ourselves that we all need to come to terms with? We carry the responsibility of calibrating our conversations for others. We carry the weight of extending grace when we are misunderstood, mis-remembered, and mis-placed.

In the end, the volunteers put our stickers on a blank piece of paper. We wrote our names and our birthplace beside each sticker and the paper was taped to the edge of the map. We were there, but we were distinctly separate from their world. We were outsiders, our existence denoted on a blank sheet of paper labeled Other, even though Other included the entire world beyond the USA.

It didn’t feel good. We sat there and listened to someone talk about birthplaces and states and I’m sure they tried to tie it to Christ and the Church. I sat and stared at my sticker, an afterthought barely attached to the giant map of the United States.

Looking back, that sticker represents a lot of my relationship with the US. I should belong there.

21 Among Worlds

I really should, but I absolutely don’t. The best I can do is find a place on the peripheral edge and cling on for dear life, hoping no one asks too many questions or shakes the map too hard or else my fragile American-ness will fall clean off.

I really did feel sorry for that one volunteer. Even at ten, I had a keen awareness that my friends and I were living a very different sort of life. I knew we had to be gracious to the volunteers, that we had to show an inordinate amount of understanding for our age, because we had access to a concept they didn’t.

You can be American and not born in the USA.

But, because I was a child, I also remember thinking adults really are not that smart and American volunteers don’t know very much about missionary kids except that we don’t have access to American candy. Churches that send teams abroad should be aware of this before they head out to serve missionary kids.

For the sake of the children you’re serving, bring on the sour Skittles and leave your one-nation maps at home.

Iona McHaney Marcellino is a nurse and an avid writer of prose, poetry, and short stories. Born in Scotland and raised in Angola, she now lives in Cambridge, UK with her husband and daughter. Iona enjoys connecting with other TCKs and global nomads to discuss the nuances of this varied, international life.

Iona’s website

That One Week in Paradise

By Claire Friesen

When I was twenty, my childhood best friend, Hannah, and I returned to the Philippines, our childhood home. I’d had it rough my first semester of college, and had decided to take some time off school and go back to where I’d grown up to reset, and to experience the Philippines anew as an adult. Hannah and I moved back to Manila at the end of 2010 and lived with some family friends, who graciously opened their homes and their hearts to us during those six months.

We both volunteered at a children’s home founded by a family that attended the same international school we’d attended for so many years. During our six months volunteering, we got to know some of the women who took care of the children there. One of these women was Gloria, a social worker who worked with the children’s home as well as the school run by the same mission.

One afternoon, Gloria casually invited us to visit Negros, her hometown. Negros is one of a

number of islands in The Visayas, located in the middle of the Philippines. She invited us for a week in March, and told us her family would be happy to have us stay with them. I was hesitant at first, partly due to the price of the plane tickets, and partly because I’d never met anyone in her family and didn’t have any idea what to expect. But after talking it over with Hannah, we decided to go.

Looking back, I can confidently say that our week in Negros was one of the best weeks of my entire life. Our time there was pure magic from start to finish. What first comes to mind when I think about Negros is the natural beauty that breathes from the soil. Tall, swaying palm trees lined the dusty roads. Distant mountains framed intensely green rice fields, and the ocean tides swelled and retreated just beyond the town limits. I remember thinking to myself on more than one occasion that week, “This has to be what heaven looks like.”

But it wasn’t just the natural beauty that caught my breath. When Hannah and I arrived in Negros

23 Among Worlds

with Gloria, we were instantly greeted with the type of hospitality that makes Filipinos so loved around the world. Gloria’s sister Marie hugged us and offered us her room for the week. Her sweet mom and aunt greeted us and treated us like family from the moment we first walked through the door. And it wasn’t just Gloria’s immediate family that welcomed us with such open arms. The entire community showed up at their doorstep to meet us. We all ended up spending hours and hours together, and it felt as if time didn’t exist during that week. There was an ease, a sense of happiness and contentedness everyone oozed effortlessly, the type of feeling most people spend their entire lives searching for.

A friend group made up of guys our age, who called themselves the Taroroy Barkada, took it upon themselves to show us around and give us the full “Negros experience.” On our first day exploring Negros, one of the guys in the group brought along a bolo and lopped off stocks of sugar cane for us to try. They climbed coconut trees and cut down fresh coconuts for us. We drank the buko juice straight from the coconut and then scraped out the meat with pieces of the shell. One day we all piled into the back of a pick-up truck and drove to a waterfall tucked away deep in the mountains. We spent the day there swimming, jumping off rocks, and eating picnic lunches.

On another day, the entire community piled into boats made of bamboo riggings. We glided down a narrow river that eventually fed into the ocean. The water was clear-green, and lapped quietly against the shore. But there was no one else around. This perfectly beautiful spot was all ours for the day. The guys immediately got busy catching crabs and fish with their nets, and sometimes with their bare hands. They cooked the fish they’d caught over open fires on the beach and we all ate like royalty.

Despite all the amazing adventures we had, my very favorite memories are of the nights spent singing karaoke. At least three nights during that week we all gathered at Gloria’s family’s house. Someone had rented a karaoke machine for the week, and we set it up in the living room. Karaoke is as much a part of Filipino culture as tininkling (a traditional dance that uses two bamboo poles) or the clay piñatas that are ubiquitous at birthday parties. Even if you’re shy in most circumstances, you will sing your heart out into a microphone. You’ll probably be horribly out of tune, but it won’t matter because everyone will laugh and cheer anyways. I lost all my inhibitions in front of the mic. We’d all had a couple beers, so that probably helped loosen us up a bit, too. Hannah and I would choose sickly romantic songs to

March 2023 24

sing and classics like “Kokomo” that, to this day, remind me of my time in Negros.

However, the real karaoke star in the community was Ken. People literally called him “Golden Ken” because of his beautiful voice and the pure confidence he exuded when singing a ballad. Ken and I had a short island romance that lasted the duration of my week-long vacation. The only real issue was that we barely spoke any words of the same language, and I was over six inches taller than him. But at the time, those things didn’t matter. To me, Ken wasn’t just from Negros. He was the embodiment of it. He knew how to jimmy his way up palm trees and cut down coconuts, and he could catch crabs with his bare hands. He knew how to get to the most beautiful spots on the island, and he could drive a tricycle (a motorcycle attached to a sidecar—one of the most popular forms of transportation in the Philippines). And most importantly, he knew how to sing.

his performance, someone else would grab the mic and we’d start all over again.

I can’t explain what that experience was like. It seemed other-worldly to me. A few days before, the people crammed into the living room had been complete strangers. Now I felt inexplicably connected to all of them, comfortable and unembarrassed, swaying and laughing and scream-singing like nothing else in the world mattered.

Sometimes when I look back on that week it seems almost too perfect, surreal, something that couldn’t actually happen in real life. Life lived in Negros was so simple, so natural. Nobody was ever in a rush. Nobody seemed stressed or caught up in their own worries. Everyone just spent time together and laughed and explored. They knew how to just be , in a way that astounded me. Maybe I’m looking back on my time there with rose-colored glasses… but I’ve always felt this sense of wonder knowing there is a place in the world that is full of so much joy, so much natural beauty, and a community that genuinely looks out for each other the way family does.

On those karaoke nights in front of the entire community, Ken would grab pink plastic roses out of the vase by the TV and dramatically present them to me as he sang his heart out to the most heart-felt of romantic ballads. The song titles that come to mind are “Breathless” by the Corrs and “Closer You and I,” a classic Pinoy karaoke favorite. Everybody would laugh and cheer and sway to the music, and when Ken was done with

I have to admit, I’ve had moments in the last eleven years since then when I wondered what it would be like to move to Negros. What would it be like to “go off the grid” in a sense, to live a simple life surrounded by palm trees and the ocean, taking regular rides in the back of pickup trucks, and singing karaoke with abandon? Maybe what makes those memories so special to me is the fact that they don’t happen in regular, day-to-day life. Either way, one day I will return to Negros. This time though, I’ll return with my husband. And the little girls that showed Hannah and I all the nooks and crannies of the island will be full-grown adults. A lot of things will have changed. But I’m sure some things will be exactly as I remembered.

25 Among Worlds

Claire Friesen is an American who was born in the Philippines and grew up there. She currently lives in Argentina with her husband and teaches ESL to adults. She loves to travel, draw, and write about her lived experiences as a TCK.

https://www.facebook.com/claire.friesen.7

https://www.betweenworlds.blog/

March 2023 26

27 Among Worlds

A Review of Angeline Schellenberg’s Fields of Light and Stone

By Cheryl Barkman Skupa

The title of Angeline Schellenberg’s book of poetry comes from the names of two villages—Lichtfelde and Steinfeld—in the Molotschna Mennonite Colony, which existed in the Ukraine from 1804 until the end of World War II.

Schellenberg, as well as many other Russian Mennonites (including me), trace their origins to either the Chortitza or Molotschna colonies, which were formed when Catherine the Great invited Mennonites from Prussia as well as other Germanic peoples to the empire to farm the vast Russian steppes. There, Russian Mennonites, such as Schellenberg’s grandparents, endured the uncertainty of the last days of the czarist rule, as well as the increasing chaos as waves of the Red Army, the White Army, and the independent army of anarchists swept through the land. Schellenberg’s poems speak of this specific immigration to the steppes, then the desperate escape to Canada, just two of the many relocations the Mennonites have experienced over the centuries. Yet the book also bears witness to the universal immigrant experience.

In the poem “Everything There Is to Say,” Schellenberg writes:

The Siberian elms (like my ancestors) would not stay in one place; they sent defiant seeds searching for a home on distant lawns and under foundations, resistant to tugs. And every time I tore from my wooden house in tears, ran for the border between fields—my shelter belt—everyone knows what the aspens whispered.

The major themes of most CCKs (including TCKs) are prominent in this book: the search for home, the longing for shelter, and the outsider’s precarious existence in the metaphoric “border between fields.”

Schellenberg’s poetry tells this story with a strong sense of place. We see, hear, smell, and experience both the Russian farm life as well as

March 2023 28

farm life on the Canadian prairies. It is ironic that many of these immigrants were farmers—tied to the land with its rhythms of days and seasons as a source of livelihood, yet invariably moving to a new place when faced with new waves of misunderstanding, persecution, or economic opportunity.

Some of the poems deal with deeply human experiences of imperfect people; in fact, Schellenberg begins the book with a dedication “For all those who seek comfort in story with love for these imperfect saints.” And these human and imperfect stories are apparent in poems such as in “Threads,” where she writes,

You lie awake, needlessly fingering this patchwork guilt.

Remorse, a code you live by; distress calls for someone to blame.

Schellenberg evokes the poignant scene with “patchwork guilt” in place of the words, “patchwork quilt,” something I didn’t catch the first time I read it.

Some of Schellenberg’s poems have touches of humor. In the poem, “Beckoning Hills,” she writes, “your small-town museum saves / one-hundred kinds of barbed wire / a wall of sexy salt shakers.” From there she moves to the more serious item, “the nose / from a cannon projectile sent home / with Norman Gordon’s personal effects,” and then back into the ridiculous: “recovered from turkey gizzards at the poultry plant / this display of rusty nails / white stones / and dice.”

When I reread the book for this review, I saw it not only as historically interesting, but I also saw it in light of current events in Russia and the Ukraine. In the poem, “As We Left They Sang,” Schellenberg writes of the troubled years of 1910–1924: the invading armies, the pillaging, the hunger, the struggle to survive, the things which often have fueled and continue to fuel relocation, upheaval, immigration. Schellenberg writes:

1.

The day they took him

It was muddy.

Children, this time only prayer will help…

2.

October. Black troops stronger than White chop off limb by limb.

47 Among Worlds

29 Among Worlds

“

Schellenberg writes of the things which often have fueled and continue to fuel relocation, upheaval, immigration.”

November cannons. Cossacks to disband the Black.

Christmas night, give food and lodging for the Red.

We had traded with the Cossacks for some sugar, But they took it all away. . .

3.

The second floor once used to store grain The remaining kernels.

Things hidden. Our wedding bands. We lay down so we wouldn’t feel our hunger. Potatoes the size of hazelnuts. . . .

4.

Our big dog Woljshanck and our little dog Damka and everything dear to us stayed back.

As we left, they sang, Jesus, go before us. Tears as our train took us away.

It seems this poem summarizes in short succinct form the dark days of life which preceded a desperate decision to rip up roots and emigrate to a new country.

Though this book of poetry can at times present an intense reading experience (poetry is, after all, powerfully condensed), it also is imprinted with the struggles and joys of a child of immigrants, intent on understanding the experiences of those who left all they knew to start over in Canada. The book is inspired by genealogical information, old love letters, notes from the poet’s grandfather’s German Bible, and her own memories. And central to these experiences is the two worlds that all children of immigrants must straddle while interacting with parents and grandparents. I read the book, in part, to understand my own family’s immigrant experience.

Angeline Schellenberg has another book of poetry titled Tell Them It Was Mozart. You may read more about her on her website.

Cheryl Barkman Skupa grew up in Brazil, and has taught English in the People’s Republic of China. She’s also spent many years teaching high school and college English to both native and non-native speakers.

March 2023 30

TCKs: A CCK Subgroup

31 Among Worlds

By Zoe Krueger Weisel

Despite growing up the child of two adult TCKs, being raised bilingual, and holding multiple citizenships, by strict definition of the term I am not a third culture kid. I was lucky enough to grow up in a stable environment. I was able to spend my childhood, attend local schools, and make friends in one single place—a place where my parents still live today and which I can confidently call home. Nevertheless, like many other people with cross-cultural backgrounds, I relate to TCK research. When considering that TCK research provides a prototype in understanding other cross-cultural kids (Bonebright 2009), it comes as no surprise that we CCKs may struggle with our sense of identity and belonging in similar ways to TCKs.

With this in mind, sociologist Ruth Van Reken coined the term cross-cultural kid (CCK) in 2002 as someone who has lived, is living, or has meaningfully interacted with more than one culture while growing up (Pollock et al. 2017). Expanding the term to cover all kinds of groups of international children (including TCKs) would give “a clearer vision of the growing complexity many children face as they try to define their own identities and sense of belonging” (Van Reken and Bethel 2005).

Still, the TCK experience remains unique, which is why it is important to understand what makes third culture kids distinct from other crosscultural subgroups. In Third Culture Kids. Growing Up Among Worlds, the authors explain that there are four key factors that play into being a TCK. The first, expected repatriation, means that unlike other CCKs, children growing up in the Third

March 2021 42

Not all CCKs are TCKs. But all TCKs are CCKs.

March 2023 32

Culture are eventually expected to return “back” to their home or passport country. This may be determined by their parents’ career or may happen once TCKs become adults who return home for higher educational or career purposes.

The second factor, distinct differences, refers to the fact that “whether or not they blend in by appearance, TCKs often have a substantially different perspective on the world than their local peers simply because their life experiences have been different” (Pollock et al. 2017). No matter where TCKs live or what environment they are in, they will always be distinctly different from the people surrounding them, even if not obvious at first glance. Since TCKs grow up in between cultures in a way that almost no one else around them does, every TCK’s experience in itself is a unique one. Even though TCKs often externally fit the mold and do not immediately stand out as foreigners, they may internally feel different from the people surrounding them, just like a traditional immigrant would. This is where the term hidden immigrant becomes relevant, as it describes a TCK as someone who “looks like those in the dominant surrounding culture but thinks quite differently”

(Van Reken and Bethel 2005).

(Van Reken and Bethel 2005).

The fact that the families of TCKs usually move by choice, motivated by better career and job opportunities, leads us to the third point, which is a privileged lifestyle. This goes back to research conducted by the creator of the TCK term herself, Ruth Hill Useem, who found that Americans living in India enjoyed “higher prestige and status than they do at home” (1963). Many different perks stem from the Third Culture way of life, with the first being that TCKs get to experience travel and explore the world at a much younger age than their peers. They are also granted privileges by the family’s sponsoring organization, such as purchasing food from a commissary on a military base, or having a chauffeur to drive them to school (Pollock et al. 2017). Educational and financial advantages are usually related to the Third Culture experience and TCKs generally tend to belong to higher social classes than their peers both in their home and host countries, outside of the Third Culture.

The fourth and last factor distinguishing TCKs from other CCKs is their system identity, which determines how much a TCK tends to identify with the system, or institution, in which their expat parent works. According to research “[i]n the third culture sponsor can define you as much

33 Among Worlds

as nationality” (Cottrell 2007). When it comes to system identity, it is important to understand that TCKs and spouses who accompany their significant others abroad are oftentimes classified as “dependents” by the organization with which the family is living abroad. Since they have both a dependency as well as a foreigner status within their host countries “[spouses], children and the family collectively have representational roles” (Useem 1966). Although system identity among TCKs may not be as prevalent nowadays as it once was, especially in the cases of military and missionary TCKs, a strong link between system and personal identity tends to persist. System identity is even said to be “one of their primary identities” (Pollock et al. 2017).

Although these four factors distinguish TCKs from other subgroups of CCKs, at the end of the day, all of us with international or cross-cultural backgrounds belong to one big group: we are all cross-cultural kids. Understanding this and having a name for our lived experiences has helped me immensely in navigating my own feelings of identity and belonging. It explains why I relate to TCK research and tend to feel understood by TCKs and other CCKs. Despite our differences, it’s the similarities that unite us.

References

Bonebright, D. A. (2010). Adult third culture kids: HRD challenges and opportunities. Human Resource Development International, 13(3), 351-359.

Cottrell, A. B. (2007). TCKs and Other Cross-Cultural Kids. Kazoku Syakaigaku Kenkyu, 18(2), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.4234/jjoffamilysociology.18.2_54

Pollock, D. C., Van Reken, R. E., & Pollock M. V. (2017). Third Culture Kids. Growing Up Among Worlds. 3rd Ed. Nicholas Brealey Publishing. Boston.

Useem, J., Useem, R., & Donoghue, J. (1963). “Men in the Middle of the Third Culture: The Roles of American and Non-Western People in Cross-Cultural Administration.” Human Organization, 22(3), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.17730/ humo.22.3.5470n44338kk6733

Useem, R. (1966). “The American Family in India.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 368, 132-145. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/1036927

Van Reken, R., & Bethel, P. M. (2005). Third-culture kids: Prototypes for understanding other cross-cultural kids.

Zoe Krueger Weisel is a German-American-Italian researcher based in Italy. She was born and raised in Germany, but has lived in both the US and Italy since starting university. She has always had a particular research interest in the Third Culture experience due to her own military Third Culture background.

March 2023 34

35 Among Worlds | Visual credit: Miriam Celebiler

Everywhere and Nowhere All at Once

By Mayako Kruger

Where are you from?” The question that haunts every third culture kid inevitably squeezes itself into every conversation during my first week of university. Every time it’s asked, I’m afraid of being thought of as pretentious, but my response has never changed.

“I’m half Japanese and half Canadian but I grew up in the Philippines,” I always say reluctantly.

It’s not that I want to make my life sound more interesting or seem exotic; simply put, I struggle to pinpoint my identity to a single place.

When I was in my early teens, I wanted nothing more than to live the quintessential American life as seen in a Netflix show. To ride a yellow bus to school with the people I’ve gone to school with since kindergarten. To go home to my childhood bedroom during university breaks and get lunch with all my friends who were doing the same. To feel a sense of belonging to a small town where everyone knows everyone. While in many ways my life did fit that of the

typical Netflix Original—I played sports after school, hung out with my friends on weekends, and sat at the dinner table with my family every night as they asked the classic “What did you learn at school today?”—in many other ways it didn’t. The norm at my school was to move away after a few years; there were only twelve kids who were part of the “13 Year Club” yearbook spread, a page dedicated to those who attended my school from kindergarten to high school graduation. While they did count me among the “13 Year Club,” I had moved away to live in Tokyo for three years in the middle of elementary school. In Tokyo I did ride a school bus, but it was covered with abstract designs because a yellow school bus was too much of a “safety concern” that might be a clear target for potential antiAmerican attacks. Lastly, most of my graduating class, including myself, have no ties to Manila and won’t have any reason to visit in a few years when our families inevitably move away.

Yet I still feel a deep sense of belonging to a city where, superficially, I don’t belong. Is it fair for me to call Manila home when I’ve grown up in

March 2023 36

a bubble of privilege among foreigners living in the exact same situation as me?

Every Saturday morning, I would wake up at 7:00 a.m. to walk down the street with my yaya (nanny), Mercy, to visit the taho man. As soon as we stepped outside of our apartment compound, the palm trees and neat avenues were replaced with unkempt bushes and roads that desperately needed to be repaved. The taho man’s cart was parked by the side of the Pasig River as he called out “Taho! Taho!” His voice was the star of the symphony of rush hour jeepney and tricycle traffic.

I would exchange my 5-peso coin (10 cents CAD) for a small cup of warm taho: sheets of warm silken tofu with sago pearls and brown sugar syrup. “Salamat!” I would thank the man before Mercy took me home.

suggested pulling up to a house on the side of the road and asking to use their washroom. As I was six years old, holding it in was not an option, so that’s exactly what we did. The driver explained our situation to a middle-aged man and he generously let me and my mom into his house with dirt floors, a corrugated sheet of metal as a roof, and cement blocks as walls. His washroom consisted of a toilet bowl with a bucket of water and a tabo—a plastic water dipper used to flush the toilet as there was no plumbing. After thanking the man, my mom and I walked back to the car and drove the rest of the way back to our hotel.

These snippets are examples of my limited experience of what it’s really like for many people who live in the Philippines.

Within the bubble of expat kids, International Day was known to be one of the most exciting days of the year. We could forgo our uniform at my school in Manila and instead wear our home country’s national costume. Kids would come to school in their hanbok, baro’t saya, sari, or cowboy boots, and a cultural carnival emerged in our school playground. I would alternate between a red Roots Canada shirt and a Japanese yukata each year as an homage to my parent’s cultures and my passport countries. But still, whenever I visited Japan or Canada to see family, it always felt like more of a vacation than a homecoming.

Once on a family vacation to Bohol, an island popular for its Chocolate Hills (unusual geological formations) and tarsiers (a type of small primate), my family was driving back to our hotel in the hotel car service when I really needed to use the bathroom. The driver

Despite being able to speak Japanese and navigate Tokyo’s complex subway system, after passing the foreigners in the Japanesepassport-only line at immigration, I feel like a tourist myself. Shop owners and mall assistants are always surprised when I respond to their broken English with “Nihongo de daijoubu desu” (“Japanese is okay”).

Growing up with people from all over the world, I find myself to be adaptable in terms of respecting and following the social norms in a new situation, but there are some things

37 Among Worlds

“

I display different personas in different relationships.”

that are impossible to know without complete immersion. When I was about eleven, I was having a conversation with my grandmother about rice crackers, when I referred to her as anata, a pronoun I didn’t know at the time is only polite when you use it for people whom you don’t know—it is extremely rude if you use it for someone you do know. That was the first time I had heard my grandmother yell. I waited in tears for my mom to return from the grocery store, and when she did, I explained, “I don’t know why baba was so mad! I thought I was being polite.” Misunderstandings of the culture are what isolate me from “being Japanese.”

people whose lives seem more similar to my own at first glance.

Moving away from Manila only made my appreciation for the city grow. I’m thankful for the people, experiences, and the city itself for making me who I am today.

*This article and the accompanying visual were first published in The Ubyssey and are used with permission.

I display different personas in different relationships, shapeshifting in what seems like a fruitless attempt of stitching together pieces of my identity. I’m constantly trying to fit in with my surroundings, trying to find a place to make me feel, even temporarily, at home. The one place I didn’t have to try to fit in was in the international communities of expats I grew up in because our differences were, paradoxically, unifying. I felt at home not when the people around me ethnically resembled me but when we shared experiences. In many cases it was easier to find similarities with people from countries I had never imagined visiting than with

Mayako Kruger is a second-year student studying cognitive systems at the University of British Columbia. She is half Japanese and half Canadian but grew up in the Philippines, which she considers her home. Instagram: @mayakokruger

March 2023 38

One Move Too Many

By Christina Hoag

In 1976, we left Australia for America. It was my seventh international move, my father’s eighth, my mother’s ninth. It was the move that fractured my family forever.

Dad was to be president of the US subsidiary of the Swedish industrial multinational he worked for. He’d held an equivalent position with the company in Australia, but the United States was a much larger market. For him, it was a big promotion. For us, my mother and we three kids, it was yet another uprooting. It came just five years after his assurance that Sydney was the place we would finally call home.

The cracks in our family appeared soon after our arrival in New Jersey. That year my sister, brother, and I attended a total of three schools, plus a summer day camp where at thirteen, I was the oldest kid in the entire place.

Stress for my mother, particularly about driving on the other side of the road and on highways she’d never seen so jampacked, caused her to break out in shingles. And she was alone. My father absented himself on business trip after business trip. I recall

going on two strained family outings that summer: to see Franklin Roosevelt’s home at Hyde Park, which meant little to us as kids but which Dad wanted to see, and a Circle Line boat tour of Manhattan. For our first Thanksgiving we had spaghetti and tried to stay warm as a Northern Hemisphere winter approached.

None of us were prepared for American life. While Dad delighted in the custom of holding business meetings over breakfast, he wasn’t prepared for the rapacious competitiveness of the US market. The work culture was different, too. It lacked the bonhomie of Australia’s relaxed, egalitarian culture. In Sydney, we often socialized as a family with my father’s colleagues, going to beach picnics and barbecues. My parents went out a lot to fancy dinners and operas and cocktail parties. Mum had a wardrobe of evening gowns and accessories.

They also entertained a lot at home, which was exciting for us kids. We’d watch from the top of the stairs as dinner guests arrived at the front door. For parties, we’d be enlisted to refill peanut bowls. Every year, my parents hosted a bash for the managers and their spouses, and two Christmas drinks get-

39 Among Worlds

togethers, one for neighbors and non-work friends and another for company people. A particularly memorable affair was a blowout for my dad’s fortieth birthday. I woke up to loud music and crept downstairs to see a conga line shimmying around the living room at two in the morning.

Dad tried to replicate that cohesive atmosphere in New Jersey, but it didn’t work. A managers’ evening flopped when the guests were stiff and uptight in front of the boss. The same with smaller dinner parties. The events were never repeated. The company didn’t even hold a Christmas event that included families. Mum’s evening gowns gathered dust in the closet.

My father was a daily drinker throughout his life, but it worsened in America. The doorbell rang one night. I opened the door to see Dad flanked by two men holding him upright. “Get your mother,” he managed to spit out as he lurched forward. I ran off. Nothing more was said about that. Another morning, I left for school and noticed the mailbox had mysteriously taken on a sharp lean overnight. “Somebody must’ve clipped it as they drove along the road,” my father said later. Sure, Dad.

We were all affected. My brother was bullied at school and started to overeat. His weight ballooned. My sister and I had to fit into American teenage culture where kids grew up ultra- fast—cigarettes, pot, rock music, and boyfriends were badges of acceptance. My sister ran with a rough crowd, while I papered my room with posters of the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, puffed on Marlboro Lights, and counted the days until I could leave for university.

My parents had no idea what to do with American teenagers except cling to the archaic British tradition of packing kids off to boarding school. A year after our arrival, they sent away for a brochure for a girls’ school in Central New Jersey for me, but I refused to go, galled at the thought of yet another move. We’d just arrived in a new country. My family was all I had. Now I was supposed to be entirely on my own?

As time went on, we evolved into a bunch of people siloed in the same house. Some of that disconnection was undoubtedly due to the normal adolescent desire for individuality, but as a therapist pointed out to

me years later, much of it was because we were each focused on trying to survive in our new environment. My siblings and I rarely spoke. Dad was constantly away. When he was home, he holed up in the living room, drinking wine, cutting his toenails, and reading financial news to loud classical music that discouraged conversation. He refused to attend my brother’s soccer games with the excuse that his father hadn’t attended his rugby matches. My mother kept the household going in the background.

Then, three and a half years after we arrived, our lives turned overnight into a never-ending soap opera. My mother discovered photos in Dad’s briefcase one night. I happened to come upon her as she held the pictures in her hand, shock registering on her face. I tried to think of excuses for why Dad would have photos of a young blond woman with a small child on her lap in his briefcase. He’d probably brought the photos back from Stockholm for a colleague, I said. Mum knew the truth, of course, which was why she was rifling through his briefcase in the first place. He was having an affair. The child in the photos wasn’t his, Dad said. That, at least, proved to be true. He

March 2023 40

In Lagos, Nigeria, Christina Hoag is held by her nanny Clara. Her sister is being carried on Clara’s back in the traditional way of transporting babies.

was forty-five. She was twenty-eight. I was sixteen. It was such a cliché, it was embarrassing. What came next, I thought, the stereotypical Porsche roadster? It was worse. Over the next three years, my parents divorced. My father got fired. He had two children by different women in the same year. He made disastrous investments. He took to buying flagons of cheap red wine and was smashed whenever I saw him. And we got stuck in a country where no one but he had wanted to come. My mother considered taking us to England, but at the time no one had the stomach for another international move. We morphed from expats into immigrants.

I became ashamed of my broken family. None of my friends had divorced parents. It was another mark of difference on top of my accent, my international upbringing. Another hurdle I had to work to overcome. The cracks in my family deepened into fissures of unresolved grief and anger and resentment that only worsened with time. We lived scattershot all over the United States. My brother estranged himself from the rest of the family. My sister and I had perfunctory relationships with our father. She had a little more with our mother. I had a closer relationship.

Around the year 2000, Dad decided to spend half the year in New Zealand. I asked him for his address. “Just contact me through the office,” he said. My mother uttered an eerily similar statement around the same time: “It would be too close if we lived in the same city.” After decades of living away from their own families, they just didn’t know how to have a family with grown children.

Shortly before Dad died from an alcoholism-related cancer in 2009, we all gathered around his hospital bed, his first and second families. I hadn’t seen my half-brother in thirty years and had never met my nephew, my brother’s son. At that point, I didn’t even know I had another half-sister. That came later, thanks to genealogical DNA testing. Amid the hustle-bustle, I managed a few minutes alone with my father. I wanted him to utter some words of contriteness, to acknowledge that the last move was one move too many.

He never did.

Christina Hoag was slated to enter the world in Zambia but made her grand debut in New Zealand. Three weeks later, she moved to Fiji, the first of seven countries she grew up in. A former journalist and foreign correspondent, she reported from Latin America for Time, Business Week and The New York Times, among other media. She is the author of novels Law of the Jungle, The Blood Room, Girl on the Brink, and Skin of Tattoos. Her short stories and essays have appeared in literary reviews including Other Side of Hope, Lunch Ticket, Toasted Cheese and Shooter, and have won several awards.

More information: https://christinahoag.com

41 Among Worlds

Cross-Cultural Intersectionality

By Tanya Crossman

There are lots of ways to have a crosscultural childhood—to grow up deeply impacted by more than one cultural construct: more than one worldview, more than one way of doing life, more than one set of values by which to make decisions and judge the actions of others. Yes, the different food and language and other external things are great, and often we have deep emotional attachments to them, but the subconscious ways of thinking we learn alongside them are what really change our lives.

Something I recognised quite early on in my work with third culture kids, before I was even aware of Ruth Van Reken’s CCK model and cross-cultural umbrella analogy, was that some TCKs have additional layers of cross-cultural experience and identity, more so than others. As with any element of culture, it was something that seemed obvious on the surface, but as I explored, I began to realise just how deep the impact of those overlaps went.

43 Among Worlds

Some TCKs have additional layers of cross-cultural experience and identity

In the meantime, I began reading and learning more about race, privilege, discrimination against minorities, and disability—and came across the concept of intersectionality. Very quickly I knew this was the concept I had been looking for to describe what I was seeing in the TCK community. Intersectionality is generally used to describe the impact of belonging to overlapping categories of discrimination or disadvantage. For example, being of both a disadvantaged socioeconomic group and a race that is discriminated against means standing in the intersection of those two disadvantages, and therefore experiencing a greater impact than either of those groups would alone.

I began to use the phrase cross-cultural intersectionality to describe the impact of standing in the overlap of multiple cross-cultural childhood experiences. I know plenty of people who belong to four or five of the categories in Ruth’s CCK model! In my book, Misunderstood: The Impact of Growing Up Overseas in the 21st Century, I highlighted several simple overlaps. I interviewed individuals who lived in these intersections, and with their permission, shared some of their stories.