Perspective Shift

Orchestras navigate a time of rapid transformation and opportunity

Mexican Composers on the Rise

Youth Orchestras Make Their Mark

Dolly Parton Goes Orchestral

Orchestras navigate a time of rapid transformation and opportunity

Mexican Composers on the Rise

Youth Orchestras Make Their Mark

Dolly Parton Goes Orchestral

No matter what your perspective, the pace and volume of policy changes coming out of the federal government since the start of the year have been unprecedented. Shifts in procedures to obtain visas for visiting artists, potential cutbacks at the National Endowment for the Arts, increased scrutiny of initiatives concerning equity, diversity, and inclusion, and more make headlines every day—and directly impact orchestras. As this issue of Symphony went to press, new policies and revised directives continued to arrive hard and fast. Reporting on and analyzing the sheer volume of policy news—and the implications for orchestras—is more than any print publication can keep up with. For that reason, check out (timpani drumroll) symphony.org for ongoing coverage of the latest developments. And be sure to follow the alerts and emails from the League’s advocacy team in D.C.

In this issue of Symphony, we report on the rise in commissions and performances of music by Mexican composers at American orchestras. We catch up with composers—with widely divergent aesthetic profiles—who are making their marks with premieres at orchestras. We explore emerging trends in concert formats, report on the renaming of a concert hall for iconic diva Marian Anderson, and examine the impact and lifelong resonance of the country’s myriad youth orchestras. And we meet a country music divinity: Dolly Parton, who is lately drawn to orchestras. She explains, “I was very humbled by the fact that the symphony wanted to play my songs.” Dolly, no one could say it better.

VOLUME 76, NUMBER 1 / SUMMER 2025

symphony® the award-winning magazine of the League of American Orchestras, reports on the issues critical to the orchestra community and communicates to the American public the value and importance of orchestras and the music they perform.

EDITOR IN CHIEF

PRODUCTION & DESIGN

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

ADVERTISING ASSOCIATE

PUBLISHER

PRINTED BY

Robert Sandla

Jon Cannon, Big Red M

Stephen Alter

Lexi Sloan-Harper

Simon Woods

Dartmouth Printing Co. Hanover, NH

The print edition of symphony® (ISSN 0271-2687) is published annually by the League of American Orchestras, 520 8th Avenue, New York, NY 10018-4167.

SUBSCRIPTIONS AND PURCHASES

Annual subscription: $15 domestic/$20 international. To subscribe, visit americanorchestras. org/symphony-magazine/subscribe-to-symphony/, call 646-822-4080, or email member@ americanorchestras.org. Current issue $15.00. Back issues available to members $6.95/nonmembers $8.45. League Member Directory, 75th Anniversary, and other special issues: members $11.00/non-members $13.00. Call 646-822-4080 or email member@americanorchestras.org

ADDRESS CHANGES

Please send your name and your new and old addresses to Member Services at the New York office (address below) or send an e-mail to member@americanorchestras.org

EDITORIAL AND ADVERTISING OFFICES

League of American Orchestras 520 8th Avenue, New York, NY 10018-4167

E-mail (editorial): editor@americanorchestras.org

E-mail (advertising): salter@americanorchestras.org

Phone (advertising): (646) 822-4051

© 2025 LEAGUE OF AMERICAN ORCHESTRAS

symphony® is a registered trademark. Printed in the U.S.A.

WEBSITE americanorchestras.org

The Utah Symphony performs in the great outdoors. Photo courtesy of the Utah Symphony | Utah Opera.

2 Prelude by Robert Sandla

6 The Score Orchestra news, moves, and events

12 Conductor, Advocate, Change Agent

Throughout this issue, text marked like this indicates a link to websites and online resources. 62 32 40 24 12 6

Marin Alsop keeps shattering glass ceilings: as an adventurous artist, music director of U.S. and international orchestras, champion of music education for all, and advocate for women conductors. By Simon Woods

16 What’s Up in Utah: The View from the Board

As orchestras across the U.S. face a shifting landscape, board leaders are thinking carefully about how to proceed with purpose. With the League’s National Conference happening in Salt Lake City this year, leaders from orchestras across Utah share their priorities, challenges, and hopes. By Piper Starnes

20 Musician to Financier to Board Chair

Alan Mason, the chair of the League of American Orchestras’ Board of Directors, may just be uniquely suited to lead the national service organization. By Robert Sandla

24 Immersion Versions

“Immersive” concerts of multiple kinds are drawing new and veteran audiences to orchestras, as are performances that seat listeners among musicians. Orchestras are prioritizing artistic fidelity while forging closer connections. By Jeremy Reynolds

32 Revolución : Mexican Composers on the Rise // Revolución: Compositores Mexicanos en Ascenso

More and more orchestras are performing—and commissioning and recording—works by Mexican composers. Here’s a look at just a few of the composers making their mark. // Cada vez más orquestas interpretan, encargan, y graban obras de compositores mexicanos. A continuación, un vistazo de algunos de los compositores que se destacan. By // Por Esteban Meneses

40 Youthful Sounds, Enduring Impact

Youth orchestras support young people across the country with inspiring musical training, creative development, diverse programming, cultural insights, and the joy of music. By Lindsey Nova

48 A Voice. A Name. A Concert Hall.

Marian Anderson was a contralto with a once-in-a-lifetime voice—and she was a formidable defender of civil rights. Now the Philadelphia Orchestra has honored her legacy by naming its home for her. By David Patrick Stearns

54 Influences and Inspirations

Four composers of upcoming and recent works talk about personal expression, forging fresh sonic realms, and writing big new scores for the “irreplaceable heft of the orchestra.” By Heidi Waleson

59 Advertiser Index

60 League of American Orchestras Annual Fund

62 From Rags to Wishes

Dolly Parton has done it all: music, movies, television, Broadway, philanthropy, even her own theme park. Now the country music icon has embarked on what may be the only uncharted territory left: American orchestras. By Ann Lewinson

In the midst of monumental shifts in the national policy environment, orchestras are engaging their stakeholders in strategic conversations about actions to help them uphold their values, advance their missions, and participate in policy advocacy. The League is taking action in partnership with the wider arts and nonprofit sectors and providing new forms of support and leadership for orchestras. The League has created Resources for Navigating the Changing Landscape at americanorchestras.org/ navigatingthechanginglandscape with messaging guides, legal insights, and policy updates that help each orchestra make decisions that are responsive to its unique circumstances.

The League is providing direct support to member orchestras, answering urgent questions regarding the international artist visa process, federal grant terminations, and other government compliance concerns. In an unprecedented reversal of approved federal support for the arts, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) sent notifications terminating hundreds of awards in progress and withdrawing many offers of FY25 grant awards that had been accepted by applicants, with a second wave of notices delivered a week later. The NEA’s capacity to support the arts sector will also be diminished as eligible personnel at the NEA were encouraged to take early retirement or deferred resignation to meet the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) staffing reduction targets. As a result, all program directors and many staff have left or will be leaving the NEA over the coming weeks and months. The League is posting updated news about NEA grantmaking procedures at americanorchestras.org/neagrantprocess, and partnering as orchestras speak up to Congress at americanorchestras.org/ contactcongressnea to protect future federal funding.

A full-house crowd converged on Davies Symphony Hall on April 26 as the San Francisco Symphony celebrated the 80th birthday of Michael Tilson Thomas, its music director from 1995 to 2020. The evening also brought Thomas’s goodbye to performing, a decision he announced in February after the resurgence of brain cancer first diagnosed in 2021. When he walked out to open the evening with Benjamin Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra , Gabe Meline wrote on KQED. com, “the love in the room was about the strongest I’ve ever seen.” Edwin Outwater and Teddy Abrams, two of many conductors Thomas mentored, shared conducting duties as the honoree watched from a chair flanking the podium. Thomas’ favorite color, blue, gleamed from the musicians’ scarves and neckties, as well as from balloons that cascaded from the

The League is a leader in bipartisan, national coalition efforts to support the nonprofit sector under comprehensive tax reform and to advance arts policies in Congress. The U.S. House of Representatives has passed a massive budget and tax reconciliation bill, and the Senate is now crafting its own version. The League’s Tax Policy and Charitable Giving Campaign at americanorchestras.org/contactcongresstaxpolicy has an overview of what was included in the House bill and resources to help orchestras speak up. Significant changes to the tax package are expected as the Senate takes steps over the summer.

In support of all of this action, the League is building the advocacy capacity of orchestras to make their case at the local, state, and federal levels through our online resources and national learning events. The League’s Playing Your Part Guide to Orchestra Advocacy at americanorchestras.org/playingyourpart has been expanded to include an online learning webinar and a session at the League’s National Conference this June.

NOTE: Fundamental new directions, changes, and reversals on federal policies and programs are being made at extraordinary speed, and the information on this page is accurate as of Symphony ’s press time. The League sites listed above are updated on an ongoing basis, so check them for the most recent resources and information, and symphony.org for breaking news.

ceiling and commemorative bandanas given to the audience. The bandanas held Thomas’s words: “There are two key times in an artist’s life. The first is inventing yourself. The second, the harder part, is going the distance.”

The Phoenix Symphony teamed up with the Phoenix Holocaust Association on April 27 for the latter’s annual Holocaust Remembrance Day. The event, held at Symphony Hall, commemorated the 80th anniversary of the liberation of concentration camps at the end of World War II. The orchestra and former music director Tito Muñoz launched the musical component with Symphonic Metamorphosis on Themes of Weber by Paul Hindemith, one of the artists condemned by the Nazi regime as “degenerate.” The Symphony Chorus and four vocalists then joined in for Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, with its “Ode to Joy” envisioning worldwide brotherhood. The event continued with a procession of Holocaust survivors, a candlelight ceremony honoring the 6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust, remarks by a survivor, and other observances. The orchestra plans to continue the collaboration next year. Among Holocaust events at other orchestras, a November concert by the Norwalk Symphony Orchestra featured Violins of Hope, a collection of restored string instruments that belonged to Holocaust victims. And the New World Symphony mounted a series of concerts and events called “Resonance of Remembrance: World War II and the Holocaust.”

The Hartford Symphony Orchestra branched out into contemporary opera by showcasing Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones this spring. Based on a memoir by journalist Charles M. Blow, Fire Shut Up in My Bones tells the story of a Black man coming to terms with his painful past. Composer and jazz trumpeter Blanchard blends jazz, gospel, and classical elements in the work, which in 2022 became the first opera by a Black composer to be performed at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. HSO Music Director Carolyn Kuan led arias and other excerpts with soloists including Blanchard, soprano Janinah Burnett, baritone Will Liverman, and Blanchard’s jazz ensemble, The E-Collective. The program also featured selections from Blanchard’s scores for films including Malcolm X, Harriet, and BlacKkKlansman. Blanchard drew on his Fire Shut Up in My Bones score to create an orchestral suite that the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered last September.

Among the many policy developments underway, significant action is advancing regarding the rules for international travel and trade with musical instruments that contain natural materials protected under international rules. The League partners with global music stakeholders to weigh in on policies regarding the Convention in International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and provides direct assistance to orchestras navigating permit requirements for musical instruments.

In November 2025, the 185 global parties to the CITES treaty will meet to consider new policy proposals for worldwide implementation. While the full agenda for those negotiations will not be set until later this summer, the League and its partners in the U.S. and globally are going on record about action to support improvements to the CITES Musical Instruments Certificate, sustainability measures for the Pernambuco wood used in crafting many bows for stringed instruments, and other policy measures that can advance urgent conservation concerns while supporting international cultural activity with musical instruments. Musicians can take action by documenting the material in their bows, using the resources in the League’s Know Your Bow Guide for Owners at https://americanorchestras.org/ know-your-bow-tips-forowners-and-users-of-pernambuco-bows/

The Richmond Symphony joined forces with Virginia Opera to mount the world premiere of Loving v. Virginia , which tells the human story that led to the 1967 Supreme Court decision striking down bans on interracial marriage. Created by composer Damien Geter and librettist Jessica Murphy Moo, the work was commissioned by Virginia Opera. “As a native Virginian, the historical significance of Loving v. Virginia has remained with me since I was a teenager,” said Geter, who is composer in residence at the Richmond Symphony. Bringing plaintiffs Mildred and Richard Loving and their quest to the stage, he continued, “is important not only for the sake of honoring their legacy, but also for ensuring the future of the art form.” Loving v. Virginia premiered in Norfolk on April 25, with further performances in Fairfax and Richmond. Washington Classical Review critic Charles T. Downey called the work “one of the most successful new operas of the decade,” adding that “Geter’s score alternated between neo-romantic lush harmony and scoring and the pulsating rhythms of minimalism.”

After studying the violin with Spokane Symphony Orchestra Concertmaster Mateusz Wolski from age 10, Jessie Morozov shared the stage with him in March—as a new member, at age 16, of the orchestra’s second-violin section. Spokane Symphony Music Director James Lowe told Monica Carrillo-Casas of the Spokesman-Review that he first encountered Morozov when she played in the Spokane Youth Symphony, where she was concertmaster. “There are people for whom an instrument is a thing that they have taken on and learnt,” Lowe said, “and then there are people for whom it is absolutely part of their body ... And that’s how I felt when I first saw Jessie play.” The Ferris High School junior won her spot in the adult orchestra only after a formal blind-audition process that also included adult musicians. Said Morozov, “Knowing that I will be a part of this magic is such a blessing.”

Fifteen million is a lucky number for the Jacksonville Symphony and Utah Symphony | Utah Opera. An anonymous donor in March pledged $15 million to the Jacksonville Symphony—the largest donation in the orchestra’s history. “This generous gift stands as a testament to the love and support that drives us forward, affirming that our work and presence matter to those we serve,” Steven Libman, the orchestra’s president and CEO, told the Jacksonville Business Journal. The donation, earmarked for the orchestra’s endowment, will help the orchestra attract musicians, commission new works, and offer educational programs. The Jacksonville philanthropy continued in April, when the Terry Family Foundation pledged $3 million to fund the orchestra’s programming as well as improvements in Jacoby Symphony Hall. Meanwhile, Utah Symphony | Utah Opera welcomed a pledge of $15 million from the O.C. Tanner family. That donation, spread over 10 years, will support key leadership positions and “address critical undercapitalization.” The post of president and CEO, currently held by Steven Brosvik, will be dubbed the O.C. Tanner Chair.

Conductor Oksana Lyniv and the Kyiv Symphony Orchestra marked the third anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with a March 24 performance of Evgeni Orkin’s Five Interrupted Lullabies. Lyniv commissioned the work, a memorial to a group of Ukrainian children lost to a Russian rocket attack on Odessa in March, 2024. Orkin’s website says he was born in Lviv, Ukraine, to a family of musicians, and studied at music colleges in Kyiv; Utrecht, Holland; and Mannheim, Germany. Now a resident of Germany, he’s a composer, conductor, and clarinetist, and his works have been performed by the Deutsche Oper Berlin Orchestra, Odense Symphony Orchestra, Princeton University Orchestra, violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja, and others. The Kyiv Symphony’s concert—which also included Orkin’s Requiem for a Poet and works by Beethoven and others—took place in Monheim am Rhein, Germany, where the orchestra has a residency. Lyniv premiered Five Interrupted Lullabies last September in Denmark with the Odense Symphony, and she’ll take the work to the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra next January.

colleagues.

The New York Philharmonic and Music and Artistic Director-Designate Gustavo Dudamel marked the 125th anniversary of Maurice Ravel’s birth with the world premiere in March of a work from the composer’s student years: Prélude et Danse de Sémiramis, from a cantata about a legendary queen of Babylon. The only known hearing during Ravel’s lifetime came in a non-public rehearsal by the Paris Conservatory’s student orchestra, said Gabryel Smith, the Philharmonic’s director of archives and exhibits. The score was long presumed lost, but sleuthing led scholars to an unsigned manuscript at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. “It’s a nice view of a composer that’s still discovering his own style,” Smith said. In a review, the New York Times’ Zachary Woolfe describes the five-minute score: “Grave and gloomy, bronzed by the low luster of a gong, the first section rises to the dramatic punch of an opera overture. The music then accelerates into a gaudy Orientalist dance that looks back to the Bacchanale from Saint-Saëns’s ‘Samson et Dalila’ and the ‘Polovtsian Dances’ of Borodin.”

After last winter’s devastating wildfires in the Los Angeles area, California orchestras and their musicians got busy helping the region recover.

In late January, the Pasadena Symphony’s first concert after the fires helped kick off an instrument drive to replace those lost by members of the Pasadena Symphony Youth Orchestra. Not only did some students lose their instruments when they had to flee their homes, but several schools in Altadena lost their entire instrument collections.

Members of the San Francisco Symphony and Chorus and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music joined forces in a March concert dubbed “SF Musicians for LA: A Benefit for Fire Relief.” The program, featuring pianist Garrick Ohlsson of the conservatory faculty as soloist, included music by Copland, Rachmaninoff, and Dvořák. Before capping off the concert with “Make Our Garden Grow” from Leonard Bernstein’s Candide, conductor Edwin Outwater addressed the audience. “If you know Voltaire’s novel or Bernstein’s opera, you know it’s about posing a question: How do we endure in a cruel world? … There’s no easy answer, but Leonard Bernstein and Voltaire’s answer is to build a garden and make the garden grow. Work together to build something back.” The orchestra announced on Facebook that the concert raised $118,500 for the Entertainment Community Fund and Habitat for Humanity of Greater Los Angeles.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic and guests including pop star Christina Aguilera performed a free concert at the Hollywood Bowl on April 1 to thank first responders. The orchestra also collected donations of supplies for survivors, and it donated 5 percent of ticket revenues from its February and March concerts at Walt Disney Hall to support the Los Angeles County Parks Association.

Simply getting back to work heartened the musicians of Orchestra Nova LA, Music Director Ivan Shulman writes on symphony.org. The orchestra’s first post-fire rehearsal began with Shostakovich’s Festive Overture. “When we finished, and the musicians started to look up from their parts, I saw smiles on their faces, smiles which had not been there before we started.”

The Wallace Foundation has published a report that examines how community-based youth arts programs can support diverse young people. In “Well-being and Well-becoming Through the Arts,” University of Pittsburgh researchers look at what they call culture-centered, community-based youth arts programs. “As fewer and fewer schools offer arts learning opportunities, out-of-school time organizations in many communities have stepped in to fill that space. This is particularly true in neighborhoods with low income and diverse populations, where robust arts programs are least likely to be present in schools,” the summary says. The report identifies key values and goals of programs that yield positive results, while interviews with staff and young people showed that “participants often experience joy, a sense of accomplishment, and a growth in confidence and significance through their engagement in the arts.” Read the report at wallacefoundation.org.

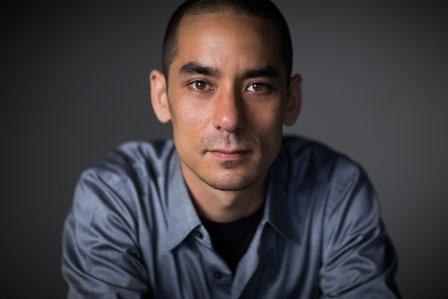

Ryan Fleur became president and CEO of the Philadelphia Orchestra and Ensemble Arts in April, after serving on an interim basis since January. A member of the orchestra’s staff since 2012, he played a pivotal role in the orchestra’s merger with the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, now known as Ensemble Arts Philly. Music and Artistic Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin saluted Fleur’s “dedication to the musicians, his forward-thinking approach, and his ability to unite diverse communities around the transformative power of music.” Before going to Philadelphia, Fleur was president and CEO of the Memphis Symphony Orchestra and held executive positions at Boston Ballet, the New York Philharmonic, and the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston. Fleur earned degrees in economics and business from Boston University, and took part in the League of American Orchestras’ Orchestra Management Fellowship Program, which included stints with the San Francisco Symphony, New Jersey Symphony, and Indianapolis Symphony. Ryan Fleur.

In January, Gary Ginstling was appointed executive director and chief executive officer of the Houston Symphony. He succeeded John Mangum, who departed to lead the Lyric Opera of Chicago. Ginstling has held several leadership roles at major American orchestras. Most recently, he spent two years at the New York Philharmonic, serving in the roles of executive director and, until July 2024, as president and CEO. Previously, Ginstling was executive director of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, DC, from 2017 to 2022, and CEO of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra from 2013 to 2017. Prior orchestra leadership positions include general manager of the Cleveland Orchestra; director of communications and external affairs of the San Francisco Symphony; and executive director of the Berkeley Symphony. Under Ginstling’s leadership at the New York Philharmonic, the organization secured a $40 million contribution to its endowment. Ginstling holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Yale University, a Master of Music degree from the Juilliard School, and a Master of Business Administration from the Anderson School at UCLA. Ginstling serves on the board of the League of American Orchestras.

Jonathon Heyward has a contract extension and an expanded title at the Festival Orchestra of Lincoln Center: his tenure as music director and artistic director of the Festival Orchestra of Lincoln Center runs through the 2029 season. Building on his 2024 inaugural season as music director, which included commissions from composers Huang Ruo and Hannah Kendall, in 2025 Heyward will lead commissions by three composers whose works will premiere across the next two summers as part of Lincoln Center’s Summer for the City festival. The culminating performance of the orchestra’s 2025 season includes the premiere of a commission by James Lee III, composer in residence with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, where Heyward is also music director.

Sidney P. Jackson, Jr. has been appointed president and chief executive officer of Chicago Sinfonietta. He will succeed Wendy Lewis, who served as interim CEO since December 2024. Jackson will become president and CEO on June 13, 2025, after he concludes projects at the New Jersey Symphony, where he is vice president of development. At the New Jersey Symphony, Jackson led a multi-million-dollar fundraising initiative that expanded donor engagement and long-term support; he also created and launched the orchestra’s centennial campaign. Committed to inspiring communities through the transformative power of music, Jackson has worked in the non-profit arts sector and others, including human services, children and family, anti-poverty, and justice initiatives to benefit diverse communities. Born in Charleston, West Virginia, he grew up in Jacksonville, Florida. Prior to the New Jersey Symphony, Jackson worked in New York City for nonprofit organizations including Helpusadopt.org, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and Harlem School for the Arts.

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra named Robert McGrath as president and CEO in February. McGrath succeeded Jonathan Martin, who retired at the end of 2024. McGrath is a 27-year veteran of the orchestra field, including nine years as vice president and general manager and four years as chief operating officer at the CSO. He will lead the CSO and also serve as president of the CSO’s subsidiary, Music and Event Management, Inc., and as president of CSO’s partner organization, the Cincinnati May Festival. McGrath is leading CSO management in the implementation of a strategic plan that establishes concert innovation, learning, and diversity, equity, and inclusion as core areas. Under McGrath’s leadership, the Nouveau program, designed to nurture student musicians from backgrounds underrepresented in orchestral music, has expanded. McGrath is a graduate of the New England Conservatory with a Bachelor of Music in bassoon performance, and is an alumnus of the League of American Orchestras’ Orchestra Management Fellowship Program. Previously, he held senior positions with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Louisville Orchestra, and Chicago’s Music of the Baroque.

The Annapolis Symphony Orchestra in Maryland has appointed ERICA BONDAREV RAPACH as executive director. She joined the ASO as interim executive director in 2024.

Boston’s Longwood Symphony Orchestra has appointed HANNAH COLLINS as executive director.

The Wallace Foundation, which supports education and the arts, has appointed JEAN S. DESRAVINES as president.

The Lancaster Festival in Ohio has chosen JOHN DEVLIN as music director. Devlin is also music director of the Wheeling Symphony Orchestra in West Virginia.

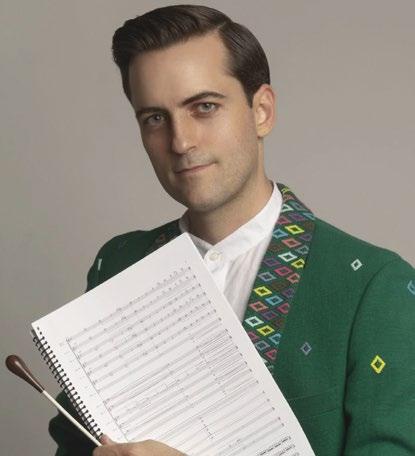

MICHELLE DI RUSSO has been appointed music director of the Delaware Symphony Orchestra. She is in her second season as associate conductor of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. Philadelphia’s No Name Pops Orchestra, which will be rebranded as the Philly Pops, has named CHRISTOPHER DRAGON as music director. Dragon also holds conductor positions with the Wyoming Symphony, Colorado Symphony, and Greensboro Symphony in North Carolina.

The San Francisco Symphony has appointed JOSHUA ELMORE as principal bassoon. He was previously principal bassoon at the Fort Worth Symphony.

The Cleveland Orchestra has appointed TAICHI FUKUMURA as assistant conductor, JAMES FEDDECK as principal conductor and musical advisor of the Cleveland Orchestra Youth Orchestra, and TYLER TAYLOR as the Daniel R. Lewis Composer Fellow.

The Lexington Philharmonic in Kentucky has selected BRITTANY J. GREEN as its 2025-26 composer in residence.

GABRIELA LARA joined the first-violin section of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in January, becoming the first Latina and third Hispanic member in the orchestra. She was a concertmaster in the Civic Orchestra of Chicago and a member of the Milwaukee Symphony.

EDUARDO LEANDRO has been appointed music director and principal conductor of the Greater Bridgeport Symphony in Connecticut.

The Oregon Symphony has named JESSICA LEE as associate concertmaster and HARRISON LINSEY as principal oboe, effective with the 2025–26 season.

Connecticut’s Ridgefield Symphony Orchestra appointed ERIC MAHL as music director. Mahl is also music director of the Northport Symphony Orchestra, Geneva Light Opera Company, and the Western Connecticut Youth Orchestra.

JOANN FALLETTA will become the Omaha Symphony’s principal guest conductor and artistic advisor with the 2025-26 season. Falletta is music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic, a post she will retain.

WENDY FANNING has been appointed executive director of the Fort Collins Symphony in Colorado. She succeeds Mary Kopco, who has retired.

MARC FELDMAN has joined the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra as chief executive. Feldman previously led the Orchestre National de Bretagne and California’s Sacramento Philharmonic Orchestra.

MARTIN MAJKUT, music director of the Rogue Valley Symphony in Ashland, Oregon, and the Queens Symphony Orchestra in New York, has been appointed music director of the Oregon Coast Music Festival.

The Plymouth Philharmonic Orchestra in Massachusetts appointed KARA E. MCEACHERN as executive director. She has worked at the Plymouth Philharmonic since 2017.

MONICA MEYER BEALE has been named senior vice president and chief development officer at the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

Colorado’s Longmont Symphony Orchestra named SARA PARKINSON as executive director. Parkinson was previously executive director and director of education and community engagement at the Boulder Philharmonic.

GRACIE POTTER has joined the Detroit Symphony Orchestra as principal trombone. Potter was previously acting principal trombone of the Richmond Symphony in Virginia.

Oregon’s Eugene Symphony has appointed ALEX PRIOR as music director; he will take the helm in the fall. Prior has served as assistant conductor of the Seattle Symphony and music director of the Edmonton Symphony.

JANET REIHLE has been named president and executive director of the Mississippi Symphony Orchestra.

HUANG RUO has been appointed composer in residence at the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra.

CALEB QUILLEN has joined the Boston Symphony Orchestra as principal bass. He replaces Edwin Barker, who retires after 48 years as principal bass. Third horn MICHAEL WINTER has been promoted to BSO associate principal horn as well as principal horn of the Boston Pops.

The Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra has appointed SULIMAN TEKALLI as concertmaster.

The Minnesota Orchestra has appointed JAMES VAUGHEN as principal trumpet. He succeeds Manny Laureano, who retired from the principal trumpet post after 44 years in the orchestra.

California’s Santa Rosa Symphony has appointed JACO WONG as conductor for the Santa Rosa Symphony Youth Orchestra. Virginia’s Richmond Symphony has named TREVOR WORDEN as director of leadership and planned giving.

JEAN-MARIE ZEITOUNI will join Canada’s Edmonton Symphony as music director at the start of next season.

Marin Alsop has shattered glass ceilings as an adventurous artist, a music director of U.S. and international orchestras, a passionate champion of music education for all, and a tireless advocate for women conductors. This summer, as she receives the Gold Baton award from the League of American Orchestras, Alsop assesses her career—and the state of the art.

By Simon Woods

Marin Alsop’s resume is almost impossible to summarize briefly. She was music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra from 2007 to 2021 and principal conductor of the São Paulo State Symphony in Brazil from 2012 to 2019. Currently she is chief conductor of the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; artistic director and chief conductor of the Polish National Radio Symphony; principal guest conductor of the Philharmonia Orchestra in London; principal guest conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra; chief conductor

of the Ravinia Festival in Chicago, and music director of the National Orchestral Institute and Festival at the University of Maryland. It’s a stellar, remarkable career.

It has also been a journey of advocating for classical music, of supporting young people, and—especially—of working tirelessly for women in our profession. It is for all of those reasons—her artistry, her advocacy, and her history as a change leader—that this year we are thrilled to give her the highest honor of the League and the orchestra profession, the Gold Baton.

Marin follows in the footsteps of many amazing conductors who have received the Gold Baton over the decades, including Leonard Bernstein, Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormondy, Pierre Boulez, Michael Tilson Thomas, Thomas Wilkins, and— appropriately, given that the League’s National Conference is in Salt Lake City this year—Maurice Abravanel, the longtime music director of the Utah Symphony.

SIMON WOODS: I want to start this discussion with Maurice Abravanel. Most people probably don’t realize that there’s a personal connection between you and Abravanel and the Utah Symphony.

MARIN ALSOP: There’s a deep personal connection, because my dad was from Murray, Utah. He played violin, flute, clarinet, and saxophone, and Maurice Abravanel gave him his first job, playing violin. But he also doubled on bass clarinet in the Utah Symphony. He told me, “Well, if it’s a big bass clarinet solo. I play bass clarinet that week, and if they need violins, I play violin.” It was Maurice who told him, “You’re too talented to stay here. You have to go to New York and pursue a career.” That prompted my Dad to study in New York, and he became concertmaster of the New York City Ballet Orchestra. He followed my mother, whom he had met at a summer music festival. I grew up in the orchestral world with my parents. My mother was a cellist, and they belonged for couple of seasons to the Tulsa Symphony, and then the Buffalo Philharmonic. They did get around a bit before settling in New York.

I think that U.S. orchestras are without a doubt the great orchestras of the world. It saddens me that there aren’t more Americans as music directors of the great American orchestras. But it’s always a joy for me to work with American orchestras. My relationship with the Philadelphia Orchestra goes back many years—they gave me one of my very first subscription concert engagements when I was 30, and they’ve always believed in me. It’s very nice to come full circle with that relationship.

WOODS: Is there anything specific that distinguishes American orchestras? You’ve worked a lot in Europe. You had a long relationship with the São Paulo orchestra. What is it that makes American orchestras American?

ALSOP: There’s an independence of spirit. There’s a very high level of technical proficiency. Go to an audition for one of these orchestras, and you’re blown away by the candidates—the level of auditionees is so high and so competitive. It’s technical and artistic excellence that really defines American orchestras. I wouldn’t limit that to the top orchestras; you can go to small cities and find very proficient, very competent, and very engaged orchestras. I think back to my first music director position, at the Eugene Symphony in Oregon. That was one of the most rewarding artistic experiences I had. They were wonderfully enthusiastic and supportive. Sometimes it’s the smaller community orchestras that exhibit this kind of passion.

WOODS: The League has 650 orchestra members, and you’ve got to go pretty far down that list before you stop finding orchestras that can turn in superb performances of major repertoire works. Do you find yourself adapting when working with orchestras in different continents in different styles, or do you show up as who you are, with your own personal way of working?

ALSOP: It’s a little bit of both. I am who I am, so I don’t try to affect any kind of change in that, but for me it’s important to at

least understand the trajectory of an orchestra, the work, pace, the run-up to a concert. Whether I go to Vienna, where I have substantial rehearsal time, or to London, where I have much less rehearsal time, I try to adapt. Instead of going into an orchestra and trying to impose something, I find it, at least for me, much more successful to try to identify where their strengths are and build on those.

WOODS: The role of the conductor is essentially the same, whichever continent you’re on. The role of the music director, however, is definitely not the same. Can you talk about the difference between being music director or principal conductor in, say, Vienna, to being music director of an orchestra like the Baltimore Symphony? American orchestras demand way more from their music directors beyond the stage.

ALSOP: It’s a completely different experience and far different level of responsibility and engagement. I hope that my positions in Europe and Brazil benefited from my experience in the United States, because as music director, I’m a very hands-on, deeply committed community person. That is not expected at all, I would say, in Europe or South America. It emanates, probably, from the fundamental funding differences. As music director, we really need to be the ambassador for the orchestra in terms of donors and sponsors and gifting, because we’re dependent on that, whereas in Vienna it’s a government-subsidized orchestra. Same in São Paulo, although this is now shifting a bit. I think I’ve been able to help all of the orchestras adapt a bit more toward the American model, although thankfully they won’t have to go full force in that direction.

WOODS: That seems like a good pivot to talk about the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. One of the most remarkable things in Baltimore is the OrchKids program, which you are very passionate about. In this country, we’re simply not able to rely on music education in schools, especially not for those in underprivileged communities. Could you talk about what led to OrchKids?

ALSOP: I’ve always been struck by the lack of diversity in American orchestras, probably in orchestras worldwide. Is it about access? Is it about talent? Is it about opportunity? Cultural reference? What is the reason behind that?

When I took over in Baltimore, which is a predominantly African American city, I was struck by the fact that there’s one Black musician in the orchestra. She’s a wonderful cellist. She’s been there for 40 years. So I proposed that we do

an experiment, which led to OrchKids. Starting a program like this requires a lot of funding, and the organization was rightfully nervous about having to fundraise in a huge way for another program. Luckily, I won the MacArthur Fellowship and came into some money that I didn’t expect. I thought, Okay, this is why I won it. And this is what I can use my money for. I was able to give the seed money to start the OrchKids program, and that immediately generated matching funds from several wealthy individuals and wonderful friends of mine in the community. I started with one small school in West Baltimore with 30 first-graders, and it became quickly clear to us that the music was not going to be the main obstacle in these environments—the kids didn’t have healthy food to eat. We immediately pivoted and got some organic meals served every day to the kids. And that continues. Schoolwork was a problem, so we started a mentoring program with some of the corporations in Baltimore. And that continues today. What became immediately clear was that for the kids, music was going to be a route to a whole-child approach to studying an art form.

Growing up, it wasn’t until I found the violin that I became absorbed and passionate about music. So I wanted every kid in the program to pick their own instrument and not to have it imposed on them. For six weeks they try each different family of instrument until they find one they like. We got some instruments donated, and we brought in some basses. I’ll never forget this young man, Tyrone—he just ran over to the bass like it was his long-lost brother or something. He knew immediately: this is my instrument.

I’m passionate that all musicians should know how to improvise, how to compose, and should have as broad a music education as possible. All the OrchKids compose and know how to improvise, and this is wonderful to see. I couldn’t have anticipated in 2008 when we started the program that some of those 30 kids that we started with would graduate from high school, go to university, and study music. The program, while of course it is about music, was a haven for the kids after school, a safe place. It was a place of community, where they were heard and applauded. It gave them opportunities to travel, to be seen. They need to be recognized for the unique individuals that they are.

I always thought every kid is born a genius, and somehow society just sucks it out of them. This is a manifestation of that, that these kids are all extraordinary young people, and they’re succeeding in music and other realms. They’ve taken the skills that they’ve learned in OrchKids—how to motivate themselves, how to budget your time, how to work under stress, how to listen to others. All of these things come into play in other disciplines. I think that they’re going to become the leaders of tomorrow.

I always know an OrchKid right away, because they call me Miss Marin. I fully expect to go to a doctor in five years, and she’ll say, ‘Hello, Miss Marin.’ I see kids as leaders.

WOODS: What are the components of OrchKids? Is it lessons as well as coming together in ensembles and an orchestra?

ALSOP: There are all kinds of ensembles, ranging from jazz band to orchestral and bucket band for percussion. There’s choir and all kinds of opportunities. We try to give them as broad an introduction and education as possible. We keep them really busy. Last time I was chatting with Nick Skinner, who’s the wonderful executive director of OrchKids, they play upwards of 50 concerts a year, in the community and around, and they travel far and wide. Several of the kids have been to Europe.

It’s the gift of imagination. Without imagination, what do you have? It’s a pretty dull outlook if we don’t invest in our children’s imaginations.

WOODS: The other area where you’ve had such an extraordinary impact is all your advocacy for the roles that women play, particularly as conductors. On the one hand, we have a very long way to go. On the other hand, it is tremendously inspiring to see this current generation of young women conductors who are coming to fruition. It’s a whole different level in the public eye than we would have had even a decade ago, and honestly, I cannot imagine that it would have happened without you and all the work you put into your Taki Alsop Conducting Fellowship program.

ALSOP: I’m thrilled to see the incredible talent that’s coming up through the ranks as guest conductors, as music directors, as chief conductors, assistant conductors. Conducting is unlike being an instrumentalist, because you can’t practice your instrument unless you’re given an opportunity. With so few opportunities in

the past, it was very difficult for women to achieve their highest personal level. But what’s happening is that women are being given and taking opportunities. That is reflected in their skill set, because the more you do something, the more experience you get; the more you have a chance to fail at something, the better you get at it. Between our awardees and our mentees, we have over 60 women conductors from 40 different nationalities, and they now have their own community. This is extremely impactful. They are able to talk about the challenges of being conductors, the challenges of raising a family while traveling, the challenges of which cuts to do in a score. Twenty-nine of them are music directors, and they are in positions to be able to engage each other and interact. It’s been incredibly moving to watch that community grow.

These women are not only super talented, the vast majority of them are also committed to their communities in very deep ways. They’ve started tens of initiatives, all kinds of different projects. They’re all about connecting orchestra to community, and I think that’s really the way of the future.

WOODS: When you look back at what you experienced yourself as a young artist, and some of the things you’ve talked about around prejudice and discrimination, do you think things have gotten better?

ALSOP: Oh, yes! Hugely.

WOODS: To what extent does that cohort of amazing women conductors still face some of those same things that you faced? I’m assuming that you believe this is not completed work.

ALSOP: Look at the rosters of the orchestras of the world, and you realize the work has barely even started. That’s a fact. But I’m very encouraged when a young woman will say, ‘I don’t feel any hesitation in going into this field. I don’t feel that I’m being discriminated against.’ That is more the position of young women today. That said, it’s surprising for them when they suddenly hit a wall of the old world that has rather archaic reservations about what women can and can’t do. Sometimes they’re more shocked than I am, because they haven’t experienced it. Things change; things stay the same. I hope we’ve passed the tipping point to progress, and I hope we can lock arms and move forward, especially through these difficult times.

It’s not only about women, but also about American conductors. We have to remind ourselves that the American orchestral business was formed by European emigrees, and we still haven’t really escaped that. We could also talk about repertoire. I go to some orchestras, and they say they haven’t played any American music since the last time I was there. As an American, there’s some reverence that I have or at least I had for America and for American music, and maybe someday that will come back.

WOODS: You alluded to the complexities of this moment. Without straying too far into political territory, it feels like the elephant in the room is that there are big question marks about our public life, freedom of expression in the arts, and federal support. What role does music have in a very turbulent time?

ALSOP: The great thing for me about music is that it’s nonpartisan, that I can sit with a friend who has a completely different political viewpoint, and we can both listen to a piece of music and come away changed. Maybe we have completely differing opinions of it. But they’re all valid.

Music is a great connecting point. As human beings, we’re born hot-wired for music, and that’s something we share innately. Music can offer respite and refuge in difficult times, so it serves many purposes, but I think as soon as it becomes part of a political drama it loses some of its greatness. I understand about making a stand and all of those things, and I make my own stands in my own way, but I try not to do them using the music as that vehicle.

WOODS: We’ve talked about what you’ve done as an agent of change. But I don’t want to lose track of the fact that first and foremost, you’re an artist. When you think about your own conducting trajectory, what remains still to be done for you? I’m not so much thinking here about career, I’m thinking musically. What musical Everests still lie ahead that you haven’t yet conquered?

ALSOP: Some of the musical mountains that have come to me have been sudden and surprising. In my work in Brazil, I discovered a whole repertoire. I had no knowledge of Brazilian classical music or Brazilian popular music—and it’s amazing stuff. I had a swing band for 20 years, and I love a lot of crossover music, this blending of popular and “serious” music. Brazil was a treasure trove on that front. My work in Vienna through the radio orchestra brought me into contact with a lot of contemporary Austrian and German repertoire, which is a language that I wasn’t that facile in and I’ve really enjoyed getting to know. Now I’m working in Poland, and there’s a whole cadre of composers whose names I know, and maybe I had done a piece here or there, but it’s absolutely fantastic music. I have to say, the musical mountains come up naturally and it’s really a great joy. I would probably like to do a little bit more opera in the future. But I’m so happy with my career and the ability to work with great musicians and great orchestras and do the repertoire I want to do. There’s so much out there, and so much to be experienced and explored. I don’t think I’ll be bored a single day in my life.

As orchestras across the U.S. face shifting economic conditions, changing audience behaviors, and increased scrutiny of institutional values, board leaders are thinking carefully about how to lead with purpose. The year, the League of American Orchestras’ National Conference takes place in Salt Lake City, so we asked leaders from orchestras across Utah to share their priorities, challenges, and hopes for the future of orchestral music and how their boards are evolving to meet the moment.

By Piper Starnes

Against a backdrop of economic pressure, cultural change, and a national search for connection and clarity, orchestras remain powerful platforms for music, reflection, dialogue, and joy. In Utah, orchestras are not only cultural cornerstones but also community hubs where creativity, tradition, and civic life intersect.

From fundraising and education to programming and governance, these leaders are focused on helping their orchestras thrive, ensuring that music continues to inspire, comfort, and bring people together across generations. Their comments provide insight into their day-to-day programs, pending projects, and long-term initiatives.

Erik R. Anderson,

President, Murray Symphony

What is your philosophy of governance for nonprofits like orchestras? How involved should boards of directors be in day-to-day operations?

The board of directors of a nonprofit organization, such as a community symphony, is responsible for managing the essential administrative and operational tasks necessary to sustain the organization. By handling these responsibilities, the board enables members to engage in whatever capacity they choose. In essence, a dedicated board of directors allows members to focus on their passions without the burden of bureaucratic duties.

What do you see as your orchestra’s role in your community? How does your board support that work?

Our community continues to support us because we have cultivated an identity that reflects their values, interests, and needs. As the Murray Symphony Orchestra celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, we take pride in our long-standing tradition of providing high-quality, family-friendly, and affordable performances to the Utah community. Some of our members and patrons have been with us for over 35 years, a testament to the enduring impact of our organization.

The Murray Symphony Board is committed to upholding and refining this identity to ensure it remains relevant and meaningful. Our process begins with evaluating the experiences of our own members—how can we strengthen their sense of belonging, even for those who live farther away? What measures can we

take to ensure they feel valued and heard? Equally important is assessing how our efforts resonate with our patrons. Do adjustments need to be made to better align with our mission?

“Our community continues to support us because we have cultivated an identity that reflects their values, interests, and needs.”

– Erik R. Anderson, President, Murray Symphony

What are the most pressing issues and opportunities facing your orchestra right now? For orchestra in general?

A key challenge for the Murray Symphony is selecting music that resonates with both our community and our musicians. Our repertoire must be engaging, appropriately challenging, and appealing to audiences.

To achieve this, we formed the Music Selection Committee, a volunteer group representing all symphony sections. This committee curates our season’s repertoire, balancing artistic excellence with audience appeal. By incorporating feedback from members and the community, we ensure our selections align with our mission and enrich the concert experience.

Patty Bartholomew, Executive Director & Board President, Cache Youth Orchestra

What are the most pressing issues and opportunities facing your orchestra right now? For orchestras in general?

We are finishing up our 3rd year and have four main difficulties right now.

1. Funding: As a new nonprofit, this has been difficult to spearhead. During our first year, we didn’t qualify for many grants because we didn’t have a track record. We had about 60 students during our first year, and most of our funding came from tuition and a few fundraisers and private donations. We have since found an affordable grant writer and have successfully written grants to help fund our program.

2. Recruiting woodwinds, brass, and percussion: This is the first year we have had a full orchestra with woodwinds, brass, and percussion. In our community, string students typically start in 4th or 5th grade. Band students start in the public schools in 6th or 7th grade. This creates an interesting challenge in varying levels between our string and band students. Marching band is also prevalent in our community, and we are trying to navigate the challenge of collaborating with local high schools’ marching band programs so students can successfully participate in our youth orchestra.

3. Artistic vision: As a newer organization, we are constantly trying to improve and fine-tune the artistic

vision and quality of our program. This is a difficult balance; we need numbers (especially in our Philharmonic Orchestra), and we also want to raise the quality. Finding the right conductors and staff has been crucial here.

4. Strategic and active board: Organizing board duties and finding invested board members has been a challenge. As the executive director and board president, it’s been difficult for me to manage both (along with working full-time as a financial advisor and conducting an adult beginning/ intermediate orchestra). Eventually, it would be best to separate those duties and have one person be the executive director and someone else be the board president.

“Playing in an ensemble can impact students academically, increase self-esteem and belonging, and give students a way to express themselves in a beautiful and transformative way.”

– Patty Bartholomew, Executive Director & Board President, Cache Youth Orchestra

What is the value of music and arts education—beyond gaining potential new audiences? Does exposure to orchestral music have a transformative impact? If so, how?

I believe it is vital to our communities. Participating in a youth orchestra (community or school) creates connection and promotes creativity and innovation like nothing else. Our students form life-long relationships with friends and fellow orchestra members. Some of my middle and high school orchestra friends remain some of my closest friends to this day. Playing in an ensemble can impact students academically, increase self-esteem and belonging, and give students a way to express themselves in a beautiful and transformative way. Many of our students will continue to play and perform on their instruments. Our community has orchestra opportunities for every stage of life—from childhood

to retirement—serving all levels at every age. Music unites us and promotes acceptance and empathy.

Blanka Bednarz,

What is your philosophy of governance for nonprofits like orchestras? How involved should boards of directors be in day-to-day operations?

Our common belief is that everything we do needs to be in service of education, operations, and artistic quality. Any ticket revenue or donation we receive goes entirely towards the program, including equipment, artistic content, advertising, paying clinicians, facility rentals, or taxes and legal fees. Not a single dollar is spent on anything else.

We are a small but extremely efficient board. Everyone has five jobs and wears a lot of hats. We’ve unfortunately lost some board members—some moved away, left for a higher-paying or other job, retired, or passed away in the last couple of years—so we are certainly looking for more members who share the symphony’s vision of serving the community, educating young musicians, and collaborating with area entities.

“An orchestra is a very safe environment for young people to experiment. It’s a part of life for them to learn and discover who they are.” – Blanka Bednarz, Executive Director, Utah Valley Youth Symphony Orchestra; Cheung Chau, Artistic Director, Utah Valley Symphony Orchestra

What is the value of music and arts education—beyond gaining potential new audiences? Does exposure to orchestral music have a transformative impact?

An orchestra is a very safe environment for young people to experiment. It’s a part of life for them to learn and discover who they are. If they make a mistake, nobody will get hurt, like in the medical field. Usually, by the end of the year, everybody is much more expressive, open, and courageous, and it really affects the quality of the music. It always sounds better and more beautiful when they are not afraid to communicate. Empathy and awareness of other people couldn’t be more important in today’s volatile world. We foster a supportive and collaborative attitude within our students so that they can truly listen to and learn from each other.

What are the most pressing issues and opportunities facing your orchestra right now? For orchestras in general?

Rising costs. Even mundane things such as [renting] a Post Office box have risen almost 100%. We’ve been extremely lucky to receive donations from parents and friends of the orchestra, and that has helped us remain here.

Though we try to keep tuition as low as possible, we’ve had to raise our tuition minimally. We are all on pins and needles to provide what we can without burdening the families, but we would love to be able to offer scholarships for students in the future. We always tell the parents that it’s cheaper than babysitting for three hours, and here, they are at the dinner table with Bach, Beethoven, Berlioz—you name it! It’s time well spent.

Alyce Stevens Gardner, Chair, Southwest Symphony

What do you see as your orchestra’s role in your community? How does your board support that work?

The Southwest Symphony has been the cultural heart of an expanding and vibrant arts mecca in Southern Utah since 1980. Collaborative, innovative, and education-focused, the symphony

seeks to fulfill its mission to inspire and enrich audiences through the transformative power of symphonic music. We work together with community partners to share this beauty through educational and entertaining performances.

“We work together with community partners to share the beauty of symphonic music through educational and entertaining performances.”

– Alyce Stevens Gardner, Chair,

Southwest Symphony

Recently, the Southwest Symphony partnered with Utah Tech University to provide funding to renovate the Cox Auditorium on campus and transform it into a new performing arts center. Hundreds of generous community donors, including Southern Utah citizens, corporations, Washington County, and the Utah State Legislature contributed to the effort to raise $40 million. The renovated performing arts center will provide a home for the symphony, but more importantly, the new performing arts center will impact generations with state-of-the-art technology, employment, entertainment, and educational opportunities. This project would not have been possible without the leadership, fundraising, and dedication to the arts in our community by the Southwest Symphony board and staff. Their vision and work propelled the project forward, turning a dream into a reality. This project illustrates the impact we can have when we collaborate with our community partners to achieve a common goal.

Brian Greeff, Chair, Utah Symphony | Utah Opera

What do you see as your orchestra’s role in your community? How does your board support that work?

Our mission is to bring our community together for great live music. In a world where every influence and sensation is increasingly digitized or synthesized as

a digital facsimile, ours is one of the last truly “authentic” forms of human interaction. And it happens in a live group setting. There has never been a more vital role for bringing communities together for great live music.

How do you view your organization in light of the growing movement for orchestras to reflect the communities they serve?

We recruit and hire the best, most qualified, and talented people for every role and orchestra seat, and we see that as entirely complementary to reflecting our community.

What qualities make a good board member? How do you build more inclusive boards?

Great board members merge their circles of social influence with the circles of impact of our orchestra. It’s not about donations and fundraising. It’s about deep human connections to mission, purpose, and impact.

“Great board members merge their circles of social influence with the circles of impact of our orchestra.” – Brian Greeff, Chair, Utah Symphony | Utah Opera

What is your philosophy of governance for nonprofits like orchestras? How involved should boards of directors be in day-to-day operations?

Boards should not be in day-to-day operations. Their role is to make deep personal connections across the community...to bring the orchestra into their social spheres and to bring their social spheres into the orchestra. What would you want to tell someone who is new to orchestral music? What cliches would you like to dispel, and what positive impact and pleasures would you point out?

Great music is great music. Period. Every genre of music (and art, generally) is surrounded by cliches. Country, rap, R&B, jazz...all ensconced in untrue and shallow cliches. And every one of them rewards those who listen past the prejudice. What is the value of music and arts education—beyond gaining potential new audiences? Does exposure to orchestral music have a transformative impact?

I believe the entire experience of live orchestral music is what transforms. It is

live, unadulterated, and unamplified by any inorganic means. And it is experienced firsthand by a group of people in that moment for the very first time and the very last time...ever. It is a truly unique and shared experience. That communal experience can be emotionally and spiritually transformational.

Barbara Scowcroft, President, Utah Youth Symphony Orchestra

What do you see as your orchestra’s role in your community?

As the first established youth orchestra in the state, our role is to keep the musical climate healthy, challenging, fun, and positive. UYS musicians go on to have their own private studios, become music educators, and become important patrons of the arts. Many alumni continue their love of music into adulthood and play in Utah’s numerous community orchestras. What qualities make a good board member?

Our board is comprised of parents of Utah Youth students, UYS alumni, Utah Symphony musicians, university professors, and community members. Qualities that make a good board member include:

1. Being in love with classical and contemporary music and the musicians who make it.

2. Having an attitude of openness and learning without a personal agenda to cloud vision, the process, and the progress.

3. Being aware of the diversity of those around us who can contribute to our mission—even if they have no musical training—and giving them space to learn, grow, and test out creativity in alignment with our mission.

“As the first established youth orchestra in the state, our role is to keep the musical climate healthy, challenging, fun, and positive.” –

Barbara Scowcroft, President, Utah Youth Symphony Orchestra

What’s your vision for the orchestra field?

Building on the great tradition of classical music, welcoming new works, and not being afraid to experiment with a concert format will bode well for the future of the symphony orchestra and welcome more people to attend. We are family-friendly and user-friendly. We will continue to remind the public that we are not an elite entity. This strengthens our audience base and shows them that they have a 50% ownership in every concert. The musicians on stage are the other 50%. Together we make a great concert. What is your philosophy of governance for nonprofits like orchestras? How involved should boards of directors be in day-to-day operations?

We are so grateful for the devotion and time of our board members. As they have their own businesses and responsibilities in their personal lives, I think being involved in day-to-day workings of a youth orchestra or professional orchestra is too much to ask and not realistic. You have to live the life of the musician to understand it. It’s not fair to expect someone to understand the nuances and needs of a working musician. What would you want to tell someone who is new to orchestral music? What cliches would you like to dispel, and what positive impact and pleasures would you point out?

Trust! Come into the hall and you will have an immediate understanding of why you should come back. You don’t have to wear specific clothing; you can even fall asleep—it’s a compliment to us as musicians that you’re comfortable with us in our space. Music heals us and expands us. It changes our cells and our souls.

community. Our role is to make orchestral music accessible, meaningful, and connected to the lives of the people we serve—from lifelong concertgoers to students hearing a symphony for the first time.

“In a rural region like ours, the orchestra offers more than performances—it brings people together and creates shared experiences that strengthen community ties.” – Harold Shirley, President, Orchestra of Southern Utah

In a rural region like ours, the orchestra offers more than performances—it brings people together and creates shared experiences that strengthen community ties. Programs like our annual Messiah performance, the high-energy Rock Gold concert, and our youth artist features highlight the talent within our region, while the Children’s Jubilee and educational outreach events help us inspire the next generation.

Whether it’s a formal concert or a hands-on family event, our goal is always the same: to inspire, connect, and enrich our community through the power of live music. If you’re new to orchestral music, or if you’re curious, come and give it a try. You’ll find that every performance is an invitation to discover something new, to feel deeply, and to connect with others.

Music and arts education enrich lives far beyond the concert hall. Exposure to orchestral music fosters creativity, empathy, discipline, and connection—skills that strengthen individuals and communities alike. For many, especially in rural areas, it can be a transformative source of inspiration, healing, and belonging.

Harold Shirley, President, Orchestra of Southern

Utah

What do you see as your orchestra’s role in your community? How does your board support that work?

We see the Orchestra of Southern Utah as one of the cultural anchors of our

PIPER STARNES is a writer whose words have been published by Opera America, Syracuse.com, Rochester City, and Charleston City Paper. She holds a bachelor’s degree from Clemson University in performing arts for keyboard instruments and a master’s degree from Syracuse University in Arts Journalism and Communications. She currently works for the Los Angeles Philharmonic as a creative copywriter in the Marketing Department.

Alan Mason, the chair of the League of American Orchestras’ Board of Directors, may just be uniquely suited to lead the national service organization.

It’s not everyone who forges the kind of path that Alan Mason has taken. He started as a young oboe player in love with classical music while in a youth orchestra; earned several impressive music degrees at several universities; morphed into a professional oboe and English horn player at the Waco Symphony Orchestra and the Louisville Symphony, and then swerved into a “temporary” summer job at BlackRock, the multinational investment management firm, where he stayed for 33 years. All along, he’s been devoted to supporting the work of American orchestras, serving on the boards of California’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Santa Rosa Symphony, and Oakland Symphony, and as board president of the Association of California Symphony Orchestras.

In June of 2024, Mason was elected chair of the League of American Orchestras’ Board of Directors, having been a member of the League’s board for several years. That’s not his only current service to orchestras: he’s also on the board of the Monterey Symphony. Mason brings energy, enthusiasm, and curiosity to his activities; it’s hard to believe that he retired (as a managing

director) from BlackRock a couple of years ago. But Mason has always been busy. He earned a BM degree from Baylor University, summa cum laude, an MA degree in musicology from the University of Louisville with honors, and an MA degree in ethnomusicology from University of California Berkeley. He also taught undergraduate music courses in Louisville and Berkeley. At BlackRock, Mason served on the Global Diversity Steering Committee and was a founding member and global sponsor for the company’s LGBT+ employee network. Mason makes it all look easy; he’s an understated overachiever.

ROBERT SANDLA: What do you view as the roles and responsibilities of an orchestra’s board of directors? What makes a great board great?

ALAN MASON: An orchestra board is like a lot of other nonprofit boards: it has to be deeply committed and engaged with the mission of the organization. Of course, there’s fiduciary oversight, which most boards do well, and I think the League board is particularly good and efficient at that. The other thing that’s really important, and what makes a great board, is a sense of being an

advocate and ambassador for the communities we serve. When you think about the League, it has a broad constituency across the country of large and small communities that are served by our orchestras—as well as communities that could be served by orchestras. Another great element of a board is that it really represents the full constituency of those you hope to serve. With the League board, that means large and small orchestras, geographical diversity, demographic diversity, age diversity, all sorts of things that create a greater sense of inclusive advocacy for all the constituencies that we should be serving, not just today, but in the future.

There’s not a nonprofit in the arts that is without some kind of financial challenges, so the philanthropic advocacy and ambassadorship are very important for the board. It’s important for the Board to help build engagement with those who care about what the organization is doing and hopes to do in the future. When we do that very well, financial support follows, and financial stability for the change we hope to create in the world is supported.

SANDLA: Your phrase “the change we hope to create in the world” stood out. Could you delve into that?

MASON: One of the things that we did in the League’s Strategic Framework that we’re implementing is that we went back to our mission. We hope to serve our member orchestras without question, and that’s a tall order, because they have different needs depending on their size, where they are located, and their financial situation. But we also recommitted to leading change boldly, because if we want orchestras to be vibrant in the future and to have relevance for the total communities that they serve, then we are all going to

What makes a great board is a sense of being an advocate and ambassador for the communities we serve.

have to do some things differently. We’ve been talking about that for a long time, but the action has to be there, and it’s around innovation and inclusion and a real future orientation to make what we do on the stage more relevant to the communities we serve and to a broader set of communities. Having leaders on the board who believe in that vision and are willing to be aligned around it in good times and in challenging times is very important.

I’ve been reflecting on this a lot because, as somebody who led a financial services team during the financial crisis, I was part of a company that was inventing the future of what needed to happen in financial services—things like target date funds for retirement and making it simpler for people to invest for their retirement and have better outcomes; things like exchange-traded funds that made it sort of a more democratic way of people getting exposure to markets. I was part of a company that was doing all kinds of innovative things, and then the financial crisis came. Not only were the financial markets upended, and revenue and expenses were in chaos, but our company had a new owner. The reason I tell that story is because leaders who can stick to the vision of innovation and what’s needed for the future, are the leaders we need right now in our orchestras. We need people who are not going to be overly concerned with market instability, political change, and are going stick to the vision we have for the future of the orchestra field. We need that kind of alignment and commitment. We have it with our League board and League staff and with our members. It’s not always easy. There are times when the culture of alignment and support is challenged because there are things in the macro environment we can’t control—and we are either committed to our vision despite the things we can’t control, or we aren’t.

The League serves the field, and the field needs to be vibrant. I don’t think that there’s one answer for what resilience and vibrancy look like at the local level. What I think we do together is collaborate, support one another, and ask the

right questions. We advocate for policies that enable everyone to do that at the local level. The League is not telling the field what to do, the League is serving the field. Hopefully, it’s also a catalyst for a broad variety of strategies that make the field more vibrant in local areas.

In the Strategic Framework, we talked about the importance of youth. If we want younger people in this country to engage with what we do, then we’re going to have to do some things differently. We know that, but there’s no single right answer to what that looks like.

SANDLA: Related to that is the topic of board diversity and inclusion. The statistics concerning board diversity and inclusion have remained pretty stubborn in much of the nonprofit world. What steps can boards take to become more welcoming to a variety of people of different backgrounds, no matter how you define background?

MASON: I think board diversity is critical. Again, it’s not the same answer for every community, because the composition of a community vis-a-vis what it means to be engaged in that community is different from place to place. There has to be a commitment to the function of nomination or governance, because there has to be a real focus on what voices and perspectives we need to represent. Not just who’s involved with us today, but who might be involved with us in the future.

I’m proud of what the League Board has done in that area, because the League Board represents a variety of functions. We have composers, musicians, board members, have orchestra administrators. We have that geographically; we have that demographically. As a result, the dialogue about how we support our members, and how we convene our members to think about important things in the future, is richer.

It’s very important. It’s the same argument that goes to what happens on stage. If people don’t see themselves represented in governing bodies, in senior leadership roles on the administration side, and on stage, it’s not the same kind of welcome invitation to people to engage with what we do.

SANDLA: We’re in a time of a great deal of upheaval and change on the policy front. You mentioned sticking to the mission, no matter what may be beyond one’s control.

MASON: That’s the kind of leadership that we need right now. We can’t control the challenges or uncertainties that we face; we can’t control the pace of change. But we can underscore our collective beliefs and our vision. We can support each other—musicians, staff, board members, donors—and really stick together. I have no crystal ball on how the uncertainties that we are seeing in markets and in policy will play out. I know that there are easier times and more challenging times to create collective action. And this is one of those moments where our belief in support of each other is very important, as is our conviction to stay with our strategy, even if it’s not as popular as it might have been at another moment.