10 minute read

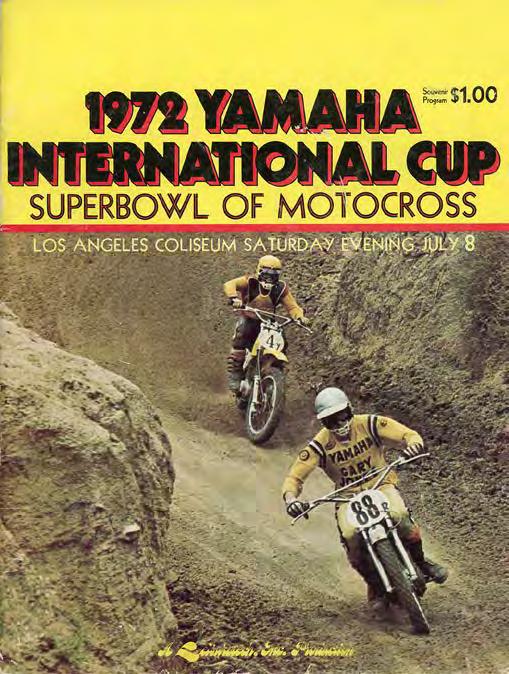

1972 SUPERBOWL OF MOTOCROSS

The First Supercross

A wild look back at the 1972 Superbowl of Motocross — conceived by promoter Mike Goodwin, held in the legendary LA Coliseum and won by 16-year-old Marty Tripes — through the lens of 17-year-old high-school student, photographer and racer Greg Owen

By Mitch Boehm

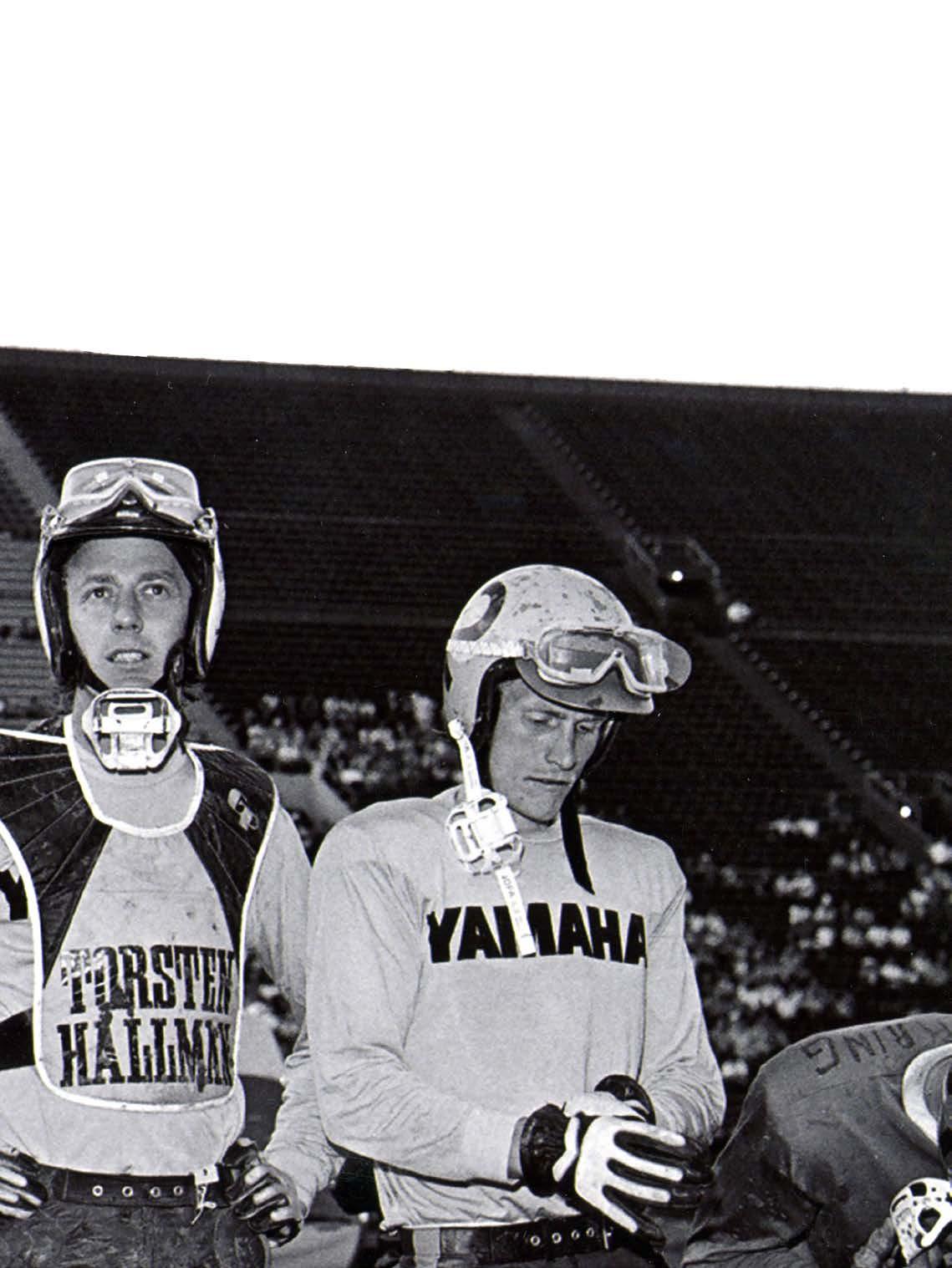

They’re off! Torsten Hallman grabs the holeshot, with Brad Lackey (7), Bob Grossi (6), John Desoto (hidden) and moto winner Arne Kring (21) close behind.

The first Super Bowl — held at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on Jan. 15, 1967 — was a lopsided affair, the Green Bay Packers dousing the Kansas City Chiefs 35-10 on the brilliant passing of Bart Starr, who racked up 250 yards through the air and tossed two touchdowns on his way to earning MVP honors.

The first Superbowl of Motocross, held at that same Coliseum five-anda-half years later, was significantly more hard-fought — and possibly every bit as significant, given what Supercross is today. Sixteen-year-old Marty Tripes, a local boy from San Diego, went 2-2-2 in the three-moto format that evening, snatching the overall win from a trio of very fast European moto-winners — Swedes Torleif Hansen, Arne Kring and Hakan Andersson. But consistency counted in Tripes’ dramatic win, which set the stage for a superb career and, maybe more importantly, helping set the motocross — and, eventually, Supercross — hook firmly in the cheeks of American motorcycle fans.

But even the most prescient observers of motorcycle sport couldn’t see the dramatic scope of what lay just around the corner, in motocross or motorcycling in general. Folks were simply having a great time on motorcycles and enjoying the two-wheeled explosion then taking place in America, the bikes, the racing and the fun — all of it captured so wonderfully in Bruce Brown’s On Any Sunday, which debuted less than a year before Tripes’ dramatic Coliseum victory.

One of those thoroughly enjoying the scene was Greg Owen, a So Cal teenager who’d been introduced to motorcycling at a young age, had been hooked badly like so many of us, and who’d integrated motorcycles firmly into his life.

“We were on a Boy Scout outing in the mid 1960s,” Owen told me a decade ago. “I was 10 or 11. One of the dads had brought a Honda Cub, another a Bearcat scrambler. I got to ride a little, and was instantly in love with bikes. I eventually convinced my dad to get me a bike, a Honda 50, and I must have ridden it up and down our street a hundred times a day for months on end. I was happy to just shift gears and ride!”

Owen, along with his family and brother Kelly, began spending time in the desert, camping, riding and basically livin’ large. “Those were the greatest times of my life,” Owen said. “We’d ride all day, build beer can pyramids from Dad’s empties, hang around the fire at night. From there it escalated. I had a paper route and had saved $100, and my dad helped me buy a Hodaka. I brought it to shop class and hopped it up with a homemade expansion chamber, number plates, bars, a fork brace, etc.”

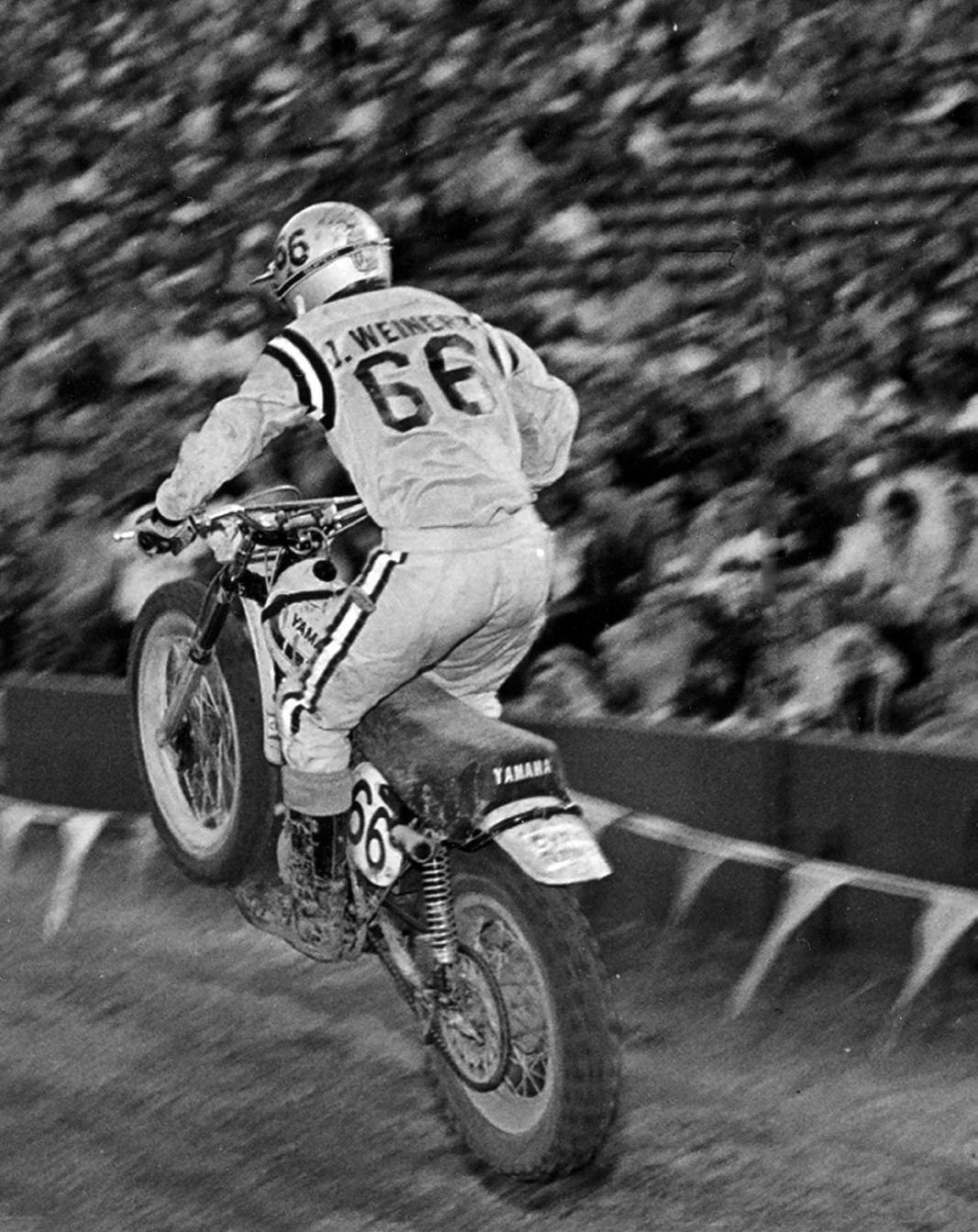

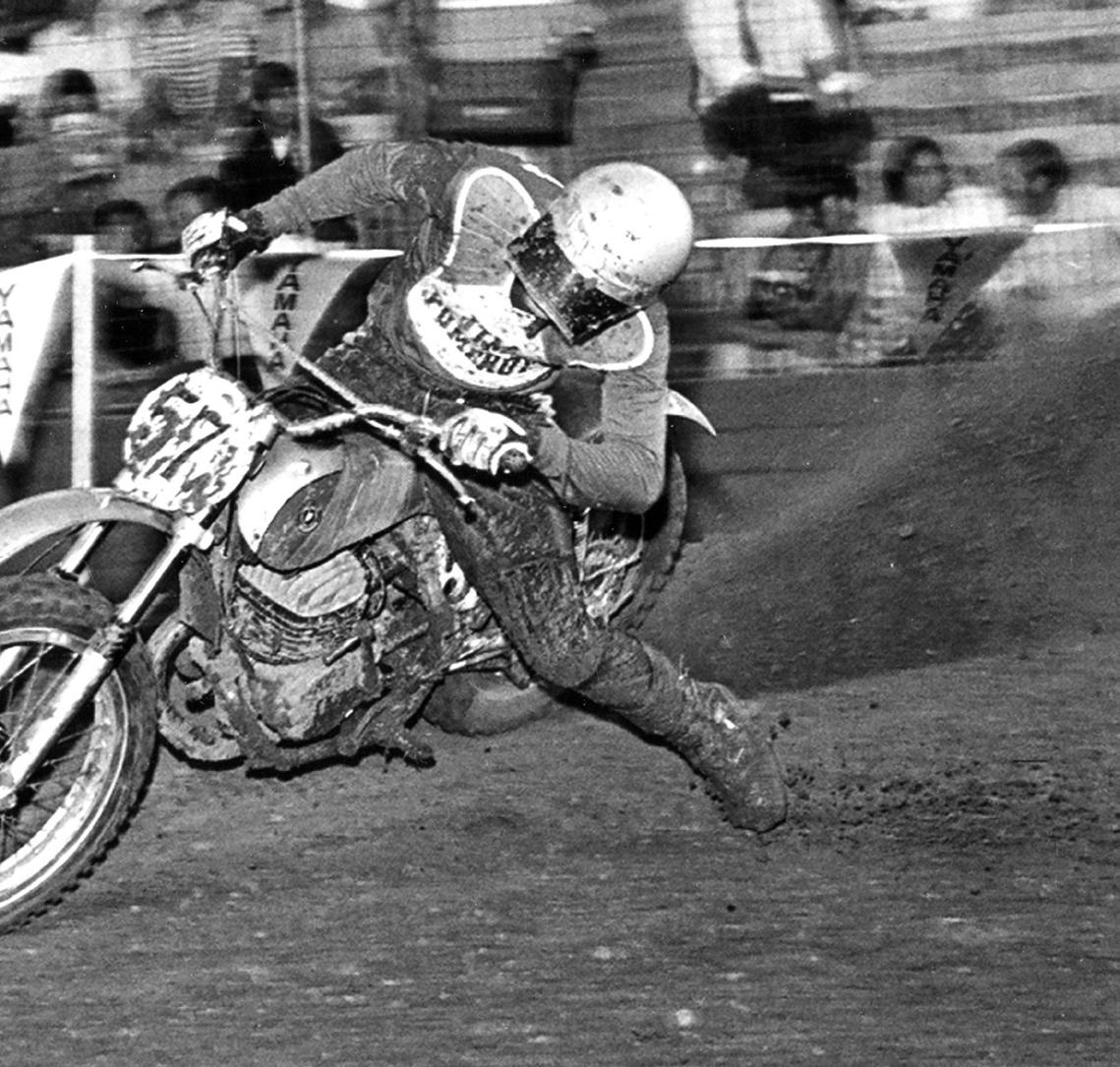

Jimmy Weinert (66) flies past Owen’s camera, his pre-monoshock Yamaha about to thump the dirtcovered plywood and plastic put down to protect the L.A. Rams’ football turf. It didn’t work.

“One day in the desert,” Owen continued, “I saw a race team called the El Banditos with their cool helmets and shirts — and knew I had to race. So I bought an Ossa Stiletto, ran a few desert events, then started motocrossing with my brother Kelly. We had a small budget, but competed as much as we could at Carlsbad and Saddleback, and then at night at tracks like Ascot and Orange County Raceway. Heck, you could race four or five times a week back then, which some guys like [Brad] Lackey, [John] Desoto and [Tim] Hart did to make money for the nationals.”

Money for racing was in short supply, but that would begin to change when Owen’s father came back from Germany with a Rangefinder camera. “I started shooting with it,” said Owen, “and it piqued my interest. I eventually bought a cheap 35mm SLR and learned to develop my own shots. I got to know [godfather of So Cal motocross] Stu Peters, who let me shoot photos and sell them at the races. I’d shoot an event, develop film and make prints all week, then sell

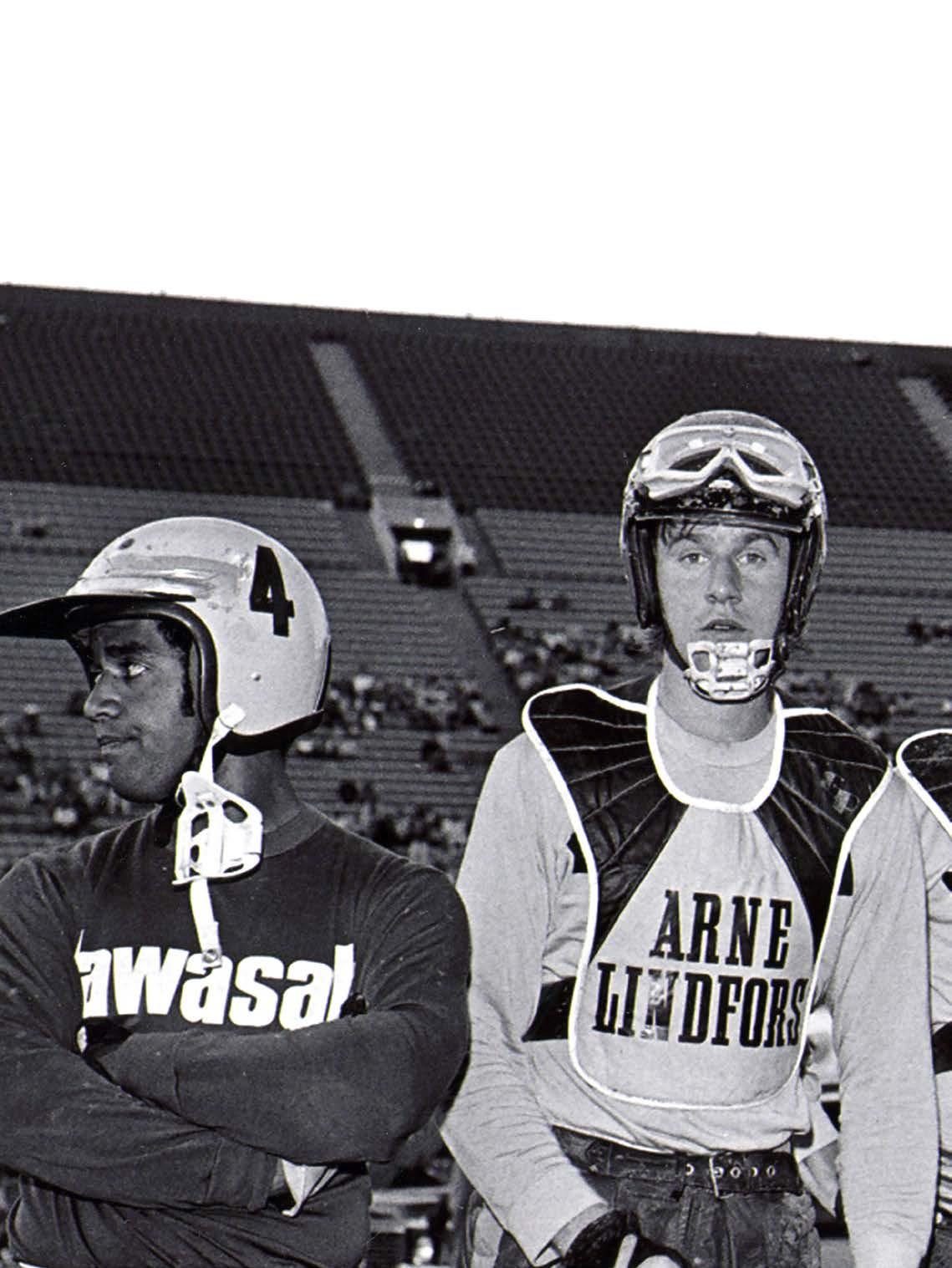

While John Desoto looks away, Swedes Arne Lindfors, Torsten Hallman and Hakan Andersson (right) strategize the best way to deal with Mike Goodwin’s very un-motocross-like racetrack.

“I’d shoot an event, develop film and make prints all week, then sell them to racers the following Sunday for a buck apiece.” – Photographer Greg Owen

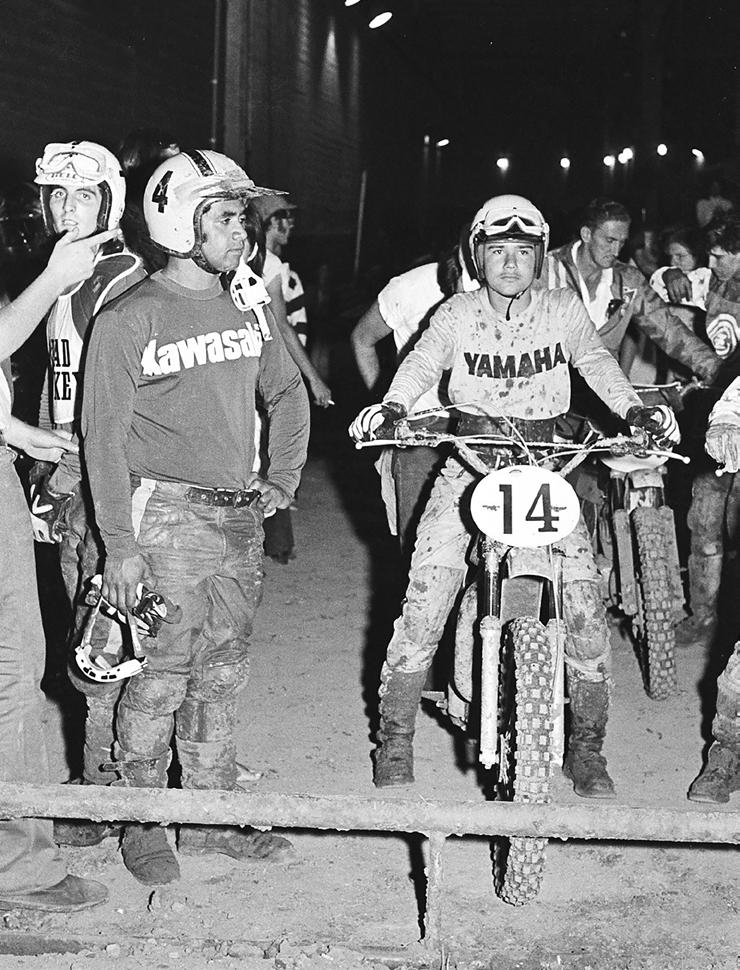

Left: Desoto and Lackey (left) might well be thinking this: “What’s this kid — Tripes, No. 14 — doing here? Isn’t he still 15?” Above: Jimmie Pomeroy, this issue’s cover boy, doing his thing on the Bultaco.

them to racers the following Sunday for a buck apiece. I bought a cheap strobe and started shooting at night races, and selling those photos, too. I still wanted to race, so doing both got tricky. The guys in my class never got photos of themselves!”

“Greg was in his element at the time,” said his late brother Kelly. “He converted his bedroom closet into a dark room, developed all of his own film and printed it old-school fashion. And all while working as a roofer for my father’s company, attending high school and racing three to four times a week at all the CMC events. He made a ton of money at a time when other guys in school were making $2.65 an hour working at McDonald’s. He took a couple of photography classes and that was all he needed. He sold those 8x10s for a dollar apiece, and the riders — and their families — bought them all. It was quite a time for him!”

It was also quite a time for another California motorcycle enthusiast — namely, Michael

Goodwin, a rock music promoter who’d come up with a unique idea for a stadium motocross race after hearing about a dirt track event at Madison Square Garden that had supposedly sold out.

“I figured this new sport of motocross would be really exciting in a stadium,” Goodwin told Racer X, “so I put together a proposal and sent it to Olympia Beer…and they said yes! I then had to figure out how to do it, so I met with Mr. Nicholson of the LA Coliseum. I was scared to death because I knew he was going to say no. Luckily, his kid rode motocross. We went across the street to a restaurant called Julie’s and drew a sketch of the track on a cocktail napkin.”

“I’d heard about the Superbowl thing,” Owen mentioned, “but didn’t know much about it. I got a photo pass through Motor Cycle Weekly. When I got to the Coliseum I started experimenting, shooting color and black and white. The whole thing was very exciting. As the stadium began to fill up you could sense this was going to be a big deal; no one had ever seen anything like it before. I remember being amazed at how they’d transformed the place — a pristine football and track-and-field venue — into a motocross track. I was there early, watching the workers use plastic and plywood to protect the grass.

“Once practice started,” Owen remembered, “everyone there — from the stands to the pits to the folks on the field — knew this was gonna be huge. No one had ever seen anything like it. I remember Jimmy Weinert leaping off this big jump and thinking ‘wow.’ And it got better as the evening wore on, the riders figuring out the track and going faster than ever.”

If those watching thought the track was great, many riders did not, especially the Euros, who bitched about Goodwin’s effort all weekend long. “They were saying it wasn’t really motocross,” said Jimmy

John “the Flyin’ Hawaiian” Desoto (4) cuts under a rider and sets his sights on Bob Grossi (6). Hard-riding Desoto led two Superbowl motos before tumbling badly in a dark corner and again in the water hole. It wasn’t his night.

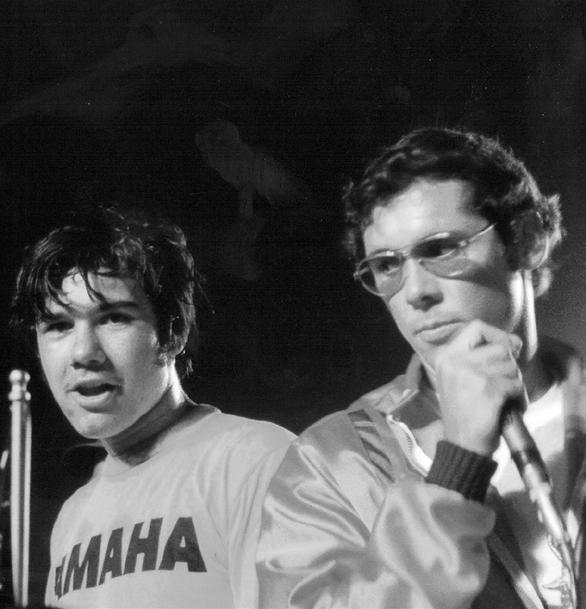

Young Marty Tripes during practice, and being interviewed post-race by legendary announcer Larry Huffman.

Eleven years ago, Larry Huffman (right), the late Tom White (left)and Bryon Farnsworth (middle right) visited Supercross promoter Mike Goodwin in jail, where he’s serving a life sentence for the alleged murder (evidence was in dispute) of Mickey Thompson. Goodwin is in failing health these days, but was overjoyed to see some of his old friends.

Weinert, who didn’t much like the circuit himself. “The jumps were ugly and it was narrow, with no room for error.”

But one rider felt good about the layout right from the start. “Seeing the narrow turns and jumps was just incredible,” Marty Tripes told Racer X. “I couldn’t wait to get out there. I always rode the hills around El Cajon, and did the trick stuff. The track at the Coliseum was perfect for me.” Amazingly, Tripes turned 16 just days before the race.

“I believe our guys had an advantage over the Euros at a track like this,” said Owen. “I’d shot at all the night venues — Ascot, Lions, Irwindale, etc. — and all were slick and tight and had big jumps, just like the Coliseum track. So yeah, all this racing helped them, and that’s one reason they did so well at the Coliseum.”

During the motos Owen lugged his cameras and heavy Norman strobe — complete with heavy lead-acid battery hung around his neck — from corner to corner trying to capture the action uniquely. “I remember shooting that Weinert shot,” he said, “the one of him flying away from me in mid-air. I remember looking for a different angle there, something different. DeSoto was great to watch. He rode with such strength, gassing it in the whoops and just manhandling the bike. Amazing. Another amazing thing was how close the fans were to the bikes. If someone got off at speed, the bike would go right into the stands!”

Owen still remembers the elation at evening’s end, the crowd jumping up and down and cheering for young Tripes, who’d beaten the best in the world. That he’d done it on a venue reasonably alien to the admittedly better European riders didn’t seem to matter much.

Which, by all accounts, seems to have been born that very evening — and at what would become the first Supercross ever.