13 minute read

VILLAGE INTER-AM

World champion Joel Robert, leading the way on his factory CZ in the 250 International division.

Motocross in America — The Early Days

A vivid look at Edison Dye’s Westlake Village, California Inter-Am of 1968 — one of America’s earliest international motocross meets and a race that fertilized the young roots of an American MX dynasty — through the lens of photographer Ed Lawrence By Mitch Boehm

For anyone in the dark back in the late 1960s as to the name of America’s biggest motocross series or the sport itself, the official Inter-AM racing program for 1968 laid things out pretty nicely:

“Welcome to the Inter-AM,” wrote industry pioneer Joe Parkhurst, “[which stands for] the International American Motocross series. The 8-race series comprises the first presentation of one of the most important events on the American motorcycle racing scene. Leading European riders (at this time the best in the world) are touring the country in a spectacular series that began in October at Pepperell, Mass., went to the Midwest for the Mid-Ohio event, then to Wichita, Kan., and to Dallas, Texas.

“This program,” Parkhurst continued, “covers the final four events, [the first of] which will be staged at Westlake Village, Southern California’s newest motocross venue, on November 16/17…” Parkhurst went on to list the final three West coast events in the series — Santa Cruz, Carlsbad and, finally, Saddleback Park.

But it’s the Westlake Village meet — the first international So Cal motocross of that crazy, Vietnam-addled year — that concerns us, mostly due to a cache of wonderful photos shot by a local photographer named Ed Lawrence. They were discovered and eventually acquired by So Cal motocross enthusiast and racer Tom Barnett, who grew up in Westlake and lives there today.

“That ’68 race was a big deal to us kids,” remembers Barnett, who grew up riding dirt bikes in the area, “especially with all the pros from Europe coming over.”

A promotional poster, which touts the sport as “the roughest, wildest and most difficult sport on earth,” lists those riders: Sweden’s Torsten Hallman, Bengt Aberg, Torlief Hansen and Christer Hammargren. Belgium’s Joel Robert and Roger DeCoster. Holland’s Pierre Karsmakers. Germany’s Adolf Weil. England’s Dave Bickers. And others. Radio and print ads for the race appeared all over Southern Cal and excitement ran high, as fans were about to get a glimpse of the European-style motocross they’d heard and read about.

Barnett, whose family moved to Westlake in 1967, remembers those early years well. “I’d just finished 5th grade,” he told me, “and over that summer the neighborhood kids would ride out our driveways and straight into the hills. Westlake was considered ‘the country’ in those years and a lot of Hollywood films and TV shows were filmed there. We’d leave in the morning and be gone all day, returning home (hopefully) in time for dinner. Those were great years, and that first race was a really big deal.”

Today, Westlake Village — which lies 10 miles west of Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley — is a beautiful but typically congested LA suburb, with homes nudging right up against the picturesque mountains that surround it. Expensive homes now dot the area where the track was located, and you’d likely attract the police just by firing up your motocross bike in your driveway. But 50-plus years ago it was a sleepy, out-of-the-way bedroom community with plenty of rolling, open land on either side of the Ventura Freeway, which made it ideal for Hollywood filmmakers and entrepreneurial promoters like Edison Dye, known by many as the “father of American motocross.”

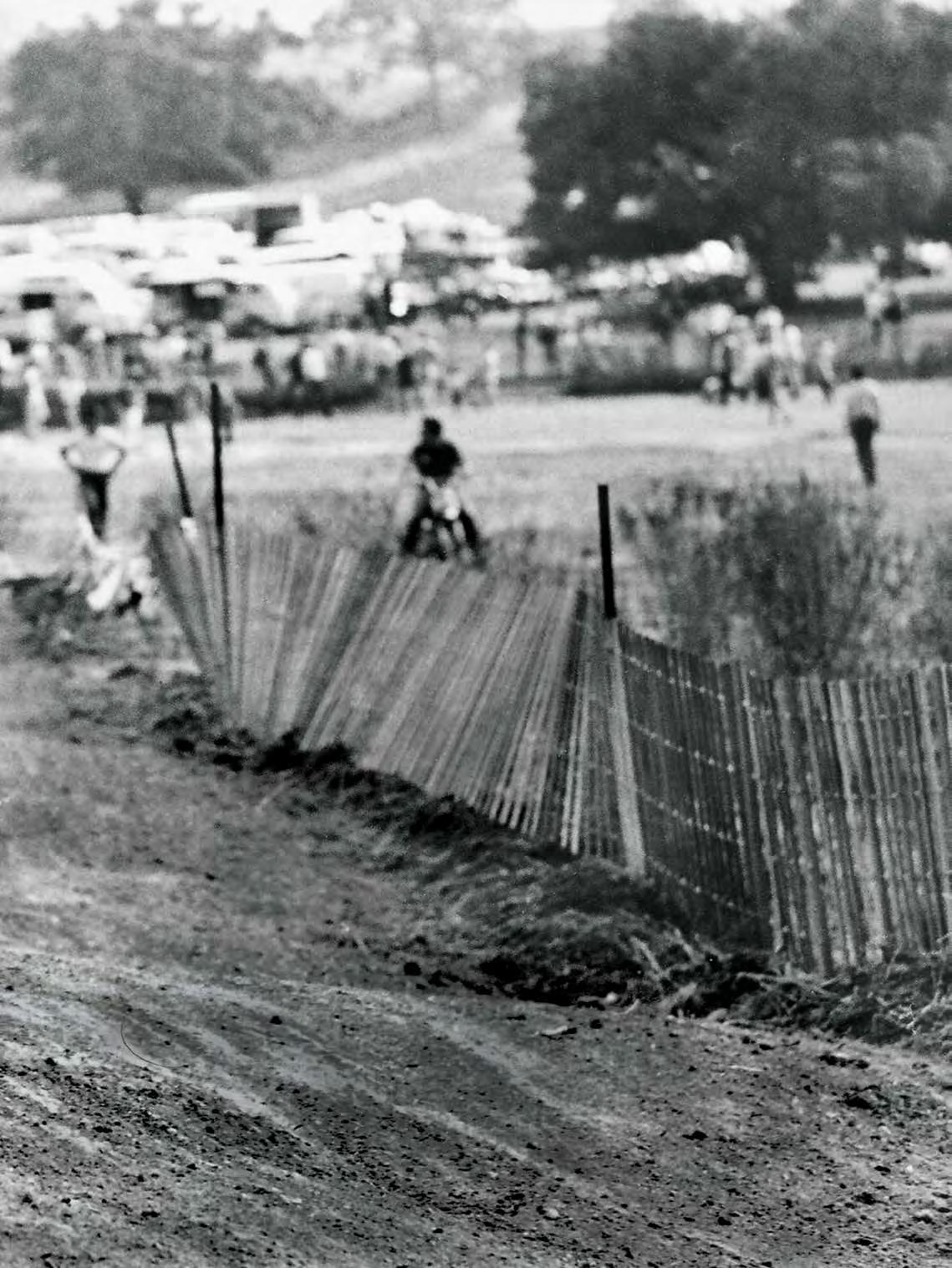

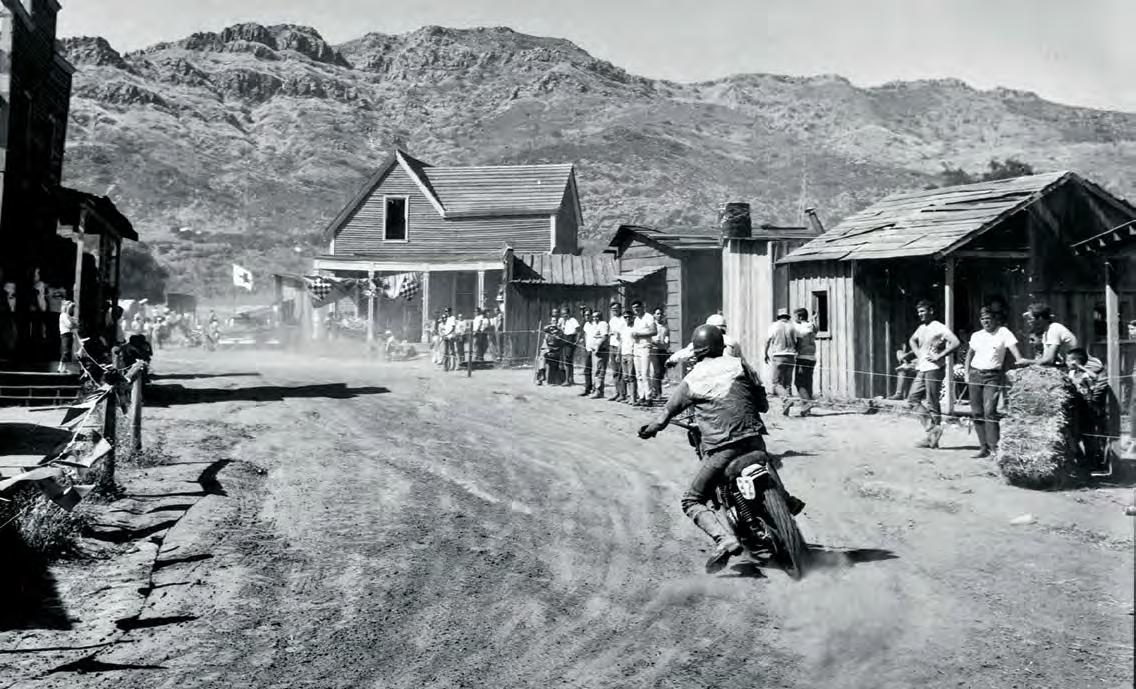

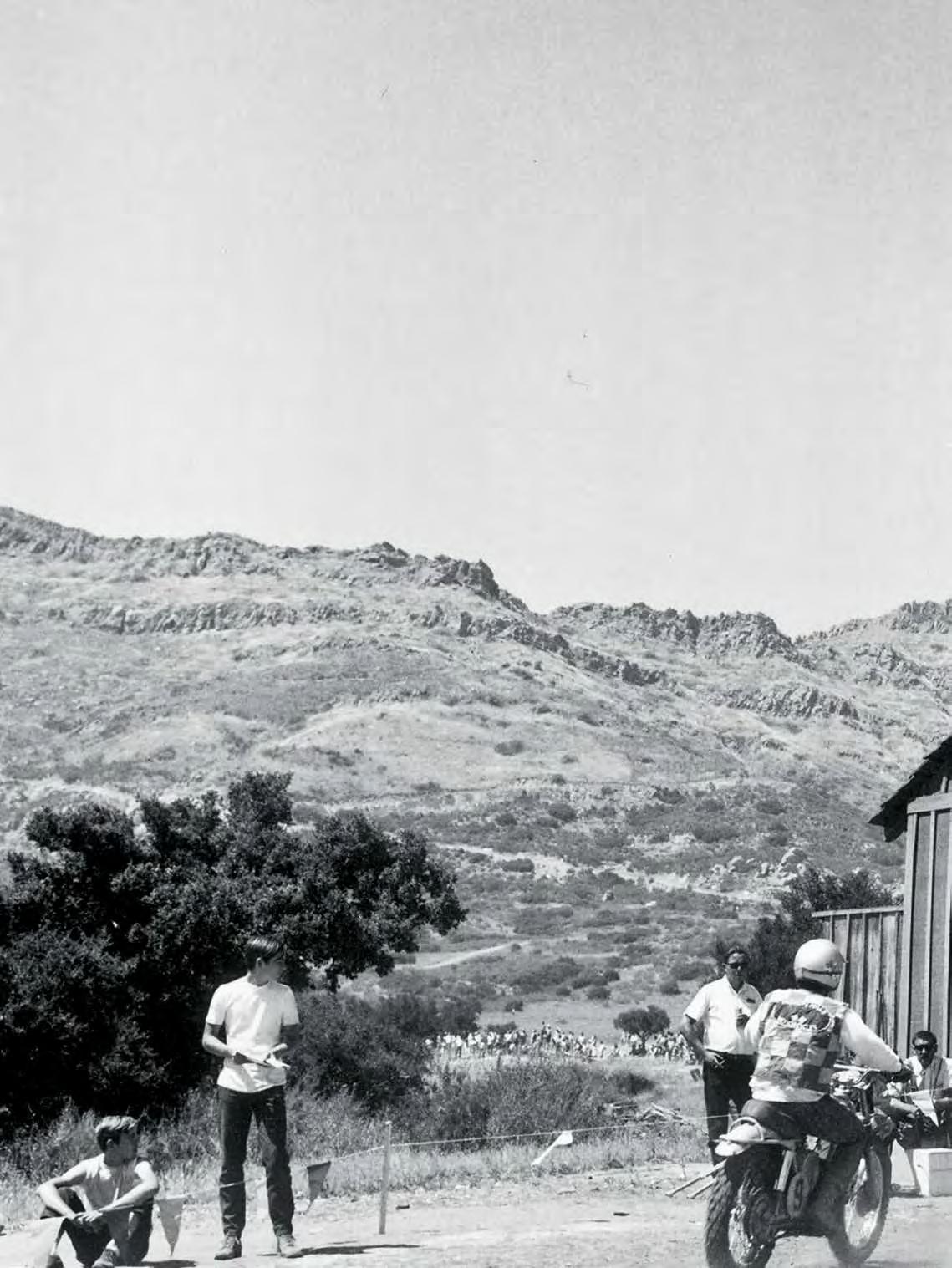

The Westlake circuit was hilly and plenty challenging. Check out the track marshals watching from the roof of the barn, and the lead rider wheelying out of the gully. Left: A rider negotiates the old movie-set section of the track, which came just after riders rode through an old barn (next page).

“These four exciting weekends,” wrote Parkhurst in the program’s introduction, “constitute the climax of an intense effort by Mr. Edison Dye, [who has] traveled the world, spoken to hundreds of people, and spent enormous sums of money to organize the series. Inter-AM marks the first occasion that so many international stars, factory teams and past and present world champions have journeyed to the U.S. in a serious effort to bring this country into the world motorcycle-racing fold. America is indebted to Mr. Dye and his International Motocross company, which made Inter-AM possible.”

Dye didn’t introduce motocross to America. That honor probably goes to the folks at the New England Sports Committee in the late 1950s, according to various moto historians, who were promoting races at Grafton, Vt.’s Bell Cycle Ranch, owned by Maico dealer Perley Bell. Still, Dye introduced a more serious and demanding form of motocross, one practiced by European riders, that was a level or two higher than what American riders were used to with scrambles racing.

Barnett’s early connection with the Westlake track and movie sets imprinted him powerfully with that race and those early riding experiences. “One day while on eBay I typed in ‘Westlake motocross’ and up popped an entry form from the Westlake Inter-AM,” he says. “I bought it and contacted the seller, who said he had a load of Edison Dye memorabilia he’d be happy to show me. A week later I drove to his home and bought everything he had from the Westlake races [there were two, in ’68 and ’69. —Ed]. Dye apparently never threw anything away.”

“Several years later, in 2005,” Barnett remembers, “I was at a nearby historical landmark called the Stagecoach Inn. In the gift shop I spied a calendar that featured a photo of a rider from the Westlake Inter-AM racing down Main Street of that movie set! I’d only seen a few pictures of the race, but I knew if there was one photo there had to be more. So I contacted the photographer, Ed Lawrence, and over the next several years tried to convince him to sell me the photos. He resisted for a long time, but I finally got him to send me the negatives so I could take a look. When they arrived I had them printed, and they were amazing, more so than I ever could have imagined, so I ended up buying everything, negs and all. The motocross community is lucky Mr. Lawrence was there that day, photographing history and doing it so well.”

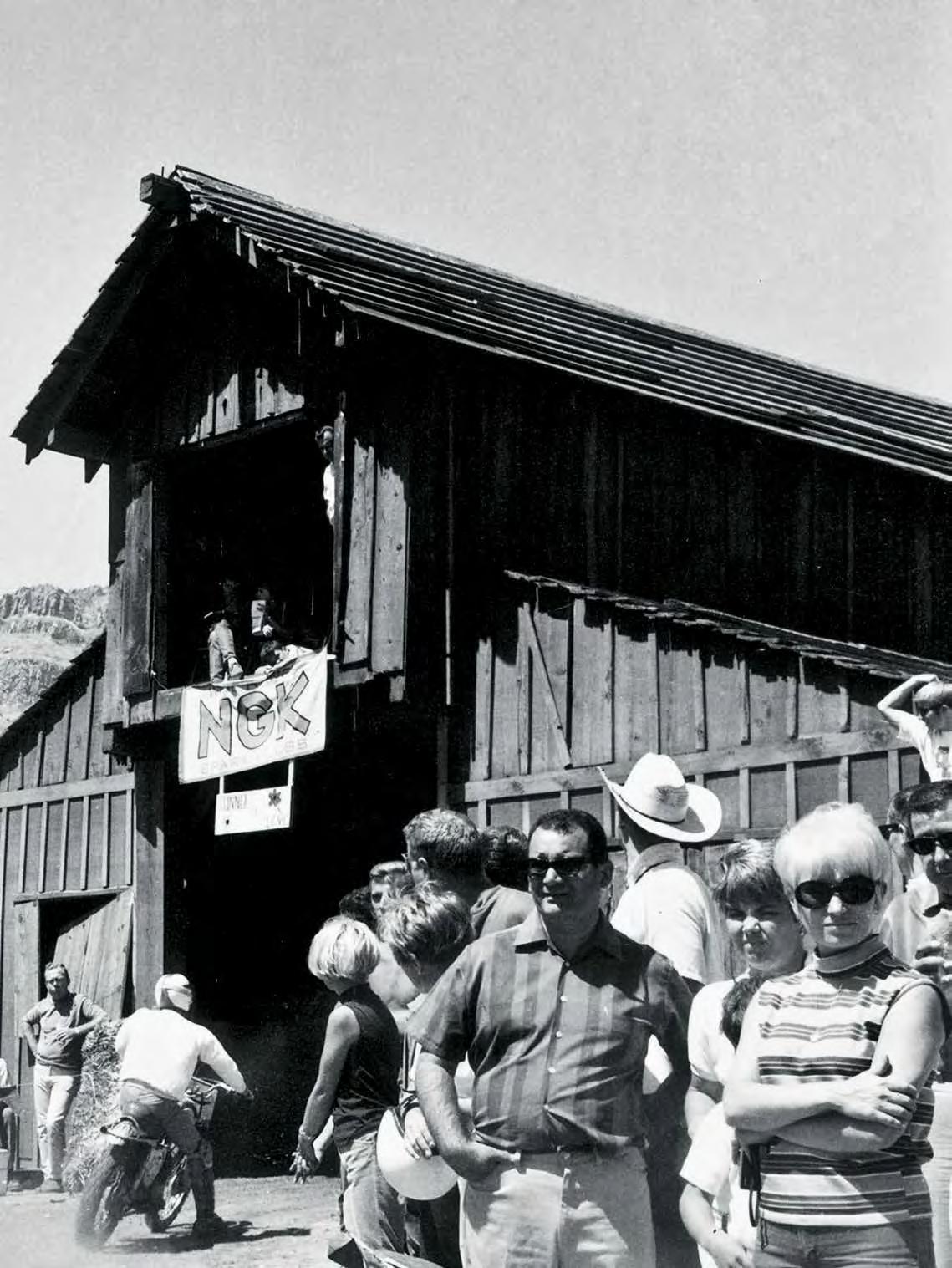

Old barns and spectators basically standing on the track… Oh, the wonderful, freewheeling 1960s!

The black-and-white photos in Barnett’s collection — more than 100 in all — are superb, many benefitting from Lawrence’s non-motorsports background by incorporating plenty of event atmosphere—mountains, spectators, structures and the track geography itself. Lawrence’s excellent composition and the absolute sharpness of the photos put the viewer at the event, a great feeling for fans of motocross and its roots in America.

Barnett and I spent a lot of time discussing and digesting the images. But to get a more personal feel for what the event was like, I invited five of the sport’s legends who actually competed at Westlake in ’68 — Roger DeCoster, Lars Larsson, Gunnar Lindstrom, Barry Higgins and Mike Runyard — to join myself and Barnett for a lunch at Tom White’s Early Years of Motocross museum back in 2010. Runyard, who rode that first Westlake event on a Moto Beta and who went on to ride for the Suzuki factory in later years, was clearly moved by the images.

“Wow,” Runyard said when he spied the photos laid out on tables, “I feel like I’m there! Unbelievable. I can hear the bikes now. The biggest thing,” he said, “was this: We’d seen the Europeans race, and we knew they really were good. We’d watch them and say, ‘Look, he’s standing up all the time.’ Or, ‘Hey, he’s wheelying through that bumpy section…’ But we’d never seen them ride 125s. [Many of the Europeans rode 250s and open-class bikes that day, but many — including world champion Joel Robert — also rode the 125cc Senior division — Ed.] They were pinned everywhere, and never let off. Like wild bumblebees! Everyone was freaked, even the spectators, who’d clearly never seen such a thing. The U.S. riders did not ride like that. And we did not ride 125s, either; it was mostly just 90s and 100s.”

Right: The late Tom White pointing at the bib Mike Runyard (holding bib) wore at the Westlake Village Inter-AM. In the main image, Runyard is No. 155. Back in 2010, White hosted a reunion with some of the legends from the Westlake event. To Runyard’s left are Barry Higgins and Gunnar Lindstrom, while longtime industry insider Bryon Farnsworth is to White’s immediate right.

The track ran right through one of the movie-set barns, which caused Gunnar Lindstrom to comment, “we’d never seen anything like that in Europe!”

Higgins, possibly America’s first factory rider (he got a ride with the Ossa factory in 1970) and the 10th-place overall finisher that day in the 250cc International division, also remembered being shocked by the Europeans’ riding style. “We watched them,” he said during lunch, “but we really didn’t know what we were looking at. We were dumb kids! When [Torsten] Hallman showed up a couple years earlier (during the U.S. motocross exhibition Dye had set up for him across the country in ’66), we heard of him riding three 15- or 20-minute motos. To us, that was a shock. We’d never ridden that much in one day; short sprint races were our thing. Three in a day? Unheard of. Nobody could keep up. Heck, Hallman rode six motos at Westlake! It was a rude awakening for us Americans.”

Lars Larsson, who lived in the U.S. part time and who’d become such a part of the American scene by ’68 he was actually considered part of the American contingent, remembers things this way: “Only Torsten [Hallman] came in ’66,” he said, “for that tour with Edison. It was really the first time most Americans had seen European motocross. In ’67, a handful of us came over: myself, Torsten, Ake Jonsson, Joel, Roger, Dave Bickers and a couple others…We did a few races. I had a contract with Husky in ’67, so I was in the U.S. for months before the series started.”

“The U.S. riders were motocross rookies,” Larsson added, “just amateurs. It was like cat and mouse on the track; we’d play with them. But it was a great time. I ran motocross schools here and spent a lot of time teaching the U.S. riders, and they caught on quickly. To be involved with the birth of real motocross here, and to see what it would eventually become, was just fantastic.” Larsson recorded a 7th overall in the 250cc International race that day.

“America was fertile ground for motocross to explode,” says legend racer Gunnar Lindstrom. “Bikes were cheap, land to ride on was plentiful… the whole situation was so favorable. I think we European riders realized it was only a matter of time before the Americans got real fast and began to win championships…”

“Today you will see the world’s best motocross riders competing in the toughest form of motorcycle racing known,” added Parkhurst in the Westlake program. “For many years we in the U.S. raced at motocross, but called the events scrambles, or rough scrambles. They still are scrambles, but different methods of scoring and organization bring in the term ‘motocross’ — ‘moto’ from motorcycle, ‘cross’ from cross-country. Most of the American riders you will see today possess only a minimum of experience, [but they] are getting better every day.”

The Westlake circuit was laid out over hilly, dry terrain, with a steep downhill/ uphill creek crossing, a couple jumps and a wide starting area. It also ran right through one of the movie-set barns just before the Main Street finish straight, which caused Lindstrom to comment, “we’d never seen anything like that in Europe!”

When laying out the circuit, Dye wanted a very long track, one in the European tradition. But Lindstrom says Hallman talked him out of it. “Torsten felt a longer track wouldn’t allow spectators to see all or most of the action, and also that the PA announcer would lose track of the leaders.” They went back and forth, and Edison finally relented, shortening the course in the back section.

“The track was pretty good,” remembers DeCoster, who himself had quite a bit of track layout experience, having helped design Saddleback Park, Carlsbad and, in later years, the MidOhio Moto Park circuit in Lexington. “It had some up and down sections, which reminded me a little of European tracks. There wasn’t much watering back then, so things got pretty dusty. I was pretty vocal about dust in the GPs, eventually organizing a boycott of a race that was too dangerous due to dust. The FIM was not happy with me!”

Lars Larsson (left) and Roger DeCoster (middle) also attended White’s gettogether, and provided additional insight. That’s Gunnar Lindstrom at right.

DeCoster then alluded to the importance of these first international events, at least in the eyes of the Europeans. “By 1970,” he said, “most of the better European riders were coming here. The U.S. market was booming, and the factories wanted all of us to come and race. There was money to be won, and we won a lot of it!” DeCoster recorded a 3rd overall in the 250cc class and a 10th overall in the 500cc division at Westlake.

Tim Hart, who grabbed a 13th overall in the prestigious 500cc class, related a humorous story about an incident involving world champion Joel Robert. “In practice,” he says, “I found myself out in front of world champ Joel Robert, who I guess had just come out onto the track. Being young, fast and foolish, I started riding really fast — faster than I was able to handle. And of course I crashed, hard, right in front of Robert, literally knocking myself out. Joel came up to me later in the pits and said, ‘Do not try to beat me…you will not!’ He was right. I’ll always remember that…”

You will not. Those words rang plenty true in 1968. But change was coming; the Americans would get fast, and quickly, and the Euros knew it. Soon there would epic and memorable battles, especially at the Inter-AM, Trans-AMA and early Supercross events during the 1970s… And what a glorious decade that was.

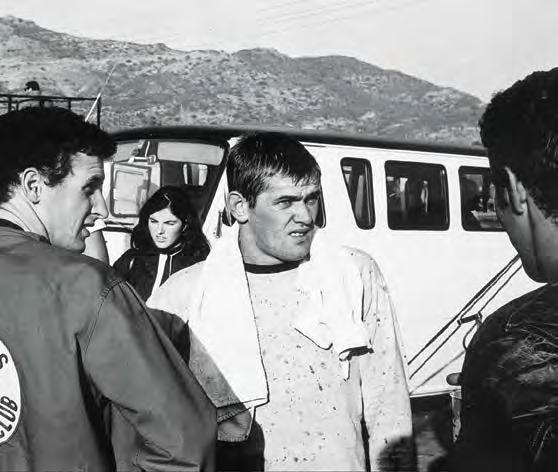

Clockwise from above: The track included a tricky stream crossing at the bottom of a steep gully, which caused a bit of havoc. Joel Robert in the pits with a Dirt Diggers member. Tim Hart launching his linkedfork Guazzoni 125. John “the Flyin’ Hawaiian” Desoto leading David Aldana (11) and Dave Bickers (5). You’ve just gotta love the spectators’ late-’60s attire!