The Journal of The American Boxwood Society – Devoted to Our Oldest Garden

THE BOXWOOD BULLETIN

The Continued Resiliency of Boxwood Event Recaps, Highlights from Europe, Focus on New Cultivars, Winter Bronzing, Box Tree Moth, The Importance of Roots, Garden Spotlights, and More.

The American Boxwood Society is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1961 and devoted to the appreciation, scientific understanding and propagation of Buxus . For additional information on the Society, visit our website at: boxwoodsociety.org

ABS Membership Levels and Benefits

Membership in The American Boxwood Society runs annually. Dues can be paid online or by mail.

Individual .................. $60

ABS Board

President

Ms. Andrea Filippone. Pottersville, NJ

First Vice President

Mr. Kevin Collard. Leitchfield, KY

Second Vice President

Dr. Bruce Chalker. St. Louis, MO

Secretary

Ms. Cheryl Crowell. Winchester, VA

Treasurer

Mr. Mike Gaines. Sagaponak, NY

Immediate Past President

Mr. John Lockwood Makar. Scottsdale, GA

Executive Committee Representative

Mr. Jonathan Kavalier. Vienna, VA

Directors

Class of 2025

Mr. Eric ‘T’ Fleisher. Pottersville, NJ

Dr. Fred Gouker. Geneva, NY

Mr. Jonathan Kavalier. Vienna ,VA

Class of 2026

Mr. James Saunders. Piney River, VA

Mr. Fred Spicer. Highland Park, IL

Position Open

Class of 2027

Mr. Jesse Armer. Kennett Square, PA

Mr. Louis Bauer. Short Hills, NJ

Ms. Kate Kerin. Salt Point, NY

International Registrar

Mr. Lynn R. Batdorf. Bethesda, MD

Executive Director

Ms. Patricia Reilly. Stafford, VA

Boxwood Bulletin Editor

Ms. Shea Powell. Union, ME

Copy Editor

Ms. Adrienne Phillips. Piney River, VA

Benefits: Annual digital subscription to The Boxwood Bulletin, member registration rate for Symposium, member discount for ABS conferences, one vote at the ABS Annual Meeting.

Family .................. $85

Benefits: Annual digital subscription to The Boxwood Bulletin, member registration rate for Symposium, member discount for ABS conferences, one vote at the ABS Annual Meeting.

Corporate/Business .................. $160

Benefits: Annual digital subscription to The Boxwood Bulletin, member registration rate for all employees to the Symposium, member discount for all employees to ABS conferences, one vote at the ABS Annual Meeting

Student .................. $35

Benefits: Annual digital subscription to The Boxwood Bulletin, member registration rate for Symposium, member discount for ABS conferences.

Public Facility .................. $50 (US) | $70 (International)

Benefits: Annual digital subscription to The Boxwood Bulletin plus one printed copy of The Boxwood Bulletin

• Printed copies of The Boxwood Bulletin are available to members for $50 each. Members outside of the United States please add $20 (USD) for shipping.

Contributions

Monetary gifts to the Society are tax-deductible and may be applied to Research Programs, our Memorial Gardens Fund, our Publications Fund, and/or General Operations.

Connect with Us

Email: amboxwoodsociety@gmail.com

Write : American Boxwood Society Headquarters P.O. Box 85, Boyce, VA 22620-0085

Visit : boxwoodsociety.org

In This Issue

4 MANTS

5 ABS Symposium in Chicago, IL

19 Accomplishments of ABS

20 News from EBTS

21 Spotlight on NewGen Independence®

22 Winter Bronzing of Boxwood

24 Box Tree Moth

26 Box Tree Moth Strategies to “Slow the Spread”

27 Boxwood: A Humble and Resilient Plant that Took Over the Garden World

33 Betterbuxus® in European Historical Gardens

36 Update on the ABS Boxwood Memorial Garden

38 Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens

40 Roots: A Growerʼs Perspective

45 Airspading Boxwood

47 Remembering Annie Tatum Newbill Saunders

Letter from the President

My warmest greetings to our valued members! Many of the regions where Buxus is appreciated have been hit hard by the ravages of weather. Wild temperature swings and damaging storms have taken their toll and I am hoping that those who have been affected are recovering. Know that your American Boxwood Society friends are wishing you well. In the past year, The American Boxwood Society has continued to develop both organizationally as well as in our membership. I am constantly in awe at the level of expertise that our members possess and are willing to share with others. A special thank you to those that have contributed articles to The Boxwood Bulletin or to our monthly newsletters. Other members have participated in committee work, preparing for the Annual Symposium, revising the bylaws, and setting a path forward. A summary of this past year’s activity is included later in this issue. Chairs of each of these committees are Board members but all members are encouraged to join; please email us at amboxwoodsociety@gmail.com if you are interested in participating. We still need talents and expertise in the areas of social media, finances and accounting, event planning, and member and donation solicitation.

Shafer are tasked with determining the symposium locations for the next three years. Kevin Collard and ‘T’ Fleisher will research the logistics necessary to fund an internship at Blandy Experimental Farm at the State Arboretum of Virginia. The primary objective of the internship is to focus on the care and enhancement of the Boxwood Memorial Garden at Blandy.

In the past year two special committees were approved by the Board. Jonathan Kavalier and Susie

I would also like to introduce you to our newest board member, Jesse Armer, a horticulturist out of Kennett Square, PA. His appreciation for plants began at a young age when he picked tobacco and tended the family’s garden beds in Lititz, PA. His education in business management was fitting for a position with Davey Tree Experts, attending the Davey Institute of Tree Sciences and becoming its Landscape and Plant Health Care foreman. Today, he works at Longwood Gardens where he leads a team in the Main Fountain Gardens planted with more than 3,500 B. microphylla var. japonica ‘Green Beauty’, and Buxus NewGen Independence®. Jesse is responsible for the new Herb Kitchen Garden which provides produce for local pantries and Longwood’s 1906 Restaurant. Jesse also owns and operates a designbuild horticulture company. In his time outside of work he enjoys gardening at home and spending time with his wife, Joanna, their five children, and many animals. We are fortunate to have Jesse on the Board.

The American Boxwood Society would love to thank all of our current members and donors for supporting this great organization. Our mission is to promote the appreciation, scientific understanding, and propagation of the genus Buxus L. Our push for this year is to increase our membership and educational outreach. Please help us by encouraging your friends to join The American Boxwood Society. We also invite you to support our mission-driven educational efforts by making a donation to the Paul M. Saunders Educational Fund.

MANTS 2024

by Cheryl Crowell

Downtown Baltimore was once more alive with plants and people as the Convention Center again hosted the annual Mid-Atlantic Nursery Trade Show. As a member of The American Boxwood Society team who has attended MANTS for a number of years now, it is always a thrill to experience the excitement and camaraderie that flows from bringing together so many people who love plants!

Your ABS Board has put a lot of thought into our booth the last few years, and we now are able to transport the materials in a van and set up in an hour or less. Believe me, the ease of our new logistic design is a great relief, both at set up and break down. I think of Michael and Helen Hecht and their years of devotion to this event. The thing I really miss is staying at the Hecht homestead as a group and our wonderful conversations, especially in the evening, gathered together at the round dining table.

This year’s MANTS had an almost electric feel because of the over 11,000 paid registrants that attended and the number of people looking for information to improve both their businesses and our shared industry. All the booths were reserved months ahead of time and there was a waiting list of more than 100 ready to jump in if only there was space. Pandemic fears rebounded into a mass frenzy of gardening interest and many of these people wanted to know more about boxwood. An amazing number

of people stopped at our booth to chat, welcoming our handouts about boxwood blight and the boxwood tree moth. There is a lot of interest in boxwood cultivars, especially those with a natural genetic resistance to blight, and we were happy to provide the information they needed!

I’m sure that our presence there helped increase our member numbers and at the same time fulfilled our Society’s commitment to spread knowledge about boxwood, our favorite landscaping plant! It’s time now to prepare for next year’s MANTS in Booth 440. Please consider volunteering if only for a couple of hours. You are sure to meet many boxwood lovers and industry professionals and get to know some of our own members better. We look forward to seeing you there!

2024 ABS Symposium

Chicago,

Illinois

Chicago Botanic Garden

Our annual meeting began with a daylong tour of the Chicago Botanic Garden, a 385-acre non-profit property which is managed as a public/private partnership with the Forest Preserve of Cook County, Illinois. Their mission states “We cultivate the power of plants to sustain and enrich life.” This collection of wonders has many facets ranging from horticulture, herbaria, display gardens, and educational facilities. Our expert guide was Fred Spicer, Director of the Garden and Board member of ABS. Fred delighted us not only with his extensive knowledge of the collections, but also with behind-the-scenes tales of growing the collections, facilities planning, and plant breeding trials.

The garden features 28 very different display gardens encompassing 14,650 unique plants, 60 acres of lakes and 4.8 miles of restored shoreline along the Skokie River. A tram connects all the various parts. There were water gardens, native plant gardens, a model railroad garden, a rose garden, greenhouses, meadows and prairie gardens – even a beer garden! And sprinkled throughout the collection were 33 taxa of boxwood utilized in different ways.

One of our stops was the Regenstein Center where opportunities exist to connect people and plants via horticulture, science, urban agriculture or learning at all ages. This contains a graduate program in plant

biology and conservation, undergraduate research programs and the Lenhardt Library as well as Bureau of Land Management projects. There are two outdoor courtyards in this area featuring a collection of bonsai trees and even bonsai boxwood. At lunch we were treated to a lively presentation by Kevin Collard about the experiences and challenges he has experienced growing many different types of boxwood at his nursery in Kentucky.

After lunch we proceeded to the Malott Japanese Garden, Sansho-En, which is set on two islands in the lake. A respect for nature and age is showcased through traditional elements, a Japanese house laid out so as to hide the lake and the fact that you are on islands. Through the use of “compression and release” techniques of plant placement, and “borrowing the view”, we were led around the garden and could see a third island in the distance – the “Island of Everlasting Happiness”. As the name implies, it was unreachable.

We stopped at a recent addition to the Botanic Garden, the Negaunee Institute for Plant Conservation and Action. This LEED Gold certified building of 16,000 square feet features onsite solar panels to generate electricity, heavily daylit classrooms, and a green roof. This roof serves as a plant evaluation area where plants that will thrive in a non- marine environment are tested. Surprise winners include baptisia, juniper and native blue stem grasses which can grow in soil of only 8” in depth. The roof was irrigated for the first year only and has thrived on its own since then. Plant conservation labs

in the building are used to study/save native plants of the Great Plains in a changing climate. They have over a million seeds in their seed bank and do collecting on behalf of the US government. Nearby

trial gardens are contained by European beech hedges and a hornbeam tunnel adds a wonderful design element to what could be just a utilitarian space.

Our last stop of the day was a fabulous dinner in the Walled Garden, a garden designed by the renowned English landscape architect John Brookes. Here, the garden had six “rooms” including a cottage garden, a pergola garden, a vista garden, a formal garden with herbaceous borders, a daisy garden and a

checkerboard garden. A fountain lent sound to the space, and lush plantings contributed color, scent and texture within the traditional framework of an encompassing brick wall. The setting sun created a beautiful quality of light that enlivened the plantings and created a memorable end to a wonderful day.

By Susie Shafer

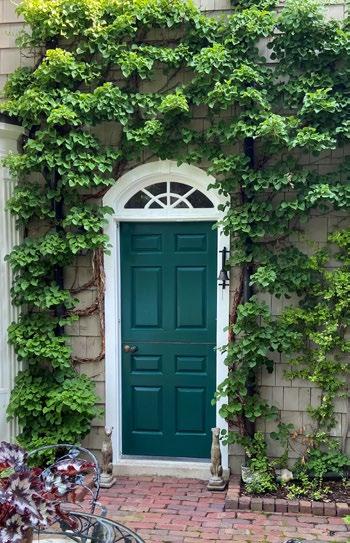

Annual Symposium featured a full day touring beautiful private gardens in the exclusive and breathtakingly beautiful neighborhoods of Lake Forest and Lake Bluff, Illinois. Our first stop led us to a quaint, delightful, and diversely-planted garden created and maintained by the owners. The long driveway was sheltered by an impressive grouping of mature bur oaks which created a buffer from the tiny street as well as helping the home to blend in seamlessly with the garden. Rounding the corner of the beautiful home led to an intimate patio of antique brick, climbing hydrangea and a very photogenic

Dutch door. To the rear of the home was an impressive boxwood and rose parterre complete with fountain and moss-covered stone perimeter knee wall. Each axis of the parterre seemed to beautifully frame views into the adjacent garden spaces. Finally, a koi pond surrounded by lush mixed plantings greeted us, creating a less formal but still structured space inviting you to stay a while and relax. The homeowners’ intimate knowledge and love of their garden was very apparent and greatly appreciated by our group.

by David Schurr

Camp Rosemary

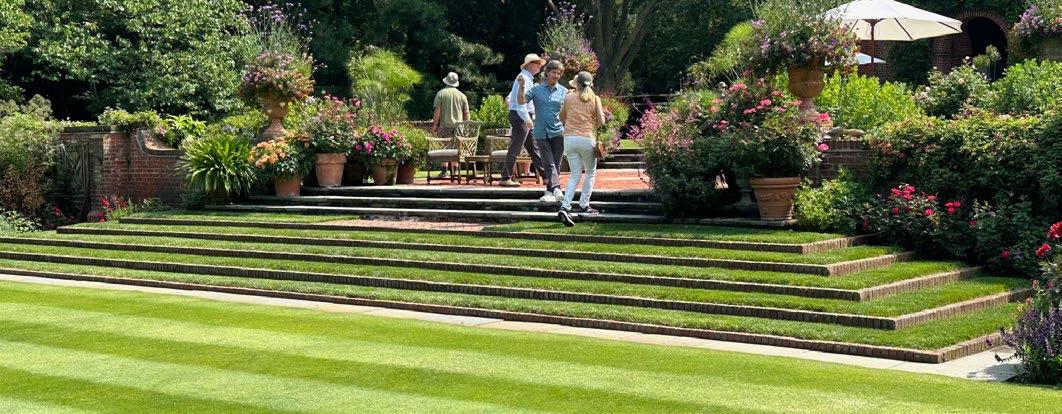

Arriving at Camp Rosemary, we walked down a drive lined with formally pruned little-leaved linden trees. As we approached the grand home the shade opened into a wide courtyard befitting the beautiful brick building that Rose Standish Nichols and her husband called home. Fred Spicer then introduced us to the caretaker of the home and we began our walk through the magnificent English garden.

The 9-acre estate seemed much larger as we strolled through one garden room after another. Huge trees (an ash in particular) in the distance offered views,

yet many gardens were hidden until you reached their boundaries before revealing themselves to you. Expansive lawns, one as trimmed as close as a putting green, created a flow through the grounds and provided ample space for both large and small events that were known to be enjoyed here. Flowers grew profusely in almost every garden room, the ones closest to the house and pool being the most colorful and seeming in perfect bloom. We could tell that flowers were much loved by the owner, and the gardeners continue to maintain them as if the family were still in residence.

Being boxwood lovers, our group appreciated the boxwood incorporated into most of the gardens. Many were carefully sheared, some left to develop into their own type of sculpture. As is often the case, we found beautiful sculptures carefully placed among the boxwood, which in turn provided a cool and soothing background for the art. In particular, the white garden offered up a pair of sculptures of Chinese ladies as the reward for strolling past boxwood and Annabelle hydrangeas.

Those among us looking for parterre gardens were not disappointed. The pool house had beautiful knot garden parterres on either side as part of the fun as did various terraces near the main house. As we enjoyed our garden adventure around the pool, we were greeted with some delicious refreshments on the terrace and treated to a tour of the pool house itself. The delicately painted flowers tracing the doors

and windows brought the outdoors inside and framed a large table set with glass and crystal as it would have been for guests and family, a sparkling crystal chandelier overhead.

After filling up on the yummy treats, we continued to wander past a pergola with potted boxwood scattered along the way and then to a more wooded and whimsical garden before exiting to our bus. One could feel the kind generosity of spirit that enveloped this wonderful property; an inspiration to work harder in our own gardens and then to share their beauty with others.

by Cheryl Crowell

Crab Tree Farm

We drove a long way after turning off the highway into Crab Tree Farm, the last operating farm on Lake Michigan in Illinois. We passed pastoral fields of grazing sheep and cattle lazing under large shade trees. We were transported back to another time when we glided past what seemed to be ancient buildings next to placid ponds or small rivers. Leaving the fields behind we slipped into a managed forest with an understory sheared level at a four-foot height. The vegetation was just short enough to be able to see deer walking beneath the trees.

The forest gave way to the grounds of the main house, a magnificent structure set in a sea of green grass, but your eyes were immediately cast to the expanse of blue behind the house, Lake Michigan.

At the front of the house with the distracting view hidden for now, we walked through a charming boxwood parterre garden with fragrant roses filling the voids of embracing boxwood. Twisted trees added a third dimension to this bucolic scene and you could easily imagine that you were in an English country garden.

The homeowner joined us for our walk through the roses and well-pruned boxwood before we headed around the corner of the house. We all gathered at the edge of the cliff and just stood for a long time where manicured grass fell away into the natural growth along the lake. What a spectacular view! Benches marked the best viewing spots and we enjoyed their comfort until it was time to move on. There was so much more to see!

At this point we entered a forested area and followed what seemed like animal trails as they meandered along. We passed a bridge and triangle pavilion and both traditional and modern statuary, an unexpected treat as we walked to the most unexpected building! We entered an old English study and what turned out to be living quarters that opened up into a threestory tennis pavilion. What a grand time was once had here! The walls were covered in English ivy, and the ceiling was made of glass, giving the feel of being in an atrium. Our tour guide gave us many facts, but what I remember most was that there used to be many similar complexes in the northeast to allow indoor exercise when the outside was covered with snow. Not many of them remain today, an era that has passed.

Continuing past this surprise in the forest we followed trails to other buildings, some with magnificent boxwood parterre gardens and terraces. A wonderful greenhouse owned by a calico cat sat next to a lovely vegetable garden pretty enough to be anyone’s main garden. Back on the bus we went to another part of the property, a surprisingly modern home set in pasture-like lawn. Reflecting pools mirrored the sky and a sizable outdoor terrace overlooked the pastoral vista. Following around the house we walked into a pergola of live sycamore trees pruned to create a flat canopy of shade overhead. Walking to the end you were surprised by a piece of “The Bean”-a prototype created before the famous reflective sculpture was placed in Millenium Park in Chicago. This piece of history added a bit of fun to the afternoon when everyone looked at themselves in “The Bean’s” shiny surfaces.

The last stop was at the barns you were certain came straight from “Olde England. ” The setting seemed to spring from a movie, with chickens, ducks, and geese enjoying free range over the landscape. Our final scene as we pulled away was of a pond filled with swans and overhung with willow trees skimming the water with their branches. We were fortunate indeed to be able to see this snapshot of pastoral bliss on the last farm on the Illinois shore of Lake Michigan.

by Cheryl Crowell

Ravine Garden

Ravine House, the last of a great series of places we visited, had some of everything: a history of prominent owners, a renowned architect, some of America’s famous landscape designers, periods of decline and painstaking restoration that brought it all to a remarkable present.

The house was built for Mr. and Mrs. Henry Axtell Rumsey in 1912. The design of the house was modeled after an English manor in the pre-Georgian Baroque style of Christopher Wren. It was designed by Charles Coolidge whose firm also designed Stanford University, the Chicago Public Library, and the Chicago Art Institute. Rumsey was an important figure in Chicago business, and served as mayor of Lake Forest from 1919–1925. He originally intended to

hire Frederick Olmstead to design the grounds, but in 1913 decided to use Jens Jensen. While Olmstead may be the best-known American landscape designer, Jensen, a Dane, has fairly caught up to that fame as his innovative use of native plants and naturalistic work has now become so popular.

The Rumseys had to leave Ravine House in 1931 when the Great Depression led them to retreat to their residence in Chicago. During WWII, the house was used as naval officers’ quarters. Not until the 1980s did the estate begin to see improvements with a new garage and then a family room and pool and poolhouse. Since the 1990s, a great deal of attention has been given to the landscape.

The public road at the front of the property is completely hidden by a spruce woodland. We began our tour at the Mayflower Ravine, the area where much of Jensen’s work had been focused and which showed the most recent improvements. I didn’t have great expectations of seeing a wooded naturalistic ravine in late summer. But it did not take long to recognize that this was a restoration miracle. Little details began to reveal the huge amount of effort it took to raise the streambed five feet and to replant the once-scoured banks with 40,000 perennials and countless shrubs and trees. And it was a beautiful, vivid green with more than a couple of my riparian

habitat favorite plants, Rubus odoratus and Napea dioica. And typical of Jensen, there were also wooden bridges, contemplative spots to sit, and a Native American Council Ring.

Other landscape features included a perennial border in the English style, the East Formal Garden and the Spa Garden. A surprising addition to the plantings was a Taxodium that caught everyone’s attention. Flourishes of colorful annuals enhanced these creations and it was all anchored by handsome boxwood hedges.

by Louis Bauer

We Love Our Members

Accomplishments of The American Boxwood Society

ABS officers and committees report their accomplishments at the ABS annual membership meeting. Work regarding the revision of the bylaws and increasing membership are of foremost consideration, but other achievements are also noted. As you read about these successes, remember that much of the work is done by volunteers from both the ABS Board and members.

The Bylaws Revision Committee was led by Lynn Batdorf. Committee members Eddie Goode, Bruce Chalker, and Andrea Filippone were assisted by the Executive Director. The revised bylaws were submitted to the Board and subsequently to the membership to receive feedback in advance of a vote to approve. The bylaws revision was adopted without opposition on April 28, 2024.

The Development & Membership Committee is tasked with efforts to recruit and maintain the membership, and to conduct fundraising activities. The committee chair, Kate Kerin, is joined by Jonathan Kavalier, Fred Gouker, Louis Bauer, and Eric ‘T’ Fleisher.

On the membership side:

• Membership grew 56% in 10 months.

• For the benefit of the membership, the committee suggested that the membership year be changed from May 1 to the date that dues are paid.

On the fundraising side:

• Given the high production cost of The Boxwood Bulletin, they recommended that ABS provide digital copies as a member benefit but charge for print copies.

• Dues had not been increased for about a decade and to balance revenue with expenses, the committee proposed a modest dues increase.

• Donations for the year totaled almost $6900.

The Communications Committee’s duties are closely tied to those of the Development and Membership Committee. The goal was to increase communications to grow the membership. The committee produced

The Boxwood Bulletin, which was distributed last fall and, in keeping with trends, in electronic format. Committee members and many members contributed articles to The Boxwood Bulletin. The team disseminated the monthly newsletter and other messages of timely information to more than 1500 subscribers. To promote our mission, an attractive and current website is required. The website has been updated more than 20 times in the past 10 months. These jobs were largely accomplished by Editor and Webmaster Shea Powell, in cooperation with Chair Bruce Chalker and members Andrea Filippone, Jonathan Kavalier, Cheryl Crowell, and ‘T’ Fleisher.

The Executive Committee consists of President Andrea Filippone, Chair, and members 1st Vice President Kevin Collard, Treasurer Mike Gaines, Secretary Cheryl Crowell, Past President John Makar, and Director Jonathan Kavalier. As part of the duty to conduct the day-to-day business of the society, they:

• Recruited staff for the ABS booth at the industry’s premier trade show, the Mid-Atlantic Nursery Trade Show in Baltimore.

• Promoted the annual symposium with a special invitation to the Boxwood Society of the Midwest.

• Began negotiations with author Lynn Batdorf on the role ABS would play in the dissemination of Boxwood, An Illustrated Encyclopedia, Second Edition.

The Finance Committee consists of Treasurer Mike Gaines, Fred Spicer and Kate Kerin. Prior to submission to the Board, reports were reviewed and found to accurately reflect the financial standing of ABS. Each member of the Board has fiduciary responsibility to the ABS so the committee offered Board members an explanation of each of the reports and questions that Board members should be asking about the Society’s financial standing. The committee drafted financial and conflict-of-interest policies for the Standing Rules and a budget.

Questions or comments about the annual reports may be addressed to amboxwoodsociety@gmail.com

News from the European Boxwood and Topiary Society (EBTS)

The year 2023–24 has been busy and interesting for us in the EBTS and included the following:

· EBTS France held 20th anniversary celebrations in Le-Touquet-Paris-Plage in November 2023 following a devastating storm there

· Topiary featured in the opening ceremony of the Paris 2024 Olympics - see www.ebts.org for the report and photographs on Olympic Topiary

· EBTS country groups’ activities included an EBTS UK trip to explore Denmark’s gardens and an EBTS France trip to the island of Sicily

· TOPIARIUS editor Elizabeth Hilliard was a judge of the new national topiary awards - created by Henchman Ladders – held in the UK this year but next year open to gardeners across Europe

· April 2024 saw the publication of Volume 28 of our beautiful magazine TOPIARIUS including:

° Proven spraying schedule of EBTS Belgium chairman, professional nurseryman Karel Goossens, who by following this timetable never sees a box tree moth caterpillar in his huge topiary nursery

° Focus on France - fabulous gardens including creations by William Christie (symmetrical, theatrical) and the late Nicole de Vésian (wild and brutal), and the winner of the biennial French Grand Prix of gardens and parks with topiary

° News from EBTS countries across Europe, including Lynn R Batdorf’s visit to Germany

° Science - all the research taking place across the world to combat the box tree moth

° Topiary ballet - Edward Scissorhands, funny and moving production by New Adventures Company at Sadler’s Wells, in London and on tour

° Book reviews and art - topiary books for children, and the painting of topiary in Levens Hall gardens which changed the artist’s life

The European Boxwood & Topiary Society

EBTS is a ‘not for profit’ pan-European organisation that aims to encourage and enhance knowledge of boxwood & topiary through garden visits, publications, promotions, exhibitions and scientific research.

Our members comprise garden designers, historians, writers, scientists, great garden owners, nurserymen, as well as the many garden lovers who are the backbone of the Society

Why not sign-up to our email newsletter to keep up to date with the latest news, or better still, become an EBTS member to receive our journal Topiarius which has boxwood and topiary articles and reviews covering history, science and art, plus our exclusive garden visits which you might like to attend if you are planning a visit to the UK or Continental Europe. info@ebts.org

Spotlight on NewGen Independence ® Classic

Boxwood Beauty

NewGen Independence® (Buxus ‘SB 108’ US PP28,888), the very first boxwood selected for the NewGen® program, is still considered to be the most beautiful by Bennett Saunders, Saunders Genetics General Manager. Good resistance to boxwood leafminer and boxwood blight with proper care round out the package! Disease and pest resistance is critical for any boxwood to be included in the NewGen® lineup. But as Paul Saunders Sr., Bennett’s father, noted, the “WOW factor” is essential in bringing any new selections to market. Bennett concurs: “That boxwood has to stop you in your tracks, and a well-grown NewGen Independence® does just that – it’s a gorgeous plant.” It has gained popularity as a replacement for ‘Suffruticosa’ (English boxwood)which is extremely susceptible to boxwood blight. Glossy, deep-green foliage (no winter bronzing)

graces this medium-sized boxwood with a wellbranched, rounded habit, reaching 3 to 3.35´ tall and as wide in 15 years. While hardy to USDA Zone 5b, note that if some branches produce a second flush of foliage in the fall, they may be susceptible to winter burn. Just snip off any light tan, damaged foliage in winter or early spring. Perfect for pruning into a globe or sheared into a hedge, NewGen Independence® is featured in the Rose Garden at the White House and in the recent renovations at Longwood Gardens. Ask for NewGen® boxwood at your favorite independent garden center. Landscape professionals can reach out to our 30+ NewGen® wholesale nursery growers across the country. Find out more at newgenboxwood.com

by Holly Scoggins, Program Manager - NewGen® Boxwood

Research from Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories Investigates

Winter Bronzing of Boxwood

It has now been a few years since I caught the seemingly contagious “boxwood bug” and joined the ABS. Accompanying a small group on the 2022 trip to Italy with Ron and Linda Williams was surely the highlight thus far, but I am grateful that my dayto-day work at Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories affords ample opportunity to learn more about boxwood culture and care. At last inventory, the grounds had nearly 700 individual boxwood plants, representing roughly 70 accessions.

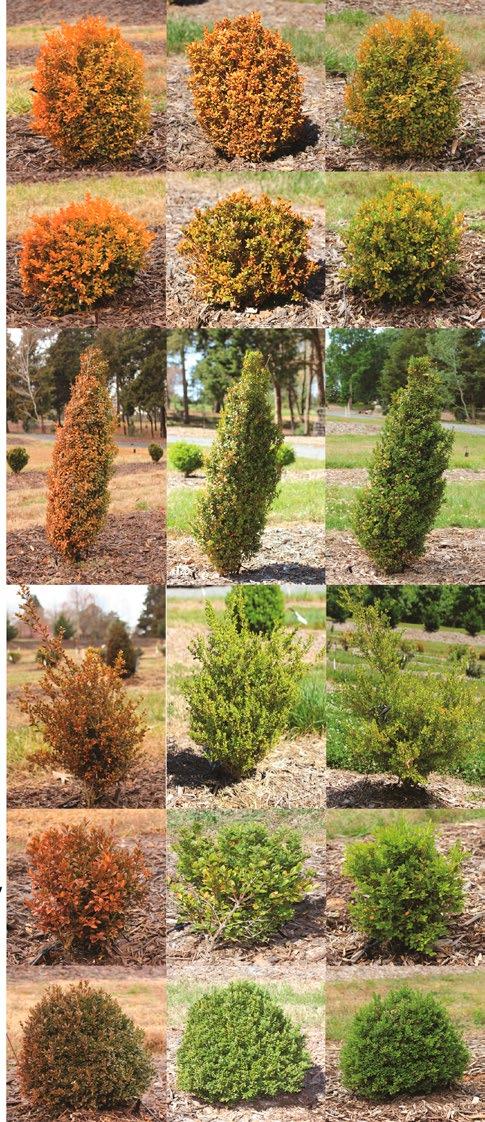

Two of my research team colleagues, Dr. Andrew Loyd (plant pathologist) and Dr. Drew Zwart (plant pathologist and physiologist), recently published the results of a multiyear study designed to learn more about the reversible color change known as winter bronzing of boxwood (not to be confused with winter damage). They assessed an extensive range of species and cultivars (40) to rank winter color change and recovery, then focused on the effects of shading, available nutrients, and fertilizing on bronzing. What better place than here to discuss some of the findings?

To be sure, knowledge that some boxwood show dramatic changes in foliage color over winter months is not new. Sources such as the Saunders Brothers Boxwood Guide offer helpful notes that Buxus microphylla var. japonica ‘Green Beauty’ “has deep green glossy foliage with little winter bronzing,” or noting that Buxus microphylla var. japonica ‘Winter Gem’ “tends to bronze when exposed to direct winter sun, but the bronzing will quickly disappear in spring as temperatures rise and as new growth emerges.” In Boxwood: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, Lynn Batdorf

includes in the first chapter a cautionary paragraph stressing the importance of optimal site selection to

protect from excessive direct sun and wind exposure during winter, conditions closely associated with winter bronzing.

Still, there remains confusion on the topic among less experienced circles. Loyd and Zwart point out that, “Despite abundant documentation to the contrary, it is very common for arborists and other landscape professionals to attribute winter color change, or winter bronzing, to nutrient deficiency and recommend fertilization without performing soil or foliar nutrient assessment (author’s personal observation).” This is the crux of the matter and drove the need to expand and clarify our knowledge of winter bronzing. “Unfortunately, many abiotic factors that negatively impact health or appearance of boxwood are commonly misdiagnosed and “treated” with inappropriate methods. This unnecessarily increases the chemical input and potential negative ecological impacts of landscape management and ignores key components of integrated pest management (IPM), e.g., scouting or monitoring and accurate diagnosis of plant health problems.” So, what can we learn from the research? My takeaways include the following:

Firstly, they confirmed the wide range of winter color change between species. In general, B. sempervirens and interspecific hybrid cultivars showed the most change compared to other species, but there were standout exceptions, perhaps with influence of hardiness zone. Until recently, our grounds straddled USDA hardiness zone 7b and 8a, although the new 2023 map places us solidly within 8a. Sites in colder zones have recorded different observations.

Secondly, there was no significant effect of supplemental fertilization on winter color change, supporting the warning that adding unnecessary inputs where the nutrient supply is already sufficient is not the solution. If the plants are deficient that is another matter, and should involve nutrient analysis.

Thirdly, shading alone dramatically reduced the degree of winter color change within affected cultivars, all else being equal on the exposed site where these plants were deliberately located.

Taken together, this research expands what we knew of winter bronzing and helps us all make better decisions on boxwood site placement at a species and cultivar level. For those who find orangetinted boxwood distasteful, informed selection and placement is the answer rather than reaching for the fertilizer bag.

If you would like to read the research paper and see the complete data tables, it is available open access (free to all) from the Journal of Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, Vol. 49, No. 5, Sept 2023, https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.2023.018

Summary by Dr. Matt Borden, plant pathologist and budding boxwood enthusiast at the Bartlett Tree Research Laboratory and Arboretum, Charlotte

2/21/2021 4/2/2021 5/11/2021

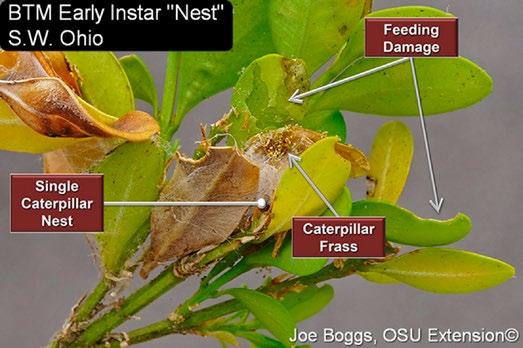

Box Tree Moth

by Didier Hermans

The box tree moth (Cydalima perspectalis, synonym Diaphania perspectalis) is a species of butterfly belonging to the Crambidae family. This species was first described by Francis Walker in 1859 and is native to East Asia. However, in Europe and the United States, this moth is considered an invasive exotic. In Europe, the box tree moth was first observed in 2006 at the border with Germany and Switzerland, while the first observations in the United States occurred in 2021 and 2022.

Description

The wings of the box tree moth have a wingspan of about 4 cm and are mainly white with a dark border, but there are also entirely brown varieties. They are mainly active at night but can also be observed during the day, especially when attracted to light. Adult moths live for an average of 8 days and females can lay up to five hundred eggs, usually on the underside and sometimes on the top of boxwood leaves. These eggs are laid in clusters of 10 to 20 and are difficult to detect.

The young caterpillars are dirty yellow in color and only a few millimeters in size, but quickly grow into bright green, darkly striped caterpillars with a black head, eventually reaching a size of about 4 cm. After the caterpillar stage, they pupate in leftover

cocoons for a period of about 14 days. In Western Europe, there are usually 2 generations per year and the caterpillars hibernate by cocooning themselves among boxwood leaves.

Spreading

The box tree moth is native to East Asia (Japan, South Korea, China) and was introduced to Europe in 2006 via packing wood of natural stone from Asia, as research by the University of Basel in Switzerland has shown. The spread of this invasive exotic species then rapidly accelerated to surrounding countries, causing the box tree moth to become a real pest throughout Western Europe within 10 years. In the United States, the box tree moth was first observed in 2021 and is on the rise.

Damage

Young caterpillars feed on parts of the mesophyll, usually on the underside of leaves, while adult caterpillars can completely defoliate a plant in a short period of time. On the infested plant, the veins of the eaten leaves and webs are left behind. Although it is sometimes suggested that caterpillars may also eat bark, this is rarely established. In response to the damage caused by the box tree moth, initial panic

arose among boxwood enthusiasts with boxwood, as a popular garden plant, being removed en masse from gardens as a result of a smear campaign through the media. Such actions are often labeled “FAKE NEWS” in the United States. Despite these reactions, boxwood is a hardy plant and even after complete defoliation can re-sprout in summer within about 8 weeks.

Treatment

Box tree moth caterpillars can be controlled either biologically or chemically. However, it is crucial to treat at the right time, when the caterpillars are still small and damage is minimal. Box tree moth produce two generations per year. A good approach to minimize damage is to treat two times per year when the caterpillars are young, with an additional treatment in the fall to prevent caterpillars in spring (as indicated in the diagram to the right).

Research shows that products based on spinosad, a substance allowed in organic farming in Europe, are as effective as chemical agents. Products based on the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis are also effective, albeit less so against older caterpillars. All chemical pesticides for caterpillars also appear to work fine without adversely affecting birds, contradicting previous claims that these pesticides are harmful to birds.

Other alternative control methods, such as sprinkling lava meal or lime meal on the leaves and using pheromone traps or pheromone disruption, have been found to be of little effectiveness from practical research conducted by the Ornamental Horticulture Research Center (PCS). The release of small parasitic wasps could possibly be effective, but this has not yet been proven in practice. Although natural enemies of the box tree moth such as birds, bats, and wasps can help suppress the pest in natural environments, treatment is still necessary in regular gardens because of the invasive nature of the caterpillar. However, some sort of natural balance seems to be developing, but appropriate intervention during certain periods remains necessary.

Conclusion

It is imperative that gardeners, nurserymen and consumers alike are well informed about the box tree moth. The media has played a negative role in Europe through smear campaigns, falsely calling for mass removal of boxwood. Correct information based on sound research is crucial. Treating the caterpillars is relatively simple but must be done at the right time; not treating is not an option with this invasive exotic. Biological solutions are preferred.

Didier Hermans is head of sales and research at Herplant, producer of BetterBuxus®

Box Tree Moth Strategies to “Slow the Spread”

by Patricia Reilly

Members know that the mission of The American Boxwood Society is to enhance the appreciation and scientific understanding of the genus Buxus L. It would be difficult to increase the popularity of boxwood without finding ways to meet the challenges of new pests and diseases to our favorite landscape plant. Sightings of Box Tree Moth (BTM), Cydalima perspectalis, have been confirmed in Canada, New York, Massachusetts, Michigan, Ohio, Delaware, and Pennsylvania. Damage from the caterpillar can be minimized when the pest is found early but is significant if not.

The natural spread of the adult form is three to six miles a year. Spread over longer distances is suspected to be due to infected plant material; the most efficacious strategy to slow the spread is through the nursery production pathway. With this in mind, efforts to slow the spread focus on quarantine, compliance agreements, and certifications.

A compliance agreement template was developed by the National Plant Board and the US Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Plant Protection and Quarantine. The template can be used by each state’s Plant Regulatory Officials for implementation in their own state. The compliance agreements can then be used to allow for the movement of boxwood out of quarantined areas.

Growers wishing to move boxwood out of quarantined areas must develop a pest management plan that is then approved by the State Certifying Authority. Records for each of the requirements must be maintained. Some of the requirements include:

• Training of staff to identify the pest in all of its life stages and other signs of its presence (frass, webbing, feeding)

• Trapping to alert that BTM is in the area (which must be reported)

• Routine scouting at frequencies based on BTM life stages

• Treatment when BTM is detected – once as part of production, once pre-shipment. Enclosed production areas may have exceptions

• Pre-shipment inspection

• Certification from the State Certifying Authority

• Notifying the receiving state

For details on the compliance agreements go to nationalplantboard.org, click the “Resources” tab to view the Box Tree Moth Compliance Agreement, or click the “Members” tab to view a list of the State Plant Regulatory Officials. To see which areas are under quarantine, use the Box Tree Moth Federal Quarantine Boundary Viewer at aphis.usda.gov (linked on the APHIS page on Box Tree Moth).

The nursery production pathway is not the only way the pest can spread. Garden center staff, landscapers, and homeowners must also participate in the effort to eliminate the spread. The American Boxwood Society encourages you to scout and report sightings of the pest or evidence of their presence. Reports can be made to local offices of the Cooperative Extension Service or to your State Plant Regulatory Official

Your help is needed to spread the word about the rapid damage that the BTM can inflict. ABS has informational rack cards for distribution to garden centers, garden clubs, Master Gardener volunteers, friends, or landscapers; send requests to amboxwoodsociety@gmail.com.

Boxwood: A Humble and Resilient Plant that Took Over the Garden World

by Anatole Tchikine, Dumbarton Oaks

“Boxwood blight invades North America,” read the heading of an article that appeared in Science News in January 2012. Caused by Cylindrocladium buxicola—a fungus whose spores remain viable for several years and are dispersed by birds, moving visitors, wind, and even sprinklers—the disease manifests itself by dark or light brown spots or lesions on the leaves that eventually fall off. First reported in southern England in 1994, boxwood blight has since been devastating gardens across the world, from Europe to New Zealand. Recently, it has been described as “a significant concern for the ornamental horticulture industry” as well as “a growing threat to established landscapes and native ecosystems alike.”1

Native to western and southern Europe, northwest Africa, and southwest Asia, boxwood is a genus of evergreen shrubs that enjoys great commercial success as an ornamental garden plant. Among its varieties and cultivars, the most popular is arguably English or common boxwood (Buxus sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’). In the United States—where this cultivar had been mass introduced on the wave of the early twentieth-century interest in European gardens—its sales, until recently, represented the greatest proportion (around 15%) among broadleaf evergreens, reaching an annual revenue of $126 million in 2014.2 A boxwood-flanked promenade, in the words of landscape architect Diane McGuire, was historically “the most common element found in

almost every garden in the southern United States.” One of the finest among these, Dumbarton Oaks— which was designed by Beatrix Farrand beginning in 1921—includes three areas originally named after the shrub: the Box Walk (image above), the Box Terrace, and the Box Ellipse (later replanted with hornbeam). According to McGuire, boxwood, along with yew and holly, was one of the most characteristic plants in Farrand’s palette, serving as “the embodiment of our deepest associations with the gardens of the Old World and with the cottage gardens of England.”3 It was precisely these historical roots of North American garden culture, not just the commercial future of a ubiquitous ornamental shrub, that the spread of boxwood blight threatened.

How did boxwood come to represent the lasting legacy of the European garden tradition? Its historical fortunes hardly amount to a dazzling story of overseas exploration, scientific discoveries, and economic exploitation—the “big business” of early modern botany, to use Daniela Bleichmar’s phrase.4 An integral element in the Mediterranean maquis (scrubland vegetation), boxwood has been familiar to Europeans for many centuries. Sixteenthcentury Italians considered it “a plant that is known to everybody, since it abundantly grows all over Italy”; while in England it was habitually found among “sundry waste and barren hills.”5

2. Topiary figure imitating ancient Roman examples from Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Venice, 1545, original edition 1499). Photo: Dumbarton Oaks

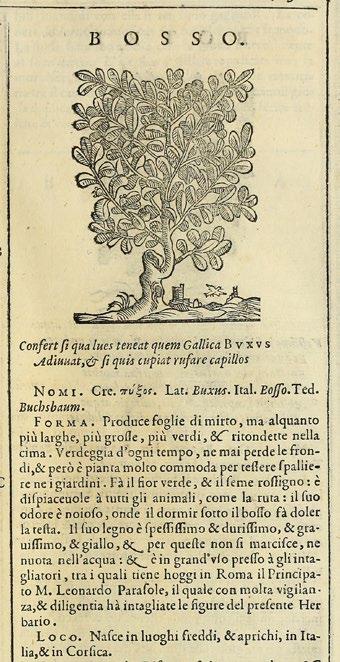

4.

Boxwood’s connections with garden design went back to antiquity. Writing at the turn of the second century CE, Roman author and politician Pliny the Younger mentioned the plant’s use in his villa “in Tuscis,” where, cut into various shapes representing figures and letters, it served as the main material for elaborate topiary work.6 This malleability of boxwood—the ease with which it lent itself to clipping and pruning—was particularly valued by the ancients, making it an indispensable and versatile medium for the creation of green architecture and sculpture (Figure 2).

Given this close association of boxwood with the gardens of Roman antiquity, it might come as a surprise that Italian Renaissance theorists disparaged its use, preferring instead other plants of similar size and texture, such as myrtle and viburnum (Viburnum tinus). Horticultural writer Girolamo Firenzuola, for example, recognized the ancient custom of using boxwood and laurel in making espaliers and hedges, noting, however, that these plants were less favored in his own day. Oranges, lemons, and citrons, he believed, were more “pleasing to the eye,” so that, in

creating a garden, one could dispense with boxwood altogether.7 A later sixteenth-century author, Giovan Vettorio Soderini, similarly acknowledged boxwood’s popularity in antiquity due to its “obedience to the clippers,” which allowed gardeners to “give it whatever form one might want” to produce “graceful animal and human figures, ships, vessels, towers, walls, fortifications, houses, obelisks, columns, tables, architraves, arches, pilasters, and seats.”8 Along with cypress, however, it could instill a melancholy mood, and, in winter, its roots could became infested with poisonous snakes.9

The real issue with boxwood was what sixteenthcentury English physician John Gerard described as its “evil and loathsome smell,” which, according to Soderini, was not only “annoying,” but could give one headache as it “infested the air.”10 To mitigate this odor, the preferred solution was to plant boxwood in combination with other strongly scented evergreens such as myrtle, mastic, and rosemary.11 These mixed hedges benefited from boxwood’s robust texture. The plant’s other selective use, which was also owed to its thick and dense foliage, was planting it in thicket-like

negative opinions continued to pervade early modern medical thought, since boxwood’s genuine curative properties, especially as a styptic, remained ignored.

While Mattioli and Parkinson considered boxwood primarily as an ornamental plant, “well adapted to weaving espaliers in gardens and dividing one space from another,” its slow growth rate had important industrial implications.16 Hardened through the process of gradual maturation, boxwood’s wood acquired such valued qualities as durability and density, making it indeed similar to guaiacum.17 Since it lent itself well to lathing, Gerard considered it particularly suitable for “dagger hafts, boxes, and suchlike uses.”18 Sixteenth-century Netherlandish rosary beads—true miracles of late Gothic craftsmanship—testify to these remarkable properties. These exquisite boxwood carvings, which often measure less than two inches in diameter, could represent multi-figure biblical scenes on a tiny scale without losing any of their dramatic intensity (Figure 5).

bird-trapping grounds (ragnaie).12 Yet, compared to other shrubs that could serve an analogous purpose or could occupy the same garden spaces, boxwood, in Soderini’s words, was “valued little or not at all.”13

Boxwood’s potential medicinal applications met with a similar lack of enthusiasm. Despite an attempt by Amato Lusitano, a sixteenth-century Portuguese Jewish physician, to prove that boxwood was a native European analogue of guaiacum and could, therefore, potentially cure syphilis, the general consensus, endorsed by the leading Italian authority on materia medica, Pietro Andrea Mattioli, was that it “had no use in medicine.” In Mattioli’s herbal (a compendium of early modern botanical knowledge), Lusitano’s claim was dismissed as “vain and foolish,” which “could in no way be acceptable to doctors.”14 Such pronouncements against boxwood, which was considered of “no physical use among the most and best physicians,” were also sustained by the Englishman John Parkinson; while his older contemporary Gerard raged against “foolish empirics and women leechers” who “minister it against apoplexy and such diseases” (Figure 3).15 These

Since boxwood, according to Soderini, could last “forever,” it was considered especially “good for the printing industry.”19 In his popular late sixteenthcentury herbal, papal physician Castore Durante described the shrub’s wood as “most dense and hard,” which made it “of great use to printmakers.” The woodblocks that served to illustrate Durante’s book were also carved of that material. They were executed by a leading specialist in Rome, Leonardo Parasole, whose contribution the author has graciously acknowledged in his entry on the plant beneath the accompanying image (Figure 4).20 The heyday of the use of boxwood in printing, however, came in the late eighteenth century with the invention of wood engraving by British printmaker Thomas Bewick, when the block was cut against rather than along the grain. This method ensured the texture of unprecedented toughness and durability, which enabled the enormous print run of Victorian periodicals illustrated by such outstanding artists as the Frenchman Gustave Doré (Figure 6).

The vindication of boxwood as an essential garden plant eventually took place in late sixteenth-century France instead of Italy. In French horticulture, this moment marked the introduction of parterres de broderie characterized by low, manicured hedges that imitated embroidery patterns (Figure 7).

Boxwood, along with myrtle, lavender, juniper, and rosemary, was deemed particularly well-adapted

to making the borders of plant beds, within which were planted marjoram, thyme, hyssop, pennyroyal, sage, chamomile, mint, violets, marguerites, basil, and other herbs and flowers.21 Horticultural theorist Olivier de Serres, in his Théâtre d’agriculture published in 1600, emphasized the shrub’s resistance to the effects of weather and time and its little need for care, favorably contrasting it with myrtle that was less suited to colder climes. These properties, as the French author believed, would have made boxwood a perfect garden shrub if not for its lack of “good scent,” as it had an odor “strong, unwelcome, and unpleasant, which causes headaches.”22

In practical terms, borders involving a combination of different shrubs as described by de Serres needed to be regularly replanted. If they were meant to last, the advice was to use boxwood alone regardless of its smell.23 An advocate of this method was the French royal gardener Claude Mollet, who was credited with inventing parterres de broderie and supplied their illustrations for de Serres’s treatise. Having

come from a family of gardeners, Mollet wrote from the perspective of a professional horticulturist. A committed champion of boxwood, he emphasized the volatility of the French climate affected by two “extremes”—“the great heat and the great cold”— that caused the “nuisance and expense of having to redo and replant garden compartments once every three years.”24 Mollet’s solution was to reduce the composition of borders solely to boxwood, which he started to implement for King Henri IV in 1595 in the gardens of Saint Germain en Laye, Monceaux, and Fontainebleau. Decades later, they still remained in “good shape.”25 The species that Mollet particularly praised was nain (dwarf) boxwood, which, although it did not grow as tall as other varieties and had smaller leaves, showed the same resistance to freezing and heat.26

Mollet’s planting and stylistic innovations gained their full expression in the gardens of Versailles that featured parterres, berceau (bowers), and a whole labyrinth of boxwood, created for Louis XIV by André Le Nôtre (Figure 8). From there they spread throughout Europe and beyond. Elaborate topiary work, for example, was one of the attractions of the European-style imperial garden of Yuanming Yuan (Old Summer Palace) in Beijing, designed in the eighteenth century by Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione and destroyed during the Opium Wars. By contrast, in Italy itself, gardeners continued to

was the lower terrace of the nearby fifteenthcentury Villa Medici in Fiesole that Pinsent furnished with a “carpet of box parterre,” regarded by landscape historian Geoffrey Jellicoe as fully integral to the historical character of the property (Figure 10).29 Popularized by postcards and book illustrations, Pinsent’s design became an iconic image of the Italian Renaissance garden, with its boxwood geometry, purposely projected into the Medicean age, serving as a visible bridge between distant antiquity and a more recent past.

resist the adoption of boxwood as the mainstream plant material. It took years before American novelist Edith Wharton—Beatrix Farrand’s aunt—could extol Italy’s “old garden-magic” that she identified with green “box-parterres” and “box-edged plots.”27 Even the once-reviled smell became a feature of Old-World nostalgia. In her autobiography, Wharton fondly recalled her friend Vernon Lee’s “homely box-scented garden,” an epitome of the quaint European charm consciously cultivated by members of the AngloAmerican community in Florence.28

Part of these expatriate circles was British landscape architect Cecil Pinsent, a contemporary of Farrand’s, who extensively used boxwood in his landscaping projects. Most famous among his gardens was the Villa I Tatti in Settignano near Florence, designed for the American art historian and connoisseur Bernard Berenson (Figure 9). Another celebrated work

Deeply invested with cultural symbolism, boxwood embodies the rich legacy of the formal gardens of Europe distinguished by geometric layouts, controlling vistas, and ambitious scale. Characterized by climate resistance and malleability, it has served not merely as plant material, but a key stylistic medium across the globe, representing a horticultural tradition that had its origins in antiquity. The story of boxwood is that of a humble yet resilient plant, which, after centuries of disparagement and neglect, took

10. Lower garden of the Villa Medici at Fiesole, Italy, re-designed by Cecil Pinsent beginning in 1911.

over the garden world. Whether or not it will retain this hard-earned preeminence as the most soughtafter ornamental shrub, only time can tell.30

The original version of this essay appeared in the Plant Humanities Lab, a digital platform developed by the Plant Humanities Initiative at Dumbarton Oaks in collaboration with JSTOR Labs: https://lab.plant-humanities.org/boxwood/

1 Nicholas LeBlanc, Catalina Salgado-Salazar, Jo Anne Crouch, “Boxwood Blight: An Ongoing Threat to Ornamental and Native Boxwood,” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 102 (2018): 4371. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-8936-2).

2 Ibid., with reference to USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service Census of Agriculture 2014 reports, https://www. agcensus.usda.gov. English or European boxwood is the same species (Buxus sempervirens) as American boxwood. There are no boxwood species native to the United States. The centers of diversity for the genus are in Western Europe, Northern Africa, and Asia (Buxus microphylla).

3 Diane Kostial McGuire, ed., Beatrix Farrand’s Plant Book for Dumbarton Oaks (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1980), xiii.

4 Daniela Bleichmar, “Botanical Conquistadors: The Promises and Challenges of Imperial Botany in the Hispanic Enlightenment,” in The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth century, ed. Yota Batsaki, Sarah Burke Cahalan, and Anatole Tchikine (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 2016), 35.

5 Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Discorsi (Venice: Valgrisi, 1563), 138; John Gerard, Herball (London: Norton, 1595), 1225.

6 Pliny the Younger, Letters, V.6.

7 Girolamo Firenzuola, “La grande arte della agricoltura,” in Alessandro Tagliolini, “Girolamo Firenzuola e il giardino nelle fonti della metà del Cinquecento,” in Il giardino storico italiano, ed. Giovanna Ragionieri (Florence: Olschki, 1981), 304.

8 Giovan Vettorio Soderini, Opere, ed. Alberto Bacchi della Lega (Bologna: Romagnoli dall’Acqua, 1902–07), III: 52, 245, 251, 343, 254.

9 Firenzuola, “La grande arte della agricoltura,” 304; Soderini, Opere, III:254.

10 Gerard, Herball, 1226; Soderini, Opere, III:343.

11 Soderini, Opere, III: 254, 255; Firenzuola, “La grande arte della agricoltura,” 304. Cf. Claudia Lazzaro, The Italian Renaissance Garden: From the Conventions of Planting, Design, and Ornament to the Grand Gardens of Sixteenth-Century Italy (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1990), 26, 291–292n.17.

12 Soderini, Opere, III: 295, 303, 343; Bernardo Davanzati, Toscana coltivazione delle viti e delli arbori (Florence: Giunti, 1622), 32.

13 Soderini, Opere, III: 255.

14 Mattioli, Discorsi, 138; John Parkinson, Paradisi in sole paradisus terrestris (London: Lownes and Young, 1629), 606, reporting the same opinion; cf. Amato Lusitano, Curationem medicinaliam centuriae septem (Bordeaux: Vernot, 1620), 639–40.

15 Parkinson, 606; Gerard, Herball, 1225.

16 Mattioli, Discorsi, 138; cf. Parkinson, Paradisi in sole, 606–07.

17 Soderini, Opere, I: 182.

18 Gerard, Herball, 1225.

19 Soderini, Opere, I: 151, 175.

20 Castore Durante, Herbario nuovo (Rome: Bonfadino and Diani, 1585), 75.

21 Olivier de Serres, Théatre d’agriculture (Paris: Saugrain, 1617), 506, 529; Jacques Boyceau, Traite du jardinage (Paris: Vanlochom, 1638), 66.

22 De Serres, Théatre d’agriculture, 506, 529.

23 De Serres, Théatre d’agriculture, 529.

24 Claude Mollet, Théatre des jardinage (Paris: De Sercy, 1663), 201–02.

25 Mollet, Théatre des jardinage, 202–03.

26 Mollet, Théatre des jardinage, 203.

27 Edith Wharton, Italian Villas and their Gardens (New York: The Century Co., 1904), 13 and passim.

28 Edith Wharton, A Backward Glance (New York, London: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1934), 130.

29 Geoffrey Jellicoe, “Italian Renaissance Gardens,” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 101 (1953): 182. (http://www.jstor.org/ stable/41365015)

30 Both American and English boxwood are highly susceptible to boxwood blight, the latter perhaps owing to its compact, dense habit, which restricts air movement thereby allowing foliage to remain wet for longer periods and trapping detritus in the interior of the plant. The cultivars of Buxus microphylla and Buxus harlandii, both native to Asia, show higher levels of resistance to the disease. I am grateful to Jonathan Kavalier, Director of Dumbarton Oaks Gardens, for this information.

Betterbuxus ® in European Historical Gardens

by Didier Hermans, Betterbuxus

For centuries, boxwood has graced historic gardens as a decorative trim and delicate embroidery. In famous castle gardens around the world, thousands of these plants have been used to form graceful patterns. The garden architect Le Nôtre and his contemporaries in particular brought this garden aesthetic to fruition. Countless renaissance and baroque gardens were laid out throughout Europe, mainly intended for the wealthy nobility.

Thanks to careful and regular pruning, often to a height of only 20 cm, Buxus sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’ was used for a long time. Because of its slower growth, pruning was less intensive and one pruning a year was sufficient. The native Buxus sempervirens, common in Europe, was also widely used and usually required two pruning sessions a year for tighter forms. This went well for decades, until a new fungal disease made its appearance in the boxwood world in the 1990s. Buxus sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’ proved particularly susceptible and even the common Buxus sempervirens was severely affected.

Although many plants could still be saved with frequent fungicide applications in that era, it was a losing battle for many. This led to a search for alternative plants. Although numerous options were reviewed, in practice none proved capable

of replacing Buxus.

With our Betterbuxus®, resulting from in-depth breeding research, we now offer a sustainable answer to the Buxus fungus issue. These plants do not require fungicide treatment, making them an excellent solution for mostly public historic gardens, where strict regulations apply to the use of plant protection products, or even where they are not allowed.

Four different hybrids were developed, each with its specific characteristics:

Betterbuxus® Renaissance for low hedges

Betterbuxus® Babylon Beauty for low hedges and ground cover

Betterbuxus® Heritage for general use

Betterbuxus® Skylight for higher hedges, bulbs and cloud planting

More info on these hybrids can be found at betterbuxus.com

Although even our new hybrids still require some control to manage the boxwood moth, they are generally somewhat more tolerant. Using biological methods, this control can be done effectively with minimal impact on the environment.

In early 2020, at the start of the COVID period, the first Betterbuxus® plants were planted at Chateau de Villandry (France) and Palace Het Loo (Netherlands); these two gardens are our first ambassadors.

Numerous other castle gardens followed a year later. The beginning of June saw the start of the complete replacement of the embroidery in Versailles with Betterbuxus® Renaissance. With a small halt during the Olympics, they are now completing it. By the

end of 2024, more than 60 castle gardens in nine countries will have been planted with Betterbuxus® and visitors will once again be able to enjoy these beautiful baroque gardens.

In the United States, Betterbuxus® is distributed under the Betterboxwood® brand name by Everde growers/PDSI. More information can be found at betterboxwood.com

Update on the ABS Boxwood Memorial Garden

by Jared Manzo, The State Arboretum of Virginia

ABS’s Boxwood Memorial Garden at The State Arboretum of Virginia (Blandy Experimental Farm) moves through mid-autumn with spirit and verdancy. The yellowwoods, blackgums, and sourwoods flash their fall colors against an evergreen canvas of boxwood. Much of this year was spent restoring the rear part of the garden made up mostly of microphyllas and much older sempervirens from the early 1960s. Some layered branches on the ‘Anderson’ and ‘Salicifolia’ looked like individual specimens which were obscuring the layout of the garden. Addressing this scenario in a number of spots has reclaimed avenues through this particular section of the garden while also revealing plants unrecognizable in form. The heavy restoration pruning is almost completed which should allow more time for general maintenance pruning moving forward.

The garden as a whole is doing well, but not without some losses. After two growing seasons of drought, a ‘Harlandii’ appeared to dry up. We also removed our ‘Miss Jones’ and ‘Pincushion’ specimens. Finally, we cut to the ground or completely removed our ‘Morris Midget’ hedges that were failing to thrive in a few areas of the garden. As protection from boxwood blight, we have elevated most of the skirts on the specimens and apply fungicide when appropriate. This year, we hung monitoring traps for boxwood tree moth too. Despite the challenges, we are still taking cuttings for propagation and planting into the open areas of the garden. We added Buxus microphylla var. japonica ‘Unraveled’ to the garden this fall.

A stone’s throw away is our corridor of Korean boxwood ‘nanas’ in decline. It was only six years ago that these plants from the 1930s were a sight to behold. In 2024, almost all the plants were offcolor and giving up whole branches with significant breaks in the continuous hedge due to plant removal. Two important stressors were identified: a high population of nematodes and the grade being elevated up to four inches due to the walkway restoration work over a decade ago. We are in the early discussions on what will line this important thoroughfare in the future. In the meantime, we’ll enjoy the autumn scenes and see what we can get done this winter in the garden.

Jared Manzo has worked on the grounds of Blandy since 2018 and has served as the Arborist since 2023. He has a Bachelor degree in Forest Resource Management and a Masters degree in Forestry from West Virginia University.

Boxwood Memorial Garden - Maintenance

Entrance to Boxwood Memorial Garden showing dieback on ‘Morris Midget’ boxwood before they were cut back to the ground this fall. We hope they will once again develop into a sufficient planting to complement the entrance.

So far, none have been replanted, but the

are healthy.

Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens

by Cheryl Crowell

One of the joys of belonging to The American Boxwood Society is being given the opportunity to tour beautiful gardens. This year I was able to travel with some Garden Club friends on a day trip to a particularly remarkable home and garden!

Hillwood Estate was the home of Marjorie Merriweather Post (1887–1973), her spring and fall residence. It is interesting to note that her winter home in Palm Beach, Florida, was Mar-a-Lago, the current residence of the newly-elected President of the United States, Donald Trump and his wife Melania. Post’s home in Washington, D.C. is situated on 25 acres, 13 of which are gardens. We learned that Mrs. Post designed the view from the back of the house to frame the Washington Monument, which we were able to see over the tops of tall trees.

First we toured the mansion, a remarkable and elegant home purchased in 1955 and designed to house the fabulous collections procured over Mrs. Post’s lifetime. Marjorie Post was the heir to the Postum Cereal Company, later General Foods, and was one of the wealthiest women of her time. She became owner of the company at age 27 after the death of her father. She was fully involved in the conduct of business affairs of her company, one of only a few women at the time to hold corporate power.

Though involved in business, she made significant philanthropic contributions throughout her life while her personal interests became focused on a collection of French and Russian art. She is

American soldiers and veterans from World War II to Vietnam, and one in Washington D.C. supported the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, the National Symphony Orchestra, and the Kennedy Center.

Post accompanied her third husband, Joseph Davies when he was named Ambassador to the Soviet Union (1937 to 1938). While there, she discovered fine decorative arts of imperial Russia in commission shops and state-run storerooms being sold at a fraction of their value. She purchased a significant number of important items including Fabergé eggs which are now displayed elegantly within the mansion. When Hillwood Estate opened to the public in 1977 it showcased the most comprehensive collection of Russian imperial art outside of Russia and a distinguished collection of French art from the 1900s.

Another of Post’s legacies at Hillwood includes the twenty-five acres of gardens and landscaping that surround the mansion. They beautifully display her interest in flowers and landscaping, all designed to be comfortable and interesting for her many guests. We passed from the house to the French Parterre Garden, to a sight that would have been very popular in the France of the 1700s. We too enjoyed the intricate patterns and beautiful maintenance of the clipped boxwood parterre before we continued to the Rose Garden.

Marjorie Merriweather Post loved flowers, and roses were a favorite of hers. Each bed in the rose garden is planted with a single variety of summer blooming floribunda rose. The site houses her ashes in a granite monument centered among the roses. It was indeed a serene and joyous place filled with lovinglymaintained blooming roses.

Next, we traveled down the Friendship Walk lined with rhododendrons, azaleas and boxwood. We were told that the boxwood were recently-planted NewGen Independence® because the previous boxwood planting had succumbed to boxwood blight. They fit right into the lovely green corridor that led to the putting green. Golf was a favorite exercise and was enjoyed as a healthy lifestyle by both family and friends. This carefully-trimmed lawn surely saw a lot of use!

Arriving at the back of the house on the Lunar Lawn, we learned that this lovely open space hosted many receptions and garden parties for the pleasure of politicians, philanthropic organizations, and personal enjoyment. The lawn was edged with mature trees, shrubs and flowers creating a delightful backdrop for the home.

We next visited the Japanese-style garden, situated on a hillside that allowed the flow of water to be the star attraction in an area planted with both Japanese and American plants. The area was styled to feel like a rustic but curated space. Japanese art and ornaments complemented the beautiful and peaceful setting.

Our tour ended at the cutting garden filled with flowers of all shapes and colors. Marjorie Merriweather Post used to fill her home with cut stems that complemented each room’s style and color. The tradition continues today, with beautiful bouquets throughout the house. My favorite, though, was the single fresh flower, often an orchid, placed by staff below her portrait, a kind sentiment of love for a beautiful and generous lady.

Roots: A Growerʼs Perspective

by Kevin Collard

As a specialized boxwood grower, I’m often asked about nursery production – specifically, roots. Perhaps a strange request as the above ground portions (of most plants) holds the perceived beauty. The astute questioner knows the magic happens below ground.

Well, not Harry Potter magic, but events which we may not fully understand or appreciate. To talk about roots, we need to begin with soil – the place most roots call “home”. To discuss soil, we need to go down the hole, the proverbial rabbit hole . . .

Soil, commonly referred to as “dirt”, is a complex mixture of aggregates. It includes sand, silt, clay, organic matter, minerals, nutrients, gases, liquids, and most importantly LIFE (aka living organisms)! Our dear friend ‘T’ Fleisher (a national leader in sustainable horticulture and a current American Boxwood Society Director) has written articles and given presentations on this very subject. One could write a book about such things; indeed, many have. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (previously, and famously, known as the Soil Conservation Service) remains the most prolific, and respected, resource for understanding all soils. Yet, many questions remain unanswered. So, lets focus on roots. Why roots? Well, without roots there are no plant shoots and this is what we all long for!

This topic became clear to me when my boxwood hero, Paul Saunders, came to visit me and my nursery for the first time. Paul (1933–2022) was the second generation which established the renowned Saunders Brothers Nursery in Piney River, Virginia, beginning boxwood production in 1947. Today, with 175+ acres of boxwood, offering more than 25 Buxus taxa, it is perhaps the largest and most respected boxwood nursery in North America. Imagine, Paul came to see me! At the time I was enthusiastically collecting all the different boxwood species and cultivars as I could get my hands on. At the time, for about 10 years, I was nearly obsessed with my

singular goal of furious collecting. In retrospect, perhaps it got a little out of hand.

When Paul arrived at my nursery, I was so excited to show him everything that I had been doing. Looking back, I still can’t believe Paul actually visited. Paul and his wife, Tatum, were traveling to Nashville, Tennessee, to attend antique shows. Paul had previously loaned me his little trailer which I had used to take some plants home after visiting his Virginia nursery. This arrangement benefited both of us. I obtained more plants from Paul and he could retrieve his trailer and visit my nursery. Can you believe it?

So, this happened… Then Paul and Tatum visited… And we talked…

I gave him a tour of my nursery and vast collection of boxwood with nearly 100 different cultivars. I showed and explained to Paul how I grew and propagated, at my level of production. This included how I grew and marketed my plants to both my customers and clients. But the one thing that confused Paul was when I removed the container from different plants and held the root ball in my hands. I wanted to show him THE ROOTS!

I didn’t think much of it at the time. Looking back, my first job was at a greenhouse operation while attending college. I was working for my mentor, Roger Caudill, in the nearby town of Franklin, Kentucky. Daily, Roger would take plants out of their container, always checking the progress and health of their roots. In fact, he wouldn’t sell any plant until it was fully rooted out and met his approval. This would frustrate customers who wanted to buy a particular plant. Roger would determine the plants weren’t ready and would refuse to sell them. He had the highest standards of any grower whom I have ever worked with.

When a seed is planted, the first thing that germinates is the root. Then, as growth continues the shoot emerges from the seed capsule. So, without the root, there is no shoot. Said differently, the roots are the foundation of life for the plant.

Getting to the root of the topic (all puns intended), I am not a scientist. However, I am a successful grower with keen skills of observation regarding many things. These “things” may be different, which could be either good or bad. A mutation, an unusual stem, a pest, or early signs of disease. When these things are

normal, I also am normal. However, when things are different, or out of place, I am immediately triggered.

This applies to roots. Through decades of personal and professional observation, I have perceived the various root structures of different cultivars and species of some boxwood.

Again, I am not a scientist nor researcher. I am a grower with 31 years of professional experience and a degree in horticulture. I dislike writing and prefer conversation. So, starting with the boxwood which I observed to have the worst root performance and working my way to the best, let's begin.

The worst preforming boxwood include almost all of the B. sempervirens cultivars.

The worst of these is ‘Graham Blandy’. What an amazing habit and such a unique position to be at the bottom of the list. But no! The root system is quite possibly the weakest among all boxwood. Yet, most gardeners know and want this plant. But Paul Saunders no longer offers this cultivar and neither do I! To explain, if I propagated 100 ‘Graham Blandy’ cuttings, I would be fortunate if ten plants grew to a 3-gallon container. It must have nearly perfect drainage, or it is DEAD. I would have included images of the roots, but they’re all dead!