Space-Time or Body-Mind: Place, Time and Being in The

Contemplative Space of Japanese Architecture

Architecture In Context 3

Wordcount: 5500

Architecture In Context 3

Wordcount: 5500

Spatial experience

Temporal experience

Being Bodily Engagement

Body-Mind Unity

Psychosomatic Experience – the experience relating to the interaction of mind and body

Ma - Emptiness

Shintai - Spirit

Yugen – Obscurity

Wabi-Sabi – Simplicity

Hikari to Kage – Light and Shadow

Design Philosophy

Tea House

Tea Ceremony

“When a Human Being puts himself into a small, enclosed space, his thoughts lead towards infinity. In his deepest of his meditations, he can hear the voice of nature and reach the cosmos ”

- Tadao Ando. In Frederic Levrat: Addition by Subtraction (1994), p.4

It is widely believed that traditional Japanese architecture differs fundamentally from those of the west in their reception to time. (Nute, 2021, p.4). From the prolonged journey to the Japanese room, to the restriction of the muted grey light, the Japanese room accommodates for an experiential manipulation of time and space These modifications of our sensory experience in turn, provokes a bodily engagement of the space, and thus, also the sensorial experience of being present in the world, or in other words ‘alive’ In a world where scientific knowledge is valued, technology relied upon, and materialism our essence, it is not surprising why the Japanese architecture of simplicity – inherently based on Japanese philosophy - has gained increased popularity in the western world (Levrat, 1994, p.1). Heidegger called it a “darkening of the world”, where the Being has lost its sense of meaning and intention – or in Nietzche’s words, “a haze” - that has been replaced with the desires of the details of the material world (Lobell, 1979, p.64) The sensory perception of space and time are therefore critical in our understanding of the world and our being, as it is through these conceptions, we attain a ‘sense of place’. (Veal, 2002, p.1)

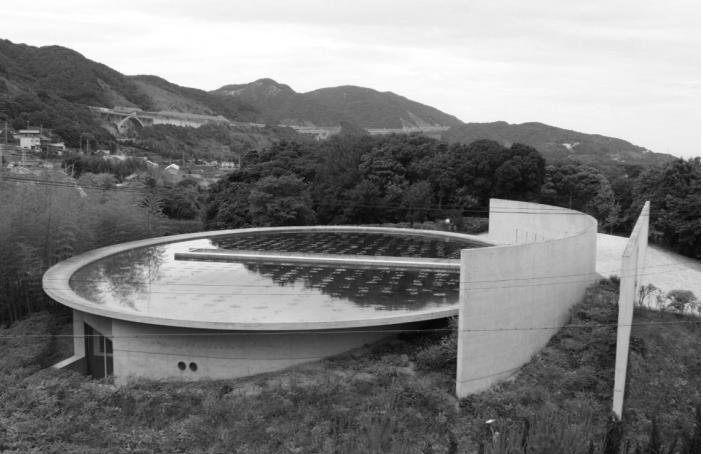

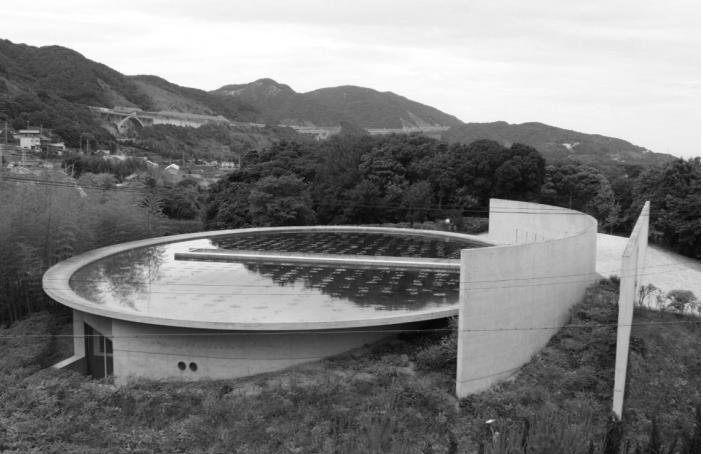

The study aims to explore the relationship between time, space and being in Japanese architecture and its effect on our sensory experience through the space. It will begin with a definition of ‘Time’ , ‘Space’ and ‘Being through bodily engagement’ , outlining the difference in thought that separates Eastern philosophy from the West. The study will then explore Japanese philosophy and its implication in Japanese architecture, looking at traditional Japanese teahouses and Tadao Ando’s Water Temple as case studies, and their implementation of bodily engagement in space and time. The tea house can be seen as the epitome of the Japanese philosophy of body-mind unity (Ko, 2006 p.2), whereas the Water Temple, like many of Ando’s architectural works, utilises the same principle of body-mind design in his sensitivity for

temporal and spatial experience (Veal, 2002, p.7). The case studies thus not only serve as practical examples of the effect of temporal and experiential design but are also intended to add to the existing research on bodily engagement of space, and how these strategies can be implemented in my future projects.

Ultimately, this study seeks to realise the relationship between the human being and his environment through the relationship between body and mind. I believe that, to experience the world, we must feel our presence in the world. To be present in the world, is to sense the world.

The study will be founded on literature from writers within the psychological, philosophical, and architectural profession, with analysis of experiential responses drawn upon existing studies alongside my own. As neither of the case studies are within my reach of a physical visit, the analysis will be based on photographs primarily, and empirically, on the description of the sensorial experience of selected writers. Although the user experience is far from equivalent to that of visiting the building in person, (as the user experience is that of a subjective matter), I will base my judgement on the materials above. Similarly, due to the limitations in language, the majority of the sources will, admittedly, come from western authors or translated by such.

That being said, and effort will also be made to explore other contemporary Japanese architects influenced by the Zen philosophy, that adhere too, to temporal and experiential design

“A good western speaker speaks loudly and clearly. A well-educated Japanese speaks in a low voice. […] The Japanese loves the unspoken, he is content with giving subtle hints [..] for the Japanese it is very often the essential thing which is not said or written, and he hesitates to say what can be imagined or should be imagined.” - Schinzer “Intelligibity and Nothingness, (1958), p.3

The essence of Japanese philosophy lays in the view of the human being and the world. The self and the environment, as well as the mind and the body, are not only seen as two entities living in harmonic coexistence but are in fact one, existing in unison of opposite qualities (Ko, 2006 p.1-2). This idea is directly linked to Taoism and zen Buddhism, in the idea that everything ends in ultimate Nothingness – where the true reality of all things lies, and that the opposition of qualities, such as day and night, outside and inside, or the performing and the contemplative, are in fact sides of one entity. The balance of each opposite is what creates harmony in the universe, and what creates balance in life. (Trisno and Lianto, 2021, p.2)

To understand the concept of ‘being’ in Japanese philosophy, we must first understand its constitution. Japanese philosophy can be said to rest on three pillars: the Confucian moral order of society, the way of living in Taoism, and the essence of Zen Buddhism. Confucianism shaped the outward forms of social behaviour and the inward value of character of the Japanese (Trisno and Lianto, 2021, p 22), whereas Taoism appears in its teachings of ‘the Way’ , on how to live a good life in harmony with the world, and in being present. Its emphasis thus lies heavily on effortless action and stillness of the mind, with the explanation that, to the mind that is still – like the usefulness of a pot - comes from its emptiness. (Tsu with transl. by Mcdonald, verse 11, 1996 p.5) Kakuzo Okakura further explains:

“The Tao is the spirit of cosmic change – the eternal growth with returns upon itself to produce new forms. […] The Tao might be spoken of as the great transition. Subjectively it is the Mood of the Universe. Its absolute is the Relative.” – (Okakura, 1906, p.17-18). Thus, one could conclude, Taoism is about the rhythms of life and the universe

Similar to Taoism, Zen Buddhism’s prevailing idea is that the Buddha nature, in which true essence of all entities lies, can be found in all things (p.23, Schinzer, 1958, p.23) To become Buddha is to reach salvation (‘satori’) in which, as it already exists within one ’s heart, can be reached by introspection into one’s own essence. Hence, Zen stresses the importance of the intuition and living in harmony, with the goal that, to live a full life of peace and salvation, one must practice it. Such a way is through meditation. By breaking down the intellect one is able

to reach intuition, and ultimately, re-discover one ’s true nature, as it is not the reasoning but the senses that enable intuition. (Schinzer, 1958, p.28-32) Consequently, the Japanese mind on being present in the moment, and on simplicity and stillness, can be derived from Zen.

Built upon the above outline of Japanese philosophy, its view on being and bodily engagement places importance on the body shaping our perception of the world. One should note however, that this is not unique for Japanese philosophy; Christian Norberg-Schulz advocates strongly for experiential space in architecture, stating that architectural space “form a necessary part of man’s general orientation of ‘being in the world’” (Norberg-Schulz, 1974, p.7). Our experience of place is directly linked to our physical body, but place is also in turn, affected by our body Nonetheless, what separates the East Asian philosophy from the west is its perception of the environment, where space in the West tends to be seen as object-matter (Norberg-Schulz, 1963, p.28) East Asian thought lays importance on the interconnectedness of all things, and thus, the relationship between all objects as parts of a larger hole (Davies, Ikeno, 2002, p.195). Similarly, the significancy of harmony and balance in the East can be compared to the western rationality of function and form, which is particularly evident in modern western design practice (Ko, 2006, p.7-11).

Bodily engagement refers to the idea of being fully aware of the sensory experiences felt through the body, the integration between the intellectual mind and the sensual body, and between the human being and his environment. (Ko, 2006, p.11) It involves spatial and temporal awareness as we move, the roughness of the rocks sensed by our touch, or the sounds of trees in the Japanese garden. The phrase “understanding through the body” leads us to actively engage with our environment, which in turn, evokes an acute feeling of being alive (Ko, 2006, p.11). Furthermore, through multi-sensory experience and bodily engagement, a positive tangible effect on our well-being can be sensed, physically as well as psychologically

(Saito, 2012, p.223) For example, the Japanese profound respect for nature (embedded in Shintai = the spirit of nature) have led to the development of gardens to evoke a sense of serenity, with the purpose of calming the mind and direct the focus inwards, towards the moment and the presence, felt through the sensations of the body from the place. The garden is thus seen both as a medium for mental and spiritual stillness, but also as an embodiment of the harmony and balance of the universe in its careful relationships between “voice-silence” , “perception awareness-perception blankness” , and “void-fill” (linmura, 1993, pp.34-39) In a similar manner, the design of the Japanese tea house is said to evoke a “psychosomatic experience” as it stimulates “the natural self-regulatory systems of the body (Ikemi and Ishikawa, 1979 pp.1-4) Through its structure, materiality and aesthetic expression, architectural space has therefore the opportunity to adhere to the psychological, emotional, spiritual, and transformative experience of the human being and his place in the world. Ando describes it as such:

“The body articulates the world. At the same time, the body is articulated by the world. When "I" perceive the concrete to be something cold and hard, I " recognize the body as something warm and soft. In this way the body in its dynamic relationship with the world becomes the shintai. It is only the shintai in this sense that builds or understands architecture. The shintai is a sentient being that responds to the world. When one stands on a site which is still empty, one can sometimes hear the land voice a need for a building. The old anthropomorphic idea of the genius loci was a recognition of this phenomenon. What this voice is saying is actually "understandable" only to the shintai. (By understandable I obviously do not mean comprehensible only through reasoning). Architecture must also be understood through the senses of the shintai.” – Tadao Ando, (Framton, 1991, p.24)

Hence, by developing an understanding of the underlying principles and specific mechanisms of the human experience, body-mind design strategies can be carefully implemented towards a state of “existential well-being” (Ko, 2006, p.11), similar to that which can be found in Japanese Architecture.

2.2: The impermanence of life – such as that of the Japanese Cherry tree leaves, (Shinners, 2016)

“The Japanese have understood space as an element formed by the interaction of facets of time.” - Isozaki “Ma, Space-Time in Japan”, (1979), p.16-17

Similar to the concept of ‘being’ , one can note clear differences between West and Eastern thought in their conceptions of time and space Fundamentally, their differences lay in the perception of time, where the Japanese view time as a cyclical process of infinitude, whereas the West tend to see time as linear and sequential, or in order words, scientifically as measurable (p.17, Hawking, 1996, Ma, 2003, Cairns, McInnes & Roberts, 2003). In Eastern views time is relative, as it is a matter of perception in relation to space and mind. To illustrate this, we can use an old Zen anecdote:

“Two men were arguing about a waving flag. The first man said, “It is the wind that is really moving, not the flag,” The second man said, “No, it is the flag that is moving, not the wind.” A zen master, who happened to be walking by, said: “Neither the flag nor the wind is moving. It is your mind that moves ” – Okakura, 1906, p.22)

Time, hence, cannot be known, and acts in conjunction with space and body Despite its mystical connotations however, time is highly valued in the Japanese mind, as it is viewed, paradoxically, as something transient, fleeting, and therefore precious. (Veal, p.1,2002) The joy from momentary events, such as observing the changing seasons in the fall of the cherry blossom, or the joy felt from a cup of tea, calls for the acceptance of the transience of things, and the importance of living in the moment (Lee, 2016 p.94) As things, like time, are in constant change, nothing in the world is permanent. Thus, Japanese thought places profound importance on being present in time, which, ironically, results in a perceived temporal extension of the moment. (Okakura, (1906, p.20, and Wittmann, 2019, p.42-43). A familiar experience of such would be that of a boring task: due to the perceived nature of the task, our increased attention to our sensory perception results in the feeling of the time ‘going slow” (Saito, 2008, p.226-227)

The awareness for temporal perception is also be observed in the Japanese architecture. In Time in the Tradition in The Japanese Room Nute asserts that the traditional Japanese buildings differ significantly from the West in its reception of time. (Nute, p.4). the Japanese

room holds temporal qualities to prolong the sense of time, which can not only be seen in its interior, but also in its exterior and in the Japanese garden. Saito illustrates this with an example: “bridges [in Japanese gardens] are often made with two planks of slates placed in a staggered manner so that we are made to pause in the middle and turn slightly before continuing our crossing. These spatial configurations manipulate our experience as it unfolds time, making it more sensuously stimulating than if we were to walk straight without pausing and turning.” –Saito, 2008, p.228

Equally, temporal experience inside space can be broken down into smaller sections of order and anticipation, by breaking up the user’s movements (Nitschke, 2018).

With regard to the Japanese concept of space, the meaning can be found in the term ‘ ma ’ Although it is difficult to determine the full meaning of ma (due to its many applications and contextual meanings ) it is most commonly translated to ‘emptiness’ , or ‘void’ , but can also be used according to Nitschke, as a term for ‘ space ’ or ‘ room ’ (Nitschke, 2018) However, Nute argues that the Japanese themselves understood the term ‘ ma ’ as ‘void’ when it was first introduced from China, claims that seems to be strengthened by Kakuzo Okakura. In The Book of Tea, Okakura’s commentaries that “the reality of a room, lays in the vacant space enclosed” (Okakura, 1906, p.24) and that “the non-existence of space to the truly enlightened” (p.34) imply that ‘ ma ’ can be, in the broadest sense referred to as ‘void’ . At the same time, these statements also indicate a deeper meaning of ‘ ma ’ of possessing temporal and spiritual qualities, which later is confirmed by Susumi Ono in Japan-ness in Architecture:

“[Ma as] the space in between things that exists next to each other an interstice between things- chasm in a temporal context, the time of rest or pause in phenomenon occurring one after another ” – Susumi Ono, (Ono, 1990, quoted in Arata Izosaki, (2006, p.94-95)

Nitchke further describes it as experiential place closer in meaning to mysterious atmosphere (1996, p.117), which in turn, suggest ‘ ma ’ to be an indescribable feeling of time, space and essence that can only be sensed through sensory experience.

Taken together, most aspects of Japanese architecture can be traced back to the concept of ‘ ma ’ in its qualities of simplicity, bridging spaces, openings and obscurity (Snodgrass, 2006, p.138) This is particularly evident in the use of Soji screens of traditional Japanese houses (p.48), the spatial expansion of the tea house (Hashimoto, 1981, p.45), as well as in the use of void in the Zen garden (Kim, 2013, p.52). Thus, ‘ ma ’ can be said to represent the sensed divinity of infinite expansion of space.

“Length of time depends upon ideas. Size of space hangs upon our sentiments. For one whose mind is free from care, A day will outlast the millennium For those whose heart is large, A tiny room is as the space between heaven and earth ” - Yuhodo, “Saikontan”, (1926) transl. by Nitschke, Kyoto Journal, 2018)

The Japanese Tea ceremony (‘chado’) is a vital aspect of the Japanese tradition. It is the embodied ideal of Japanese philosophy, in the attitude of being, time and space. So far, the ontological view of Japanese thought has been widely explored in this paper, with comparisons and examples to further illustrate the ideas. Yet, to understand how these ideas is applied in practice, one must first understand the meaning of tea house and tea ceremony.

In The Book of Tea, Kakuzo Okakura describes the tea house as small and unimpressive in appearance, a “straw hut” , as it “does not pretend to be other than a mere cottage” (Okakura, 1906, p.24). Yet, it is in the tea house the body-mind design philosophy becomes most prominent; in its subtraction of components, poetic use of void, and deliberate imperfection (Ko, 2006, p.1) Ko further suggest that the deliberate use of vernacular elements – similar to that of a “peasant house” – bestows “pleasure in abstinence, richness in poverty and sensibility in simplicity” (p.2). These methods thus pose the Japanese zen philosophy to be that of “ a holistic experience” that integrates with the design, in which the tea ceremony is part of (p.4) In other words, the Zen philosophy of simplicity and imperfection (‘wabi sabi’) is manifested in the tea house in both a physical and a spiritual sense: by leaving something unfinished, the body employs the mind for the imagination to complete, as, according to Okakura, “true beauty” can only be revealed “by one who mentally completed the incomplete“ (Okakura, 1906, p.30).

In a comparable manner, it is false to regard the tea ceremony as simply a methodological experience. When tea master Sen-no-Rikyu (1521-91) was asked about the essence of the tea ceremony he replied:

“Tea is nought but this.

First you make the water boil,

Then infuse the tea.

Then you drink it properly.

This is all you need to know.”

- Sadler, (1962, p.102)

From this, it can be inferred that the meaning of tea lays in the inexplicable and not in the literal ritual, that can only be known by the sensual experience of practise. Upon reflection of its impact, Daisetz T. Suzuki narrates:

“The tea drinking [ ] is not just drinking tea, but it is the art of cultivating what might be called psychospere or the psychic atmosphere, or the inner field of consciousness - Suzuki, (1959, p.295296)

This expands upon the previous point that the tea ceremony is not only a sensuous experience, but also a spiritual experience that connecting the body with the mind, achieved with intensive attention to the execution of a simple task of making and drinking tea. The role of the tea house is thus to stage the scene for this execution, by isolating the participants from any distractions from the outside world and to draw the attention to the tea ceremony – so that the tea house become a separate realm where time is still This interpretation shows evidence in both The Book of Tea and in The Japanese tea ceremony: Cha-no-Yu in their reference to the tea room as a place where one “forgets the existence of time (Okakura, 1906, p.46), to, “create within oneself a new consciousness of peace and beauty” (Sadler, 1962, p.13)

In recent times, modern Japanese architecture has sought to maintain the character of traditional Japanese design in combination with the advancements of western technology (Nose, 2000, p.65). By the use of materials such as wood and stone, the use of void and its concern for texture and craftsmanship (p.33), it recalls the old ways of traditional, architecture and its spiritual connotation of ‘ ma ’ , ‘wabi sabi’ and ‘shintai’ Additionally, the deep

consideration for temporal experience can also be seen in modern Japanese architecture, best exemplified in the works of Tadao Ando - in his use of light and sequencing of journey through space. (Veal, 2002, p.7)

In the next chapter, I will be analysing a typical Japanese tea house and Tadao Ando’s Water temple, in the pursuit of identifying how body-mind design has been used in the approach of these buildings. They will be examined from an experiential perspective of of space and time, based on narrations from from Brian Corr (2018) and Shefali Bhimani (1995), but also, from my own studies of photographs, plans and sections I will start by looking at the journey when approaching the entrance and how the temporal and spatial perception are manipulated upon during this journey Next, I will investigate the use of light and shadow and how the integration with nature plays a roll in the temporal, spatial and sensory experience, and how the regulation of light adds to the experience of space and time. Finally, I will end with concluding remarks, summarising the points given in this essay, with final words about its implication and application in future projects.

A cluster of summer trees, A bit of the sea, A place evening moon

- Tea Master Enshu, on the nature of the sensations evoked when walking through the roji. (Okakura, 1906, p.61))

3.2: Site plan the journey through the tea garden to the teahouse. (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on drawing from Castile, 1971, p.109)

The spatial and temporal manipulation of the tea house can already be sensed at the entrance. The thick wall that encloses the tea garden denies views into the place unless viewed from the gate itself. This also works as a marking entering a different world that is separate from reality, or, in for religious connotations, as the border between the sacred and the profane.

The first step of the journey is to the changing room for a change of clothes or, as Bhumani suggests, “to straighten the kimono” (Bhumani, 1995, p.112). By looking at the site plan, the sequencing of the journey until its final stop is very clear, which forces the visitor to take his time in order to build up anticipation, to be more mindful of the present. As the visitor becomes more aware of his surroundings, he may become more engaged in the moment, or, for religious connotations, to prepare the participant of the tea ceremony to get into the right state of mind for meditation. The dense planting of greenery and trees add to this experience by evoking a sense of peace and balance, adding on to the experienced alienation from the outside world. The winding paths, together with the planting, could also be experienced to be slightly disorientating, adding on to the previous points of alienation, presence by a sense of temporal infinitude – time does not matter anymore, apart from perhaps the natural rhythms of time.

Finally, the odd spacing of the steppingstones and the texture of materials of the waiting area, (for example the framing bamboo grid of the window, see figure 3.3), does not only provide a haptic experience, but also - in regard to the stepping stones – a temporal experience. The oddity in spacing prompts the visitor to slow down to consider his placing of his foot on the stone, which, in turn, prompts a body-mind connection.

The chumon (figure 3.5) – separating the inner roji from the outer roji, seems to have a similar effect to that of the entrance gate, although being simpler in appearance. One cannot help to note the gradual change of articulation in the garden too, especially in the density of the planting, the spacing of the steppingstones and the increased simplicity and naturalness in the architectural style of the chumon and inner waiting area, both typically made from wood and bamboo. These factors result in an intimate feeling of the space that prepares the visitor even further for meditation

When entering the inner roji, one might have a glimpse of the end destination (the tea house) only for the sight to disappear again, even if the steppingstones might take you in a different direction. This, interval of “hide and reveal” contributes, once more, to the disorientation of space and time, making the tea garden feel bigger than it really is.

Figure 3 5: To left, Chumon gate, notice its more simply built. Similarly, the steppingstones are smaller and less scattered in inner roji. (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

Before entering the tea house, the visitor would progress to the stone basin to “cleanse himself from the worldly dust, (Bhimani, 1995, p.117). The stone basin is rather naturalistic in appearance, building on the previous point of increased simplicity. Paradoxically, this sense of purity and earthiness seem to extend one’s perception of time whilst shortening the sense of space, as the calming features of water, rocks and plants prompts an inward-looking effect of heightened awareness of the senses, which may evoke a feeling of being lost in a neverending moment

Figure 3 6: To left, the stone water basin., notice its low to the ground. Right, the perspective from the stone basin – the tea house can be closely seen at this stage (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

When approaching the tea house at the end, the visitor is denied insight into the space inside the tea house. It is not upon entering through the small doorway (you crawl into the building) that its contents become revealed. The idea of ‘hide and reveal’ is once more apparent in the design, adding to the built-up anticipation from the made journey.

Figure 3 7: Arrival to the tea house. Notice nigiri guchi and the fact that you are unable to look inside until you enter the room (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

The multi sensory connection is frequently used in the tea house and garden by the selection of the plants, materiality of the materials, for example the stone basin, the waiting arbour and the wooden, naked look of the columns and the ceiling of the tea garden. All contributes to the sense of tranquillity balance and harmony, one of which could be seen as an embodiment of the viewed balance and the interconnectedness of the self and nature. The windows contribute to this effect by its placing and framing of certain views of the garden, that aids in the practice of mindfulness – physically, mentally and spiritually

Figure 3 8: The relationship between the interior of the tea house and nature two separate realms of immersive spaces. (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

The restriction of light is particularly worth of interest as it contradicts the western equation for light with large openings. The shoji screens soften the flow of light to only illuminate the space “just enough”. Thus, the contrast between light and shadow is felt to be stronger, which I believe results in a higher appreciation for the incoming light, to the restriction of it, recalling the zen attitude of beautify in scarcity (wabi-sabi).

the light enters. Looing from the outside, the only clue of the inside is through the shadows, (Larsen, 2019).

Figure 3 10: The interior of Shungure-tei teahouse. Note the sense of spaciousness, (Pinterest, n.d)

“When water, wind, light, rain, and other elements of nature are abstracted within architecture, the architecture becomes a place where people and nature confront each other under a sustained sense of tension. I believe it is this feeling of tension that will awaken the spiritual sensibilities latent in contemporary humanity.” - Tadao Ando. (Framption, 1991, p.79

Like the tea garden, the use of sensory experience starts before the site. Corr describes the hill (Corr, 2018, p.34) “to gently glow caused by the reflection of the granite gravel. The tone of the architectural language comes across as bright, light and almost divine, in which the white colour of the wall and surrounding idyllic landscape augment.

4.3. Step 1. The site, laying on a hill, is approached. (Salman Ismael, 2021, based on images from google)

Upon entering the door, a second wall is facing the traveller, forcing him to turn right to walk around the solid wall. Like the tea garden, the path to the entrance is not straight – the prospect of the prospect of the end goal (the temple) is thus concealed, which, equally, incites curiosity of what one may find around the corner. Moreover, the narrow placement of the walls, acts as a contrast to the previous experience of the bright and open landscape. The space becomes darker.

Figure 4.4: Step 2 When passing through the doorway, one is faced with another wall, forcing the visitor to walk around, (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images form google).

After walking around the wall, the elliptical lotus pond appears Again, the traveller is met with a change of language from dark and confined to bright and open The element of water provides a sense of tranquillity and peace that was once established upon reaching the site. The sounds of the gently flowing water and the reflection of light recalls a similar effect of the one in the Japanese tea garden. Moreover, the use of lotus flower also implies spiritual meaning, as it is widely viewed as a symbol for purity and enlightenment (Marigold, 2022).

Figure 4.5: Step 3. Approaching the lotus pond. It is now visible, however the stairs appear hidden, until it reveals itself suddenly (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images from google).

From the studies of the photographs, the staircase seems to be hidden from view up until immediate proximity where it suddenly manifests. The only clue would perhaps be the handrails as they arise from the ground, but even then, the narrowness of them makes them appear almost undistinguishable.

When standing in front of the staircase, the darkness of the space – where no end of the staircase seems to be seen, and the coolness caused by the drop in temperature provokes an uncomfortable, dismantling feeling of descending into the unknown

The contrast to the lotus pond also become increasingly apparent as the traveller walks down the stairs In terms of the interplay from light to darkness, comfort to discomfort, and noise to silence, it becomes a transformative experience as the sensory perception is heightened. Consequently, time may seem to stand still.

Figure 4 6: Step 4. Descending the staircase. A feeling of “Entering into the depth of a womb” or to the unknown is evoked due to the lack of light (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images from google).

Step 5: The Corridor

As the door to the temple lays on the left side, the traveller is walking downstairs in oblivion of when and where the staircase will end, until it abruptly becomes known. Upon entry, the traveller is met by an unexpected burst of light and colour from the corridor leading up to the main hall, contrasting the previous experience. The dependence on a single light source of the window seems to further amplify the illumination, forming star contrast by the otherwise dark and corridor. The disorienting feeling of the space evokes the perception that evidence of time is only really felt by the movement of the shadows from the walls.

4 7: Step 5. After coming down the stairs, one is met with darkness again in the narrow tunnel, seeing light at the end of the tunnel through the floor-to-wall window, (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images from google).

Finally, as the main hall appears, the traveller is, once more, confronted with brightness and a sense of expansion of space As a consequence of the previous state of deprivation of these attributes, the sensory perception of the space become much more profound The journey to the temple becomes a transformative, awakening experience – physically as well as psychologically

Figure 4 8: Step 6 At the end of the tunnel, one is met with a brightness of colour The entrance to the main hall appears, (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs

The water temple is connected to nature In the use of a large body of water, as well as its location on a natural setting. Further note can be made in the spatial transitioning in the landscape – from uphill to downhill- and forward to background, Ando makes use of nature and the sensory experience derived in the formation of the contrasts between the tone of the sequences of the journey (also see step 3.).

Like tea house, the water temple embraces shadows and the contrast between light and darkness. The contrasts between them creates an effect on the user experience, as is demonstrated in the corridor leading to the main hall and on the difference in tone between the lotus pond and the staircase. In addition, he also takes advantage of the reflection of the light for illumination, as evidenced in the body of water and the granite gravel

Figure 4.10: The strip of light from the floor-to-wall window in the middle of the darkness of the tunnel add to the consistent play between illumination and darkness in Water Temple (Cawood, 2016).

Overall, the benefits of body-mind design are many – both in a physical sense, but also psychologically, spiritually and experientially. It involves the human self, his environment and his body, and their relationships and integration with one another. The concepts of bodymind design have long been used by the Japanese, emerging from Zen and Taoist values. However, the principles can still be used globally as the qualities rely on four key points: the use of sequencing of journey, their use of light and shadow, their accentuation in void and emptiness, and their integration of nature for multi-sensory experience. Although the western influence is evident in contemporary Japanese architecture, they have still maintained the essence of body-mind design form Japanese tradition, and instead infused its timeless qualities with modern technology. This is particularly evident in Tadao Ando’s water temple, in his use of light and water in unison with concrete and granite gravel. Although not directly “natural” the granite gravel gives a haptic feel similar to that of rocks in the tea garden, whereas concrete have a similar role as the solid walls of the tea garden.

Ultimately, this study was intended to expand on my knowledge of body-mind design in the hope of implementing these qualities into my own design. I have long been attracted to minimalistic design and how, by using simple forms, one could create an aesthetically pleasing place that is not only beautiful but also poetic in its expression and use of void Having written this paper, I believe that the word I sought was the Japanese term ‘Ma’ , in which I have come one step closer in discovering its formula.

Bhimani, S., (1995): An Inquiry into the Making of Japanese Architecture through the Study of Tea Houses, pp 99120. Available at:

https://repository.arizona.edu/bitstream/handle/10150/555233/AZU_TD_BOX352_YARP_1102.pdf?sequence= 1 [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Castilo, R (1971), p.45, The way of Tea [book]

Corr, B., (2018): Immersive Experience: Evoking the Elements of Contemplative Space in Japanese Architecture, pp,.23-34 Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/162631458.pdf [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Frampton, K (1991): Tadao Ando, p.24. Available at: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_348_300085246.pdf [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Hashimoto, F. (1981), p.45, Architecture in the Shoin Style: Japanese Faudal Residences [book]

Iinmura, T. (1993), pp.34-39 A Note for MA: Space/Time in the Garden of Ryoan-Ji Available at: http://www.mfjonline.org/journalPages/MFJ38/iimura.html [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Ikemi, Y. and Ishikawa, H. (1979), pp.1-4 Integration of Occidental and Oriental Psychosomatic treatments. Available at: https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/287347 [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Ikeno, O., and Roger, J., (2002), p.195. The Japanese Mind: understanding contemporary Japanese culture [book]

Izosaki, A., 2006, pp.94-95 Japan-Ness in Architecture. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/562405044/Arata-Isozaki-Japan-ness-in-Architecture-2006-The-MIT-PressLibgen-li# [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Kim, Y., (2013), p.52 Recovering Sensory Pleasure through Spatial Experience Available at: file:///C:/USERS/N0965710/DOWNLOADS/RECOVERING_SENSORY_PLEASURE_TH.PDF [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Ko, Y., (2006), pp.1-22 Body-Mind Unity as Dominant Design Philosophy of traditional Japanese Tea House Available at: https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO200723421068738.pdf [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Tsu L., (n.d.), transl. un Mcdonald, J. (1996), p.5, Tao Te Ching Available at: https://www.unl.edu/prodmgr/NRT/Tao%20Te%20Ching%20-%20trans.%20by%20J.H..%20McDonald.pdf [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Lee, L., (2016), p.94 Space for collaboration from non-western perspectives: communication in an organiation Available at: https://etd.uum.edu.my/6026/2/s92754_01.pdf [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Levrat, F., (1994), pp.1-4, Addition by Subtraction Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41845656?saml_data=eyJzYW1sVG9rZW4iOiIwNWZjMDY2Zi1iMzU2LTQ4OTktOD AxNS0yODYzNDYxOTE1Y2YiLCJpbnN0aXR1dGlvbklkcyI6WyIxMTgxMTM5Mi0yMThiLTRiMjEtYTgwZS1mOGY2Mm QwZjJiZDYiXX0 [Accessed 12-03-2023]

Lobell, J., (1979), p.64 Between Silence and Light Available at: https://archive.org/details/betweensilenceli0000lobe/mode/1up [Accessed 12-03-2023]

I.Mash (2012), Chashitseu – The Japnasese teahouse: An Aesthetic System pp 1-4. Available at: https://publik.tuwien.ac.at/files/PubDat_216243.pdf [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Marigold S, (2022), Lotus Flower: Ist Meaning, Symbolism & Symbolism Available at: https://www.saffronmarigold.com/blog/lotus-flowermeaning/#:~:text=Because%20lotuses%20rise%20from%20the,strength%2C%20resilience%2C%20and%20rebirt h [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Nitschke G, (1996), p.117 ), Japanese Gardens 1-4. Available at: https://www.pdfdrive.com/japanese-gardense176211890.html [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Nitschke, G., (2018), Ma: Place, Space, Void Available at: https://www.kyotojournal.org/culture-arts/ma-placespace-void/#_ftn3.ttps://www.pdfdrive.com/japanese-gardens-e176211890.html [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Norberg Schulz, C., (1963), p.28, Intentions in Architecture Available at: https://pdfexist.com/download/3339926-Intentions%20In%20Architecture.pdf [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Norberg-Schulz, C., 1974, p.7), Existence, Space & Architecture. Available at: https://archive.org/details/existencespacear00norb [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Nose, M., 2000, p.65 Japan Modern. Available at: file:///C:/Users/N0965710/Downloads/Japan%20modern_%20new%20ideas%20for%20contemporary%20living. pdf [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Nute, K., (2021), p.4 Time in the Japanese Room. Available at: file:///C:/USERS/N0965710/DOWNLOADS/TIMEINTHETRADITONALJAPANESEROOM.PDF [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Okakura, K., pp.17-34 The Book of Tea Available at: http://pdf-objects.com/files/Book-Of-Tea.pdf [Accessed 1203-2022]

Sadler, A., (1962), pp 13-102. Cha-No-Yu: the Japanese tea ceremony. Available at: https://archive.org/details/chanoyujapaneset0000sadl [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Saito, Y , (2012), pp.223-228 Everyday Aesthetics: Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ntuuk/reader.action?docID=716787 [Accessed 12-03-2022]

Schinzer, Nishida., T. (1958) pp.3-32. Intelligibity and Nothingness Available at: https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/Intelligibility.pdf Accessed 12-03-2022]

Snodgrass, A., (2006), pp.48-138 Thinking through the gap: The space of Japanese Architecture Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/13264826.2011.601541?needAccess=true Accessed 12-032023]

Suzuki, T.,(1959), pp.295-296 Zen and Japanese culture Available at: https://terebess.hu/zen/SuzukiCulture.pdf Accessed 12-03-2023]

Trisno and Lianto, 2021, pp.2-22 How Lao Tze an Confucius’ philosophies influenced the designs of Kisho Kurokawa and Tadao Ando Available at: file:///C:/Users/N0965710/Downloads/s40410-021-00138-x%20(1).pdf Accessed 12-03-2023]

Veal, A., (2002), pp.1-7 Time in Japanese architecture, tradition and Tadao Ando. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridgecore/content/view/E794C297502F81CC4B14EE44D6DB5D55/S1359135503001878a.pdf/time-in-japanesearchitecture-tradition-and-tadao-ando.pdf Accessed 12-03-2023].

Wittmann, M., (2019), pp.42-43 felt Time: The Psychology of how We Perceive Time. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ntuuk/reader.action?docID=4410132 Accessed 12-03-2023]

Figure 1.1: Traditional Japanese Tea House, The Garden Centre, (n.d.)

https://www.buildajapanesegarden.com/japanese-garden-materials/japanese-style-buildings/japanese-teahouse/

Figure 1.2: Water Temple, Modlar (n.d.)

https://www.modlar.com/photos/2209/water-temple-exterior/

Figure 2.1:. Seeing the universe in a single flower, (Pearman, n d)

https://magnifissance.com/arts/japanese-arts/ikebana/

Figure 2.2: The impermanence of life – such as that of the Japanese Cherry tree leaves, (Shinners, 2016)

https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/sakura-cherry-blossom-soft-color-illustration-161104055

Figure 2 3: Ma as experiential space in Shiguretei tea house (Song, 2018)

https://japanobjects.com/features/kiyosumi-garden

Figre 3.1: Kiyosumi Garden, showing the tea house in the background, (Dayman, 2019)

https://japanobjects.com/features/shoji

Figure 3.2: Site plan the journey through the tea garden to the teahouse (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on drawing from Castile, 1971, Tea Ceremony, p.109)

Figure 3.3: Step 0-2 of the journey to tea garden, (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

Figure 3.4: To left, details of the bamboo lattice of the window in the waiting arbour, the steppingstones in the outer roji. (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

Figure 3 5: To left, Chumon gate, notice its more simply built. Similarly, the stepping stones are smaller and less scattered in inner roji. (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

Figure 3 6: To left, the stone water basin Right, the perspective from the stone basin – the tea house can be closely seen at this stage (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

Figure 3 7: Arrival to the tea house. (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

Figure 3 8: The relationship between the interior of the tea house and nature (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs from Bhimani, (1995).

Figure 3.9: Shadow silhouettes from shoji screens (Larsen, 2019).

Figure 3 10: The interior of Shungure-tei teahouse. Note the sense of spaciousness. (Pinterest,n.d)

https://www.pinterest.se/pin/652459064737305285/

Figure 4.1: Water temple, (ArquitecturalViva, n.d ).

https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/templo-del-agua-higashiura

Figure 4.2: The plan of journey to the temple (Salman Ismael, based on Google Earth, n.d.)

https://earth.google.com/web/@34.54627135,134.98927878,44.45167496a,164.57400444d,35y,154.65429004h,39.45229194t,0r

Figure 4.3. Step 1. The site, laying on a hill, is approached, (Salman Ismael, 2021, based on images from google)

Figure 4.4: Step 2 When passing through the doorway, one is faced with another wall, forcing the visitor to walk

around, (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images form google).

Figure 4.5: Step 3. Approaching the lotus pond. (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images from google).

Figure 4 6: Step 4. Descending the staircase (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images from google).

Figure 4 7: Step 5. After coming down the stairs, one is met with darkness again in the narrow tunnel (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on images from google).

Figure 4 8: Step 6 At the end of the tunnel, one is met with the brightness of colour (Salman Ismael, 2023, based on photographs

Figure 4.9: The relationship between the water temple and nature (Rogers, n.d.)

https://weburbanist.com/2016/06/27/reflecting-on-a-master-architect-10-water-centric-works-by-tadaoando/

Figure 4.10: The strip of light from the floor-to-wall window in the middle of the darkness of the tunnel add to the consistent play between illumination and darkness in Water Temple (Cawood, 2016).

https://en.japantravel.com/hyogo/honpukuji-the-water-temple/33221