Inside This Issue From the President’s Desk…

2023 Judges & Law Clerks

Dinner……………………..……..6

The High Court’s Criminal Justice Docket: A Preview of some of the New Jersey Supreme Court’s Criminal Law and Quasi-Criminal Law Cases Pending Decision…………16

Neurosurgeon Used Medical Expertise to Help Disabled Military Vets……………………………..30

New voting Machines in Mercer County…………………………..32

Mercer County Clerk Issues Warning to Passport Applicants…………..34

Benefits of Automated Document Assembly and Management for NJ Firms ...36

Skip Tracing...It Really is an Art.....42

Upcoming Events

MCBA Golf Outing

September 28, 2023

Awards Gala

October 27, 2023

September has always been my favorite month. As a lifelong nerd, I have always loved the Back to School feeling of fresh starts, new challenges, and the chance to reconnect with friends and acquaintances. (Plus, my birthday! 21 again.) For members of the MCBA, September also means a return to the hustle and bustle of the court year and a full slate of fall events, as we enter the busiest stretch of our year.

Earlier this month, I was honored to preside over our Memorial Service during the Opening Ceremony of the Courts. We honored 12 colleagues who passed away in the last year. They practiced in a variety of practice areas – from criminal defense to civil trial work to transactional practice –and in a wide variety of types of offices – big firms, smaller firms, and solo practice. But despite those differences, they all shared one profession, with its challenges and triumphs. Certainly, a common thread among all we honor is dedication to clients, collegiality to fellow practitioners, and intellectual vigor. It was extremely moving to hear from their family members, friends and colleagues, and take a moment to appreciate their lives both in and out of the courtroom.

At that event, I also made a special announcement. Moving forward, the Professional Lawyer of the Year Award will be renamed in honor of Judge Shuster, who passed away too soon last spring. It is truly the highest honor the MCBA can bestow, and will ensure that his legacy will live on for decades to come. Recipients of the Hon. Neil H. Shuster Professionalism Award will be those who possess his qualities of collegiality, competence, integrity and diligent work ethic. Most importantly, recipients will share his selfless humility – Judge Shuster notably was a friend to all he encountered, regardless of job or status, and was uniquely able to laugh at himself and his foibles, while maintaining an aura of the utmost gravitas. We still miss his booming voice, his boisterous laugh, his advice and guid-

APublicationoftheMercerCountyBarAssociation

APublicationoftheMercerCountyBarAssociation Volume 42, Issue 3

MargaretA.Chipowsky,Esq.

Summer 2023

ance, and his obsession with all things Rutgers. But in this way, every year, we will honor a jurist and friend who was truly the very best of us.

Summer 2023 Volume 42, Issue 2

Officers

Margaret A. Chipowsky

609-815-7584 President

Jennifer Zoschak

President–Elect

609-844-0488

609-896-9060 Vice President

Brian W. Shea

I also have been honored to welcome this year’s law clerks, both at a casual lunch at the courthouse, and at our Judges and Law Clerks Dinner on September 20th. It was wonderful to see so many of our members in attendance and eager to make the new clerks feel welcome! This year’s clerks are an extraordinary group, and I am certain that they will bring a freshness and enthusiasm to their roles in assisting our bench. I was delighted to see so many current and retired judges at the event – we all benefit from the continued excellent working relationship between the bench and bar.

Ross J. Switkes

856-662-0700 Treasurer

Jennifer Downing-Mathis

609-610-6003 Secretary

Trustees

2023

Jennifer Downing-Mathis

Christopher L. Jackson

Evan J. Lide

Amanda E. Nini

Lauren E. Scardella

2024

Kiomeiry Csepes

Jennifer Weisberg Millner

Robert F. Morris

Joseph Paravecchia

Jessica A. Wilson

2025

Frank P. Spada, Jr.

C. Robert Luthman

Bryan M. Roberts

Nikki J. Davis

Marc A. Brotman

Michael Kahme

Immediate Past President

Michael Paglione

NJSBA Representative

Anita Mangat

Executive Director | MCBA Office

On that same evening, we presented Kiomeiry Csepes with our Young Lawyer of the Year award. Kiomeiry has been a shining star in both the county and state bars, and has contributed extensively to social programs and CLEs. Her personal story is inspirational, and her practice serves those most in need. I was honored to present her with the award and thrilled to share the evening with her wonderful family.

609-989-6351

609-896-2000

609-896-9060

609-730-3850

609-587-1144

609-241-7111

609-896-9060

609-896-9060

609-989-6351

856-234-6800

215-877-2653

609-594-4000

609-896-9060

609-587-9100

609-275-0400

609-734-6383

609-275-0400

609-585-6200

The MERCER COUNTY LAWYER is published four times per year; Winter, Spring, Summer and Fall. Advertisements appearing in the MERCER COUNTY LAWYER are the viewpoints of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Mercer County Bar Association or its members. The MCBA does not vouch for the accuracy of any legal analysis, citations, or opinions expressed in any articles contained herein. Individuals who are interested in joining the Association, placing advertising, or contributing articles should contact the Bar Association office at 609-585-6200, or e-mail info@mercerbar.com.

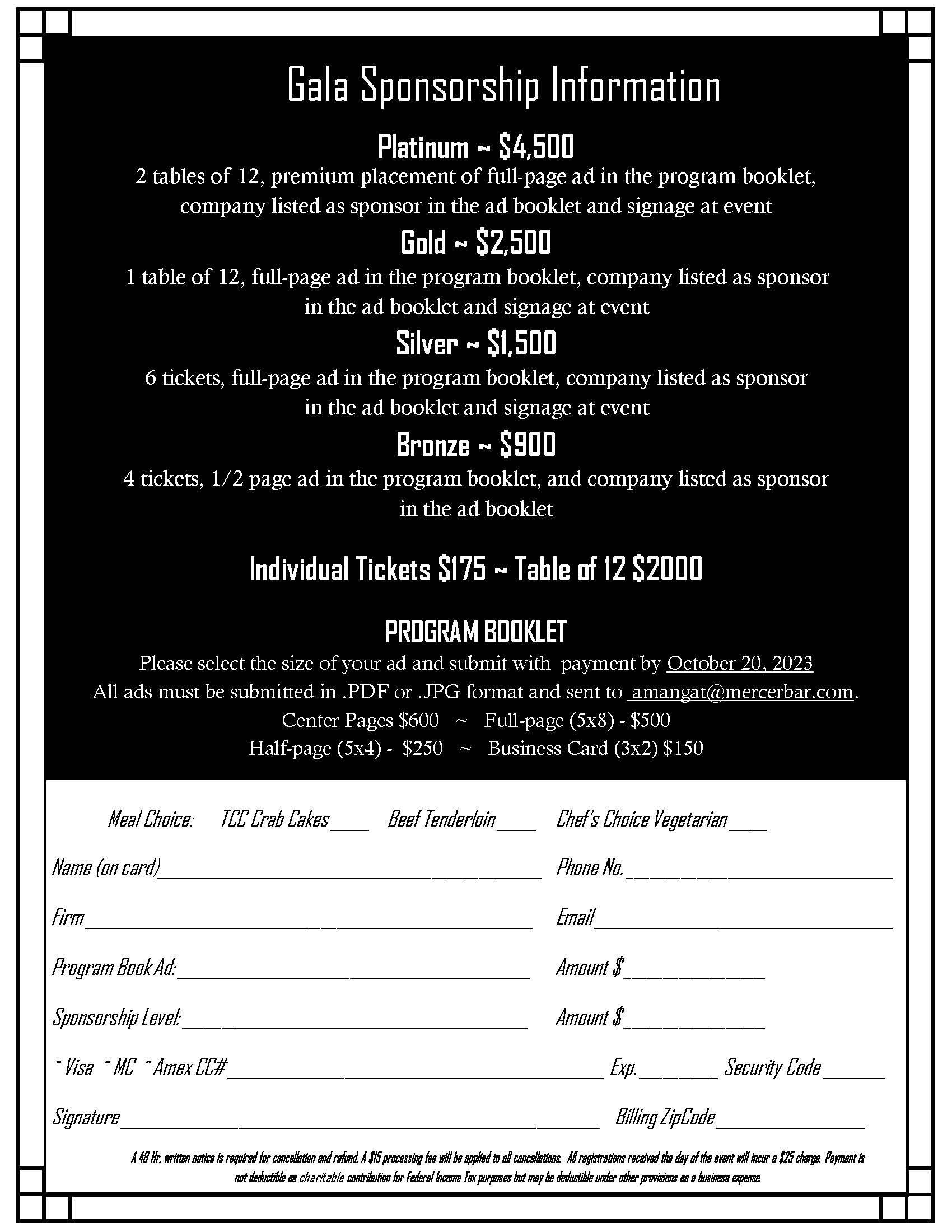

There are many exciting events on tap for our members in the coming months! On September 28, barring more apocalyptic weather, we will have our rescheduled Golf Outing at Hopewell Valley Golf Club. No doubt, the highlight of our social calendar for the year is our Awards Gala, on Friday, October 27, at the Trenton Country Club. Our theme is 007, and appropriate outfits are encouraged! On that evening, we will present Mercer County Prosecutor Angelo Onofri with the Michael J. Nizolek Award, which is the MCBA’s highest honor. Arthur Sypek will receive the Harry O’Malley Award, which celebrates excellence in service to both the bar and the community, and Anchor House will be honored as our Community Partner. There will be a silent auction with many fabulous items available, and I encourage everyone to attend. There are multiple opportunities available for sponsorship! I promise my remarks that evening will be very short!

As always, we are ready to meet all your CLE needs with our umpteenth edition of Xtreme CLE. Our CLE chairs have been hard at work developing a schedule of programs to meet any educational need, and I hope all of you will take advantage of this opportunity to obtain many of your needed credits. The program is once again via Zoom, on November 28 and 29, and the price is a mere $135 for our members.

As always, thanks to our staff for pulling together all these events, and of course to you, our members, for being enthusiastic participants in all our activities. I look forward to seeing you all!

A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

M e r c e r C o u n t y APublicationoftheMercerCountyBarAssociation

Page 2 Summer 2023

Upcoming Events & Meetings

All Attorneys Are Invited To Attend Bench Bar Meetings

Family Bench Bar

Thursday, October 5, 2023 | 3:30 pm

• This meeting will be held virtually via Zoom

• Register here for this meeting

Lawyers Care

Thursday, September 14, 2023 | 5:00 pm

• This program will be held virtually via Zoom

• Please contact Loren at lromberger@mercerbar.com to volunteer

Municipal Bench Bar

Thursday, October 19, 2023 | 3:30 pm

• This meeting will be held virtually via Zoom

• Register here for this meeting

007 Awards Gala

Friday, October 27, 2023 | 6:00 pm

• Trenton Country Club

• Register here for this meeting

Holiday Party

Thursday, December 7, 2023 | 5:30 pm

• Save the Date!

• Trenton Country Club

Page 3 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

The High Court’s Criminal Justice Docket: APreview of Some of the New Jersey Supreme Court’s Criminal Law and Quasi-Criminal Law Cases Pending Decision

Submitted by: Joseph Paravecchia, Esq.

Introduction

The New Jersey Supreme Court’s 2023–2024 argument term will commence in September,1 during which the Court now at full strength with the historic addition of recently-confirmed Associate Justice Michael Noriega2 will hear arguments regarding the state’s most important cases. The new term promises to offer opinions as, if not more, intriguing as those released in the 2022–2023 term, which for the criminal practitioners reading this article guided us on issues involving, among others, crime victims’ rights3, defendants’ rights to counsel and against self-incrimination4, expert evidence5, internal affairs6, pretrial diversion7 , and searches and seizures8. Similar, yet novel, legal issues await decision in the cases either pending argument or already having been argued. And while they may not necessarily be decided before the conclusion of the new term, those cases are worthy of attention and discussion in advance of September.

This article will examine three random cases either on the Court’s 2023–2024 argument calendar or pending decision after argument,

1 Supreme Court Argument Schedule 2023-2024 Term, NJcourts.gov (July 29, 2023), https://www.njcourts.gov/courts/supreme/arguments.

2 Collen Murphy, Senate Unanimously Approves Historic Nomination of Michael Noriega to NJ Supreme Court, New Jersey Law Journal (June 30, 2023), https://www.law.com/ njlawjournal/2023/06/30/senate-unanimously-approves-historic-nomination-of-michaelnoriega-to-nj-supreme-court/. See also Order – Judge Sabatino – Conclusion of Temporary Assignment to the Supreme Court, NJcourts.gov (July 29, 2023), https:// www.njcourts.gov/notices/order-judge-sabatino-conclusion-of-temporary-assignmentsupreme-court.

3 State v. Ramirez, 252 N.J. 277 (2022).

4 State v. Erazo, ___ N.J. ___ (2023); State v. Bullock, 253 N.J. 512 (2023); State v. Wade, 252 N.J. 209 (2022).

5 State v. Olenowski, 289 A.3d 456, 253 N.J. 133 (2023). See also infra at Part II.

6 State v. Higgs, 253 N.J. 333 (2023).

7 State v. Gomes, 253 N.J. 6 (2023).

8 Facebook, Inc. v. State of New Jersey, ___ N.J. ___ (2023); State v. Cohen, ___ N.J. ___ (2023); State v. Williams, 254 N.J. 8 (2023); State v. Smart, 253 N.J. 156 (2023); State v. Miranda, 253 N.J. 461 (2023); State v. Torres, 253 N.J. 485 (2023).

Page 14 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

which concern criminal law and quasi-criminal9 law questions. The cases are presented in no particular order, and nothing should be construed to suggest that one case deserves more emphasis than the others. Each case is unique in law and in fact and will undoubtedly affect the practice of law going forward.

I. State v. Allen

We begin with State v. Allen, 10 in which the Court will decide whether an investigator’s trial testimony narrating surveillance video footage deprived the defendant of a fair trial.11 An Asbury Park police officer patrolled an area near where a shooting occurred hours earlier, for which no one had yet been arrested.12 The officer observed defendant behaving suspiciously and in a manner which the court determined warranted an investigative stop. During the encounter, the officer felt the outline of a handgun in the front of defendant’s sweatshirt.14 “Defendant slapped the officer’s hand away and began to run[,]” after which the officer ordered defendant to stop at gun point.15 Defendant ignored the officer’s instructions and, while continuing to run, turned towards the officer’s direction, pointed a gun at him, and fired.16 The officer returned fire and struck defendant in the leg, disabling him.17

A grand jury returned an indictment charging defendant with, among other things, attempted murder and firearms offenses.18 At trial, during the officer’s testimony, the prosecutor introduced surveillance footage depicting both the pursuit and the shooting, in which the officer identified himself and defendant.19 Defendant also testified and admitted to possessing a handgun for which he did not have a permit.20 He further explained that he threw the hand-

9 New Jersey “courts have long held that prosecutions for a violation of [motor vehicle law] provisions result[] in a prosecution of a quasi-criminal action.” State v. Widmaier, 157 N.J. 475, 494 (1999). See also State v. Laird, 25 N.J. 298, 303 (1957) (holding that classification of crimes as quasi-criminal “is in no sense illusory . . . [as] it has reference to the safeguards inherent in the very nature of the offense, the punitive quality that characterizes the proceeding, and the requirement of fundamental fairness and essential justice”). The case discussed in Part II infra concerns quasi-criminal law, while the case discussed in Part III infra does not cleanly fit that characterization. However, the circumstances in the latter case directly involve several criminal justice components, which ultimately conform with the theme of this article.

10 No. A-0060-19 (App. Div. January 24, 2022), certif. granted, 251 N.J. 33 (2022). Prior to submission of this article for publication, the Supreme Court decided Allen, affirming as modified the Appellate Division’s decision. See State v. Allen, ___ N.J. ___ (2023).

11 A-55-21 State v. Dante C. Allen (086699), NJcourts.gov (July 29, 2023), https:// www.njcourts.gov/courts/supreme/appeals.

12 Allen, No. A-0060-19 (slip op. at 2).

13 Id. (slip op. at 3, 12–13). An investigative stop is “a procedure that involves a relatively brief detention by police during which a person’s movement is restricted.” State v. Nyema, 249 N.J. 509, 527 (2022) (citations omitted). No warrant is needed to justify the stop “if it is based on specific and articulable facts which, taken together with rational inferences from those facts, give rise to a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.” Ibid. (internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

14 Allen, No. A-0060-19 (slip op. at 3).

15 Id. (slip op. at 4).

16 Ibid. See also infra note 43.

17 Ibid.

18 Id. (slip op. at 2).

19 Id. (slip op. at 4).

20 Ibid.

Page 15 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

THE HIGH COURT’S CRIMIINAL JUSTICE DOCKET

gun during the pursuit and it randomly discharged.21 An expert witness from the New Jersey State Police countered defendant’s version of events, concluding that the handgun’s “internal mechanism would not allow the firing pin to move forward unless the trigger is pulled all the way through with the requisite force.”22

Notably, a detective from the Monmouth County Prosecutor’s Office who collected the relevant surveillance footage but did not participate in the pursuit and arrest testified while the prosecutor again played the footage for the jury.23 The detective narrated defendant’s flight from the officer and opined on when defendant discharged his handgun by reference to a “muzzle flash.”24

The jury found defendant guilty of, among other things, attempted murder, for which the trial court sentenced him to an eighteen-year term of incarceration subject to the No Early Release Act.25

On appeal, defendant contended that the trial court erred when it allowed the detective to narrate portions of the surveillance footage that the jury could otherwise interpret on its own.26 The Appellate Division agreed, finding that the detective’s testimony “‘intrude[d] on the province of the jury by offering, in the guise of opinions, views on the meanings of facts that the jury is fully able to sort out.’”27 The detective did not have first-hand knowledge of the incident, and by narrating the footage, he usurped the jury’s fact-finding function and “expressed a view on the ultimate question of guilt or innocence.”28 Despite the trial court’s erroneous admission of the testimony, the Appellate Division affirmed defendant’s conviction, reasoning that the error was harmless and would not have led the jury to a verdict it would not have otherwise reached because “[t]he State had a strong case[]” through other evidence.29

The Supreme Court must now decide whether the detective’s testimony about defendant firing the gun was inadmissible lay opinion testimony that requires reversal of defendant’s convictions. To do so, the Court will likely review and apply N.J.R.E. 701, which prescribes when lay opinion testimony is admissible that is, if it “is rationally based on the witness’ perception; and” if it “will assist in understanding the witness’ testimony or determining a fact in issue.”30

21 Id. (slip op. at 5).

22 Id. (slip op. at 6) (internal quotation marks omitted).

23 Ibid.

24 Id. (slip op. at 5–6).

25 Id. (slip op. at 2). The No Early Release Act requires, for convictions for certain enumerated offenses, the imposition of “a minimum term of 85% of the sentence imposed, during which the defendant shall not be eligible for parole.” N.J.S.A. 2C:43-7.2a.

26 Id. (slip op. at 7).

27 Id. (slip op. at 8) (quoting State v. McLean, 205 N.J. 438, 461 (2011)).

28 Id. (slip op. at 9).

29 Ibid. To defeat the harmless error standard, there must “be ‘some degree of possibility that [the error] led to an unjust result. The possibility must be real, one sufficient to raise a reasonable doubt as to whether [it] led the jury to a verdict it otherwise might not have reached.’” State v. Lazo, 209 N.J. 9, 26 (2012) (quoting State v. R.B., 183 N.J. 308, 330 (2005)). See also R. 2:10-2.

30 N.J.R.E 701.

Page 16 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

It is also fair to predict that the Court will scrutinize at least two seminal decisions which guide, and arguably control, its analysis: State v. Singh31 and State v. Watson. 32

Singh directly addressed lay opinion testimony relating to video surveillance footage.33 A detective referred to an individual depicted in the recording as the defendant on two occasions during the trial.34 The detective also testified that the shoes worn by the suspect in the footage resembled the shoes found on defendant when he was arrested.35 The Supreme Court determined that it was harmless error for the trial court to allow the detective to make fleeting references to the suspect in the video as the defendant.36 The Court also determined that the trial court committed no error when it permitted the detective to testify about the similarities between the shoes because although “the jury may have been able to evaluate [on its own] whether the sneakers were similar to those in the video[, that] does not mean that [the detective’s] testimony was unhelpful. Nor does it mean that [the detective’s] testimony usurped the jury’s role in comparing the sneakers.”37

Watson similarly examined an investigator’s narration of video surveillance footage, but focused on the standard for determining if such testimony is admissible.38 The Appellate Division observed that there is “no categorical rule that prohibits such testimony[.]”39 “Rather, the critical fact-sensitive issue to be decided on a case-by-case, indeed, question-by-question basis is whether a specific narration comment is helpful to the jury and does not impermissibly express an opinion on guilt or on an ultimate issue for the jury to decide.”40

The court further emphasized that there is:

a fundamental distinction between narration testimony that objectively describes an action or image on the screen (e.g., the robber used his elbow to open the door) and narration testimony that comments on the factual or legal significance of that action or image (e.g., the robber was careful not to leave fingerprints).41

31 245 N.J. 1 (2021).

32 472 N.J. Super. 381 (App. Div.), certif. granted, 252 N.J. 598 (2022). Prior to submission of this article for publication, the Supreme Court decided Watson, reversing and remanding the Appellate Division’s decision. See State v. Watson, ___ N.J. ___ (2023).

33 Singh, 245 N.J. at 4.

34 Id. at 18.

35 Id. at 19.

36 Id. at 17. The Court cautioned, “however, that in similar narrative situations, a reference to ‘defendant,’ which can be interpreted to imply a defendant's guilt even when, as here, they are used fleetingly and appear to have resulted from a slip of the tongue should be avoided in favor of neutral, purely descriptive terminology such as ‘the suspect’ or ‘a person.’” Id. at 18.

37 Id. at 20. The Court further explained that “[t]here is no requirement in N.J.R.E. 701 that the testifying lay witness be superior to the jury in evaluating an item. . . . Th[e] Rule does not require the lay witness to offer something that the jury does not possess. Nor does it prohibit testimony when the evidence in question has been admitted, as it was here.” Id. at 19.

38 Watson, 472 N.J. Super. at 404–05.

39 Id. at 445.

40 Ibid.

41 Id. at 462.

Page 17 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

THE HIGH COURT’S CRIMIINAL JUSTICE DOCKET

Lastly, the court offered six, non-exhaustive factors to guide trial courts on “the decision whether a specific narration comment will assist the jury”: (1) background context; (2) duration of the video and focus on isolated events/circumstances; (3) disputed facts and comments; (4) inferences and deductions; (5) clarity and resolution of the video; and (6) complexity of video and distracting images.42

Guided by these principles, the Supreme Court in Allen will determine whether the detective’s narration of the portions of the surveillance footage that captured the shooting led to an unjust result.43

II. State v. Olenowski

We turn next to State v. Olenowski,44 in which the Court will decide whether drug recognition expert (DRE)45 evidence is reliable and admissible under a Daubert46 -type standard.47 Defendant was convicted of impaired driving following two separate incidents in 2015 in which he operated a motor vehicle while under the influence of intoxicating drugs as determined by two certified DREs who performed drug influence evaluations on him.48 The remaining factual circumstances in Olenowski are inconsequential. But the tortured procedural posture of the case which first involved a remand by the Supreme Court “to a Special Master for a ple-

42 Id. at 466, 466–69. The Supreme Court has since granted defendant’s petition for certification in Watson, “limited to the issues . . . [of] defendant’s confrontation clause argument; challenge to narration testimony (i.e., “play-by-play” video narration by lay witnesses); and first-time, in-court identifications.” Watson, 252 N.J. at 598 (emphasis added).

44 Much of the discussion before the Court during oral argument concerned the detective’s opinion that the surveillance footage showed defendant turn towards the officer before the handgun discharged, which, according to defendant, both unfairly supported the State’s theory that defendant acted purposely and improperly bolstered the officer’s account of what transpired. To that end, defendant maintained that “you don’t get to call a police witness to testify that the defendant is guilty. And that is what [the detective] did here.” The foregoing colloquy may foreshadow where the Court focuses its attention on appellate review.

45 A DRE is a law enforcement officer “who is specially trained to conduct examinations of drug-impaired drivers[,]” using a twelve-step protocol. Bounds v. Willers, No. 13-266 (JRT/FLN), 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 44837, at *2 (D. Minn. Jan. 13, 2016). The protocol involves:

(1) a breath alcohol test, (2) an interview of the arresting officer, (3) a preliminary examination, (4) eye examinations, (5) divided attention tests, (6) a check of vital signs, (7) a dark room examination of pupil size, (8) an assessment of muscle tone, (9) a check for injection sites, (10) interrogation of the subject and consideration of statements the subject makes as well as other observations, (11) analysis and opinion of the DRE, and (12) a toxicological analysis. Olenowski, 289 A.3d at 460, 253 N.J. at ___.

46 Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharms., Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

47 A-56-18 State v. Michael Olenowski (082253), NJcourts.gov (July 12, 2023), https:// www.njcourts.gov/courts/supreme/appeals.

48 Olenowski, No. A-4666-16T1 (slip op. at 1, 4–7).

Page 18 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

nary hearing[49] to consider and decide whether DRE evidence has achieved general acceptance within the relevant scientific community and therefore satisfies the reliability standard of N.J.R.E. 702,”50 followed by a second remand for the Special Master “to assess the reliability and admissibility of DRE evidence . . . under the [new] standard adopted” by the Court51 has produced an extraordinary ruling52 which will influence the outcome of the pending question before the Court.

The Olenowski Court framed the ultimate issue as whether “there [is] a reliable scientific basis for a twelve-step protocol that is used to determine (a) whether a person is impaired, and (b) whether that impairment was likely caused by ingesting one or more drugs?”53 But before the Court could answer that question, it first had to decide which standard to apply to analyze the reliability of DRE evidence:54 the test traditionally applied in criminal cases under Frye, which “turns on whether the subject of expert testimony has been ‘generally accepted’ in the relevant scientific community[,]”55 or the contemporary approach in Daubert that is applied in civil cases and “focuses directly on reliability by evaluating the methodology and reasoning underlying proposed expert testimony”?56

49 The Special Master, the Office of the Public Defender, the Office of the Attorney General, and multiple amici including “the County Prosecutors Association of New Jersey; the New Jersey State Association of Chiefs of Police; the National College for DUI Defense; the New Jersey State Bar Association; the Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers of New Jersey; the DUI Defense Lawyers Association; and the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey[]” participated in “an extensive hearing and heard testimony from 16 witnesses over the course of 42 days. Hundreds of exhibits were presented as well.” Olenowski, 289 A.3d at 460, 253 N.J. at ___. “In a 332-page Report of Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, released in August 2022, [the Special Master] concluded that DRE evidence should be admissible under the Frye [v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923)] standard.” Id. at 461, ___.

50 State v. Olenowski, 247 N.J. 242, 244 (2019).

51 Olenowski, 289 A.3d at 469, 253 N.J. at ___. The second remand did not involve a plenary hearing; rather, the Special Master and “all counsel agreed that the record was complete and it contained all of the evidence that would be required to assess reliability under the Daubert standard and that there was no need for further evidence.” State v. Olenowski, No. A-56, Supplement Report of Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 4 (April 13, 2023) (internal quotation marks omitted). See also Olenowski, 289 A.3d at 469, 253 N.J. at ___ (instructing, on remand, that the Special Master “may rule on the basis of the existing record, or ask for and accept additional evidence, briefing, and argument from the parties and amici.”). The Special Master subsequently issued a 59-page report, finding that “the State has clearly established that DRE evidence, in the form of opinions or otherwise, when analyzed under Daubert-[type] principles, meets the reliability standard of N.J.R.E. 702 and is therefore sufficiently reliable to be admitted in evidence.” Olenowski, No. A-56, Supplement Report of Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 5 (April 13, 2023).

52 See infra note 59 (discussing the Court’s justification for departing from precedent).

53 Olenowski, 289 A.3d at 459, 253 N.J. at ___.

54 The Court invited “the parties and amici to submit supplemental briefing on whether this Court should depart from Frye and adopt the principles of Daubert in criminal cases.”

Id. at 462, ___. The State, defendant, and “nearly all amici favor[ed] the adoption of the principles in Daubert to evaluate expert testimony in criminal cases.” Ibid.

55 See id. at 462–63, ___ (surveying the history and wisdom of the Frye test); id. at 465

66, ___ (listing examples of notable New Jersey criminal cases in which the Frye standard was applied); id. at 466–67, ___ (articulating the criticisms and shortcomings of the Frye test).

56 Id. at 459, ___. See also id. at 463–66, ___ (examining the Daubert standard in New Jersey jurisprudence).

Page 19 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

–

The Court held that the Daubert standard offered the “superior approach” to testing the reliability of expert evidence in criminal cases because it assesses all relevant factors including general acceptance.57

Focusing on testing, peer review, error rates, and other considerations better enables judges to assess the reliability of the theory or technique in question. . . . Courts are also in a better position to examine novel and emerging areas of science.

In addition, to the extent Frye and cases that follow it draw lines between scientific and technical or other specialized knowledge, . . . Daubert eliminates that unworkable distinction.

Adopting a Daubert-type standard for criminal cases[58] is also consistent with our Rules of Evidence. Like the federal rule, N.J.R.E. 702 does not require a finding of general acceptance before expert testimony can be admitted.59

Accordingly, the Court referred the case back to the Special Master to evaluate the reliability and admissibility of DRE evidence under the new standard.60 The Special Master subsequently concluded that DRE evidence “satisf[ies] the reliability standard of N.J.R.E. 702 when analyzed under the methodology-based Daubert-[type] standard now applicable to criminal and quasi-criminal cases in New Jersey[,] . . . and should be admissible in evidence.”61

Following supplemental briefing and oral argument, the Court finally appears to be equipped to decide the ultimate issue in Olenowski. And, if history proves true, we may fairly expect that the Court will endorse much, if not most, of the Special Master’s reports and recommendations.62

57 Id. at 459, 467, ___.

58 The Court noted that “[n]othing in [its] decision disturbs prior rulings that were based on the Frye standard. Future challenges in criminal cases that address the admissibility of new types of evidence should be assessed under the new [Daubert] standard[.]” Id. at 468

59 Id. at 467 (internal citations omitted). The Court acknowledged, that although its decision departed from precedent, thereby disturbing the doctrine of stare decisis, there was special justification to do so: “We find that special justification exists to replace Frye with a Daubert-type standard in criminal cases. As discussed above and by the parties and amici, both the Frye opinion itself and the passage of time have revealed shortcomings with the Frye test.” Id. at 468, ___.

60 Id. at 469, ___.

61 Olenowski, No. A-56, Supplement Report of Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law,

62 56, 57 (April 13, 2023). See also supra note 51.

See, e.g., State v. Cassidy, 235 N.J. 482, 487 (2018) (adopting “the Special Master’s findings because they are supported by substantial credible evidence in the record”); State v. J.L.G., 234 N.J. 265, 294, 301 (2018) (concurring, in part, with the Special Master’s legal conclusions); State v. Henderson, 208 N.J. 208, 283 (2011) (agreeing, in part, with the Special Master’s findings); State v. Chun, 194 N.J. 54, 149 (2008) (adopting, as modified, the Special Master’s report and recommendations). “Courts generally defer to a special master’s credibility findings regarding the testimony of expert witnesses[,] . . . but we owe no particular deference to the [special master’s] legal conclusions.” Henderson, 208 N.J. at 247 (internal citations omitted).

Page 20 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

THE HIGH COURT’S CRIMIINAL JUSTICE DOCKET

III. American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey v. County Prosecutors Association of New Jersey

We last consider American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey v. County Prosecutors Association of New Jersey, 63 in which the Court will decide whether the County Prosecutors Association of New Jersey (CPANJ) is subject to the Open Public Records Act (OPRA)64 as a public agency and whether its records are subject to the common law right of access.65

CPANJ is a non-profit, section 501(c)66 organization comprised of the twenty-one county prosecutors.67 Its goal is “to maintain[] close cooperation between the Attorney General of the State of New Jersey, the Division of Criminal Justice . . . and the twenty-one (21) county prosecutors of the State of New Jersey relative to the developing [of] educational programs[,] so as to promote the orderly administration of criminal justice within the State of New Jersey[,] consistent with the Constitution and the laws of the State of New Jersey.”68

The American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey (ACLU-NJ) requested from CPANJ, pursuant to OPRA and the common law right of access,69 certain records, including meeting minutes and agendas; records reflecting funding received by CPANJ; legal briefs filed in state or federal courts by CPANJ; and policies or practices shared with county prosecutors through CPANJ.70 CPANJ denied

63 474 N.J. Super. 243 (App. Div. 2022), certif. granted, 253 N.J. 396 (2023).

64 N.J.S.A. 47:1A-1–13. See also infra note 71 (describing OPRA generally).

65 A-33-22 American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey v. County Prosecutors Association of New Jersey (087789), NJcourts.gov (July 29, 2023), https://www.njcourts.gov/ courts/supreme/appeals.

66 26 U.S.C. 501(c). “A section 501(c) organization is an organization that is tax exempt as described in that section of the tax code[.]” McConnell v. FEC, 251 F. Supp. 2d 176, 211 (D. D.C. 2003).

67 Am. Civil Liberties Union of N.J., 474 N.J. Super. at 250, 252.

68 Id. at 251.

69 Three requirements must be met to access public records under the common law: (1) the records must be common law public documents; (2) the person seeking access must establish an interest in the subject matter of the material; and (3) the citizen’s right to access must be balanced against the State’s interest in preventing disclosure. Keddie v. Rutgers, 148 N.J. 36, 50 (1997). See also North Jersey Media Group, Inc., v. Dep’t of Personnel, 389 N.J. Super. 527, 538 (Law Div. 2006). ACLU-NJ maintained that its interest in the subject matter of the requested records was to:

(1) continue its investigation into how county prosecutors and their staff members coordinate their efforts on criminal justice policy; (2) determine if those efforts are in anyway financed by or supported with State funds or resources; and (3) adequately monitor prosecutorial transparency and accountability within the New Jersey criminal justice system.

Am. Civil Liberties Union of N.J., 474 N.J. Super. at 253.

70 Id. at 252.

Page 21 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

THE HIGH COURT’S CRIMIINAL JUSTICE DOCKET

the request, claiming that it is not a public agency71 subject to OPRA, or, alternatively, that the requested records are both exempt from disclosure72 and cannot be gathered because of CPANJ’s unconventional organizational design.73 In response, ACLU-NJ filed a complaint alleging that CPANJ violated both OPRA and the common law right of access.74 CPANJ moved to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted, which the trial court subsequently granted.75

On appeal,76 ACLU-NJ argued that the trial court erred and requested that the Appellate Division declare CPANJ a public agency subject to OPRA and the common law right of access for legal and public policy reasons.77 The court rejected those arguments and affirmed the trial court’s order.

The court “acknowledged that [OPRA’s] definition of ‘public agency’ is broad[,]”78 and includes instrumentalities created by a combination of political subdivisions that is “‘thing[s] used to achieve an end or purpose’ and, alternatively, . . . ‘[a] means or agenc[ies] through which a function of another entity is accomplished, such as a branch of a governing body.’”79 More narrowly, an organization may qualify as a public agency if it performs a governmental function.80 But “any test ‘demarcating the boundaries of what qualifies as a public agency including the . . . ‘governmentalfunction’ test[] is ‘useful only insomuch as [it] effectuate[s] application of the statutory language.’”81

71 Under OPRA, a public agency must make government records “readily accessible for inspection, copying, or examination by the citizens of this State, with certain exceptions, for the protection of the public interest[.]”

N.J.S.A. 47:1A-1. OPRA defines “public agency” as follows:

any of the principal departments in the Executive Branch of State Government, and any division, board, bureau, office, commission or other instrumentality within or created by such department; the Legislature of the State and any office, board, bureau or commission within or created by the Legislative Branch; and any independent State authority, commission, instrumentality or agency. The terms also mean any political subdivision of the State or combination of political subdivisions, and any division, board, bureau, office, commission or other instrumentality within or created by a political subdivision of the State or combination of political subdivisions, and any independent authority, commission, instrumentality or agency created by a political subdivision or combination of political subdivisions.

N.J.S.A. 47:1A-1.1.

72 See id. (itemizing the exemptions to government records).

73 Am. Civil Liberties Union of N.J., 474 N.J. Super. at 252

74 Id. at 253–54.

75 Id. at 254–55. See also R. 4:6-2(e).

53.

76 The Libertarians for Transparent Government were granted leave to appear as amicus curiae and argued that CPANJ is a public agency subject to OPRA. Id. at 255.

77 Ibid.

78 Id. at 257 (quoting Paff v. N.J. St. Firemen’s Ass’n, 431 N.J. Super. 278, 288 (App. Div. 2013)).

79 Id. at 258 (quoting Fair Share Hous. Ctr., Inc. v. N.J. St. League of Municipalities, 207

N.J. 489, 503 (2011) (quoting Black’s Law Dictionary 814 (8th ed. 2004)).

80 Id. at 259.

81 Id. at 260 (quoting Verry v. Franklin Fire Dist. No. 1, 230 N.J. 285, 302, (2017)). See also supra note 71

Page 22 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association

–

The court consequently refused to find that CPANJ was an instrumentality created by a combination of political subdivisions because nothing in the trial court record suggested that the twenty-one counties in New Jersey which are otherwise considered political subdivisions of the state “came together to form . . . CPANJ”.82 To be sure, “CPANJ was not created or authorized by statute or regulation[, and m]embership in CPANJ is optional.”83 Additionally, the county prosecutors who hold membership in CPANJ are distinct from the counties in which they operate “the county prosecutor’s law enforcement function is unsupervised by county government or any other agency of local government,” but it is subject to the primary supervision of the Attorney General and defined by the Legislature.84 Accordingly, any entity created by the county prosecutors (e.g., CPANJ)

is, at most, an instrumentality of instrumentalities or of offices. Such an entity does not constitute a public agency, because an “instrumentality” only qualifies as a “public agency” if it is “within or created by” a “principal department[] in the Executive Branch,” “the Legislative Branch,” or “a political subdivision . . . or combination of political subdivisions,” or if it is an “independent State . . . instrumentality.”85

Under OPRA, neither an instrumentality of an instrumentality, nor an instrumentality of offices, qualifies as a public agency.86

In a similar vein, the Appellate Division rejected ACLU-NJ’s argument that the records it requested from CPANJ qualify as common law documents, which are described as records generated by a public official in the performance of their public function “either because the record was required or directed by law to be made or kept, or because it was filed in a public office.”87 The court determined that the elements of a common law document relative to CPANJ’s records were not satisfied the county prosecutors voluntarily participate in CPANJ without any governmental mandate; they generally “have no constitutional or statutory extraterritorial powers to act collectively with other county prosecutors[;]” and they do not “have any official prosecutorial powers when participating as members in CPANJ activities, either individually or collectively.”88

The Supreme Court will now decide whether OPRA and the common law right of access apply to CPANJ. To do so will likely require reviewing the text and legislative purpose of OPRA, as well as the history of the common law right of access. Moreover, it is fair to anticipate that the Court will similar to the Appellate Division’s analysis examine in detail the characteristics of CPANJ to determine whether the law reaches as far as ACLU-NJ suggests. What is clear, however, are the potential consequences of the Court’s decision relating to similarly situated New Jersey organizations, which has attracted the attention of and appearances from several amici curiae, including the Libertarians for Transparent Government,89 the New Jersey State Association of Chiefs of Police, the Municipal Clerks’ Association of New Jersey, and Salvation and Social Justice and Youth Advocate Programs, Inc.

82 Id. at 261.

83 Id. at 269–70.

84 Id. at 261–62, 263 (quoting Yurick v. State, 184 N.J. 70, 80 (2005)).

85 Id. at 263–64 (quoting N.J.S.A. 47:1A-1.1).

86 Id. at 264.

87 Id. at 268, 269 (quoting Keddie, 148 N.J. at 49).

88 Id. at 269–71. The court further noted, that other than documents “necessary to maintain its tax-exempt status[,]” CPANJ’s records were not authorized by law or directed by law to be made or kept. Id. at 271.

89 See supra note 76. .

Page 23 Summer 2023 A Publication of the Mercer County Bar Association