ABowlofTwoWorld s ABowlofTwoWorld s

By Alyssa Lego

Hana sits cross-legged at the kitchen table, watching her mother, Akiko, carefully wash grains of rice in a small pot. The kitchen smells of ginger and soy sauce, and Hana’s favorite Japanese dishes are spread out on the counter.

“Mom, why do you wash the rice so many times?” Hana asks, leaning forward to see the water turn cloudy in the bowl.

Akiko smiles softly.

“It’s how my mother taught me. Rice is special - it’s the heart of every meal where I come from. Back in Japan, we ate it every day. It’s not just food; it’s home.”

Akiko’s voice carries Hana back to her childhood. She describes the small village in Japan, nestled among green hills and rice paddies. The days were simple, but life was hard after the war. “There wasn’t much to eat,” Akiko says, her hands still busy with the rice. “We were lucky if we had a bowl of plain rice with a bit of pickled plum. But no matter how little we had, my mother always made sure the rice was perfect. She said it was her way of keeping our family strong. Akiko recalls the communal effort of planting and harvesting rice. The whole village came together, their hands working side by side in the muddy fields. She talks about the festivals celebrating the rice harvest, where everyone would gather to share food, music, and stories.

The tone shifts as Akiko describes how the war changed everything. The vibrant festivals stopped, and the rice paddies were left unattended. Soldiers marched through the village, and families like hers had to make do with whatever they could find to eat. “We had to grow up fast,” Akiko says, her voice soft but steady. “I started working in a cafe when I was just a little older than you, Hana. That’s where I met your father.” Hana’s eyes widen. “At a cafe?” What was he like?” Akiko laughs, her eyes sparkling with memory. “He was kind, but he didn’t know how to use chopsticks. He made me laugh, even when I didn’t understand all the words he said.” Hana watches as her mother drains the water from the pot and places the rice on the stove. “So that’s how you came to America?” she asks. Akiko nods but doesn’t elaborate yet. “That’s only the beginning, Hana. I’ll tell you the rest while we eat.” Hana smiles, already imagining what her mother’s next story will be. She looks at the pot of rice bubbling gently on the stove, realizing it’s more than just foodit’s a piece of her family’s history.

The year was 1953.

Akiko and John sit together at the cafe where she works. Outside, the streets are busy with the sounds of bicycles and street vendors. John’s hands fidget with his coffee cup. “I want to marry you, Akiko,” he says suddenly. His words are careful, as if afraid they might break. Akiko’s heart races. She looks down, her mind swirling. She knows this is not a simple decision. Her family won’t approve. Her life will never be the same. “I ... I need to speak with my parents,” she replies, her voice soft but steady.

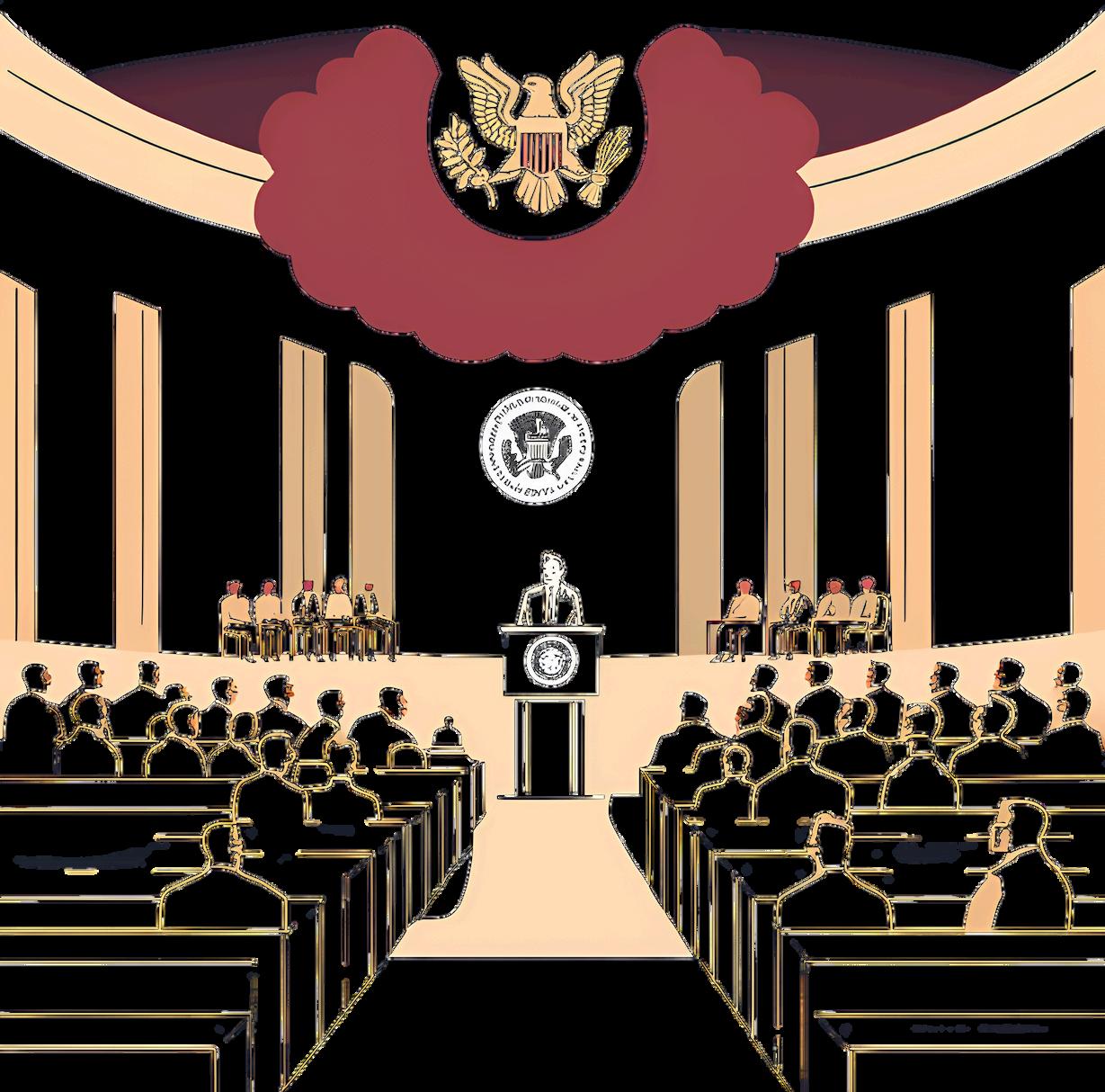

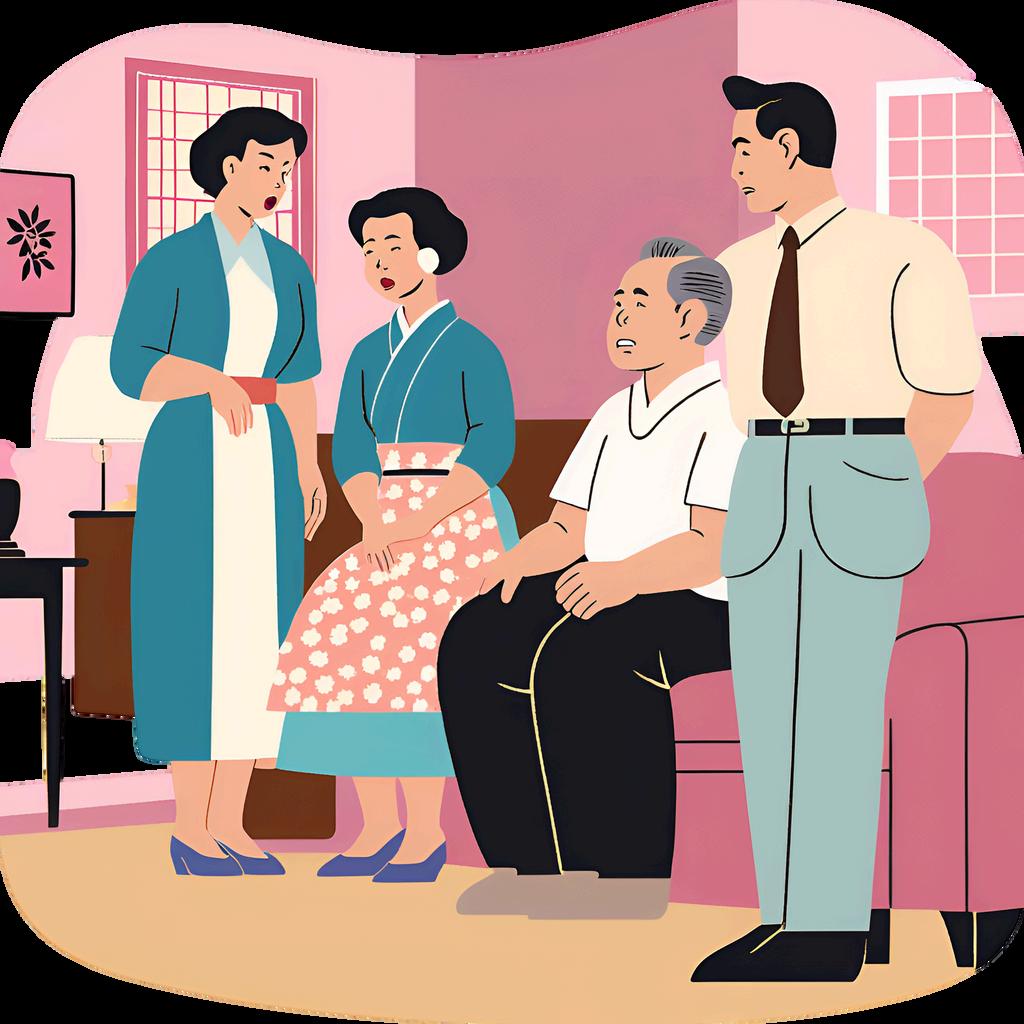

That evening, Akiko gathers the courage to speak to her parents. Her father sits at the head of the table, his brow furrowed as she begins. “John has asked me to marry him,” Akiko says, her voice trembling. Her father sets down his teacup, the room growing silent. “What will people say? A marriage like this ... it will bring shame to our family.” Her mother doesn’t speak, but Akiko sees the tears in her eyes. “I love him,” Akiko insists, but her father’s stern gaze doesn’t waver. “And ... it’s possible now. The government changed the law last year. ” Her father narrows his eyes. “What law?”

Akiko explains hesitantly, recalling what John told her: “The McCarran-Walter Act. Before, women like me couldn’t even get a visa to live in America. Now, it’s different. Japanese women can go, even if they marry someone like John.” Her father’s expression darkens. “You think a law will protect you from the stares? From the whispers? It’s not just about visas, Akiko. You’re leaving everything - your family, your culture, your name. ” Akiko doesn’t reply, but she holds her ground. Despite her parents’ approval, Akiko moves forward. She’s sent to a bride school in a nearby city, part of the U.S. military’s efforts to prepare Japanese brides for life in America.

Akiko arrives at the bride school. The room is filled with young women, each holding their own stories. Some, like Akiko, will move to places far away from any Japanese community. Others plan to settle in places with large Japanese populations, like Hawaii or California. During a break, Akiko meets Yumi, who sits practicing her English with a nervous smile. “Where are you going?” Akiko asks, sitting beside her. “Hawaii,” Yumi replies. “My husband’s family has a sugar plantation there. I’ll have neighbors who speak Japanese. What about you?” “The Midwest,” Akiko says hesitantly. “It’s ... different.” Another bride, Sayaka, joins them. “My husband is Japanese-American. We’re going to Los Angeles. At least I won’t be the only one who looks like me. ”

Akiko listens quietly, realizing for the first time how different her experience might be. She imagines herself as the only Japanese woman in a town full of unfamiliar faces. The bride school lessons are both practical and symbolic. The instructors teach them how to bake American pies, write thank-you notes, and greet their future in-laws. “You are ambassadors of Japan,” one instructor says. “Bring your culture with you, but learn to adapt.” Some brides laugh and joke about their new lives, but Akiko remains quiet. As she folds napkins into the shape of swans, she wonders what her neighbors will think of her, the only Asian woman in a small Midwestern town.

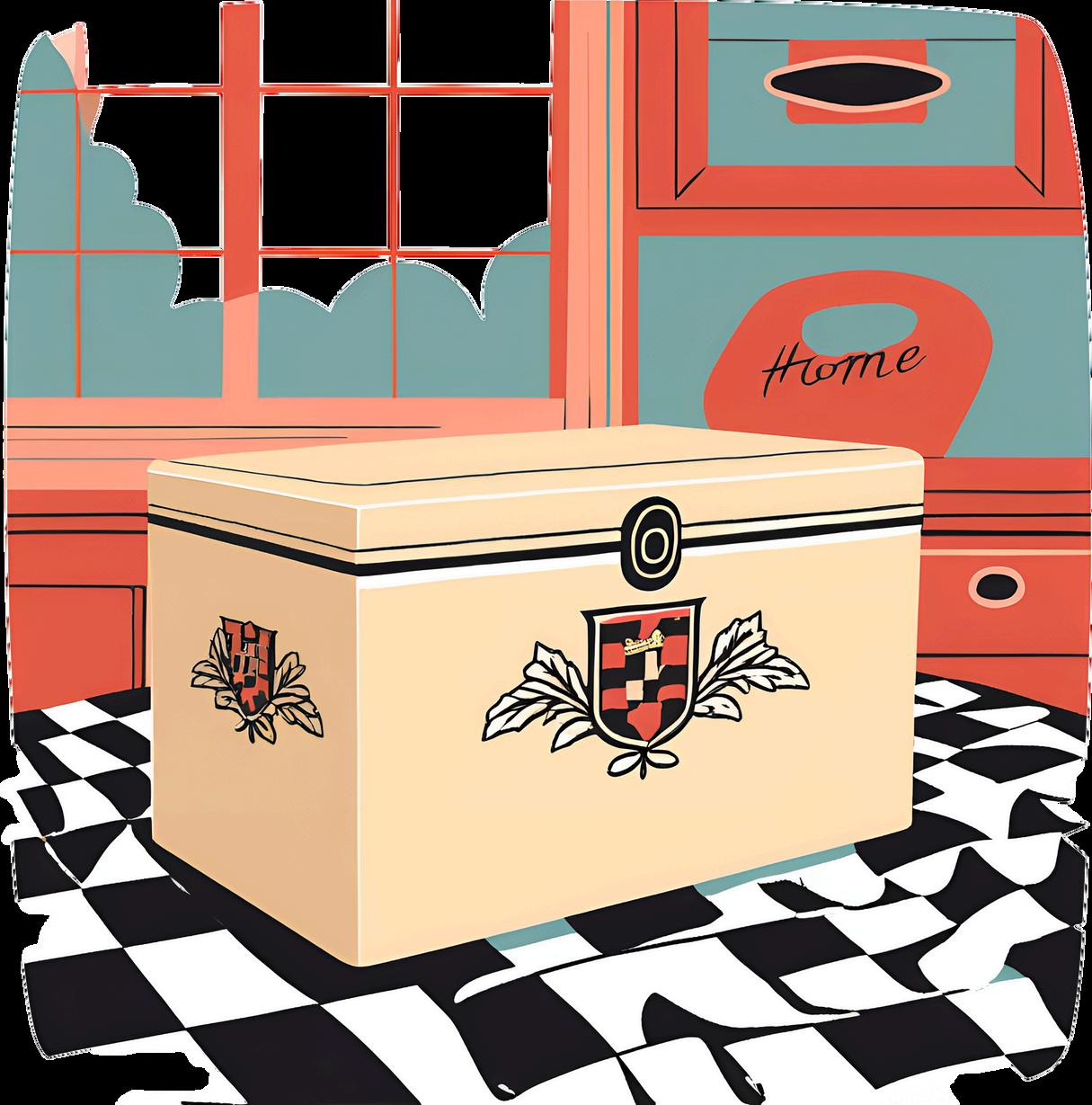

Back at home, Akiko begins to prepare for her wedding. Her mother helps her fold her favorite kimono into a suitcase, her hands trembling. “Here,” her mother says, handing her a small package wrapped in cloth. Inside are handwritten recipes for Akiko’s favorite dishes. “You’ll need these, her mother says softly, finally meeting Akiko’s eyes. Her father remains distant, but as Akiko leaves for the train station, he presses a small lacquered box into her hands. “Take this,” he says. “So you’ll never forget where you come from.” Akiko boards the train into the city, clutching the lacquered box and the recipe bundle. Her reflection in the train window wavers as she whispers to herself,

“This is the beginning of a new life.”

The day of the wedding dawns quietly, with the sky streaked pink and gold. Akiko adjusts the folds of her borrowed white dress in a small room at the church. The lace feels foreign compared to the soft silks of her kimono. Her best friend, Chie, helps with her hair. “You look beautiful,” Chie says, placing a delicate hairpin Akiko’s mother gave her into her bun. “I wish Mama and Papa were here,” Akiko whispers, her voice trembling. “They’ll come around,” Chie says gently. “Give them time.”

When the ceremony begins, the room is quiet, except for the soft murmurs of the officiant. John stands tall in his uniform, his face beaming with pride. Akiko’s hands tremble as she takes his. “I promise to make you happy,” John says, his English words slow but heartfelt. As they exchange vows, Akiko feels a rush of emotions: love, fear, and an overwhelming sense of stepping into the unknown.

After the wedding, Akiko returns to her family’s home to gather her things. Her mother helps her pack silently, her face drawn with sadness. “I don’t agree with this,” her father says, standing in the doorway. “But you are still my daughter. Be strong, Akiko.” Her mother presses a small bundle into her hands. “Open it when you feel far from home,” she says, her voice soft. When Akiko unwraps it later, she finds a piece of calligraphy with the characters for “resilience” and “love,” written by her mother.

A week later, Akiko boards a military transport ship with John. The dock is crowded with other brides and their new husbands, the air filled with the hum of goodbyes and tears. Akiko clutches the lacquered box her father gave her, her fingers tracing the family crest. She watches the shores of Japan fade into the distance, her heart heavy with the weight of what she’s leaving behind - and the hope of what lies ahead. On the ship, she befriends other Japanese war brides. They share stories about their weddings, their families, and their dreams for their new lives. “Do you think it will be like the magazines?” one woman asks. “I don’t know,” Akiko replies honestly. “But we’ll find out together.”

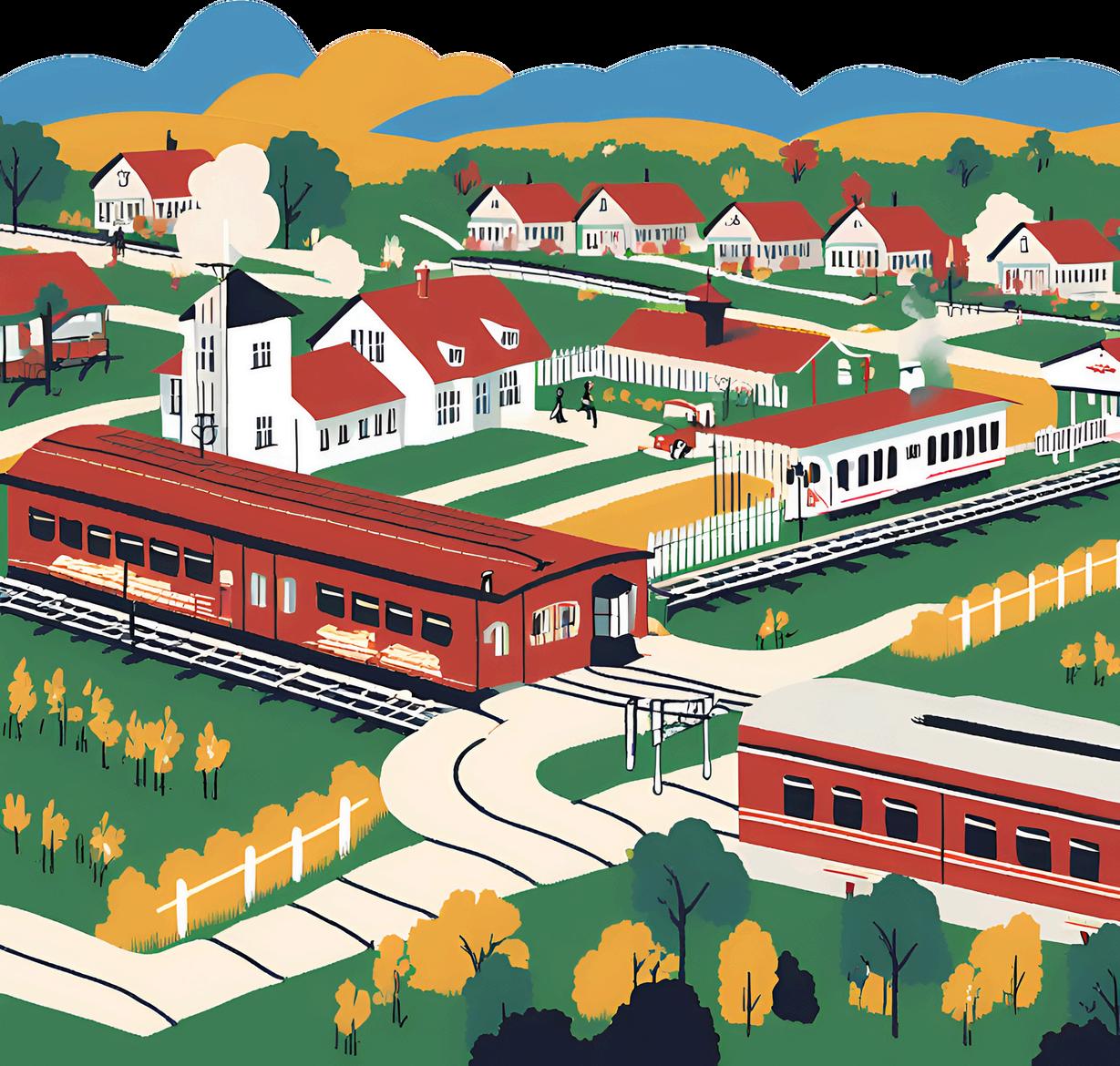

When the ship docks in San Francisco, Akiko is overwhelmed by the sheer size of the city. The buildings stretch to the sky, and the streets buzz with cars and people. “This is home now, ” John says, smiling as he takes her hand. Akiko smiles back, but her stomach churns. She’s unsure if she belongs in this vast, unfamiliar place. Akiko and John board a train bound for the Midwest. Akiko stares out the window at the changing landscape, clutching the lacquered box. “This is my new beginning,” she whispers to herself, uncertain but determined.

Akiko steps off the train, clutching her suitcase in one hand and the lacquered box in the other. The station is small, its wooden platform weathered by the sun. John stands waiting, his face alight with excitement. “Welcome home,” he says, taking her bag. “Is this it?” she whispers, more to herself than to John. “It’s different, I know,” John says, mistaking her hesitation for jet lag.

“You’ll get used to it.”

John’s mother greets them at the house with a tight-lipped smile. She holds out her hand stiffly. “You must be Akiko,” she says, pronouncing the name awkwardly. “Yes,” Akiko replies, bowing slightly before remembering to extend her own hand. “It is nice to meet you. ” John’s mother doesn’t comment on the bow, but her raised eyebrows say enough. At dinner, the silence is heavy. The table is set with mashed potatoes, foods Akiko finds unfamiliar. John’s mother watches her closely. offering platitudes that feel hollow. “We don’t get many ... new people here,” she says. “I hope you’ll find everything to your liking.”

Akiko forces a smile, but she notices how John’s mother exchanges glances with his father. She feels their unspoken disapproval like a weight in the room.

The next day, John takes Akiko into town. She feels the stares before she hears the whispers. “Who’s that?” one woman says loudly enough for Akiko to catch. “That’s John’s wife,” another replies, her tone skeptical. “From Japan, I think.” Akiko clutches John’s arm, her cheeks burning. “Do they not like me?” she asks in a low voice. “They just need time to get used to the idea,” John says. But his words sound unsure.

That evening, Akiko decides to make dinner for John’s family to express her gratitude. She searches the cupboards for rice but finds only a box labeled “Minute Rice.” “This ... is not rice,” she murmurs to herself, but she cooks it anyway. She shapes the rice into onigiri, wrapping each piece with seaweed she brought from Japan. When she places the dish on the table, John’s mother looks at it with open suspicion. “What is it?” she asks. “Rice,” Akiko says simply. “My way. ” John tries a piece and smiles. “It’s good, Mom. Try it.” But John’s mother only takes a small bite, her face carefully neutral. “It’s ... interesting,” she says, setting her chopsticks down.

That night, Akiko sits alone in the kitchen. She pulls out the lacquered box her father gave her and runs her fingers over the family crest. The box reminds her of the meals she shared with her parents, of the rice her mother washed so carefully. She whispers to herself, “This is not home.” But as she places the box back on the shelf, she resolves to make it one.

The next morning, Akiko steps outside to tend a patch of soil behind the house. She plants seeds for daikon radishes and shiso leaves, using the recipes her mother gave her as a guide. “I’ll start here,” she says quietly, watching the sun rise over the fields.

It’s a sunny Sunday afternoon, and John’s family has invited neighbors and friends over for a potluck. Akiko watches from the kitchen as guests arrive, exchanging warm greetings and carrying dishes in glass casseroles. “Akiko, we ’ ve got something special for you, ” John’s mother says, placing a large, chilled bowl on the table. The dish is bright and fluffy, with chunks of pineapple and whipped cream folded into the rice. “It’s called glorified rice,” John’s mother announces proudly. “A Midwestern classic.” Akiko smiles politely and takes a small spoonful, the sweetness and creaminess catching her off guard. “It’s ... different,” she says diplomatically. But in her heart, she knows it’s not the rice she grew up with - the kind her mother washed three times and served simply, steaming and fragrant.

That evening, Akiko decides to make dinner for John’s family, determined to share a piece of her culture. She gathers what ingredients she can find at the local store and uses the soy sauce and seaweed she brought from Japan to make a simple meal of rice balls and miso soup. At the table, John’s mother pokes at the onigiri hesitantly. “What’s inside?” she asks. “Pickled plum,” Akiko replies. “It’s a traditional filling.” John tries one and smiles, “It’s good,” he says, encouraging his parents to try as well. His father takes a bite and nods slowly, but his mother sets hers down after a small nibble. “It’s ... interesting,” she says, echoing Akiko’s earlier words about the glorified rice. Akiko feels a pang of disappointment but reminds herself that sharing food is her way of connecting, even if acceptance is slow.

Over time, Akiko begins to find small ways to introduce her Japanese traditions to the community. She volunteers to cook at church potlucks and school events, using her dishes as a bridge to share her culture. At one event, a neighbor approaches her.

“What’s this?” the woman asks, pointing to a dish of tempura Akiko prepared. “Fried vegetables,” Akiko explains, smiling. “It’s my favorite from home.” The woman tries it and beams. “This is delicious! Will you teach me how to make it?” For the first time,

Akiko feels a glimmer of belonging.

At home, Akiko begins experimenting with recipes to combine Japanese flavors with what’s available in America. She uses canned tuna in her onigiri and substitutes spaghetti for soba noodles, finding ways to blend her traditions with her new life.

One evening, she serves a rice dish with vegetables and soy sauce for John and his parents. She adds a small bowl of glorified rice on the side. “I thought it would be nice to have both,” she says, smiling. John’s mother takes a bite of the Japanese rice and nods. “It’s ,,, not bad,” she admits and Akiko feels a small victory.

As the months pass, Akiko becomes known in the town for her cooking and kindness. She teaches children at the local school how to fold origami cranes and shares Japanese stories during geography lessons. Neighbors begin asking her for her recipes, and soon her small garden is filled with requests for daikon and shiso seeds. “She’s quite resourceful,” John’s mother tells a friend one day, her tone softer than before.

One evening, Akiko watches the sunset over the fields, a plate of blended rice dishes on the table beside her. She feels the lacquered box in her hands, the family crest warm against her fingers. “This is home,” she whispers, knowing she has brought a piece of Japan with her while finding a place in America.

The soft hum of a rice cooker fills the kitchen as Akiko moves with practiced grace, chopping vegetables and stirring a pot of miso soup. Hana, now eight years old, sits at the table, her pencil scratching against a notebook. “Mom, why do you make rice that way?” Hana asks, watching as Akiko rinses the grains with care. Akiko pauses and sits beside her daughter, resting her hand on the lacquered box that now holds recipes from both Japan and the Midwest. “Because it reminds me of where I come from. Did I ever tell you about when I first came here?” Hana shakes her head, her curiosity piqued.

Akiko begins to tell Hana about her early days in the Midwest. She recalls the stares, the whispers, and the struggle to fit in. “But, over time, I found ways to make people understand,” Akiko says. “Do you know how?” Hana shakes her head again.

“Through food,” Akiko replies. “I started bringing dishes like tempura and miso soup to potlucks. People were curious at first, and then they started to ask for more. I even taught origami at the library and showed your classmates how to wear a kimono at school events.” “Did they like it?” Hana asks. “Most of them did,” Akiko says with a smile. “And those who didn’t? Well, they learned to respect it.”

Akiko explains how many Japanese war brides across America made similar impacts in their communities. “Did you know,” she tells Hana, “that women like me helped change how people saw Japan?” After the war, there was a lot of mistrust, but by teaching people about our culture - through food, art, and stories - we helped build friendships between our countries.” Hana listens intently, her eyes wide. “So, you weren’t just my mom. You were, like, a teacher for the whole town?” Akiko laughs. “In a way, yes. And you ’ re part of that story too.” As Akiko finishes telling her story, Hana looks thoughtful. “Mom, do you think I could share this with my class someday? Maybe they’d like to learn about you. ” Akiko smiles, stroking Hana’s hair. “I think that’s a wonderful idea. Our story isn’t just mineit’s yours too.”