HIDDEN WAYS OF COURTING MEMORY

This book was conceived during the Al Mawrid Fellowship and is in direct response to the archive of the Al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art, at the New York University, Abu Dhabi.

I am forever thankful to Salwa Mikdadi for the invitation to engage with the archive, and to the Al Mawrid team for their gracious and patient assistance.

HIDDEN WAYS OF COURTING MEMORY. ©2024 by Cristiana de Marchi

Cristiana de Marchi

Hidden ways of courting memory

The archive was an opaque hope, yet it kept slipping away as though it didn’t want to be found, plundered, excavated.

May 6, 2024. Monday

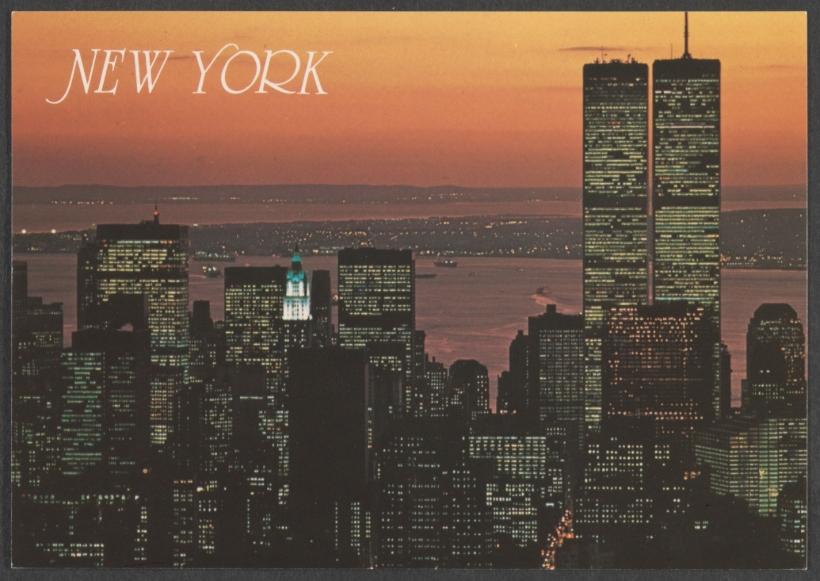

Search: “ITALIAN”

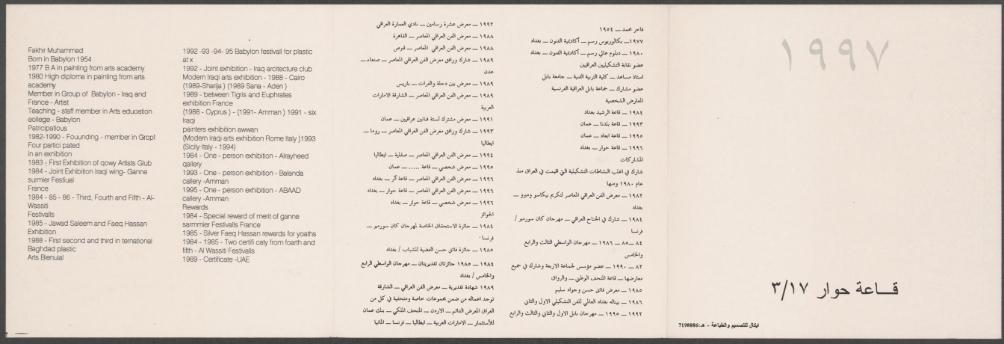

“Fakhir Muhammad born in Babylon 19542”

“Born in Babylon,” inheritance, from a time that borders mythology, more than rooting into history. The Arabic text doesn’t mention the birthplace, only the date, as if omitting the information could result into an advantage, or perhaps simply that information would be acknowledged as granted? In Arabic, Babylon is already Baghdad, when mentioned elsewhere in the text: mythology lingers in the West – the orientalizing gaze, again, a proof, an evidence of it? Or just a presumption?

There are more discrepancies in the translation. English doesn’t mention the location of the art academy: a floating education, and again perhaps the omission is rooted in the persuasion, or in the attempt, to make the artist instantly international. Otherwise, why omitting fragments of his biography?

History is constantly re-written, re-phrased, re-purposed by means of unfaithful additions and attributions, or equally misleading erasures. Inconsistencies, as life keeps throwing at us, or just reminding us of.

2 AD_MC_095_ref205_000001_000002_d.jpg

Mistakes, misspellings, typos, the old fascination for the unwanted slipping into the page, finding a way to settle down. Initially unnoticed, mistakes start popping out progressively: arcitecture, festivalls, yoaths (youth?), certifi caty, foarth (fourth?)...

Each one of them bares a story, or it could, if time allowed. Besides the stories I missed, the mistakes I didn’t capture, not the first time I read it, nor after re-reading this synthetic biography.

Does Arabic, presumably the original version, have mistakes as well? Or must these imperfections be attributed to the translator (an inexperienced translator? Or simply, the rushed translation under the pressure of a printing deadline?). I am not given an answer, nor I actually need one.

“Fadhil El-Ukrufi 1992

“Intifada’s travel”

Copyright Minimal Edition Milano

Litografia”

I google the key words – title and date: information about the various uprisings in Palestine emerge, mostly images, as if the only association we can have to Intifada would be through the news, reported by television at first, and then the internet.

I add “publication”: “A farewell to Arms” pops up, unexpectedly.

“A Farewell to Arms is a novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, set during the Italian campaign of World War I. First published in 1929, it is a first-person account of an American, Frederic Henry, serving as a lieutenant in the ambulance corps of the Italian Army.”

I add “Milano,” and besides views from the city, an interesting paper appears: “The representation of migrants in the Italian press: A study on the Corriere della Sera (1992–2009),” published in the Journal of Language and Politics 12(2), August 2013, by three professors at the Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca: Lorenzo Montali, Paolo Riva, and Alessandra Frigerio.

“The research analyses media discourse on migration in Italy, regarded as a means of reproducing and maintaining a racist interpretation of inter-group relations.”

Finally we are heading somewhere, at least in the uneasiness of associating various forms of repression, in different contexts, historical and geographical. An ongoing process, a never-ending process, simply dislocated, and often just repeated.

Eventually I add “fadhil el-ukrufi,” and at last I get some images from the publication and a pleasant surprise: a copy of an envelope3 addressed to the

Ill.mo Artista

Fadhil el Ukrufi4

at that time residing in Canton Ticino, in Switzerland.

3 https://www.pinterest.com/pin/316870523754595436/

4 In Italian in the text.

: solo exhibition/s

: group exhibitions

: two-person exhibition5 ةعاق : gallery

I build a vocabulary, slowly, and probably adding mistakes to those printed on the old documents I am checking in the archive. Relatively old, to be correct.

Where does it originate, this interest into translation? It has been with me since childhood: translating for the shadows (“the shadow-wows”, “le om-ombre”) first, then as a penitent exercise over old, musk-smelling French and English grammar books that belonged to my mother, at the time when she was a young lady and she was pursuing her education.

But before discovering the very existence of the languages of diplomacy, for many years, learning Greek was my ultimate purpose: all seasons marked by the expectation of a progress, more often by the repetition of the little already acquired, on new grammars brought from Athens during my grandmother’s summer trips. When did we – my sister and I – realize that our grandmother would never be as determined as we were, our desire to learn unmatched by her willingness to teach us her native language?

Greek, the language of a lineage I belong to, un-credited. A lineage that doesn’t stop to my grandgrand parents (in Crete and Athens, respectively, as I was told), but that roots me back into the land of heroes I have grown up with – literature grants me rights I can hardly claim as an individual addressing the State, – an elective family of unshakeable values and terrible vendicativeness. And now, of course, among all, the very one language I miss the most, the Arabic of an ascendence, rather than a descent. So do I move through time, through times. Always with a dictionary, always unable to fully speak or even understand the language. The language of presence – of belonging – as well as the language of a lost country, once that of my ancestors, later that of my descendants.

5 AD_MC_095_ref259_000001_000002_d.jpg

“Fakhir Mohammed

Hassan Abboud

Asim Abdel Ameer

Mohammed Sabri

THE FOUR AL-RIWAQ GALLERY

BAGHDAD 1990”7

I have spent years of my life talking about the “5 UAE”, the group of artists grown around the leading figure Hassan Sharif, and including his brother Hussain, Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim, Abdullah Al Saadi, and Mohammed Kazem.

The denomination came after a show that took place in 2002 at the Ludwig Forum, in Aachen (Germany), and that eventually sealed the configuration and gave some international notoriety to the group.

A group that had multiple rearrangements, always including the core artists Hassan and Hussain Sharif, Mohamed Ahmed and Mohammed Kazem.

A number of shows that took place in the UAE were titled “The Five” and “the Six,” each time with a slightly different configuration, which makes it more difficult today for art historians to determine who was there, and on which occasion.

7 AD_MC_095_ref156_000001_000002_d.jpg

I now come to notice that the Arab world is either affected by a lack of fantasy in titling their shows, or by the attempt to assert the importance of a specific group of artists by using mathematics as a statute of their uniqueness, to establish their limitedness and to enclose their circle.

This was happening in the 1990s, at a time when the Westernized art scenes had had Fluxus and happenings, where the confusion originating from large participations had already – I thought irremediably, but apparently that wasn’t the case, – affected the model of exclusivity that defining a group by their limited number still bears.

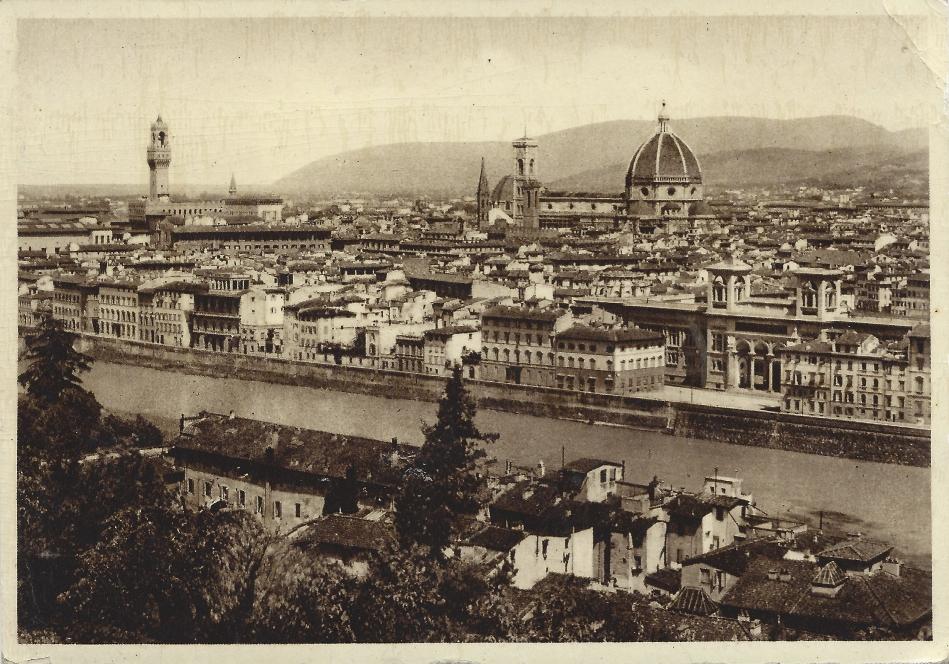

Back of a postcard8, with a long hand-written text, and addressed to a “beloved Jobad and beloved sons,” in Amman – Jordan. no date

the printed text reads:

“FIRENZE

Panorama

Vue générale

General view

Allgemeine Ansicht” (top)

8 The postcard reproduced here illustrates the quality of the image consulted, but it is not issued from the Al Mawrid’s archive, as the photograph referenced in the text belongs to a series of documents that, per al Mawrid's policy and the collection agreements with custodians, cannot be publicly shared (source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/461126449323585828/).

“Veduta della città sulle rive dell’Arno, con predominio del Palazzo della Signoria con la torre di Arnolfo (1289) alta m. 94, del campanile di Giotto (1334) alto m. 81,75, del Duomo con la cupola del Brunelleschi (1434) alta m. 107.” (bottom, in a squared frame) “ediz. Giusti di S. Becocci – Firenze da Fotocolor Kodak Ektachrome” (bottom, underneath the previous text)

“NOVA LUX” (centre top, underneath the Florence Lily) “Riproduzione vietata” (side)

When was the postcard printed? The year is not mentioned, nor as a printed information nor through a hand-written positioning in time. Similar postcards seem to date back to the late 1940s – early 1950s, apparently a time when the word “panorama” would still translate as “Vue générale, General view, Allgemeine Ansicht.” This would sound redundant now, to recur to those paraphrases, in order to explain what a panorama is. The need to explain, to break a language into fragments, and filter them to make them understandable in a different idiom. More often than before, we adopt words from various linguistic horizons, sensing the ability of specific terms to better express a sentiment, a tension, a phenomenon. Purism is relegated to the past, or so I would like to think.

The text in the frame acts as a visitor’s guide to the city, with all the information – synthetically listed – attributing each one of the monuments to their creator, with the year when they were realized and their respective height.

It resembles a Guinness book, this small frame behind a postcard (“Printed in Italy” by “Fotocelere s.r.l. - Milano), with all its records in time and space.

May 7, 2024. Tuesday

exhibition index_copied from the compiled metadata_Exhibition Histories

- 1947, Lebanon,

listed in exhibition catalogue (Mahmoud Hammad collection, ref 30)

- 1948, Lebanon, Beirut, Palais UNESCO

“Exposition des peintres des Pays Arabes”

Mahmoud Said ; [...] = alii not identified?

Group exhibition

May-September 1948

(source) Mahmoud Said. Catalogue raisonné. Volume 2. Drawings. Edited by Valerie Didier Hess and Hussam Rashwan. Milano, Italy: Skira, 2017

1957, Lebanon, Beirut, Palais

Group exhibition

(source) SM – “List of ex Arab Exh. Smikdadi 2006”

Exposition of Contemporary Iraqi Art

- 1961, Lebanon, Beirut

Group exhibition

May-September 1948

(source) listed in exhibition catalogue (Mahmoud Hammad collection, ref 30)

- 1966, Lebanon, Beirut, Gallery One

Carreras Craven “A” Arab Art Exhibition

Solo show (source) Al-Azzawi, Dia, Zainab Bahrani, May Muzaffar and Nada Shabout. Dia Al-Azzawi: a retrospective from 1963 until tomorrow. Cinisello Balsamo (Milano), 2018

Artist’s retrospective’s book

(comment) Cairo, Manama, Kuwait, Baghdad, Amman, Damascus, Beirut, London, Paris, Rome

(venue Arabic name) (source)

May 7 – 9, 2024. Tuesday – Thursday

Search: “BEIRUT”

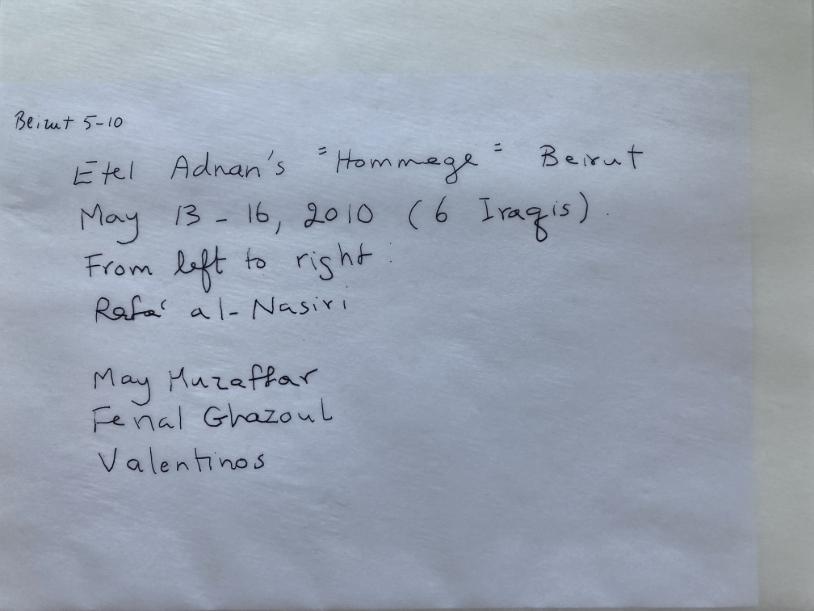

“Beirut 5-10

Etel Adnan’s “Hommage” Beirut

May 13-16, 2010 (6 Iraqis)

From left to right:

Rafa’ al-Nasiri

May Muzaffar

Ferial Ghazoul

Valentinos”9

9 AD_MC_092_ref110_000001_000002_d.jpg

The image reproduced here is the result of a hand tracing based on the original document.

Wijdan, Three Phases... Four Decades

19 December 2002 – 19 February 2003

published by the Khalid Shoman Foundation – Darat Al Funun10

Wijdan is speaking.

A self-reflective text about her artistic practice and how it crosses her biographic experiences:

“This is neither an introduction nor a foreword; it is just putting a few thoughts on paper concerning this exhibition that is not a retrospective, but a brief presentation of the three stages of my artistic development. Before I began my life as an adult, I never imagined I would be so much involved in painting. The reason could be I never take myself seriously. For me painting and drawing are instinctive reactions to whatever disposition I maybe in. [...]

[...]

I have gone through three phases in my artistic development, they are abstract, landscapes and calligraphic. I have lived these phases at times separately and at others blended together. I have been moving between the three styles effortlessly; sometimes working with two simultaneously and at other times concentrating only on one. At times two styles would converge to become one, such as the calligraphic and abstract styles or landscapes and abstraction; at others they would each emerge separately.

[...] On the other hand, whenever I encountered a crises I would immediately revert to calligraphy; somehow I felt that all images fell short of interpreting what I wanted to say and only through words could I express my thoughts. The first time this happened was after the defeat of 1967; suddenly I could no longer use color or build up a composition with forms and lines. Thus I painted my first calligraphic works in black and white with verses from the Qur’an forming part of the visual and graphic composition, in addition to their content. This phase was a short one and it only lasted a few months before I went back to abstract coloured composition, in outburst of paint and light.”

(Amman, 2002: from the Arabic page, the second one, which is missing in English)

From the same catalogue11:

“nominations and Awards: [...]

1992: Nominated for the first annual Montblanc de la Culture Award in Public Assertion. ‘ An award from honored artists to those honorable and honored few who have consistently nurtured the talents of artists, writers, musicians, composers, poets’. The other nominees were: Sir Alex Alexander, the Aga Khan, François Mitterand, Queen Sofia of Spain and Prince of Wales. The honoree was Claude Pompidou for establishing the Centre George Ponpidou12.”

How comes an artist would be in such an aristocratic company, unless a princess herself? Is there a contradiction, an incoherence, a clash of principles? Wijdan’s case might be quite striking, and yet the majority of people ends up to eventually betray their principles. For convenience, most of the time, the convenience of rootedness. Once settling in a place, a context, or a community, the very idea of removing ourselves, by means of refusal of collective beliefs or standards that we might detach from, not embrace, or even overtly refuse, becomes uneasy, uncomfortable.

12 This way in the text, ndr.

Compromises set in, as the necessary condition for not questioning, and for maintaining the ease of our position. Always a temporary position though, regardless of how often we forget, or pretend to.

Who is Sherifa Zuhur? She appears as the only named author/editor in the bibliography of the same publication. Google entries refer to a Saudi scholar specialized in political studies, with a focus on Saudi Arabia. Apparently a homonym...

I am not persistent with my research, this not being my main interest, or rather one that I don’t intend to pursue, to transform into a main one. Sometimes I wish I had a bit more consistency in chasing these traces, as I realize it would be interesting to know, from an academic perspective, the contribution of this Sherifa Zuhur to the art landscape of that time. Ultimately, this is a publication on a pioneering female artist and educator, with some literature about her practice authored by a woman scholar/art critic/writer – whatever applies. And no man mentioned namely.

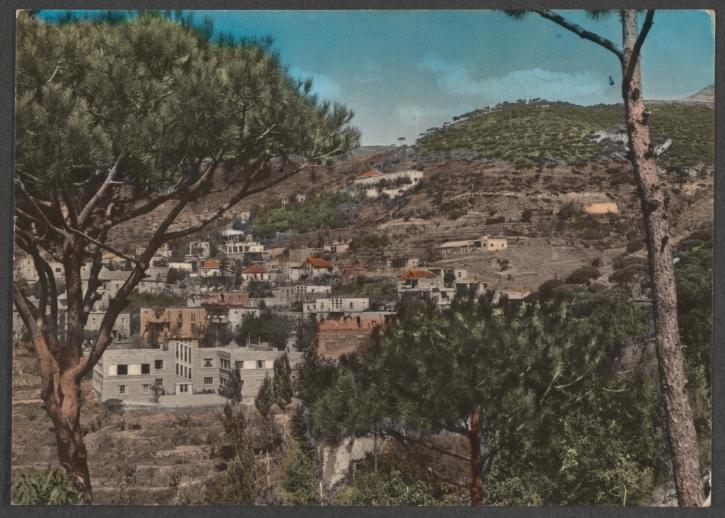

Stamp of the Hotel Berkeley – Beirut, with a hand-written address in Arabic13:

“P.O. Box: 16 5806 Beirut – Lebanon.”

Back of a postcard, with no hand writing, except for a date: // ٢٠٦٥٥ (20/06/55)?

The ٥ has a superimposed ٧ on it.

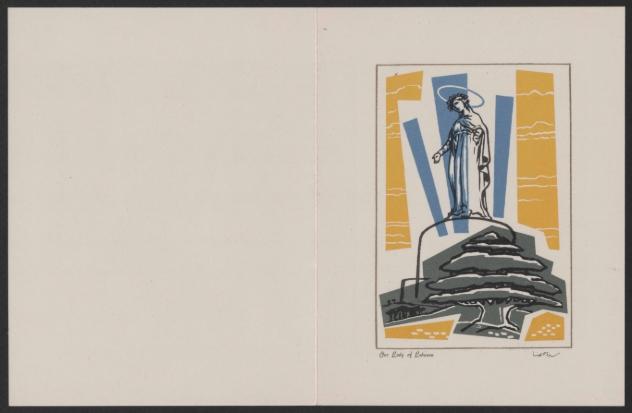

the printed text reads:

“LEBANON – OUR LADY OF LEBANON, HARISSA” (top)

“LIBAN – NOTRE DAME DU LIBAN, HARISSA” (bottom)

510 (bottom, slightly higher than the previous text)

“PHOTO MANOUG – BEIRUT – REPRODUCTION INTERDITE” (side)

The image on the front of the postcard is rendered in black and white: the layout of the Virgin’s statue is traced over with a marking pen, arguably by the artist himself. The only connection to Beirut, the photographic cabinet printing the postcard.

13 The image reproduced here is the result of a hand tracing based on the original document.

Pages from a notebook, with a hand-written text, in a blue pen14 The text reads, in a very uncertain, childish Arabic calligraphy, circled:

followed by:

If my reading is correct, then there is a mistake in the notebook author’s annotation: I could verify it easily, through old calendars. Where was I during those days of November 2011?

14 The image reproduced here is the result of a hand tracing based on the original document.

The convergence with my own biography is striking, as the owner of the notebook reached Beirut on the very same date, November 22 (National day, a day of celebration), when I reached there, 17 years earlier.

That was my first arrival, one that would mark my destiny, unknowingly. How many times did the owner of the notebook come to Beirut before? I keep saying “come” as if I were in Beirut… ---

Pages from the same notebook, with a hand-written text, this time recorded in red ink. The text reads, like before in a very uncertain, childish Arabic calligraphy, circled:

followed by:

Beirut”

The notebook – reference “AD_MC_092_ref125” – consists of 75 scanned pages. Here is a summary and personal report on it.

A hard cover with intaglio and vegetal motives on the four corners. It opens right to left, as expected, although the notebook seems to be a western production, hence supposed to be manipulated in the opposite direction.

[It’s a paperblanks notebook, printed on acid-free sustainable forest paper, and produced in 2007, as I learn later]

The notebook starts with the page from 2010 that is mentioned above: the diary’s first entry dates to October 4, 2010, and is written in Beirut (4 pages).

The notes are written only on the left page, in a neat, lean calligraphy, black ink.

It refers to “Art in America” (presumably, the magazine) and the Tate (less doubts there). A reference to DHL is also present, a shipping either expected or that the author needed to send.

The second entry is the next day October 5, 2010 (also 4 pages) and contains references to “Tracing the Past Drawing the Future”, followed by a reference to Art Asia Pacific. Canon is also mentioned, although it is not clear to me whether this is the photographic brand (as I presume) or the English word for نونق, which wouldn’t make any sense, since the original word is an Arabic one – unless one would want to highlight it in the context of an Arabic text?!

Charles Saatchi is also mentioned, as well as Caribo (the coffee place? With a mistake in the spelling?): perhaps a note about an appointment happening/happened during the day.

The assumptions I am creating, out of nearly nothing, a few deciphered words in the midst of an ocean of unknown words... Could I create a fiction out of it? And if I would submit a similar text and proposition to other readers similarly skilled – or rather un-skilled, – would they fabricate a similar story? Would they end up with a similar narrative resulting from a same set of words?

October 6, 2010 (3 pages)

Here’s a reference to 1969, and again Caribou is mentioned, this time spelled as I write it.

A payment of 10,000 Lira – presumably Lebanese Lira – appears on the last page, a small amount of money in 2010, when the LL was exchanged against the US$ at a fixed rate of 1500 LL = 1US$.

October 7, 2010 (2 pages, the second of which continues with the following day)

Here the reference is to a much bigger amount of money, quantified in 15,000 US$. It seems like he had lunch at a restaurant called “Bread”, and spent 80 US$: an account of the mundane, the daily expenditures, besides the annotations on exhibitions and art publications.

October 8, 2010

A mention to “Buter [Butter?, ndr] and Mint”, perhaps again a restaurant – but after “Bread,” that would be hilarious.

The next page contains a note that seems taken from an older magazine, as the date 1959 appears here.

The notebook then continues with another “emblem” for a new رتفد, dated 13-17.12.2010 and it contains only a line, dated 13.12.2010, in brackets. Did he keep a journal only while traveling?

The next emblem, almost shaped as a “coat-of-arms” is dated 27.12.2010, and it’s followed by an entry dated 28.12.2010, that starts with:

“sweet home 97317710334”

The place seems to be Al Manama, if I am not mistaken. Why marking one’s own phone number on the notebook, after reaching back home? Or perhaps he got a new house and therefore a new phone number? Or it could simply respond to the common habit of adding one’s own references, with the expectation of someone returning the notebook, in case of loss.

He writes every day, in fact, in a structured way, as it seems: to remember things, to put them in order, to reflect on them, to simply preserve them for his immediate future and – was he intentionally thinking of this? – for posterity.

On December 30, 2010, he mentions Art Bahrain, the gallery as it seems, not an art fair.

The page marked with the sequential number 30 contains a funny association of Arabic and English to name Manama, on January 1st, 2011.

The place and date are first mentioned in Arabic, followed by a brief note and then are repeated in English, followed by a slightly longer note.

He notes about restaurants quite a lot: on January 4, 2011 there is a mention of “The Steak House.”

Daily entries continue until January 16, 2011, with the usual accuracy in writing, almost without mistakes or corrections, always in a black ink pen.

The January 17, 2011 entry consists of a paper clipping from the “Gulf Daily News,” portraying the opening of an exhibition at Al Riwaq Art Space.

The paper clipping is cut in a way to show a picture with, presumably, dignitaries and artists attending the opening, but the mention of the artists showcased in the exhibition remains not visible.

Tarek’s birthday, one that I keep celebrating, although I wasn’t aware of the recurrence at the time... Again the emblem to mark a travel. Again Beirut, June 2011.

On June 7, he writes a note where two hotel room numbers are mentioned: room no. 702 and room no. 706.

Here again I am tempted to fantasize: about a change of room, due to some sort of dissatisfaction of the artist about specific features of the first room assigned to him. Or perhaps this is a reference to the room of a friend, in addition to his one?

The Pet[it, ndr] café is also mentioned on the same page. It looks like he was staying in Hamra, perhaps at the Hotel Cavalier where he seemed to be an habitué, and where I first landed as well, a piece of history in any case.

Annotations of expenses are again present: 10,000 LL and 50 US$

Dated June 8, 2011, this entry adds colors to the usual monochrome tone of the page. Three lines are in red (red was also used in previous pages from the same trip, to underline and highlight segments of the texts).

The date bears a mistake and its correction: the date is initially written as June 8, 2001, then corrected into June 8, 2011.

Those two days are almost exactly the frame of my failed marriage: the first anniversary and the first missed one, as we were already – since a few months, – separated.

While on June 8, 2001 I was living in Beirut, pregnant with my first child, in a state of absolute bliss, on June 8, 2011 I was in Dubai (or perhaps Basel?), awaiting the month of July when I would

be entitled to see my children (two, at the time), whom my now ex-husband had abducted and kept in Lebanon.

The journal here doesn’t seem to carry that much drama, with its annotations of breakfasts and other touristic pleasanteries.

The red “marque-page” ribbon is fixed here, and I couldn’t be more agreeable about this being just the perfect page to be marked.

The last entry is on June 9, 2011, with an annotation of the taxi company Queen Taxi [here spelled Qween Taxi, ndr].

The name sounds familiar, and certainly it is, with the million taxis I took while in Beirut, before I was brave enough to drive there (1994-2003), and after returning to town in 2011. But I like to think that this was the company that used to take customers over the Syrian border, mostly to Damascus, an occurrence which is possible, since there is also a mention of an expenditure of 100,000 LL, which could be the right amount for one seat in a car occupied by multiple customers, a “service” – or rather “servís”, as we would call it in Lebanon.

The restaurant Barbar is also mentioned: the first time in Arabic as ربربمعطم , the second one in English, as: “Never Barbar.”

Apparently he didn’t like their service!

The next day June 10, 2011 there is a mention of AUB, where he presumably had appointment with two doctors – I guess PhD doctors, not medical ones.

The last day, June 11, 2011 he annotates two expenses, respectively of 880 US$ and 30 US$.

The next emblem in the notebook, referring to the November 2011 trip to Beirut, where he was staying at the Hotel Cavalier, room no 702.

The opening of the exhibition “Art in Iraq Today” seems to be the occasion for this travel. The usual expenditure annotations are present, as well as one of the ABC shopping mall.

The next emblem in the notebook, structured in the same way, a poor calligraphic solution,

2012 refers to another trip to Beirut, in the summer of 2012, betweeen July 7 and 12.

The first entry, dated 7.07.2012, besides the regular accountant annotations, mentions in two consecutive lines the magazine “Art Review” and “Art Auction,” perhaps the magazine “Art+Auction,” or an actual art auction.

Towards the end of the page, there is also a reference to the Beirut Art Fair.

In fact the 2012 edition took place between July 5 and 8. He clearly didn’t come/go to Beirut for that purpose only, as the dates don’t coincide, especially as he missed the official opening and was there only during the last days of the event.

The subtitle was “ME.NA.SA.,” a sort of compromise between a unified vision of the three regions – Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, – and the acknowledgment of an actual separation occurring and persisting between three characterized geographies, and that regardless of any cultural and political attempt to overcome those distinctions.

Punctuation is a vehicle to confirm individualities beyond any prospect of forced harmony. The very punctuation that is generally mistreated during our school years, little understood, overlooked, disregarded. But those are the pauses, the suspensions – shorter or longer, – the intonations that make the written word breath, expand and slow down, that give life to the written word, otherwise condemned to the platitude of silence, or to the monotony of arhythmy.

Open paragraph

open quotation marks

interrogation mark

close quotation marks

comma

open quotation marks period period period

close quotation marks15

The next day, a mention of the ABC shopping mall again – apparently these trips to Beirut were also an occasion for shopping, unless I misread the intention (certainly I do misread the text, and forge my own interpretation, forcing the text to tell a story, a story of de-contracted flânerie in Beirut, at a time when Beirut was still enjoyable, before its collapse in 2019).

On the same day, another stop at the Petit Café – here spelled “Petet Café”: it is surprising that one would be accurate about accents and then miss the spelling of easier words. It looks like he studied some French, and could remark and notice, and then correctly reproduce, some accented words (perhaps due to the teachings of a demanding teacher?), but then – like we all tend to do –he would miss on easier words, where insistence – and consequently attention – would be less acute.

9.07.2012

“Cutting Edges

Contemporary Collage” opens the notes for the day: it could be an exhibition, but the word ضرعم doesn’t appear anywhere near.

The following two days show entries with no english words, and they are followed by two empty pages. No entry for the last day of the trip: perhaps he left early morning and there was no time to either do something in Beirut or to annotate it.

15 The poem here – “Elisions” – is my own, based on and homage to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2022). Restored edition (originally published in 1982 by Tanam Press).

The last page of the booklet is written in English, all capitalized, and it contains bank coordinates, a P.O. Box address in Amman, three phone numbers: home, studio, and mobile, and the following

RAFA KAMIL ABDULBAKI AL NASIRI

G1979996 BAGHDAD

17.05.2008 -> 16.05.2016

MAY A. MUZAFFAR A. AL KHALIDI

G1979813 BAGHDAD

15.05.2008 -> 14.05.2016

What are these 8 year windows? Almost coinciding and yet not exactly?

The last date, May 14, 2016, was my father’s birthday, one of his last ones. I certainly missed it, since I was never around during the spring, but I also certainly called him to wish him happy birthday.

Probably that was one of our uncomfortable exchanges: it has always been difficult to talk to my father. He was pretending, or impersonating the character of the unshakeable male figure, perennially dissatisfied with the lives of his children, their experiences scrutinized and dissected only in order to be trashed as failures.

Calling him, specifically him, was never an easy decision: I was always counting and hoping for my mother’s presence or intrusion, to relax the conversation, to make it bearable.

And yet it was my father I would reach out to, if I had a pressing question, if I felt stuck and I needed to hear a word that would help me to resolve my incertitude. And it was my father I would feel more attuned to, as it comes to a certain orientation in life – not the values, perhaps, many of which we didn’t share, – but a way of living one’s life that does not glorify duty and sacrifice, but rather is open to the laziness of a contemplative approach.

After several days, and after finding another similar annotation, I infer that those could be the issuing and expiring dates of his and his wife’s passports: how caring to keep them both marked on his notebook, as if one wouldn’t want to risk to travel alone, to leave the other “half” behind.

“Etel Adnan’s “Hommage” Beirut May 13-16, 2010

From left to right: May Muzaffar

‘Isa Makhlouf

‘Abbas Beydoun”

The 4 characters (one unidentified) are shown on a stage, sitting behind a table: a theatre setting, like I have experienced several times in Lebanon, and then in other countries around the 1990s and early 2000s – things have changed later, a de-contracted model has become ubiquitous, chairs, sofa and even carpets have made it to the stage to host the guests in a more hospitable way, – when I happened to attend official ceremonies, seminars, and colloquia, always with the heavy drape falling on the front side of the table, to hide the legs of the participants, and perhaps also the quality of the table’s legs: a solution to dignify and elevate the event, to turn it away from the ordinary nature of the ministerial furniture.

As I am sitting in the archive, M.Y. is announced: he is accompanying the daughter of a 1960s woman educator, who had a relevant role in women’s art education’s development in the UAE. The lady is now in her eighties, as Salwa mentions, and affected by a devastating dementia. I think of estates, of what we do inherit, of what we leave behind, for our children to inherit. The places they might have to visit, the people they might have to meet, willingly or less willingly, in order to perpetuate their parents’ outreach in history. Unless these children of ours are not going to accept the legacy. Then it will be oblivion, another form of derangement, of interruption.

The lady arrives with a large cake, which is accommodated on the table next to my provisory station, and soon leaves the room in order to tour the facilities.

Salwa’s assistant takes a look at the cake: a soft one, needing plates and spoons to be tasted. But there are no plates nor spoons. They thought, while choosing the cake, of a different setting. They probably thought of a mansion, with servitude ready to promptly and efficiently take the cake to the kitchen, where they would be instructed to arrange the needed.

The assistant reluctantly serves the role: she does it far more graciously than I would do, culturally trained to manifest patience and hospitality in all circumstances. I acquired those skills too late in life, and never perfected them.

I leave before they come back from their tour: I certainly want to avoid eating a creamy cake in a paper plate resting on my knees – the uncomfortable setting of openings and post-talks buffets, –smiling at whatever is said, regardless of my level of understanding, or my intention to.

It has been a good morning: the directory “Beirut” has brought me a few entries, the back of two photos portraying artists friends gathering at one of Etel Adnan’s exhibitions in Beirut; a notebook with childish Arabic texts, a clear joyful commemoration of the artist’s permanence in the Lebanese capital (but what else did he write in his notebook?), a postcard of Harissa, with only a date written on the back. Traces, nothing more than that. Traces to follow and to take me back to my beloved Beirut. The longest love of my life, at this point.

Am I a too easy-to-satisfy collector?

Back of a postcard, with no hand writing, except for a date: // ٢٠٦٥٥ (20/06/55)? The number ٥ has a superimposed ٧ on it.

The printed text reads:

“1179 – Lebanon – Harissa Our Lady of Lebanon”

“Liban – Harissa - Notre Dame du Liban” (top)

“Photo Sport - Bab Edriss - Souk Seyour - Beyrouth” (side) this printing is very faded and it looks to have been over-typed

The image on the front of the postcard is magnetic: the statue of the Virgin is rendered in an almost fluorescent way, as if invested of a divine light. The brightness of the colors is supernatural. Not bad for a cheap-print postcard, that illusion of “Divine Intervention”!

Back of a postcard, with no hand writing, except for a date: // ٢٠٦٩٥٩ (20/06/959)

The printed text reads:

“Lebanon – Harissa Our Lady of Lebanon” (top)

“Photo Sport - Bab Edriss - Souk Seyour - Beyrouth” (side) this printing is slightly faded and it looks to have been typed

The front image is a photograph in black and white taken from afar and with a cactus in the forefront.

It reads “Liban – Harissa – Notre Dame du Liban,” written in a primary school calligraphy [funny how,] the back bears the English version of the text reproduced on the front.

A paper clipping16 published in Visting Arts Number 37, Summer 1998, features the exhibition “Strokes of Genius”, curated by Maysaloun Faraj.

I encountered some of the artists ‘ works while I was living in Beirut, and I bought one of the few artworks I ever bought, a small bronze sculpture reproducing three ascending birds by Monkith Saeed. I was fiancée and about to get married at the time, and I had this now-weird fantasy of turning myself into an art collector: the first piece I wanted to buy for our new house was an artwork. Full stop. That was clear to me. I didn’t want to buy a piece of furniture or porcelain before choosing an artwork to start “dressing” the apartment. It was the year 2000 and I thought I was late in discovering these artists – I have this obsession of being late to everything in life, to any experience others might have had much earlier than me; and, of being slow in processing experiences. In fact, this was the very same year when the exhibition was touring UK, almost coinciding with my wedding, the late spring of the year 2000.

I later acquired the resulting publication, of the same title, a book that I cherish because of the memories it bears, of a positive, open look over the future.

It is bizarre to read these lines from the review now:

“Today, the image of Iraq is tainted, its contributions to world civilization apparently forgotten. [...] Strokes of Genius is an exhibition that acknowledges the best of contemporary Iraqi art as an integral part of world art and aims to challenge some of the misconceptions and stereotypes created by recent political events. This project was started with the ultimate aim of producing a book on contemporary Iraqi art.

16 AD_MC_095_ref368_000003_000002_d.jpg. The document could not be reproduced in the context of this publication. The catalogue’s cover reproduced here is part of my personal archive.

A folded card, printed on good quality paper – the kind of paper that invites to trace lines with a fountain pen, – one of those cards that were used to send wishes, or in a Western context, to request the pleasure of someone’s company, mostly at a religious ceremony.

On the outside, the front page reproduces a painting – a lithograph, or a silkscreen – of “Our Lady of Lebanon”, in light blue and yellow, on top of a cedar reproduced in a grayish green17 .

Inside the pages are blank18

of

Two pages from a catalogue that looks like a phone directory20

The two pages focus on artists from Palestine. Interesting for the selection of titles.

The pages are from a publication titled Baghdad international festival of art 1988.

On the first page of the publication, acting as a catalogue with no images, hence rather an index, the three languages – Arabic, English, and French, – in which the title is repeated appear in the following way:

BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF ART

festival international des arts plastiques de bagdad

1988

The first page ٣ is dedicated to Iraqi artists working with ceramics –

Among the interesting titles – still thinking of working on a translation of key words, – I notice:

Shape

the black magic

a readable letter

a desert

Resemblance of desert and magic, as a sound – to the inexpert ear, of course.

After the Iraqi ceramists, Egyptian artists are listed. While for the Iraqi, only the name and the title are provided, for the foreigners dimensions and media of the work are also mentioned.

The countries on this page are:

SAUDI ARABIA

the three charming girls

SOVIET UNION

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

auspice

attempt at definitions ones moments

CYPRUS

departure

G.F.R.

object

KUWAIT

inner wounds

looking back

U.A.E, erroneously spelled U.A.R.

the artists listed are: Isam Shraida, Abdul Rahim Salim, Abeer Serour, and Mohammed Yousif Ali

picture

without

the absence tea

longing

BULGARIA

returning way

conversation in the garden

godliness

PERU

BAKISTAN21 self

CYPRUS in search for meaning of life and freedom

G.D.R.

the living one

SCHICOSLOVAKIA22 MOROCCO

21 This way in the text, ndr. 22 This way in the text, ndr.

MOROCCO

IRELAND painting

U.K.

untitled

MALAYSIA

YAMAN

SAUDI ARABIA

I find my way through this page. Lebanon is not mentioned in capitalized English, like all other entries, but I recognize the name of Paul Guiragossian, which cannot possibly be listed under Malaysia. Lebanon is mentioned only in Arabic, [almost] as if it had been added “a posteriori”, while tardily noticing the omission. But the curious thing is that, for some reason, they didn’t add the English version of the name. I first think that they had the name of the country added in Arabic instead of English, but then I start looking back again at the other entries and I notice that all of them present a capitalized English and an Arabic version – much thinner, and since it cannot be capitalized, one that tends to disappear on the line – of the country name. Experiences need to be repeated twice, in order to be fully appreciated, to be fully experienced.

TUNISIA

A poem to the motherland

U.S.A.

PALESTINE

Where to for the third time

The title is beautiful, poetic to the core, touching with its simple and yet profound formulation, bearing a sense of despair but at the same time of dignity. The artist of this oil painting (76 x 101 cm) is Ismail Shamout, a leading figure in modern Palestinian art (see biography in folder).

Vanishing sex

PORTUGAL etching

BAHRAIN

PHILIPIN the body

longing for justice and peace

a touch of yellow

QATAR letter structure

Hellenic space

Untitled is here translated differently from before: I need to check if both translations are currently accepted, or one is preferred over the other. I get the sense that the vocabulary has changed from

the time this book was published, and that nowadays – besides the fact that most art literature is written in English, – the terminology has also set somehow differently.

VENEZUELA

G.F.R.

there is nothing left but fading in your shadow

time for waiting

tension in a box

horizon

to remove black

to remove white

melancholy

All these many years, I never realized the connection between Arabic and Portuguese, and actually the Arabic root to the word “Saudade”. Saudade is literally the black mood, which is a translation from the Greek. But what is the concatenation?

“Melancholia or melancholy (from Greek: µέλαινα

melaina chole, meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval, and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly depressed mood, bodily complaints, and sometimes hallucinations and delusions 23”

I thought melancholy, as we now intend it, not to be an ancient feeling, or rather to be but to have been named later in history. Like other feelings, the full set of discomforts we used to feel for being trapped into gridded structures of various nature, un-evadable because unnamed – what would I give to have had those words back then, and reclaimed my strangeness from the standpoint of an affiliation to a like-minded group, instead of always against, always alone.

Those feelings only lacked a name, to be claimed in their full dignity, to be recognized, to be acknowledged: it took decades until the moment they found their way through words, until the moment they were verbalised. 23 Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melancholia , accessed on May 25th, 2024.

Like “Moral Injury,” perhaps one of the last additions, or at least one I discovered recently, as I am trying to make sense – since many months, now – of a sense of moral disintegration, of an emotional disaggregation, of an ethical disassociation.

“Moral injury is the damage done to one’s conscience – to the soul of the individual – when that person witnesses, fails to prevent, or perpetrates acts of violence, injustice, cruelty, or suffering that they are unable to prevent, and which clash with their sense of right and wrong.

The psychological impact might include ongoing distress and a profound questioning of moral beliefs, societal norms, and one’s sense of efficacy in the world.24”

Words creating worlds, the possibility for worlds to exist being based on their naming, on the very existence of a name to refer to them, to acknowledge them.

24 I am grateful and I like to thank May Al Dabbagh for bringing this to my attention: the ability to name the feeling offered me a momentary sense of relief.

broken memory

continues listing of Iraqi artists

(this one translates as “contemporary”)

(“shattered” rather than broken)

cloth / canvas

May 10, 2024. Friday

Search: “ABSENCE”

There are a few entries only, under the voice “absence.”

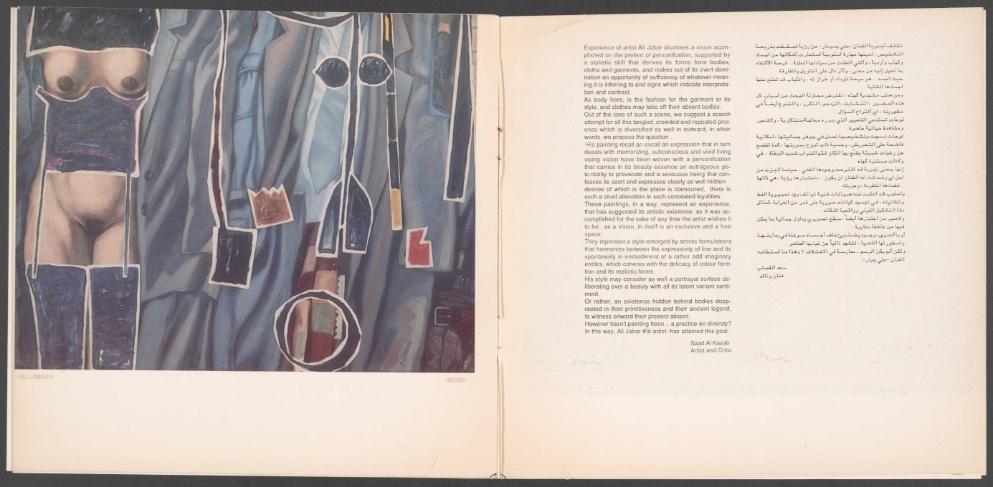

The first one is a text about an audacious painting by artist Ali Jabbar25. Underneath the reproduction of the painting, its dimensions (100×80 cm) are mentioned, but not the title.

The accompanying text, in English and Arabic, is written by Saad Al Kasab, an artist himself and critic, and is published in Baghdad Group, a catalogue whose publishing coordinates are not mentioned.

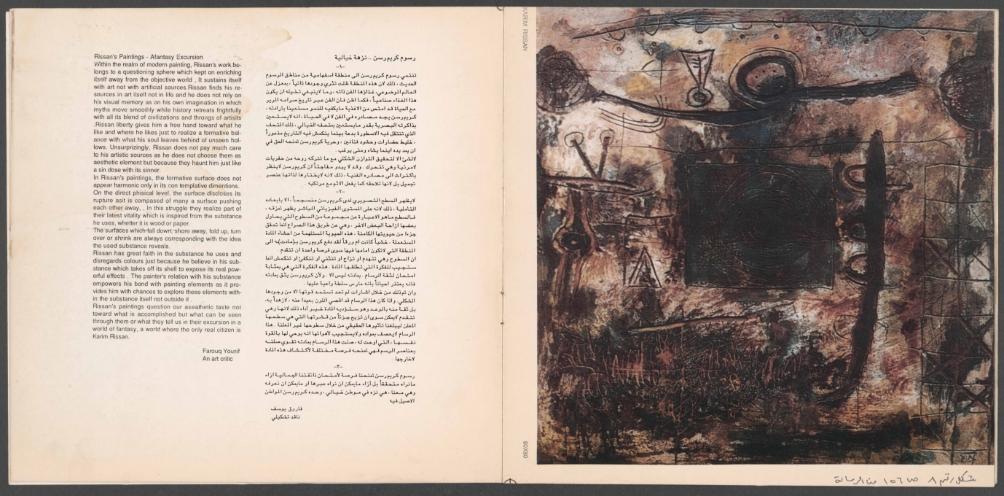

The group consists of 4 artists, namely: Ali Jabbar, Mahmud Al-Obaidi, Karim Rissan, and Haithem Hassen.

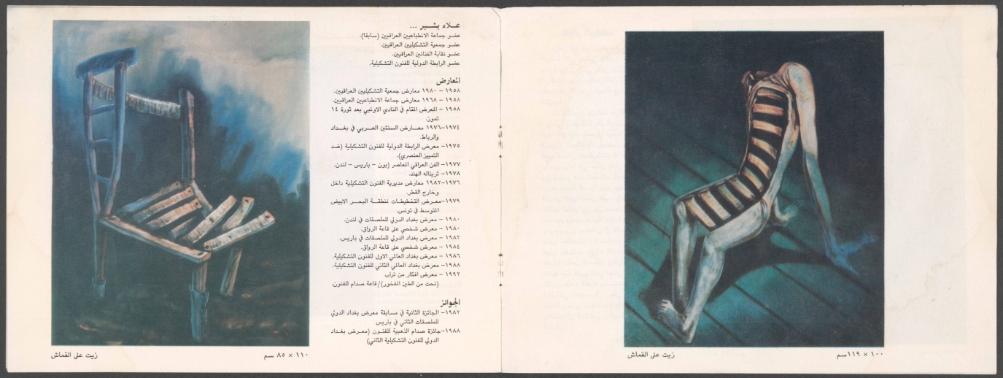

The painting by Jabbar (see image) reproduces a series of male garments occupying the three quarters of the canvas, while on the left of it a feminine nude is presented frontally. The nude is partially covered in a collage technique with clearly superimposed and roughly painted pieces of clothes, including a corset, tights with suspenders, and a bib. These clothes aptly cover the parts of the body that are not eroticized, while revealing and even emphasizing the sexual traits of the physionomy.

In the accompanying text, we can read the following mentions of absence:

“As body here, is the fashion for the garment of its style, and clothes may take off their absent bodies.”

A sentence that doesn’t mean much in English, which is probably resulting from a poor translation from Arabic.

“Or rather, an existence hidden behind bodies deep-rooted in their primitiveness and their ancient legend, to witness onward their present absent.”

25 AD_MC_095_ref188_000001_000009_d.

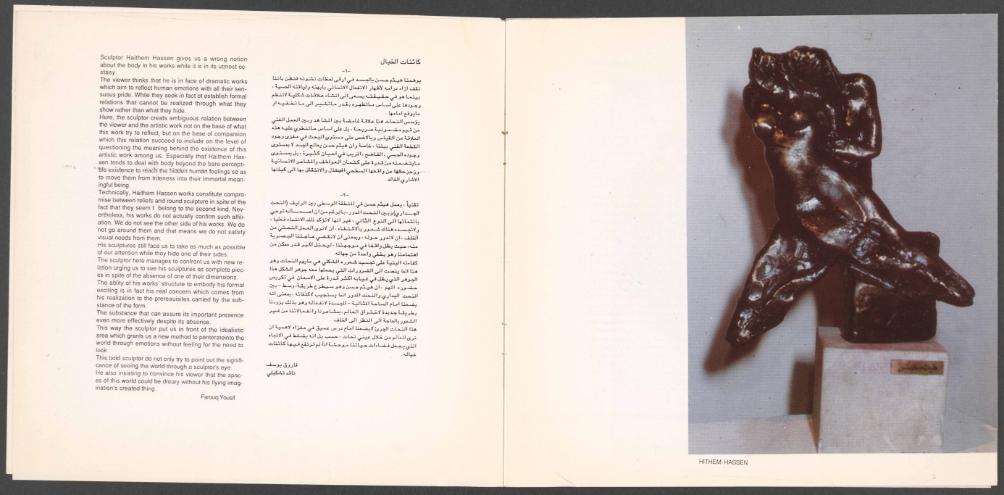

The second document (from the same publication) is the comment to a sculpture by Haithem Hassen, written by art critic Farouq Yousif26. The title of the sculpture is not mentioned in English, but the Arabic version of the text bears the following line on the top of the page:

The text reads: “The sculptor here manages to confront us with new relation urging us to see his sculptures as complete pieces in spite of the absence of one of their dimensions.”

and continues:

“The substance that can assure its important presence even more effectively despite its absence.”

which is another obscure sentence, as it revolves around the same concepts without resolving them, without freeing the thoughts from the circularity of repetition.

The next entry is from the catalogue of the 1988 Baghdad Art Fair, pages 7 and 9.

Page 7 mentions the artwork The Absence Tea, by Algerian artist Rashid Koraishi, an acrylic painting measuring 55×70 cm.

On the same page though, connecting to the idea of absence, another series of works are mentioned: U.A.E. Mohammed Yousif Ali’s Without, three works with the same title, two of which are described as mixed media (respectively 88 x 73 cm, and 77 x 95 cm), while the third one is a fiber glass sculpture (75 cm, probably the height).

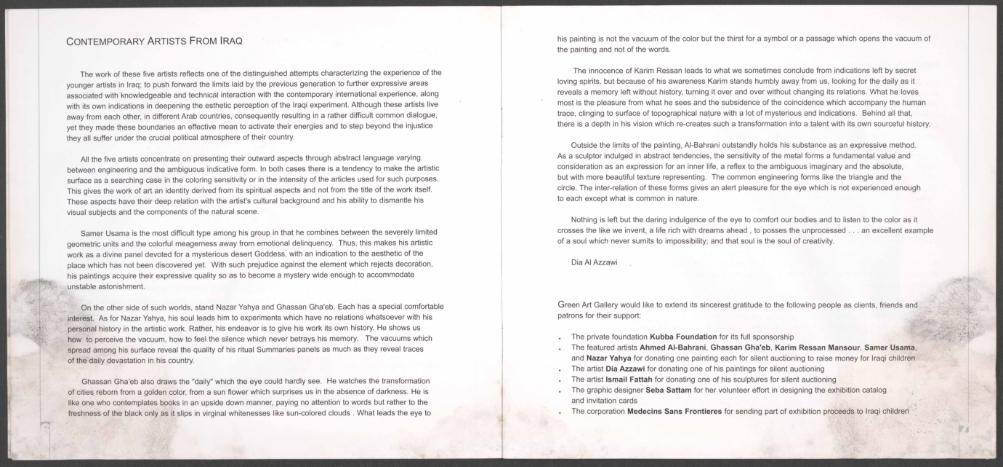

The next entry is an introduction to an exhibition titled “Contemporary Artists from Iraq,” featuring Ahmed Al-Bahrani, Ghassan Gha’eb, Karim Mansour, Samer Usama, and Nazar Yahya, held at Green Art Gallery, Dubai (June 4 – 22, 2003), published in the accompanying catalogue and authored by Dia Al Azzawi27

A reference to absence, although indirect appears on the first page of the document (in English), where he is referring to the work of Nazar Yahya, as it follows: “He shows us how to perceive the vacuum, how to feel the silence which never betrays his memory. The vacuums which spread

27 AD_MC_095_ref278_000001_000004_d

among his surface reveal the quality of his ritual Summaries panels as much as they reveal traces of the daily devastation in his country.”

But it’s the following paragraph, about Ghassan Gha’eb, where a direct reference to absence is contained.

“He watches the transformation of cities reborn from a golden color, from a sun flower which surprises us in the absence of darkness.”

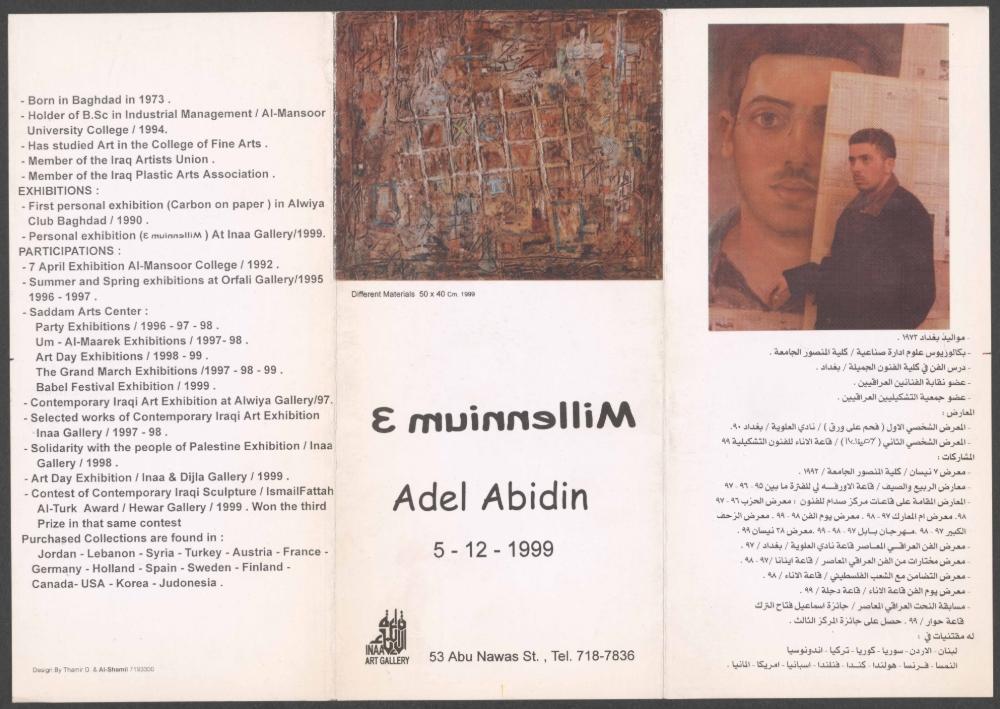

The last entry is from the brochure published on the occasion of Adel Abidin’s 1999 show titled “Millennium 3,” at Inaa Art Gallery (in Baghdad)28, seen above.

The text is written by Noori Al-Rawi, clearly in Arabic with a terrible english translation. The specific passage with the mention of absence reads as follows:

“An inwardly devoted attachment in Adel Abidin’s works makes us constantly expect un unknown renaissance something invisible, a presence whose boundaries we cannot grope A fascinating absence with a surprising momentarily appearance from behind those random hidden lines which are woven with silence and obscurity.29”

28 AD_MC_095_ref222_000001_000002_d. See here, page 25.

29 The misspellings, punctuation and lack of thereof are in the text, ndr.

May 13, 2024. Monday

Search: “BLACK”

A folding card, printed on good quality paper, similar to – and apparently from the same series of, – those found earlier.

On the outside, the front page reproduces a painting – a lithograph, or a silkscreen – of a black woman’s head and neck, with jewelry and surrounded by moons and stars, a clear reference to a night environment.

The Arabic text printed on the bottom of the drawing is translated underneath as: « “My nights are black brides wearing necklaces of pearls” ... ,» which seems to be a quote of a line from a poem.

A notebook, with a marbled hard cover. The first pages are empty.

Apparently the scanning was done in reverse: I am then moving backwards, starting at the end of the notebook and progressing toward its beginning.

000108

The date is / ١١١١, the year being less readable. November 11, my birthday, possibly one that I have lived, not my birth date antecedent to my birth.

Other earlier entries from the same year, 1979: it is now acknowledged. I was a child at the time, with no connection to the art world. That November 11, 1979, I did celebrate, probably at home, with a few school friends and a home-made cake.

The writing is minuscule, traced in a very light blue ink, with mistakes and erasures. Unequal is also the way in which the dates are marked: sometimes the full year ١٩٧٩, sometimes only ٩٧٩. The annotations are sparse, infrequent: once a month, although July of the same year seems to be a busy month – a memorable one? - if I am to believe (I don’t venture into the Arabic text) that the artist writes only on occasions.

There is this fundamental difference, in journaling: the memorable versus the everyday annotation. Writing only when something deemed important happens, in order to preserve its memory, or perhaps to help reflecting on the implications of such an event; or writing as an exercise, on a daily, or semi-daily, basis, hence fixing on paper the mundane, or otherwise the thoughts that it solicites.

000098

A sketch, dated // ١٩٧٩٢٦, a really primitive sketch, a stamp-size sketch, in what doesn’t seem to be a sketchbook, but a diary.

Another one is dated // ١٩٨٨٨١٣, a black ink doodle – French says it better, though the word gribouillage suggesting a roundness, a convolutedness, the intricacy of unresolved sequences, the many returns to a space where solution has never been the purpose, – on the top left of the page (the rest of the page is written in the usual light blue ink).

A symbol goes under the date // ١٩٨٨٧٢١, resembling a compass needle pointing North [?].

The booklet contains several paper clippings and sparse papers with annotations.

There is a picture of the notebook especially charged with symbolism: a small paper emerging from top, with the word “mirror” handwritten on it. This whole search throughout the archive has turned to be a mirrored experience…

Starting from scan 000067, there are a series of pages with linguistic annotations: the artist seemed to be learning, or perfecting, their English: the words listed here are the following:

“Collage Relief

Assemblage

Art Deco Fauve

Fauvism30 modern modernism modernize modest mood

Post modernism modernity

avant-gard 31

Post-Painterly Abstraction

Matif” The following pages contain yet another list of words, with their corresponding Arabic, but unrelated to the art vocabulary. They could be annotations taken during a language class, as well as a list of words to learn, extracted from their context while reading a text in English.

On page 000064, the notebook turned art dictionary resumes, with the following words:

“method methodic method al32

avant-gardism33” and, on the facing page:

30 All these four terms have a corresponding Arabic translation.

31 This way in the notebook, ndr.

32 This way in the notebook, ndr. Perhaps he missed hearing the complete sound and left a space?

33 Added later, with a pencil.

“contemporary subsequent exhibition

cultural edition

Holography

engrave

engraving

anti-art

super-realizm

Parody

Bad Painting34”

Besides their translation, the grammatical function of the words is also marked. Verbs, adjectives, nouns are classified and defined to allow their correct, future use.

From scan 000062, the pages are blank.

It is almost absurd that blank pages would come out as a result of the searching entry “black.” It definitely would, unless one looks for a logical reason to that. These pages are scanned with a color-control patch, where the featured colors are marked with their respective names: “Blue, Cyan, Green, Yellow, Red, Magenta, White, 3/Color, Black.” Hence, if I would launch the research entry “cyan”, I would get the same document, again with no affiliation to the entry, except for an external, content-disconnected one.

I understand better the criteria in classifying materials in the archive: the content not being the most important reference, perhaps not at all. The unpredictability of the classification is echoed by the randomness of my findings.

I enjoy the oddness of my research: I’m not here with a purpose, I’m not supposed to follow a specific trajectory, to deliver an academic paper.

34 All the words, starting with “engrave” are written with a pencil.

I’ve been invited to explore, to interact with the archive, to respond. I start with a few open quests, entries to enter the archive, its thickness, a protective shield, like an undergrowth. I need to find my way, one document leading to the second one, then to a third one and so on. There is no straight progression.

Similarly to that, I walk in circles: my daily walks, usually along a canal that displays like a more or less sinuous line, are here concentric. The place is still new, under construction: I follow the road until it ends, then turn – right or left, according to the street impediments, more often I need to U turn, literally to go back and step again my own steps. Until I reach a new street, not yet explored and I venture in that direction.

This resemblance of proceedings – the walking pattern and the archival exploration, – is perhaps more a revelation than what I found so far. Enjoyable as it is, to discover something about others –people and places alike, – nothing compares to the revelations about the self.

«I want to sense what Erin Manning calls the “anarchive,” that strange and stunning “something that catches us in our own becoming.”35 »

The annotations resume (but don’t forget that we are moving backwards, hence the spacing in time is in the opposite direction, the gap between entries guiding from a far remote past to a less distant one).

The date, // ١٩٩٥١٢٨, seems to suggest that the artist used the notebook with a certain irregularity, that empty pages were used again later – in fact, more than 15 years later, – that he went back to the same notebook after a very long time and added new entries. A stratification in time, with this only entry though, on december 8, 1995...

35 Julietta Singh, cit., 113

From 000015, the annotations reappear, in the usual light blue ink: they are undated, although spaced.

On the following two pages [000013-000014] there is a poem written over two pages, in a black ink, and titled “ما”

The entry on the right page of the 000013 document is dated // ١٩٩٤١٠٢٩, and is written with the same black ink, which could suggest the poem was written around the same time.

Search: “VOID”

There are four documents that emerge from the archive, the only interesting one – in the sense of fully responding to the purpose of my search, – being AD_MC_095_ref262_000001_000009_d, two pages from a catalogue Journey through the Contemporary Arts in the Arab World.

Contemporary Artists from Wadi Al-Rafideen,” Darat Al Funun. Abdul Hameed Shoman Foundation, Amman Jordan, 2000.

Presenting a 1989 work by Sa’di Al-Ka’bi (يبعكلايدعس), described as a mixed media on wood, 90×80 cm, with this accompanying text:

“Although Ka’bi is inclined to an austere color economy almost limited to ochre and brown in its tonal degrees, outward-moving, phantom-like, figures generate from the depth of his painting, but they are void, and are only given concrete form by virtue of their outside lines.”

Search: “VACUUM”

The only entry here is the same page of the catalogue previously reviewed36 .

May 14, 2024. Tuesday

Search: “LACK”

As I copy-paste the lines from yesterday to open with my new, daily search, I just realize “lack” is “black” without a letter. Or vice-versa, “black” would be “lack” with a small addition. The insignificance of single letters, the relevance of their associations. The misunderstandings generated by unintentional replacements, the serendipities occurring around those same unintentional substitutions.

My late father’s birthday… the mind plays tricks on my rationality: one believes they can keep certain emotions at bay, and then they reappear in the most duplicitous way, like reminders of an intentionally missed appointment.

Four documents emerge from the archive.

The first one is a paper clipping, a review appeared on “The Jerusalem Star,” on December 17, 1987: it is written by Margarette Hall, and is about an exhibition of works by artists Ahmad Na’wash37 .

It is not an especially flattering review, or at least it is one that flatters by means of distortion: saying the opposite, recognizing elements of disagreement and deception to then eventually glorifying that same defect. It is a weird way of complimenting, if ever complimenting was in the intentions of the author.

I am intrigued to learn more about the relationship between the artist and the art critic, if they were part of a same circle, if they weren’t.

There is a feeling of acrimony in the review, but perhaps that is the writer’s style, and it’s not due to any specific sentiment towards the artist.

Here is the passage where “lack” is mentioned:

“Each painting is deceptive... This is seen in the manner by which he paints his figures’ hands and feet. Each is drawn with a distinct lack of detail, and the artist just concentrates on the actual shapes. [...] Na’wash is trying to show the people who do not have an aim in life and lack of selfconfidence.”

The second document is a brochure with the conditions to apply to the exhibition “Art for Humanity. Baghdad International Festival of Art 1990.”

The clause no. 13 reads:

“Entries that lack one of the aforementioned terms or reach at a later time than the specified one shall not be accepted.”

The third document is a cardboard printed on the occasion of a UNESCO exhibition titled “Hope and Peace” that took place in Amman, Jordan and opened on April 4, 200038. The lines that respond to the search are the following:

“Despite the lack of communications with the international art movement the scarcity of references, the Iraqi painters innovated theirs own methods to express their artistic views. Their language aims at fostering a human civilized dialogue to nurture a culture of peace all over the world.”

The year 2000 is labeled as “International year for the Culture of Peace,” a label that keeps recurring, in different formulations, to appeal to what we are lacking the most, in the region. More than an affirmation, an invocation, almost a prayer.

The last document is a page from a catalogue on Marwan, titled “MARWAN,” and published by Darat al Funun [year is missing]39 .

Mistakes and misspellings are numerous: “ist” instead of “is,” “vulnerbility,” senuous,” etc. which are perhaps due to German linguistic interferences (the author is Jörn Merkert).

The passage including “lack” is a long one, and it reads:

“... the isolation of the figures can be experienced so keenly, almost painfully, as loneliness. For emptiness which surrounds them is a dense, oppressive one. It is not merely artificial space, but a coexistence within the painting, limiting and restricting the figures. One accepts the fragmentation of these human beings because it is identical with the artistic means and therefore directs one’s interpretation, releasing it from speculation. Emptiness is the oppressor, cutting down these figures, crippling them, reducing them to egos, locking them in a tension which they seem to tolerate under the pressure of their own silence, Only through severe straining, through exaggerated, frozen signs and gestures, is this lack of communication even dented. When it is, when it starts to give, we are confronted with fundamental questions about human beings.”

I find the following lines also interesting, as they refer to the notion of veil, that I also explore in my own practice:

“In the “veil paintings” (1970-1973), the motif of the shawl ... gives a more specific definition to the formerly obsessive though vague psychological content. It conceals, thus reveals, offers insight. Like a kind of bandaging it protects and hides, evoking a sense of resistance and inaccessibility. But combined with the pride one feels associated with such veiling,.... the shawl not only conceals – it exposes. Mysteriously, it tenders promises.”

Search: “NEGATIVE”

The first entry, out of four, is an excel file, for organizing the “negatives” in Nasiri’s archive. Film negatives, indeed negatives, and yet in a different acceptation.

The second document is the same article already recorded referring to “Strokes of Genius.”

The last two documents are pages from a catalogue on contemporary Indian painting, and more specifically on Neo-Tantra. Here “negative” is introduced with reference to symbolism: “... such as the triangle facing upwards, denoting purusha (positive male sprit 40),, or facing downward, indicating prakrit (negative or female spirit)...”

If observing the punctuation and use of connectors, one would notice the immediacy in the identification of male and positive energy, while “or” is introduced to denote the opposite: the negative or the female, as to try to minimize the perfect identification of the two, without nevertheless excluding it.

40 This way in the text.

Search: “EXILE”

The only document responding to the search request is a poster-like announcement for a show (January 6 – February 20, 2006) curated by Nada Shabout, and titled “Dafatir: Contemporary Iraqi Book Art41.”

The line reads as follows: “The artists in the exhibition, many now living in exile, include...”

On this page, it isn’t mentioned if the exhibition took place at the University of North Texas, where Nada Shabout has been teaching Art History with a focus on Middle Eastern art for the past 20 years, or elsewehere.

The document is presented in 4 scans: on the first one the place is mentioned, Carleton College, whose location is further precised on the last scan as Northfield, Minnesota, with a note reading: “The exhibition was organized by the University of North Texas Art Gallery.”

Small investigative satisfactions...

Search: “NOSTALGIA”

No document responds to this search entry. There is no trace of nostalgia in the archive.

Search: “LONGING”

Six documents emerge from the archive.

The first and the fifth ones are pages from the catalogue of the Baghdad International Festival of Art 1988.

The second one is a brochure of the French Cultural Centre in Baghdad (CCCL Bagdad, Janvier 09), with the Spring programming.

The third one is the text in Marwan’s catalogue, seen before (under the entry “lack”)

The fourth one is a page dedicated to the artist Rissan, and compiled by art critic Farouq Yousif, in the catalogue “Baghdad Group.” (see above, under “absence”)42

The last one is a paper clipping from a French newspaper, perhaps “L’orient Le Jour”, as a publicity for a shop in Rue Hamra makes me suppose. The article, which appears on the first page and continues inside – on the cultural page, arguably, – is titled “La peinture syrienne d’aujourd’hui – cela existe…” and is authored with brio by Salah Stetie43

Search: “BELONGING”

10 documents emerge from the archive.

The first four are multiple copies of the text written by Belasim Mohammed for a catalogue, “Shadows of the Truth” (ةقيقحلاللاظ), apparently accompanying the solo exhibition by artist Ala Bashir, in 1988.

The text is not interesting with respect to the acceptation of “belonging” that I am investigating.

The fifth document is the introduction from the catalogue “Yemeni Contemporary Art Exhibition 2” ( رصاعلماينميلايليكشتلانفلليناثلاصرعلما 2 ) on Yemeni Art, apparently accompanying a show that took place in Sana’a, dated October 29, 1997.

The text, authored by A’amna Al-Nassiri, is descriptive and “belong” is used in a technical way, with no reference to the notion of belonging per se.

The sixth one is a page from a booklet on Ala Basher.44

The text by Ala’ Bashir [signed this way in the booklet, although contradicting the spelling of the title on the cover], titled “Dialoge of Awakening45” is poetic and charged with a sense of sadness that, regardless of not coming out under the searching entry “nostalgia” should have. I transcribe it here in its entirety:

“I soon realized I was facing the strategic occupied Golan Heights. Behind this spot, the bulk of the lake teberias was located. The only visible part of the lake, to the South of the Heights, was residing in the shadow of the misty horizon which spread itself over the occupied land at the hour of the noon.

We were sitting on the peak of a high plateau converted to serve as a tourist restaurant at the splendid district of Umm Qeis, north of the Jordanian city of Irbid. Up there, on the lip of the escarpment, the thing that separated us from the Golan Heights was a valley embracing a number of farms belonging, as I was told, to the inhabitants of the Israeli settlements. It never came across my mind that one day I would live through such an experience and at the very moment I 44 AD_MC_095_ref182_000001_000006_d; AD_MC_095_ref182_000001_000002_d 45 This way in the text.

felt that a dialogue, never known to me before, developed between my hands and the arms of the chair on which I sat. The sight had certainly conjured up visions of the past. It took me as back as 1948 when as little children we took to the streets to bid farewell to the soldiers going to the front in Palestine, to the memories of the demonstrations and strikes in which, as students, we took part with other portions of the people about issues concerning Palestine and the occupied land and to the scene of that day in which I sat with my friends eating our lunch and admiring the beauty of the scenes of the usurped lands, I felt some kind of bitterness laden with grief and smelt a scent of humuliation46 and shyness. I wished I could dwindle in size and if it not were to these thoughts this exhibition could not have seen the light.”

46 This way in the text.

The seventh document is a brochure/card announcing the opening (Mina Gallery, Baghdad, February 25, 2000) of an exhibition of paintings by Iraqi artists.

The text is not interesting with respect to the acceptation of “belonging” that I am investigating.

The eighth and ninth ones are the page on Haithem Hassen, that was listed before under the “absence” entry. Belong is used in a technical way and doesn’t reflect on the notion of belonging per se.

The last document is a page from a booklet/catalogue on the artist Fuad Al-Futaih. Here again, the text is not interesting with respect to the acceptation of “belonging” that I am investigating.

Search: “HOME”

I am not sure why I am searching for “home.” I refuse the concept at a conscious level, and yet I fall back emotionally.

I say to myself, this is a natural progression, from “exile” to “nostalgia,” to “longing”, and then to “belonging.” Home seems the next term to explore, and I address this logically, semantically, not emotionally.

Beside the fact that citizens of certain Arab countries – mostly those covered by the current state of the archive, that is Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine – are inherently familiar with the experience of exile, and consequently of “home” as a denied dimension.

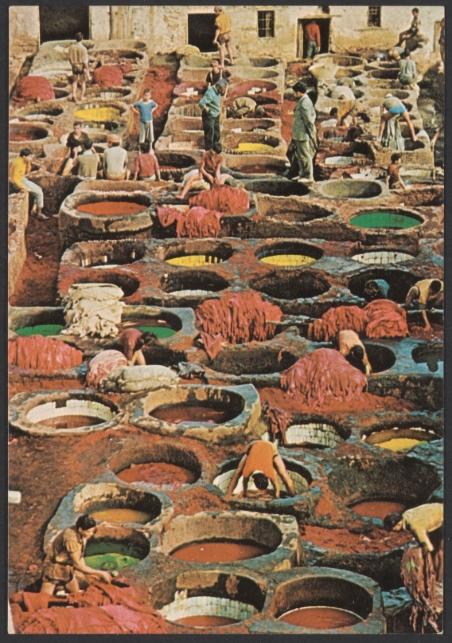

This resonates my function here, at the archive, the scope of my presence. I am explaining to a friend, who tries to understand the nature of this archive and what I am doing here – this happens over a Moroccan tea served with grace, – that the archive preserves the paraphernalia of an artist’s practice: the documents, the sketches, the journals, notebooks, postcards and letters, personal photos as well as published catalogues and paper clippings.

Everything but the artworks, everything witnessing the daily exposure to the artistic practice, the very surroundings of being an artist. A void is left intentionally unexplored, the actual core for most art historians, who typically focus on the outcome of an artistic practice, rather than on the process behind it.

Is the archive always a testimony of life? This one seems to be, rather favoring life over creation. But in that configuration, then, I see my obsession for absence satisfied: the archive I am exploring is structured around the absence of the artworks represented in their legibility, represented in their realism.

I am walking along the periphery of creation, that’s why walking in circles seems so appropriate. I am not even trying to recreate a clear path followed by a specific artist, at a defined moment of their trajectory. I am flirting with the traces of their understanding of being an artist, and often simply of being a human being.

Besides a series of documents (CVs and bios, published in catalogues and brochures), where “home” is mentioned within the impartial context of a biography; and a series of either actual business cards or annotations on various notebooks, containing all relevant contact information, following the structure of a business card, the archive reveals a few interesting documents.

The first one is the manifesto of the Baghdad Group, presented on the last page (for the Arabic version it will be the first page) of the catalogue of the same title47. The passage referencing “home” reads:

“After all that silence, something must be said. [...]

Our home with its unseen walls is a planet that has escaped its galaxy, filled with emotion it is calling us to glorify forgetfulness and to chase the wonderful sensation of the unseen. Our home is the world in its instinctive vigority48, the place where we find innocence, purity, widenes49, annihilation, nobility, knowledge, morals, forgiveness, rebellion, freedom and brotherhood. […]”

The second document is a page from a notebook where all coordinates are given, including home, as a self-acknowledgment.

The following document is a postcard, with a thick Arabic text and signed by Wijdan, reproduces – as it is mentioned on the back of it, top –

“Veiled Vestal Virgin by Raffaelle50 Monti (1818-81) in the Dome Room, Chatsworth.

Photograph by David Vintiner”

50 This way in the text.

The lower line on the back of the postcard explains:

“Chatswroth, Home of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire.”

The front image is that of a magnificent sculpture from a breath-taking series that I have admired with the painful consciousness that unreachable perfection always inspires me, in Madrid at the Prado museum just last summer.51

How many sculptures from this series did Monti create? Who were his disciples? And was there a school specialized in the marble rendering of transparent textiles in contact with the human body? Similar questions might have struck Wijdan as well, as she saved a memory of the encounter in the simplest, and most accessible way offered by mass reproduction means.

51 The postcard reproduced here illustrates the quality of the image consulted, but it is not issued from the Al Mawrid’s archive, as the photograph referenced in the text belongs to a series of documents that, per al Mawrid's policy and the collection agreements with custodians, cannot be publicly shared.

Last, a page from a notebook52, where Arabic and English are equally used, presents on the left page, a few lines in a nicely composed Arabic, underneath which the artist has glued a paper stripped from another notebook, which reads:

“1a.m. a home53 too soon SACK OUT!

Should try to apply French logic, figure out why I sleep so well at Sofitel Paris”

The text is “canceled” by means of a red cross traced with a thick pastel.

The page on the right, with a landscape orientation, presents a clipping from a magazine, with a semi-naked lady, shown from back, elongated on a solar bed and hanging on her right elbow, looking at the swimming pool – an inside swimming pool, like those of thermal waters retreats, the sanitarium of Musil-ian [early XX century] memory, – in front of her. A date is overwritten on the picture in a fading ink: apparently 11.11.1976.

Two black arrows point respectively to the right and the left edges of the notebook, while a series of 5 red arrows point upwards, to a cloud-like drawing. Underneath is a short text in Arabic.

52 The document (26. AD_MC_092_ref7_000011_d) could not be reproduced in the context of this publication.

53 As I check my notes again, I am not sure anymore about the correct reading of “home.” the word rather looks like “none,” based on the calligraphy of the author, and the “a” too is different from the others in the same text. But then, what would it mean: “none too soon”.

Search: “ETEL ADNAN”

Apart for the two photographs already recorded, there is only one envelope of a letter written by Etel Adnan to May Muzaffar, with the printed postal date of 09-01-17 (and an acceptance postmark dating to the previous day, January 16, 2017).

The back of the envelope contains the two addresses, like it is customary, and yet here so exceptionally so:

“Etel Adnan

29 Rue Madame Paris, 75006”

and:

“May Muzaffar

P.o. box 941840

11194 AMMAN

Jordanie”

Etel Adnan wrote on a postcard reproducing, as printed on the outside:

“Kazimir Malevich (Russian, 1878–1935) Suprematism, 1915 [...]

Published by the Russian State Museum Publishing Company, New York, and te Neues Publishing Company, New York

© 1990 Russian State Museum Publishing Company and te Neues Publishing Company

Printed in the Federal Republic of Germany“

“Dear May, I did receive Rafa’s “Artist books” book, thanks to you, a new year present. I looked at it so intensely, so carefully. What a beautiful collection of works. To be part of it is really a privilege. What touched me most is the presence of his hands54 on the papers. How moving! Here, we are surviving, in the chaos of the world, but always hoping for the best... like the little birds on the tree. And many thanks, and much much much love, Etel”

Search: “HUGUETTE CALAND”

No related document.

Search: “SALWA RAOUDA CHUCKAIR”

No related document.

54 Underlined in the hand-written text.

Search: “SURSOCK”

Only one document responds to the search entry, a newspaper clipping (published in L’Orient Le Jour) about a soirée at the Sursock Museum gathering Lebanese and Syrian artists.

My Lebanese search is over, not fully satisfied but over55

55 The stamps reproduced here illustrate the quality of the images consulted, but they are not issued from the Al Mawrid’s archive, as the photographs referenced in the text belong to a series of documents that, per al Mawrid's policy and the collection agreements with custodians, cannot be publicly shared.

May 15, 2024. Wednesday

search: “TRANSIENT”

search: “EPHEMERAL”

The archive doesn’t respond to these entries: nothing transient, nothing ephemeral seems to be contained in this repository.

Of course an archive is the opposite of a transient, ephemeral reality. It is its negation, the conscious attempt to win against transience and ephemerality, the purpose of an archive being preservation, the propagation of past documents into the future, their safe trajectory from a potential loss into a secure conservation.

And yet, ephemeral are in most cases the very documents that make it into the archive, the photographs printed in now-vanishing colors, the hand-written – in fading inks and pencils –letters, postcards and journals, the yellowish/yellowed paper clippings.

While searching “ephemeral”, the whole archive should proclaim its existence, should claim its right to escape impermanence, to evade evanescence and reclaim their intention to resist.

Can an archive be seen as an act of resistance, as a counter-position – simply as it defies the natural tendency to decay, to deteriorate, to fade?

Can an archive symbolize our human ambition to immortality?