Into this world falls a plane.

The earth is a mineral speckle planted in trees. The plane snagged its wing on a tree, fluttered in a tiny arc, and struggled down.

I heard it go. The cat looked up. There was no reason: the plane’s engine simply stilled after takeoff, and the light plane failed to clear the firs. It fell easily; one wing snagged on a fir top; the metal fell down the air and smashed in the thin woods where cattle browse; the fuel exploded; and Julie Norwich seven years old burnt off her face.

We looked a bit alike. Her face is slaughtered now, and I don’t remember mine. It is the best joke there is, that we are here, and fools—that we are sown into time like so much corn, that we are souls sprinkled at random like salt into time and dissolved here, spread into matter, connected by cells right down to our feet, and those feet likely to fell us over a tree root or jam us on a stone. The joke part is that we forget it. Give the mind two seconds alone and it thinks it’s Pythagoras. We wake up a hundred times a day and laugh.

The joke of the world is less like a banana peel than a rake, the old rake in the grass, the one you step on, foot to forehead. It all comes together. In a twinkling. You have to admire the gag for its symmetry, accomplishing all with one right angle, the same right angle which accomplishes all philosophy. One step on the rake and it’s mind under matter once again. You wake up with a piece of tree in your skull. You wake up with fruit on your hands. You wake up in a clearing and see yourself, ashamed. You see your own face and it’s seven years old and there’s no knowing why, or where you’ve been since. We’re tossed broadcast into time like so much grass, some ravening god’s sweet hay. You wake up and a plane falls out of the sky.

ANNIE DILLARD, Holy the Firm

To live in the gap between the moment that is expiring and the one that is arising—luminous and empty. The real city, falling through your mind in glittering pieces. And when you close your eyes, what do you see? Nothing. Now open them!

LAURIE ANDERSON, Heart of a Dog

At the time of Lewis and Clark, setting the prairies on fire was a well-known signal that meant, “Come down to the water.” It was an extravagant gesture, but we can’t do less. If the landscape reveals one certainty, it is that the extravagant gesture is the very stuff of creation. After the one extravagant gesture of creation in the first place, the universe has continued to deal exclusively in extravagances, flinging intricacies and colossi down aeons of emptiness, heaping profusions on profligacies with ever-fresh vigor. The whole show has been on fire from the word go. I come down to the water to cool my eyes. But everywhere I look I see fire; that which isn’t flint is tinder, and the whole world sparks and flames.

ANNIE DILLARD, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

But when you think of giving up, don’t.

SIA KATE FURLER, “Bang Your Head”

It would be a dirty, filthy, vulgar lie to suggest that I am responsible for anything in this booklet other than its design, this introduction, the suggested further reading, and maybe two other things, so I need to start by thanking Brian Brantner, Jon athan Loibner-Waitkus, Envato, and—most importantly—ChatGPT for making it all possible.

This is not a comprehensive survey of American literature. It’s simply a collection of bios on the authors we cover in my American Literature: 1865-Present class. With the exception of a section on the Harlem Rennaisance, the Beat Generation, and the suggested further reading section.

The further reading is a list I created of books written by American authors between 1865 and the present that I feel everyone should read. Some are modern classics. Some I just love personally.

Enjoy!

—ALW

James Baldwin (1924–1987) was a towering American writer, essayist, and activist whose work explored the intersections of race, sexuality, and identity in 20th-century America. Born in Harlem, New York, Baldwin grew up in poverty under the strict rule of a deeply religious stepfather. His early experiences with racism and religious fervor shaped much of his later writing. A precocious student, Baldwin began writing at a young age and eventually became a preacher during his teenage years, though he later distanced himself from organized religion.

Baldwin’s writing was known for its lyrical style, incisive social critique, and unflinching honesty. He wrote passionately about the psychological toll of racism, the complexities of Black identity, and the struggles of queer individuals, often blending personal narrative with cultural analysis in works like “Going to Meet the Man.” His novel Giovanni’s Room (1956) broke ground in its exploration of homosexuality and alienation.

Throughout his life, Baldwin remained a public intellectual, speaking out against injustice with eloquence and urgency. His works continue to resonate for their insight into America’s ongoing struggles with race and inequality. Baldwin died in 1987 in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, but his legacy endures as one of the most vital voices in American literature and thought. ■

In his early twenties, Baldwin moved to Paris, seeking distance from American racial hostility and creative constraint. Exile became a key theme in his work, allowing him to reflect on the American experience from abroad. His first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), is a semi-autobiographical examination of faith, family, and self-discovery. His essays, particularly those in Notes of a Native Son (1955) and The Fire Next Time (1963), brought him national prominence as a voice of moral clarity during the civil rights movement.

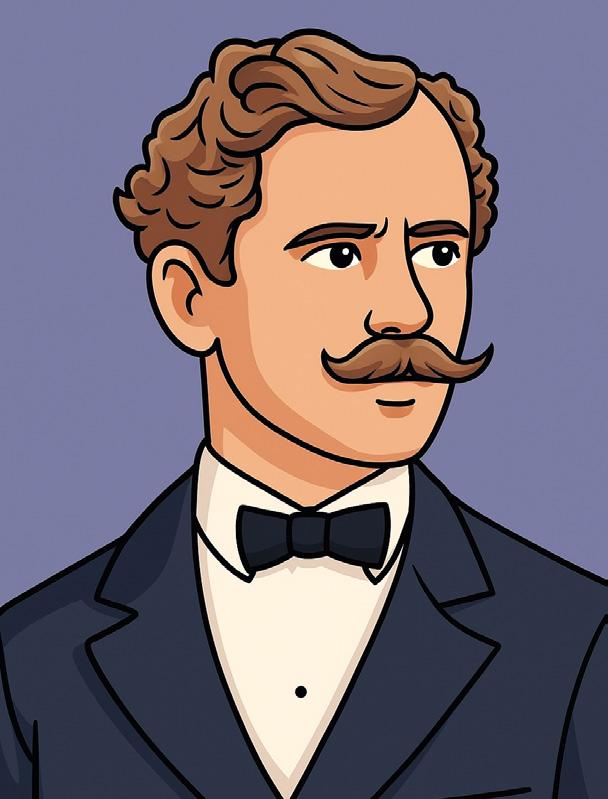

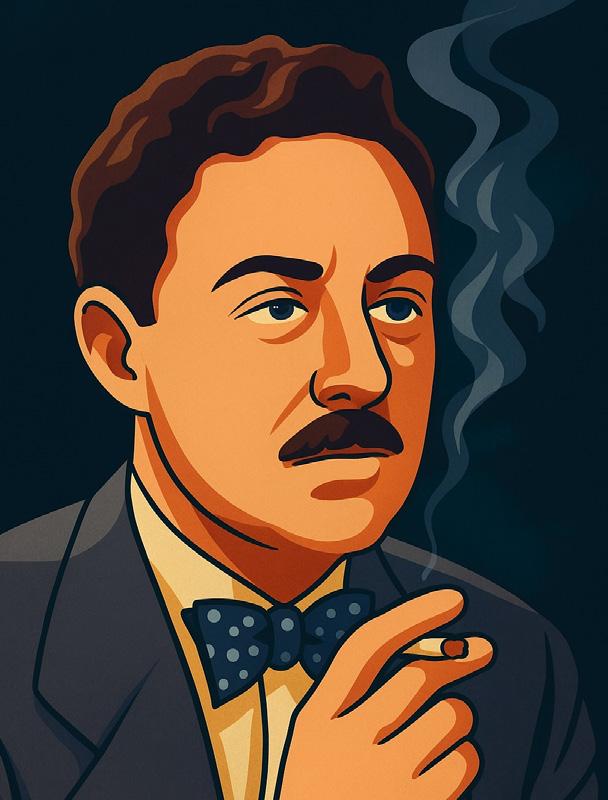

Ambrose Bierce (1842–circa 1914) was an American writer, journalist, and satirist best known for his darkly cynical wit and masterful use of irony. Born in Meigs County, Ohio, Bierce was the tenth of thirteen children. His early life on the frontier and limited formal education instilled in him a self-reliant, skeptical temperament that would characterize much of his later work.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Bierce enlisted in the Union Army and served with distinction, notably at the Battle of Shiloh—a harrowing experience that left a deep psychological imprint on him. These wartime experiences became the basis for some of his most powerful short stories, including “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” and “Chickamauga,” both of which exemplify his stark, realistic depictions of war and death.

After the war, Bierce worked as a journalist in San Francisco, where he gained a reputation for his

razor-sharp wit and fearless criticism. His most famous work, The Devil’s Dictionary (1911), offers satirical definitions of common terms, exposing the hypocrisy and absurdities of modern life. His fiction—particularly his short horror and supernatural tales—helped lay the groundwork for American weird fiction, influencing writers such as H.P. Lovecraft.

In 1913, at the age of 71, Bierce traveled to Mexico during its revolution, ostensibly to observe the conflict firsthand. He vanished without a trace, and his fate remains one of American literature’s most enduring mysteries.

Bierce’s legacy endures in his uncompromising vision, literary innovation, and mastery of the short story form. His work continues to be studied for its bold style, Gothic style, biting humor, and exploration of themes like war, death, and the limits of human reason. ■

William S. Burroughs (1914–1997) was an American novelist, essayist, and spoken word performer who became one of the most influential and controversial figures of 20th-century literature. Born into a wealthy St. Louis family, Burroughs studied at Harvard and later lived in Europe before settling into the bohemian underground of New York City. He became a central member of the Beat Generation, alongside Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, although his work often stood apart for its radical experimentation and darker, more surreal themes.

Burroughs is best known for his novel Naked Lunch (1959), a groundbreaking work that defies conventional narrative and explores addiction, control, sexuality, and the grotesque. The book was initially banned for obscenity, leading to a landmark court case that helped expand the boundaries of free expression in American literature.

Much of Burroughs’ writing is informed by his own life—particularly his struggles with heroin addiction, his experiences as an outsider, and the accidental shooting death of his wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951, an event that haunted him for the rest of his life. His later work, including the Nova Trilogy, employed a “cut-up” technique of text manipulation, developed with artist Brion Gysin, which aimed to disrupt linear storytelling and reveal hidden meanings.

Burroughs influenced a wide range of artists, from writers and musicians to visual artists and filmmakers. His voice—detached, incisive, and often dystopian—remains a touchstone for countercultural movements and avant-garde literature. Despite the controversies surrounding his life and work, Burroughs carved a permanent place in literary history as a radical innovator and unflinching chronicler of the margins of society. ■

Kate Chopin (1850–1904) was an American author best known for her groundbreaking exploration of female identity, autonomy, and desire during a time when such subjects were often considered taboo. Born Katherine O’Flaherty in St. Louis, Missouri, Chopin was raised in a matriarchal household after the early death of her father. Her upbringing among strong, independent women would later influence the themes of her fiction.

In 1870, she married Oscar Chopin and moved to Louisiana, where she became deeply immersed in Creole and Cajun cultures—rich settings that would later populate many of her stories. After Oscar’s death in 1882, Chopin returned to St. Louis with her children and began writing as a means of financial and emotional support.

Chopin’s early work, including her short stories published in magazines like Vogue and The Atlantic Monthly, received modest acclaim. Her fiction often

centered on the everyday lives of women, especially in the American South, and subtly challenged societal expectations surrounding marriage, motherhood, and sexuality.

Her most famous work, The Awakening (1899), tells the story of Edna Pontellier, a woman who seeks personal and sexual freedom in a rigidly patriarchal society. The novel was met with shock and condemnation upon release for its candid portrayal of female desire and autonomy, effectively ending Chopin’s literary career during her lifetime.

Despite the initial backlash, The Awakening was rediscovered in the mid-20th century and is now regarded as foundational incfeminist literature. Today, Kate Chopin is celebrated as a pioneering voice who anticipated many of the themes of modern feminism and psychological realism. Her work continues to resonate with readers seeking honest, nuanced portrayals of women’s inner lives. ■

Sandra Cisneros (born 1954) is a celebrated American writer, poet, and essayist whose work explores themes of identity, culture, gender, and belonging. Best known for her debut novel The House on Mango Street (1984), Cisneros has become a major figure in contemporary American and Chicana literature, giving voice to the complexities of growing up Latina in the United States.

Born in Chicago to a Mexican father and Mexican American mother, Cisneros was the only daughter among seven children. Her bilingual and bicultural upbringing—marked by frequent moves between the U.S. and Mexico—influenced her sense of marginality and shaped the themes of fragmentation and displacement in her writing. She earned a B.A. from Loyola University Chicago and later an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she began to develop her unique literary voice.

The House on Mango Street, a series of lyrical vignettes told from the perspective of a young Chi-

cana girl named Esperanza Cordero, became a landmark text in multicultural and feminist literature. The novel has been widely translated, taught in schools across the U.S., and praised for its poetic style and powerful portrayal of female empowerment, poverty, and cultural identity.

Cisneros’s other notable works include the short story collection Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories (1991), the poetry collection Loose Woman (1994), and her memoir A House of My Own (2015). Her writing is deeply rooted in personal experience and often centers on the lives of women negotiating cultural expectations and personal freedom.

A tireless advocate for literacy and the arts, Cisneros has received numerous awards, including the MacArthur “Genius” Grant. Through her work, she continues to inspire new generations with her fierce, lyrical storytelling and commitment to social justice. ■

Edward Estlin Cummings (1894–1962), known as E.E. Cummings, was an American poet, painter, essayist, and playwright celebrated for his unconventional use of form, punctuation, and syntax. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cummings showed an early interest in writing and art. He earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Harvard University, where he was influenced by modernist movements and began to experiment with poetic forms.

Cummings served in World War I as a volunteer ambulance driver in France, an experience that deeply shaped his worldview. He was briefly imprisoned by French authorities on suspicion of espionage, an episode he later chronicled in his autobiographical novel The Enormous Room (1922). This work marked the beginning of his literary career, characterized by a fierce individuality and defiance of conventional literary expectations.

Over his lifetime, Cummings published nearly 3,000 poems, along with plays, essays, and artworks. His poetry is noted for its playful and radical use of grammar and typography, which he used to emphasize emotion, visual impact, and musicality. While his techniques were at times criticized, they also brought a fresh and distinctive voice to American poetry. Cummings often explored themes of love, nature, individuality, and the human spirit with both lyrical beauty and biting wit.

Despite his style, Cummings was a traditionalist in some respects—especially in his lyrical subjects and personal values. His works eventually gained widespread recognition, and he is now considered one of the most innovative and influential poets of the 20th century. E.E. Cummings died in 1962 in North Conway, New Hampshire, leaving behind a body of work that continues to inspire and challenge readers with its originality and enduring charm. ■

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) was an American poet whose innovative and introspective work fundamentally reshaped the landscape of American literature. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, Dickinson lived much of her life in reclusive isolation, rarely venturing beyond her family’s home and grounds. Though she maintained a close correspondence with a select circle of friends and intellectuals, she published fewer than a dozen of her nearly 1,800 poems during her lifetime—and often anonymously or heavily edited to fit conventional norms.

Educated at Amherst Academy and briefly at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, Dickinson was well-read and intellectually curious, influenced by writers such as Shakespeare, the Brontë sisters, and the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. Her poetry, marked by its short lines, slant rhyme, and idiosyncratic punctuation—especially her signature use of dashes—deals with themes of death, immor-

tality, nature, love, and the inner life of the soul. Though seemingly removed from the world, Dickinson observed life with intense scrutiny and emotional depth. Her work often wrestles with existential questions and reveals a fierce independence of thought and voice. After her death, Dickinson’s trove of poems was discovered and posthumously published, beginning with Poems in 1890, edited by friends and family.

Initially seen as eccentric or overly sentimental, Dickinson’s reputation grew significantly throughout the 20th century, as literary scholars came to appreciate her stylistic brilliance and philosophical complexity. Today, she is regarded as one of the most important figures in American and all of English-language poetry. Her ability to distill profound truths into brief, concise, enigmatic verses has secured her place as a literary icon, whose influence continues to resonate with modern readers and writers alike. ■

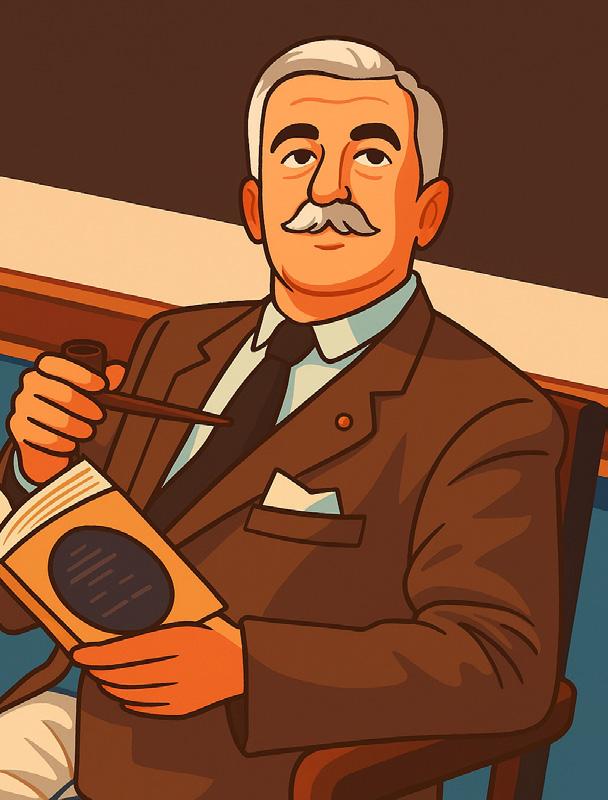

William Faulkner (1897–1962) was an American novelist, short story writer, and Nobel laureate widely regarded as one of the most important literary figures of the 20th century. Born in New Albany, Mississippi, and raised in nearby Oxford, Faulkner spent most of his life in the American South, a region that deeply influenced his work and became the central setting for his fictional Yoknapatawpha County.

Faulkner’s early attempts at poetry and prose met with little success, but he gained recognition with the publication of The Sound and the Fury (1929), a novel that broke traditional narrative forms and employed stream-of-consciousness techniques to explore the psychological depths of its characters. This was followed by other landmark works such as As I Lay Dying (1930), Light in August (1932), and Absalom, Absalom! (1936), each contributing to his reputation as a master of Southern Gothic and modernist fiction.

His stories often deal with themes of decay, racial tension, class conflict, and the inescapable legacy of history, especially as it relates to the American South. Faulkner’s complex narrative structures, shifting points of view, and deep psychological insight challenged readers but also expanded the possibilities of the novel as an art form.

In 1949, Faulkner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his “powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel.” He later won two Pulitzer Prizes and two National Book Awards.

Despite periods of critical neglect, especially early in his career, Faulkner’s literary stature grew extensively over time. Today, he is celebrated not only for his innovation and experimentation but also for his profound exploration of the human condition. His work remains a cornerstone of American literature and a major influence on writers around the world. ■

Robert Frost (1874–1963) was one of the most celebrated and influential American poets of the 20th century, known for his vivid depictions of rural life, his mastery of traditional verse forms, and his deep philosophical meditations on human existence. Born in San Francisco, California, Frost moved to Massachusetts with his family after the death of his father. Though he briefly attended Dartmouth and Harvard, he did not complete a college degree, instead pursuing a life shaped by farming, teaching, and—most enduringly—writing poetry.

Frost’s poetry is often set in the rural landscapes of New England, where he lived for much of his life. His first major collection, A Boy’s Will (1913), was published while he was living in England and was followed by North of Boston (1914), which established his reputation as a major poet. His work quickly gained recognition for its clarity, conversational tone, and psychological depth.

Though Frost employed traditional meters and rhyme schemes, his work was anything but simplistic. Poems such as “The Road Not Taken,” “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” and “Mending Wall” reveal complex themes of individual choice, isolation, nature, and the boundaries between people. His poetry often explores the tension between the comfort of the familiar and the pull of the unknown.

Frost received numerous honors during his lifetime, including four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. In 1961, he became the first poet to read at a U.S. presidential inauguration, delivering a poem for John F. Kennedy.

Despite his public persona as a homespun New Englander, Frost’s poetry often carries darker undercurrents, grappling with doubt, loss, and the mysteries of the human mind. His legacy endures as a cornerstone of American literature, blending accessibility with profound insight. ■

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935) was a pioneering American writer, social reformer, and feminist theorist whose work challenged the restrictive gender roles of her time and advocated for women’s economic and social independence. Best known for her semi-autobiographical short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), Gilman used literature and public speaking to critique the patriarchal structures that confined women to domestic spheres.

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Gilman experienced a difficult childhood marked by poverty and instability after her father abandoned the family. Despite limited formal education, she became a voracious reader and independent thinker. Her brief marriage to artist Charles Walter Stetson and the birth of her daughter were followed by a period of severe postpartum depression, which inspired “The Yellow Wallpaper”—a haunting portrayal of a woman’s mental deterioration under the “rest cure,” a common treatment for women’s mental illness in the 19th century.

Gilman went on to write extensively about the social, economic, and psychological oppression of women. Her influential nonfiction work Women and Economics (1898) argued that women’s dependence on men for financial support was the root of gender inequality. She promoted communal child-rearing, professional opportunities for women, and domestic reform.

A prolific lecturer and writer, Gilman also founded and edited The Forerunner, a monthly magazine in which she published much of her work. Her utopian novel Herland (1915) imagines a peaceful, all-female society free from war, poverty, and domination.

Later in life, Gilman was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer and, committed to rational control over her life, died by suicide in 1935.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s legacy endures as a central figure in early feminism and the mental struggle of childbirth, whose writings continue to inspire discussions about gender, mental health, and social reform. ■

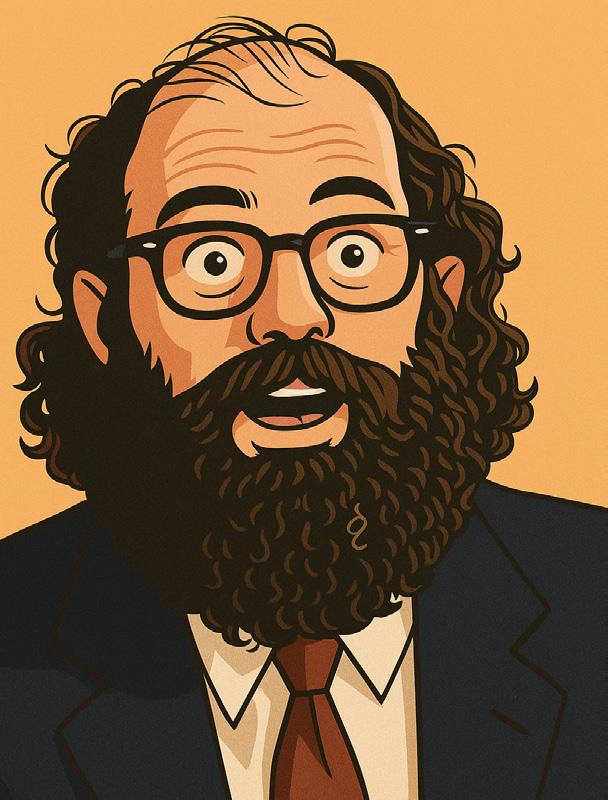

Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997) was a central figure of the Beat Generation and one of the most influential American poets of the 20th century. Born in Newark, New Jersey, to a high school teacher and a politically active mother who suffered from mental illness, Ginsberg was immersed from a young age in both intellectual and emotional intensity. He studied at Columbia University, where he met fellow Beats Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Neal Cassady, forming the nucleus of a literary movement that challenged mainstream values.

Ginsberg’s breakthrough came with the 1956 publication of Howl and Other Poems, a blistering, surreal, and deeply emotional work that railed against conformity, consumerism, and repression.

“Howl” was considered obscene at the time, and its publisher, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, was arrested. The resulting obscenity trial became a landmark case for freedom of speech and helped solidify Gins-

berg’s status as a countercultural icon. Throughout his life, Ginsberg remained outspoken on social and political issues. He was an advocate for free expression, LGBTQ rights (as an openly gay man), and anti-war causes, especially during the Vietnam War. His spiritual explorations led him to Buddhism, and his travels to India and involvement with Eastern philosophies significantly shaped his work.

Ginsberg’s poetry blends raw honesty, political urgency, and spiritual longing, often employing long lines, repetition, and a conversational tone. His later works, such as Kaddish and Wichita Vortex Sutra, continued to explore grief, identity, and the American experience.

Allen Ginsberg died of liver cancer in 1997, but his legacy endures in poetry, politics, and pop culture. He remains a beacon for those who see literature as both personal liberation and public resistance. ■

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) was a towering figure in American literature, known for his distinctive writing style, adventurous life, and profound influence on 20th-century fiction. Born in Oak Park, Illinois, Hemingway began his career as a journalist before serving as an ambulance driver in World War I, an experience that deeply shaped his worldview and writing.

Hemingway’s early work, including his breakthrough novel The Sun Also Rises (1926), captured the disillusionment of the “Lost Generation” following World War I. He became known for his spare, understated prose—often referred to as the “iceberg theory”—which emphasized surface simplicity while hinting at deeper emotional truths beneath. His style influenced countless writers and helped redefine modern American literature.

Throughout his life, Hemingway sought adventure and intensity. He reported on the Spanish Civil

War, hunted big game in Africa, fished the waters off Cuba, and covered World War II as a correspondent. These experiences inspired much of his fiction, including A Farewell to Arms (1929), For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), and The Old Man and the Sea (1952), the latter of which earned him the Pulitzer Prize.

In 1954, Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his mastery of narrative and influence on contemporary style. Despite his public persona as a stoic and rugged outdoorsman, Hemingway struggled with mental and physical health issues in his later years. He died by suicide in 1961.

Ernest Hemingway remains one of America’s most enduring literary icons. His work continues to be read for its emotional depth, existential themes, and powerful economy of language, making him a central figure in both American and world literature. ■

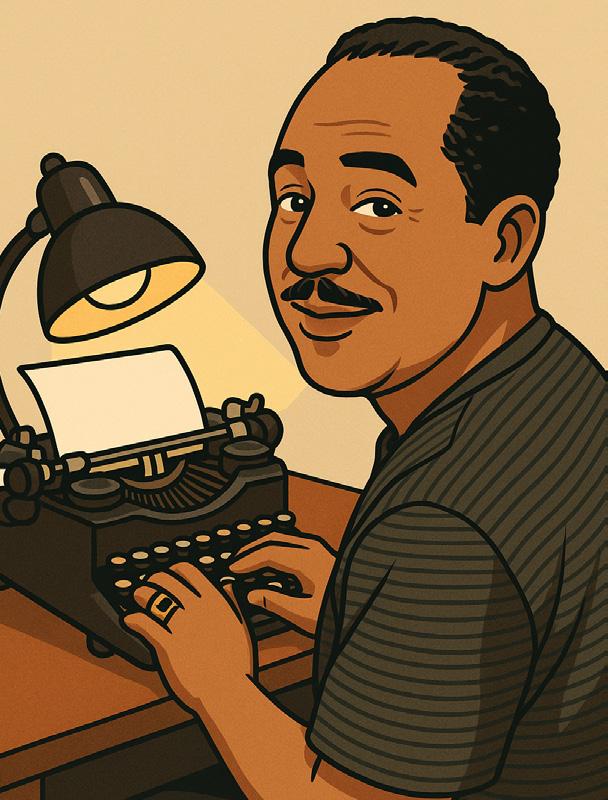

Langston Hughes (1902–1967) was a seminal American poet, novelist, playwright, and social activist, best known as a leading voice of the Harlem Renaissance—the cultural, artistic, and intellectual movement that celebrated African American life in the 1920s and beyond. Born in Joplin, Missouri, and raised in various Midwestern cities, Hughes developed a deep appreciation for the rhythms and voices of everyday Black Americans, which would later define his writing.

Hughes studied briefly at Columbia University before traveling extensively, including to Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean. These experiences enriched his global perspective and broadened the themes in his work. In 1926, he published his first poetry collection, The Weary Blues, which combined traditional poetic forms with the cadence of jazz and blues music—a hallmark of his style.

His poetry and prose addressed the joys, struggles, and dignity of African American life, often

challenging racial injustice and celebrating Black culture. Notable works include the poetry collections Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951) and Let America Be America Again, as well as his popular fictional character Jesse B. Semple (“Simple”), who offered humorous and insightful commentary on race and society in his newspaper columns.

Hughes was also a prolific playwright, essayist, and children’s author. His writing was characterized by clarity, accessibility, and a strong commitment to social justice. He believed that art should reflect the lives of ordinary people and that Black writers had a responsibility to speak directly to their communities.

Throughout his life, Hughes remained a central figure in American letters and a powerful advocate for racial pride and equality. His legacy continues to inspire readers, writers, and activists across generations for its honesty, musicality, and unwavering humanism. ■

Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) was an influential African American author, anthropologist, and folklorist, best known for her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). A central figure in the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston combined literary talent with a deep appreciation for Black Southern culture, oral traditions, and folk life, which she captured vividly in her writing. Born in Notasulga, Alabama, and raised in the all-Black town of Eatonville, Florida, Hurston was shaped by a strong sense of community and independence. She later studied at Howard University and then earned a scholarship to Barnard College, where she became the institution’s first Black graduate. At Barnard, she studied anthropology under Franz Boas, which influenced her lifelong dedication to preserving African American folklore. Hurston’s literary career blossomed in the 1920s and 1930s. Her works—including short stories, plays, and novels—celebrated the richness of

Black language, humor, and spiritual life. Their Eyes Were Watching God, her most acclaimed novel, tells the story of Janie Crawford, a Black woman seeking love, self-definition, and freedom in the segregated South. Though underappreciated at the time of its publication, the novel is now considered a landmark of African American literature.

In addition to her fiction, Hurston conducted extensive anthropological fieldwork in the American South, the Caribbean, and Haiti, documenting folk tales, songs, and religious practices. Her nonfiction work, such as Mules and Men (1935), reflects her commitment to preserving the cultural heritage of Black communities.

Despite facing financial hardship and fading into obscurity later in life, Hurston’s legacy was revived in the 1970s thanks to writers like Alice Walker. Today, she is celebrated as a literary pioneer whose vibrant storytelling and cultural insight have left a lasting mark on American literature. ■

Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964) was an American writer known for her distinctive blend of Southern Gothic fiction, dark humor, and theological insight. Though her life was cut short by illness, O’Connor produced a remarkable body of work that continues to influence writers and provoke discussion for its bold depictions of faith, morality, and human frailty.

Born in Savannah, Georgia, O’Connor moved with her family to Milledgeville after the death of her father from lupus—a disease she herself would later battle. She earned a degree in social sciences before attending the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where her talent for fiction became evident. Her first novel, Wise Blood (1952), introduced readers to her unsettling, often grotesque vision of the Southern landscape and its deeply flawed characters.

O’Connor published two novels and more than thirty short stories, many of which are collected in A

Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955) and Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965). Her stories often feature violent or absurd moments that force characters into moments of self-reckoning or spiritual clarity. A devout Catholic in the largely Protestant American South, O’Connor used fiction to explore themes of grace, redemption, and the clash between spiritual belief and secular modernity.

Stricken with lupus in her mid-20s, O’Connor lived the remainder of her life on her family’s farm, Andalusia, in Georgia, where she continued to write while raising peacocks and engaging in lively correspondence with literary figures.

Flannery O’Connor’s legacy in the United States and the world lies in her fearless exploration of the grotesque and the divine, her sharp prose, and her ability to uncover profound truths in the darkest corners of human nature. Her work remains a cornerstone of American literature and Christian existential thought. ■

Edith Wharton (1862–1937) was a groundbreaking American novelist, short story writer, and designer, best known for her incisive portrayals of upper-class society in turn-of-the-century America. The first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, Wharton combined literary elegance with sharp social critique, crafting novels that exposed the constraints and hypocrisies of the privileged classes to which she herself belonged.

Born into a wealthy New York family, Wharton was educated primarily by private tutors and through travel in Europe. From a young age, she exhibited a deep love for literature and writing, publishing her first poems and stories in the 1880s. Her insider knowledge of elite social circles gave her fiction a rare authenticity, while her intelligence and wit allowed her to challenge the very conventions she depicted.

Her breakthrough novel, The House of Mirth (1905), tells the tragic story of Lily Bart, a woman

caught between personal integrity and societal expectation. Wharton’s most acclaimed work, The Age of Innocence (1920), for which she won the Pulitzer, explores similar themes of duty, love, and repression within New York’s high society. Other significant works include Ethan Frome (1911), a bleak portrayal of rural isolation, and The Custom of the Country (1913), a satirical critique of ambition and materialism.

Wharton spent much of her later life in France, where she engaged in humanitarian work during World War I and continued to write prolifically. She published more than forty books in multiple genres, including travel, design, and autobiography.

Edith Wharton’s legacy endures for her masterful prose, psychological depth, and her ability to expose the tensions between individual desire and social constraint. Her works remain essential reading for their insight into gender, class, and the complexities of human relationships. ■

Tennessee Williams (1911–1983) was one of America’s most influential playwrights, known for his lyrical language, vivid characters, and deep exploration of human fragility. Born Thomas Lanier Williams in Columbus, Mississippi, he adopted the name “Tennessee” in homage to his father’s Southern roots. His early life was marked by family instability and personal illness, experiences that would later inform the emotional intensity of his plays.

Williams first gained national acclaim with The Glass Menagerie (1944), a semi-autobiographical work that introduced themes he would revisit throughout his career—memory, loss, mental illness, and the tension between illusion and reality. His greatest commercial and critical success came with A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), which won the Pulitzer Prize and cemented his reputation as a major American dramatist. The play’s character Blanche DuBois became one of the most iconic

roles in theater history.

Williams followed with a string of powerful plays, including Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) and The Night of the Iguana (1961), both of which explore sexual identity, personal despair, and the collapse of traditional Southern values. His work often featured deeply flawed, emotionally vulnerable characters struggling to survive in an indifferent world.

Despite his early success, Williams faced declining popularity in the later years of his career. He battled addiction, depression, and criticism, but continued to write until his death in 1983. He was found in a New York hotel room, the circumstances of his death surrounded by some controversy.

Tennessee Williams’s legacy endures through his powerful portrayals of human vulnerability and resilience. His works remain staples of American theater, celebrated for their poetic language, psychological depth, and unflinching honesty about desire, identity, and loneliness. ■

William Carlos Williams (1883–1963) was a pioneering American poet, physician, and writer whose work helped shape modernist literature in the 20th century. Known for his plainspoken style and deep commitment to capturing everyday American life, Williams rejected the formalism and European influences of many of his contemporaries, instead forging a uniquely American voice in poetry.

Born in Rutherford, New Jersey, to an English father and Puerto Rican mother, Williams spent most of his life in the town where he was born. After earning a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania—where he became friends with fellow poet Ezra Pound—he embarked on a dual career as both a practicing physician and a writer. He maintained his medical practice throughout his life, often drawing inspiration from his patients and surroundings.

Williams’s poetry is marked by its focus on the ordinary—objects, people, and moments rendered

with clarity and precision. His famous poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” exemplifies his belief that “no ideas but in things,” a guiding principle in his work. His groundbreaking collection Spring and All (1923) blended prose and verse to challenge literary conventions and champion the American vernacular.

Though initially overshadowed by modernist giants like T.S. Eliot, Williams eventually gained widespread recognition for his originality and influence. His long-form poem Paterson (1946–1958), named after the New Jersey city, represents his ambitious attempt to explore the life of an American city as a symbol of collective experience.

Williams received the National Book Award in 1950 and was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1963 for Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems. His work continues to be celebrated and taught worldwide for its innovation, accessibility, waggishness, pure entertainment, and its enduring commitment to capturing the rhythms of American life. ■

The Harlem Renaissance was a vibrant cultural, social, and artistic movement that emerged in the early 20th century, primarily during the 1920s and 1930s. Centered in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, it marked a period of remarkable creativity and intellectual growth among African Americans. This era is often considered a golden age in Black culture, during which writers, musicians, artists, and thinkers used their talents to assert their identity and challenge racial stereotypes.

The movement was fueled by the Great Migration, during which large numbers of African Americans moved from the rural South to northern cities in search of better opportunities and escape from Jim Crow segregation. In Harlem, this growing Black community became a hub of cultural expression and political thought.

Writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Claude McKay gave voice to the experiences

of Black Americans through poetry, novels, and essays. Their works explored themes of racial pride, resilience, and the African American experience. At the same time, jazz and blues—led by artists like Duke Ellington, Bessie Smith, and Louis Armstrong—became defining features of the era, influencing American music as a whole.

Visual artists like Aaron Douglas and photographers like James Van Der Zee also contributed to the movement, capturing the richness of Black life and history. The Harlem Renaissance was not only about art—it was also about empowerment and redefining how African Americans were seen in American society.

Though the movement declined during the Great Depression, its impact was lasting. It laid the foundation for later civil rights activism and affirmed the value of African American culture in shaping the broader American identity. The Harlem Renaissance remains a defining moment in U.S. history. ■

The Beat writers, or the Beat Generation, were a group of American authors and poets in the 1940s and 1950s who rejected mainstream values and explored new forms of expression. Their work challenged societal norms, embraced nonconformity, and often focused on themes like spirituality, sexuality, drug use, and the search for meaning in a materialistic world. The movement laid the groundwork for the 1960s counterculture and reshaped American literature and thought.

Key figures of the Beat Generation include Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and Gregory Corso. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) became a defining novel of the era, celebrating freedom, travel, and rebellion against conventional life. Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl (1956) was another landmark, breaking literary taboos with its raw emotional language and critiques of capitalism and repression. William S. Burroughs, known for Naked Lunch (1959), experimented with structure and

content, pushing the boundaries of narrative and subject matter.

The Beats were heavily influenced by jazz, Eastern philosophy, and the idea of spontaneous, unfiltered writing. They often gathered in coffeehouses, clubs, and bookstores, sharing their work aloud and fostering a sense of creative community. Their writing style was typically free-flowing, raw, and deeply personal.

Though initially criticized for being obscene or anti-American, the Beat writers ultimately transformed literature and culture. They inspired future generations of artists, poets, and musicians, and helped pave the way for more open discussions of race, sexuality, and personal freedom in American society.

The legacy of the Beat Generation endures as a symbol of artistic rebellion and a quest for authenticity in a rapidly changing world. ■

ANDRÉ ACIMAN

• Call Me by Your Name

LOUISA MAY ALCOTT

• Little Women

DOROTHY ALLISON

• Bastard out of Carolina

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

• Winesburg, Ohio

JAMES BALDWIN

• If Beale Street Could Talk

• Go Tell It on the Mountain

• Giovanni’s Room

KATE BORNSTEIN

• Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us

RAY BRADBURY

• Fahrenheit 451

WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS

• Giovanni’s Room

• Go Tell It on The Mountain

WILLA CATHER

• My Ántonia

• O Pioneers!

KATE CHOPIN

• The Awakening

SANDRA CISNEROS

• The House on Mango Street

HILLARY CLINTON

• Hard Choices: A Memoir

DENNIS COOPER

• Closer

• Frisk

• Wrong: Stories

DAVE CULLEN

• Columbine

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM

• The Hours

DON DELILLO

• White Noise

JOAN DIDION

• Slouching Towards Bethlehem

• The Year of Magical Thinking

ANNIE DILLARD

• An American Childhood

• For the Time Being

• Holy the Firm

• The Maytrees

• Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

• Teaching a Stone to Talk

• The Writing Life

THEODORE DREISER

• An American Tragedy

• Sister Carrie W.E.B. DU BOIS

• The Souls of Black Folks

LOUISE ERDRICH

• Love Medicine

WILLIAM FAULKNER

• Light in August

• The Sound and the Fury

RALPH ELLISON

• Invisible Man

DASHIELL HAMMETT

• The Maltese Falcon

LORRAINE HANSBERRY

• A Raisin in the Sun

JOSEPH HELLER

• Catch-22

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

• A Farewell to Arms

• For Whom the Bell Tolls

• The Old Man and the Sea

• The Sun Also Rises

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

• The Complete Short Stories

• Their Eyes Were Watching God

ALDUS HUXLEY

• Brave New World

KEN KESEY

• One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest

BARBARA KINGSOLVER

• The Bean Trees

• The Poisonwood Bible

LARRY KRAMER

• The Normal Heart

AUDRE LORDE

• Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

WENDY MACLEOD

• The House of Yes

NORMAN MAILER

• Armies of the Night

• The Executioner’s Song

• The Gospel According to the Son

• The Naked and the Dead

ARMISTEAD MAUPIN

• Further Tales of the City

• Logical Family: A Memoir

• More Tales of the City

• Tales of the City

ARTHUR MILLER

• All My Sons

• The Crucible

• Death of a Salesman

TONI MORRISON

• Beloved

• The Bluest Eye

• Song of Solomon

MICHAEL NAVA

• Carved in Bone

• Howtown

• Lay Your Sleeping Head

LEWIS NORDAN

• Lightning Song

• Sugar Among the Freaks

• Wolf Whistle

MARSHA NORMAN

• ‘night, Mother

FLANNERY O’CONNOR

• Everything That Rises Must Converge

• A Good Man Is Hard to Find

• Wise Blood

EUGENE O’NEILL

• The Hairy Ape

• The Iceman Cometh

• Long Day’s Journey into Night

CHUCK PALAHNIUK

• Fight Club

• Invisible Monsters

SYLVIA PLATH

• The Bell Jar

THOMAS PYNCHON

• Gravity’s Rainbow

• The Crying of Lot 49

ANN RULE

• The Stranger Beside Me

CARL SAGAN

• Contact

• The Catcher in the Rye

• Franny and Zooey

LESLIE MARMON SILKO

• Ceremony

UPTON SINCLAIR

• The Jungle PATTI SMITH

• Just Kids

• M Train

JOHN STEINBECK

• The Grapes of Wrath

• Of Mice and Men

AMY TAN

• The Joy Luck Club

MARK TWAIN

• The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

• A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

GORE VIDAL

• The City and the Pillar

• United States: Essays 1952-1992

KURT VONNEGUT

• Breakfast of Champions

• Cat’s Cradle

• Deadeye Dick

• Fates Worse than Death

• Galápagos

• God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

• Hocus Pocus

• Mother Night

• Player Piano

• The Sirens of Titan

• Slapstick

• Slaughterhouse-Five

• Welcome to the Monkey House: Stories ALICE WALKER

• The Color Purple BOOKER T. WASHINGTON

• Up from Slavery

EDITH WHARTON

• The Age of Innocence

• Ethan Frome

• The House of Mirth

EDMUND WHITE

• The Beautiful Room Is Empty

• A Boy’s Own Story

• The Farewell Symphony

THORTON WILDER

• Our Town

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

• Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

• The Glass Menagerie

RICHARD WRIGHT

• Native Son

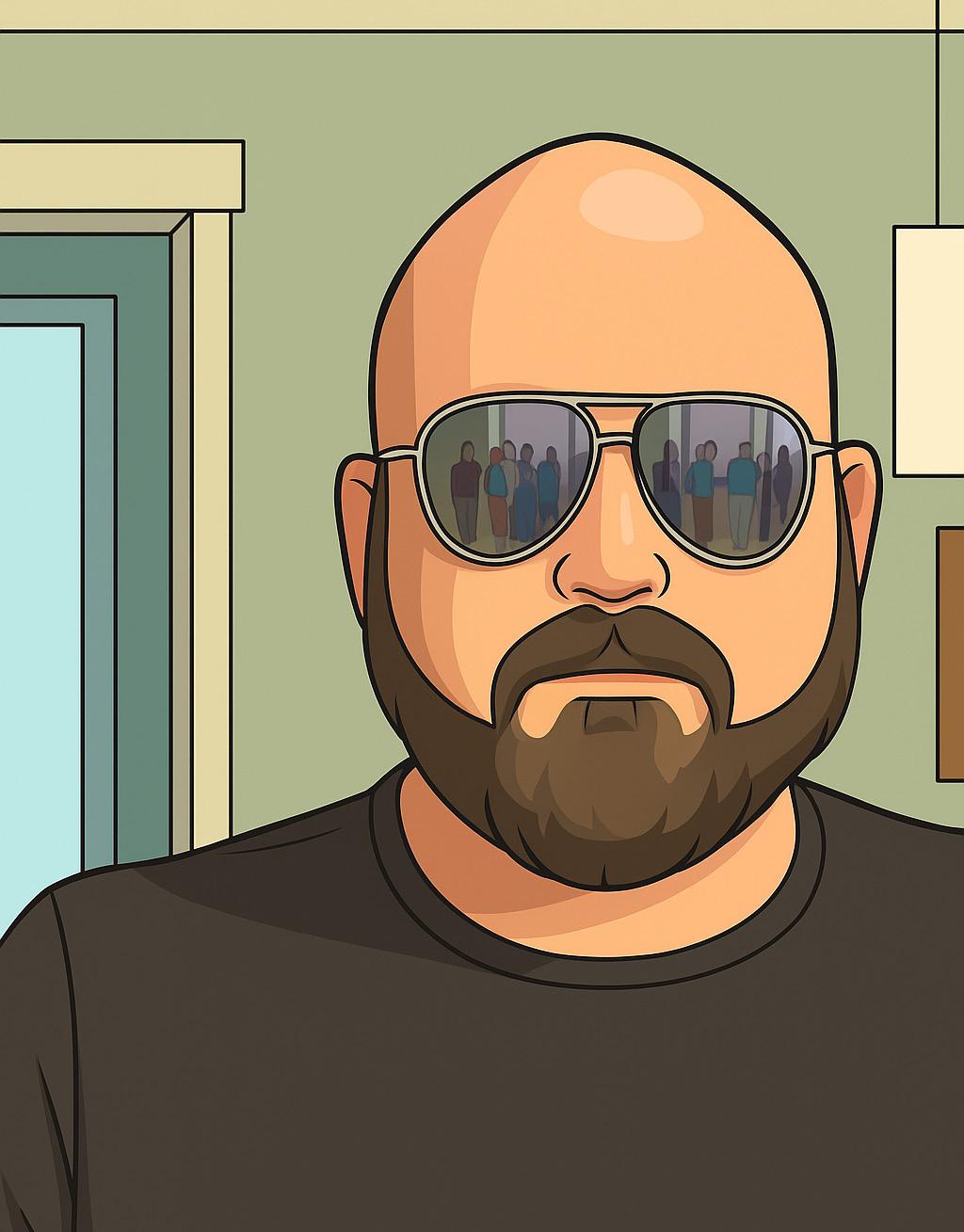

ALLEN LOIBNER-WAITKUS smokes and says “shit” a lot.