UNFIXED ECOSYTEMS

The Problem to solve is __________________

Table of Contents

1. Ecological Identity (1-3)

2. Queering Ecology (4-5)

3. Fermentation and Observation (6-7)

4. “Hybridity” and modernity (8-9)

5. Transfiguration and Monsters (10-11)

6. Reclaiming Aberration (12)

ECOLOGICAL IDENTITY

Despite all the connotations of objectivity we associate with the natural sciences, even empirical data comes with its own narrative. Who decides what counts as data, and how it is sorted? Countless stories guide us through our daily observations and subsequent choices, and our narratives about who we are (or who we want to be) create a framework for decision making, just as our biological needs and sensory inputs do.

Our ecology is not objective fact but a blend of observation, mythology, and aspiration. What questions does this ecology seek to answer?

Ecology tells the story of relationships. Ecology is about our collective situation. It tries to tell us - all of us, all organisms - who we are to each other, and how we matter.

In many ways, the construction of humanity is far more than a taxonomical project; more than just a separate category of creature, to be human is not an observation but a prescription. In mainstream American culture, to be human is to aspire towards a certain perfection, despite humanity being somewhat synonymous with imperfection - we are “only human” after all.

To be human or nonhuman, natural or unnatural, animate or inanimate - all of these dichotomies are embedded with a sense of consequences, often moral rather than practical. Take for example terms like “humane” or “subhuman”. We can expand this to taxonomies of gender, sexuality, and race, all of which have used biological mythologies to justify discrimination.

For all the subtleties, nuances, and hybridities of real life that such ecological narratives deny, it becomes necessary to queer our understanding of ecology. To account for hybridity is to allow ourselves to inhabit the present.

© piotrwzk/Shutterstock.com

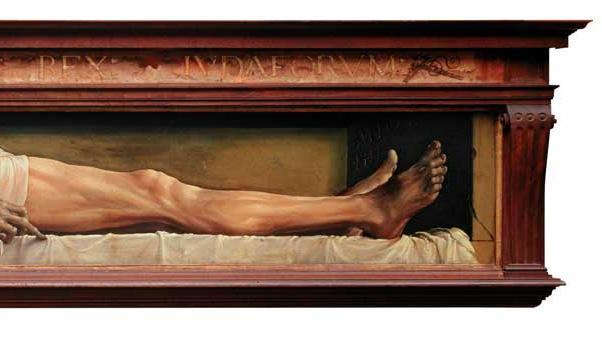

The simultaneous pathos of this figure and the direct interrogation of Christian faith it invokes captured the fascination of Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky, who was caught in a constant negotiation of rationality and faith.

In his writings, pious characters aggressively confronted Christian faith with subversion and negation, in hopes of finding, on the other side, an unshakeable faith to coexist with reason.

Holbein’s Christ, however, carries no such promise. Here, in the coffin, time is frozen. Christ is defined by mortality - all of the rigidity and imminent decay of human death contrast this religious figure with the brutality of mortal time. The gravitas of Christ’s death, here, is the consequences it has for those who would depend on him.

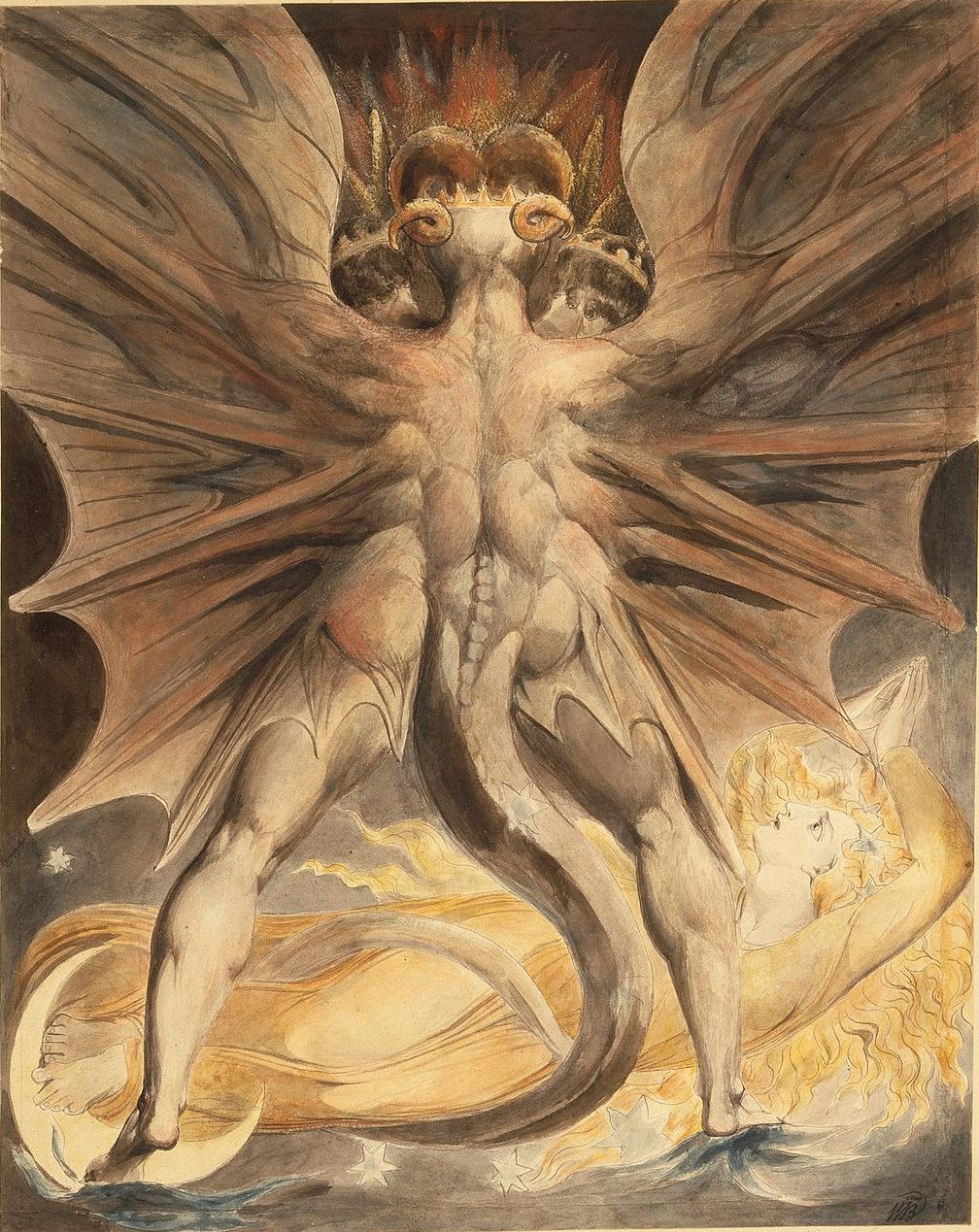

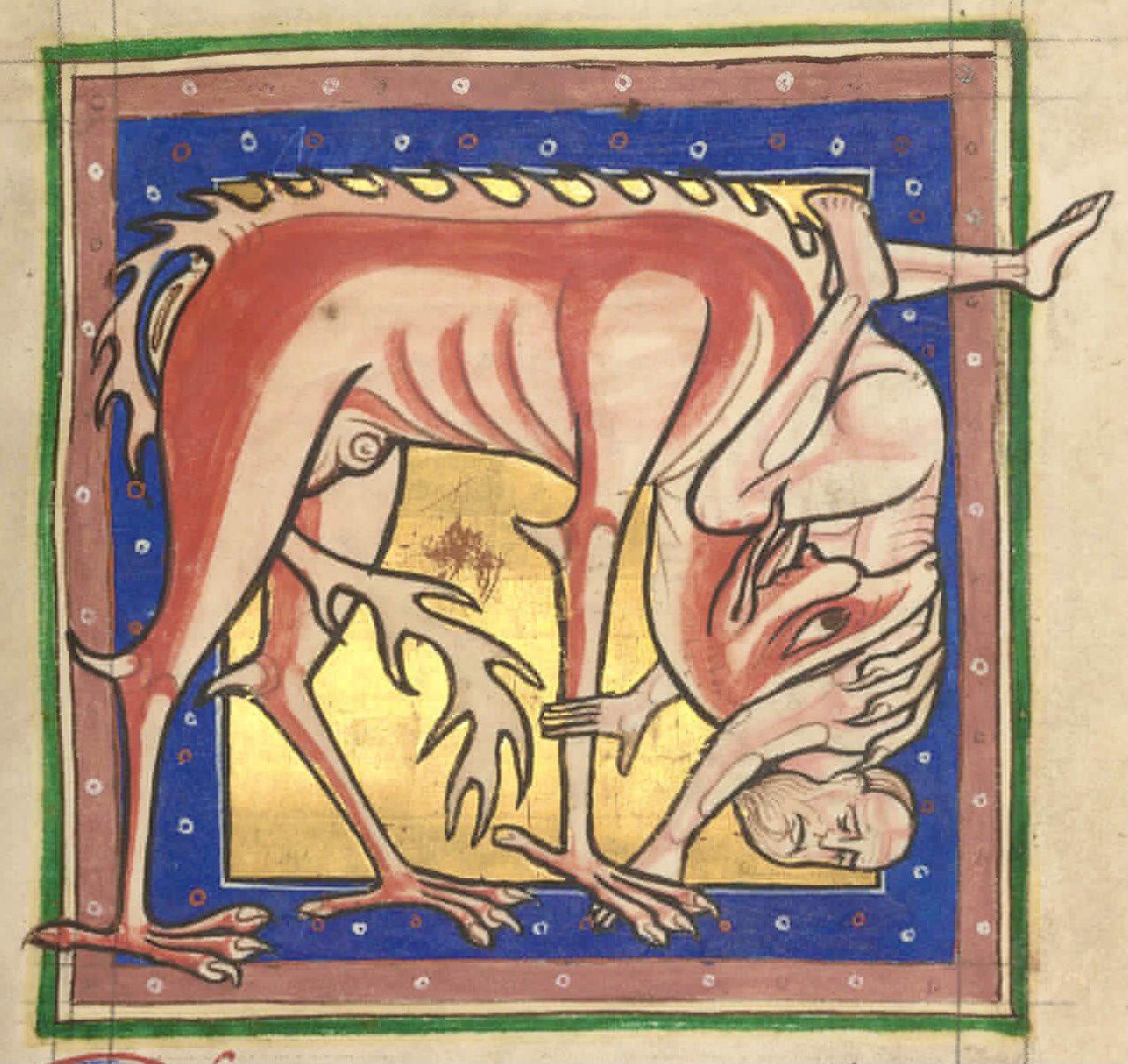

Certain ideas of sophisti cation and modernity are not compatible with the messiness of monsters and ferments. Something is either clean or dirty; it is safe or dangerous; it is good or bad. There is no place in the world for a monster. Not quite a creature and not quite a villain, what the monster threatens more than our safety is our comfort and stability. The monster defies intelligibility, the monster rebels against the laws of nature.

Queerness as a concept has its origins in subversion. The inversion of typical rules and the transgression of typical boundaries are actually fundamental to scientific progress; such subversions reveal to us our existing perspective’s inability to account for all of reality. As such, there are many overlapping frameworks for trans-ness and ecology. The hybrid existences we encounter in reality subvert such expectations of naturalness or purity that we have invented in an attempt to canonize traditional narratives about what life on earth must look like. The concept of crossing boundaries – to transgress – is predicated on the belief in the reality of those boundaries in the first place.

What I am hoping to suggest is that perhaps, what we take for granted can mislead us. We use stories to understand the world – stories are beautiful, and are helpful – but we cannot forget that stories are ultimately only an interpretation of things, and not truth. Taxonomy offers relief from chaos. It offers the elusive possibility of truth. Furthermore, the security of categorization comes at the expense of our expansiveness, complexity, permeability, and freedom.

In his 1962 essay The Creative Process, James Baldwin writes about the role of the artist in unmasking: to make the unseen visible again is to remind us of what we have taken for granted in order to function on a day to day basis. But as Baldwin writes, “A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven. One cannot possibly build a school, teach a child, or drive a car without taking some things for granted. The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.”

Whale fall is an example of how life and death exist simultaneously, within one another, and in a perpetual cycle of necessity. A body becomes an ecosystem, challening our preconceptions of death as static, or as a loss or disappearance. Instead we see transformation as a constant.

There is a kind of love and patience in observation that does not rely in categorization. In her Manifiesto Ferviente, Mercedes Villalba asks us “not to distinguish strains of life but to recognize its presence and consequences.” She writes that “Fermentation trains us in seeing the ground as inherently shaky. It makes visible the invisible potential of those things that seem still.” much like Baldwin’s artist, the ferment asserts that the only constant in life (and death) is change. The tastes, smells, and textures of fermentation, which Villalba says late liberalism has trained us to see as “signs of decay and disease” cannot be reduced to rot; ferments are dynamic, bursting with life and flavor.

Deep sea hydrothermal vents spew out hot mineral fluids which mix with near-freezing seawater in these deep sea ecosystems. Some think they are among the most promising locations for life’s beginnings.

Certain ideas of sophistication and modernity are not compatible with the messiness of monsters and ferments. Something is either clean or dirty; it is safe or dangerous; it is good or bad. There is no place in the world for a monster. Not quite a creature and not quite a villain, what the monster threatens more than our safety is our comfort and stability. The monster defies intelligibility, the monster rebels against the laws of nature.

to exist, it is 12th century, English. via @WeirdMedieval on X

Bruno Latour

argues that while distinctions (e.g. natural/unnatural) enable “modernity” untenable because our world is primarily composed of hybrids

Transfigurations and Monsters

In the ancient Greek myth of Daphne and Apollo, the nymph Daphne tirelessly flees from Apollo’s amorous advances. Eventually, in her desperation, she prays to be transformed into another form - something unrecognizable, which will no longer tempt Apollo into pursuit. Changing into the Laurel tree offers Daphne a simultaneous rebirth and escape. Metamorphosis is a consistent theme in Greek mythology, which offers explanations of how the world came to be. Frequently, people are turned into various trees and flowers.

© piotrwzk/Shutterstock.com

Reclaiming Aberration

Queer and trans communities commonly encounter accusations of being “unnatural” (despite plentiful evidence in nature of fluidity in sexuality and gender). So, to be unnatural is an admonishment - to “fail out” of humanity marks what is queer to be less-than, an abomination. To be queer is to exit the hierarchy and lose its protection; we become marginalized. To queer ecology, to me, is to flip the power dynamic: rather than taxonomy labeling what is “queer” and marginalizing us, we must transgress the boundaries of existing taxonomy, push its limitations, and revolutionize it. Transfigurations and metamorphoses can be both frightening and exciting. A journey into the unknown brings new possibility; mythologies of transformations between human and nonhuman remind us of the fragility and specificity of our human existence. Change is fertile ground for possibility. Just as life can flourish in death and beauty can exist in decay, we all embody the range of violence, tenderness, beauty, and ugliness which exists in the world. Perhaps it is not so scary if we consider that such complexity is only natural.

Designed and written by Aliza Katzman in Adobe Indesign

Printed by Park Slope Copy Center

March 2024, Brooklyn, NY

on 70 lb text weight paper in an edition of 200

When we realize the subjectivity of these boundaries, we can accept the permeability between life and death, joy and loneliness, human and nonhuman, and in doing so regain what we have assumed is lost in remaining undefined.

Created as a part of the 2024 Pratt Institute Fine Arts

MFA Thesis exhibition Unfixed Ecosystems, curated by Alex Santana

Sincere thanks to my thesis advisor Michael Brennan, and to Amanda, Imogen, and Henry for all of their humor, good company, and sound advice. Thank you to Angie, Justin, and Jimmy for all of their patience and support. Thank you to Miriam Schaer for teaching me how to make zines, and thank you to YOU for reading this one!

You can find me at www.alizakatzman.com on instagram @alizakatzman or email me at aekatzman@gmail.com Edition /200