Reflections on the Project

The following is a transcript from a conversation our class had about the project. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Aliza: How did you feel during the project, and what do you feel like you learned?

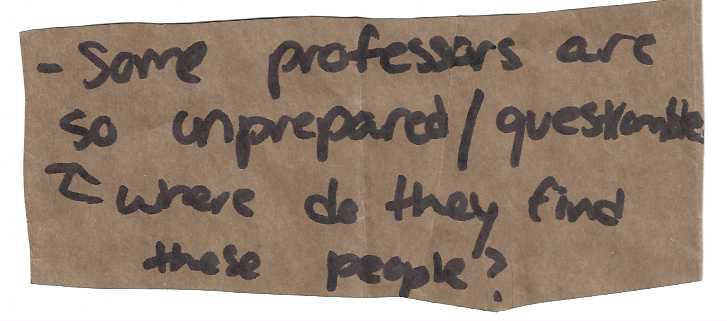

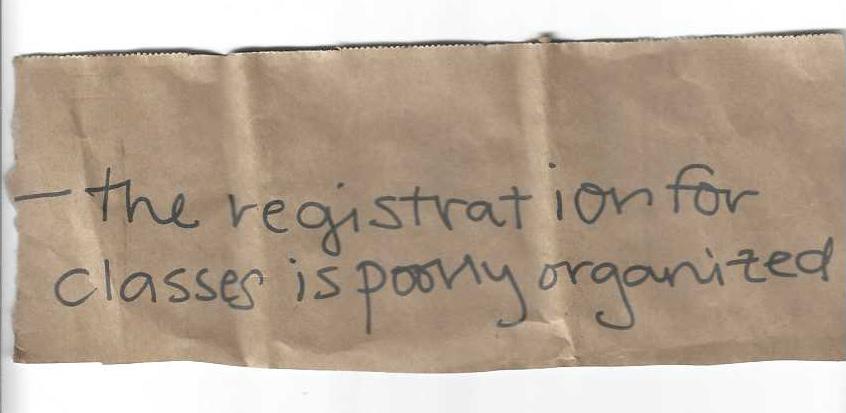

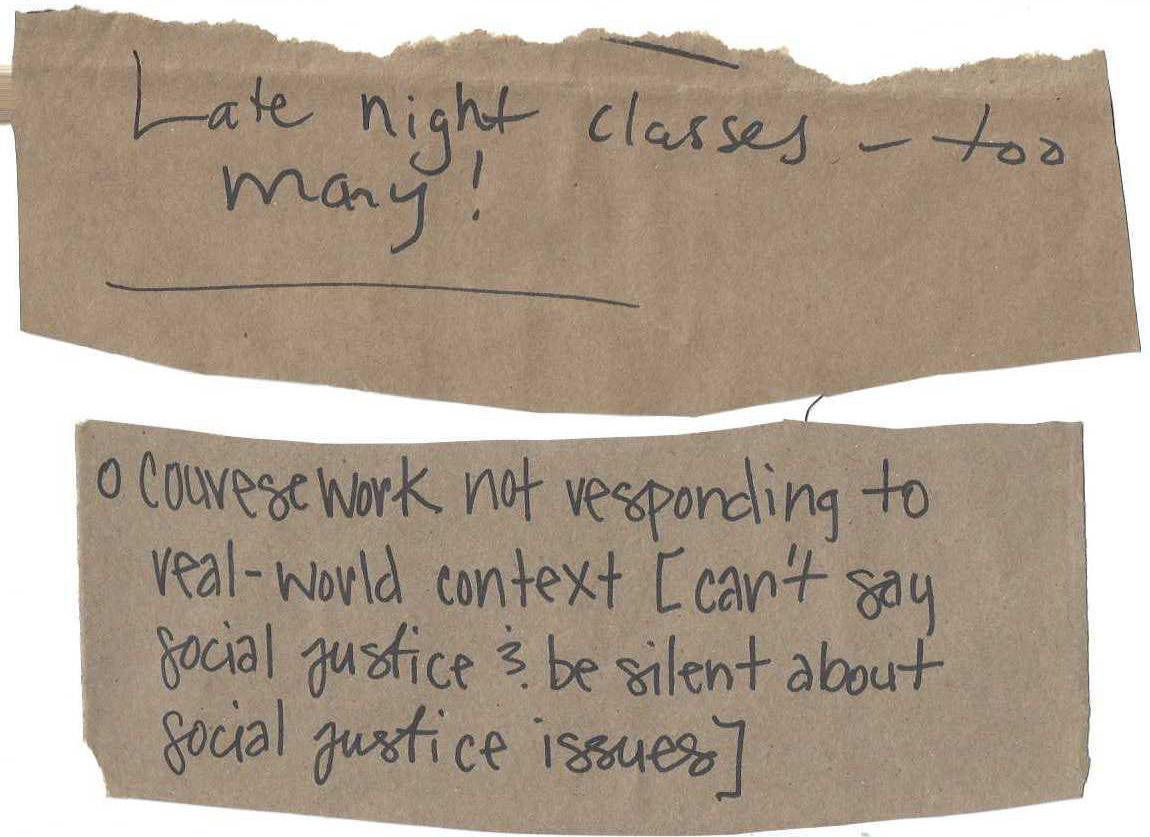

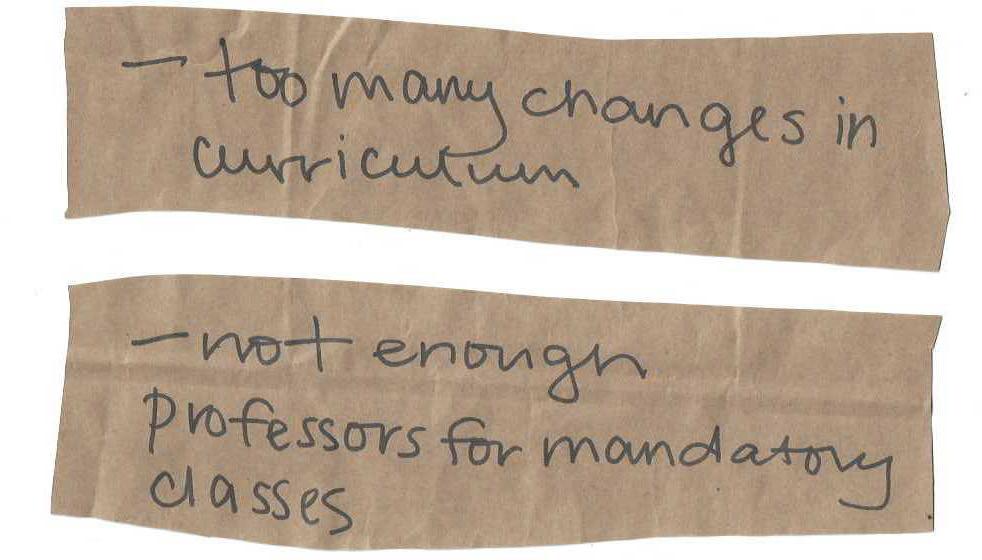

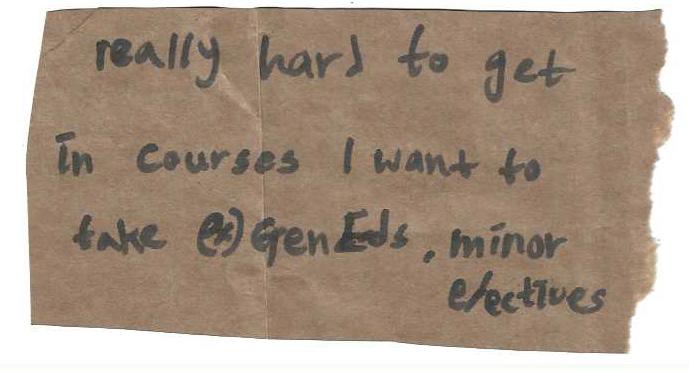

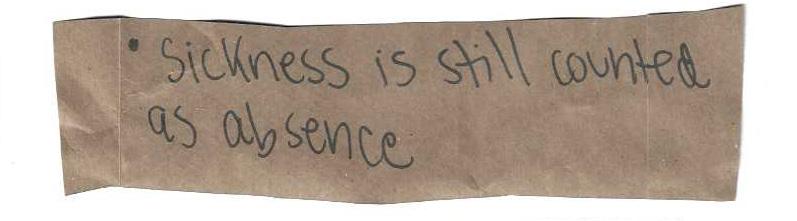

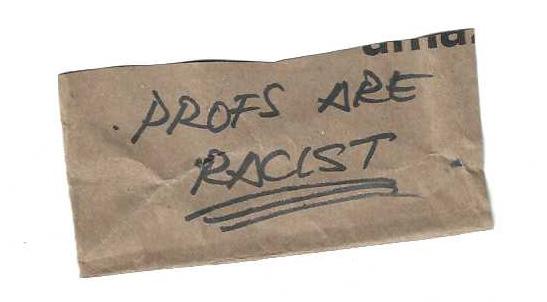

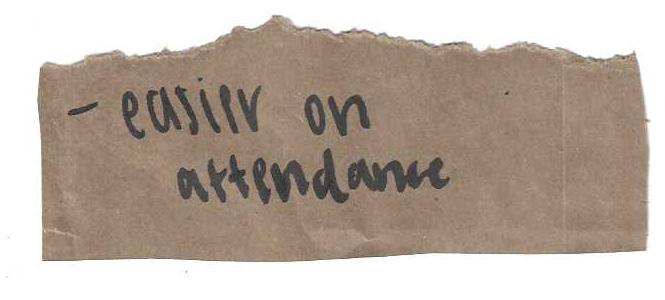

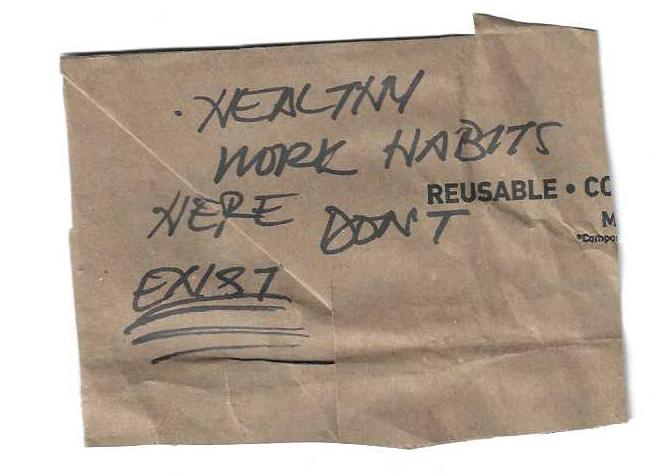

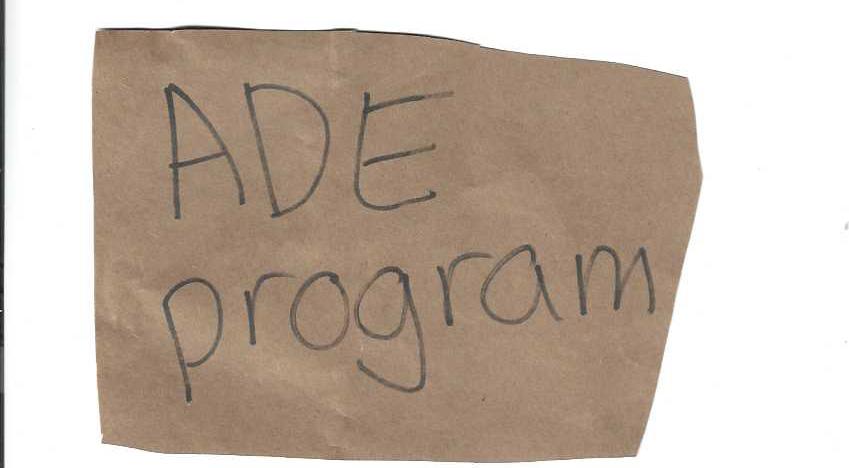

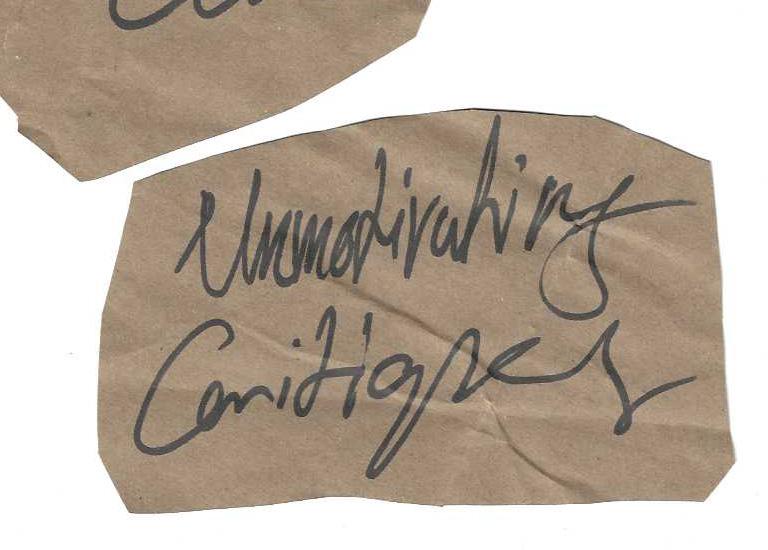

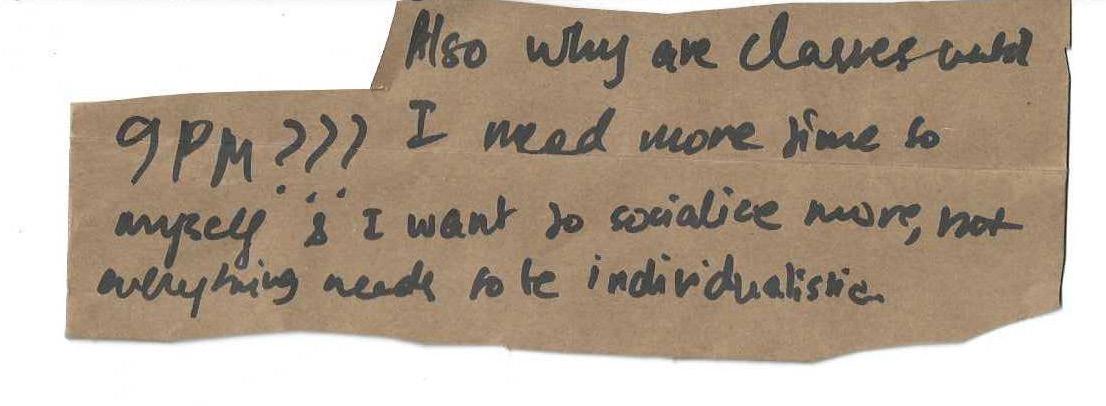

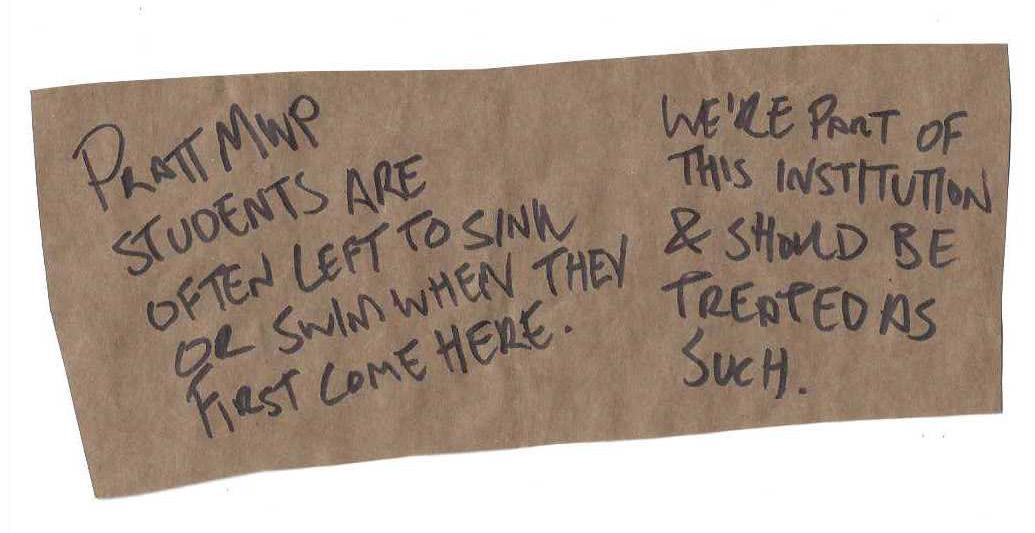

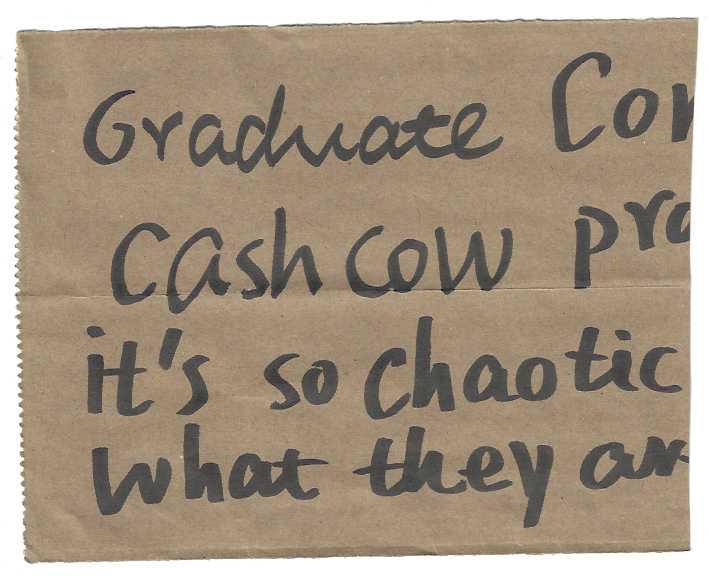

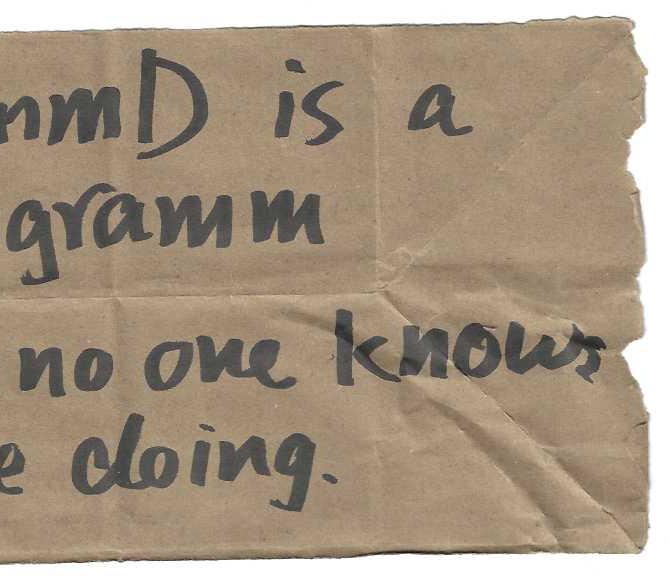

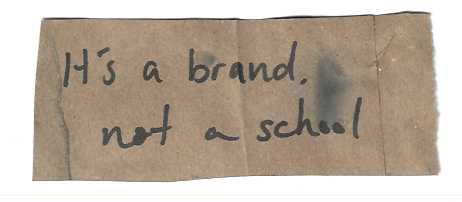

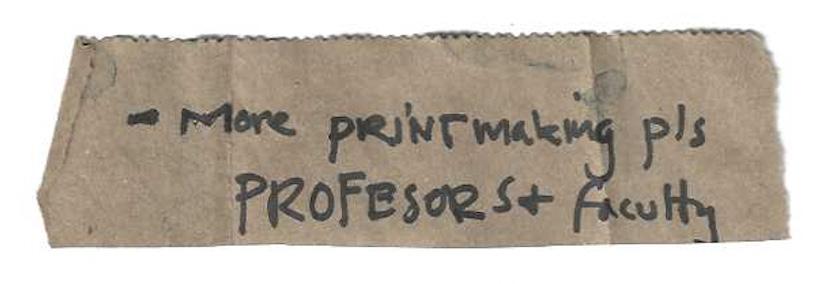

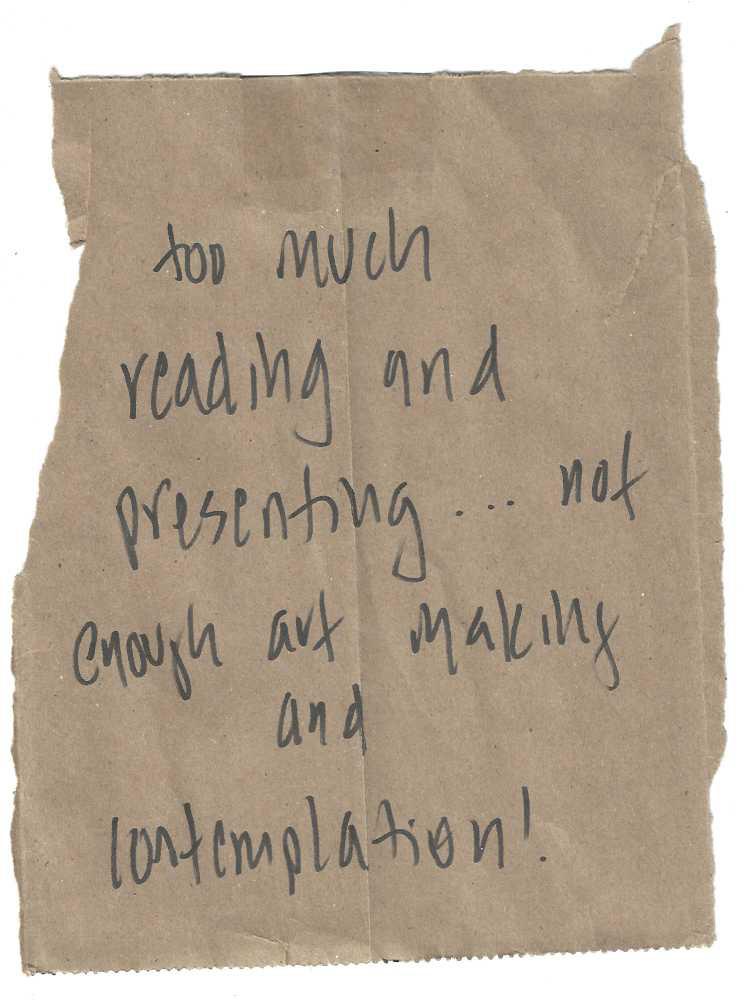

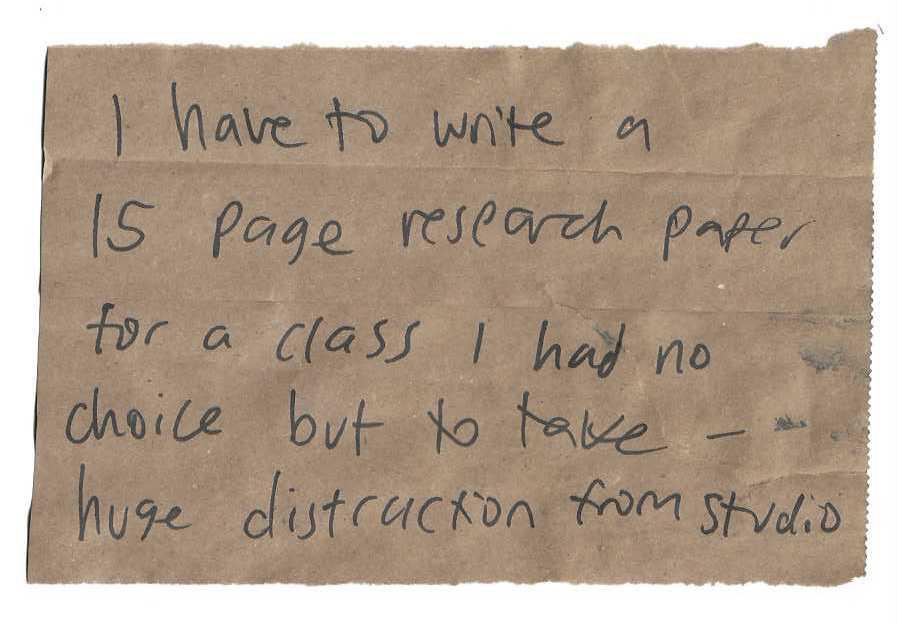

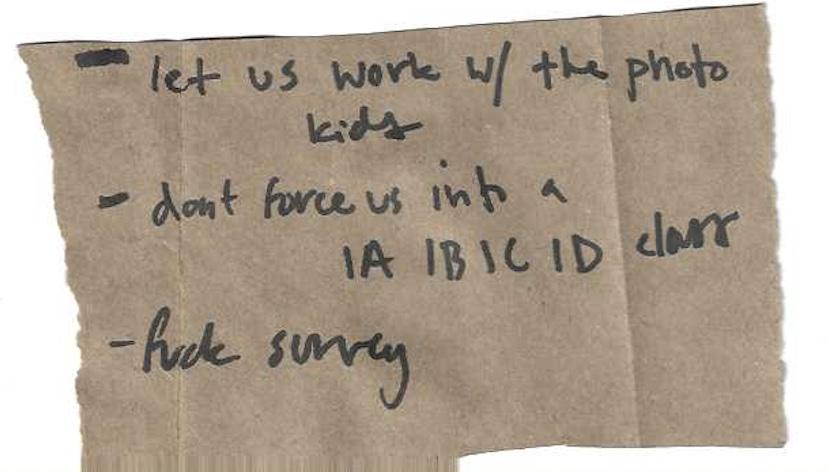

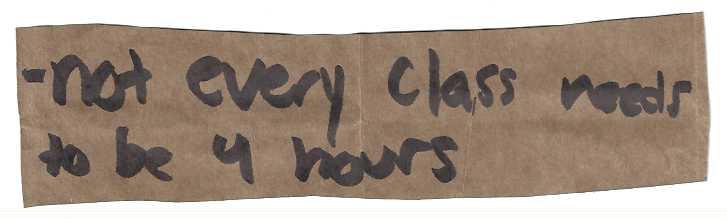

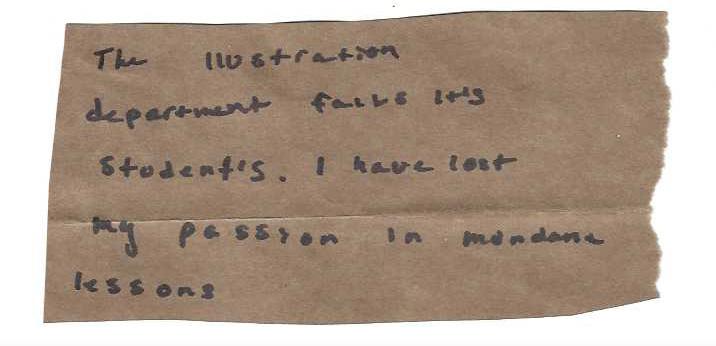

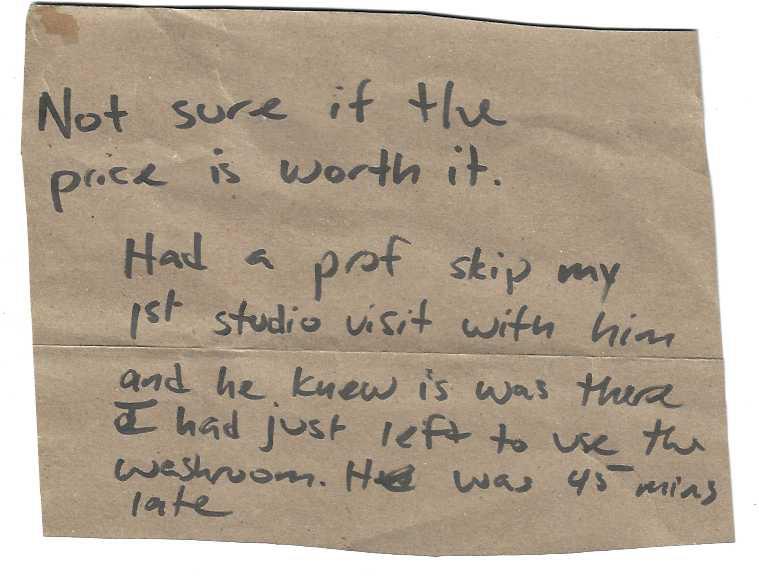

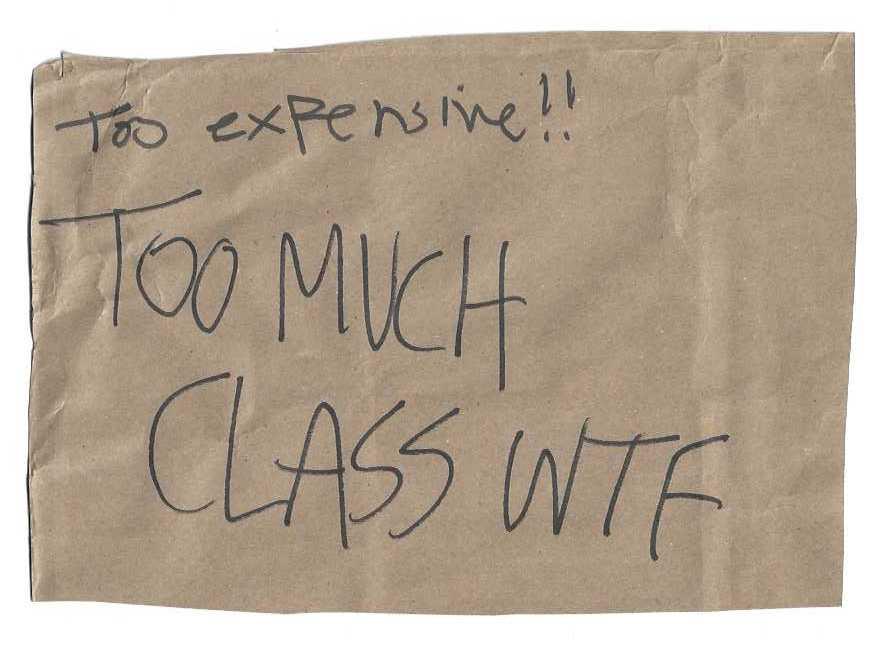

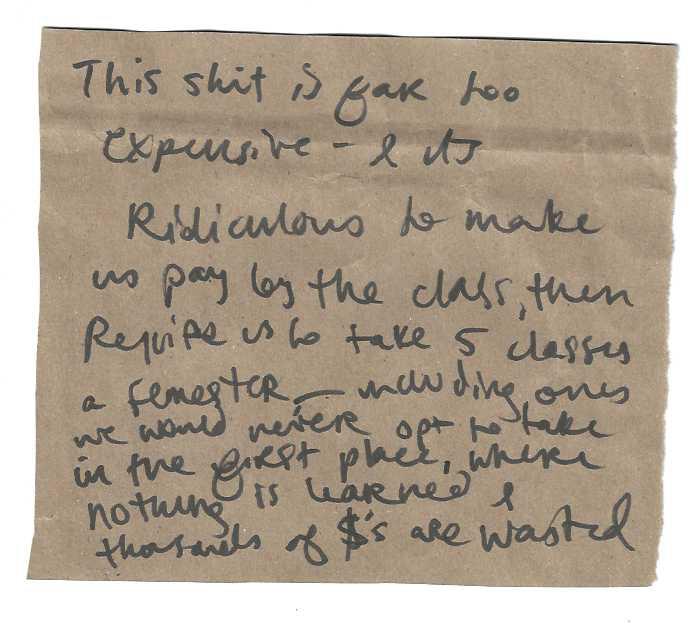

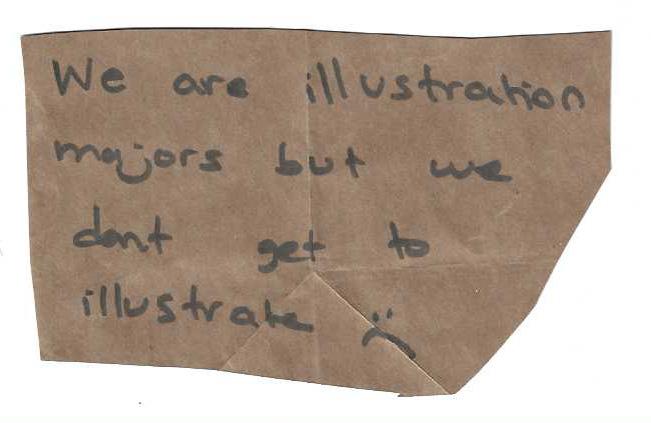

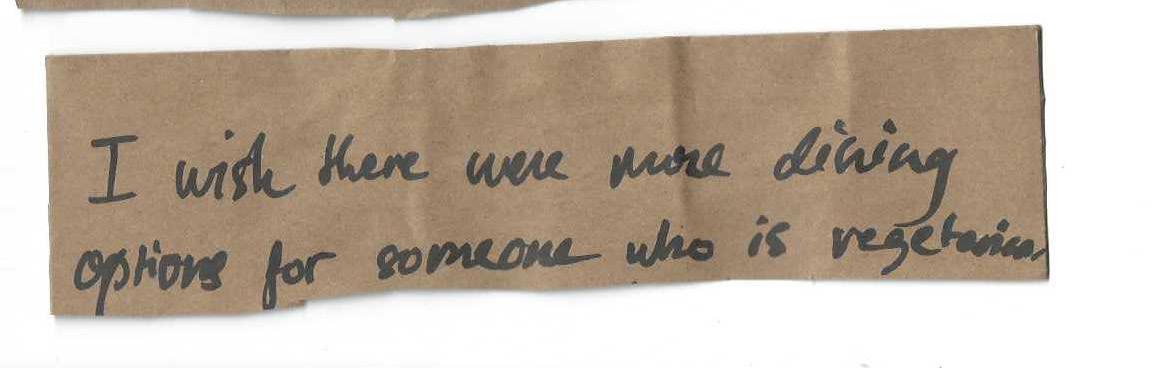

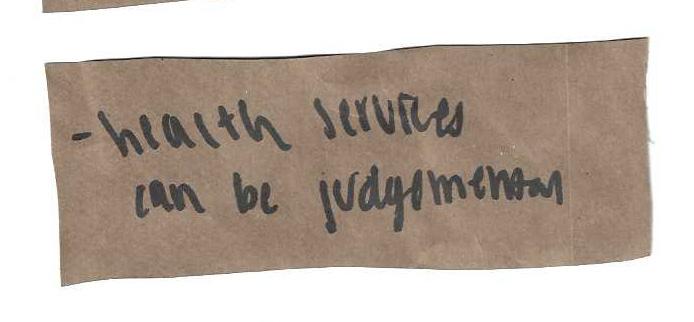

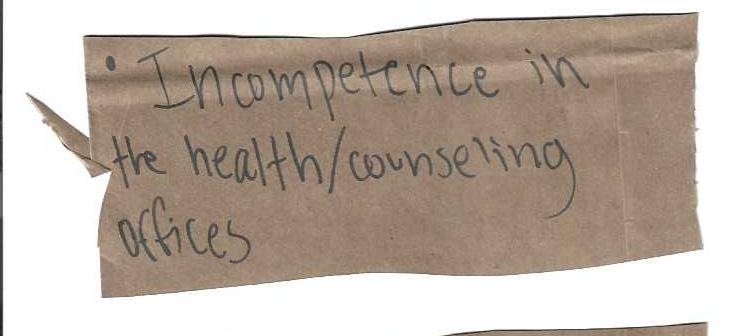

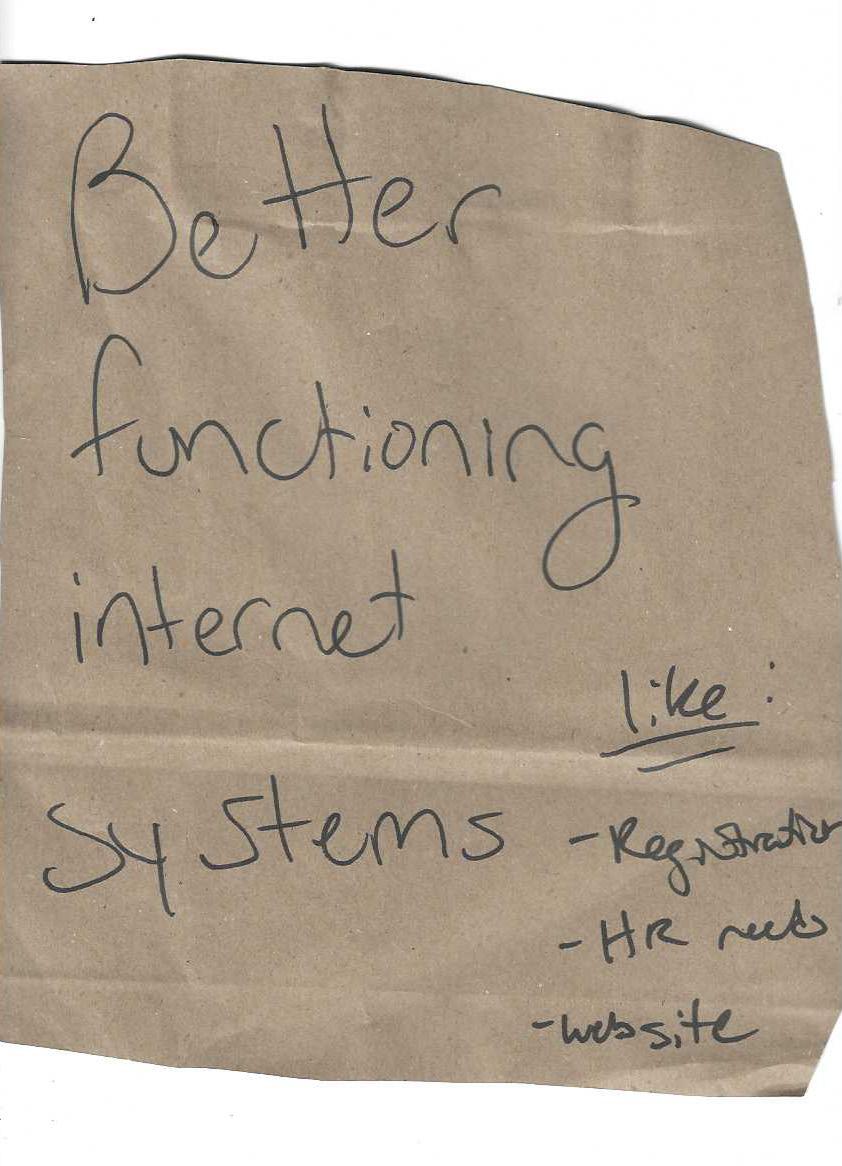

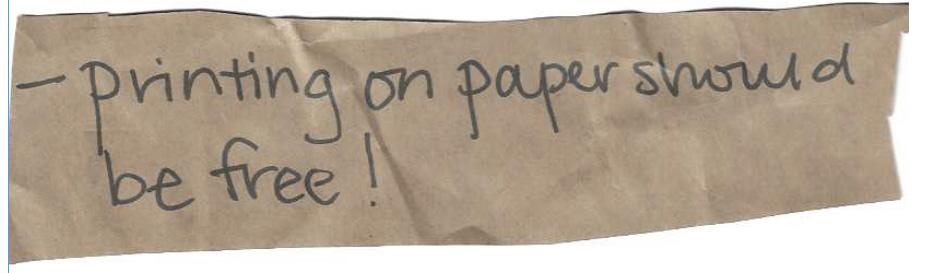

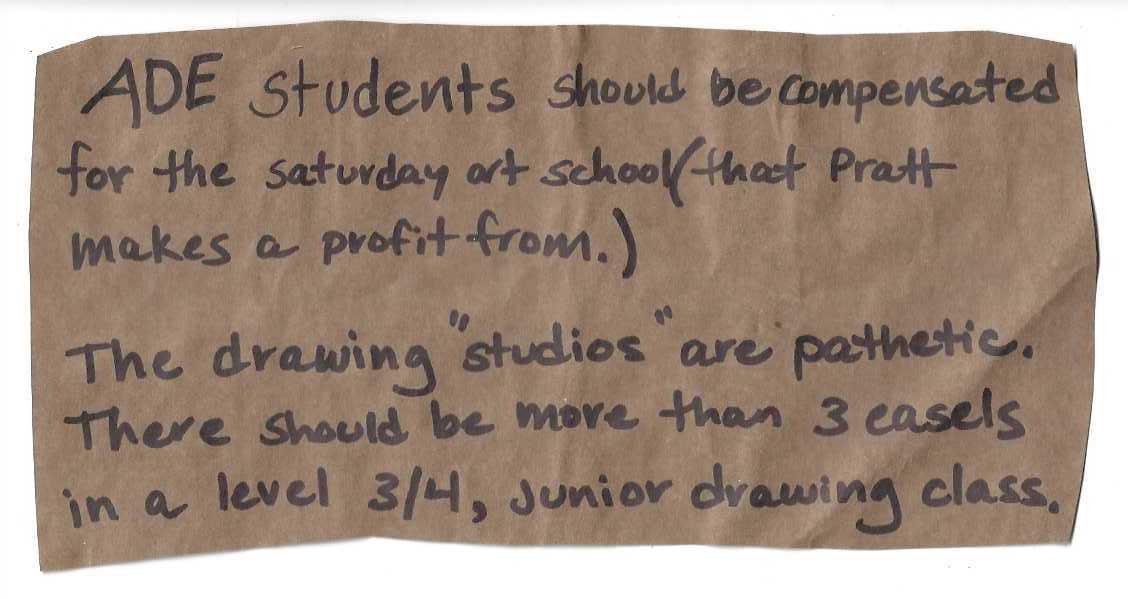

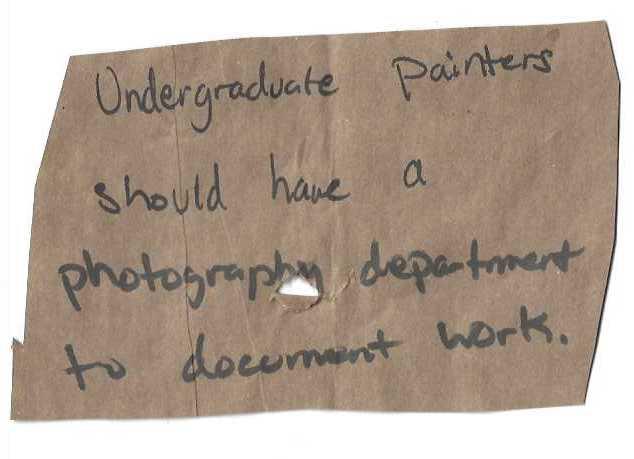

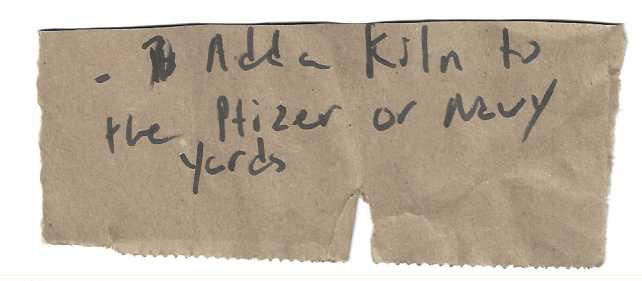

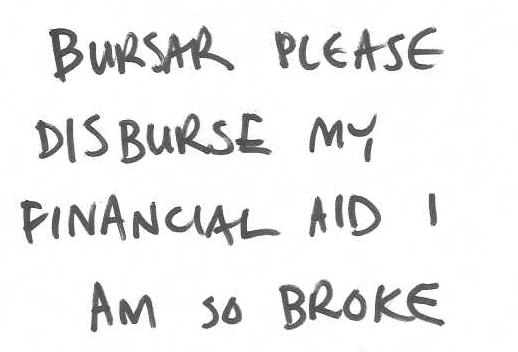

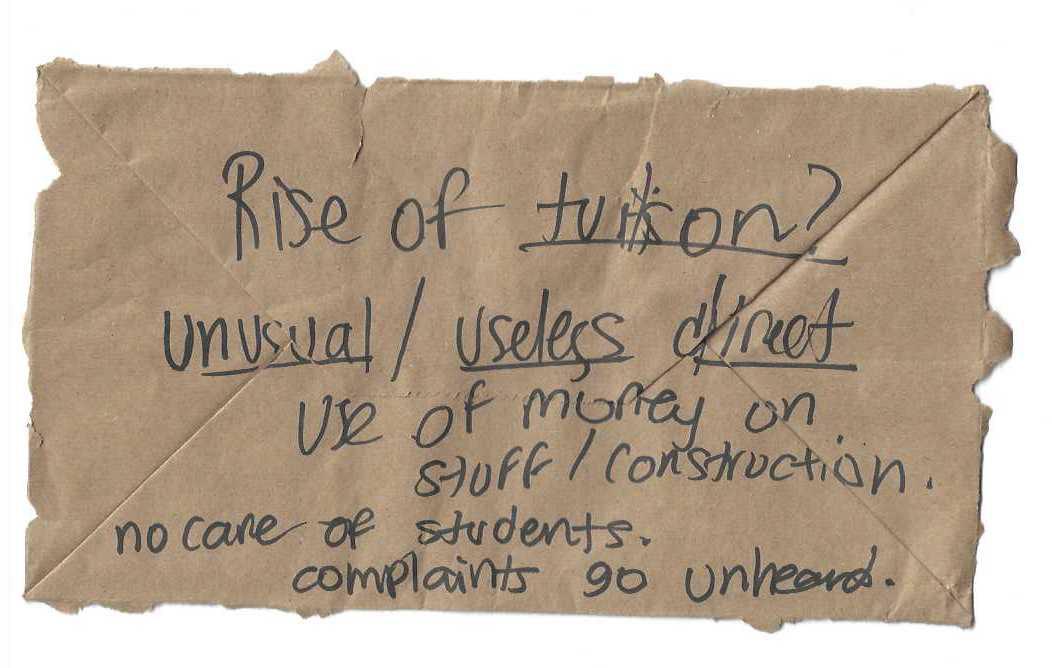

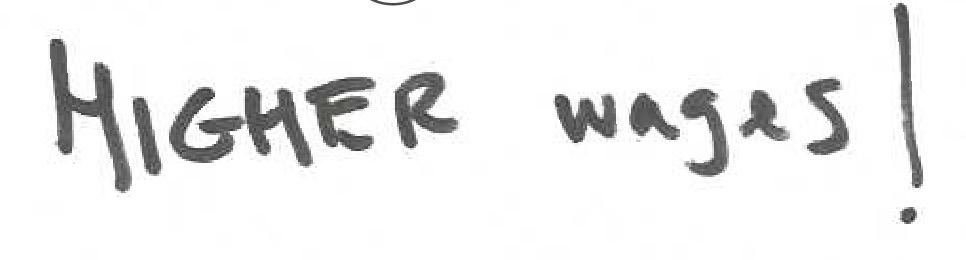

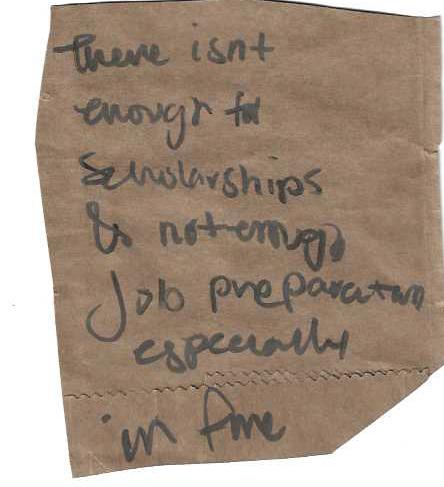

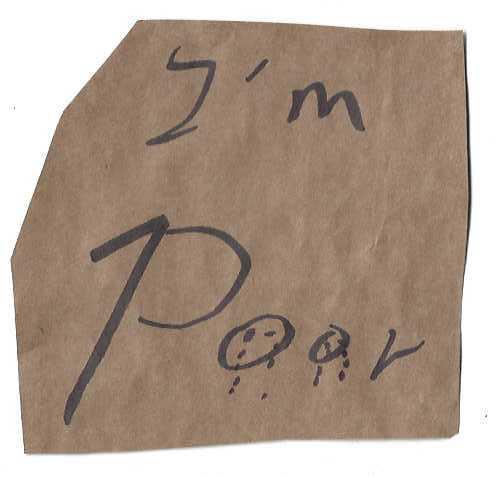

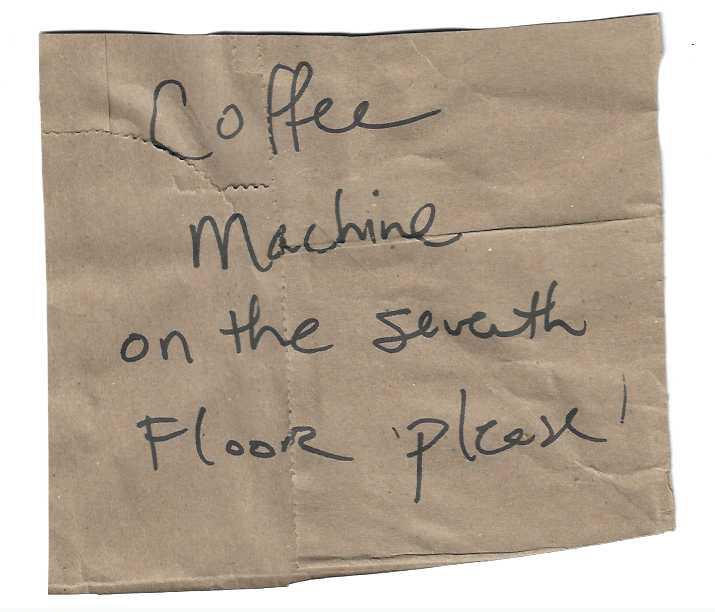

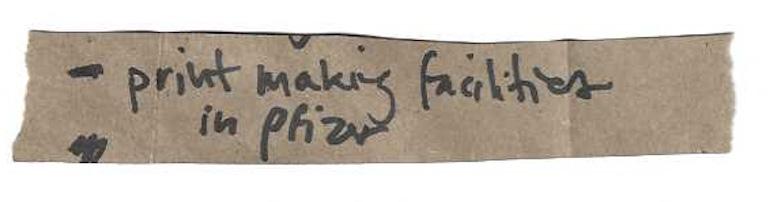

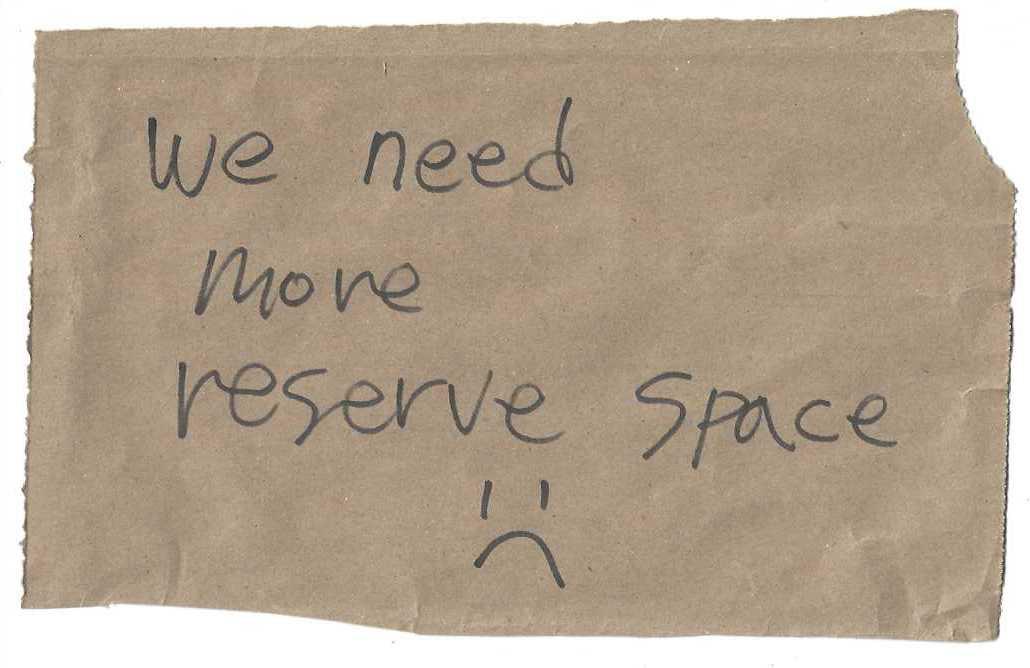

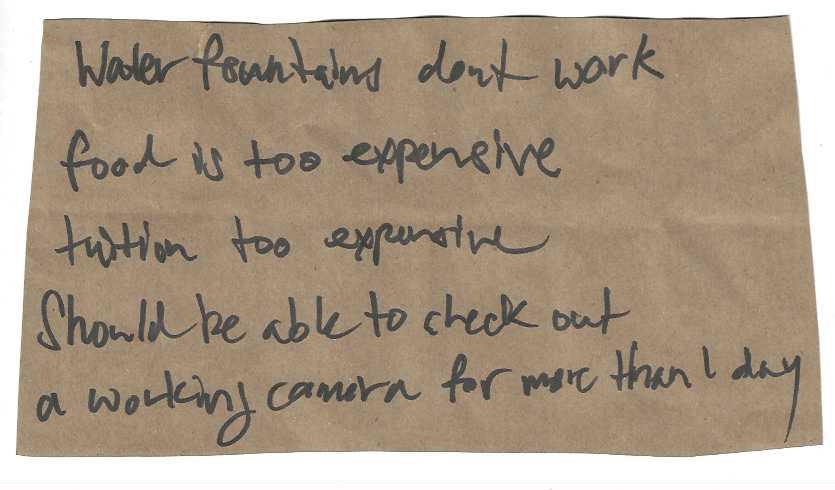

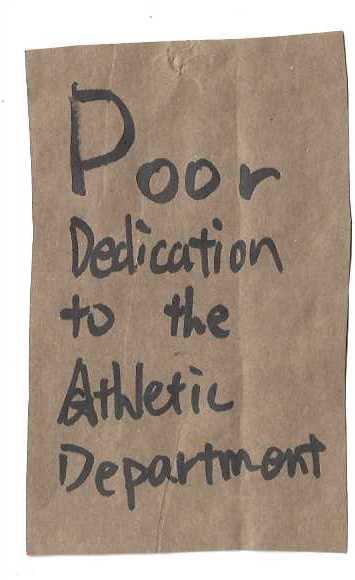

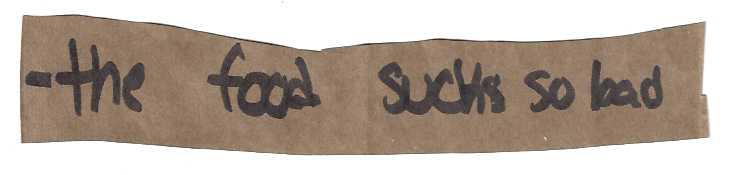

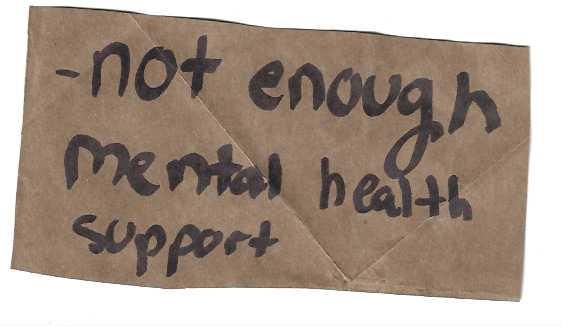

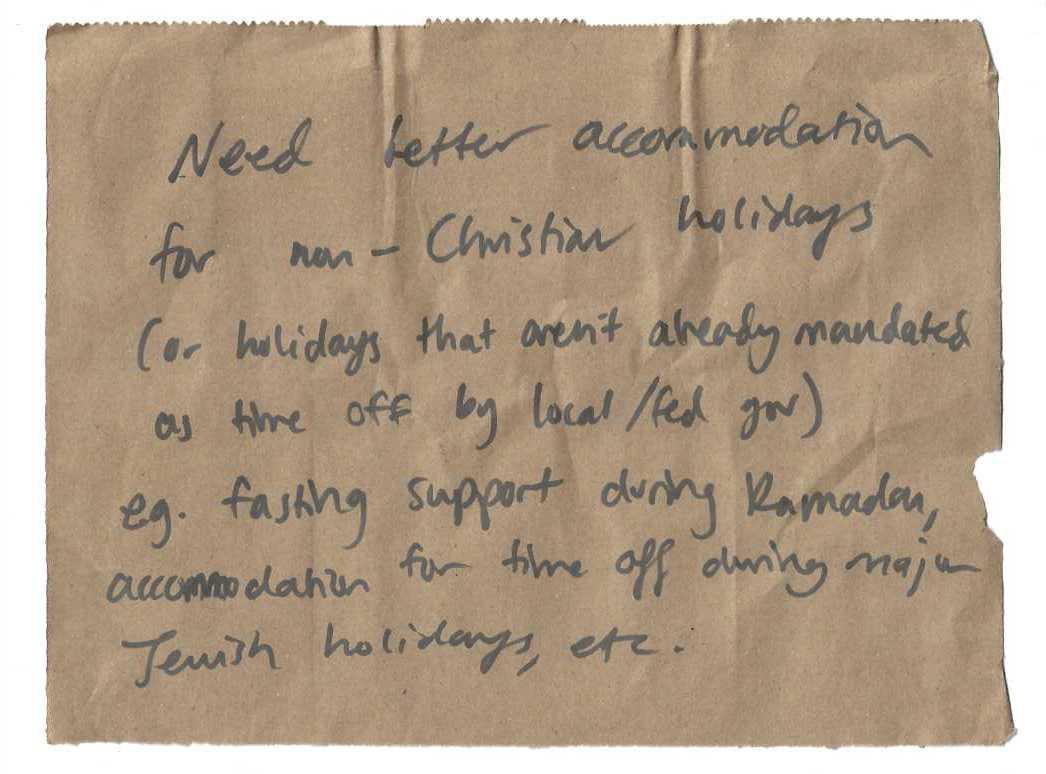

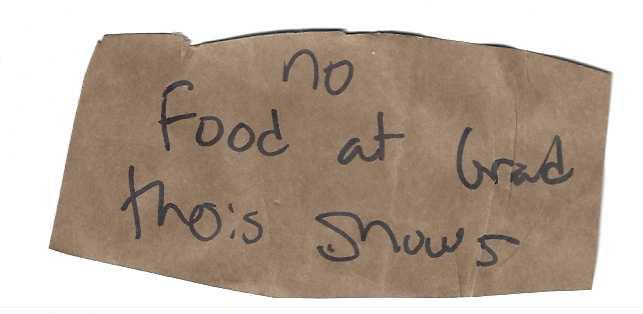

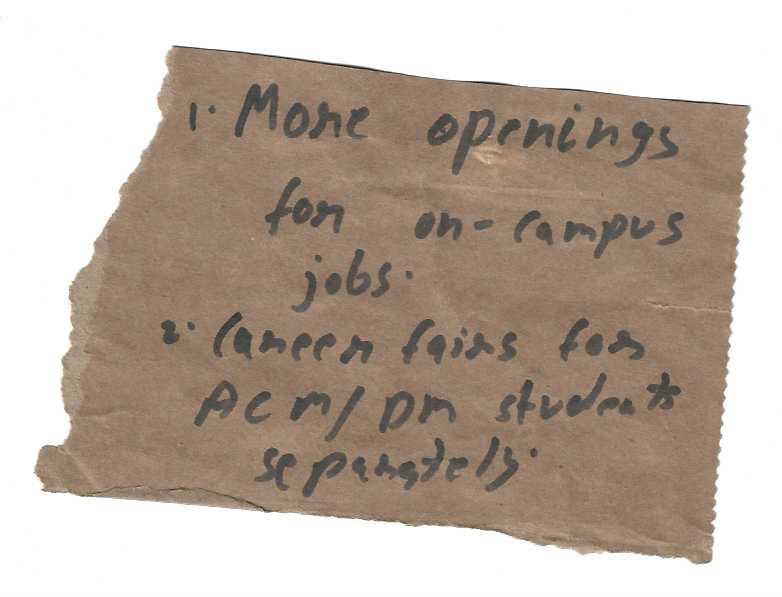

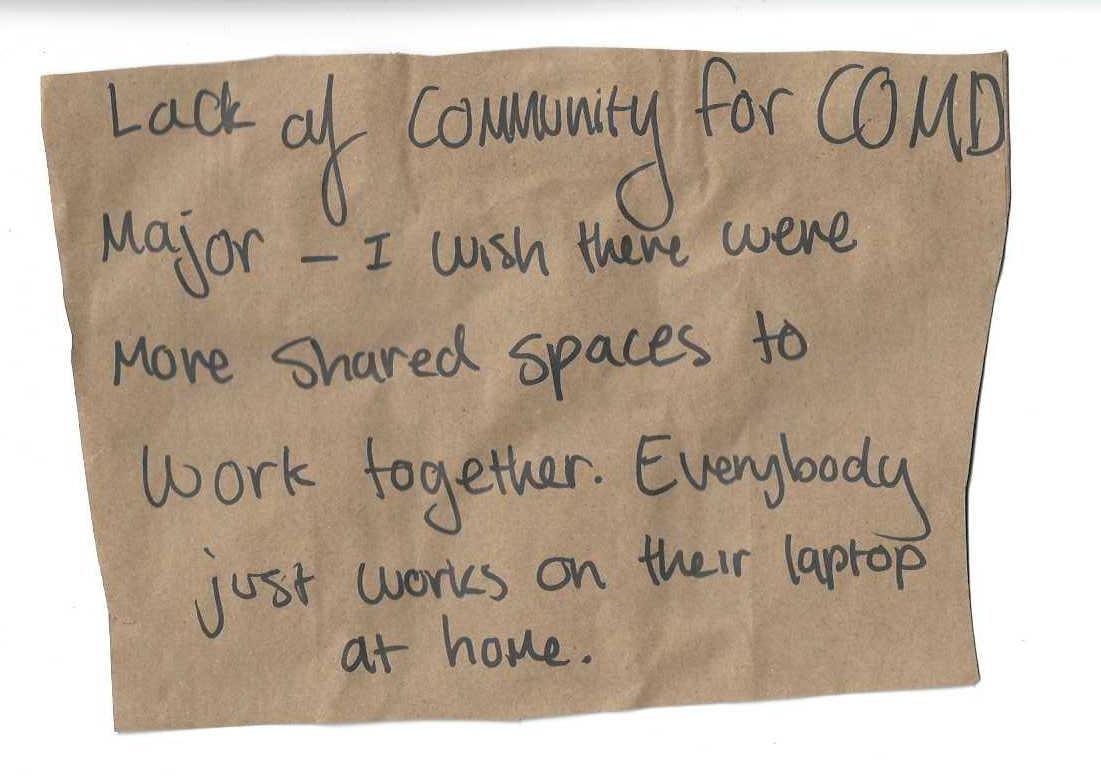

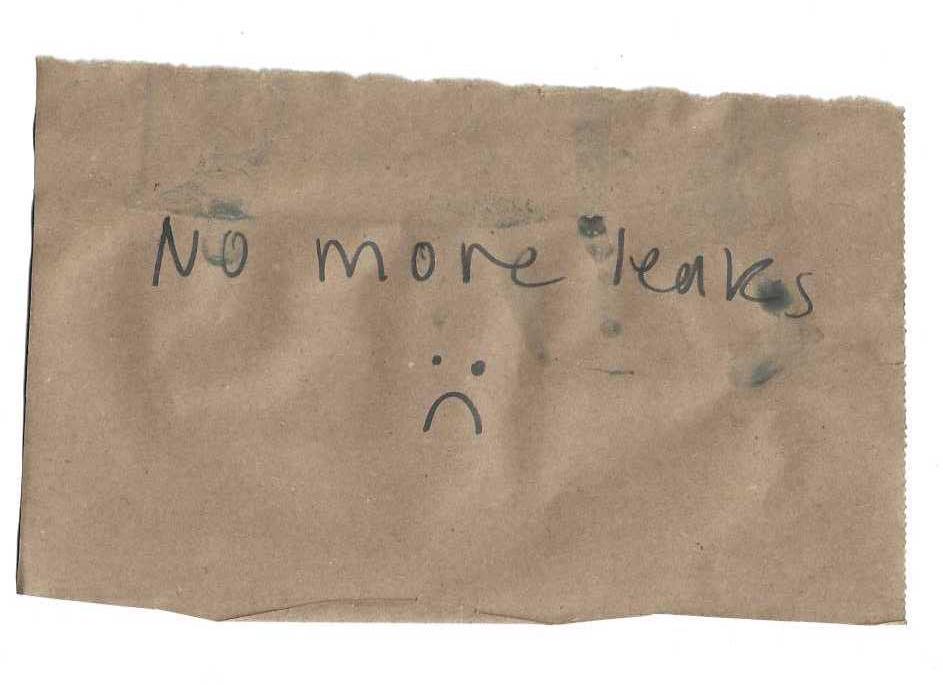

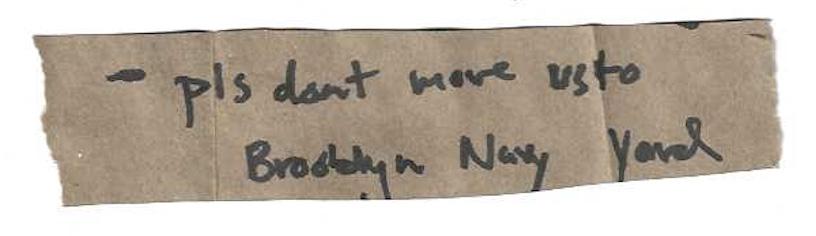

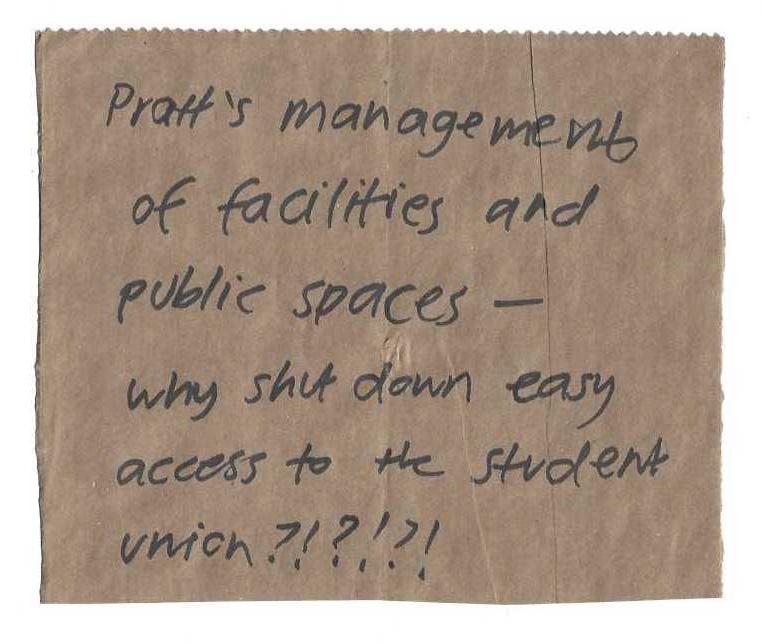

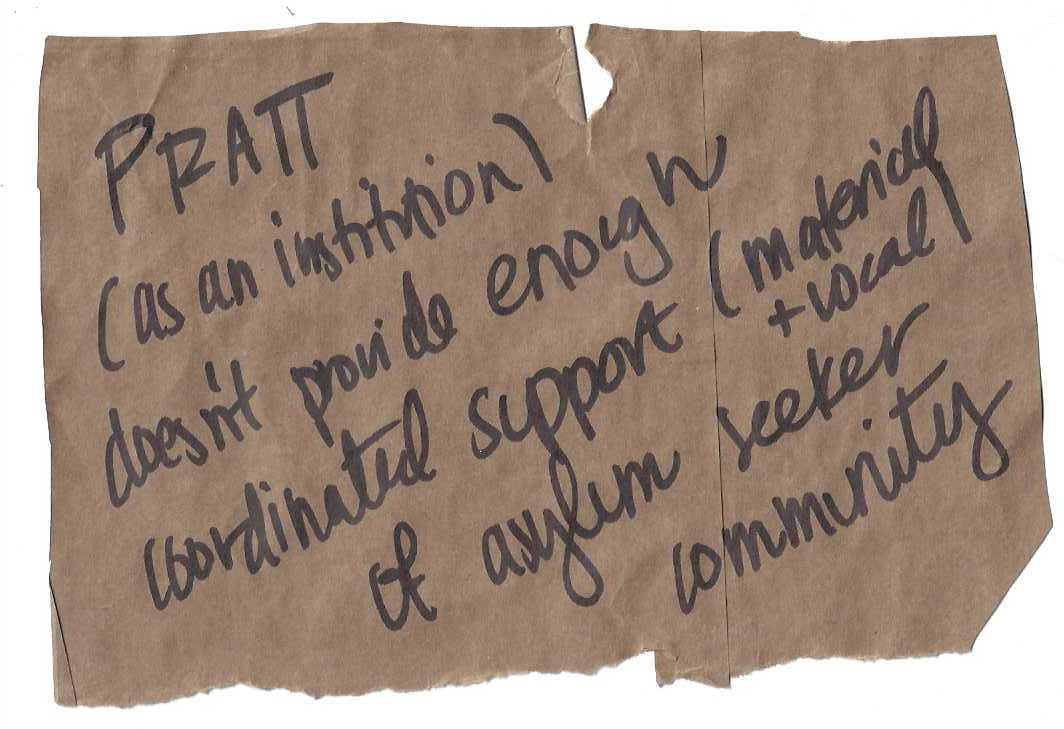

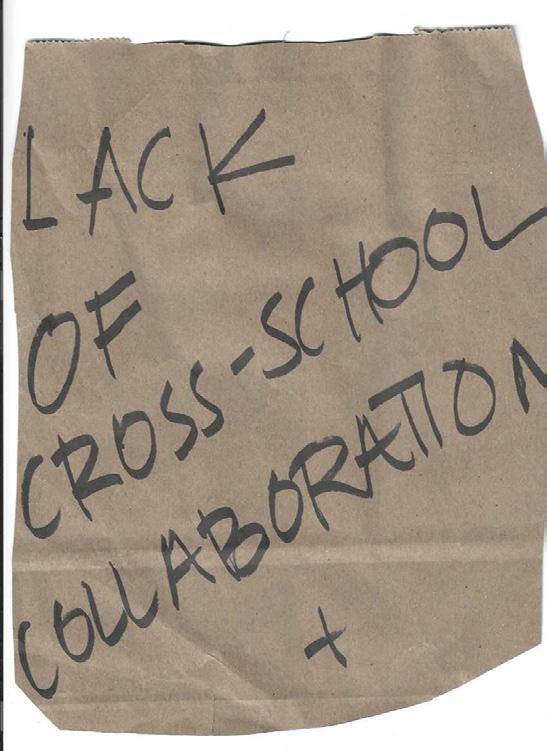

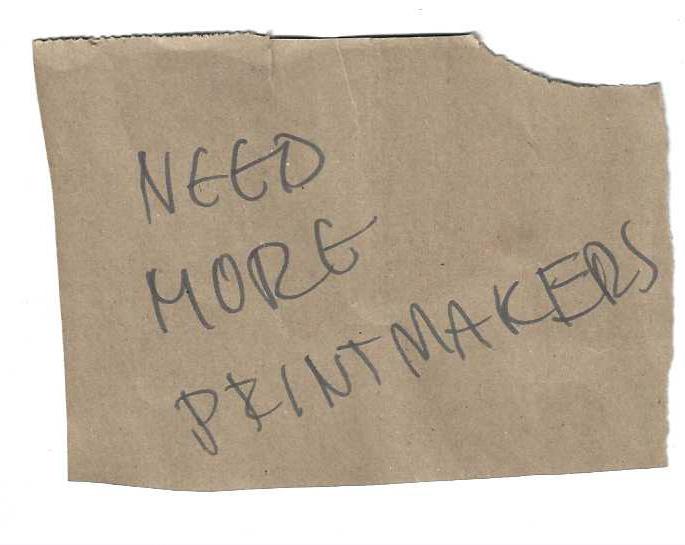

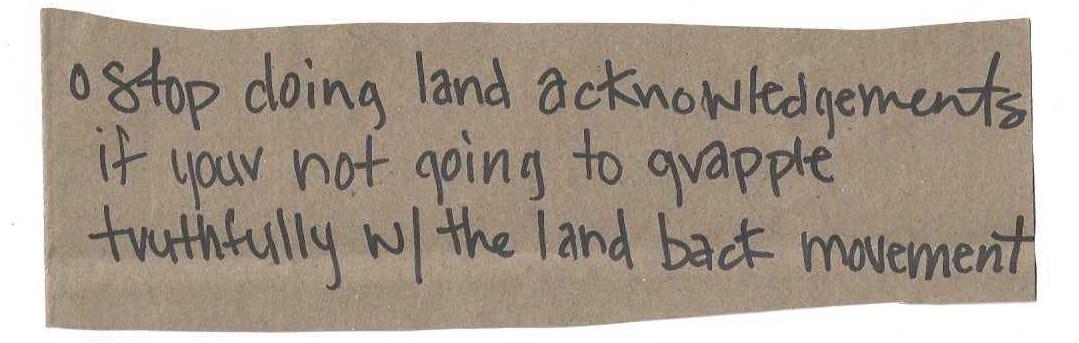

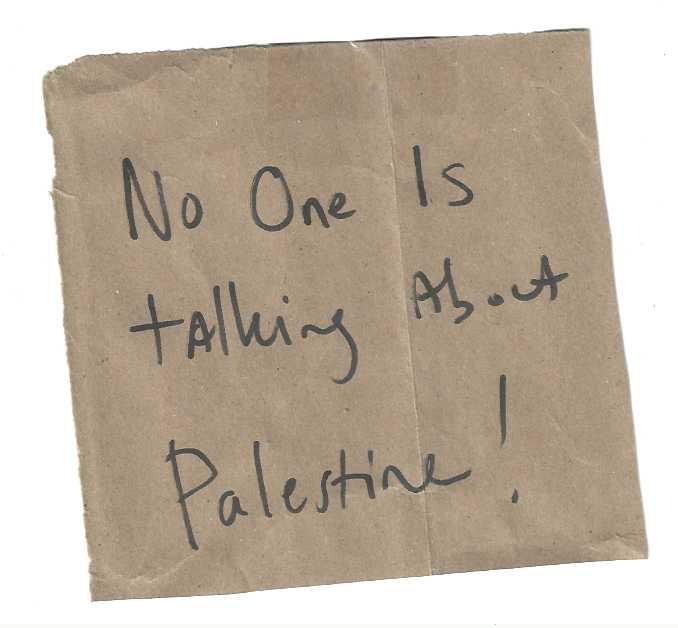

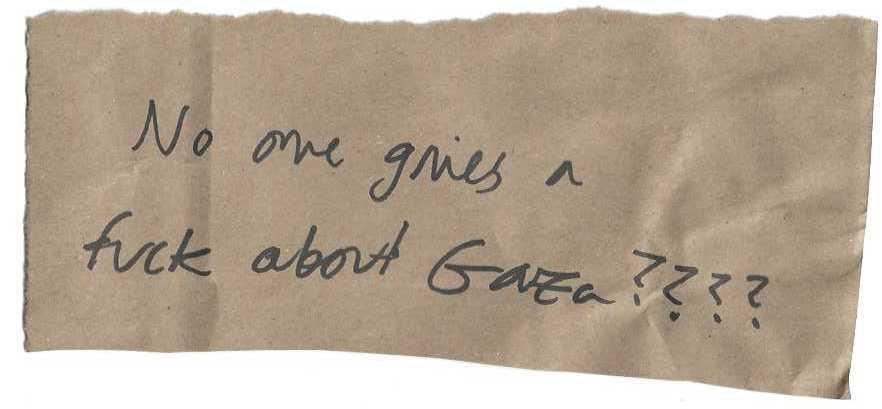

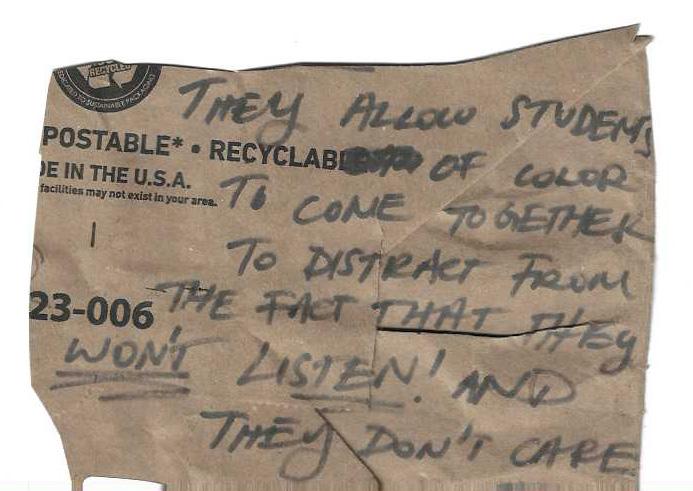

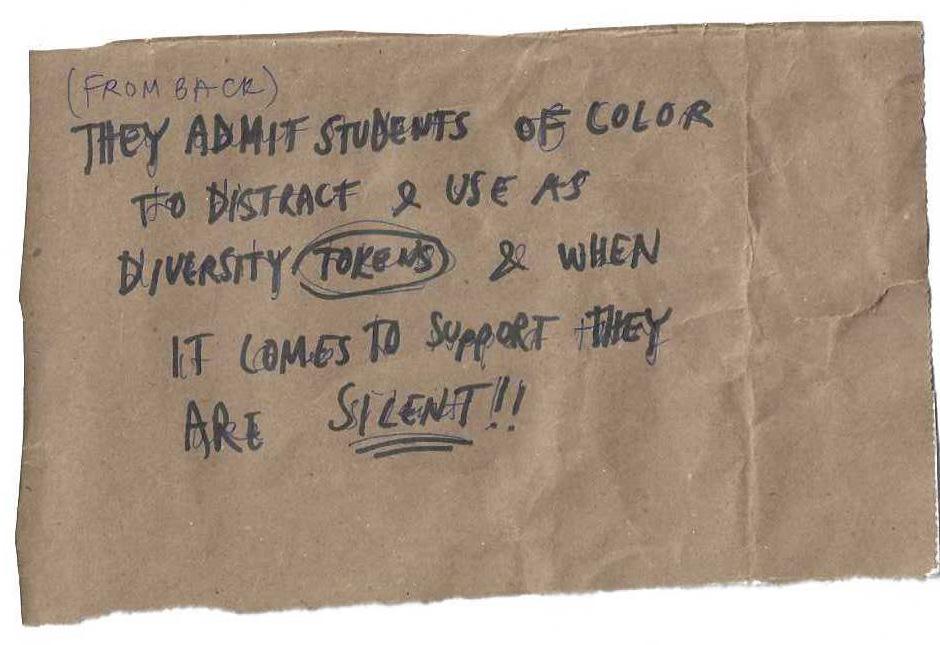

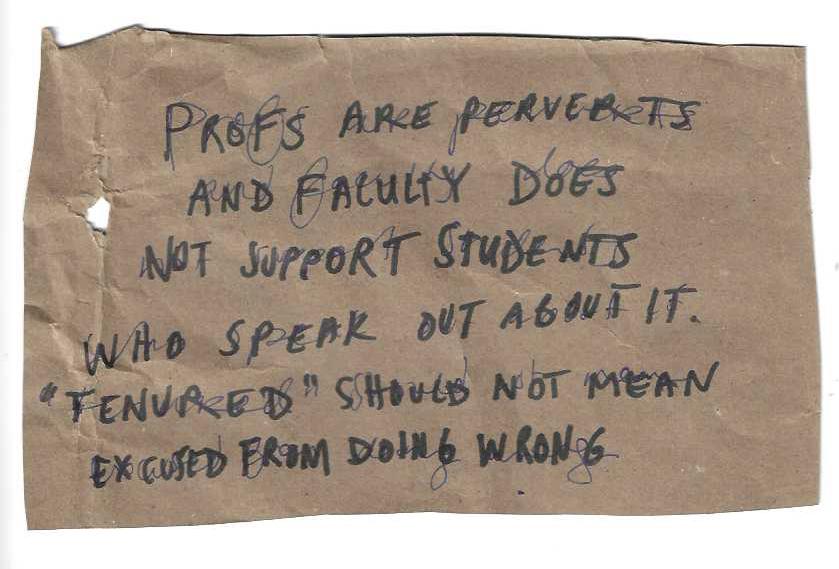

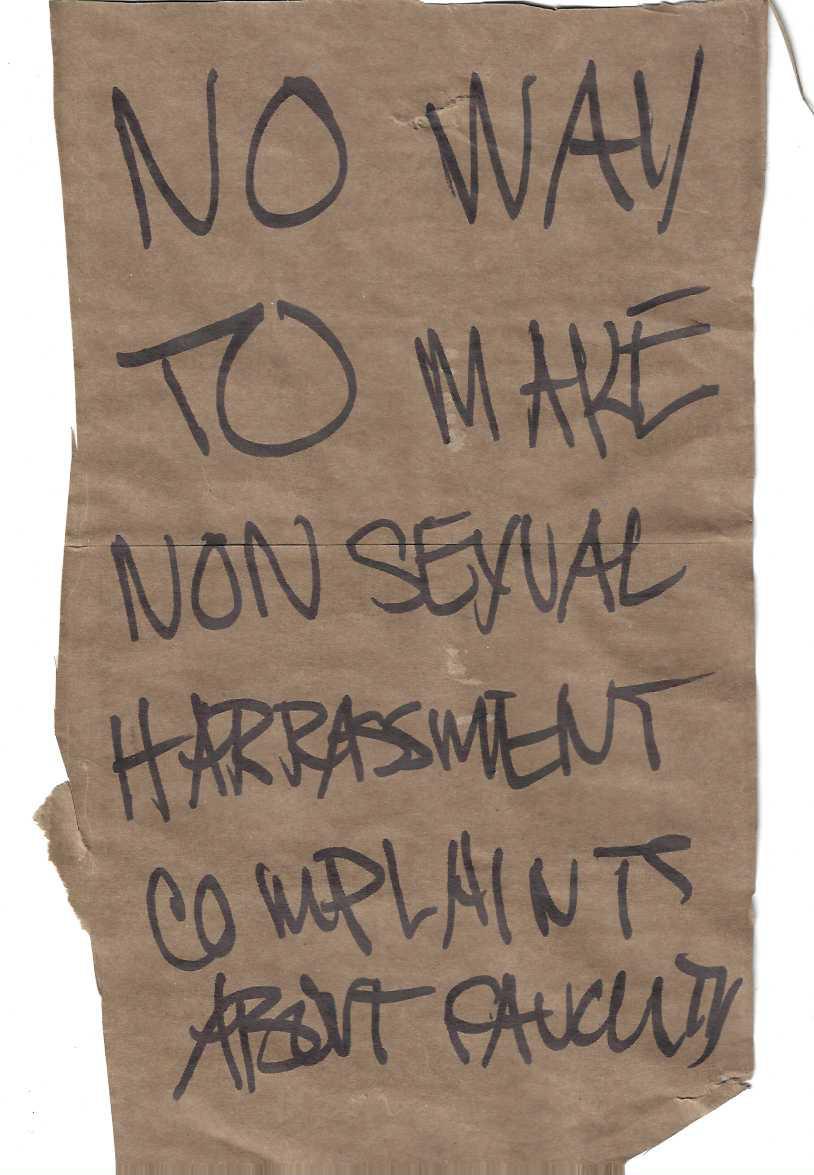

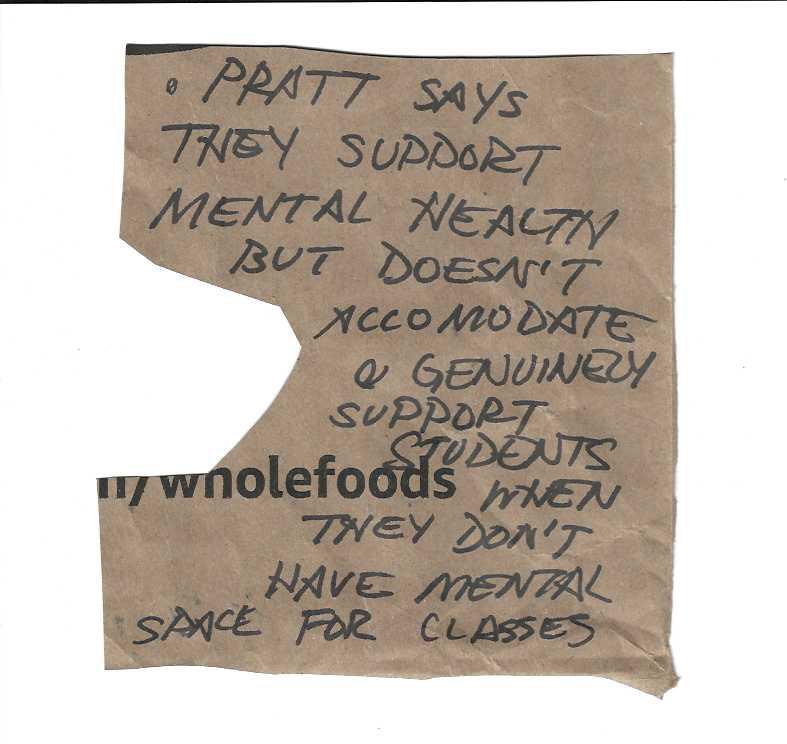

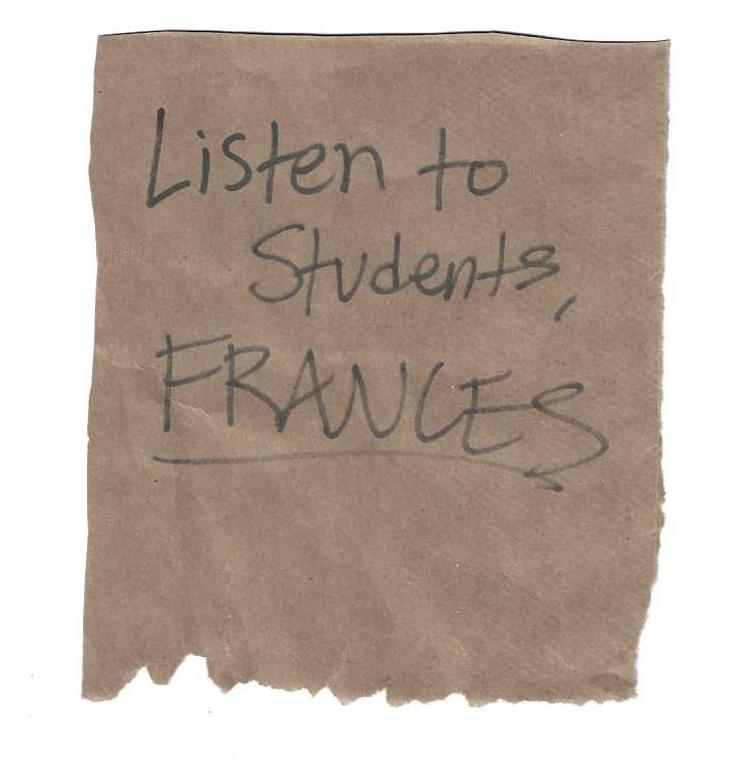

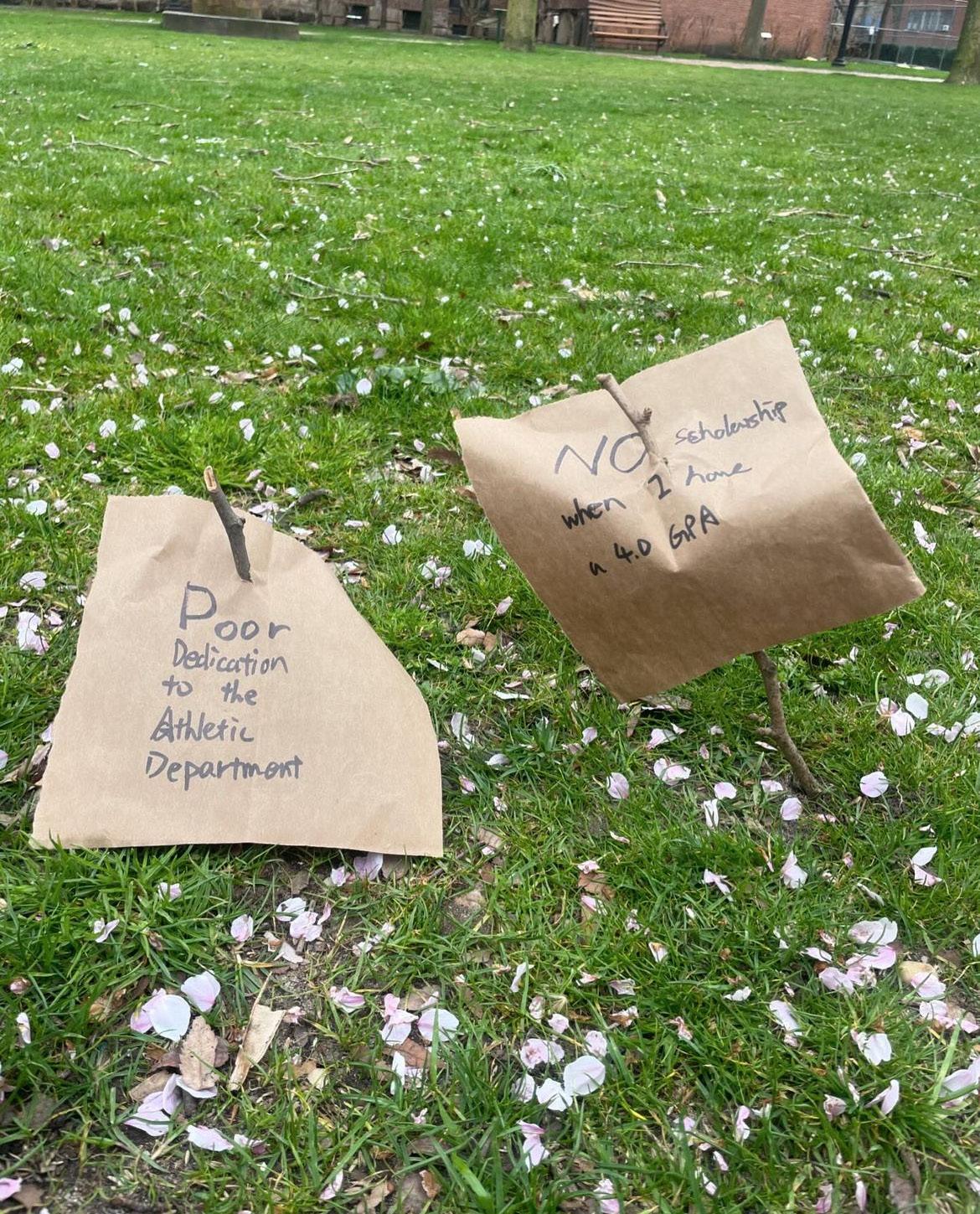

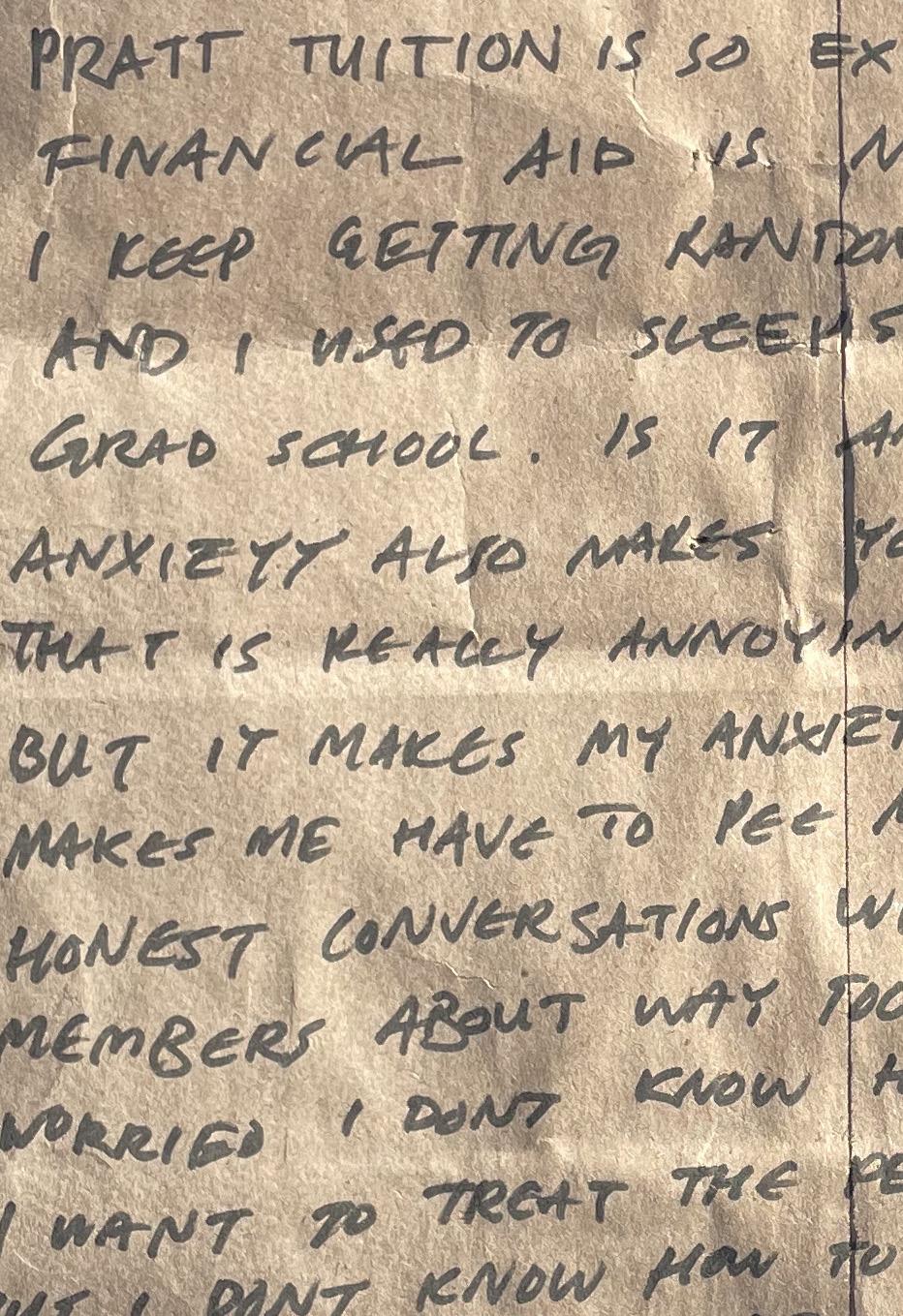

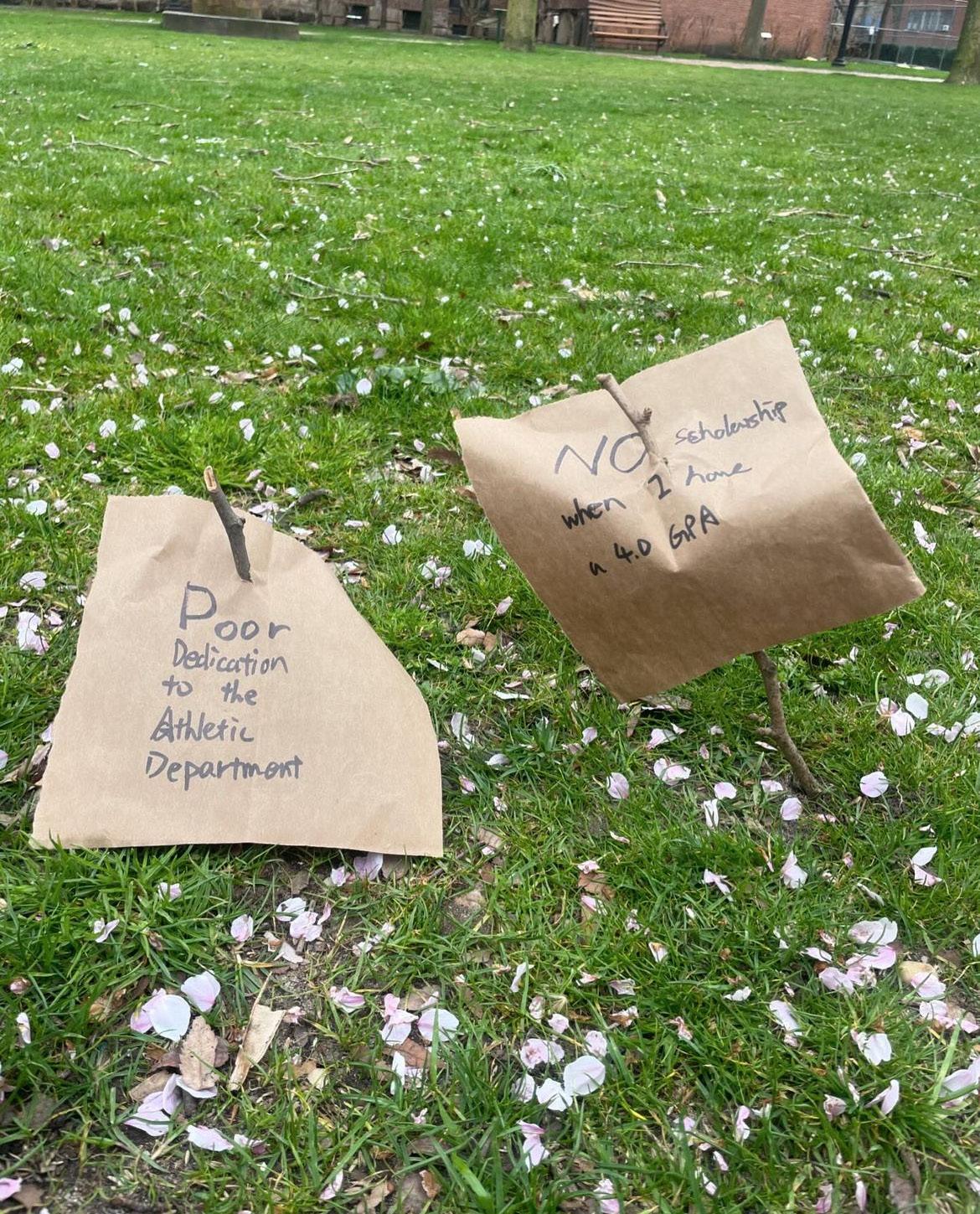

Suzanne: I think the first thing I experienced would be how people almost seemed excited to be talking about their grievances or things that they weren’t happy about. I felt like it was cathartic for them. I had conversations with people where they looked me in the eye and told me these things, but then I think it felt different for them to write it down on a piece of paper, and see it be placed the ground looking like a flower or hanging on the cannon. There was just something experiential for people. And I felt something too, in listening to them. So that was interesting for me.

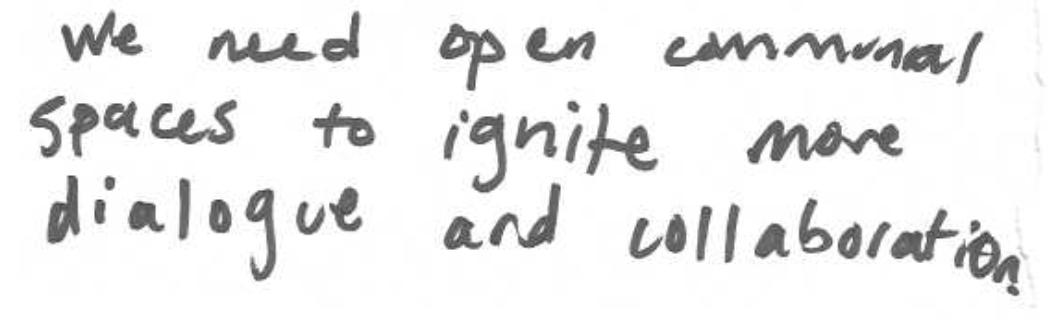

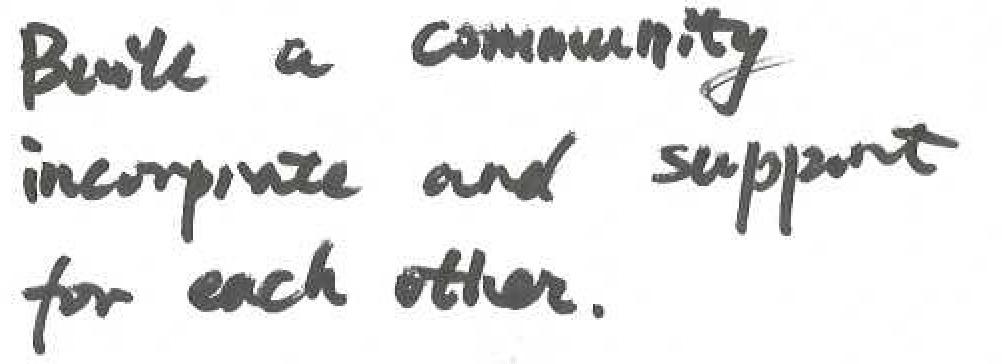

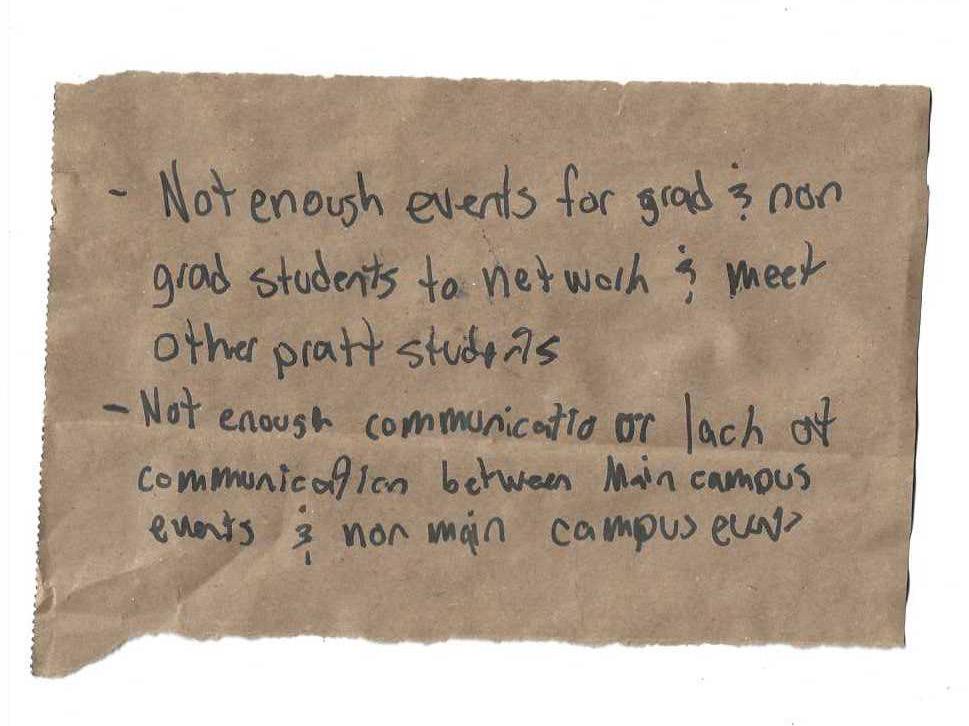

Aliza: But like, I do wonder if there’s a way that those moments filled some kind of lack in community space that we have right now as a school. I see events constantly, sent to me in email like, Oh, we’re gonna have this thing – we’re gonna, you know, talk about mental health or drug use, but, it’s not becoming the space that maybe the school wants it to be. It’s not a place where people feel like they can constructively vent about these things.

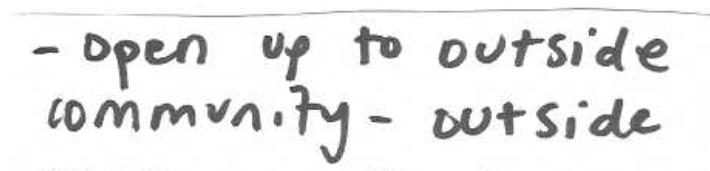

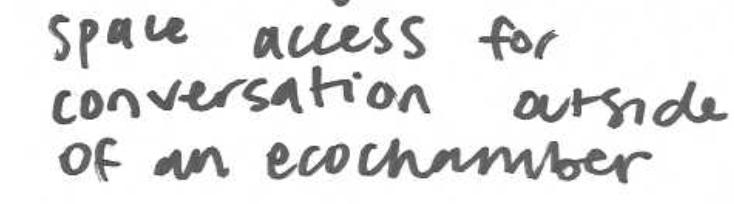

So, I wonder what possibilities there are to make something that lasts and how we can create a space for people to communicate with each other about what they feel is lacking, outside of their specific friend group or something like that. And are people interested in a campus-wide dialogue? Do we have a student body government?

Aliza: I wonder, do we feel like there’s a desire for [community dialogue] at Pratt? Do we feel like there’s a way to do that? Corey, do you have anything from your personal experience that relates?

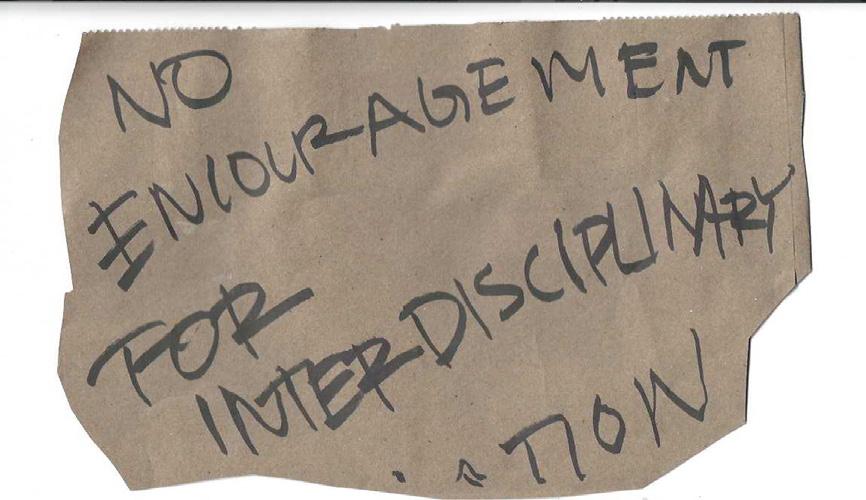

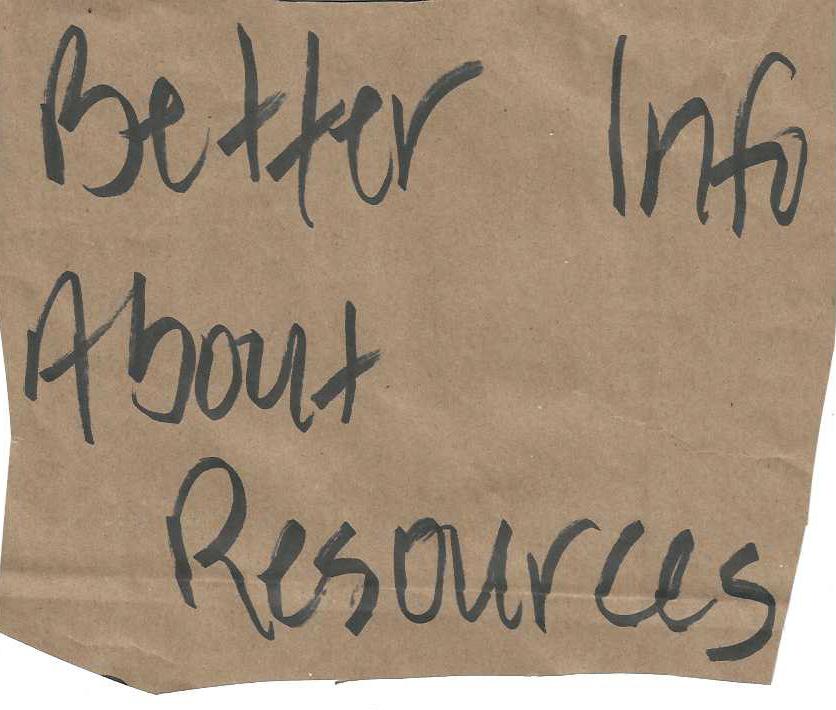

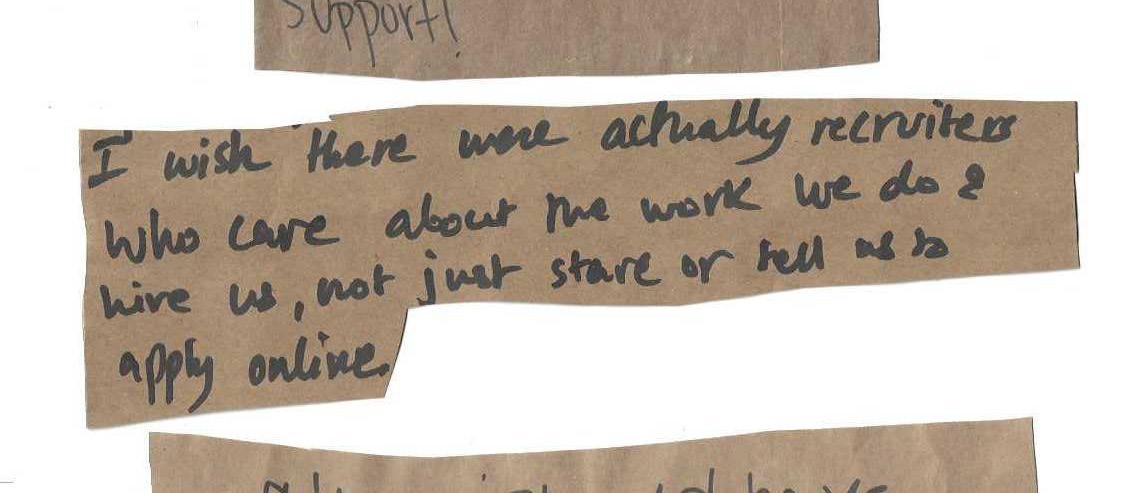

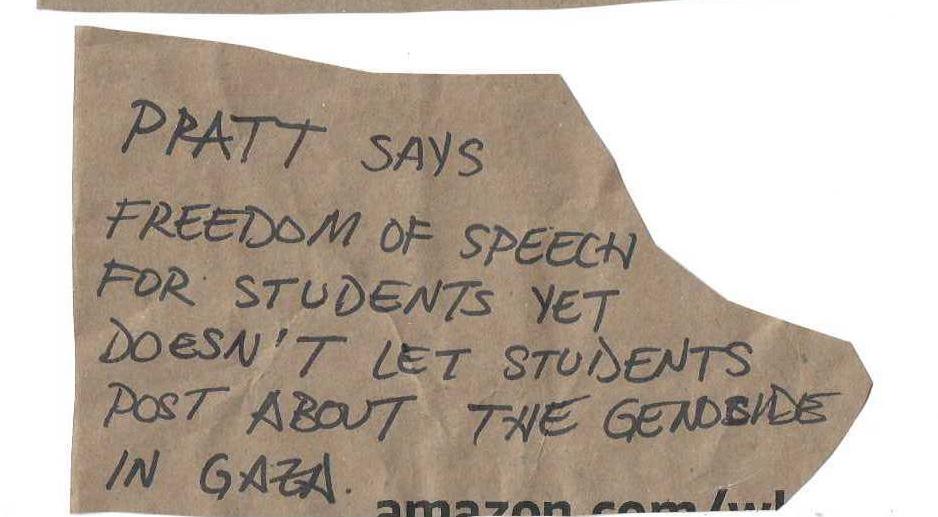

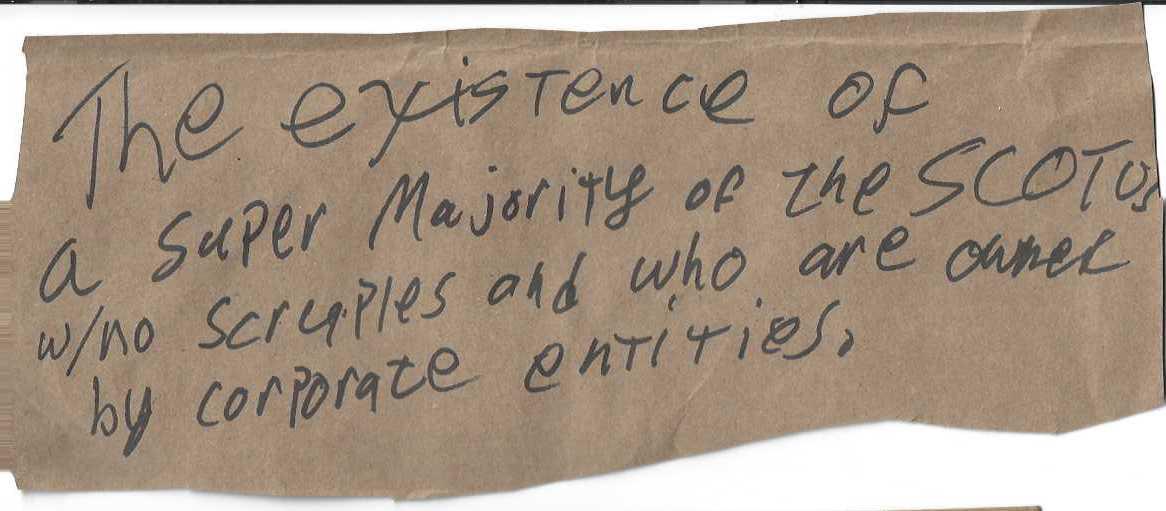

Corey: Yes. And I also feel like there are multiple things that are affecting the current experience. The students are communicating their own opinions or differences. COVID had a huge impact on that. You guys were speaking about it earlier, Pratt has a pattern that everyone has seen, when you have an issue they don’t have a direct answer, instead they send out an announcement to vaguely address that problem. You don’t get a definite answer for a lot of things. I think my classmates are very vocal, but I also think a lot of them saw that pattern. It’s exhausting.

I remember I joined them during the protests, in front of the library, and it was great - I think everything definitely went well. They got their point across for sure... The disheartening part was witnessing [the Pratt administration] ignore such powerful energy outside. Pratt provides the space to communicate issues, but they don’t give you the resources to solve them. I think personally, I’ve always wondered, why Pratt doesn’t give us an explanation as to why they can’t.

Aliza: Oh, that’s great.

Corey: Yeah, the undergrads are vocal, they have things they want to say. I think it’s just fatigue. Yeah. You know, like, who’s listening? And is it gonna make a difference?

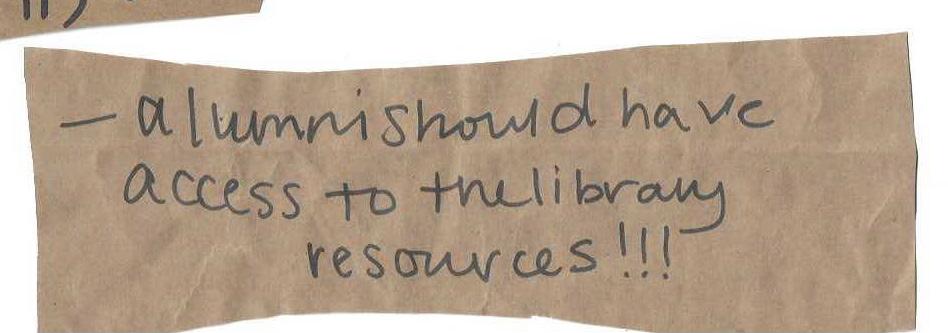

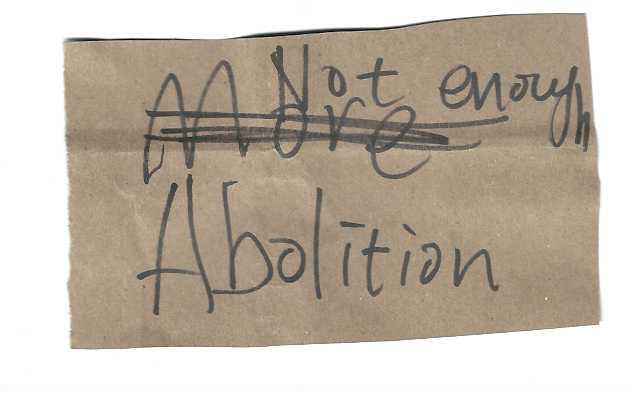

Suzanne: I hate to say it, but it’s kind of like what we’re doing with this project. That’s something I was going to say as well, I felt frustration with this process, because we are hearing all of these things that people are upset about, and we’re wondering what we can do about it. And I went and talked to somebody who’s the head of the Student Union to see if we could leave the grievance sign and the collection box there permanently. And he said no, that he didn’t feel like he was the right person to collect that information. He felt it would be better coming from the student government, fellow students asking for suggestions in a more positive way. He gave me an email from the student government, and I emailed them but I haven’t heard from them.

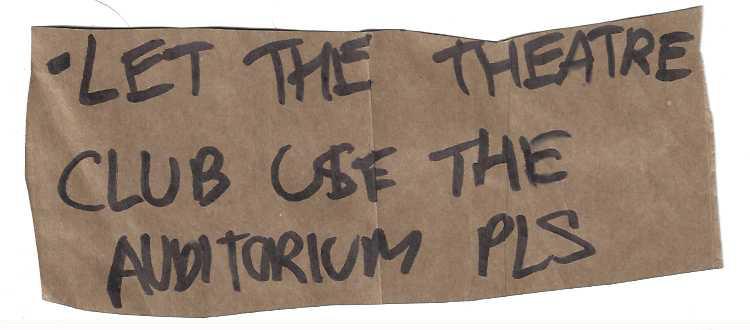

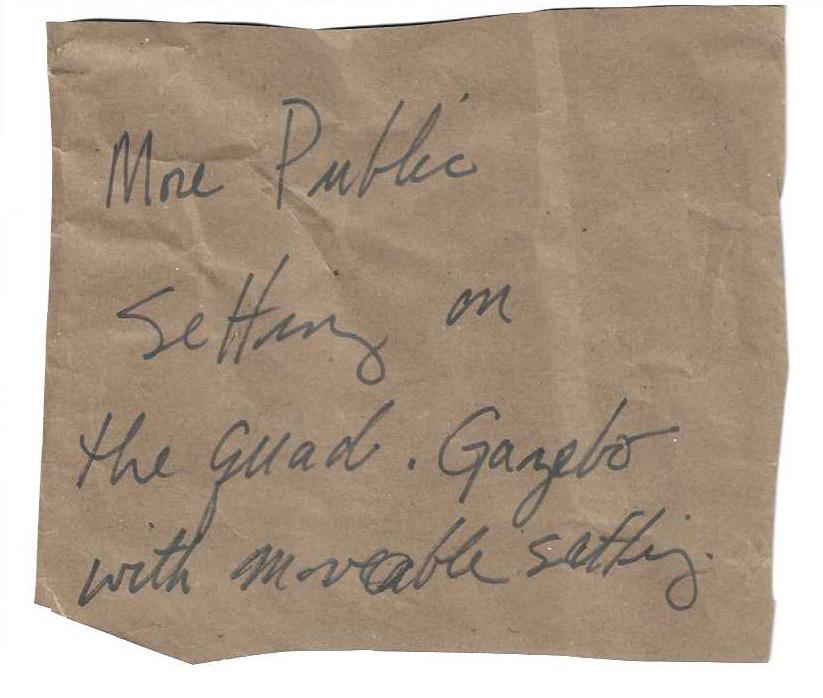

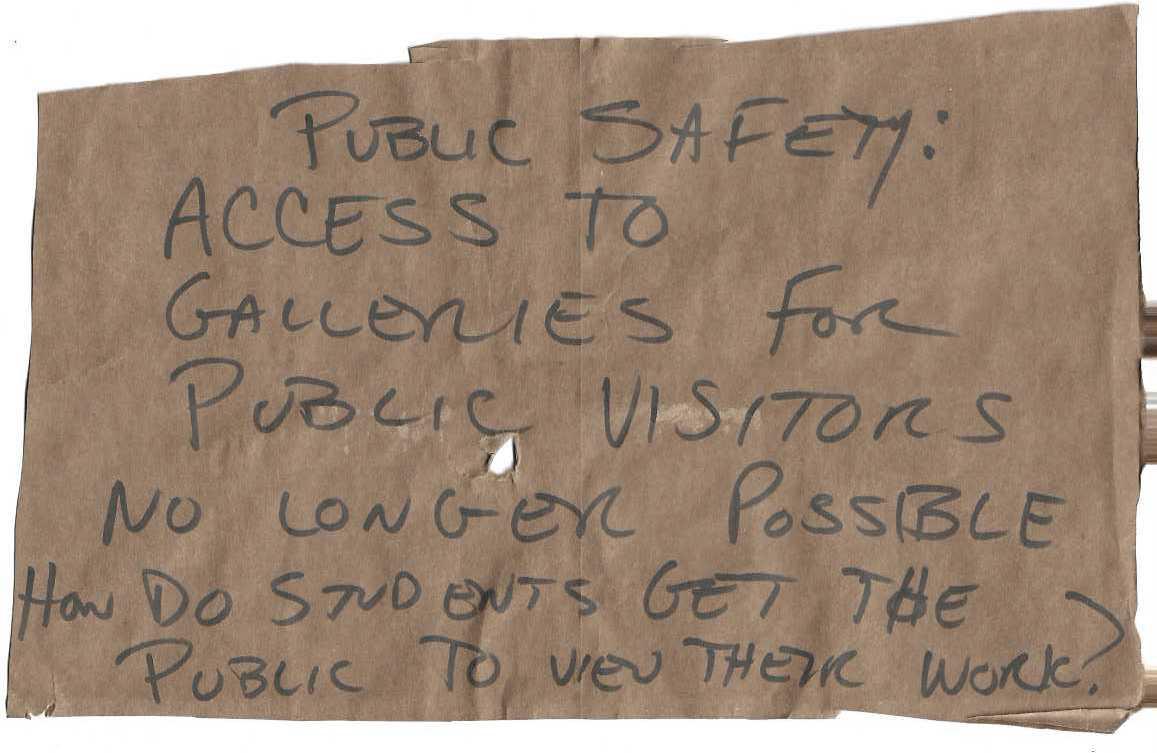

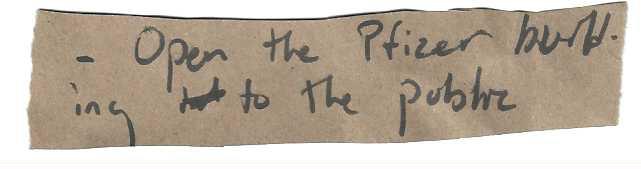

Aliza: It would be nice to have a permanent public forum, because something that I remember about my undergraduate campus was kind of nice was that there were a lot of public bulletin boards around campus where people could just post things, there weren’t that rules about what you could post, people would just stick up stuff.

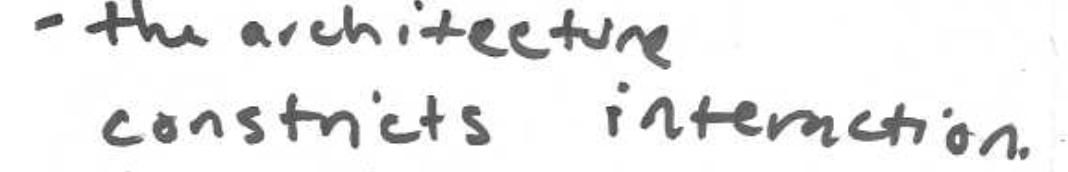

It was a really good way for people to have their voice. But I feel like a lot of the bulletin spaces we have are indoors and are very easy to walk by. You have to get permission for what you post. And there’s kind of an economy of space going on. It’s all very official, like having some kind of public forum for people to organize meetings or voice their thoughts could be great. Not that it wouldn’t be subject to any kind of, you know, regulation or something like that. But I wonder why we don’t have any kind of outdoor public space for students to interact with?

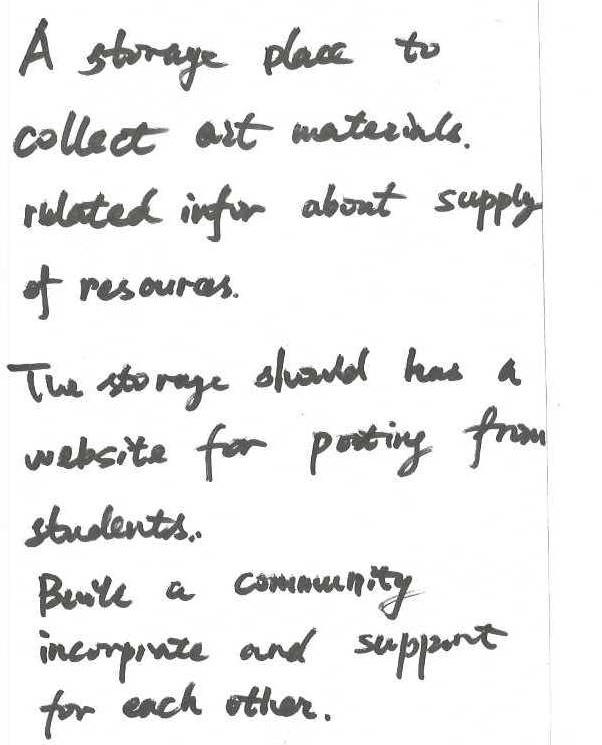

Mary: It’s a good question. I think we’re asking more questions at this point. And we don’t know how the booklet is going to be read, or what could happen from it. The more people who have it, I think the more potential there is for something to happen from it, There should be a space that is dedicated for people to leave information because the events that Pratt Institute plans don’t always have the same effect, maybe because they’re top-down. And we need a space that’s not [topdown].

We have a student union, but it’s indoors and people have to make time to go there. Maybe we could say that one of our takeaways is that there should be a community space that is more accessible.

Aliza: I wonder how much of it is an East Coast phenomenon where we prioritize indoor spaces so much because of the weather, but, I don’t know, there’s such an inside/outside vibe to this campus, especially with the fact that it’s gated. Like, that’s very non-permeable.

Corey: We are directly exposing the holes in the structure at Pratt. So I do think we’re helping in that aspect Even if we don’t blatantly say ‘Pratt needs to do this!’

Aliza: Well, we might as well because, I think our administration, even if it’s just performative, they try to react. And, if you push on something enough, I think that they would at least make a show of trying to address it. It could lead to some changes.

Mary: Yeah. It would be so easy to have that cannon space have covered bulletin boards that folks could use to post.

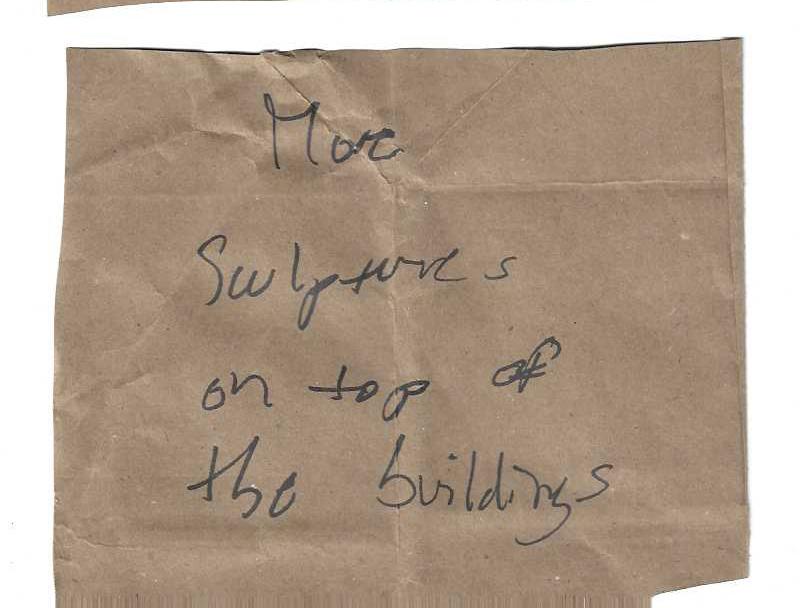

Suzanne: It would feel more like an art school.

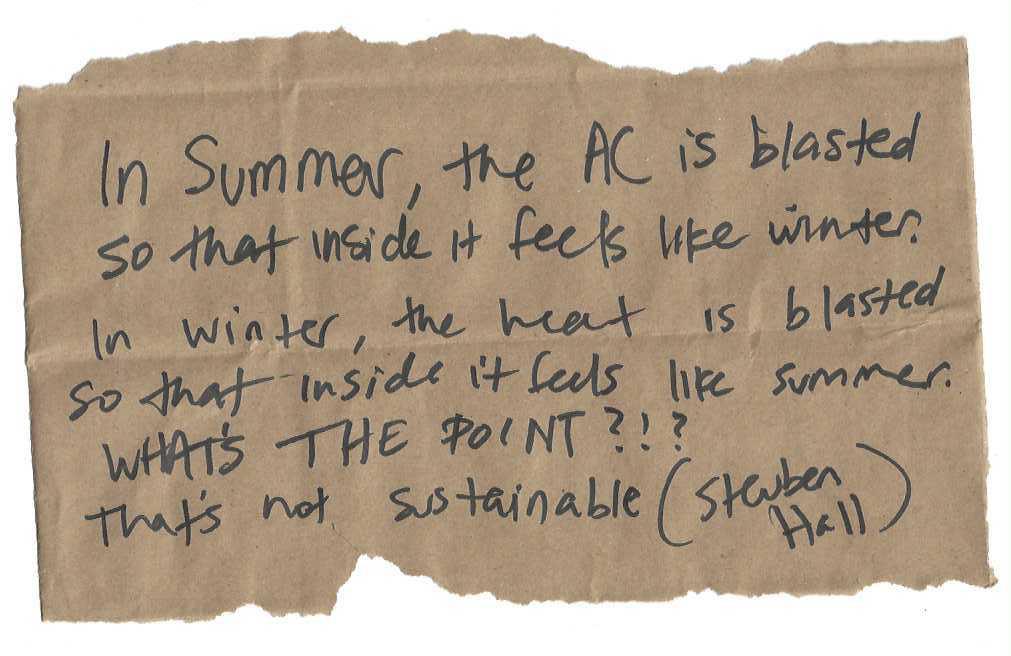

Isabelle: I feel like there’s so much here like, between the gates, like you mentioned the stamps on the posters. It feels so controlling, it feels so constrained. And it feels so un-art school-like.

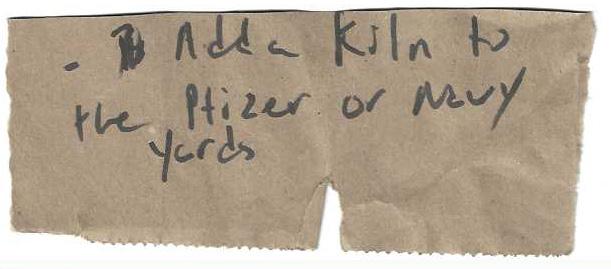

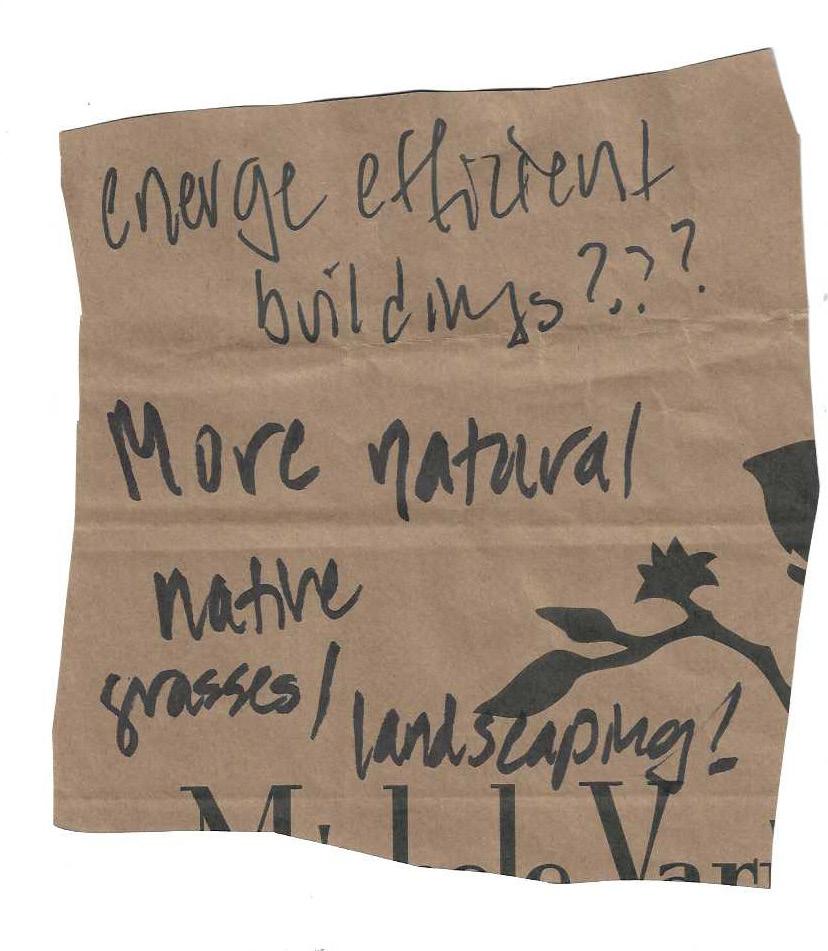

Corey: I just think we need more art, more sculptures and things around the school way, it’d be a lot more... I don’t know, lively for an art school.

Amanda: It’s sinking in the more I hear that Pratt does have this very specific aesthetic that it’s going for with the way that its campus looks. It is probably close to what it looked like when it was built, you know? It’s very manicured. I wonder who was like, ‘this is how it needs to be forever.’ The aesthetic is visible in the lawn, and the grass and things. And I also think those aesthetics must be reflecting something.

Isabelle: Yeah, I think it’s interesting. I know there were conversations pre-COVID about getting rid of the gates. I think it’s also interesting, like the context of being part of ‘urban renewal’ and those kinds of things... gentrified neighborhood and what that means, and how does that conversation happen within the context of security?

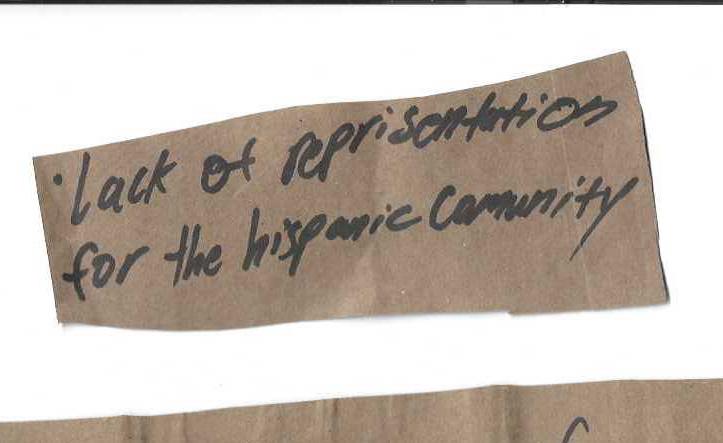

Aliza: I think that’s one of the reflections and questions that I have. Because being a university student, how much of an obligation do you have to be comfortable navigating the neighborhood that you’re [in] and where does that conversation even start. Because then you get this, this antagonistic relationship towards the community that you’re embedded in. It’s this even stronger internal-external dichotomy of okay, we’re within the campus grounds. And outside of it, like it’s unsafe, or it’s unpredictable, or whatever.

But I mean, a lot of different campuses have this problem– like, the students don’t feel safe walking by this or that or that park, maybe people are getting robbed frequently, like back where I went to undergrad that’s a recurring issue. And it’s like, is this a problem that the university needs to address?

You have this university with all these resources that students feel comfortable attending, and then the town around it is getting more and more unsafe, and what does that mean? And my question is yeah, as a student, you shouldn’t have to be unsafe to go to school, but also as people who also live in this neighborhood, how much of a right to be insulated from the town we live in do we really have? How much can a school try to protect its students before it becomes a bigger issue than the university?

And I don’t know, I’m not really making any kind of statement. I just wonder what kind of a relationship we want to have. Or, how do we even start to think about responsibility in these cases. here do we want to place it, and what the implications of that are.

You know, should you not go to school somewhere if you’re not comfortable with the neighborhood? Is it an issue of personal responsibility? Or is it an issue of like, the school isn’t doing enough? Does a school, as a local institution, have a responsibility to do more for the neighborhood? You know, or is it purely a local community problem? I don’t know.

Isabelle: It makes me think, too about the resources that are given to students to make them feel safe. For instance, Higgins Hall is outside of campus, and there are all of their late-night classes all the time. We will have professors asking us like, ‘Oh, do you feel safe going home at like, 11 PM?’ I think it’s also a major thing for international students. Someone in my cohort, who is from Pakistan and wears a hijab, no one ever was like, ‘Do you feel safe getting home?’ Thinking of that speaks to the broader lack of support for students.

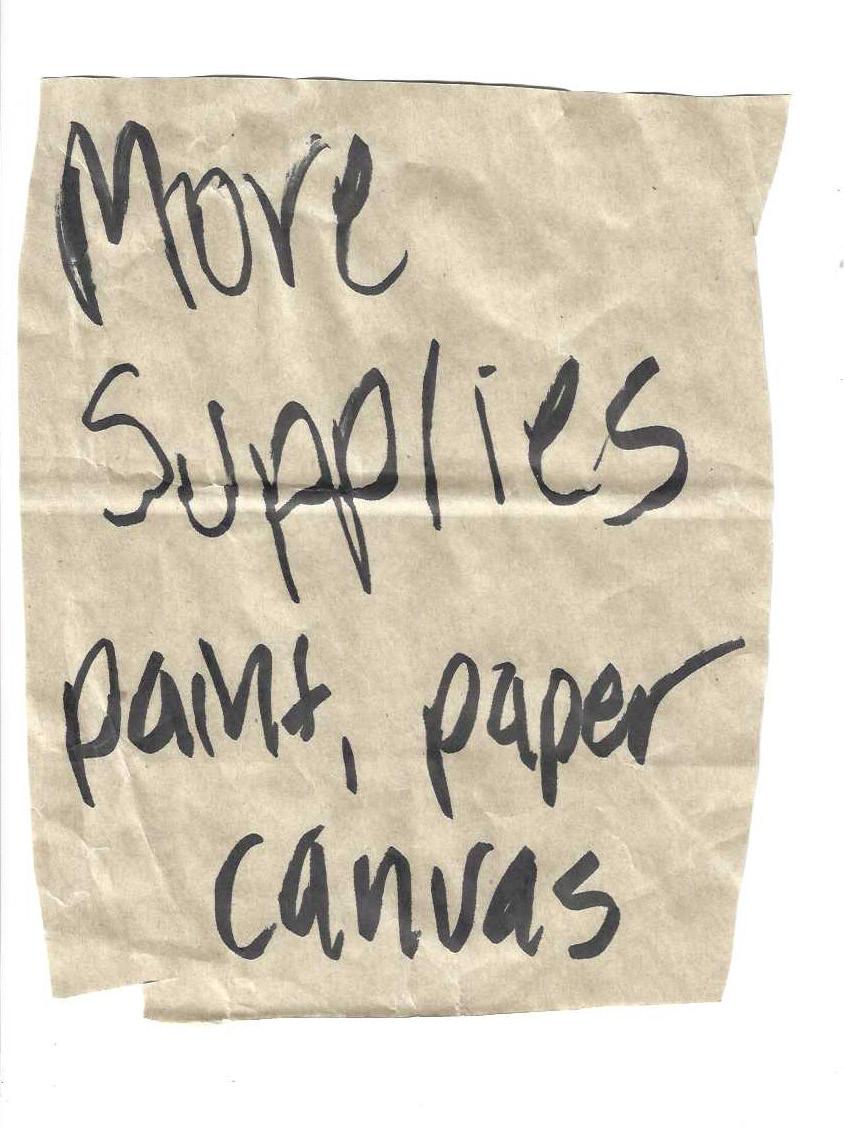

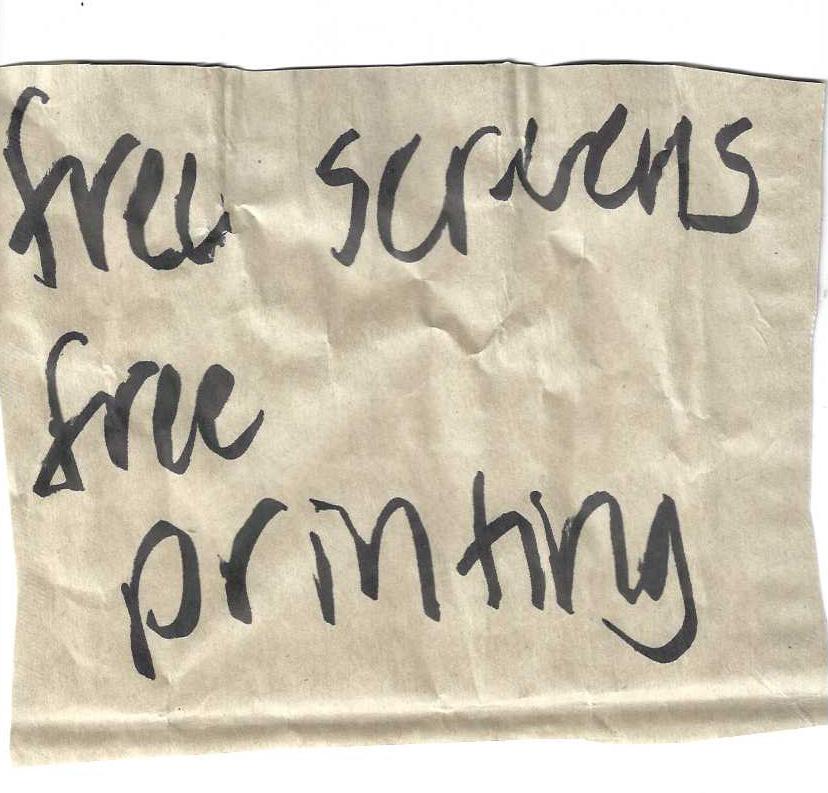

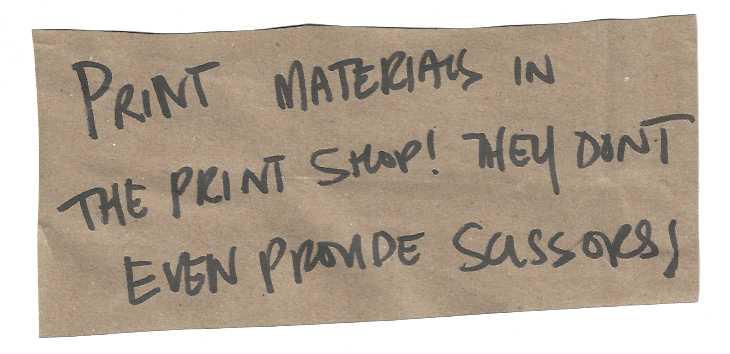

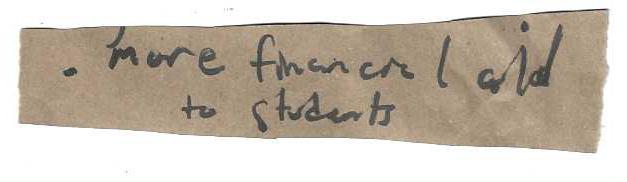

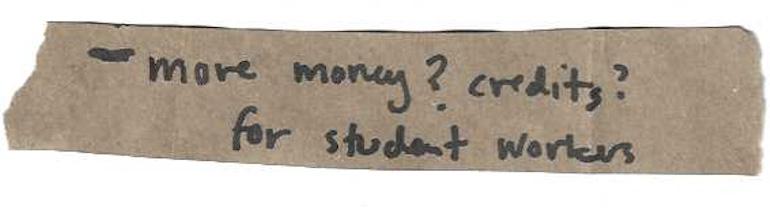

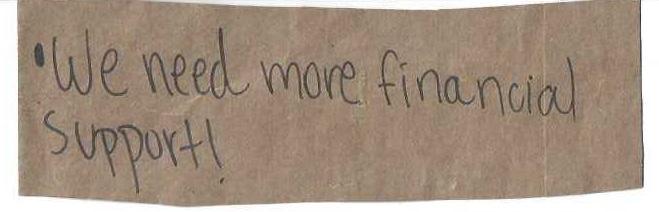

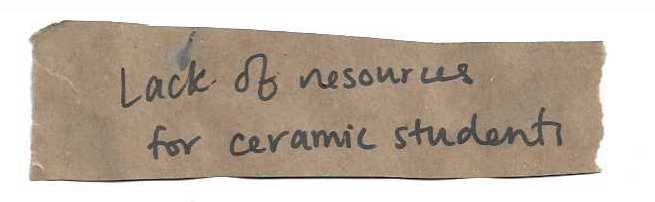

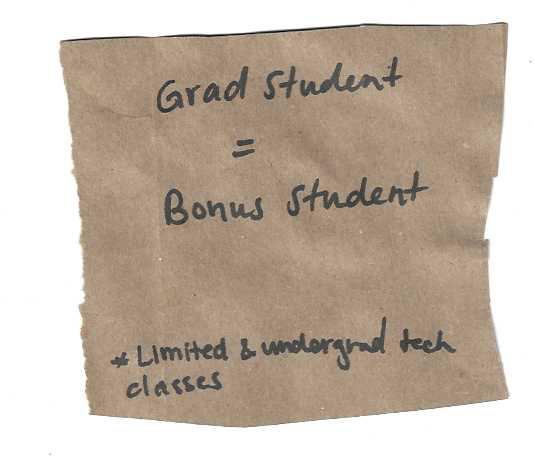

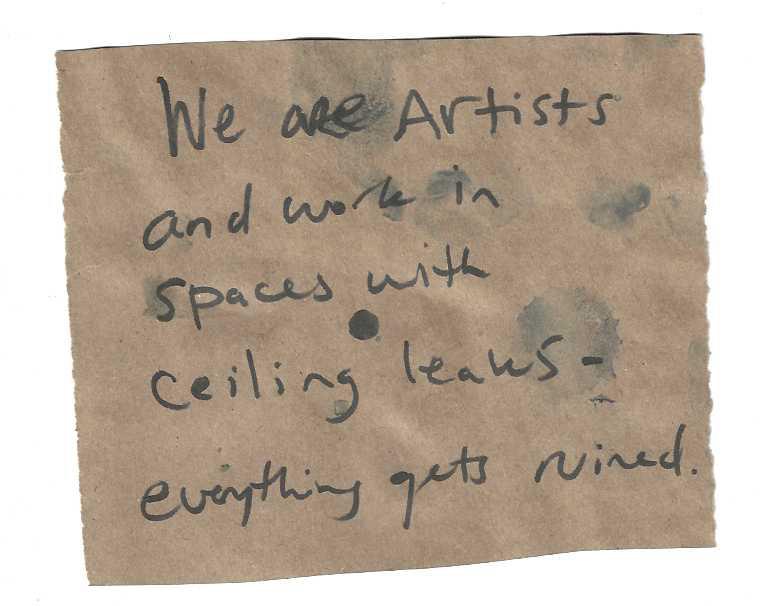

Amanda: Access to budgets is interesting... a lot of grievances were about that.

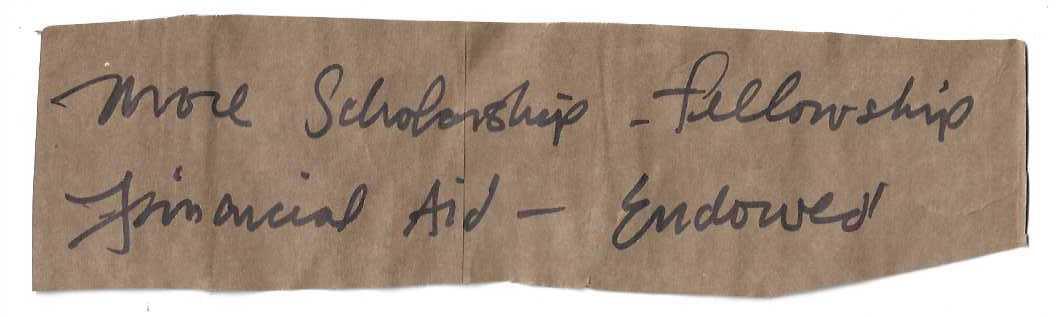

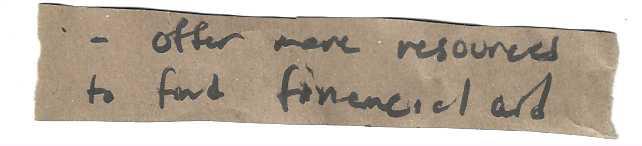

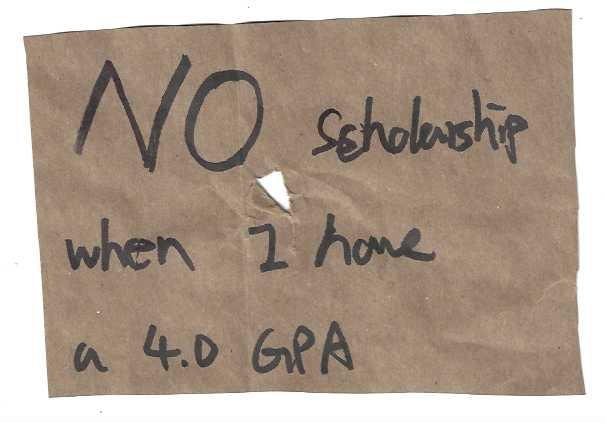

Aliza: I also want to know as a school that only offers up to 50% scholarships, like, where’s that money going? So that’s why I’m so fascinated by hearing them.

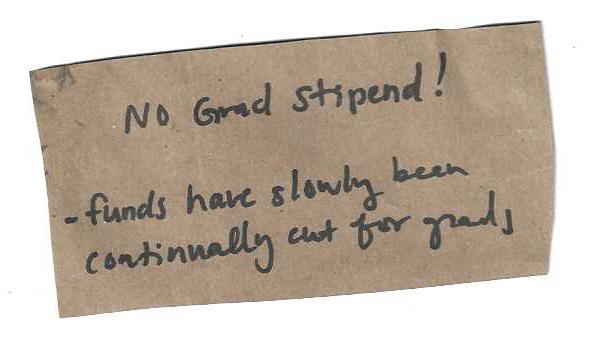

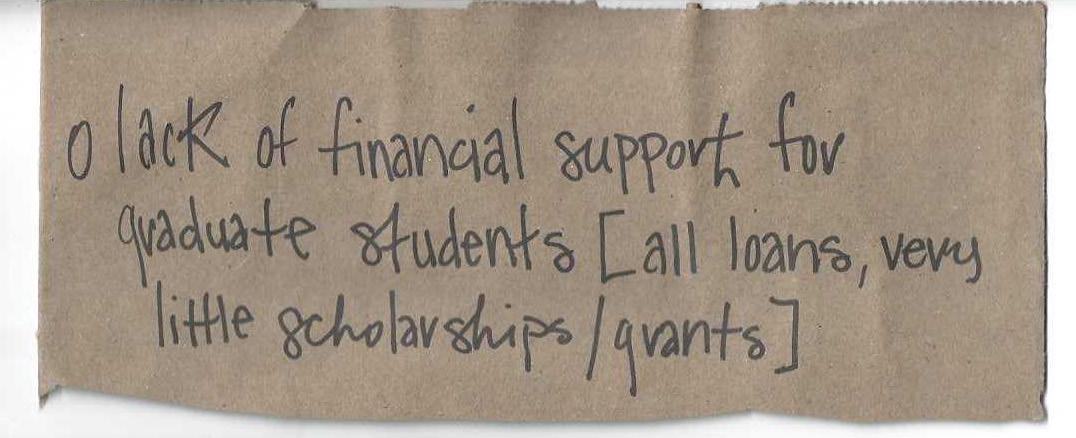

Aliza: I mean, I still have the same question, What is our budget like that we can’t even offer like, a full scholarship? We can’t even offer like, a 75% scholarship to anyone. That’s crazy. I don’t think we even have need-based scholarships. We just have loans. I think that through FAFSA, the government offers financial aid, but I mean, that’s the government though. But that’s only loans and merit scholarships. And, that is, that’s a discount on the tuition, right? It’s not surely a scholarship, you get up to 50% off your tuition. But they don’t do any higher than that. Which is kind of crazy.

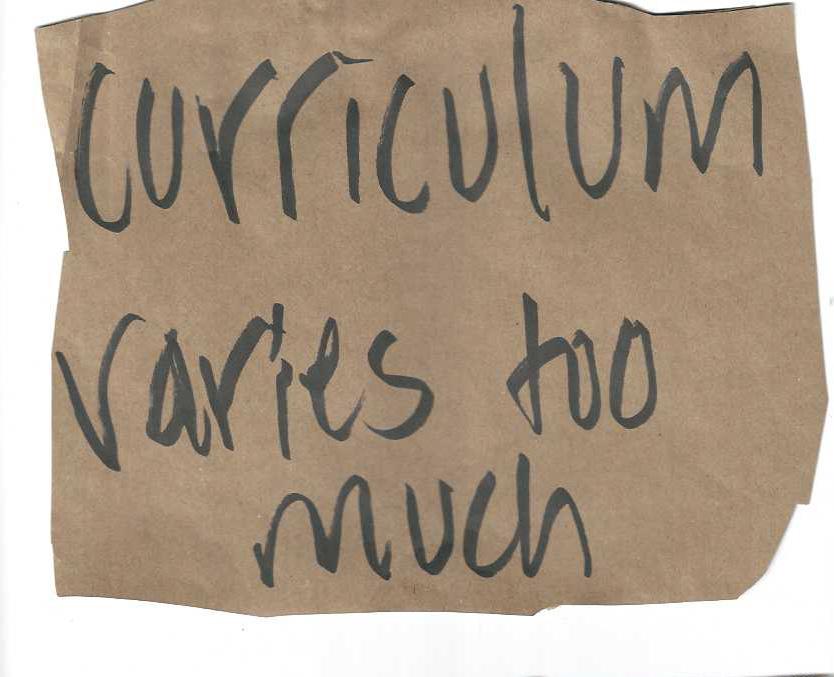

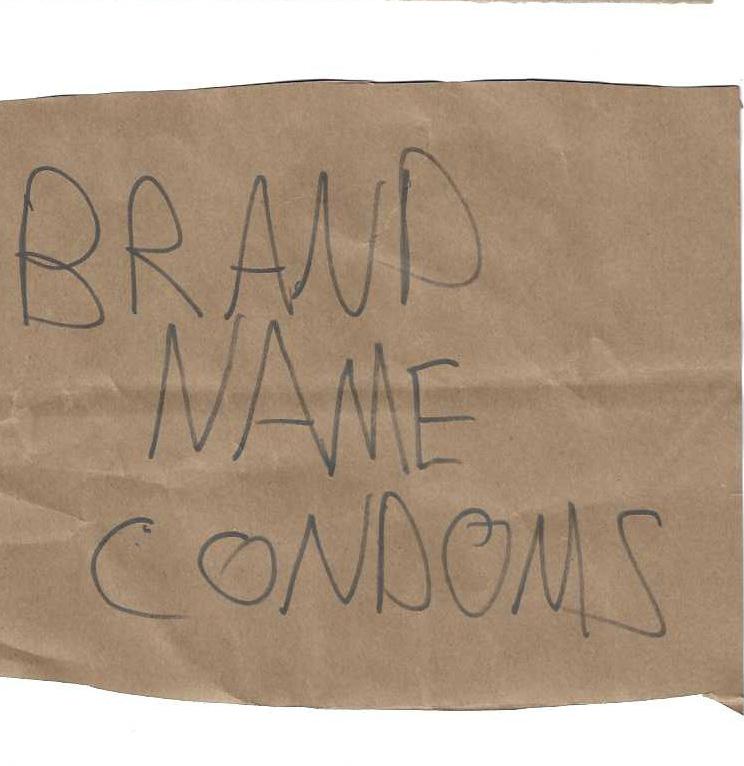

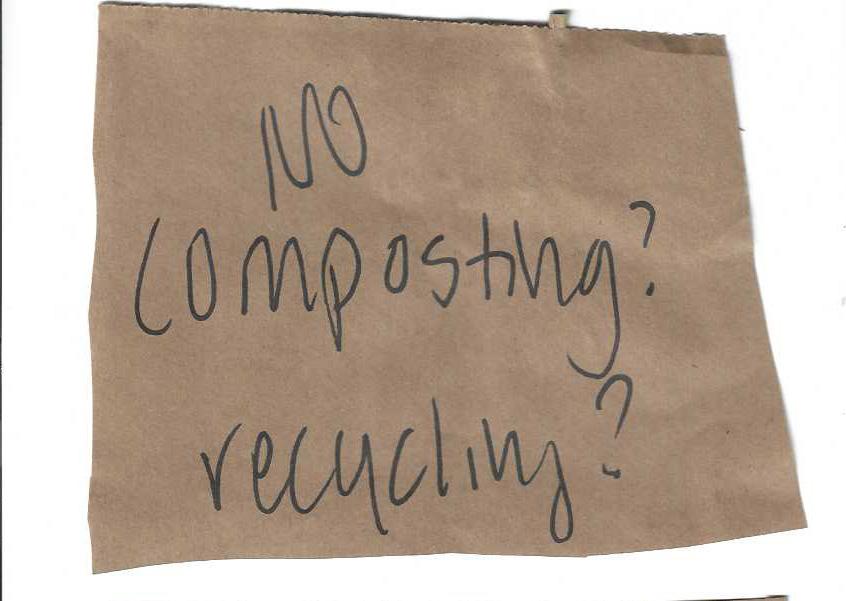

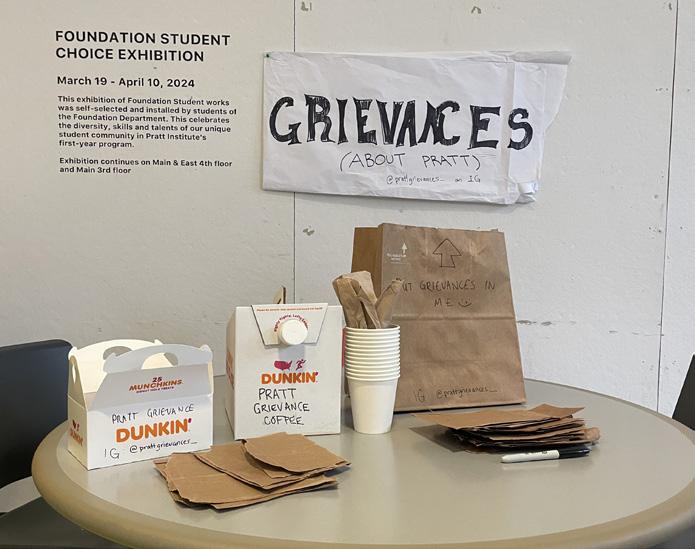

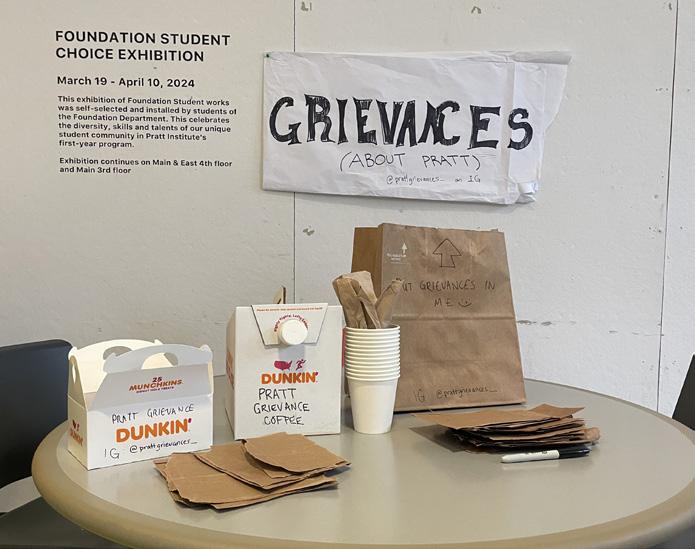

The purpose of the Grievances project was to provide a channel for the Pratt community to express their aspirations and frustrations, and relay their own personal experiences of Pratt Institute. This zine is not intended to make an argument about the objectivity of complaints, rather to acknowledge the importance of the subjective experiences of our community members. For the purposes of helping readers understand the context in which these complaints were made, we have compiled some information about Pratt Institute below.

Financial Information

The average yearly tuition for undergraduate students at Pratt Institute is $57,659, with estimated total cost of attendance between $80,993 and $88,688 depending on the student’s housing (on-campus, commuter, off-campus). For graduate students, cost of attendance varies by credit, and depending on how many units a student is enrolled in, as well as housing status, the total cost of attendance can range from $39,402 to $91,322 annually.

Pratt Institute is located in the Clinton Hill neighborhood, between Bed-Stuy and Fort Greene in Brooklyn. In August 2015, Clinton Hill’s median rent was $2,741, according to StreetEasy. The current average rental, as of April 2024, is $3,675 according to RentHop. Less than a decade has seen an average increase of over 30% for residents.

According to cost of living estimates provided by Pratt Institute for its students, the school estimates a $31,126 combined cost for food and housing over the course of an academic year. The $31,126 broken down over the 10-month standard school year would leave approximately $3,112.6 per month for combined food and housing for one student.

Student scholarships at Pratt Institute are merit-based, with the maximum amount of available scholarships covering approximately 50% of tuition. Need-based aid is available to Undergraduate students in the form of “gifts” added to financial aid packages. The primary source of financial aid for both Undergraduate and Graduate students is federal loans, which may or may not accrue interest during student enrollment (depending on the type of loan). Internally, Pratt Institute does not offer any full scholarships based in merit or financial need.

As of 2020, Pratt Institute has a total endowment of $224.5 million. All of this information is available on Pratt Institute’s website, pratt.edu

Pratt Institute was founded in 1887 by Charles Pratt, with deep ties to the historical development and character of the neighborhood. Pratt was originally a more generalized school, including classes in engineering and liberal arts. Enrollment grew rapidly, and the institution became profoundly influential; Pratt Institute served as a model for the modern Carnegie Mellon University, and the former Heffley Department of Commerce, which grew out of Pratt’s Commerce Department, eventually evolved into the Brooklyn Law School.

Charles Pratt was American industrialist, successful businessman, and oil tycoon. The wealth which Pratt built from his industrial enterprises eventually shaped the character of the Clinton Hill neighborhood. His decision to build a mansions for himself and his sons on Clinton Avenue led to a major rebuilding of the street. This trend of redevelopment attracted wealthy new residents who demolished existing suburban housing to build new mansions; In the final decades of the nineteenth century and first decades of the twentieth century so many grand mansions were erected that Clinton Avenue became known as the “Gold Coast.”

This trend set development in Clinton Hill on a different path from the surrounding neighborhoods of Park Slope, Cobble Hill, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Crown Heights, which developed from farmland to stable middle-class residential sections over an approximately 30-year period.

Prior to the 1950s, Pratt Institute existed as separate buildings on public streets. Under his urban renewal plan in New York City, Robert Moses cleared structures and housing located between Pratt’s buildings, closed multiple streets to automobile traffic, and enclosed the main campus to create the space we know today.

Sources

New York Landmarks Preservation Commission, “Clinton Hill Historic District.” City of New York, 1981, https://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/2017.pdf

Cobb, Geoff. “Oil, Philanthropy, the Astral and Art: The Mixed Local Legacy of Charles Pratt.” Greenpointers, 14 Feb. 2018, greenpointers.com/2018/02/16/oil-philanthropy-astral-art-mixed-local-legacy-charles-pratt/

Boston Evening Transcript, Thursday, January 16, 1902

Spellen, Suzanne. “Walkabout: Stenography and the Law in Brooklyn.” Brownstoner, 2 Sept. 2010, https://www.brownstoner.com/brooklyn-life/walkabout-steno/

Powell, Michael. “A Tale of Two Cities.” The New York Times, 6 May 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/06/nyregion/thecity/06hist.html

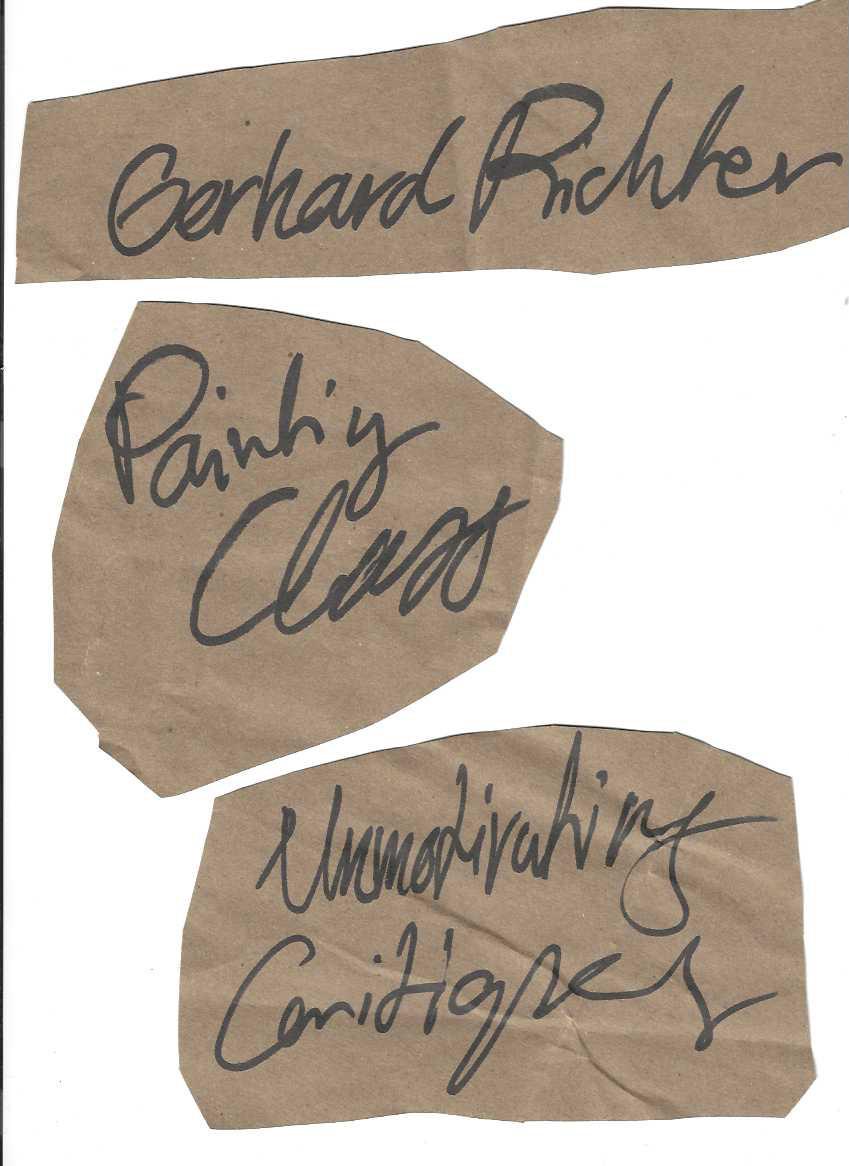

Designed, written, and edited by Emelia Gertner, Aliza Katzman, Amanda Baker, Corey Lovett, Isabella Saunooke, Suzanne Watters and our Professor Mary Mattingly as a Directed Research project for the Spring 2024 semester at Pratt Institute.

Printed in an edition of 200

This zine was only possible with the participation and feeling of all the students, faculty, and staff at Pratt Institute who generously contributed their grievances to our project.

We hope that by gathering and sharing these grievances, we can shed light on the conversations happening in our community and make room for more open and transparent dialogue.

For those who want to continue sharing grievances, we have a more dynamic project online at our instagram @prattgrievances_

Number /200