Editors

EDITORIAL BOARD L

STELLA RANELLETTI EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

WALLIE BUTLER EXECUTIVE PRINT EDITOR

ANAYA LAMY EXECUTIVE DIGITAL EDITOR

MIA MICKELSEN EXECUTIVE FINANCE MANAGER

EMESE BRACAMONTES VARGA WRITING EDITOR

LIV BOURGAULT DESIGN EDITOR

JOEY BEZNER ILLUSTRATION EDITOR

ISABELLA THOMAS MUSIC EDITOR

MAURA MCNEIL VIDEO EDITOR

DANIEL SANTOYO PODCAST EDITOR

KYM ROHMAN FACULTY ADVISOR

MIA FAIRCHILD MUSIC EDITOR

MEHANA BYRNE BLOG COPY EDITOR

RUBY JOYCE BLOG COPY EDITOR

OLIVIA ROBERTS STYLING EDITOR

MAYA CLAUSMAN STYLING EDITOR

NATALIE ENGLET SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

ANNA CURTIS ART DIRECTION EDITOR

AYLA FUNG PHOTO EDITOR

ZOE MAITLAND PHOTO EDITOR

ELLIE JOHNSON PRINT COPY EDITOR

BEATRICE KAHN PRINT COPY EDITOR

MARK MUNSON-WARNKEN PRINT COPY EDITOR

Letter From The Editor THE EDITOR

LETTER FROM

Dear Align Readers,

It’s hard to believe that after three years, I’m writing this letter to you now.

In March 2022 of my senior year of high school, I remember browsing the University of Oregon club list. I hadn’t even committed to enroll as a student yet. I saw Align at the top of the alphabetical list, and I immediately stalked the entire Instagram and website. I can’t imagine what the Editor-in-Chief at the time, Kaeleigh James, thought when she saw an email from 17-year-old me excitedly asking how I could join Align. I reread that email from three years ago and laughed at what a full circle moment this is.

When I joined the design team at the beginning of my freshman year, I could never have guessed where this journey would take me, but I am incredibly grateful to be in this position. Throughout the seasonal changes and growing pains I have experienced in the last few years, Align has always been a constant in my corner. I am forever thankful for what this community has given me.

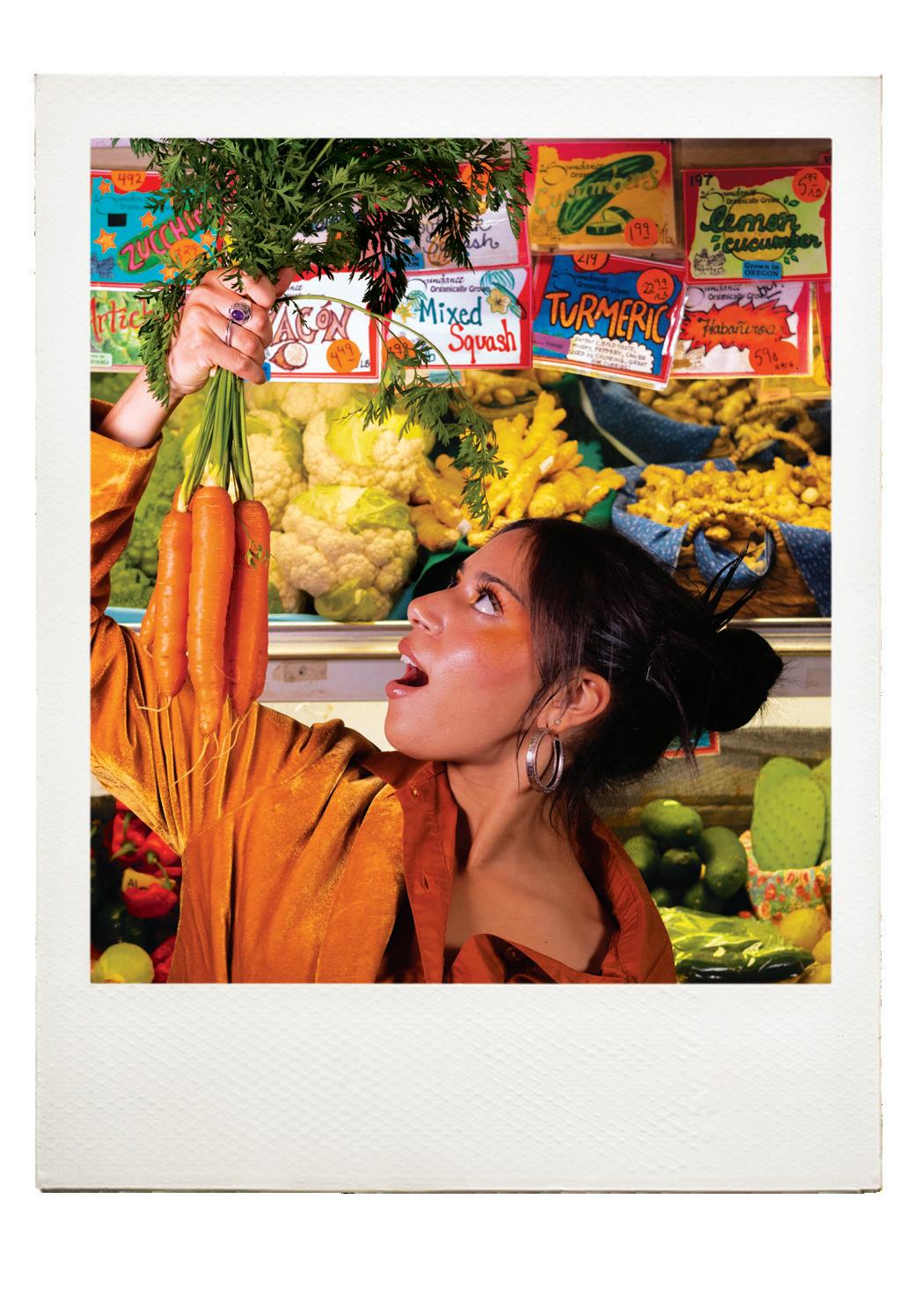

We chose Fruition to celebrate the fruits of labor through community, abundance, and warmth. The word has several meanings: to produce fruit, the attainment of something desired, and the realization of a plan. All of these ring true to this issue where we delve into themes of history, accomplishments, seasonal patterns, and the cycles of our lives. In times like now it is incredibly important to support and uplift those around us, and appreciate our unique traditions, givings, and networks that shape who we are. We hope that reading this issue will inspire your own personal harvest, and cherish what is special to you.

I am so grateful to Align’s hardworking members that delivered this issue. The contributions of every single person are integral to the success of this magazine, and I am so proud of the effort and creativity this team dedicates. This is the first issue I am publishing as Editor-in-Chief, and I will be savoring every second before the year is over.

Thank you to previous editors like Sydney, Eliot, Ainsley, and Ella. You taught me so much, and we miss you. Thank you to Align’s exec team and editors, you keep me afloat. And a special thank you to all of the fall 2025 members, returning or new, who showed up this term to make something amazing to start off the year.

I hope you enjoy Fruition.

Till next time, Stella Ranelletti

JOIN OUR TEAM

Applications open two weeks before the beginning of every term, and we publish three printed issues per year. Check our socials to know when applications are released.

Follow @align_mag on Instagram Read past issues and our digital content at alignmaguo.com

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Anathyn Burton

Aubrey Jayne

Aubrey Kunz

Ayla Fung

Bella Snyder

Carter Garrett

Hana Wittleder

Isabela Torres

Izzi Lipari Maxson

Jacob Mitani

Joaquim Gruber

Julian Ramirez-Sanchez

Ky Myers

Lac Nguyen

Maddy Lazarow

Megha Panikar

Piper Shanks

Sofia Moscovitch

Zoe Maitland

DESIGNERS

Allie Harakuni

Amelia Fox

Ava Klooster

Bryant Leaver

Drake Michael

Ella Kenan

Elliott Parsons

Evan Giordano

Iris Gray

Joey Matsuno

Kayla Chang

Liv Bourgault

Natalie Englet

Natalie Koski

Noah Gagnier

Porter Wollam

Ryan Ehrhart

Sadie Wehunt

Stella Ranelletti

STYLISTS

Abigail Ghio

Alyssa Samuel

Alyssia Truong

Annika Patil

Ava Kook

Carmen Peredia

Clarissa Perez

Diego Vasquez

Ella Hutchinson

Eve Haghighi

Francesca Overton

Gidi Batya

Karter Green

Nina Latto

Olivia Roberts

Quinn Vormbaum

Sophia Besaw

Tamayra Corpuz

Zoë Walkenhorst

Zöe Fruits

STAFF

ART DIRECTORS

Aamani Sharma

Ainsley McCarthy

Alexandra Bondurant

Angelika Stolecki

Anna Curtis

Anna De Sanctis

Audrey Stephens

Avery Wachowiak

Charlotte Miller

Cocoro Darby

Cori Markus

Danielle Collar

Elias Contreraz

Emily Casciani

Harper Meyer

Harry Nowinsky

Isabella King

Keiran Christiansen

Lela Akiyama

Lucy McCannon

Maura McNeil

Maya Clausman

Mia Fairchild

Ruby Joyce

BLOGGERS

Addie Jensen

Amelia Gaviglio

Anna Viden

Bridget Newman

Daisy Simpson

Elise Alvira

Frankie Little

Hannah Dean

Helen Bouchard

Helen Myers

Kellen Cox

Lindsey Pease

Mars G.A.

Minami Salas

Nahla Wilson

P.K. Rector

Phoenix Nwokedi

Sophie Butsch

ILLUSTRATORS

Ash Dunteman

Braylon Belloni

Ella Jaksha

Flavia Gjishti

Jackson St. Denis

Joey Bezner

Kent Porter

MaryClaire Lane

Natasha Korbich

Ruby Knott

Sara Spencer

Stella Ranelletti

Wallie Butler

Ying Thum

WRITERS

Amanda Lan Anh

Amelia Fiore

Anaya Lamy

Anna Liv Myklebust

Avery Wilson

Beatrice Kahn

Bridget Donnelly

Campbell Williams

Catalina Kurihara

Ceci Cronin

Celia Hutsell

Claire O’Connor

Cora Callahan

Drew Turiello

Ellie Johnson

Emese Bracamontes Varga

Emily Hall

Emily Hatch

Fiona McMeekin

Hannah Kaufmann

Hope Call

Julie Saive

Keira Wilson

Khushi Mishra

Kiana Heilfron

Kimberly Bowman

Libby Findling

Liv Vasquez

Mark Munson-Warnken

McKenzee Manlupig

Mehana Byrne

Meileen Arroyo

Niobe Hauger

Skylar DeBose

Sophie Turnbull

MUSIC CONNOISSEURS

Anja VanderZee

Ben Cohen

Bianca Lewis

Danahea Heart

Ellie Acosta

Fiona Ryan

Grace Sinkins

Henry Martin

Isabella Thomas

Lauren Gross

Lucy Fromm

Mia Fairchild

Moréa Manson

Sylvie Rokoff

VIDEOGRAPHERS

Adrian Beltran

Matias Crespo

Nathan Wooley

Sam Browdy

Tallulah Hutchinson

MODELS

Abigail Ghio

Ailsa Huerta

Alyssa Samuel

Anathyn Burton

Andrea Rivera

Anja VanderZee

Annika Patil

Arden Brady

Ash Dunteman

Ava Kook

Avery Wilson

Bella Ahlheim

Bryant Leaver

Carmen Peredia

Clarissa Perez

Danielle Collar

Davis Lester

Drew Turiello

Elias Contreraz

Eliyah Syrai

Emily Casciani

Emily Hatch

Eve Haghighi

Fiona Ryan

Francesca Overton

Harper Meyer

Helen Myers

Isabella King

Isabella Razura

Jackson Jones

Jacob Mitani

Jenneh Conteh

Julian Ramirez-Sanchez

Katie Lantz

Kayla Chang

Khushi Mishra

Lily Mock

May Ishida

Maya Gangishetti

Meara Stephens

Mika Maii

Mila Brucato

Mina Gushee

Monty Gunnell

Moréa Manson

Nadia Rouillard

Naseeb Reyes

Ossean Barbès

Parker Kirkwood

Rose Ruhnke

Ruby Knott

Sage Murphy

Sailor Lombardi

Sophia Soleil

Stella McShane

Will Ficker

Zoe Maitland

Zoë Walkenhorst

PODCASTERS

Daniel Santoyo

Hannah Bard

Matthew Bedrosian

Sophia Soleil

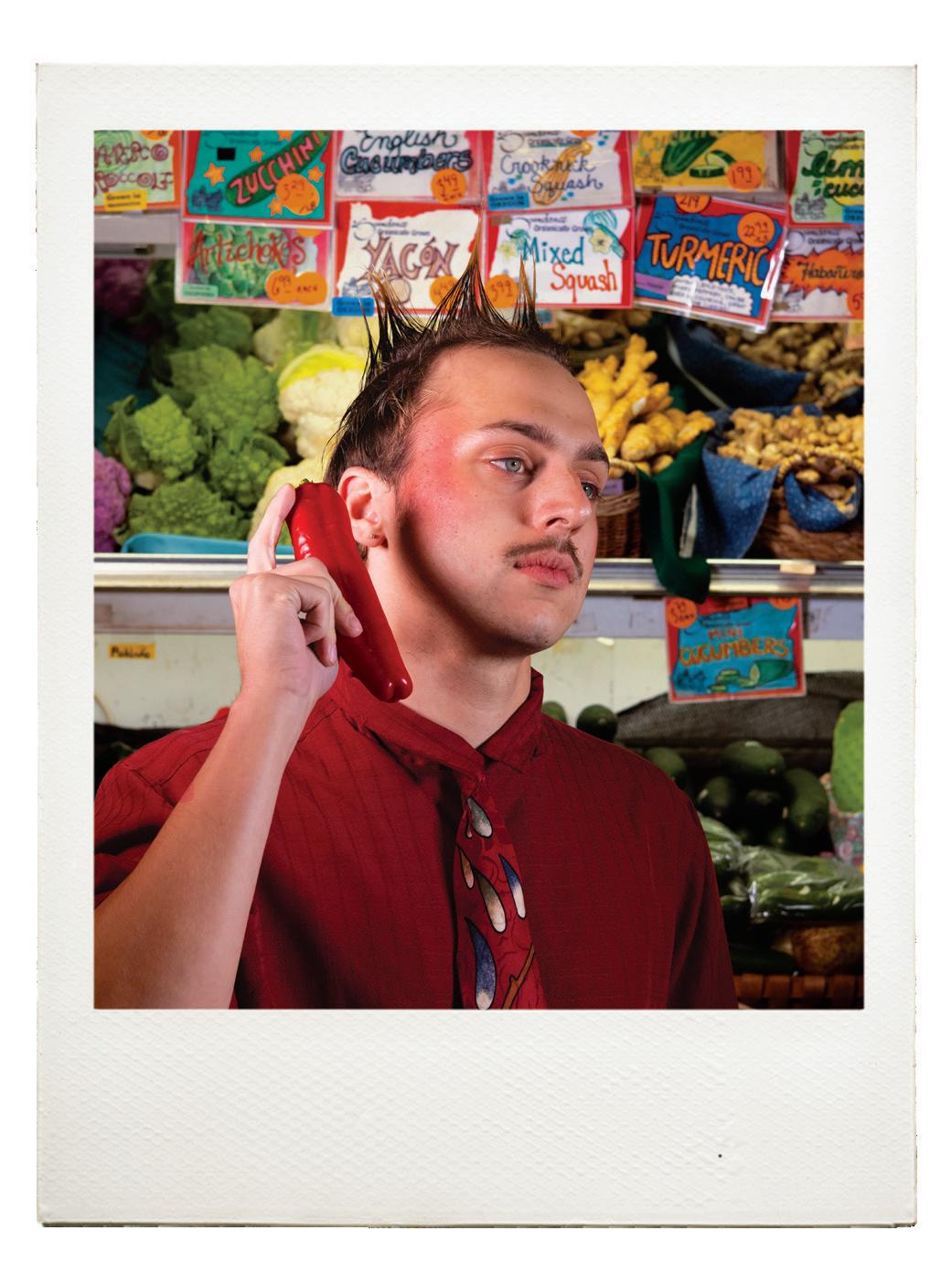

ART DIRECTOR KEIRAN CHRISTIANSEN

PHOTOGRAPHED BY ISABELA TORRES

MODELS EMILY CASCIANI, KATIE

LANTZ & ANJA VANDERZEE

STYLIST ZOE FRUITS

SEE MORE ON PAGE 60

fruition playlist listen

See you on monday (you’re lost)

please, please, please, let me get what i want

BALLAD OF SIR FRANKIE CRISP (LET IT ROLL)

YOU CAN’T ALWAYS GET WHAT YOU WANT

This must be the place (naive melody) summer wine empires never know cherry-coloured funk cowgirl float on vienna

THANK YOU

CHIQUITITA

DREAMS

STARMAN

CHAMPAGNE SUPERNOVA i guess incomprehensible

TAME IMPALA

THE SMITHS

GEORGE HARRISON

THE ROLLING STONES talking heads

NANCY SINATRA & LEE HAZLEWOOD

JESSICA PRATT

COCTEAU TWINS

ORA COGAN

MODEST MOUSE

BILLY JOEL

BONNIE RAITT

ABBA

THE CRANBERRIES

DAVID BOWIE

OASIS lizzy mcalpine big thief

In addition to playlists, the Align Music Team also publishes music blogs available at alignmaguo.com. Here are some highlights:

Everyone Has Their Goliath BY

FIONA RYAN

The Heartbeat Continues: Indigenous Music and Sovereignty Today BY DANAHEA

HEART

How “Album Eras” Transformed the Pop Music Scene BY

ELLIE ACOSTA

Video

Video`

The Align Video Team has worked throughout the term to shoot projects capturing the feeling of Fruition. All videos are available on our website and @align_mag on Instagram, with more to come soon!

Here are some of our favorites from this issue.

“Align Asks”

VIDEOGRAPHER MATIAS CRESPO

ART DIRECTOR ANNA DE SANCTIS

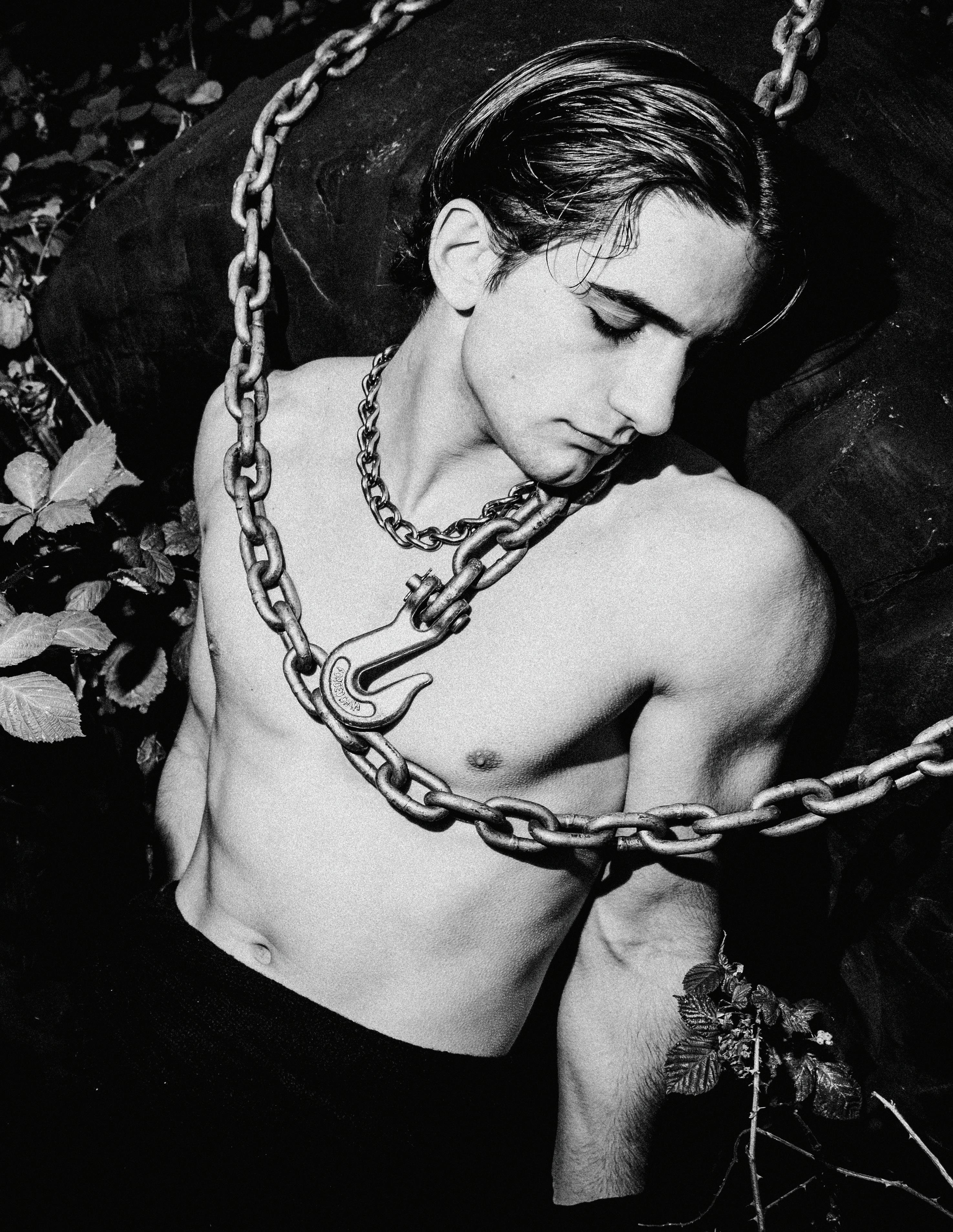

“Fall Crossed Lovers”

VIDEOGRAPHER SAM BROWDY

ART DIRECTOR ANGELICA STOLECKI

MODELS BRYANT LEAVER & ROSE RUHNKE

Align on Air Align on Air`

Our official podcast, Align On Air, produces a variety of content from interviews to round table talks. Visit our Spotify to listen to the new episodes: Discussing Fashion Around the University of Oregon Roundtable Talk with Align’s podcast team.

Future of Fashion Club (with Lara Clute) Podcast editor Daniel Santoyo interviews UO Fashion Club president Lara Clute on the club’s success and future plans.

ART DIRECTOR EMILY CASCIANI

PHOTOGRAPHED BY BELLA

SNYDER

STYLIST DIEGO VASQUEZ

MODEL ALYSSIA TRUONG

The QuieT arT of gleaning a home away from home reimagining relaTionships all nine lives aT once archiving an archive

The Tales of appalachia women of The earTh living arT eve’s daughTers six seeds public arT...for who?

Threads ThaT remember

The beauTy in unseen individualism in memoriam: monsTerhouse poppy in The garden

The harvesT we wear

The packaging of persona

This wouldn’T be funny in The homeland

The dream ThaT ouTlives The dreamer could heaven ever be like This? flesh and memory sprouTing a new day darkness losT under arTificial lighT

The wiTches’ ledger a legacy of laughTer and learning censored sea, swallow me

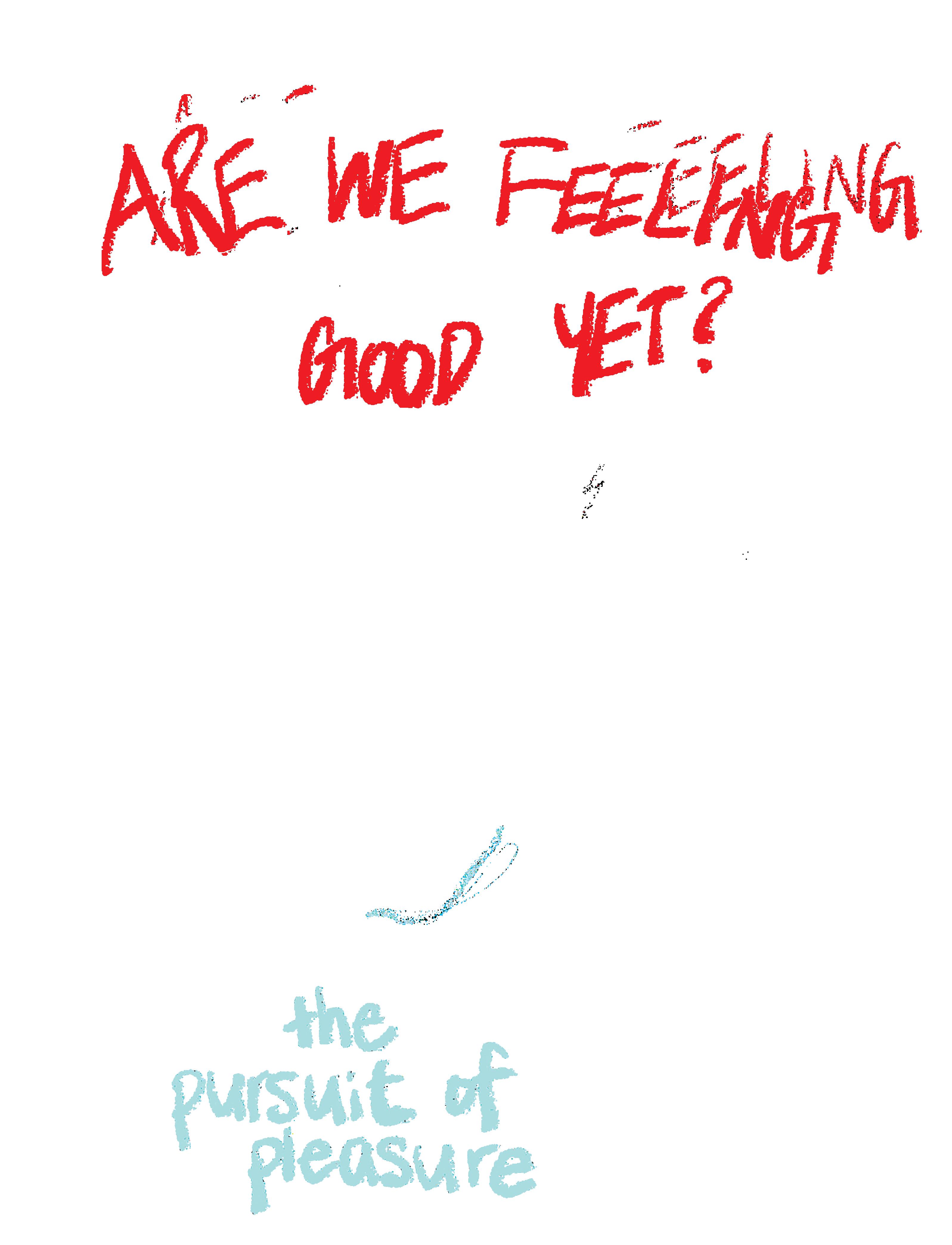

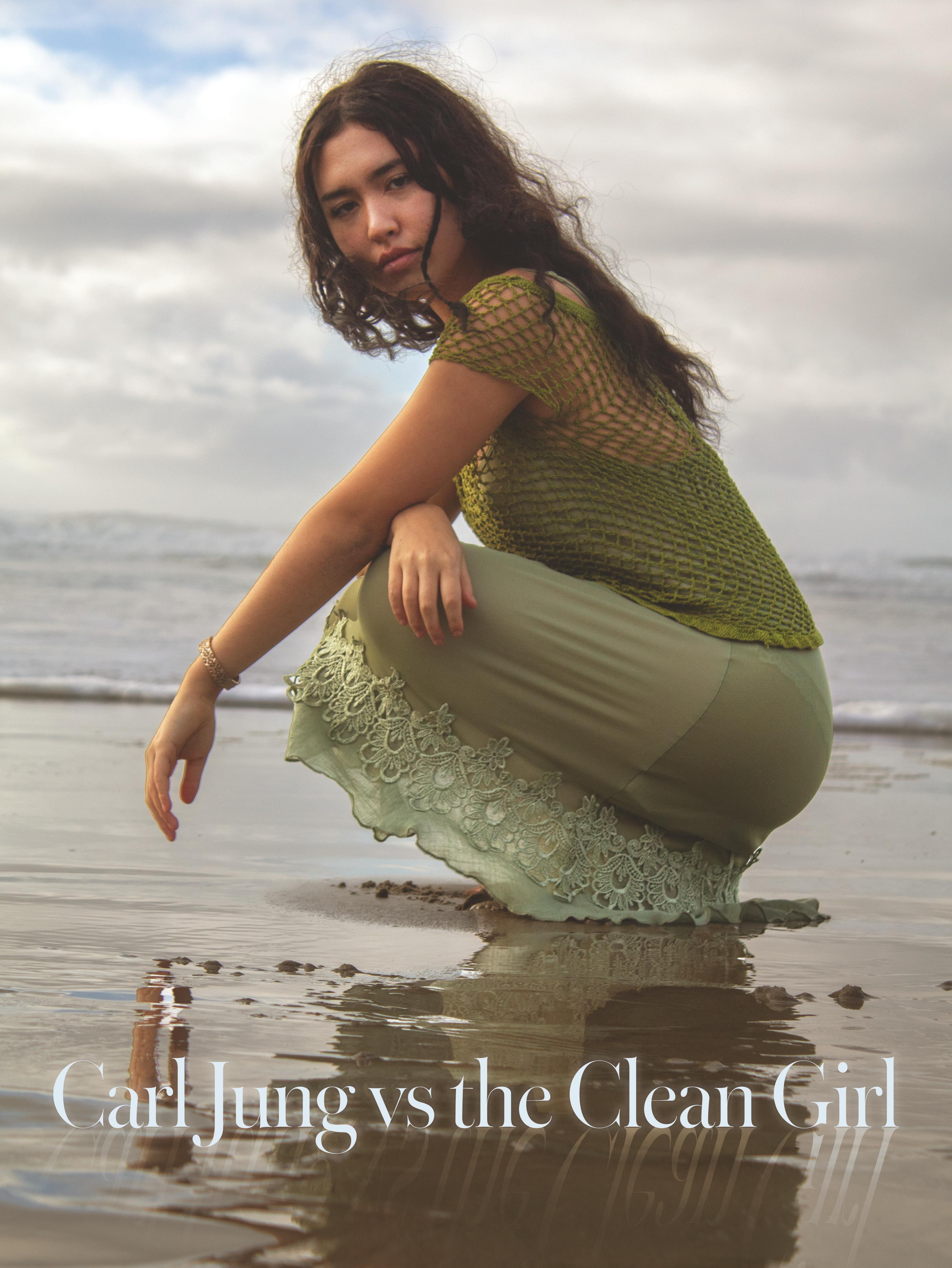

The rush To nowhere a bloom drenched in blood okToberfesT a seaT aT our Table are we feeling good yeT? carl jung vs The clean girl fruiT symbolism in media

JOHNSON

ART OF

Gleaning QuietTHE

How the practice of gleaning is a way to notice, preserve, and endure.

In the Musée d’Orsay, a painting depicts three women bending towards the earth. They are gathering wheat left in a field after a harvest. The women in Jean-François Millet’s “The Gleaners” are fixed on their labor — bending, reaching, and collecting. They glean wheat to ensure their survival, to ensure they have enough sustenance to make it through the winter. To glean, from the Old French word “glener,” means to gather the leftover grain after a harvest, to collect what remains once abundance has passed. This painting serves as an ode to unseen labor and endurance. In 1857, when peasant labor was rarely dignified, Millet turned survival into art.

More than a century later, Agnès Varda captured similar gestures with a camera rather than a brush. In her 2000 film, “The Gleaners and I,” Varda travels through France in search of modern gleaners — people who salvage what has been discarded. She encounters individuals who collect misshapen potatoes left in the fields after a harvest, and those who dumpster dive for survival.

“The Gleaners and I” develops a philosophy of noticing. Throughout the film, Varda gleans moments in time, collecting fragments of a country, of a people, and of herself. She asks what it means to glean what is left behind, not just from harvests but from time itself.

In the film, Varda encounters many kinds of gleaners. Along a rural road, she meets a group of people living in trailers at the edge of farmland. Dependent on welfare and ousted from the city, they glean to survive. They gather vegetables in fields that are still edible but deemed unfit for sale. At night, they visit grocery dumpsters, rescuing discarded meat and fish that are past their sell-by dates. The food is not rotten, only thrown away to meet consumer standards. For these people, gleaning is a necessity, a way to survive off of what society deems inadequate.

However, not everyone gleans out of necessity. One man, employed and housed, gathers food from trash bins out of principle. He rejects the endless cycle of buying, discarding, and replacing. For him, gleaning becomes a protest and an ethical act against overconsumption.

Others glean for their artistic pursuits. Varda visits Ukrainian-born artist Bodan Litnianski, who has built a sprawling palace from discarded materials. Every castoff: dolls, toy cars, broken ceramics, rusted metal, becomes part of a mosaic surrounding his home. His work transforms waste into wonder, proof that discarded items can still hold beauty.

“The Gleaners and I” is unique in its reflexive quality. Varda is an active participant and subject in the film. She positions herself as a gleaner of images, stories, and herself. She turns the lens towards her own hands, and she treats them with the same care she gives to each of her subjects. In this, she is gleaning herself and preserving her own beauty and purpose. The attention paid to her wrinkled, aging hands becomes a way of honoring what persists as usefulness begins to fade.

Gleaning, then, extends beyond a field or a dumpster. It becomes a way of being in the world, a way of noticing, and a way of honoring what might otherwise be overlooked. We often walk through life carrying trauma, insecurities, and fear. But we forget the

fragments of conversation, lingering eye contact, and small gestures of love. These remnants become a quiet archive that sustains our daily nourishment.

Modern life rarely allows this kind of attention. Our collective consciousness values the harvest, but not the gleaning. It prioritizes the product, but not the process. Yet value accumulates in these smaller gestures, the gathering and the remembering. Varda’s camera often lingers a few seconds after a scene should have ended, as if reluctant to look away. That delay is deliberate. It insists that attention is a form of care.

The gleaners painted by Millet persist today, though the fields have changed. Varda’s camera finds them in dumpsters, in fields, and in the streets of Paris. Modern gleaners remind us that value does not vanish when usefulness fades. To glean is to keep noticing, and to find purpose in what remains. Like the women in Millet’s field, Varda’s gleaners show that attention itself is a form of endurance.

She turns the lens towards her own and she treats them with the same she gives to each of her subjects.

hands,

care “ ”

PLAYLIST CONNOISSEUR ELLIE ACOSTA

A home away from home

Growing up, I wasn’t aware of the cultural aspects that surrounded my everyday life. The paintings, photographs, and figurines that adorned my home, the ill verses of hip-hop greats blasting from our kitchen speaker, the smooth voices of Black women, the aromatic scents of my father’s soul food recipes, the rainbow array of books that told my people’s history and resilience, and the role models that enveloped our living room TV. Each of these cultural aspects shaped the first community I was a part of — my family.

The foundations of culture and community have forever shaped the people I surround myself with, the opportunities I undertake, the morals I follow, and the stories I tell. For much of my life, I obliviously incorporated these lessons into my life. It wasn’t until I began writing my personal essay for college applications that I really sat and asked myself what and who have shaped me into the person I am.

Over the past two years, my communities and cultural understandings have shifted, grown, and persisted. As we transition into a new school year, from summer into fall, I find myself reflecting on the newfound cultural understandings and communities I found during my six weeks abroad in Ghana this past summer.

As a Black woman who grew up in the predominantly white city of Portland, Oregon, for most of my childhood, it was difficult to find communities outside of my home with people who looked like me. Yet, within my home, I was constantly reminded of the lesson, “I’m Black, and I’m proud.”

Although the colonizer’s enslavement of my ancestors prevents me from knowing the geographical roots of my family history, I have always known who my people are. I knew my roots were in Africa.

I knew of my people’s long resistance to white supremacy and colonization. I knew the beauty of my people’s hair — its versatility, its kinks, its coils, its skin-tight twists and braids. I knew the comforting aromas of soul food that quite literally feed the soul. I knew the sounds of jazz instruments, the breathtaking voice of Aretha Franklin, the upbeat rhythms of Michael Jackson, and the rap flows of Nas and MF DOOM. I know that each of these is a part of me, and I am beyond proud of it.

Yet my knowledge and access to all of these would not have been possible without the persistence, strength and pride of my ancestors. Their determination to never let the other side win, to show their children where and who they come from and to be unapologetically Black, all of this and more, led me to the homeland.

Visiting Africa showed me how and why someone can feel at home in a continent they had never set foot on, or find community in people who were strangers just days before. I’ve always felt that something was drawing me to Africa. I felt the strength, knowledge and love of my ancestors pulling me home.

For five weeks in Ghana, I interned at a company called Zed Multimedia. The small, tight-knit community at Zed quickly embraced me. We bonded on similarities and differences, as we learned to understand how so much can change, so much can remain the same, and still bring us back to this place. Each day, I would go to lunch with my coworker, Praisewell, spending $2 to $5 on a Ghanaian dish. I would be repeatedly humbled as I mistakenly chewed on Fufu or failed to eat rice with my hands.

I quickly discovered my favorite dish: Kenkey with okro stew. The familiarity of my favorite vegetable, okra, reminded me of home. I explained to my Ghanaian coworkers how we often deep fry okra, and we laughed at the absurdity of American diets.

The newsroom at Zed was not the work environment that I was used to. My coworkers were some of the most hardworking people I’d ever met, working more than 12 hours a day, writing several stories for print and sometimes leading the radio broadcast. Despite the stress of everyday obligations, the newsroom culture reminded me of my family, of home. The elders’ lengthy storytimes that silence the room and are passed down from generation to generation made me feel at home. The singing outbursts from the most tone-deaf family member reminded me of home. The harmless debates that would lift aunts and uncles out of their seats as they argued over the best Ghanaian dish brought me back home. The feelings of Black joy as people who looked like me, who spoke like me, and who understood me, made a place 7,517 miles away feel like home.

As I sat at my desk at Zed, I was brought back to family reunions in my grandma’s cluttered apartment in Yonkers, New York. I recalled late-night dinners on random school nights in my childhood kitchen in Portland, Oregon. I was reminded of my grandparents’ backyard in Harvey, Illinois, where we caught fireflies and danced to the chirps of cicadas. Despite being thousands of miles from the only place I had known, it all felt so familiar. My ancestors, my culture and my community brought me here. I was home.

WRITTEN BY SKYLAR DEBOSE ILLUSTRATED BY ELLA JAKSHA

Reimagining

Relationships

WRITTEN BY HOPE CALL

ART DIRECTOR MAYA CLAUSMAN

PHOTOGRAPHED BY SOFIA MOSCOVITCH

MODELS MONTY GUNNELL & MINA GUSHEE

STYLIST OLIVIA ROBERTS

DESIGNER ALLIE HARAKUNI

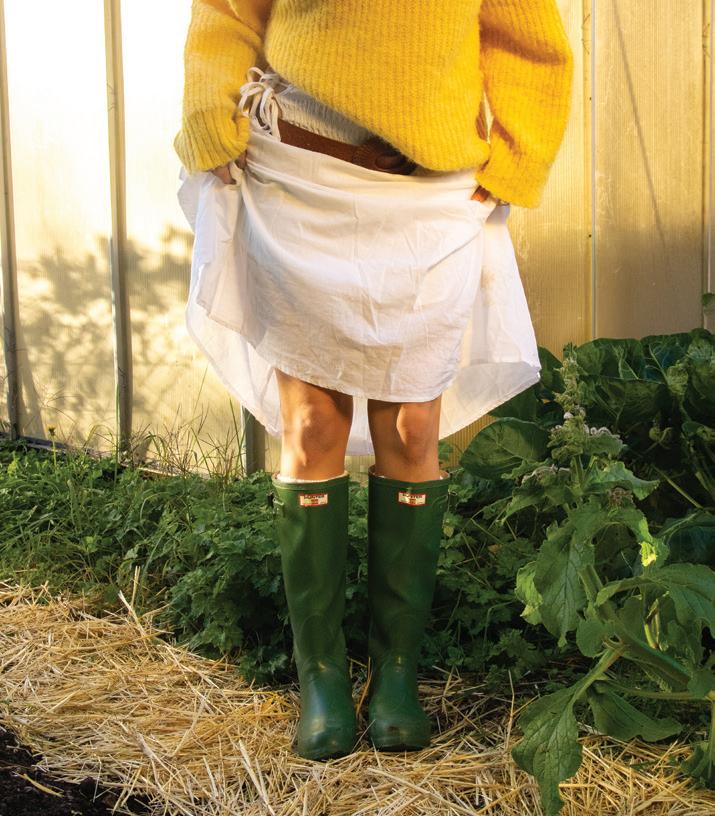

HOW ARE YOU TENDING TO YOUR GARDEN?

Wproudly over the fruits of their labor — a celebration of individual success. But no harvest exists in isolation. In nature, trees share nutrients through underground root networks, fungi sustain forests through quiet reciprocity, and no crop ripens in the same way. What if we viewed our relationships this way: as living ecosystems rather than as transactions?

Western capitalist ideologies have conditioned us to see everything — products, services, and even people — through a transactional lens. This mindset pushes us to frame our relationships around the question: how little can I give for the maximum payout? It’s a way of thinking that turns connection into currency and reduces care into an investment strategy. Relationships have become measured by what an individual alone can gain, capitalizing on the company and compassion of others.

However, Indigenous teachings offer a different truth, one rooted in reciprocity and relational balance.

I grew up in a small town in rural Alaska, where Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian values deeply shaped my perspective. I was taught that everything in nature gives and receives in equal measure, an economy where gratitude, not greed, sustains life. To take from the earth, or another person, without giving back is to disrupt the very cycle that keeps everything alive. This same principle applies to platonic and romantic relationships and our broader communities, a worldview where growth is communal, not competitive. In an era where relationships have become commodified and monetized, pause to consider: what are the fruits of your relationships, and how are you tending to your garden?

Some relationships require steady watering: consistent check-ins and small acts of care. Others need pruning — setting boundaries, engaging in difficult conversations, and sometimes even release. Tending does not always mean control; sometimes it means stepping back and allowing growth to unfold on its own. And just as one invasive weed can damage an entire harvest, toxic patterns left unchecked can ripple through relationships for seasons to come.

Like the seasons, relationships also have natural rhythms. Spring brings new connections and summer offers warmth and abundance. Autumn is a time to reflect, gather lessons, and express gratitude, while winter marks endings, making space for renewal. We often fear a relationship’s “winter,” seeing endings as signs of failure. But just as a field must lie fallow to regain its strength, seasons of rest are vital for future growth. And endings do not signify fruitlessness — there are

always lessons to harvest, even from relationships that have run their course.

Historically, harvests were never about individual survival. Festivals and rituals celebrated the collective joy of many hands sustaining one another. In contrast, today’s Western capitalism glorifies the “self-made” myth, leaving us isolated even in our most “successful” seasons. Whether one tends a garden or a human being, nothing grows alone. Create the space and time to celebrate those who nourish you: the friend who listens without checking the time, the partner who makes you breakfast in the morning, the professor who saw potential in you before you could see it in yourself. These are the people who keep you alive, not in a biological sense, but a spiritual one.

The current cultural mindset may tell you to hoard your energy, your time, your affection. Don’t listen to it. Connection was never meant to be transactional. It was meant to be symbiotic, cyclical, and endlessly regenerative.

I want my garden to be sprawling and colorful, bursting with the biodiversity of care, honesty, laughter, and loss. But it starts with you. To receive, you must first give. To be full, you must first fill others. To have a village, you must first be a villager. Because that’s what real reciprocity is — not keeping score, but

The Eye of Ra Bastet

WRITTEN BY JULIE SAIVE

ILLUSTRATED BY ASH DUNTEMAN

DESIGNER NATALIE KOSKI

ALL NINE LIVES AT ONCE:

On mummified cats, displacement, and what it means to preserve a moment in Tokyo

Iheld up the dryer, raking my fingers through my scalp, hair whipping wildly as the hot air dried my braids. It’s raining in Tokyo. Actually, more accurately, it was as if the skies had opened up and a bottomless bucket was being dumped on the city. As I sat in the dainty blue chair pulled up to my room’s vanity, my entire body churned with displeasure. I had already planned to get out of Ginza and make my way to Shibuya, but the rain coupled with the humidity called those plans into question.

I turned off the dryer. My hair was dry enough and it wasn’t as if I was going out today. I traded my bathrobe for clothes and left my hotel room for the all-inclusive breakfast. Here I was the only foreign person. The hotel served a crowd of people on business trips. It was nine in the morning, and everyone was dressed for work. I found it fascinating how so many people in one room were dressed so similarly. I mimicked the look to fit in a bit better: white blouse, black pencil skirt with polka dots on the bottom, and most regrettably, my black New Balance sneakers.

When I stepped out of the elevator, there was a long table in the lobby with various flyers. One stuck out immediately. A collage of ancient Egyptian artifacts, all gold and royal blue. It was an exhibit for Ramses II. I grabbed one and took it into the dining room, copying the address into my phone. As I sipped my too bitter morning coffee and chewed on an under baked blueberry muffin, I decided that I would take the journey to the exhibit. It was something dry for me to do.

Navigation told me it would take about an hour. It took me forty minutes more. Somewhere during the second transfer, I realized I was going the wrong way.

When I finally arrived, the building emerged through Tokyo’s grey curtain of rain like something surfacing from underwater. Inside, the air was climate-controlled, sterile. I stood off to the side so I could read the English translations on the screen, and walked at the back of the group so as not to get in anyone’s way. The tour moved through gilded sarcophagi and hieroglyphic tablets, jewels, and organ boxes, but I lingered behind, drawn to a different section.

The mummified animals. The cats.

I spent a while there, pulling out my phone to snap pictures of the small buddled creatures behind glass. They were smaller than I expected, some no bigger than my forearm. Who had sacrificed them? The placard explained that they were offerings to Bastet, “the essence of femininity,” goddess of protection and fertility. These cats, with their mythical nine lives embodying resilience and rebirth, had been given only one. Cut short deliberately, wrapped carefully, buried with intention. All to curry favor for someone else’s afterlife.

There was something ethically violating about standing in the exhibit. These weren’t artifacts in the way a pot or tool becomes an artifact. These were someone’s sacred insurance policy, their desperate bid for immortality, now behind glass for a rain-soaked tourist taking telephone photos. The Ancient Egyptians went to extraordinary lengths to preserve what they believed would sustain them beyond death — bodies, stories, animals. The Book of the Dead was their instruction manual for preservation, for carrying accomplishments and blessings across the ultimate threshold.

And here I was, a foreigner twice over — in Tokyo, viewing Egyptian treasures, participating in a kind of grave robbery I’d paid lofty admission for. I felt slimy. I stayed anyway.

Fruition, I realized, isn’t an endpoint but preservation. It’s the ongoing process of harvesting what matters and carrying it forward even when the carrying feels uncomfortable. The Ancient Egyptians understood this. They entombed everything they hoped to keep.

I thought about my own preservation efforts in writing this about my encounter with the mummified cats. This moment, mummified in words. The photos on my phone were inadequate translations of my fascination and disgust. Like the English subtitles I’d been reading all day they were slightly off from the intended meaning. I had gotten lost on the trains. I stood in the pouring rain. I had worn the wrong shoes. And now I was trying to wrap this experience carefully, to carry it forward, to make it mean something beyond itself.

Outside, Tokyo’s rain had finally stopped. I was still out of place, still lost, still landing on my feet. Still living all nine lives at once.

LINDBURG NANCY LINDBURG

Nancy Lindburg looked out to her verdant garden in the suburbs of Salem, Oregon. I sit next to Lindburg on a wicker chair; my fingers poised over the keyboard. A steaming cup of decaf coffee on a porcelain tray sits in front of us, alongside two manila folders. Each folder is marked with a six by four-inch sticker, reading in capitalized letters:

OREGON PROJECT NEWGATE.

Conceptualized by Thomas Gaddis, an Oregonian prison reformer, Project NewGate was funded in 1967 by President Lyndon Baynes Johnson’s Office of Economic Opportunity. The program provided incarcerated students with a pathway from taking classes in prison to taking college classes on the campus. The NewGate model, piloted at the Oregon State Penitentiary, was adopted by six other states before federal funding ran out in 1974.

Nancy Lindburg was originally just a name on a piece of institutional correspondence I discovered in the University of Oregon Special Collections; Lindburg volunteered to teach art to convicts deemed irredeemable because she recognized their humanity. This spring, I established contact with Lindburg through LinkedIn. She listed her job as a retired arts administrator, which fails to capture the quintessence of her career as a public arts educator. Color and imagery are central tenets in her worldview, qualities that cannot be represented in the ‘experience’ section of a job page.

This year, while cleaning her garage, she discovered two folders from 1972, containing her NewGate class lists. Information is scribbled in the margins: checkmarks indicating attendance and remnants of eraser dust around grades once changed, signifiers of the malleability of the prison education program. It was an organic process. Through creativity and imagination, Lindburg worked to supplement the isolation and inhibition that her incarcerated students faced.

Lindburg’s aspiration to improve her pedagogy, alongside her deep passion for accessible education, is evident in her musings. She lists the things she would do differently for class in the final blank pages of her folder, “give short papers every two weeks. Oral research — share with class. More discussion.”

The statements found within her institutional folder are both elaborate and concise. Lindburg’s sentiments, written during the winter of 1972, articulate a plan to continue refining her methods to the diverse population of incarcerated students. Her musings elucidate her philosophical approach to life and to education. She tells me, “we are all mark-makers.” While her courses are centered around art, the ideas of sharing research with others and communicating ideas beyond oneself transcends the subject.

Actualized through revolutionary practitioners such as Lindburg, Project NewGate was developed from an idea.

Establishing rehabilitation in an innately punitive prison requires dedication and creativity. Lindburg’s ingenuity is evidenced through the props she brought into the Oregon State Penitentiary for her classes. Items like an eggbeater and a child’s tricycle were props for her art class. In a prison, a toy and a kitchen tool can become weapons. Lindburg took the risk and carted these props into the penitentiary. What at first glance may be viewed as a violent instrument by corrections officers sparks a remarkable still life drawing. Her disobedience facilitated creativity for incarcerated students who otherwise could not access such inspiration for their artwork.

Lindburg graciously gifted me her yellow manila NewGate folder. It rests on my desk, a physical reminder of the continuity of the idea of Project NewGate. The rigidity of the institutional NewGate folder, which required Lindburg to take attendance and submit final grades for each student, is contrasted by the freedom it represents. Blank paper appends the folder, filled with reflections of her courses. In red ink, she penned reflections on her courses, and on humanity more broadly. Her desire to articulate intangible ideas permeates from the page. Lindburg writes, “The value of art for a civilization lies in its power to communicate feeling and intuitions that would otherwise remain suppressed.”

The history of Project NewGate has thus far been untold. Covered by dust, its legacy was forgotten by the University of Oregon, the very institution which shaped it. By virtue of speaking with me in her home and impressing her folder upon my hands, Lindburg humanizes the prison education initiative. In 1972, the folder passed through the doors of the Oregon State Penitentiary. This August, the folder passed from the hands of a prison educator to a curious history student. Now, the story of the people who characterized Project NewGate emerges from the margins, no longer suppressed.

WRITTEN BY BEATRICE KAHN

ART DIRECTOR RUBY JOYCE

PHOTOGRAPHED BY JACOB MITANI

STYLIST ANNIKA PATIL

MODELS MIKA MAII, HARPER MEYER & ASH DUNTEMAN

DESIGNER PORTER WOLLAM

Folklore of America’s oldest region and its roots in history

In the sprawling hills of the Appalachian Mountains, centuries of stories have been told about strange monsters, eyes that glow like the moon, and mysterious screams heard from the forest. Social media has discovered these tales and become fascinated with their mythos, however, beneath the theories and retellings of scary fables lies a community overlooked by its government and isolated from the country. What is it about Appalachia that makes it infamous for monsters while its residents suffer from disparities?

Appalachia refers to a region of the United States comprising 423 counties across 13 states, from southern New York to northern Mississippi. One of the oldest regions of America, it is renowned for its rich folklore, natural beauty, and socioeconomic problems. Across generations of Appalachian communities, the folklore of creatures hidden in the mountains and anomalous occurrences has persisted. These stories have found a new audience through the internet, leading to an increase in their popularity and the expansion of their mythos. The attention usually associated with the region focuses on its high levels of poverty, lack of education, unemployment, and inadequate services and infrastructure.

One of the most celebrated cryptids of Appalachia is the Mothman of Point Pleasant. In 1966, a couple in West Virginia reported to police they had seen a creature standing at the end of a road near a World War II munitions plant. The witnesses described seeing a large, seven-foot-tall, muscular man with white wings and red glowing eyes. They were unable to make out its face, given the hypnotic effect of its eyes, and said the creature flew after them

as they drove away. Over the next few days, people began reporting sightings after the story was covered in a local newspaper, where the creature was dubbed “Mothman.” After a horrific bridge collapse in December 1967, where 46 people died, these sightings stopped, yet some claimed to have seen Mothman at the scene. Although its origins remain unexplained, Mothman has become a mascot for the town of Point Pleasant, where an annual festival and museum dedicated to the creature are held.

For decades, reports have surfaced of odd, sporadic lights appearing on Brown Mountain in North Carolina. Some say these lights move slowly, while others describe the lights as making quick, bursting motions, with the orbs appearing in different colors. The first sighting of the Brown Mountain lights is often debated. The first alleged sighting was in 1771 by a German engineer, John William Gerard De Bahm, who wrote about the lights in his diary. Others claim that the lights were first seen during the early 1900s.

A federal government investigation in 1922. concluded the lights were nothing more than distant train lights. Many who research the lights say that the sightings predate the introduction of electricity in the area, discrediting the train theory.

Either way, the consistency in sightings of the lights and ongoing observations to this day make the Brown Mountain lights all the more elusive.

While the local folklore of the region is worth dissecting, it’s hard to delve into these mysteries while ignoring the conditions of the area. Appalachia

has experienced depressing amounts of poverty, with a higher rate of unemployment than most of the country. The region’s once-booming coal/steel industries are no longer, earning it the nickname Rust Belt. These towns are severely underfunded in terms of social, economic, and educational expansion. They lack the capacity to maintain public infrastructure, attract business opportunities, or provide the medical services necessary to sustain a growing population. Residents are forced to hunt for food or travel 40 miles to the nearest Dollar General to eat. The lack of opportunities for these communities makes it easy to stereotype Appalachians as uneducated, mysterious recluses. Characterizing them in this way certainly aids in setting the scene for these stories while making it easier to ignore the real horrors of the region as part of the mystique.

If Appalachia residents had the resources needed to thrive, the same locals who were passed down these generational legends could be the ones capitalizing on them, creating their own narrative about the region and its inhabitants. I hope the next time a story about Appalachian folklore comes across our feed, we pay closer attention and advocate for Appalachians so that we can hear their myths for another 100 years.

WRITTEN

BY

ILLUSTRATED

AVERY WILSON

BY

JACKSON ST. DENIS DESIGNER

AND THE BIG, TERRIBLE DEVIL THAT IS FEMALE AUTONOMY

WOMEN OF THE EARTH

Before the birth of organized religion, humans prioritized connection with the earth and all things born from it. Nature worship is considered the most primitive source of spirituality, before industrialism and the digital age; landscapes, resources, animals, and all mediums of natural beauty had a stake in the overall flow of the universe. Some women, traditionally bound to the role of gatherers, have used these natural resources as a means of curing illness and performing rituals for good fortune. These women were commonly described as “wicce,” the Old English term for witches.

History hasn’t been kind to them. One of the most wellknown instances of this is the European witch trials that took place during the 16th and 18th centuries, in which around 100,000 women, men, and children were accused of witchcraft and prosecuted. Between 40,000 and 60,000 of these individuals were executed, and around 75-85 percent of them were women. These “witch hunts” were fueled by the Protestant and Catholic Churches’ dominating narrative, socioeconomic hardship brought on by war and famine, and fear of powerful and independent women.

One of the earliest records of witches is in the Bible’s Book of 1 Samuel, which was thought to have been written between the 10th and 7th centuries B.C. Many other Old Testament verses condemn witches, such as Exodus 22:18, which commands, “thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.”

Witches have always been a threat to patriarchal religious structures. And from its very conception, the Church has vilified women like them. Stories like Adam and Eve, wherein Eve succumbs to evil due to assumed malevolent values, helped shape misogynistic religious views that still carry weight today. Christian institutions have historically portrayed women as morally fragile creatures, and that there is no evading the sin woven into their DNA. Since witches were “agents of Satan,” femininity indicated an inherent vulnerability to his manipulation.

The Church’s prejudice wasn’t exclusive to women. During the 16th-century colonization of the United States, many Native Americans practiced beliefs akin to what Europeans labeled as witchcraft, incorporating healing abilities and supernatural forces. They dismissed Indigenous spiritual traditions as inferior, especially those that upheld respect for the natural world. Using piety as justification, they drove the persecution and assimilation of Indigenous peoples by outlawing their spiritual practices and systematically destroying their way of life.

Now, after the centuries-old storm of witch hysteria has been pacified, a powerful desire to connect with nature and embrace unchurched spirituality has emerged. Astrology, numerology, and crystals are heavily popularized through the accessibility of social media — they are also mediums of witchcraft. While crystals may journey from unethical

mining practices to the shelves of Urban Outfitters, they are watched by the public eye nonetheless.

People yearn to be grounded, to live a life more substantial than the capitalistic nightmare that is being a human today. They don’t want benign structure; they want, however small, a connection to the possibility of something naturally fulfilling. Still, crystal-loving, tarot card-reading, astrology-believing women are scrutinized for their beliefs, written off as tacky or moronic. It seems that any form of female spirituality is inherently unsavory when deviating from the moral order of Christianity.

Witchcraft allows people to both exclude themselves from society and connect with the essential fabric of the earth alongside each other. Covens, groups of witches, will gather to perform rituals and celebrate Pagan holidays. Outside the bounds of normalcy, these groups have found community within their own isolation. They encircle bonfires for Beltane (an ancient festival celebrating the arrival of summer) and drink wassail for Yule (a celebration of the winter solstice), connecting with something both bigger than and within themselves; there is solace to be found within a group of outcasts.

People fear the unknown, and they’re even more scared to offend a god the Church characterizes as a harsh punisher. In a world where women are still subjected to various forms of oppression, the persecution of witches plays an unfortunate

role. Witch hunts and the propagation of anti-witch ideology fuel patterns of gender-based persecution, justifying the quick accusation of and violence towards women. In the US, there is a growing stigma against non-Christian spirituality, coinciding with the rise in conservatism in recent years.

According to UN Women, nearly one in three women worldwide has experienced physical and/or sexual violence in her lifetime. In 2023 alone, approximately 85,000 women and girls were killed, 51,100 of which by an intimate partner or family member. While few, if any, of these women were accused of witchcraft, the legacy of witch hunts continues to reinforce systems of misogyny and violence against women today.

And yet, women of nature persist. Traditional practices that have withstood witch hunts still exist in Mexico, Italy, Africa, Slavic countries, and many other corners of the world. Modern witchcraft is reaching more people than ever with the influence of social media. They gather, praise something other than a traditional doctrine, and are exuberantly removed from the constraints of the materialistic, patriarchal void that feeds on us all. Why not be a witch?

WHY NOT BE A WITCH?

WRITTEN BY AMELIA FIORE

ART DIRECTOR LELA AKIYAMA

PHOTOGRAPHED BY AUBREY KUNZ

MODELS FIONA RIDER, PARKER KIRKWOOD, SOPHIA SOLEIL & AVA KOOK

GIDI BATYA

FOX

ArtivingL

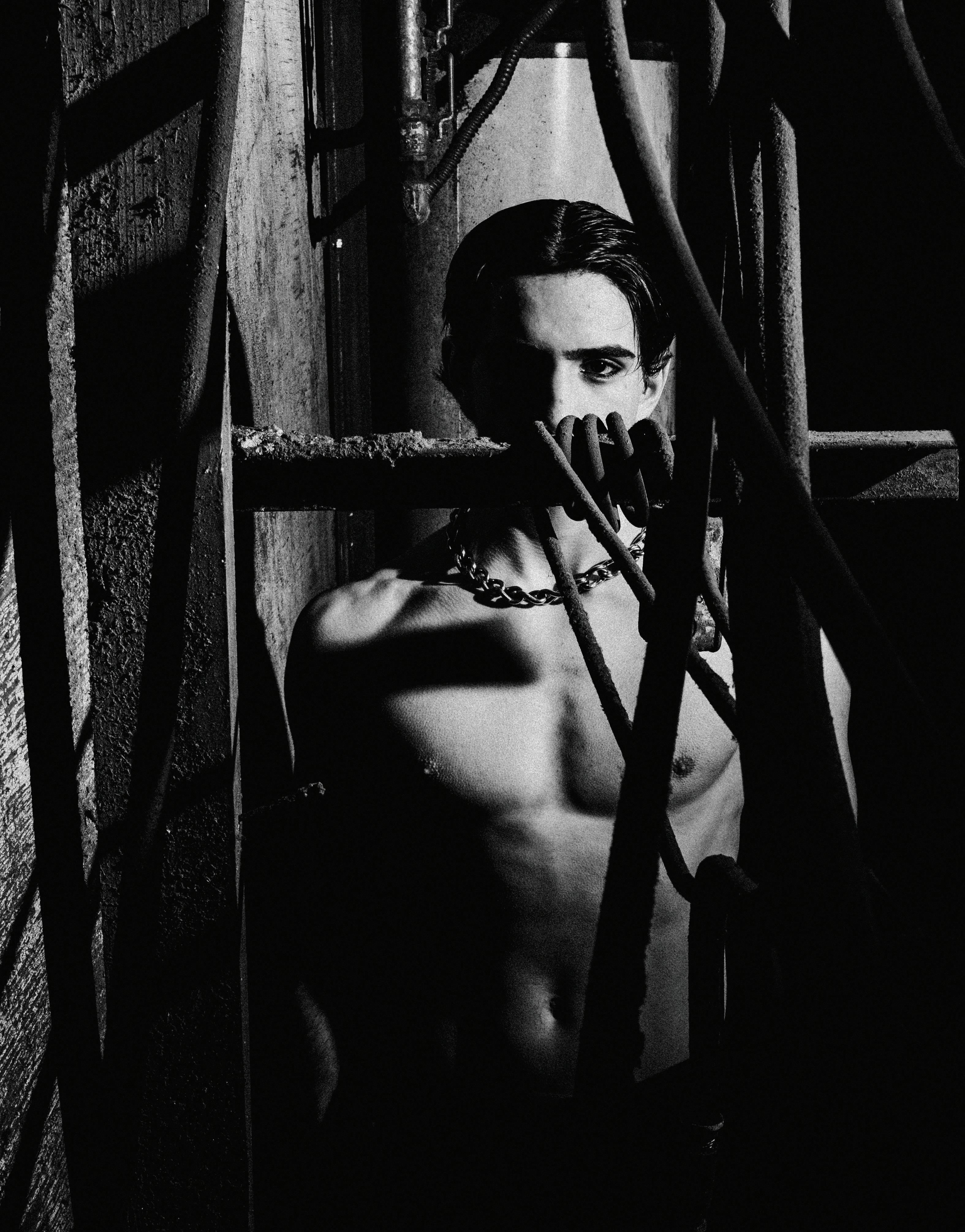

Exploring the Living Art of Marina Abramović and Ulay

Marina sits at the small wooded table at the Museum of Modern Art, waiting for the audience’s electricity to send currents through her work. This is Marina Abramovic’s near 50th piece of performance art. She is determined in her work, with meticulously planned rules for the piece. The rules of this performance are simple: sit silently in a chair and let any audience member sit across from her. She must have complete control of her body and mind to harness the energy it takes to masterfully pull this off. She sits as each stranger takes their turn sitting in her presence. Hours go by, strangers from all different backgrounds enter her unflinching gaze. She closes her eyes between each new passing stranger. Opens them again, has a moment of connection, repeats. She closes her eyes and breathes. She can feel her body pulsating as she harnesses her willpower to be present. A new stranger enters. She opens her eyes – and suddenly, they flood with tears. She breaks her rules for the first time.

“The Artist is Present” was a solo performance done by Marina Abramovic in 2010 at the MoMA. The project spanned three months with an astounding 700 hours of live performance. During this time, Abramovic was fully living in her art, and inviting her audience to do so too.

Abramovic is known as the “grandmother of performance art," and rightly so, as she was one of the founders of performance art when it started gaining traction in the 1970s. Her history with live performance art started in 1973 when she performed her first solo piece; "Rhythm Series," in which she explored themes of bodily limits, identity, ritual, and how art is shaped by audience participation. These performances were considered extreme, often leading Abramovic to pass out during the performances or be severely threatened during them. They were wildly captivating and showed her extreme dedication to her art. During that same period, Uwe Laysiepen (Ulay) was producing his own experimental works, among them were polaroids that depicted the male-female relation and challenged gender norms.

In 1975, the two artists met in Amsterdam, and formed a connection right away, bonding over their shared birthday, shared passion for performance art, and similar central themes present in their work. After deciding to live together, the pair produced collaborative art which grew from their mutual trust and devotion.

WRITTEN BY KIANA HEILFRON

ART DIRECTOR ALEXANDRA BONDURANT

PHOTOGRAPHED BY HANA WITTLEDER

STYLIST ALYSSA SAMUEL

MODELS DREW TURIELLO, STELLA MCSHANE, ABIGAIL GHIO & JACOB MITANI DESIGNER JOEY MATSUNO

They became longtime performing partners and lovers, with works spanning over the course of a decade. Of these works were “Relation in Time” (1977), “Rest Energy” (1980), and “Nightsea Crossing” (1981-1987). “Relation in Time” was one of their major influential works because it expressed their feelings of connection. In this piece, Abramovic and Ulay sat back to back with their hair tied tight together in a ponytail for 16 hours. They physically could not move because of their connected condition, and they performed the last hour live. This highlighted how audience presence can give artists the energy they need to preserve through extreme discomfort. In “Rest Energy," Abramovic held a bow to her chest while Ulay held the arrow pointing at her, while each leaned back. In a “Louisiana Channel” documentary, Abramovic explains that “'Rest Energy' was probably the most dramatic and most dangerous of all of them” due to the unpredictability of getting shot. Abramovic also recalls Ulay’s answer as to why they chose to point the arrow at her instead of Ulay: “because her heart is my heart too."

Unfortunately, after a decade of loving, living, and working together, the pair started to venture their own ways. This split occurred over many years during one of their last performance collections together: “Nightsea Crossing.” During this collection, the pair experimented with human connection through no interactive means. Instead, they simply sat still across from one another for hours on end — battling hunger, sleep, and exhaustion. During the last performance in “Nightsea Crossing," Ulay could no longer take the extreme physical and emotional strain, and had to leave the performance. Amid increasing tension, the two planned their final collaboration, “The Great Wall Walk.”

“The Great Wall Walk” was first an idea they had for their future wedding, however, with their shift in attitudes towards each other, they decided the walk would be a performance to demonstrate their final goodbye. They each walked from one end of the Great Wall of China to meet in the middle and say their goodbyes. Abramovic expressed that it was “the most dramatic goodbye” with both artists crying and hugging when they met for the last time before walking their separate ways.

Back in the MoMA, the lights go dark as Marina closes her eyes in anticipation for her next visitor. It’s 2010, 22 years since her extreme separation from Ulay. She takes a breath and opens her eyes. Sitting across from Marina is none other than her longtime collaborating artist and friend, Ulay. The two are filled with tears as memories of all of their past work comes flooding back. Later on in an interview, Marina reflects on her emotion to seeing Ulay on opening night of her performance. She says to him , “You [were] not just another visitor, you were my life.”

Eve’s Daughters

How Romantasy Reclaims the Power of Female Curiosity and Defiance

Girlhood is a season. First, the sowing, the rules we are told to follow. Then, the ripening, the ache to know and to want. And eventually, the harvest, when we take what feeds us, even when it is not offered.

As literature has evolved, so has the audience that is allowed to claim it. A space once dominated by male authors is now being rewritten by women. Out of this shift has emerged “romantasy,” a genre that blends romance and fantasy.

This genre has given women a space to reclaim power and voice, something long denied in both sacred and secular storytelling. Historically, women have been robbed of a voice in a male-dominated world. This silence is evident in modern storytelling, particularly in the fantasy genre. But unlike the religious Biblical narrative where Eve is condemned, the heroines of romantasy novels rebel against restrictive male-driven narratives. Empowered by rage and injustice, these protagonists rise from the ashes of the forces trying to destroy them.

The strength and power of choice shown originally by Eve reappears in characters such as Aelin Galathynius from Sarah J. Maas’s “Throne of Glass” series. Aelin begins as a broken assassin, missing, enslaved and surviving in a world full of enemies until she reclaims her destiny as Queen of Terrasen.

Throughout the saga, Aelin loses cherished allies and endures torture. But she continues to fight for herself throughout the 4,642 pages of the series. She builds from her wounds and emerges from her suffering. As Adrianna King writes in Halftone Magazine, “Romantasy doesn’t skirt past hurt and pain; it takes that pain and turns it into growth and strength.”

Aelin’s rise gives female readers hope for a world in which they can endure, survive, and claim power too. Her rebellion against the male-dominated forces in the fictional realm proves that power and ambition are forces to lean into. As Megan Scott writes in CultureFly, “Romantasy gives women the possibility of being powerful … in a way that’s not threatening like it is in real life.”

Even the oldest myth of female disobedience, the Garden of Eden, is being reread through this same lens. “A closer reading suggests that the transgression itself may reflect a reclaiming of knowledge, agency and the violation of patriarchal injunctions,” said Jacob Ford, the research communications coordinator for the College of Pharmacy and Allied Health Professions, who examined reinterpretations of the Eden story in a South Dakota State University study.

Since the Bible, Eve has been framed as a weak-minded and naïve woman who is responsible for sin in the world. But what if she was not the villain — what if she was the first person to demand knowledge in a society that tried to keep it out of reach?

In a study of the book of Genesis, Bates College researcher Sarah Herde argues that Eve’s choice was rooted in agency rather than weakness, “eating the apple provides Eve with the knowledge needed to ensure she is not overconsumed by Adam even beyond the space of Eden.”

Herde argues that Eve consumed the forbidden apple not out of malice or manipulation — as traditionally framed by patriarchal Christian teachings — but in pursuit of knowledge. In a study of male-dominated interpretation in

Christianity, Maeve Pioli, an honors graduate student at the University of South Carolina, wrote, “for centuries, the traditional Christian understanding has relied heavily on the patriarchal biases of historic church figures to enforce a gendered hierarchy where women are deprived of authority, voice and agency.”

Today’s heroines follow in those footsteps, stepping into their own power.

As a reader of both the Bible and romantasy since elementary school, I grew up alongside Eve and Aelin. Every woman first sows the seeds of who she could become. Every woman ripens beneath the weight of a world that was never designed for us. And eventually, every woman harvests the knowledge and power we were never meant to claim. Being a young woman is not a downfall — it is a becoming.

What Eve began, the heroines of romantasy continue. They invite readers to ripen with them, to hunger for more, and to rise stronger for having asked. Eve didn’t fall — she grew too powerful to stay in the garden. The first sin wasn’t hunger, it was calling ambition a sin.

WRITTEN BY CECI CRONIN

ILLUSTRATED BY MARYCLAIRE LANE

DESIGNER BRYANT LEAVER

PLAYLIST CONNOISSEUR FIONA RYAN

WRITTEN BY AMANDA

ILLUSTRATED BY RUBY

LAN ANH

KNOTT

DESIGNER NATALIE KOSKI

PLAYLIST CONNOISSEUR MORÉA MANSON

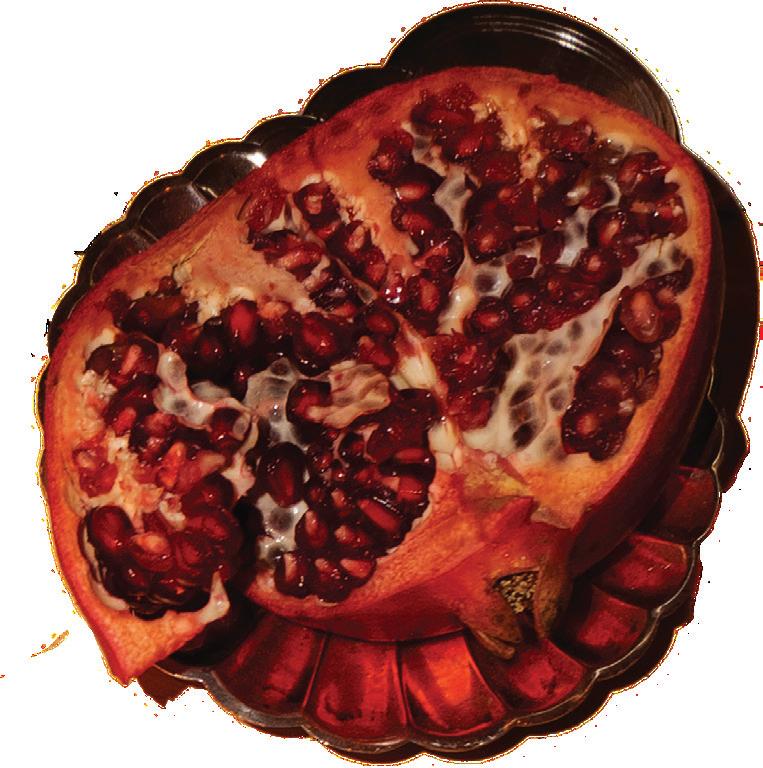

Six Seeds

A hunger made holy and an appetite as myth

Every harvest lies. It says it is about fullness, about fields bowed under their own generosity. But beneath the ripest orchard is want — sharp, skeletal want. Desire is the root system no one draws on the map. It twists beneath the soil, drinking darkness, splitting stone.

Persephone ate six seeds. The world calls it her undoing, as if appetite were shameful, as if hunger were not the first truth every creature learns.

But what if hunger itself was the point? Not the fruit. The wanting. The mouth saying more in a language that no mother or husband could translate.

They name it captivity. I name it metamorphosis. You cannot chew a fruit so red, so stubbornly alive, and still pretend you are untouched.

This is fruition’s trick — what looks like bloom is often endurance given a new costume. They say she returns each spring. What they don’t say: she returns with the taste still pulsing against her tongue, with a throat lined in pomegranate, with a body that knows it can live underground and still flower.

Hunger is not the opposite of survival. Hunger is the engine of it.

There are many versions of the descent. In some, a cleft opens and swallows her; in others, a hand does the swallowing. The details rearrange themselves like reeds in a current, and still the current pulls down. Name it kidnapping, marriage, migration, metamorphosis; the earth does not annotate. What matters is that below is a country, and a threshold is a kind of hunger: a mouth in the ground, a mouth in the self. You can be carried across or step across; either way, you are across.

Above ground, a mother unthreads the world. Grain shrivels under her grief; oxen sleep in their yokes; ovens grow cold. What mothers know: fruit hangs from a broken branch anyway. Loss makes a weather of its own. She bargains with sky, with soil, with gods who count by eras while she counts by heartbeats. The famine answers in the only language it has. Everything stops until the story listens.

The earth opens and does not apologize. Descent, in myth, is always narrated in a passive voice — as if to strip the subject of agency, as if gravity alone explains a girl’s hunger. But language is never neutral, and neither is silence. To say “she was taken” is to deny the possibility that she looked at the pit yawning below and said, “yes.” Said, “let it be me.” Said, “I am already half-gone.”

And what of the mother? The one who watches the girl vanish and makes a drought of her grief. What of the hands that held ripeness as covenant, only to find the tree bare in morning? Demeter curses the world not out of rage, but out of recognition. She knows what it costs to ripen. She knows the fruit doesn’t ask permission from the branch. She knows, better than anyone, that all harvests are laced with absence.

This is the part we forget when we praise the bloom: something dies for every sweetness we taste. Every full field is a monument to what fed it: the rot, the ruin, the rain that wouldn’t stop. And still, we name it abundance.

Fruition is not about ripening. It is about what the world demands in exchange for fruit. It is about how much of yourself must be buried so that something beautiful can grow from your remains.

Gods are not made. They’re made of.

Of want, of worship, of whatever burns loud enough to echo. No one chooses to become a god. It happens when the story gets too big to be held in the throat of a single girl. It happens when the hunger becomes holy — when everyone starts to call your longing a prophecy, and your ache a miracle. Persephone was not made into a goddess; she was made of thresholds, of the dirt she bled into, of six red seeds that refused to digest.

This is what fruition really means: not culmination, but construction. Not reward, but raw material. You are not full, you are filled, and there is a difference. The girl they mourned bloomed into a country. Into seasons. Into law. Her body became a boundary between life and something else. Every spring she emerges not as a daughter reclaimed, but as a deity who knows the cost of returning.

Public Art For Who?

Today, when the market value of artworks exceeds millions, you’re just as likely to find a da Vinci painting hanging above a Saudi prince’s toilet as you would on a museum wall. In response, most would agree emancipating art from the grip of billionaires and speculative capital should be the art world’s foremost concern. Perhaps this is why public art — artwork made for and belonging to public spaces — holds such mass appeal. Public art refutes private ownership and mandates art be made accessible to the community. At least, such is the contention.

At the same time, if we were to joke that publicly-funded art is but a bureaucratized art, this wouldn’t be far from the reality. However, it’d be equally unreasonable to expect art today to be wholly free from its institutional constraints. This is why it remains important to emphasize the role of public art as an agent of discourse despite such restrictions.

Shouldn’t we start by asking the age-old question: “What is art good for?” To answer this would be impossible, because no matter what, you implicate yourself in your response. What is art good for? In the end, it’s only good for what you deem it to be good for.

namely a vehicle for thought and dialogue.

But what’s the role of the public space in all this? What is public space even for? This last question has baffled sociologists and art critics alike, but for our purposes what makes a space “public” has little to do with property rights and more to do with its use by people: the mode of being “public” exists insofar as it constitutes open discussion. The oldest examples of such spaces, the Roman forum and Greek agora, have become synonymous with politics because they provided the conditions for people to gather. The public space exists anywhere that invites discourse: a city square, a park, a plaza, or even a classroom. Public art, therefore, should reflect the discursive impulse of the public sphere.

Still, let’s say this: since the advent of Modernism in the early 20th century, art ceased to be merely concerned with representation or ornament. This switch was informed by a conceptual turn toward avant-garde radicalism, which reestablished art as a social practice and critique of institutions (think Dadaism). A residual avant-garde radicalism still subsists in the cultural imagination of what art ought to be,

In 1975, Oregon passed the “Oregon Percent for the Arts” legislation, mandating 1 percent of the construction budget for state building projects be used for the commission of artwork. This type of “Percent for Art” scheme, first adopted by Finland in the early 1930s, has subsequently spread throughout Europe and the United States since. Yet the process for commissioning art under this program has become dubiously longwinded: to finalize proposal submissions to selection committees an artist must first endure multiple rounds of voting, then filings and re-filings of budget estimates, negotiations with sponsors, and finally approval from an appropriate council board.

This top-down strategy too often prevents the realization of a project’s full potential. Ultimately, it’s the commissioning

agency, not the artist, who gets the final say about an artwork. Such a process extinguishes the possibility for the production of a discursive, potent work of art by carefully wrapping it in administrative red tape.

Needless to say, while there exist conceptual limitations to public art projects, having infrastructure that supports the direct public subsidization of artists is 100 percent necessary. In the United States, federal funding for the arts is largely administered through the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), an agency that was founded in the mid-1960s. The NEA provides grants to state and regional arts agencies, allowing for programs like “Oregon Percent for the Arts” to continue. As of 2025, however, under an administration that threatens the permanent termination of the agency, the outlook for the future of arts funding in the United States appears bleak. But why does it matter that the NEA is bound to a precarious fate?

When visiting a museum, we can’t avoid having rarified encounters with art: paintings appear as if belonging to a realm outside everyday life. But in the public space, this veil is lifted and we’re able to come across the same artwork on our own terms, without the pretensions of the gallery. People have a purer interaction with art in the public sphere.

Funding cuts and reduced access guarantee art occupies a privileged realm. It’s clearer than ever the commodification of art into a luxury good degrades its value to the public. Neoliberal market deregulation and the gross privatization of everything under the sun have only cemented art as a bonafide financial product. The market value of artworks goes up when income inequality increases, as art prices are propped up by the capital streams of the ultra-wealthy. Within capitalism, art inevitably assumes an inherently anti-democratic, profit-driven function.

Clearly, the exaggeration of art’s economic value has smothered its discursive potential. Even so, we must resist the temptation to give up on imagining a better future for public art in the face of this. Sure, while this future may not realistically realize a system where art is divorced from capital, it could still achieve an equitable distribution of capital toward revitalizing social programs. Ultimately, we should start asking ourselves the exact question we feared to be unanswerable — “what is art good for?” and more importantly, for who?

WRITTEN BY EMESE

BRACAMONTES VARGA

ART DIRECTOR LUCY MCMAHON

PHOTOGRAPHED BY CARTER GARRETT

MODEL ISABELLA KING

STYLIST FRANCESCA OVERTON

DESIGNER NATALIE ENGLET

Threads that Remember

FASHION AS CULTURAL PRESERVATION AND RESISTANCE

Until the lion has a historian, the hunter will always remain the hero. An antiquated yet relevant Nigerian proverb used to describe stories untold, expunged from the archives by huntsmen of the past. While established Western fashion houses continue to churn out the remnants of their colonial past, a new generation of designers has begun to weave together threads of southern heritage with modern tastes. From runways in Paris to the streets of Eugene, these unapologetic creatives refuse to be silenced, crafting the culture of the future.

African fashion in particular has been profoundly disrupted once trade routes, missionaries, and colonizers imposed European ideas that encouraged modesty as an equation to “civilization.” However, developed textile industries in Mali and Nigeria had sophisticated textile industries recorded as early as the 13th century, despite colonial connotations that Africans had “no fashion.” In the 15th century, missionaries enforced dress codes that criminalized Indigenous clothing. Despite reshaping, the cultural significance of the textiles remained through garments and wrappers that acted as stylish forms of resistance.

Aurora James, creative director, fashion designer, and founder of Brother Vellies, has built her life’s work to use stitching as storytelling. Her mother was an avid fashion collector – from Danish clogs to cowboy boots from Texas to kimonos from Japan. At an early age, James learned that what we wear should not just be a reflection of taste, but of one’s values. As James moved through the world, she became acutely aware of how colonialism had attempted to sever fashion from its origins. She preserves African craftsmanship through leatherwork, weaving, and shoemaking traditions that colonialism attempted to erase.

With Brother Vielles, James has reimagined the Vellie, a traditional African shoe, into a practical staple that can be seen walking the streets of Manhattan. She aims to reframe the role hands of color plays in luxury fashion. The shoes are made in Africa as she changes the connotations of “made in Africa” to reflect opulence rather than charity and pity. In James’ memoir, “Wildflower,” she says, “Luxury to me meant more than interlocking letters forming a prestigious logo – It meant everyone in the supply chain getting paid fairly and being treated with respect.” James ensures that artisans behind each pair of shoes are recognized as luxury makers, not charity cases. That community is reflected in the product.

Across the sea, Nicholas Daley, a London menswear designer and fellow fashion trailblazer, uses clothing to trace his own lineage. Born to Jamaican and Scottish parents, Daley’s work is a textile conversation between two histories. For his Autumn/ Winter 2023 collection, Daley reinvented the Scottish tartan while also incorporating elements inspired by his Jamaican roots. While crafting the collection, he collaborated with British craftswomen whose techniques are vanishing. He released his “Slygo” collection that honors his father’s reggae club nights while serenading guests with live reggae music at his fashion shows and a Jutepois collection that honors Dundee’s female jute mill workers. Daley shows that heritage isn’t static. It can be remixed, reworked, reimagined.

These explorations of lineage and craft are not exclusive. 2021’s CFDA fashion fund winners, Rebecca Henry and Akua Shabaka from House of Aama, contribute to reshaping fashion’s purpose as they show fashion as mythology and ritual. Drawing on African diaspora folklore, Louisiana Creole histories, spiritual traditions, and early jazz culture, juxtaposing such elements with modern Hollywood. They emphasize the importance of hands-on creation in their design process and an act of intimacy and resistance in an era of detachment.

Intimacy and craftsmanship needn’t only take place on the runways of Paris or the streets of Bushwick. It’s in our neighborhood. In Eugene, the Walugembe family at Swahili African Modern partners with Ugandan women artisans whose weaving and carving traditions stretch back generations. Their clothing is not only beautiful, but it is also economic empowerment, cultural continuity, and a tangible connection to African heritage.

With threats to erase DEI and the passing of former creative director of Louis Vuitton, Virgil Abloh, the fashion industry may be in danger of swimming in the sea of sameness. But worry not, true revolution is underway. High fashion brands like House of Aama, Nicholas Daley, and Brother Veilles all create a blueprint for a future where fashion and heritage are mutually sustaining.

Textiles have become testimonies; patterns have become maps. Each bead, stitch, and hem is an artifact of those who have lived, created, and resisted.

The future of fashion will not only come from the seasonal cycles of Paris, New York, or Milan. They will come from the hands of weaving women in Uganda, from designers remixing ancestral lineages, and creatives who refuse to be erased. With clothing, the lion can become the protagonist.

WRITTEN BY ANAYA LAMY

ILLUSTRAITED BY WALLIE BUTLER

DESIGNER ELLA KENAN

PLAYLIST CONNOISSEUR MIA FAIRCHILD

We learn early in our lives how to fit in, to play roles, to perfect ourselves for unseen audiences. Most times, we don’t know who these audiences are, yet we censor our curiosity to make ourselves more palatable to them; our parents, our friends, our community, even strangers.

Our entire lives we are taught to perform. We learn to adhere to social norms and sanctify stereotypes and trends. Yet, it’s in our adolescence that we begin to question who we are doing this for. In that moment, we subconsciously decide who our audience should be.

I am not a huge party person, but I am a lover of a good kickback with a fire. When we gather around, I always want to ask: what makes you, you? Maybe you don’t have a five-year plan, and that’s okay. I just want to meet you, the individual, rather than the lifelong performer.

At the end of the day we have our status, our follower count, and our jobs. But, I want to know what lights your fire? Do you know what the shape of your soul looks like?

If not, you’re not alone. For years, I looked for myself in other people constantly. I spent so long trying to perfect the aesthetic of myself others wanted to see. Even the smallest things — a color — became part of that performance, sage green or cowboy copper becoming a mark of attendance in the in-crowd. But over time, through droughts of summer and long, quiet winter breaks, I started tending to my own soil. That’s where I found the truest friendship, within myself.

I never had a sibling to bother when I was bored as a child. I don’t know what it’s like to share the spotlight with my parents. I’m constantly told I’m lucky to be an only child, but it was hard to find out who I am without someone to compare myself to.

Yet, I somehow do.

Sometimes I dance without music just to feel the rhythm move through my hips. I sing out loudly on my walk home — maybe badly — but without a care. And in those small acts of freedom, I feel the pulse of who I am.

This relationship with myself has become my saving grace in every hardship. I’ve learned I’m not perfect. But I am grateful that I have the stamina to reflect and to try again.

The real growth and being that I crave comes from the pauses between acts, from moments of vulnerability rather than exhibition. I want to make my own happy endings from within, rather than from external validation. Get to know the shape of my soul, even the parts that scare me.

I used to hate pink. I wanted to be more than just a girl who liked the color pink. I wanted to change the world. So, I protested pink. To show my defiance, I punished my vulnerability. For years, I would act disgusted at the sight of pink.

Then, in high school, I took a psychology class. I learned that pink signifies love, calmness, innocence, and well-being.

As a child, I was scared of all of these feelings. Afraid that my innocence and well-being would derail my shot at greatness. Petrified that my calmness would be seen as weakness. Nervous that love would supersede my dreams.

A couple years later, the summer before my freshman year of college, my mom wanted me to make a theme for my dorm. Without even thinking, I said, “What about pink, Mama?”

At that moment, I met the little girl within me who once despised pink and whispered, “Softness doesn’t make us fragile; it is the seedbed of our becoming. We are worth investing in, even as we change along the way”

Safe to say, my dorm was filled with the color pink. Surprisingly, it brought me calmness and reminded me of the love I needed to excel in my freshman year as the first woman on my mom’s side of the family to go to college.

That’s the beauty of self-discovery and being alone.

Embracing pink wasn’t just about a color, it was about reclaiming the parts of myself I didn’t know existed. I pruned my fears to allow for more growth. Maybe no one noticed this change, but I did.

Now, pink is one of my favorite colors.

I once believed my aesthetic defined my soul, so I poisoned the parts of myself I deemed out of line – and I can’t say I regret it. Every calamity that once derailed me has fertilized the soil of who I am today.

Yes, it was hard, but in the process I got to meet myself. Maybe my evolution will go unnoticed by the world, but I feel it blooming quietly within me, and that is enough.

We crave the fruit, but forget to tend to the soil. We forget that the fertile nature of the soil determines the fruit, not the height of the tree. And the only way to cultivate your soil is to understand your roots.

Like the ripening of your first fruit, the self emerges through stillness rather than spectacle. Don’t show off your first fruit. Taste it. Savor what you’ve grown and who you’ve become, all for yourself. Enrich your mind, body and soul in your passions. Learn what makes you come alive. Life will always bring storms and seasons of drought, but through self-discovery you’ll find the deepest truth: You already have everything you need to grow, to thrive, and to bear fruit, again and again.

MONSTER HOUSE

On April 9, 2025, the studentrun music venue Monster House played its final show. Settled on the busy corner of East 18th Avenue and Hilyard Street, the venue, nicknamed for its resemblance to the titular house in the 2006 movie, had played host to local bands and roaring crowds for two years. The hosts were expecting a massive crowd, but commented that even they were surprised by the 800-person turnout.

The line wrapped around the block. Vendors set up shop outside, waving down potential customers as people shoved cash into the little briefcase popped open under a canopy.

In the yard, the crowd swayed from side to side almost as one, entranced by a beat that rocked the stage, blurry under a haze of smoke. Some people got on each other’s shoulders, others fought through the barrage of bodies to get to the front.

“We might have to start denying people,” Kameron English, Monster House resident and host, commented. “It’s so packed in here already.”

It was only 8 p.m.

The closure of Monster House, run by and for University of Oregon students, was inevitable. Graduations and careers were on the horizon, while the bustling backyard and crumpledup beer cans faded into memory.

April 2023 - April 2025

THE LOCAL VENUE THAT CREATED COMMUNITITY SPACE IN EUGENE

Over its lifetime, Monster House accomplished a feat few local house venues could: cheap shows, spectacular lineups, massive crowds, and little trouble from local law enforcement.

In fall 2023, English, along with Jett Hulen and Logan Taylor, began renting the house on East 18th. By the spring, their friends noted how much space there was in the backyard. Local indie band Bowl Peace thought it would be perfect for a show.

“We wouldn’t have been able to do any of this without the band’s help. They knew how to set it up, where to put the stage, they had a lot of insight for us before we knew anything about it,” Taylor said.

English cobbled together a stage. “I’m always scratching my head, thinking, ‘What if someone falls through?’” he joked, adding, “Nobody ever has. That thing is like a rock.”

The first show, on April 9, 2023, kicked off on unsure footing; busy spring midterms and an unknown name meant a sparse turnout. The second show, a week later, was the same. There were maybe 100 people in attendance both nights — a number that would be trumped repeatedly in the coming years.

English, Hulen, and Taylor charged a $7 fee to cover operating costs. They bought string lights, installed a Port-APotty in the far right corner of the yard, set up a merch station by the shed for bands to sell T-shirts and CDs. It was a small way for the talent to make a little revenue — soon, though, as crowds erupted, Monster House offered to start paying them for gigs.

“90 percent of the money I’ve made in music has been from Monster House,” said Eli Filnore, lead singer of local rock band and Monster House regulars, Cosplay Jesus. “We got paid $1,000 on our first show. Local DIY bands don’t get paid $1,000, ever.”