Cormorants

"Lethal Control"

Cormorant Culling

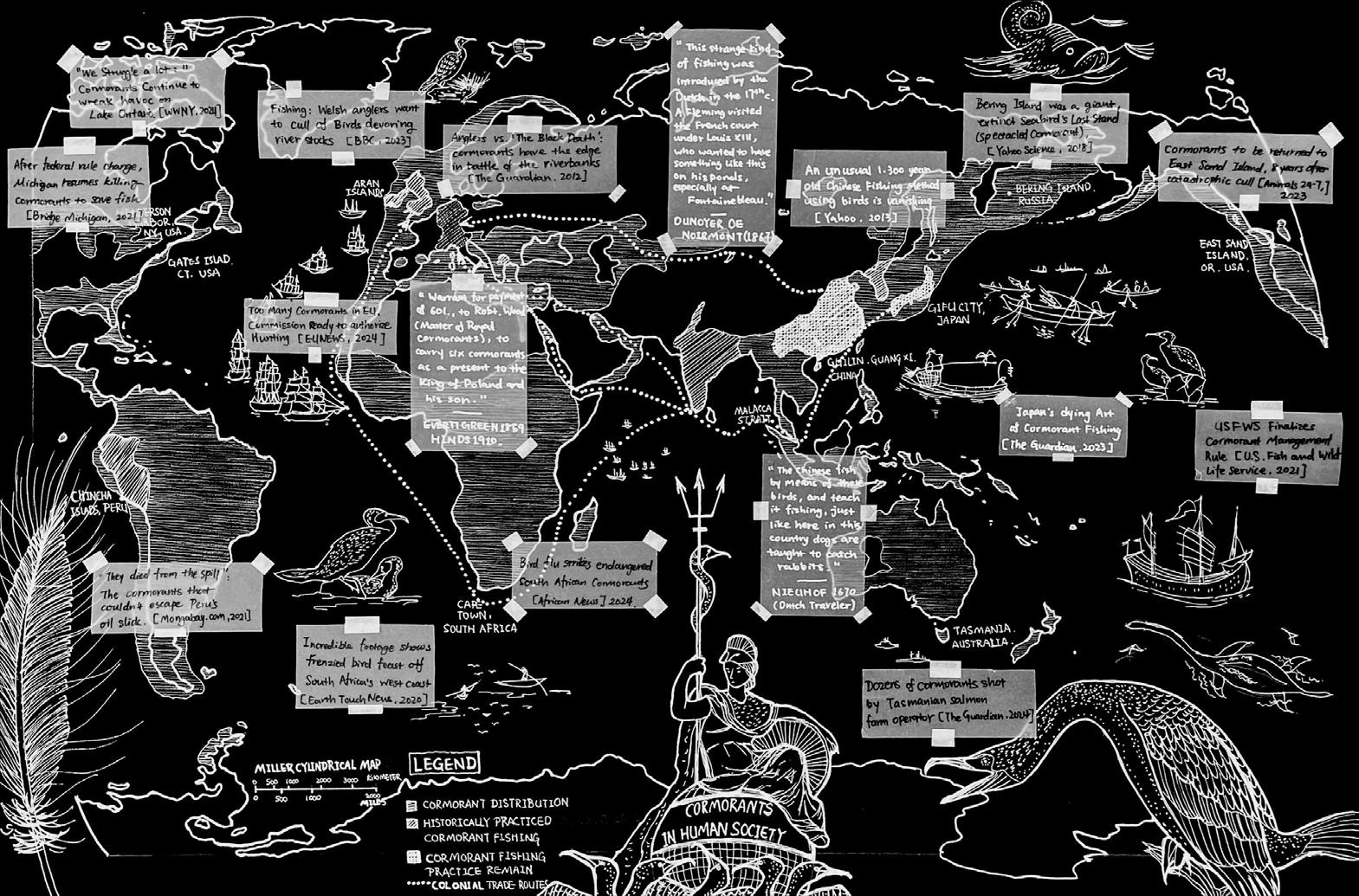

Cormorant culling has occurred primarily in Europe, North America, and parts of East Asia, where growing cormorant populations have impacted fisheries, aquaculture, and local ecosystems.

Up to 2014, about a half-million cormorants had been killed under the orders of Fish and Wildlife Service in US alone. The FWS determined it could issue individual permits to kill up to 51,571 cormorants a year at fish farms without a significant impact on the bird’s population.

In 2013, Japan’s cormorant population, was estimated at over 100,000 birds. The growth has intensified conflicts with the ayu, or sweetfish, a species crucial to Japan’s commercial and recreational fishing industries, prompting government-led culling efforts. In Japan alone, between 10,000 and 25,000 cormorants were culled annually from 2004 to 2012.

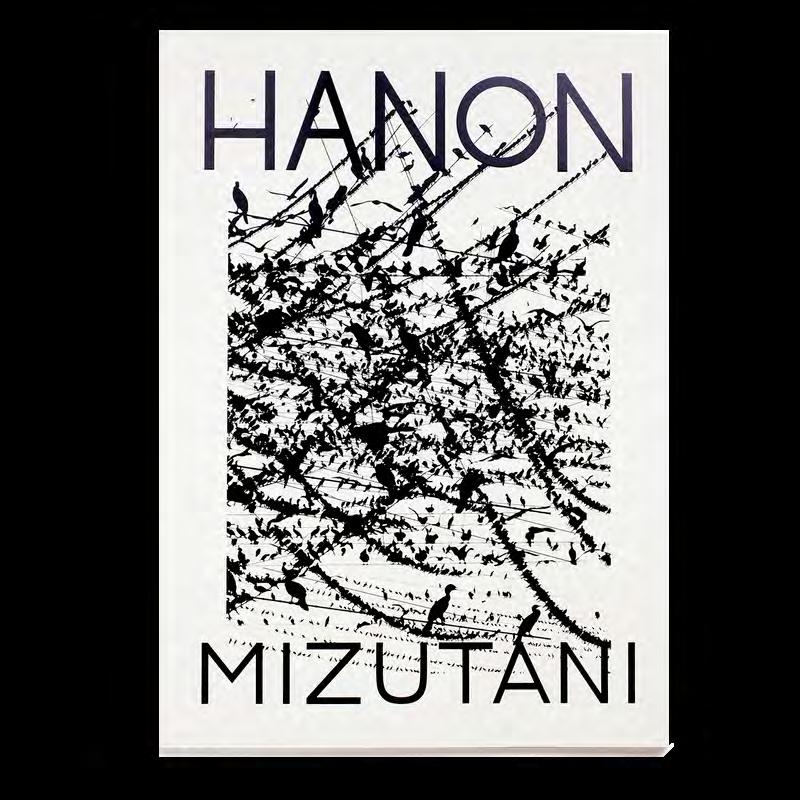

Photobook by Yoshinori Mizutani, HANON (2016) wild cormorants in the city of Tokyo, Japan

The soaring population of cormorants in Japan filled the skies and waterways with their sleek forms. The local residents of cities like Gifu and Tokyo begins to see them as a "nuisance".

The soaring population of cormorants in Japan filled the skies and waterways with their sleek forms. The local residents of cities like Gifu and Tokyo begins to see them as a "nuisance".

In the rise of cormorant culling, a practice of hunting and killing for sports and pleasure disguised in the name of sustainability, we wonder:

In the rise of cormorant culling, a practice of hunting and killing for sports and pleasure disguised in the name of sustainability, we wonder:

Have humans forgotten the remembrance of cormorants?

Have humans forgotten the remembrance of cormorants?

鵜 (Umiu)

Cormorant

The Great Cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo) and Japanese Cormorant (Phalacrocorax capillatus) are large, black seabirds known for its distinctive long neck and hooked bill, which it uses for fishing. These birds are native to Japan, are often seen diving in rivers and coastal waters, hunting for fish in colonies.

Both species of cormorants in Japan are mostly year-round residents, some colonies partially migrates a short distance to northern regions during spring to early summer for breeding. Populations in warmer regions are usually sedentary.

Cormorants typically nest in colonies, building nests made of sticks and vegetation in trees or on rocky cliffs, where they engage in communal breeding and care for their young.

Great cormorant. Illustration from John James Audubon's 'Birds of America', original double elephant folio (1834-35)

A scientific illustration of an adult Japanese Cormorant from Fauna Japonica, 1842. Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866)

Within the quiet shelter of a cormorant's nest, an egg rests, round and pale, holding a new life within its shell. The parents' dark form hovers over it as life grows inside the egg.

Within the quiet shelter of a cormorant's nest, an egg rests, round and pale, holding a new life within its shell. The parents' dark form hovers over it as life grows inside the egg.

The days pass, and the faintest light begins to filter through the shell. Inside, the chick instinctively pushes against its confines, pecking until the first crack appears, a sliver of light and air seeping into its world.

The days pass, the faintest light begins to filter through the shell. Inside, the chick instinctively pushes against its confines, pecking until the first crack appears, a sliver of light air seeping into its world.

At last, the young cormorant emerges, small and damp under the sun. They cannot see much yet, but the chick can feel the warmth and presence of their parent’s body, their calls and vibrations, guiding the chick towards food.

At last, the young cormorant emerges, small and damp under the sun. They cannot see much yet, the chick can feel the warmth and presence of their parent’s body, their calls and vibrations, guiding the chick towards food.

The tether, as the earliest instrument of animal domestication, allowed humans to control and restrict animal movement, marking the first step in taming and enabling the management of livestock.

In cormorant domestication, the tether allowed humans to control these birds' movement and use the bird to fish.

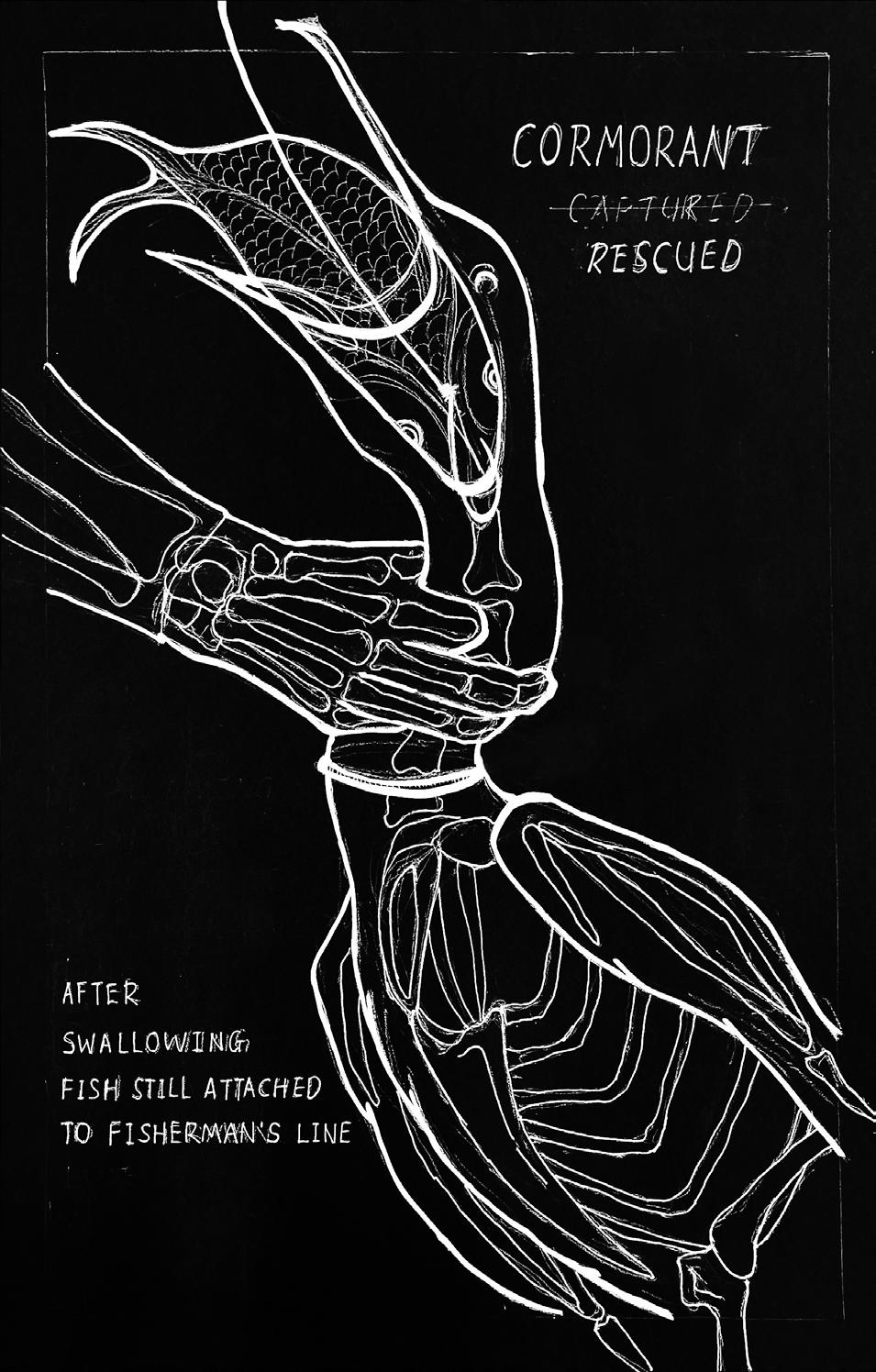

Cormorants are captured as they rest during their short distance southward migration. The Japanese fishermen would sometimes clip the tip of the bird's beak and a few feather from one wing. The fishermen use cormorants that are caught during the process and acclimated them to humans. 鵜縄 (U-nawa)

a "snare" or "tether": The rope used to control cormorants in cormorant fishing

In the case of cormorant domestication, this tether became a link between bird and fisherman, an invisible line binding wild instinct to human intention.

In the case of cormorant domestication, this tether became a link between bird and fisherman, an invisible line binding wild instinct to human intention.

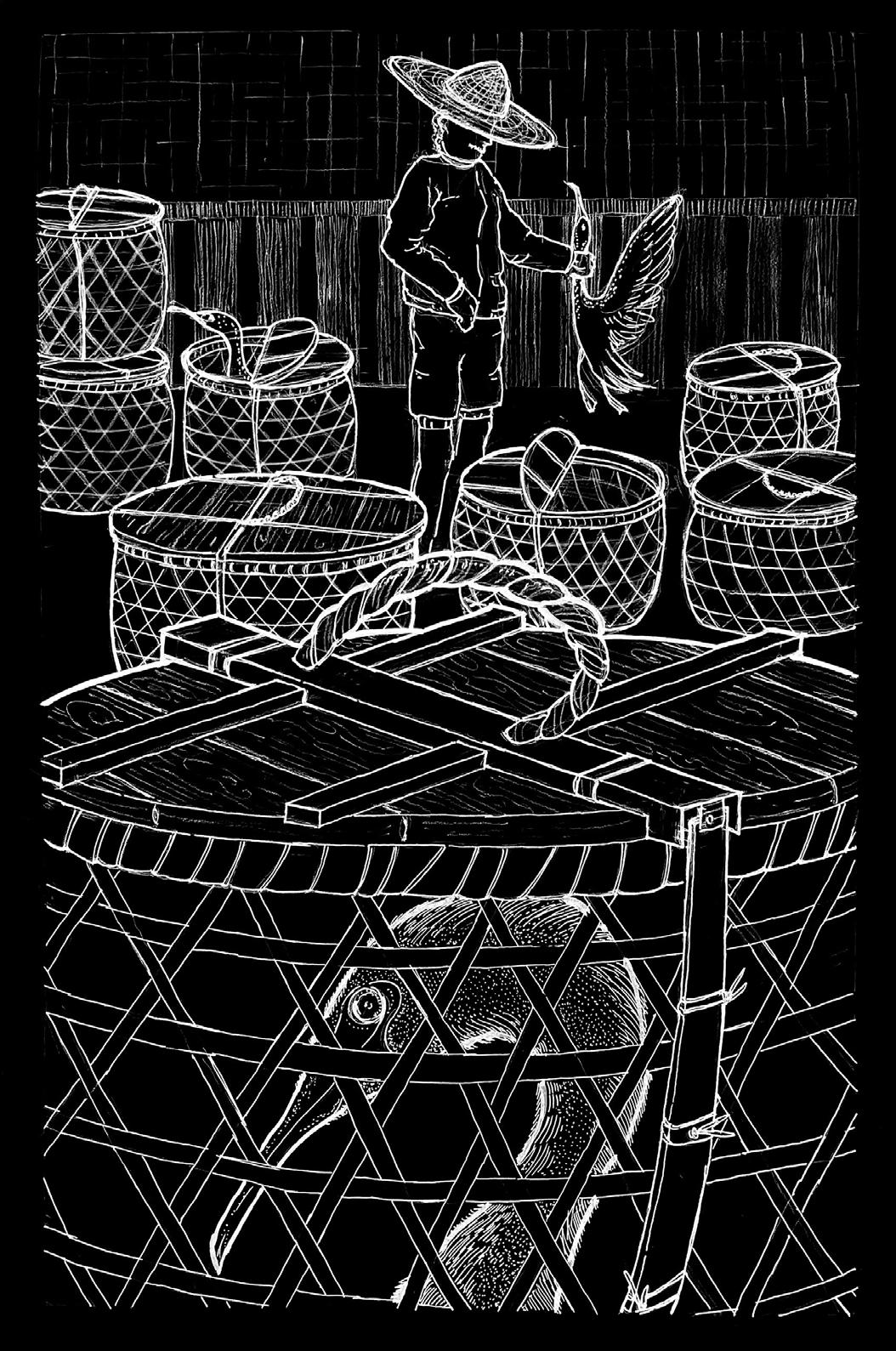

When not out on the water, the cormorants are housed in coops. As the fishing hour approaches, the fishermen place the birds into bamboo-woven baskets, carrying them to the river’s edge. These baskets, crafted through tradition, serve as temporary vessels that the cormorants associate with the rhythms of their life along the river.

When out on the water, the cormorants are housed in coops. As the fishing hour approaches, the fishermen place the birds into bamboo-woven baskets, carrying them to the river’s edge. These baskets, crafted through tradition, serve as temporary vessels that the cormorants associate with the rhythms of their life along the river.

This ritual of partnership transforms the cormorants into both allies and instruments, their freedom held in balance by a cord that links them to the hands of those they fish alongside.

This ritual of partnership transforms the cormorants into both allies and instruments, their freedom held in balance by a cord that links them to the hands of those they fish alongside.

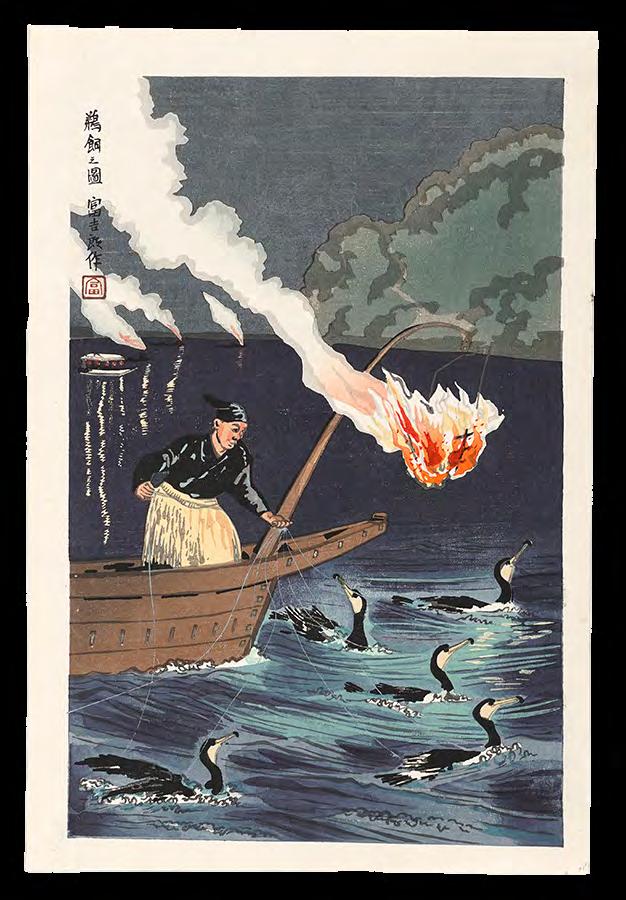

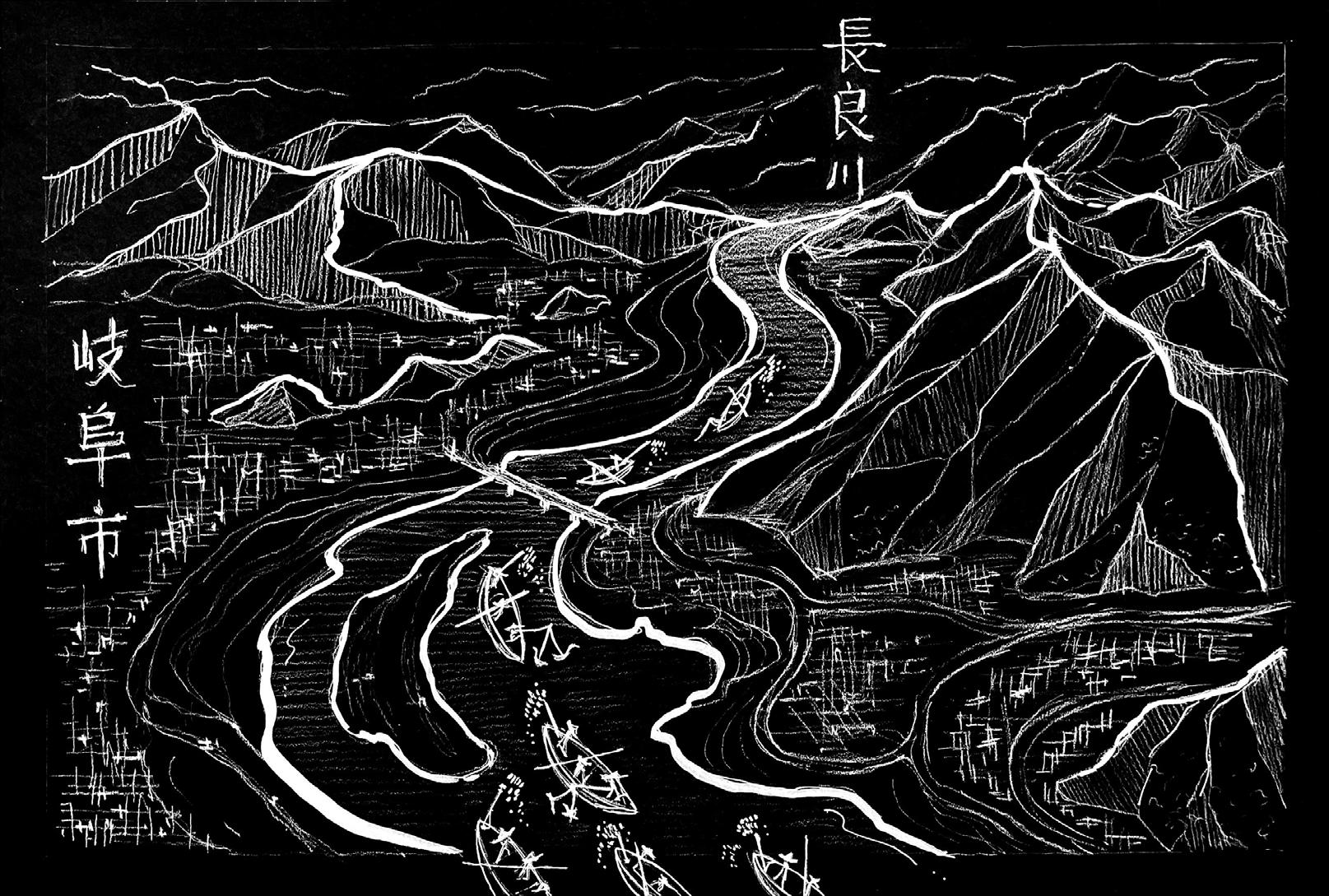

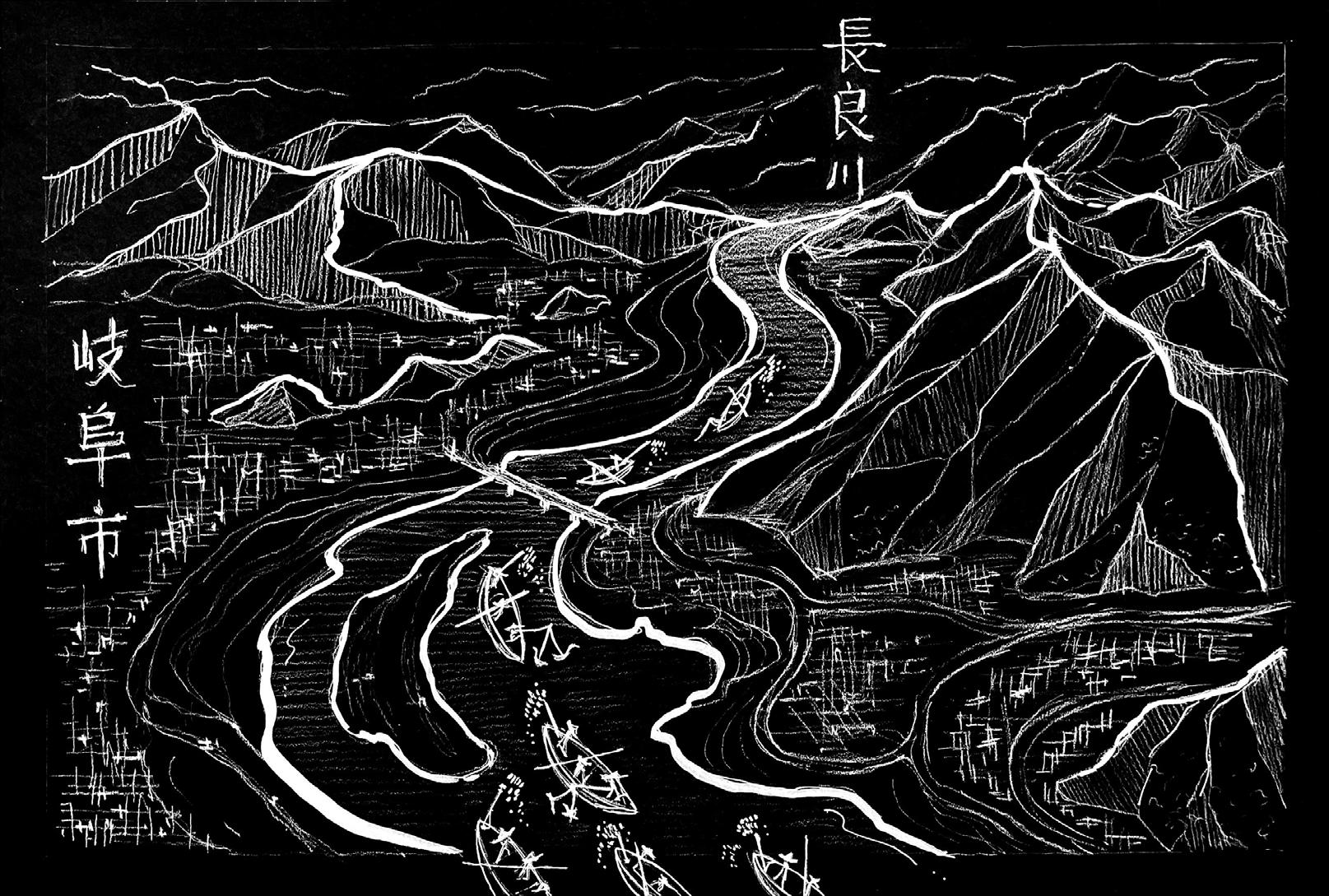

鵜飼 (U-kai)

Cormorant Fishing

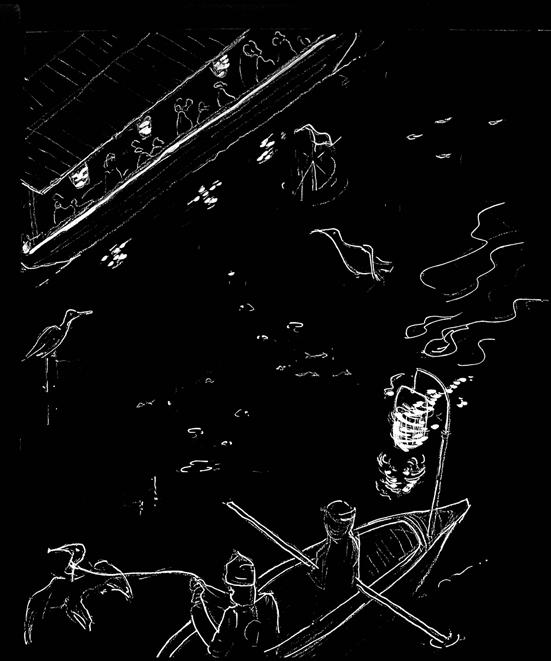

Cormorant fishing on Gifu’s Nagara River has 1,300 year history. It is a technique that involves releasing a cormorant, bound by a snare connecting its neck to a boat floating downstream with the current.

The bird catches fish as they are startled out from underneath rocks at the river’s bottom by the fire on the boat’s bow.

The cormorant is unable to swallow the fish because of the snare tied around its neck.

The fisherman then reels the bird in and makes it cough up the fish stuck in its throat.

The cormorants were trained before they could fish for humans. The newly caught birds are considered to be too vicious and are kept tied up, while brought to the river daily to practice catching and disgorging fish under leash.

The cormorants were trained before they could fish for humans. The newly caught birds are considered to be too vicious are kept tied up, while brought to the river daily to practice catching and disgorging fish under leash.

Perhaps the complex apparatus set by the fishers were unconsciously a response to the fear that these captured birds might escape. Therefore, he must control and puppeteers the birds' every move. The tethers provides absolute and instantaneous control, while the burning fire illuminates the nightly scene. For the cormorants, the river becomes a stage where their nature is overshadowed by human design.

Perhaps the complex apparatus set by the fishers were unconsciously a response to the fear that these captured birds might escape. Therefore, he must control and puppeteers the birds' every move. The tethers provides absolute and instantaneous control, while the burning fire illuminates the nightly scene. For the cormorants, the river becomes a stage where their nature is overshadowed by human design.

世界(Sekai) World

"Cormorants of more than forty species range along the hundred thousand leagues of Earth's shore-line, well distributed... they constitute the mightiest race of fishers ever known... The piscatorial peculations of men are as a dot beside their unceasing pillage."

Depiction of cormorant fishing practice fist appeared in Europe during the early 1600s,and historians believed these early depictions of the practice encouraged the European aristocrats to take up the practice, with the rising colonialism and fascination in the Orient.

A young Frenchman holds a trained cormorant, named Tobie, in a similar fashion to a falcon.

The frontpiece to La Pêche au Cormoran by Le Couteulx De Canteleu (1870).

Found across the globe, cormorants are both admired and despised. In Japan and China, traditional cormorant fishing is romanticized, especially by Western audiences who view it as an exotic relic of the past.

Found across the globe, cormorants are both admired and despised. In Japan and China, traditional cormorant fishing is romanticized, especially by Western audiences who view it as an exotic relic of the past.

Yet, beyond this idealized lens, cormorants are often vilified by fisheries and anglers who see them as relentless competitors, leading to legalized culling in many regions.

Yet, beyond this idealized lens, cormorants are often vilified by fisheries and anglers see them as relentless competitors, leading to legalized culling in many regions.

The human world thus created a hypocrisy: a fascination with tradition coexists with the willingness to eradicate these birds when they challenge human control over nature.

The human world thus created a hypocrisy: a fascination with tradition coexists with the willingness to eradicate these birds when they challenge human control over nature.

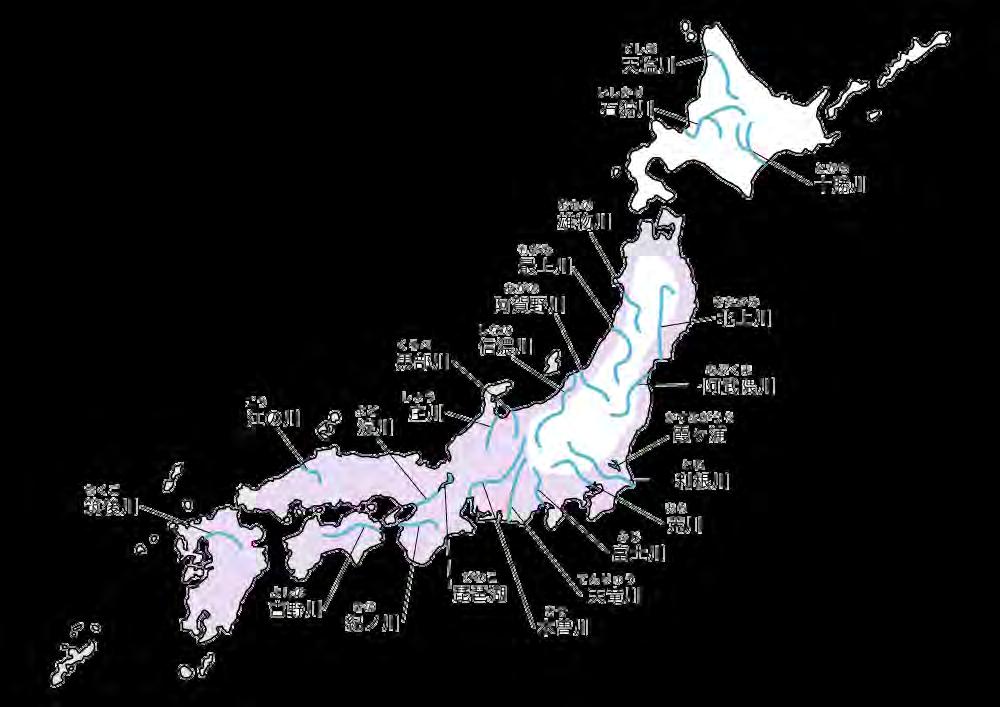

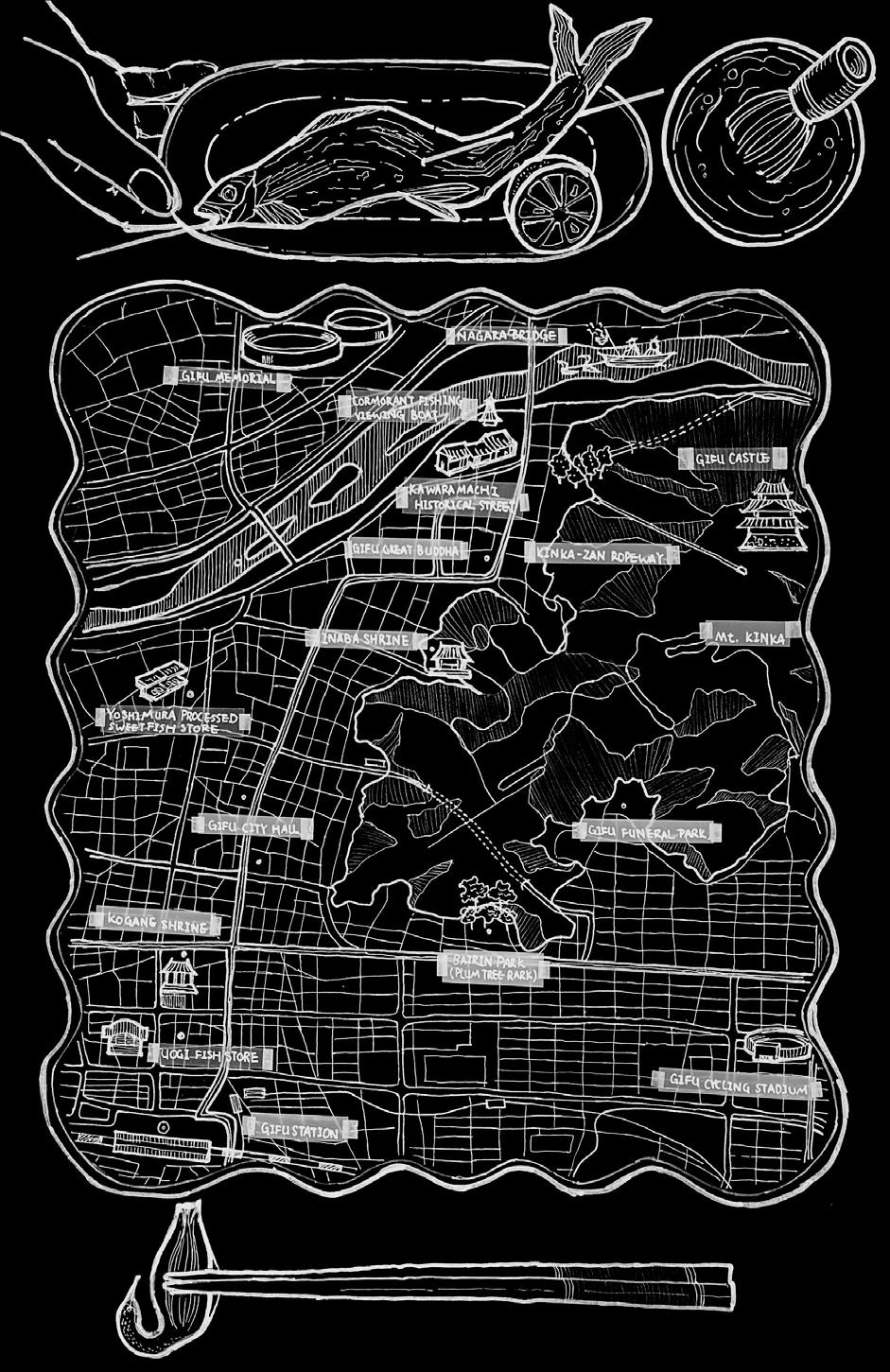

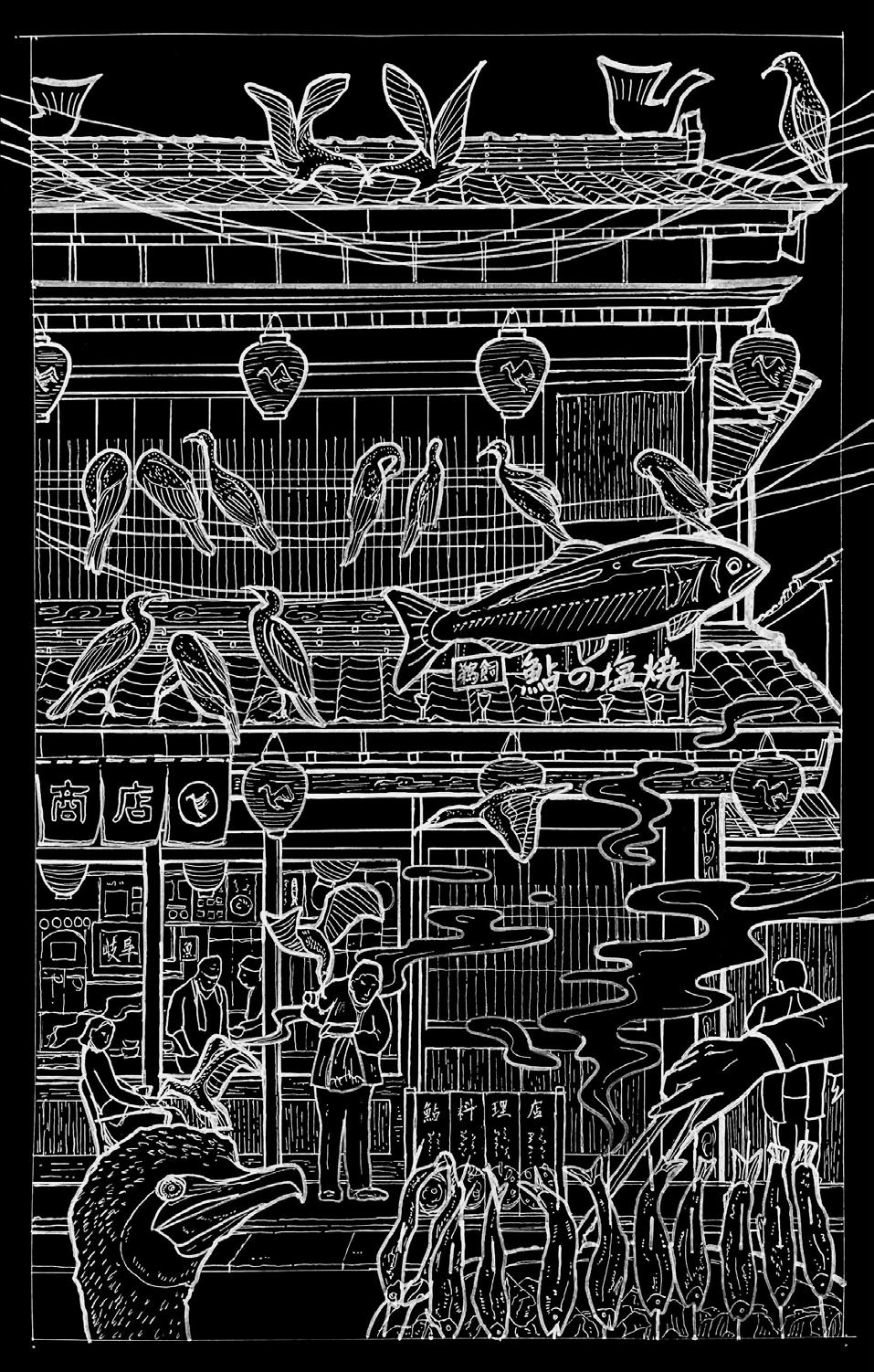

岐阜市 (Gifu) City of Gifu, Japan

Gifu City, nestled along Japan’s Nagara River, is renowned for its cormorant fishing tradition. The wild and domesticated cormorants coexists and play a vital role in the fishing culture.

During fishing season, the cormorant master (usho) controls the birds dive into the river, capturing sweetfish (ayu), a prized local delicacy.

With the rise of industrial fishing, cormorant fishing in Gifu is now mainly practiced as a performance for cultural preservation and tourism.

cormorant presence (year-around)

City of Gifu

Japan's ancient cormorant fishing practice is deeply woven into Gifu city's cultural identity.

Japan's ancient cormorant fishing practice is deeply woven into Gifu city's cultural identity.

The cormorant masters of the city uphold this tradition and their skills over generations, but with the rise of industrial fishing, the practice now faces the challenge of maintaining its relevance. As it has shifted from a vital livelihood to a performance for tourists.

The cormorant masters of the city uphold this tradition and their skills over generations, but with the rise of industrial fishing, the practice now faces the challenge of maintaining its relevance. As it has shifted from a vital livelihood to a performance for tourists.

Meanwhile, the local wild cormorant population is under pressure from fisheries, environmental shifts, and habitat loss, creating a tension with the desire to preserve the traditional practice of cormorant fishing.

Meanwhile, the local wild cormorant population is under pressure from fisheries, environmental shifts, and habitat loss, creating a tension with the desire to preserve the traditional practice of cormorant fishing.

アユ, 鮎, 年魚, 香魚 (ayu)

sweetfish (Plecoglossus altivelis)

The ayu, or Japanese sweetfish, native to Japan, was highly valued during the medieval period, even subject to its own form of taxation. It is considered one of the most popular freshwater food fish in Japan.

When cormorants catch sweetfish, they leave distinctive scratches on the fish's sides with their beaks. These marks indicate that the fish was caught by a cormorant, making it more valuable.

In earlier times, cormorant fishermen in Gifu were able to catch enough sweetfish to sell at the local fish market. However, overfishing and habitat loss have greatly diminished their numbers.

Beak marks evident on sweetfish caught by cormorants.

A cormorant glided effortlessly over the shimmering water, its sharp eyes scanning for the slightest ripple that hinted at a sweetfish below. With a swift dive, it pierced the surface, propelling itself into the depths, where instinct guided its movements toward prey.

A cormorant glided effortlessly over the shimmering water, its sharp eyes scanning for the slightest ripple that hinted at a sweetfish below. With a swift dive, it pierced the surface, propelling itself into the depths, where instinct guided its movements toward prey.

After a successful catch, the cormorant perched on a sunlit rock, stretching its wings wide to dry, the warm sunlight helping to prepare for the next plunge into the depths.

After a successful catch, the cormorant perched on a sunlit rock, stretching its wings wide to dry, the warm sunlight helping to prepare for the next plunge into the depths.

友釣 (Tomozuri)

Ayu Fishing

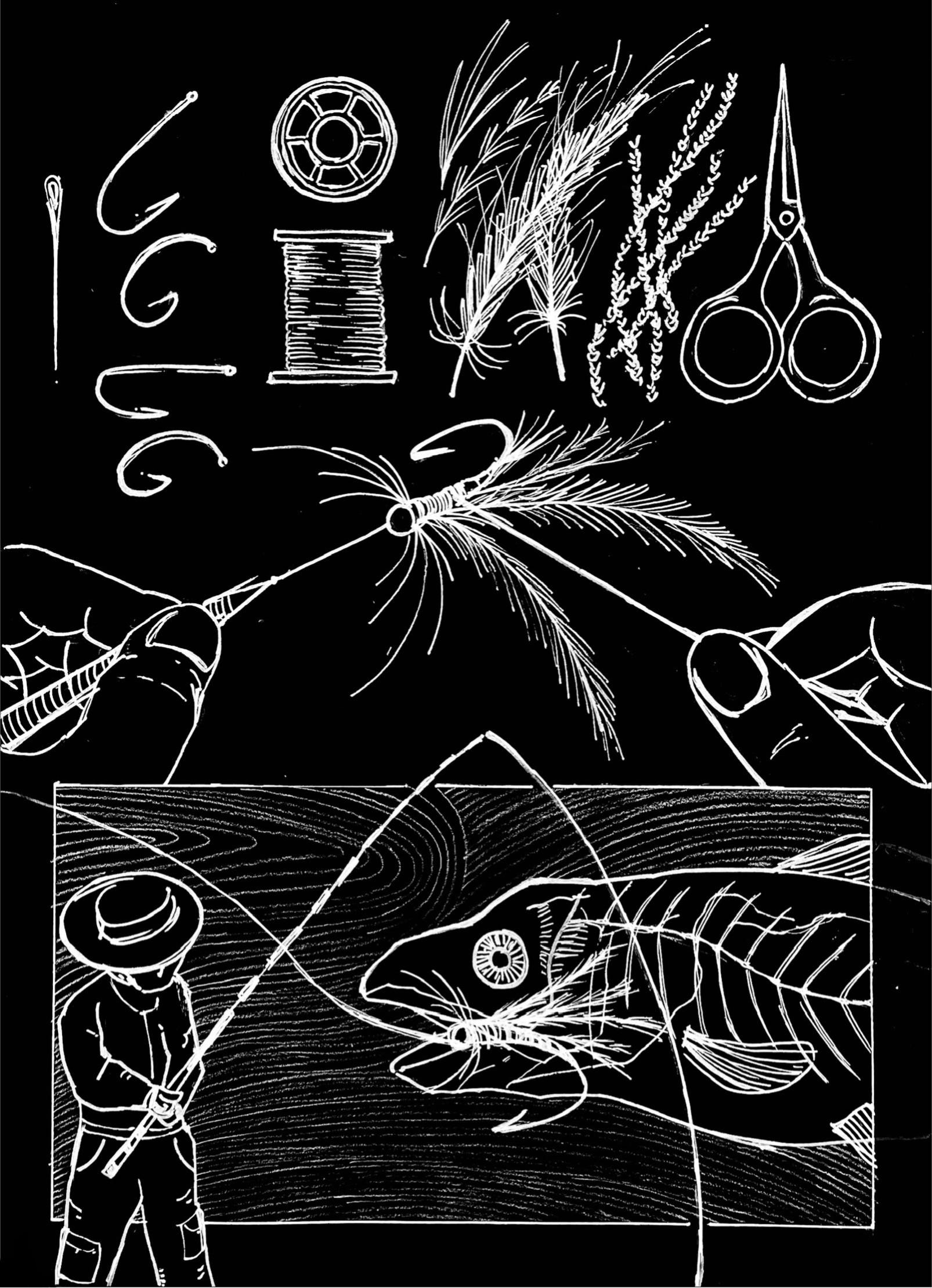

Ayu fishing, which originated with its origins tied to early anglers who discovered the technique of dressing artificial flies with pieces of fabric to attract fish.

Samurai, prohibited from martial arts during the Edo period, adopted this practice as a substitute for training, using the rod as a sword and stream walking for balance and leg strength.

The method can also involve lures or live decoys, as adult Ayu fish are territorial and likely to attack the decoy. This technique, known as Tomozuri or "friend fishing".

Portraits of the samurai anglers under the Tokugawa reign

"Only the samurai were permitted to fish. So, the samurai who enjoyed ayu fishing would take sewing needles and bend them themselves, and make their own flies by hand."

"Only the samurai were permitted to fish. So, the samurai who enjoyed ayu fishing would take sewing needles and bend them themselves, and make their own flies by hand."

By bending everyday materials—such as sewing needles, silk threads, and feathers—into intricate imitations, the fishermen make each fly from natural materials like fur, feather, plant fibers, or silk.

By bending everyday materials—such as sewing needles, silk threads, and feathers—into intricate imitations, the fishermen make each fly from natural materials like fur, feather, plant fibers, or silk.

Through their craft, the object mimics the fluttering insect or the ripples of the stream, blurring the line between reality and artifice. This process is more than imitation; it is an act of decoying, a reflection to the fish's instincts, where the angler adapts nature's secrets through material and movement, in which the mundane is transformed into something both practical and deeply symbolic.

Through their craft, the object mimics the fluttering insect or the ripples of the stream, blurring the line between reality and artifice. This process is more than imitation; it is an act of decoying, a reflection to the fish's instincts, where the angler adapts nature's secrets through material and movement, in which the mundane is transformed into something both practical and deeply symbolic.

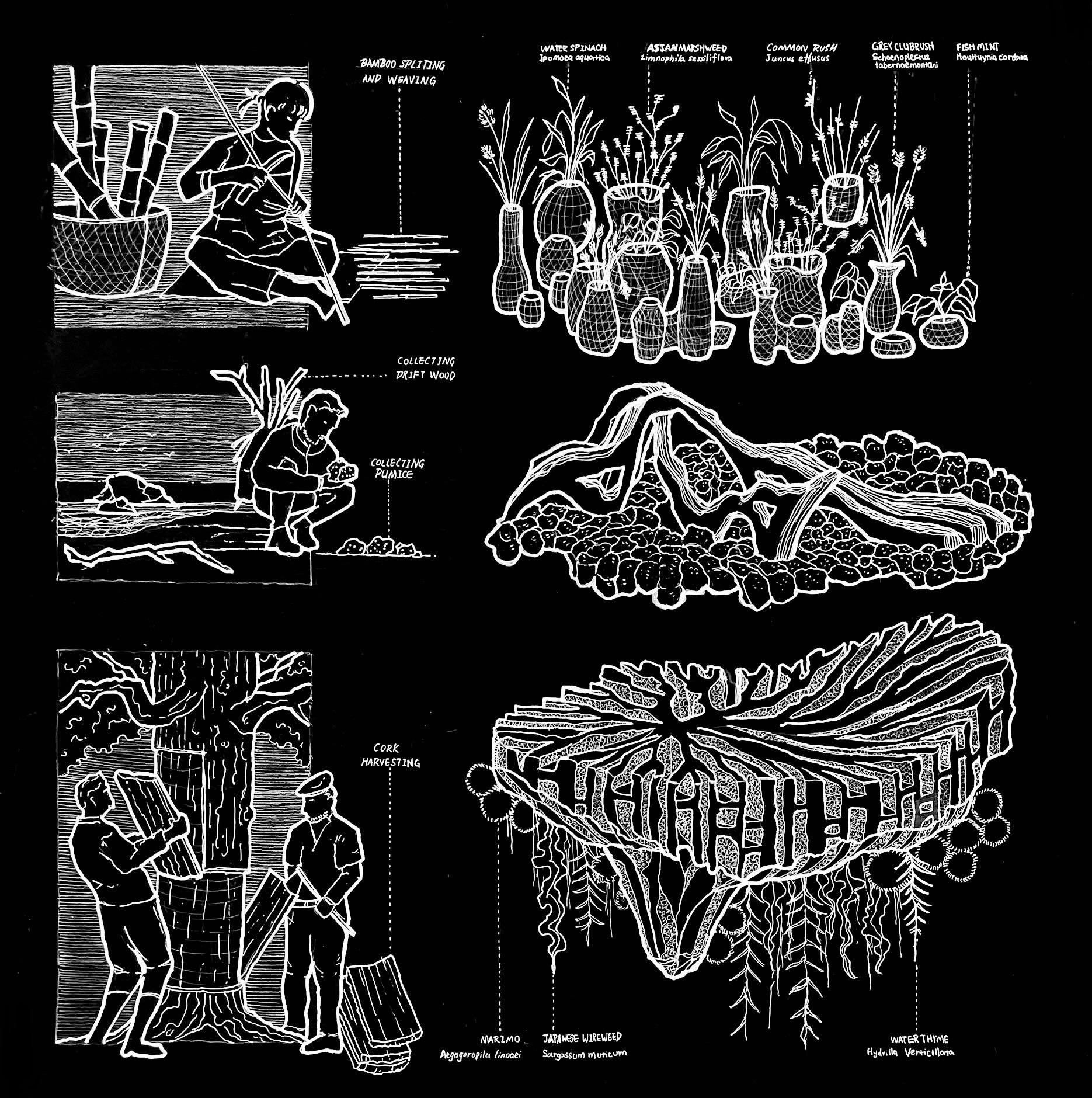

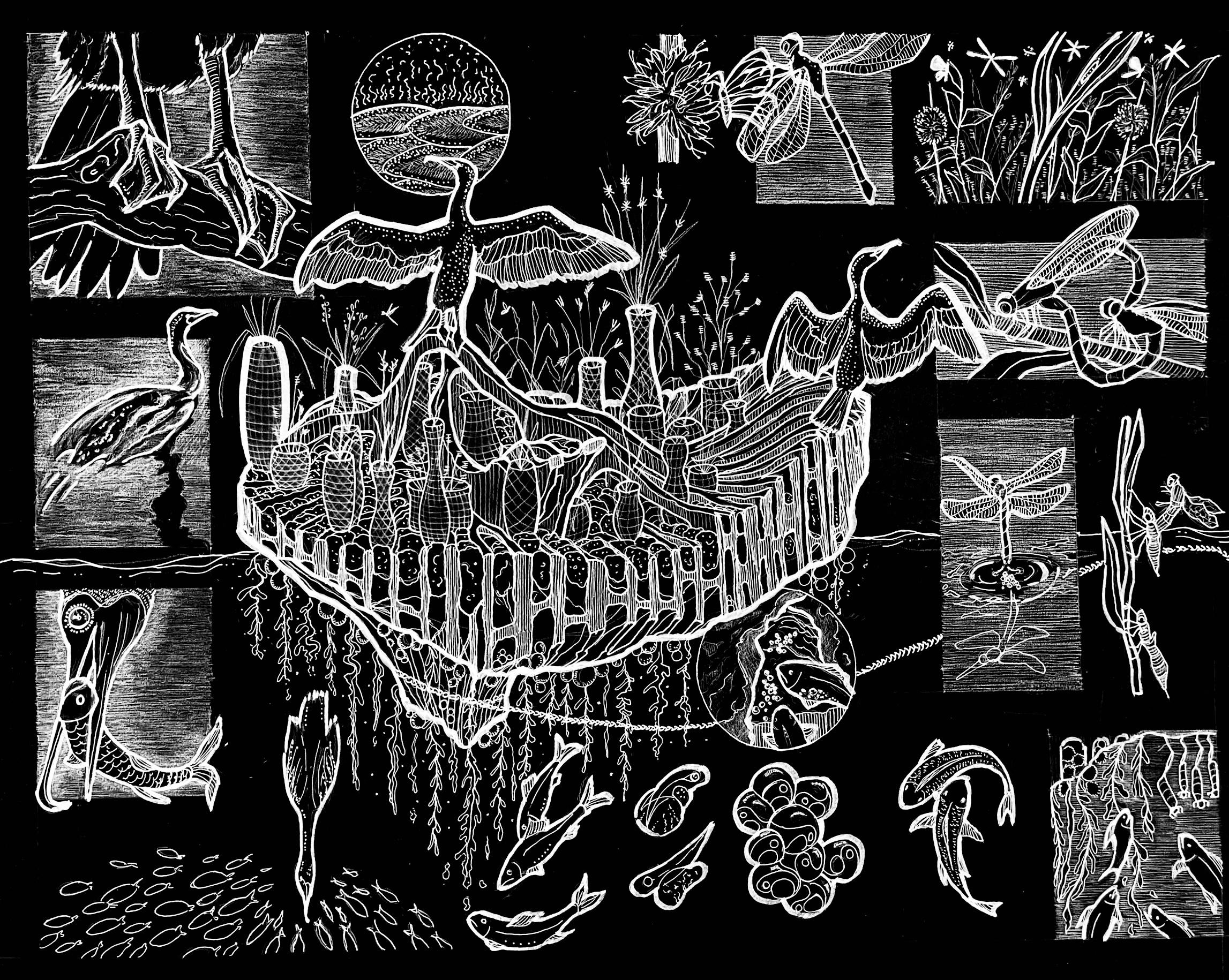

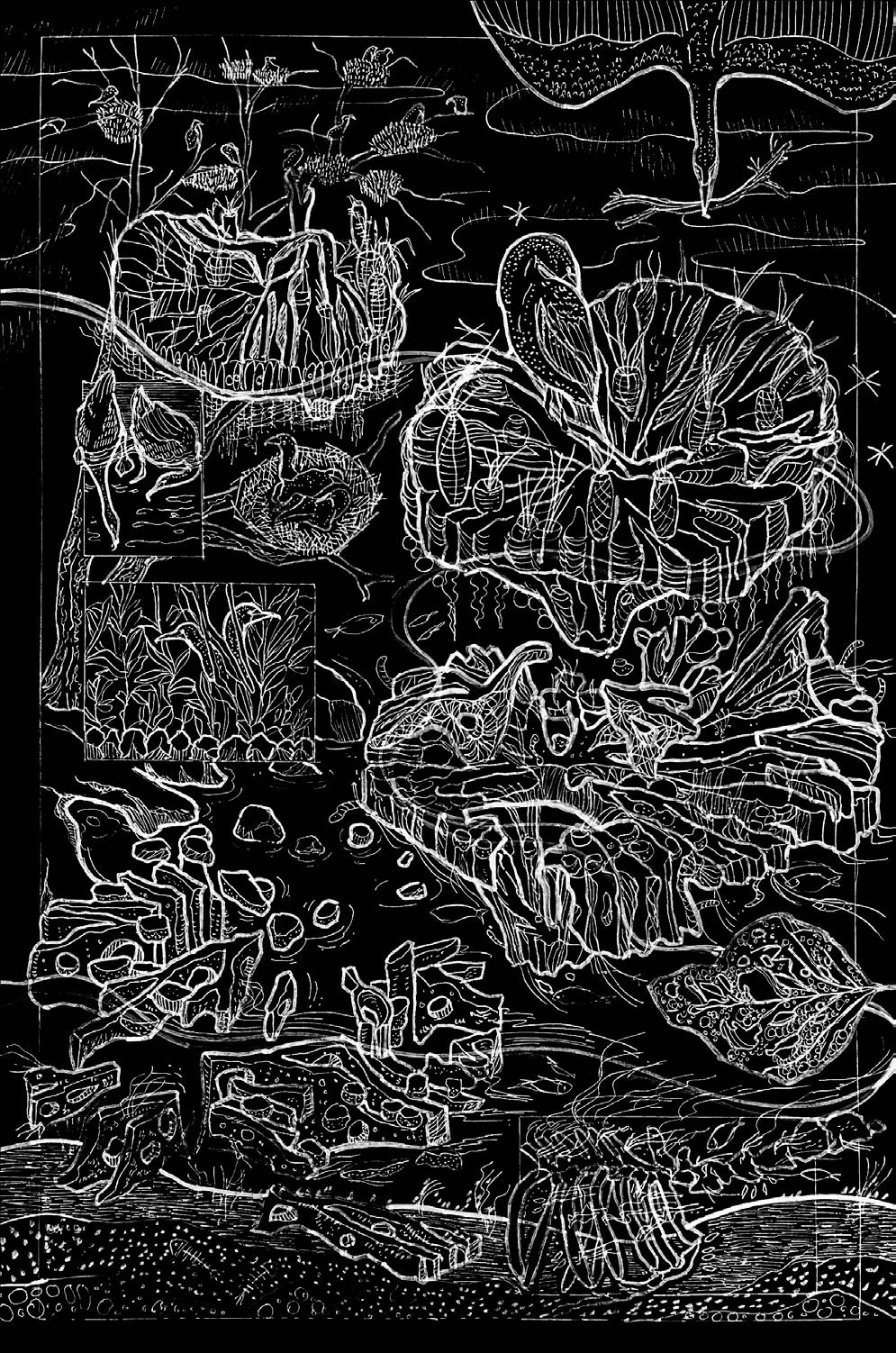

This floating island embodies the food chain’s harmony, offering perches for cormorants and nurturing vegetation and algae for Ayu (Japanese sweetfish) and other species.

It forms a cradle to be released into the Nagara River, balancing spaces for both birds and fish to flourish.

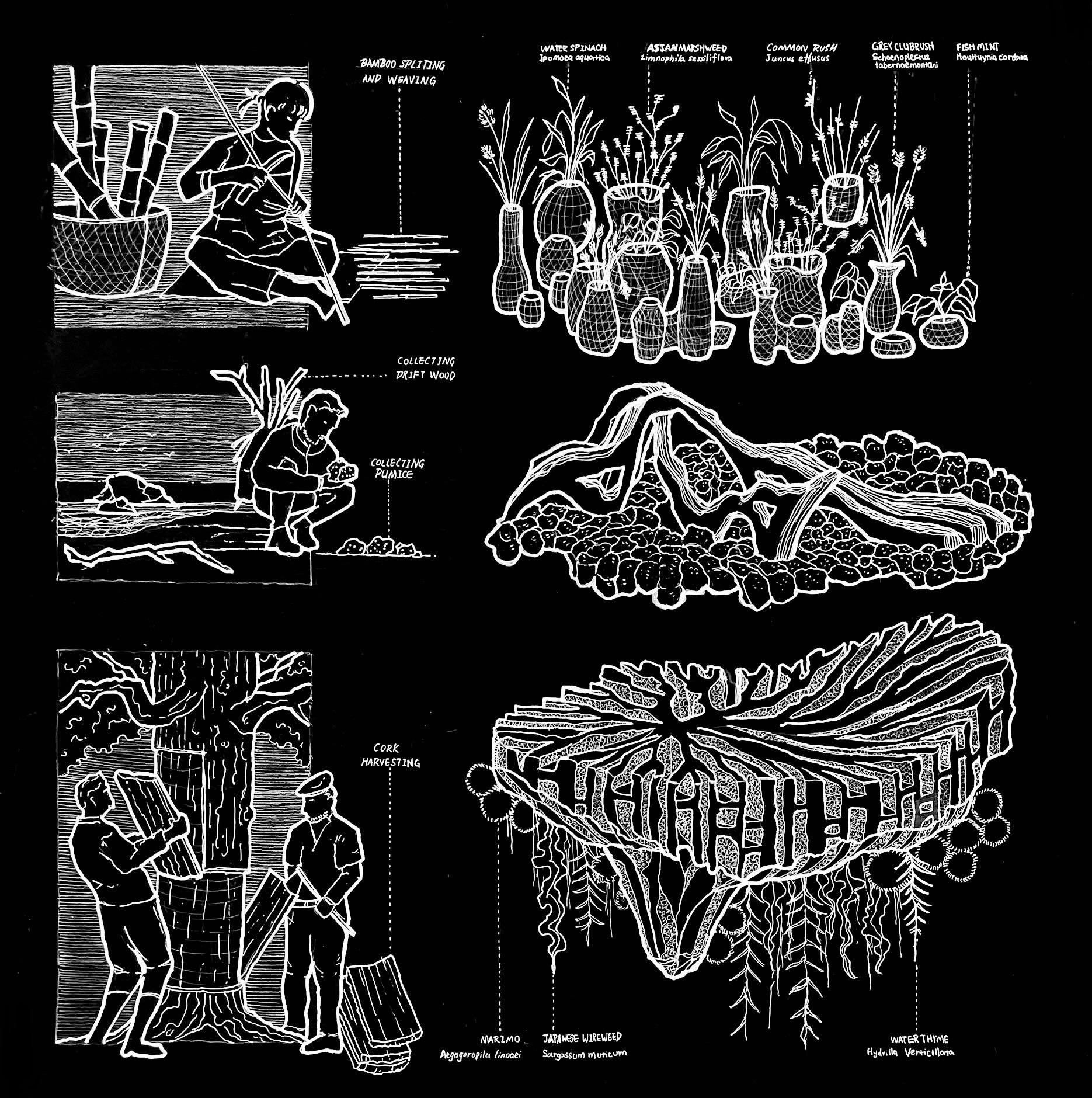

Crafted from bamboo weaving, cork carving, pumice, and driftwood, the island's top layer invites the community to plant native species, becoming both a memorial and a living support for the intertwined lives of the cormorants and fish species.

The making of this floating island creates a communion between creation and nature.

In weaving together bamboo, cork, pumice, and driftwood, human crafts forge a tangible connection to the ecosystem, mirroring the natural world and reflects the relationships found in nature.

The making of this floating island creates a communion between creation and nature. In weaving together bamboo, cork, pumice, and driftwood, human crafts forge a tangible connection to the ecosystem, mirroring the natural world and reflects the relationships found in nature.

As hands plant native species and shape the island’s form, they are participating in a deeper and sacred act of creation. Perhaps through this process, humans become stewards of the river, a relationship of of interdependence, where every thread of life is linked in a shared network.

As hands plant native species and shape the island’s form, they are participating in a deeper and sacred act of creation. Perhaps through this process, humans become stewards of the river, a relationship of of interdependence, where every thread of life is linked in a shared network.

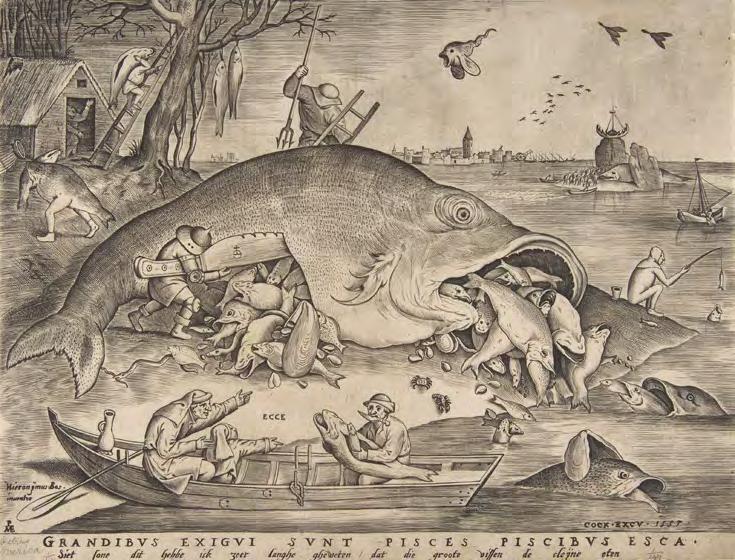

Food Chain

The ecosystem and food chain supported by the Floating Island begins with vegetation planted on the island, and underwater algae growing on cork structures and pumice stones.

These plants and algae serve as a primary food source for insects, larvae, and aquatic invertebrates. Predatory insects such as adult dragonflies hunt smaller insects and lay eggs in water. Fish in the ecosystem consume both insect larvae and algae, and some species lay eggs in the cracks of stones.

As fish grow from eggs to adults, they become prey for larger predators like cormorants. These birds dive to catch fish underwater. After feeding, cormorants perch on driftwood to dry their feathers. 食物連鎖 (shokumotsu rensa)

"Big fish eat little fish", by Pieter Bruegel the elder in 1557, as an allegory of human greed

This miniature world becomes a living mirror to nature.

This miniature world becomes a living mirror to nature.

On cork and pumice, plants and algae take root, giving rise to a small food chain.

On cork and pumice, plants and algae take root, giving rise to a small food chain.

Insects and larvae feeds on the greenery, while fish thrives below. The cormorants, perched upon driftwood after their hunts, complete this web.

Insects and larvae feeds on the greenery, while fish thrives below. The cormorants, perched upon driftwood after their hunts, complete this web.

The creation becomes an offering to the river, a foundation upon which the ecosystem can flourish. Over time, the island is left to its own course, allowed to decompose and merge with the river's ever-changing landscape, becoming part of the natural flow. The island serves as a contribution to the greater cycles of life, where human hands do not dominate the course of nature.

The creation becomes an offering to the river, a foundation upon which the ecosystem can flourish. Over time, the island is left to own course, allowed to decompose and merge with the river's ever-changing landscape, becoming part of the natural flow. The island serves as a contribution to the greater cycles of life, where human hands do not dominate the course of nature.

無常 (mujō)

Impermanence

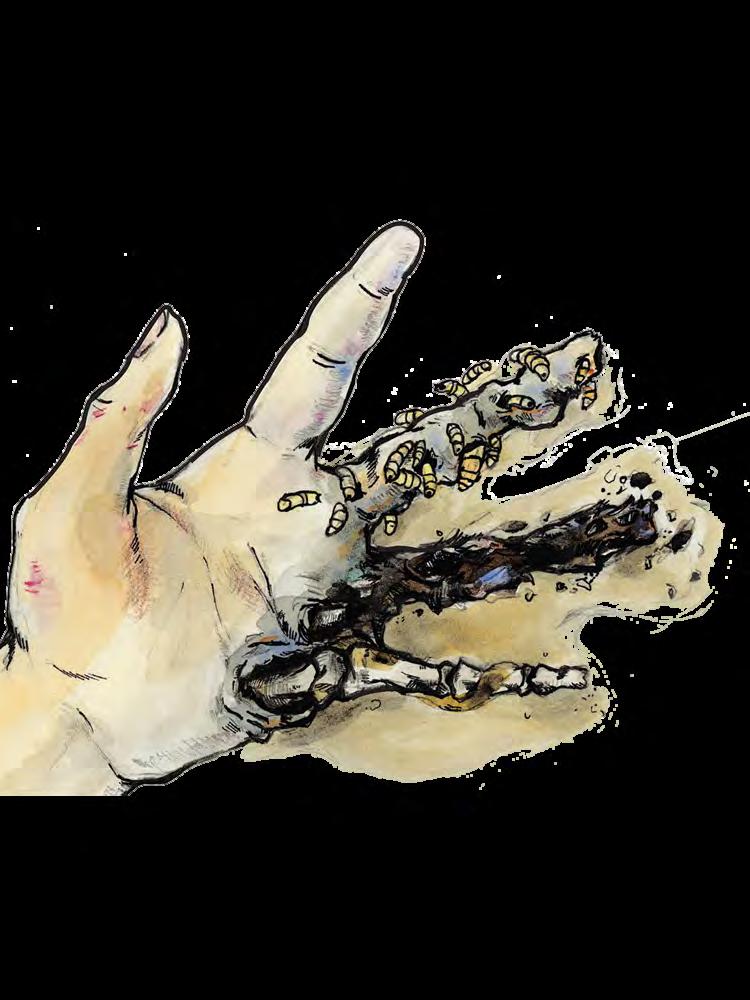

The island's decay begins upon touching water. Bark and bamboo form the initial foundation, with plants rooting throughout the gaps of the structure.

Within months, microorganisms colonize the organic matter and initiate decomposition.

Bamboo's outer layer peels away within a year, while plant roots and insects contribute to breakdown over several years. The island can maintain buoyancy through pumice rocks and air spaces in plant structures (aerenchyma, like lotus pads), as well as the gases (such as methane) released from decay. The birds may also begin to pick away the plants and materials for nesting.

In about a decade, even hardwoods like oak bark decompose, releasing nutrient-rich compost into the evolving aquatic ecosystem.

Human Decomposition Infographic, Chanelle Augustine Stages of decay

The short life of the Ayu fish, lasting only a single year, is a poignant embodiment of the Japanese concept of impermanence.

The short life of Ayu fish, lasting only a single year, is a poignant embodiment of the Japanese concept of impermanence.

This acceptance of life’s ephemerality is deeply rooted in the natural rhythm and everchanging moments of nature.

This acceptance of life’s ephemerality is deeply rooted in the natural rhythm and everchanging moments of nature.

The ides focuses on viewing nature not as an opposition to be conquered but as a force to which humans adapt themselves into; recognizing the cyclical nature of birth, death, and rebirth; accepting death without hostility; and finding beauty in decline.

The ides focuses on viewing nature not as an opposition to be conquered but as a force to which humans adapt themselves into; recognizing the cyclical nature of birth, death, and rebirth; accepting death without hostility; and finding beauty in decline.

浮世 (ukiyo)

Fleeting World

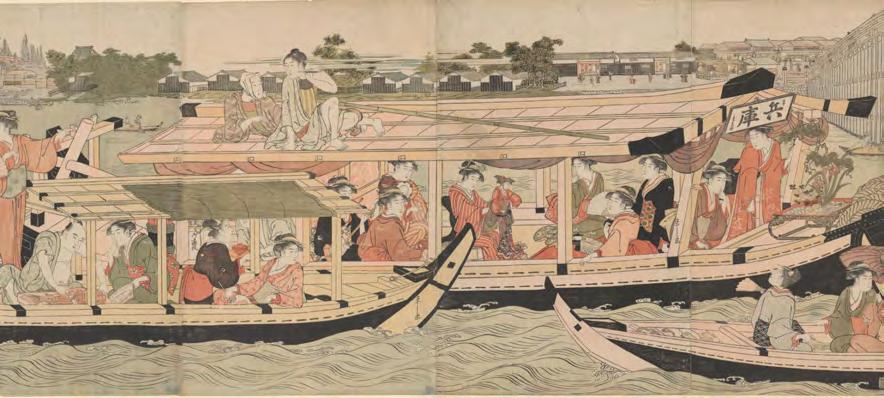

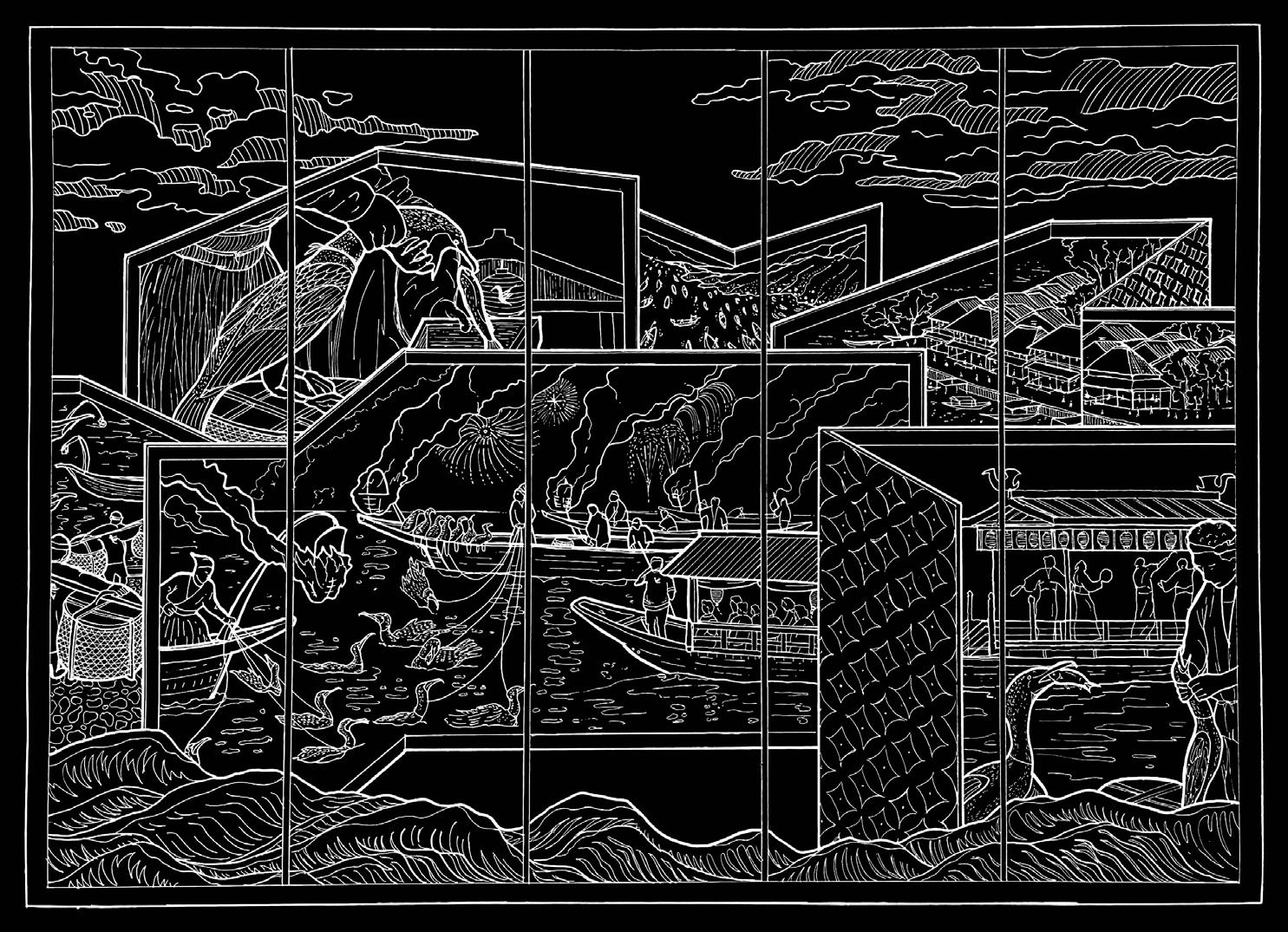

Ukai has been a source of amusement for the Japanese aristocracy since the Heian period, a representation of the worldly opulence and luxury. It was also a tribute to emperors, aristocrats, and foreign visitors. With the rise of industrial fishing, the practice of cormorant fishing has shifted from a vital livelihood to a performance for tourists.

The cormorant fishing event is held annually from May 11 to October 15 beginning at sunset near the upper reaches of Nagara Bridge in Gifu City. The performance is celebrated with fireworks and boat performance.

This practice is designated as an Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property of Japan, making it a significant part of the cultural identity of Gifu City.

鵜飼船御遊 Cormorant Fishing Viewed by

Imperial Court from Boat, 1852

Genji print by Utagawa Kunisada

Cormorant Fishing is one of the popular subject of 浮世绘 (Ukiyo-e), the genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries.

Nowadays, the spectacle attracts over 100,000 visitors annually and generates approximately

$2.5 million USD per year, playing a major role the city's tourism sector.

Nowadays, the spectacle attracts over 100,000 visitors annually and generates approximately $2.5 million per year, playing a major role the city's tourism sector.

However, as the practice become a performed spectacle that resembles a circus, where the cormorants' instincts are repurposed for human entertainment under the guise of cultural preservation.

However, as the practice become a performed spectacle that resembles a circus, where the cormorants' instincts are repurposed for human entertainment under the guise of cultural preservation.

The birds, trained and tethered, perform nightly above fire-lit waters, their movements dictated by centuries-old techniques now shaped by tourism demands.

The birds, trained and tethered, perform nightly above fire-lit waters, their movements dictated by centuries-old techniques now shaped by tourism demands.

Does this transformation honor the tradition, or does it exploit the cormorants as living tools for profit and nostalgia? The line between cultural heritage and commodification blurs, questioning whether the preservation of history justifies the manipulation of living creatures for human fascination.

Does this transformation honor the tradition, or does it exploit the cormorants as living tools for profit and nostalgia? The line between cultural heritage and commodification blurs, questioning whether the preservation of history justifies the manipulation of living creatures for human fascination.

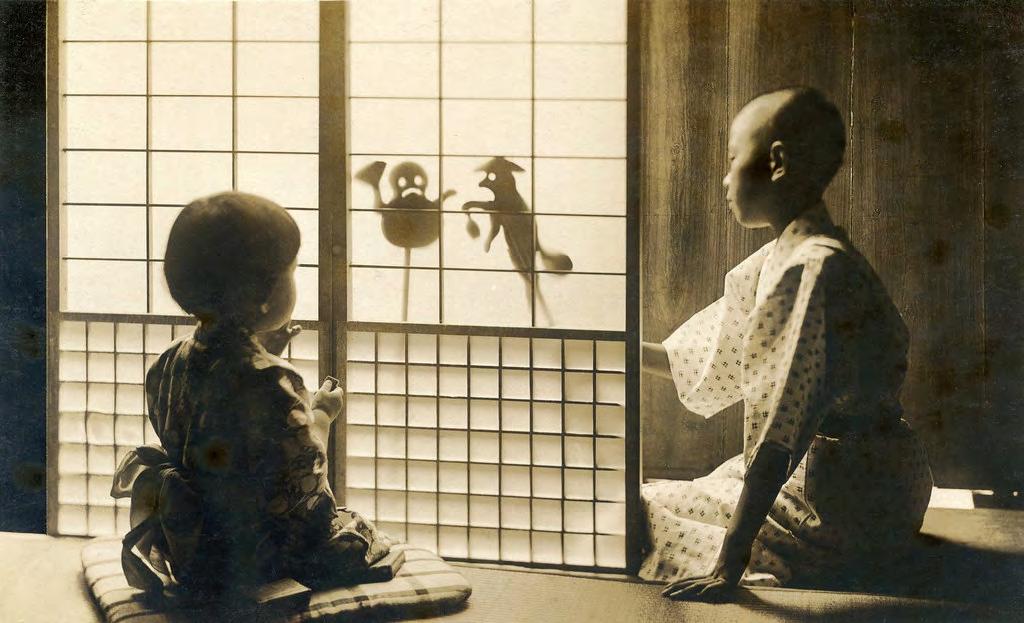

影絵 (kagebōshi)

Shadow Play, Shadow Puppetry

This traditional art form involves manipulating flat articulated figures between a light source and a translucent screen to create moving shadows for storytelling. Shadow puppetry has roots in various Asian cultures and has been present in Japan for centuries, with references dating back to the Edo period (1603-1868).

The performance include the use of a series of paper puppets as characters, translucent screen to display the scene, a light source to create shadows.

The stick used to manipulate shadow puppets is commonly called a "sao" (竿). These sticks are often made of bamboo or wood, designed to control the movements of the puppets during performances.

Japanese Shadow Puppets 1910s

A boy using a shoji (paper sliding door) to perform a kagebōshi (shadow play) for his younger sister.

Image from an antique postcard.

In Japanese folklore, shadows and reflections could identify supernatural beings. Shadows evoke intrigue and the allure of the hidden. They suggest that much of reality lies beneath the surface, unseen and unknowable.

In Japanese folklore, shadows and reflections could identify supernatural beings. Shadows evoke intrigue and the allure of the hidden. They suggest that much of reality lies beneath the surface, unseen and unknowable.

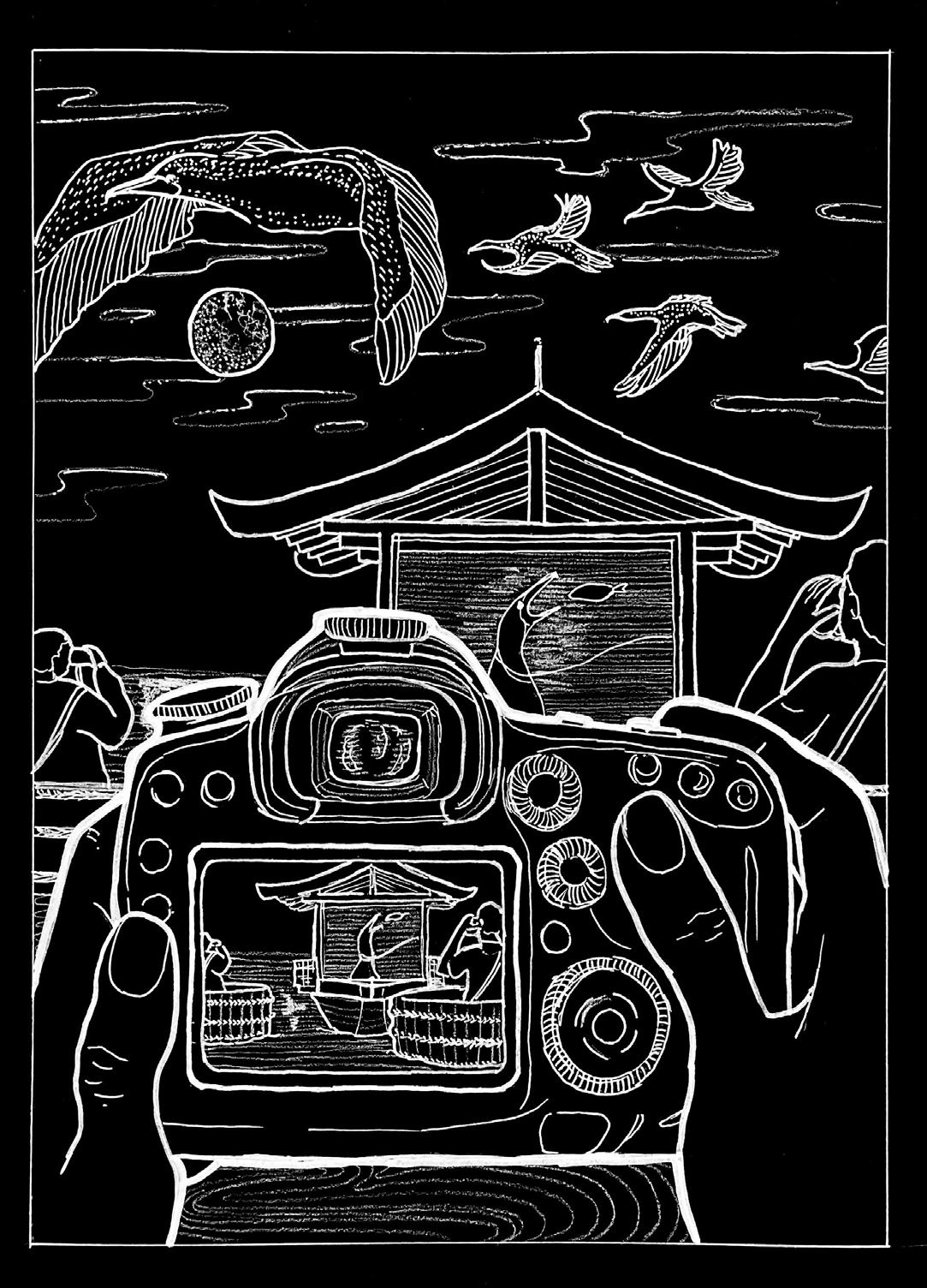

Shadow play and puppeteering thus could become a medium to invert the traditional roles of humans and cormorants in the context of cormorant fishing.

Shadow play and puppeteering thus could become a medium to invert the traditional roles of humans and cormorants in the context of cormorant fishing.

The story-telling of the shadow play could perform cormorant fishing while reframe to set the bird as the focal point of the story.

The story-telling of the shadow play could perform cormorant fishing while reframe to set the bird as the focal point of the story.

Through the puppeteering, the visitors not only view the practice of cormorant fishing though the play, but gains a view into the the cormorant’s experience of tethering and fishing. Shadows could depict a transformation of the river from a natural habitat into a stage of human manipulation.

Through the puppeteering, the visitors not only view the practice of cormorant fishing though the play, but gains a view into the the cormorant’s experience of tethering and fishing. Shadows could depict a transformation of the river from a natural habitat into a stage of human manipulation.

舟遊 (Funaasobi) Boating

Originally, yakata-bune (屋形船), traditional pleasure boats, were used as luxurious floating spaces for leisure and entertainment during the Edo period (1603–1868). The print by Chōbunsai Eishi captures the vibrant festival that heralded the start of summer.

Traditional Japanese tub boats, known as tarai-bune (たらい舟), are small, round boats typically made from wood and bound with bamboo or metal bands. These vessels are designed for fishing and seaweed harvesting in shallow waters.

Today, tarai-bune and yakata-bune cater to visitors seeking romanticized experiences of Japan’s past. They are transitioned from functional tools and symbols of elite luxury into curated tourist attractions, reflecting the commodification of cultural heritage.

During the shadow play performance, the tourists resides in the tarai-bune (tub boats), while the puppeteers and the puppets perform the play from the yakata-bune (pleasure boat). With the tub boats tied to the pleasure boat, mimicking the tethered connections of the cormorants tied to the cormorant fisherman.

During the shadow play performance, the tourists resides in the tarai-bune (tub boats), while the puppeteers the puppets perform the play from the yakata-bune (pleasure boat). With the tub boats tied to the pleasure boat, mimicking the tethered connections of the cormorants tied to the cormorant fisherman.

While the puppets and puppeteer reflect the concept of control within the practice of cormorant fishing, this reversal between the tourists and performer questions the dynamic of dominance by repositioning the tourists as the cormorants.

While the puppets and puppeteer reflect the concept of control within the practice of cormorant fishing, this reversal between the tourists and performer questions the dynamic of dominance by repositioning the tourists as the cormorants.

In this setting, perhaps the tether is transformed to a symbol of mutual connection rather than control.

In this setting, perhaps the tether is transformed to a symbol of mutual connection rather than control.

The word "chōchin" combines two kanji: Cho (提): "to hold in hand". Chin (灯): "lamp". The naming reflects their historical use of being carried or hung. Gifu lantern are made from bamboo and washi paper, the lantern is famous for detailed illustrations. A tradition continue to be used since Edo era. They are often seen used in festivals and on the yakata-bune (屋形船) for boating and viewing cormorant fishing.

The print Hasui Kawase shows the bonfire (篝火, kagaribi) as the center of focus, serving as the light source that illuminates the scene.

Both the lantern and bonfire share their role as traditional Japanese lighting methods for the performance of cormorant fishing.

Gifu lantern and lantern making

Lanterns and Bonfires serves as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds.

Lanterns and Bonfires serves as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds.

In Shinto beliefs, lanterns are used to guide ancestral spirits during Obon festivals (a celebration of ancestral spirits). While the bonfire have been used in purification rituals and to mark sacred spaces.

In Shinto beliefs, lanterns are used to guide ancestral spirits during Obon festivals (a celebration of ancestral spirits). While the bonfire have been used in purification rituals and to mark sacred spaces.

While the light attract fish during cormorant fishing, within the alternative performance of shadow puppetry, the lights instead attracts the visitors and pleasure seekers. The lights guides the tourists to depart from their earthly real and experience the ritual of the past.

While the light attract fish during cormorant fishing, within the alternative performance of shadow puppetry, the lights instead attracts the visitors and pleasure seekers. The lights guides the tourists to depart from their earthly real and experience the ritual of the past.

障子 (shoji)

Translucent Screen, Scrim

Shoji screens evolved from Chinese folding screens, becoming popular in Japan during the Kamakura Period (1123-1333). They have remained an integral part of Japanese architecture and design for over a thousand years.

The shoji screens are valued for their ability to let light through and blur the boundary between interior and exterior. The washi paper creates a unique effect by refracting and diffusing light.

The screens can symbolize barriers, thresholds, or veils, enriching the narrative with metaphorical layers

Geisha Kneeling by Samisen Case, from the series Three Elegant Beauties at a Drinking Party, 1814. Kikukawa Eizan (Japanese, 1787–1867)

Behind the shoji screen, the flickering light of a simulated fire dances, casting shifting silhouettes of cormorants and fishermen onto the translucent paper.

The cormorants’ sleek forms appear larger than life, their necks curving gracefully as they dive and emerge, tethered to unseen hands. The rhythmic sliding of the background panels mimics the flow of the river, each motion revealing and concealing the interplay between man and bird.

With the changing movements of the cormorant puppet, the screens transform into a canvas of shifting emotions— serenity, struggle, and fleeting unity between human and nature.

鳥観察 (chō kansatsu)

Bird Watching

Bird watching in Japan traces its roots to Edo-period bird keeping, evolving into a more observational practice by the early 20th century.

The origins of bird watching can be traced back to practices of hunting and collecting, where the human fascination was deeply tied to utility and dominance. In earlier centuries, birds were pursued for their feathers, food, or as trophies, with collectors amassing specimens for sport or scientific studies. Over time, as the need for conquest gave way to conservation, the act of observing live birds in their natural habitats became a celebrated pastime.

But are is this practices truly in harmony with conservation, or do they prioritize human enjoyment over the welfare of birds?

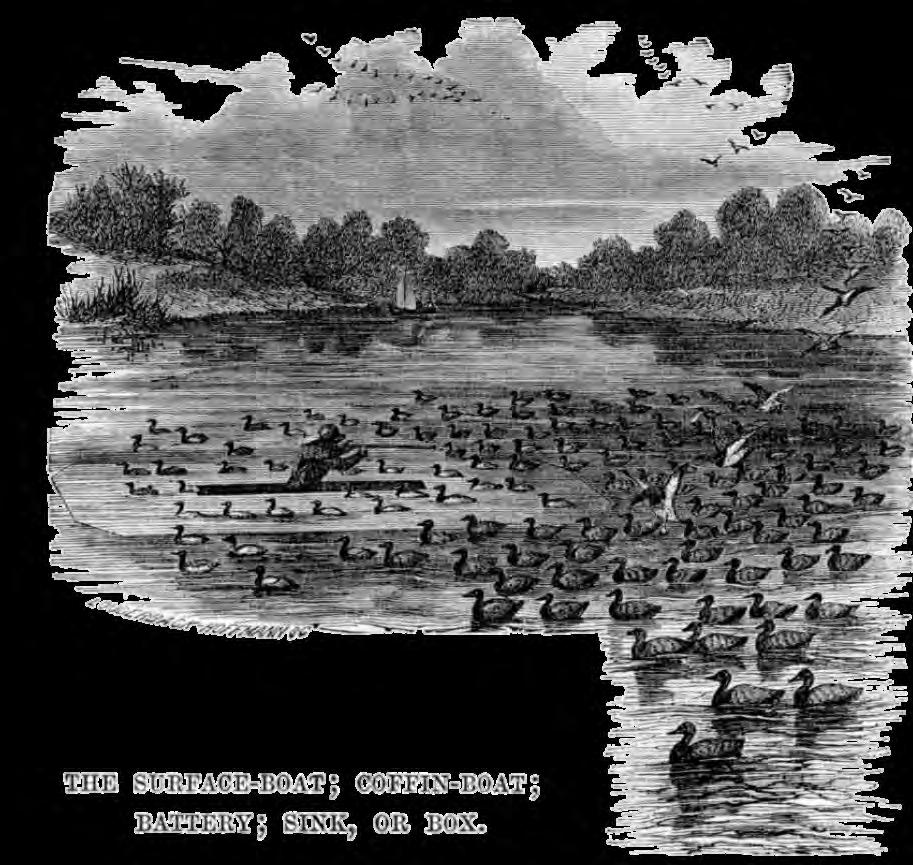

A list of the common names for the sinkbox on wood engraving by Louderback and Hoffman, waterfowl hunting, 1840s.

Anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose describing an attempt to wipe out endangered flying foxes in a small white town in Australia, she writes:

Anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose describing an attempt to wipe out endangered flying foxes in a small white town in Australia, she writes:

“Man is the only animal that shoots other creatures with paintball guns, and when the creatures flap around in terror or fall to the ground injured and in shock, man is the only animal that cheers.”

“Man is the only animal that shoots other creatures with paintball guns, and when the creatures flap around in terror or fall to the ground injured and in shock, man is the only animal that cheers.”

With the presence of cormorants upon the Nagara River, the reversal of performance may allow the cormorants to become the observers, casting their gaze onto the human tourists and bird watchers who gather to admire them.

With the presence of cormorants upon the Nagara River, the reversal of performance may allow the cormorants to become the observers, casting their gaze onto the human tourists and bird watchers who gather to admire them.

Where the "wild" cormorants and their domesticated counterparts symbolically exchange roles: the once-tethered birds move freely, while the human audience, captivated and constrained by the ritualistic spectacle, mirrors the traditional role of the controlled.

Where the "wild" cormorants and their domesticated counterparts symbolically exchange roles: the once-tethered birds move freely, while the human audience, captivated and constrained by the ritualistic spectacle, mirrors the traditional role of the controlled.

野 (ya)

"Wild" : Freedom / Untamed Nature

When the cormorants are free, what does "wild" mean for the cormorants and for the humans?

Nina-Marie Lister's work suggests that the concept of "wild" for animals in the humandominated world is no longer about untouched wilderness but rather about resilience and adaptation within shared spaces.

In the presence of humans, "wild" animals often navigate landscapes shaped by anthropogenic forces—urban areas, agricultural fields, or fragmented habitats— blurring the traditional dichotomy between wild and domesticated.

We are challenged to rethink what "wild" means when human influence is omnipresent.

Cormorant drying their wings after diving on a "NO FISHING" sign

Are urban raccoons, who thrive in cities by scavenging and adapting to human behaviors, any less "wild" than their forest-dwelling counterparts? Animals like cormorants, which have been both revered and vilified, occupy a liminal space where their survival strategies intersect with human activity.

Are urban raccoons, who thrive in cities by scavenging and adapting to human behaviors, any less "wild" than their forest-dwelling counterparts? Animals like cormorants, which have been both revered and vilified, occupy a liminal space where their survival strategies intersect with human activity.

In the bustling fish market, a wild cormorant swoops down from the sky, its wings cutting through the air as it plunges toward the piles of freshly caught fish. The bird, having fished alongside its human counterpart, now appears as a bold intruder, attempting to claim the very catch it helped retrieve.

In the bustling fish market, a wild cormorant swoops down from the sky, its wings cutting through the air as it plunges toward the piles of freshly caught fish. The bird, having fished alongside its human counterpart, now appears as a bold intruder, attempting to claim the very catch it helped retrieve.

"Wild" : Freedom / Untamed Nature

As presented in Yoshinori Mizutani's photo album HANON (2016), inspired by the ever growing population of birds in cities. In Tokyo, cormorants are not just a symbol of nature; they become urban interlopers, navigating the human-made structures of the city, and challenging the fragile balance between human presence and the wild.

"The spectacle of the birds lined up on overhead wires gainst the Tokyo sky seemed to like a page from a book of Hanon exercises - as if the black birds themselves were music notes, making their music up above my head"

Bir’yun is the shimmer, the brilliance, and, the artists say, it is a kind of motion. Brilliance actually grabs you. Brilliance allows you, or brings you, into the experience of being part of a vibrant and vibrating world... when one is captured by shimmer, one experiences not only the joy of the visual capture but also, and more elegantly as one becomes more knowledgeable, ancestral power as it moves actively across the world.

Bir’yun is the shimmer, the brilliance, and, the artists say, it is a kind of motion. Brilliance actually grabs you. Brilliance allows you, or brings you, into the experience of being part of a vibrant and vibrating world... when one is captured by shimmer, one experiences not only the joy of the visual capture but also, and more elegantly as one becomes more knowledgeable, ancestral power as it moves actively across the world.

Rose, Deborah Bird. “SHIMMER: WHEN ALL YOU LOVE IS BEING TRASHED.”

Rose, Deborah Bird. “SHIMMER: WHEN ALL YOU LOVE IS BEING TRASHED.”

In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, 51–63.

In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, 51–63.

University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Two Point One Million Cormorants

Two Point One Million Cormorants

Two Point One Million Cormorants