ARCHITECTURE PORTFOLIO

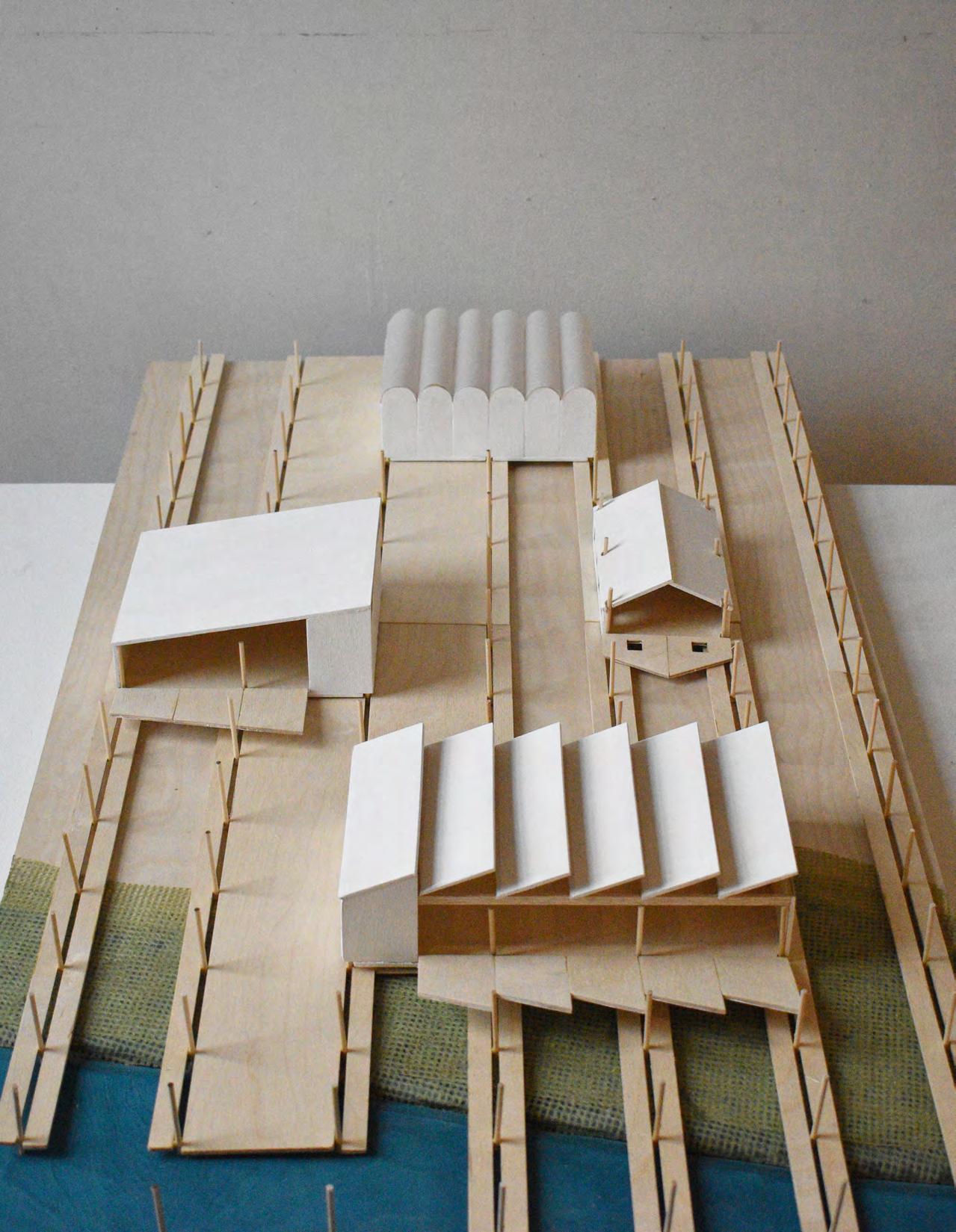

CO-OP HOUSING + OYSTER FARM

Fall 2023 | Arch 103G | Armando Hashimoto

In collaboration with Estephania Granados

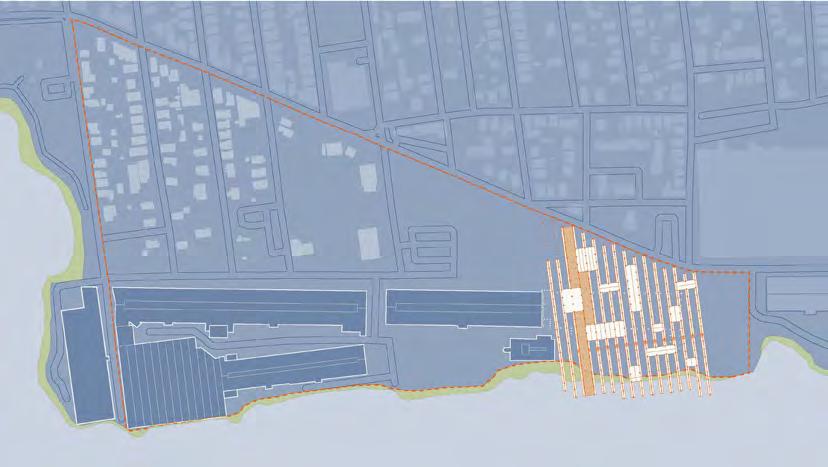

The Cloyster grows and migrates inland in the same manner as the salt marshes lining the Acushnet River: As sea levels rise, buildings are disassembled and reassembled further from the water’s edge. The development supports various ecological efforts already underway in New Bedford, including water purification and salt marsh restoration. Breaking with traditional private land ownership, co-op members must participate in oyster cultivation and salt marsh restoration in exchange for residence.

Presented for final review at RISD and La Laguna, CDMX, Mexico.

Alexandra Croft | M.Arch ‘25 | RISD

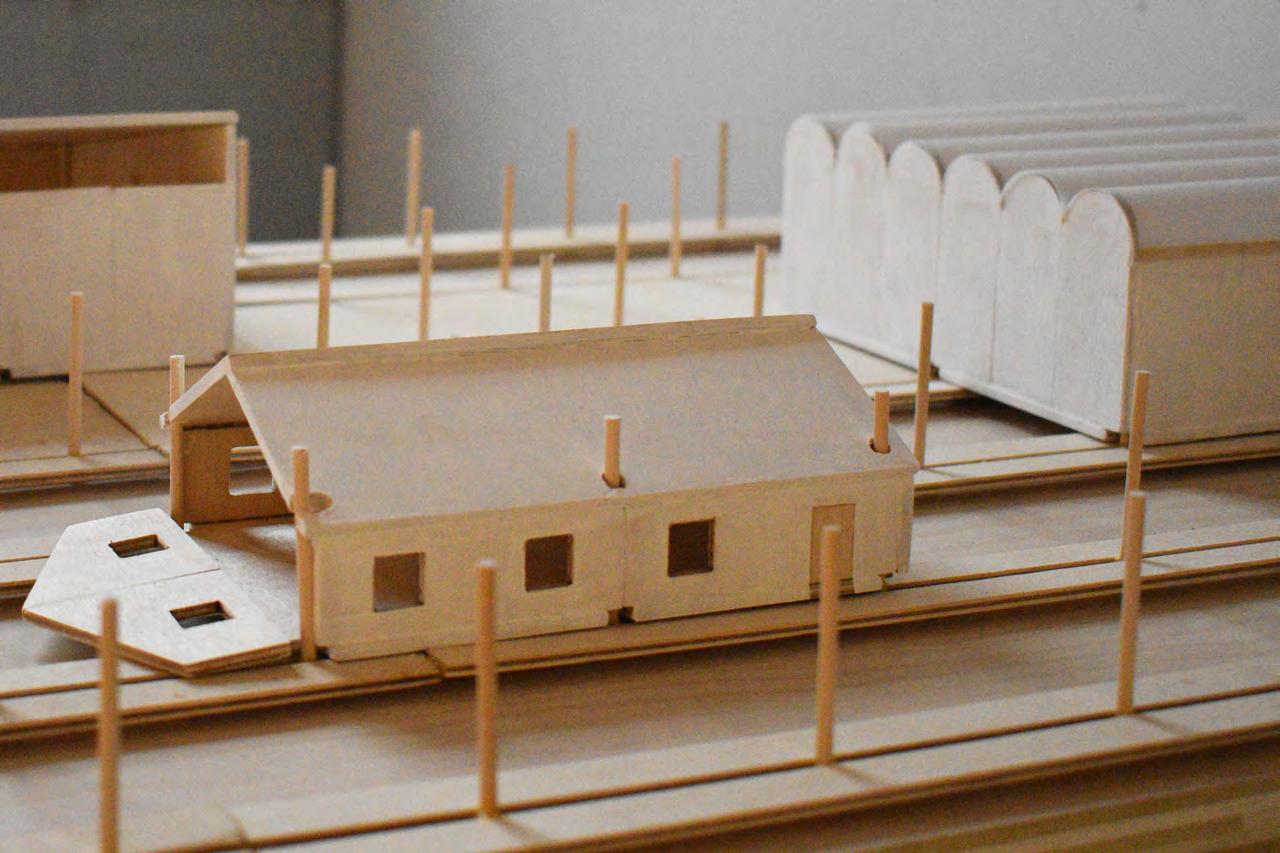

A variety of rooflines distinguish residences from other buildings serving the community. An oyster processing facility, rec center, and greenhouse enable ecological work occuring on site while doubling as gathering space for residents. Community events are open to residents and visitors alike, and take place on wide bands of decking placed intermittently between docks.

Stop-motion of development at: vimeo.com/1070533490/28c0083b79

UPWELLERS

SORTING TABLES

ADPI MESH BAGS

SHELL CRUSHER

TUMBLER

SPAT CULTURE (GROWING BEDS)

LARVAL TANKS

ALGAE GROWING TANKS

BREEDING BEDS

Oyster habitats are submerged in the Acushnet River at the end of each dock in vertical gardens and mesh bags. Residents are responsible for monitoring their health and growth. Full-time oyster facility employees see the oysters through every other stage, from hatching to crushing old shells for recycling.

Dis- and reassembly of the buildings occurs periodically on “Migration Day,” when public buildings’ walls are lowered to host a celebration for Cloyster residents and visitors. The oyster facility unfolds into a cocktail bar, the greenhouse becomes a book shop, and the rec center holds live music and a farmers market.

Residents can make use of this flexibility by opening their homes to accommodate small businesses, such as a cafe or shop, bringing commercial activity to the community.

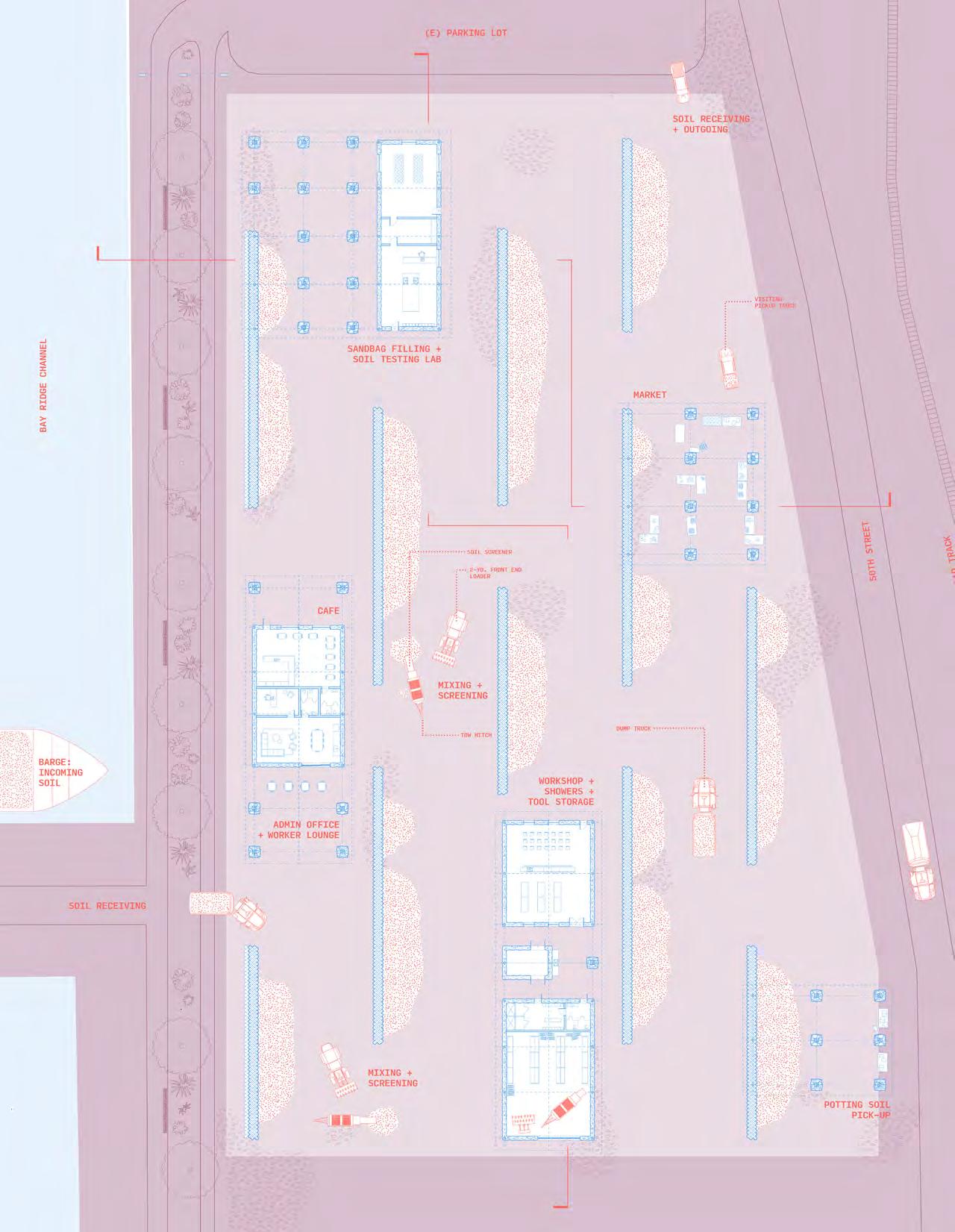

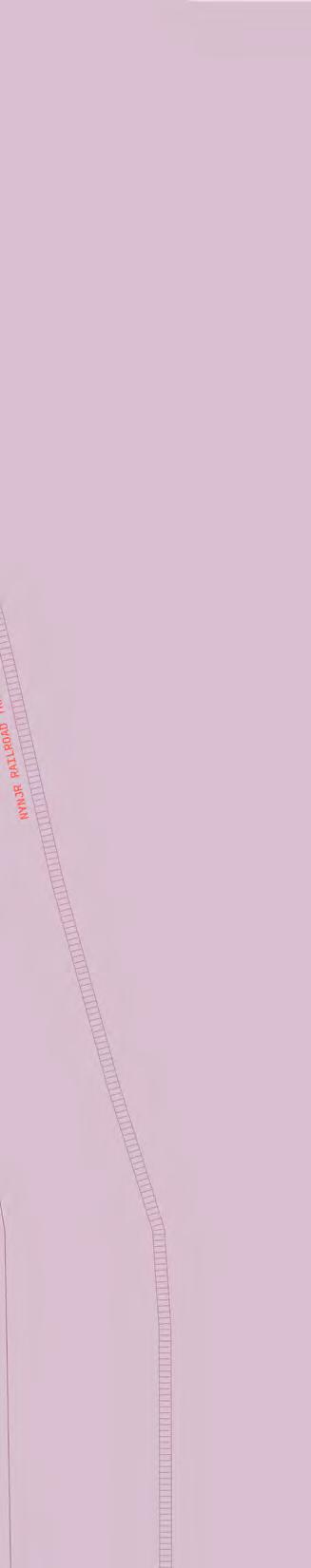

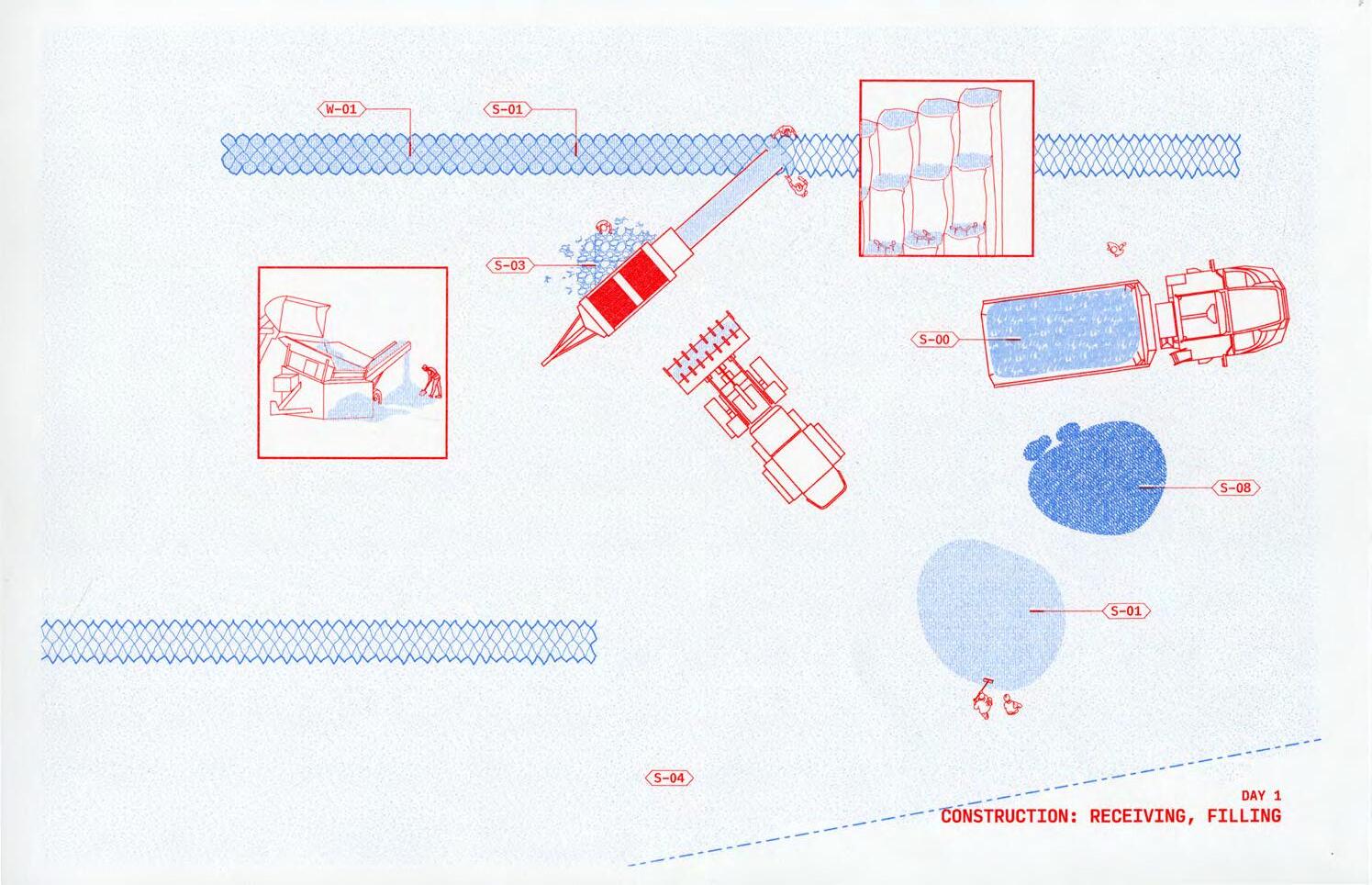

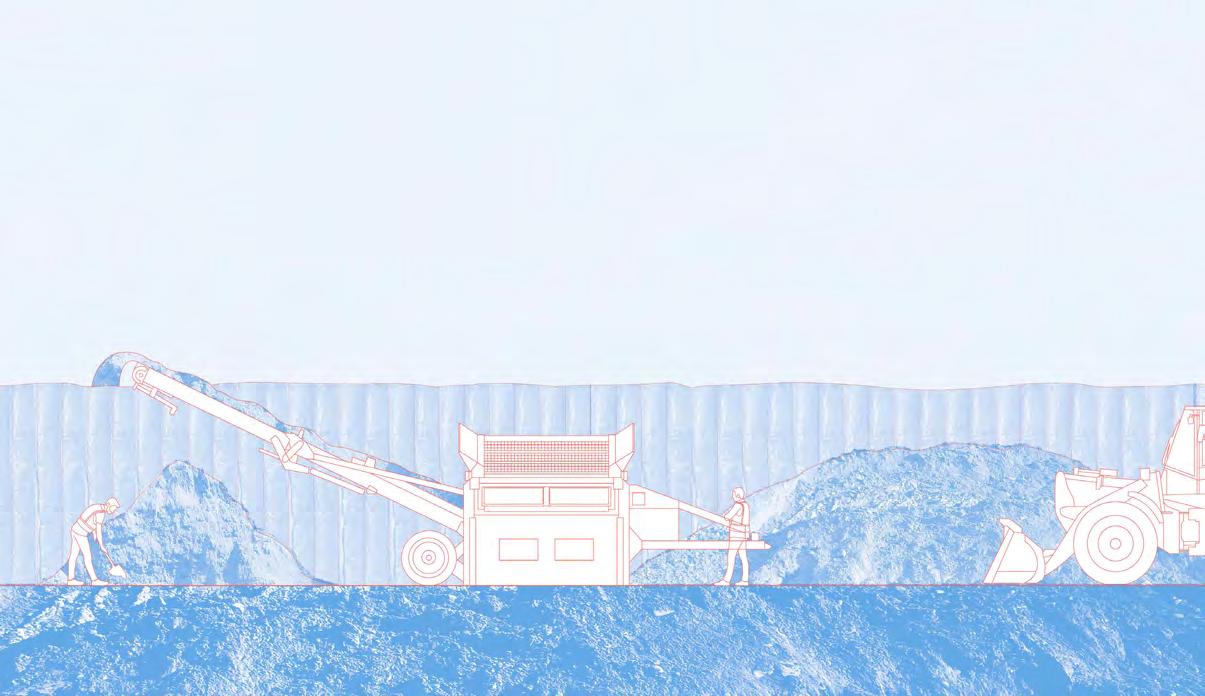

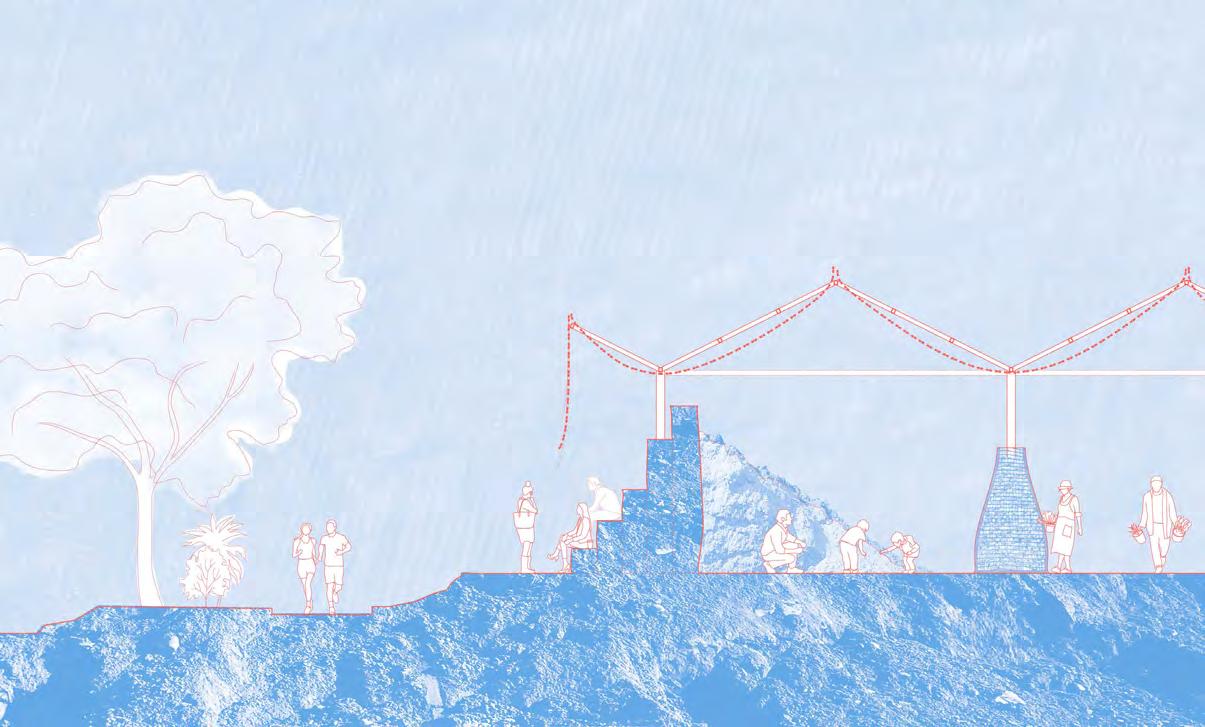

Spring 2024 | Arch 21ST | Amelyn Ng

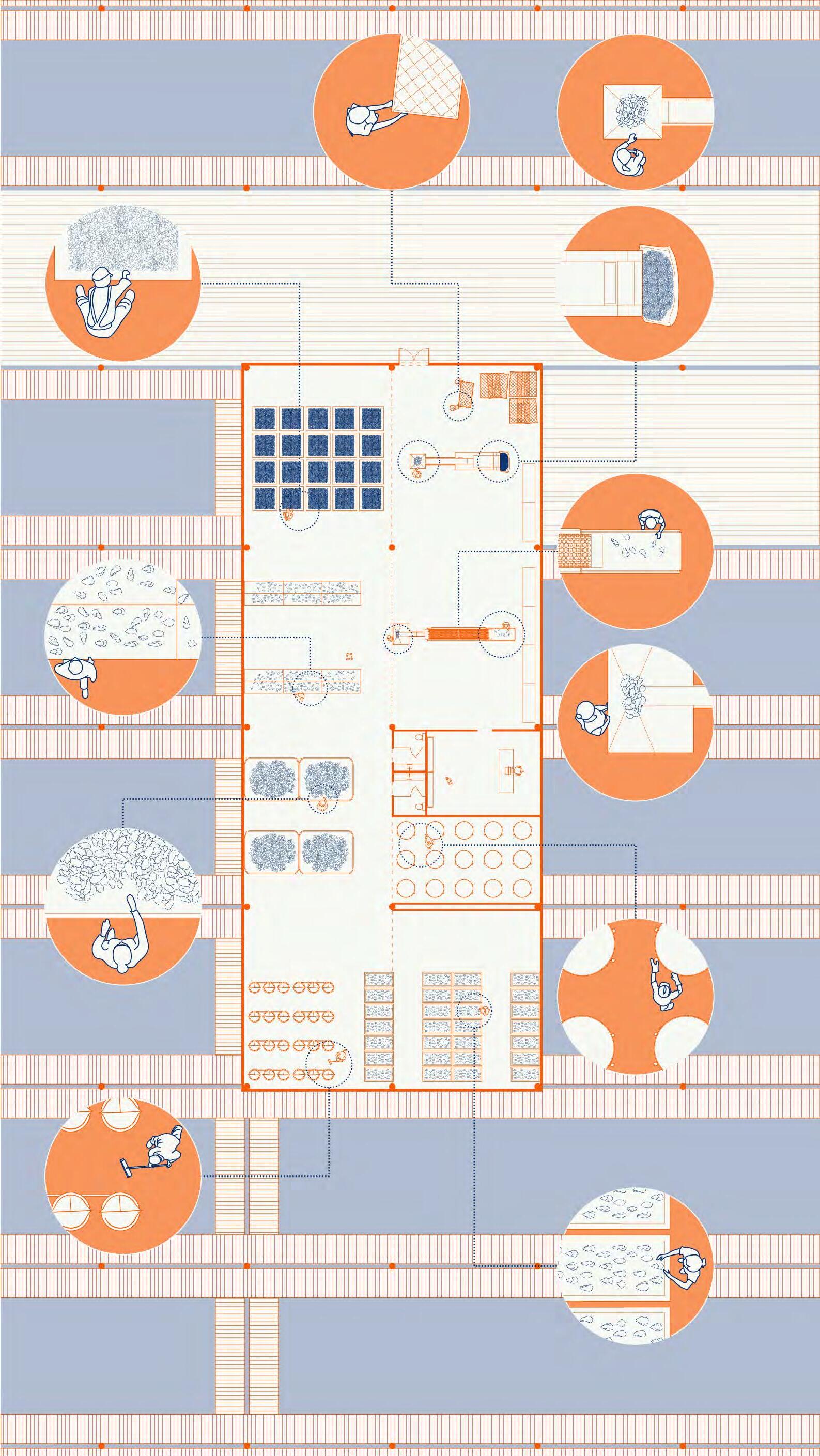

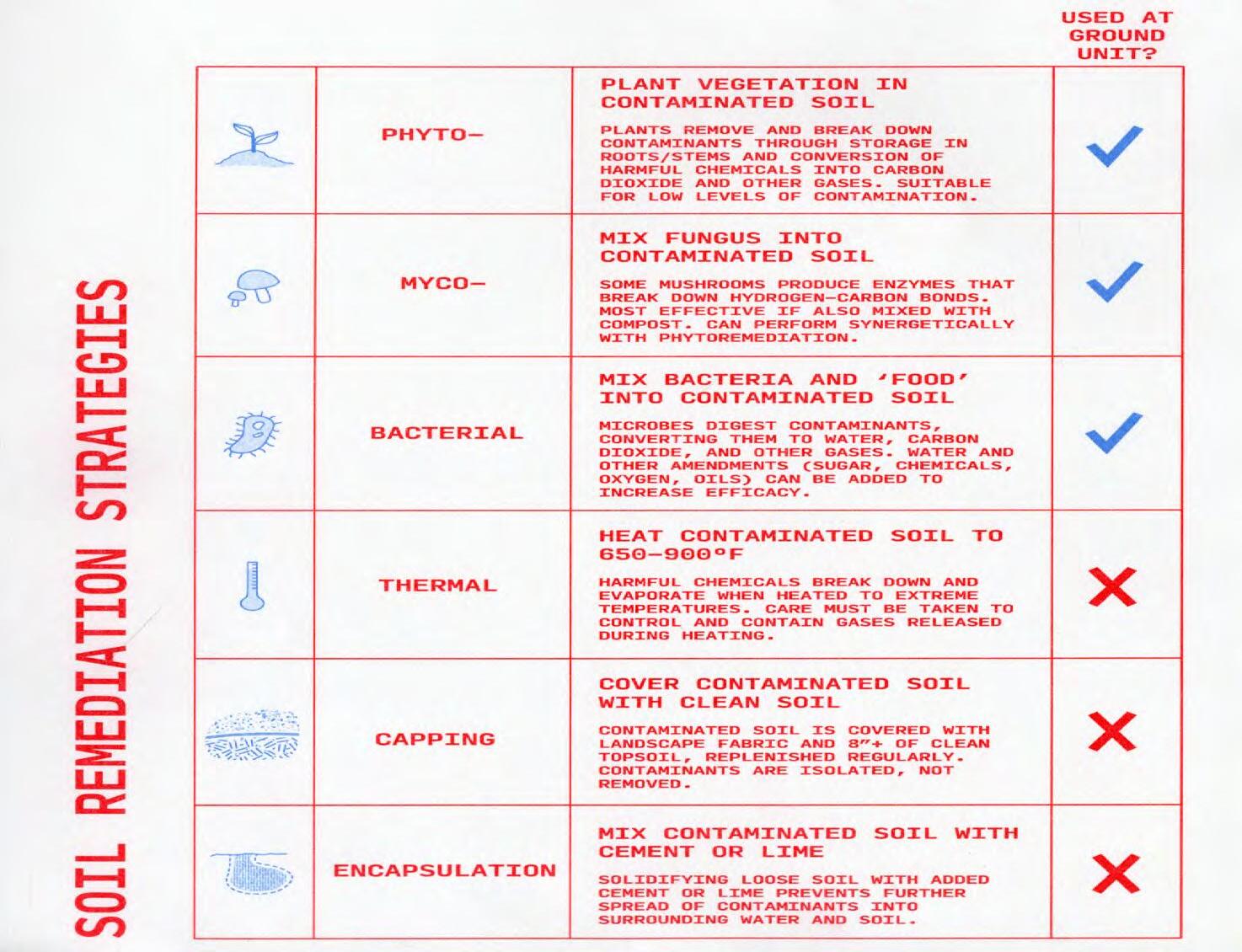

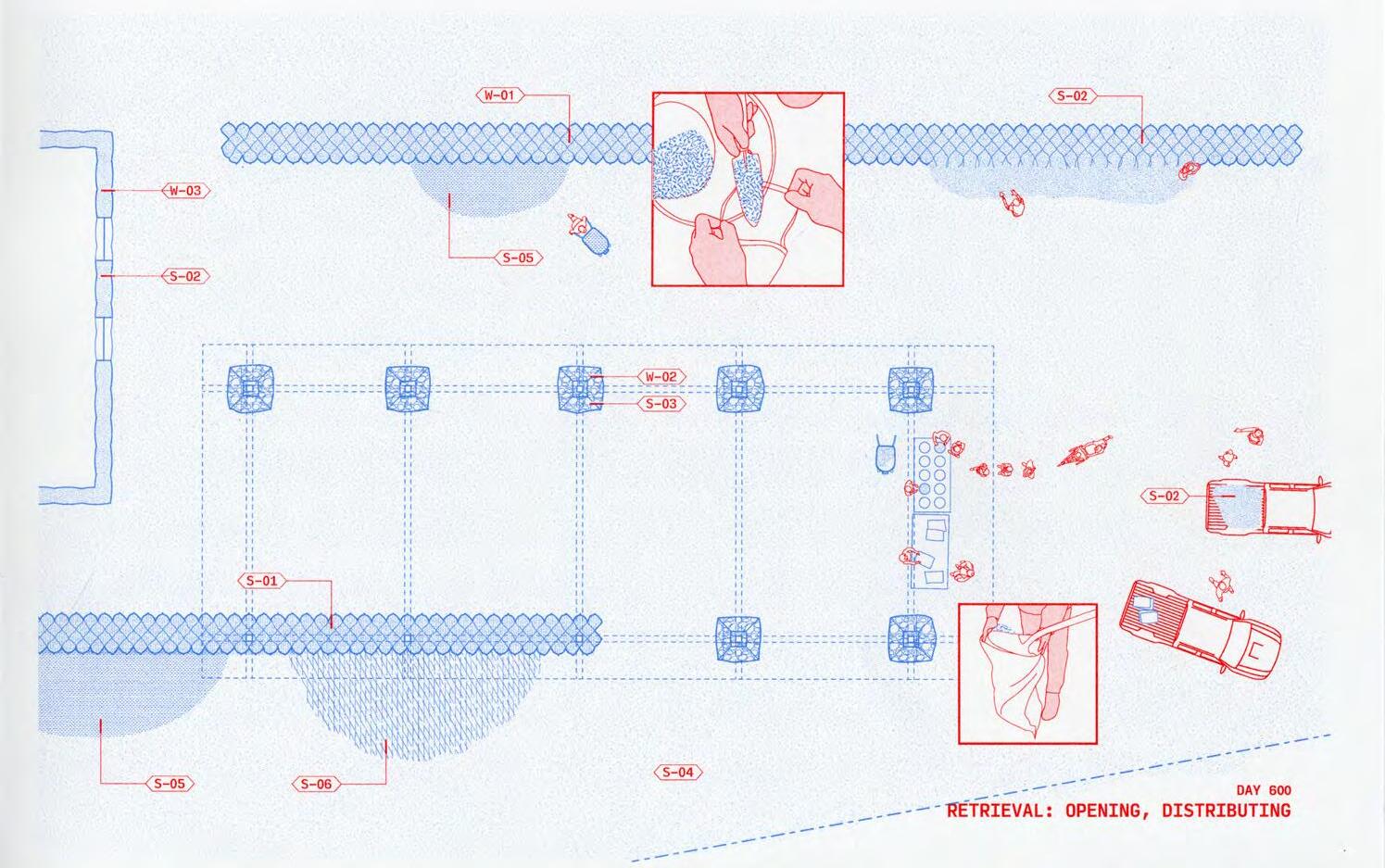

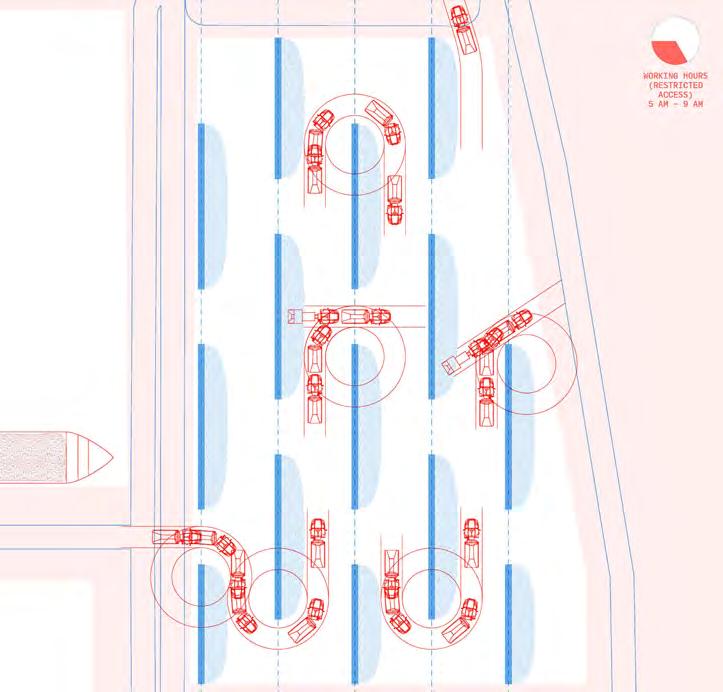

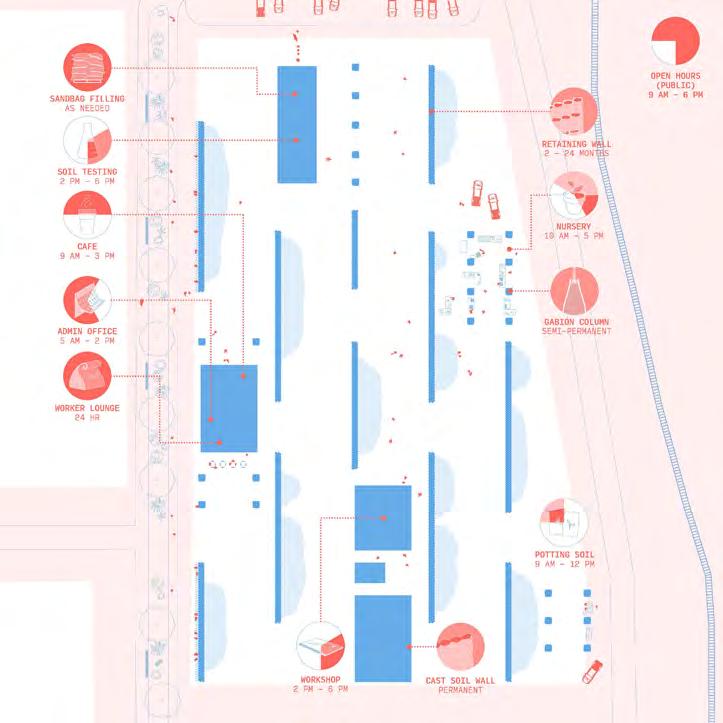

Soil and contamination have a reciprocal relationship: clean soil is used to neutralize dangerous toxic materials, yet is susceptible to contamination by spilled chemicals. Excavated soil is categorized as solid waste but can be recouped under a Beneficial Use Determination for new applications. Sunset Park is full of industrial activity that poses a significant environmental risk. Ground Unit acts as a resource to nearby business with regard to their environmental impact by remediating excavated soil, leading community workshops, and providing soil testing services. Ground Unit houses and displays the physical labor required for managing high volumes of material, centering soil in discussions of New York’s waste systems and sustainability goals.

Alexandra Croft | M.Arch ‘25 | RISD

and remediated which double of clean, Buildings walls, whose machinery aisles. Informal activate small-scale, movements

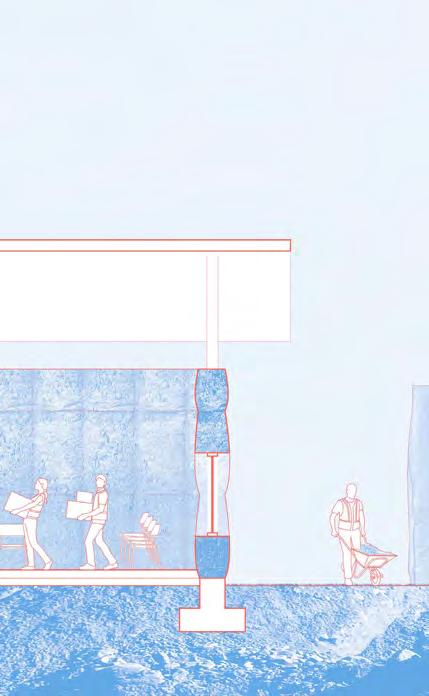

Contaminated soil is delivered to Ground Unit remediated inside vertical tarp pockets, double as retaining walls for the storage clean, remediated soil.

Buildings are interspersed between these whose layout is determined by the heavy machinery frequently circulating through the Informal program like open-air markets the storage bays and allow for a small-scale, intimate relationship with material movements and remediation.

While soil is remediated via the introduction of microbes, fungus, and plants, the community gathers on site for workshops, markets, and recreational activity along the waterfront.

The components of Ground Unit are conceptualized as a kit of parts to be deployed as the opportunity arises. It includes the soil-filled tarp retaining wall, aggregate-filled gabion column, veiled canopy structure, and informal furniture.

Stop-motion video at: vimeo.com/1070532072/985f8e02de

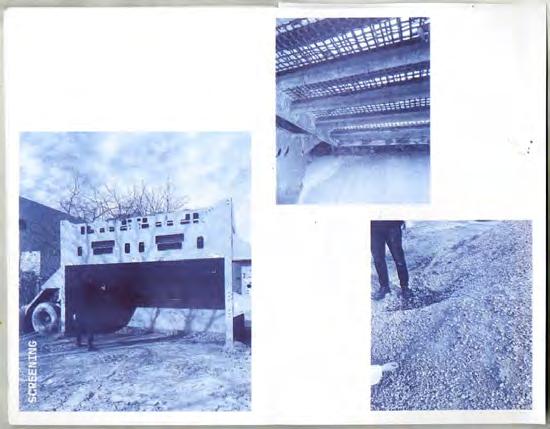

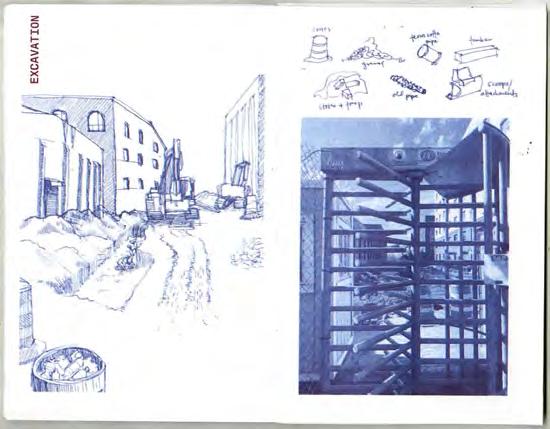

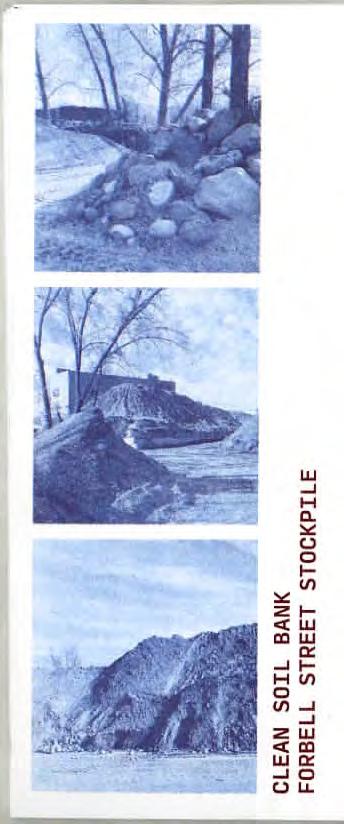

Select pages from a travel dossier display sites of importance, such as the Forbell Street Clean Soil Bank. Soil tectonics (piles, angles of repose, contained vs. loose), as well as the material’s presence in the community, were important drivers in developing the project’s program.

Spring 2023 | Arch 102G | Ryan McCaffrey

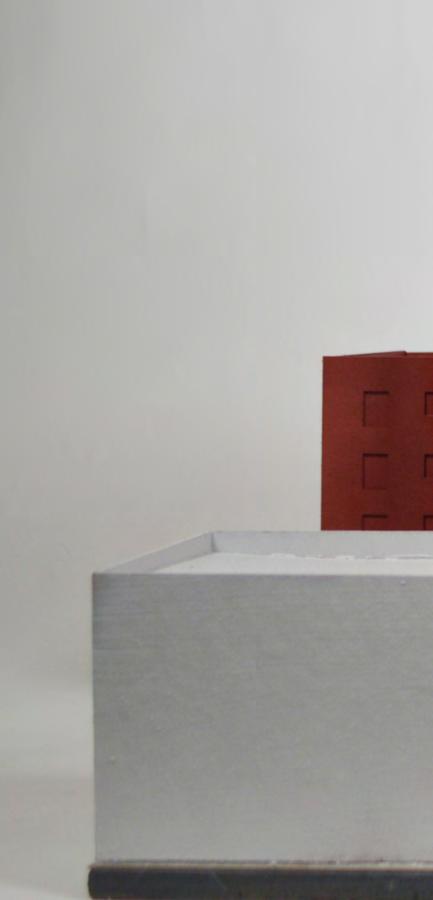

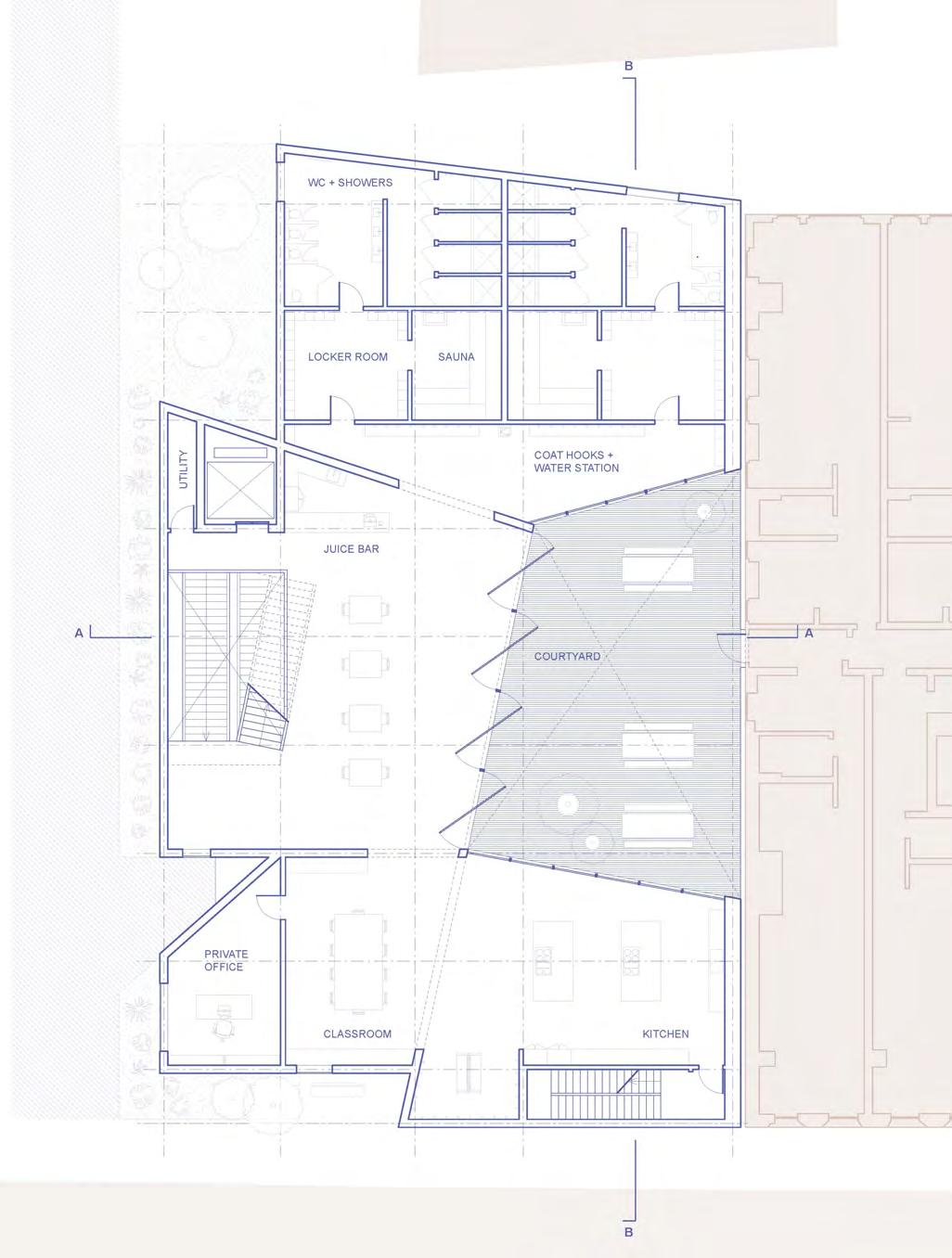

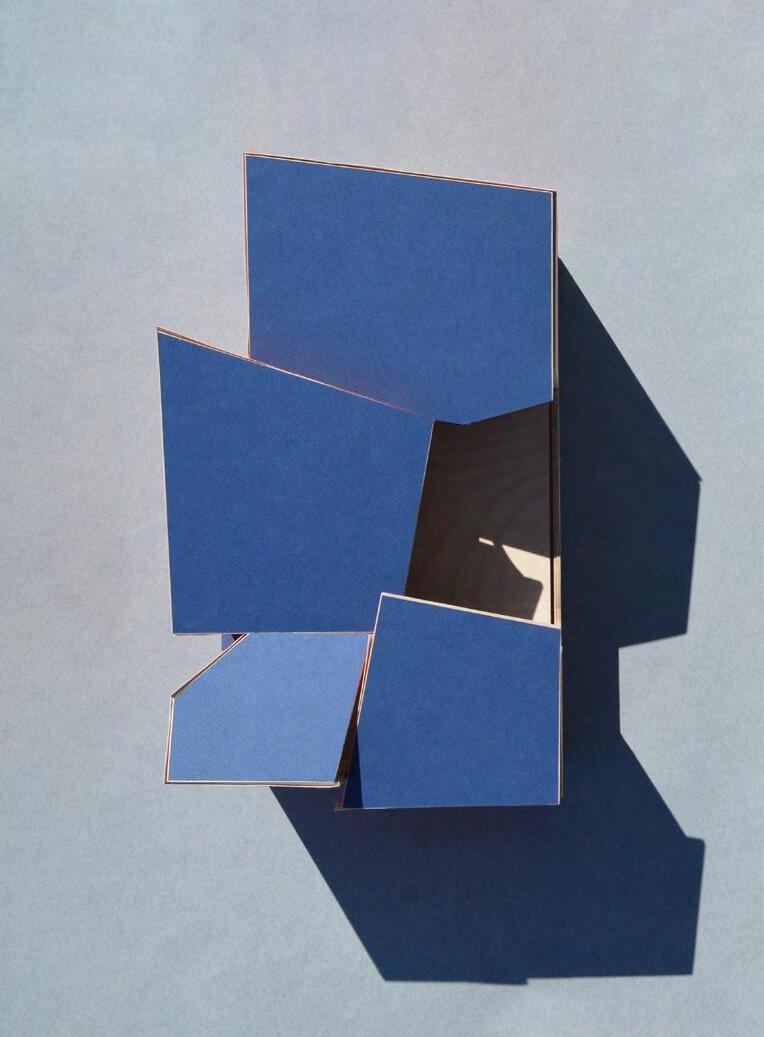

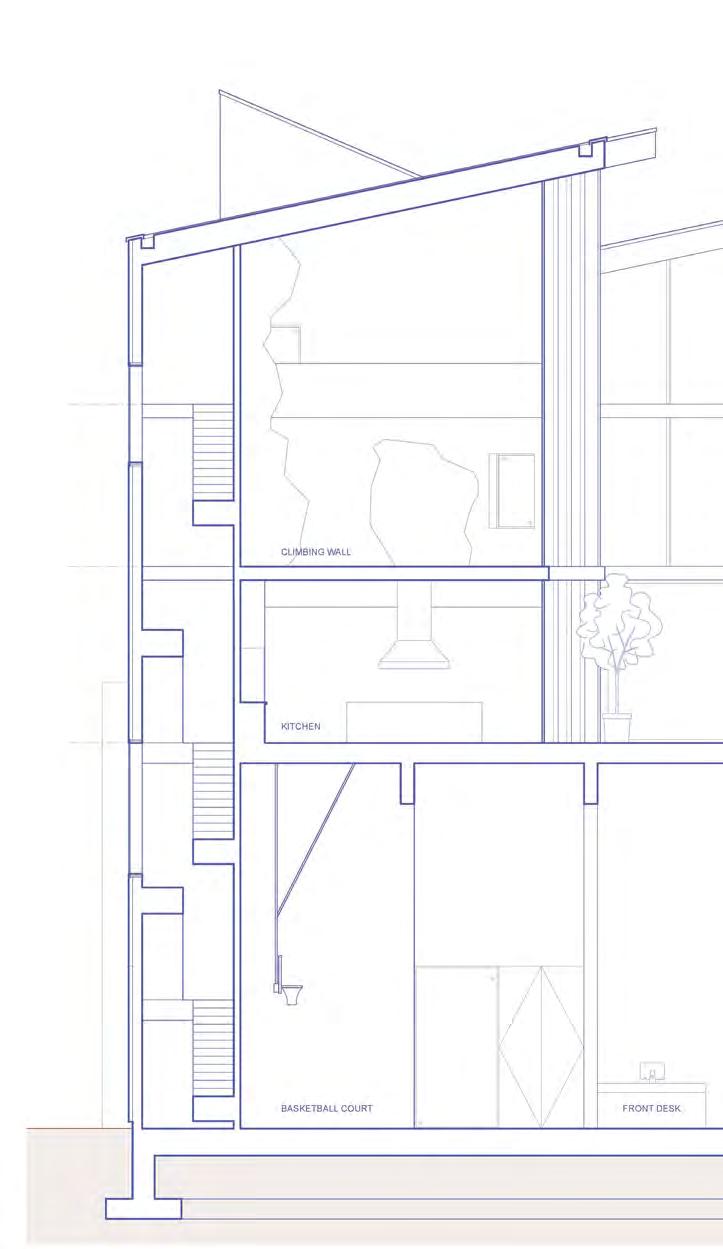

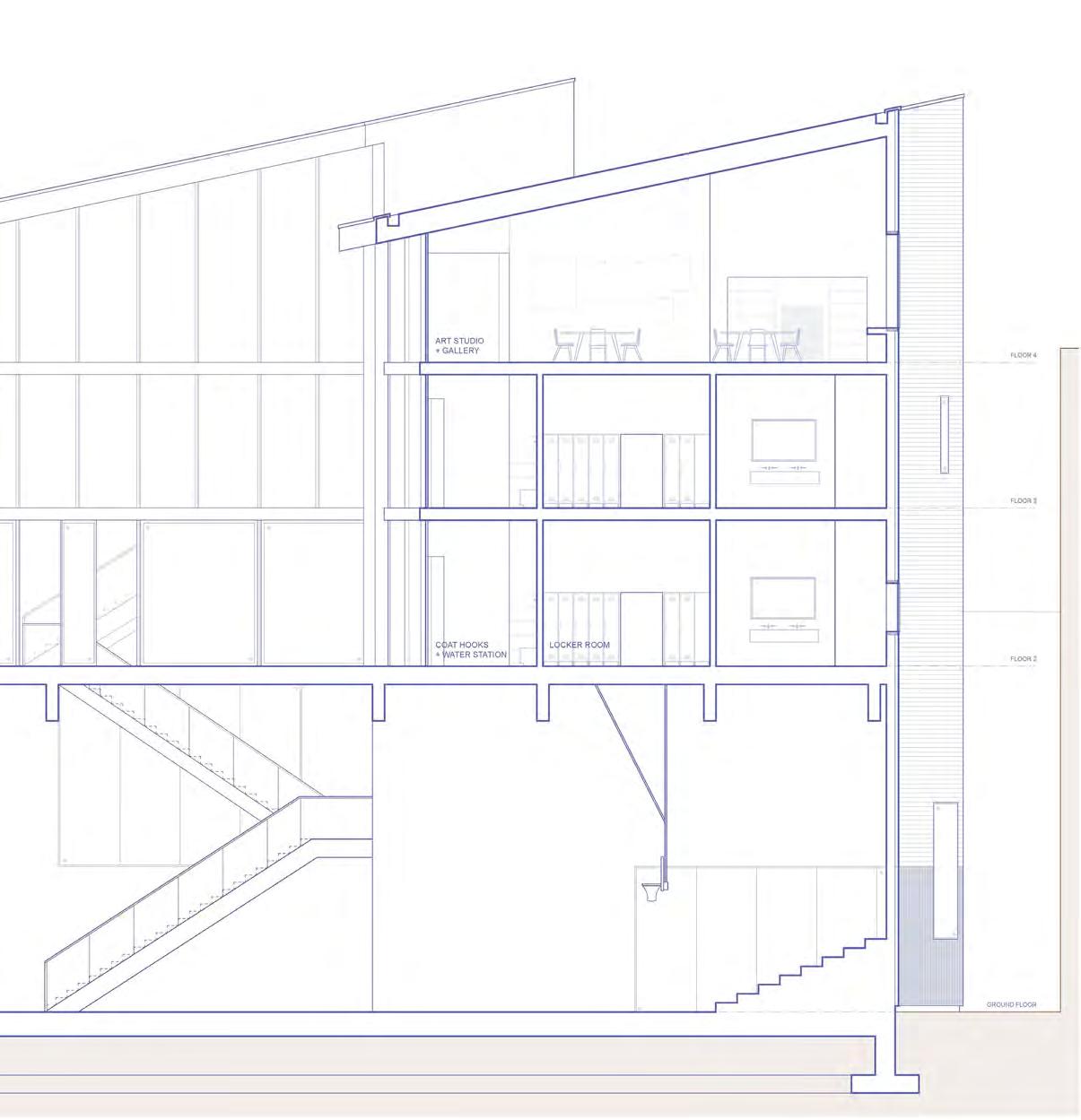

Bastion confronts the street with a rigid exterior that belies the skew and fragmentation to be discovered inside. A continuous brick shell wraps four distinct volumes clustered around a central void. Regular, orthogonal geometry intersects with skewed elements, best observed from the main stair, which twists away from its adjacent wall at upper floors.

Joiner photo collages draw attention to the rich textural qualities of brick and fortress-like character of the surrounding buildings. The location poses a challenge: to engage with the impenetrable language of Providence’s existing fabric, yet be inviting to members of the public. Large openings break up heavy exterior walls, teasing visual access from the street.

Concealed from the street and ground floor, a central courtyard is revealed at the second floor. Community center visitors and artists in the live-work studios next door can enjoy access to the outdoor seating and assembly space here.

Fall 2023 | Seminar: ReAssembly | Evan Farley

In collaboration with Adrian Pelliccia

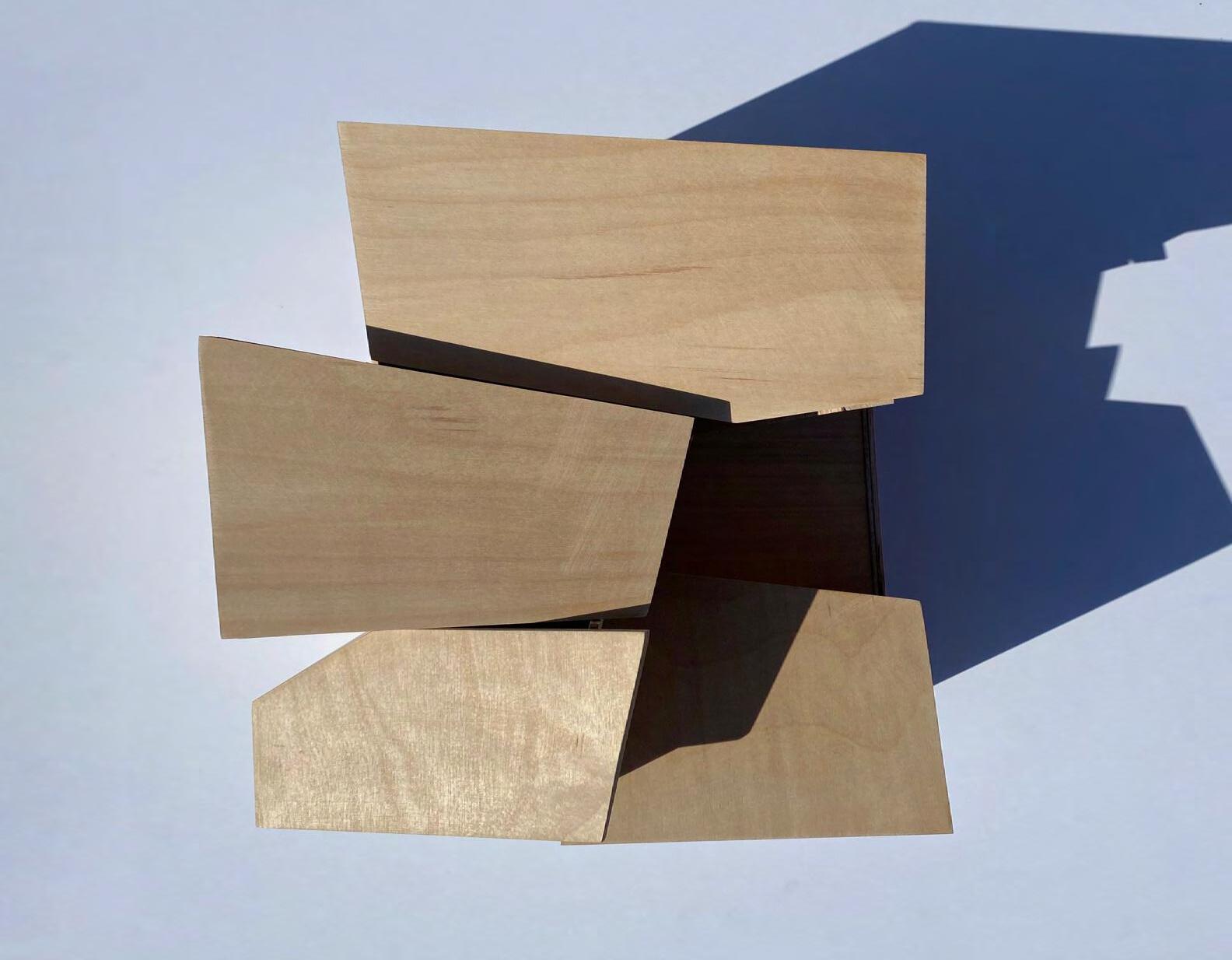

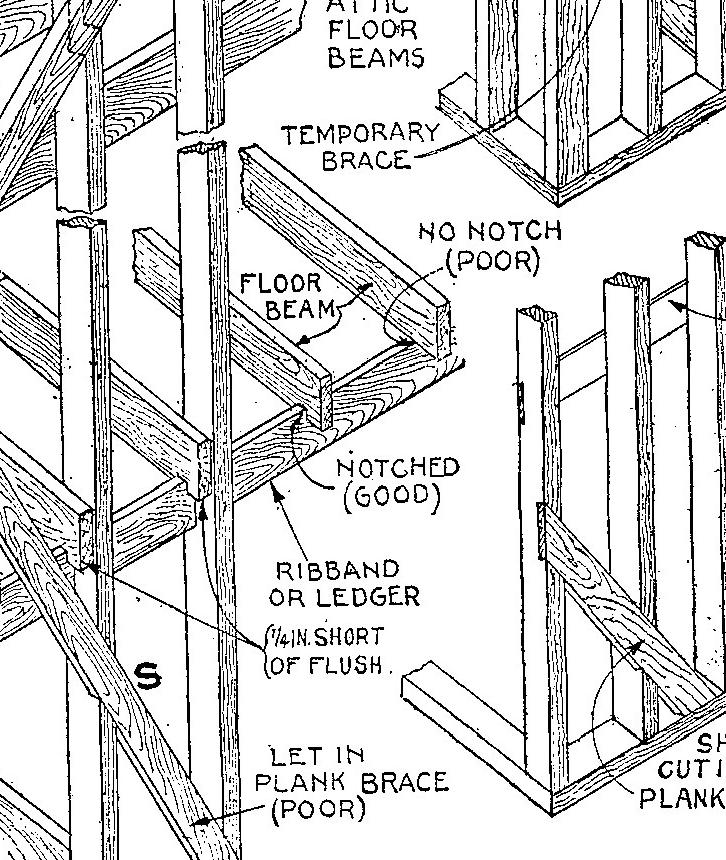

Using the 2021 American Framing pavilion as a point of departure, Good / Poor engages with familiar light-frame wood construction elements— wall panels, bridging, birdsmouth notches— and recombines them into unconventional configurations. By contrast to the inexact nature of wood framing, the precision of a CNC router allows for customized angles and dimensions at each point of connection. Visibly poor construction methods achieve surprising stability due to this insertion of hyper-precise technology into an approximate practice, challenging rigid definitions of “best practice” in wood-frame construction.

Alexandra Croft | M.Arch ‘25 | RISD

American Framing (2023) cites Audels Carpenters and Builders Guide (1923), a resource featuring diagrams that establish a rigid dichotomy of “good” and “poor” wood construction methods: It’s good practice to notch your floor joists, but poor practice to notch cross-bracing into studs, etc. A modeled inventory of framing elements variously adheres to and flouts tradition. When separated from the logic of a larger assembled building, the pecularities of their component parts become at once familiar and strange.

GOOD / POOR

The CNC cuts full-depth notches and half-lap joints from standard 2x4 lumber. Machining calls attention to wood’s relative irregularity, dimensional instability, and tendency to warp. The diagram speaks Audels’ good/poor binary language while misapplying framing standards (notching, lapping, butting), allowing the difference between the good and poor to become confused.

Process: CNC milling and assembly

Fall 2022 | Arch 202G | Sam Sheffer + Evan Farley

In collaboration with Estephania Granados

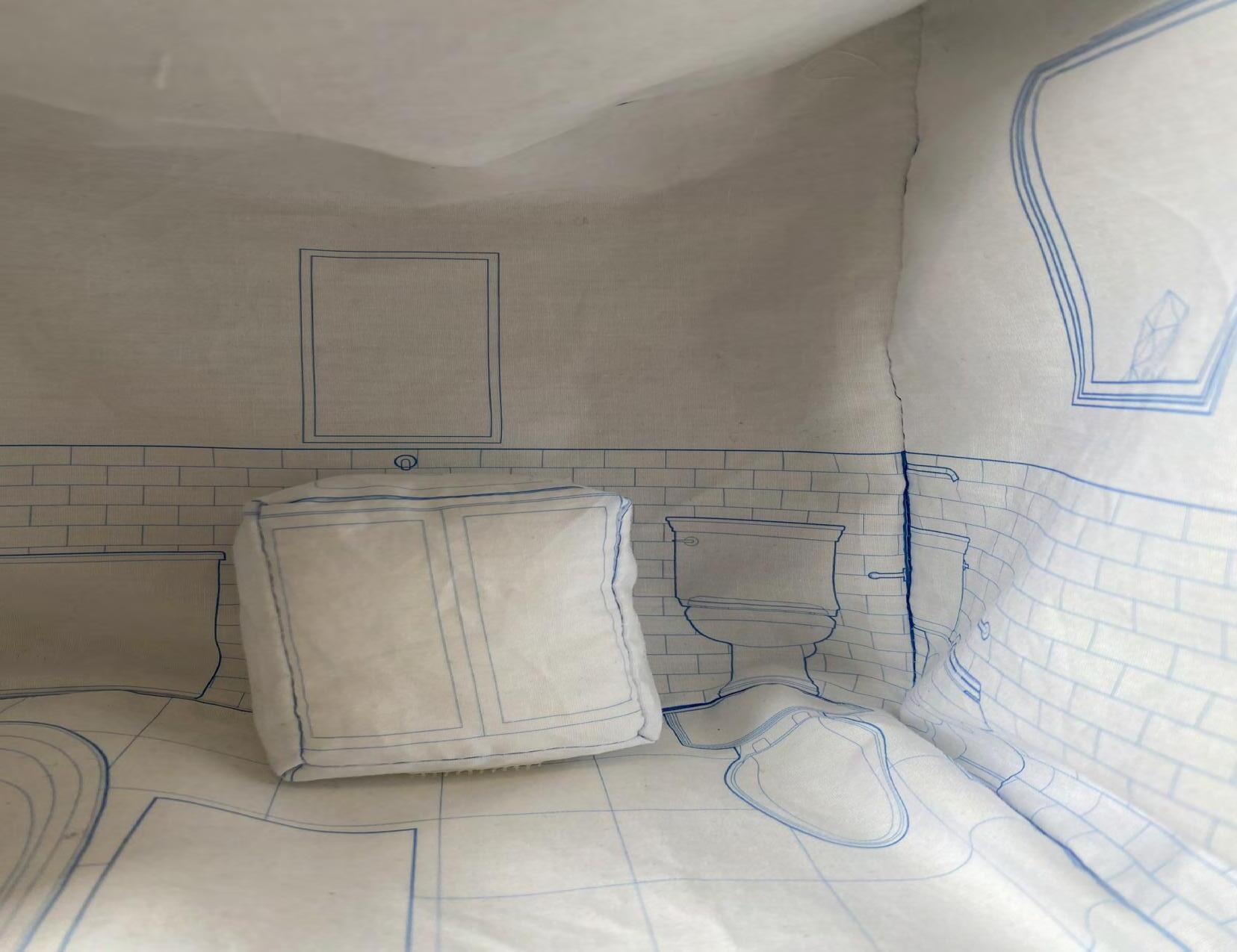

In this project, a dollhouse acts as a physical analog for BIM software. The familiar blue and white Revit interface becomes tactile in soft fabric and polyester stuffing. Similar to design options in Revit, “room suits” (fabric slipcovers) dress blank white boxes, facilitating endless combinations of occupancies, adjacencies, and dimensional parameters. The dollhouse’s mutability calls attention to the respective roles played by parties involved in BIM-aided design, and to the sometimes ludicrous possibilities in built space afforded by BIM.

Playing BIM requires participation side of the dollhouse and simulates to their work product. The designer rooms from the closet in the back; the front, simulates a DD drawing materials. Room suits range from nursery) to unconventional or absurd Porta Potties) for the designer

participation by two people on either simulates a designer’s relationship designer dresses and arranges back; the result, viewed from drawing set or client meeting from the conventional (library, absurd (treehouse, cluster of to choose from.

Elevations and plans produced in Revit are printed onto fabric and sewn into room suits. Assets are all downloaded from high-end home furnishing company websites, freely available in the hopes that BIM-using designers will spec their products. Here, however, their products can be enjoyed as toys without expectation of purchase.

Fall 2022 | Arch 101G | Debbie Chen

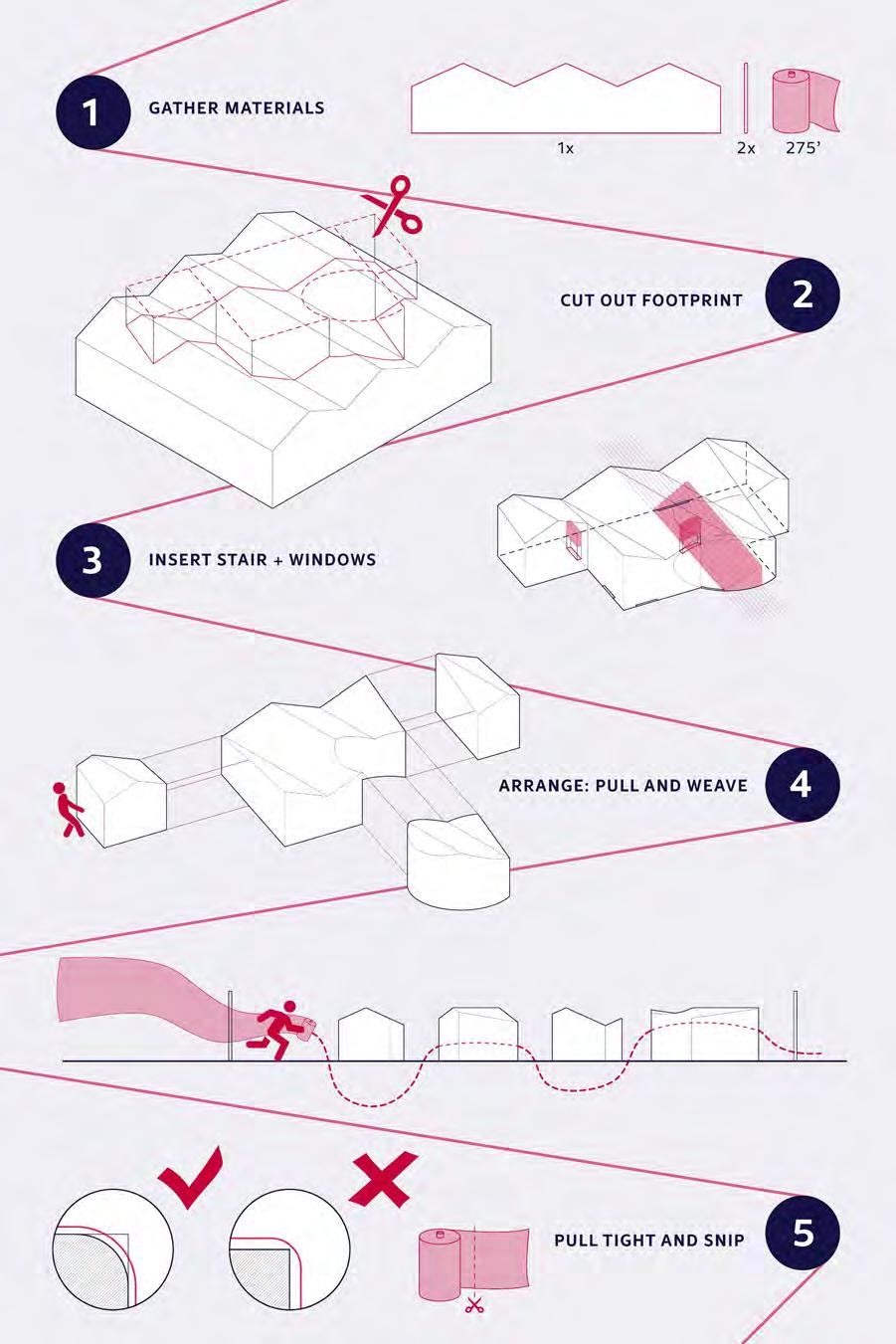

Bolt Building resists back- and front-side designations through its separation of program into distinct volumes. Fragments are joined together by a bolt of bright fabric tautly interwoven among the buildings, as well as a shared formal language at the roofline. The fabric’s tension carves radiused corners out of otherwise rectilinear forms. The fabric contributes a sense of togetherness that ultimately takes precedence over the forms’ separateness.

An assembly manual tells an imagined narrative of the pavilion’s construction, tailored to suit the occupants’ needs. The fabric lends a temporality and ritual aspect to the unifying move of weaving the buildings together. Tasked only with a few loose program requirements including an office and restroom, the project’s central aim is to provide flexible public assembly space. Volumes are interspersed with existing outdoor circulation paths connecting a nearby pedestrian bridge to the park beyond.

Spring 2023 | Arch 102G | Ryan McCaffrey

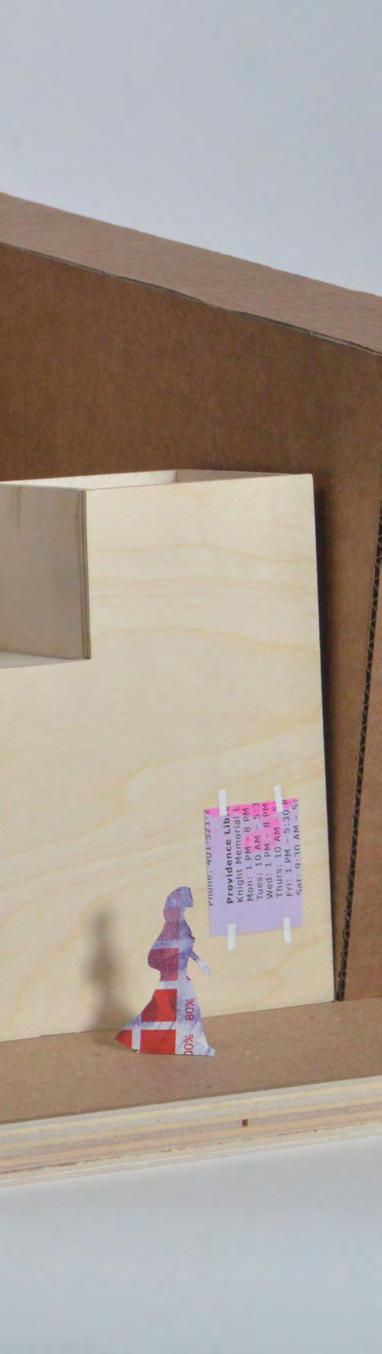

Wood joinery serves as loose inspiration for this public kiosk. Wide cut-aways at the canopy meet canted buildings below with a light touch. Slanted walls, a deviation from the adjacent buildings, welcome passers-by into the light-filled inner courtyard. Riso Depot provides in-house printing, storage, and sale of zines produced by members of the public, filling an important need in any community for information to be shared quickly and colorfully. Scale figure materials courtesy of RISD Riso studio scraps.

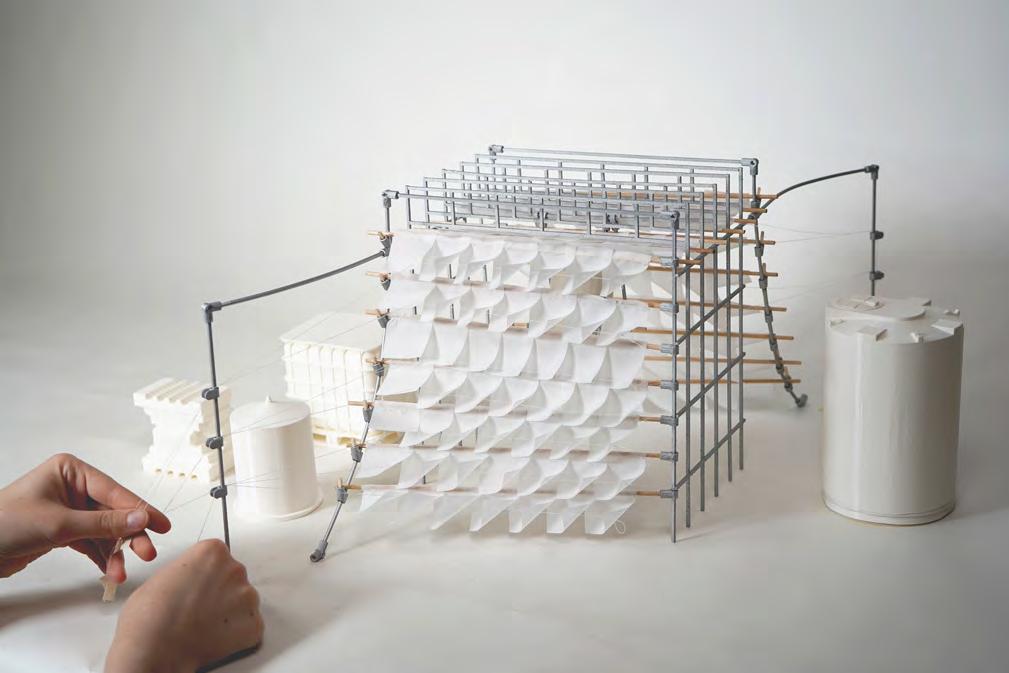

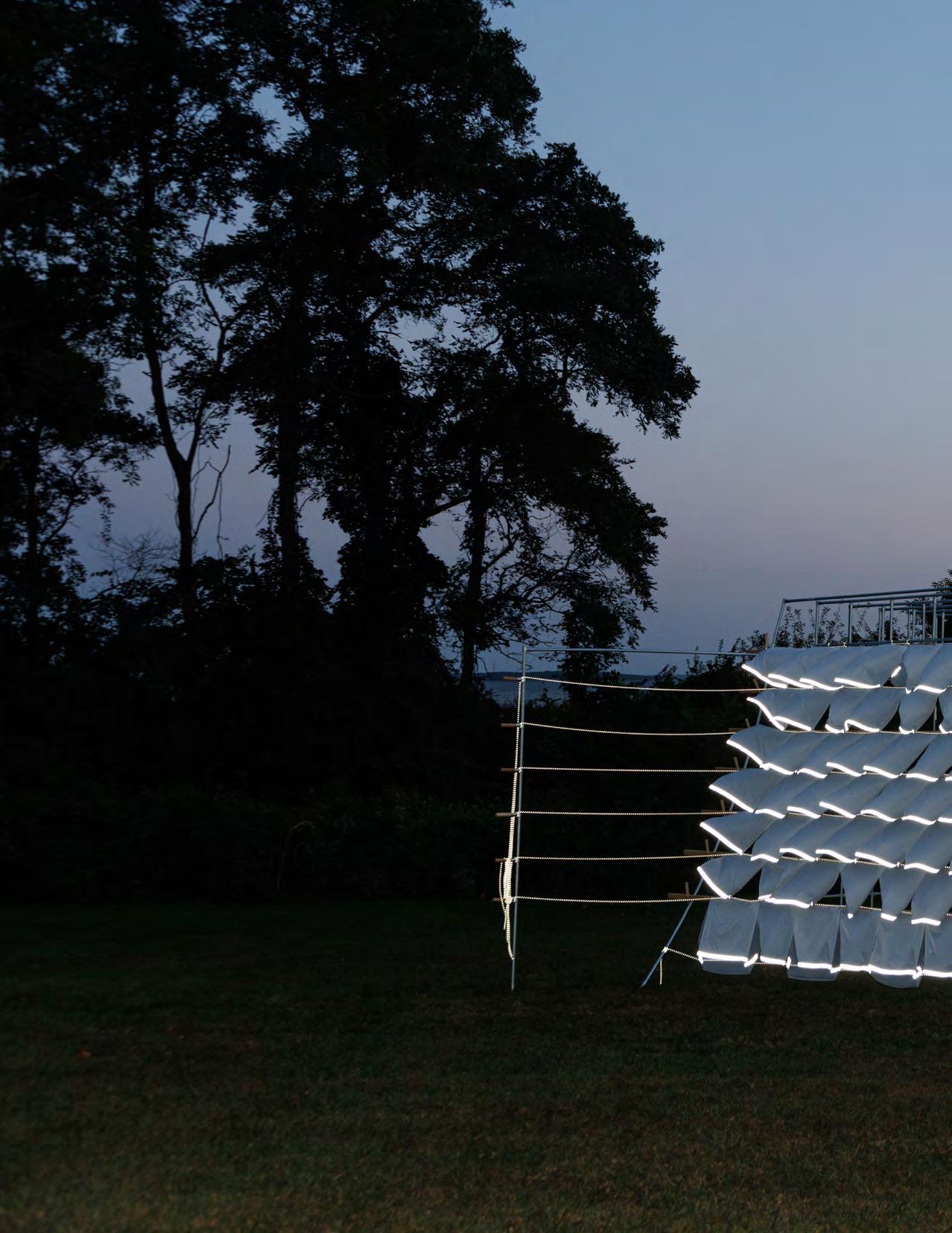

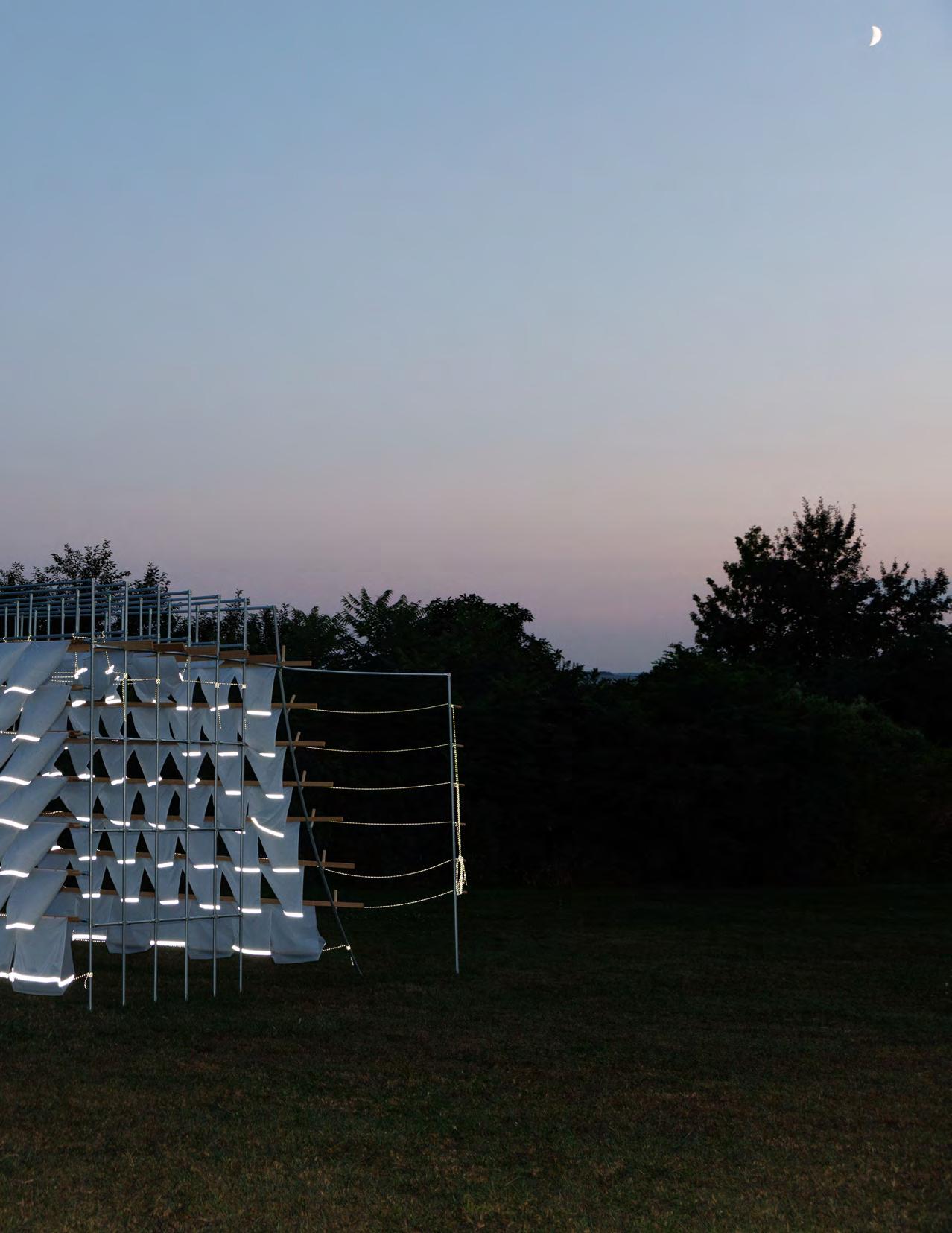

Assistant Professor Debbie Chen | Academic Year 2023-2024

Design Research Seed Fund Recipient

Completed in collaboration with graduate research assistants Aleza Epstein, Pateton Gonzales, and Isabelle Troutman. Project contributions include research, design development, shingle fabrication, and orthographic drawings.

The Design Research Seed Fund is a donor supported grant awarded annually to a faculty member in the Architecture Department for the creation of an exhibition, a public lecture, and a publication. The goal of the fund is to support the RISD Architecture community in the stimulation, production, and dissemination of creative practice with emphasis on the roles research and publication play in architectural discourse.

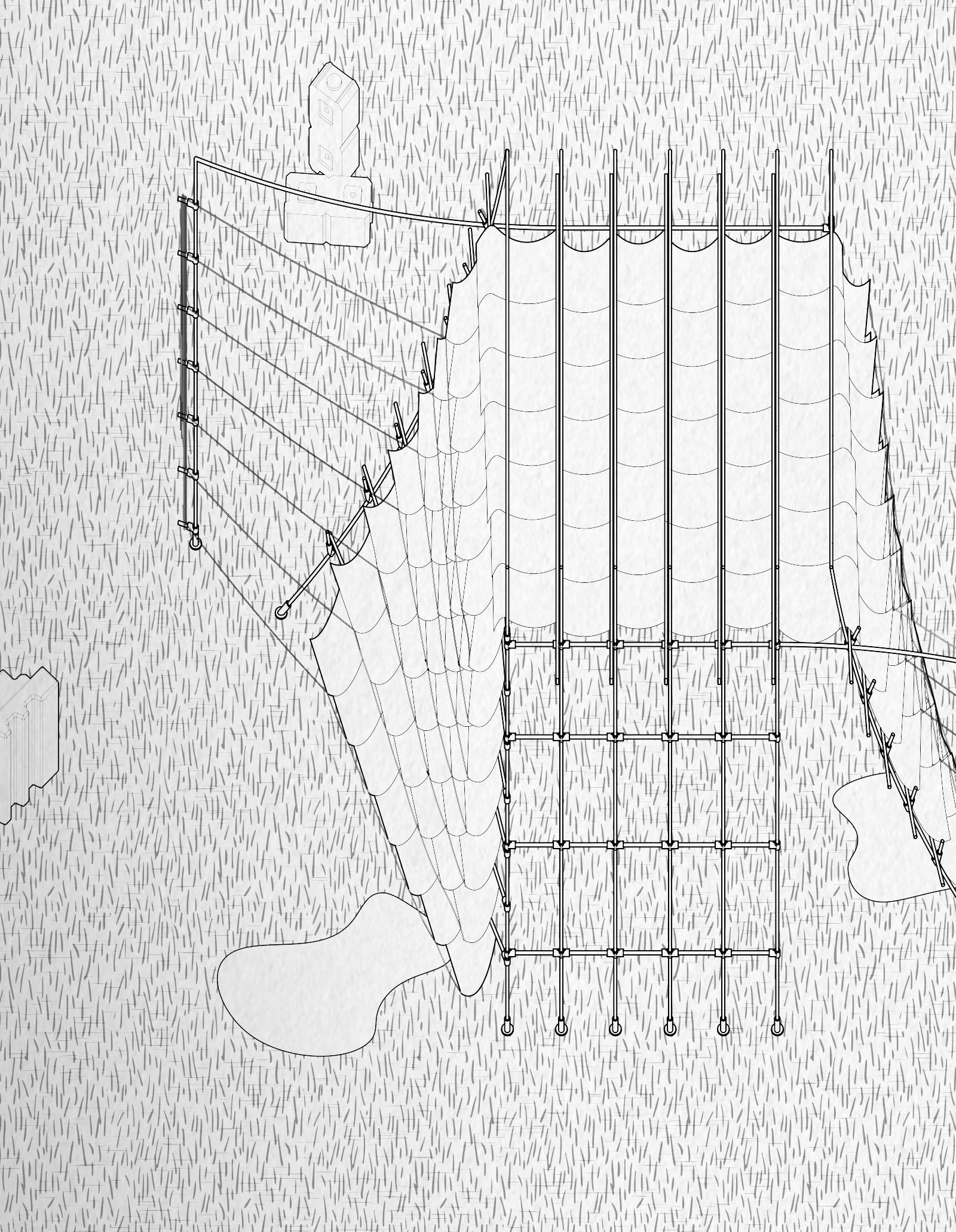

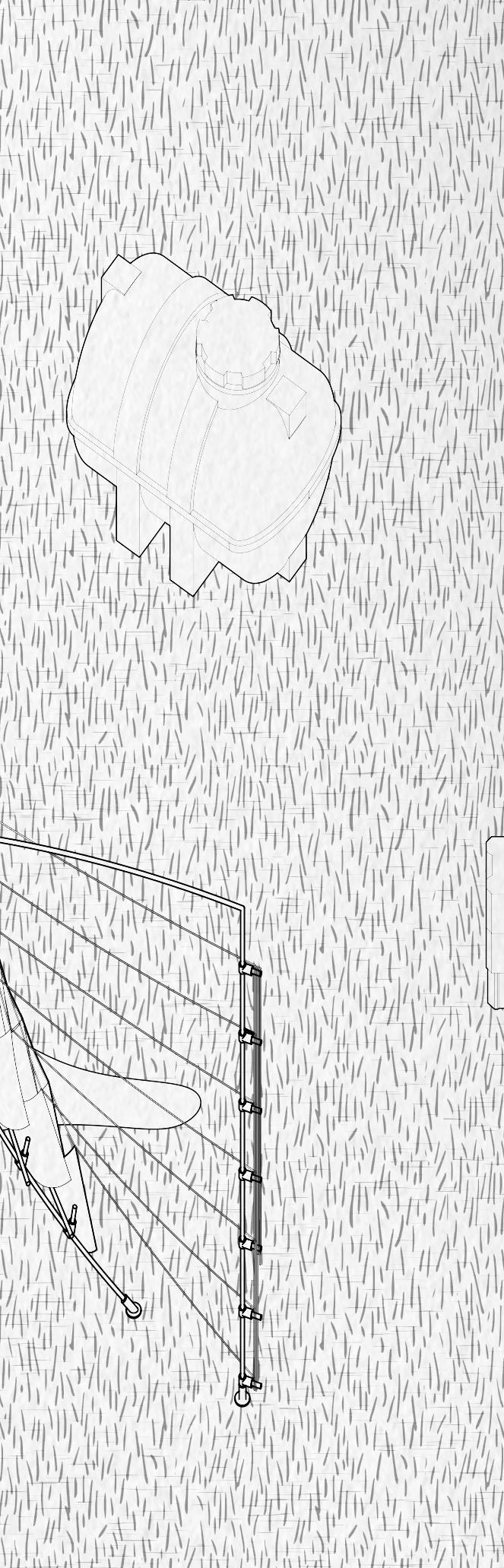

“What if our buildings ... engaged with the perpetual act of catching water? ... The project proposes a water-collecting structure with a soft, intermediary touch. Constructed at Tillinghast Place, the fabric-shingle pavilion is equally concerned with shedding moisture as it is with harvesting it. The shingles dance in the wind, directing rainwater into modest catchment pouches. Eschewing efficiency for delight, the water pavilion holds just enough water, for just long enough, a reminder that burden and bounty are held in balance.”

Project description written by Debbie Chen. Photography by Ella Baum.

Alexandra Croft | M.Arch ‘25 | RISD

details: fabric shingles and pouches

Soft shingles move in response to wind, alternating between concave and convex. The bright paracord can be tied in different patterns to control their movement, such as in preparation for stronger gusts of wind. When it rains, water is caught in pouches on the roof or flows through the shingles and into pouches along the bottom. These interventions require a human operator to interact closely with small, precious quantities of water, standing in contrast with the largely-invisible water infrastructure we are accustomed to.

As a research assistant, my roles included conducting research on water containers and infrastructure and iterating collaboratively on scale models of the proposal. Later during fabrication and installation, my roles included sewing shingles and creating drawings documenting the overall pavilion as well as details of the shingles’ movement. Project leadership and overall design of research and pavilion by Debbie Chen.