THE CULTURAL ARTIFACT OF PUNE DR

The Relationship Between

Maratha Culture and Shaniwar Wada

Written by Aleef Shaheel and Surabhi Sidhaye

Written by Aleef Shaheel and Surabhi Sidhaye

Maratha culture, originating from Maharashtra, India, embodies a legacy of warrior ethos, governance, and artistry, influencing Maharashtra’s culture, architecture, and social practices. Information on Maratha culture is limited to sources on Maratha heritage and historical architecture. We argue that primary sources such as Bakhars, often neglected, offer vital indigenous insight into the understating of Maratha culture. We also argue that the Bahkars help us further our understanding on how Marathi people influenced local Maratha Architecture and design based on the needs of the local indigenous people. In conclusion, understanding the indigenous history is crucial for understanding local culture and architecture.

According to Colomina and Wigleys book an artifact is something that has been designed by a human. According to the oxford dictionary, an artifact is something made by a human which has significant historical and cultural interest. Humans can learn about cultures and traditions associated with a particular artifact from the design of the artifact. As design is a form of thinking, and by understanding the design and the processes of designing an artifact humans could decipher the cultural and traditional stories that the artifacts would have to tell.1

India, with its deeprooted traditions and diverse cultural influences, offers a rich tapestry of architectural heritage that reflects the evolution of design and human expression. The Maratha culture, deeply rooted in Maharashtra,

India, reflects a legacy of warrior ethos, governance, and artistry. Established under Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj in the 17th century, the Marathas built strategic forts such as Raigad and Pratapgad, alongside architectural landmarks like Shaniwar Wada. Their rich traditions include folk dances, devotional music, and grand festivals like Ganesh Chaturthi. Even today, Maratha heritage influences Maharashtra’s culture, architecture, and social practices.2 During the late 17th to early 18th Century, the ministers of the time also known as Peshwas were very important figures that had an impact on the development on Maratha Culture during the rise of the Maharashtra Empire.3 One of the more notable Peshwa was BajiRao I who first built Shaniwar Wada.4

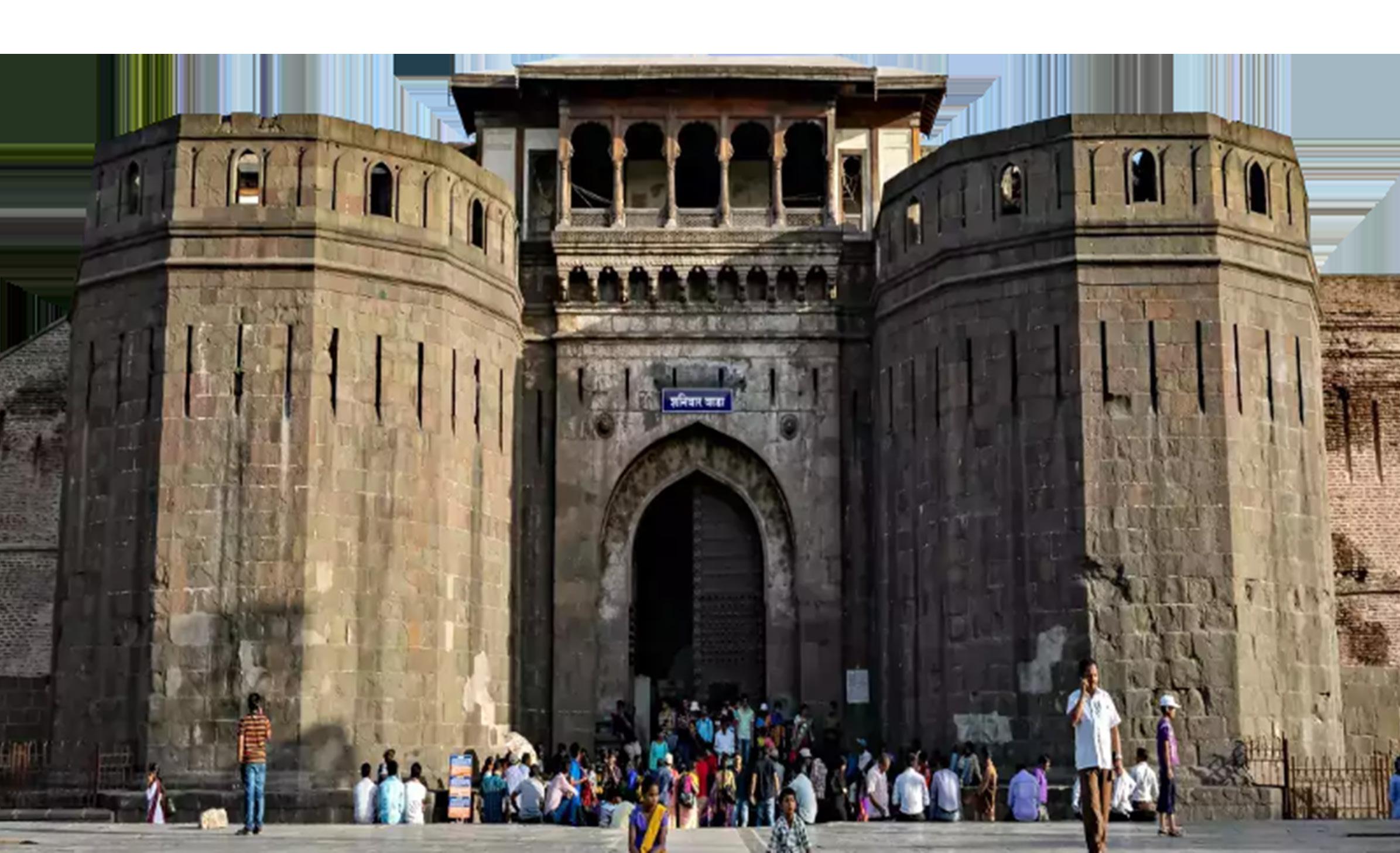

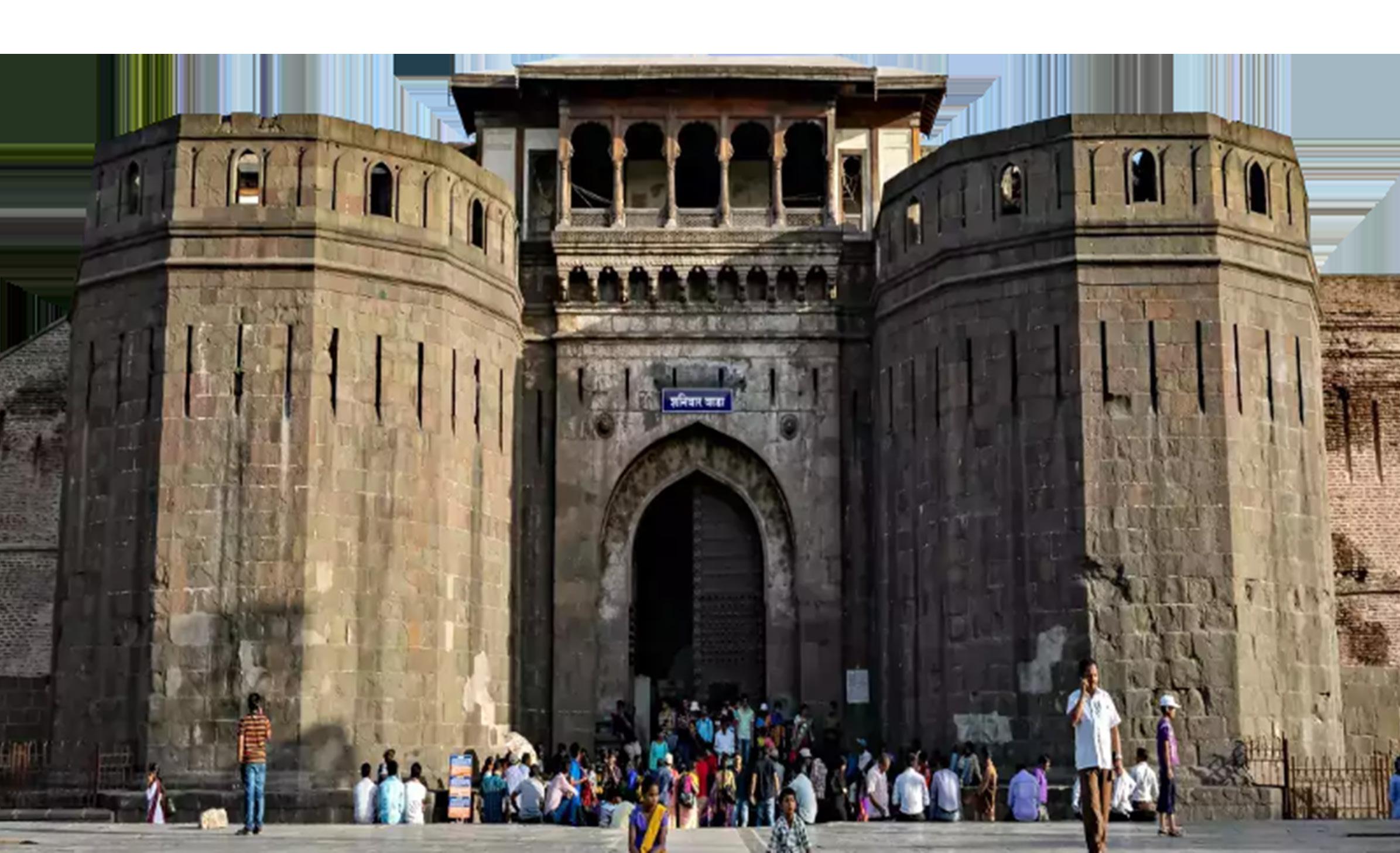

Shaniwar Wada, the grand fortress of the Peshwas in Pune, embodies a unique confluence of power, aesthetics, and regional identity. It serves as an ideal case study to understand how design and culture intertwine, illustrating how architecture not only provides shelter but also becomes a vessel for historical narratives, societal values, and collective memory.5 The stories and culture that surrounded Shaniwar Wada at that time had lasting impacts on Maratha culture. This essay will delve into the relationship between Maratha culture and local architecture, specifically Shaniwar Wada in Pune, and explore if and how different aspects of cultural traditions are reflected in the local architecture.

Though often neglected, Bakhars are vital for understanding Maratha culture as they offer indigenous insights into its history, values, and traditions. Bakhars are indigenous historical narratives written in Marathi that provide insider perspectives on Maratha history. Unlike colonial or Persian sources, they reflect local values, traditions, and beliefs. These texts highlight themes like honor, bravery, loyalty, and often blend history with folklore, offering insights into the cultural mindset of the Marathas.6 Since Bahkars are from a medieval period of Indian history and contain crucial information on Maratha culture, one could say that these Bakhars could be cultural artifacts as well. While not always factually precise,

they are valuable for understanding how the Marathas viewed themselves and their world, making them essential cultural documents.7 Our first argument will explore the fact that Bakhars are the only reliable source of information when it comes to understanding Marathi culture. We will be exploring the historical Martha cultural traditions to further our understanding to be able to tackle our next argument. The next argument will explore the relationship between Martha culture and the local architecture. Culture and design are closely connected, constantly influencing one another. Design reflects culture, and at the same time, culture helps us interpret design. We often understand or imagine past cultures through

their designs like the layout of ancient cities, traditional clothing, temple architecture, or motifs on pottery. These designs help us visualize the values, beliefs, and daily life of earlier societies. In this way, design becomes a window into the cultural past, it becomes a cultural artifact. Conversely, to truly understand a design; its form, purpose, and meaning, we need to know the culture it comes from. Cultural context explains why certain colours, symbols, or structures are used. Without that understanding, the design may lose its deeper significance. So, design helps us see and feel culture, while culture gives design its meaning and purpose. The two are always in dialogue, shaping and revealing each other.

The main field of research for this essay will be Indian cultural studies while focusing on the context of Maratha culture, and the relationship between Maratha culture and the local architecture, particularly Shaniwar Wada in Pune, India. When researching the Maratha culture and Shaniwar Wada, we found that there is a scarcity of information available on these topics. Therefore, analysing primary sources such as existing cultural practices, as well as historical texts written in Marathi would give us a better chance of understanding the Maratha culture. Books written in Marathi by local authors in Pune would also provide information for our research. Research written by English academics who have contributed to the field of South Asian

cultural studies would also be consulted. The main type of historical Marathi texts we will be analysing are the Bakhars. Bakhars are historical accounts written in Marathi prose by clerks and secretaries of Kings and Peshwas. These historical documents usually include information on everyday events that occurred. In a way Bakhars could be a cultural artifact. In the field of political history, the Bakhars are not a trusted source since Bakhar literature is known for its dramatic storytelling and sometimes biased historical accounts. However, they are an invaluable source of information when studying the cultural history of Maharashtra.8

The Bakhars we will be looking into are the Peshwanchi Bakhar, the Sabhasad Bakhar, and the Chitnis Bakhar.

The Peshwanchi Bakhar by Kashinath Narayan Sane is a historical Marathi chronicle that traces the rise and fall of the Peshwas, prime ministers of the Maratha Empire. It covers their administrative systems, military campaigns, and key events such as the Third Battle of Panipat (1761) and the Anglo-Maratha Wars, highlighting figures like Baji Rao I and Madhav Rao I. While dramatized, the text offers valuable cultural insights into the Peshwa era.9 The Sabhasad Bakhar and Chitnis Bakhar are early biographical accounts of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, offering insights into his leadership and

the formation of the Maratha Empire. Written by Krishnaji Anant Sabhasad and Malhar Ramrao Chitnis respectively, these chronicles reflect the Maratha perspective on key events. While not fully reliable for political history due to their dramatized style, they remain significant sources for understanding Maratha cultural narratives.10

Among Marathi sources, Shaniwar Wada by Prabhakar Bhave offers valuable insights into the architecture, history, and socio-political context of the Peshwa-era residence. Though not an academic, Bhave’s research drawn from archives, records, and

oral histories makes the book a key reference for understanding the urban fabric and cultural significance of Shaniwar Wada in heritage and architectural studies.11 Theoretical frameworks from scholars such as Anthony D. King, Adam Sharr, and Thomas Barrie reinforce the connection between architecture and cultural identity. In Changing South Asia: City and Culture, King emphasizes how the built environment, like art, reflects societal values and cultural interpretation, shaped by subconscious rules embedded within a culture.12

With the help of the Bakhars and other Marathi sources such as the book by Prabhakar Bhave on Shaniwar Wada, we begin to develop a clearer understanding of Maratha culture and heritage. We can get firsthand, indigenous information of these historical accounts. This will be our primary source of information to make our historical argument on the importance of Bakhars in understanding the Maratha culture. For our second, theoretical argument, we would be consulting the work of Anthony D. King and his theories on the relationship between culture and architecture. We will be applying these theories to analyse the relationship between Maratha cultural heritage and the cultural and historical site of Shaniwar Wada.

Our primary sources for this research will include three Bakhars which are the Peshwanchi Bakhar, the Sabhasad Bakhar, and the Chitnis Bakhar. We will also be using Anthony D. Kings essays which were published in the book Changing South Asia: city and culture, alongside the book written by Bhave titled Shaniwar Wada.

The Peshwanchi Bakhar written by Kashinath Narayan Sane is a historical Marathi chronicle that narrates the rise, administration, and fall of the Peshwas, the prime ministers of the Maratha Empire. It details their expansionist military campaigns, governance, and significant battles, including the Third Battle of Panipat (1761), which marked the beginning of their decline. The text highlights key figures like Baji Rao I, Balaji Baji Rao, and Madhav Rao I, showcasing their contributions and struggles. It also covers the AngloMaratha Wars that ultimately led to the fall of the Peshwa rule in 1818. The Sabhasad Bakhar and the Chitnis Bakhar are both biographical historical accounts of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj who led the Maratha Empire in the early 18th century. The Chitnis Bakhar was originally by Malhar Ramrao Chitnis, who

was a great grandson of Shivaji’s secretary ChitnisBalaji Avaji. The Sabhasad Bakhar was written by Krishnaji Anant Sabhasad by the request of Shivaji himself. All three of these Bahkars are valuable historical documents providing information on the Maratha perspective of events that occurred.

Prabhakar Bhave’s book on Shaniwarwada provides a detailed historical account, covering its architecture, political events, and cultural significance. He presents a chronological narrative of the fort’s role in Maratha governance, including key decisions and conflicts. His work includes maps and architectural insights, highlighting Maratha and Mughal influences. Bhave also explores Shaniwarwada’s legends, such as the tragic murder of Narayanrao Peshwa and ghostly folklore, which contribute to its mystique. These stories, along with its architectural grandeur, make Shaniwarwada an enduring cultural landmark. Despite being in ruins, Shaniwarwada remains a significant symbol of Maratha history. Bhave’s book preserves its legacy, offering readers a comprehensive understanding of its past. The fort continues to attract historians and tourists, standing as a testament to

Pune’s rich heritage. In the book Changing South Asia, King says ‘Like art, architecture and the physical and spatial form of cities presents images and symbols which are of considerable importance in helping people structure and maintain their interpretation of themselves, their daily life and their culture.’ He also adds to this by stating ‘the form of a building results in the application of a set of subconscious rules. These rules about buildings and spaces are part of a person’s culture’. Adam Sharr, a professor of architecture at Newcastle University adds value to King’s claims by saying ‘Buildings are evidence of the cultures that made them’, ‘a building records the forces at work in the societies where it was procured and inhabited over time’. Professor of architecture at NC State University, Thomas Barrie supports these statements as well by writing ‘as a predominant cultural artifact, architecture has often been tasked with embodying and articulating what a culture values most, and its material evidence is both a mirror and a lamp, reflecting and illuminating the culture that produced it.’ All three of these scholars agree that both culture and architecture have a significant relationship with each other.

Bakhars as mentioned earlier when discussing the sources, are the most important source of Information to understand Maratha culture as they are recognized by scholars and historians as valuable sources of information, particularly for understanding the socio-political landscape and historical narratives of Maharashtra. We will be investigating 2 Bakhars in detail to truly portray the value of the Bahkars when understating and learning about the Maratha culture. The two Bahkars we will be discussing are the Sabhasad Bakhar, and the Peshwanchi Bakhar. These texts are not just historical chronicles but also expressions of indigenous authorship.

Written by Marathi individuals closely associated with the courts, such as Krishnaji Anant Sabhasad who served directly under Chhatrapati

Rajaram these Bakhars are rooted in local perspectives and values. The identity of the authors lends the texts authenticity, offering insider viewpoints that affirm the Maratha worldview. This indigenous authorship resists colonial narratives and celebrates a distinctly Marathi cultural and political ethos, making the Bakhars essential for understanding identity formation in the region. The Bakhars, such as the Sabhasad Bakhar, and Peshwanchi Bakhar, are key primary sources illuminating the cultural values and social fabric of Maratha society. The Sabhasad Bakhar is written about Chhatrapati Shivaji, who built the Maratha Empire.

Written by Krishnaji Anant Sabhasad, a minister of Chhatrapati Rajaram at Jinji in 1694, the Bakhars explains certain events in Chhatrapati Shivajis life in detail, writing about

accounts of betrayal, murder, attacks, and sieges. These chronicles present a culture steeped in valor, devotion, and governance rooted in ethics. One dominant theme is the bhaktiinspired sense of justice and responsibility, especially seen in the life of Shivaji Maharaj. His emphasis on swarajya (self-rule) and dharma (righteousness) over mere conquest reflects a moral and cultural consciousness. Women’s honor and the welfare of peasants were central concerns. Shivaji is often praised in the Bakhars for not permitting the enslavement of enemy women or destruction of temples. His leadership reflects an enduring civic ethic, ‘The king often said, “Forts should not only serve for defense, but also be centers that fulfill the needs of the people”’.

The Bakhars also celebrate intelligence in warfare and diplomacy, such as the strategic use of forts and guerilla tactics, portraying Marathas as shrewd yet principled. The social structure emphasized kunbiwarrior ethics, community cohesion, and a blend of martial and agrarian values. These records emphasize leadership grounded in humility, religious tolerance, and visionary planning. From the Bakhars, we learn that Maratha culture was not only militarily resilient but also deeply philosophical, spiritual, and communityoriented elements still relevant for leadership and civic consciousness today. As these Bakhars are written by indigenous Marathi people about the day to day activities of the person they are writing about; in the case of these Bakhars the people the text is primarily about is

Chhatrapati Shivaji and the ministers or Peshwas, the text reflect a fairly accurate representation of the lifestyles and Maratha cultural traditions occurring at the time. However since the Bakhars are written by one individual it sometimes does includ a few subjective accounts including how Shivaji was blessed with a sword from the Goddess Bhawani. However, since religious practices are also a big contributing factor to the formation and development of a culture, even these subjective points teach us a lot about Maratha culture.

Krishnaji Anant Sabhasad also writes about Shivajis travels, the incomes and expenditures of the forts in Shivajis control at the time, and the roles of Maloji Rage, Shivajis Grandfather took on.

‘Maloji Raje constructed a reservoir on the hill to provide water for the people’.

A portion of the construction done at the time reflected the needs of the local people, ensuring their basic needs were being met and they were being protected from enemy threats. This leads us into our second argument where we argue that the Marathi people influenced the design of their architecture based on their needs.

The content within the Bakhars offers a rich tapestry of Maratha cultural life, extending beyond political events into realms of architecture, ritual, spirituality, and art. These texts describe how aesthetic choices in structures like Shaniwar Wada embodied the values and lifestyles of the Maratha people. From practical fortifications to ornamental flourishes, the descriptions mirror deep cultural consciousness embedded in everyday design. From the Peshwanchi Bakhar we understand that many fortresses built during the time of the Maratha Empire possessed an incredibly beautiful array of detailed design work and craftsmanship which showcased the artistic expressions of the Marathi people. This was seen in places such as Shaniwar Wada which had expertly crafted interiors with intricate ornamentation.

Firsthand indigenous records from the Peshwanchi Bakhar state,

‘during the reign of Shivaji Maharaj, the design of doors and palaces was exquisite, with decorations showcasing fine carvings’.

This line is paraphrased from Peshwanchi Bakhar, where detailed architectural elements of palaces and wadas (residences) are described as part of Maratha court grandeur. The text also says, ‘in the Peshwa court, chandeliers, zari embroidery, and colorful floral decorations were commonly seen’ and ‘The carved mirror work, shadows of chandeliers, and vibrant walls in the palace testified to the grandeur of the Peshwas’. The architectural ornamentation on these buildings help describe the stories of cultural expression within Maratha culture by reflecting the ideas of Maratha beliefs and values through the traditional forms of Maratha artistic expressions. These designs and intricate carvings also reflect the lives of those you carved them, the labourers, the builders. These architectural ornamentations on the Shaniwar Wada does not only represent the lives and culture of those Peshwas who lived there but it also represents the lives and work put in by the common wood carvers or stonemasons. These built structures, especially residential wadas and royal courts were deeply embedded in the daily lives of both rulers and commoners.

The Sabhasad Bakhar again complements this perspective by noting, ‘During Shivaji’s coronation, the palace was beautified; entrance gates were adorned with garlands and floral decorations’. The celebration of such events in aestheticized spaces underscores the fusion of political authority and symbolic tradition in Maratha architecture. The Sabhasad Bahkar also says ‘Maloji Raje constructed a reservoir on the hill to provide water for the people’. It also states ‘the construction on the fort was precise according to the terrain, ensuring convenient housing for the troops’. A large portion of the construction done at the time reflected the needs of the local people, ensuring their basic needs were being met

and they were being protected from enemy threats. The construction of the water reservoir was not just to provide fresh clean water for the local community but also for religious and cultural traditions. Water plays a large role in the cultural practices of Marathi people. Bodies of water are often associated with religious practices and festivals. Water also represents prosperity, fertility and spiritual purification and provides a sense of security during a time of many wars and battles. The forts even though they were primarily to protect the people inside from enemy threats, this was where many individuals including the peshwas lived their lives. Therefore, the design of these forts including Shaniwar Wada was equipped with large rooms for celebrations

and festivities, prayer room, and beautifully decorated gardens. Both the Peshwanchi Bakhar and The Sabhasad Bakhar validates our first argument which describes events where design, whether they were ornamentations in Shaniwar Wada or the need for a fort designed to the local context to house local troops, were influenced by the needs of the Marathi people. Thus, both the Peshwanchi Bakhar and the Sabhasad Bakhar validate our key arguments demonstrating how Maratha design decisions, whether in everyday fort architecture or royal ornamentation, were shaped by people’s cultural values, sociopolitical needs, and spiritual beliefs.

Moving forward, further research should integrate indigenous sources like the Bakhars with contemporary architectural analysis to form a more inclusive historical narrative. By comparing insights from local records with Western scholarship, we can construct a richer understanding of regional architecture. There is also potential to explore how the values

Our exploration of Maratha culture and architecture, particularly through Peshwanchi Bakhar and Sabhasad Bakhar, reveals that Maratha design was deeply rooted in indigenous values, practical needs, and cultural expression. Structures like Shaniwar Wada showcase intricate ornamentation and thoughtful design, not only reflecting the grandeur of the Peshwa court but also the skill and contributions of

embedded in historical Maratha design sustainability, contextual responsiveness, and community orientation can inform present-day architectural practice. A deeper engagement with local archives and oral histories will ensure that future architectural discourse remains grounded in cultural authenticity and regional identity.

local artisans. The texts illustrate how architecture responded to the needs of the Marathi people whether through finely carved interiors or the practical construction of forts suited to local terrain. These findings highlight that Maratha architecture was not merely royal or decorative but embodied a broader social and functional consciousness.

1. B. Colomina, & M. Wigley, Are We Human? Notes on an archaeology of design (Lars Muller Publishers, 2016), 23-29

2. ShaniwarWada information in Marathi, https://infomarathi07.com/shaniwar-wadainformation-in-marathi/.

3. Peshwa. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/peshwa.

4. Amaresh Datta, ed., The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Volume One (A to Devo) (New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1987)

5. P. Bhave, Shaniwarwada, (Sarita Publications, 1979)

6. Peshwyanchi Bakhar

7. Datta, 1987

8. Colomina & Wigley, 2016

9. Peshwyanchi Bakhar

10. M.A. Surendranath Sen. Siva Chhatrapati : being a translation of Sabhasad Bakhar with extracts from Chitnis and Sivadigvijya, with notes. (University of Calcutta, 1920)

11. Bhave, 1979

12. Anthony D. King, “Art. Architecture and Social Change,” in Changing South Asia : city and culture, ed. by Ballhatchet, K., & Taylor, D. (University of London, 1984)

Primary Sources

• Bhave, P., Shaniwarwada, (Sarita Publications, 1979)

• Peshwyanchi Bakhar

• Sabhasad Bakhar (Original Indigenous text)

• Surendranath Sen. M.A. Siva Chhatrapati : being a translation of Sabhasad Bakhar with extracts from Chitnis and Sivadigvijya, with notes. (University of Calcutta, 1920)

Secondary Sources

• Barrie, Tom, Julio C. Bermudez, and Phillip Tabb. Architecture, Culture, and Spirituality. 1st ed. Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315567778

• Colomina, Beatriz, and Mark Wigley. Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Lars Muller Publishers, 2016, 23-29.

• Datta, Amaresh, ed. The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Volume One (A to Devo). New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1987.

• Ghanekar, P.K. Shaniwar Wada. Snehal Publication, 2015.

• King, A.D., “Art. Architecture and Social Change,” in Changing South Asia : city and culture, ed. by Ballhatchet, K., & Taylor, D. (University of London, 1984)

• ShaniwarWada: ‘Curse’ of the Peshwas. https://www.peepultree.world/ livehistoryindia/story/monuments/shaniwarwada

• ShaniwarWada information in Marathi. https://infomarathi07.com/shaniwar-wadainformation-in-marathi/

• Sharr, Adam. Reading Architecture and Culture: Researching Buildings, Spaces, and Documents. 1st ed. Routledge, 2012. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203721193

DESIGNING