GREAT ExPECTATIONS

OIL & GAS BUILDING MOMENTUM

•

• Best attachment lengths

• Best transpor tability

• Best ser viceability

• Best accessibility with flat deck

• Best distributor and factor y support

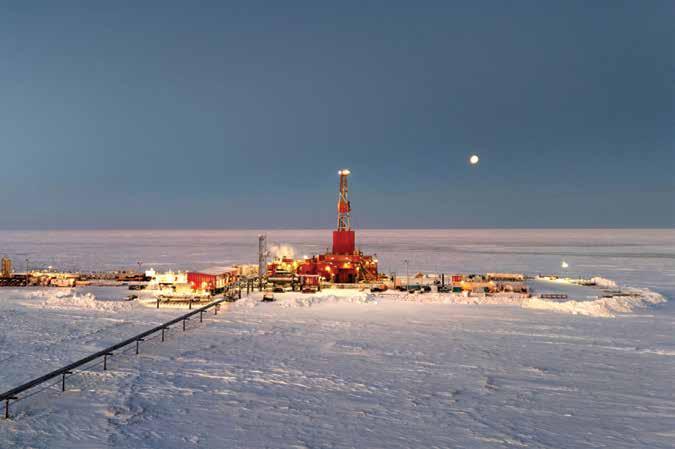

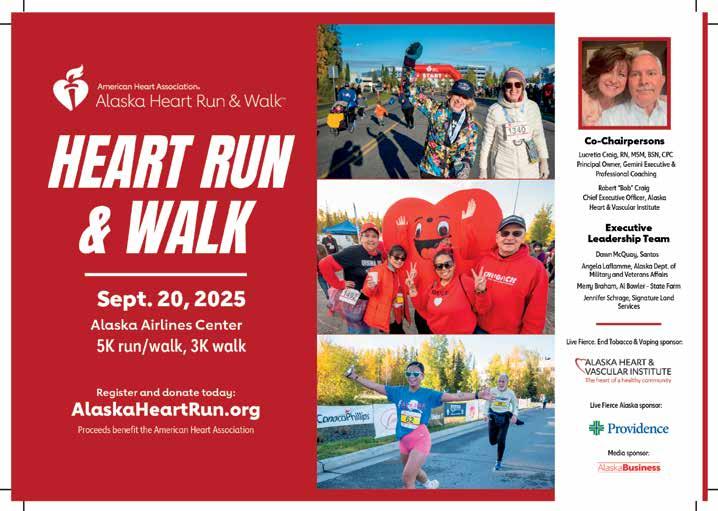

Unlocking More Oil and Jobs on State Lands

At Santos, we are proud to develop the world-class Pikka Project on Alaska’s State Lands - creating more revenue and more jobs for Alaskans.

Pikka is unlocking 400 million barrels of Alaska’s oil. It has already created thousands of construction jobs and will provide hundreds of permanent jobs.

This is just the beginning. By next year, 80,000 barrels per day will be added to the Trans Alaska Pipeline System. Santos is building the future of energy in Alaska.

Tracy Barbour

Kvapil

Jamey Bradbury

“Whenever we have a need — whether it’s lending or payroll — First National knows who we are, they solve our challenge, and we get back to running our business.”

– Tim Schrage

Tim and Jen Schrage started Signature Land Services with a dirt lot and a big vision. With customized solutions from First National, they’ve expanded to a larger, more secure facility – equipped for growth and built to last. Every step of the way, their banker delivered more than financing –First National provided unmatched expertise and a relationship the Schrages could count on.

CONTENTS

SPECIAL SECTION: OIL & GAS

64 PUMPING UP THE VOLUME

New North Slope production already boosting TAPS throughput

By Rindi White

72 THE LONG GAME

Multiple rolls of the dice for Alaska’s next discoveries

By Alexandra Kay

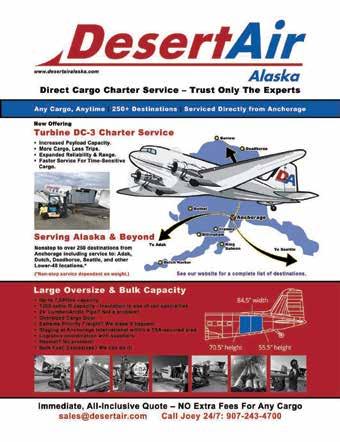

78 CONNECTING THE ARCTIC

Perseverance, creativity, and teamwork to supply the Slope By

Vanessa Orr

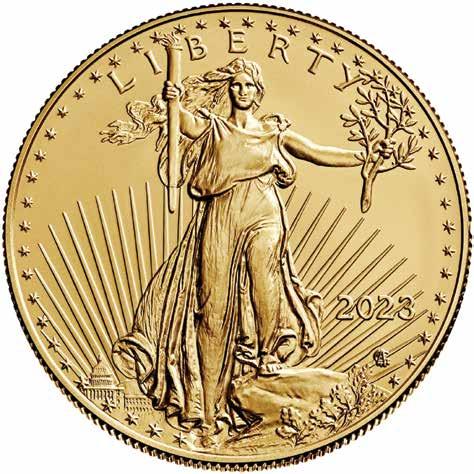

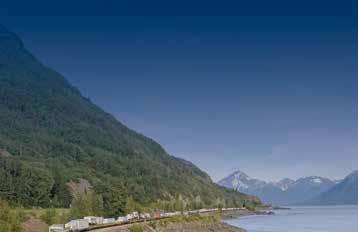

ABOUT THE COVER

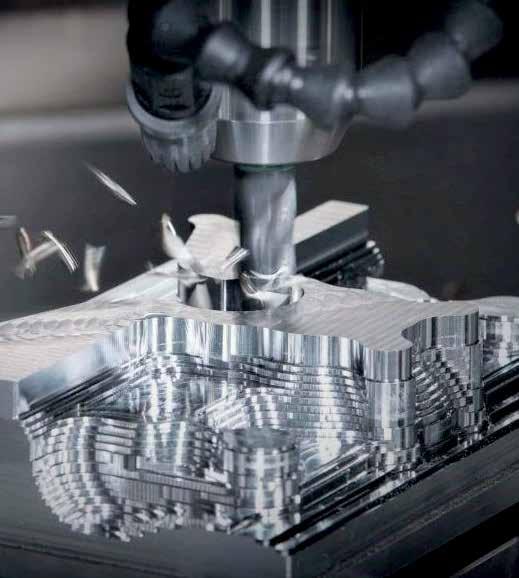

86 EQUIPPED TO SERVE

Parts and support for industrial customers By

Terri Marshall

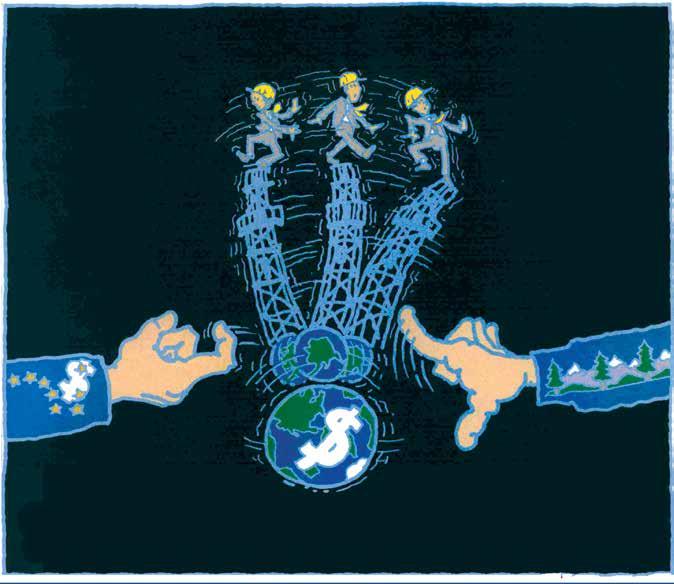

The cover of the February 2002 issue of Alaska Business featured a photo of the Alpine Field Module F-1, which heated crude oil to separate water and gas before the oil began its journey through the Trans Alaska Pipeline System. The image by photographer Aaron Weaver was in many ways a new view of an Alaska oil field, so it was reprinted repeatedly in other publications after it graced our cover. This month, we are featuring another Aaron Weaver photo from that 2001 photoshoot, with a drill rig envisioned just on the horizon. Alaska still benefits from its legacy fields, which set the foundation for oil and gas development today and into the future.

Photograph by Aaron Weaver

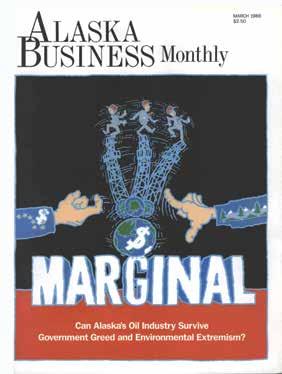

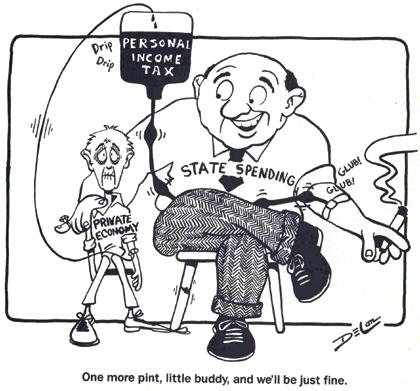

90 BOOMS & BUSTS

The ‘80s crash, the 2014 crisis, and what comes next By Tasha Anderson

Photos by Red Photography

FROM THE EDITOR

Alaska has fundamentally changed since oil was discovered at Prudhoe Bay, and, in line with the oil industry’s overwhelming influence, it was an essential player in this magazine’s origin story.

The masthead in our inaugural January 1985 issue listed two editorial employees: publisher Robert F. Dixon and editor Paul Laird. In that issue, the two co-wrote an introductory letter, but Laird didn’t start a monthly Letter from the Editor until November of 1987, at which point his title had shifted to executive editor.

In that first Letter from the Editor, Laird explained that he had a friend who worked for Sohio, officially titled the Standard Oil Company (Ohio), in Alaska, and since Laird was in search of a travel destination that was both “bizarre” and housed someone he knew so he could rely on them for accommodations, Alaska fit the bill.

Laird knew little about the state except that it was supposed to be beautiful and “it was a darned shame they had to build that oil pipeline and destroy the wilderness up here. I only knew that because the Wilderness Society magazine tucked in my carry-on said so.”

He was right about Alaska’s stunning scenery; Laird was “awestruck” by the Alaska Range and Chugach Mountains, by his travels to Portage and Valdez. The pipeline, however, was a let-down.

Laird wrote, “Maybe I was expecting a ruthless metal behemoth gnawing its way through what once was wilderness. A mile-wide swath on each side, carcasses of wild animals floating in oil seeps. Like many others I’ve talked to since then, I guess I was expecting something more—something proportional to the furor it had caused. Anything but a rather indistinct 48inch steel pipe that’s mostly buried and almost indistinguishable from a distance where it isn’t.”

Laird’s letter describes how the trip “altered his framework” and set him on a path to call Alaska his home and learn more about not just the oil and gas industry but the many major industries that have built Alaska. “Lots of myths upon which I’d based my philosophy of life up to that point have evaporated in the months, the years since then.”

Now that I occupy Laird’s position, I can relate to how learning more about Alaska’s economy is eye-opening, even though I was raised here, surrounded by Alaska’s glory. Despite my thirteen years researching and writing about Alaska, there’s still so much more for me to learn. What I do know is our state is rich in resources—not the least of which are stories of exceptional Alaskans doing fascinating things.

Tasha Anderson

Editor,

VOLUME 41, #8

EDITORIAL

Tasha Anderson, Managing Editor

Scott Rhode, Editor/Staff Writer

Rindi White, Associate Editor

Emily Olsen, Editorial Assistant

PRODUCTION

Monica Sterchi-Lowman, Art Director

Fulvia Caldei Lowe, Production Manager

Patricia Morales, Web Manager

BUSINESS

Billie Martin, President

Jason Martin, VP & General Manager

James Barnhill, Accounting Manager

SALES

Charles Bell, VP Sales & Marketing 907-257-2909 | cbell@akbizmag.com

Chelsea Diggs, Account Manager 907.257.2917 | chelsea@akbizmag.com

Tiffany Whited, Marketing & Sales Specialist 907-257-2910 | tiffany@akbizmag.com

CONTACT

akbizmag.com | (907) 276-4373

Press releases: press@akbizmag.com

Billing: billing@akbizmag.com

Subscriptions: circulation@akbizmag.com

alaska-business-monthly

akbizmag

AKBusinessMonth

AKBusinessMonth

Alaska Business (ISSN 8756-4092) is published monthly by Alaska Business Publishing Co., Inc. 501 W. Northern Lights Boulevard, Suite 100, Anchorage, Alaska 99503-2577; Telephone: (907) 276-4373. © 2025 Alaska Business Publishing Co. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Alaska Business accepts no responsibility for unsolicited materials; they will not be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self addressed envelope. One-year subscription is $39.95 and includes twelve issues (print + digital) and the annual Power List. Single issues of the Power List are $15 each. Single issues of Alaska Business are $4.99 each; $5.99 for the July & October issues. Send subscription orders and address changes to circulation@akbizmag.com. To order back issues ($9.99 each including postage) visit simplecirc.com/back_issues/alaska-business.

Economic Impact of the Nonprofit Sector

Leveraging public and private resources

By Tracy Barbour

Nonprofits play a vital role in Alaska's economy, serving as employers, revenue generators, and providers of essential services. These insights are detailed in The Foraker Group’s latest report, Alaska’s Nonprofit Sector: Generating Economic Impact. This is the seventh such study released by The Foraker Group, a 501(c)(3) organization that strengthens Alaska's nonprofit and tribal organizations through educational opportunities, shared services, organizational development, public policy, and fiscal sponsorship.

Laurie Wolf, Foraker Group president and CEO, views nonprofits as “the backbone” of Alaska’s economy. Their contributions often go unnoticed, yet their impact is pervasive. “You can't go through your day in rural or urban Alaska without engaging with a nonprofit. Even when

you don't know it; it's just part of your everyday life,” Wolf explains.

Although most people don’t think of nonprofits as economic powerhouses, they are an important “safety net,” according to the Foraker Group report. “No industry in Alaska can prosper without the nonprofit sector, and every dollar invested in the sector, regardless of the source, results in lower government costs in the long run,” the report emphasizes. “We provide both a financial and social return on investment by leveraging public and private resources.”

oil and gas industries. And they offer a wide variety of essential services like early childcare, housing, food security, and firefighting. As highlighted in the report, nearly forty communities depend on stand-alone nonprofit volunteer fire departments; about thirty nonprofit libraries operate across the state; and 75 percent of Alaskans receive their electricity from a nonprofit cooperative utility.

Nonprofits in Alaska engage in various sectors, including the healthcare, utilities, fisheries, and

And nonprofits help other nonprofits. Take, for instance, the Anchorage-based Rasmuson Foundation. The private family foundation invested approximately $23 million in fifty-five communities in 2024, according to President and CEO Gretchen Guess. Since its inception seventy years ago, Rasmuson Foundation has awarded more than $550 million in grants. “We have now

Laurie Wolf

The Foraker Group

given away, in grants, more than Jenny and Elmer, our two founders, put into the foundation,” Guess says.

Guess enjoys collaborating with other nonprofits, communities, tribes, and other entities to provide solutions throughout the state. “We feel blessed by the work we get to do, supporting people doing great work on the ground,” she says. “I think all Alaskans know that we wouldn't be functioning as a community without our nonprofits.”

Key Findings

Released in December 2024 and sponsored by Credit Union 1, The Foraker Group’s economic impact report shares a wealth of information about how nonprofits participate in and bolster the state’s economy. The report is based on extensive research—including some hardto-find data—conducted through various state and federal sources. Its goal is to better inform policy makers and the private sector about Alaska’s nonprofit sector.

In the report, The Foraker Group addresses what it considers misconceptions about nonprofits. For example, when most Alaskans think about nonprofits, they focus on the 501(c)(3) or charitable organizations with missions that improve the community and people’s daily lives. And while 80 percent of the state’s nonprofits are charitable— including religious congregations, human services, education, and healthcare organizations—many

“No industry in Alaska can prosper without the nonprofit sector, and every dollar invested in the sector, regardless of the source, results in lower government costs in the long run.”

LET’S GET DOWN TO BUSINESS

• Bill Pay to automate regular payments

• Merchant Services to accept debit or credit cards

• Positive Pay to help prevent check fraud

• Business Remote Deposit to save you time

Call 877-646-6670 or visit globalcu.org/business to talk to a specialist today!

Insured by NCUA

Gretchen Guess Rasmuson Foundation

Alaska’s Nonprofit Sector: Generating Economic Impac t, The Foraker Group

A rendering of the kitchen incubator planned for the Mountain View neighborhood, where earlystage food businesses can access preparation space and affordable storage. Construction is anticipated in 2027.

other types of nonprofits contribute significantly to the economy.

“It is also true that no sector is either all nonprofit, for-profit, or government,” says Wolf. “It takes all three sectors to make our economy work.”

The report highlights nonprofits’ contributions to the economy on their own and through support for the state’s major for-profit industries, stating, “From associations engaging in the policy-making process to economic development agencies promoting jobs and workforce development, nonprofits contribute to the vitality of commercial enterprises.”

The nonprofit Anchorage Community Land Trust (ACLT), for example, prepares entrepreneurs and small business owners to become leaders, wealth builders, advocates, and employers in their own neighborhoods. ACLT’s flagship Set Up Shop program provides training, technical assistance, lending, and real estate support to business

owners in targeted low-income neighborhoods of Anchorage. “We work intentionally with people and in neighborhoods that have been traditionally underestimated and overlooked,” says CEO Kirk Rose.

As an extension of Set Up Shop, ACLT recently received a $300,000 grant from KeyBank to build a new commercial kitchen incubator in the Mountain View neighborhood next year. The project—which Rose has spent seven years researching— will provide affordable storage and preparation space for early-stage food businesses. The kitchen, he says, will offer a safe space where caterers, food truck owners, and others can learn and “grow into the next step.”

will provide a shared space for food businesses to grow,” says Lori McCaffrey, KeyBank President, Alaska Market and Commercial Banking Sales Leader, who also serves on ACLT’s board. “In addition, it will improve food security by providing more access to more locally grown and packaged goods. At KeyBank, our mission is to help our neighbors and community thrive, and ACLT is accomplishing that through meaningful projects like this.”

Other Interesting Insights

A longtime supporter of ACLT, KeyBank is enthusiastic about the development of the commercial kitchen incubator. “This project

The economic impact report also highlights the role of Alaska Native tribes as nonprofits. Although tribes are sovereign governments, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) allows them to create separate entities that qualify for nonprofit status, according to the report. At one point, all Alaska tribes held this dual status, but as of 2023, only nine were registered with the IRS as nonprofits. Regardless, these entities serve missions like healthcare, economic

Anchorage Community Land Trust

Kirk Rose Anchorage Community Land Trust

and community development, local search and rescue, education, support for Indigenous ways of life and culture, and advocacy for traditional food harvesting and sovereign rights. “Tribes and Alaska Native-serving nonprofits and coalitions play a vital role in the well-being, advancement, and sovereignty of Alaska’s Indigenous communities,” the report notes.

Regarding volunteering, Alaska’s rate exceeds the US average and ranks fifth in the nation, according to the report. Donations to the Permanent Fund Dividend charitable contributions campaign, Pick.Click. Give.—for which The Foraker Group wrote the original legislation— have increased about 4 percent annually over the past decade. Wolf isn’t surprised. She says, “We know that when Alaskans are given an opportunity to support the things they love—and if we make it easy for them—they will.”

In addition, Wolf points out that Alaska’s volunteerism rates are high, in part, because most nonprofits have little or no staff; volunteers operate and govern most of their organizations. Seventy-nine percent of Alaska nonprofits are run solely by volunteers. In Alaska, volunteers donate a cumulative 5 million hours annually, at an estimated economic benefit of $9.5 million.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered changes among employees and volunteers. “We saw the Great Resignation and then the Great Reshuffle in our workforce,” Wolf says. “And now we are seeing that in our board rooms; people are really thinking about what's most

“As business and philanthropic interests increasingly look for climate-aware, socially resonant investments, ASLC represents a model where public trust and economic value reinforce each other.”

John Fraser, Director of Mission Impact, A laska SeaLife Center

The Alaska School Activities Association is a statewide nonprofit organization established to direct, develop and support Alaska's high school interscholastic sports, academic and fine arts activities. ASAA has over 200 member schools, over 35,000 student participants, and manages 52 championships!

ASAA can put the spotlight on your business in front of 100,000+ Alaskans at dozens of amazing high school championship events!

If you would like to join the team and support students throughout Alaska during our 2025-26 interscholastic championships, please scan the QR code to contact Colin McDonald, Director of Marketing.

“We feel blessed by the work we get to do, supporting people doing great work on the ground… I think all Alaskans know that we wouldn't be functioning as a community without our nonprofits.”

Gretchen Guess President and CEO Rasmuson Foundation

important in their lives and how they want to spend their free time. And so we are starting to see a lot of shifting in our board spaces. And I encourage our nonprofits to engage their existing teams to create meaningful opportunities for new and seasoned people to volunteer.’”

Additionally, nonprofits continue to be a “steadying force” that amasses “reliable revenue” for Alaska’s economy. Alaska’s nonprofits accounted for $9.4 billion in revenue in 2023, an increase of 19 percent from 2020. The greatest increase was in 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(1) organizations. “Organizations with a 501(c)(4) designation experienced a 20 percent decrease in revenues from 2020, likely a result of the conclusion of federal pandemic relief spending,” the report notes.

Impact on Employment and Beyond

Nonprofit organizations are consistently a substantial source of jobs. In 2023, there were more than 5,600 tax-filing nonprofits in Alaska, a number that has remained stable over the past decade. Roughly one fourth of those, or 1,211, had employees in 2023. “It’s a small number of organizations employing a lot of people, and healthcare, for sure, is driving that conversation,” Wolf says. The largest non-government employer in the state is Providence Alaska with more than 5,000 workers on its payroll, and Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, Southcentral Foundation, and Foundation Health Partners in Fairbanks each have well over 1,500.

According to the report, nonprofits directly employ 35,302 Alaskans. Counting indirect and induced effects, nonprofits are responsible for sustaining 54,942 jobs in the state through the purchase of goods and services and employee spending. These jobs generate $3.8 billion in income, which impacts local communities.

In Alaska’s regional economies, nonprofits often play a crucial role. They employ about 14 percent of the non-government workforce and 10 percent of the total workforce, compared to 10 percent nationwide. In rural areas, mission-based organizations can account for up to 40 percent of direct employment.

In Seward, for instance, the nonprofit Alaska SeaLife Center (ASLC) has a profound impact. It’s the only institution in Alaska that combines public visitation with federally authorized marine mammal response and long-term scientific research, according to ASLC President and CEO Wei Ying Wong. “While not atypical among major coastal zoos and aquariums, it is the sole provider of these types of action for Alaskan species globally, and the only institution that can provide support for animals like walrus, northern sea otters, ice seals, and the unique support needs of Alaska’s birds that require seawater as part of their recovery,” Wong says.

ASLC employs eighty-five full-time, year-round staff, plus twenty-four seasonal workers. ASLC paid staff

Wei Ying Wong Alaska SeaLife Center

$5,971,196 in total wages in the fiscal year ending September 30, 2023, the most recent IRS report on file. According to revised figures for 2024, ASLC estimates its financial impact in five key areas:

x Direct annual ASLC spending to the City of Seward or Seward businesses: $2 million

x Direct annual ASLC salaries into Seward: $5.7 million

x Wage value of indirect jobs created by count of primary visitors to Seward: $4.7 million

x Wage value of induced jobs from ASLC salaries in Seward: $2.4 million

x Visitor spending (day/overnight) for those who came primarily to Seward for ASLC: $3.3 million

For the City of Seward, a gateway to Kenai Fjords National Park and other tourists attractions, the estimated total primary visitor impact was $18.1 million in 2024. Secondary visitors to ASLC—where ASLC wasn’t their primary reason for visiting—spent an estimated $28 million in Seward.

The total ASLC-related economic impact on Seward for 2024 was $46.1 million. Additional benefits to Anchorage ($2.8 million), elsewhere in Alaska ($0.5 million), and outof-state travelers ($2.5 million) bring the total economic impact to Alaska to $51.9 million.

ASLC is a powerful case study in how mission-driven institutions can deliver layered economic and social returns, according to ASLC’s Director of Mission Impact John Fraser. “Our impact measures demonstrate that the Alaska SeaLife Center is not just an aquarium—it’s a hybrid institution

SOREL PATAGONIA UGG BIRKENSTOCK DANSKO

that merges tourism, research, education, and disaster response,” says Fraser, who has led national research on the social value of zoos and aquariums. “It generates positive economic impact beyond industry standards while building longterm resilience for Alaska’s coastal economies through its voice, role modeling, and extraordinary media reach. As business and philanthropic interests increasingly look for climateaware, socially resonant investments, ASLC represents a model where public trust and economic value reinforce each other.”

Fickle Finger of Federal Funds

Nonprofits rely on multiple funding sources to achieve their mission, including earned income, private donations, and public funding. Collaboration and partnerships with other organizations are also critical to their endeavors.

The ASLC, for instance, collaborates with UAF and funds research through government agencies. Over the years, it has received long-term funding from the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Science Foundation, and US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The agencies recognize that ASLC aligns with federal priorities, including studies of animal collections specifically held in its facility to support research. “Our wildlife response

“From associations engaging in the policymaking process to economic development agencies promoting jobs and workforce development, nonprofits contribute to the vitality of commercial enterprises.”

Alaska’ s Nonprofit Sector: Genera ting Economic Impact The Foraker Group

team deploys across the Alaska coastline to federally prioritized animal strandings, bringing live animals with a chance of survival into our facility for rehabilitation, and sending our veterinarians as needed to support necropsies to explain loss of animal life,” Wong says. “We plan to continue to do this important work and continue to fundraise to match federal funding or replace what may be lost as federal budget priorities seem to be

shifting away from our work and predictiv e science modeling.”

The Foraker Group report notes that $42 billion in federal grants and contracts were awarded to Alaska in 2023, of which nonprofits received $1.2 billion, or 3 percent. Since 2020, federal spending in Alaska had declined from pandemic peaks, but it was expected to increase with the “once-in-ageneration” influx of federal funds anticipated for the state.

The report includes a celebratory section detailing how nonprofits and tribes “ramped up” to capitalize on the economic impact of the unprecedented funding: $2.5 trillion in federal spending tied to COVID-19, $7.6 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, $2.5 billion from the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, and $2.2 billion from federal broadband funding.

However, those chickens have not fully hatched. ACLT got some bad news in April when grants from the US Department of Commerce were canceled. ACLT had facilitated training for about 500 entrepreneurs through a contract with Cook Inlet Tribal Council with funds from the Minority Business Development Agency, but the US DOGE Service informed the tribal council that agency priorities had changed.

In light of recent developments, Wolf added a cautionary note to the report: “All of the money in this section is at risk and/or has been frozen or eliminated. And I think that’s important for Alaskans to recognize and understand that we wrote this report before all those things were happening.”

John Fraser Alaska SeaLife Center

The Diomede School

Preparing the students of Yesterday Island for a bright tomorrow

By Mike DeRienzo

Da llas Sprout awoke in the night to a sound he had not immediately recognized. Groggy from the nearly two-day trip, not to mention being responsible for eight travel companions, Dallas brought himself to the window to investigate the source of this disturbance.

Looking out onto a nondescript St. Louis, Missouri, street, he noticed nothing peculiar at all. Just some aggressive drivers honking their horns, angry at some pedestrians who chose to jaywalk as opposed to walking at the designated crosswalk just up the street.

Content with his findings, Dallas returned to bed, smiling as he realized just how far he and his travel companions had come.

For most, this everyday occurrence would not be enough to wake someone up in the middle of the night, especially in St. Louis, a metropolitan area larger than

any in Alaska but still relatively calm compared to New York City or Los Angeles.

But for Dallas, principal of Diomede School on Little Diomede Island, and for his students from Little Diomede, St. Louis is practically as far away as the Moon.

An Alaska Outpost

A small island off the west coast of Alaska, Little Diomede has the distinction of being the only territory in the United States accessible only by helicopter. Mostly, though, it’s the answer to the trivia question, “Where in Alaska can you see Russia from your house?” Across the maritime boundary, neighboring Big Diomede Island is visible 2.3 miles away. Straddling the International Dateline, the pair are also known as Tomorrow Island and Yesterday Island.

There are no cars. No stoplights. Outside of housing, there are relatively few buildings on Little

Diomede, just a government building, a grocery store, and the school, which serves as the unofficial community hub. The population is in constant flux; the 2020 census counted 83 residents and falling ever since the peak in 1990 of 178.

Anyone who is not native to the area, traditionally home to the Ingalikmiut people, doesn’t stay long. With few professions available, harsh winters, unstable electricity and water, and no ability to own land unless you are indigenous, there is a lot of turnover in the area.

Any of those things would scare most people. Dallas welcomes the challenge.

“When I first started teaching out of college, I knew that I wanted to live in Alaska,” Dallas says. Originally from Colorado, Dallas moved to Alaska in 2019 to work as a teacher in Gambell, another Bering Strait community like Diomede but comparatively large with 620 or so residents.

He recalls, “After four years there, my now wife and I wanted a new challenge. There were always whispers about Little Diomede, and we had heard stories of the turnover. We wanted to make a difference, so we decided to roll the dice.”

After moving to Little Diomede, Dallas began to work as an English and social studies teacher in the middle and high school while his wife, Samantha, worked in special education. Because they were not native to the area, they had to live in subsidized housing provided by the school district. In fact, like the other teachers and principals, Dallas and Samantha lived right on campus, something they struggled with at first.

Dallas says, “At first, that took a bit of getting used to. You don’t really have that separation between work and home life if you’re always at school.”

A Loud Boom

That wasn’t the only thing that took some getting used to.

“It took a bit to adjust to this new arrangement. You really need to prepare to live in a place like this. My wife and I had to actually ship our clothes in the mail so we could carry frozen meals in totes with us on the helicopter. It can be hard. You have to plan ahead.”

Despite the necessity of plans, Alaska is notorious for having an agenda of its own. In 2023, on the Sunday after Thanksgiving while the rest of the country was enjoying leftovers and preparing for the week ahead, Little Diomede faced an unexpected windstorm.

“You really need to prepare to live in a place like this. My wife and I had to actually ship our clothes in the mail so we could carry frozen meals in totes with us on the helicopter. It can be hard. You have to plan ahead.”

Dallas Sprout, Principal/Tea cher, Diomede School

“The school building is two buildings, and the one with the apartments sits just a little higher than the school building,” says Dallas. “We were in our apartment trying to get ready for the week ahead, and we could feel our building moving back and forth. And then I just heard a loud boom.”

The cause? The city building, which is just a bit higher on the edge of the ridge, had crashed down into the school.

“At first, we thought that the school’s stilts had broken, and we were sliding into the ocean,” Dallas recounts. “We went outside and saw that the city building was just leaning against the school, and we knew this would be a problem. Then the power went out.”

Soon Governor Mike Dunleavy declared the incident a disaster, and

the school was closed indefinitely. However, while Alaska may be notorious for the unexpected, Alaskans are notorious for weathering any storm that comes their way, especially when it comes to their children.

Within hours, Chromebook laptop computers were prepared and delivered to students. Teachers and administrators mobilized instantly, going door to door to help each student set up and troubleshoot any issues with the internet, and they created contingency plans for any student whose house could not accommodate distance learning.

More Than a School

Just a few days later, every student was back to school, albeit virtually. But education was not

the only thing they missed because of the school closure, something Dallas knows firsthand.

“In Little Diomede, like a lot of other villages in the area, the school is the epicenter of the community,” he says. “At any moment, you have basketball games, Native dancing, library access. We often host large presentations since the school gym has the most room to accommodate everyone. And while I haven’t seen it, I have heard that funerals sometimes take place at the school as well.”

The school is also where doctors, dentists, veterinarians, and other traveling professionals set up to serve the community. Given Little Diomede's size, there is only a fulltime nurse practitioner, so other professionals visit periodically to serve the community. The

Alaska Owned & Operated Since 1979

www.chialaska.com info@chialaska.com

We work as hard as you do to provide great service and insurance protection to our clients. Let us show you how to control your Insurance costs. ph: 907.276.7667

school is also home to the only “hotel” on the island.

New Challenges Loom

Luckily for the citizens of Little Diomede, especially the students, the school closure was temporary. By early 2024, the school had reopened and things returned to normal. Relatively normal, at least; tensions were starting to rise with neighboring Russia, and tension on the island also increased. Dallas says he was not concerned, but he could tell people were on edge.

“There is a lot of patriotism here. There are a lot of people that lived here during the Cold War, and they remember what it was like to have to be the eyes and ears of America’s back door and have to report to the government what they saw,” he says.

“While it’s different now, the love of the United States still remains.”

The rest of the 2023–2024 school year went mostly without incident, but with all the turmoil the faculty faced that year, there was significant turnover last fall. By the beginning of the 2024–2025 school year, the faculty had dwindled to two teachers—Dallas and Samantha themselves—and a small number of support staff.

Dallas was asked to be the principal, as well as the middle and high school teacher, while Samantha was tasked with teaching elementary school and special education.

With their two classrooms, one for each teacher, the young couple— who had just married the previous May—set up a plan on how to teach twenty-one students spread

“The school is the epicenter of the community… We often host large presentations since the school gym has the most room to accommodate everyone. And while I haven’t seen it, I have heard that funerals sometimes take place at the school as well.”

From finance to health care to construction, UA is preparing students for Alaska’s jobs, building Alaska’s workforce pipeline. Learn more at empower.alaska.edu

Workforce Reports

Dallas Sprout Principal/Teacher Diomede School

2023

across grades from kindergarten to high school seniors.

Dallas set up small groups among the middle and high school students so that whichever group wasn’t getting direct instructions could work independently or on group projects.

The system was far from perfect— it’s almost impossible not to be overwhelmed listening to a teacher explain the intricacies of calculus to the group next door while you’re still trying to comprehend pre-algebra— but the students made it work.

The newlyweds adjusted to their new roles as the only faculty for the entire school, and they tackled each challenge together.

While newlyweds often face unexpected challenges during the first year of marriage, nobody could have predicted what would happen next.

Go with the Flow

On December 24, 2024, the Sprouts were preparing for their first Christmas together as husband and wife when the power went out in the whole community. While not an immediate cause for concern, the backup generator did not immediately turn on.

Three hours later, after the power returned, Dallas discovered a new issue. There was no more running water due to a problem at the water plant.

He says, “We always plan ahead for these things, so we had plenty of bottled water available. But given the holiday season, we couldn’t get a hold of anyone for a while.”

It was January before the water plant issue was fixed, but there was

“And I’m a teacher, not a plumber; I didn’t know the first thing about the water pump system.”

Still, Dallas—never one to shy away from the challenge—worked continuously to locate the problem. Eventually, a broken pump was determined to be the cause, and by February the water was back on.

Gateway Getaway

The students went back to their daily learning, and the Sprouts went back to teaching. A week later, help

he signs at the zoo.

Dallas says, “The students deserved to go to St. Louis and see that things that they do really do make it into the world. There is something tangible out there that they did and got to see. It’s important the students realize that they are more than just what they think they have to be. They can explore new worlds and have radical ideas and experience the world in a way that they didn’t think possible before. This can only happen through education.”

For 50 years, TOTE has o ered a 3-day transit, twiceweekly sailings, flexible gate-times, and roll-on/rollo operations to support versatile cargo needs, for an award-winning customer experience. When it comes to shipping to Alaska, TOTE was built for it.

Deep in the Weeds

UAF-led project studies rare earth elements in seaweeds

By Jamey Bradbury

Schery Umanzor is thinking about uses for seaweed: Food. Biofuels. Animal feed. Biodegradable packaging.

“Seaweeds have a use,” she emphasizes. “There’s a reason why it’s the fastest growing industry in the world. [But] realistically, [the United States] cannot compete with Asia or Latin America” when it comes to exporting seaweed products to the rest of the world.

Since April 2024, Umanzor has led a UAF research team in the study of seaweeds in Southeast. The team is less interested in the use of biomass—the plant material produced by seaweed—than in the potential of extracting rare earth elements (REEs) from them.

Partnering with UAF on this project are UAA, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Seagrove Kelp, Ocean Rainforest, and the Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation.

Though the project is only weeks into the second year of a two-year study, Umanzor’s team has made some promising findings. Whether REE extraction from seaweed could lead to a viable new industry in Alaska, however, would depend on a significant shift in how Americans use seaweed.

Rare and In Demand

The UAF research team’s seaweed REE extraction project was initiated, in part, by the US Department of Energy’s increased funding in 2017 to develop seaweed farming in the United States. Early research made it clear that the United States could be very successful at

UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences

Studies

producing biomass from seaweed farming, but finding a use for that biomass was a different story.

At the same time, demand for REEs increased. REEs aren’t “rare” because they’re hard to find— elements such as gadolinium, neodymium, and yttrium are more abundant in the Earth’s crust than tin, tungsten, or mercury—but they are thinly distributed and difficult

to mine efficiently. Nevertheless, they’re used for a variety of soughtafter technologies, everything from tiny motors for adjusting car seats and the light-emitting phosphors in mobile screens to laser targeting and weapons in military vehicles.

Currently, China controls most global REE mining and processing. Since the suspension of nearly all REE exports from China this April, demand for REEs has grown amid shortages that threaten many American-made technologies. Now more than ever, discovering a new way to source REEs could mean significant benefits to the United States.

Previous exploratory research by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory found that seaweeds can accumulate REEs dissolved in the ocean. The UAF team’s project builds on those findings to ask whether the seaweed off the shore of Prince of Wales Island at the base of Bokan Mountain is accumulating REEs in concentrations worth the effort it would take to recover them.

“Seaweeds are like sponges,” says Umanzor. “Our goals were to understand the geochemistry of the site, to determine what the seaweeds are accumulating and at what rate.”

The Challenges of Extraction

Bokan Mountain is not the most hospitable place. Situated at the southern tip of Prince of Wales Island, pummeled by frequent rain, the slopes yielded uranium from the Ross-Adams mine from the ‘50s into the ‘70s. This uninviting environment is exactly what makes the mountain an ideal site to explore whether

seaweeds are absorbing REEs.

“This particular site is completely exposed to environmental elements. It rains so much over there, the rain washes the rock, causing REEs to leach into the streams and then into the ocean,” explains Umanzor.

And then into the seaweed. So far, the simple answer to the question posed by Umanzor’s research is that, yes, seaweed does act as a sponge, soaking up REEs that run off from the mountain and into the ocean. Research has detected the presence of several REEs in the seaweed: lanthanum, neodymium, and dysprosium are all present at higher concentrations. Additional REEs, including yttrium, europium, gadolinium, and lutetium, are also detectable at lower concentrations.

“Higher,” though, is relative in REE research. These REEs are found at “really minute” amounts, Umanzor points out. “We’re talking parts per billion in most cases.”

Detecting REEs at such miniscule amounts was no easy feat. While the analysis of the seaweed was guided by existing methods for detecting critical minerals at low concentrations, Lieve Laurens of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and her colleagues had to use extremely sensitive instruments to detect and measure REEs from Bokan Mountain—while at the same time avoiding contamination.

“As soon as we would’ve, for example, used metal scissors or a metal spatula or touched the [samples] with our fingers, any of these samples would’ve gotten contaminated with very low concentrations of elements and

so far indicate REE concentrations of one part per million in seaweeds, which is less than 1 percent of even low-grade mineral ore.

UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences

compromised the quality of our results,” Laurens explains.

To eliminate contamination, scientists took specific care to ensure samples remained untouched through the entire process of collection, shipping, and drying. They also set up experiments to ensure their methods for REE recovery would be accurate.

Industry Potential

One gram per tonne. That’s the ratio Umanzor estimates, based on

the study’s findings so far, at which REEs can be extracted from the Bokan Mountain seaweed. It’s an important number to consider when talking about potential practical applications for this work. By comparison, Ucore Rare Metals estimated 452 grams per tonne of gadolinium, for example, in a 2011 preliminary economic assessment to revive REE mining at Bokan Mountain. Squeezing dissolved metals from seaweeds, rather than from the rock itself, would take widespread effort.

“The recovery of rare elements cannot be a standalone industry,” Umanzor says.

She envisions the possibility of incorporating REE reclamation into seaweed farms, where the REEs are recovered in a clean way that allows for the biomass to be processed for other uses, like food, animal feed, and packaging. In fact, these seaweed farms already exist—just not primarily in the United States. The expense of seaweed farming in the ocean, along with the lack of an existing

The team led by UAF will wrap up the two-year study in April 2026. New funding would be needed for the next phase.

UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences

Research reveals that seaweeds aren't passively soaking up REEs but preferentially absorb different elements, depending on species.

UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences

“pathway” to establishing additional farms, would be major hurdles to overcome, she says.

One surprising finding of the study was the discovery that different species of seaweed have different selectivity for the REEs they capture. The research team had predicted that whatever elements were present in the seaweed would be a representation of everything present in the water. Instead, REEs appear to be present in different amounts, depending on the seaweed species.

Laurens says more research needs to be done to understand exactly how seaweeds select REEs, what role polysaccharides play in adsorbing REEs, and whether there are proteins playing an active role in seaweeds by acting as “gatekeepers,” letting some REEs in while keeping others out. Gaining a better understanding of this selectivity, Umanzor says, might allow for specific species of seaweed to be planted with the purpose of collecting REEs.

“Say we want to recover neodymium, which is used in magnets and electric vehicles,” she elaborates. “Maybe we can select for a particular seaweed to collect neodymium, but that same seaweed might not be as good as others to collect europium, for example.”

Cleaning and Capturing

Seaweed selectivity may be one of the most promising findings in terms of how this research could be applied to industries in Alaska. While extracting REEs from seaweed as part of a farming operation seems unfeasible, given low local demand and the lack of infrastructure

“Using biology to capture elements is not new, but we could use it here to work with some of the mining companies to recapture additional value beyond the mine and, at the same time, clean up the water source as well.”

Lieve Laurens,

Algae

Platform Team Lead, National Renewab le Energy Laboratory

CROWLEY FUELS ALASKA

With terminals and delivery services spanning the state, and a full range of quality fuels, Crowley is the trusted fuel partner to carry Alaska’s resource development industry forward.

Fieldwork near the tip of the Panhandle might result not only in a new method to extract minerals but new tools for environmental support of inland mines.

to export biomass from Alaska, seaweeds could be used in the mining industry to reclaim REEs from runoff.

If scientists can determine which seaweeds are best at collecting specific REEs, additional value could be captured by “selectively deploying” a species of seaweed in the bodies of water near mining operations.

Laurens likens this possibility to kelp forests that are planted to clean pollutants from water.

“That vision of using biology to capture elements is not new, but we could use it here to work with some of the mining companies to recapture additional value beyond the mine and, at the same time, clean up the water source as well,” she describes.

Umanzor imagines another option: If researchers can find the mechanisms of bioaccumulation present in the seaweed, what if they

could create a synthetic version that could be thrown into water to capture REEs?

It sounds like science fiction. But fantasy could become reality with more research.

The Future of Seaweed

In the ‘80s, Umanzor points out, before kelp farming became “a thing,” there was “a lot of learning, but a lot of failure. But it was all of that groundwork that opened the door to having what we have right now.”

She sees her research on the ability of seaweed to collect REEs as a similar laying of groundwork. While she doubts seaweeds will ever become a substitute for mining or be relied upon solely for REE extraction, she does see a future in which seaweed could play a significant role in new industries.

“Everything that we are learning about is going to open a door to understanding other processes. It may not take a long time before we revisit this because we are in need of those elements. We’re going to need all possible options [for recovering them].”

Developing ways to recover REEs from seaweed, though, will require additional understanding. When the UAF research project sunsets in April 2026, new funding will be needed to continue important work toward using what’s been learned—and potentially growing a new industry that could benefit Alaska.

“It’s exciting to be opening doors,” says Laurens. “There’s a lot more to be done. There’s a lot more doors that we’re going to open, but we need continued support to make that happen.”

UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences

When Contracts Clash

Contractors’ rights and responsibilities in disputes

By Rachael Kvapil

The best-laid plans of mice and men oft’ go awry. The translated line from Robert Burns’ poem “To a Mouse” is a reminder that, no matter how carefully a project is planned, something may still go wrong. Construction contractors are no strangers to changes to their bestlaid plans, so they rely on contracts to outline how such changes should be handled by all parties involved. However, due to the complexity of modern contracts, interpretations can easily differ and cause disagreements—or worse, disputes. To mitigate disputes, contractors rely

Georgii| Adobe Stock

on legal services from firms familiar with construction industry law to find a resolution and keep them apprised of their rights and responsibilities.

Disagreement vs. Dispute

Not all disagreements become disputes, says Anne Marie Tavella, a partner at Davis Wright Tremaine. Changes anticipated on a construction project do not necessarily result in a dispute if the parties can reach an agreement as to the scope, cost, and time associated with the change. But changes can cause a dispute if there is disagreement as to the cause of the change, whether it should have been anticipated, and the cost or time impact. There are also related issues, such as timely notice and proceeding without direction, that can cause a dispute even if there is agreement on the nature and impact of a change.

“Broadly, a contract dispute is any disagreement regarding the interpretation or performance of a contract that results in additional action by the parties to address the dispute,” says Tavella. “Most contracts have a provision for disputes or dispute resolution.”

Tavella says there are many reasons for construction contract disputes, but most involve changes to the scope of work, delays, and payment issues. Changes to the scope of work regularly happen during a construction project, but the ones that may cause disputes include different-than-expected site conditions, defective specifications, or additional work ordered by the owner. Similarly, delays, which are often the result of a change to the

scope of work, are often the subject of disputes. Given that construction contracts usually include liquidateddamages clauses to compensate the owner if the project exceeds the completion date, determining whether a delay should permit excusable time or compensable time can lead to parties disputing the measurement and classification of the delay. For contractors, excusable time allows the contractor to reduce or avoid liquidated damages, and compensable time pays the contractor for the additional time caused by the delay.

Tavella adds that payment is hardly surprising as a common dispute issue. Although payment disputes between owners and general contractors happen, it is more common to see payment disputes between general contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers due to federal and state laws that provide protection to certain lower-tier contractors.

Doug Oles, a partner at Smith Currie Oles, clarifies that most construction contract disputes are based on written agreements and rarely on verbal agreements. He says that long, complex contracts have replaced handshakes when parties decide to exchange services for payment.

“Verbal and handshake agreements or even one-page contracts have faded into the past,” says Oles. “Now contracts include so many pages with industry-specific language that they’ve become less user-friendly. It’s unfortunate, but it’s reality.”

He says construction contract disputes rarely involve just two

“Verbal and handshake agreements or even one-page contracts have faded into the past… Now contracts include so many pages with industry-specific language that they’ve become less user-friendly. It’s unfortunate, but it’s reality.”

Doug Oles Partner

Smith Currie Oles

“Broadly, a contract dispute is any disagreement regarding the interpretation or performance of a contract that results in additional action by the parties to address the dispute… Most contracts have a provision for disputes or dispute resolution.”

Anne Marie Tavella Partner D avis Wright Tremaine

companies. Many disputes include multiple parties, and resolving the dispute means sorting the issues by the parties involved in the construction project. This includes the owner, designer, architect, prime contractor, subcontractor, suppliers, and more. With so many people involved in a contractual relationship, Oles says that any dispute resolution can require interpretation of multiple agreements, and those agreements may not all be consistent.

Time and Money

Tavella says resolving construction cases can be very expensive, in part due to the large volume of documents involved. Construction projects that span several years can generate tens of thousands, or more, documents. Costs for document review and production are substantial, in addition to the cost of legal services. Relatedly, many construction cases require expert witnesses—often more than one expert—which also increases the cost.

Most contracts put the responsibility on the contractor to take all actions in pursuing a claim or dispute. This includes timely notice, preparing documents and information for the owner’s consideration, timely submitting such information, and ensuring the documents meet contract requirements. For example, many contracts require a time impact analysis to prove delay. This creates an administrative burden for the contractor, even in situations where the owner is entirely responsible for the cost and impacts of the issue.

“Know your contract and ensure your field team is properly documenting any potential issues on the project,” Tavella says. “It’s impossible to know when an issue arises if it will be a dispute. However, failing to take proper action at the time, notifying the owner, or documenting the issue could result in a loss of the dispute as it gives the owner an easy excuse to deny responsibility.”

Proper documentation includes daily reports, accurate schedules, and meeting minutes. A contractor with significant documentation establishing its entitlement to a dispute can also avoid litigation, and the costs associated with it, entirely. If litigation cannot be avoided, having adequate documentation greatly improves a contractor’s chances of recovery. Without proper documentation, collecting all the facts and information is difficult due to the number of platforms on which people communicate. Discussions between parties may take place in person and via email, text messages, phone calls, and more.

Construction contracts mostly determine a contractor’s rights and responsibilities, but public contracts can be more complicated. Most public contracts cite regulations or laws that need to be cross-referenced to confirm rights and responsibilities. Even with private construction contracts, which are usually more straightforward, court cases addressing contract interpretation can affect how those contracts are administered.

Contractors generally have the right to enforce contract terms,

including seeking additional time and costs for changes and delays. There is also the responsibility to provide timely notification to the owner of any issues on the project, to await direction before performing work outside of the original scope, and to mitigate damages or increased costs.

Contractors rarely, if ever, have the right to refuse to perform work—even changed work—due to a pending dispute. A contractor who is debating whether to refuse a change order or to walk off a project due to a dispute should contact an attorney.

“Refusing to perform or choosing to abandon the project can lead to termination for default,” says Tavella, “even if the contractor is justified. Fighting over a termination is much more difficult for the contractor than fighting over a change order.”

Contractors who continue to work through a dispute should take caution when signing documents, particularly change orders, as they can cause a contractor to waive or release unrelated issues. Tavella says signing any document with a release should be carefully considered with legal counsel while a dispute is pending. Many times, she’s encountered contractors who signed releases based on verbal agreements for future change orders or other resolutions only to have the owner reverse course after the fact.

Tavella adds that parties in dispute commonly wait until a project is finished or nearing completion before addressing the issue. Although this allows the parties to focus on the construction work, waiting may force the contractor to finance the cost of the issue in dispute. This can also create a difficult situation if there www.akbizmag.com

TRY ONE

SEE FOR YOURSELF. Contact Yukon Equipment to experience the power, intuitive controls and comfort that CASE equipment delivers. Be sure to ask about ProCare— the most comprehensive, standard-from-the-factory heavymachine support program in the industry. And speaking of support, you can always count on us as your go-to resource for all your equipment needs.

Visit CaseCE.com/TryOne or contact us to schedule a demo today.

Contact us for more information. Been in business since 1945.

2020 East Third Avenue

Anchorage, AK 99501

Phone: 907-277-1541

Fax: 907-276-6795

Email: info@yukoneq.com FAIRBANKS

3511 International Street

Fairbanks, AK 99701

Phone: 907-457-1541

Fax: 907-457-1540

Email: info@yukoneq.com

WASILLA

7857 West Parks Highway

Wasilla, AK 99623

Phone: 907-376-1541

Fax: 907-376-1557

Email: info@yukoneq.com

www.yukoneq.com

PROUD SUBSIDIARY OF CALISTA CORPORATION

“It’s impossible to know when an issue arises if it will be a dispute. However, failing to take proper action at the time, notifying the owner, or documenting the issue could result in a loss of the dispute.”

Anne Marie Tavella, Partner, D avis Wright Tremaine

is turnover on the project and the individuals who were initially involved no longer work for the company. Without sufficient documentation or the ability to obtain testimony from former employees, the contractor may not be able to prove its case later in the project.

Lastly, it’s important to be thoughtful about how the dispute is discussed internally, particularly when no lawyer is involved. Tavella says emails and text messages can create problematic evidence that may need to be disclosed during litigation. Involving a lawyer in internal communications may protect documents by attorney-client privilege.

When to Seek Help

Asking a lawyer when to seek legal

assistance is like asking a doctor when to get a health checkup, says Oles. He says some wait until they’re sick (there is an actual dispute), and some seek preventive care (before there is a problem). In today’s environment, with multiple complex agreements, he suggests getting advice before a dispute arises.

Tavella agrees. “My advice is to seek legal guidance early and often,” says Tavella. “The cost for thirty minutes of advice early in a dispute or before an issue becomes a dispute is significantly smaller than the cost to litigate a case or even prepare an initial complaint.”

Seeking legal counsel early and often also allows a contractor to have strategic guidance while continuing the project. Tavella says this can help avoid other disputes

STRUCTURAL CRANE REPAIR

Onsite

Structural

Preventative

or minimize an ongoing dispute. For contractors who prefer to involve an attorney later in the process, she says it’s best to consult an attorney as soon as a disagreement looks like it will be a dispute. Many contracts, particularly with public owners, have detailed dispute-resolution processes with associated time requirements. Contractors who fail to follow the requirements can waive their claims, so working with a legal advisor before the dispute resolution process applies is important.

“It depends on the contract and the timing of when I’m contacted,” says Tavella. “If it is early in the dispute, my main goal is to determine the options that lead to the client’s desired result without the need for litigation. If it is later, the process is usually dictated by the contract.”

Either way, Tavella says the goal is to reach a resolution without a lawsuit, as they are time-consuming and expensive as employees are pulled away from their normal work to testify as witnesses.

One of the fundamental challenges to dispute resolution, according to Oles, is overcoming hostility. By the time a dispute comes to a lawyer, he says the parties are sometimes no longer listening to each other. Finding a resolution means encouraging everyone to return to rational discussions based on objective documentation. Most importantly, he says it’s important not to exaggerate claims. Some parties come to the negotiation table asking for double the amount they believe they’re entitled to, anticipating the need to bargain that down by half.

Oles says this tactic degrades the credibility of the industry.

“Lawyers should never get carried away by the emotional hostility of the parties involved in a dispute,” says Oles. “It’s important to remain objective and talk their clients down from an extreme position to a reasonable one.”

In general, Oles says people shouldn’t take adversarial positions. A contract is a path for two or more parties to achieve a goal. In that light, he says, people who hire contractors shouldn’t put unnecessary obstacles in the way of efficiently completing a project, and contractors should show the same respect for project owners. Likewise, the lawyer who assists them should focus on the relevant information to get optimal results.

Navigating the Courtroom

The specialized skills of litigators

By Amy Newman

Cl ose your eyes. Imagine an attorney. What do you see? More than likely it’s two suited professionals arguing passionately, perhaps dramatically, in a courtroom on behalf of their client.

Turns out that image is far from reality.

“The exact opposite is true,” says Lee Baxter, a civil litigator and shareholder at Schwabe’s Anchorage office. “Most attorneys never go into a courtroom. There are far more nonlitigation attorneys in Alaska than there are litigation attorneys.”

Exactly how many more is unclear. The Alaska Bar Association doesn’t maintain statistics on its members’ practice areas, but the American Bar Association (ABA) counts 1.32 million active attorney members

nationwide, and just 2.3 percent of them are members of its litigation section. However, membership in the ABA and its sections is voluntary, so the accuracy of that figure is questionable. In a 2022 ABA Legal Technology survey of private practices, 46 percent of respondents identified as primarily litigators; however, the survey was not meant to quantify how many attorneys identify as litigators, nor did it differentiate between civil and criminal attorneys.

Bonnie Paskvan—a partner at Dorsey & Whitney, head of its Anchorage office, and cochair of the firmwide Indian and Alaska Native Law practice group—thinks the number falls s omewhere in between.

“Only 25 percent of attorneys selfidentify as litigators,” says Paskvan, who is herself among the majority who do not. She references an estimate by lawyer and legal blogger Dennis Kennedy after he examined the (admittedly limited) available statistics on the subject, which included asking AI platforms. “So it’s a myth that all lawyers are litigators. The statistics show they are the minority,” Paskvan observes.

Among attorneys who do identify as litigators, very few of their cases make it to trial. The Alaska Court System Statistical Report FY 2024 shows that just 0.7 percent of general civil cases disposed of in Superior Court were resolved following either a bench or jury trial. District Court numbers were nearly identical, with just 0.8 percent resolved following a bench or jury trial.

Landmark real estate & construction projects are represented by Schwabe.

We don’t just settle on knowing your industry. We live it. Spotting trends and navigating turbulent waters can’t happen from behind a desk. The insights come when we put on our hard hats and meet our clients where they are.

“People have this opinion that attorneys are constantly in court, but the bulk of our work, the lion's share, is certainly not—at least for civil litigators.”

Whitney Brown Associate Stoel Rives

“Trials are extremely rare because they’re expensive and you can’t control the result,” Baxter explains. “So the vast, vast majority of cases are settled because the parties to the dispute choose to take less than what they’d get on their best day in court to avoid the risk of getting a result that i s very unfavorable.”

Even though most lawyers rarely, if ever, see the inside of a courtroom, they still have plenty of work to do.

Civil Litigation in Alaska

Civil law encompasses every non-criminal legal issue. Civil attorneys may market themselves as general practitioners, which means they don’t specialize in a single area of law; others may specialize in one or more.

“On the civil side, there are will and estates attorneys, tax specialist attorneys, corporate governance attorneys,” Baxter says, naming just some of the specializations. “It’s extremely rare for them to go into court and argue anything. Most of the civil cases that make their way to the Alaska court system are family law, child in need of aid cases, torts, contracts, and some business litigation.”

Transactional attorneys provide legal services that don’t initially involve a dispute between parties. Drafting business formation documents or contracts, creating estate plans, advising corporate clients, writing letters on a client’s behalf—none of these issues require the court’s involvement. A civil litigator steps in only

Named one of Alaska’s Legal Elite

NANA proudly celebrates your leadership and dedication.

Your work strengthens our corporation and re ects the values that guide us.

Pilliataqtutin, Lindsey Holmes!

when the parties’ attempts to resolve their dispute outside the court system have failed.

“A litigator overall, I think, is someone who practices across substantive areas,” says Whitney Brown, an associate with Stoel Rives. “Their skill set is [one] that specializes in going to court, handling motions, appearing before a court, and trying to resolve a dispute between their client and another entity with the court’s assistance.”

Though non-attorneys may equate litigation with the actual trial, it is instead a process that begins when the plaintiff files their complaint with the court. That makes the litigator akin to a guide who utilizes their expertise not only to achieve a favorable

outcome—whether getting the case dismissed, settling, resolving the case through mediation or arbitration, or a verdict—but to help the client understand the process along the way.

“When you hand a case to a litigator, one of the main things that they can offer is understanding the system, the kind of filings that a court would want to see and the arguments it would expect at a hearing or in a briefing,” says Danika Watson, a litigation associate in Dorsey & Whitney’s trial group. “They’re really that contact point between a historic system and the people who have legal issues. There’s so much legacy behind those rules and those procedures, and a litigator is a navigator for all of that.”

The Litigator’s Role

Navigating civil litigation, from the initial filing to trial, can take up to two years, Baxter says. Almost all that time is spent in the office.

“You’re preparing your case. That’s most of your time,” he says. “What you see on TV, Suits or Boston Legal , is absolutely nonsense. An actual presentation of civil litigation would not be TV worthy.”

That preparation—issuing and responding to discovery requests, filing and responding to motions, and deposing witnesses—comes with a court-imposed timeline to keep the process on track. Litigators, Baxter says, must be able to manage that timeline and the deadlines that come with it, or else they risk negatively affecting their client’s case.

Reach for the Stars

“Trials are extremely rare because they’re expensive and you can’t control the result… So the vast, vast majority of cases are settled because the parties to the dispute choose to take less than what they’d get on their best day in court to avoid the risk of getting a result that is very unfavorable.”

Lee Baxter Civil Litig ator and Shareholder Schwabe

Watson, who joined Dorsey & Whitney after clerkships with the Alaska Supreme Court and the United States District Court for the District of Alaska, says even she was surprised at just how little of a litigator’s practice involved the courtroom.

“It’s been really eye-opening to see the breadth of legal work that is done outside of the courtroom, and where the courtroom is not thought of as where disputes get resolved, but a risk to be aware of,” she says.

Even when litigators do appear in court, Brown says it’s often not with the legal fireworks people imagine.

“People have this opinion that attorneys are constantly in court, but the bulk of our work, the lion's share, is certainly not—at least for civil litigators,” she explains. “I work with a team of five litigators in our Anchorage office, and I would say one of us is in court every week. But that might just be for a short status conference or a motion that’s being argued.”

With so much of a litigator’s work happening outside the courtroom and so few cases going to trial, specializing as a litigator requires more than just oral advocacy skills. The ability to write clearly, persuasively, and accurately is equally important, if not more so. Exactly how much of litigation practice involves writing, Baxter says, might come as a surprise.

“You’re writing so much more than you’re speaking, which is something that is discounted by the general layperson who is not in the business,” he says. “They think, ‘Oh,

attorneys just need to be able to talk on their feet and in court.’ Every case involves so many motions and letters. It’s a 99:1 ratio—99 percent writing, 1 percent arguing.”

Non-attorneys may also be surprised to learn that, despite the adversarial nature of litigation, interpersonal skills are also hugely important. The ability to understand the client’s needs and desires, to be a skillful negotiator and be able to find common ground with the opposing party, and “know when to stand up for what’s really important and give on what’s less important” are all important skills a litigator should have in their toolbelt, Brown adds.

“Some might call them soft skills, but I think they’re pretty important,” she says. “There’s a lot of that that comes into play.”

Which to Hire: Litigator or Non-Litigator?

If a client’s legal issue is purely transactional, might they wish to retain a litigation specialist for the worst-case scenario? Not at all.

“If you have a dispute in a specific subject matter, it would be better to go to a subject matter expert first, and then worry about if it’s going to litigation,” Baxter says.

If the issue does seem headed toward litigation, then a litigator either from within the firm or outside counsel can be brought in later.

“Our advice would be to find someone that you respect and trust their advice,” Paskvan says. “If it comes to litigation and that person can’t help you, they could refer you to someone who can.”

LLC, We See Thee Limitless potential in limited liability companies

By Scott Rhode

Li ke the water a fish swims in without recognizing it, LLCs are everywhere. Not just the limited liability companies themselves; the letters are part of the background of everyday commerce. The abbreviation appears in business names so often that it becomes invisible.

Similar suffixes suffuse signage, saturating scenery with “Inc.,” “Corp.,” and “Co.” Yet these short forms are descriptive and understandable, whereas “LLC” is opaque and technical, often irrelevant and left unmentioned.

“It is typical to omit ‘LLC’ from a company name in casual conversations, social media, and marketing materials,” says Sarah Gillstrom, a partner at the law firm of

Davis Wright Tremaine. “However, the full company name should be used, including the LLC designation, in legal documents, banking documents, and tax documents.”

Three little letters are the key to an LLC’s true name, a talisman that unlocks its power.

Enter the Entity

In business organizations, “entity type” refers to the legal structure of operations. Sole proprietors and partnerships are ancient entity types; corporations are newer types, and LLCs are newer still.

“Although similar in certain ways, each entity type has distinct characteristics that impact legal rights, obligations, and protections,” says Shane Coffey, an attorney at

Manley Brautigam Bankston. One of the key features of an LLC, contained in its name, is that it limits liability.

Coffey explains, “To the extent the LLC fails to fulfill an obligation for which it is responsible (such as paying rent pursuant to a lease it signed or compensating a person for injuries it caused), the person(s) harmed by such failure can generally only pursue the property owned by the LLC to recover the debt; property owned personally by the LLC’s members generally cannot be used to satisfy the debts of the LLC.”

Gillstrom adds, “It generally limits the liability of its owners to the amount of their investment in the entity.”

Other types of corporations likewise limit liability, and they carry further

distinctions: a tax classification. C-corporations and S-corporations are tax classifications, referring to how a business is taxed by the relevant taxing authority, such as the IRS. “An entity’s tax classification determines tax rates, reporting requirements, and, ultimately, tax liability,” notes Coffey.

According to the US Small Business Administration, a C-corp is a legal entity separate from its owners. “Unlike sole proprietors, partnerships, and LLCs, corporations pay income tax on their profits. In some cases, corporate profits are taxed twice: first, when the company makes a profit and again when dividends are paid to shareholders on their personal tax returns,” the agency states. An S-corp is designed to avoid double taxation by allowing profits (and some losses) to pass through as income to the owners, avoiding corporate tax rates.

LLCs share this feature of S-corps, but self-employment taxes can sometimes be higher than taxes paid by S-corp shareholders. However, LLCs generally have fewer formalities and reporting requirements than S corps, which can simplify management.

Emily Berliner, the founder and COO of EBO Consulting, says, “I advise clients to select their entity type based on several factors: liability protection needs, tax considerations, administrative requirements, and growth plans. LLCs are popular because they provide personal liability protection while maintaining tax flexibility and requiring less paperwork and administrative overhead than corporations.”

“In my experience, professional services are most likely to advertise/display ‘LLC’—they want that sign of credibility.”

Emily Berliner, Founder and COO, EBO Consulting Inc.

Local Roots, National Reach

We help businesses in Alaska and across the country navigate complex legal challenges with confidence, so you can focus on what matters most—growth and innovation. With deep industry insight and relentless focus on your success, you’ll have the strategic guidance needed to stay ahead in a rapidly changing world.

‘90s Kids Remember

Berliner did not grow up with LLCs. Anyone older than the youngest Millennials remembers a time before LLCs, which coincidentally arose about the same time as the “.com” internet domain.

Wyoming enacted the first LLC statute in 1977, but most other states waited until 1988, when the IRS ruled that LLCs could be treated like partnerships for tax purposes. By the mid-‘90s, every state passed LLC legislation.

The wave reached Alaska in 1994. Gene Therriault, then a state representative from North Pole, sponsored House Bill 420 to define LLCs in state statutes. Therriault recalls, “Having graduated from college with a business degree, I felt it was appropriate for Alaska business

owners to have the new structure available to them similar to what so many other states offered.”

In his sponsor statement, Therriault noted that S-corps have the disadvantage of limiting ownership by certain types of shareholders, and while S-corps can avoid the “double taxation” problem, “they do not enjoy all the advantages of partnerships when it comes to allocating income and deductions.”

Limited partnerships, Therriault noted, restrict how active some partners can be, so LLCs “protect all members while imposing no limits on their involvement in operation of the business.”

Observing the adoption of LLCs in other states, Therriault stated, “LLCs have tended to be family businesses,

professional service firms, venture capital companies, real estate businesses, and startups. I believe the LLC will provide these business owners with an efficient and flexible investment vehicle that allows both limited liability and federal income tax treatment as a partnership.”

Then-Governor Wally Hickel signed the bill into law on June 8, 1994, and it took effect on July 1 of the following year. A new era of business formation dawned in Alaska.

Berliner says, “We see a lot of professional services choosing LLCs: real estate agents, consultants, small law practices, accountants. Trades love them too—such as electricians, plumbers, and tree care companies. The LLC structure works well for these businesses because they often have liability concerns

Peter Boskofsky

Recognizing his excellence in the legal profession and commitment to Alutiiq values.

ATAGUA, PETER!

2025 ALASKA BUSINESS LEGAL ELITE

but want simpler tax treatment than a corporation.”

She adds that, as LLCs became mainstream, “There were several established Alaska businesses that converted from corporations to LLCs in the late '90s and 2000s, especially smaller professional practices that found the corporate requirements too much. The conversion process involves some paperwork and potential tax implications, so it wasn't automatic.”

The IRS cautions that certain types of businesses, such as banks or insurance companies, generally can’t form LLCs.

Most states permit “single member” LLCs, and Gillstrom notes that Alaska is one.

But why advertise these esoteric qualities in the name of the business?

Because the Law Says So