Alabama Humanities at 50

Alabama inspires what’s within us.

Concert hall, theater or gallery – whatever the venue, the arts bring out the best in all of us. In a similar way, Regions is inspired to provide personal service and to create banking products that promote financial confidence for our customers. We’ll never be on a stage, but we’re always there for you, waiting in the wings.

Regions is proud to support The Alabama Humanities Alliance.

From the executive director

Charles W. (Chuck) Holmes

“We cannot afford to drift physically, morally, or aesthetically in a world in which the current moves so rapidly, perhaps toward an abyss. Science and technology are providing us with the means to travel swiftly. But what course do we take? This is the question that no computer can answer.”

—Glenn Seaborg

Do you relate? You’re not alone.

I suspect that these words connect with just about anyone who is distracted too often by a smartphone and wary of what the age of AI will bring. To this anxiety stew, let’s add social media, social isolation, declining literacy rates, and the decline of civic engagement.

Here’s the twist. The quote above is pre-Internet, uttered some 60 years ago in testimony to a U.S. Senate committee. The speaker was Glenn Seaborg and his life’s work earned him a Nobel Prize in chemistry.

This renowned nuclear scientist was speaking in favor of the humanities and the arts. He viewed them as antidotes to threats posed then by rapid technological and social transformation during the Cold War. By engaging in literature, art, languages, history, and philosophy, Americans can more smartly cope and make better, humane decisions.

“But what course do we take?”

For 50 years, the Alabama Humanities Alliance has been charting that course. We help Alabamians tell their stories, explore their past and present, and connect with each other — human to human. This year, AHA celebrates a half-century of uplifting the humanities in Alabama.

In 1965, following the testimony of Seaborg and many others, Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill passed legislation to create the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts.

In turn, that led to the founding of the Alabama Humanities Alliance in 1974. (And humanities councils like ours in all 50 states.)

Since then, AHA has enriched the lives of countless Alabamians. As an NEH affiliate, we distribute federal grants to support storytelling projects, explorations of history,

documentary films and podcasts, and community gatherings. We operate public programs like Alabama History Day. We bring traveling Smithsonian exhibitions to the state. We help educators be better educators with training and resources.

This issue of Mosaic chronicles AHA and its history. Among many achievements over 50 years, AHA co-created the online Encyclopedia of Alabama, led Alabama’s bicentennial touring exhibitions, and supported early efforts to bring literacy and lifelong learning programs to underserved rural areas.

“This is the question that no computer can answer.”

Looking back is important. More relevant is imagining the next 50 years. You’ll find that in these pages, too.

One example — in seeking to address the divides in our state, we’ve launched the Healing History Initiative. It is a sustained, multiyear effort to create opportunities for Alabamians to talk, listen, and find humanity across their differences.

Our effort uses history and facilitated group conversations to explore what we have in common while acknowledging — with civility — what divides us.

In all that we do at AHA, there is plenty of work to be done. We cannot afford to drift.

Our ability to thrive as a state relies on our willingness to keep learning for a lifetime and to nurture a shared vision of a better Alabama — today, tomorrow, and 50 years from now.

Mosaic

Mosaic magazine is published annually by the Alabama Humanities Alliance.

Editor: Phillip Jordan

Art Director: Liz Kleber Moye

Printing: Craftsman Printing

About us

Founded in 1974, the nonprofit and nonpartisan Alabama Humanities Alliance (AHA) serves as a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Through our grantmaking and public programming, we connect Alabamians to impactful storytelling and lifelong learning — and to the vibrant and complex communities we call home. We believe the humanities can bring Alabamians together and help us all see the humanity in each other. Learn more at alabamahumanities.org.

Board of directors

Chair: Ed Mizzell (Birmingham)

Vice Chair: Dorothy W. Huston, Ph.D. (Huntsville)

Secretary: Mark D. Nelson, Ph.D. (Birmingham)

Treasurer: Chandra Brown Stewart (Mobile)

Executive Committee At-Large: Robert McGhee (Atmore); Brett Shaffer (Birmingham)

Bob Barnett (Pell City)

Diane Clouse (Ozark)

Trey Granger (Montgomery)

Janice Hawkins (Troy)

Darren Hicks (Birmingham)

Elliot A. Knight, Ph.D. (Montgomery)

Clay Loftin (Montgomery)

Sheryl Threadgill-Matthews (Camden)

Susan Y. Price, J.D. (Montgomery)

Ansley Quiros, Ph.D (Florence)

Anne M. Schmidt, M.D. (Birmingham)

R.B. Walker (Birmingham)

Andy Weil (Montgomery)

Staff

Executive Director: Chuck Holmes

Director of Partnerships and Outcomes: Laura C. Anderson

Director of Administration: Alma Anthony

Director of Communications: Phillip Jordan

Program Coordinator, Alabama History Day:

Idrissa N. Snider, Ph.D.

Program Support Coordinator: Meghan McCollum

Outreach and Social Media Coordinator:

Tania De’Shawn Russell

Grants Director: Graydon Rust

In this issue

Looking Back

12 Looking Back: AHA at 50

Reflecting on our first half century

24 Alabama voices

Roy Hoffman on the power of story

Looking Forward

29 AHA honors

Profiles of our 2024 Alabama Humanities Fellows

~On Brittany Howard, by Charlotte Teague

~On Jason Isbell, by Caleb Johnson

~On Rick Bragg, by Cassandra King

~On Roy Wood Jr., by Jeffrey Melton

On the cover:

38 Humanities in everyday use

Learning from, and with, each other, by Zanice Bond

40 Etched into our being Science, the humanities, and us, by Richard Myers

44 A healing at the Forks

Exploring a painful past and new future in Florence, by Javacia Harris Bowser

62 Once the world was perfect

A poem, by Joy Harjo

7 News + Highlights

“Burst Camellia” by Nall Hollis, Alabama Humanities Fellow (2018). Courtesy International Arts Center, Troy University. Cover design by Liz Kleber Moye.

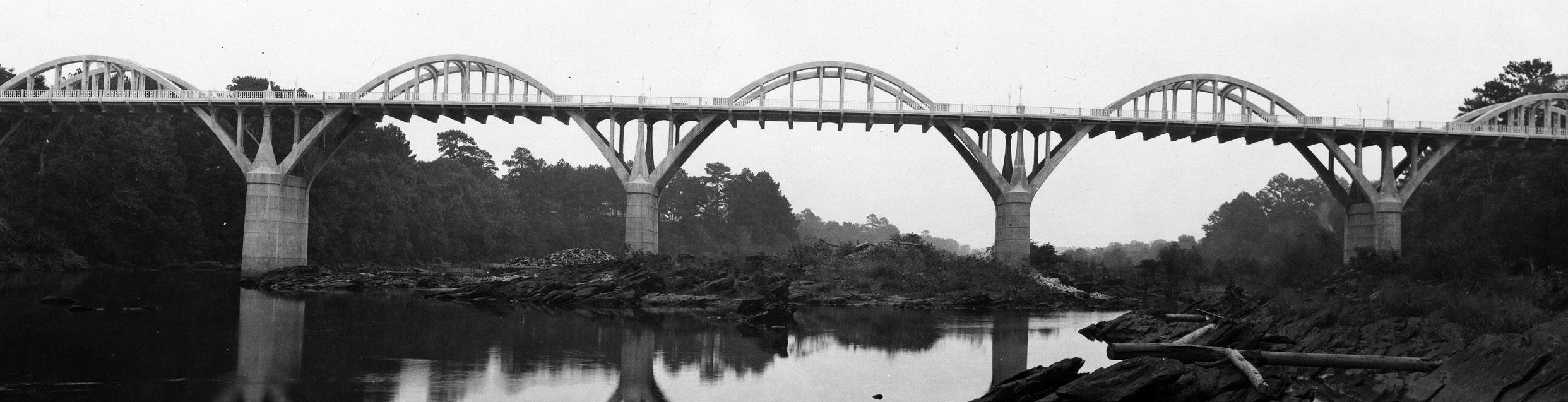

Above:

“Bibb Graves Bridge Over the Coosa River, Wetumpka, Alabama” (1931), by Will Arnold. From AHA’s 1989 In View of Home: 20th Century Visions of the Alabama Landscape , by Frances O. Robb. Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Zanice Bond, Ph.D., is passionate about the arts and the humanities as a scholar both in and out of the classroom. She earned her Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Kansas and is an associate professor of English in the Department of Modern Languages, Communication, and Philosophy at Tuskegee University. She lives in Auburn.

Javacia Harris Bowser is an awardwinning freelance journalist and the author of the essay collection, Find Your Way Back: How to Write Your Way Through Anything. In Birmingham, she’s best known as the founder of See Jane Write, a website and community for women writers.

Joy Harjo is a poet, musician, and playwright, and a member of the Mvskoke (Creek) Nation. She served as the 23rd Poet Laureate of the United States from 2019-2022 and received the Harper Lee Award for Alabama’s Distinguished Writer at the 2023 Monroeville Literary Festival.

Roy Hoffman is author of the novels The Promise of the Pelican, Come Landfall, Chicken Dreaming Corn, and Almost Family, and the nonfiction books, Alabama Afternoons and Back Home. He has written for The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Mobile Press-Register, and is on the faculty of Spalding University’s Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Writing.

Caleb Johnson authored the novel Treeborne (Picador), which received an honorable mention for the Southern Book Prize. He grew up in Arley, Alabama, and studied journalism at the University of Alabama. His past jobs include newspaper reporter, janitor, middle-school teacher, and whole-animal butcher. He teaches creative writing at the University of South Alabama.

Cassandra King is the awardwinning author of five novels, two books of nonfiction, numerous short stories, magazine articles, and essays. A native of L.A. (Lower Alabama), she currently resides in the South Carolina Lowcountry and is at work on a new novel. She is also an Alabama Humanities Fellow (2017).

Jeffrey Melton, Ph.D., is professor of American Studies at the University of Alabama. He is author of Mark Twain, Travel Books, and Tourism (2002) and co-editor of Mark Twain on the Move: A Travel Reader (2009). Much of his writing and research focuses on American literature, humor, and satire.

Richard Myers, Ph.D., is chief scientific officer, president emeritus, and faculty investigator at the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology in Huntsville. He is a native of Selma and a graduate of the University of Alabama. As director of Stanford University’s Human Genome Center, he worked extensively on the groundbreaking Human Genome Project.

Charlotte C. Teague, Ph.D., is associate professor and chair of English & Foreign Languages at Alabama A&M University, where she has taught for 20 years. She specializes in professional writing (creative, media, and technical) and Black women writers. She transitioned into academia after working as a project consultant and technical/ scientific writer-editor.

Contributing Artists: Erol Ahmed, Will Arnold, Katie Baldwin, Pinky/MM Bass, Chris Carmichael, Chip Cooper, Solomon Crenshaw Jr., Nall Hollis, Tori Nicole Jackson, Marla Kenney, Heather Logan, Lutisha Pettway, Alvin C. Sella, Logan Tanner, Caroline Veronez, Dave Walker.

Contributing writers and editors: Laura Anderson, Kathy Boswell, Chuck Holmes, Olivia McMurrey, Tania De’Shawn Russell.

Special thanks: Jack Geren, Maví Figueres, Wayne Flynt, Carrie Jaxon, Amy Jenkins, David Mathews, Natalie A. Mault Mead, Brian Murphy, Christine Reilly, Philip Shirley, Robert C. Stewart, Susan Willis, Odessa Woolfolk.

Contact us: 205.558.3998 ahanews@alabamahumanities.org alabamahumanities.org/mosaic-magazine

Photo: Denise Toombs

Preserving Tradition

Descended from the native peoples of the Mississippian period (AD 800-1500), our ancestors endured great hardship and discrimination after the Indian Removal Act with an indomitable spirit, nobility and grace. Our Tribe became empowered with a strong mission to provide for ourselves and the communities in which we live with a dedication to service, philanthropy and the revitalization of traditional arts and culture.

The story of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians is a true American success story—one of strength, perseverance, and prosperity.

Fifty years of sharing Alabama’s stories

Much has changed at the Alabama Humanities Alliance over the past half century. Look no further than our name, which has “evolved” four times in five decades. But as we’ve mined our archives and planned our anniversary commemorations this past year, one theme kept turning up. One through-line we can trace from Then to Now.

For fifty years, storytelling has remained at the heart of who we are and what we do. And there’s a reason for that.

When we explore the humanities — our history, literature, culture, art, and more — what we’re really doing is getting to know each other better. We’re sharing our stories, and listening to others'. We’re linking our past to the present. And we’re discovering the common ground, and the common humanity, that binds us all.

Especially now, the more we can be part of each other’s stories, the better. So, consider this your invitation. Become part of the story of the humanities in Alabama — as we celebrate this milestone and look forward.

Join in our 2024 Alabama Colloquium series

On August 26, in Huntsville, we celebrate two storytellers in song — north Alabama natives Brittany Howard and Jason Isbell. Then, come December 2, we honor a writer, Rick Bragg, and a humorist, Roy Wood Jr., who will make us laugh and think in equal measure. Learn about our 2024 Fellows starting on page 29.

Watch ‘AHA at 50’

This year, we gathered some of our longtime friends and partners from around the state for a series of roundtable conversations. We wanted to hear what impact they’ve seen the humanities make in our state. And where they hope the humanities can help lead us from here. Watch at alabamahumanities.org/aha-at-50.

Share your ‘My Alabama Story’

We’ve been enlisting some of Alabama’s most compelling writers, artists, and thinkers to reflect on their connections to this place we call home. This land, its people. Its problems. Its promise. Our past and future. The series will be published in full in 2025; in the meantime, share your story on social media with #AHAat50 and #MyAlabamaStory.

Donate toward our next fifty years

More than a time to reflect, this moment offers an opportunity to build a foundation for our work to come. All of AHA’s original programming — including this very magazine — relies on the generosity of our fellow Alabamians. Consider a gift using the reply card in this issue, or donate at alabamahumanities.org/support.

Unvanishing (2002), by Alvin C. Sella. Courtesy Alabama State Council on the Arts and the Sella family.

More: go.uab.edu/history-ma

Banner year for Alabama History Day

Our next Alabama History Day is set. Join us as a student participant, teacher, or judge on March 21, 2025, at Troy University in Montgomery.

AHA annually presents this history competition that engages students in robust and creative historical research, culminating in a statewide contest — and a chance to advance to National History Day. Our 2025 contest has plenty to build on.

In 2024, AHA organized our first-ever regional competition, in Mobile. And more student participants joined in our statewide contest than ever before. Cohort-style trainings are helping Alabama educators learn how to maximize History Day as a project-based learning tool for the classroom. And we launched a summer-long Alabama History Day program for youth at Mt. Meigs, thanks to partnerships with the Alabama Writers Forum and Alabama Department of Youth Services. All of this is made possible by state funding through the Alabama Commission on Higher Education, as well as generous support from Alabama Power and the Bezos Family Foundation.

Plus, 35 student winners from our state contest competed at National History Day this summer in Maryland and Washington, D.C. Several Alabama students — and one of their teachers — came home with national recognition.

• Kristian Pittman (Alabama School of Fine Arts, Birmingham) had his exhibit, "The Other Side of the Tracks: The Legacy of Redlining,” displayed at the National Museum of American History.

• Ethan Gwinn (Baker High, Mobile) and Ddwayne Lockett-James (Murphy High, Mobile) had their documentary screened at the National Museum of African American History and Culture: Rediscovering Roots In the Harlem Renaissance: How Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon Contributed to Clarifying African American Ancestry.

• Isaac Livingston’s research (Westminster Christian Academy, Huntsville) landed him a visit to Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. There, he had the chance to meet with both U.S. Rep. Dale Strong and U.S. Sen. Tommy Tuberville about his project on “The Tennessee Valley Authority: A Turning Point in Southern History.”

• Nakeria Woods (Murphy High School, Mobile) and Ashton Dunklin (Clark-Shaw Magnet School, Mobile) won “Outstanding Affiliate Entry” awards.

• Kathy Paschal, a teacher at Stanhope Elmore High School in Millbrook, was a finalist for National History Day’s 2024 Patricia Behring Teacher of the Year award.

From a Crossroads to a SPARK!

Since 1997, AHA has coordinated with the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum on Main Street to bring traveling exhibits to Alabama — a dozen, so far, in 60-plus communities.

In 2023-2024, we brought Crossroads to the state, exploring change in rural America over the past century. In 2025-2026, AHA has secured a new exhibit: Spark! Places of Innovation. It features stories from diverse communities across the nation that will inspire Alabamians to think about how innovation has shaped our own cities and towns — and to consider how we might each be innovators ourselves.

The exhibit will travel to six locations spanning the state: Athens, Brewton, Dothan, Fort Payne, Sylacauga, and Uniontown. Thank you to our lead sponsor, Innovate Alabama, for their support.

Stay tuned for tour dates and local programming!

Humanities highlights

Congrats, Riley Scholars!

Across 2023-2024, the Alabama Humanities Alliance named five educators as Riley Scholars. AHA’s competitive Jenice Riley Memorial Scholarship is awarded annually to K-8 educators who excel in teaching history, civics, and geography. Each Riley Scholar receives funding to support their professional development or creative classroom projects.

Supported through AHA’s W. Edgar Welden Fund for Education, this scholarship is named in memory of the late Jenice Riley — a passionate educator and daughter of former Alabama governor and first lady Bob and Patsy Riley.

Across 2023-2024, five teachers earned distinction as Riley Scholars, representing five different schools from around the state.

• Lexi Banks

Magic City Acceptance Academy, Birmingham Project: Birmingham Civil Rights Institute class trip

• Willie Davis III

Charles F. Hard Elementary, Bessemer Project: A Community of Helpers

• Abby Crews

Mulkey Elementary, Geneva Project: Living History Wax Museum

• Shatia Howard

Lakewood Elementary, Huntsville Project: Diverse Friends, Happy Hearts

• Alana McNeil

Farley Elementary, Huntsville Project: Mapping Our World

Welcome new board members

Clay Loftin, of Montgomery, is manager of governmental affairs for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama. He is responsible for legislative advocacy and healthcare policy efforts to ensure access to quality, affordable healthcare for more than 2 million Alabamians. Loftin has served on many boards, including the Girl Scouts of Southern Alabama, the Children’s Trust Fund Leadership Council, and Leadership Montgomery Torchbearers Class XIV. Raised in Prattville, Loftin graduated from Auburn University at Montgomery in 2010 with a B.A. in political science.

Ansley Quiros, Ph.D., of Florence, is an associate professor of history and chair of the Department of History at the University of North Alabama. She studies twentieth century U.S. history, with a focus on race, politics, and religion. Quiros’ award-winning first book, God With Us: Lived Theology and the Black Freedom Struggle in Americus, Georgia, 1942-1976 (UNC, 2018), examined the struggle over race and Christian theology in the civil rights struggle in Southwest Georgia. Quiros serves on the board of Common Ground Shoals and Project Threadways and, along with Brian Dempsey, Ph.D., co-directs the Civil Rights Struggle in the Shoals Project.

Abby Crews, a social studies teacher in Geneva, Alabama, celebrates her Riley Scholarship with her fifth grade class at Mulkey Elementary School.

Grantee spotlight:

News vs. Misinformation

According to recent research, the top worldwide risk over the next two years is misinformation influenced by artificial intelligence. And that’s a problem, especially in an already unprecedented election year.

To that end, one of AHA’s recent grant recipients, Alabama Media Professionals, hosted a series of public forums to highlight the importance of journalism to our democracy — and to help Alabamians identify the difference between accurate reporting and false information. During a forum at the Hoover Public Library, media scholars shared advice for how anyone can better identify misleading propaganda, while local journalists shared how they’re working to build trust and provide accurate, relevant reporting.

“It’s on us [as journalists] to focus on what’s important rather than what people want to argue about,” said Jon Anderson, editor of the Hoover Sun. “And it’s incumbent upon [our readers] to look at where a source is getting its facts. Do you trust that source? You may go look somewhere else just to double-check it with another source, maybe somebody that you don’t always agree with.”

“There’s an idea that ‘transparency is the new balance,’” added Andrew Yeager, managing editor of WBHM. “Letting people behind the curtain a little bit more to know where we got our information and how we got our information, that transparency is part of our accountability, too.”

Of course, even facts carry only so much currency in this ultrapolarized world. Sometimes, it’s more important that we, as citizens and neighbors, learn to disagree with civility and seek out common ground more often than political takedowns.

“If you’re trying to change people’s minds or change people’s leanings based on fact-checking something or debunking something that they believe is true — but isn’t — I’m not sure that’s an effective strategy,” said Matt Barnidge, Ph.D., associate professor of journalism and creative media at the University of Alabama. “I would encourage everybody to try to find points of similarity, points of connection. How can you connect with this person and bring them in to what you want to talk about, bring them to the ideas that you want them to reflect on. Over time, maybe that might move the need a little more.”

Apply for your AHA grant

The Alabama Humanities Alliance serves as the primary source of grants for public humanities projects statewide, helping nonprofits bring our state’s history, literature, and culture to life. Since our founding, that translates to more than $12.5 million in funding we’ve awarded.

All Major and Media Grant applications are evaluated by the AHA Grants Review Panel, an independent team of humanities scholars and public practitioners of the humanities who bring a diversity of perspectives, geography, and expertise. Current panelists: Matthew L. Downs, Ph.D., of Daphne; Benjamin Isaak Gross, Ph.D., of Jacksonville; Tina Naremore Jones, Ph.D., of Livingston; Charlotte C. Teague, Ph.D., of Huntsville; and Shari L. Williams, Ph.D., of Warrior Stand.

Read our Grants Roundup on page 53 and learn how AHA's most recent grantees put their funding to use.

Learn more:

Scenes from the AHA-funded "News vs. Misinformation" panel presented by Alabama Media Professionals.

Photos by Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

“Nobody should expect that a few words from a poet or a philosopher may sit right a distressing situation or provide a completely new orientation for a community. But poets and philosophers can help us find the way up the mountain. The path we take from there can be our own.”

—Duard

LeGrand, AHA founding member (Humanities Forum, 1977)

Looking back: AHA at 50

by Phillip Jordan

As 1974 dawned, Jack Geren found himself preparing for a new semester at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. The 29-year-old Geren was an assistant to the dean in UAH’s School of Humanities and Behavioral Sciences — not much older than the students around him. But he had already held a few positions, inside and outside of academia, since graduating from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

One day, a colleague mentioned to Geren that some sort of new humanities organization was being formed in the state. And it needed an executive director.

Geren looked into it. He learned this wasn’t just another humanities program bound to college campuses. Far from it, in fact. This new group was intent on making the humanities relevant to the lives of everyday Alabamians and the communities where they lived. It would partner with the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to secure funding that could support humanities-rich projects around the state.

Geren was intrigued. He applied, but never expected to land an interview, much less the job. As it turns out, though, he was the man for the job. By February of 1974, letters of congratulations began arriving in Geren’s mailbox.

One came from an old history professor of his, David Mathews, Ph.D., who had just taken on a new job of his own — as president of the University of Alabama: “I think it is a venture that you will find is just your thing,” he wrote Geren, “and I wish you every success.”

David Wigdor, a program officer at the NEH, closed his note with this: “Good luck as the Alabama program zooms out of the Rodeway into high gear.”

AHA funds 13 initial grantees statewide. Five decades on, we've awarded $12.5 million to 2,182 public humanities projects — and counting.

Alabama Humanities Alliance is born… as the Alabama Committee for the Humanities and Public Policy.

Celebration of U.S. Bicentennial with resources and exhibits statewide.

First name change as the Committee for the Humanities in Alabama broadens its focus. Programs in history, literature, religious studies, and art history become more popular.

First oral history project, featuring interviews with

Tuscaloosa County senior citizens.

Geren was indeed soon on the road himself, heading south for Birmingham. His first task: Finding a home for this new enterprise, one that would initially be called the Alabama Committee for the Humanities and Public Policy.

“Apprehension, excitement, I felt both of those things,” Geren recalls now, sitting in his small home on the edge of Huntsville’s Old Town Historic District. “Certainly, excitement because the purpose was something very important to me. Apprehension because I wasn’t sure exactly how to start and sustain this idea.”

His anxiety was understandable. This was 1974. The nation’s mood was cynical, at best. The Vietnam War was ending, badly. Watergate was the word, soon to take Nixon down (and, incidentally, to propel UA’s Mathews, a founding board member of Alabama Humanities, to a cabinet position in Gerald Ford’s administration). Here in Alabama, George Wallace was governor, again. Integration remained a loaded term. And a super outbreak of tornadoes carved a path of destruction

Alabama Humanities Resource Center opens, with the Alabama Public Library System. A free Blockbuster Video of sorts, it’s filled with documentaries, recordings, photos, and more.

across north Alabama, not long after Geren headed to Birmingham.

But Geren carried something else south with him that early spring day, something that sustains the Alabama Humanities Alliance’s work fifty years later: A belief in the power of telling, and sharing, our stories with each other — a power that can help us, collectively, take on any challenges we might face in Alabama. And help us better understand each other, as well as the vibrant and complex communities we each call home.

What's in a name? That was the question in 1974.

“This was something brand new that really was intended to have a positive influence on life in every county in the state,” Geren says. “We were trying to get people to think and talk about their communities, together, with support from professors and humanities professionals around the state. It was an exciting idea and an exciting time.”

On April 9, 1974 — one year after a committee of Alabamians had first begun conversations with

Images 1980: An Exhibition of Alabama Women Artists, curated by Montevallo art historian Patricia A. Johnston, is one of AHA’s earliest arts + humanities grant projects.

Theatre in the Mind begins with our first NEH Exemplary Award. TIM supports preshow programs, artist talks, and more to enhance Alabama Shakespeare Festival productions.

the National Endowment for the Humanities about starting a program in Alabama — the NEH sent a letter to Governor Wallace, officially announcing this new “experimental statewide program.” The letter shared, in part, that this new Alabama-based program would “offer the public something always vitally needed in a democratic society — namely, the thoughts, ideas, and insights of philosophers, historians, and other humanists.”

From there, our predecessors hit the ground running. Geren, with his new staff and board members, crisscrossed the state, meeting citizens from all walks of life to introduce this new concept in the humanities. We dedicated most of our outreach to connecting with community cornerstones such as libraries, museums, colleges, cultural festivals, historical societies, literary groups, and more — establishing vital relationships that last to this day.

We had some headwinds to surmount. Not the least of which was defining just what the heck the humanities are. Then, as now, we’re sometimes confused with humanitarians, philanthropists, or social-service providers. Case in point: In those first few years, we received calls from folks asking to give blood, requesting help with stray dogs, and offering to donate their body to medical science.

Philip Shirley, an early staff member, remembers teaching at least 100 grant-writing workshops as part of his travels to every county in the state — and likely every public library, too. He also distinctly remembers a very early Betamax video that he and others on staff (including his future wife, Virginia Shirley) would tote to speaking engagements. Of course, that meant they also had to haul a near-industrial-grade projector along for the ride.

of To Kill A Mockingbird in Eufaula, part of our 1983 Alabama History and Heritage Festival. Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History. At right: One Alabama Humanities Fellow, Odessa Woolfolk (right), welcomes a new Fellow, Imani Perry, in 2023.

Alabama History and Heritage Festival features storytelling, lectures, conferences, film screenings, music, and exhibits statewide, with a closing festival at the state capitol.

1985

Religion in the South conference at BirminghamSouthern College brings theologians, historians, authors together to explore religion’s impact on Southern culture.

Second name change to Alabama Humanities Foundation

1986

Utopia in American Life and Literature (U’ALL) explores the utopian impulse in America and the Single Tax Colony in Fairhope. The statewide project earns an NEH Exemplary Award.

Eyes on the Prize debuts on PBS, the first of many AHA-funded films to make a national impact. It wins a Peabody Award, six Emmys, and a Best Documentary nom at the Academy Awards.

1987

Top: Harper Lee signs copies

“The thing I was happiest about was that our reach was extensive,” Shirley recalls. “We were able to get to all of these little communities across the state. We were on the road all the time. We would meet with mayors, librarians, community college leaders, whoever we could, just to introduce ourselves. I was proud that we were able to, pretty quickly, create widespread awareness for our grants and our humanities programs that would be useful locally.”

Odessa Woolfolk was one of the Alabama Humanities’ “early adopters.” In the mid-1970s, the revered educator — who would later become the founding president of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute — was the recently appointed director of UAB’s Center for Urban Affairs. And she was thrilled by AHA’s arrival on the scene.

“I recall the founding of the organization shortly after I began my career at UAB,” Woolfolk notes. “I was so excited that this old industrial place, my hometown, had discovered the humanities and cultural arts.”

She soon became one of AHA’s early project scholars. Through the years Woolfolk has spoken at some of our biggest events, including when we’ve honored Alabama Humanities Fellows such as Harper Lee (in 2002) and Imani Perry (in 2023), and when we hosted the acclaimed author Toni Morrison at our 1999 silver anniversary celebration.

Meanwhile, back in 1974, Jack Geren had succeeded in finding an initial headquarters for Alabama Humanities, on Birmingham-Southern College’s campus. The school provided our office rent-free as we established ourselves, and BSC would remain AHA’s home for the next three-plus decades. Its closing this year brings to mind bittersweet memories, especially for those who were there in those early years.

AHA debuts the Humanities Speakers Bureau (aka Road Scholars) as part of commemorations for the U.S. Constitution bicentennial. Today, the program remains as vibrant as ever.

In View of Home collaboration with Huntsville Museum of Art — and museums and libraries statewide — sparks a yearlong examination of Alabamians’ connection with the land.

Alabama Humanities Awards debut. Winton

“Red” Blount is the first of 55 honorees so far, including the likes of Harper Lee, Fred Gray, Wayne Flynt, Bryan Stevenson, and E.O. Wilson.

Mosaic debuts as AHA’s new newsletter, eventually evolving into the full-fledged storytelling magazine you’re holding now.

A sampling of award-winning films and series that AHA has helped fund through the years.

Of course, our own success — and lasting presence today — also was far from guaranteed. In fact, if you read that initial letter to Governor Wallace announcing our creation, you wonder if its author would have bet on a fiftieth anniversary ever arriving for our fledgling organization. The word “experiment” or “experimental” was used seven times to describe us…in a six-paragraph letter.

Still, by the summer of ’74, we had officially hung our shingle, printed the requisite brochures, and hosted a “listening tour” of public meetings in Florence, Huntsville, Anniston, Birmingham, Tuscaloosa, Selma, Montgomery, Dothan, and Mobile. Thankfully, the public responded. By that fall, according to our first newsletter, we sent out our first call for grant proposals, for “projects promoting dialogue between professional humanists and the adult public about issues of importance in Alabama.”

Then, as now, all AHA grant funding comes from our affiliation with the National Endowment for the Humanities. And in those early years, we put out a theme for organizations to use in crafting their

proposals. Our first theme, in 1974, was called “Priorities and Human Values in a Changing Alabama: At City Hall, Courthouse, and Statehouse.”

That theme reveals a key difference between the Alabama Humanities of 1974 and today. As our initial name implied, a major goal was to bring the humanities to bear on public policy. It was a fairly remarkable purpose at the time. In practice, that looked like providing resources, forums, and humanities professionals (historians, scholars, writers, artists, and more) to help citizens better understand the issues affecting their towns — and why folks might see the same issues differently. In the end, we hoped, Alabamians might gain new perspective on how to approach pressing public policy issues of the day.

We funded 13 projects in that first round of grants, supporting a diverse array of projects — in places from Mobile and Huntsville to Butler and Sand Mountain. Among them, a statewide series of public forums designed to help Alabamians learn about “the policies and practices which govern the jails and prisons in the state.” We also funded “The Quiet Dignity of Choice,” a photography exhibit and narrative survey of the people

SUPER Teacher program begins, signaling AHA’s commitment to serve Alabama’s educators with trainings and resources that enhance teaching and professional development.

Rebuilding Alabama’s Front Porch, a year long effort for our 20th anniversary. It culminates in a televised conversation about reconnecting with our neighbors and communities.

Glimpses of Community photography project enlists Alabamians to document everyday life in their communities. More than 1,400 photos come in for exhibitions across the state.

Partnership begins with Museum on Main Street, bringing Smithsonian traveling exhibits to 60-plus Alabama town, so far, and inspiring discussions about our past, present, and future. 1999

Silver Anniversary Gala in Birmingham celebrates AHA’s first 25 years. The event features legendary author Toni Morrison and Alabama Humanities Fellow Odessa Woolfolk.

Images from Frances O. Robb’s In View of Home. The book, created in partnership with the Huntsville Museum of Art, led to a year-long series of programming. The project won AHA its first-ever Schwartz Prize, a prestigious award from the Federation of State Humanities Councils. Middle image: The Clown Wagon (1987), by Chip Cooper. Courtesy Huntsville Museum of Art.

Sir Jonathan Miller, the renowned British stage director, spoke at the first event in an innovative, decades-long series produced by Alabama Humanities and the Alabama Shakespeare Festival.

and places of the Tennessee Valley, highlighting the region’s folk art, architecture, and cultural traditions.

And who received our first-ever grant? According to the paperwork, it appears that honor goes to Spring Hill College’s Human Relations Center, which received $9,000 for a “Colloquium on Human Values and Rights.”

To give an idea of just how different the focus was those first few years — using the humanities to provide a new lens through which to view policy issues — here’s the short description of that Spring Hill project: “A series of five presentations and discussions dealing with issues of capital punishment, environmental deterioration, abortion, and voter registration.”

Pulling no punches, we were.

While you can still hear echoes of that original mission from time to time, the emphasis on directly affecting public policy faded rather quickly. By the late ’70s, the organization’s focus had shifted more to what you’d

recognize today — the funding and promotion of impactful storytelling and lifelong learning that bring Alabamians together through the exploration of our shared history, our rich culture, our literature, art, and so much more.

One thing that hasn’t changed: We remain the primary source of funding for public humanities programming in Alabama. Since 1974, we’ve awarded more than $12.5 million in support of at least 2,182 public, humanitiesrich projects statewide — and counting.

Margaret Norman, of the Birmingham Jewish Federation, knows the impact of an Alabama Humanities Alliance grant. In 2023, she helped Temple Beth El earn an AHA grant for “In Solidarity,” a video and immersive civil rights experience at the temple exploring Birmingham’s civil rights movement through the lens of the city’s Jewish community.

Since then, “In Solidarity” has opened up new conversations among, and well beyond, Birmingham’s Jewish community. It has also received national attention from outlets like The New York Times for its approach to storytelling that asks visitors to “think about how these stories inform the way you make sense of the past, present, and future. What does it mean to be in solidarity with our neighbors?”

“AHA was probably the first organization to give us a grant for this,” Norman says. “And it did feel like a really big step in terms of conferring legitimacy to what we were doing. Even the process of receiving that grant opened us up to other opportunities because it helped us establish, ‘we’re here, we’re doing this project. This is a real thing.’”

Martha Bouyer, Ph.D., executive director of Historic Bethel Baptist Church Foundation, has served as a

Scholar Martha Bouyer partners with AHA to develop Stony the Road

We Trod, an immersive (and ongoing) NEH teaching institute that helps educators explore Alabama’s civil rights legacy.

2003

Founding of Jenice Riley Memorial Scholarships for K-8 history and civics teachers. We’ve awarded $110,000 to 106 Riley Scholars, supporting classroom goals and professional development.

First (of many) grants awarded to the innovative Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project, which provides humanities-rich educational opportunities to incarcerated Alabamians.

2006

After Hurricane Katrina, AHA and the NEH respond with emergency grants to the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park, Museum of Mobile, and public libraries along the coast.

A sampling of AHA publications and marketing materials, from the 1970s through the 2010s.

community partner for Temple Beth El’s project. She’s also an AHA project scholar, past grant recipient, and director of the AHA-funded teacher-education experience, “Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy.”

“It’s important that other organizations like the Alabama Humanities Alliance will stand up and take a chance on someone,” Bouyer says, “on someone who maybe nobody knows, no one who’s done anything, but who has an idea that might, just might, make a difference, if we empower them.”

Hitting our stride

As the 1970s turned to the '80s, we began dipping our toes into the land of original programming — going beyond grant-making alone.

In 1978, we responded to the national energy crisis with “Energy and the Way We Live.” As we noted in announcing the project: “The energy crisis affects us all. It threatens our way of living together, but it also offers us the chance to look at our past, and plan for the future.” In partnership with the Alabama Public Library Service and community colleges around the state, we presented public forums addressing the roots and

Encyclopedia of Alabama launches with plaudits from Gov. Bob Riley and Sen. Richard Shelby. Now 2,500 articles deep, the EOA’s 15.2 million visitors learn about all things Alabama.

2009

2008

AHA sponsors the Southern Literary Trail, highlighting Albert Murray’s Mobile, Lilian Hellman’s Demopolis, Ralph Ellison’s Tuskegee, F. Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald’s Montgomery, and more.

2010s

To Kill a Mockingbird: Awakening America’s Conscience honors the enduring significance of Harper Lee’s novel; the series ends with a screening of the AHA-funded film Our Mockingbird

2011

2010

With support from the NEH and Books-A-Million, AHA provides grants and donates 2,000 books to help schools and public libraries recover from the devastating tornadoes of April 2011.

impacts of the crisis on Alabama’s communities.

Then, in 1979, we launched our first AHA-directed effort, the Rural Humanities Program, providing ongoing resources to support rural Alabama communities. The program spawned discussion groups, oral history projects, and community festivals.

Both of these early efforts helped us dive into ever more ambitious projects.

First up, in 1983, was the Alabama History and Heritage Festival, which had been two years in the making. A massive, three-month “jubilee of the spirit of Alabama and its people,” the festival featured 50-plus events — storytelling, lectures, conferences, film screenings, music, exhibits — all focused on the local communities hosting the events. Locales included Auburn, Demopolis, Eufaula, Anniston, Mobile, Birmingham, Huntsville, and a concluding festival at the state capitol. The festival not only drew out the famously private Harper Lee to speak but it also resulted result in a book, Clearings in the Thicket: An Alabama Humanities Reader, that was published the following year, and shared talks and papers by festival participants with a wider audience across the state.

Then, in 1984, we launched Theatre in the Mind, thanks to our first Exemplary Award from the National

Endowment for the Humanities. What began as a one-off project would soon turn into a decades-long partnership with the Alabama Shakespeare Festival. It remains one of the best-known programs we’ve ever produced, and it had a profound impact on both organizations. For AHA, it was pivotal in two ways: It demonstrated how effectively the arts and humanities can enhance each other, and it established a model for collaborative programming that we follow to this day.

Former Alabama Humanities staff member Christine Reilly was tasked with shepherding Theatre in the Mind into existence. She remembers well its ambitious and auspicious opening, with a seminar led by Sir Jonathan Miller, the world-renowned British stage director.

“As he ascended the podium to launch the Theatre in the Mind project, all of us collectively held our breath,” Reilly recalls. “This was the first major event of [Alabama Humanities’] first directed project! But we soon exhaled as the brilliant and funny Miller captivated the standing-room-only audience.”

From there, the program was off and running. The concept for Theatre in the Mind was as straightforward as it was inventive: help people better appreciate, understand, and relate to the theatre. In practice, that took the shape of seminars led by well-known directors; a lecture series about each play produced by the Alabama Shakespeare Festival; workshops for drama teachers; printed publications; and a travel program that took theatre scholars and actors to schools, churches, and community centers across the state.

But the staple of Theatre in the Mind was the 15-minute “BardTalk” that would occur before each and every ASF performance — sparking curiosity and providing context for the play the audience was about to watch. And for 30 years, Susan Willis, Ph.D., delivered just about every

AHA’s Black and White Masked Ball in Mobile, on 45th anniversary of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, raises funds for Alabama Humanities programming in South Alabama.

Prime Time Family Reading Time debuts, aimed at increasing literacy among Alabama families. The program eventually transitions to a grants approach, supporting existing literacy groups.

Literature and Healthcare initiative helps healthcare professionals view their work through the humanities and gain greater empathy for their patients and each other.

2015

First Lady of the Revolution premieres, telling the story of Birmingham’s Henrietta Boggs, who married a future president of Costa Rica — and became a key figure in the country’s 1948 revolution.

Championed by executive director and Gulf War veteran Armand DeKeyser, Literature & The Veteran Experience helps U.S. veterans discuss how works of literature relate to their own war experiences.

Ramona Hyman, AHA Road Scholar, gives a talk on Rosa Parks, at Huntsville’s Oakwood College in 1992. Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History, donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Dave Dieter, Huntsville Times.

BardTalk there was. Patrons, in fact, often referred to her as the “Bard gal.” It was a term of endearment and one she embraced; for a time, it even graced her license plate.

“The plays didn’t need me to do their work for them, of course,” Willis says, “but I tried to give audiences permission to open up and listen, to greet and enjoy the ideas and issues, the human experiences and artistry they were about to meet.”

As the ASF’s resident dramaturg — and a longtime professor of English — Willis ran the Theatre in the Mind program for 30-plus years. And she has seen its lasting impact in the Alabama Shakespeare Festival’s educational programming to this day.

“Planning Theatre in the Mind meant weaving aspects of the humanities and the arts into each season’s pattern of plays — always different, always challenging,” she recalls. “It offered ASF a joyous and stimulating opportunity, and the many talented academics, speakers, and artists who shared their expertise made it rewarding for thousands of theatergoers, who went away with far more than their theatre stubs.”

A decade in, the “experiment” had proven a success: The humanities had secured a place in the everyday life of Alabamians. By 1985, we’d brought more than $1 million in federal funding to Alabama for communities and nonprofits to put on their own culturally rich events. And our original programming would only continue to grow. In fact, we were so busy, it appears our tenth anniversary might have snuck up on us; it passed without fanfare. Instead, we celebrated our eleventh year with a grand reception and dinner that coincided

with an Oktoberfest celebration at Birmingham’s historic Sloss Furnaces. (The only disappointment that night? The Pete Seeger concert had to be canceled, reasons unknown.)

In 1987, Robert C. Stewart took the reins as Alabama Humanities’ third executive director. He would remain in that role for 25 years. Over the course of that quartercentury, Stewart would oversee a steady expansion of our work, helping us reach more Alabamians than ever before, including some of AHA’s most well-known programs that are still offered today.

AHA’s Making Alabama bicentennial exhibit celebrates the state’s 200th birthday. It travels to all 67 counties over a three-year period, sharing Alabama’s rich and complex story.

With the Alabama Peace Officers Standards & Training Commission, AHA offers Humanities & Law Enforcement; officers learn about the “Scottsboro Boys” case and its relevance to their work.

2018

AHA takes on Alabama History Day, empowering students to research topics of interest and creatively present their findings. Teachers use AHD as a dynamic, projectbased learning tool.

AHA awards $1.3 million in federal COVID-19 relief and recovery grants to community cornerstones like libraries, museums, and more — helping to save or create 559 jobs statewide.

Historian Wayne Flynt has been part of AHA’s work from the very beginning. Photo by Jonathon Kelso.

AHA has often been called upon to commemorate Alabama's history. For the state's bicentennial, in 2019, our Making Alabama exhibit toured all 67 counties. It offered more than 100,000 visitors the chance to learn about our shared past — and consider our shared future.

“TO

BE HUMAN means to have both a sense of the tragic and a sense of humor. It means to be willing to live between tears and laughter, often flinching at the profundity of evil and suffering in the midst of life, yet never allowing such pain to eradicate the joyous grin that comes also from the very heart of things…To wit, to be human means to be able to live with our feet on the ground and our heads in the heavens. It means to live as creatures who know at once the grit and the grandeur of life, and see both as part of a pattern that we can ultimately neither control nor comprehend. It means to see in the lives and works of others, and in our own life and work,

glimpses of truth…that illuminate the rest of the way.”

—John

In 1987, for instance, we started what’s now known as the Road Scholars Speakers Bureau — a beloved storytelling program that’s most often utilized in libraries in every county of the state. In 1989, it was the Alabama Humanities Awards that took flight. Known today as the Alabama Colloquium, the annual event honors those Alabamians who most significantly use the humanities to impact our state, nation, and world.

Our teacher workshop series, begun in 1991, has impacted countless thousands of

Alabama’s teachers and students. Meanwhile, AHA’s partnership with the Smithsonian Institution, which harkens to 1997, still brings national traveling exhibits to the state — affording Alabamians the chance to consider how their communities connect to America’s broader, ever evolving, story. And in 2008, in collaboration with Auburn University and many other groups statewide, we went live with the digital Encyclopedia of Alabama.

Historian Wayne Flynt, Ph.D., who has been a scholarly collaborator and cherished friend for the entirety of AHA’s existence, served as the site’s founding editorin-chief. Upon its launch, he called the EOA “the most expansive and ambitious intellectual collaboration in state history.”

“For the first time in the state’s history,” Flynt asserted, “we [are writing] the major narrative of who we are, what we believe, how we have lived, and what we

Final (maybe!) name change to Alabama Humanities Alliance, affirming AHA’s commitment to cultivate allies and reflecting our diverse range of programs.

AHA’s first “post-pandemic” public event brings out nearly 700 people in Montgomery to honor our newest Alabama Humanities Fellows, Bryan Stevenson and the late John Lewis.

2023

Healing History launches with a new approach for Alabamians to talk, and listen, to each other. The goal is to use conversations about our past to build a better future for all, today.

AHA celebrates its 50th anniversary — and looks toward its next half-century of nurturing a smarter, kinder, ever more vibrant Alabama.

Kuykendall, former AHA scholar and Auburn University professor of religion, speaking at AHA’s 1983 Alabama History and Heritage Festival

have accomplished. We tell the story, warts and all. But we depict the beauty as well as the pollution, the dreams as well as the failures, the triumphs as well as the disasters.”

Thicket clearers

In 1985, when we published Clearings in the Thicket, the title choice was deliberate. It comes from Alabama historian Malcolm C. McMillan. In his 1975 text, The Land Called Alabama, McMillan writes: “Alabama is named for the great river which drains its center. The river in turn received its name from the Alabamas, an early tribe which once lived on its banks at or near the present site of Montgomery. The name Alabama is of Choctaw origin and means ‘thicket clearers.’”

Thicket clearers.

When we’re doing this thing right, that description can apply to the humanities, too. A past version of our mission statement, from 2004, expressed the humanities’ thicket-clearing potential this way:

“The study of the humanities — of history, literature, philosophy, languages, and the like — does not solve life’s mysteries but does offer ways of interpreting the world in which we live. By exploring the history of our community and nation, we discover a sense of place.

By reading and discussing literature, we recognize characters who remind us of people in our own lives. By asking questions about how society ought to treat its members, we deepen our own understanding of social justice.”

Clearing the thickets.

Fifty years on, that’s what the Alabama Humanities Alliance remains committed to doing — helping us all better understand the world around us, our neighbors, ourselves, a little bit better. All through the simple yet profound act of sharing our stories.

Dive deeper into AHA’s history.

Check out a package of online extras that look back on additional moments from our past that have had a lasting impact.

Alabama voices, American stories

Roy Hoffman on the power of sharing our stories

by Roy Hoffman

“The Dance” (woodblock, 2015), by Katie Baldwin.

Each of us has a story to tell. Here’s an outline of mine: Born and raised in Mobile, Alabama, in the 1950s and ’60s, Jewish, novelist and journalist, lived in New York City for twenty years before returning to Mobile Bay with my wife and daughter, sociable, optimistic, a curious journeyer, politically engaged.

There’s much more, of course, and not just about me. “I contain multitudes,” as Walt Whitman wrote — we all do — the generations that gave rise to us, the people we love, the stories in our DNA.

Sharing those stories — both to tell and to listen, actively, empathetically — is a moral act. “You never really understand another person until you consider things from his point of view,” Harper Lee’s Atticus tells Scout, “…until you climb in his skin and walk around in it.” We do that through stories.

Exchanging them is freeing, too. There’s the “I,” “me,” “mine” — the eternal confines of self — then there are the eight billion other people on the planet. Who are they? Listen up!

I’ve been privileged, as a writer, to hear countless stories from some of our best voices.

In Albert Murray’s Harlem apartment, in 1997, in conversation about his memoir, South to a Very Old Place, I was swept away by his tale of growing up in Magazine Point, Alabama, along the Mobile River in the community known as Africatown — the juke joints that propelled his love of blues, the books, including Faulkner, Mann, fairy tales, and mythologies, that inspired him. With letters from Ralph Ellison on the desk — they’d corresponded since becoming friends at Tuskegee, and he was organizing a book — Murray told me how, before ever leaving home, he’d traveled far: “When I got to third grade and had a geography book, I could see it. It wasn’t like I was outside of the world. I was part of the world.”

In Sena Jeter Naslund’s study in Louisville, Kentucky, with the manuscript of her 2001 civil rights novel, Four Spirits, stacked on the table, she recalled when she discovered story magic. She’d been ten years old in Birmingham, 1953, on a sweltering afternoon, shivering as she read Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie. “I realized I was trembling,” she recalled. “I thought, ‘It’s these words that make me feel this way. I’d like to do that one day.’”

In 2024, over a seafood lunch in Fairhope, Alabama, near my home, Howell Raines spoke to me of his familyrooted Civil War history: Silent Cavalry: How Union

Solders From Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta – and Then Got Written Out of History. Throughout his stellar career — Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, former executive editor of The New York Times — Raines had “saved string,” an old-school reporter’s term, determined to “keep searching, keep seeking,” the facts that told of Alabamians who had supported, and fought for, the Union, including forebears from Winston County. These soldiers, who did not fit into the mythology of the Lost Cause, as he explains it, were erased. “History is not what happens but what gets written down, shaped by who’s holding power,” he said. Silent Cavalry, a combination of memoir, history, and archival sleuthing, is intended to “show the rest of the story … a big piece of rounded Alabama.” Raines reminded me how stories can unearth secrets, empower and galvanize us, to reconsider long-held beliefs.

Stories are democratic. We all have a big, overarching one to tell — and countless others, perhaps about the time a hurricane thrashed our home, or when we felt spiritually uplifted, or shook the hand of a hero.

There are celebratory stories. In Mobile’s Toulminville community, Herbert Aaron Sr., many years ago, showed me a display of trophies awarded his son for his baseball prowess, and told how Henry — soon known to the world as Hank Aaron — came of age at the playground across the street. “When Henry was a boy,” he told me, “I couldn’t keep a ball out of his hands.”

Traumatic stories reverberate with their own terrible force. In 2010, I sat in a coffee shop in Eight Mile, Alabama, while a mother, Mildred, wept to me about her Air Force son, David, killed in Afghanistan when a Taliban rocket-propelled grenade hit his helicopter. I wrote up the details of David’s young life, his valor and sacrifice, and the news-obit appeared on the Mobile Press-Register’s front page. Mildred sent me a note of gratitude that her son’s story, however fleeting, had public recognition.

Dauphin Street, Mobile, around the turn of the 20th century.

As the grandson of Eastern European Jews who opened a store in Mobile’s downtown in the early 1900s — with their neighbors speaking Yiddish, Polish, Arabic, Spanish, and Greek — I’m attuned to the global South, the profoundly American stories within the Southern ones. In my novel, Chicken Dreaming Corn, inspired by my grandparents’ world on Mobile’s Dauphin Street, memories from Romania to Lebanon to Cuba press in on the hard-working dreamers intent on providing an unbounded future for their children. “Read this novel to find, from Europe and the past,” said Harper Lee of this book, “some of the best aspects of our Southern heritage.”

In much of my fiction, largely rooted in Alabama or the Gulf Coast, characters are often, in their hearts, caught between places, as in The Promise of the Pelican, set on Mobile Bay but stretching far beyond. Hank — a child Holocaust survivor from Amsterdam, retired Alabama lawyer in his 80s who just wants to fish on Fairhope Pier — is entreated to defend Julio, a Honduran worker at a bayside resort, accused of murder. The men’s stories, increasingly intertwined, are shaped by flashbacks of childhood traumas, what it means to be an immigrant, perceived as “the other,” and the quest for justice. Stories are rich everywhere, but returning to the South

in my forties, after residing in Manhattan and Brooklyn since college, attuned me to those of my birthplace, transported by the stories of my father, Charley Hoffman, above all, then all those unfolding around me.

In fractious times, the optimist in me believes stories can even bring us back together as a culture. “The key,” I wrote in an essay on politics and civic discourse, is for folks “to try to engage … with people with other points of view. We might not share common ground, but we inhabit it, often for generations.”

Narratives, after all, are part of our legacy.

As I wrote in my essay book, Back Home: Journeys Through Mobile: “When buildings are leveled, when land is developed, when money is spent, when our loved ones pass on, when we take our places a little further back every year on the historical timeline, what we still have are stories.”

Roy Hoffman is the author of four novels and two nonfiction books, and has written for outlets such as the Mobile Press-Register, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times

AHA’s own storytellers

Back in 1987, Alabama Humanities coordinated the state’s commemorations for the U.S. Constitution bicentennial. One of our ideas at the time: Enlist scholarly experts on Constitutional history to travel the state and speak at different festivities.

From that seed was born the Alabama Humanities Speakers Bureau, better known today as Road Scholars, our longest-running program. Today, the Road Scholars Speakers Bureau boasts some 35 scholar-storytellers. They are professors, poets, artists, authors, musicians, historians, archivists, folklorists, and professional storytellers. They travel to libraries, museums, historical societies, and community centers — offering more than 100 presentations on everything from state history and culture to sports, music, art, religion, film, and more.

“There is not just one single kind of human experience,” says Dolores Hydock, a storyteller, an actor, and a Road Scholar for more than two decades. “If we hear different stories from different voices across different moments in time, we can begin to sense the larger story of what it is to be human. I once heard a wise

storyteller say, ‘All stories have the same message: You are not alone.’”

Peggy Allen Towns, one of AHA’s newest Road Scholars, agrees. A historian and author, she’s conducted extensive research on the African American community in her Decatur hometown.

“My hope,” she says, “is that by telling our stories, we are not only informed about where we’ve been; but united, inspired, enriched, and empowered to spark flames of hope, to value the contributions of all, to engage in constructive dialogue, and work together to improve the lives of all Alabamians.”

Readers

2024 Alabama Humanities Fellows

Something to say

We have tossed around quite a few definitions for our Alabama Humanities Fellows awards since we first began bestowing them, in 1989. We’ve gone the highfalutin route, proclaiming them for individuals who have made “exemplary contributions to public understanding and valuing of the humanities.” Other times, we’ve streamlined that to “people who make Alabama a smarter, kinder, more vibrant place to live.” Both are true. But what we wind up saying most often now is that, at its heart, this honor is for Alabamians who challenge us to examine what it means to be human. And who help us see the humanity in each other. That description certainly applies to this year’s roster of Alabama Humanities Fellows.

Brittany Howard. Jason Isbell. Rick Bragg. Roy Wood Jr. Two musicians. An author. A humorist. Standard-bearing storytellers, all. These are four Alabamians who have been shaped by their deep roots in this state. Howard’s and Isbell’s rural northern Alabama. Wood Jr.'s West End of Birmingham. Bragg’s Piedmont foothills. Yet they also have each, in their own way, done some shaping of their own. As the following profiles reveal, this year’s honorees know how to deliver hard truths while still seeking what Cassandra King calls “the commonality in our stories.” These Fellows urge us to look beyond ourselves, at a past and a present that aren’t always tinted rose. “Look close,” as Caleb Johnson writes in his essay on Jason Isbell. “It might not feel comfortable, but I promise you’ll see the beauty among the blight.”

Brittany Howard | 2024 Alabama Humanities Fellow

STAYING HIGH ON THE MUSIC

by Charlotte Teague

On a quiet evening while driving on a dirt road in rural Alabama, my mother mentioned Brittany Howard.

“Who is she?” I asked.

“She’s a singer from Athens, and I think she’s so pretty.”

“What’s her music like?”

My mother looked at me, and said, “It’s loud, but it whispers; it’s outrageous, but beautiful.”

This short conversation started my fascination with Howard, the Grammy-winning, song-writing, free-living, and soul-stirring musician whose Athens upbringing took place not far from my own in Hillsboro, Alabama. I quickly came to understand that her music tells the story of our shared Tennessee Valley homeland. Where, as Howard sings, the “tomatoes are green and cotton is white,” a place of “honeysuckle tangled up in kudzu vine,” but also where racial tensions persist: “I’m one drop of three-fifths, right?”

“The magic of much of Howard's music encapsulates all that we know and love about northern Alabama."

In 1854, Henry David Thoreau composed his most famous work, Walden, an artistic reflection about simple living and a full life: I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and

see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

These famous words can also characterize the life of Brittany Howard. Like Thoreau, she, too, wants to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life. And she knows all too well what Thoreau meant when he wrote he wanted to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it.

With Howard, there’s always a striving for joy, even amidst the meanness of life. When you consider that she lost her childhood home to a lightning strike and her sister, Jamie, to a rare eye disease, you can understand where a lyric like “you gotta hold on” comes from.

Brittany Howard teaches us how to “Stay High” on the magic of the music. The Limestone County native has become a hometown hero for her music that shows the world who we are here in the Tennessee Valley.

From her famed start with the Alabama Shakes to her solo career, her music is a magic carpet — moving audiences through clouds of time and joy, sorrow and pain. Telling stories of humanity, love, grit, and home, awakening souls and opening eyes to the sky, to nature, to abundance, and to living without regret, reminding us that there is a rainbow — a promise of a better life for us all on the other side of the alarm clock, the time clock, and tomorrow. Quieting that voice that wants to be loud and torture us about all that is not the best in our lives, but pushing us to be our best selves, asking the question in song: “What Now?,” believing and not believing, and

hearing the answer in another song, “I’ll prove it to you.” This is how Howard shares herself and hugs us through her music.

Her music shows that we are connected to one another. There may be mountains, miles, and time between us, Howard concedes to someone in “Short and Sweet.” But there’s also plenty to bind us. As she sings in “You Ain’t Alone” — “we really ain’t that different, you and me.”

The magic of much of Howard’s music encapsulates all that we know and love about northern Alabama. The music is front porch waving, hop scotch stepping, moonshine drinking, tambourine playing, old story time telling, Athens State fiddling, and meeting on the street blowing car horns: hugging and holding up traffic.

It is love wrapped in lyrics — in a gift box for us all to hear and behold. It blesses my heart and yours, and the music beckons us to come closer and sit around a warm fire of loving and living life. Her music uplifts

and transforms through the power of all that we know about our past; after all, according to Howard, “History Repeats.” As a daughter of northern Alabama, I, too, understand what this means; but her music reminds me of possibilities, so I touch the music to dream.

Yes, like Howard, I, too, just want to “Stay High.” To “smile and laugh and jump and clap, and yell and holler and just feel great.” And holding on to that joy is easier when you listen to Brittany Howard. Her guitar, the voice, the lyrics — all fresh air, sunlight, innocence, and fireworks. The music keeps us hopeful. She tells the stories — her stories and our stories — through her sound, and we listen with our hearts, minds, and souls, seeking connection and freedom. It’s magic, and it’s how we stay high, together.

Charlotte Teague, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English at Alabama A&M University.

Jason Isbell | 2024 Alabama Humanities Fellow

WHERE DO YOU

COME FROM?

by Caleb Johnson

When I was a student at The University of Alabama, seeing bands was an aspirational experience. Not because I harbored any illusion of becoming a musician. I knew back then that I wanted to make something, and whatever resulted would likely have its foundation in my home state because, well, that was all I really understood of the world. I never dared to call this dream art; nobody where I come from made art. However, a relative noticed this urge and introduced me to the Drive-By Truckers. Their songs cracked open my head, my heart. In particular, the narrative-driven tunes written by Jason Isbell, who was in the midst of a well-documented tenure with the band. I became even more captivated by them when I learned that he, like myself, came from an unincorporated rural community in north Alabama.

“That's what Isbell's songs say: Look close, it might not feel comfortable, but I promise you'll see beauty among the blight."

Green Hill, where Isbell comes from, has the advantage of being located near Muscle Shoals and its rich musical history, though there was also a time not so long ago when said history was forgotten outside the Quad City area. Before the documentary Muscle Shoals, before Isbell became a movie star himself. I imagine a younger

Isbell had to work through the geography of answering the loaded question — where do you come from? — by first hoping someone knew where was Muscle Shoals or, God forbid, Green Hill. When I was growing up in Arley, a lakeside community in Winston County, classmates used to say they were from Jasper. It was easier to lay claim to the nearest town of any size rather than explain where was Arley exactly. Or better yet what was Arley, and what did it mean to come from there.

It is impossible for me to consider what it means to be human without considering place. I’m not an academic, despite what my day job implies; I’m a fiction writer, which means I put stock in symbols and rely on magical thinking. It seems reasonable to me that we share more than just proximity with the dirt upon which we trod and the air that we breathe. There must be something happening at the cellular level. I can’t help thinking that Jason Isbell would not be Jason Isbell were he not from Green Hill. I know were it not for his origins there he never would’ve written the masterpiece “Decoration Day,” which tells the story of a local feud between the Lawsons and the Hills. I suspect Isbell could’ve continued writing cinematic songs such as this one for as long as he wished. But he didn’t just do that, because he is an artist, and being an artist means refusing to settle for what comes easy, remaining curious about the world, and striving to connect with others, as well as your past and present self.

Isbell certainly refused to settle when writing his breakout solo album Southeastern, and it catapulted him into popular culture. I remember once, not long after Isbell left the Truckers, seeing him play at a bar in Tuscaloosa best known for yellowhammer cocktails served in plastic cups. You could count on two hands the number of people in the room that night. Hearing Isbell’s songs live was, for me, like grabbing ahold of an

electric fence. Later, I felt protective over his growing popularity, especially as the conversation around his music urged a reckoning with rural, white working-class Alabama. A reckoning that never happened, at least not in the arts, but one that reaffirmed our stories matter.

Of course they do. To believe otherwise is to buy wholesale a lie, to accept that some bogeyman is to blame for our current socioeconomic station, for our jealousy, for our bitterness, for our lack of self-worth — rather than look in a mirror. That’s what Isbell’s songs say: Look close. It might not feel comfortable, but I promise you’ll see beauty among the blight.

There was a time, not so long ago, when it was much harder to find complex representations of rural Southern folks in our culture’s nooks and crannies, let alone out in the open. There was no “Outfit” or “Speed

Trap Town” or “White Beretta,” or the many other working-class songs spread across Isbell’s eight studio albums of original material. Forget stories about what it means to stay and make a life, which Isbell has done personally and professionally.

Not so long ago, if you as a Southerner felt, say, apart — then you wanted to leave. You dreamed of getting far, far away. You had to go searching for a place where you felt like you belonged. Many understandably still do. But thanks to artists like Jason Isbell, it’s a little easier to imagine that place right here, then work to make it so.

Caleb Johnson is the author of the novel Treeborne (Picador), which received an honorable mention for the Southern Book Prize. Currently, he teaches creative writing at the University of South Alabama.

Rick

Bragg | 2024 Alabama Humanities Fellow

HIS GRITTY

GRANDEUR

by Cassandra King

In the prologue of Rick Bragg’s stunning memoir, All Over but the Shoutin’, Rick writes that it’s not an especially important book, simply the story of a strong woman, a tortured man, and three sons who lived “hemmed in by thin cotton and ragged history in northeastern Alabama.” Rick claims that his is a story that could be told by anyone, with this addendum: anyone with an absentee father who drank away his finer nature and a mother who sacrificed so her sons could rise above the poverty and degradation of their upbringing. Although the author admits that it’s a story that needed to be told — deserved to be told — he argues it isn’t really important to anyone but his family and the others in their orbit who lived it, friend or foe.

I, for one, beg to differ. And I can say with a clear-eyed certainty that I speak on behalf of a vast multitude of devoted Rick Bragg readers. I would even argue that Rick’s works aren’t just important, they’re the essence of why we need the bond of storytelling today more than ever.

“Rick's works aren't just important, they're the essence of why we need the bond of storytelling today more than ever."

Rick wrote Ava’s Man as the story of his maternal grandparents. In his endorsement, Larry McMurtry called it a book of a certain “gritty grandeur.” High praise indeed, from a master. To me, McMurtry

was acknowledging that Rick’s works aren’t merely picturesque, tragicomic tales of those who have been called hillbillies, peckerwoods, rednecks, even po’ white trash — the mill workers, cotton pickers, bootleggers, tenant farmers, and vagabonds dragging their ragtag families here and there, chasing the dream of a better life. Nor are they stories for the holier-than-thou to relish, with smug gratitude that their families never faced such degrading circumstances. Gritty and grim, true; but beyond that, these tales reveal the steely courage it takes to overcome even the most difficult obstacles life throws our way. And the grandeur? That comes in the telling, the magnificent tribute paid to those unheard voices by giving them a venue to have their say, to tell their stories.

This was made true for me in a whole new way when I first met Rick Bragg. Many years ago, my husband Pat and I visited him at his mother’s farmhouse near Jacksonville, Alabama. Pat had received an advance copy of Shoutin’, which moved him so deeply he not only endorsed the book but also sent flowers to Rick’s mother, Margaret. I brought her half a chocolate cake (another story, for another time). Just as Pat and I arrived, Rick came varooming up the driveway in a racy sports car, his arm hanging out the window. As soon as he slung himself out of the car and drawled a greeting, I knew him. We’d never met, but — as we say in the South — I knew his people.

The lower Alabama of wiregrass, peanut farms, and sandy fields where I was raised is a different world than Rick’s Appalachian foothills. Our vernacular differs, but we still understand each other. Both of us have eaten purple hulls, tea cakes, and field-dressed quail. We have kin who were washed in the blood of the Lamb; we celebrate buck dancing, banjo picking, and the Crimson Tide. There is a commonality in our stories, in the way

the past has formed who we are and how we got here. No Southern storyteller can truly tell the tales of his or her life without delving into the past.