The Architectural Puzzle

Karnak TempleAR6001 Dissertation

Alaa Hendi | K1617842

Kingston University London

BA (Hons) Architecture

AR6001 - The Practice of Reading Architecture

6900 word Illustrated Dissertation

Alaa El Din Hendi

K1617842

8th January 2019

Tutor: Michael Lee

Introduction

History

Alignment of the Sanctuary

The Quay and The Avenue of Sphinxes

Pylon 1 and the Frames of the Sun

Forecourt

The Temple of Ramesses III

The Temple of Khonsu

Introduction

Karnak Temple was known as “Ipet Resyt” during Ancient Egypt, which translates to “The Most Sacred of Places”. The temple is situated in Thebes; now modern-day Luxor, in Upper Egypt on 100 ha of land. The temple of Karnak allowed Thebes to become the capital of ancient Egypt during the Middle and the New Kingdom because of the massive cult following of Amun. Karnak temple is located southwest of the Nile River, and was close to the eastern desert of Nubia which was used as a trade route for mineral resources.

Karnak is a combined mixture of temples, chapels, pylons and avenue of sphinxes. The temple is unique for its massive size and its long period of construction. It took approximately 2307 years (between the years of 1991BC to 395AD) to build. Karnak symbolised the change in ideology, culture and religion through time, as it was constantly destroyed and rebuilt by different pharaohs and kings throughout the middle kingdom to the end of the Roman occupation of Egypt.

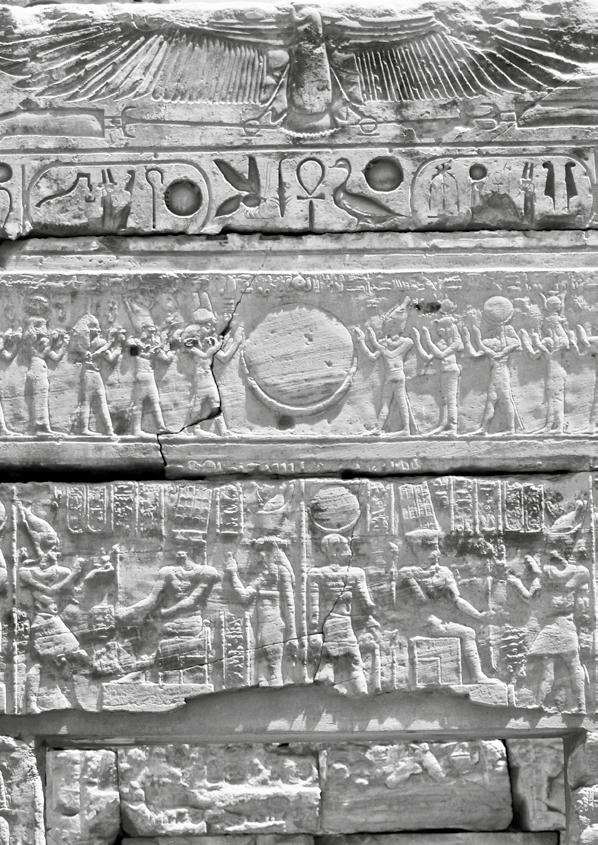

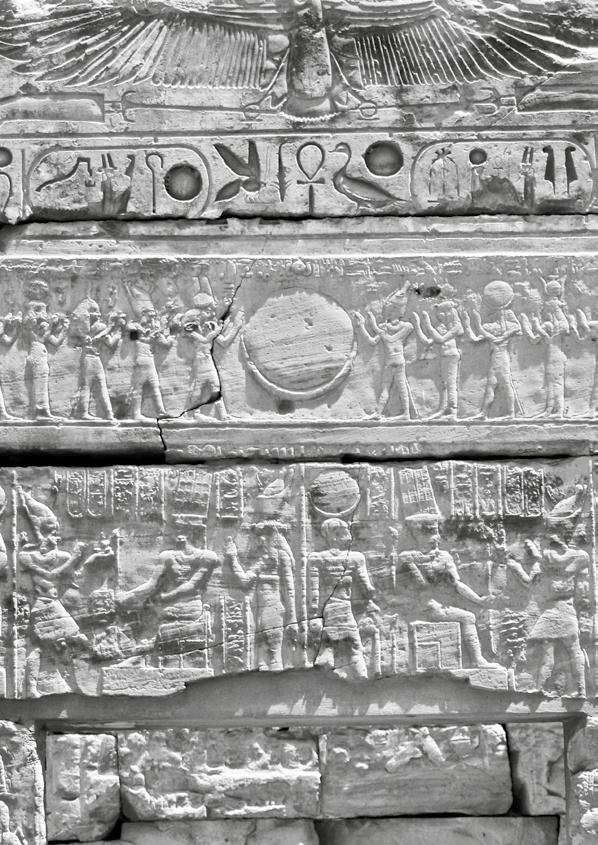

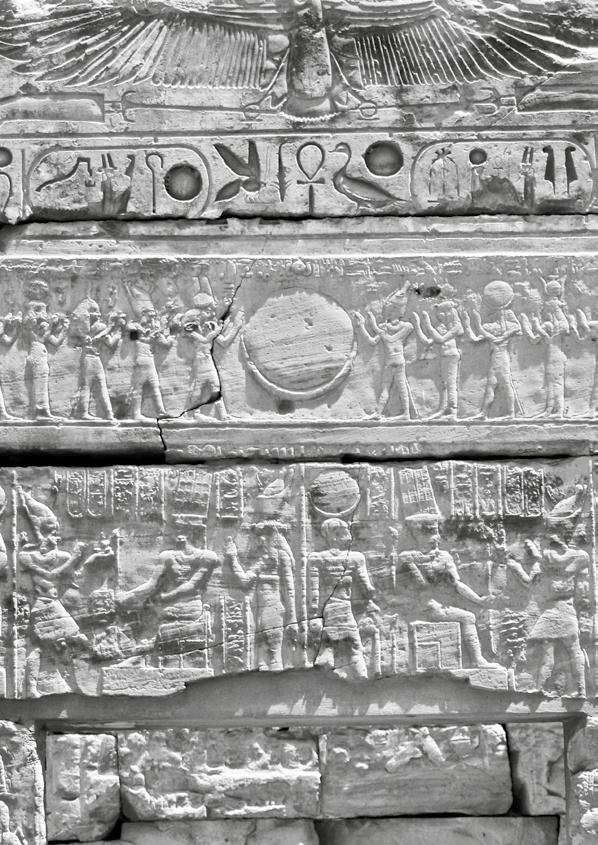

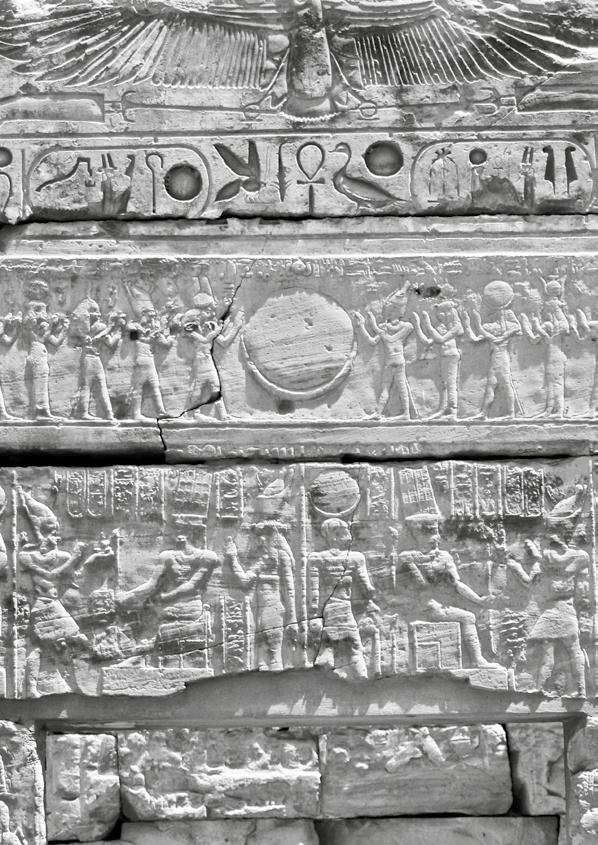

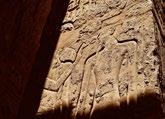

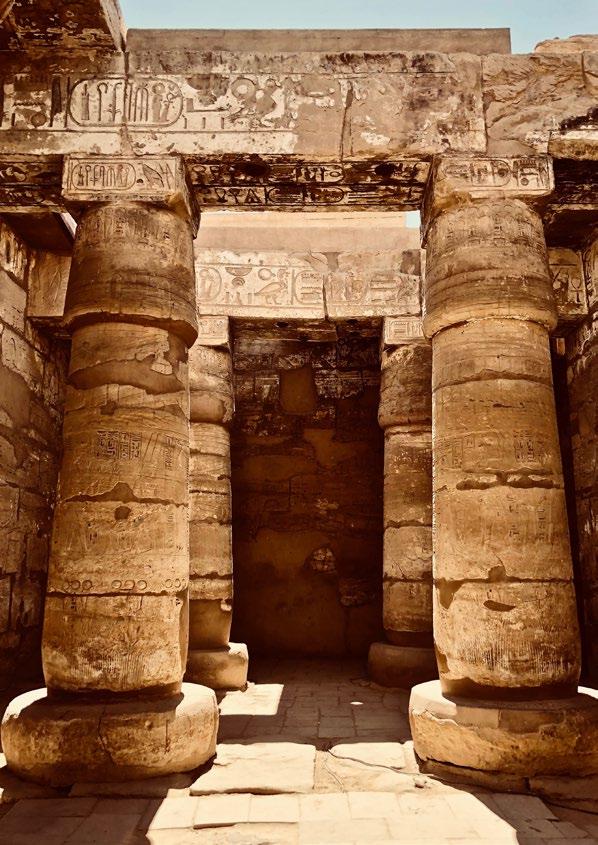

Buildings such as Karnak were built to last forever, as deities such as Amun were regarded as living entities that protected the cycle of life. The colossal size of the densely packed size of the Hypostyle Hall was intended to make humans feel small, and to represent the difference between the capability of the deity and the human (Phillips and Janssen, 2002, p.g 2). The sanctuary’s interior decorations are a “pictorial record of the complicated ritual of an Egyptian temple” (Smith, 1978, p.g 169). The interior roofs were decorated with hieroglyphics of stars and “zodiacal designs” that symbolize the heavens (Elliott, 2012, p.g. 10). This, in turn, developed the ideology of what Blyth, 2006 described as “heaven on earth” (Blyth, 2006, p.g. 1). The temple of Karnak represented the difference of social status in ancient Egyptian society, as only highrank officials can enter and participate in rituals conducted by the pharaoh. In addition, due to the dimensions of the entrance pylons only “the privileged minorities can see what lay within “(Phillips and Janssen, 2002, p.g. 3). As stated by Snape, 1996 the outer walls of the temple would be used to advertise the royal propaganda through a serious of relief. The pharaohs would by often illustrated annihilating the enemies of Egypt (Elliott, 2012, p.g.10) as “king acting as king in the sight of gods and men is important” (Snape, 1996. p.g 33). Overall, these hieroglyphic decorations are symbolic and written documentation of the privileged minority of the “Ancient Egyptian cosmos” (Elliott, 2012, p.g. 10).

The temple of Karnak whilst still remaining a “bewildering architectural puzzle” (Weeks, 2005, p.g. 67), most of its monuments are poorly preserved. This is due to water and wind erosion, and earthquakes that destroyed large parts of the temple. However, engineers throughout the years were able to restore many parts of the sanctuary, most of the temple still remains uncultivated in the sand. Nonetheless, due to its size and history, the complex was economically and ideologically considered the most reputable temple in Ancient Egyptian architecture. According to Baines and

Málek, 2005, P.g. 90 “no site in Egypt makes a more overwhelming and lasting impression than this apparent chaos of walls, obelisks, columns, statues, stelae, and decorated blocks”. To this extent, in just only the supremacy of Ramesses II the temple received an approximate of 31,833kg of gold, 997805kg of silver, 2,395120kg of copper, 3722 bolts of cloth (Week, 2005).

Whilst Karnak temple is the 2nd most popular tourist attraction in Egypt, it is something that I know very little about. Thus, this research will be giving me an opportunity to learn more about my country’s architecture and past. In addition, from previous studies of the Pyramids of Giza, I learnt that the Egyptians were masters of geometry and construction that was ahead of their time. Consequently, this has heavily influenced my architectural proposals throughout my undergraduate studies. One of the elements that I find interesting in Karnak is the hieroglyphics that are adorn on the walls of the complex, which tells the stories of the previous rulers of Egypt.

Through this essay, I will be exploring the main historical events that shaped the temple, the quay, the avenue of sphinxes, the temple of Ramesses III, the temple of Khonsu, the great Hypostyle hall and the obelisks. In addition, I will be discussing the temple’s alignment in which it was built by using some of Norman Lockyer’s theories, the possible construction methods that the royal builders used, and how it connects to architectural theories such as “A Pattern Language” By Christopher Alexander, “An Essay on Architecture” by MarcAntoine Laugier and “The Sacred and the Profane” by Mircea Eliade. Furthermore, I will also attempt to find a correlation between the temple and the philosophical ideology of axis mundi.

Pharaohs and kings of Egypt across time helped shape the sanctuary of Karnak to what it is today. Across many different generations of pharaohs, the temple was competed by one king after another; by “enlarging, enriching, adorning, replacing” (Blyth, 2006, p.g. 2). This however, led to the demolition of some of the past tributes of previous kings, as each king competed in honouring the sun god Amun (Blyth, 2006, p.g. 1-2). Figure 2 displays the final floor plan of the sanctuary.

The origin of Karnak temple can be traced back to the Old Kingdom in 2700- 2055 B.C, due to antiques that date back to the pre-dynastic period of Egypt being excavated from the site according to Blyth, 2006. However, no reliable evidence was discovered to indicate when it was first constructed. Well documented evidence of Karnak temple surfaced around the Middle Kingdom in the year 1971 B.C. where King Sensusret I’s Middle Kingdom court played a huge role in placing Thebes and Karnak as the mecca of the religion of the solar cult of Amun in Egypt (Blyth, 2006, p.g. 7).

After the end of the Middle Kingdom, and the new focus in the city of Thebes, due to the development of the Karnak, Egypt saw an increasing number of followers of the cult of Amun in the New Kingdom 1570-1070BC. As a result, most of the well-known developments of the temple were established around this period. King Thutmose I continued the legacy of King Sensusret I by solidifying Thebes as the capital of his realm, and renovating the Middle Kingdom shrine. The pharaoh built a colonnaded court, and decorated the entrance of the Shrine with status. Furthermore, Thutmose built two pylons to the west, and then erected a hall with columns of cedars between them. However, when Thutmose’s daughter Hatshepsut became the queen of Egypt, she along with her architect Senmut altered the interior of the hall of cedars, by removing the central roof of the hall. She then built two large obelisks in between the row of cedars that surpassed the height of the surrounding colonnades. Moreover, after the death of the Queen of Egypt her step son Thutmose III took the throne. He held a grudge towards the former queen. So, he reduced her towering obelisks by covering them to 2.4 meters leaving the remaining height to project above the roof. In addition, the young king built two halls between pylons 5 and 6. Then approximately twenty years later, he enlarged the temple towards the east, by constructing a Festival Hall. A hundred years later, the pharaoh Amenhotep III built a pylon towards the entrance, and a courtyard west of the temple of Karnak. Furthermore, he constructed an avenue of ram headed sphinxes dedicated to the god of gods Amun (Smith, 1978, p.g. 161). Approximately sixty years after the ruling of the king Amenhotep III, King Ramses I aspired to surpass the previous rulers of Ancient Egypt, by decorating the house of the gods with pylon 2. Also, he began the construction of one of Ancient Egypt’s greatest architectural achievements; the Great Hypostyle Hall. Amenhotep didn’t live to see the finished construction of “the largest columnar hall in the world” (Smith, 1978, p.g. 163). It was passed down to his son the pharaoh Seti I who ruled from 1291 to 1278 B.C, and later to

Karnak Temple King Ramses the II who initiated the decoration of the pillared hall. Then finally, it was completed by Dynasty XX’s Pharaoh, Ramses IV (Smith, 1978, p.g. 163).

The third Intermediate Period of Ancient Egypt that lasted between 1069-525 B.C marked the shift in political powers, and a rise of political unrest. However, architectural development for the cult of the sun god of Karnak was still being produced. When the XXII dynasty Libyan pharaohs took over for a short period the region of Thebes, they built the last courtyard called the Court of the Bubastis, which was larger than any extension built by any previous and future pharaohs. The construction was never completed. However, when the Ethiopian pharaoh Taharqa took the succession to the throne of Thebes from the Libyans, he finalized the forecourt. King Taharqa greatest architectural achievement in Karnak was the last and largest pylon (pylon 1) situated in the west entrance of the temple (Smith, 1978, p.g. 163). Much like the architecture built by XXII dynasty kings, it was never finished.

During the Graeco-Roman period, in the years 332 to 323 B.C, no major new constructions were made in the sanctuary. However, a few changes were made in the Karnak due to the introduction of Christianity. For example, during the Roman occupation of Egypt, Constantine the Great’s imperial engineers in 330 A.D lowered the 32m obelisk of Thutmosis III, relocating it in Piazza San Giovanni in Florence, Italy, and added a cross on top of it. In addition, during the ruling of Theodosius I, the second obelisk of Thutmosis III which was located near the seventh pylon of Karnak was re-erected in the Hippodrome in Constantinople in three parts. In the year 379 A.D under the ruling of Theodosius, he placed Egypt under a forced Christianization. This resulted in the temples of Karnak to be converted to Christian chapels. Unfortunately, this ended the construction of the temple due to the extinction of the cult of Amun (Arnold, 1999, p.g. 272).

Alignment

One of Karnak’s unique architectural features is its relationship with the way in which it is aligned. In ancient Egyptian architecture, pylons were usually oriented east-west or west to east. This produced a large framed portrait of the sun shining through the two hills of the pylons, which resembled the hieroglyph of the sun (Snape, 1996, p.g. 32). Moreover, in Smith, 1978 book he claimed that the temple’s “Growth was along the processional axis” (Smith, 1978, p.g. 161) through the use of the avenue of sphinxes that Amenhotep III built in the New Kingdom, which further supports Snape’s statement. By producing a processional axis, it allowed the sanctuary to be linked together with other temples. According to the book ‘Egyptian Temples’ by E. Smith, the processional axis connected, Karnak temple and Luxor temple; which is located two kilometres south, together. However, in the book Globe History of Architecture by Ching, F., Jarzombek, M. and Prakash, V. they produced findings that the Karnak was not axially aligned but it followed the processional route in which it connects four temples together. The map in figure 8, displays the association of Medinet Habu, the Temple of Luxor, the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut and the Ramsseum to Karnak Temple (figure 4).

Karnak, like most temples in Thebes, is positioned perpendicularly to the Nile River, which explains the west/east processional axis of the complex (Sullivan, 2008). The entrance to the Karnak today is through the west gate of the complex. However, due to the chronological order of time each monument was built, visitors have to enter through the east gate. (Seton-Williams and Stocks, 1988, p.g. 541).

Astronomers across history attempted to link the temple to astrological alignments. According to Moderson, 2007, British Astronomer Norman Lockyer conducted a study that suggested that the sanctuary of Karnak aligned with the star Duhhe and Canopus. However, that would mean that the temple is approximately 6000 BC to 6400 BC years old, which does not align with the dating of the Egyptologists. So, his study was widely disregarded. In my opinion, when new monarchies ruled Egypt, they destroyed or altered the monuments of the past, which can result to inaccuracies when dating events. Furthermore, the ancient Egyptians by the use of their temples attempted to align themselves to a great beyond outside the realm of human existence. This is supported by Eliade and Trask, 1987 statement that primitive cultures would try to connect their religious spaces to an “incorruptible celestial existence” and by Jencks, 1998 that the Egyptians placed their temples to the “propitious points of the universe. Therefore, Lockyer’s theory deserves more study.

The Quay and the Avenue of Sphinxes

When first approaching the Karnak sanctuary through the west entrance, one first walks through a 13m x 15m quay that is reached by a wooden bridge in our present day (Sullivan, 2008). But, during ancient times the quay was reached by boat through a t-shaped basin by pharaohs and priests; where the sanctuary was still surrounded by the Nile river water (Week, 2005).

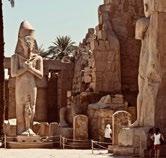

The quay then leads to an avenue of 38 ram-headed sphinxes (figure 6) known as criosphinxes that directs the visitor to the complex’s entrance. The ram headed sphinxes symbolised the god Amun who was widely depicted as a ram headed man. The avenue was used as a tool to connect the Karnak with Medinet Hebu, the Temple of Luxor and the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut during the Opet Festival. At that time, the priest and the cult members would visit the temples in Thebes to honour the god Amun and his family. From that came the avenue’s name as ‘the way of the offering’ (Baines and Málek, 2005,).

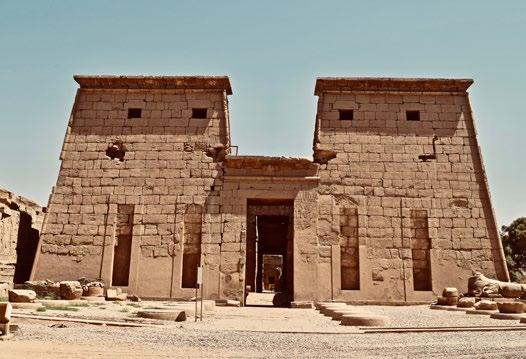

Pylon 1 and the Frames of the Sun

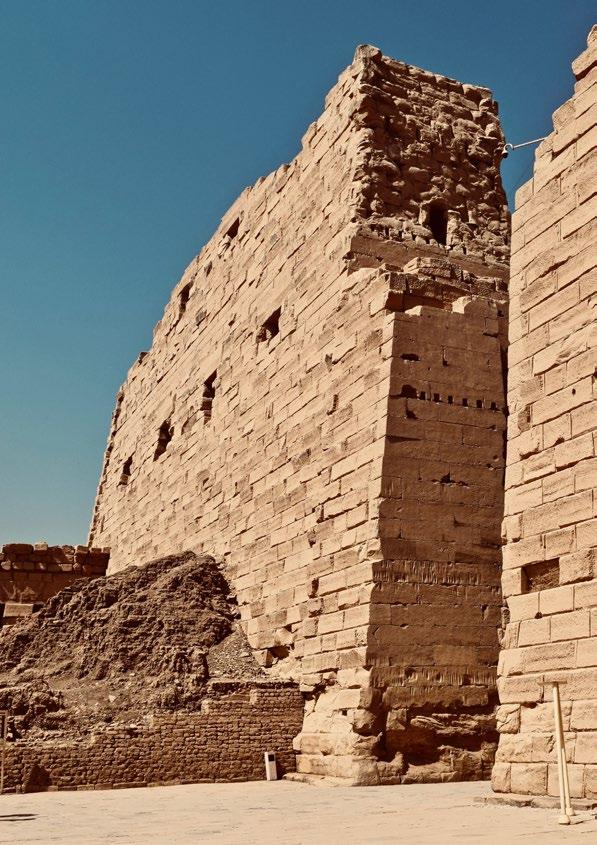

The avenue of sphinxes leads to the grandeur first pylon (figure 12). However, it was mentioned by Weeks, 2005 that it was originally planned by Sheshonk I in dynasty 22, and Nectanebo I in dynasty 30 began its construction, carvings on the walls show that it was built by King Taharqa in dynasty 25. The first pylon was never completed even though it towered at a height of 43 meters with a thickness of 15 meters, and covered a distance of 103 meters.

The main building materials used during construction of most of the monuments, specifically the pylons, were Nubian sandstone (figure 14) from Gebel el Silsila in the southern city of Aswan. The elevation of the two towers of the first pylon has eight large cut out windows with 4 slots that used to hold flagpoles carrying coloured linen banners which reached 46 meters height. In addition, there used to be a 19 meter high door decorated with sheets of gold and bronze and religious reliefs in the centre of the two towers. However, this was also later destroyed during the Ptolemaic period of Egypt. (Weeks, 2005)

The first pylon is the biggest among the ten pylons on the site. The pylons were shaped like the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic ‘akhet’ which was a symbol that depicted a sun rise, or sun set between two mountains on the horizon. According to Sullivan, 2008, this symbolized the “sun rose to start life anew each day”. Furthermore, in the book ‘Egypt Code’, Robert Bauval, 2008, discussed another theory by Norman Lockyer, that the 6 pylons in the West-East axis of the temple on two days of the year framed the sun; once in winter and six months later in summer. During the winter solstice, the pylons towards the western side of the temple framed the rising sun, while the summer solstice framed the setting sun towards the eastern side of the temple. However, Bauval disagrees with Lockeyr’s premise on the summer solstice as the pylons only framed the setting sun for a short period of time before disappearing behind the Theban Hills. Based on Sulivans quote and Bauvals discussion, we can hypothesis that the Egyptians were more interested in framing the rising sun as it correlates to the ram god’s symbolism of rebirth. In my opinion, by also looking at the floor plan (figure 2) of the religious site, the pylons gradually get smaller and smaller from pylons one to six until reaching the noam of Amun-Ra. Hence, another assumption can be made that the pylons were not just frames, but also instruments that direct the sun rays of the winter solstice into the sanctuary, so pharaohs can receive the blessings of Amun every year.

A question that is usually asked about the great pylons of the Karnak is how was it possible to construct something so large without the use of modern technology? While much of the construction techniques of ancient Egyptian architecture still remains a mystery, but due to the in-completion of the first pylon a discovery of a mud-brick construction ramp ( figure 16) was found behind the left tower remains. Weeks, 2005, explains that the ramp was assembled perpendicularly to the pylon, and the area between the mud-bricks and the pylon was then filled with rubble or sand to form a ramp. Then blocks of sandstone were pulled up using rollers or sledges and ropes.

did not always manage the unconnected features of the pylon which were prone to diminish due to their dissimilar weights. For example, in the temple of Karnak, an average size wall would be joined together with a large pylon which resulted in an increased damage to the foundations, due to the gradual movement of the ground. However, architects in Karnak temple resolved this issue by building foundations at the 8th pylon with clay, and placed it approximately 2.4 meters underground. However, in some parts of the temple the foundations were made with “inadequate materials” (Cenvil, 1965, p.g 137) such as small stones set sideways below large blocks set parallel to each other, or from leftover materials from past monuments. Unconnected squared blocks and drums of columns were set side by side shifted the ground below it consequently cracked the foundations. In the Greco Egyptian period, temples and chapels were reconstructed with more developed foundations made up of approximately 9 to 10 slabs to support the weight of the pylons and walls.

In Cenvil’s book Living Architecture: Egyptian, he outlined the many possible construction techniques used by the Ancient Egyptians in the sanctuary of Amun. Cenvil describes the foundations of the temples were made with “Great Carelessness” (Cenvil, 1965, p.g 137). The first step of the construct was to excavate a trench wider than the wall. The royal builders would then cover the trench with a thin layer of sand. This was then stabilised with a brick. Cenvil later explained that the architects at the time did not always manage the unconnected features of the pylon which were prone to diminish due to their dissimilar weights. For example, in the temple of Karnak, an average size wall would be joined together with a large pylon which resulted in an increased damage to the foundations, due to the gradual movement of the ground. However, architects in Karnak temple resolved this issue by building foundations at the 8th pylon with clay, and placed it approximately 2.4 meters underground. However, in some parts of the temple the foundations were made with “inadequate materials” (Cenvil, 1965, p.g 137) such as small stones set sideways below large blocks set parallel to each other, or from leftover materials from past monuments. Unconnected squared blocks and drums of columns were set side by side shifted the ground below it consequently cracked the foundations. In the Greco Egyptian period, temples and chapels were reconstructed with more developed foundations made up of approximately 9 to 10 slabs to support the weight of the pylons and walls.

The walls of the Karnak temple reached superhuman sizes which theoretically required many supports and joints. However, the walls in ancient Egyptian sanctuary were made by lining cheap masonry and rubble, which was considered a “dangerous” method by Cenvil. But, the royal builders fixed this issue by having an outer shell for the pylon that covered the partition of blocks lined together without mortar. Their precision in lining the masonry allowed the pylon to stand without any of the outer envelopes to collapse. In the New Kingdom, Karnak temple’s walls were layered horizontally with irregularly shaped masonry. However, this later changed in the late period where blocks were cut in standardized shapes, and mortar was used in bonding the masonry together. The blocks were later joined together with dovetail joints during the drying processes of the mortar to give it extra support (Cenvil, 1965, p.g. 141).

The walls of the Karnak temple reached superhuman sizes which theoretically required many supports and joints. However, the walls in ancient Egyptian sanctuary were made by lining cheap masonry and rubble, which was considered a “dangerous” method by Cenvil. But, the royal builders fixed this issue by having an outer shell for the pylon that covered the partition of blocks lined together without mortar. Their precision in lining the masonry allowed the pylon to stand without any of the outer envelopes to collapse. In the New Kingdom, Karnak temple’s walls were layered horizontally with irregularly shaped masonry. However, this later changed in the late period where blocks were cut in standardized shapes, and mortar was used in bonding the masonry together. The blocks were later joined together with dovetail joints during the drying processes of the mortar to give it extra support (Cenvil, 1965, p.g. 141).

The west entrance pylon is connected to the trapezoidal wall enclosure that was built by Nectanebo I. The wall encloses the great temple of Amun and both west/east and north/south axis of the complex. The wall stands at a height of 12 meters, and is approximately 8 meters thick. The enclosure wall was made of mud-brick. Mud-brick layering in ancient Egyptian architecture was a mixture of both horizontal and vertical layers of bricks. However, in Karnak there was no horizontal layers. Week, 2005 stated that the way the courses of the mud-bricks were placed was deliberate to resemble waves of water. He further added that the imitation of waves symbolised the ancient Egyptian belief that before the creation of life, the great prehistoric sea covered the earth and the area on which Karnak was situated “was an island on which the act of original creation took place”. In my opinion, this relates back to the philosophical ideology of Axis Mundi where primitive cultures assumed that the land in which they existed on is the centre of the universe and the beginning of existence. Therefore, the wall enclosure of the sanctuary can be understood as a threshold that divides and protects the people from “profane of the chaotic outside world” (Eliade and Trask, 1987).

The west entrance pylon is connected to the trapezoidal wall enclosure that was built by Nectanebo I. The wall encloses the great temple of Amun and both west/east and north/south axis of the complex. The wall stands at a height of 12 meters, and is approximately 8 meters thick. The enclosure wall was made of mud-brick. Mud-brick layering in ancient Egyptian architecture was a mixture of both horizontal and vertical layers of bricks. However, in Karnak there was no horizontal layers. Week, 2005 stated that the way the courses of the mud-bricks were placed was deliberate to resemble waves of water. He further added that the imitation of waves symbolised the ancient Egyptian belief that before the creation of life, the great prehistoric sea covered the earth and the area on which Karnak was situated “was an island on which the act of original creation took place”. In my opinion, this relates back to the philosophical ideology of Axis Mundi where primitive cultures assumed that the land in which they existed on is the centre of the universe and the beginning of existence. Therefore, the wall enclosure of the sanctuary can be understood as a threshold that divides and protects the people from “profane of the chaotic outside world” (Eliade and Trask, 1987).

Fig. 16 1:500 plan of the forecourt (by Author)

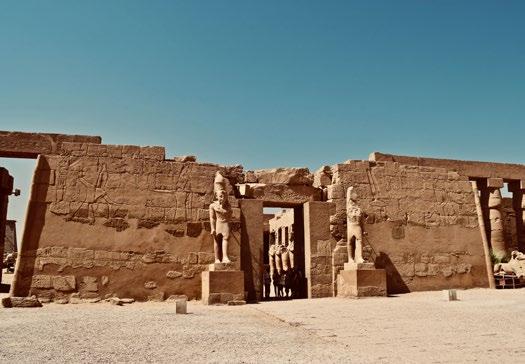

The Forecourt

After passing through the gates of the Karnak, one arrives in a large open-air courtyard approximately 103 meters by 84 meters; known as the first forecourt. In the centre of the forecourt, there remains the ruins of the kiosk of King Tahraqa, that had ten open papyrus columns which are approximately 26.5 meters high. Furthermore, towards the left of the entrance is a small shrine made of quartzite sandstone called ‘The August temple of a million years’, which was built by Seti II. It was used as a chapel to honour the Theban Triad (Amun, Mut and Khonsu) (Seton-Williams and Stocks, 1988).

During the festival season, the forecourt was one of the limited spaces that were accessible to the general public within the temple walls. While the many halls, temples and chapels were only restricted to high level priests and pharaohs to honour the deities (Sullivan, 2008).

The Temple of Ramesses III

One of the best-preserved temples in Karnak is the temple of Ramesses III, which is situated towards the right side of the forecourt. Ramesses III’s temple was called the ‘House of Ramesses Ruler of Heliopolis in the house of Amun’. The temple was built as a form of expression to display his dedication to the solar deity in his two forms “Amun-Ra, king of the gods and Lord of Karnak” and Amun Ra among his wife Mut and son Khonsu (Seton-Williams and Stocks, 1988). The north elevation of the temple features two standing statues of Ramesses III wearing both the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt. Behind the sculptures are ancient carvings that appear propagandistic. Weeks 2005 explains that it represents Ramesses before Amun holding “a mace in one hand and foreign captivity with the other” (figure 20).

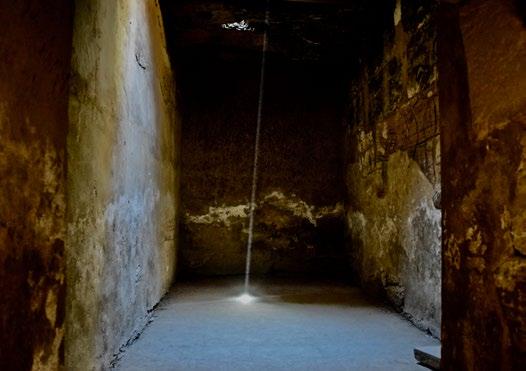

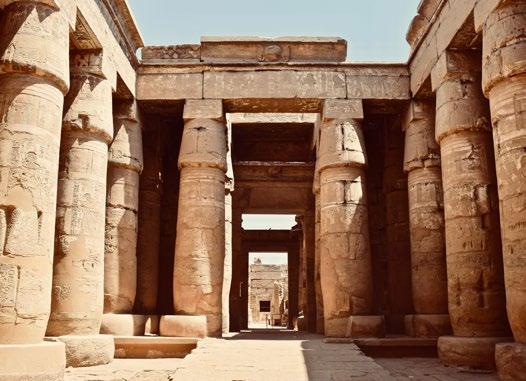

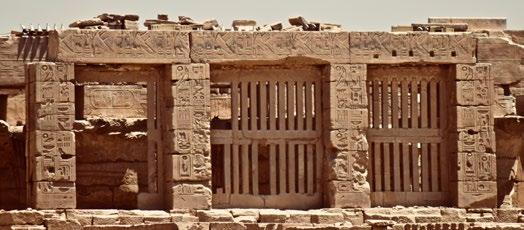

A common belief by the Egyptians is that arrangement of their temples was designed by the gods to mimic the heavens (Eliade and Trask, 1987). Therefore, the layout of the temple of Ramesses III follows that of a regular temple in ancient Egypt. As listed by Sullivan, 2008, the temple consists of an entrance pylon (figure 20) resembling the mountains similar to the larger pylons within the processional axis of the Karnak, an open-air court, a “hypostyle hall”(figure 22), a “rear sanctuary with side rooms”, and then “a central shrine” called a Noas (figure 21). Furthermore, Weeks, 2005, adds that the temple of Ramesses III contained “stone ramps in each gateway” which elevate “the floor higher” and higher. While the ceilings also become lower, and which results in the dimensions of the temple becoming smaller.

The progression of a much more open space to much smaller space through a series of gateways can be interpreted by looking at Christopher Alexander’s, 1977 “Pattern Language” about sacred sites and holy ground. He describes that by passing through a sequence of gated spaces each becoming smaller and more private than the last, this evokes a feeling of sacredness and holiness. This is further supported by Weeks, 2005, as he states that “the procession from an open, sunlit environment into increasingly more restricted, dark, silent and claustrophobic rooms reinforce the impression that one has entered a sacred place”. By looking at it in a different perspective the progression of spaces creates multiple thresholds which signifies the temples “religious importance, and at the same time vehicles of passage from one space to the other “(Eliade and Trask, 1987) symbolising the transcend to a spiritual realm.

The restriction of lighting to a singular beam of natural light that penetrates through the ceiling of the inner most part of the shrine (figure 21), further induces a feeling of seclusion, importance and that one is in the presences of the god Amun. Furthermore, the beam of light can be seen as a form of communication with the sun deity, as it signifies “a door to the world above, by which the gods can descend to earth and man can symbolically ascend to heaven” (Eliade and Trask, 1987).

The Temple of Khonsu

The temple of Khonsu is situated near the central enclosure of the south-western corner of the Karnak, built to honour the son of Amun; Khonsu. It was built by Ramesses III, however its construction began by Amenhetep III in Dynasty 18. Similarly, to the temple of Ramessess III’s, it is also one of the best-preserved temples on the sacred site. It is an important monument to Egypt historians as it represented the shift in political power, that was depicted as colourful reliefs on the temple’s inner walls. Furthermore, the carvings also represented Egypt’s many civil wars, and a change in religious ideology. In addition., holes on the ground near its pylon; similar to the ones seen at the Karnak entrance, indicated that there may have existed tall flag poles at the access of the small temple.

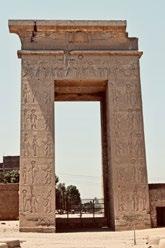

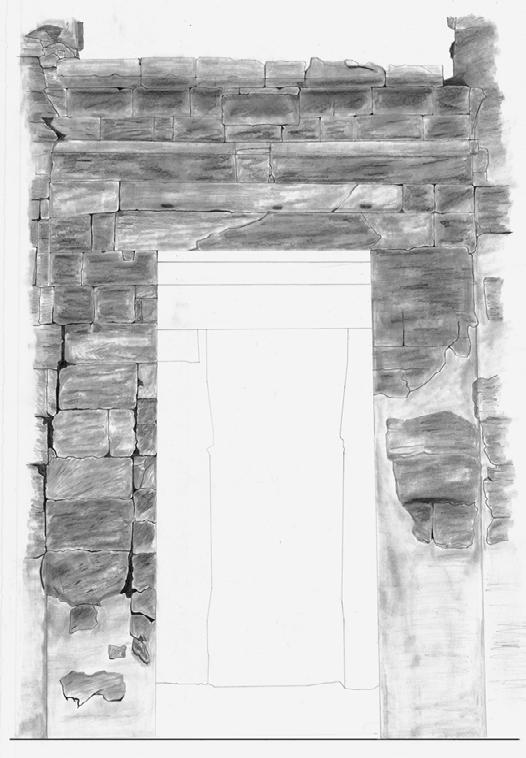

Like many temples in Karnak, the temple of Khonsu featured an entrance pylon (figure 26) that stood 17 meters tall and 10 meters wide. It also contained a mixture of both closed and open papyrus columns that were 7meter high and which gradually became smaller; similar to the layout of Ramesses III’s temple. This can be seen in the section (figure 23) of the temple of Khonsu where there correspondingly seems to be a gradual shift from a much larger open space to a more claustrophobic smaller room (Weeks, 2005).

Ptolemy III built the gate north of the temple of Khonsu, called Bab Al-Amara (figure 24), which translates to the door of the moon symbolising Khonsu, as he is considered the god of the moon (Weeks, 2005). The moon gate is 21 meters high, and is decorated with hieroglyphics that protects the Karnak of evil spirits. The moon gate in turn creates a threshold that represents the gods refusing the entrance “to human enemies and to demons and the powers of pestilence” (Eliade and Trask, 1987). In my opinion, when touching the sandstone of the gate, the material quality evokes a nostalgic feeling of the embodied energy of the realm of the divine that the stones carried.

During the forced Christianization of Egypt during the GraecoRoman period, the temple of Khonsu was converted to a Christian chapel. It is one of the best examples of this in the entire sanctuary. During this period, the Romans removed and defaced the ancient Egyptian religious text on the interior walls of the temple, and replaced with a carving of a Christian cross (figure 25). Because the temple was the religious capital and domain of political power, the Romans were able to gain a wider control of the general Egyptian public, as people are” instinctively drawn to the divine” (Blyth, 2006).

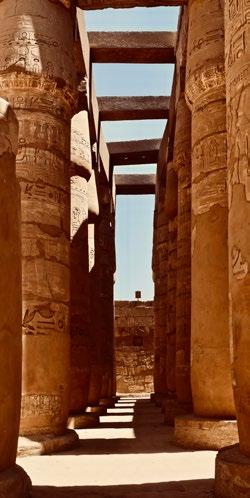

The Great Hypostyle Hall

The Hypostyle hall of Karnak is one of the greatest architectural achievements made by the ancient Egyptians. The 102 meters by 53 meters hall covers 5300 square meters. According to Seton-Williams and Stocks, 1988, the Hypostyle Hall is large enough to contain both St. Pauls Cathedral in London, and St. Peters church in Rome. The Hypostyle hall is situated along the west/ east axis of the Karnak, past the forecourt and the second pylon; called illuminating Thebes. In front of the entrance of the columned hall, lies a large statue of Ramesses II with his daughter Benta Anta (figure 30), as he and Setti I were the ones who built and decorated the hall with colourful religious hieroglyphics (Seton-Williams and Stocks, 1988).

The Hypostyle Hall encloses a total of 134 columns designed to look like the papyrus symbolizing wealth; as the plant was only available to the elite. Along the main west/east processional axis of the temple lays 12 open papyrus columns (figure 33), 23-meter high. The 12 columns resemble the shape of a papyrus plant with an open flower. The capital of the column is shaped like an inverted bell, and is ornamented with colourfully painted leaf designs (figure 36) that symbolizes the petals of the river Nile papyrus (Sullivan, 2008). Contrastingly, the remaining 126 are closed papyrus columns (figure 34) stand at 15 meters, and are arranged in nine rows of seven along the two halves of the hall (Seton-Williams and Stocks, 1988). The closed papyrus columns represent an un-bloomed papyrus plant. Sullivan, 2008 states that these types of columns in the great Hypostyle Hall are more “stylized” than the regular closed papyrus, as they are designed with a straight shaft and slightly angled capitals. In addition, the bases of the 126 columns are originally painted with triangular depictions of papyrus leaves. The columns of the hall are used to support a roof that covered the entire hall, but have collapsed due to earthquakes.

The roof played a vital role in allowing light to be introduced into the temple. Windows at human height were not used when making the temples, as they do not allow the subtle introduction of light into the religious space. This leads the royal builders to create two levels of the roof. The two roofs made with different materials were lined with stone grills that would control the intensity of light which lit up the room of the temple; this is shown in figure 31. However, this technique was later discarded where round or square holes were made on the roof to introduce light that would draw attention in certain parts of the temple, while leaving the rest of the temple in total darkness (Cenival, 1965, p.g. 140). This is seen in Louis Kahn’s sketch of the Hypostyle Hall in figure 32. On the contrary, in Philip and Janssen’s book ‘Columns of Egypt’, they suggested that due to “the blazing heat, dazzling light and minimum rainfall” (Phillips and Janssen, 2002, p.g. 3) they built the temples and pylons of Karnak inwards. Thus, it provided shaded and cool interior spaces that are comfortable for everyday use.

The open papyrus columns accommodated square shaped clerestory windows made of large stone grills (figure 35), and elevated 24 meters above the hall’s floor that were used to provide lighting (Sullivan, 2008). However, because there were only sky lights towards the central axis of the hall, this meant that it was progressively getting darker away from the axis. According to Weeks, 2005, the progressive darkness exuded an “eerie presence” of the surrounding sculptures of the pharaohs and gods that used to exist inside the hall. Nonetheless, in my opinion, instead of creating an eerie presence, the gradual diminishing of light may have been used to add a feeling of sacredness to the hall. For instance, in Christopher Alexander‘s ‘A Pattern Language’ where holiness came from privacy, the darkness is able to create that feeling of isolation in such an enormous sized hall. That if it was under natural light, all the details of the hall would have become exposed, and would cancel out the sensation of remoteness. From a different point of view, the scarcity of natural light in the hall may have been used to protect the royal worshippers from the direct Egyptian sunlight. Thus, providing them shade similar to Marc-Antoine Laugier’s theory of the ‘primitive hut’ in ‘Essay on Architecture’. In agreement with Laugier, 1985, civilizations in ancient times created architecture which sheltered man from nature and his surroundings. However, this does not completely reflect the assumed architectural methods in ancient Egypt, because the Hypostyle Hall did not completely cancel out nature. It was made to accommodate a shallow volume of the Nile water during the summer flooding period. This finding is supported by both Week, 2005 and Seton-Williams and Stocks, 1988 who stated that the hall was made to symbolize the papyrus swamp of the river Nile.

Furthermore, all the 134 columns have carved reliefs of the pharaohs Ramssess II and Setti I worshipping the gods. Likewise, the hall also featured hieroglyphic carvings that used to be highlighted with colours such as red, blue, yellow, black and green, however they have weathered away due to flooding. Although the Hypostyle Hall was restricted to the elites of Egypt, the religious text and carvings were only understood by pharaohs and high-status priests. While low level priests, minor temple employees and the general public visiting the Karnak during the festivals only viewed the hall from the outside. Which in turn resulted in propagandistic depictions that represented the power of the three tirades and their pharaoh carved in the outer walls of the third pylon that enclosed the Hypostyle Hall. Hieroglyphics were not used on the outer walls due to the ancient Egyptian population being approximately 99 percent illiterate. The pharaohs wanted to represent their effort in maintaining the harmony that reigned within the dwelling which contrasted the chaos outside the complex. This is similarly seen in medieval churches in Europe where they featured paintings and stained-glass windows that helped illustrate the “joys of belief” and the suffering of hell (Weeks, 2005).

[Page intentionally left blank]

Obelisks

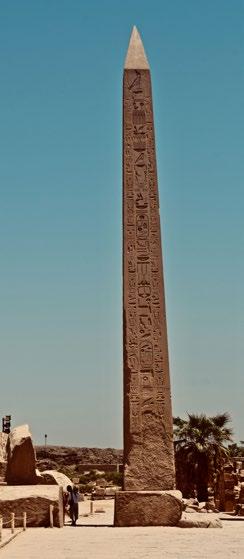

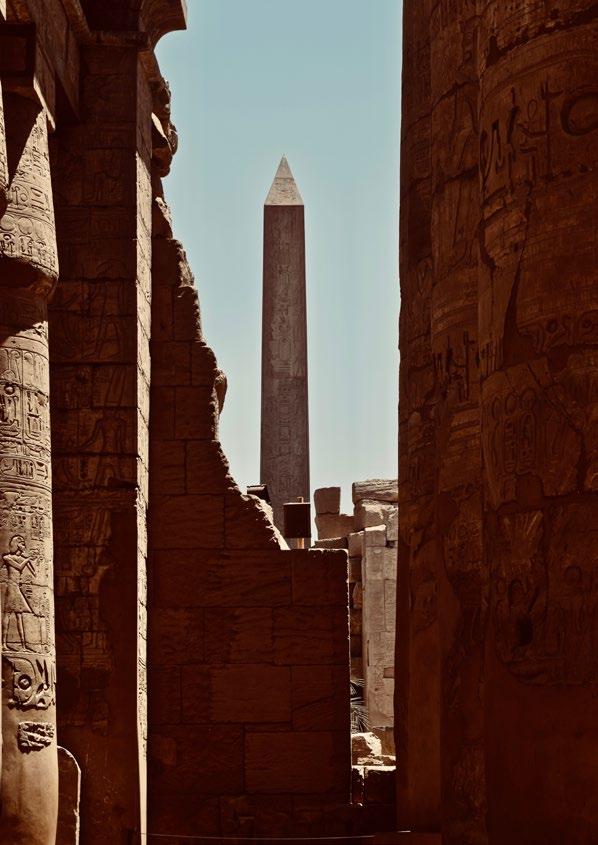

Obelisks were originated in Ancient Egypt. They were monoliths made of stone that reflected the rays of the sun. The origin of the obelisk’s shape is from a stone called the Benben (figure 41). The Benben was a pyramidal stone which is associated to the Egyptian myth of the mound of creation in which land was created when the primordial sea touched the light of the sun (Sullivan, 2008). During the pharaonic era 9 monoliths pierced the skies of Thebes in Karnak. However, only two stand today, one built by Thumois III (figure 42)which is 22 meters tall and 1.8 meters square next to the third pylon. The other one was built by Hatshepsut (figure 43), and it is 30 meters tall and 2.6 meters square between the fourth and the sixth pylon (Weeks, 2005). By looking at the position of the obelisks in the floor plan of the temple, they are situated approximately in the centre. In my point of view, this relates to the Axis Mundi theory that the obelisks were used like landmarks as a “projection of a fixed point-the centre- equivalent to the creation of the world” (NorbergSchulz, 1993)

Despite the archaeological effort in deciphering the architectural techniques of the ancient Egyptians, researchers have not been able to pinpoint the exact construction method of the obelisks. However, based on my visit to the site where one of Hatshepsut’s obelisks once stood, there appeared to be two openings on the surface of its base (figure 40). This may suggest that it was erected by sliding the obelisks in three pieces on a mud-brick ramp, similar to that found next to the first pylon, by using ropes and securing the stones into the two notches.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Karnak is one of the world’s greatest architectural archives that document the saturated rich history of the many dynasties of ancient Egypt. This is clearly seen looking at the hieroglyphic decorations that tell stories of the previous kings serving the gods. It is also apparent through the sanctuary’s iconic monuments; like the Hypostyle Hall or Hatshepsut’s obelisks that soared through the blue skies of the Sahara Desert.

The temple is special in its alignment, and on how it creates a processional route that connects Medinet Habu, the Temple of Luxor, the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut and the Ramsseum to the Karnak sanctuary. Although attempts made by the British astronomer Norman Lockyer to correlate the temple’s alignment with stars Duhhe and Canopus, goes against the datings of Egyptologists and was widely disregarded, yet it needs more consideration. In other words, Lockyer’s theories deserve more study on its alignment, as primitive cultures attempted to align themselves to a greater beyond. In addition, Lockyer was able to help us gain an understanding of the positioning of the pylons towards the western side of the temple, as they acted as instruments of worship, and framed the rising sun during the winter solstice.

In ‘Living Architecture: Egyptian’ by Jean-Louis De Cenival (1965) the earliest royal builders of the sanctuary did not take inconsideration many factors that led to the early diminish of the temple’s foundations. For example, they would join an average sized wall together with a large pylon, which resulted in an increased damage to the foundations, due to the gradual movement of the ground. In my opinion, because the ancient Egyptians were keen to build their shrines to last for an eternity. This notion led them to later standardize the shape and size of the Nubian sandstones, and then bond together with mortar. Additionally, they subsequently joined the blocks with dovetail joints during the drying processes of the mortar to provide extra support, as stated by Cenival, 1965.

Although many of their construction techniques are still undiscovered, remains of the mud-brick construction ramp at the first pylon help us understand part of its riddles. The sandstones may have been pulled up using rollers, or sledges and ropes to reach the instruments of the sun’s superhuman size. Additionally, the two openings on the surface of the base of the obelisks help us deduce that it was notched in parts.

Furthermore, Christopher Alexander (1977) theory in ‘Pattern Language’ paved the way to understand some of the pharaohs reasons in creating religious spaces in the Karnack, and thus evoking a feeling of sacredness. The Egyptians were able to use a series of large pylon gateways, columned halls, statues, obelisks and reliefs that symbolize Egyptian mythological beliefs. Moreover, MarcAntoine Laugier’s (1977) theory of the ‘primitive hut’ in ‘Essay on Architecture’ helped us get a further understanding of primitive cultures desire to create architecture that attempted to shield themselves from natural surroundings. However, it did not fully

Karnak Temple correspond with Laugier’s, 1977 theory because the Hypostyle Hall accommodates some of the Nile River’s water during the flooding season.

Moreover, Religion played an important role in ancient Egyptian architecture. For Example, obelisks at Karnak acted as the vertical landmark, or an Axis Mundi that connects the ancient Egyptian people’s cosmos to the heavens above. It then relates back to axis mundi as the obelisks were situated in the central shrine of the sanctuary. In addition, the shape of the obelisks is also special as they are derived from the Benben stone. Moreover, this conveys back to the ancient Egyptians’ belief of the mound of creation in which land was created when the primordial sea touched the light of the sun. Furthermore, we get additional evidence of this through the mud brick’s layering of the outer enclosure of the temple which mimicked the water waves of the great prehistoric sea. While the land in which Karnak is situated was an island, hence believing that their religion is at the centre of the universe.

In addition, through the use of “The Sacred and the Profane” by Mircea Eilade (1987). We were able to understand further that the Egyptians were driven by an ideology of a heaven on earth. They used multiple thresholds from the very entrance of the sanctuary to the much smaller temple within the complex itself. This meant to create a feeling of protection from the sacrilegious, or to evoke a sensation of passing through a spiritual realm. Additionally, the Egyptians’ manipulated light in the temple of Ramesses III to a single beam of natural light. This is intended as a form of communication with the sun deity Amun, as it signifies “a door to the world above, by which the gods can descend to earth and man can symbolically ascend to heaven” Eliade and Trask, 1987

Finally, Karnak temple can be considered the first milestone towards the foundations of modern architectural theories that can rival or even surpass the Greeks and the Romans. Although some of the temple’s architectural techniques have been uncovered, I believe that the sanctuary should be subject to further studies to unveil all of its mysteries and add value to our current architectural knowledge.

List of Figures

Fig. 1 1:10000 Site Plan (by Author)

Fig. 2 1:1000 Floor Plan (by Author)

Fig. 3 Photograph of the Karnak model in the Karnak Museum (by Author)

Fig. 4 1:10000 site plan of the processional axis route of Karnak (by Author)

Fig. 5 1:200 Plan of the Quay and the Avenue of Sphinxes (by Author)

Fig. 6 Photograph of the Avenue of Sphinxes (by Author)

Fig. 7 1:200 Plan of the 1st Pylon (by Author)

Fig. 8 Sketch of the 1st Pylon (by Author)

Fig. 9 1:500 elevation of the1st Pylon (by Author)

Fig. 10 1:500 southern elevation of the festival court (by Author)

Fig. 11 1:200 Hypothetical drawing of pylon 1 (by Author)

Fig. 12 Photograph of pylon 1 (by Author)

Fig. 13 Example of lining of masonry; middle kingdom left and New Kingdom onwards right (by author)

Fig. 14 Photograph of the Sandstone masonry found in the 1st pylon (by Author)

Fig. 15 Photograph of the mudbrick wall on Pylon 1 (by Author)

Fig. 16 1:500 plan of the forecourt (by Author)

Fig. 17 1:200 plan of the Temple of Ramesses III (by Author)

Fig. 18 Photograph of wall a wall carving of showing Ramesses III receiving the key of life (by Author)

Fig. 19 Photograph of the statues of Osiris in the open court near the entrance of the Temple of Ramesses III (by Author)

Fig. 20 Photograph of the entrance of the Temple of Ramesses III (by Author)

Fig. 21 Photograph of lighting in the Noas in Temple of Ramesses III (by Author)

Fig. 22 Photograph of the columns of the Hypostyle hall in Temple of Ramesses III (by Author)

Fig. 23 1:200 plan and section of the Temple of Khonsu (by Author)

Fig. 24 Photograph of the Bab Al Amara near Khonsu Temple (by Author)

Fig. 25 Photograph of the carving of the cross at Khonsu Temple (by Author)

Fig. 26 Photograph of the entrance pylon Temple of Khonsu (by Author)

Fig. 27 Photograph of the closed papyrus columns at Khonsu Temple (by Author)

Fig. 28 1:20 detailed elevation of the Temple of Khonsu in Karnak (by Author)

Fig. 29 1:500 plan of the Hypostyle Hall (by Author)

Fig. 30 Photograph of the statue of Ramesses II and his daughter Bent Anta by the entrance of the Pylon 2 (by Author)

Fig. 31 Digital sketch of Roof Lighting system in the Hypostyle Hall during the New Kingdom (by Author)

Fig. 32 Louis Kahn’s sketch of the Hypostyle Hall (Anderson, 1995, p.g. 10)

Fig. 35 Photograph of the clerestory windows of the Hypostyle hall as seen from Temple of Khonsu (by Author)

Fig. 34 Photograph of the Open Papyrus column at the Hypostyle Hall (by Author)

Fig. 35 Photograph of the Closed Papyrus column at the Hypostyle Hall (by Author)

Fig. 36 Photograph of the leaf design on the Open Papyrus column (by Author)

Fig. 37 Photograph of a 1.53meter tall person next to the walls and columns of the Hypostyle hall (by Author)

Fig. 38 1:500 plan of the obelisks in the central shrine in Karnak (by Author)

Fig. 39 Watercolour sketch of Hatshepsut’s obelisk (by Author)

Fig. 40 Photograph of the notches on the base of where Hatshepsut’s obelisk once stood (by Author)

Fig. 41 Close-up photograph on the tip of Hatshepsut’s obelisk that resembles the Benben rock (by Author)

Fig. 42 Photograph of Thumois III obelisk (by Author

Fig. 43 Photograph of Hatshepsut’s obelisk (by Author)

Fig. 44 Photograph of Hatshepsut’s obelisk as seen from the Hypostyle hall (by Author)

Aldred, C. (1980). Egyptian art in the days of the Pharoahs, 3100-320 B.C.. London: Thames and Hudson.

Alexander, C. (1977). A pattern language. New York: Oxford. Univ. Pr.

Anderson, S. (1995). Public Institutions: Louis I. Kahn’s Reading of Volume Zero. Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), 49(1), p.10.

Arnold, D. (1999). Temples of the Last Pharaohs. New York: Oxford University Press.

Baines, J. and Málek, J. (2005). Atlas of Ancient Egypt. 3rd ed. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Björkman, G. (1971). Kings at Karnak. Uppsala.

Blyth, E. (2006). Karnak. London: Routledge.

Bauval, R. (2008). The Egypt code. New York: Disinformation.

Cenival, J. (1965). Living Architecture: Egyptian. London: Oldbourne.

Charloux, G. (2012). Le parvis du temple d’Opet à Karnak. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

Ching, F., Jarzombek, M. and Prakash, V. (2010). A Global History of Architecture. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Dodson, A. (2005). Monarchs of the Nile. 2nd ed. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Eliade, M. and Trask, W. (1987). The sacred and the profane. San Diego [Calif.]: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Elliott, C. (2012). Egypt in England. [Swindon]: English Heritage.

Fletcher, J. (2016). The Story of Egypt. 5th ed. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.

Haag, M. (2009). Luxor illustrated. Cairo: Ameri can University in Cairo Press.

Mahmoud, H., Kantiranis, N. and Stratis, J. (2010). Mineralogical Characterization of the Weathering Crusts Covering the Ancient Wall Paintings of the Festival Temple of Thutmosis III, Karnak Temple Complex, Upper Egypt. Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium on Archaeometry, 13th - 16th May 2008, Siena, Italy, pp.261-266.

Jencks, C. (1998). The architecture of the jumping universe. New York: Wiley.

Laugier, M. (1977). An essay on architecture. Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls.

Monderson, F. (2007). Temple of Karnak. Bloomington, Ind.: AuthorHouse.

Nelson, H. and Murnane, W. (1981). The Great Hypostyle Hall At Karnak. Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Norberg-Schulz, C. (1993). The concept of dwelling. New York: Rizzoli.

Phillips, J. and Janssen, R. (2002). The Columns of Egypt. Manchester: Peartree Publishing.

Robins, G. (1997). The art of ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press for the Trustees of the British Museum.

Saylor.org. (2013). Architecture of Great Temple Complexes. [online] Available at: https:// www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/ uploads/2013/03/ARTH110-3.4-Arc hitectureofGreatTempleComplexes. pdf [Accessed 7 Sep. 2018].

Schäfer, H., Brunner-Traut, E. and Baines, J. (1986). Principles of Egyptian art. Oxford: Griffith Institute.

Schwaller de Lubicz, R., Lamy, L., Miré, G. and Miré, V. (1999). The temples of Karnak. Rochester, Vt: Inner Traditions.

Seton-Williams, M. and Stocks, P. (1988). Blue Guide: Egypt. London: Black.

Smith, E. (1978). Egyptian Architecture as Cultural Expression. [Watkins Glen, N.Y.]: American Life Foundation [distributed by Century House].

Smith, W. and Simpson, W. (1999). The art and architecture of ancient Egypt. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Snape, S. (1996). Egyptian temples. Princes Risborough: Shire.

Stierlin, H. (2007). The Pharaohs MasterBuilders. Paris: Terrail.

Sullivan, E. (2010). Karnak: Development of the Temple of Amun-Ra. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1). Retrieved from https://escholarship. org/uc/item/1f28q08h

Sullivan, E. (2008). Architectural Features. On Digital Karnak, Los Angeles. Retrieved from http://dlib.etc.ucla.edu/ projects/Karnak.

Tahara, K. (1998). Egypt. Paris: Editions Assouline.

Tournadre, V., Labarta, C., Megard, P., Garric, A., Saubestre, E. and Durand, B. (2017). COMPUTER VISION IN THE TEMPLES OF KARNAK: PAST, PRESENT & amp; FUTURE. ISPRS - International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII-5/W1, pp.357-364.

Weeks, K. (2005). The illustrated guide to Luxor. 2nd ed. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.