Piano and Voice Brass, Percussion, Strings, and Woodwinds

Piano and Voice Brass, Percussion, Strings, and Woodwinds

14AVA All-State Clinicians

15AVA All-State Schedule

18ABA All-State Clinicians

19 ABA All-State Schedule

20Schedule of Events

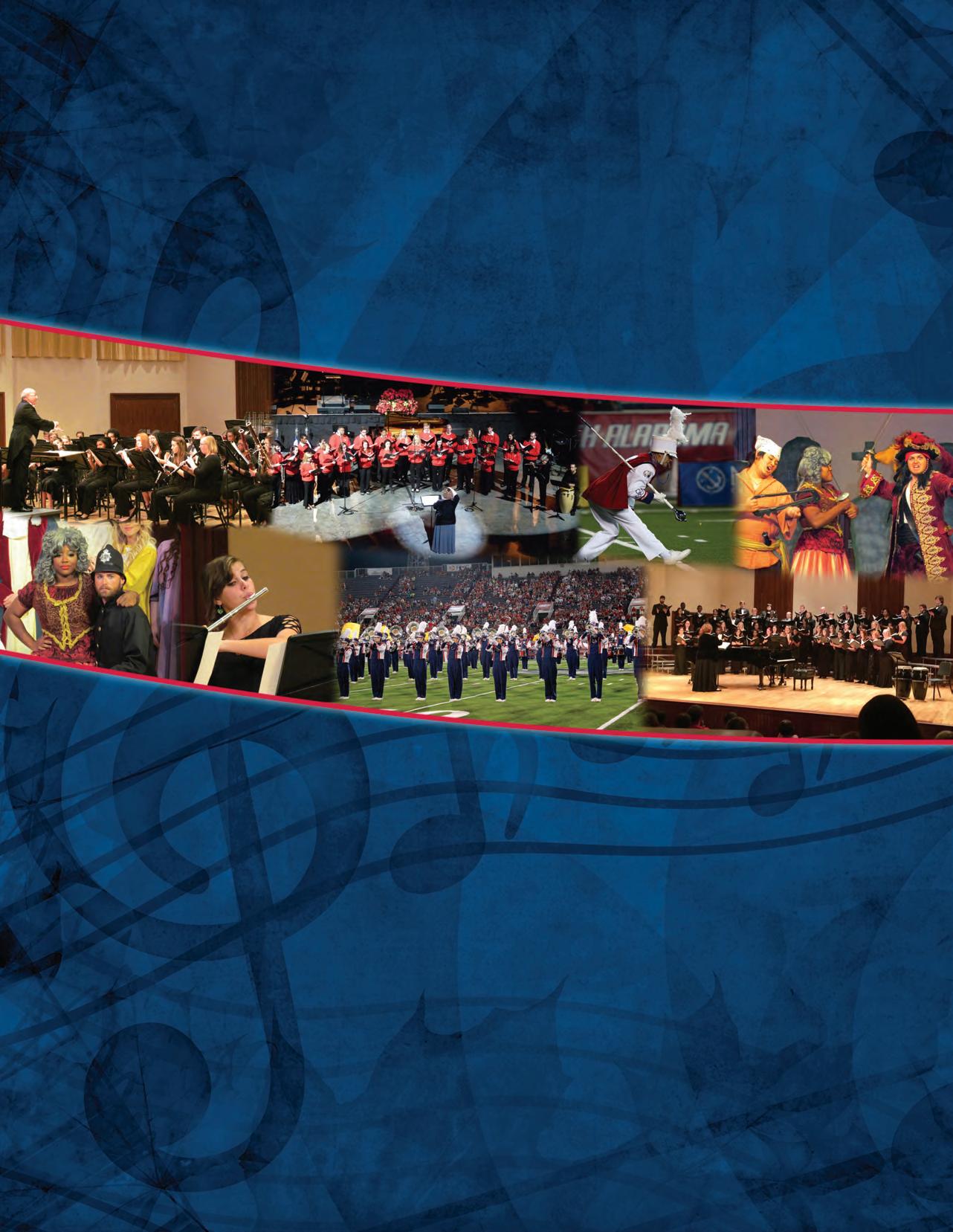

22Conference Photos

24Honors and Awards

26Awareness of Aesthetic Distance...by Timothy Oliver

33Phi Beta Mu Tips That Click

34Choral Priorities: What Really Matters by Judy Bowers

37Movement:A Means to Music Learning by Carlos Abril

40The Path to Mastery by Colin Hill

42Creating a Culture of Inclusion by Ellary Draper

44You Are What You Eat: Repertoire... by David Ragsdale

46Research Evangelism by Mark Montemayor

52Choral Reviews by Erin Colwitz

54Preparing Students for the Collegiate Music Environment by Amir Zaheri

Honor

President Carl Hancock University of Alabama Box 870366 Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 (205) 348-6335 chancock@bama.ua.edu

President, ABA Rusty SmithsCourson Station High School P.O. Box 253 Smiths Station, AL 36877 (334) 664-4435 courson.rusty@lee.k12.al.us

Past President Sara GreystoneWomackElementary School 300 Village Birmingham,Street AL 35242 (205) 439-3200 saratwomack@gmail.com

President-Elect Susan Smith Saint James School 6010 Vaughn Road Montgomery, AL 36116 ssmith@stjweb.org

Executive Director Editor, Ala Breve Garry Taylor 1600 Manor Dr. NE Cullman, AL 35055 (256) 636-2754

amea@bellsouth.net

President, AOA Sarah Schrader 320 Lee Rd. 23 Auburn, AL 36830 (334) 728-2855 burkart_sarah@yahoo.com

Treasurer/RegistrarPat POAMEAStegallRegistration Box 3385 Muscle Shoals, AL pstegall@mscs.k12.al.us35661

President, AVA

Carl Davis Decatur High School 1011 Prospect Drive Decatur, AL 35601 (256) 559-0407

carlbethemeryellen@gmail.com

Industry Representative Becky Lightfoot Arts Music Shop 3030 East Blvd. Montgomery, AL 36116 334/271-2787

beckyl@artsmusicshop.com

Garry Taylor, Editor & Advertising Manager 1600 Manor Dr. NE Cullman, AL 35055 (256) 636-2754

amea@bellsouth.net

AMEA Collegiate Advisor Ted UnivesityHoffman of Montevallo Station 6670 Davis Music Building 308 Montevallo, AL 35115 (205) 665-6668

ehoffman@montevallo.edu

President, Higher Education James Zingara UAB 231 Hulsey Center Birmingham, AL 35294 (205) 934-7376 jzingara@uab.edu

ADVERTISING & COPY DEADLINES

Fall - August/September (Back to School) issue: July 15 Winter - October/November (Conference) issue: September 15

Spring - February/March (All-State) issue: January 15 Summer - May/June (Digital Only) issue: April 15

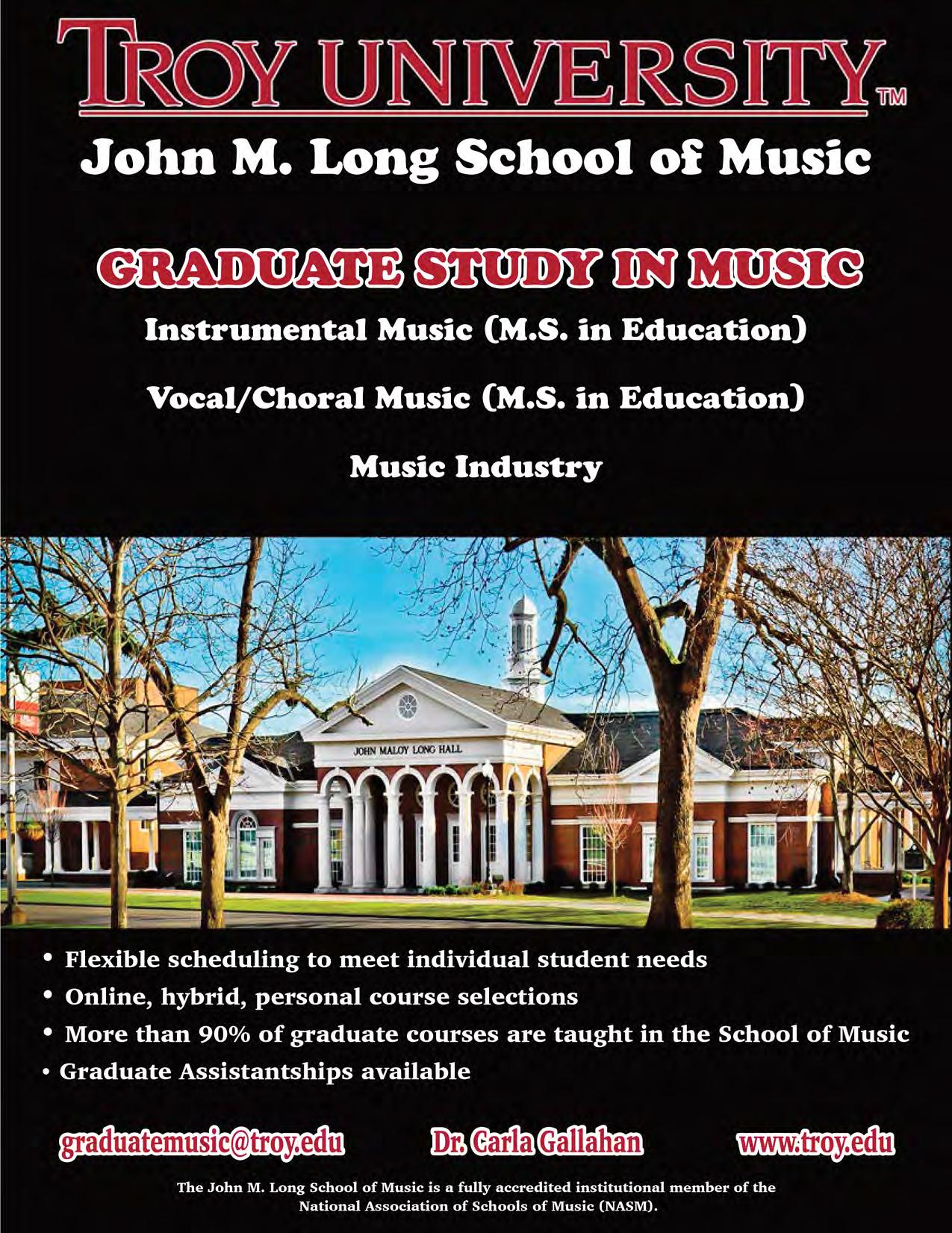

Recording Secretary Carla Gallahan 212 Smith Hall, Troy University Troy, AL 36082 (334) 670-3502 School cgallahan@troy.edu

President, AMEA Collegiate Stacy UniversityDaniels of Montevallo (205) 215-8768

sdaniel4@forum.montevallo.edu

President, Elem/Gen Karla Hodges Rock Quarry Elementary 2000 Rock Quarry Dr. Tuscaloosa, AL 35406 (205) 759-8347

karlahodges@gmail.com

Unless otherwise indicated, permission is granted to NAfME members to reprint articles for educational purposes. Opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of AMEA or the Editor. All announcements & submissions are subject to editorial judgement/revision.The Alabama Music Educators Association is a state unit of NAfME: The National Association for Music Education, a voluntary, nonprofit organization representing all phases of music education in schools, colleges, universities, and teacher-education institutions. Active NAfME/AMEA membership is open to all persons engaged in music teaching or other music education work.

Improved designs have taken the legendary Yamaha concert drum sound to a new level. The new 9000 Professional Series Concert Bass Drum produces a deep, rich sound with exceptional projection due to its 7-ply maple shell with a darkwood stain finish. The addition of steel hoops creates precise and stable tuning to ensure a perfect sound that lasts.

An anti-rotational slip measure on the stand, new noise control features on lug casings and tension rods, and a maple shell truly make this concert bass drum an instrument that will be the only choice for the most advanced of professional percussionists.

9000 Professional Series Concert Bass Drums

I am deeply honored to have an opportunity to share my thoughts with you. I know this is a standard statement for persons in leadership, but for me it has the added virtue of being true. We are coming off of a well-executed conference to the credit of our division officers, clinicians, conductors, and the organizational brilliance of our executive director, Garry Taylor, and while the conference was far from perfect, we can take comfort in knowing that many of the initiatives we implemented this year were well-received (See August 2014 or February/March 2015 President’s column). This was by all measures a successful conference.

First, it was one of the largest events we have hosted since 1973. Conference records were surpassed for the number of conference registrations, exhibitor booths, college attendees, FAME participants, clinic sessions, and even the number of research posters presented. To my surprise, the conference was attended by 67% of the entire association! To place this in perspective, I looked at the conference attendance reported in 2010, just prior to our move to Montgomery, and learned attendance is up by over 20% with this year being the largest since our move! This is an impressive amount of growth for a state conference, and we need to share this with potential exhibitors, clinicians, and the ALDE. Thank you for attending the conference and investing in your professional growth as a music educator.

Second, the feedback we received indicates most of our members were very pleased with the conference and the clinics. Seventy-two percent of attendees rated the conference as Excellent or Very Good (Excellent – 39%, Very Good –33%, Good – 19%, Fair – 9%, Poor – 0%) and another seventy percent rated the clinics as Excellent or Very Good (Excellent – 34%, Very Good – 36%, Good – 18%, Average – 9%, and Poor –

3%). Although these assessments are encouraging, we will endeavor to improve our conference because your time is valuable, and our mission to help the students of Alabama is too important. By the way, I want to thank those of you who freely gave your feedback online and in person to any member of the AMEA Governing Board. We deeply appreciate your compliments, suggestions, and candid conversations.

And third, any successful conference generates a multitude of interesting ideas and suggestions. One idea is the desire of AMEA members to hear from successful new and veteran teachers. As many of you know, I recently went through all of the conference programs from 1984 to 2014 and carefully looked at the names of the session presenters. I was surprised by the list of accomplished teachers in our state who have never presented at our conference before. I want to encourage you to find persons you would like to present and convince them to submit a session proposal for the 2016 In-Service Conference. If you do not feel ready to present a full-session or if you think someone has a great idea they need to share, then you might be interested in submitting a proposal to present in our first ever Lightning Round Session. The Lightning Round Session will consists of six to ten speakers who will each present one great idea in under six minutes. The goal is to provide information quickly and efficiently. If you’ve ever watched a TED Talk online, then you will have the general idea. If you’ve never presented before at AMEA, this is a great way to get your feet wet.

On behalf of the AMEA, I’d like to extend my sincerest congratulations to the performing groups and presenters on a job well done. In addition, I’d like to thank everyone who presided over sessions and provided assistance throughout the conference. Leadership comes in many forms. Thank you for modeling selfless service to our profession and for preparing

sessions and concerts for us to learn from and enjoy.

Finally, it has been said by many of our past-presidents that the success of the AMEA In-Service Conference lies in the hard work put in by the members of the Governing Board and the leaders of our various divisions. The AMEA is most fortunate to have the leadership of these fine music educators.

Garry Taylor, Executive Director

Susan Smith, AMEA President-Elect

Sara Womack, AMEA Immediate Past President

Pat Stegall, Treasurer/Registrar

Carla Gallahan, Recording Secretary

Rusty Courson, Alabama Bandmasters Association President

Sarah Schrader, Alabama Orchestra Association President

Carl Davis, Alabama Vocal Association President

Karla Hodges, Elementary/General Division President

James Zingara, Higher Education Division President

Edward Hoffman, Collegiate Advisor

Stacy Daniels, Collegiate President

Becky Lightfoot, Industry Membership Representative

Three of our governing board members are serving their final semester with us and I’d like to thank them for their service. Thank you to Karla Hodges, Rusty Courson, and Stacy Daniels. Good luck to all of you on your future endeavors.

I wish everyone good luck as you prepare for spring concerts, festivals, assessments, and all-state events. If there is anything we can do to help you, please feel free to contact me directly. I would love to hear your ideas and answer any questions you might have about the future of our association.

Carl

Carl

Carl Hancock AMEA President

Unorthodox. Unexpected. Unusual. Rather than follow the path of least resistance, creativity is about asking, questioning and discovering new paths to insight. It thrives in an environment that encourages individuality over conformity, and self-discovery through community. Discover unconventional wisdom at the University of Montevallo Department of Music, an All-Steinway School offering Bachelor of Music degrees in Music Education & Performance and the Bachelor of Arts degree in Music.

SCHOLARHIP AUDITION DATES:

2.7.152.28.153.14.15

To schedule an audition, complete the online form found at: www.montevallo.edu/music/auditions

To schedule a visit or for more information contact: 205-665-6670 or music@montevallo.edu

www.montevallo.edu/music

I hope this message finds you well and feeling refreshed after attending the 2015 AMEA Conference in January. We had three very busy days of professional development and fun and I hope that you were able to walk away with a few new ideas that you can implement into your classroom. Thank you for the feedback many of you have provided after attending the conference. It is always helpful to hear your ideas as we begin to plan for future conferences. If you were not able to attend this year I hope that you will be able to join us next year.

I would like to take this opportunity to say thank you to all of you. Thank you for trusting me to lead our division and for the continuous support and encouragement you have shown me over the past two years. It has been an honor to serve as your President. I will always look back on this time with gratitude because this opportunity challenged me to grow professionally and allowed me the opportunity to meet many new faces. I am excited to pass

1946Yale H. Ellis

the responsibility over to the new board. I know that their leadership will continue to guide us on the path of excellence. The Executive Officers for 2015-2017 are: Cliff Huckabee, President; Phil Wilson, President-elect; Karla Hodges, Past President; Lori Zachary, Treasurer; Melissa Thomason, Secretary; Kristi Howze, Hospitality. I would like to say a special thank you to our outgoing Past President, Dr. Beth Davis. Thank you for giving to our division for the past six years. It is a huge commitment and I thank you for leading, guiding, and directing us with your wisdom.

I wish you all a fantastic Spring Semester! Be on the lookout for information pertaining to the 2015 AMEA Elementary Music Festival. We will be sending out information via email by the end of February. I hope that you will consider participating in this wonderful event that will leave a wonderful lasting impression on your students and their families!

Upcoming Dates:

March 7, 2015 AOSA Spring Workshop Vestavia Hills Elementary East, Rene Boyer

April 24-25, 2015 ACDA Young Voices Festival University of Alabama Tuscaloosa, AL

2015 AMEA Elementary Music Festival/ Fall Workshop: Information coming soon!!

January 21-23, 2016 AMEA In-Service Conference; Montgomery, AL

1970Jerry Bobo

1992Dianne Johnson

1948Walter A. Mason

1950Vernon Skoog

1952John J. Hoover

1954Lamar Triplett

1956Carleton K. Butler

1958Mort Glosser

1960Wilbur Hinton

1962Lacey Powell, Jr.

1964G. Truman Welch

1966Jerry Countryman

1968Floyd C. McClure

1972Frances P. Moss

1974George Hammett

1975Frances P. Moss

1976S. J. Allen

1978W. Frank McArthur, Jr.

1980Paul Hall

1982Lacey Powell, Jr.

1984Johnny Jacobs

1986Merilyn Jones

1988Ronald D. Hooten

1990Ken Williams

1994James K. Simpson

1996Johnnie Vinson

1998Michael Meeks

2000John McAphee, Jr.

2002Tony Pike

2004Becky Rodgers

2006John Baker

2008Pat Stegall

2010Steve McLendon

2012Sara Womack

2014Carl Hancock

Like me, I hope that you greatly enjoyed your time at the 2015 AMEA Conference and came back to your jobs reinvigorated and ready to take on the many challenges that face us every day. It is a time to connect with colleagues and former students; to share information and to garner new ideas for the future. The goal of this year’s conference was to bolster membership participation, and in this, I believe that we have had success. The HED luncheon attracted 19 colleagues from 10 institutions from around the state; the new student recital

brought together 60 student performers from 5 different universities who performed to over 100 people. We also brought new ideas to the table to help establish a unique HED footprint in the future. The luncheon discussion launched the Community College Initiative as well as possible future projects such as a solo competition and a call for scores/faculty recital. The View from the Chair panel discussion brought four accomplished chairs and covered topics concerning tenure, promotion, leadership, collegiality and entrepreneurship.

The HED conference sessions were eclectic, addressing topics in percussion, practicing, choral music, teacher education and conducting. I would like to thank Luis Rivera (USA), Matt Greenwood (USA), Danielle Todd (UA), Melinda Doyle (Montevallo), Brian Kittredge (UAB), Sue Samuels (UAB), and special guest lecturer Robert Duke (University of Texas) for

sharing their expertise through their session presentations.

There are many more to thank for the success of this conference. I first would like to thank Mildred Lanier (HED SecretaryTreasurer) and Lori Ardovino for serving as presiders. Our first-ever panel discussion was a great success due to contributions of participating departmental chairs Dr. Sara Lyn Baird (Auburn), Dr. Kathryn Fouse (Samford), Dr. Alan Goldspiel (Montevallo), and Skip Snead (Alabama).None of the above would be possible without the expert guidance and leadership of the AMEA Executive Director, Garry Taylor.

Thanks again for all your contributions and hard work. I wish all of you a successful and enjoyable Spring semester and will look forward to working with you as we head towards the 2016 AMEA Conference.

Thank you to all our presenters at this year’s AMEA conference. You made this year’s conference fantastic! The string presentations were especially interesting, motivating, and rejuvenating. We enjoyed sessions in the areas of ensemble listening, classroom technology, fiddling techniques, bass techniques, and shifting. We were lucky to have some of our own state colleagues present this year. Thank you Dr. Anne Witt, Dr. Daniel Stevens, and Dr. David Ballam for your wonderful sessions. To round out our sessions a performance by the Rock Quarry Middle School Orchestra from Tuscaloosa added the perfect finishing touches. The AMEA conference is such a great refresher each year. It always gives me the energy to finish out the school year with enthusiasm. If you missed it this year, I hope you will make time in your busy

schedules to attend next year’s conference in January.

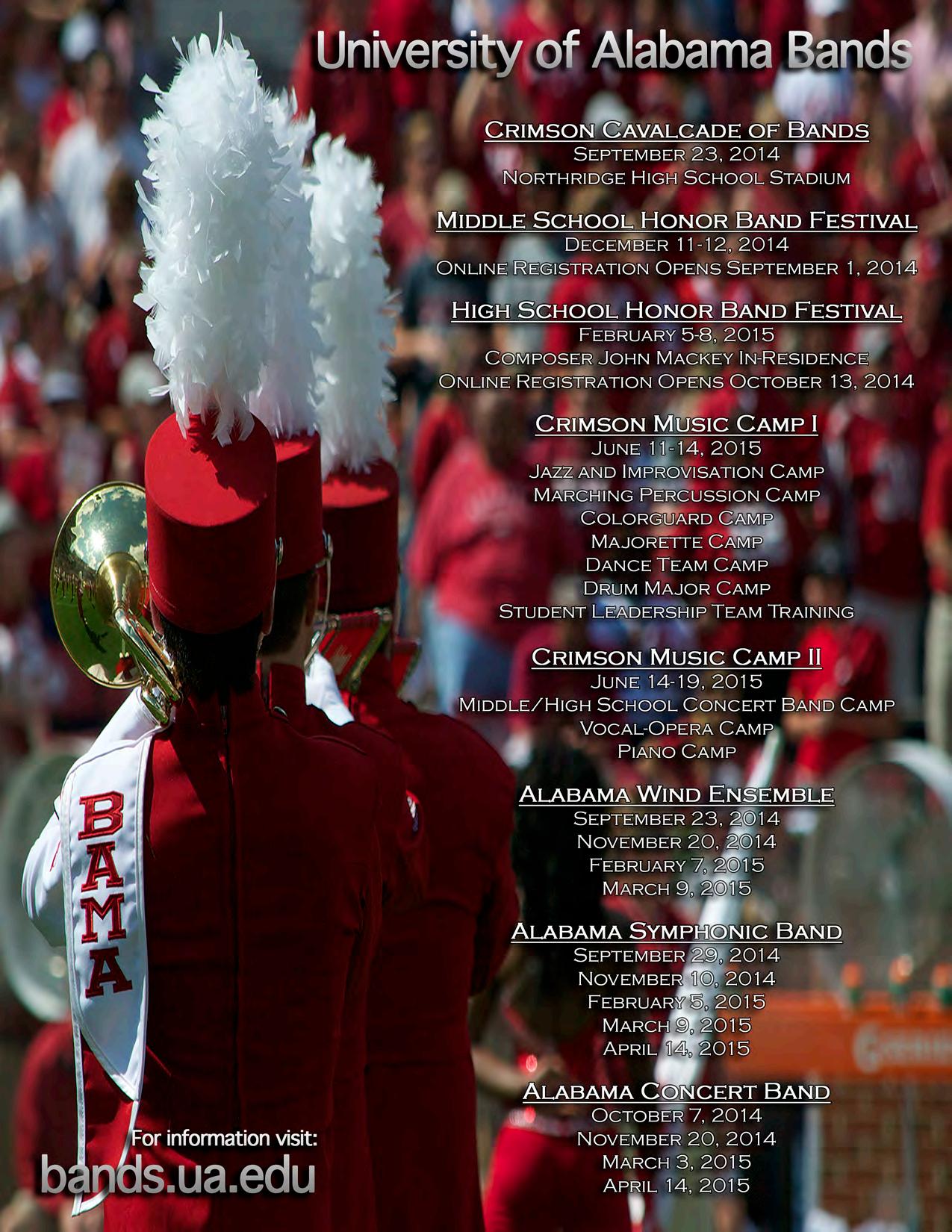

Our next AOA event is All State Orchestra will be underway or completed when this issue is published. Thank you to all the conductors, judges, sectional coaches, and teachers for taking the time to work with Alabama’s talented young musicians. This weekend is an amazing experience for all who attend. I appreciate your sharing of your time and talents with them to make this weekend amazing. Thank you to the University of Alabama for hosting us again this year. It is a blessing to have this venue to hold the festival.

I am very proud of all the students who auditioned and made All State Orchestra this year. The competition was very high this year and you should be very proud of your achievements. For those who didn’t make it to the festival this year, I hope you will audition again next year. I remember years ago when I was in your shoes auditioning and attending All State. That

weekend was one of the highlights of my year. It was always great to get together with players from all around the state under the direction of a top notch conductor. If your students haven’t experienced this yet, consider encouraging them to participate in the future.

I would like to thank the AOA Executive Board and district chairs, Sam Nordlund, Felicia Sarubin, Daniel Jamieson, Julie Hornstein, Jacob Frank, Matthew Grant, Elisabeta Warden, Eugene Conner, ChinMei Li, and Roland Lister for your help this year with all events. These events would not be possible without all your hard work. Thank you for all you do!

In closing, I pray that you can continue to keep your enthusiasm high throughout the end of the school year. Set your goals for your students and stick to them. I look forward to hearing your success stories from this year!

We just enjoyed a superb winter conference reconnecting with each other, sharing information, attending sessions and concerts. We certainly appreciated the sessions by our own presenters. However, Dr. Tucker Biddlecombe was a welcomed newcomer, and I hope that we see more of him in our future—either at an all-state festival or honor choir. Even though his reading session addressed contentmainly for high school level, he provided such variety within the literature. There was nothing substandard and a majority of the literature is accessible by all. I encourage you to contact Margaret or Tom at Beethoven and Company the next time that you need any literature. They provided his packet of music at no cost to AVA. After discussing with Dr. Biddlecombe the content of his sessions planned for the conference, I attempted to choose other sessions, from the session proposals which would complement his topics. We were afforded sessions targeting functional aspects of the choral rehearsal— vocal health, theory, rehearsal pacing, sightreading and language we use in the rehearsal. My hopes were that your students rehearsing this spring semester would directly benefit from your attendance. Paul Gulsvig and Jarrod Voss engaged our All-State Show Choir students in quality rehearsal and performance.

I congratulate the finer performances by the ensembles that presented concerts. I want to encourage you to submit for a performance. To this end, plans are underway to move our performances to another location in the civic center that is acoustically more beneficial for choral singing than is the performing arts auditorium. We will have more to say about this at the All-State Festival in April, but certainly consider recording your SCPA selections and submitting for a concert performance.

Being chosen for All-State Chorus is one of the highest honors a choral student in the state can receive. We auditioned approximately 3,000 students in November with approximately one-third of those being chosen for one of our five all-state

ensembles. Those students will interact with some of our finest vocal conductors. Read the information concerning our guest conductors in the following pages.

Be aware that the all-state schedule this year is quite different. I presented some of the more striking differences from past schedules at the winter conference. We are no longer on one campus. Our students will be split between Samford and First Baptist Church. Although the facilities are close in proximity, pre-arrival planning of the logistics is necessary. Pay special attention that the high school SATB ensemble is the only ensemble that is allowed to eat on the Samford Campus. Their rehearsal is planned around them utilizing the cafeteria for lunch. All other ensembles must transport off-site to eat. Please honor this request. Note that the high school SSA/TTBB ensembles and the middle school Mixed/Treble ensembles swap locations from Samford to First Baptist Church. Be expecting your all-state information to be available on the AVA website from our president-elect Ginny Coleman one month prior to the festival.

I’ve asked our district chairman to update their web pages on the AVA website. You should expect all communications for all AVA events to be disseminated via our website. If you are attending an SCPA in another district you should be able to get all information concerning the event you are attending from that district’s web page. Let your district chairman know if you have difficulty accessing the information.

Lastly, we need to consider the philosophical reasoning of the opportunities we provide our members. First, we currently have our State Outstanding Choral Students perform a solo on the all-state concert. Does this practice duly honor these students? I encourage you to peruse the rubric our adjudicators use to select the winners. Does a solo performance accurately reflect and demonstrate the substance of the award? Is there a more fitting way in which to recognize an outstanding choral student, rather than have them perform a solo?

Secondly, the All-State Show Choir performs at the beginning of the convocation at the All-State Festival. Financially, this costs our organization in excess of a thousand dollars. It is completely un-funded. If we chose to continue this practice, then we must discover and/or develop a revenue stream to render it cost neutral. Is this a practice that you consider so important that we discover a method to have it pay for itself? If it is beneficial, then what are the benefits? Is the gain worth the unfunded cost? These are two discussion topics for our summer board meeting. We asked you to provide thoughtful written communication to your district chairman as early as fall workshop and we asked again for this at the winter conference. We have received several pages of dialog. Please continue to provide us with your opinion. At the summer board meeting we will attempt to make decisions based on what is going to be best for our students. Please communicate with your district chairman.

See you at Samford.

Beth Holmes currently conducts the Millikin Women, a choir comprised of 60 freshmen singers, and serves on the Millikin voice faculty. Under her direction the choir hosts an annual Women’s Choral Festival on campus, takes an Illinois tour, and performs for the popular Millikin Christmas Vespers and other annual concerts. Beth is an active guest conductor, directing District and AllState festival choirs and Convention Honor Choirs throughout the Midwest. Recent appearances include Women’s Honor Choirs on the 2010 Regional ACDA convention in Minneapolis, as well as state ACDA conventions in Illinois, Florida, and Minnesota. A graduate of Kansas State University, Beth subsequently completed a Masters in Choral Conducting at Arizona State University. She served as the Artistic and Musical Director of the Millikin University Children & Youth Choir Program for 7 years, conducting its premiere ensemble and coordinating a staff of conductors, managers, and Millikin student interns. She has served as ACDA Repertoire and Standards Chair for Women’s Choir in both Iowa and Illinois, and maintains a private voice studio in her home.

University of New York, where she directs the Queens College Women’s Choir and provides instruction in choral methods and conducting. Dr. Babb also coordinates the choral ensembles of the Lawrence Eisman Center for Preparatory Studies in music at Queens College, and she is the Artistic Director of the Queens Youth Choir. She earned the B.M.E., M.M.E., and Ph.D. from Florida State University in Tallahassee, FL. Her research interests include vocal tone development, critical thinking in music education, and English language learners in the music classroom. She is an active conductor and clinician, conducting honor choirs throughout the United States, as well as presenting at state, regional and national conferences of the American Choral Directors Association and the National Association for Music Education. Dr. Babb is an active member of ACDA, NAfME, NYSSMA and CMS.

Dr. Christopher Aspaas, Associate Professor of Choral/Vocal Music at St. Olaf College, received his Ph.D. in Choral Music Education at The Florida State University in Tallahassee, his M.M. in Choral Conducting from Michigan State University in East Lansing, his B.M. in Voice Performance from St. Olaf. Christopher has served on the faculties of Central Washington University in Ellensburg, Washington and Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. At St. Olaf, Aspaas conducts the Viking Chorus, a 90-voice ensemble of first-year student men, and also leads the Saint Olaf Chapel Choir, a 100-voice ensemble specializing in the performance of oratorio and larger multi-movement works. In recent years, Christopher has conducted performances of Brahms’ Ein Deutsches Requiem, Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and most recently, Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, which was chosen for broadcast on Minnesota Public Radio.

Sandra Babb

Sandra Babb

Dr. Mark W. Bartel, associate professor of music and director of choral music, has been with Friends University since 2005. Dr. Bartel conducts the Singing Quakers, Madrigal Choir, Women’s Chorus and Choral Union. He also teaches in the areas of applied voice and conducting. He has held positions at Hobart and William Smith Colleges (N.Y.), University of Western Ontario and Canadian Mennonite University. His choirs have performed at Kansas Music Educators and regional American Choral Directors Association conventions and toured the United States, Canada and Germany. He also serves as the artistic director of the Wichita Chamber Chorale.

Lynne Gackle currently is Professor of Ensembles and Associate Director of Choral Activities at Baylor University (Waco, TX) where she conducts the Baylor Bella Voce (Select Women’s Ensemble) and the Baylor Concert Choir. Lynne is an active clinician, conductor and adjudicator for choral clinics,

Beth Holmes MS Treble

MS Mixed

Sandra Babb is Assistant Professor of Music Education at Queens College, City

Mark Bartel HS TTBB

Chris Aspaas HS SSA

Lynne Gackle HS SATB

Beth Holmes MS Treble

MS Mixed

Sandra Babb is Assistant Professor of Music Education at Queens College, City

Mark Bartel HS TTBB

Chris Aspaas HS SSA

Lynne Gackle HS SATB

honor choirs, workshops and festivals throughout the United States and abroad. Gackle has conducted All-State choirs in 30 states, several divisional ACDA honor choirs and two ACDA national honor choirs. Her choirs performed at American Choral Directors Association state, division, and national conferences and the Music Educators National Conference Biennial Convention. Internationally, she conducted the Australian National Choral Association’s

High School Women’s Choir in Brisbane, the Alberta Choral Federation’s High School Honour Choir in Calgary, the DoDDSEurope Honors Music Festival Mixed Choir, (Wiesbaden, Germany), the Haydn Youth Festival in Vienna, and the Association for Music in International Schools (AMIS) International Women’s Honor Choir in Beijing, China. Lynne has served as president of ACDA-Florida and the ACDA’s Southern Division. The Florida ACDA

Wednesday–April 8, 2015

11:00 a.m.Board Meeting, Wright Center Basement

2:45 p.m.Female OCS Competition - Brock Recital Hall

4:30 p.m.OCS/OA – Picture - Brock Recital Hall

5:00 p.m.Male OCS Competition - Brock Recital Hall

OA Competition

Thursday–April 9, 2015

8:00 – 11:30 a.m.All-State Show Choir Rehearsal

Wright Performance Center Stage

10:00 a.m.–1:00 p.m.Registration - Wright Basement

1:00 - 1:45 p.m.General Assembly - Wright Performance Center

ASSC Performance

High School All-State Rehearsals – SAMFORD UNIVERSITY

2:00 – 6:00 p.m.HS SATB Wright Performance Center

HS SSA Brock Recital Hall

HS TTBB Cassessee Band Hall

6:00 – 8:00 p.m.High School Dinner Break

8:00 - 10:00 p.m.High School All-State Rehearsals

Same sites as first rehearsal

11:00 p.m. Curfew

Middle School All-State Rehearsals – FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH

2:30 – 5:30 p.m.MS Mixed FBC Sanctuary

MS Treble FBCBasement

5: 30 – 7:30 p.m.Middle School Dinner Break

7:30 – 9:30 p.m.Middle School All-State Rehearsals — FBC 11:00 p.m. Curfew

Friday–April 10, 2015

Morning Rehearsals

HS Rehearsals @ Samford

MS Rehearsals @ First Baptist Church

MS Mixed FBC Sanctuary

MS Treble FBC Basement

8:30 – 11:00 a.m.Rehearsal

11:00 – 1:30 p.m.Lunch

HS SATB

8:30 – 11:00 a.m. Brock Recital Hall

11:30 – 1:00 p.m. Wright Performance Center

1:00 - 2:30 p.m.Lunch on campus

2:30 – 4:30 p.m. Brock Recital Hall

chapter awarded her the Wayne Hugoboom Distinguished Service Award for dedicated service, leadership, and excellence. Dr. Gackle was also awarded Baylor’s Outstanding Faculty Award in Research in 2012.Lynne received her BME from Louisiana State University and her MM and Ph.D. from the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida.

HS SSA 8:30 - 10:00 a.m. Wright Performance Center

– 11:30a.m. Cassessee Band Hall 11:30 – 2:00p.m.Lunch(not on campus)

– 5:00 p.m. First Baptist Church Sanctuary

HS TTBB

8:30 – 9:45a.m. Cassessee Band Hall

10:00 – 11:30a.m. Wright Performance Center

11:30 – 2:00p.m.Lunch(not on campus)

2:00 - 5:00 p.m. First Baptist Church Basement

Afternoon Rehearsals

HS SSA & TTBB Rehearsals @ FBC

MS Mixed & Treble; HS SATB Rehearsals @ Samford MS Mixed

Saturday-April 11, 2015

11:30a.m.Call Time-HS Concert - Wright Performance Center (Performers Seated)

OCS/OA./ME District Winners(Assigned seats in front of auditorium)

photo

Congratulations to Morgan Sweatman, a clarinet player from KDS DAR High School, on being selected to participate in the U.S. Army All-American Marching Band. Morgan received an all-expense paid trip to San Antonio for the All-American Bowl, including airfare, hotel, food, rehearsal gear, performance gear, instrument (borrowed), and more. Morgan was nominated by DAR band director, Jody Stiles.

with the quality of all this year's applicants. This was our most competitive year, and it was difficult to narrow the field,” says Associate Artistic Director Marcus Roberts. “Leading Swing Central Jazz is a highlight for me every year. Our group approach to instruction immerses students in big band jazz, and after three intense days, students, band directors and clinicians walk away inspired by this great art form.”

Selected as one of twelve high school Jazz Bands to Participate in the 2015 Savannah Music Festival

Savannah, Georgia – Twelve of the nation’s top high school jazz bands have been selected to participate in the ninth annual SWING CENTRAL JAZZ High School Jazz Band Competition & Workshop, an event produced by the Savannah Music Festival (SMF). Pianist/composer Marcus Roberts leads a group of 23 esteemed musicians/ educators as the Associate Artistic Director, along with Associate Director Jim Ketch, trumpet player and Director of Jazz Studies at UNC Chapel Hill. Participating students work with jazz masters across three days, perform in the “Jazz on the River” showcase on Savannah’s River Street, play in competition rounds, and attend a variety of SMF performances during their stay, which takes place from March 25 through 27, 2015. “We were thrilled

Grissom High School A Jazz Band

Theo Vernon and Bill Connell of Grissom High School presents Concert Band Camp? It’s the Residuals!! occuring during “The Midwest Clinic” in December.

Grissom High School A Jazz Band

Theo Vernon and Bill Connell of Grissom High School presents Concert Band Camp? It’s the Residuals!! occuring during “The Midwest Clinic” in December.

As I write this, I’m still recovering (and reflecting) on our AMEA In-Service Conference this year. It is SO refreshing to be able to experience professional development that is actually applicable to our field!!! I’m sure that we’ve all experienced PD sessions at our school that have absolutely NOTHING to do with music education. Thank you so much to those of you that took the time to share your ideas with us in a clinic setting.

We were also very blessed to have GREAT concerts this year!!! A very special thanks to the Faith Academy Symphonic Band (David Pryor), the Tuscaloosa County High School Wind Ensemble (Jed Smart), the Sparkman High School Wind Ensemble (David Raney), the Shades Valley High School Symphonic Band (David Allinder), the Monrovia Middle School Advanced Band (Donald Dowdy), and the Alabama Winds (Randall Coleman). I would be remiss in not mentioning the Intercollegiate Band performance as well, conducted by

one of the greats in our field, Col. John Bourgeois.

If you submitted a proposal for a clinic or applied for a performance slot, and you weren’t selected this year, please consider reapplying for 2016. We have a limited number of slots for clinics and performances, and both of the years that I’ve been President, we’ve had some very tough choices to make. Application forms can be found on the AMEA website, and the deadline for submitting applications to Garry Taylor is June 1st

After spending the last two years in Huntsville, we will be traveling back to Mobile this year for our All-State Band Festival. On Wednesday, April 11th, our state solo contest will take place on the campus of the University of South Alabama, and we will be at the Mobile Convention Center on Thursday, April 12th and Friday, April 13th. The dress rehearsal and final concert will take place at the Mobile Civic Center on Saturday, April

14th. Clinicians this year are Robert W. Smith, Red Band; Richard Saucedo, White Band; Dr. Ken Bodiford, Blue Band; and Dr. Carla Gallahan, Middle School Band.

Our summer convention will be held at the Hampton Inn and Suites in Orange Beach again this year. The ABA Board and Music Selection Committee will meet on Tuesday, June 23rd, while we’ll have ABA general business meetings and clinics on Wednesday, June 24th and Thursday, June 25th. If you have any ideas for clinics, please contact our incoming President, Michael Holmes, at thetubaman@charter.net. As always, if you have questions or concerns, feel free to contact me at courson.rusty@lee.k12.al.us. I look forward to seeing all of you at all-state in Mobile this April!!!

Alabama Bandmasters Association , ABA Legislation 2015-3

CLASSIFICATION of BANDS for MPA:

1) Remove Article XVI Section 2.

Add:

Section 2. Classification of Bands

a. For the purposes of the ABA Music Performance Assessment, bands will be classified according to the following criteria:

Classifications:

AA bands will play a composition off of the AA ABA Cumulative List

A bands will play a composition off of the A ABA Cumulative List

BB bands will play a composition off of the BB ABA Cumulative List

B bands will play a composition off of the B ABA Cumulative List

CC bands will play a composition off of the CC ABA Cumulative List

C bands will play a composition off of the C ABA Cumulative List

D bands will play a composition off of the D ABA Cumulative List

Sight Reading:

Bands classified as AA will sight-read from the level VI sight-reading list

Bands classified as A will sight read from the level V sight-reading list

Bands classified as BB and B will sight-read from the level IV sight-reading list

Bands classified as CC and C will sight-read from the level III sight-reading list

Non-beginning bands classified as D will sight-read from the level II sight-reading list

Beginning bands (all students in their first and second year of band) classified as D will sight-read from the level I sight reading list

b. From the pieces chosen by the director for performance at Music Performance Assessment, ONE COMPOSITION must be from the approved Alabama Bandmasters Association (ABA) Cumulative Music List.

c. Bands will be classified by their chosen selection from the ABA Cumulative Music List and their corresponding sight-reading level.

d. NO STUDENT WILL BE ALLOWED TO PARTICIPATE IN MULTIPLE BANDS. If a director has a special need for a student playing in a second band, the director shall present the facts and circumstances prompting the request to the Board of Directors at the AMEA In-service Conference in January. The director will be notified immediately if possible, but within seven (7) days if further study is necessary. FOR ANY STUDENT TO QUALIFY IN ADDITIONAL BAND(S), HE OR SHE MUST PERFORM ON A DIFFERENT INSTRUMENT.

Carla Gallahan

Carla Gallahan

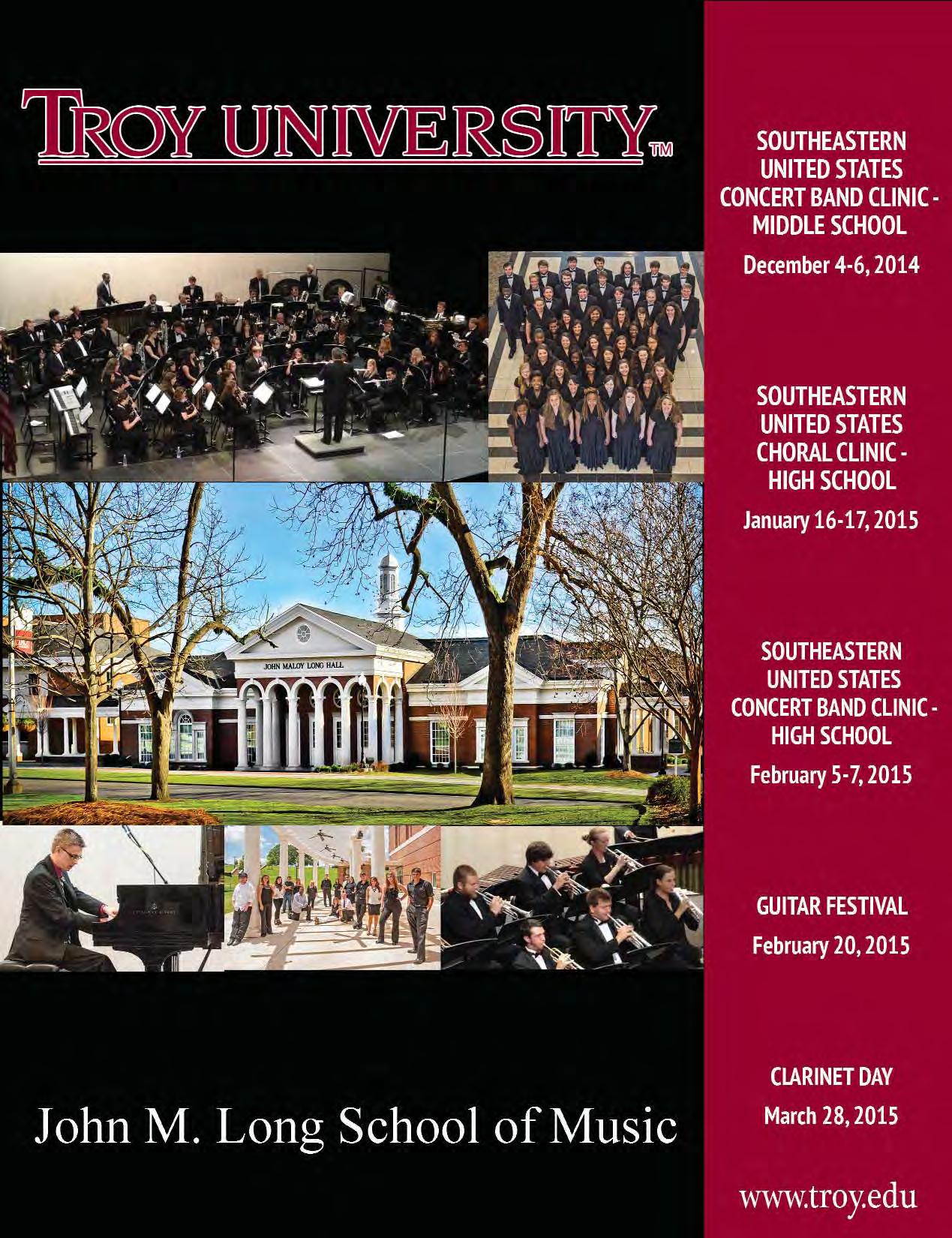

Middle School Band

Dr. Carla Gallahan is an Associate Professor of Music Education and serves as the Assistant Director of the John M. Long School of Music at Troy University in Troy, Alabama. She received the Bachelor of Music Education Degree, Master of Education in Music, and the Doctor of Philosophy in Music Education from Auburn University. As a member of the faculty at Troy University, her responsibilities include teaching music education courses, instructing the horn studio, and serving as Coordinator for Undergraduate Music Education Internship. Dr. Gallahan is the Executive Director for the Southeastern United States Concert Band Clinic and Honor Bands held at Troy University. Her teaching background includes eighteen years experience in the Alabama public schools. Dr. Gallahan is the Recording Secretary for the Alabama Music Educators Association and former chairman of District VI of the Alabama Bandmasters Association. She was selected to Who’s Who Among America’s Teachers and Outstanding Young Women of America, has been chosen as Auburn Junior High School Teacher of the Year, Auburn City Schools Secondary Teacher of the Year, and has served as a clinician and adjudicator throughout the Southeast. Her professional affiliations include the National Association for Music Educators, Alabama Music Educators Association, Alabama Bandmasters Association, and Phi Beta Mu.

Dr. Kenneth G. Bodiford has served as the Director of Bands and Assistant Professor of Music at Jacksonville State University in Jacksonville, Alabama for the past twenty years. He earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Music Education at Jacksonville State University, his Master of Music in Music Education and Wind Ensemble Conducting degree at East Carolina

University and his Doctorate of Musical Arts in Instrumental Conducting degree from The University of Alabama. Dr. Bodiford is the conductor of the Jacksonville State University Chamber Winds, which is the top performing wind ensemble at the university. This ensemble has performed for regional and national venues such as the Alabama Music Educators Conference and the Bands of America Concert Festival Regionals. The ensemble also performs on campus and throughout the northeast Alabama and

Richard L. Saucedo White Band

Georgia regions. Dr. Bodiford is also the director of the internationally known “Marching Southerners.” Under his leadership, The Marching Southerners have grown from approximately 144 members to a membership in excess of 450. They have been included in the Congressional Record of The 111th Congress U.S. House of Representatives for their production, “Of Thee I Sing,” performed in Gubernatorial, and Presidential inaugural parades as well as the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and most recently, were chosen to lead the 2012 London New Year’s Day Parade. Dr. Bodiford also served as the Executive Director of the Spirit of Atlanta Drum and Bugle Corps (JSU Spirit) from 2001 until 2007. Under his leadership, the corps consistently ranked among the elite top twelve corps in the nation at the DCI World Championships. As well, he was appointed to the staff of the U.S. Army All American Marching Band that performs at the U.S Army All American Bowl. In addition to his Director of Bands responsibilities, Dr. Bodiford teaches the instrumental conducting courses at the university and maintains a busy national schedule as a clinician, adjudicator and guest conductor. Most recently, Dr. Bodiford was nominated for the 2013 Music Educator Award

Richard L. Saucedo is currently Director of Bands, Emeritus after retiring from the William H. Duke Center for the Performing Arts at Carmel High School in Carmel, Indiana. During his 31-year tenure, Carmel bands received numerous state and national honors in the areas of concert band, jazz band and marching band. The CHS Wind Symphony performed at the Bands of America National Concert Band Festival three times (1992, 1999, and 2004) and was named the Indiana State Champion Concert Band in 1999 and most recently in 2013. The group also performed at the Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic in Chicago during December of 2005. The Carmel Jazz Ensembles have won numerous awards at jazz festivals in Indiana and throughout the Midwest. The Carmel Marching Greyhounds have finished in the top ten at the Bands of America Grand National Championship for the past 15 years and were named BOA National Champions in the fall of 2005 and again in 2012. The Marching Band has been an Indiana Class A State Champion four times in recent history. The Indiana Bandmasters Association named Mr. Saucedo Indiana’s “Bandmaster of the Year” for 1998-99. Mr. Saucedo was recently named the “Outstanding Music Educator” in the state of Indiana for 2010 by Mr. Saucedo travels throughout the country as an adjudicator, clinician and guest conductor for concert band, jazz band, marching band, and orchestra. He is currently music coordinator as well as the brass composer/arranger for the Blue Stars Drum and Bugle Corps in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Mr. Saucedo did his undergraduate work at Indiana University in Bloomington and finished his master’s degree at Butler University in Indianapolis. He is also an aviation enthusiast and a

certified private pilot. Mr. Saucedo is married to his wife Sarah and is most proud of his daughter Carmen, who is about to begin her teaching career after studying elementary education at Ball State University. His son, Ethan, is currently in 2nd grade and loves music and basketball.

Robert W. Smith is a Professor of Music and Coordinator of the Music Industry Program in Troy University’s John M. Long School of Music. In addition to his teaching responsibilities, he is one of the most popular composers in the world today with over 800 published works. The majority of his work was published through his long

Robert W. Smith Red Bandassociation with Warner Bros. Publications. He is currently published by C. L. Barnhouse and the RWS Music Company. Mr. Smith’s works for band and orchestra have been programmed by countless professional, university, and school

ensembles throughout the North America, Europe, Australia, South America and Asia. His music has received extensive airplay on network television as well as inclusion in multiple motion pictures and television productions. His “Into The Storm” was featured on the 2009 CBS Emmy Awards telecast for the HBO’s mini-series documenting the life of Winston Churchill. Mr. Smith’s teaching responsibilities at Troy University are focused in media composition, audio and live event production, publishing and entrepreneurship.

Wednesday, April 15, 2015

All-State Solo Festival (University of South Alabama)

Times TBAWoodwind, Brass, and Percussion Preliminary Competition

7:00 PMState Solo Festival Concert – Recital Hall

Thursday, April 16, 2015 (Mobile Convention Center)

1:00 PM – 7:00 PM

1:00 PM

2:00 PM

5:30 PM

6:30 PM – 9:30 PM

Exhibits Open – (North Exhibit Hall)

Directors Meeting – (107 A & B)

Auditions begin

Audition results posted

Rehearsal

Red Band (West Ballroom)

White Band (201 B, C, D)

Blue Band (204 A & B)

Middle School Band (202 A & B)

7:00 PM – 9:00 PM

ABA Board Meeting (107 A & B)

12:00 AMCurfew for all participants. Directors are responsible for their students.

Friday, April 17, 2015

8:30 AM – 11:30 AM

8:30 AM – 5:30 PM

9:00 AM – 10:00 AM

10:15 AM – 11:50 AM

12:00 PM – 1:30 PM

12:00 PM - 1:15 PM

12:30 PM - 5:00 PM

Exhibits Open – (North Exhibit Hall)

Rehearsal (All Bands)

ABA General Business Meeting (107 A & B)

Audition Manager Training (107 A & B)

Lunch on site for all participants (concourse)

Phi Beta Mu Luncheon (106 A)

Exhibits Open – (North Exhibit Hall)

2:00 PM - 3:00 PMAll-State Music Review Committee (107 A & B)

8:00 PM

University of South Alabama Host Night Concert (Saenger Theatre) 12:00 AMCurfew for all participants. Directors are responsible for their students.

Saturday, April 18, 2015

8:00 AM – 8:45 AMMiddle School Rehearsal (Mobile Civic Center)

8:45 AM – 9:30 AMBlue Band Rehearsal (Mobile Civic Center)

8:45 AM – 9:45

AMABA Board Meeting

9:30 AM – 10:15 AMWhite Band Rehearsal (Mobile Civic Center) 10:00 AM – 10:45

AMABA Business Meeting 10:15 AM – 11:00 AMRed Band Rehearsal (Mobile Civic Center) 1:00 PM

PM

All-State Band Concert (Mobile Civic Center)

AMEA In-Service Conference/All-State Jazz Band

January 22-24, 2015 - Renaissance Montgomery Hotel at the Convention Center

All-State Solo Festival

April 15, 2015 - Location TBA

All-State Band Festival

April 16-18, 2015 - Mobile Convention Center

Summer In-Service Conference

June 23-25, 2015 - Hampton Inn and Suites, Orange Beach

October 3, 2014 Elementary Music Festival, Samford University, Dr. Michele Champion and Mr. Ken Berg

October 4, 2014 AMEA/ AOSA Fall Workshop, Gwin Elementary School Dr. Michele Champion and Mr. Ken Berg

October 26-29, 2014 NAfME National In-service Conference, Nashville, TN

November 5-8, 2014 AOSA Professional Development Conference, Nashville, TN

January 22-24 AMEA In-Service Conference, Renaissance Montgomery Hotel and Convention Center

October 11 - Collegiate Summit - University of Montevallo

January 22 - 24, 2015 AMEA Conference, Renaissance Montgomery Hotel and Convention Center

All State Audition excerpts posted online - August 11, 2014

All State Audition Registration Deadline - September 30, 2014 Composition Contest Deadline - October 1, 2014

All State Results Posted online - November 17, 2014

All-State Scholarship Application Deadline - December 1, 2014

All-State Festival - February 12-15, 2015

25 years of Continuous Membership and increments of 5 years after that (See page 57 for a list of names)

byTimothy Oliver

byTimothy Oliver

On a warm, but pleasant summer day in July 2010, one of my colleagues from the theater department and I were enjoying conversation over coffee about one of our upcoming collaborations. During our visit, I mentioned my experiences at a concert that I attended while at a professional conference earlier that spring. It was a collegiate wind ensemble concert, but during the presentation theatrical elements such as lighting and staging of musicians were utilized to create a memorable and satisfying performance. Without the slightest hesitationmy colleaguestated that it was obvious those musicians knew how to manipulate aesthetic distance. I sat there stunned and agog in a mixture of confusion and awe. I knew what the words aesthetic and distance meant, but putting the two together was a new experience for me. Moreover, the fact my colleague spoke this compound term so casually but with utter conviction, demanded that I begin an investigation that has since altered my views as a music educator and conductor.

The next dayI initiatedmy research on aesthetic distance and quickly learned there are several different interpretations and applications of this concept. Numerous artistic genres - music, theater, visual art, dance, literature, film, and electronic media – utilize the concept of aesthetic distance. There are also three prerequisite distances, or some might call them conditions, all of which are intuitive, in order for aesthetic distance to be realized. The first is spatial distance, or the physical distance between the art object and the person interacting with the art. The physical environment in which we attempt to engage with music is most often associated with this type of distance. Secondly, temporal distance, the distance involving time and our experience with music. This type of distance is applicable to a single or often multiple musical experiences over time. Temporal distances tend to affect our musical views more than spatial distances. The third and final

prerequisite is psychical distance; a concept pioneered by Edward Bullough in 1912. Psychical distance is a psychological blending of our ability and willingness to be both personally and intellectually involved with music. Sometimes we make a conscious effort to be available to the music, while other times the music “chooses” us and demands our attention. In an effort to synthesize and extrapolate into a musical context various definitions and applications of aesthetic distance, I offer the following interpretation. Aesthetic distance is finding equilibrium among the ways we feel and think about musicassuming that we are spatially, temporally and psychically available to be engaged with music.

We have all heard the adage, “You can’t see the forest for the trees.” The implication of this notion,and its opposite, is perspective. Consider that following. Think back to a particularly satisfying performance you experienced as a conductor, performer, or audience member. What are your first memories of that performance? Did the performance move you emotionally? Were you in awe of the technical ability displayed? Perhaps it was a mixture of both? Whatever your answers, these questions can begin to raise your awareness of aesthetic distance.

Perhaps one of the most interesting sources on this topic is the 1961 article “Distancing” as an Aesthetic Principle by Sheila Dawson.

perfectly appropriate that each student will have varying degrees of aesthetic distance, provided they are willing and able to engage with the music.Each one of them brings their own biases and personal history to any potential aesthetic opportunity. Additional, the art object in question also has a significant influence. All students will not like,or experience to the same degree,every piece of music we as music educators offer to them. Furthermore, it is conceivable and perhaps even expected, that aesthetic distance changes over time regarding a particular piece of music.How many times have we or our students grown tired of a musical selection because it is played too often? In contrast, how often have we had the experience where our appreciation of a piece of music deepens with the passing of time? Again, the concept of temporal distance affects our musical views.

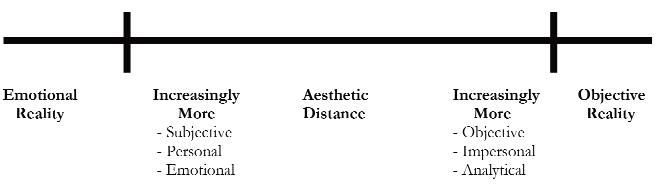

In searching for equilibrium of distance, a useful construct might be to think of a continuum which terminates on each end with either emotional or objective reality. Toward the left side of the continuum resides a more subjective perspective, personal attachments, or emotional content. While on the right side you find a more objective attitude, impersonal connections, and a logical, analytical mindset. Somewhere in between, but without a specific location or proportion, is the equilibrium, the aesthetic distance.

Among Dawson’s many assertions is that there is no optimum or correct aesthetic distance for each person, each artistic object or each occasion. When considering the students in our ensembles and classes, it is

It is important to note that when reality intrudes it violates aesthetic distance and compromises the experience. Reality and the prerequisite psychical distance are incompatible. Reality may take an emotional

or objective form. An example of emotional reality is when the person engaged with the music becomes overwhelmed with emotion, possibility to the point of physical reaction. Or,some music, and other artistic materials for that matter, may be inferior or offensive to some individuals which also precludes their willingness to engage. At the other end of the continuum, examples of objective reality might include substandard musical execution or poor environment. Consider for a moment a cell phone ringing, or a person coughing/clearing their throat at what always seems to be the most delicate moment of a concert. That is an all too frequent instance of objective reality!

Dawson and numerous other philosophers refer to areas outside of aesthetic distance along this aforementioned continuum as “underdistanced” or “overdistanced.” As you might surmise, one may be considered “underdistanced” or too close to the music when the emotional and subjective domains dominate the perspective of the individual. If the only thing a student can describe about a musical experience is the way it made them feel, chances are they were “underdistanced.” Conversely, one is considered “overdistanced” or too far from the experience when the music is perceived only through a dispassionate and objective perspective. As a general rule, younger musicians or individuals without a degree of musical education or experience will tend more often to trend toward under-distancing. Consider how excited students can be in a beginning band class about everything that goes on. More mature musicians or musically educated individuals will often trend toward over-distancing. It is worth reiterating that the exact amount of distance and proportions of areas representing underdistanced, aesthetically distanced, and over-distanced will vary for each person, each piece of music, and each occasion. It also seems reasonable that the degree and variety of distancing is a constantly moving variable on a continuum of experience within each performance.

Aesthetic distance according to Donald Stewart also has pedagogical implications. He indicates that students must understand the principles of aesthetic distance, perhaps even unconsciously, if they are to respond to critiques of their work. As music educators,

we know that some students take criticisms of the work personally. They note the grade or score and internalize it as a reflection of their personality rather than an assessment of their work. Stewart suggests that if students would achieve a measure of aesthetic distance they would derive greater benefits of the offered critiques.

As music educators we have dual relationships with our art because of the technical knowledge and expertise we possess as well as the appreciative, creative and emotional content of our performance or interpretation. It is expected that musicians can and often do purposefullymanipulate their aesthetic distance quickly and in a complementary fashion, which in turn may affect the aesthetic distance of others.We have the ability to be completely immersed in a musical moment, but retain the ability when needed to instantaneously shift our attention other cognitive domains.

I would like to suggest that in order to diversify the perceptions of our students about music we need to provide our students the means to facilitate them to also see both the forest and trees. Stated different, by raising our own awareness of aesthetic distance and deliberately altering it, we can design and implement strategies and conditions that offer our students more opportunities to explore how they think and feel about music, again provided they are available to be engaged in the experience.

To that end, I offer the following ideas which have been successfully implemented with ensembles at a variety of levels. The goal is to find equilibrium in how we feel and think about music. These suggestions may also be adapted for use with audiences too. You may already employ some of these ideas, but I hope that you will now utilize these them while being mindful of aesthetic distance.

Conducting is an efficient, non-verbal, and musical way to alter aesthetic distance. While a lengthy discussion about conducting is beyond the purview of this article, consider the following questions. How do you start the ensemble when rehearsing? Do you count-off? Counting off when you start your ensemble not only is counterproductive to expressive conducting, because you are

training your students that they don’t need to watch you, it automatically increases the aesthetic distance. How much eye contact do you offer your ensemble? Your eyes are the most expressive part of your face. Eye contact is a great way to reduce aesthetic distance. Good eye contact also is a great help with classroom management. How expressive and varied is your gestural vocabulary when conducting? Providing your ensemble with only a mirrored beat pattern most likely will not help to inspire or reduce the aesthetic distance of your students.

Perhaps at no other time in music history has it been easier to interact with guest artists, which could include composers, soloists, conductors and other ensembles. Technology and social media have been very helpful in this regard. For example, I have yet to interact with a composer who did not enjoy hearing that we were performing their music. Very often they are enthusiastic about receiving email correspondence, commenting on recorded rehearsals or attending them virtually through platforms such as Skype, and when their schedules permit and resources allow being a composer-in-residence. These are great opportunities to alter aesthetic distance in either direction, but usually I have found it brings students much closer, emotionally to the music but tempered with objective insights that only the composer can bring.

One of my mentors at Florida State University, the late Dr. James Croft had a saying which has always stuck with me and been a staple of my teaching, “By their forms,shall ye know them.”Knowing the form of a composition is essential to effective rehearsals. If you know the architecture and structure of a piece, when you rehearse it, you can logically and systematically take it apart and put it back together. When students also know the form, they become more adept at listening for new or recurring thematic, rhythmic and harmonic patterns resulting in opportunities to increase their aesthetic distance. The same is also true of intonation tendencies. When

students know who has the third or seventh of a triad, both of which usually require significant adjustments to achieve just intonation, that also can alter their aesthetic distance.

With the pressures of upcoming performances and finite amounts of rehearsal time, it can be very tempting to forego the time required to ask students meaningful questions about the music. From a classroom management standpoint, proctoring a classroom discussion, particularly with the logistics involved with most ensembles,can be challenging. It can also be well worth the effort. Questions do not need to be abstract or existential, but can be as simple as, “Please raise your hand if you sing/play the melody.” Over time the questions can evolve into more complex items. One of my favorite questions, which does creep into the existential realm, is, “Why do you think the composer would write this particular item in this fashion?”

Whatever their responses, it is important to be open to their answers since typically, but not always, this can be a way to decrease the aesthetic distance of the students.

Again, taking the time to listen to music in rehearsals can sometimes fall to the bottom

of our list of priorities. However, when comparing interpretations of works, or even sections of works, hearing other musical opinions often makes us question or reaffirm our own. Further, recording rehearsals and performances then listening to them in class can be very illuminating. Very often it serves as an opportunity to increase the aesthetic distance, because the recording isn’t biased and doesn’t lie. It is objective thus providing students with not only an aesthetic distance alteration, but also an opportunity for authentic assessment.

Talk to the audience during a concert

An educational festival for elementary, middle, and high school students in band, choir, and orchestra

As I once explained to my daughter when dining at a local Mexican restaurant when she asked about the bottle of hot sauce on the table, a few drops can literally spice up your meal; too much though can have disastrous consequences. The same is true for interacting with the audience at a concert. Some brief comments offered to the audience about some feature of a piece to be performed, a short playing of an important theme, or just a personal story germane to the piece can be a very effective way of altering the aesthetic distance of your audience. Presumably, you have already done this with your students. While I don’t talk before every piece at a concert, I continue to be surprised by the number of audience members who tell me that they enjoyed a particular remark about a piece or that it helped them to better understand the music. While I know I am in the minority, I think the model which many professional and collegiate conductors employ of not talking to the audience is a mistake. This only serves to increase the distance of our audience at a time when our profession definitely needs our audience to feel connected and invested in what we are doing as musicians and educators.

www.SMMFestival.com or call:1-855-766-3008

Aesthetics is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with the nature and appreciation of beauty. It can be a daunting subject to consider since its roots stretch back to Aristotle and beyond. However, as esteemed music educator Edward Lisk noted in the previous issue of ala breve, “Through music study, students experience the beauty of musical expression….No other discipline

addresses such ‘living or life priorities’ in the manner which music does.” Attempting to alter the aesthetic distances of our students doesn’t mean we dictate their responses to music;rather it provides students the opportunity to diversify the way in which they experiencemusic. As music educators we have the capability of facilitating and presenting wonderful and artistic performances and musical experiences;carefully and thoughtfully balanced with objective precision and attention to technical details while offering our students, our audiences, and ourselves, the opportunity to be musically and emotionally vulnerable and therefore completely present in each moment. Admittedly, this is a difficult, perhaps even a little scary, but tremendously exciting goal worthy of our continuing efforts.

Ben-Chaim, D. (1984). Distance in the theatre, the aesthetics of audience response. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

Bullough, E. (1912). ‘Psychical Distance’ as a factor in art and as an aesthetic principle. British Journal of Psychology, 5, 87-117.

Dawson, S. (1961). ‘Distancing’ as an aesthetic principle. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 39(2), 155-174.

Stewart, D. C. (1975). Aesthetic distance and the composition teacher. College Composition and Communication, 26(3), 238-243.

audition Dates:

saturday, november 8, 2014

saturday, February 14, 2015

saturday, march 14, 2015

saturday, april 4, 2015

additional Dates available by request

Degrees:

bm with Concentration in music education (Instrumental and Vocal)

b m with Concentration in Performance (Instrumental and Vocal)

b m with Concentration in elective studies (business or specific Outside Fields)

mm with Concentration in music education (Instrumental and Vocal)

m m with Concentration in music Performance (Piano and Vocal)

m m with Concentration in Collaborative Keyboard

the university of south alabama Department of music, through its innovative curriculum, empowers professional musicians, music educators, and those who wish to enrich their lives through the arts. the Department serves the needs of the university to promote general education and to provide a vital cultural link to the great state of alabama and to the Gulf Coast region. Its excellent facilities and faculty, promotion of technology, and dedication to life-long learning provide a wide spectrum of experiences for both the student and the community.

enseMbLes

Instrumental ensembles

Wind ensemble

symphony band

symphony Orchestra

string ensemble

Jaguar marching band

Jaguar Pep band

Jazz ensemble

Tips That Click this month explores what goes on in the first minutes of band class in outstanding programs. I was able to sit down with three experienced teachers for a few minutes and “pick their brains” about what has worked well for them in efficiently warming up and developing technical skills with their bands.

Randall Key is the Band Director at Hartselle High School, where he has served for 11 of his total 21 years teaching. He previously served as Assistant at Cullman High School. “We begin each rehearsal with intervals, the five note scale legato, slurred, marcato, and then 12 major scales. After the scales we use Symphonic Warm-Ups

For Band by Claude T. Smith throughout symphonic season. We also use rhythm pages 40 and 41 from Exercises for Ensemble Drill by Raymond C. Fussell. Starting 2nd semester we add 42 Chorales For Band edited by Philip Gordon. I like the Claude T. Smith book because it has rhythm pages, etudes, and contemporary chorales. The etudes and chorales are written in every key and it challenges band students in several different areas”.

purchase individual copies. It really has everything I need and I am so used to it. I generally start it in the second year. I introduce lip slurs and the scales and rudiments and keep expanding these all year. There are also interval studies and short etudes in all keys so we add these as the year progresses. I also utilize the chorales and tuning exercises. There really is a little of everything in this great book as it also includes dynamic studies, a glossary and a short theory section. I don’t do the same regimen exactly the same way from year to year. I adjust it to fit the strengths and weaknesses of each class and what’s going on. The book is suitable for use through high school, so I like that students can buy one inexpensive book and keep it through the years.”

the student could make a tangible connection. I also used Section 9 and 10 of this book to develop and reinforce rhythmic skills and prepare for sight reading. Again, this is using unison melodic material with the idea when you get matching energy tone quality form each individual in the ensemble, then the chorales will have better balance and sonority. I used the chord section (Section 1) of Ensemble Drill, but really like using Chorale Masters by James Curnow for chorale work. This book presents the melody part as a unison line that can be rehearsed before presenting the harmonization. I would use just a phrase or fragment of the chorale so that the students could concentrate on making all elements sound balanced and perfect”.

Amanda Ford is Band Director at Pike Liberal Arts School in Troy. She has served as an ABA district officer and adjudicator and taught high school and middle school in the public schools of Alabama earlier in her career. Her experience spans over 27 years. “The book I use all year is I Recommend by James Ployhar. Tony Whetstone turned me onto it years and years ago. It is still only $6.00 a book, so I have students

Carol Jacobs led bands in Jefferson County for over 15 years, most notably at Bragg Middle School and Mortimer Jordan High School. She still serves as an adjunct instructor and private lesson teacher for several programs in the Birmingham area. “ I used a number of different books during the early years of my career and found that each had its strengths and weak points. I later took a “cut and paste” approach and created my own handout using sections from several sources. One book that I always utilized is Exercises for Ensemble Drill by Fussell. I would use the scale exercises (Section 8) daily and try to find a “form” that the students liked and drilled this extensively, being very picky on how it was being performed. The variety of things that can be explore with this one section is very extensive. I tried to employ the keys that were being used in the literature we were performing so

Hopefully the advice given above will generate some ideas that will help all of us or perhaps reinforce what you already do daily. All three directors I interviewed emphasized the importance of not using the routines as an end in themselves; the concepts taught must be intentionally transferred to the literature being prepared or the time is essentially wasted. There have been many warmup materials added in the last few years, but I find it interesting that successful teachers seem to revert back to the “tried and true”!

Rho Chapter of Phi Beta Mu International Bandmaster Fraternity is committed to the improvement of bands and band instruction in this state. Comments on this column and ideas for future columns are welcome! Please email: pemin@mac.com,

For professional choral musicians, the good news is that every year we increase professional knowledge of how to best teach and conduct our choirs. This is also the bad news, however, as it requires atime investment to learn about and possibly implement new methods and materials. Often new knowledge is gleaned from the music education research community, or highly successful practitioners, or composers and publishers who provide new music options, or graduate study, etc. The question then becomes: How can we best disseminate new information so that teacher/conductors can make informed decisions and perhaps prioritize what is most important? Complicating the process of defining priorities is that they may very well differ among schools, dependent on variables which impact student learning and success: student population demographics, school size and infrastructure, administrative and parental support, available funding, etc. The purpose of this paper is to provide some suggestions for prioritizing those things that have strong impact on teacher and student success in middle and high school programs that include developmental groups, those just learning to become choral performers.

Research activity among choral scholars has lagged behind other musical and pedagogical research for several decades; however, within the last 15-20 years, choral research activity has greatly increased. Information on a wide array of choral topics is readily available electronically, reflecting a breadth and depth of study. As young teachers prepare for careers in choral music and pedagogy, they likely enter knowing the professional current “best practice” gleaned from their university curricula. Such topics as teacher effectiveness, strategies for establishing instructional pace in rehearsal (a great deterrent for classroom management problems), vocal pedagogy methods that contribute to healthy vocal training, programs that develop students (such as leadership development), specialized training to embed critical thinking instruction into rehearsals, teacher leadership development that supports professional participation, creating competence in teaching

students to perform expressively, new methods for attaching musical learning to performance activity (concepts, skills, etc.), as well as and many other important topics. Teachers not recently graduated may lack some of this training, and could be at a disadvantage when functioning within a school environment built around current knowledge and practice. Thus, it seems important to provide opportunities for professional growth, perhaps even above and beyond typical district in-service programs. Staying current in any field is a lifelong challenge, and teaching choral music is no exception. It is not enough to acknowledge that new information exists just because it is found in scholarly music research journals that all can access. It is unrealistic, however, to assume that music teachers will independently find this needed information—-let’s not forget that dragging home after a long teaching day probably does not lead to reading music research journals until 2:00 am. If true dissemination is desired, then some method of delivering knowledge and training to teacher/conductors is required beyond just suggesting particular journals to read.

The phrase “Don’t try this at home”, often used in television commercials involving some daring deed, suggests that a specific, controlled environment is required for safely accomplishing said task. In the case of choral teachers remaining fresh via learning new teaching knowledge and practices, I believe similarity exists: there must be a safe, nurturing environment to successfully acquire new pedagogy. Perhaps a “translator” to connect research findings with busy teachers might support success. Such things as earning a graduate degree, taking a single graduate class or summer workshop, attending professional conferences with carefully targeted sessions aimed at new information,or any other opportunity that provides a specialist to inform, encourage, and perhaps inspire is likely a helpful choice. This means money, if a school district is not supporting the event, but it is money well spent. Consider it an investment in yourself, and we are all worth it. The following text offers guidance for (1) choosing repertoire that enhances the probable

by Judy Bowers, Florida State Universitysuccess of singers who are novice, or who just lack experience, training, or exceptional ability, and (2) creating a possible strategy for empowering novice choral students to sing expressively.

Structuring successful learning environments has been a prominent topic in for several decades, and Madsen &Kuhn (1994) have long recommended an 80/20 success ratio between achievable and challenging tasks. This ratio implies students should achieve success approximately80percent of the time, but 20 percent of the task should represent a challenge. The 80/20 ratio links directly to motivation, because if a student succeeds too often (tasks are too easy) or fails too often (tasks are too challenging), they can become bored, or lose interest and cease trying. Frequent success paired with occasional failure is one formula for maintaining high student engagement that can aid teachers in establishing a desired rehearsal environment. Literature selection for beginning middle/high school singers, however, may well be the number one variable affecting teacher success with developing choirs.

Repertoiremust be accessible for singers to maintain a reasonable success rate. However, middle/high school developing singers often reject appropriate music taken from elementary school curriculathat might seem childish or immature, so step one is that teachers must work to select age-appropriate singing material, even in the early stages of singing development. That being said, one elementary teaching strategy that should not be omitted with beginning singers who lack training and experience is the Independence Hierarchy (Bowers, 1999). Keeping students singing increases their engagement, supports well-paced rehearsal instruction, and serves to motivate when success is accomplished. The Independence Hierarchy structures sequenced, successive progress from unison singing through independently singing part songs (these often have identical rhythm and text, with difference occurring only among pitches—-this music is the hardest for developing singers to manage yet many

teachers begin with this music). Voicing the choir to create sections and then moving immediately to advanced choral literature is likely counter-productive because it may require extended drilling (banging out the harmony notes “one more time so you really have it”) that can still resultin students losing the parts when sung together. In addition, rehearsal pacing, classroom management, and classroom climate generally deteriorate in rehearsals involving inappropriate music. Thus, literature selected for novice middle/high school choirs, or developmental groups of all ages, actually, plays a huge role in rehearsal success. The figure below provides an adaptation of the sequence elementary music teachers use to establish harmony singing across time. There is ample good music available that reflects each step. Teacher judgment must determine how long a choir should stay at each level. Some students will be able to move toward singing step ten in a matter of weeks; these students are likely bright, talented, and have experience using their voices. In contrast, some choirs may not get through all steps for some or all of a school year and that’s also fine as long as they progress.