TheAkhmatovaReview

I.SectionOne:Art,Belief

II.SectionTwo:ForeignPolicy,

I.SectionOne:Art,Belief

II.SectionTwo:ForeignPolicy,

EditorandChief,SamanthadeVerteuil-Undergraduate studentwhohasstudiedattheUniversityofEdinburghand theUniversityofToronto

ManagingEditor, AlexaFrcek-Undergraduatestudent studyingattheUniversityofEdinburgh

Co-LeadEditor(Art,Belief&Custom),ErinHardyUndergraduatestudentstudyingattheUniversityofUtah

Co-LeadEditor(ForeignPolicy,Politics&Law),Daria Korovkina-Undergraduatestudentstudyingatthe UniversityofEdinburgh

Copyeditors, -LoganPizzeck-Undergraduatestudentwhohasstudied attheUniversityofOklahomaandtheUniversityofNew Orleans -MichaelBretzel-Undergraduatestudentwhohasstudied attheUniversityofMinnesotaTwinCities

AsherGibbens-Postgraduatestudentstudyingatthe UniversityofEdinburgh.BornintheUnitedKingdom.

AfraKayhan-Undergraduatestudentstudyingat PamukkaleUniversity.BorninTurkey.

VinayashreeChharia-Undergraduatestudentstudyingat GulfMedicalUniversity.BorninIndia.

NoorZohdy-Undergraduatestudentstudyingatthe UniversityofStAndrews.BorninWales.

IvaZivaljevic- Undergraduatestudentwhohasstudiedat UniversityCollegeLondon,theUniversityofToronto, andtheNationalUniversityofSingapore.BorninSerbia.

BlairShang-Undergraduatestudentwhohasstudiedat SciencePo,theUniversityofHongKong,theUniversity ofToronto,andCharlesUniversity. BorninSouthAfrica.

PhotoCredits:

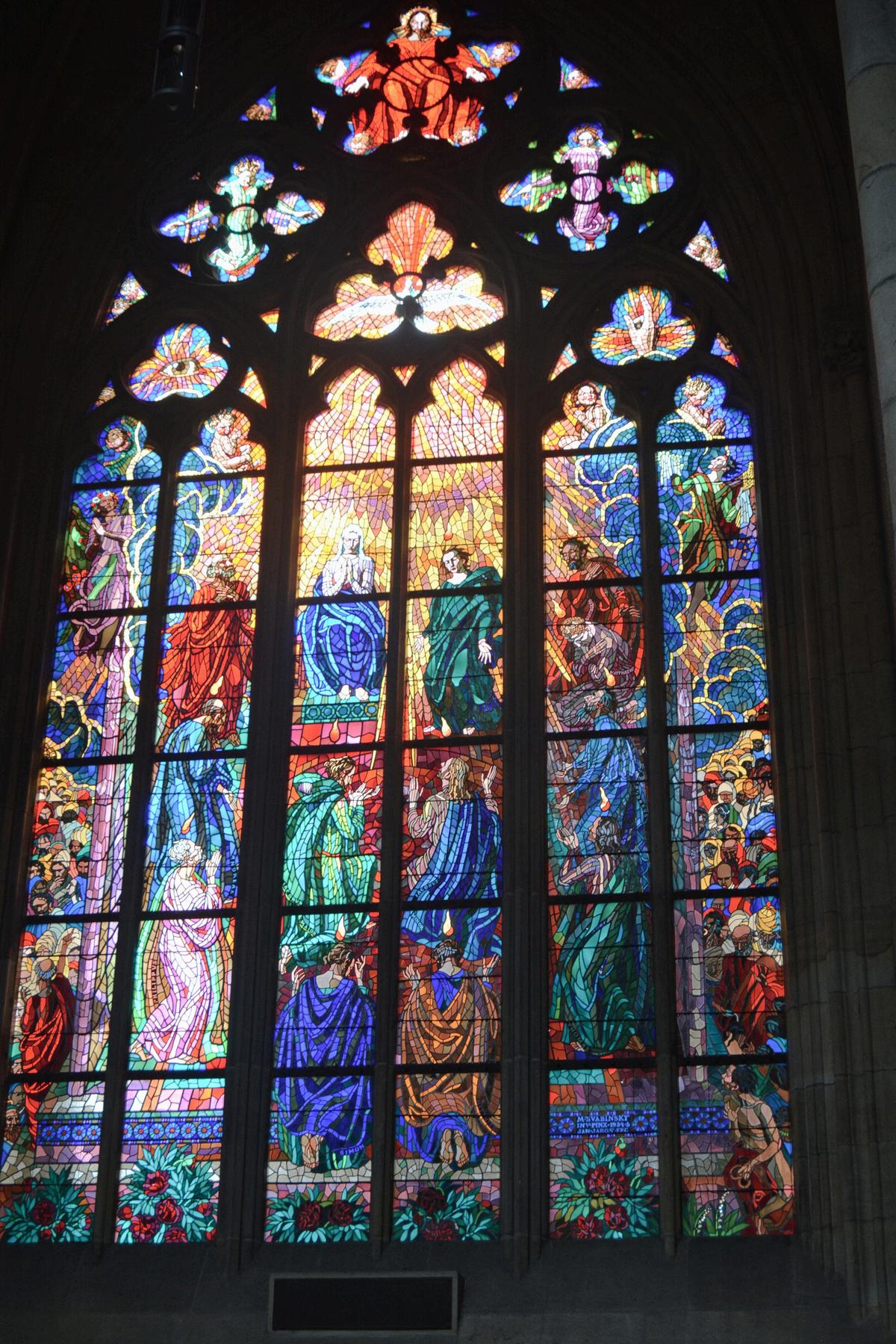

PhotographerMatiasNaess-Undergraduatestudentwho hasstudiedatSciencePo,theUniversityofToronto,and MasarykUniversity. BorninNorway.

Welcome to the debut volume of the Akhmatova Review. This has been a truly internationaledition,withsubmissionsfrom over six countries and nine universities worldwide.Ithasbeenanhonortohostsuch a diverse collection of pieces in the first undergraduate Slavic or Eurasian studies journalinScotland.Onthispoint,Iwould like to thank our authors, poets, and photographers, as without their work, this journalcouldnotexist.

Thisedition,particularlyinreferencetothe cover art and theme, has been heavily inspired by Sirja-Liisa Eelma, an Estonian artist, and by the city scenery of Tallinn. This journal aims to be geographically inclusive, and while Estonia and the other Baltic states are rarely included in the conceptionof‘Eurasia,’thisreviewhopedto givethemspace,asinScotland,thereremain few publication sources for undergraduates interested in that region. I hope all our readers take the time to read the poem Cīrulputenenisinthisedition.Basedonthe Latvianword,thispoem,giveninEnglish, ties in lovely images of the Baltic region, whichissetinsnow.

AswarwagesinUkraine,itisimportantto recognize the devastation, crimes against humanity, and moral abhorrence that have occurred since the Russian invasion freedomtoUkraine.

I would also like to raise attention to and condemntheactsofongoingpoliticalviolence inBelarus.ThebraveryofBelarusianlawyers, humanrightsdefenders,andmembersofcivil society continues to amaze me. All the way fromScotland,weseeyou,andwebelievein you.

To the protesters for democracy in Georgia, westandwithyou.

Astheregionwestudyremainsuncertain,itis important to engage in the debates and conversationsofourtime.Ibelievethearticles wehaveselectedforthiseditiondojustthis.

Again, it was an honor to be part of its creation,andIamexcitedtoseethedirection thisjournaltakesasitishandedofftoanother Editornextsession

Allthebest,

SamanthadeVerteuil Founder&EditorandChief

By:AfraKayhan

TranslatedfromtheoriginalTurkish

Imisstheolddays, Whenmotherbathedme, Braidedmyhair, Toldmesoftly,“Don’tworryaboutyour life.”

Imisstheolddays,

Whenfatherwalkedin,sosleepy. Butstill,hesmiledwhenhesawme

Imisstheolddays, IwishIhadaclocktogobackintime

Andstaythere‘tilIdie

By:AsherGibbens

AshandiceentwinedasEastwardwindsmoaned AcrosspineforestsandUralMountains

Thetundraclutchedathousandthousandtons five-footgaugesteel-greytracks,fromMosco ToManchuria,byLakeBaikalwherepacked Snowsubduesregalwater,fromIrkutsk

ToUlaanbaatar,eternalbluesky

Meetsearthunderperpetualwhitesheets

Andfreshfallswashthecrimsonstainsofred

Againstwhitetoatoneutopia

DidtheKhan’ssinscursethesoilunfruitful

Andcondemnhisheirstobeforsaken FortheGeorgianbutcherthatcametocleanse

Nomadherders,yokedtocollectivefarms

Andpurgedfrombourgeoistendencies,atnight

Thesameunmovedstarsthatdulywitnessed

Thelambledtoslaughter,sheeptoshearers

Attendsfathersandbrotherstriedbytwelve Rifles,theirlipssealedandstandingbefore Thecrackingshotsthatrangacrossdarkskies

Assteamingcasingsploppedtodullsunrise Andworkersarosetowhistlesandroars

Asfactoriesblazedforonecollective Dream,heavenforgedfromiron,steel,andcoal Plumesbillowedintotheblueskythatrise Andfallasash,onsnow;FathersandSonsreturntothesteppes

Intheyearofnineteenseventy-eight,

TheGermanicmanwatchedtheraggedmutts Limpwithgashesandrummagerawoffcuts ‘Inthesweatofyourfaceyoushalleatbread’ Withchappedlipsandtearyeyesfromiceburn

HemetbrowneyesofdeepBaikalthatbrimmed

Resignation,beingpurgedofdesire

DaughterofLakeBaikaltobravehunter AndGermanicmanbuoyantonCircleStreet AsCaucasianShepherdpupatfirstmeet

InbleakmidwinterofUlaanbaatar DaughterofDiamondMoon,thebelovedsight

Whatcouldhegivetoyoupoorasaman Wereheaherdsmanwouldhegivealamb Forfaceveiledbylabourtotastedelight

Thesunandvineandwind,didtheygivewill Forhisbluegreyeyestopeerinthedepth

OfBaikalwaterandhearhisecho

AndgivehishearttoutteronWhiteHill

Thisboneofmybonesandfleshofmyflesh

ShareyouryokeandIwillgiveresttoyou

arofnineteeneighty,un theKGB,deaftolamb'sp earingclashesofSino-Vi terpillartrackstotheA nwasexpelledasspyandb

inconcretecellwithsta ngonwallsetchedbynail ickeringbulbthatdimly oorandbarefloorandbr ntsforcedintoonebody, rippledbybootsofleath haletheuntickingair,fl a,swallowedbystate’sst

mitedheroutafterthree

stsevenyearsofexile,th asnoststeelyskiesandsil cketsilos,tobecomeone veandtocherish.Ifasha crumblingUnion,could thesteppestasteeterna

Asfleshreturnsasashestotheearth

By:VinayashreeChharia

hebecameawarriorsohecouldbeason sohismothercouldsmile, theytoldhimhecouldwashthefilthfrom hisblood ifhefought,bled,andkilledenoughto satisfy.

thewallswhisperedothernames, eyesthatsawaboy, lookedfordevils, sawonlyfriends.

hetriedtocarrytheweight, apoisontohissoul, thearmorheld,butsomethingbeneathit bent.

thepathwaslaid,therolewascast, noroomfordoubt,noturningback. hehadtokeepmoving,forwardwastheway

andhopethatdeathwouldgranthimpeace, apricehe’dgladlypay

CīrulputenisisaLatvianwordforsnowmeaning,‘ablizzardofskylarks’.Ilearntitfrommymother,who isLatvian,andwhodescribeditas‘thesortofsnowfallthatcomesasasurpriseflurryonespringmorning’.

AMaymorningglimmers, Aleafcatchesflight, Turningandfluttering Amidshadowsofnight.

Thebraveleapofafawn, Thererustlesasoftwing, Moonbeamstumbledown Twinedonsilverstring.

Momentsunfolding, Nowfallingfromthesky, Ablizzardofskylarks, Whitefeathersthatfly.

Thistledownonblueice, Frostonpinkpetals, Thefawnliftsitsears Ahushofthebreeze.

Forwitheachdancingmoment, Asilentpiano,quiethands, Starlightcatchingeachspark

Thesnowflake breathless lands.

By:NoorZohdy

In an escalation of long-standing tensions, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.RealisttheorypositsthatNATO's eastward expansion provoked Russia's aggressiveactionsinUkraine,viewingthe conflict as a response to Western encroachment,whilesomeinterpretations suggest that the United States and its European allies failed to offer sufficient security guarantees to Ukraine (Mearsheimer, 2022; Edinger, 2022). While the conflict can be partially understood through these security concerns, this explanation overlooks EasternEurope'shistorical,political,and cultural context. Russia has consistently coercedUkrainesincethe1990sthrough economicpressure,territorialclaims,and election interference, revealing deeper patterns of aggression predating significant NATO involvement (Dutkiewicz & Smoleński, 2023; Person &McFaul,2022).Thispaperarguesthat constructivism comprehensively explains Russia'sinvasionofUkrainebyfocusing onthes

“Russia'sstrategic manipulationofinternational normstolegitimizeitsactions.”

ocially constructed nature of state identities and interests. It analyzes Russia's great-power identity, Ukraine’s westward identity shift, the roles of nationalism and ideological narratives in shaping public opinion and justifying aggression,and tolegitimizeitsactions.Itaddresseshow these factors interact to justify aggression,reinforcestateidentities,and challengetraditionalsovereignty.

Beyondmaterialfactors,adefiningelement ofRussianstrategiccultureisitspersistent questforgreat-powerstatus,whichremains central to its political identity and foreign policy. This ambition is rooted in Russian history,reflectedinspeechesbyleaderssuch as Putin and Yeltsin, and consistently enshrined in strategy documents since the Soviet Union's collapse (Götz & Staun, 2022).Itisconsideredexistential,forminga core part of Russia's identity and survival narrative and necessitating influence over theformerSovietRepublic(Götz&Staun, 2022;Knott,2022).Amajorfactorinthis identity is Russia's dissatisfaction with the post-Cold War order (Chafetz, 1996). NATO expansion and Western involvement in the post-Soviet space are seenasthreatstoRussia'shistoricalsphere of influence. Unlike realist views, which focusonsecurityconcerns,

“Russia'sgrievancesare deeplyrootedinitssenseof statusandidentity(Wendt, 1992).”

This is reinforced by perceptions of the West's failure to treat Russia as an equal partner, framing the EU and the U.S. as ideological and strategic adversaries undermining Russia's position as a great power(Rich,2013).

Ukraine'spivottowardtheWest, markedbyclosertieswithNATOandthe EU, directly challenges Russia's greatpower identity, which relies on maintainingUkrainewithinitssphereof influenceasasymbolofsharedhistorical andculturalunity(Feklyunina,2016).By 2023, this shift was reflected in overwhelming public support, with 85% of Ukrainians favoring EU membership and82%backingNATOaccession(IRI, 2023). Concurrently, the percentage of Ukrainians identifying as Russian has declinedpersistentlysince1991,reflected in the greater use of the Ukrainian language, the declining number of Russian-identifying populations, and the rejectionofRussiancultureandpolitical influences, further challenging Russia's narrative of unity and historical dominance (KIIS 2024; Feklyunina, 2016).

In response, Russia has reinforced its great-power identity through military actions and soft power, promoting narrativeslikethe"Russiancompatriots" framework (Götz, 2016). This positions RussiaastheprotectorofethnicRussians and Russian speakers abroad, portraying them as part of a shared cultural and historical "Russian World" and framing RussiansandUkrainiansas"onepeople" (PålKolstø,2023).

anguage initiatives and promoting the By emphasizingnarrativesofunity,alongwith Russian language initiatives and promoting the Orthodox Church, Russia soughttocounterUkraine'sidentityshift byreinforcingitsownculturalpresencein theregion(Götz,2016;Feklyunina,2016).

As such, Russia's actions in Ukraine reflect the socially constructed nature of stateidentityandinterests.Itsgreat-power identityisshapedbyhistoricalandcultural narratives,particularlyUkraine'ssymbolic importance, as central to Russian civilization. This identity is relational, relying on Ukraine's alignment with Russia's sphere of influence to sustain its self-perception (Wendt, 1992). Ukraine's pivot to the West, marked by closer ties withNATOandtheEU,challengesthis identity, creating a perceived threat to Russia'sstatus,whichmotivatesitsforeign policy decisions. Russia's subsequent actionsreflecttheconstructivistconceptof norminternalization,wherenormsbecome embeddedinidentitythroughsocialization (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998). Its relationalidentitydrivesactionsaimingto reassert its influence over the post-Soviet space, reinforcing its self-image as a dominant actor in the region and a challenger to the Western-led international order. By framing the West asthe"other"andpositioningitselfasthe protectorofsharedSlavicheritage,Russia reinforcesitsself-imageasagreatpower.

This reflects a norm cascade, where its entrenchedidentityshapesforeignpolicy asanaturalresponsetoperceivedthreats (Finnemore&Sikkink,1998).

Russiahasstrategicallymanipulated international norms to justify its actions in Ukraine, invoking principles like "responsibility to protect" to frame its intervention as legitimate. By alleging systemic abuses against ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking populations, it portrays itself as defending vulnerable communities and reinterpreting sovereignty to extend its reach beyond borders (Person & McFaul, 2022; Zhekova,2023a).Thisnarrativeredefines its actions as morally justified responses toahumanitariancrisis,echoingprevious strategiesinCrimea(2014)andGeorgia (2008)

“undertheguiseof"compatriot protection"(Dutkiewicz& Smoleński,2023;Zhekova, 2023b)”.

RussiaunderminesUkraine'ssovereignty, While defending its sovereignty against Westerninterference,Russiaundermines Ukraine's sovereignty, framing it as subordinate to its regional ambitions (Zhekova,2023b).

Russia's reinterpretation of sovereignty andinternationalnormsdemonstrateshow identity and historical narratives shape foreign policy. Constructivist theory explains how norms are socially constructed and strategically used to legitimize state behavior (Wendt, 1992). Russia's actions in Ukraine illustrate the constructivistconceptthatstatesconstruct roles based on their identities, which define what they see as "just causes for action"(Wendt,1992).Byframingitselfas the protector of ethnic Russians and Russian speakers, Russia justifies intervention through its self-defined role asagreatpower.Thisconstructedidentity drives its reinterpretation of sovereignty and legitimizes its actions as part of a broader narrative to counter Western influenceandassertregionaldominance.

Russiannationalismandideological narratives have been central to justifying the invasion of Ukraine, framing it as a defense of Russian identity and sovereignty. As the war ' s ideological driver, Russian nationalism portrays Ukraineasan

IvaZivaljevic

existentialthreat,rootedinthebeliefthat its independence is an artificial construct created by external forces to undermine Russia's historical and cultural legacy (Knott,2022;Kuzio,2022).Bydismissing Ukraine's sovereignty and framing its existence as a challenge to Russian identity, Russian leadership positions its actionsasessentialtopreservingashared culturalheritage.

Discourses of colonialism, imperialism, andthe"imaginaryWest"havealsobeen employed to justify the war, resonating with broader audiences (Kordan, 2022; Knott, 2022; Tolz & Hutchings, 2023). These narratives, rooted in historical contexts predating the war, reveal the domesticallydrivenmilitanttendenciesin Russianforeignpolicy.Politicalelitesand statemediahaveadvancedthesenarratives by fabricating the threat of Nazism and framing Ukraine's Western alignment as anexistentialdangertoRussian-speaking populations (Laruelle, 2015; Zhekova, 2023a). Putin's rhetoric consistently dismisses Ukrainian statehood as a Western-backed project designed to undermine Russian influence (Vock, 2024). Through the constructs of "compatriotprotection"andthe"Russian World," the Russian government has alleged systemic abuses against ethnic RussiansandRussianspeakersinUkraine, presenting these groups as victims of discrimination and violence (Laruelle, 2015).

IvaZivaljevic

These narratives frame Russia's military actionsasanecessaryinterventiontodefend vulnerable communities, using "denazification" rhetoric claims that Ukraine's government harbored neo-Nazi elements toportraytheinvasionasamoral obligation and an extension of historical anti-fascist efforts (Tolz & Hutchings, 2023;Zhekova,2023b;Marples,2022).

defensive measure against an existential threat,

“thesenarrativesnotonly delegitimizeUkraine'snationhood butalsojustifytheerasureofits sovereigntyaspartofRussia's ideologicalmission(Marples,2022)”

Although they have limited international acceptance, they resonate strongly within Russia (Wintour, 2022). Surveys show that 89% of Russians support the government's justification for the war, demonstrating the success of nationalist rhetoric in unifying public opinion and legitimizing aggression (Kuzio,2022).Assuch,Russiannationalism and ideological narratives align with constructivist ideas, demonstrating how identityandnormsshapeforeignpolicy.By framingUkraine'ssovereigntyasillegitimate anditsalignmentwiththeWestasathreat, Russia reinforces its great-power identity, seekingtoembedandnormalizeitsactionsas a moral duty to defend its cultural and historicallegacy.

Inconclusion,thisessayhaspositedthat constructivism provides a comprehensive framework for understanding Russia's invasion of Ukraine by highlighting the role of identities and norms. Russia's great-poweridentity,rootedinhistorical and cultural narratives, drives its pursuit of dominance in the post-Soviet space, while Ukraine's shift toward the West challenges this identity and fuels perceptions of an existential threat. Russian nationalism and state-driven narratives serve as ideological drivers, framingtheinvasionasamoralobligation to protect ethnic Russians and counter Western influence, while Russia's strategic manipulation of international norms legitimizes its actions and undermines Ukraine's sovereignty. This analysis highlights the importance of identity, historical narratives, and ideational factors in shaping foreign policydecisionsandstateinteractions.

Chafetz,G.(1996).TheStruggleforaNationalIdentityinPost-SovietRussia.PoliticalScience Quarterly,111(4),661.https://doi.org/10.2307/2152089

Dutkiewicz,J,&Smoleński,J (2023) Epistemicsuperimposition:thewarinUkraineandthe povertyofexpertiseininternationalrelationstheory.JournalofInternationalRelationsand Development,26.https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-023-00314-1

Edinger,H.(2022).Offensiveideas:Structuralrealism,ClassicalRealism,andPutin’sWaron Ukraine InternationalAffairs,98(6) https://doiorg/101093/ia/iiac217

Feklyunina,V.(2016).SoftPowerandidentity:Russia,Ukraineandthe“Russianworld(s).” EuropeanJournalofInternationalRelations,22(4),773–796.

Finnemore,M.,&Sikkink,K.(1998).InternationalNormDynamicsandPoliticalChange. InternationalOrganization,52(4),887–917 https://wwwjstororg/stable/2601361

Götz,E.(2016).NeorealismandRussia’sUkrainepolicy,1991–present.ContemporaryPolitics, 22(3),301–323.https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2016.1201312

Götz,E.,&Staun,J.(2022).WhyRussiaattackedUkraine:Strategiccultureandradicalized narratives.ContemporarySecurityPolicy,43(3),482–497. https://doiorg/101080/1352326020222082633

IRI.(2023,March22).IRIUkrainePollShowsStrongConfidenceinPresidentZelensky,aSurge inSupportforNATOMembership,RussiaShouldPayforReconstruction.International RepublicanInstitute.https://www.iri.org/resources/iri-ukraine-poll-shows-strong-confidence-inpresident-zelensky-a-surge-in-support-for-nato-membership-russia-should-pay-forreconstruction/ KIIS.(2024).PerceptionofBelongingtotheUkrainianNation.Kiis.com.ua.https://kiis.com.ua/? lang=eng&cat=reports&id=1458&t=13&page=1

Knott,E.(2022).Existentialnationalism:Russia’swaragainstUkraine.NationsandNationalism, 29(1),45–52 https://doiorg/101111/nana12878

Kordan,B.(2022).Russia’swaragainstUkraine:historicalnarratives,geopolitics,andpeace. CanadianSlavonicPapers,64(2-3),1–11.https://doi.org/10.1080/00085006.2022.2107835

Kuzio,T.(2022).ImperialnationalismasthedriverbehindRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.Nations andNationalism,29(1) https://doiorg/101111/nana12875

Laruelle,M.(2015).Russiaasa“DividedNation,”fromCompatriotstoCrimea:AContribution totheDiscussiononNationalismandForeignPolicy.ProblemsofPost-Communism,62(2),88–97.

Marples,D R (2022) Russia’swargoalsinUkraine CanadianSlavonicPapers,64(2-3),207–219.https://doi.org/10.1080/00085006.2022.2107837

Mearsheimer,J.(2022,March19).JohnMearsheimeronWhytheWestIsPrincipally ResponsiblefortheUkrainianCrisis.TheEconomist.https://www.economist.com/byinvitation/2022/03/11/john-mearsheimer-on-why-the-west-is-principally-responsible-for-theukrainian-crisis

PålKolstø.(2023).UkrainiansandRussiansas“OnePeople”:AnIdeologemeanditsGenesis. Ethnopolitics,1–20.https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2023.2247664

Rich,P.B.(2013).CrisisintheCaucasus:Russia,GeorgiaandtheWest.Routledge.

Tolz,V,&Hutchings,S (2023) TruthwithaZ:disinformation,warinUkraine,andRussia’s contradictorydiscourseofimperialidentity Post-SovietAffairs,39(5),1–19

https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586x.2023.2202581

Vock,I.(2024,February9).TuckerCarlsoninterview:Fact-checkingPutin’s“nonsense”history.

Www.bbc.com.https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68255302

Wintour,P (2022,May30) NegativeviewsofRussiamainlylimitedtowesternliberal democracies,pollshows.TheGuardian.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/30/negative-views-of-russia-mainly-limited-towestern-liberal-democracies-poll-shows

Zhekova,K.(2023a,December7).RussianDiscoursesofSovereignty.Spotify. https://openspotifycom/episode/0m9k72ojysx21pY0O7MbNd? go=1&sp cid=9546232d516c1c105a419d8ff218e40a&utm source=embed player p&utm medium= desktop&nd=1&dlsi=051baef325674ecb

Zhekova,K.(2023b).TheWestinRussianDiscoursesofSovereigntyDuringthe2014Ukraine Crisis:Between“CompatriotProtection”and“Non-Interference.”Europe-AsiaStudies,75(7), 1145–1169.https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2023.2221836

FromYeltsintoPutin:TheFailureofDemocratic

The accession of Vladimir Putin to the Russian presidency marked a delicate shift from the turbulent 1990s under Boris Yeltsin, marred by political instability, economic collapse, and societal decay. Putinism as a political system, though it may not be as well defined, offers a bridge between contemporaryRussiaanditsSovietpast; whoselegitimacyisbuiltonitsabilityto overcome the failures of Yeltsin's reforms through a patronalistic trajectory. This essay will demonstrate that though the development of contemporary Russia under Putin takes influence from the Soviet system, it ultimately is neither a revival nor reconstitution of the latter, but rather built on the illiberal institutional precedents under the Yeltsin administration. Firstly, contemporary Russia presides over a vastly different webofsocio-politicalrelationsthanthe Soviet state. In particular, Russia's interconnectedness within global processes, both politically and economically, means it no longer has a monolithicpresenceoversocietybutis

BlairShang

forced to contend with political dynamism and competition. Though both exhibit authoritarian leanings, Putinism in particular reinforces the control of the state, using low-intensity repression mechanisms, to the extent thatitoffersthestateanadvantageover apluralisticsociety. Moreover, the political economy of Russiaismainlybuiltonitsextractionbased industries, underpinning a predatorystatethatsecureselitebuy-in andpreventstheemergenceofdomestic competition. Furthermore, unlike the Soviet period, there is uncertainty over the Russian identity, which the state attemptstoconsolidateanationalistand conservativecauseasanalternativepole of legitimacy to the dismal, unmaterialised economic promises. Russia on the international stage again echoesanilliberalcausethatattemptsto assertitselfglobally, “butmorespecifically championingitselfagainstthe West.”

absenceofpoliticalmanifestosortheoretical foundations, which instead are characterized by personalistic and pragmaticgovernancethatreliesheavilyon patronage and populism (Fish, 61-2). However,when characterising contemporary Russian institutions, Putinism cannot be credited forcreatingtheRussianstateofnow,which isinheritedfromtheYeltsinadministration following the early period of liberalisation and the failure of democratic transformation. The lack of democratic progresscanbetracedtotheinitialperiod of decommunization, and the failure to facilitatepoliticalturnoverfromtheSoviet Nomenklatura, the former Soviet bureaucratic class, and reconstituting the surviving institutions following independence. The absence of meaningful political transition under Yeltsin not only meantdemocraticbacksliding,butalsoelite entrenchment through the economic liberalisation and privatisation (Snegovaya, 105-7). The formal induction process into bureaucracy has devolved into a patronalistic system that revolves around connections,whichsimultaneouslyalienates the existing, and furtherly stunts the development of, a democracy-friendly governing class (Snegovaya 110-11). Moreover, the emergence of the 'siloviki,' individuals with security and intelligence backgrounds, and often with ties to the underworld,beganaprocessofstatecapture as the main benefactors to economic liberalisation.

Yet the process of political decay, however,wouldultimatelybeinitiatedby Yeltsin, who first suspended the voting procedure to appoint regional administrators after being frustrated with the lack of political turnover resultantly centralising control around Moscow,andinsteadfilledthepositions with personal affiliates (Snegovaya, 111). Furthermore, Yeltsin's decision in 1993 tobesiegehispoliticaloppositioninthe Russian parliament led by the Vice President Aleksandr Rutskoi using militaryforce,hasfurtherlyundermined democratic values in its early founding period, thereby strengthening the Russian executive and setting illiberal precedencesforautocratisation(Laporte, ed.Wengle,37).Asaresult,Russian intothepresidency;whichPutinismcan be seen as the extension of existing democratic flaws that allowed for the entrenchmentofasuperpresidency not tomentionpopulardisappointmentover liberalreforms.

“democracyhadessentiallybeen hollowedoutlongbeforethe accessionofPutin”

AkeycomponentofthePutiniststateis where it attempts to influence political processesandsocietyinsteadofextending centralised control altogether. Though contemporary Russia is characterised as authoritarian, the Russian state has purposefully maintained a legalistic approach towards politics, under a veil of democracy as inscribed under the constitution. The electoral system, no matter how flawed, remains to be a ritualistically legitimating tool of Putin's political control, affirming the political reality through both formal and informal pressures at guiding the electoral process (ReuterandSzakonyi,ed.Wengle,76-9).

Firstly,thebenefitsofholdingelectionsis thatitrevealspopulargrievances,fostering authoritarian accountability, and the possibility to co-opt opposition by resolving the same grievances, or encouraging resistance through legal means whichremainstobefavourableto theregime(ReuterandSzakonyi,78).Also differing from the hard, open political repressionoftheSovietperiod, whichisbothcoerciveandlegitimatetoa degree. For example, poll stations are manned by public servants, and usually teachers,whofaceanincentivetodeliver

electionresultsfavourabletotheregime; than if not, could possibly lead to being relieved from official positions, whereby deliveringtheinformalexpectationforms apathofleastresistance.

“theelectoralsystemcanbe seenasalow-intensity repressivemechanism,”

Theincentivetovotefortheincumbentat the threat of punishment has contrarily formed an informal dilemma that engineerselectoralvictoryfortheregime, which has not openly threatened force otherwise. The self reinforcing legalistlegitimate process is reflective of the political consolidation process, in which Putin has gradually reshaped politics and society using the pre-existing framework and working within the system, than to impose his own altogether. The PutinMedvedev tandem is the pinnacle of this political farce, using an existing legal loopholeonpresidentialtermstomaintain power.Thetandemfollowstheconclusion ofPutin'ssecondterm(2004-2008),when he contends himself to the role of Prime Minister under the presidency of his political ally Dmitry Medvedev, but then runs again as president at the end of Medvedev's term, leading to popular outrage (Laporte, ed. Wengle, 50). Putinismcanthereforebeinstead

interpretedastheconsolidationofpolitical controlbyPutin,formallyandinformally, over the Russian state and society, reflecting the process of subversion state capture, which instead affirms Russian democraticinstitutions.

Putinismcanthereforereflectanevolution of the state built on the nation-building progressunderYeltsin,towardstheendsof political consolidation, that can be differentiated into phases with varying policy priorities. The initial consolidation of Putinism revolved around the reassertion of state control, particularly overthemedia,whichdemocraticreforms resultantly produced a weak state vulnerable to external influence. The role of the media has historically been politically significant, that propaganda formedoneofthemainpillarsofpolitical control under the Communist Party, extending into contemporary Russia (Gehlbach, Lokot, Shirikov, ed. Wengle, 392).

“Independentmediahadcome underthecontrolofemerging oligarchs”

ThepracticeofCherniyPiar,theSoviet tactic of defamation at undermining political dissidents, is similarly used in the post-Soviet context, albeit commercialised against political and market competition (Gehlbach, et al, 393).

Mediahasbeeninstrumentaltopolitical success in the immediate post-Soviet period, which it had secured Yeltsin's second term in 1996 at the expense of economic concessions to the oligarchs; and similarly thwarted the political campaignoftheformerPrimeMinister YevgenyPrimakovin1999through maliciousreporting(ibid).Theoligarchs had established themselves as an independent political base, where political influence and control over the mediawereself-reinforcing.

after the initial economic liberalisation period as it became commercialised, represented most prominently by Boris Berezovsky (Obshchestvennoye Rossiyskoye Televideniye, ORT) and Vladimir Gusinsky (NTV) (Gehlbach, et al,393).

The political consolidation of Putin came at the direct expense of the oligarchs,whichhadposedanexistential threattoPutin'sfirstterm addingthe opportunity to instill political loyalty amongtheelites(Gehlbachetal.,394). However,itwouldalsoproveimpossible to impose monolithic control over information; even after the state reestablished control over oligarch media corporations,itcouldnotpreventsmallscale and foreign media from proliferating.

Access to the internet had also establishedadifferentdimensionof

information,inwhichthestate couldnotgainamonopolyoutsideoflegal restrictions and limitations, albeit state censorship would only grow to become moresophisticatedovertime(ibid,404).

Alternatively, the state similarly practices disinformation campaigns, which do not necessarilyenforceanarrativebutweaken opposition messages enough to discredit them. Though state repression and censorshipharksbacktotheSoviettimes, it would not be as comprehensive as the Soviet system, limited to the political consolidation against competition. The Russian state has grown qualitatively differentfromtheSovietsystem,thoughit manifests similar authoritarian and repressivecharacteristics,hasfardeviated in terms of political culture—which insteadreflectsatrajectoryofstatecapture oneconomicgrounds.

Political repression does not solely maintain the regime's control over the Russianstate,butalsoeconomiccontrol wherein Russia primarily relies on extraction-basedindustrieslikeoilandgas. There-establishmentofstatecontrolover the energy sector had bolstered Putin's regime by incentivising and rewarding political loyalty; thereby improving the state economics, allowing reform to the welfare state and controlling domestic politicsbyremunerativemeans;andlastly re-established strategic independence, which allows for an aggressive foreign policy.

Though economics is the largest differentialfactorbetweentheRussianand Soviet system, contrasting a stateinfluenced market capitalism to a state planned economy respectively; both are similarly a petrostate through their economic overreliance on energy exports (Strokan,Sil,ed.Wengle,248-52).

Since the failures of democratic reforms had fostered the oligarchic class as an independentpoliticalbase,theaccessionof Putin and aforementioned repression of the media had also extended into the economic sector where both sides failed to accommodate a compromise, keeping theoligarchsoutofpolitics.Forexample, the affair of Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Yukosoilin2003resultedinthearrestof theformerandthebreakupofthelatter, under tax evasion and embezzlement charges(Strokan,Sil,ed.Wengle,257-8). Thecrackdownwasnotonlyeconomicin nature, to mention Khodorkovsky's political ambitions, but also signalled a reassertion of state control over the strategic energy sector that privatisation had temporarily relinquished from the state driven by popular disappointment, facilitatingeconomicrollbackandcreating state-corporations(ibid).Butthisdoesnot meantheformalre-establishmentof

controlovertheenergysector,since patronage has already become deeply entrenchedintothesystembytheprocess of state capture. In particular, with BerezovskyandGusinskyontheonehand, Khodorkovsky on the other, state seizure of assets meant dividing the spoils to politicallyreliableelitesinstead,byRoman Abramovich and Gazprom respectively (Gehlbach,etal,393-4).

Russia under Putinism can therefore be called 'piranha capitalism,' reflecting the development of state extraction and patronalisticnaturethatreachesapointof contradiction, which struggles to simultaneouslyensurepoliticalloyaltyand economic security. The state requires significant private investment to fund its own expenditure on social security and defence, which in turn consolidates its legitimacy and control, but itself is nonconducive to investment since it fails to securepropertyrights.Theprocessofstate extractionisfoundedontheemergenceof amentovskaiakrysha(police-racketeering) post-1990s, where law enforcement replaced violent entrepreneurs to extract private wealth, using the law through means such as contract investigation and business raiding (Gans-Morse, ed. Wengle, 212).The crackdown against Yukos,asmentionedpreviously,demarksa turning point in Russian institutions, furthered by the abolishment of the Supreme Commercial Court, undermining Putin's earlier legal reform underhisfirstterm,

which moved away from Soviet law to secure property rights (Gans-Morse, ed. Wengle, 210; 217). Even though strengtheningthestatehas,asaresult, centralized violence around itself, the growthofracketeeringandmaximizing short-term benefits of extracting privatewealthcanbeseenasalegacyof the 1990s, that co-opting private predationhas,inresult,diminishedthe legitimacyoftheRussianstate.

“Theissuesofsocialwelfare andinequalityhadpreviously beenthefoundationofPutin’s politicalpower,”

rising to the presidency on the agenda andpromiseforeconomicstabilityand recovery. Contrasted to the economic reformsandsubsequentcollapseofthe 1990s,Putinhasmanagedtoimplement bare improvements of the welfare system

to offer a basic social welfare regime, limited to the state capacity and persistently poor economic situation (Strokan,Sil,ed.Wengle,313-4).

The general dismal state of welfare and inequalitycanbeperceivedasaresultof the overreliance on the energy industry, whichisa'resourcecurse,'wherebystate accountability corresponds to the degree of economic reliance on taxation, which the Russian state forgoes any need to improve the social and economic conditionsbeyondnecessity(Strokan,Sil, ed.Wengle248-9).

Putin's entrenchment into the political establishment had correspondingly degraded political accountability and improvements,prioritisingstatepredation instead as a means to maintain political loyalty. Unlike the Soviet petrostate whereresourceexportprofitsaredirected towardsdevelopingadiversifiedeconomy, thereislittleincentivefortheRussian market economy to move beyond an extraction-based economy, let alone investingintofurthersocietalobligations (ibid). In particular, development of a petroeconomyisattractivetothecoercive and corruptive nature of the Putinism system, since directing investment into one sector allows general embezzlement without undermining the system (Fish, 63). As opposed to developing the economyasawhole,apetroeconomyalso prevents the emergence of autonomous politicalactors,whichaboveall,allowsfor Putintorewardthoseclosesttothesystem (ibid)

In particular, development of a petroeconomy is attractive to the coercive and corruptive nature of the Putinism system,sincedirectinginvestmentintoone sector allows general embezzlement withoutunderminingthesystem(Fish,63). Asopposedtodevelopingtheeconomyasa whole, a petroeconomy also prevents the emergence of autonomous political actors, whichaboveall,allowsforPutintoreward those closest to the system (ibid). Adminresursyisessentialforunderpinning Putinism,demarkingtheallocationofstate resources on the basis of directing investmentintoaparticularsector,whereby expecting part of the funding to be embezzled, in turn awarding political loyalty using state resources. Putinism has essentiallycreatedapersonalisticautocracy over the Russian state, as opposed to the Sovietsystemthatcentralisedpoweraround theParty(Fish,69).Thedevelopmentofan

extractivesystemthroughbothformaland informal means has essentially created an entrenchedelitewhichdoeslittleforsocial welfare and economic development, that resultantly undermines the states popular legitimacy for political loyalty, which alternatively forces a redirection of discontentandrhetoric

The current Russo-Ukrainian war can thereforereflecttheconcurrentattemptsof Putinism at seeking alternative poles of legitimacy, consolidating populist support by championing conservatism and nationalism Putin's revisionist and aggressive approach to foreign politics can be firstly identified by Putin's historical accession after Yeltsin's resignation, which hasbeenlargelyinfluencedbyhissuccessful handling of the Second Chechen War (Aktürk, ed. Wengle, 496-7). The rallyaround-the-flag effect is similarly invoked aftertheannexationofCrimeain2014,that revitalisedPutin'sdecliningpopularitysince 2012,aftertheheavy-handedrepressionof the Bolotnaya protests in response to the Putin-Medvedev tandem (Fish, 65-66). Popular reception to the reassertion of Russia's greatpowerness internationally, or intothepost-Sovietspaceinparticular,can be perceived as a cultural schemata and legacyoftheSovietcollapse

“ThecontemporaryRussianidentity, orthelackthereof,isthedefining factorfortheexpansionisttendencies ofcontemporaryRussia.”

Putinism tries to push forward its own interpretation of the Russian identity, namelyaRossiyskayanarod,atcreating a civic Russian nation composed of mnogonatsional'nyi narod (literally: multi-national people), the Soviet concept of peoples—where the contradictionisreflectiveofthehistoric absence of Russia in the legal sense (Tolz,1005).

Theambiguityofidentitycantherefore beinterpretedinthephysicalsense,that it does not delineate a de jure Russian border Therefore, remnant RussianspeakingpopulationsfromtheImperial and Soviet periods beyond Russia's international borders are used as justificationforforeigninterventionby Putin.Furthermore,Putinismpeddlesa defensive rhetoric against the West, which is portrayed to be hostile, in a scapegoat sense at deflecting internal issues. Russian historical narratives are theforefrontofbothanti-Westrhetoric and Russian identity dilemma, since memory wars over Russia's Soviet legacy and World War II has firstly, invoked complex memories within EasternEuropeoveritsSovietpast;

“itestablishesawarcultinRussia thatpanderstowardsnationalist fringes(Koposov,210-15).”

But moreover Russian foreign policy has particularly followed the Soviet rhetoric, championingitselfasanalternativepolitical order to Western liberal democracy, such that progressive policies are portrayed as decadenceintheconservativesense,receptive tothemajorityofthepopulation(Fish65-6). Whereas re-establishing Russian foreign influence particularly in Africa, anticolonialismremainsthedomineeringrhetoric inherited as a Soviet legacy (Duursma and Masuhr,409-10).ThoughRussiacapitalises on its Soviet legacies for the historical justificationsandgrievancestoreassertitself internationally, it has largely done so in the context that domestically the economic and politicalconditionsunderminetheregime's legitimacy. Foreign aggression instead strengthens another pillar of domestic support through nationalism and conservatism, that furtherly enhances the accountability of the regime. Though Putin had subverted the Russian state for its own doctrine of Putinism, it subsequently gave the state a life of its own, where the Soviet system can neither impose nor influence. Putinismremainsasystemthatisembedded within the context of the failures of liberal reformofthe1990s,reflectiveofPutin'sown personalisticdriveforpoliticalcontrol.

The system is largely an extension of the democratic flaws of the Yeltsin administration, using the petroeconomyasameansforpolitical loyalty. Yet populism would again be invoked in the expansion of conflicts within the post-Soviet space, where promises of domestic change fail to swaysupporters,thatinturnrelieson nationalismtojustifyitslegitimacy.

Fish,M Steven "WhatIsPutinism?"JournalofDemocracy28(2017):61

Snegovaya,Maria."WhyRussia’sDemocracyNeverBegan."JournalofDemocracy34, no.3(2023):105-118.

Jody LaPorte, “Russia’s superpresidency,” in Russian Politics Today (ed., Susanne Wengle).

ScottGehlbach,TetyanaLokot,andAntonShirikov,“TheRussianmedia,”inRussian PoliticsToday(ed.,SusanneWengle)

Mikhail Strokan and Rudra Sil, “Russia's oil and gas industry: Soviet inheritance and post-Sovietevolution,”inRussianPoliticsToday(ed.,SusanneWengle)

Gans-Morse,Jordan,“Propertyrights:forgingtheinstitutionalfoundationsforRussia's marketeconomy,”inRussianPoliticsToday(ed.,SusanneWengle)

ŞenerAktürk,“EthnicityandreligioninRussia,”inRussianPoliticsToday(ed.,Susanne Wengle)

StephenKotkinandMarkR Beissinger,“TheHistoricalLegaciesofCommunism:An EmpiricalAgenda,”inKotkinandBeissinger,eds,HistoricalLegaciesofCommunism inRussiaandEasternEurope.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2015.

Tolz, Vera. “Forging the Nation: National Identity and Nation Building in Post‐communistRussia.”Europe-AsiaStudies50,no.6(September1,1998):993–1022.

NikolayKoposov(2022)“TheOnlyPossibleIdeology”:NationalizingHistoryinPutin’s Russia,JournalofGenocideResearch,24:2,205-215.

AllardDuursma&NiklasMasuhr(2022)Russia’sreturntoAfricainahistoricaland globalcontext:Anti-imperialism,patronage,andopportunism,SouthAfricanJournalof InternationalAffairs,29:4,407-423.

Reuter,O.J.andSzakonyi,D.(2022)“PartyPoliticsandVotinginRussia,”inRussian PoliticsToday(ed.,SusanneWengle).

This year ’ s debut publication of the Akhmatova Review is an insightful and diversecollectionofart,poetry,personal narrative, and political discussion across the Baltic region, Central and Eastern Europe,andEurasia.Takingontherole as Managing Editor has given me the opportunity to connect with the experiences and insights of undergraduate scholars from around the world and reflect on my own ancestral rootsinCzechiaandCroatia.

A key value of our publication is the abilitytobringattentiontoregionsthat are sometimes overlooked in the discussionofSlavicandEurasianstudies such as Turkey, Latvia, and Mongolia and including a place for them in the journal.Iamthankfultoandproudofall the writers whose work comprises the heartandsoulofthispublication,andthe incredible team of people who helped bring it to life. This journal was made possible by our photographer who captured stunning architectural scenes across Central Europe, our dedicated Co-Lead Editors, Copyeditors, and EditorinChief,whoworkedhardallyear toputtogetherthisyear’spublication.

Iwanttoexpressmysolidaritywiththose across Eurasia who refuse to submit to oppression, such as the demonstrators fighting against systemic corruption and threats to democracy in the streets of Istanbul,Tbilisi,Bratislava,andBelgrade, tonameafew.AsAnnaAkhmatovaherself understood,thepenisapowerfultoolfor culturalpreservationandrebellionagainst oppressive systems, and I hope to honor herlegacybycontinuingtoopenaforum for rising writers, poets, artists, and activists to have their voices heard and helpcultivateavisionforthejournal.

Sincerely,

AlexaFrcek ManagingEditor