Repositioning the local: Mapping Stories as Place-making tools at the Kumbh Mela

MA ARCHITECTURE AND HISTORIC URBAN ENVIRONMENTS

BARTLETT SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, UCL

DATE : 7TH SEPTEMBER, 2023

The research would not have been possible without the support and assistance of several individuals who have given their time and patience towards its completion.

I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Lakshmi Priya Rajendran for being the catalyst of this research. Her advice, ideas, moral support and constant guidance led the project up to its final stage. Working with her on this dissertation was a great learning opportunity and the lessons of which I will carry into my future professional endeavours.

I would take this opportunity to thank all the tutors at Bartlett MAHUE. Edward Dennison for all his kind words of encouragement and support throughout the year.

Maxwell Mutanda, Jane Wong and Barbara Campbell for their valuable guidance and compassion.

Jhono Bennett for his useful advice and suggestions during the course of the dissertation.

It has been my privilege to be a part of UCL and Bartlett which provided me with a platform to further my pursuit of an inclusive and equitable built environment.

I would like to thank Ottilie, Eden, Jada, Girish, Wallace, Anil, Kharisma and Deepika for enthusiastically participating in the workshop conducted during the course of this research. I am also grateful to my MAHUE friends who have played an integral role in my learning journey. My friend Kharisma has been my constant. She has been motivating and persuasive during the course of this research and beyond.

Lastly, I would like to thank my family for believing in my abilities without which I could not have undertaken this journey to London and at Bartlett.

ABSTRACT

Cities are the cradle of civilization, culture and innovation. Whether oral, written or illustrated, narratives can shape the identity of a place. The act of storytelling as a place-making tool is used to develop various socio-spatial practices at the Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj. Widely known as the ‘tent city’, the research conceptualises these spaces as ‘urban rooms’ that facilitate religious and leisure activities. However, the representation of urban environments has been limited to the Western cartographic traditions of accuracy, scale and frame. The drawings do not convey more than the visible reality due to the application of uniform mapping techniques. By questioning the role of colonial mapping practices in depicting the local sensibilities of the Kumbh Mela, this research aims to move beyond the standard orthogonal representation method and focus on the transformative and narrative function of drawings and other visual media.

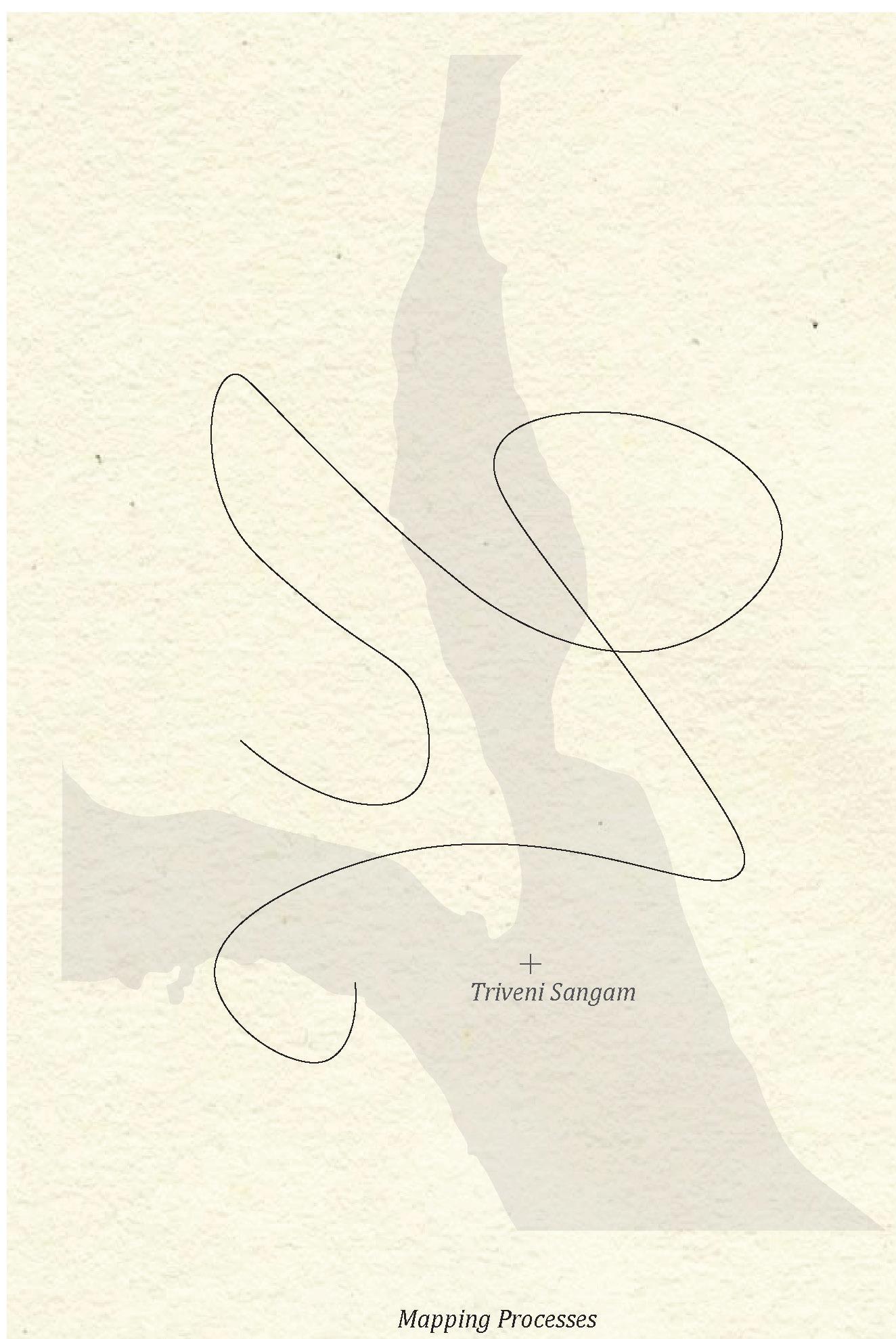

The dissertation uses counter-mapping methods to reposition the festival beyond its portrayal of a ‘temporal city’ to a potential ‘third space’ within the urban realm. The spatial typologies of the festival are rooted in geographical and context-based practices. Recognising the complexity and diversity of the temporal city through mapping, the research develops a methodological approach towards mapping as a situated practice. The workshop conducted for this research resulted in creating ‘visual think-pieces’ to reflect on the multi-layered nature of the festival and decode issues around the agency to represent local spaces. The research produces ‘sensescapes not landscapes’ to map the experience of the Kumbh Mela. It compiles the material and affective qualities of the festival and creates alternate knowledge systems to uncover future possibilities for the site. The research will assist in rethinking the process of mapping across various visual media and will build on the existing position of mapping as a continuous process and an open-ended project.

The Kumbh City - A Temporal Intervention Source : Gupta,Jiva. n.d as cited by Mehrotra, 2015

The Kumbh City - A Temporal Intervention Source : Gupta,Jiva. n.d as cited by Mehrotra, 2015

PREFACE GLOSSARY

The dissertation is a series of short chapters focused on the spatial representation of the Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj. It aims to challenge the prevailing imagery of the festival by substantiating it with suitable arguments. The first part of the thesis lays the foundation for the project and introduces the principal themes of the study. The second part will introduce the site with its brief history, and its popular discourse. The third part focuses on the methodology used to corroborate the arguments and the final part will conclude with the construction of a tent as a prototype and production of images, thereby addressing the socio-spatial relationships and urban practices embedded in the festival.

India is a land of diverse cultures and geographies. One of the distinct characteristics of the people is their ability to discuss, debate and form opinions. The public conversations are held in liminal spaces within the urban realm. These places provide an opportunity for negotiation with the members of the community. My visit to Prayagraj made me realise the ‘argumentative’ idiosyncrasies of the locale. Politically charged university campuses or discussions around a public square or a tea stall, the local people enjoyed having conversations on subjects from art and literature to politics. Prayagraj is a significant city in the Indian context. It has a rich and diverse history comprising the ancient, medieval and colonial periods. The city is a microcosm of culture and is a melting pot of different religious denominations. One such religious gathering is the Kumbh Mela. Extensive research which I will elaborate on in Part 1, led me to view the festival of Kumbh not just for its temporality but also as a ‘third space’ it created within the public realm. The dissertation does not delve into the romanticisation of the temporal nature of the ‘tent city.’ The festival has its government and planning bodies dedicated to its functioning and acts as a ‘place-driver’ to attract millions of people to Prayagraj. The congregation at the Kumbh Mela has been the subject of many global documentaries and research papers.

The South Asia Institute at Harvard University conducted extensive research on the Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj documenting various aspects and processes in structuring the event. However, this study takes a different approach compared to the existing position of researchers. The following research focuses on de-layering spatial practices and de-coding existing meanings of space using counter-mapping as a tool. The study will mostly be useful for scholars and practitioners in creative industries and urban studies, though the language of the research is simple and easy to understand for all types of readers.

7 September 2023

Akhara - a religious sect of sadhus with its own set of beliefs and traditions

Akshayavata tree – Indian Fig tree / Banyan tree

Dana – charity

Epics – Indian literature (Ramayana and Mahabharata)

Homa – fire oblation

Kalpavasi – a pilgrim who stays for a complete month at the Kumbh Mela

Kathavachak – narrator

Langar – communal eating ceremony

Mela – fair, festival or a spectacle

Naga sadhu – militant ascetic (living a secluded life and only appear in public during the Kumbh Mela)

Prayaga – the sacred zone at the confluence of the rivers

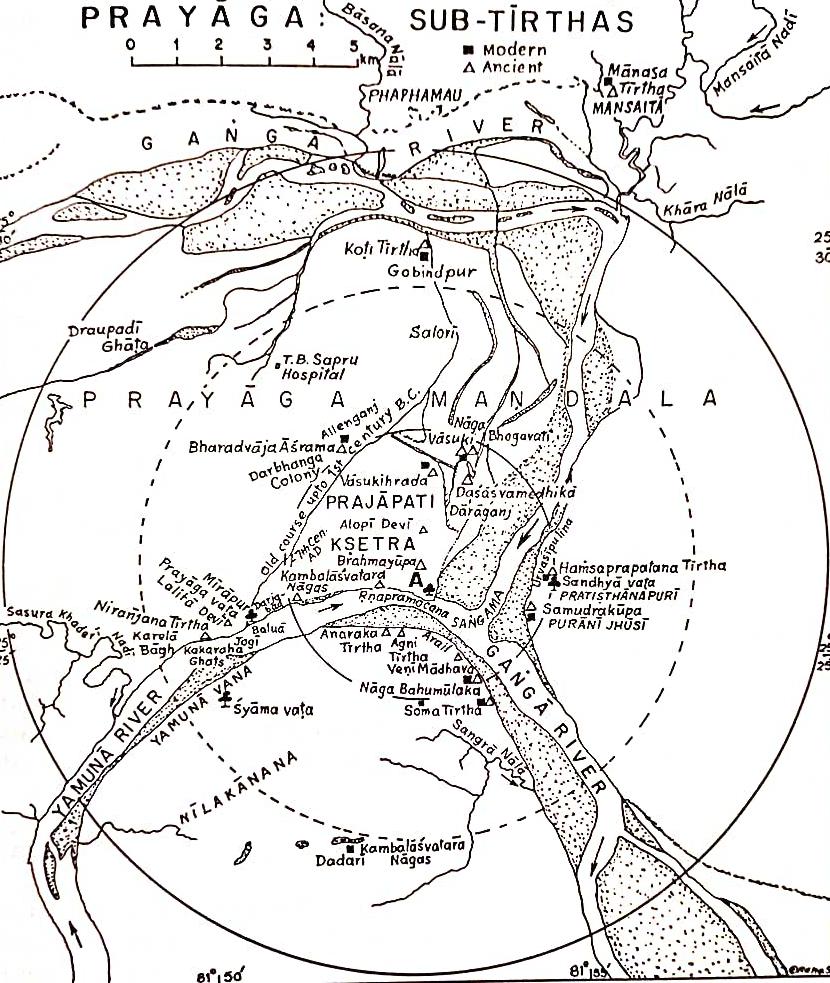

Prayaga mandala – cosmological map of Prayaga; mandala means circle and centre

Puja – worship of deities

Puranas – a religious text from the Later Vedic Period containing traditional folklore besides other subjects like geography, cosmology and Hindu philosophy

Sadhus – monks, ascetics

Snana – bathing

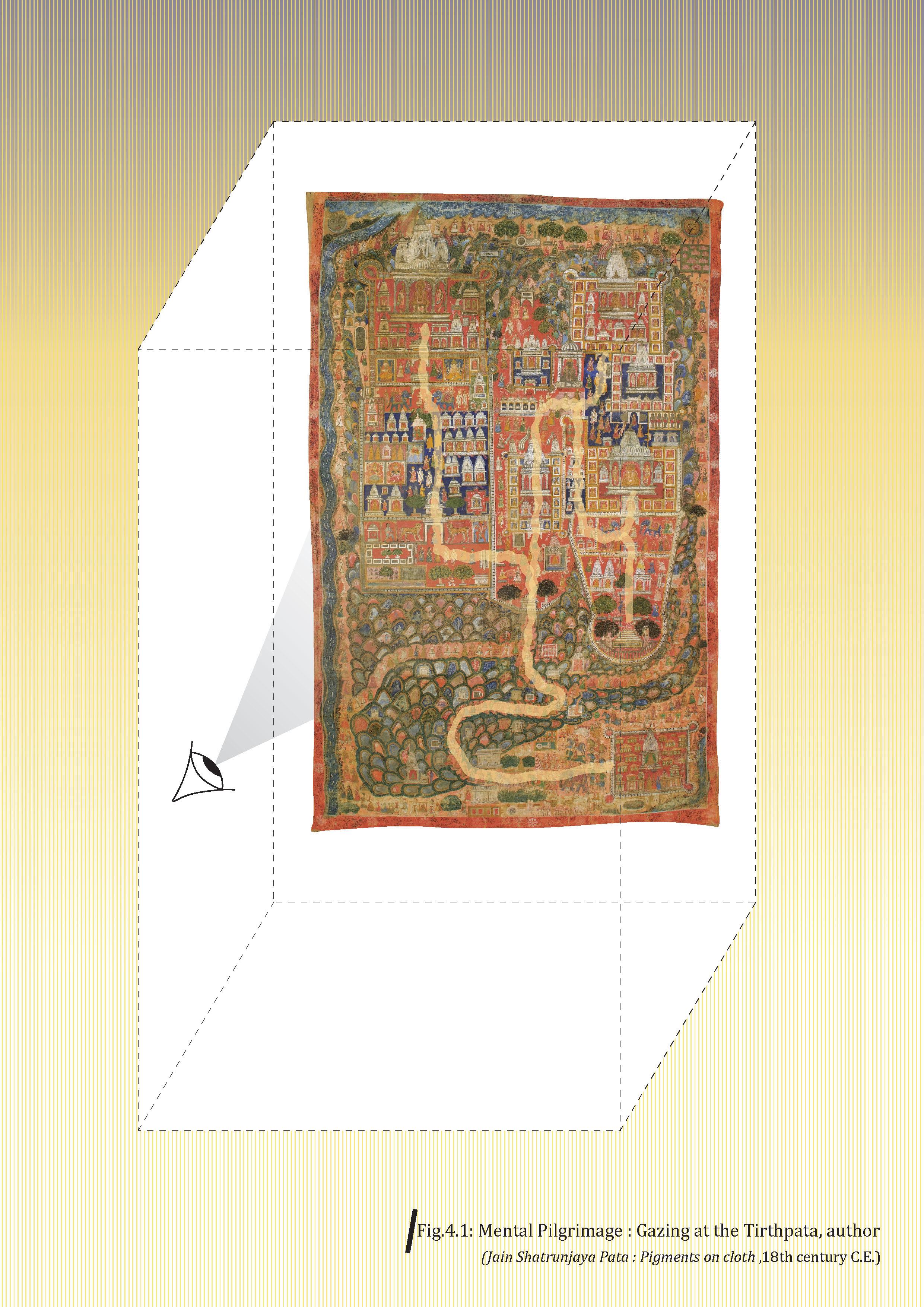

Tirthpatas – a Jain pilgrimage map

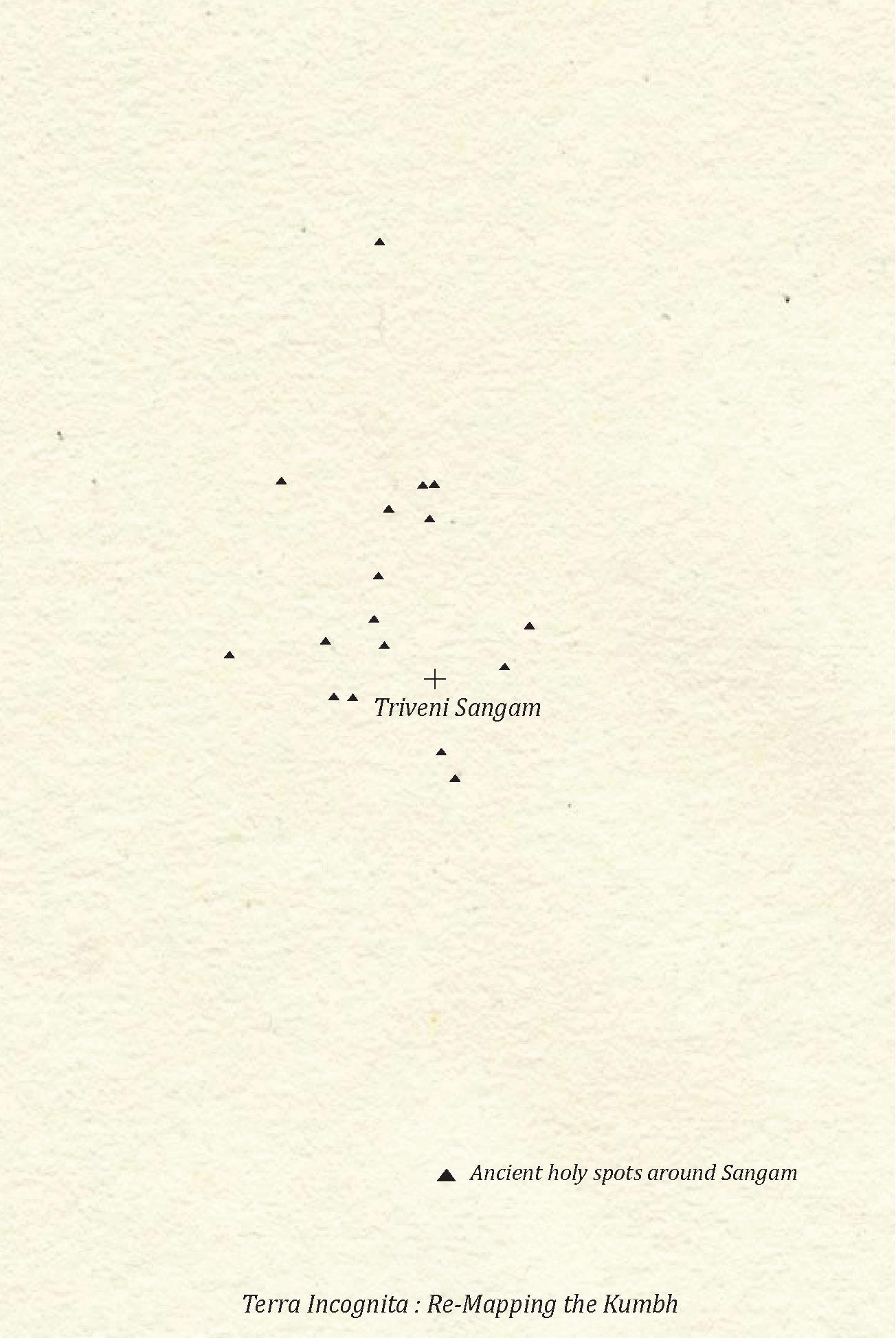

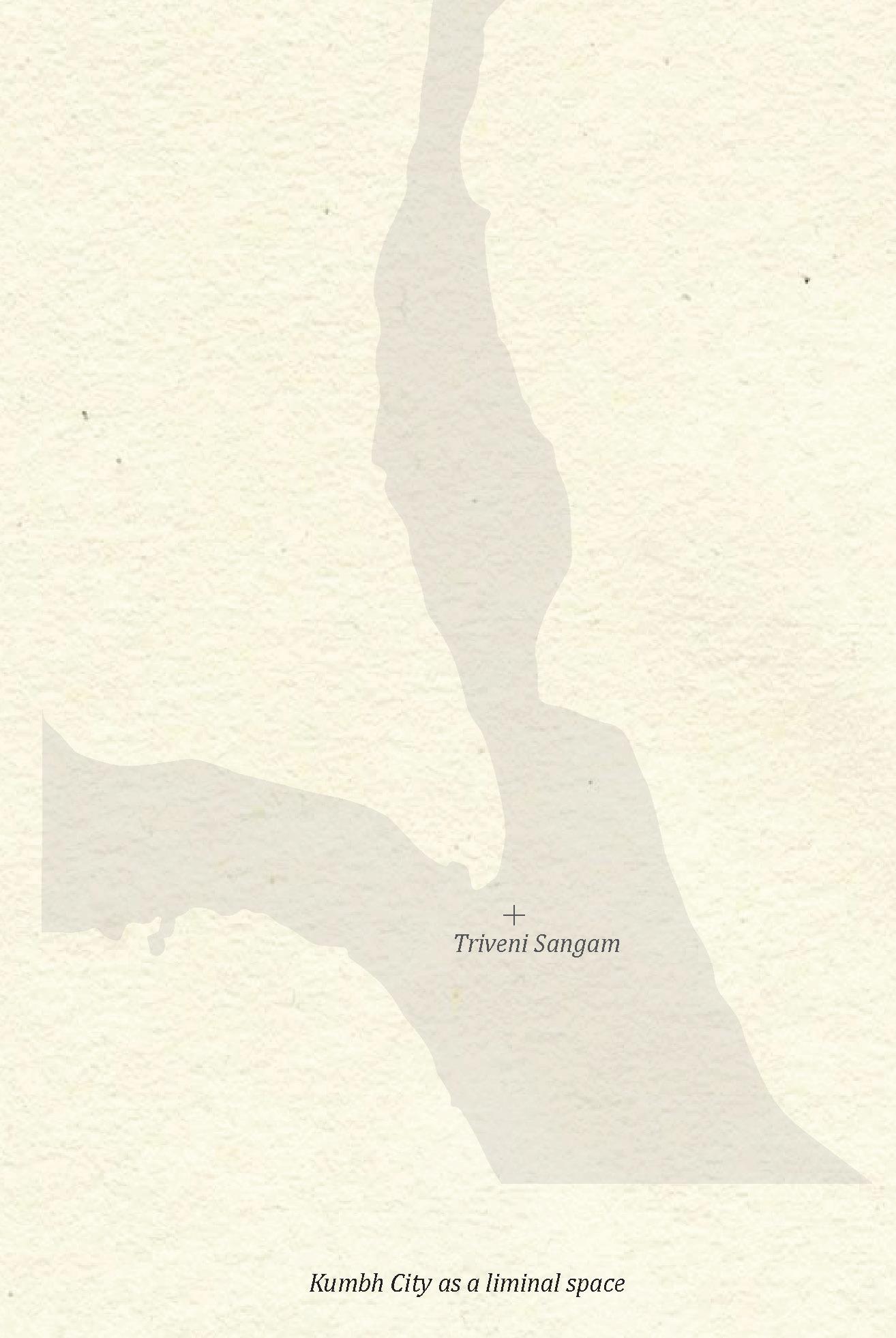

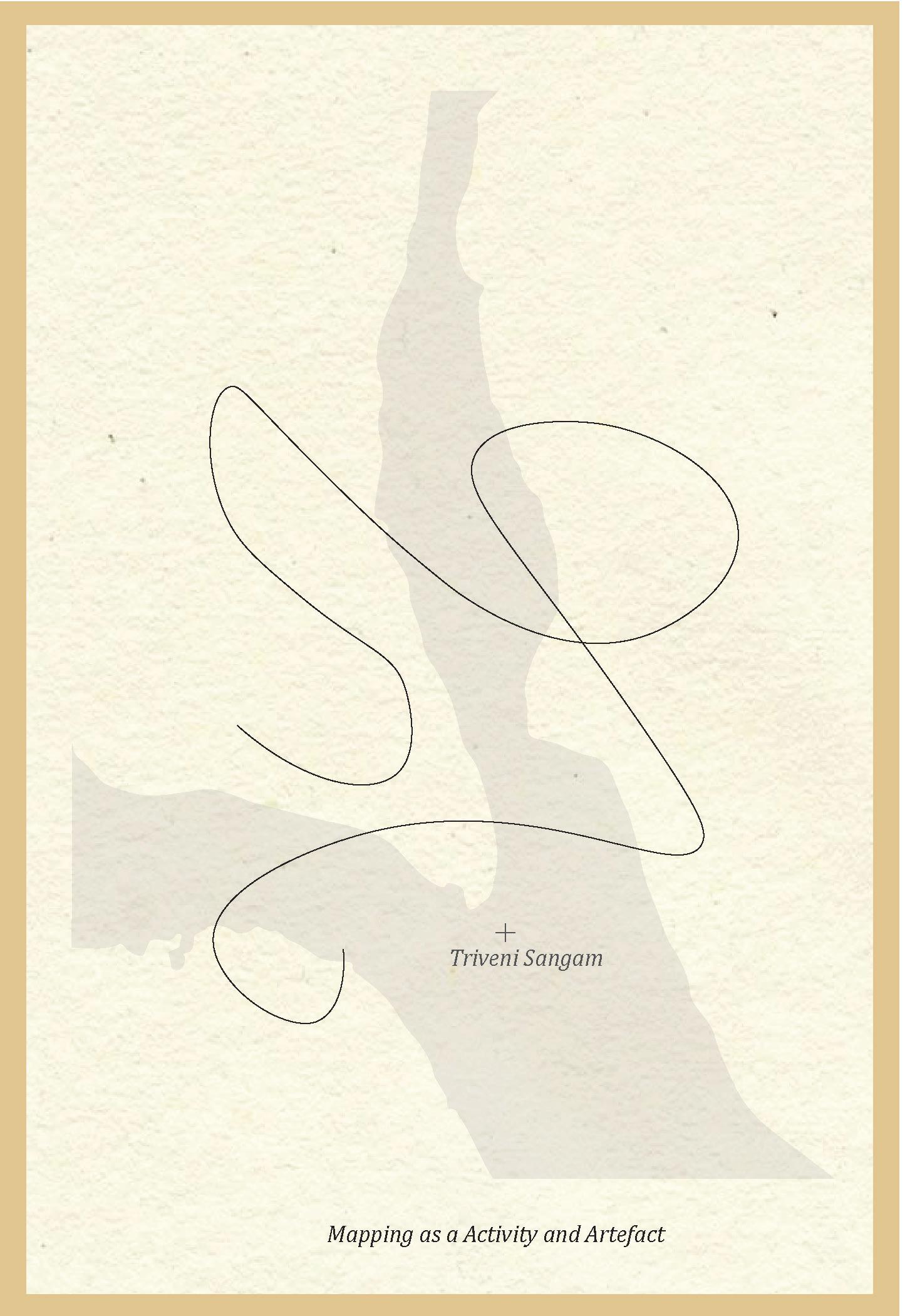

Triveni Sangam- meeting point or confluence of the rivers Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati (physically missing) in the city of Prayagraj

Upavasa – fasting

Vedas – the oldest religious text in India with a collection of hymns in Sanskrit for performing various rituals. There are four Vedas / religious books: Rig

Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda, Atharva Veda

Rig Veda – oldest of the four Vedas

Vrata – vows

PART 1 : INTENT

1: Context

The chapter is an introduction to the thesis. It gives a brief overview of the Kumbh Mela and its global positioning to give the reader a glimpse into the nature of the festival. The chapter also outlines the research question, aims and objectives of the paper and gives a summary of the remaining sections of the research.

The ancient city of Prayagraj1 lies at the confluence of the three sacred rivers: Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati, with the last one physically missing2. This meeting point is known as Triveni Sangam. Hindus believe bathing in the ‘holy waters’ will wash away their past sins and release them from the cycle of re-birth. Hence, every twelve years religious rites are performed by bathing in the rivers in a festival known as the Maha Kumbh Mela. The festival rotates every three years among four different river-bank cities which are Prayagraj, Haridwar, Nashik and Ujjain3.

The Kumbh Mela is a congregation of people, saints and ascetics following different sects within the Hindu fold. The festival was recognised by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage in 20174.

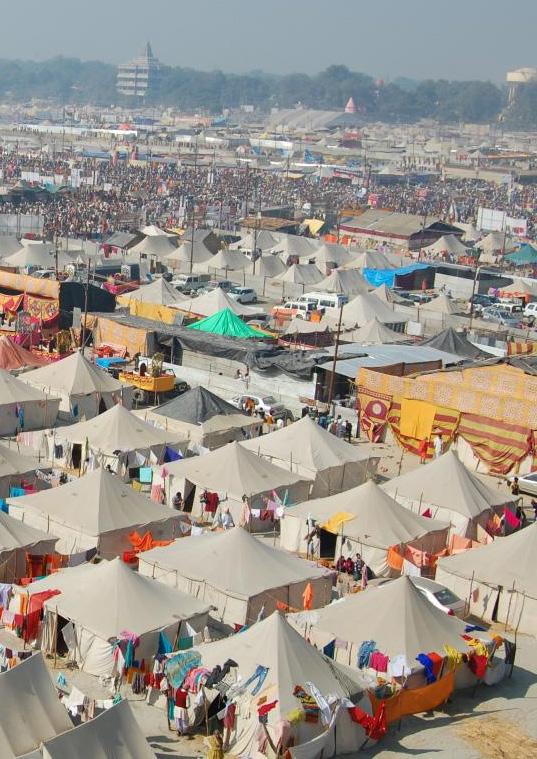

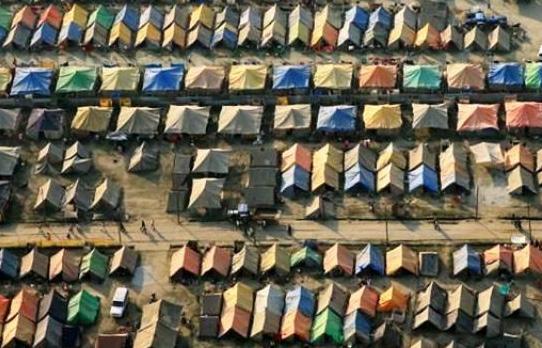

According to media reports, approximately 200 million people visited the 2019 Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj. Often labelled as the ‘world’s largest human gathering,’ (Malhotra, 2019; Pandey, 2019; Taylor, 2013) the festival attracts global media and scholars from various research faculties. A temporary city is built for this megagathering (See, Fig.1.1). The Kumbh Mela lasts for 55 days, (approximately two months) during which religious sermons and discussions on many past and present issues take place. Theatrical plays on mythological and religious themes are also organised in several larger tents.

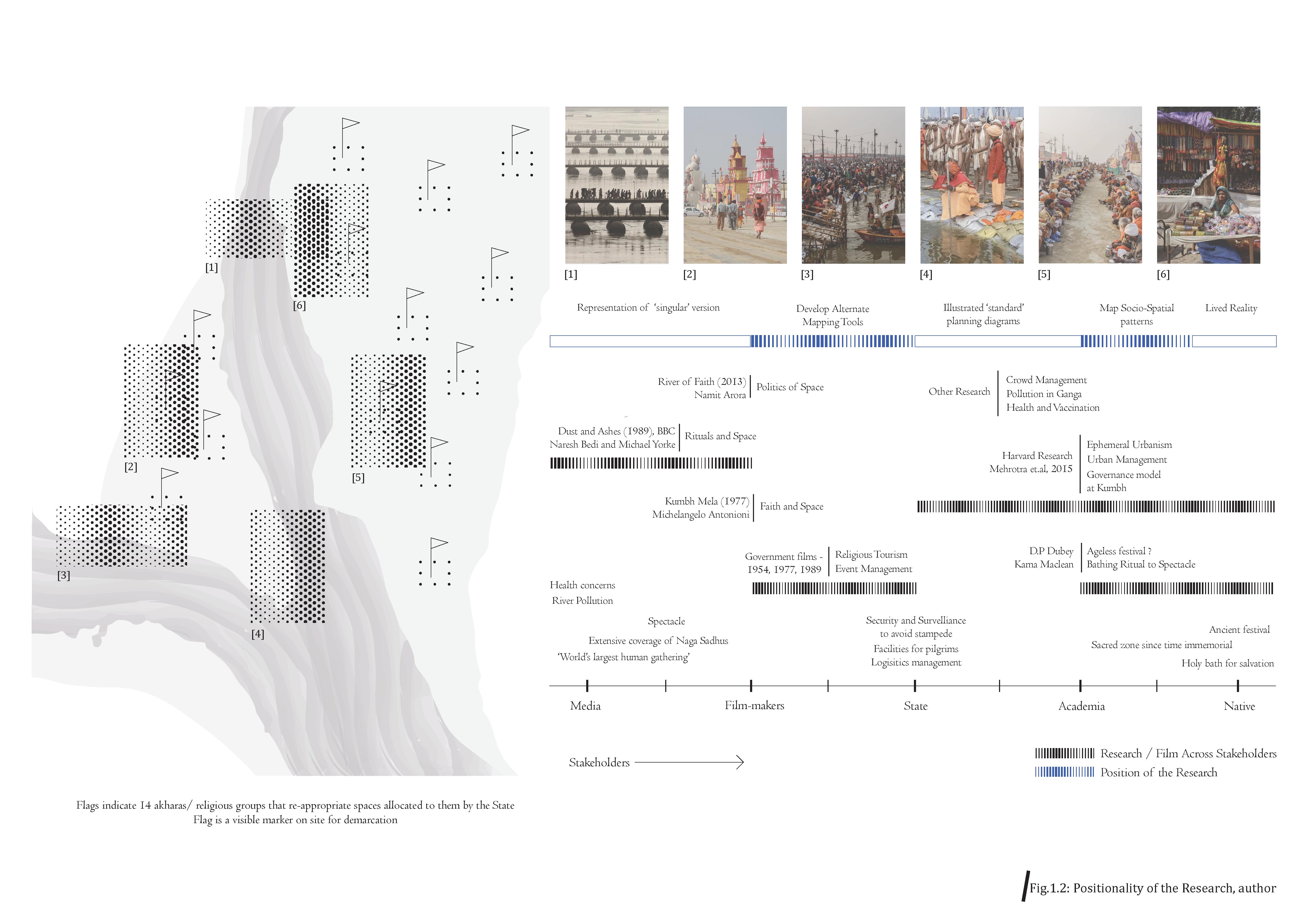

Various researchers and filmmakers have made the Kumbh Mela a subject of their study. The festival is supported by powerful imagery that is used to produce narratives for the city and have shaped its cultural identity. While the State uses the festival as a platform for national integration and religious tourism, the local and international media are largely captivated by the sheer number of pilgrims and ascetics assembling in one place. Hence, captured images are primarily for consumption purposes. Recent research (Mehrotra et al., 2015) on the Kumbh Mela focused on the crowd management systems, health infrastructure,

governance model, temporal urbanism and environment. The following study aims to draw attention to the sociospatial nature of the tents built for this gathering. It views the tents as ‘urban rooms’ to enable conversations, encourage social action and display local aesthetics. Although there is a significant amount of field study on the festival, there has not been much focus on its mapping techniques beyond a figure-ground plan.

Re-positioning the local aims to bridge the gap between the illustrated and lived reality. Using the Kumbh Mela as a liminal space, the study attempts to interpret the city by choreographing alternate mapping methods to facilitate multiple visions and versions of the site.

(See, Fig.1.2)

Fig1.1 : Procession in the Kumbh Mela Source: Nunes, R.M as cited by Mehrotra, 2015

The thesis is divided into four major parts. The first partINTENT positions the purpose and objectives of the thesis. In Chapter 2, the study submits previous theories and arguments on temporal urbanism as well as recently evolved positions. The chapter situates temporal urbanism in the context of the ‘Global South.’ It further argues the issues in representing these cities through the standard mapping practices thereby erasing their distinctive urban conditions. It provides various positions of researchers on the current mapping practices and the need for alternate forms. Further, the research situates itself within Homi Bhabha’s ‘Third Space Theory’ and repositions the festival as a liminal space. Lastly, it maps the textual narrative of the Kumbh Mela over the years. Indian scholars like D.P. Dubey and his Western counterpart Kama Maclean, an Indologist have written extensively on the history and the origins of the Mela and provided extensive literary documentation. Chapter 3 elaborates upon the conceptual framework of this research. The chapter describes the history of cartography in India and its subsequent universalisation. It also describes the various representations of the Kumbh Mela by different agencies and highlights the gap in the current forms of mapping practices. Chapter 4 provides a hypothesis for this study which is to understand the Kumbh as a liminal space through alternate mapping methods.

The second part - SITE will elaborate on the site and its distinctive features. Chapter 5 details a documented and perceptive timeline of the festival and the various activities performed on-site. Chapter 6 situates the tent typology within the context of everyday urbanism and illustrates the modularity of the tent and its various uses in the Kumbh Mela.

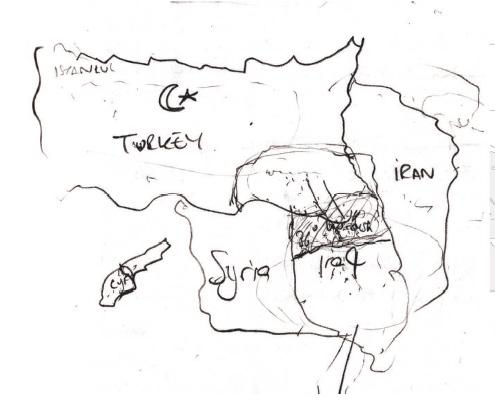

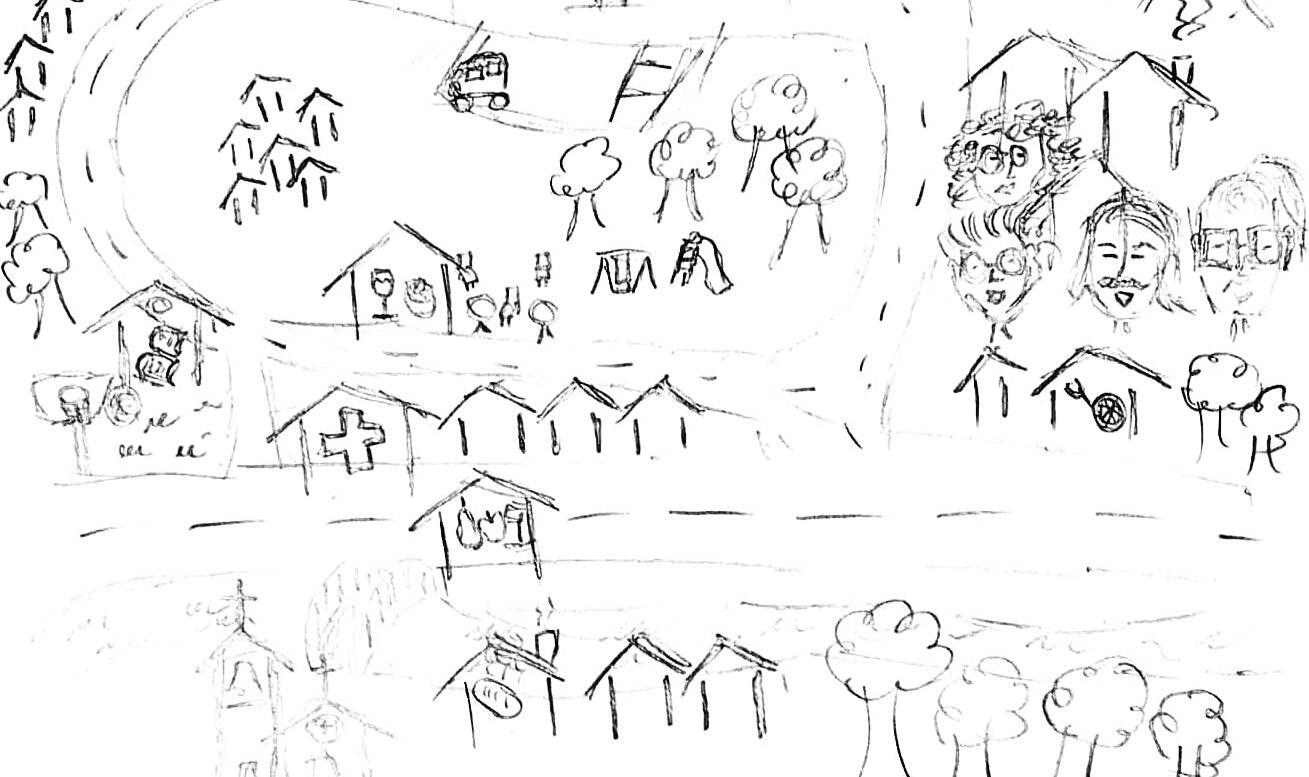

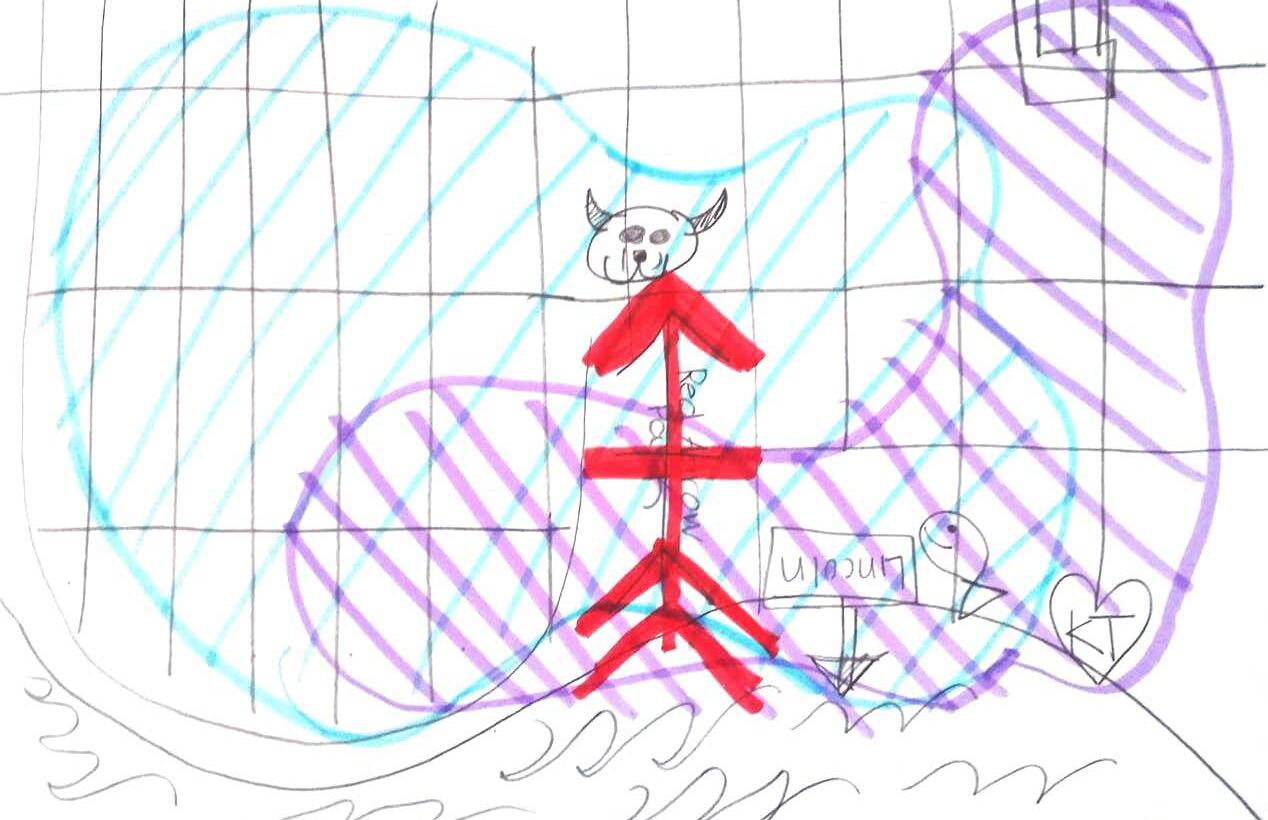

The third part - APPROACH focuses on the methodology of this project. Chapter 7 elaborates on the workshop ‘Map Your City’ and its outcomes. Chapter 8 discusses lessons learnt through the workshop and provides new ways of mapping urban spaces.

The fourth part - ARTEFACT of the thesis focuses on the visual tools created for mapping the Kumbh Mela. The last two chapters 9 and 10 will document the final artefact of the thesis and deliberate on the lessons learnt during this study.

The Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj is imagined as a laboratory to develop the visual semantics for assimilating and generating knowledge of the festival. Counter-mapping adds a layer of meaning to complex ideas and allows the growth of new possibilities and relationships within the space. The study does not dwell on the binaries of permanent and temporary cities or East and West perspectives but uses an opportunity to develop and represent the Kumbh Mela in the context of a third space in the public realm.

The research probes the following questions:

- What are the non-Western conceptualisations of the Kumbh Mela?

- What alternate mapping methods can be developed that embed the local cultures of the site?

- How can counter-mapping represent these sites of contested territory and their multiple spatial cultures?

- How can counter-mapping by drawing or visual aid be used as a tool to influence local planning?

The objectives of the research will be

- to reposition the local and challenge Eurocentric cartography’s validity and authorship in representing everyday life in a temporal city like the Kumbh Mela.

- to analyse the relationship between different interdisciplinary visual tools.

- to develop mapping as a tool to reflect/ represent local narratives and spatial cultures.

1. Prayagraj is an ancient name. The city was renamed Allahabad or Ilahabad during the Mughal period but was changed back to Prayagraj in 2018.

2. Recent studies led by Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad along with IIT Bombay in 2019 indicate the existence of the river Saraswati which flows below the ground arguing against the position of it being a ‘mythical river.’

For more, see, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6868222/

3. The festival is rotated among four river-bank cities every three years on the basis of the astrological positioning of the planets. The festival is called Kumbh (Aquarius) Mela in Haridwar, Magh (Capricorn) Mela in Prayagraj and Simhasta (Leo) Mela in Nashik and Ujjain. The festival becomes grand in its twelfth year when it is referred to as the Maha Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj.

4. For more, see, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/kumbh-mela-01258

Fig.1.3 : Ladies dry their saris (dresses) after taking a dip in the Ganga Source : Clarke, 20192: Literature Review

The following chapter cites literary sources on temporal cities and mapping practices. It repositions temporal urbanism in the context of the ‘Global South.’ The chapter situates the Kumbh Mela within Homi Bhabha’s Third Space Theory and argues for the need to develop alternate mapping methods. It also cites the documented narrative of the Kumbh Mela over the years.

Temporal Cities and Mapping Practices:

Temporary Urbanism is not a recent phenomenon. It is a response to the lack of adaptative or irreversible solutions produced through permanent urban interventions. It plays a role in the place-making process by creating a physical space for expression and producing new alternatives to the existing urban forms. Bishop and Williams (2012) state the importance of perceiving urban spaces as fourdimensional, the fourth-factor being ‘time’. They question the concept of a ‘masterplan’ and the preoccupation of planners with long-term solutions in the face of increasing economic and political uncertainties. Similar arguments are made by successive urban theorists (Tonkiss, 2013; Madanipour, 2017; Ferreri, 2021) in the domain of

temporal urbanism focusing on its politics and processes. They advocate the use of abandoned urban spaces for temporal purposes to create a ‘space of opportunity for some and vulnerability for others’ (Madanipour, 2017)

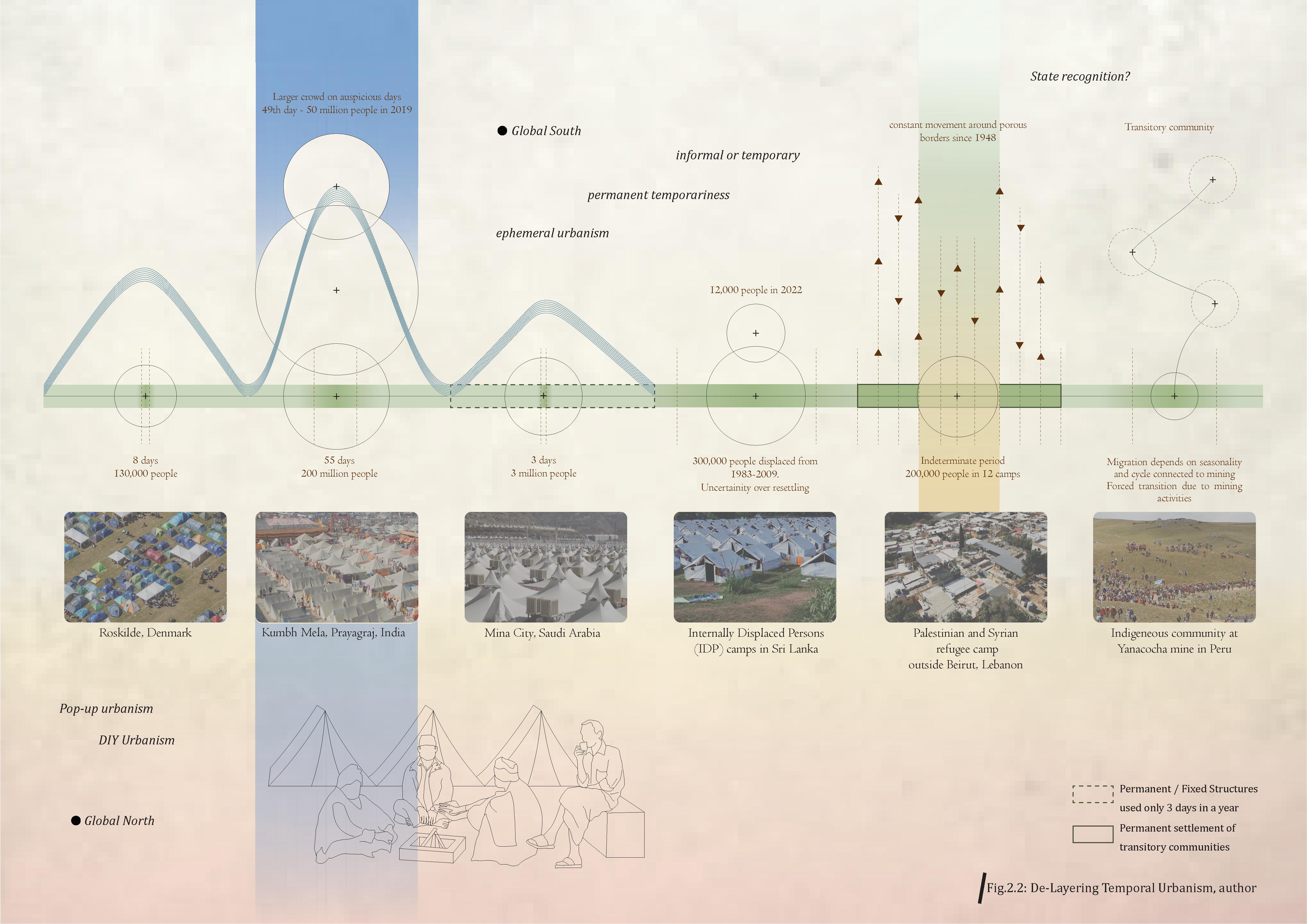

However, recent theories (Andres and Zang, 2020; García, 2020) indicate that most of the existing literature on temporal urbanism is predominantly based in the Global North with different sets of urban practices. They were focused on planning, use, legality, duration and financing processes. García (2020) explains that case studies cited in “Temporary Urban Spaces (Haydn and Temel, 2006), The Temporary City (Bishop and William, 2012) and Urban Catalyst (Oswalt et al., 2013)”, were focused on the emergence of temporal urbanism in North America and Europe. The various reasons mentioned by the author for the development of these practices include mainly political, financial and environmental. Similarly, Mehrotra and Vera (2015) cite multiple examples of temporary settlements that are constructed for religious and non-religious purposes like Mina City in Saudi Arabia, cultural festivals like Roskilde1 in Denmark and Coachella in California, settlements constructed in

refugee or disaster relief camps and some formed around ‘temporary geographies’ primarily due to the extractive and forest activities of the settlers (pp.161-162).

(See, Fig.2.1)

Although each of these cases varies in terms of the duration of the temporal condition, the socio-spatial patterns, origins and the local sense of place, they all get categorised under umbrella terms like ‘temporal cities.’ As suggested by García (2020), the temporal transformation in the ‘Global South’ is diverse and complex. In the overarching theme of temporal urbanism, what has been missing is the ‘recognition of geography and context-based processes’ (Andres and Zang, 2020), practices, spatial politics and their subsequent visual representation through mapping. The diverse and complex relationships of the sites are erased due to universal application and predetermined meanings of the vocabulary and representation. (See, Fig.2.2)

Fig.2.1 : Reversibilty of the Kumbh Mela Source : Mehrotra and Vera, 2013

Temporal cities are highly localised (Andres and Zang, 2020, p.4) in character making them ‘situated urban conditions.’ Hence, it is important to reconceptualize ‘temporality’ and its subsequent representation through mapping in the non-Western context. There are two main ways to do so:

- Recognize the diversity of temporal urbanism as a place-making tool

Temporal cities in the ‘Global South’ provide a wide range of examples where temporariness is redefined based on topography, socio-political context and cultural practices. The book, ‘Transforming Cities through Temporary Urbanism’ (Andres and Zang (Eds.), 2020) cites cases of temporal settlements in the Southern context and their role in the place-making process. Moawad (2020) describes the camps built by Palestine and Syrian refugees living on the outskirts of Beirut who are in a constant state of limbo. The refugees use their collective experience of ‘waiting’ to develop ‘specific place-making practices (p.73). These strategies create ‘temporal-spatial alternatives’

that are rooted in the framework of ‘sense of place, users and materiality’ (p.74). The scholar describes this condition as a state of ‘permanent temporariness’ (p.75) Mehrotra and Vera (2015) define the Kumbh Mela as a case of ‘ephemeral urbanism.’ Tents built during this festival are multi-scalar units. Besides sleeping, they also facilitate various other activities like listening to religious sermons, theatres, socializing and healthcare. All these tents are easily disassembled after the festival. The authors cite Andrea Branzi’s 2 theory of ‘Weak Urbanism’ and Richard Sennett’s ‘The Open City’ theory which proposes an incomplete form of a city based on reversibility and openness. Sennett reminds us that the shape of the urban space depends on how people appropriate it which gives it a ‘distinctive, non-exchangeable, different in form or function’ (Sennett 2013 cited in The Open City, 2018).

Both the above-mentioned examples are cases of localised temporal settlements (See, Fig.2.3) and vary in terms of their place-making strategies, spatial practices and duration of temporality. The research recognises the role of storytelling as a place-making tool in the context

of the Kumbh Mela. The rituals and performances associated with the collective religious beliefs have led to the development of different spatial alternatives. But despite the diversity in local conditions addressed in urban theories, mapping practices have not evolved beyond the universal cartographic systems. Therefore, this project addresses the gap in the mapping practices of these temporal cities and creates alternate mapping tools to reframe what already exists and ‘unfold new realities’ (Corner, 1999).

- Mapping temporal cities beyond the visible characteristics

Although the 2015 Harvard study (Mehrotra et al., 2015) described the unique nature of the Kumbh Mela, the mapping methods used were focused on the planning and urban management of the festival. As planners, the scale of the research was wider and hence the emphasis was on the urban processes and not representation. New space is created every time new people encounter it, therefore mapping unlike planning is not a closeend project nor a projection of reality (Corner 1999).

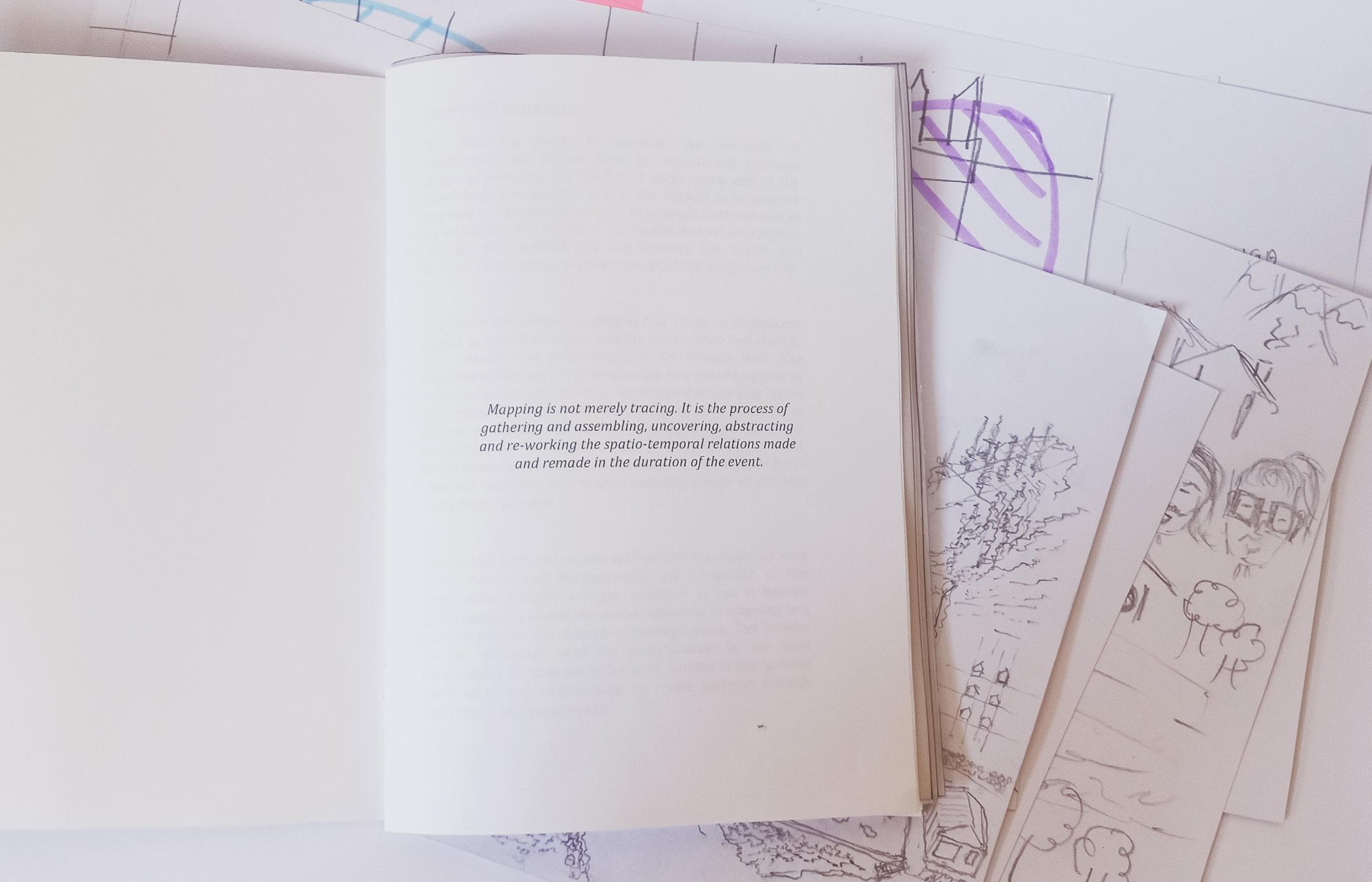

Mapping is a continuous process and is based on relational and context-based practices (Wood and Fels, 1986; Corner, 1999; Kitchin and Dodge, 2007; Awan, 2017). The social, territorial and political interrelationships formed in the temporal city are complex, diverse and dynamic and the orthogonal system of representation flattens these relations and experiences.

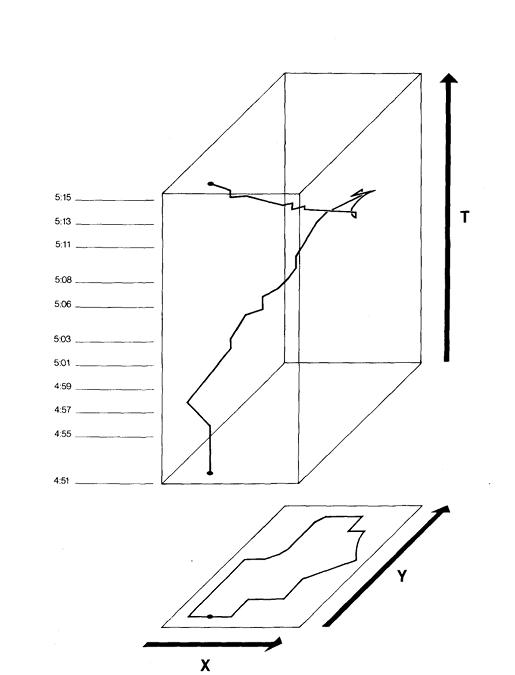

Mapping is particularly complex in places that are ‘inbetween’ due to the transitory nature of its users and their activities. Hence counter-maps are produced to overcome the standard tropes of mapping and representation. These maps are beyond the ‘rationalised Western model’ (Awan, 2016) of cartography to reclaim the agency of the transitory communities. Alternate mapping practices as suggested by Nishat Awan in her research paper, ‘Diasporic Agencies: Mapping the City Otherwise’ include mapping methods3 undertaken by native transitory communities before the acceptance of standard cartography as a norm. These counter-cartographic methods ‘map something other than the earth and its geography’ (Awan, 2016, Chap 7, p.1). These include mapping ‘emotions and narratives’, events, trans-local activities and networks, organisations, borders etc (Awan, 2016, Chap7, pp.1-2). However, time is a central theme in temporal urbanism. Many mapping theorists (Wood and Fels, 1986; Corner, 1999, Awan 2016) have described the inadequacy of the current mapping practices to illustrate space and time. As Wood and Fels (1986, p.83) remark in their journal article, ‘Design on Signs/Myth and Meanings in Maps’ ‘We have to see a map as having thickness in time.’ As we are more interested in mapping the local behaviours of a place, we need to recognize that ‘maps embody time’ just as ‘they embody space’ (Wood and Fels, 1986, p.82) (See, Fig.2.4) New technologies like remote sensing and GIS are used today to map spatio-temporalities of a place but what is not recognized is that these empirical data-driven mechanisms ‘create new opacities that even the most advanced seeingdevices’ producing spatial patterns ‘cannot dispel’ (Mackenzie and Munster, 2019 cited in Awan, 2020) .

Fig.2.3 : (on left) Palestinian settlement in Lebanon (on right) Kumbh City Source: Moawad, 2020 Source: Mehrotra, 2015 Fig.2.4: Space - Time map Source : Wood and Fels, 1986This research redefines Kumbh Mela as a liminal space that facilitates trans-local cultures, people and practices. It repositions the site as a ‘Third Space’ that has used storytelling as a place-making strategy to attract millions of people over the years for a singular purpose. It uses counter-mapping as a methodology to recognise the complexity and diversity of the temporal transformation of the Kumbh Mela and the need for an adequate visual representation of cities in the ‘Global South.’ (See, Fig.2.5)

Fig.2.5: Kumbh as a Third Space, author

Fig.2.5: Kumbh as a Third Space, author

Kumbh as a Third Space and its Historical Narrative :

The study forms an enquiry into the nature of the festival as a liminal space and its representation. Mehrotra and Vera (2015, p.69) describe the site as “an interstitial space between three distinct locales – the city of Allahabad4 from one side, the small industrial village of Jhunsi from the other, and a still underdeveloped span of rural land between.” Due to its physical location, Kumbh City plugs in the existing systems and infrastructure of the surrounding permanent settlements for its efficient functioning.

Given the number of records published on the Kumbh Mela by Indian and foreign scholars, this work classifies various approaches towards the festival into four distinct categories: exoticist, magisterial, curatorial (Sen, 2006, p.141) and catalytical. The first three are based on Amartya Sen’s classification in his book ‘The Argumentative Indian’ but the fourth category is added on through this project.

Catalytical Approach

This research is based on the catalytical approach. The earlier three methods can be applied universally but this method is localised in the cultural geography of the site. Stories and legends act as catalysts to enable the identity of a place. The Kumbh is a site of cultural collaboration between various stakeholders in the public and private realms. It is also a site for various groups of ascetics who live a secluded life to establish their presence. Some people also renounce their previous lives to become sadhus, thereby attaining a new identity during this festival. The re-appropriation of space by religious groups to assert themselves in a Statefunded festival leads to the Theory of Third Space.

The concept of the ‘third space’ as introduced by Homi Bhabha in The Location of Culture provides the theoretical framework for this research. Third spaces act as interstitial spaces that “provide the terrain for elaborating strategies of selfhood –singular or communal – that initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself” (Bhabha, 2012, p.2). While previous studies have focussed on the origin and history, urbanisation and planning, this research views the festival as an in-between space where collective experiences are formed. Tents built for this event act as ‘urban rooms’ promoting cultural engagement which provides a common purpose for the congregation. This leads to ‘cultural hybridity’ between various participants. Cultural hybridity as defined by Bhabha is the one that “entertains difference without an assumed or imposed hierarchy” (Bhabha, 2012, p.5). Unlike Lefebvre’s theory of differential space, which is a universal idea of left-over spaces, Bhabha’s theory of third space is more specific as it addresses places of social differences along with its conflict and negotiations.

Curatorial Approach:

The seminal text, ‘Prayaga, the Site of Kumbha Mela’ by D.P. Dubey (2001) is an example of a curatorial approach. The literature compiles extracts from different religious texts like the Vedas and Puranas, the Epics and other literary sources to uncover several myths about the origin and history of the revered site. Kama Maclean’s (2008) ‘Power and Pilgrimage’ documents several discourses on the Kumbh festival. The literature consists of the popular media and textual representations of the place, the evolution of the festival from the 18th to the 20th century and its changing relationship with the State.

Magisterial Approach:

The magisterial approach is an imperial attitude towards Indian culture by overlooking native traditions. Kama Maclean (2008, p.86) mentions examples of British editors in Statistical, Descriptive and Historical Account of the North-Western Provinces dismissing the religious text describing the Kumbh pilgrimage as “purely mythological and full of absurdities. No trustworthy information can be derived from it.” She also cites Thomas Macaulay who in his document, ‘Minute upon Indian Education’ derided the local story of Kumbh by calling the place a “geography made of seas of treacle and seas of butter” (Macaulay, 1835, para.13 cited in Maclean, 2008, pp.86-87) There was an imposition of a Eurocentric model of governance (Maclean, 2008, p.87). However, some within the colonial society defended the Mela as an integral part of the Hindu religious beliefs and hence should not be resisted by the State.

Exoticist Approach:

The exoticist approach is mostly applied to the ones who have perceived the Kumbh as a strange phenomenon. Many scholars in the previous centuries have recorded the event as a popular guidebook, without probing into its antiquity. The focus of their study was on the ‘wondrous’ nature of the site. Articles by English journalist E.L Brown in 1870, Mark Twain in 1895 (Dubey. S.K, 2001, pp.74-77) and several Indian authors in the past have recorded their observations and experiences of the gathering but from a distant perspective. These literary sources provide an insight into the vast expanse of the existing historical narrative and positioning of the festival.

1. Vagnby and Schultz (2012) in their article, ‘Citizen as Urban Co-Producer’ describe the planning process of the Roskilde festival in Denmark. The internal organisation of the city is planned through a democratic process within the structure and framework provided by a city plan making the participants ‘creators and experience a sense of ownership’ towards the spaces they produce. The festival is attended by over 130,000 people. It is ‘conceived as a city’ built over a period of a few weeks for an eight-day event. For more, see, https://www.udg.org.uk/ sites/default/files/publications/UD122_magazine%20(2)_0.pdf

2. Andrea Branzi through an architectural studio, Archizoom, produced a speculative project ‘No Stop City’ in 1969. This theoretical project challenges the permanence of architectural practice by turning the practice against itself and designing strategies for the urban adaptability of cities. The city is designed on an orthogonal grid as a neutral, continuous, mobile and flexible structure. It allows individuals to build their own space thereby formulating new dwelling typologies that foster new community relations. ‘No Stop City’ is a project that is conceptualised as a ‘social factory’ that neutralises figurative architecture thereby reducing a city to its ‘biopolitical spaces of production and reproduction.’

3. For further study on mapping practices, see, Nishat Awan, Diasporic Agencies: Mapping the City Otherwise, Google Books (Ashgate Publishing Company, 2016), 2-28.

4. Allahabad is the former name of the city. In 2017, the State Government of Uttar Pradesh changed the name of the city to Prayagraj.

3: Conceptual Framework

The chapter questions the universal methods of mapping that flatten context-based systems. The chapter further describes the representation of the Kumbh Mela by various actors/agencies and suggests the need for an alternate language for mapping.

Mapping as a form of producing and disseminating knowledge has existed since the beginning of human civilisation. Earlier forms of mapping1 included native folk-art paintings, Jain cosmological maps, pilgrimage maps and manuscript paintings that produced a wealth of cultural and historical knowledge about the places. They gave an insight into the everyday life of the local people thereby accentuating their agency and power in representing local and regional narratives. With the advent of the Colonial State, there was a common codified language of mapping established thus flattening the local sense of place.

This research questions the Euro-centric model of mapping to represent the cultural geographies of India. It aims to generate counter-cartographies to uncover the material and affective nature of the space that triggers the workings of a place.

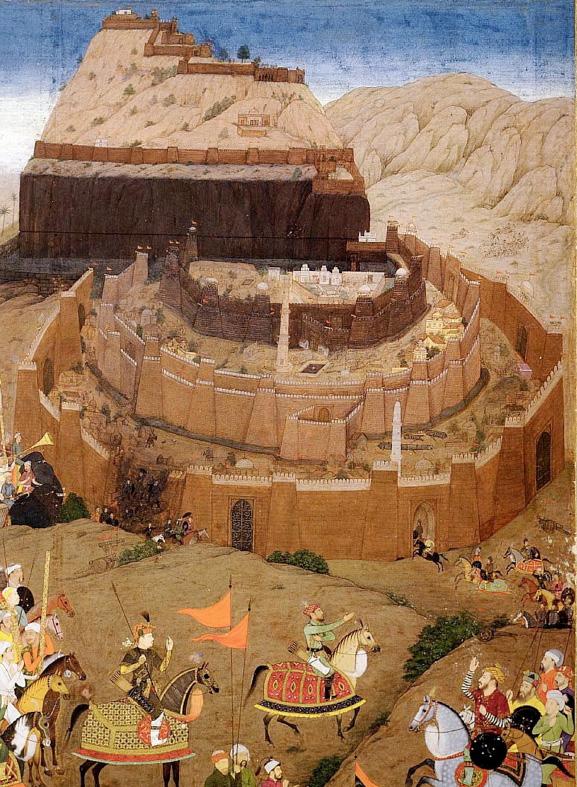

The introduction of cartography in paintings was a means to exert positionality in society during the medieval period. New representational techniques were explored by native painters and mapmakers. Maps were a ‘source of power’ not depending on ‘actual conquests and territorial capture’(Koch, 2012, p.565). Many British cartographers were assisted by native artists in the production of maps. The use of a bird’s eye view, scale of spaces and perspectives which were features of European cartography, were being reproduced to local sensibility by native painters and mapmakers.2

Local artists used the new techniques of spatial representation layered with allegories and symbolism to produce ‘different kinds of knowledge systems’ (Koch, 2012, p.578) thereby asserting their power (See, Fig.3.1). Today, the universal coded language of mapping has eliminated any dialogue through mapping between diverse cultures.

Oriental paintings of Prayagraj by Charles Ramus Forrest were focused mostly on the landscape rather than the subjects. Unlike native paintings, the Europeans paid more attention to the topography and picturesqueness of the site. The popular visuals of the Kumbh Mela include the depiction of the mythological story showing the gods and demons churning the ocean to produce the nectar of immortality. The official government websites also depict similar images regarding the origin of the festival.

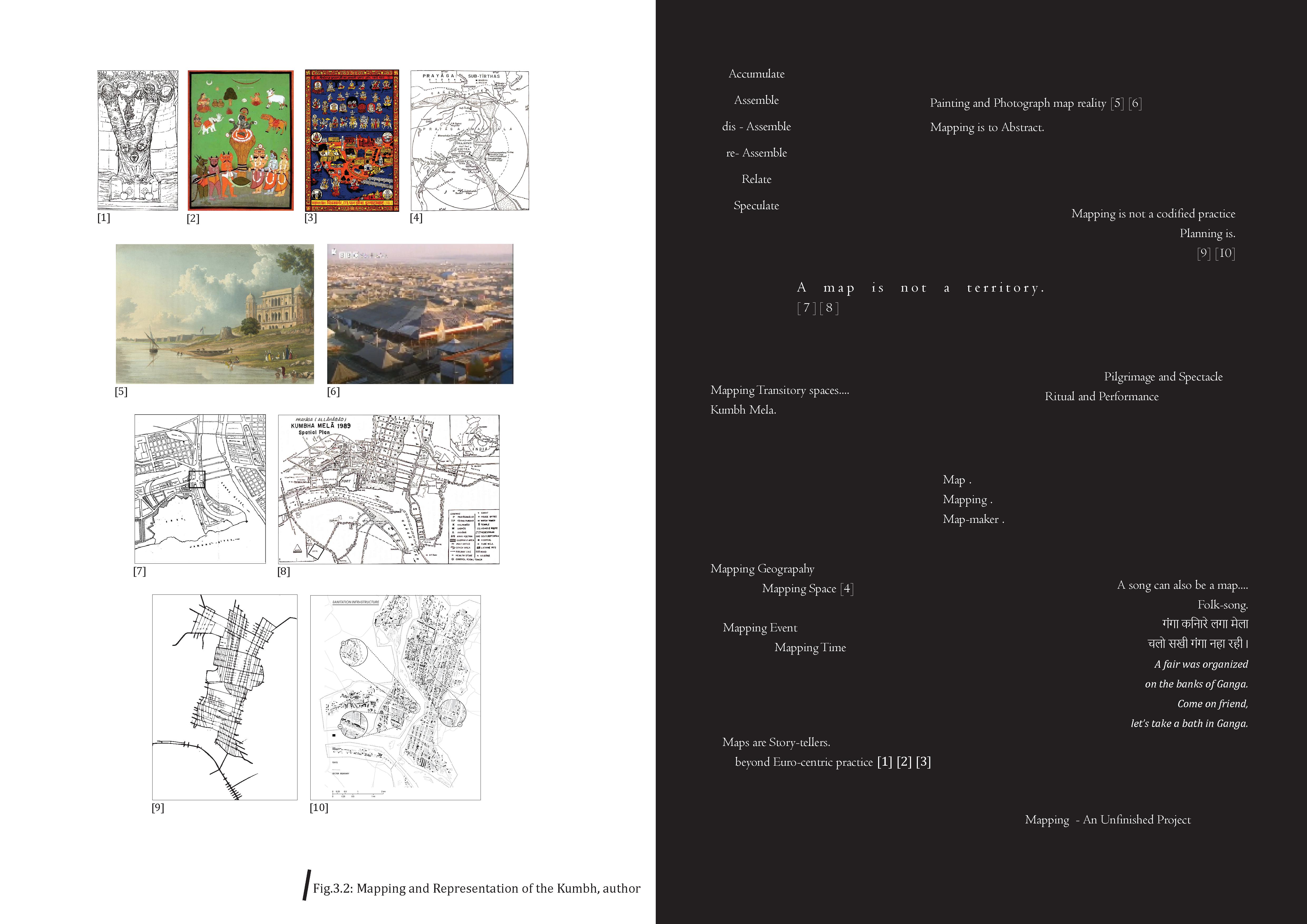

Masterplans are produced by the State to decide the grid layout of the site. According to Mehrotra and Vera (2015), the grid is a neutralising element as it allows religious communities to appropriate the land as per their needs. (See,Fig.3.2) But, Corner (1999, p.94) emphasises the difference between maps and plans. The experience of a space cannot be differentiated from the event happening in it. Such ‘relational systems’ (Corner, 1999, p.94) cannot be represented on a plan and thus plans are different from maps. A similar position is held by other scholars (Wright, 1942, p.305; Kitchin and Dodge, 2007, p.113) like Mesquita (2018, p.30) who states, “territory produced by the map is multiple, not only spatial, but also temporal and social: it extends from the place where the maps are produced – with its stories, reports and vestiges – to the countless situations in which they are distributed, accessed and used.”

Fig.3.1: Dialogue between European and Indian map-making techniques. The view of the image on the left resembles the view on the right due to influence of Western cartography, yet the local sensibilities were considered while representing . (on left) Pictorial representation of Daulatabad during Mughal reign (on right) Map of Wurzburg Source : Koch, 2012

Fig.3.1: Dialogue between European and Indian map-making techniques. The view of the image on the left resembles the view on the right due to influence of Western cartography, yet the local sensibilities were considered while representing . (on left) Pictorial representation of Daulatabad during Mughal reign (on right) Map of Wurzburg Source : Koch, 2012

The Kumbh Mela is a temporal event that acts as an urban theatre in a liminal space (See, Fig.3.3). Time and socio-spatial relations are central themes of this event. Tents act as third spaces where new relations and active interactions take place. “A different approach to mapping that does not rely on standard cartographic conventions will also imply a different understanding of space and time” (Awan, 2017, p.35). According to mapping theorist James Corner mapping involves an act of ‘accumulation, disassembly and re-assembly’ (Corner, 1999, p.95). It is a process of extracting ‘new latent relationships.’ (Corner, 1999, p.95). Similarly, Nishat Awan, a South-Asian scholar of countermapping also states, “A key feature of all maps is their ability to visually depict different realities by distilling and privileging some information over others” (Awan, 2017, p.33). The power of mapping to produce multiple narratives will increase its accessibility (Corner, 1999; Kitchin and Dodge, 2007; Awan, 2017). The following research deviates from the rigidity of the current cartographic practises to establish new modes of understanding spaces.

Images (previous page) :

[1] Akshayavata Tree

Source: Dubey, D.P., 2001

[2] Mythological Story of Kumbh

Source: Kumbh Mela.co.in, n.d.

[3] Map of Kumbh Mela with all religious and secular symbols and institutions

Source: www.harekrsna.com, n.d.

[4] Cosmological map of Prayag (sacred zone)

Source: Dubey, D.P., 2001

[5] Painting of Triveni Sangam by Charles Ramus

Forrest

Source: Wight, 1824

[6] Congregation Tent, filmed by BBC

Source: Bedi and Yorke, 1989

[7] 1954 Plan of Kumbh Mela

Source: Maclean, 2008

[8] 1989 Plan of Kumbh Mela

Source: Khanna, 2017

[9] Grid Layout of 2013 Kumbh Mela

Source: Mehrotra et al., 2015

[10] Figure ground plan of 2013 Kumbh Mela

Source: Mehrotra et al., 2015

1. For more on Indian cartography, refer to https:// artsandculture.google.com/story/QwWBZeSPJNhTKA and https://artsandculture.google.com/story/NgXRzO0BWWZ3J

2. For more on the relation between British cartographers and Indian artists, see,

Dipti Khera, The Place of Many Moods: Udaipur???S Painted Lands and India???S Eighteenth Century, JSTOR (Princeton University Press, 2020), 117-146.

For representation of the European ‘globe’ and ‘atlas’ in Indian paintings, see,

Ebba Koch, “The Symbolic Possession of the World: European Cartography in Mughal Allegory and History Painting,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55, no. 2-3 (2012): 547–580.

Fig.3.3: (image on right) The Main Road in the Kumbh City Source : Bryan Denton, 20194: Hypothesis

This chapter states the research question and its aims. It summarises the intent of the project. It also describes the evolution of the Kumbh into a religious fair thereby claiming the site is remade every twelve years not just as a physical city but through renewed social relations.

Urban theories proposed today are often supported by maps that mirror reality because mapping is understood as an analytical process over a creative one. The site is reconstructed from an aerial vantage point which loses the immediacy required to reimagine local geographies. Mapping practices use dominant tropes of representation rather than the lived experience of the site. Mapping is a ‘cultural intervention’ (Corner, 1999, p.91) and ‘unlike paintings or photographs’ or films ‘which have the capacity to bear a direct resemblance to the things they depict, maps must by necessity be abstract if

they are to sustain meaning and utility’ (Corner, 1999, p.93).

Narrative mapping was a common practice in India before the introduction of Western cartography. Often, these were pictorial translations of a poem or story. The artists would depict the topography of the place along with its ‘ephemeral and emotive aspects’ (Khera, 2020, p.15). Indian map-making also included the production of pilgrimage maps called ‘Tirthpatas.’ Gazing at this map was an act of a pilgrimage. These were ‘mental pilgrimages’ (Goswamy, 2023) (See, Fig.4.1) undertaken by devotees who were unable to go on a physical one. None of these maps was drawn on a uniform scale. The focus of these maps was on the sensorial experience of place1. This mode of mapping was made with ‘place-centric imagination’ (Khera, 2020, p.24) and ‘localising of moods’ (Khera, 2020, p.173) of the place.

Cultures are a dynamic phenomenon that is constantly changing as individuals navigate between beliefs, traditions and modernity. With the physical expansion of the Kumbh Mela since the mid-19th century, its social messaging has also evolved. Since the early decades of the 20th century, the festival has also been used as a platform for political purposes (Maclean, 2008). The Kumbh Mela is covered excessively through the media and film documentaries. The naked ascetics use this occasion to assert themselves by allowing cameras to capture them. They affirm their presence through an act of seeing and being seen by the public (Maclean, 2009)2

While describing the meaning of existential spaces, Edward Relph states, “Existential space is not merely a passive space waiting to be experienced, but is constantly being created and remade by human activities” (1976, p.12). He further states, that in doing so humans “create unselfconsciously patterns and structures of significance through the building

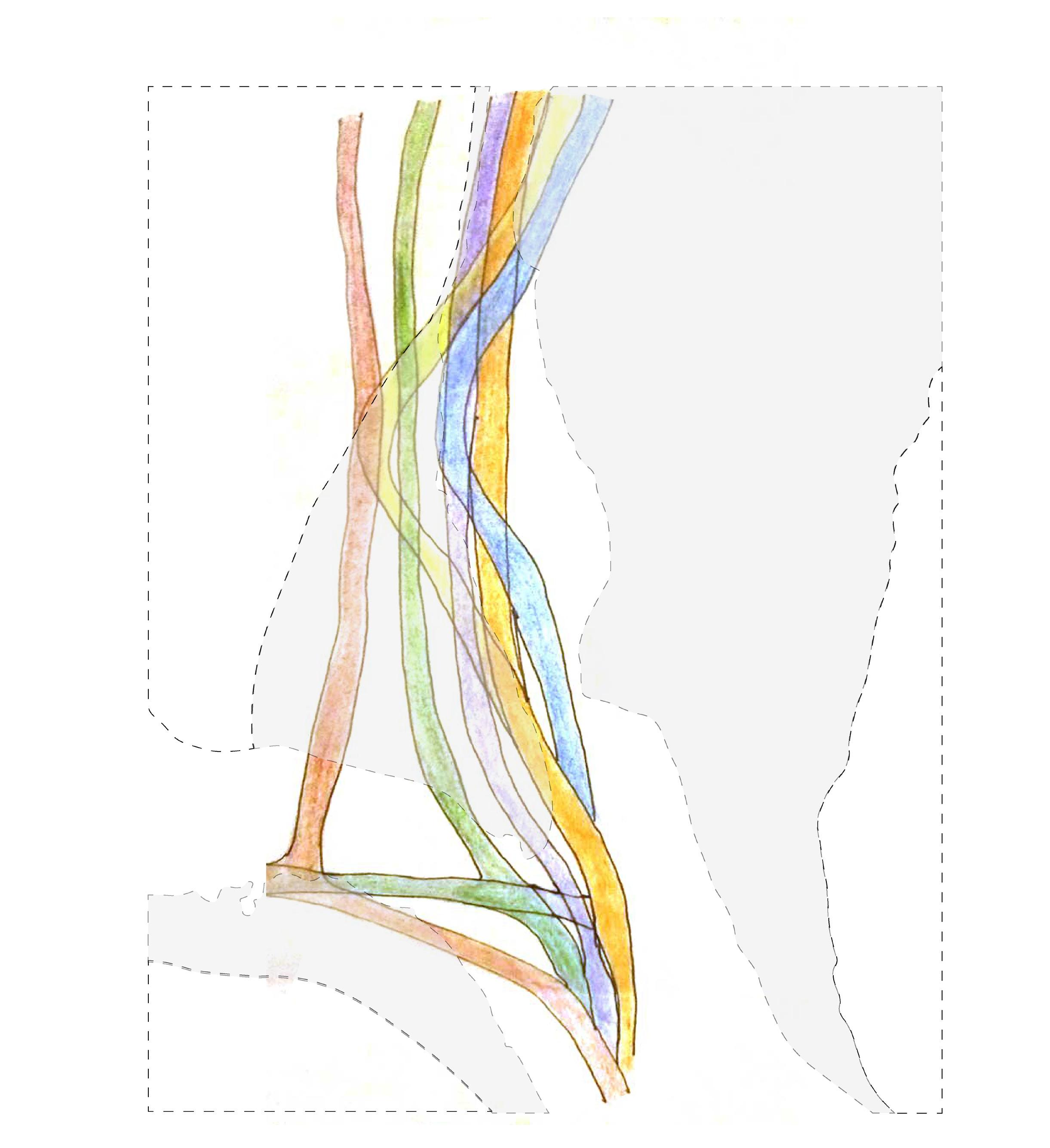

of towns, villages, and houses, and the making of landscapes” (1976, p.12). As the Kumbh Mela grew larger, it also led to the involvement of the otherwise marginalised sections of society like the transgender community. The processes involving providing food and accommodation for the pilgrims increased in capacity. So did the surveillance and crowd management systems increase due to the history of stampedes during this gathering. As new technologies, processes and people got involved, the socio-spatial relations renewed and mutated which led to a constant re-territorialization of space (See, Fig.4.2). The concept of re-territorialization borrowed from Deleuze and Guattari (1837 cited in Awan, 2016) is how social relations get formed and affect the space. The Kumbh Mela is an example of a space which is constantly made and remade every twelve years not just physically but also through renewed sociospatial relations. Therefore, the question is how can mapping as a practice shift from representing static spaces to dynamic place-time-object- relations?

1. For more on Indian cartography, see, Dipti Khera, The Place of Many Moods: Udaipur???S Painted Lands and India???S Eighteenth Century, JSTOR (Princeton University Press, 2020).

2. For more on media and ascetics, see, Kama Maclean, Seeing, Being Seen, and Not Being Seen: Pilgrimage, Tourism, and Layers of Looking at the Kumbh Mela, Crosscurrents, 59[3] (University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

Fig.4.2 : Gates and Flags as visible markers on site emphasising their belief systems and creating new territories with the larger temporal city. Source (top) : Vera, 2015 (below) : Mehta, Dinesh, 2015PART 2 : SITE

5: Making of a Third Space - The Kumbh Mela

The following chapter summarises the essence of the Kumbh Mela by illustrating the origins and the meaning of the festival, its physical setting, the activities of the pilgrims and the spirit of the place. The chapter describes various belief systems and urban processes within the site that make it a ‘Third Space’.

The Kumbh Mela is a spatial experience based on its sacred geography, rituals and performances and histories and myths. Stories as tools of place-making play an important role in shaping the identity of the Kumbh (See, Fig.5.1). ‘Place-making’ is a process that encapsulates the socio-spatial relationship within a common placeframe (Pierce, Martin and Murphy, 2010, p.54). Placeoriented scholars who have written literature on social movements and politics have described place-frame as a shared understanding of a place that can motivate a collective response (Pierce, Martin and Murphy, 2010, p.55). The spatial experience of a place can be both intimate and bodily or cognitive and abstract.

Thus, the identity of a place is created based on three essential components – physical setting, activities and meaning (Relph, 1976, p.47). The practice of counter-mapping the Kumbh required a shift in thinking approach - from a Euclidean space of absoluteness to a relational space of continuity.

The Meaning…...

Magha Mela1 is an annual religious congregation involving a bathing ritual at Prayaga (the sacred space at Prayagraj). The origins of this annual fair can be traced back to the Gupta period (4th - 5th-century C.E). This event becomes momentous in its twelfth year when it is called ‘Kumbh Mela.’ The popular folklore associated with the Kumbh Mela is the story of the ocean churning that produced a pitcher containing the nectar of immortality. While protecting the pitcher from the demons, the nectar splashed in four different places in India – Prayagraj, Haridwar, Nashik and Ujjain, making them sacred sites where the festival is celebrated every three years in rotation. According to D.P. Dubey (2001, p.130), though the story of ocean churning is mentioned in the Epics and the Puranas (ancient Indian literature), the splashing of nectar is nowhere mentioned. The author suggests the story has been ‘verbally grafted on the Kumbh Mela to provide it with an antiquity and hoary past’ (p.130) Similar, legends and folklore associated with the festival are mentioned in these ancient literary texts. During the Kumbh, many local artists painted large murals throughout the city depicting mythological stories thereby signifying and reiterating the importance of this festival.

The Kumbh Mela is believed to be an ‘ageless’ festival. Many historians (Dubey. D.P., 2001; Maclean, 2008) have raised questions on the historicity and origins of this festival at Prayagraj. Dubey (2001. pp.122,128) explains that although a bathing ritual has been mentioned in the Rig Veda (oldest Vedic text), no hymn or verse cites the actuality of a festival or a religious congregation at Prayagraj. The followers of the Mela cite other literary texts2 to validate the origins of the festival. Some scholars claim that ‘the pilgrimages known as Kumbha Mela do not date back the seventeenth – eighteenth-century C.E. (Dubey. D.P., 2001, p.127; Krasa, 1965 cited in Maclean, 2008, p.85). Dubey (2001, p.127) suggests that no pattern has been yet discovered regarding the historicity of the event and most of the information is based on an oral tradition. The author describes the festival brochures cite verses from the Puranas (written in the Later Vedic period) to position themselves in history (pp.131-132).

The traditional belief is, that it was Shankaracharya (ancient Indian scholar) who in the 9th century C.E. organised the festival of the Kumbh at Prayaga. He transformed the ‘gathering of single group and local significance into a pan-Indian meeting of ascetics and extended it to the other three sacred places’ (Dubey. D.P., 2001, p.138) - Haridwar, Nashik and Ujjain. Dubey (2001, p.139) claims the twelve-year tradition of the festival also has many theories, none of which are supported by any written records. The Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj was organised only after the 12th century C.E. according to the evidence cited by the author (p.140). This period coincided with the Bhakti Movement in India which was a socio-religious movement in the medieval period of Hindu saints and reformers.

Despite the lack of a comprehensive historical record, the Mela retains its existential purpose for the devotees through its myths, legends and cultural memory, thereby attracting millions of people to the confluence of the rivers for a mass- bathing ritual.

Fig.5.1 : The spirit of the place - Kumbh Mela Source : Pandey, 2019Physical Setting……

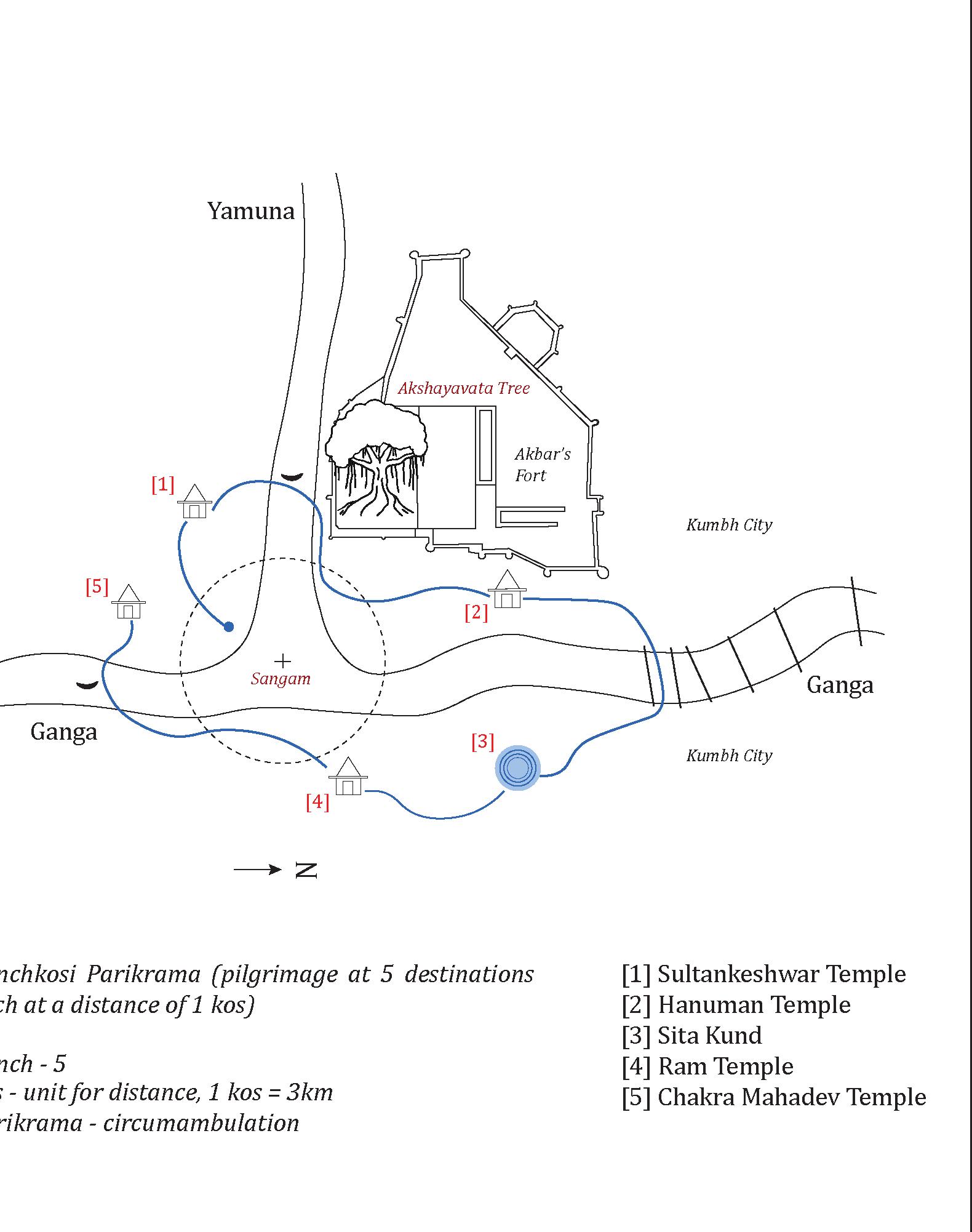

The sacred space of the site was historically mapped as a Prayaga Mandala (See, Fig.5.3). Mandala is a cosmological symbol that would imply the transformation of the universe. The landscape was ‘demarcated, differentiated, and objectified into something spatially distinct’ (Dubey. D.P., 2001, p.14). The holy spots around the site have multiplied in number over the centuries, reflecting different traditions of Hindu civilization within the sacred zone. Besides Sangam, the meeting point of the rivers, other objects include the Akshayavata tree (Banyan / Indian fig tree) and eighteen other temples and bathing points located along the banks of the two rivers.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, the format of the Kumbh Mela has expanded greatly from a bathing ritual to a religious fair.3 The festival includes devotional activities, performances of local and folk artists from different parts of the country, health and social infrastructure, pontoon bridges to facilitate movement of

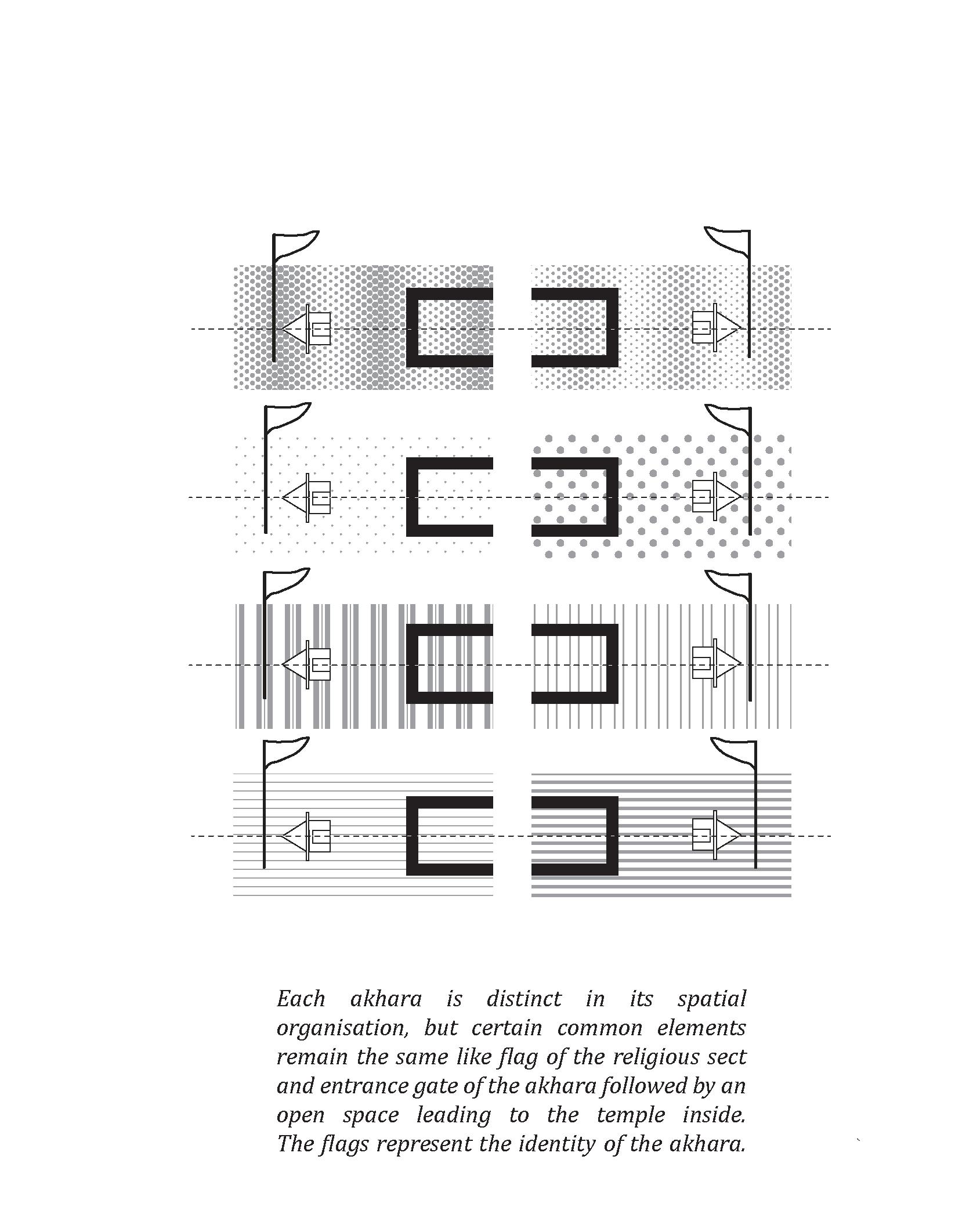

people, water and power supply and shops with essential commodities and religious paraphernalia for the pilgrims. For this purpose, an urban grid is laid on the site of the Kumbh that is divided into sectors, each configured differently into having its own camp. The grid layout is a colonial construct (Mehrotra et al., 2015, p.71). The grid structure is decided based on the morphology of the site. Post-monsoon as the river recedes, the layout of the Kumbh is decided based on the final shape of the landform. Hence the spatial plan of the site is different for every Kumbh. Research conducted by Harvard (Mehrotra et al., 2015, p.73) highlights the uniqueness of this grid compared to other temporary settlements as not being ‘repetitious in a way that erases originality and identity’. The akharas are given the liberty to decide the internal structure thereby giving them the agency to self-expression. As a result, the internal organisation of camps in each sector is different. This form of hybrid urbanism leads to adaptability and local empowerment thereby allowing each group to devise their own spaces.

Fig.5.3 : The Cosmological Map of Prayaga (the sacred zone at the Kumbh)

Source : Dubey, D.P., 2001

Fig.5.3 : The Cosmological Map of Prayaga (the sacred zone at the Kumbh)

Source : Dubey, D.P., 2001

Activities…...

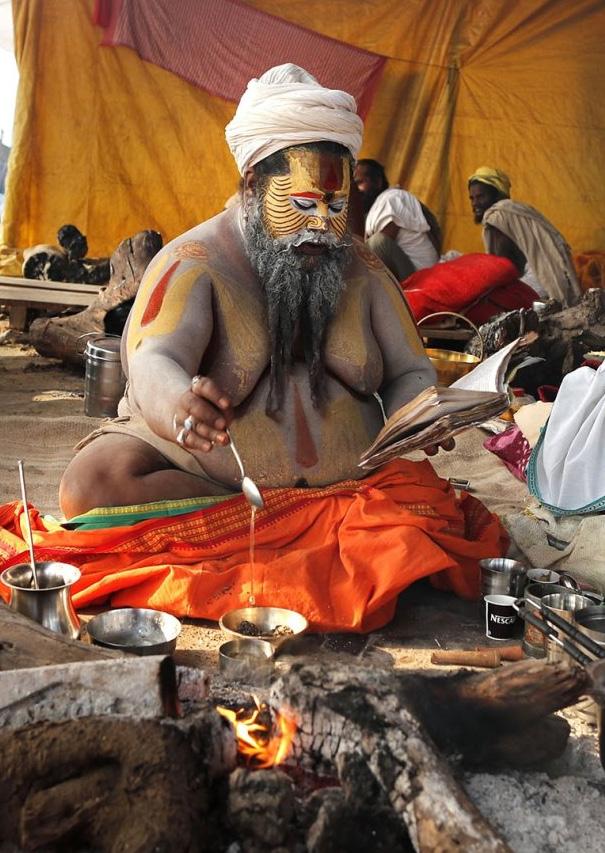

Dubey (2001, p.141) suggested the Mela originally belonged to the Naga sadhus (militant ascetics) and other groups of monks joined eventually making the event a ‘congress of ascetics and monks.’ During important bathing days, a procession of ascetics marches down towards the point of confluence. The order in which the groups of ascetics would bathe was set in 1879 by the British Government (Dubey. D.P., 2001, p.142). Till today, the order largely remains the same. The time of bathing is most crucial to the religious groups. The pilgrimage to Kumbh involves performing rituals and religious rites like fire oblation, worship of deities, fasting, charity, bathing, listening to religious discourses (See, Fig. 5.4) etc.4 The festival is a physical and mental journey taken by the pilgrims over two months. Not every pilgrim stays for two months. Some arrive only for the auspicious

occasions and some stay on the site for an entire month. The pilgrims who stay for a month are called kalpavasi. Many people participate in the initiation ritual as well where they give up on their regular lives to become ascetics. The food production and distribution during the Kumbh Mela is managed by both religious and private organisations in large tents and is free for pilgrims and visitors. Each akhara brings its own supplies for its followers and other pilgrims on site. Organising fresh supplies from nearby markets, cooking and providing food to the attendees in the langar is managed by the volunteers associated with the akhara (Mehrotra and Vera, 2015). According to Maclean (2008, pp.118-119), market forces in the 1800s had altered the nature of trade at the Kumbh Mela, from Persian and Arabic luxury items to religious paraphernalia. Today, most of this market is set up on the outer edges of the temporary city.

Sense of Place......

Besides the above three components, Relph (1976) also states the ‘spirit of the place’ or the ‘sense of place’ as a key feature of its identity. He describes the ‘sense of place’ as the uniqueness of the site that it has ‘retained through subtle and nebulous changes’ (p.48) in the surroundings. Nature worship has been an important feature since pre-historic times. The Kumbh Mela is first and foremost the largest event of worshipping a waterbody. In the native religious life, the waters of Ganga are considered holy and contain purifying qualities.

The distinctive feature of the site is the confluence of the rivers which has been a point of attraction for many seers and ordinary people alike. Many native poets5 have sung verses describing the confluence of Ganga and Yamuna as the confluence of white and black/blue rivers. In an agricultural-driven economy such as India, river water as a source of irrigation plays an important role in the sustenance of the communities. Indic civilization has expanded along the banks of these rivers. Hence, people from different corners of the country despite all the differences seem to come together for this religious congregation.

1. Magh Mela, the local annual fair at Prayagraj has been known since antiquity with many observer accounts. The written records of the historicity of this event range from the Gupta Empire (4th -5th century) to Mughal rule (15th -17th century). For more on the historicity of Magh Mela, see, D Dubey, Prayāga, the Site of Kumbha Mela (2001; repr., New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2001), 123-125.

2. Some believe the first account of such a festival is documented by a Chinese traveller Hsuan Tsang in 643 C.E. (7th century), during the reign of Harshvardhan, a king in Northern India. According to this account, religious festivities held on the banks of the river Ganga would occur every five years where the king would donate riches to the poor. According to Dubey (2001), the Chinese pilgrim did not refer to the fair as the Kumbh Mela, hence the events cannot be related. See, D Dubey, Prayāga, the Site of Kumbha Mela (2001; repr., New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2001), 138.

3. For more on the expansion of the Kumbh Mela over the years, refer to population data, see, D Dubey, Prayāga, the Site of Kumbha Mela (2001; repr., New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2001), 145-148. Shiva Kumar Dubey, Kumbh City Prayag (New Delhi: Centre for Cultural Resources and Training., 2001), 77-78.

4. For more on sacred rituals, see, D Dubey, Prayāga, the Site of Kumbha Mela (2001; repr., New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2001), 74-103.

5. Poets like Kalidasa (4th -5th century C.E.), Subandhu (6th century C.E.), Banabhatta (first half of 7th century C.E.) and many others. For more, see, D Dubey, Prayāga, the Site of Kumbha Mela (2001; repr., New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2001), 17-18.

Fig.5.4: Rituals performed during the Kumbh Festival, snana (bathing), dana (charity) and homa (fire oblation) Sources : (Image 1) Bryan Denton, 2019 (Image 2 & 3) PRESS, 2021 Snana Dana Homa6: Tent as an ‘Urban Room’ at the Kumbh

The following chapter describes the tent typology at the Kumbh Mela and its use for various purposes. It portrays the material and affective nature of the tents by describing various performances by folk groups that take place inside these ‘urban rooms.’

Makeshift structures are built globally to accommodate religious and secular gatherings, occupational activities, housing and other temporary purposes. Such spatial practices are culturally embedded in many societies, particularly Southern and have become a part of their everyday. However, as explained in Chapter 2, it is important to reposition these urban practices in a geographical and cultural context. Squatting as a practice in India is associated with subaltern urbanization (Bhan, 2019). But in the case of Kumbh Mela, it is important to reframe this mode of practice as not only ‘associated with the marginalised’ (Bhan, 2019, p.643) but also with the State due to the transitory nature of the people, event and geography (See,Fig.6.1).

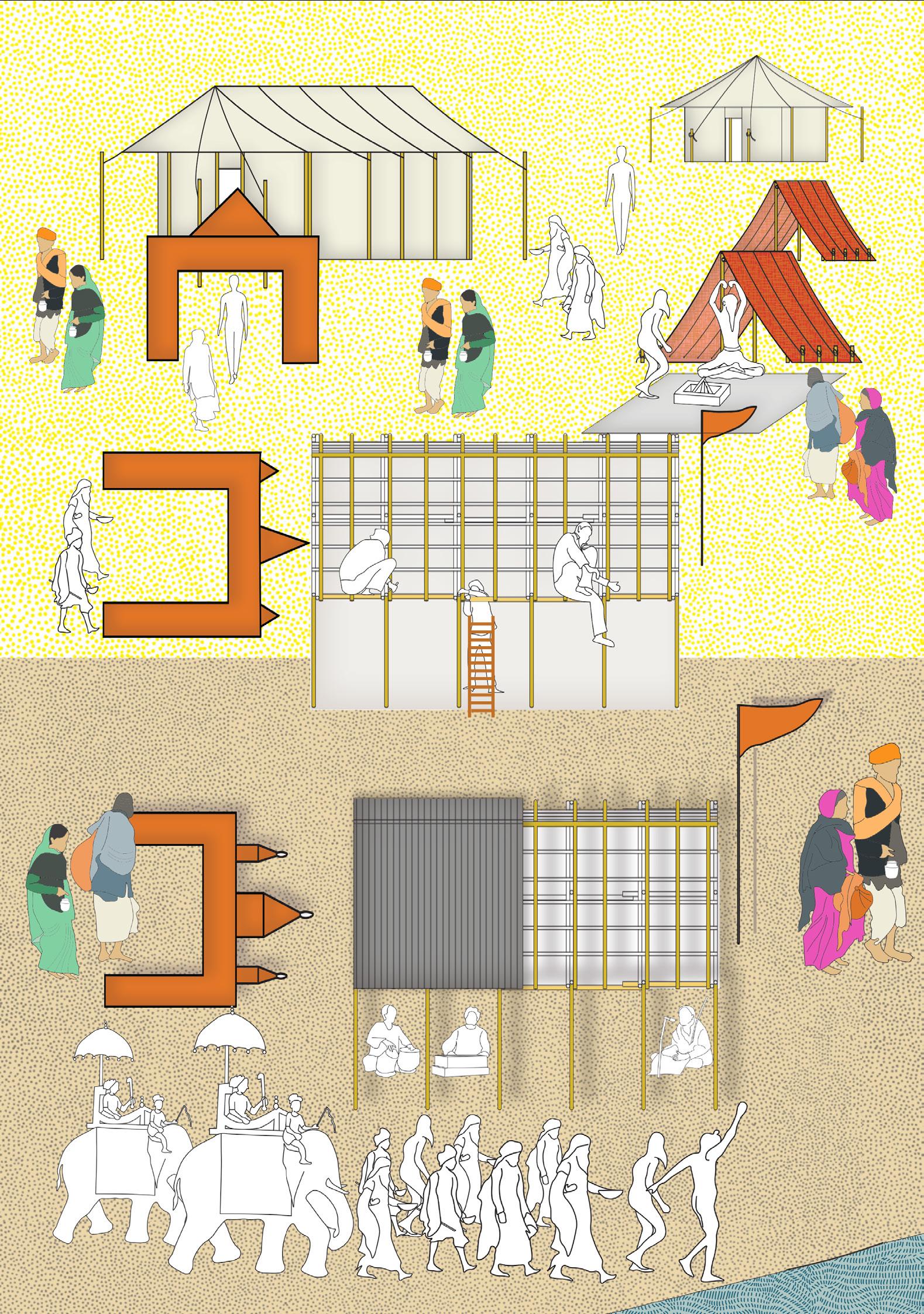

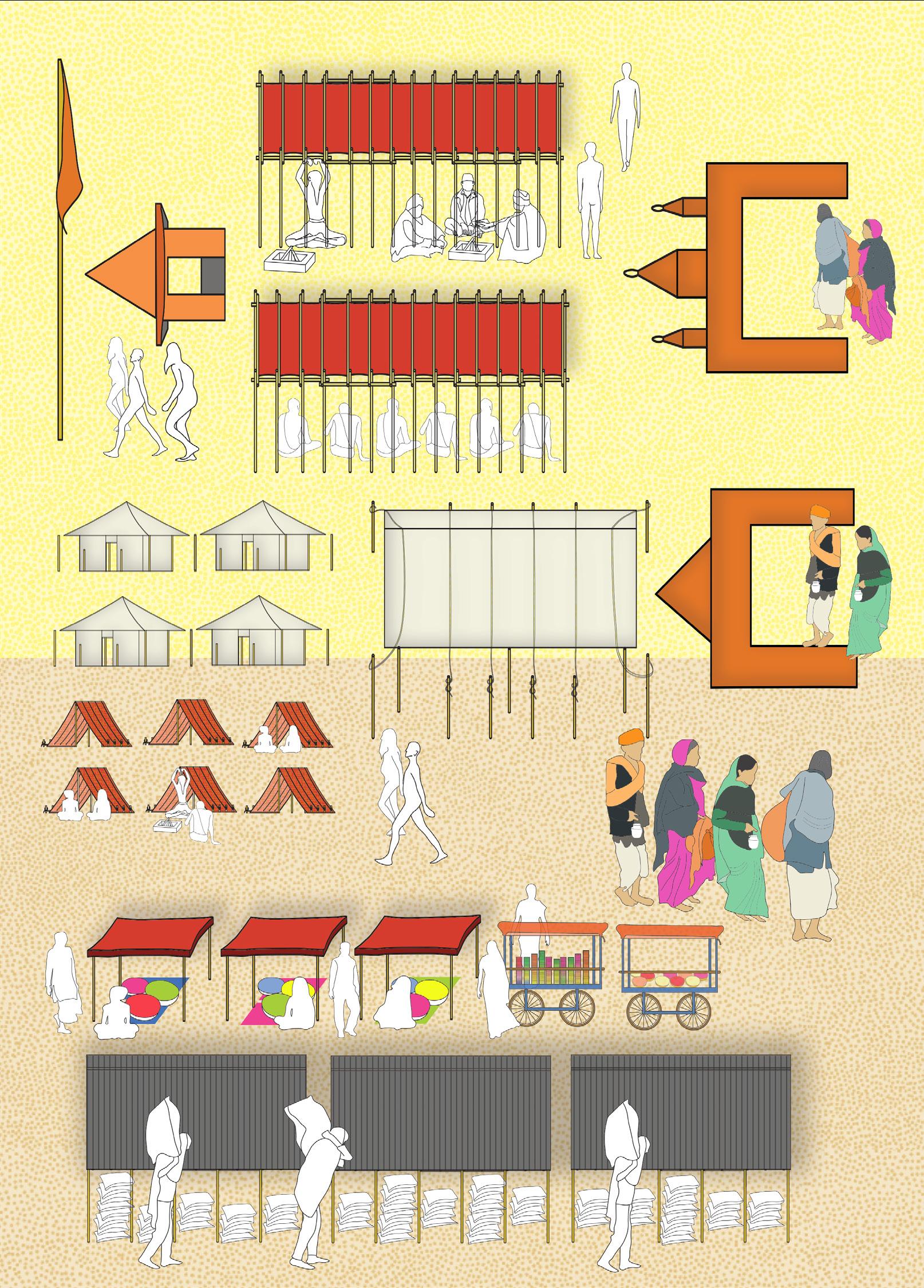

The site is divided into sectors with parcels of land allocated to each religious group who then organise themselves as per their requirements. There were eleven sectors in the 2001 Kumbh Mela which increased to fourteen in the 2013 event. The physical structure of the temporary city is made using elementary lightweight materials like bamboo and ropes (See, Fig.6.2). The assembly of the city and its subsequent disassembly is therefore an efficient process. These ‘material technologies’ (Mehrotra et al., 2015, p.86) of the settlement make it easier for the administration and the local labour to build ancillary services within a specific period. The tents made for this event are multi-scalar units. They are used for various purposes besides sleeping like performing religious rituals, congregating people for religious discourses and cultural events and hospitals interspersed by public toilets (Mehrotra et al., 2015, p.278) (See, Fig.6.3,6.4,6.5). There are open spaces in each akhara (ascetic camp) which are appropriated by people who do not have tents for sleeping.

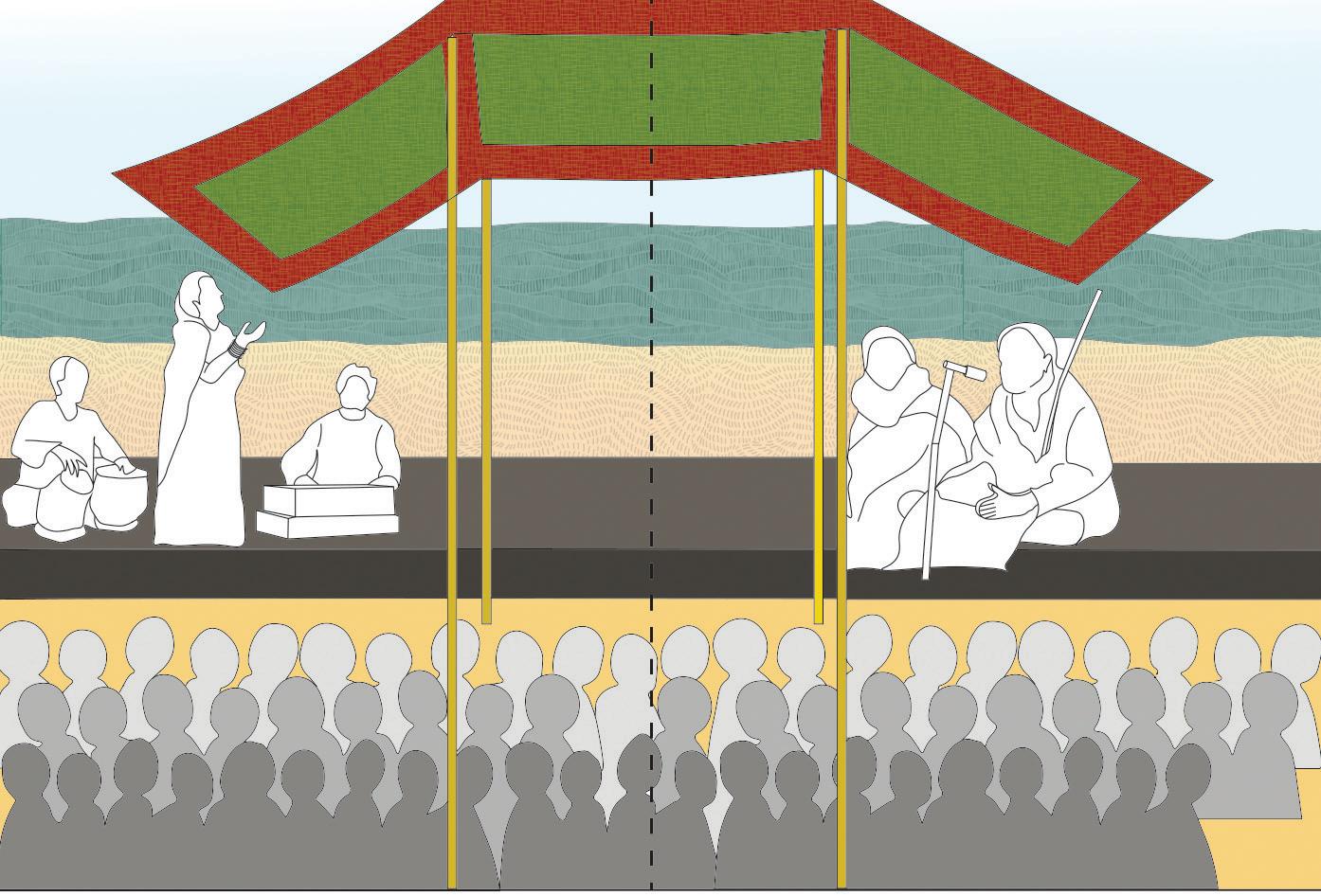

Religious stories and narrative folksongs are often performed in several larger tents during the Kumbh. They host performances of the kathavachaks (narrators) and dramatization of the folklore associated with the Kumbh Mela. These temporal theatres have audiences who perceive the actors as deities for the duration of the performance. It is a collision of two worlds – the world of an actor and the world of a spectator within an intimate space (Cohen, 1991, p.157). Dynamic relations are not formed due to ‘spatial proximity but because of common properties,’ (Awan, 2017, p.35) in this instance common sentiments and values. Shared faith among the pilgrims and ascetics forms the basis of the Kumbh. Today, there are larger marquees built to accommodate more people turning an intimate personal experience into a public fair. Another type of performance by folk artists from various parts of the country takes place in common open spaces.

The themes of these songs range from sanitation and health to river pollution. These performances by various folk groups are not always divorced from everyday realities and societal issues.

The material and affective nature of the tents as ‘urban rooms’ promotes the essence of the event. The transient language of the festival ‘strays from the orthodox approaches that are heavily grounded in time, rather than space’ (Mehrotra et al., 2015, p.86).

The structure of the festival challenges the codified meanings of spaces in permanent cities and questions their inability to reappropriate and regenerate urban forms. Using the festival as a study, this research questions the standard and flattened mapping practices applied to such temporal and in-between cities thereby neglecting the continuous re-territorialization of the site.

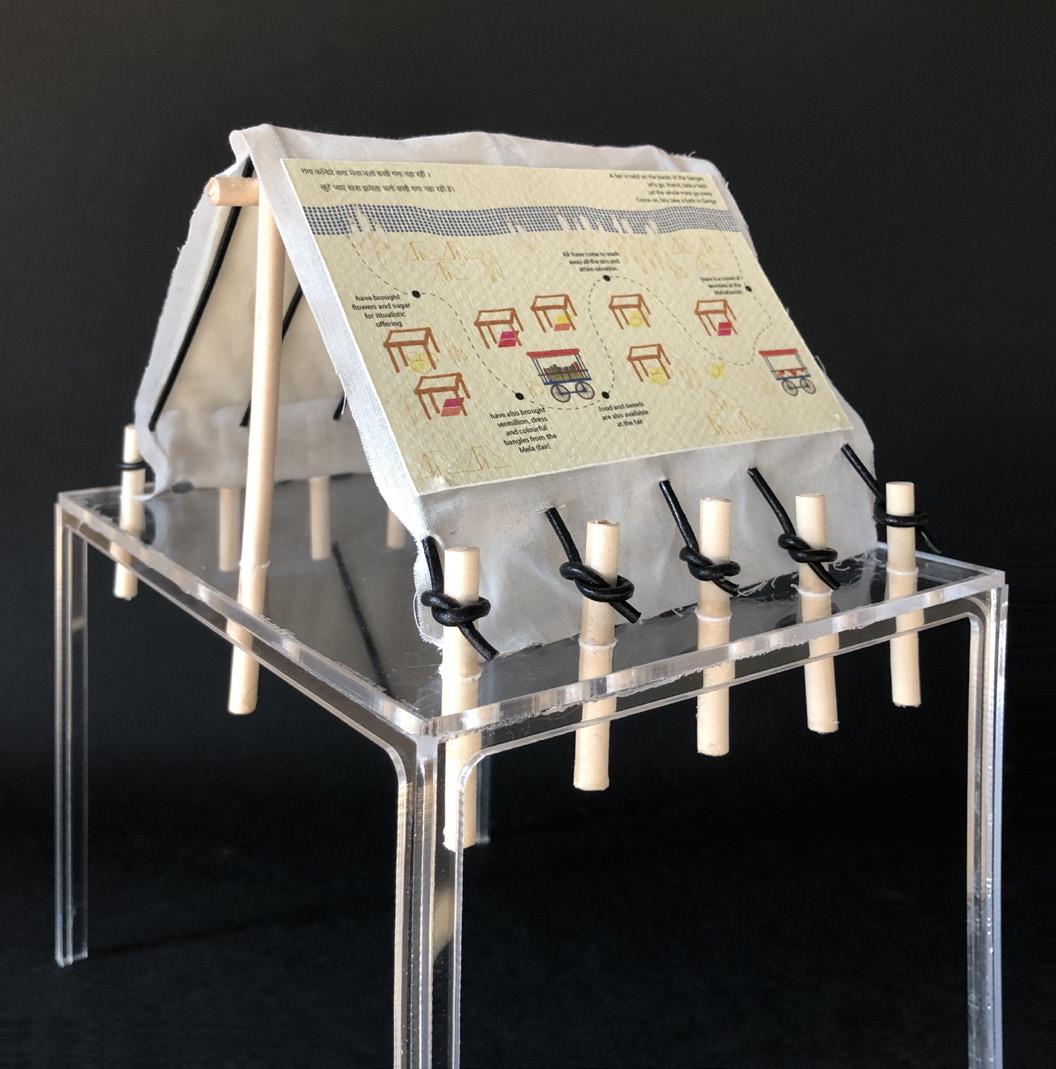

Fig.6.1: Aerial View of the Tent-city Source : Government of Uttar Pradesh, https://prayagraj.nic.in/tourist-place/sangam/The purpose of making a model of a tent was to abstract the material light-weightedness of the site. It was also to demonstrate the tent as a spatial unit that can be easily assembled and disassembled.

The deployment activity of materials and resources creates another layer of uniqueness of this temporal city.

Fig.6.3: Cooking Food inside a Tent

Source : PRESS, 2021

Fig.6.4: Performing rituals such as fire oblation in the tent

Source : Vadim Kulikov as cited by Mehrotra, 2015

Fig.6.5: A kalpavasi praying inside his tent. An individual experience compared to a more communal event.

Source : PRESS, 2021

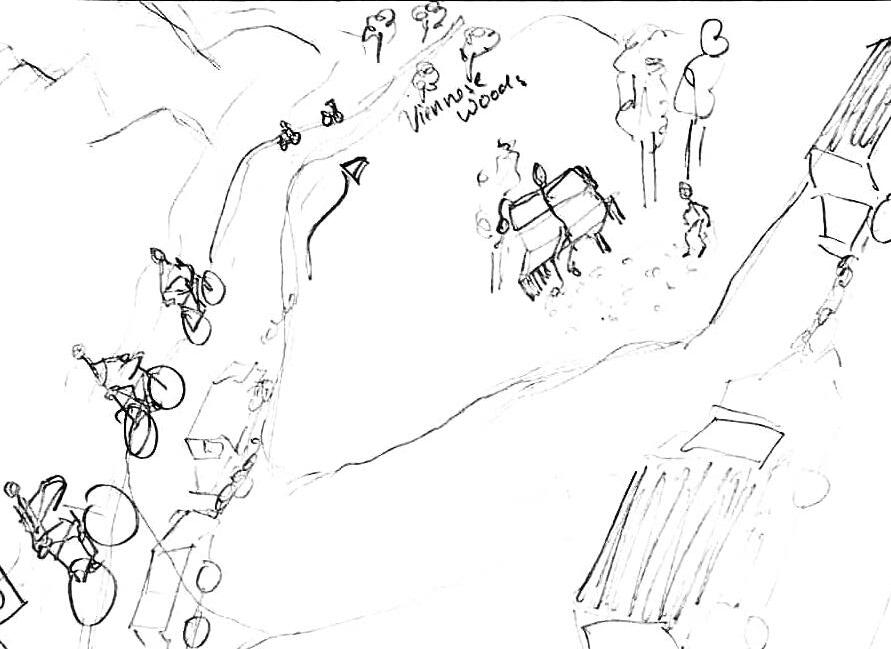

Fig.7.7 : Mapping as a processual activity, author

Fig.7.7 : Mapping as a processual activity, author

Plate 1: The beginning of a kalpavasi’s journey, author

Plate 2: The structure of different tents, author

Plate 1: The beginning of a kalpavasi’s journey, author

Plate 2: The structure of different tents, author

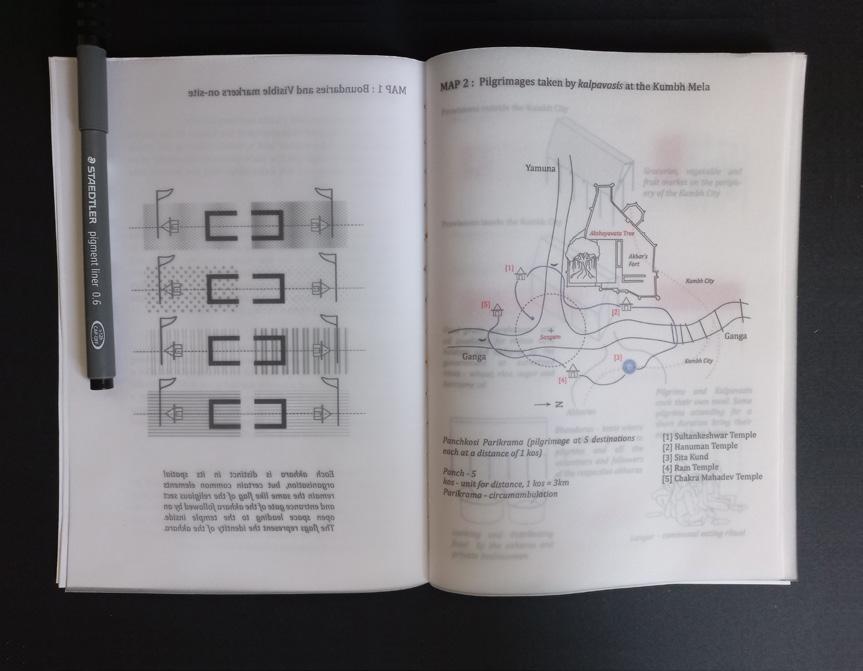

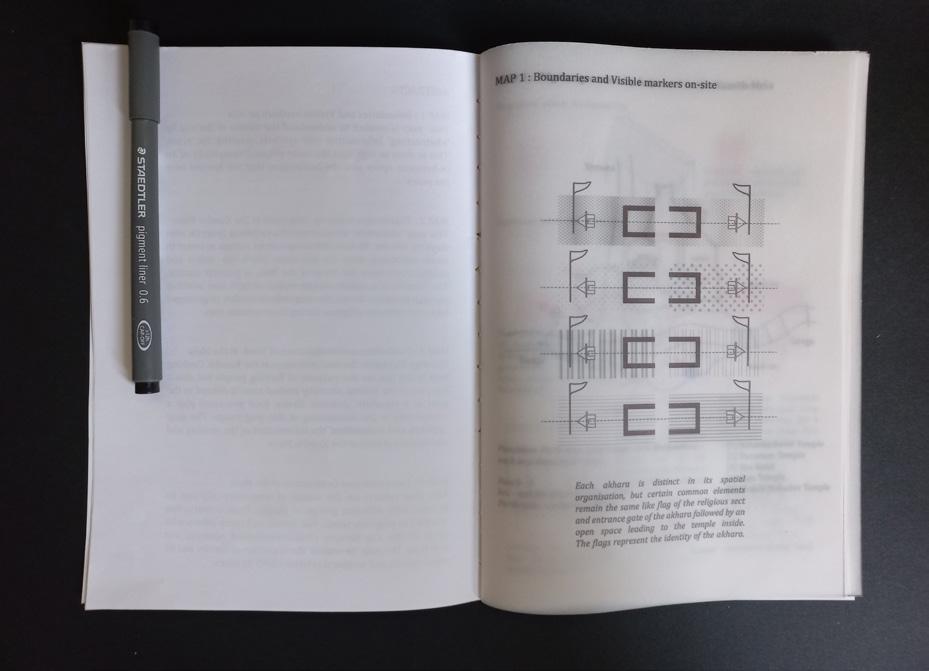

Fig.9.2 : MAP 1 : Boundaries and Visible markers on-site, author

Fig.9.3 : MAP 2 : Pilgrimages taken by kalpavasis at the Kumbh Mela, author

Fig.9.2 : MAP 1 : Boundaries and Visible markers on-site, author

Fig.9.3 : MAP 2 : Pilgrimages taken by kalpavasis at the Kumbh Mela, author

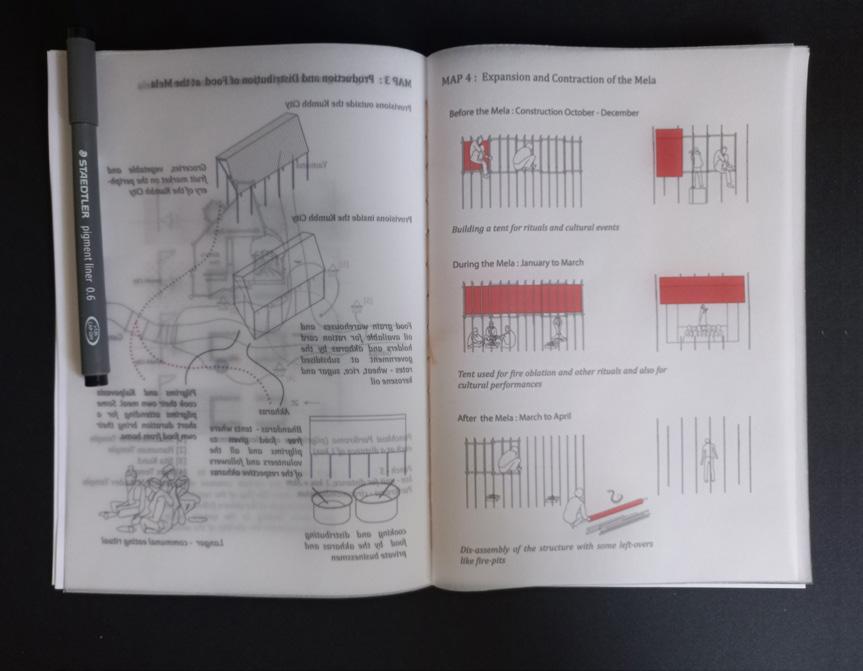

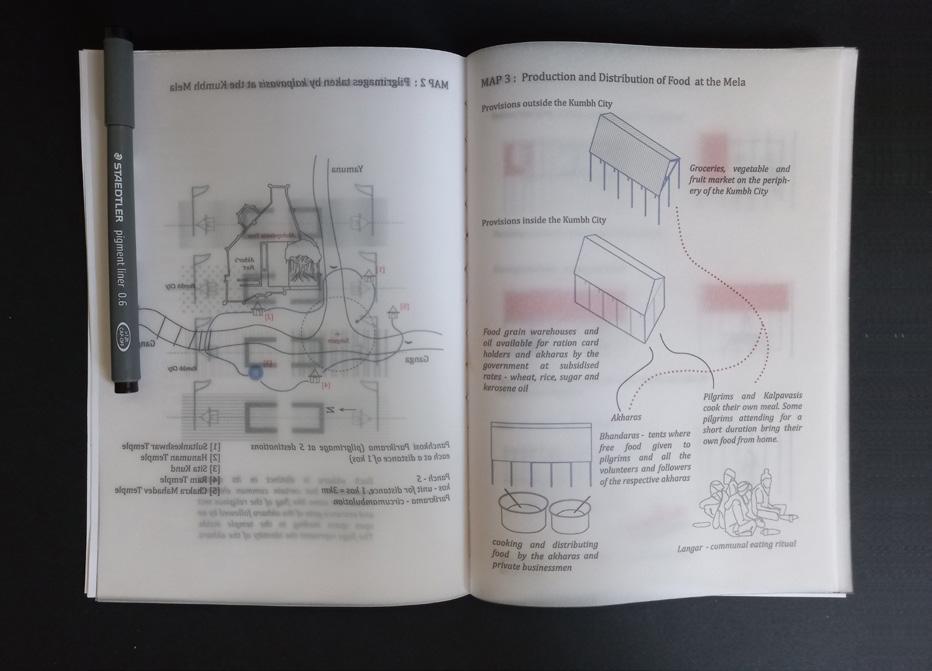

Fig.9.4 : MAP 3 : Production and Distribution of Food at the Mela, author

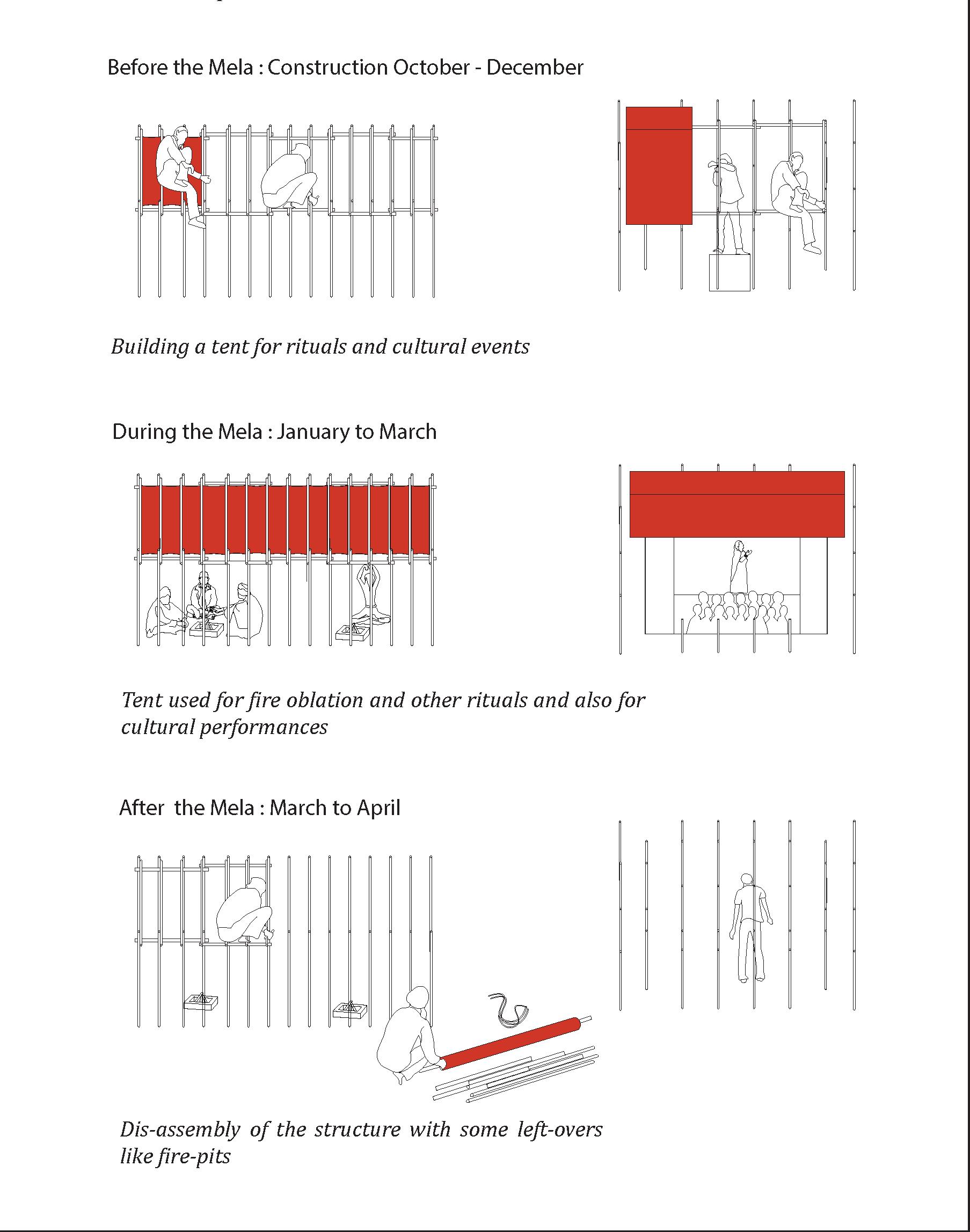

Fig.9.5 : MAP 4 : Expansion and Contraction of the Mela, author

Fig.9.4 : MAP 3 : Production and Distribution of Food at the Mela, author

Fig.9.5 : MAP 4 : Expansion and Contraction of the Mela, author

Fig.9.6: Images from the booklet, author

Fig.9.7: Mapping as a performance, author

Fig.9.6: Images from the booklet, author

Fig.9.7: Mapping as a performance, author

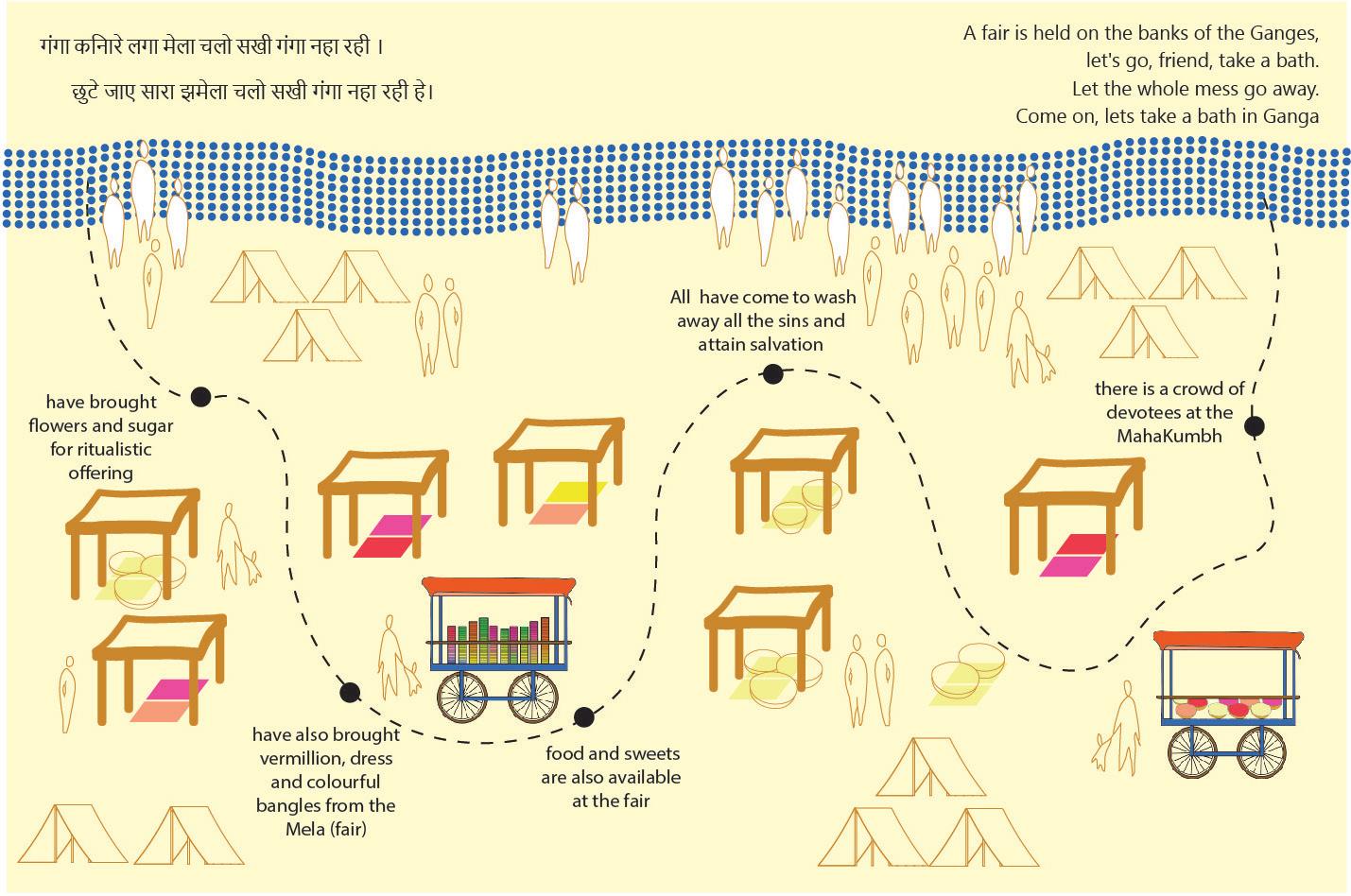

Fig.9.8 : Mapping a folk-song of Kumbh Mela, author

Fig.9.9 : Mapping different tent activites, author

Fig.9.8 : Mapping a folk-song of Kumbh Mela, author

Fig.9.9 : Mapping different tent activites, author