DALLAS + ARCHITECTURE + CULTURE Vol. 37 No.3

GLOBAL

2 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

AIA Dallas Columns Vol 37, No. 3

GLOBAL

Shelter, a fundamental need, is the basis of the built environment. Architecture fulfills this need and elevates it further, manifested in endless styles and solutions throughout the world. This diversity tells each community’s story of varied conditions, traditions, and ingenuity. What can we learn from this, and what can we share?

IMPORTING AND EXPORTING CULTURE

A NOTE FROM THE EDITORS: Like many nonprofit efforts, Columns has been impacted by the ongoing pandemic in myriad ways – shifting processes, increasing costs, and materials shortages among them. However, the volunteer nature of producing our magazine has unique challenges, and much of this content was produced in 2020 and 2021. We are issuing content as-is and look forward to new ways of delivering more timely content and memorializing the awards, projects, and people of AIA Dallas and our community as Columns enters its next evolution.

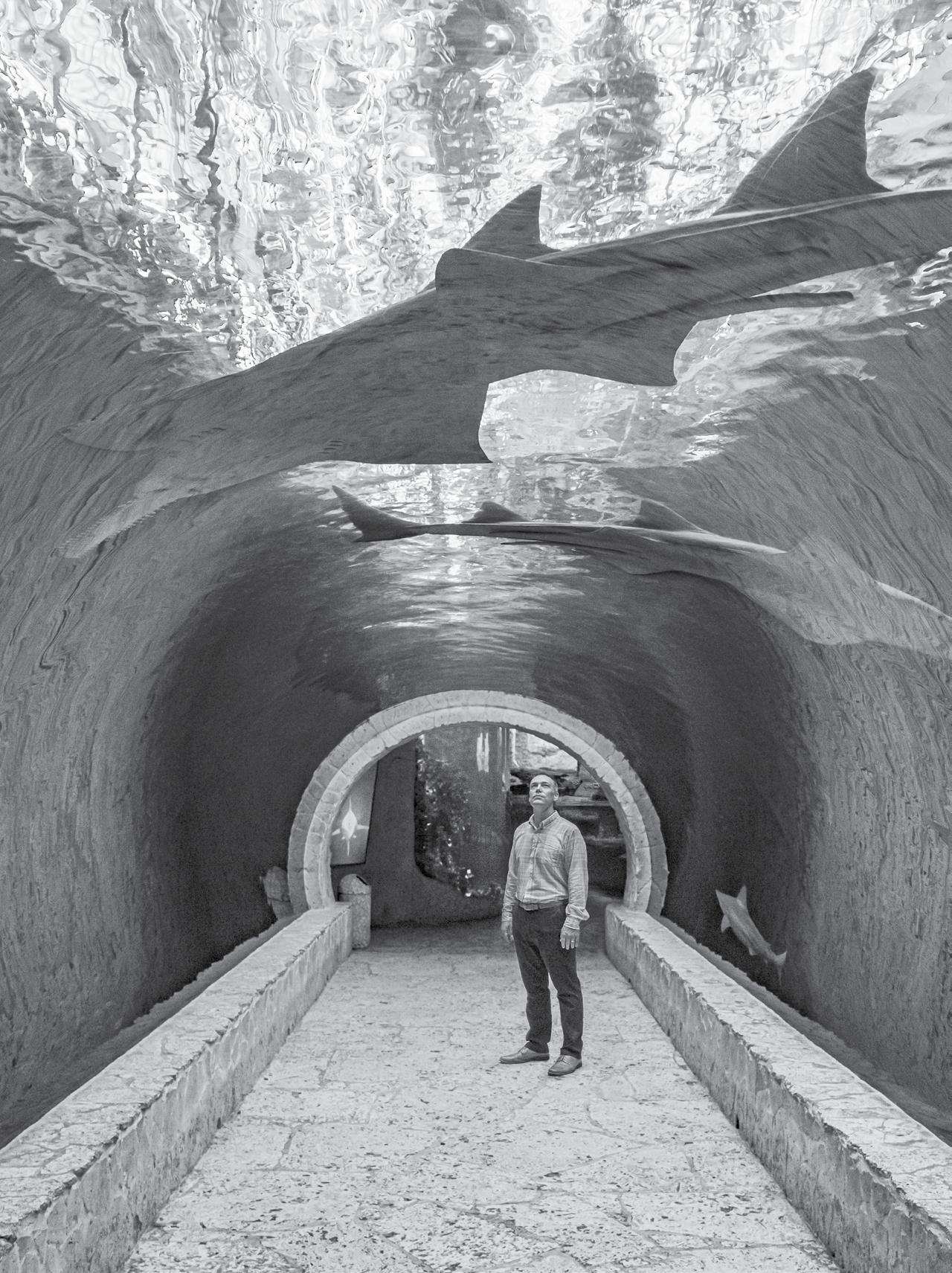

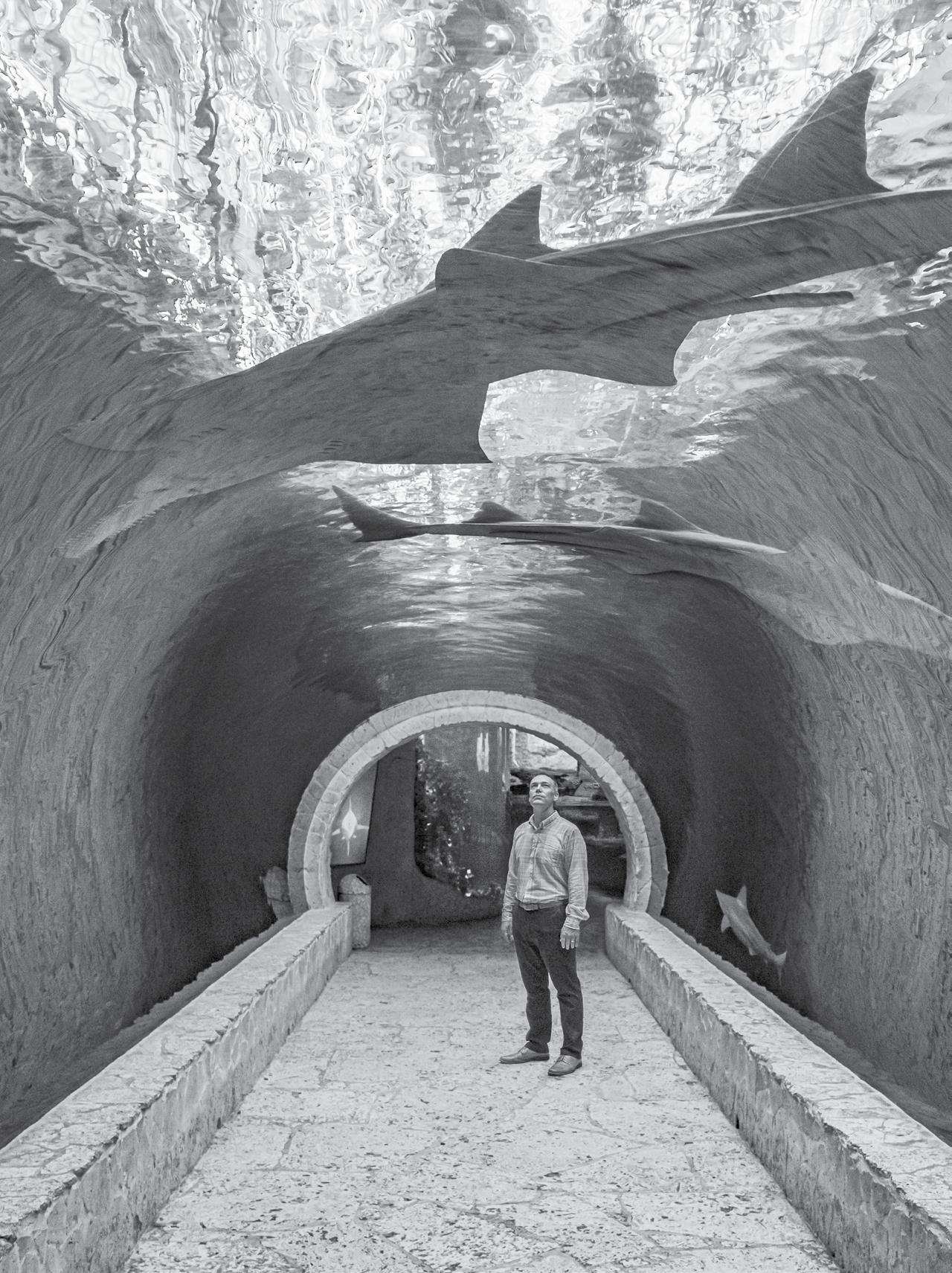

Cover Photography: Michael Cagle

ON THE COVER: Cory Dear, AIA stands beneath the shark tunnel in the lowest levels of the Dallas World Aquarium. Nestled within the West End Historic District — an early site of enterprise in what now is the global economy of Dallas-Fort Worth — the aquarium reflects the determination and imagination of our community. Here, a thoughtfully crafted open environment “rainforest” hosts an avian and animal collection of specimens from all over the world.

Texas Excels

Architects Win National Brick Design Awards

2 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

From the earth, for the earth.® LEED-accredited engineers and full-service support Case Study Library See our case studies at brick.com/casestudy details, descriptions, and photography.

Best in Class Commercial St. Vincent Austin architects Lake|Flato Architects, San Antonio / Austin general contractor Sabre Commercial, Austin masonry contractor Parker Stone, Austin

Raise a flag for Texas architects and architecture recognized nationally in the Brick Industry Association’s "Brick in Architecture Awards." Creativity and command of brick’s wide palette of colors, shapes, and sizes were the keys to winning praise from an esteemed panel of jurors. Long-term life cycle value: long may it wave across the land in

time-honored brick buildings. Whether standing proud and beautiful from a past century or freshly receiving a top award today, projects with Acme Brick endure. Architects rely on our range of options and experienced, responsive representatives—from concept through construction to owner satisfaction and award recognition.

3 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

Chad M. Davis, AIA

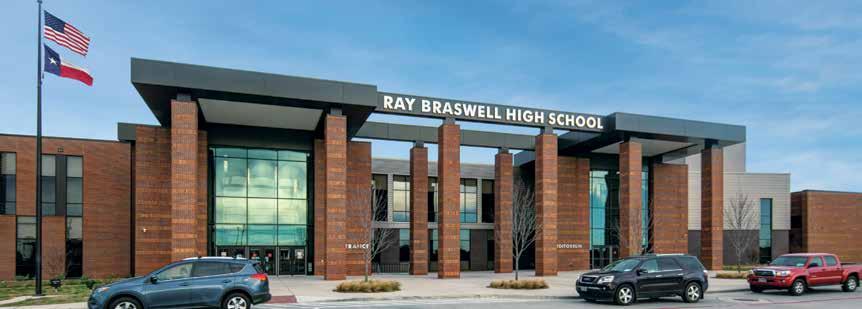

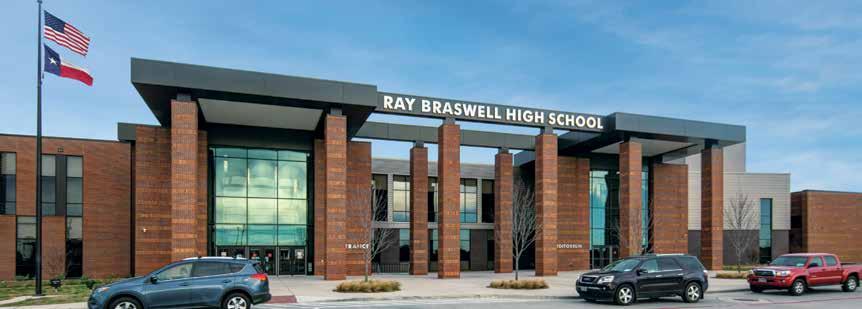

Gold Education K–12

Ray Braswell High School Denton ISD architects VLK Architects, Fort Worth general contractor Balfour Beatty US masonry contractor DMG Masonry, Arlington

Silver Education K–12

University Park Elementary School architects Stantec, Dallas general contractor Balfour Beatty, Dallas masonry contractor Skinner Masonry, Mesquite

4 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org @MLINTERIORSTEXAS MODERNLUXURYINTERIORS.COM BY THE PUBLISHERS OF HOUSTON AND MODERN LUXURY DALLAS MAGAZINES HAUTE LIVING COVETABLE COLLECTIONS, SHOWROOM UPDATES & PROPERTIES APLENTY DESTINATION WOODLANDS WHAT’S NEW & NOW SKY-HIGH SANCTUARIES TRANSFORM YOUR HOME INTO THE ULTIMATE OASIS HOME FRONT THE MOST SERENE ABODES TO SNATCH UP NOW FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF MODERN LUXURY DALLAS Look for the current issue of Texas’ leading luxury design magazine on newsstands now. TO ADVERTISE IN THE NEXT ISSUE CONTACT PUBLISHER HEATHER NOLAND | HNOLAND@MODERNLUXURY.COM EXPLORE THE DIGITAL EDITION AND SUBSCRIBE TO THE PUBLICATION AT MODERNLUXURYINTERIORS.COM/TEXAS MODERNLUXURY.INTERIORSTEXAS @MLINTERIORSTEXAS

A publication of AIA Dallas with the Architecture and Design Foundation

325 N. St. Paul Street, Suite 150 Dallas, TX 75201 214.742.3242

www.aiadallas.org

www.dallasadex.org

AIA Dallas Columns Vol. 37, No. 3

Editorial Team

James Adams, AIA | Editor in Chief

Katie Hitt, Assoc. AIA | Managing Editor

Jenny Thomason, AIA | Editor

Julien Meyrat, AIA | Editor

Lisa Lamkin, FAIA | Editor

Frances Yllana | Design Director

Linda Stallard Johnson | Copy Editor

Blanks Printing | Printer

Columns Committee

Luke Archer, AIA

Ashlie Bird, Assoc. AIA

Lisa Casey, ASLA

Cayce Davis

Nate Eudaly, Hon. AIA Dallas

Eric Gonzales, AIA

Unmesh Kelkar, Assoc. AIA

Alison Leonard, AIA

Alexis McKinney, AIA

Ricardo Munoz, AIA

Terry Odis

David Preziosi, FAICP

Ben Reavis, AIA

Sarah Schleuning

Janah St. Luce, AIA

Columns Advisory Board

Jon Altschuler

Paul Dennehy, AIA

Steven Fitzpatrick, AIA

Bradley Fritz, AIA

Rachel Hardaway

Vince Hunter

Patricia Magadini, AIA

Nancy McCoy, FAIA

Yen Ong, AIA

Lucilio Pena

Anna Procter, Hon. AIA Dallas

Meloni Raney, AIA

Leslie Reed Nunn

Gerry Renaud, AIA

Evan Sheets

Ron Stelmarski, FAIA

Brandon Stewart, AIA

Dylan Stewart, ASLA

Lily Weiss

Jennifer Workman, AIA

COLUMNS’ MISSION

The mission of Columns is to explore community, culture, and lives through the impact of architecture.

ABOUT COLUMNS

Columns is a publication produced by the Dallas Chapter of the American Institute of Architects with the Architecture and Design Foundation. The publication offers educated and thought-provoking opinions to stimulate new ideas and advance the impact of architecture. It also provides commentary on architecture and design within the communities in the greater North Texas region. Send editorial inquiries to columns@aiadallas.org.

TO ADVERTISE IN COLUMNS

Contact Jody Cranford, 800-818-0289 or jcranford@aiadallas.org.

The opinions expressed herein or the representations made by advertisers, including copyrights and warranties, are not those of AIA Dallas or the Architecture and Design Foundation officers or the editors of Columns unless expressly stated otherwise.

©2021 The American Institute of Architects Dallas Chapter. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited.

2022 AIA Dallas Officers

Ben Crawford, AIA | President

Kate Aoki, AIA | President-Elect

Charles Brant, AIA | VP Treasurer

Peter Darby, AIA | VP Programs

AIA Dallas and Architecture and Design Foundation Staff

Zaida Basora, FAIA | Executive Director

Conleigh Bauer | Membership Manager

Cathy Boldt | Professional Development Manager

Cristina Fitzgerald | Operations Director

Preston Fitzgerald | AD EX Coordinator

Rebecca Guillen | Program Coordinator

Katie Hitt, Assoc. AIA | AD EX Managing Director

Elizabeth Jones, Assoc. AIA | Marketing Manager

Liane Swanson | Marketing Coordinator

7 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org Experience, Quality, and Reliability 214.357.0300 StazOnRoof.com C elebrating oldnerlighting.com

IN THIS ISSUE - GLOBAL

8 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

13 EDITOR’S NOTE 25 IN CONTEXT What is it? Where is it? 35 DIALOGUE A Walk in the Parks: Design strategies for an increasingly outdoors community 39 LOST + FOUND The Magnolia Lounge: Dallas showcases the International Style 42 DETAIL MATTERS Details of Dilbeck 45 PUBLIC ARTS A structural expressionism homage to Bryan Tower 46 DIALOGUE Perspectives on migrating to Dallas from abroad 50 PROFILE Dan Noble, FAIA, president and CEO of HKS 52 POINT/COUNTERPOINT Dallas architecture: Does it exist and who should be designing it? 55 GALLERY Built Design Awards 60 STORYTELLING Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses 62 INDEX TO ADVERTISERS 65 LAST PAGE The Leaning Tower of Dallas

14

All the world’s a stage. Dallas, what’s your role? 17 Architectural Fuel The boom, bust, and beyond of Dallas in the ‘80s 20 The Thin Red Line How fire lanes shape our modern cities 26 The Emotional Impact of Safety Balancing technology and psychology in design innovation 30 The New Age of Security Technology in a post-pandemic world READ COLUMNS ON THE GO: WEB aiadallas.org/v/columns-magazine FLIPBOOK MAGAZINE issuu.com/aiadallas Download the Issuu app for your iPhone/Android

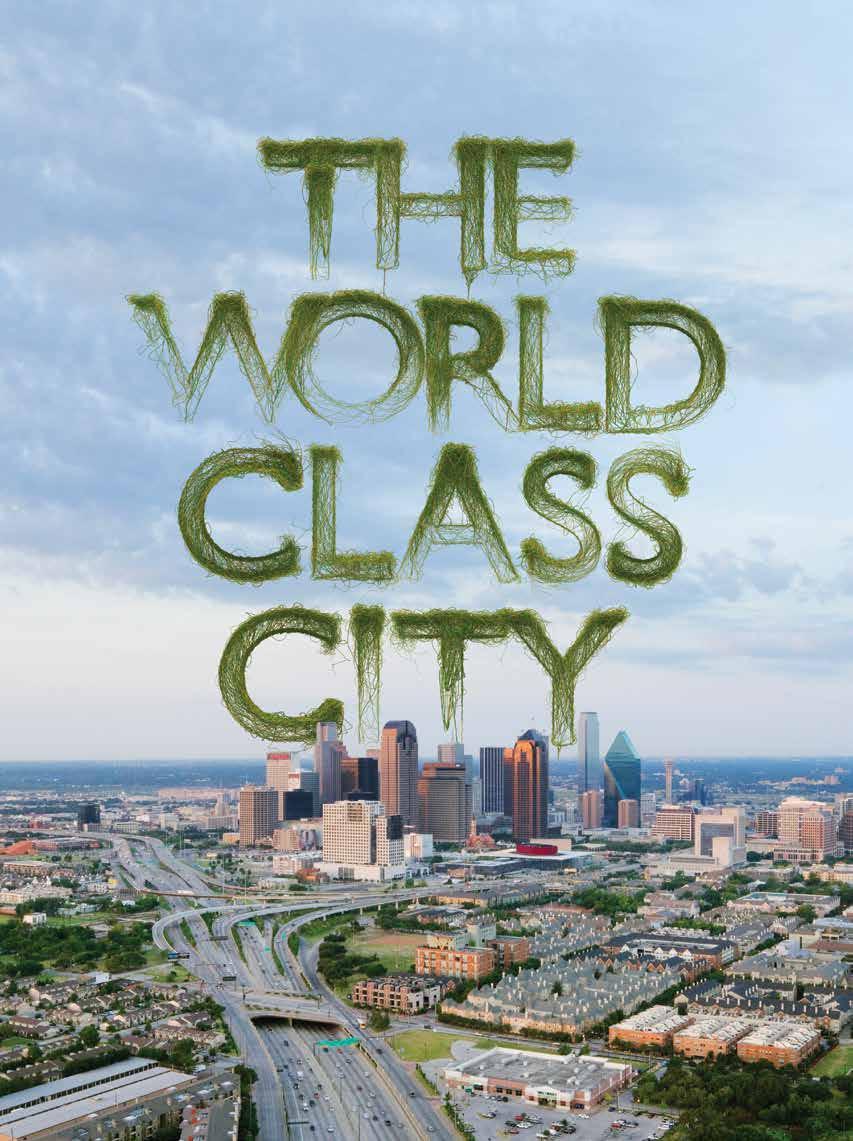

Photo:: Menary Studio

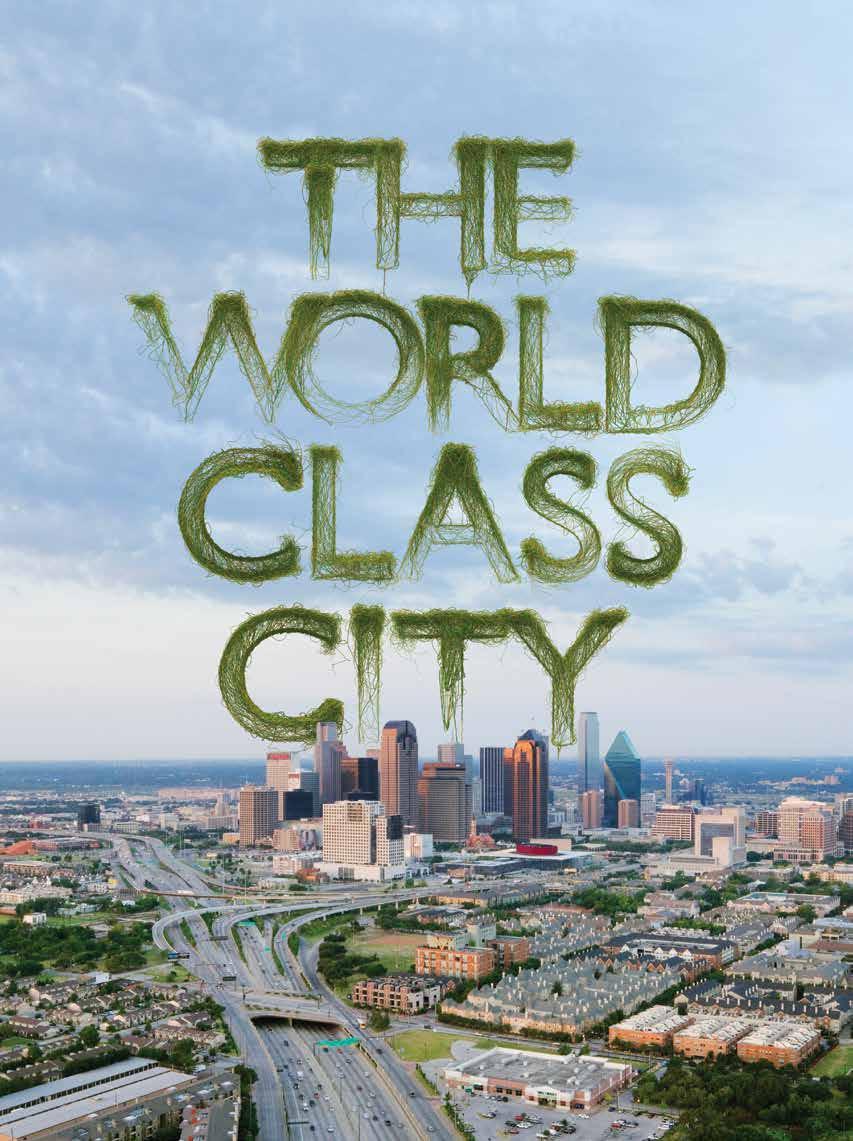

The World Class City

CONTRIBUTORS

Samantha Flores, AIA, NCARB, RID

Samantha is the director of HUGO, a research and innovation team at Corgan that identifies technology disrupters and shifts in human behavior. HUGO examines the various impacts these innovations will have on the user experience and built environment through focused research and experimentation. Prior to HUGO, Samantha spent six years as an architect and experiential design specialist in aviation architecture.

Lance Josal, FAIA

After nearly two decades in the C-suite and 40 years in professional practice, Lance established 11AD to provide executivelevel advice to A/E firms interested in strengthening the health of their businesses. A strong and skillful leader, Lance played an integral role in guiding CallisonRTKL’s expansion into new and emerging markets. He served as the firm’s president and CEO from 2009 to 2019.

Alison Leonard, AIA, EDAC

Originally from upstate New York, Alison holds an architecture degree from Roger Williams University in Rhode Island. She is a licensed architect and certified evidence-based designer. A nationally recognized leader in behavioral healthcare planning and design, she is associate vice president at CannonDesign in Dallas. When not working, she is most likely outside with her husband, toddler son, and French bulldog.

Thom McKay

Thom is a creative, collaborative, strategic marketing, and communications professional who has been working in the A/E/C industry for more than three decades. He was corporate marketing and communications officer of CallisonRTKL, the global architecture, design and planning practice. He is a frequent author, ghost writer, and speaker on marketing and design.

Gavin Newman

A native of Mesquite, Gavin learned architecture and placemaking at Tulane University in New Orleans. Now back home, he is a project coordinator at GFF, contributing to mixed-use housing, site planning, and master planning.

David Whitley, Assoc. AIA

David, a graduate of the University of Texas and Cornell University, owns DRW Planning Studio, a Dallas-based urban planning firm. He has over 20 years of urban planning and design experience, with a background in public policy and developmentrelated disciplines. He lives in East Dallas with his wife, two daughters, and lazy dog.

DEPARTMENT CONTRIBUTORS

Seth Atwell, ASLA Public Arts

Henry Dalton, ASLA Public Arts

Douglas Dover Profile, Storytelling

Nate Eudaly, Hon. AIA Dallas Dialogues

Nancy McCoy, FAIA, FAPT Lost & Found

Patrick Nedley Point/Counterpoint

Anna Procter, Hon. AIA Dallas Last Page

Shahad Sadeq, Assoc. AIA In Context

Janet Spees, Assoc. AIA Detail Matters

9 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

10 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org LANDSCAPE DESIGN | CONSTRUCTION | POOL CONSTRUCTION GARDEN CARE | POOL CARE AND SERVICE | COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS Start your dream today | 972.243.9673 DESIGN | CONSTRUCT | MAINTAIN bonicklandscaping.com Bonick created a truly serene place of beauty and harmony with nature where we can disconnect, reflect and restore the balance in our lives.” Julie and Eliot DECADENT DREAMS DWELL AT HOME “ ELEVATE YOUR OUTDOOR ESCAPE ________

11 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org METRO B R I C K + S T O N E m e t r o b r i c k . c o m 9 7 2 .9 9 1 . 4 4 8 8

12 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

EDITOR’S NOTE The Global Village

When the world began to lock down in the spring of 2020, the ease of communication through technology remained. This also reinforced the notion that we are a global village in many ways even when we don’t act like it.

The less desirable human tendencies reinforced xenophobia, alienation, prejudice, and selfishness. While these are not new problems, they have the ability to spread more rampantly in the meme age of social media.

However, the pandemic also challenged us to become more resourceful and resilient. It has given us the opportunity to listen and learn from our neighbors. A village must rally its people to work together in recognition of their strengths and despite their weaknesses.

A community’s architectural vernacular demonstrates what makes it special. Architects have a responsibility to understand the stylistic influences of a region in their design; they can also mimic solutions from afar resulting in better built environments.

In this issue of Columns, we explore the role of North Texas in a global community and the impacts architects can have locally and afar. The topics range from unpacking Dallas’ desire to be a world-class city to examining the evolution and impact of fire lanes on modern city development. The

magazine also explores the subject of security through thought pieces on the emotional impact of safety and the role of technology in a post-pandemic world.

In Dialogues we delve into the role of local and remote architects in shaping Dallas and the perspective of architects who have migrated to Big D from other parts of the world. We also profile Dan Noble, FAIA, chief executive of HKS Inc., one of the world’s largest global architectural practices.

We hope you find value as you read through the content. As always, we welcome your feedback.

James Adams, AIA Editor in Chief james.adams@corgan.com

James Adams, AIA Editor in Chief james.adams@corgan.com

13 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

Photo: Kurt Griesbach

“There are no passengers on spaceship Earth. We are all crew.”

Marshall McLuhan

By David Whitley, Assoc. AIA

ALL THE WORLD’S A STAGE. DALLAS, WHAT’S YOUR ROLE?

To many, the term global city conjures up images of diverse, cosmopolitan hubs of activity and commerce — the important places on the world stage that are key connecting points of trade and culture. Without these cities, links in the international economic system break down, gears grind inefficiently, and our collective economic well-being degrades. That’s not to mention the color of our world would be dulled without these repositories of culture.

To be a global city is to be inextricably and integrally tied to the well-being of our planet, to be a crucial part of what makes world societies hum, and to define the tenets of our existence as a civilization. Clearly, achieving this status is no small feat, nor is holding this status a small responsibility.

The Brookings Institution, a renowned public policy think tank, launched its Global Cities Initiative in 2011 in partnership with JP Morgan Chase. This effort seeks to help cities and metropolitan areas to more effectively hang their shingle in the global marketplace. These experts outline guidance on how to distinguish yourself in the world market, define your competitive advantages, and maximize the benefit to your local economy.

A quick assessment of Dallas’ advantages yields a treasure trove of assets put into place over several generations. Step back and take them in as a collective portfolio, it is clear that the tracks laid for Dallas and our region over the generations have led to a pretty direct path to becoming a global city.

As Dallas jetted up the ranks of large American cities in the last part of the 20th century, it began to nudge into queue as a global center. But the groundwork was laid in the early 1870s, when a series of deft decisions and a little cajoling by city leaders resulted in Dallas being at the convergence of railroad lines. The primary north-south and east-west rail lines through the state — the Houston & Central Railway (now Union Pacific) and the Texas-Pacific Railway — crossed each other in Dallas, solidifying the city’s place as a hub for commerce.

This was essential because most bustling metropolises relied upon port access as points of origin for their commerce. Being landlocked, Dallas needed intersecting railroads as an inland tactical advantage to get itself on the map. In 1914, Dallas won another major coup by landing the headquarters of the 11th Federal Reserve District, wrangling it away from clear favorite New Orleans. Dallas’ banking and finance industry were in growth mode, whereas NOLA was on cruise control. The choice to place the Fed in Dallas ensured the city’s place as a financial center for generations and served as another asset driving growth and development in the region.

By the middle decades of the 20th century, America shifted its focus on transportation infrastructure to the development of an interstate highway system. The region successfully attracted strategic infrastructure investment, and today may be the only metro in the nation with four interstate highways

crisscrossing the region, providing multiple direct connections to trade throughout the continent.

By 1974, the city turned its eyes to the sky and joined with Fort Worth to build Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. This milestone was decades in the making, going back to the early 1920s. Today, DFW has routes to nearly 260 domestic and international destinations. The annual economic benefit to the region is in the tens of billions of dollars, plus an untold benefit in corporate relocations.

Investment in the Inland Port in the southern reaches of Dallas has continued to boost the region’s logistical advantages. To understand the scale and economic benefit to the area, just look at the line of trucks emblazoned with the Amazon logo stacked up on the Interstate 20 service road in southern Dallas. The Inland Port is a continuation of a series of investments taking advantage of the city’s central location in the country.

Many generations of arm wrestling squeezed out more than our share of growth to become the roaring bastion of commerce springing from the Blackland Prairie of Texas. The sheer size of the population and economy has grown into a metropolitan area that is certainly global in scale and has a gravitational pull that continues to attract growth and investment. According to the North Central Texas Council of Governments, the population of Dallas-Fort Worth is about 7.5 million, making it larger than 37 states, including nearby Louisiana, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arkansas.

Dallas-Fort Worth makes up 30 percent of the Texas economy at 4.8 million jobs. By 2045, the North Central Texas Council of Governments forecasts, the region will have 11.2 million people and 7 million jobs. The metro’s GDP in 2018 was nearly $470 billion. This would outrank all but 26 or so countries in the world.

So here we are. These data tell us that we have pulled ourselves up onto the global stage, and we are not likely to be knocked off anytime soon. However, we cannot rest on the laurels of the many advantages that our region has accumulated over the generations. We cannot expect to maintain our position in the world without continued effort.

So now what? How will we use this platform not only for our benefit, but for the benefit of others? Like those generations that came before us, are we going to lay groundwork for the generations to come? The way in which our political and corporate systems address these questions will serve as

15 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

leverage to keep us climbing up the ranks of global cities not only as an economic engine, but also as an engine for cultural innovation and equitable opportunities.

Dallas has reached a stage where it needs to be “full of wise saws and modern instances,” to pull from Shakespeare. Dallas can position itself as a leader that balances experience with innovation to improve justice and equity among its population. In driving our economic strength forward as a global city, we cannot focus only on the next big thing, but also on economic access at the individual level. By stretching our aspirations to not only the overly ambitious and borderline impossible projects, but to enable the very least of us to have opportunities, we can provide an egalitarian example of what a global city should be. And where the economic data are not only measured in the billions of dollars, but also at the level of balancing a monthly household budget.

There is a clear sense that the trajectory of today’s civic policies is to broaden the perspective through which we make public investment decisions. Single purpose investments are inefficient and ineffective at truly addressing public needs. Public expenditures should be graded and prioritized by their performance across a broad spectrum of criteria to ensure that the dollars are spent wisely and to the maximum benefit. Key plans and policies must not only pile on large-scale investments that increase our logistical advantages within the nation and among our peer cities to pay dividends for generations to come, but also to deepen the impact within our local communities.

The Connect Dallas: Strategic Mobility Plan developed by the City of Dallas sifts transportation investment decisions based on how they perform under six key principles:

• Aligning with economic and workforce development goals.

• Supporting diversified and affordable housing options.

• Leveraging the innovation economy.

• Being kind to the environment.

• Improving equitable access to jobs, services, and opportunities.

• Improving safety for all transportation modes. Transportation metrics are no longer solely about minutes of delay and level of service. Looking at transportation investment through this broader lens, a different picture

emerges of how we should approach infrastructure development over the next generation. The small-scale project that solves how best to connect individuals to grocery stores and jobs by foot or by bike ranks well against the major investments that have regional or national implications. Better yet, it pushes us to pursue projects that do both. An example: How can the Inland Port immediately benefit its surrounding community? How can streetscapes in the Medical District be reformatted to improve public and environmental health?

The freshly minted Comprehensive Environmental and Climate Action Plan developed by the City of Dallas also holds equity and inclusion as core values. Poor air quality and other environmental challenges disproportionately affect vulnerable communities within our city that are least able to battle these detrimental conditions. Further, the linkages of the environment, equity, access to sustainable transportation options, and improving public health underpin the goals and objectives of the plan. Addressing our city’s environmental challenges also means addressing our city’s social and economic challenges.

As we approach the middle of the 21st century, how can we think broadly and demand comprehensive, inclusive approaches to shaping our city through thoughtful and equitable planning and investment? Looking at the horizon, how can we address the challenges to maintaining our global relevance? As we plan for the future, our expectations will and should change. It is not about how we will keep up as a city, but how we will lead.

As a global city, we have a responsibility to chart the course for others to follow. Today’s decisions and investments should advance an agenda that is increasingly ambitious on multiple levels. Are we making Dallas a more just and equitable city? Are we making Dallas a more sustainable city? Are we making Dallas a more innovative city? If we continually ask ourselves these questions and critically reflect on the progress, the answer to whether Dallas is a global city will take care of itself — or may even be irrelevant.

16 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

David Whitley, Assoc. AIA is the owner of DRW Planning Studio.

Special thanks to Sandy Wesch from the North Central Texas Council of Governments who contributed her expertise to this article.

By Lance K. Josal, FAIA & Thom McKay

The 1980s were a heady time for Texas architects. The great titans of the industry — firms like HKS, CRS, and 3DI — were bustling at a pace not seen since the 1950s, thanks to a post-Vietnam economy fueled mostly by, well, the fuel industry. Dallas boomed and set the stage for the largest expansion, and international diaspora, of architecture practices the country had ever seen.

We had the great fortune to be among the many that surfed the crest of the wave, and it’s easy to draw parallels with what the industry faces in our peri-pandemic COVID-19 world.

First, a bit of background.

Throughout the 1970s, turmoil in the Middle East caused oil-dependent nations like the United States no small measure of political and economic discomfort. In 1979, OPEC reduced the flow of oil into North America, and suddenly the evening news was filled with images of Chevy Caprice station wagons lined up bumper to bumper at gas stations. Inflation and sky-rocketing energy costs sent the country, especially the Northeast and more industrial Upper Midwest, into malaise.

By the time of the coin flip of Super Bowl XIV in January 1980, the country was in a rough place. In Iran, a major oil producing nation, 52 American diplomats and citizens were being held hostage. Amid economic uncertainty, unemployment had begun creeping toward double digits. (It reached 10.8% in December 1982.) People found themselves out of work, including President Jimmy Carter.

But things were different in Texas. The price of crude went from $3.39 per barrel in 1970 to $37.42 in 1980, more than quintupling the bank account of anyone even remotely related to the oil industry. While the Sun Belt

saw unprecedented growth, Texas was by far the greatest beneficiary. Houston nearly doubled in size between 1970 and 1980. Early in the decade, Dallas added residents at a staggering clip of as many as 1,000 per month. Most of them were young, upwardly mobile, educated professionals — tagged yuppies — seeking affordable housing and the adrenaline rush of opportunity. They found it in Big D.

As the decade churned forward, Dallas rose from its stepchild position as “regional center” to seventh in the nation in corporate headquarters, fifth in total assets in commercial banks, fourth in airline passengers, and, by the end of the decade, the undisputed leader in commercial construction. Cranes filled the skyline, and it was hard to drive more than two blocks without encountering a construction barricade.

While all the construction noise was certainly music to the ears of every architect, developer, and contractor, it was the cultural and demographic shift that made the lasting impact on our industry. Dallas had lacked the sophistication of New York and Los Angeles, not to mention the architectural heritage of San Francisco or Chicago. But this influx of human capital and creative currency brought a welcomed swagger to the architectural community. And boy, did it need it.

Back then, the city had no architectural identity. Sure, Reunion Tower and Thanks-Giving Square had made an impact, but the skyline was empty and the drawing board felt barren. In the cover story of the May 1980 issue of D Magazine, David Dillon, then one of the few full-time architecture critics in the country, wondered, “Why is Dallas architecture so bad? … When Dallasites talked about their sublime skyline, it was more from wishful thinking than direct observation. Reunion and the Hyatt changed all that by giving the city a genuine landmark building, a civic symbol that expresses visually many of the things Dallasites like to think are true of the city as a whole.”

The influx of talent was the needed spark. Oil money fueled a pro-growth municipal mindset, and there was a great airport, plenty of land, bullish developers, and that young, burgeoning population moving toward the ambient heat of “what is bad for the rest of the nation turns out to be good for Texas.” Dallas boomed. And architects rejoiced.

RTKL opened a Dallas studio in 1979, and Lance Josal was the office’s first hire who did not relocate from the headquarters. The firm’s strategy was to target local commercial developers, who seemed in abundant supply, as well as health care institutions (ditto) and a growing roster of corporations fleeing the far more expensive, tax-intensive Northeast and West for a business-friendly climate. The strategy was iron-clad and foolproof as long as the local economy kept up its robust growth.

It didn’t.

By the mid-1980s, oil prices started a downward slide and Dallas was so overbuilt that entire towers sat unleased, becoming unlit behemoths looming in the dark Dallas nights. From 1983 to 1984, when the economic fuel gauge slipped toward empty, the city added a mind-boggling 30 million square feet of office space — this, to an already bloated inventory of unleased space that stretched from downtown

through Oak Lawn to LBJ Freeway and Preston Road over to Las Colinas. Suffice to say, there was a lot of frayed nerves.

Gradually pour into this beaker of nitro the glycerin of the savings and loan crisis, and, by 1986, the region’s architecture firms came to essentially a dead stop. Many of us were used to the whiplash peaks and troughs in the market, but this was terrifying. Layoffs came as every firm in town competed for the smallest crumb of opportunity.

About this time, a fax machine in RTKL’s Baltimore headquarters whirred awake in the wee hours.

To say that international projects were not on our radar would be misleading and unfair. A number of U.S. practices spent the 1970s working in the Middle East, and there was no shortage of opportunities for those willing to make the effort. At RTKL, we had a small taste of it, including embassy work and other federal commissions. Securing the work was difficult; doing the work was even more difficult; and getting paid for the work was the most difficult. (We learned quickly that getting sued was a low-risk threat and that getting paid was where the real exposure lay.]

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. The fax that arrived requested our credentials in large-scale commercial development — mixed-use developments that felt more like city-building than architecture. We assembled a portfolio and sent it via courier — PDFs and email didn’t exist. The request came from a large Japanese conglomerate, the owner of over 30 sites in Japan. The construction industry there was going through a similar boom to the one Dallas had, but with more staying power and government backing. And the numbers were larger — much larger.

In the early 1980s, under Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, Japan had begun to formulate a master reconstruction plan. Its purpose was to frame a comprehensive vision and a set of goals for national development to boost domestic demand. It worked. Land

18 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

"Hey, Willie, why do you rob banks?"

"Because that's where the money is. "

prices shot up, and suddenly what seemed like the entire country was under renovation. Architects, especially those experienced in large-scale development and urban regeneration, were in high demand.

Only later did we discover that the fax we’d received in Baltimore was sent to a number of practices — in fact, many of our competitors. But we were told that we were the only firm that responded.

The timing could not have been better. The Dallas market and virtually the entire U.S. economy had come to a standstill, and our teams needed work. We had scooped up some of the best talent in the profession, recruiting from the best schools in the country, and we worked with some of the best clients in the region, but the work simply was not there.

And so we hopped on planes. As did, eventually, every one of our competitors because that’s what you do when you have an office of over 100 professionals without work. It was not a grand strategic vision that led us to going global — it was survival.

Those early years were challenging, largely because we were unfamiliar with conducting business internationally. We learned quickly that we needed training, so we hired consultants to advise us on basic practices, everything from the exchange of business cards to the appropriate seating arrangements in meetings. While it seems silly now, especially in the pandemic, work-from-anywhere mode, the fact we made the effort impressed our clients.

But we also discovered we had to adopt an entirely different mindset within the organization, one that is not too dissimilar to what seems needed today. Back then we called it entrepreneurialism, but these days we call it agility — the ability to spot an opportunity and act quickly. Or to see that something isn’t working and pivot to something else that is.

It took quite a bit of time to settle on an operational model that worked for us and our clients. The initial approach was to go into the verdant regions of the world (Japan, Korea, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe — China would come later) to harvest the work and then bring that bounty home to be distributed. But our teams spent most of their waking hours on airplanes and in hotels, not a sustainable solution. We burned out staff quickly, often took our best people out

of the game for weeks and months, and wrestled with the frustrations and delays of time zone differences, translations, and mysterious cultures.

We also realized that we needed an entirely different administrative infrastructure. From legal and finance, HR to marketing, we needed the right professionals and protocols to play on a global chess board. But our biggest eye-opener was technology. We were smart enough at the time to understand the value of hardware — those giant Intergraph 2700 workstations still haunt our dreams — but we could not have imagined the implications of working and communicating seamlessly across international boundaries. The lessons learned in those early years still apply today.

The decision to go global was the right one at the time, and many firms of our size did the same thing. The experience drove home the importance of diversity not just in markets and project types but also in geographies. There were times when our non-U.S. revenue outpaced our domestic income, and vice versa, but having a broad, diverse base was the correct strategy. We also discovered, perhaps later than we had hoped, that it was easy to become too reliant on the international gravy train. The projects were meaty. The fees were big. But it is essential for any firm to maintain a presence in its local community and nurture relationships with the clients down the street.

The world opened up to us in the 1980s largely because we had the right people in the right places in the right times, and Dallas happened to be one of those places. We pursued the work aggressively because we had to — not because that’s where the money was, but because it provided expanded opportunities for our people and our company. It made us better professionals and better architects. It challenged us on multiple levels. And when you’re an architect in Texas, it’s hard to walk away from a challenge like that.

Lance K. Josal FAIA is CEO emeritus of CallisonRTKL and founder of 11AD. He has lived in Dallas since 1979 and has worked throughout the world. Thom McKay is a marketing and communications strategist who opened RTKL’s first international office in 1990 in London.

19 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

Photos from this spread are snapshots from RTKL’s global practice in the `80s, `90s, and 2000’s / Photos: Lance Josal, FAIA & Thom McKay

THE THIN RED LINE

By Gavin Newman

By Gavin Newman

Think about an ordinary residential street. In Dallas, it’s wide enough for cars to park on one side and two others to drive past, and it probably has sidewalks on each side of the street. If you’re lucky, you might get the pleasant experience of having some trees along that street and maybe a bike lane.

However, each residential street exists in dual states. In one state it is the means by which we go to work, we go for a walk, and the corridor in which we might meet our neighbors; in its second state, in crisis, an ambulance speeds to the sick or injured, or a firetruck deals with a nightmare situation. Ultimately, these residential streets create a network of infrastructure to allow for public safety in the event of crisis.

In many Dallas neighborhoods built in the early 20th century, gridded streets and blocks were the de facto position in urban development. Then the story of 20th century urbanism was to do everything we could to avoid grids and blocks. For many places developed post-World War II, a city street cannot serve well during an emergency. For these occurrences, we have fire lanes, better known in our building codes as “fire apparatus access roads.”

Allow me to project for a moment: I don’t have much affection for fire lanes. I imagine you might not either. They eat up valuable land (that isn’t getting any cheaper), they get wider every time I turn around, they lay down concrete where we want a field of green, and who doesn’t like a shock of red striping running through the middle of their site? Given the choice, who’d pick this?

Fire lanes are not supported by theory, either in origin or in their current requirements. Rather, they respond to a particular history of decisions to increase safety for our first responders (and general public?). In this history, things burn. Until the 20th century, cities often burned, with the blazes becoming known as “The Great Fire of ______.” (If you’d like to read up on the history of urban fires in America, Peter Charles Hoffer’s book Seven Fires: The Urban Fires That Reshaped America is a fantastic resource.)

And out of each fire came progress that slowed the next great fire: London burns, and the next London is built of brick.

Of particular interest in the tools of firefighting: the fire engine, replacing the bucket brigade that moved water onto a fire. For the purposes of fighting a blaze, the fire engine is a mobile pump. Pumps have existed since antiquity; the modern fire engine emerged after the invention of the brass and leather fire hose in 1672. With this means of dispensing water, the Dutch-English inventor John Loftin patented the “fire sucking worm,” the first mobile fire pump with sufficient pressure and throw to fight fires.

These early firetrucks were drawn by men. Some firsts are hard to pin down, but in an attempt to present some chronology I’ll offer the following: In 1832, volunteers of the New York Mutual Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 bought a horse to pull their fire engine; horses remained in service after the 1841 emergence of the steam-powered pump, far more effective and far heavier than the previous generation of manual pumps. Detroit saw the first use of a gasolinepowered tractor in 1922, ushering in the retirement of horsedrawn pumps.

Anecdotes fill the history of firefighting. When the first horse-drawn engines replaced man-drawn engines, one group of pump-moving men, fearful of being replaced, sought to shame neighboring firefighters by painting their horses and shaving the animals’ manes and tails. Horses were only accepted into wider use with the advent of the heavier steam pump. When Detroit debuted the tractor-truck propulsion, the city gave the horses a ceremonial last run; it is said that firefighters and residents complained for years about the trucks, seeing the horses as more reliable.

21 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

It might be characteristic of firefighting to both adopt new technologies and cling to practices known to be effective. The fact that firefighters have sought the best tools available to them (better pumps, better means of moving those pumps) is easily understood through the lens of self-preservation against a chaotic danger. These tools, as well as the regulatory frameworks to require safer, less combustible buildings, have worked toward protecting life and property.

The City of Dallas operates on an amended version of the 2015 International Fire Code (IFC). (Actually, every city in Dallas County operates on some version of IFC. Check your jurisdiction, but the parameters remain the same.) Section 503.3 of the code governs fire apparatus access roads, with additional requirements in Appendix D. A rough outline of this section includes where these roads are required, their physical specifications, their markings, and what happens if you block them intentionally (gate) or unintentionally (cars).

This is a situation where the glove must fit the hand. Much here is left to the discretion of the fire code official, given that the firetruck and equipment deployed changes with each site and need, noted regularly through IFC as “when approved by fire code official.”

There are set points with the fire lane, having more to do with how far a firefighter could pull a hose (they’re heavy) and how much clear width a first responder needs with the bulk of protective gear on them. Where base IFC and Dallas amendments do allow for variation is in the size of the fire access road width and the turning radii. These sizes are based on the size of the firetruck most likely to show up on-site.

Section 503.2.1 of IFC outlines a minimum required width of 20 feet with a turning radius of 28 feet and a clear height of 13

feet 6 inches. When a building is taller than 30 feet, this width increases to 26 feet for at least one of the required routes, which must be between 15 feet and 30 feet from the building.

As Dallas buildings have grown in height, its fleet of firetrucks has changed to reach these heights. For buildings taller than 30 feet, aerial trucks are used. These are the trucks that children’s toys are modeled after, equipped with a mobile boom able to lift firefighters to a window and to retrieve people. Suffice to say, these are complicated, expensive pieces of machinery. The city recently spent $1.6 million on a new truck. As buildings get taller, these trucks get longer as their ladders lengthen. Requirements for wider roadways and turning radii are largely from the need to deploy this kind of vehicle.

The clear height of fire lanes might suggest they can be routed underneath a building, or a section of a building, but this not preferred.

“[It] is not desirable to have a structure cross over a fire lane. … Such structures prove to be an obstruction to responding fire personnel,” said Ricky Butler, fire protection plan reviewer for the City of Dallas. When pressed on specific instances, say a bridge passage between buildings, “structures over a fire lane shall be as limited as possible,” Butler said.

IFC is concerned with whether firetrucks can get there and the type of surface they’re on. Dallas’ amendments stress that the fire lane should be built of asphalt or concrete, but allows alternate paving methods so long as they can support loads of 81,500 pounds and are passable in all weather conditions.

“Grasscrete” serves as the shorthand. Fire personnel are interested in an “engineered and repeatable permeable

22 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

based system … that is determined to be all-weather in their capabilit[y].” If a fire lane is constructed on top of a parking deck or runs over a bridging element, additional engineering standards apply and should be discussed with the fire code official.

Some low-hanging fruit with fire lanes is their markings. Dallas’ amendments add language describing a 6-foottall continuous line of red paint with 4-inch tall text and the possible use of a sign of set size in lieu of striping. San Antonio’s fire code allows fire lane markings to be up to 40 feet apart and marked with materials other than paint such as red tiles within the paving. In Dallas, though, the consistency of the fire lane marking is of great importance.

“This consistent indication notifies the responding firefighter or paramedic that a fire apparatus access roadway has been properly designed per current amended fire codes,” Butler said. “Properly designed fire lanes can alert first responders of possible hazards and overhead obstructions or underground structures that might not have been designed to support the imposed load of the fire apparatus.”

If there is a question of what the fire lane ought to be, an obvious answer would be for it to be less conspicuous, a little more like our residential streets. A residential street is about pedestrians and cyclists and cars, trees and sidewalks, but not crises. there are ways of recovering this piece of infrastructure for place-making effect.

The marked fire lane is an information problem. First responders move fast (and sometimes break things), and that red line painted on the curb is their best way to distill the built environment into a go/no-go scenario. But as an information problem, it has other solutions.

I broached the idea of a GIS dataset that could incorporate this information for firefighters, a new kind of fire map. “That’d be awesome,” Butler said. Of course, this should not be taken as a coordinated response of the city, but it does hint at a potential solution.

Slimming up the fire lane is a whole other battle. The place-making desire for narrower streets is often at odds with the fire lane minimum requirements. Smaller trucks, or at least nimble trucks with smaller turning radii, would go a long way toward helping, and the industry may provide that at some point.

Current options might include mountable curbs so that the largest fire apparatus could move through a site in the off chance it must. When asked about mountable curbs, Butler said, “They often do not allow [for] proper placement of the outriggers on the fire apparatus prior to engaging in aerial maneuvers.” With this difficulty, the benefits of mountable curbs should lead us to find a resolution on how to address the technical requirements of fire equipment.

At some point Dallas will adopt the 2018 version of IFC; while the text governing fire lanes between 2015 and 2018 does not change, Dallas’ amendments might. Fire lanes are not currently positioned as place-making devices in the city of Dallas; IFC allows the fire code official some leeway, encouraging more conversations. Through wise application of new technologies by firefighters and through placemaking advocacy on the part of those engaged with the built environment, this necessary piece of site infrastructure can be made into a place to enjoy.

23 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

Gavin Newman is a project coordinator at GFF.

A mobile EMS unit, one of many vehicles in a fire department’s arsenal, leaves the BRW Architects-designed City of Houston Fire Station 84. / Photo: Parrish Ruiz de Velasco

Offices in DALLAS BOSTON and now AUSTIN 214.871.7010 | lafp.com Rolex Building

This North Texas Space? Find the what, where, and more on page 64.

Can You Identify

IN CONTEXT

Photo: Alicia Spaete

The Emotional Impact of Safety

Balancing technology and psychology in design innovation

By Alison Leonard, AIA, EDAC

By Alison Leonard, AIA, EDAC

26 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

Above: Strawberry Hill Behavioral Health Hospital, The University of Kansas Health System, Kansas City, Kansas / Photo: CannonDesign

We see new safety features every day: metal detectors, plexiglass shields, bullet-resistant glazing, and cameras. While society expects this extra security in order to feel safe, at what point do all of these additions detract from the original design intention of the space?

Yet concept sketches and vision boards for projects never feature security cameras, social distancing parameters, exit lights, or metal detectors. Designers consider the feelings they want the space to evoke and make decisions with intention. How do we incorporate safety precautions that current events dictate buildings need without interrupting the design purpose? At what point do the security features meant to ensure a feeling of safety instead detract from our emotional health, disrupting education in schools and healing in healthcare environments? No matter the type of building, a common theme is evident — reducing stress while fostering and maintaining a sense of community.

The public expects to see security features in municipal and civic buildings and at transportation hubs. But people don’t expect to see them extensively in healthcare, worship, and educational environments. Hospitals and churches are places of hope and healing, and schools are places of learning and community gathering.

Whatever the function of the building, the psychology behind space design is an important consideration. The senses play a critical role in how the human brain interprets where you are and how the space makes you feel. The scale of a room evokes feelings of intimacy or of grandeur. Natural light provides a connection to the outdoors, while a lack of windows can cause claustrophobic conditions or the “casino effect” of losing track of time. Colors and materiality of finishes can drastically change a space from dark and serious to light and whimsical. Each of these factors creates a feeling; in these ever-changing times, feeling safe and secure is vital.

The design of healthcare spaces always presents a challenge. While the goal is to create a patient care environment for clinical success, the patient experience

must also be positive and calming. Hospitals, surgery centers, and emergency rooms can be overwhelming to anyone — long hallways, crowded waiting rooms, cold and sterile procedure rooms, and confusing noises. The care team is often stretched thin, working long hours with limited resources, and patients can endure long waits. The COVID-19 pandemic has created isolated environments for patients and clinicians alike, as well as the need for more robust infection control measures. Add a patient in the throes of a mental health crisis to the situation, and the stress levels skyrocket for all involved.

Emergency rooms are not equipped to handle the influx of mental health patients needing help, and that number of patients has increased throughout the pandemic as it continues to take a toll on society’s collective mental health. Standard treatment rooms are not typically designed to provide the level of safety and security for patients in crisis who may harm themselves or who present a danger to the care team. Unfortunately, much of the stigma around mental illness keeps those who need help from seeking care until they are in crisis. Only after being evaluated in an ER will the patient potentially be transferred to a hospital better equipped for psychiatric treatment.

Psychiatric hospitals and behavioral treatment center designs must balance safety and aesthetics. The building has to address the potential for self-harm with vulnerable patients as well as protect healthcare staffers, but also consider the psychology of the built environment.

In recent years, behavioral healthcare design has evolved. Treatment models are no longer synonymous with the asylums portrayed in the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest . New facility design employs evidencebased research, and designers have borrowed innovative European concepts to revolutionize psychiatric hospitals in the United States. They foster a normalized environment for care by incorporating key elements such as natural light, views of and access to the landscape, unique and flexible therapy spaces, and durable but homelike materials.

27 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

It is no surprise that violent events like the Sandy Hook, the Sutherland Springs church, and the El Paso Walmart shootings and public health threats like COVID-19 have changed the perception of safety and security in buildings.

This specialized building type requires a “form follows function” approach to planning and design. It is essential that layouts manage safety concerns for both patient and the care team. But a thoughtful layout, program space adjacencies, and access can help mitigate safety concerns. Flexible use of space is critical when square footage is at a premium and clinical staff prefers a variety of therapy options. Flexibility is also integral because the population and its needs may change.

The approach to the building and the path to the intake area should be simple. The lobby of a mental health unit shouldn’t feel any different than that of any other hospital. A focus on hospitality and dignity, combined with staff empathy, can build trust and camaraderie between the new patient and the care team. It’s important that the intake process not add to anxiety and also vital that the patient and family feel comfortable enough to share information for the staff to complete a thorough risk assessment. Understanding the patient’s stress points is crucial for safety and security and ultimately recovery.

A design risk assessment will also steer the building design. Understanding staff operations and the clinical team’s approach to patient therapy can lead to a design that creates a collaborative healing environment. On some scale, decisions will be made about which program spaces are high-, medium-, and low-risk. High-risk areas include patient rooms, toilet rooms, and other spaces where a patient shouldn’t be left alone; medium-risk spaces have staff supervision, a group type setting, or limited access for some patients. Low-risk spaces are typically public areas, administrative areas, for staff only, and support spaces on the unit that are locked. Design decisions will be made about which spaces and risk levels will require ligatureresistant fixtures and hardened finishes. Other infection

control and social distancing considerations may need to be factored in for each type of space, depending on the trajectory of COVID-19 and future pandemics.

For inpatient hospitals, the specific populations (adolescent, adult, geriatric) and acuity levels dictate the ideal number of patient rooms per unit, unit shape, and length of corridors. Design trends include open care team stations to encourage transparency between staff and patients and to facilitate communication and trust. Some staff still prefer a closed care team station for protection from potential patient violence.

Research has shown that a hybrid model between the two options may be the best solution. A direct line of sight from decentralized care team stations into patient rooms is the best practice for patient safety as well as discouraging negative behaviors and affording patients some choices and control of their personal space. Singleoccupancy rooms are typically preferred. Sometimes they can be personalized with a color preference, offer privacy for quiet meditation, and respect dignity — especially when sensitivity is needed regarding gender.

It is also important to provide areas outside the patient’s room for interaction. Large, flexible spaces for group activities are necessary, but it is also important to provide quiet areas like window seats or built-in benches along a corridor. Unique spaces for therapy like music, art, gardening, and dance allow expression. A gym provides space for much-needed exercise and activity, especially for pediatric and adolescent populations. An enclosed courtyard with views to the exterior gives patients access to fresh air as they walk on secure paths. When needed, a sensory room creates a safe space for a patient who needs to de-escalate. This innovative room, a safe alternative to moving a patient into seclusion, includes

28 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

The Behavioral Health Pavilion (left) and Crisis Response Center at Banner-University Medical Center South in Tucson, AZ / Photos: CannonDesign

music, lighting, tactile elements, and images to meet any patient’s needs.

While material selections may vary between pediatric and adult populations, one thing that doesn’t change is the importance of patient safety. Colors and textures are essential to human-centered design, but understanding the risks associated with standard design elements in behavioral health environments is imperative. Increased infection control measures from COVID-19 can also limit the type of materials available for use.

The addition of building materials with warm wood finishes, natural textures, and colors supports a normalized environment for healing. Durable, easy-to-clean surfaces are essential, but some impact-resistant materials make it difficult to control sound levels and may require supplemental acoustical products. Continuous sheet flooring with an integral or mechanically-fastened base is best. This helps avoid wall base that can be peeled off and used as a weapon. Ceilings should be at least 9 feet high above finished floor and contiguous in high-risk areas. Products like acoustical ceiling tile in a grid should be avoided as they allow patients to hide contraband. Lighting fixtures should have lenses, be recessed where possible, and have a tunable control if possible. LED lighting that can be adjusted to the circadian rhythm is beneficial and requires less maintenance than typical lamps.

Eliminating everyday items that can be used to loop, wedge, or create a point of ligature is challenging but necessary to create a safe environment for patients at risk. In the last decade, the market has grown exponentially with safe, innovative products that are aesthetically pleasing and ligature-resistant. In past years, fixtures were stainless steel, prison-like, and sterile. Built-in furniture and millwork that include a sloped top enclosure are dependable

options, in addition to the few furniture companies making off-the-shelf solutions. Products that must be selected for patient and staff security include door hardware, glazing and exterior windows, lighting and plumbing fixtures, mechanical diffusers, toilet accessories, furniture, sealants and fasteners, and interior finishes.

When we think about the role that safety and security play in the psychology of spaces, mental healthcare is different from most building types. While airports and municipal buildings make their security features noticeable enough to deter trouble, behavioral health facilities typically do their best to blend it away. To reduce stigma around mental health design, designers strive to normalize the built environment for care.

Thoughtfully designed spaces can empower patients, foster feelings of independence and dignity, and discourage some negative behaviors. Many providers are quick to build a fortress and prison-like environment, thinking that the highest level of safety and security possible is best when, in reality, a balance between the safety level and creating a healing environment promotes accountability and wellness. The extremes limit recovery and can cause patients to be defensive instead of open to new ideas and coping techniques.

To choose which types of spaces to be in (like sociopetal spaces designed to bring people together) or sociofugal spaces (designed to emphasize privacy) to dim their lighting, adjust their temperature controls, or simply open the window can foster the sense of control that a patient may need to jump-start a journey to wellness. Allowing patients the freedom of choice is a welcomed privilege.

29 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

Alison Leonard, AIA, EDAC is associate vice president at CannonDesign.

VCU Medical Center, Virginia Treatment Center for Children, Replacement Facility, Richmond, VA / Photos: CannonDesign

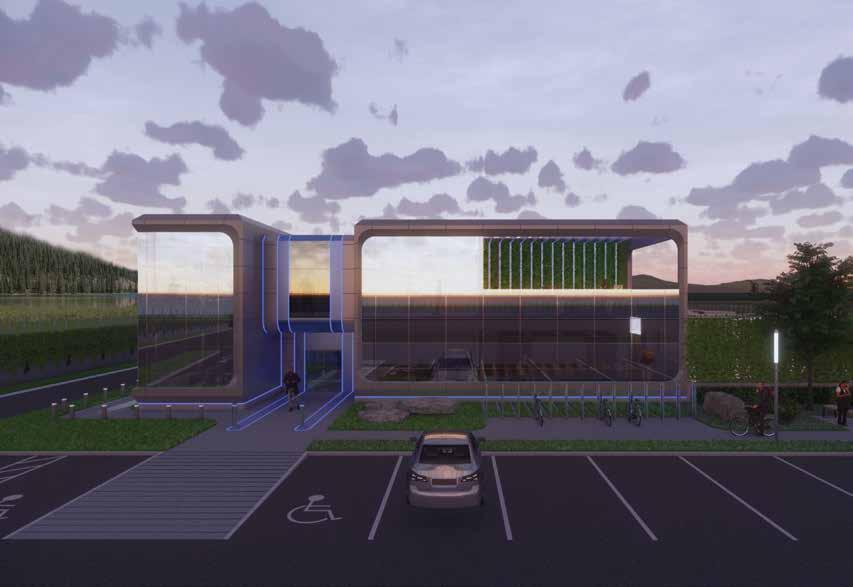

THE NEW AGE of SECURITY

Technology in a post-pandemic world

By Samantha Flores, AIA, NCARB, RID

Facial recognition instantly analyzes 80 unique nodal features to verify personal identities—a highly secure method of touchless processing used for everything from surveillance to digital wallets.

The pandemic has raised new questions on what it means to design for a world that is forever changed and what safety looks like in these places. Whereas issues of security are primarily concerned with mass shootings, unauthorized visitors, harassment, violence, theft, and vandalism, world events now require that we plan for a future where the safety of individuals and communities are also defined by protecting the health and well-being of its citizens.

Global economies and social dealings have made us especially vulnerable to the quick spread of viruses and other contagions while also making it difficult to implement the solutions to contain these threats once exposed. Designing for an invisible enemy that could quickly and quietly threaten the safety and security of our modern world has prompted designers to investigate the implications for architecture, including questions on how the built environment can detect and respond to threats to our public health. The call on architecture is not new — responsible, human design has always asked for design solutions and spaces where users feel safe. The pandemic, however, fundamentally confronts public spaces and challenges designers to creatively adapt to not only reduce viral spread but also to re-establish communal trust in these places.

The answer is not simple. Rather, any successful response to this historic change in our global culture will be layered and fraught with trial and error. Our core relationship to our built environment requires design to look ahead to a continually evolving definition of what it means to be and feel safe — anticipating the next iteration of threat on our collective security while preserving and even amplifying a more personal experience. Deeply invested in these issues, design has the potential to embrace the ways our society and lives have changed both on account of this pandemic and before it to offer spaces that restore our sense of stability and community.

Novel technologies and the world of big data have not only made possible several necessary accommodations in a post-COVID world — remote work, on-demand delivery services, contagion tracking — but have also provided powerful tools for solutions that make possible a safer, healthier world.

BIOMETRICS

Our world was already headed toward a seamless world where everything is at our fingertips, but the COVID-19 pandemic has required that seamlessness now take on a touchless capability. From contactless doorstep delivery of groceries to virtual telehealth appointments, security in the modern world has expanded its scope to creating and sustaining the protection of personal space. Lessons from the COVID-19 outbreak not only challenge us to reconsider social norms such as shaking hands but also demand that responsibly designed spaces support our new best practices — minimizing touchpoints and providing options that maintain the humanity of our experiences while mitigating the risks of person-to-person contact.

Biometrics offers a powerful tool to use unique features such as a person’s speech, fingerprints, gait, or facial features to instantly identify and often personalize the built environment and user experience. Biometric processing can provide building access, serve as payment methods, or be used for surveillance or targeted marketing without requiring a license, wallet, or key fob. Biometric processing points at airports — convenient, secure, and touchless — have begun to transform the passenger journey from curbside and TSA checkpoints to retail concessions and boarding at the gate; they offer models for larger-scale adoption.

As we’ve become more aware of covering our coughs, keeping six feet apart from each other, and donning masks, biometrics offers the potential of voice activation, facial recognition, and gestural technology to replace elevator buttons, keypads, switches, and doorknobs. Removing bottlenecks caused by gatekeepers or analog functions, these technologies can also keep traffic moving, reduce congestion, and prevent lengthy queues.

Biometric technology has become increasingly popular for its ability to personalize experiences. For instance, at airports, facial recognition paired with push notifications can alert passengers when and where to board, suggest tailored concessions, and even help people connect to lodging and ground transit information.

DIGITAL TWI NS AND BI G DATA

These types of personal user experiences within the built environment can be managed through a building’s digital twin, a highly complex virtual model that is the exact counterpart of the physical environment. A digital twin gathers data from seemingly infinite points in the physical environment — lights, doors, HVAC systems, behavior patterns, and much more — to improve decisionmaking, preventive building maintenance, and responses to changing demands. These models not only have a

31 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

For architects, the rapid spread of COVID-19 creates challenges on current building typologies, how people interact in and experience public spaces, and how people understand the value of place.

communication platform with the users of the space, responding to commands in real time, but also permit building-to-building communication. These buildings “learn” from one another through a complex network of advanced analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence, working together to glean real-time insights. Digital twins provide a powerful understanding of how people engage with the built environment while identifying opportunities and patterns for increased efficiencies and quicker responses to pain points and potential challenges.

The digital twin can monitor indoor health and safety by providing information on air quality, precision maintenance, targeted cleaning, and potential operational improvements for better safety and hygiene. In times of pandemic, a digital twin of a large public space, such as an airport, office, or a school, could simulate safe escort routes in the event that someone is found to be infected, provide adaptations to the environment for isolation, put maintenance protocols into place, and alert building occupants of any temporary changes in building access points — all without the need to build permanently isolated circulation routes into the

physical space. On a larger scale, digital city twins can tap into the Internet of Things, or IoT, systems and public databases to simulate disaster readiness — a tool that helped Singapore manage the pandemic by monitoring foot traffic and building occupancy.

EDGE DATA

Large volumes of data, uninterrupted connectivity, massive storage, and the bandwidth needed to keep current and emerging technologies operating can overwhelm existing networks. When fully realized, digital twins and biometrically enabled public spaces that gather and analyze data points for billions of people and countless built environments will require a new framework for managing data.

Our world runs on the internet. We use it to keep our social networks running, stay connected at work, and shop for groceries. Our dependency and demand grow as we see the potential of technologies to mitigate biological threats and explore their capacity to provide a solution to our world’s current pandemic. From tracking viral outbreaks in real time to expanding the services we need to support

Dynamic real-time data from digital twins empowers better decision-making, improved monitoring and maintenance, and faster responses to building and user needs. / Credit: Corgan

our new normal, our need to connect anytime, anywhere is more important than ever.

The round-the-clock exchange of information over Zoom calls and social media and an infinite world of smart phone applications that bring your favorite restaurants and studio workouts into the control of your home create an insatiable need for data — fast, reliable data.

But latency, introduced by the distance from remote data centers, hampers the way we live and do business. The global response to COVID-19, as well as our sense of safety, has hinged on our access to data and the internet.

In the race for more connectivity at faster speeds for more parts of our life, edge data solutions have the capability to distribute high-performance computing closer to the end user. Scalable, smaller footprints embedded throughout dense urban locations or deployed in remote areas also help democratize the infrastructure we need.

CONCLUSION

The scale, complexity, and urgency of today’s global problems, as shown by the pandemic, do not lend

themselves to easy answers. Instead, these technologies provide the tools for agility and to preserve the cultural value of places. Empathetic design must consider and anticipate evolving expectations, fears, and anxieties about using public spaces and our changing definition of safety and security in the wake of COVID-19.

Our world will never be the same. COVID-19 has radically tested the foundation of community and the spaces that bring us together — places that were designed to encourage face-to-face connection and remove barriers to exploring what makes us human. Reintroducing these spaces into our new cultural vocabulary after months of sheltering in place and social distancing provides a powerful opportunity for design to do what it does best — adapt. And, where the future seems uncertain and the impact of this pandemic is still to be fully realized, these technologies give design the tools we need to be agile and stay human.

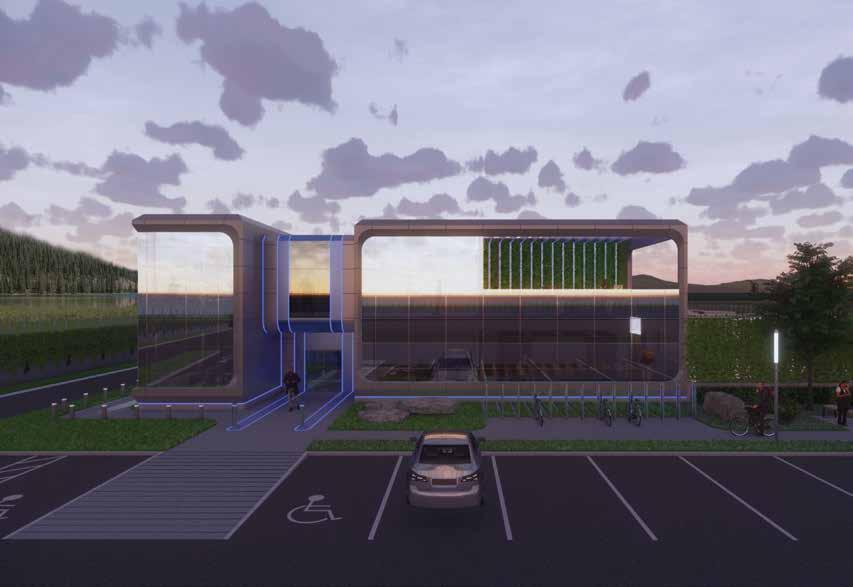

With an insatiable demand for data, Corgan and TMGcore’s conceptual designs call for a data center that is a tenth of the usual size but that offers greater computing capacity while greater computing capacity while reducing latency and expanding deployment. / Credit: Corgan

Samantha Flores, AIA, NCARB, RID is the director of HUGO, a research and innovation team at Corgan.

Samantha Flores, AIA, NCARB, RID is the director of HUGO, a research and innovation team at Corgan.

KIRK HOPPER FINE ART DESIGNER SERVICES

Consult with designers

Client collections

Special discounts and incentives offered to interior designers

Visit us at our new location in the Dallas Design District

1426 N. Riverfront Blvd Dallas, Texas 75207 214-760-9230

Tuesday to Friday, 11 to 5 Saturday, 12 to 5 kirkhopperfineart.com

ALICE LEORA BRIGGS THE SCENT OF REASON

34 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

Floyd Newsum, Remembering Winter in Chicago 2010, oil on paper, 80” x 65”

DECEMBER 3 – JANUARY 14 KIRK HOPPER FINE ART 1426 N. RIVERFRONT BLVD, DALLAS KIRKHOPPERFINEART.COM

A Walk in the Parks

Nate Eudaly, Hon. AIA Dallas, member of the Columns Committee and executive director of the Dallas Architecture Forum, moderated a panel on “Safety in Public Spaces” with four Dallas leaders on parks, trails, and public spaces, especially in the wake of COVID-19. Although the session took place April 9, 2020, the Q&A has been updated as well as edited for brevity and clarity.

The panelists were:

Bud Melton of Halff Associates, an expert on bicycle and pedestrian trails and a member of the Product Council of the Urban Land Institute.

Chuck McDaniel, FASLA managing principal and lead designer of the SWA Group, designers of the Katy Trail and Pacific Plaza.

Dustin Bullard, ASLA of Downtown Dallas Inc., who oversees park planning and public space management for the central city.

Emily Henry, ASLA a principal with Studio Outside Landscape Architects who focuses on people and community.

DIALOGUE

NATE: What is the balance between leaving public spaces in their natural condition versus inserting programmatic design that improves the safety of people using those spaces?

CHUCK: Well, I’ll start with the Katy Trail. It traverses through an actual space that grew up around the rails over the decades, and it is very unprogrammed space, or at least it was until the development boom that went on adjacent to the trails. I’m not for programming the Katy Trail too much. I think it ought to have all the public access points that we need for ADA accessibility, but I’m advocating for fewer bicycles on the Katy Trail. And I’m also advocating strongly for a revegetation of that corridor to let that urban forest regenerate.

EMILY: There are a lot of benefits of being immersed in nature for us in Dallas. Since we are in an urban environment, having those small areas in which we can engage with nature is very important. We’re lucky to have the Trinity River and the Trinity River Basin to really allow people to engage more in those natural environments. It is super important to allow it to be raw and unprogrammed because the immersion in nature is so important to the health of human beings. And I think a lot of times we view humans and nature as separate, but we need to remember that we’re not, and it’s important to have those spaces of respite where it is natural, untouched, and unprogrammed.

BUD: I think programming the trail for formal group activities is problematic in terms of conflicts with other users and adjacent property owners. Over the years I’ve had numerous discussions with the Katy Trail Friends Group about access, and they’ve wanted to limit the access and I’ve said it needs to be as permeable as possible. So Chuck, I agree with you that more is better as to the accessibility of the space and would help relieve some of the bottleneck conditions that occur. There should probably be more signage and understanding of how to use the space.

DUSTIN: What’s great about an urban park system throughout the city is that you have a mix of spaces, and you have some spaces that are highly programmed and highly designed for a variety of uses. But having these more natural spaces is really important to the overall park system, to relate back to nature for our citizens. We must push that every space does not have to be a highly programmed urban park. There are a lot of spaces where we should tread lightly, within minimal programming, and I think it’s healthy for the community. And we’ve seen great success in that. I think COVID has shown us that a lot of the parks people are flocking to are places like Katy Trail and White Rock Lake. We’re not seeing people flocking to the more programmed spaces like Klyde Warren or Pacific Plaza.

EMILY: It’s definitely an advantage that we have many spaces in Dallas that are still very much untouched. Some people don’t feel like they have the invitation to go into the Trinity River Basin or the Trinity River Forest, which is the largest hardwood forest in the country. But for some it is an issue of safety and a bit of fear of the unknown to explore them because of their vast size and lack of safety features.

NATE: Let’s talk about lighting. There’s a consensus that we want to preserve the natural environment while incorporating basic concepts of safety. What responsibilities do you think developers, planners, designers, and municipalities have to install lighting?

BUD: Traditionally, the park department has resisted putting much lighting on the trails. We’re at a point now with light technology where there’s an opportunity to step back and revisit how we put lighting into civic space. I’ve coined a phrase: “Taming the shadows” in civic space, which maybe gets away from the uniform building code requirements of lighting but instead looks at how you do an aesthetic that eliminates the dark shadows and makes it possible to feel comfortable.

CHUCK: I like the fact that the Katy Trail is strategically illuminated because it’s got such other depth and other interest at night. We have to illuminate things, but I don’t think it has to be bright. There needs to be a certain amount of light to be able to recognize people, and you also want to let wildlife and foliage be seen. So there’s a lot of merit for proper lighting.

EMILY: Lighting obviously is the biggest thing we can do to eliminate the fear factor of public space at night.

NATE: What’s your view about security cameras and facial ID? There’s a lot of technology, much of it expensive, but how does that play into safety versus invasion of privacy. Should it be incorporated into public spaces?

CHUCK: I’m really torn on this. I don’t like Big Brother looking over our shoulder. But in conversations on every park I’ve ever done, if you have a camera, you’re giving the user the impression that somebody’s watching. We decided not to do cameras on the Katy Trail and in Pacific Plaza simply because of the expense of monitoring and providing safety. But Pacific Plaza has opened with ambient light that meets all the Dallas lighting codes. I think a part of society will get into mischief in parks if they feel like no one is going to be held accountable. But I really wish we could get to some way to provide immediate, tangible observation of our public spaces.

EMILY: And you wonder if people felt ownership — you know, this is my Dallas park — there’d be a sense of pride. I think use of cameras is a tricky topic because you don’t want an intrusion of privacy. Especially as technology is advancing, and you’re starting to see programs that track people’s faces. It’s kind of scary where some of this is going. But it does provide, again, that sense of safety so it’s a balance.

DUSTIN: With cameras it’s a double-edged sword. I’m more of a big government guy in that I don’t have as many concerns about people watching public space through the cameras. We have a robust camera network in downtown that our organization was the lead champion for 10 to 15 years ago, and we funded additional cameras at Civic Garden and Pegasus Plaza and Main Street Garden. All city camera networks, all monitored by the Dallas police fusion center. That’s part of a citywide network. More than anything, they’re a deterrent to mischief. I think if someone sees the camera, they think, oh, I might get caught. There has to be an acknowledgment and some level of risk that we all take in public space. Cameras are amazing when we have a protest or large

36 COLUMNS // aiadallas.org

events at the parks. We can actually reduce the number of police officers in a given space because we can better monitor that from a remote location by camera. It’s very helpful for DPD to be able to remotely monitor the situation on the ground and maybe stage their assets, police, behind the corner. And it looks better, and it functions better for those folks exercising the First Amendment.

NATE: Let’s talk about scale. If someone goes to one of the downtown parks, it’s more tightly programmed to maintain a sense of safety than the Katy Trail or White Rock Lake, and even less so when you go to the Trinity River Forest. Do you think scale and maybe urban versus rural has different ramifications and expectations?