S S Se e em m mi i ic c co o ol l lo o on n n

An AHSC Publication An AHSC Publication An AHSC Publication

An AHSC Publication An AHSC Publication An AHSC Publication

Copyrights remain with the artists and authors. The responsibility for the content in this publication remains with the artists and authors. The content does not reflect the opinions of the Arts and Humanities Students’ Council (AHSC) or the University Students’ Council (USC).

Vice President Publications

Nicole Godlewski Hennigar

Assistant Vice President Publications

Alyssa Naoum

Creative Managing Editor

Tanya Matviyiva

Academic Managing Editor

Lina Drummond

Layout Editor

Evan Rogers

Cover Designer

Kendra Jackson

Copy Editors

Khadeejah Abdul-Khadir

Afrah Fatima

Cadence Desmarais

Iris Zhao

Social Media Coordinator

Beatrix Nemec

Alumni Relations Commissioner

Paige Hammond

Symposium and Semicolon are the official publications of the Arts and Humanities Students’ Council, published bi-annually. To view previous editions or for more information about our publications, please contact us at the AHSC council office in room 2135 at University College. Publications can also be viewed virtually at issuu.com/ahscpubs

Semicolon is the academic journal for the AHSC. It accepts outstanding A-level submissions written in any arts and humanities undergraduate course.

Dearest reader,

Living in an age of uncertainty, it is easy to become overwhelmed We are fed an endless stream of violence, conflict, ecological peril, and technological upheaval at a staggering rate There seems to be so much happening all at once that it becomes difficult to situate ourselves amid the chaos and as A&H students, it certainly doesn’t ease anxiety knowing that AI lurks around every corner, just waiting to snatch our jobs. The theme of this issue is Regenesis, which beckons new ways of thinking about the future It challenges us to question tradition and explore our intimate opinions to help us navigate uncertainty and create space for a brighter future

Symposium and Semicolon have showcased 12 Volumes of exceptional creative and academic work in the Faculty of Arts & Humanities. Each year we are amazed at the dedication and artistry of A&H students, and it is an honour to present to you Issue One of Volume 13 The compilation of poetry, prose, visual art, and essays in this issue is truly a testament to the resilience of art, culture, and intellect We are so proud to represent such phenomenal work within Arts & Humanities and thank you to everyone who submitted.

The AHSC Publications team has been working diligently throughout the semester to produce the publication you are currently reading From carefully selecting your wonderful submissions, to reading over the final products, they have been rising to the occasion every step of the way. I would like to extend my gratitude to our AVP Alyssa for all the support; Kendra for the beautiful cover art; Evan for the layout; Tanya and Lina for managing submissions; and to our copy editors, Khadeejah, Iris, Cadence, and Afrah Your contributions have been invaluable

Finally, I would like to thank you, dear reader. Whether your work is featured in this issue, or you are simply skimming through a publication that caught your eye, your support means so much to all of us on the publications team I hope you find something beautiful and learn something new in these pages

Bridging the Gap: Land Acknowledgements, Newcomers, and Canadian Settler Colonialism by Anna Oliveira

Irrational Selfhood: The Underground Man’ s Struggle Against the Enlightenment Ideal in Fyodor Dostoevsky’ s Notes from Underground by William Rodrigues

Embracing Temporal Liberation: Resilience and Memory in Janelle Monáe' s "Dirty Computer" by Shely Kagan

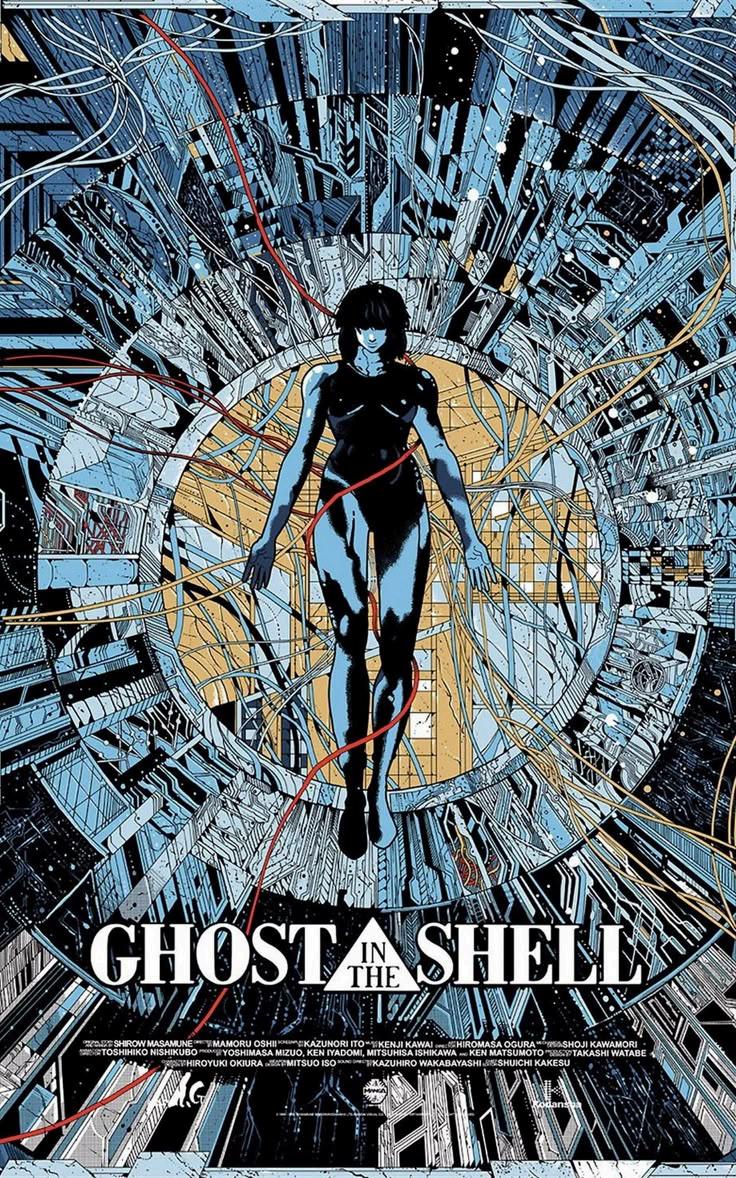

Transcending the Shell: The Gendering, Subjugation, and Liberation of Cybernetic Feminine Bodies in Ghost in the Shell by Purushoth Megarajah

Food Culture: Loss of Identity in Zitkala-Ša’ s Autobiography by Amy Heaman

The Personal has Become Political The Conflation of the Private and Public Realms by Heather Stanley

Marriage, Inheritance, and Economic Dependence in She Stoops to Conquer and Sense and Sensibility by Elora Chambers

Race and Modernity in Harlem - A Comparative Analysis of the Photographs of Roy DeCarava and Paul Strand by Emma Hardy

The Dual Narrative in “Malcolm’ s Katie” : House vs Home by Morgan Kerr

Feminine Isolation: Women Behind the Bars of Society & Literature by Tehya Laporte

Man’ s Need: How Android Women are Represented, contra Human Women in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Sura Jasim

Theatre 2202G

Written by Anna Oliveira Professor Solga

Since the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report in 2015, land acknowledgements (LAs) have gained prominence in Canada as a means of recognizing and honouring Indigenous peoples and their traditional territories However, despite their intended purpose of fostering reconciliation and connection, many current LA practices are criticized for being formulaic, impersonal, and lacking depth in historical context This essay explores the inherent limitations of these acknowledgements, particularly in relation to immigrant and refugee populations who may experience confusion, detachment, and complex feelings about their meaning By analyzing the relationship between newcomers and LAs within the broader framework of settler-colonialism, I argue that for these acknowledgements to be effective, they must evolve beyond mere formalities into reflective, educational performances that invite meaningful engagement and understanding. Ultimately, this essay proposes actionable steps for reframing land acknowledgement performances as powerful tools for education, solidarity, and collective responsibility toward Indigenous issues in contemporary Canada

Notably, since the release of Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report in 2015, land acknowledgements have become progressively popularized across Canada These acknowledgements can be met in various forms (e g , signs in buildings, pamphlets, social media posts, email signatures), but a vast portion of present-day land acknowledgements are delivered through speeches or brief oral remarks Through these forms of spoken declarations, LAs have become a common feature of public events, institutional gatherings, and civic spaces in Canada throughout the past decade. Their established goal is to recognize and honour the traditional territories and Indigenous peoples who have lived on the colonized land, and they aim to contribute to reconciliation efforts However, land acknowledgements notably face limitations in accomplishing their goals, many stemming from their standardization as a practice LAs frequently appear formulaic, detached from any historical context, highly impersonal, and procedural This happens because they are often a product of thoughtless reproduction and simple memorization, and are disconnected from the speaker

and the audience. An example of this is how public institutions and organizations often rely on generic scripts that simply name the Indigenous nations on whose lands an event is taking place While these statements recognize Indigenous presence, they often fail to explain the histories of dispossession and resistance that have shaped those lands and to critically reflect on the true relationship between the speakers and those displaced/dispossessed peoples This represents a critical distancing from what Robinson et al define as the true act of acknowledgement: “To acknowledge Indigenous territories and lands that we are guests upon (and often as uninvited guests) is to begin to name specific histories of colonization and continued non-Indigenous occupation of Indigenous lands” (20)

As a result of this deficit in addressing key elements that compose a “true acknowledgement,” Robinson et al argue that such LA practices tend to result in passive discourses by presenting historical facts without demanding further engagement from the speaker or audience (20–21). Moreover, the way land acknowledgements are performed can further dilute their impact Many speakers read them mechanically, treating them as obligatory statements rather than meaningful acts of recognition This tendency reduces acknowledgements to bureaucratic formalities rather than opportunities for reflection and action In some cases, LAs can even serve to ease settler guilt without requiring any substantive commitment to change Because of this detached, impersonal, and formulaic approach largely observed, land acknowledgements fail to fully achieve their goals Furthering these complications, another major shortcoming of current LA practices is their failure to acknowledge the diverse positions of their audience members Many acknowledgements are written from the perspective of long-established settlers but do not account for the experiences, perspectives and relationships of newcomers to that land who may not yet understand their place within Canada’s colonial landscape This happens because incoming immigrants and refugees often receive little to no education about Indigenous peoples upon arrival In this context, land acknowledgements are often the first (and sometimes only) exposure newcomers have to Indigenous history However, if these acknowledgements remain perfunctory and impersonal, they do little to bridge the gap in understanding Instead, this ineffectiveness of LAs risks

reinforcing a sense of detachment and confusion, given that when newcomers hear those land acknowledgements, they may not fully understand their meaning or relevance. Although many immigrants and refugees come from countries with their own histories of colonialism and displacement, the integration process in Canada does little to connect those experiences with the ongoing impacts of settler-colonialism in the country they are settling into For that reason, newcomers can have difficulties understanding both the context of Canada’s colonial history with Indigenous peoples and understanding where they, as incoming populations, “fit” into that scenario What is their relationship to the Indigenous peoples and the settler-Canadians? Are they included in the category of “settlers”? What is their position on the issues of displacement in that land? What is their relationship to these words being spoken?

The Newcomer as a Settler

To understand the complex relationship of newcomer populations (immigrant and refugee) with the current standard of land acknowledgements in Canada, we must first situate them within the broader framework of settler-colonialism

Unlike other forms of colonialism, settler-colonialism is not defined simply by the extraction of resources from a land, but by the permanent occupation of that land and the erasure of sovereignty of Indigenous populations Regarding the settlercolonialist relationships, Snelgrove et al argue that all nonIndigenous peoples residing in settler states are complicit in this system, regardless of their intentions for settling there (5–6) This position is supported by the fact that settlercolonialism is not simply an individual act, but a structural process that relies on the dispossession and denial of selfgovernance of Indigenous peoples (Snelgrove et al , 7) However, complicity in this process of settler-colonialism is not experienced equally by all non-Indigenous people; Saville highlights that many immigrants and refugees arrive in Canada with their own histories of marginalization, displacement, and colonial violence (Saville) In fact, some come from countries still grappling with the legacies of European imperialism, while others flee regions where colonial borders and policies have contributed to conflict, instability, and economic hardship (Saville) For these individuals, coming to Canada seeking safety and opportunity, the idea of being categorized as “settlers” may feel unsettling or contradictory As one immigrant reflects, in Nobe-Ghelani’s testimony, “Colonialism here and colonialism back home are not separate I came here because of colonialism, but I see colonialism here too I find myself stuck with colonization” (25) Despite these complexities, newcomers to Canada are rarely provided

with the tools to understand their relationship to Indigenous peoples. As Aslam et al. point out, most immigrant integration programs focus on language acquisition, employment, and cultural adaptation, but offer little to no education on Indigenous history and contemporary realities This lack of information and guidance contributes to creating what NobeGhelani highlights as the “perfect strangers” to Indigenous issues: newcomers who are encouraged to integrate into Canadian society without ever critically engaging with its colonial foundations (25)

In the face of all these limitations observed in the current employment and performance of land acknowledgements, it is evident that changes in these processes are needed to fully accomplish the proposed goal of LAs As Robinson et al propose: “There is a need to move beyond the mere “spectacle” of acknowledgement as a public performance and actually question the relationship between the speaker and the Indigenous peoples of that land” (21). Instead of serving as empty recitations, land acknowledgements must be restructured as performances that encourage deep and personal reflection, while engaging with the history of settlercolonialism and its impacts today These changes would allow newcomer populations to gain more understanding, respect, and connection with the land they are arriving in as well as with the Indigenous populations who hold ancestral ties to it For LAs to be effective, they must go beyond scripted declarations They should function as reflective, interactive, educational tools that foster deeper understanding and solidarity building This therefore includes a shift from more expository acknowledgements (which simply state facts, list names, and declare acknowledgement) to explanatory acknowledgements (which provide historical context, invite reflection, and propose concrete actions) This way, instead of operating as mere protocol and impersonal speech, land acknowledgements could be helpful performative tools providing opportunities to educate, build relationships, and create a shared understanding of history and responsibility towards the land that is being acknowledged Furthermore, Nobe-Ghelani argues that another important shift involves making land acknowledgements more participatory, encouraging collective engagement in critical reflection about the meaning and practice of newcomer integration and settlement (27–28) In Practice

To put this commitment to a true acknowledgement in practice, rather than treating LAs as static statements delivered by a single speaker, events could incorporate moments of reflection where audience members are asked to consider their own relationship to the land such as: How 8

did I come to live on this land? What histories of displacement, oppression, or migration shape my journey to Canada? How do these histories connect to Indigenous experiences of colonization here? How can I engage in supportive actions of the Indigenous populations from this land? Additionally, land acknowledgement practices could also serve as tools to question the negligible information/education provided to newcomers about Indigenous history, culture, geography, and resistance in the territory of Canada Furthermore, LAs could incite critical reflection about pre-established notions of land ownership and national belonging that newcomers may carry in relationship to generational settlers and the Indigenous peoples of this land; thus, constructing a stronger understanding of what we call “Canada” as inherently Indigenous land Ideally, as Robinson et al argue, this commitment to a true acknowledgement should also introduce matters such as treaty education and the history of colonial oppression of Indigenous populations, such as their forced displacement and the establishment f residential schools. Alongside that, revitalized la acknowledgements should indicate possibilities of person engagement and action to audience members This cou include: incentivizing people to discover, connect, a contribute to Indigenous-led businesses; familiarizi themselves with Indigenous storytelling and literature; attending cultural events such as educational workshop artisan markets, or powwows that are open to gene audiences Finally, for LA practices to truly carry out th intended function in Truth and Reconciliation efforts, th must call for personal and collective commitment Indigenous visibility and resistance This could be assert by listening to activist voices to learn about crucial ongoi political stakes for Indigenous peoples and engagi accordingly by uplifting their claims, sharing informatio and supporting protests By framing la acknowledgements as moments of critical self-reflecti and learning, those practices would challenge both settle and newcomers to engage with settler-colonial histories a Indigenous sovereignty in an active way Ultimate foregrounding possibilities of personal support a engagement with Indigenous peoples cultural economically, and politically would carry out the practice land acknowledgements beyond the restricted moment o speech

Conclusion

In conclusion, current forms of land acknowledgements not fully accomplish their purpose of providing reflectio honouring, and connecting with the historical settle colonial oppression faced by Indigenous people Furthermore, the inefficiency of LAs is heightened in

relationship to immigrant and refugee populations in Canada since those newcomers, not often provided information elsewhere, can experience detachment and confusion about what is being addressed shallowly and impersonally in those speeches. Because of this, it is important that LAs function as performances providing moments of education, personal reflection, solidarity, accountability, and understanding of one ’ s own position within the context of settler-colonialism in Canada Through this reframing, land acknowledgements could help newcomers recognize that their integration into Canada can also be an opportunity to engage in shared learning, solidarity, and decolonial action Ultimately, land acknowledgements must be more than words: they must be performances of responsibility, with statements that call for education, relationship-building, and tangible steps toward justice By embracing this approach, Canada can move beyond empty acknowledgements and toward a more equitable, shared future

Great Global Books 3303F

Written by William Rodrigues

Fyodor Dostoevsky's Notes from Underground is a philosophical and psychological narrative that critiques the rationalist ideals of the Enlightenment. The novel is set amidst the intellectual climate of nineteenth-century Russia, where Enlightenment ideas of reason and progress were deeply influential Nevertheless, Dostoevsky radically rejects the belief that human nature can be governed by logical principles The novel's narrator, the Underground Man, is a disillusioned former civil servant whose existence renounces Enlightenment ideals He exists in a paradoxical state between desire for self-assertion yet is incapable of meaningful engagement with society Rather than embracing reason or social advancement, he chooses a life of isolation The Underground Man gravitates toward irrationality, self-sabotage, and an embrace of suffering This essay argues that Dostoevsky’s portrayal of the Underground Man critiques the Enlightenment ideal of rationalism by revealing its inability to fully grasp the complexities of the human soul. Through the Underground Man’s paradoxical actions and self-destructive behavior, Dostoevsky illustrates that authenticity and true selfknowledge emerges from an irrational, often painful engagement with the self Firstly, the novel’s introductory lines, “I am a sick man I am a spiteful man, ” immediately establishes the Underground Man’s bitterness and dissatisfaction with his existence (Dostoevsky 7) This assertion directly confronts the rational ideals of the Enlightenment Throughout the narrative, the Underground Man articulates a deep disdain for a society that values logic, productivity, and personal advancement He is trapped in a state of existential dissatisfaction, rejecting the very principles that were supposed to lead to human fulfillment In rejecting these ideals, the Underground Man casts himself into a selfimposed exile from society. This refusal to conform is his way of asserting a more authentic form of selfhood, unrestrained by rationality He directly critiques these ideals in his assertion that “to act rationally is a matter of calculation, and man ’ s nature refuses to conform” (8) This statement directly challenges the Enlightenment assumption that individuals naturally seek rational selfadvancement Argued by Joseph Frank, in Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time, the Underground Man is “conceived as a parodistic persona whose life exemplifies the tragic-comic impasses resulting from the effects of such influences on

Dr John Hope

the Russian national psyche” (Frank 416) Frank’s interpretation situates the Underground Man as a symbolic representation of broader societal tensions in nineteenthcentury Russia, where Enlightenment rationalism was incompatible with the emotional and psychological realities of individuals By framing the Underground Man as a “parodistic persona, ” Frank emphasizes how the character’s intellectual self-awareness and moral superiority is undermined by disillusionment and stagnation that prevents any meaningful action The Underground Man’s claim that “I am a man of great intellect, but I have no power over myself,” is a manifestation of this paradox (Dostoevsky 38) The Underground Man’s self-awareness of his flaws amplifies his impotence and inner torment While he possesses self-awareness, his inability to act reveals the futility of attempting to apply rationality to the complexities of human nature

This critique of rational philosophy is further affirmed by James P. Scanlan in his article “The Case against Rational Egoism in Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground.” He argues that the Underground Man “ can easily be viewed as a sheer irrationalist whose rejection of Rational Egoism is a tortured emotional outburst with no logical credentials” (Scanlan 549) This view affirms how Dostoyevsky challenges the philosophy of rational egoism, as the Underground Man consistently avoids seeking the most beneficial outcome for himself For example, when the Underground Man is offered a promotion, an opportunity that would seemingly improve his social and professional standing, he rejects it Rather than seizing a rational opportunity for advancement, the Underground Man rebels against the utilitarian logic that defines success materially, embracing instead a life of purposelessness and suffering In this rejection of personal advancement the Underground Man asserts his individuality through selfdestructive means. As the Underground Man asserts, “Suffering is the sole origin of consciousness” (Dostoevsky 34) This declaration captures Dostoevsky’s belief that authentic self-knowledge emerges not from detached reasoning but from confronting the irrational and painful aspects of human experience Accordingly, the Underground Man’s rejection of the promotion represents a deeper condemnation of rational egoism Instead of pursuing logical outcomes, the morally flawed character seeks suffering, believing it to be the source of greater

Furthermore, the Underground Man’s interactions with others expose the limitations of reason in understanding the complexities of human nature For instance, the Underground Man’s encounter with the officer in the street reveals his obsession with social validation and superiority, despite his professed disdain for societal norms. Although he is aware the officer is oblivious to his presence, the Underground Man’s irrational desire to assert his superiority overwhelms him He describes his hollow victory, writing: “I had put myself publicly on an equal social footing with him I returned home feeling that I was fully avenged for everything” (Dostoevsky 9) Despite feeling ‘avenged’ by this interaction, the Underground Man gains no personal advancement in the social order as the officer never acknowledges him Dostoevsky emphasizes the futility of the Underground Man’s desire for revenge and recognition, reinforcing Elena Namli’s argument in “Struggling with Reason: Dostoevsky as Moral Theologian” that “Only volition can cause human action, and there is no proof for the idea that free will always chooses guidance by reason ” (199) Consequently, the Underground Man’s erratic behaviour reveals the irrational and unpredictable nature of human desires. His longing for acknowledgment, despite his disavowal of societal norms, further exposes the inadequacy of reason as the ultimate explanatory force for human action

Likewise, Gary Saul Morson in “Paradoxical Dostoevsky” reinforces how paradoxical logic governs the Underground Man’s actions Morson notes how the narrator “praises the advantage of disadvantage, the benefit of harm, the selfgratification of self-inflicted pain, the exaltation of humiliation, and numerous other variations on the logic of deliberate spitefulness” (484) This is evident during the farewell dinner for Zverkov, a former schoolmate who the Underground Man simultaneously despises and envies Despite his disdain for Zverkov’s superficiality and societal success, the Underground Man actively seeks an invitation to the dinner, driven by a conflicting desire for recognition and validation. This act of deliberately placing himself in an antagonistic and humiliating situation exemplifies the “logic of deliberate spitefulness” that Morson identifies (484) During the dinner, the Underground Man drinks excessively, alienates the group with his awkwardness, and lashes out in a clumsy attempt to assert moral superiority His bitterness escalates into an embarrassing outburst: “I was overcome by a desire to insult them all at once, and at the same time to apologize to each one of them” (Dostoevsky 39) This dual impulse of aggression and contrition demonstrates the contradictions in his psyche The Underground Man’s humiliation reaches its peak when

the other attendees mock him and leave the table without taking him seriously However, this degradation is a form of moral triumph for him: by enduring this experience, he confirms his superiority over what he perceives as the superficiality of societal norms The Underground Man’s suffering, while excruciating, serves as a source of distinction, affirming his separation from the “complacent masses ” who conform to societal expectations.

Finally, Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground also offers a theological critique of Enlightenment rationalism, emphasizing the moral and existential struggles that define the human soul

As Emily Lehman argues in “Demons and the Heart in Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground,” the Underground Man’s defiance of rational ideals is entrenched in a theological conflict between faith and doubt; this conflict both shapes his moral responses and his understanding of humanity This is demonstrated in the Underground Man’s relationship with Liza, a young prostitute whose vulnerability challenges his worldview Initially, he seeks to assert dominance over Liza, exploiting her vulnerability to reinforce his own sense of superiority However, when Liza responds with unexpected compassion and offers him genuine connection, the Underground Man recoils, exclaiming, “Can a man who knows the truth respect himself?” (Dostoevsky 18). This question reveals the depths of the Underground Man’s inner turmoil as his ultimate rejection of Liza originates from his ingrained fear of vulnerability and redemption By highlighting yet another refusal for selffulfillment, Dostoevsky critiques the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason as a sufficient guide to understanding the complexities of the human soul The Underground Man’s declaration that “ man is sometimes extraordinarily, passionately in love with suffering,” captures his belief that true selfknowledge and authenticity arise through the painful confrontation with one ’ s flaws and contradictions (Dostoevsky 34) In rejecting Liza, the Underground Man endures a theological rejection of redemption and the possibility of transcending suffering Moreover, Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground draws from theological themes of personhood, freedom, and willpower to challenge rationalist ideologies James McLachlan argues, “For the underground man, the will is capricious. His consciousness of his capricious will plunges him into the vortex of possibilities He spends his days imagining a host of wonderful dreams without actualizing any of them” (91) This observation highlights the Underground Man's existential struggle with the burden of choice and the paralysis that accompanies his awareness of personal freedom Theologically, this crisis reflects the tension between human autonomy and divine grace, with Dostoevsky portraying the Underground Man as caught

between the allure of self-determination and the despair of its inherent futility. Th tormented by the vast pote will Nevertheless, the U this freedom often drives h free, and therefore I a Accordingly, freedom bec confront the immense resp comes with it; an existentia Enlightenment ideals of embracing suffering r Underground Man rejects reason and affirms the the through confrontations w suffering becomes a theolo that humans cannot achiev alone Ultimately, Dosto portrays the human quest paradoxical, and often p reduced to rational analysis

Through the character Dostoevsky illustrates the the complexities of the h self-knowledge can only insight, personal revelatio one ’ s inner contradictions ideals of rational autono challenges the belief that understanding of the self to authenticity requires em shape human existence, n painful this journey may Underground Man’s strugg the search for truth is no but a deeply personal an transcends the boundaries

GSWS 2170B

Introduction

Written by Shely Kagan Professor Katrina Younes

In the realm of cultural discourse, Afrofuturism has emerged as a captivating and dynamic movement, offering a visionary lens through which to explore the experiences and aspirations of the African diaspora Coined by cultural critic Mark Dery, Afrofuturism is defined as "speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of 20th-century technoculture" (136) At the forefront of this movement stands Janelle Monáe, whose work serves as a pioneering exploration of Afrofuturism and the concept of temporality within it Through her artistry, Monáe navigates themes of memory, identity, and resilience within a framework unbounded by traditional notions of time and space This paper delves into Monáe's "Dirty Computer" as a case study to examine how she utilizes Afrofuturist aesthetics to disrupt and reshape our understanding of temporality By analyzing Monáe's opening monologue, as well as one of the opening scenes in relation erasure and traces, we aim to explore the ways in which her work challenges and redefines notions of time within Afrofuturism Through this exploration, we seek to uncover the deeper implications of temporality in Afrofuturist thought and its significance in contemporary cultural discourse

Temporal Liberation: The Inevitability of Change

In the opening scene of "Dirty Computer," Janelle Monáe's monologue delivers a stark indictment of a society that enforces conformity through the concept of being "dirty" for exhibiting any form of difference or opposition The line, "You were dirty if you showed any form of opposition at all And if you were dirty It was only a matter of time," (Monáe 0:18-0:24) resonates profoundly with the overarching themes of the film, particularly regarding the fluidity of Afrofuturism The emphasis on the phrase, "It was only a matter of time," serves as a potent commentary on the inevitability of change and transformation In the context of the oppressive society depicted in "Dirty Computer," this phrase suggests a recognition that systems of oppression are not sustainable long term Despite the regime's attempts to suppress individuality and dissent, there is an implicit acknowledgment that resistance is inevitable and that change will eventually come This notion aligns with Afrofuturism's emphasis on the cyclical nature of history and its belief in the potential for liberation and renewal Moreover, the deliberate use of the word

“time” (Figure 1), appearing alone on the screen in yellow letters, underscores its significance within the narrative By isolating this word and presenting it in yellow, reminiscent of cautionary signage, Monáe draws attention to the fluidity and elasticity of time, a central theme within Afrofuturism Ytasha Womack’s characterization of Afrofuturism as “ an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation” offers deeper insights into the transformative potential of it as a tool for social critique and reclamation within the African diaspora (6). In “Dirty Computer,” time is not a linear progression but a complex, nonlinear entity characterized by loops and cycles that intersect and influence each other The isolated appearance of “time” in yellow serves as a visual cue prompting viewers to contemplate the oppressive nature of temporal constraints In the dystopian society depicted in the film, time is not merely a neutral force but a tool wielded by those in power to maintain control and suppress dissent The cautionary yellow hue of the word “time” suggests a sense of foreboding, signaling the dangers inherent in rigid adherence to temporal norms Just as the regime in “Dirty Computer” labels individuals as “dirty” for deviating from societal norms, the presentation of time in yellow evokes a sense of warning, highlighting the potential consequences of resisting temporal conformity This emphasis on the fluidity of time also speaks to the broader Afrofuturist tradition of reimagining history and reclaiming narratives In “Dirty Computer,” time becomes a site of resistance against oppressive power structures. By challenging traditional notions of temporality and emphasizing the nonlinear nature of time, Monáe invites viewers to reconsider their understanding of history and the ways in which it shapes the present and future; temporal oppression is pervasive and insidious, lurking beneath the surface of society and perpetuating cycles of inequality and injustice

In Janelle Monáe’s “Dirty Computer,” one scene stands out as a profound meditation on the themes of erasure, memory, and identity within the context of Afrofuturism This pivotal moment occurs when the main character, Jane 57821, an android, undergoes deliberate memory erasure, effectively stripping away aspects of her identity (Monáe 3:20-4:09) The act of erasure serves as a powerful allegory for the systemic erasure of marginalized voices and histories within society; a phenomenon all too familiar to those who have

been marginalized throughout history However, particularly striking in this scene is the resilience of memory despite attempts to suppress it As Hill-Jarrett suggests, “The imagination also exists on a temporal plane in that it can be oriented toward past happenings, alternative presents, or possible futures” (Hill-Jarett) This analysis emphasizes the dynamic nature of memory and imagination, which extends beyond the constraints of linear time. It underscores how memory serves as a tool for both preserving the past and envisioning alternative narratives and possibilities, even in the face of erasure Thus, Hill-Jarrett’s insight enriches the understanding of Monáe’s work by highlighting the interplay between memory, imagination, and resistance against oppressive forces

In this scene (Figure 2), the camera is positioned behind the two white male scientists performing the erasure This angle gives viewers an impression that they are witnessing something private or something not intended to be seen As observers, we are granted access to the intimate act of erasure, which heightens the sense of intrusion and discomfort Monáe therefore implicates us in the act itself and challenges us to confront our complicity in systems of oppression Through the erasure of the androids’ memories, Monáe confronts the viewer with the harsh reality of systemic erasure. The memory serves as a potent symbol of the erasure cultures, histories, and identities; a process that co perpetuate systemic inequality to this day This ana depth to Hill-Jarrett’s exploration of memory and im revealing how Monáe utilizes cinematic techniques portray the erasure process, thereby reinforcing the resistance

However, despite the attempt to erase these memor of them persist, challenging the notion that erasure truly be complete As Jane 57821’s memories are systematically erased, viewers watch this occur, and audiences themselves form memories of the android’s memories, creating an additional layer that expands beyond temporality We, as viewers, watch as her memories are taken away: in her m they cease to exist, but in ours they have just been ne created. The audience maintains Jane 57821’s memories realities remembering not only her original experiences, her experience when erasing them These traces are not me vestiges of the past but rather active agents in shap narratives of resistance and resilience In preserving reclaiming these traces, the audience itself asserts agency o their own identities and histories, challenging domin narratives of erasure and marginalization Conclusion

case study within Afrofuturism illuminates profound insights into the nature of temporality, memory, and resistance Through Monáe’s masterful storytelling and use of Afrofuturist aesthetics, we are prompted to reconsider our understanding of time as fluid and nonlinear, challenging the oppressive temporal constraints imposed by society The allegorical portrayal of memory erasure underscores the systemic erasure of marginalized voices and histories, yet also emphasizes the resilience of memory in shaping narratives of resistance and resilience As viewers, we are implicated in the act of erasure, urged to confront our complicity in perpetuating systems of inequality However, the persistence of traces serves as a powerful reminder of our agency in reclaiming narratives and identities Ultimately, “Dirty Computer” invites us to envision alternative futures and narratives, guided by the principles of liberation and collective empowerment; a testament to the transformative potential of Afrofuturism in shaping contemporary cultural discourse Through Monáe’s work, we are challenged to imagine and strive for a world where temporal liberation and memory resilience pave the way for a more just and equitable future

The examination of Janelle Monáe’s “Dirty Computer” as a

English 2071G

Written by Purushoth Megarajah

Science fiction provides a potent playing field for questioning the essence of humanness and studying ways to push its boundaries; the introduction of gendered dynamics within science fiction narratives provides opportunities to theorize radical futures while actively examining the presence of gendered constructs in present society. Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 cult-classic film Ghost in the Shell genders its cyborg protagonist, Major Motoko Kusanagi, in a fascinating manner that shifts between overtly feminized and masculinized throughout various elements of the film; thus, providing the opportunity to develop a nuanced reading of the role that “femaleness” plays in Oshii’s fictional universe Within this essay, I will explore the gendering of the cybernetic body through the film’s visual presentations of masculine and feminine bodies, and the implied connection between selfhood and constructed bodies, as well as provide two contrasting perspectives that transcend and reinstate traditional gender normativity

“Though the cyborg, ‘ a hybrid of machine and organism,’ may represent the final imposition of information technology as a means of social control, it may also be potentially recoded and appropriated by feminism as a means of dismantling the binarisms and categorical ways of thinking that have characterized the history of Western culture ” (Silvio 54)

The preceding excerpt is from Carl Silvio’s article, “Refiguring the Radical Cyborg in Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell, ” in which Silvio references Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and SocialistFeminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” connecting his analysis of Oshii’s film to Haraway’s paper Haraway presents two opposing visions surrounding the interplay of gender and information technology that Silvio uses to build his analysis of Ghost in the Shell: one where the advent of cyborg bodies plays a key role in furthering social control via technological interference with bodily autonomy, and another feminist reading in which the presence of cyborg bodies can dismantle gender binaries. I will build upon the foundations laid by both writers as I analyze the portrayal of feminine bodies in Ghost in the Shell

Visual design plays a key role in the film, with character design playing directly into the film’s presentation of transhumanist gender binaries Kusanagi and Batou, partners at an anti-crime intelligence department called “Section 9,” are presented as caricatures of femininity and

Professor Ariana Potichnyj

masculinity respectively, with Kusanagi drawn with a thin, hourglass figure while Batou is a lumbering, muscular character Following both Western and Japanese ideals of gender normativity, the visual form of Kusanagi’s body would traditionally be associated with passivity and sexuality, while Batou’s larger, masculine frame would take on an assertive or aggressive role These figures of maleness and femaleness are subverted when placed within the context of cybernetic advancement, however, as the constructed nature of their bodies allows a subtle reversal of roles between the masculine and feminine Batou is a mostly human body with minimal cybernetic enhancements, while Kusanagi is an artificially constructed body housing a human brain This artificial body allows Kusanagi to perform superhuman feats of strength and positions her as Section 9’s most valuable asset Within action sequences, Major consistently outshines both Gatou and other male characters with lesser cybernetic enhancements This lifts the characters out of the typical binary implications of their physical bodies onto a more even playing field in which the viewer perceives the existence of Kusanagi’s body as her means of strength, rather than a property that would traditionally feminize her and detract from her strength.

Ghost in the Shell’ s narrative applications of body modification allow for a shift in the gendered readings of the characters, specifically through the imagery of Kusanagi’s character that roots the story back into traditional gendered dynamics While Kusanagi is mostly desexualized in terms of her relations to the male characters around her, the visual presentation of her body is hypersexual, inviting the viewer to study her unhumanness in a perverse way At the start of the film, we view the construction of Kusanagi’s shell, following the process from the technical and mechanical details to the more superficial, humanoid exterior In this transition from visually presenting as a machine comprised of wires and metal parts to something more closely resembling a woman, Kusanagi’s femaleness is emphasized via shots that center her nudity, specifically following the curves of her body and her breasts Later in the film, when Kusanagi’s superhuman attributes are further emphasized, a narrative focus is placed on her artificial skin and its thermo-optic camouflage properties In fight sequences, Kusanagi often disrobes to reveal her skin and trigger its invisibility; this is an action the character is portrayed as feeling relatively detached from, resulting in shots where she

nonchalantly stands nude and visible to male characters, as well as the film’s viewer This nonchalance detaches Kusanagi’s sense of self from her body and reduces the shell to a means of fulfilling the responsibilities of her work rather than a vessel for her personhood

Even further, the masculinization of Kusanagi’s strength and superhuman form is continuously undercut by the fact that Kusanagi does not actually “ own ” her body During periods of existential, humanist introspection, most notably in a dialogue between herself and Batou, she acknowledges the interplay between her consciousness and her cybernetic body, and how her sense of self is innately tied to her employer Kusanagi mentions that although Section 9 employees are free to resign at any point, they must “give back [their] cyborg shells and the memories they hold” (Ghost in the Shell 31:48-31:53) Kusanagi’s mention of returning her memories is especially poignant, as it crafts a clearer conception of the link between the ghost and the shell, and how the two constitute a complete selfhood. Upon establishing the complex interplay between her mechanical and biological self, she ponders the nature of her selfhood further, as seen in the following excerpt: Just as there are many parts needed to make a human a human, there’s a remarkable number of things needed to make an individual what they are A face to distinguish yourself from others A voice you aren’t aware of yourself The hands you see when you awaken The memories of childhood, the feelings of the future That’s not all There’s the expanse of the data-net my cyber brain can access All of that goes into making me what I am, giving rise to a consciousness that I call me And simultaneously confining me within set limits (Ghost in the Shell 31:57-32:20)

The joining of her biological brain with the advanced capacities of her cybernetic body physically liberates her by allowing her to exhibit extreme displays of strength; but, this confines her to an experience of humanity informed through the present and past sensory perceptions of a cybernetic body designed to work for the government With the majority of Section 9 personnel portrayed as men, the ownership of Kusanagi’s shell and the manner in which that ownership affects her lived experience of the world play a key role in the narrative structuring of a patriarchal society and the subjugation of the female bodily experience within it Both the masculinization of Kusanagi’s character via her cybernetic enhancements and the forcible feminization in the portrayal of her body contribute to the very nature of the character and the state of “humanness” within this fictional world Carl Silvio asserts that, inspired by Haraway, two contrasting arguments can be made regarding the gendering of Kusanagi, one that is liberatory in nature and another that is oppressive

In expanding upon the film’s hypersexual depiction of the female form, Silvio notes a two-way directionality between the masculinization and feminization of “feminine” cyborg bodies: the film “[relies] upon many classic visual tropes in order to represent differently sexed bodies, ultimately [eliminating] or [disrupting] the significance of these tropes” (66) Silvio’s paper argues that a feminist reading of the film’s portrayal of the female body can be refuted by the fact that the visual presentation of masculine characters does not invoke the same eroticism as those of the feminine, stating that Batou’s hypermasculine features “ emerge for the viewer as a necessary part of the narrative; there is no gratuitous lingering of the camera ’ s gaze on his body in shots that seem designed exclusively for erotic enjoyment” (Silvio 66–67)

My own reading of this film applies a neutrality that I feel is present throughout all aspects of the film, from dialogue to soundtrack. Ghost in the Shell avoids asserting a distinct morality through its intentionally ambiguous narrative design, contrasting futurist cyberpunk environments with a soundtrack that utilizes organic instrumentation, as well as interspersing lengthy scenes of dialogue between relatively dialogue-free action sequences to create a great deal of “ space ” within the viewer’s experience of the film I am not asserting the belief that Oshii intended to make a film that is meant to be read through a feminist lens, but simply that the design of his work enables the viewer to build their own perspectives upon the nature of the characters and their settings Further considering the enigmatic nature of the film’s conclusion, I feel that the unstable nature of the story’s gendering provides a great deal of opportunity for viewers to apply various philosophical and social lenses to it

Building upon the contrasting gendered readings of Kusanagi’s character, the most visceral destabilization that occurs within Ghost in the Shell’ s narrative landscape is presented through the film’s antagonist, the “Puppet Master” (formally referred to as “Project 2051”) The character, initially assumed to be a cyborg capable of “ghost-hacking” the consciousnesses of other cyborg characters via their connected neural networks, is revealed to be an entirely artificially constructed lifeform This pushes beyond the film’s transhumanist themes and into posthumanism, decentering the idea of “humanness” entirely by presenting an autonomous entity capable of addressing their needs and wants from a non-human perspective The character’s lack of history within humanness and their freedom from overarching structure or imposed ownership provide a direct foil to Kusanagi and the existentialist concerns she raises Additionally, since Project 2051 is an “escaped” or “ rogue ” version of an intelligence

created by Section 6, they do not face the social confinement within power structures that Kusanagi does When presenting the artificial, and therefore biologically sexless, character, the writers place 2051 within a feminine shell, specifically that of a long-haired, blonde, thin, female body hijacked from an assembly line The character, despite being acknowledged as sexless by members of Section 9, is consistently referred to using male pronouns in discussions between characters Midway through the scene, 2051 electronically reactivates its shell by hacking Section 9’s power grid and speaks directly to Kusanagi and her peers with a low, male tone of voice This is the film’s most intense and forward deconstruction of gender and sex binaries, with the harsh contrast of a hyper-masculine voice speaking through a hyper-feminized body serving to confuse both the characters within the narrative and the viewer Because 2501’s temporary shell is implied to be sourced from an assembly line, we can extrapolate that within this fictional universe, the manufacturing of shells still follows a binary format, and utilizing this knowledge and applying it to Kusanagi’s portrayal allows us to understand the presence of sexualized, gendered portrayals within the structuring of this society Upon establishing the context of this binary society, Silvio mentions that “this scene may not represent the actual transcendence of a sexed or gendered identity, [but] it does represent the capacity of cyber-technology to confuse and disrupt its conventional deployment” (62) This ties back to Donna Haraway’s paper that Silvio refers to throughout his writing, in which she asserts the possibility of liberation from patriarchy through human interaction with technology Project 2051’s lack of humanness and their freedom from governmental ownership allows them to shift between various shells throughout the film, stripping each mechanical body of the gendered implications they may carry. The result of this is not a complete liberation from gender, as the characters in the narrative still apply a male reading to 2051, but the technical method by which they destabilize gender is one that is unique to the cyborg mechanics of this fictional universe This radical perspective can, however, be undermined by how this scene utilizes visuals of glorified violence upon the female form to drive forward its narrative Project 2051’s temporary shell is presented to the viewer as semi-destroyed and physically confined for study within a Section 9 laboratory as a dismembered, nude, female torso Following visual cues utilized in the portrayal of Major Kusanagi, the scene ’ s art direction attempts to heavily emphasize the character’s femininity through a voyeuristic lens, drawing the naked shell with gentle facial features,

flowing hair, and breasts that are prominently centred in the frame

Further, the shell remains relatively emotionless and still, aside from grotesque twitching, with its mouth unmoving; this creates the discomforting visual of a disembodied, objectified female form governed by a male voice Through the employment of an uncomfortable, detached male gaze to drive forward tension, the narrative parallels the perspective by which Kusanagi is portrayed However, the complete lack of bodily autonomy or personhood afforded to 2051’s shell in this scene, as well as the forcibly gendered implications of a “male” voice speaking through a “female” body serve to dehumanize and objectify femaleness

Kusanagi’s and 2051’s gendered narratives interplay fantastically in the climax of the film, during which Silvio finds that Haraway’s two opposing readings of science fiction can be applied in the most scintillating manner (Silvio 62). In this extensive sequence, 2051 pursues their desire to transcend their limited digital form and experience humanness by merging consciousnesses with Kusanagi, before having both of their shells physically destroyed by Section 6 operatives The merging utilizes the biological medium Kusanagi’s brain to house 2051’s consciousness alongside her own, ultimately creating a new, posthuman joint consciousness Upon recovering the casing that holds Kusanagi’s brain, Batou implants it into a shell obtained from the black market The shell is that of a young girl and upon activation, Kusanagi’s new consciousness utilizes various voices when speaking through the new body In initially speaking through the voice of a child, and eventually utilizing the voice of their former shell, Kusanagi’s merged self exhibits a willingness to depart from the limitations of their shell; it is seen simply as a medium to physically carry their newly freed mind rather than a gendered or aged body with any association to the structures around them. While this reading of the climactic scene implies a complete liberation from gender and from the physical body in its entirety, Silvio makes note of gendering within the characters’ dialogue and how the merging of Major and 2051 can be read as an analogy for procreation and childbirth, with a distinct maternal role applied to Kusanagi (Silvio 67) 2051’s act of “entering” into Kusanagi’s physical brain may be read as an allusion to a dominant masculine role within human procreation to some extent, but their utilization of gendered language in statements such as “ you will bear my offspring onto the net itself” alludes to a strangely destabilized version of a heterosexual parental dynamic (Ghost in the Shell 01:11:4401:11:47) The placement of the merged consciousness within a child’s body only furthers this gendered analysis by asserting

Kusanagi’s body as a ma l fi d di h pregnant “carrier” of a ne Ultimately, while it does n a feminist narrative, G characters allows space analysis The transhuman presented by the film inte and media analysis in a While Carl Silvio’s artic Donna Haraway’s in 198 read through a contempo science fiction to transcen a distinct vision of the destabilizes the nature o presents an ambitious content within its 83-mi extensive presentations creating an ambiguous opportunities for reading binary and re-establish it.

English 2401E

Written by Amy Heaman

The representation of food in Zitkala-Ša’s autobiographical writing is symbolic of her removal from her indigenous community The way that eating meals is shown varies between Zitkala-Ša's experience when living with her mother in "Impressions of an Indian Childhood" and when she is away at a boarding school in "The School Days of an Indian Girl," transitioning from touching tales of interpersonal contact to stale and mechanical actions done at the request of school teachers With Kishigami Nobuhiro's work expanding Levi-Strauss's kinship theory to explain food sharing practices in small-scale societies, we can understand the cultural significance of sharing meals with community members, as seen in "Impressions," and how the removal of that cultural element effects young Zitkala-Ša, impacting her sense of self and community The representation of food tells a story that mirrors Zitkala-Ša's connection to the Dakota people As Zitkala-Ša is removed from the practices and rituals of the Dakota, she loses her connection to them and she is replaced by a colonial model of who she once was Kishigami endeavours to categorize ways of food sharing in small scale societies In his study titled "A New Typology of Food-Sharing Practices among Hunter-Gatherers, with a Special Focus on Inuit Examples," he outlines the many specific ways that societies which rely on the hunting and gathering of food engage in trade and giving to solidify social bonds. Kishigami references Levi-Strauss's theory of kinship and the several other theories that have built upon it to identify and understand the importance of sharing food in these groups The study reports "that gift exchange is a basic principle in human societies and that it is a means to forge and expand social relationships and to establish social solidarity" (342) Taken from Strauss's theory, the benefits that are connected to sharing in small scale societies reinforce the bonds within the community and can affirm one ' s place within the group Various types of sharing are carried out depending on place, time and the needs of the group but offering food can "emphasize the ethical significance of generosity" (344) Not only does the redistribution of resources help to ensure the health and welfare of the group physically, but it also promotes core values to those who engage in the practice I find practice the proper term to use in this instance because, as shown in Zitkala-Ša's writing, engaging in food sharing is a ritual of hospitality in the Dakota community she grows up in

Dr Alyssa MacLean

The importance of such food-sharing rituals is displayed in Zitkala-Ša's writing, where she remarks that "the law of our custom had compelled [him] to partake of my insipid hospitality," after serving a community member bad coffee ("Impressions") Zitkala-Ša informs the reader of the importance of food and ritual by showing food-sharing as meal scenes, vital to the existence and continuation of the Dakota community

Food-sharing is a ritual that evokes storytelling and the keeping and sharing of legends which create and sustain bonds within the Dakota society. In the second section of "Impressions," Zitkala-Ša sets up a dinner scene Zitkala-Ša as a young girl gathers elders, inviting them over for dinner with intentions of hearing the legends of the Dakota's past In this scene we see Zitkala-Ša learning the customs of the Dakota Zitkala-Ša describes her love for "the evening meal, for that was the time when the old legends were told" ("Impressions") Karen E Beardslee states that "Zitkala-Ša marks [the legend telling] as a most important ritual in itself" (101) For ZitkalaŠa, the tradition of sharing a meal with her elders is bound to the telling of legends When people are invited into your home, you provide them with food and once you have shared a meal with your guests you are free to ask them to tell you legends This progression of thought is shown by Zitkala-Ša's mother In her youth Zitkala-Ša's behaviour is corrected by her mother and the social cues that are customs of the Dakota are taught to her through her mother’s guidance. Throughout the section, her mother’s explanation of how the dinner ritual is supposed to go is prevalent Her mother is the one who sends her to invite the others over and gives strict instruction to "wait a moment" when interrupting their evenings ("Impressions") This observational instruction is active during the end of dinner when Zitkala-Ša's mother is the person to initiate the storytelling, showing her daughter the appropriate way to do so Young Zitkala-Ša treasures the retelling of the legends, it is clear in her enthusiasm about the meal Even more important is the meals function, it is a way for Zitkala-Ša to learn about herself through learning about the Dakota Zitkala-Ša is exposed to the dinner ritual, the oral history of the legends, and the values of the Dakota people through the ritual itself This knowledge imparted to her by the ritual affirms her sense of self and her identity within the community In contrast to the dinner scene in "Impressions," "School

Days" illustrates a stark change in mealtime and eating habits. Zitkala-Ša's account of her first breakfast at the residential school is bitter and uncomfortable She is alone at school and suffering a "constant clash of harsh noises" and sounds that are foreign and confusing to her ("School Days") There is a parallel of observational learning when Zitkala-Ša is trying to sit down for the meal without her mother’s presence There is no one to go first and be an example, instead the observational learning process is perverted by the school’s attempt to make her act before she has the chance to learn from the other children Overwhelmed by the new way of taking meals, Zitkala-Ša expresses that her "spirit tore itself in struggling for its lost freedom, all was useless" ("School Days") Her sense of self struggles in adapting to the new way of eating that is so fundamentally different from the way she was taught to eat Rather than listening to the elders speak with each other, waiting for the promised telling of legends, Zitkala-Ša must listen to a man "murmuring an unknown tongue" before she is even allowed to pick up her fork ("School Days"). The ritual of eating and sharing is entirely flipped backwards. Adding insult to the disruption of the meal ritual, its place in the narrative makes the trial of breakfast the preface to the cutting of her hair If the differences between the scenes were not obvious enough, the school teachers go about physically severing ZitkalaŠa's connection to the Dakota through the removal of her hair Beardslee characterizes breakfast at school as " a lesson in restraint and submission" (Beardslee 104) The submission of Indigenous children directly relates to the children being subjected to foreign, Christian beliefs and replacing their culture through the subversion and removal of their own rituals and practices After spending years away from the Dakota and her mother, Zitkala-Ša returns home in the sixth section of "School Days " In the feast scene we see the glaring disconnect of culture from not only Zitkala-Ša but many of the young Dakota The cultural annihilation done by the residential schools follows the children home. Zitkala-Ša describes the party goers saying, "They were no more young braves in blankets and eagle plumes, nor Indian maids with prettily painted cheeks They had gone three years to school in the East, and had become civilized" (“School Days”) The time that the children spend in Residential school disrupts their knowledge and severs their connection to their community When the children return home, they attempt to engage in food sharing through a feast We see an example of a proper feast through the eyes of young Zitkala-Ša in "Impressions" where we are told of the Dakota custom by which “ young Indian women [are] to invite some older relative to escort them to the public feasts " Zitkala-Ša tries to engage in this custom by asking her brother to take her but he will not

(“School Days”). Her brother, also changed by his time in residential school, refuses to perpetuate the ritual. Zitkala-Ša does her best to hold onto rituals but suffers in a liminal space of not being fully Dakota or fully assimilated to colonial culture Beardslee describes how she "recognizes the threat to her sense of self" when she rides away on the train as a young girl, and that is confirmed to her when she returns changed (103) This inability to engage in ritual also estranges ZitkalaŠa from her mother, who can only offer her a Bible, a symbol of colonialism, in the face of Zitkala-Ša’s grapple of lost identity

Throughout her life Zitkala-Ša has experienced the way that "bit by bit native habits are relinquished to Eastern influences" (Beardslee 103) Zitkala-Ša shows the reader the way that we experience life through food and extends its importance to the ritual of food sharing Chronologically, she builds the relationship between her connection to the Dakota and her connection to food, then uses food and mealtimes to showcase the destruction of her sense of self during her time in residential school Kishigami’s study on food-sharing places the roots of the practices in history and shows their significance by exemplifying the ways in which it solidifies community The solidarity of community is lost to Zitkala-Ša when she can no longer take part in the rituals, and without her community she loses a part of herself

ARTHUM 2240F

Written by Heather Stanley Professor Jeremy Arnott

Is it possible to live an utterly private life? To this question, German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt would say that “[n]o human life, not even the life of the hermit in nature’s wilderness, is possible without a world which directly or indirectly testifies to the presence of other human beings” (Arendt 22) Humans are social beings by nature, and although one might attempt a solitary existence like Thoreau at Walden Pond, one cannot escape society, from which one was born, and which has shaped the very land we inhabit Perhaps a more practical question, then, would be to ask: is it possible to keep one ’ s private and public lives entirely separate? Arendt asserts that while this may have been the case in antiquity, the line between the private and public spheres has blurred to the point that neither exists independently anymore In Ancient Greece, private life was clearly defined by the drive to sustain life Eating, sleeping, giving birth, raising children all the essential actions for survival took place in the realm of the household By contrast, the public sphere, or polls, was concerned with what were deemed man ’ s greatest capabilities: action and speech. Arendt observes “if there was a relationship between these two spheres it was a matter of course that the mastering of the necessities of life in the household was the condition for freedom of the polls” (Arendt 30–31) Under this framework, only the head of the household could be a member of public life, since he had the power to free himself from the necessity of labour, and from concern for his own life He was able to discuss concepts such as societal structure, virtue, and immortality amongst equals, as all those who participated in the polls were deemed to be Arendt pinpoints the advent of Christianity as having a major role in shifting attitudes regarding what should be made public Christianity values worldlessness, and it defines “good deeds” as charitable works done entirely in private This contradicts the long-held perspective that “[t]o live an entirely private life means above all to be deprived of things essential to a truly human life: to be deprived of the reality that comes from being seen and heard by others” (Arendt 58) I am reminded of a poem in which the author expresses a strong desire “[t]o be made whole / by being not a witness, / but witnessed” (Limón 13–15) But if the good Christian life is one of kind acts done in private, is being witnessed somehow unholy? In antiquity, this was certainly not the popular belief, as

members of the polls strove to distinguish themselves, to be remarkable and unique This begets the consideration of another major contributor to the collapse of the public and private realms: the modern view that people should conform rather than stand out.

The Industrial Revolution produced a shift in labour from a private practice to a social one The division and mechanisation of labour are the two factors that, according to Arendt, led to the acceleration of labour productivity This necessitated the new field of economics, which “could achieve a scientific character only when men had become social beings and unanimously followed certain patterns of behavior, so that those who did not keep the rules could be considered to be asocial or abnormal” (Arendt 42) While the Ancient Greek polls demanded individuality, modernity promotes predictability and assimilation Arendt astutely notes that the behavioural sciences rely on most people acting in a similar fashion; thus, it draws conclusions that are exclusionary of the exceptions, which arguably say more about human behaviour As discussed during a class on Marx, the socialization of labour also led to the perspective of labour as the source of value. Traditionally, owning private property was the prerequisite for entering public life With the new capitalist structure came a greater emphasis on private wealth “not because its owner was engaged in accumulating it but, on the contrary, because it assured with reasonable certainty that its owner would not have to engage in providing for himself the means of use and consumption and was free for public activity” (Arendt 65) Arendt disagrees with the “liberal economists” who believe the private appropriation of wealth will replace the role of private property; she argues that since jobs are controlled by society, and the exchange of money is fluid, individual wealth is constantly under threat It would seem, then, that there is no longer a clear delineation between who is “eligible” to participate in the public realm

Other aspects of the private and public spheres that were traditionally very distinct have amalgamated into what Arendt calls the social realm Action and speech are no longer exclusive to the public realm where everyone was deemed equal but are actively employed in private life

Since the hierarchical household structure of antiquity is no longer the standard, more citizens can exercise their right to free speech in a world where equality has a broader connotation

As the public realm seeped into the private, the reverse also occurred; aspects of life that promote survival are now acceptable in public Arendt notes the liberation of the working class and the women ’ s rights movement as indicators of this shift From employees picketing for liveable wages to mothers breastfeeding on a park bench, the necessities of life are no longer hidden However, the commodification of goods may perpetuate a lack of appreciation for these necessities Arendt addresses her concern that “greatest threat here, however, is not the abolition of private ownership of wealth but the abolition of private property in the sense of a tangible, worldly place of one ’ s own ” (Arendt 70) If Arendt were still alive, I believe she would cite the birth of the Internet as the conclusive death of the private and public spheres In a sense, the idea of a ‘worldly place of one ’ s own ’ no longer exists, because so much of our lives are accessible and are on display to all of society Can I even call my bedroom where I sit as I write this a place of my own, when dozens of students have lived here before me; when I am paying to rent it; when I just posted a photo of it to my BeReal app? In a world of ubiquitous connectivity, we must find ways to protect our identities, so we do not lose ourselves within the all-consuming social realm

English 2301E

Written by Elora Chambers Professor Doelman

In both Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer and Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, family dynamics and inheritance practices enforce a gendered system of economic dependence Daughters are subjected to their fathers’ wills, while sons struggle to balance familial duty with their pursuit of financial autonomy By situating these texts within the broader historical context of eighteenth and early nineteenth-century legal structures, including primogeniture, coverture laws, and marriage settlements, this essay demonstrates how economic forces shaped gender roles and personal agency. Through an analysis of marriage as a financial transaction, the economic dependence of women, the restrictions of inheritance laws, and the pressures imposed on men, both texts critique a system that conflates wealth with personal autonomy In both She Stoops to Conquer and Sense and Sensibility, marriage is presented as a transactional institution in which women are evaluated based on their dowries and social status In She Stoops to Conquer, Mrs Hardcastle prioritizes financial concerns over personal happiness, ensuring that her niece Constance marries her son Tony so she and the pair can maintain control over the family fortune: “I expect the young gentleman I have chosen to be your husband from town this very day” (Goldsmith 3) Constance’s inheritance is viewed as a resource to be controlled through marriage, reinforcing that financial independence was unattainable for women outside of wedlock. In Sense and Sensibility, John Dashwood rationalizes withholding financial support from his sisters, that their inheritance “need not be three thousand pounds,” reinforcing the idea that women ’ s financial security was secondary to male economic interests (Austen 5) Fanny Dashwood exemplifies this, asserting that “people always live for ever when there is an annuity to be paid them” (Austen 6) Mary Astell’s Some Reflections Upon Marriage critiques this commodification of women, arguing “ a woman indeed can’t properly be said to choose, all that’s allowed her is to refuse or accept what is offered” (Astell 23) Despite being written a century before Austen, Astell’s work remains relevant, as coverture laws and patriarchal inheritance structures persisted Marie-Laure MasseiChamayou asserts in “Economic and Symbolic Transmissions in Women’s Novels: Frances Burney, Jane Austen, Elizabeth Gaskell” that primogeniture “severely restricted women ’ s access to property” (Massei-Chamayou

4), and Rory Muir explains that women of the gentry were often raised to secure economic stability through marriage due to limited financial autonomy (Muir 12) Austen critiques this economic reality by satirizing men who justify their financial decisions under the guise of moral duty John Dashwood manipulates his father’s final wish into a vague obligation, claiming, “He did not stipulate for any particular sum, my dear Fanny; he only requested me, in general terms, to assist them” (Austen 5) This highlights how male figures could manipulate verbal contracts to serve their financial interests. Joyce Kerr Tarpley notes in “Playing with Genesis: Sonship, Liberty, and Primogeniture in Sense and Sensibility” that primogeniture created “ a moral paradox where those with wealth rationalized keeping it rather than distributing it” (Tarpley 90) Austen’s broader depiction of inheritance and marriage negotiations reinforces how women ’ s fates were determined by maledominated financial strategies Similarly, in She Stoops to Conquer, Kate Hardcastle recognizes the societal expectations regarding marriage and manipulates them to her advantage She acknowledges her position in the marriage market, stating, “In the first place I shall be seen, and that is no small advantage to a girl who brings her face to market” (Goldsmith 3) Unlike Constance, who remains a passive victim of marriage negotiations, Kate subverts these constraints As Brooks argues, Kate “undergoes voluntarily the reversal of class-roles” to carve out agency in a rigid social hierarchy (Brooks 38). The play critiques the commodification of women through Mrs Hardcastle’s obsession with wealth, which mirrors Austen’s concerns Mrs Hardcastle’s insistence that Constance marry Tony is less about happiness than keeping family wealth consolidated This reflects Massei-Chamayou’s argument that marriage institutionalized women ’ s bodies as “economic currency in the marriage market” (Massei-Chamayou 20)

The idea that women ’ s worth was tied to securing an advantageous marriage is reinforced by legal frameworks limiting their rights to property Austen and Goldsmith expose how these structures forced women into financial dependency through marriage By satirizing this system, both critique rigid gender roles confining women to financial dependence, revealing the limited agency they could exercise.

Economic dependence in Sense and Sensibility and She Stoops to Conquer shapes women ’ s lives The Dashwood