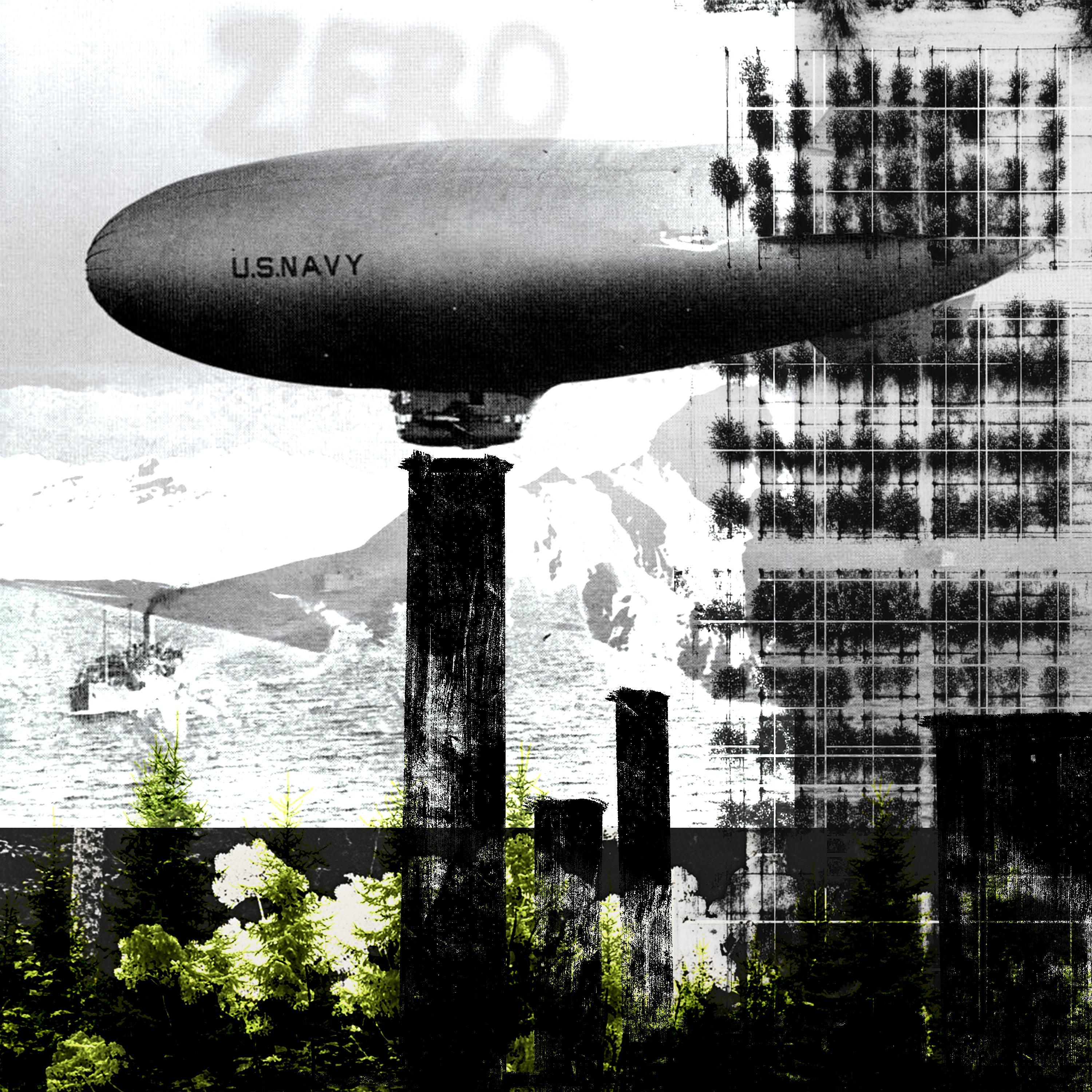

THE ZERO MOVEMENT

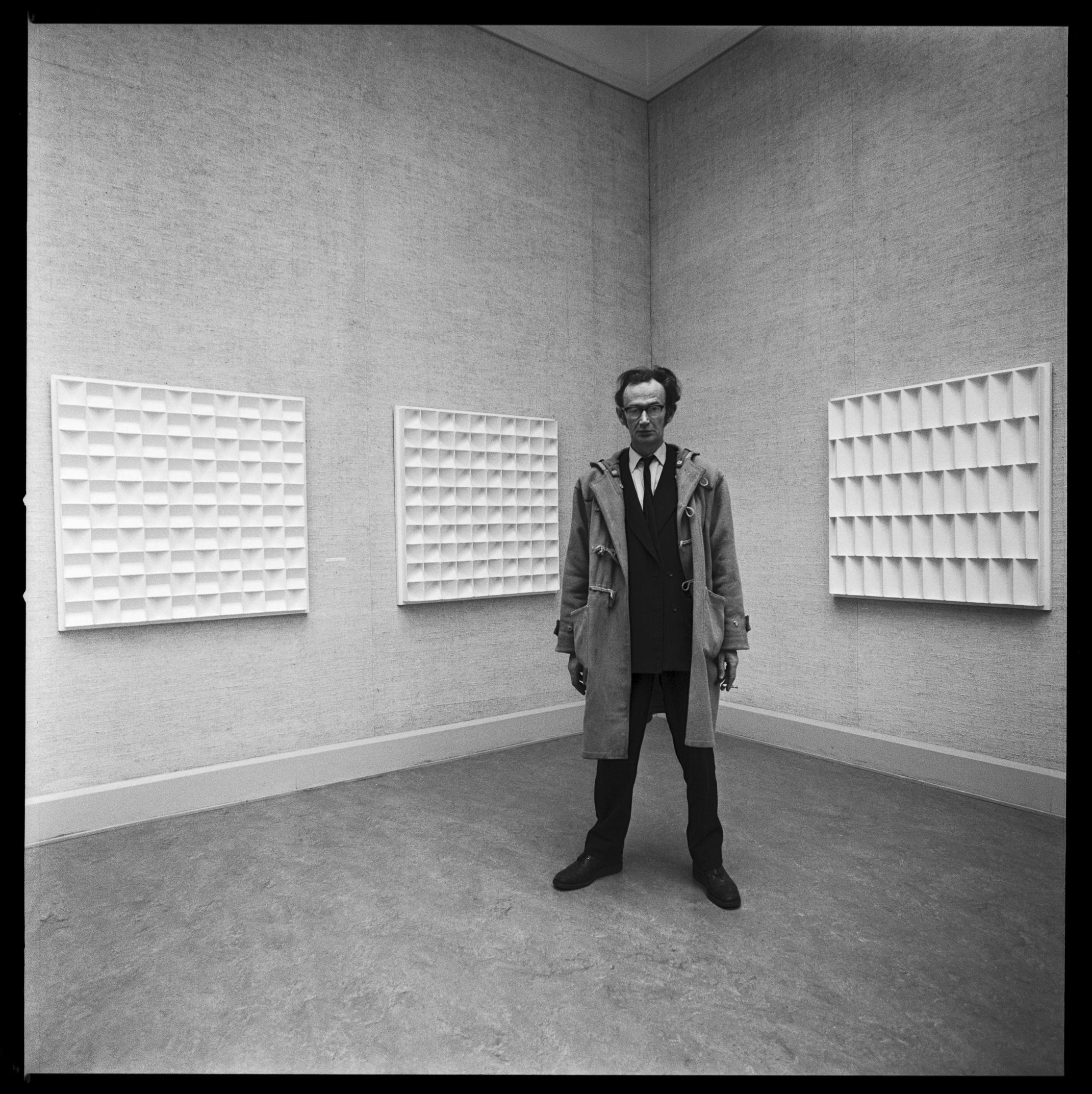

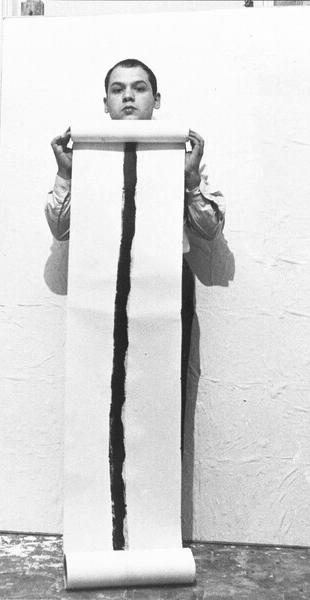

The ZERO group was formed in Dusseldorf, Germany in 1957 by Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Gunther Uecker. They approached art making by using light and motion to open up new forms of perception. Elvira Jensen wrote “ZERO wanted a better world. It was about the acceptance of the past and the potential beauty of our future.”

They explained their choice of name as follows: ZERO is a “word indicating a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning as a countdown when rockets take off - ZERO is the incommensurable zone in which the old state turns into the new.”

Growing up in post-war Germany, the artists asked themselves - the old is dead, what is next?

Art exhibitions were held in Dusseldorf at Galerie Schmela. The group published three magazines: ZERO 1 (April 1958) contained writings on color, color as light articulation, and monochrome painting. ZERO 2 (October 1958) focused on the relationship between nature, man, and technology. ZERO 3 (July 1961) was published on the occasion of “Edition, Exhibition, Demonstration” at Galeria Schmela.

In the case of Detroit, what would it look like if we approached city renewal with the same mindset as that of the ZERO Movement? Starting with a blank slate. Abandoning existing infrastructure. Allowing nature to win - as it eventually always does. What if we think backwards? What if we create a new definition of what a city will be hundreds of years in the future?

“THIS VIEW OF A LIVING NATURE IS BOTH ODD AND SAD. HERE, ETERNAL GREENNESS, YOU SEARCH ES OF MAN; YOU FEEL YOU ARE ENT WORLD FROM THE ONE YOU

AND ELECTRIC EELS”, A. VON HUMBOLDT, 2007.

NATURE WHERE MAN IS NOTHING

HERE, IN

A FERTILE LAND, IN AN

SEARCH

IN VAIN FOR TRACARE CARRIED INTO A DIFFERYOU WERE BORN INTO.”

“LIMITE

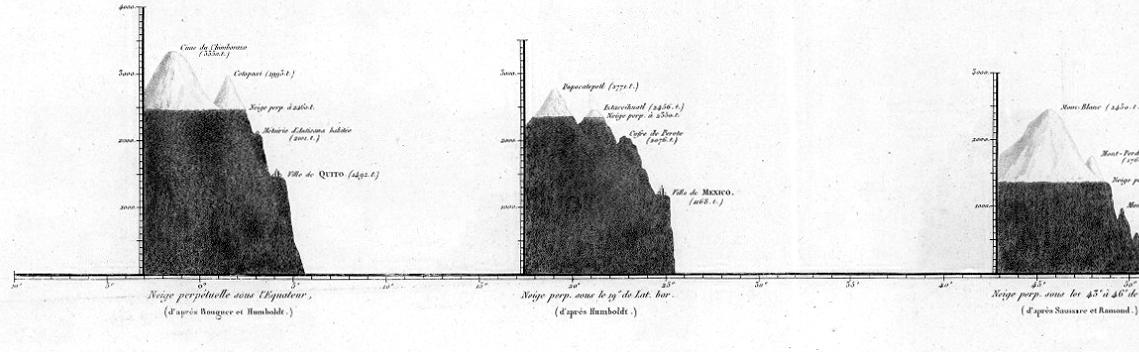

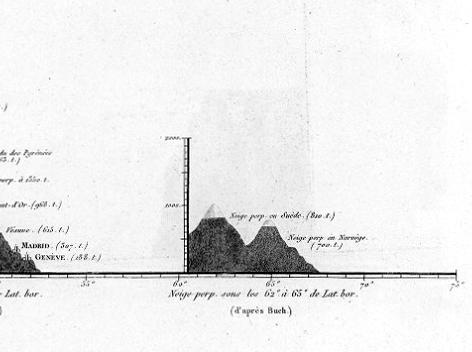

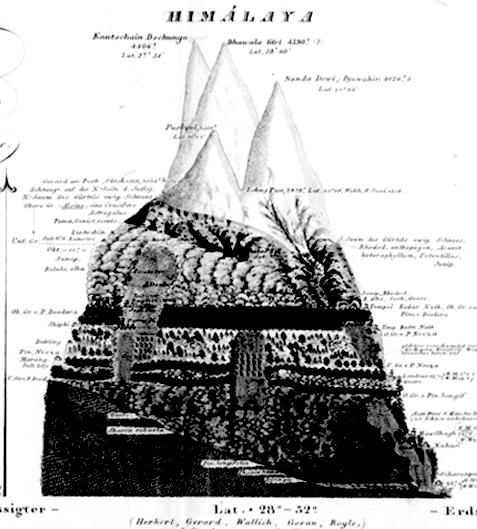

INFERIEURE DES NEIGES PERPETUELLES A DIFFERENTES LATITUDES”, A. VON HUMBOLDT, 1850.

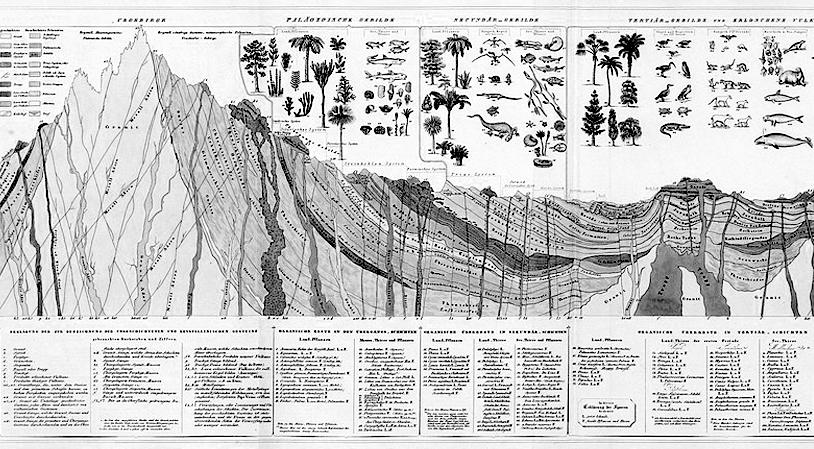

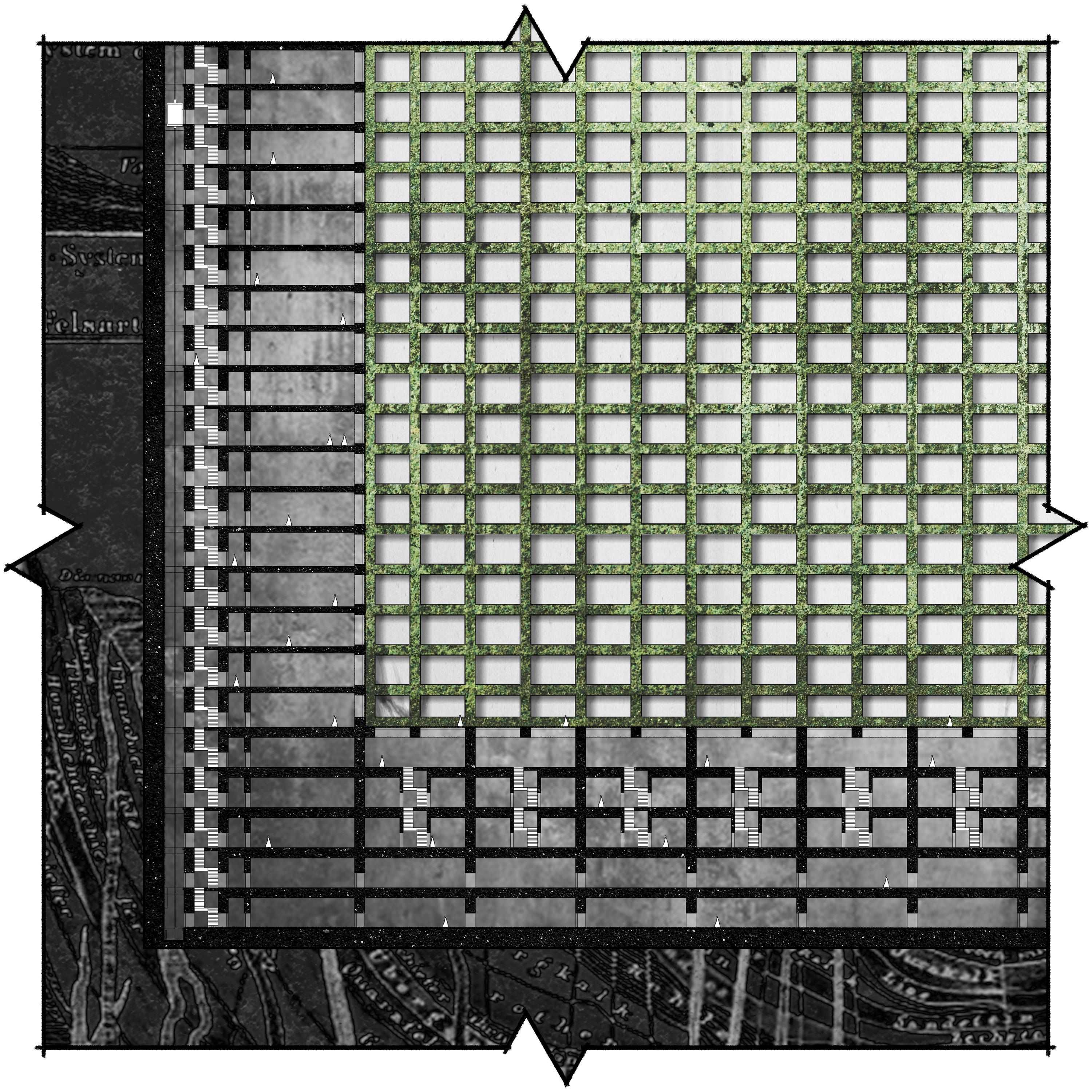

“CROSS-SECTION OF THE EARTH’S CRUST”, A. VON HUMBOLDT, 1851.

ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT

Von Humboldt was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, and explorer whose interdisciplinary work laid the foundation for modern ecology, meteorology, and biogeography. Renowned for his Latin American expeditions (1799–1804), he meticulously documented plants, animals, landscapes, and cultures, pioneering the study of species distribution in relation to geography and climate. Humboldt’s groundbreaking concept of the "unity of nature" emphasized the interconnectedness of biological, geological, and climatic processes. An early advocate for environmental conservation, he warned against deforestation and resource exploitation. His magnum opus, Kosmos, sought to unify scientific knowledge and inspired generations of scientists and artists.

“DISTRIBUTION OF PLANTS OF THE HIMALAYAS”, A. VON HUMBOLDT, 1839.

SENEY WILDLIFE REFUGE, MICHIGAN, USA.

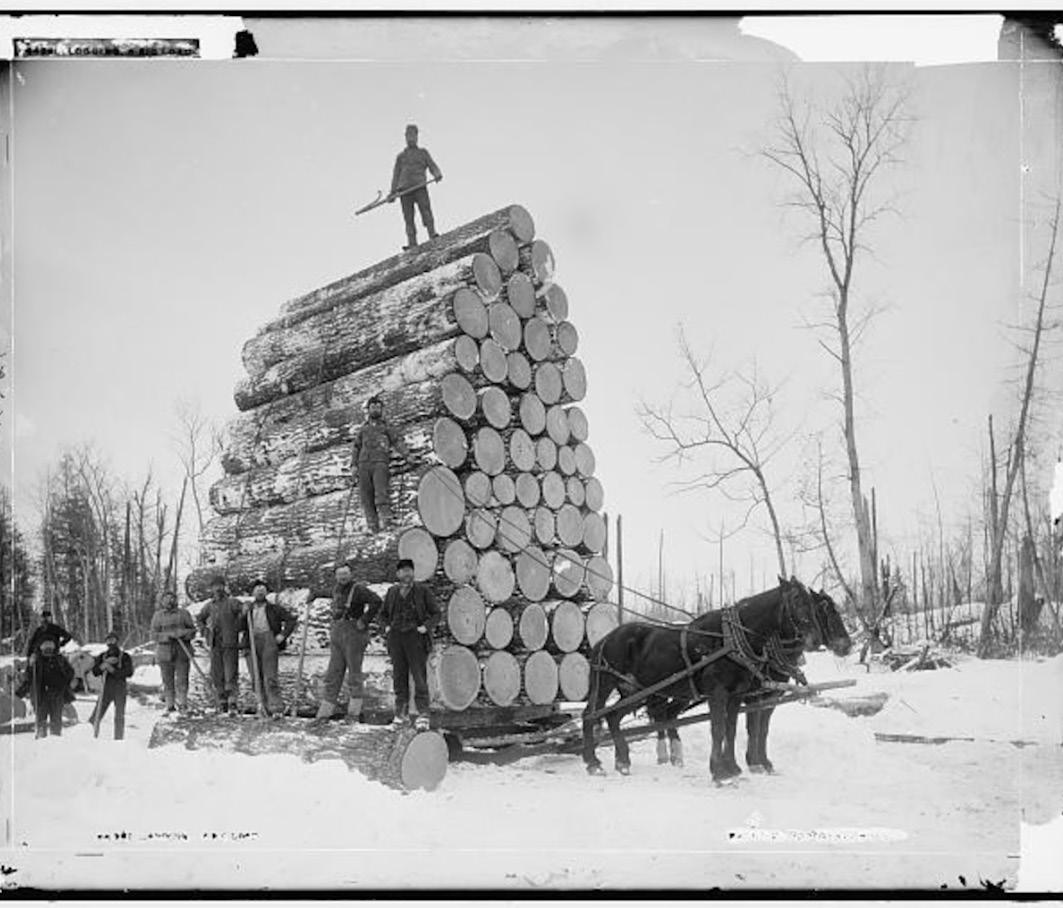

MICHIGAN'S LOGGING HISTORY

During the early to mid-1800s, Michigan’s vast pine forests attracted lumber companies. Detroit emerged as a key center for processing and distributing timber. The timber industry boomed in the 1830s and 1840s, with logs floated down rivers to mills in Detroit and nearby cities. The city’s location on the Detroit River and proximity to the Great Lakes allowed for easy shipping to other parts of the U.S. and Canada.

The period from 1860 to 1890 was the height of lumber production in Michigan, including Detroit. By the late 19th century, Michigan was the leading lumber-producing state in the U.S. The lumber mills processed white pine and other hardwoods, and Detroit became a distribution center for lumber sent to eastern and western markets via the Great Lakes and railroads.

The lumber industry began to decline in the early 20th century as Michigan’s forests were depleted, leading to deforestation and the exhaustion of easily accessible timber resources. Many of the large lumber companies moved westward, particularly to the Pacific Northwest, in search of new timber supplies. Detroit’s economy gradually shifted from lumber to manufacturing, including the rise of the automotive industry, which became the city’s defining industry by the 1920s.

While Detroit’s role in the lumber industry diminished, its early prosperity helped lay the foundation for its later industrial development.

LOGGING + MICHIGAN'S ECOSYSTEM

The sheer scale of logging operations resulted in widespread deforestation, particularly in the Lower Peninsula and parts of the Upper Peninsula. Large tracts of old-growth forests were cleared to meet the demand for lumber, which led to the loss of diverse habitats that supported numerous species of wildlife. This habitat destruction disrupted ecosystems, leading to a decline in many native species. For example, birds that relied on mature forests for nesting and food, such as the wood thrush and the black-throated blue warbler, saw their populations diminish as their habitats were lost.

The removal of trees also had repercussions for soil health and water quality. Tree roots play a crucial role in stabilizing soil and preventing erosion; without them, the exposed soil became prone to washing away, particularly during heavy rains. This erosion led to sedimentation in nearby rivers and lakes, degrading water quality and harming aquatic ecosystems. Increased sediment loads can suffocate fish eggs and disrupt the habitats of organisms like mayflies, which are indicators of healthy water bodies.

The logging process left behind vast amounts of debris, such as branches and logs, which created a tinderbox environment prone to wildfires. The loss of tree cover also meant that there was less moisture retention in the soil, further increasing the risk of fires. These fires not only destroyed logged areas but also impacted nearby unlogged forests, leading to more extensive ecological damage.

LOGGING EXPEDITION, MICHIGAN, LATE 1800s.

NATIVE TREES AND PLANTS OF MICHIGAN

DECIDUOUS: Sugar Maple, Red Maple, Eastern White Oak, Northern Red Oak, American Beech, Shagbark Hickory, Black Cherry, American Basswood, American Elm, Paper Birch, Yellow Birch, Black Walnut, Silver Maple, Cottonwood

CONIFEROUS: Eastern White Pine, Red Pine, Jack Pine, Eastern Hemlock, Northern White Cedar, Balsam Fir, Tamarack, Black Spruce, White Spruce

SHRUBS: Red Osier Dogwood, Winterberry, Common Witch-hazel, Serviceberry, Highbush Blueberry, American Hazelnut, Nannyberry, Ninebark, Black Elderberry, Buttonbush

WILDFLOWERS: Trillium, Wild Columbine, Blackeyed Susan, Purple Coneflower, Butterfly Weed, Jack-in-the-pulpit, Wild Geranium, Bloodroot, Common Milkweed, Blue Vervain, Dutchman’s Breeches, Mayapple, Virginia Bluebells

GRASSES: Little Bluestem, Big Bluestem, Indian Grass, Switchgrass, Prairie Dropseed, Canada Wild Rye

FERNS: Ostrich Fern, Sensitive Fern, Maidenhair Fern, Christmas Fern, Interrupted Fern

NATIVE ANIMALS OF MICHIGAN

MAMMALS: White-tailed Deer, Eastern Cottontail Rabbit, Eastern Gray Squirrel, Red Squirrel, American Beaver, North American River Otter, Coyotes, Gray Wolf, American Black Bear, Moose, Red Fox, Bobcat, Eastern Chipmunk

BIRDS: Bald Eagle, Sandhill Crane, Common Loon, Wild Turkey, Pileated Woodpecker, American Robin, Red-Tailed Hawk, Great Horned Owl, Trumpeter Swan, Eastern Bluebird

FISH: Brook Trout, Lake Trout, Walleye, Northern Pike, Smallmouth Bass, Chinook Salmon, Yellow Perch

REPTILES: Common Snapping Turtle, Painted Turtle, Eastern Garter Snake, Blue Racer, Eastern Box Turtle

AMPHIBIANS: Eastern American Toad, Green Frog, Spring Peeper, Spotted Salamander, Eastern Tiger Salamander

INSECTS: Monarch Butterfly, Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, Black-legged Tick, Eastern Bumblebee, Common Green Darner

OTHER: Common Crayfish, Freshwater Mussels

PINE FOREST, MICHIGAN, USA.

WHITE-TAILED DEER PRESERVE, MICHIGAN, 2024.

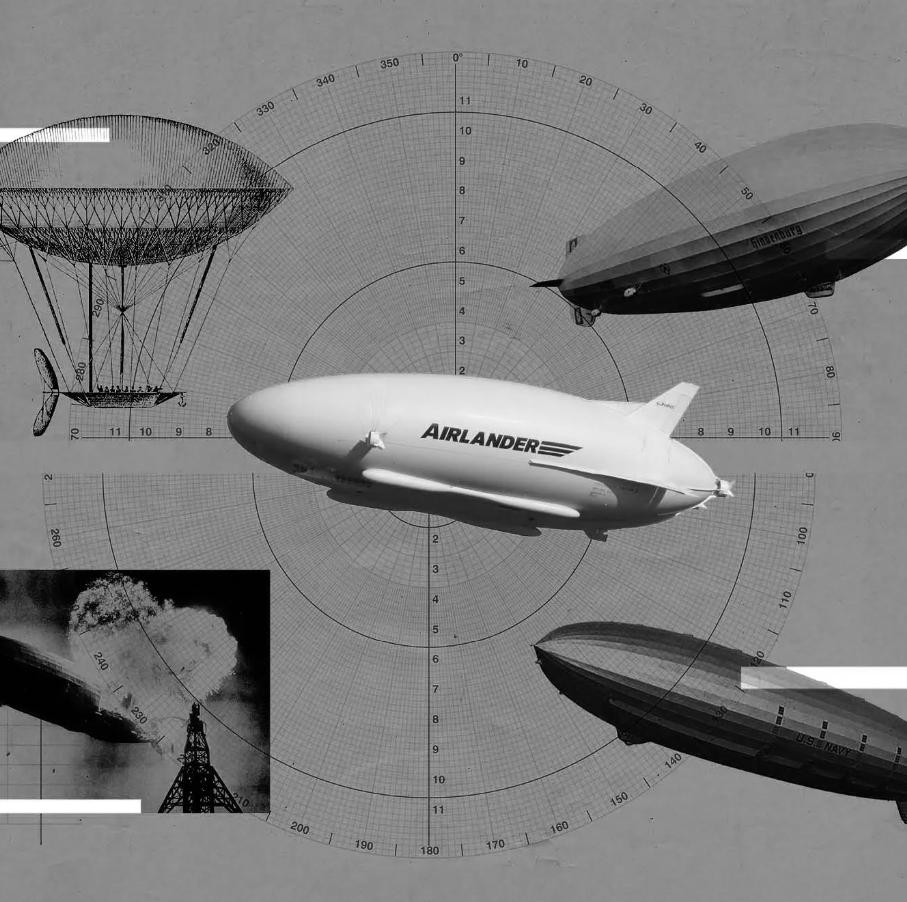

AIRSHIPS OVER PARIS, FRANCE, 1930s.

AIRSHIPS OVER MANATTAN, NEW YORK, 1930s.

USS AKRON (ZRS-4), FLYING OVER THE PANAMA CANAL ZONE, 1933.

"[AIRSHIPS] HAVE A ROLE TO PLAY IN SOCIETY MOVING FORWARD. THE HUMAN RACE IS GOING TO HAVE TO COME TO TERMS WITH THE FACT THAT WE CANNOT SPEND OUR TIME RUSHING AND TEARING ABOUT THE PLACE, IGNORING THE PLANET."

JOHN-PAUL CLARKE, 2023.

ZEPPELINS + AIRSHIPS

The use of airships for transportation reflects a niche resurgence driven by technological advancements and environmental concerns.

They are being explored for cargo transport, particularly in remote areas lacking robust logistics infrastructure. They are also gaining popularity in the tourism sector, offering unique scenic aerial tours that appeal to travelers seeking leisurely experiences and low-carbon alternatives to short-haul flights.

Technological improvements, such as lighter materials and enhanced propulsion systems, have made contemporary airship travel safer and more efficient. They will potentially be able to integrate renewable energy sources like solar panels.

The creation of a zeppelin-centric society would create a cultural “slow-down” while also providing jobs for city-dwellers. Citizens would be able to travel to far-away places with less impact on the natural environment. The scale of zeppelins would also allow more passengers and foster more of a community-driven experience.

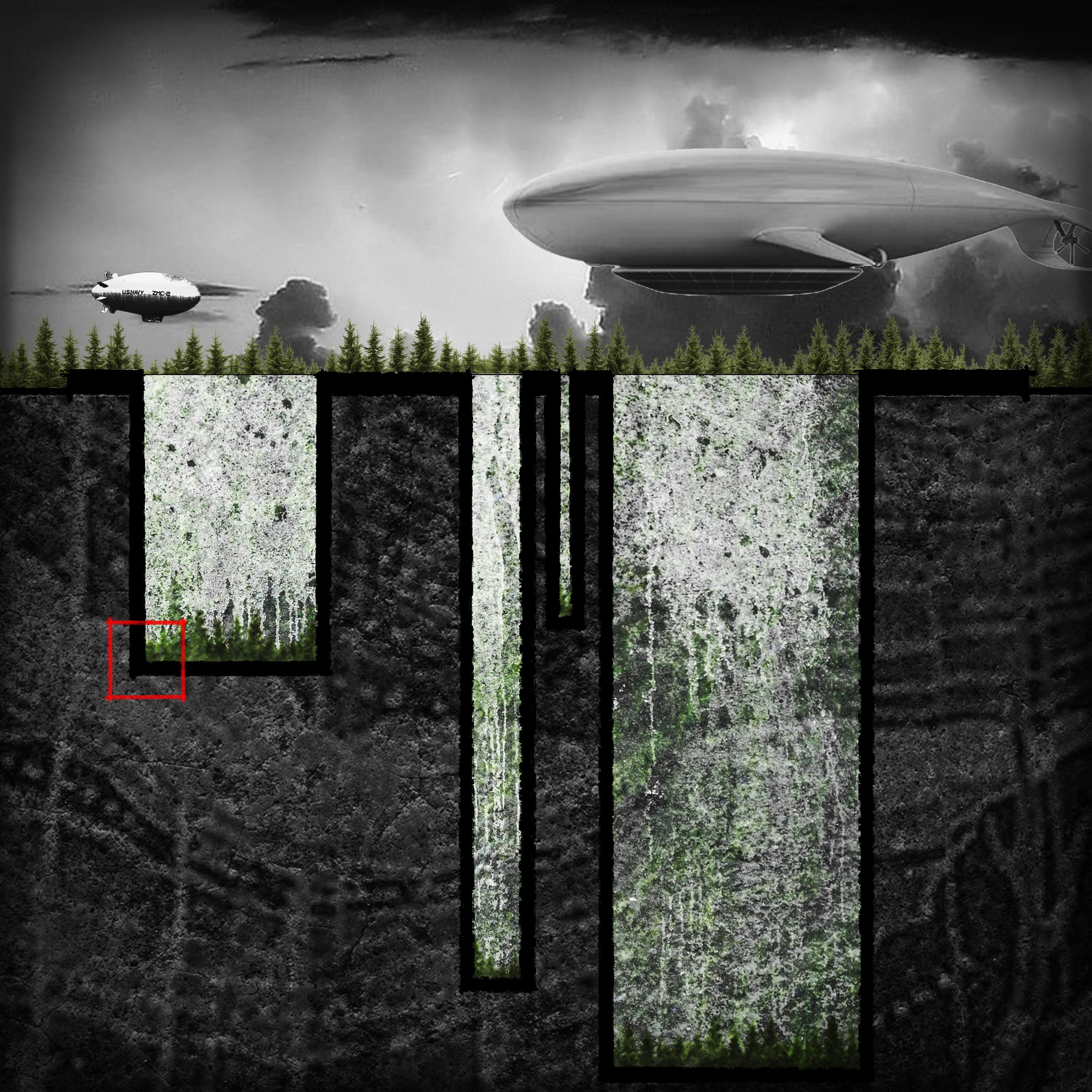

PATHFINDER 1, PROTOTYPE AIRSHIP

ATLAS 11 AIRSHIP, SIMULATION

LUXURY AIRSHIP, EUNOIA, 2024.

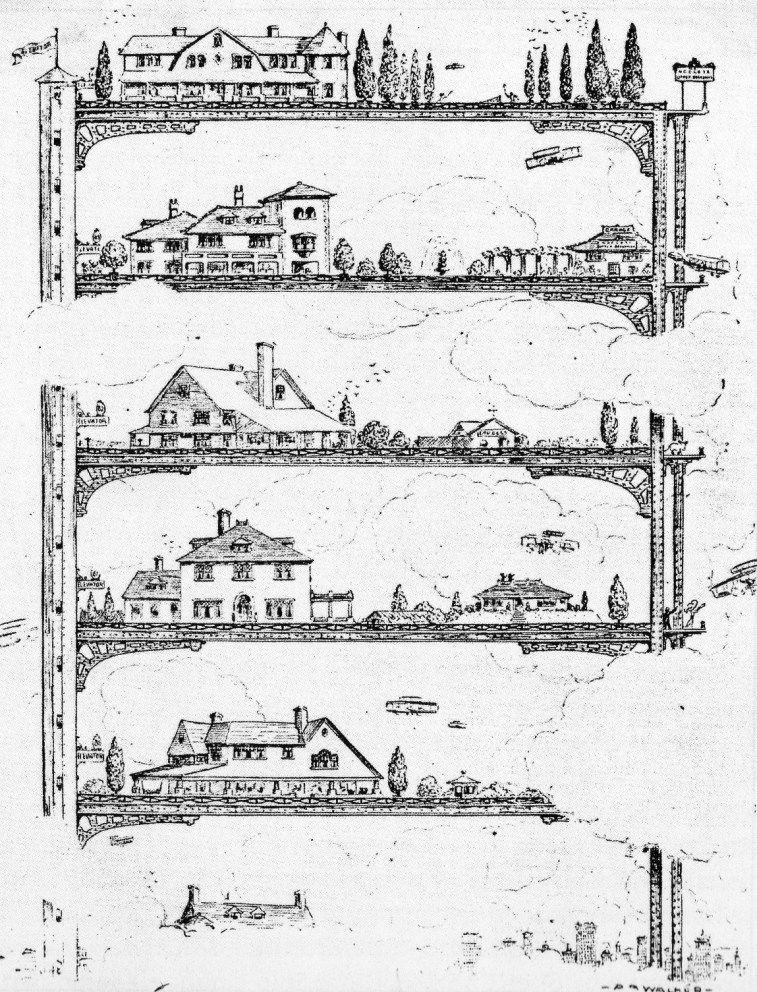

KOOLHAAS’ THEOREM

In Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas proposes a utopian city that embraces density, chaos, and complexity rather than traditional order. He argues that congestion is vital for fostering creativity and social interaction, viewing New York’s density as a catalyst for innovation.

Koolhaas advocates for vertical development with mixed-use skyscrapers, promoting programmatic mixing to allow diverse activities to coexist. He emphasizes the importance of adaptable spaces that can evolve over time, rejecting rigid ideological approaches to urban planning.

Ultimately, his vision celebrates the complexities of urban life, encouraging a vibrant, dynamic, and fluid urban experience.

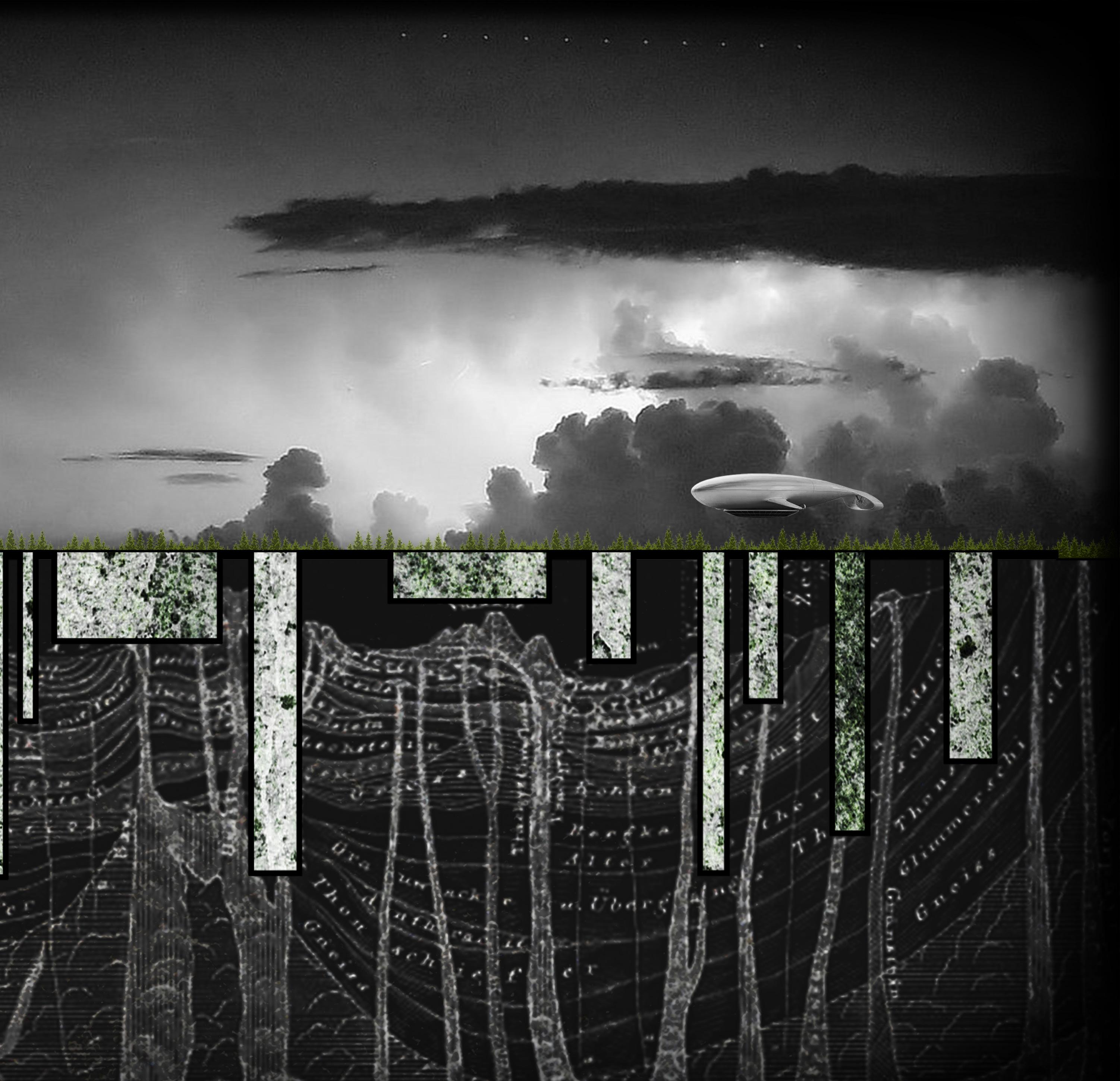

INVERSION + RENEWAL

WHERE ONCE SYSTEMS, GRIDS, TYPICAL WAYS OF DOING THINGS ONCE SERVED DETROIT WELL - THIS HAS CEASED TO FUNCTION.

WE LIVE IN A SCALELESS AGE - EVERYTHING IS INTERCONNECTED AT AN INTERNATIONAL LEVEL. WE CAN GO TO OUTER SPACE - THE FOREFRONT OF INFINITY.

CAN WE REDEFINE DETROIT THROUGH LIMITATIONS OF AREA, POPULATION, AND TRANSPORTATION? WHAT WOULD A SCALED-DOWN DETROIT LOOK LIKE? COULD THEY RELY SOLELY ON THE RENEWED NATURAL HABITATS THAT SURROUND THE CITY STRUCTURE?

ALLOWING DETROIT TO BE OVERGROWN, WILL RE-ESTABLISH NATIVE PLANT AND ANIMAL POPULATIONS. EXPIRED STRUCTURES WILL SERVE AS SANCTUARIES FOR NATIVE SPECIES. 100 YEARS IN THE FUTURE, REGROWN FORESTS WILL PROVIDE FOR MORE SUSTAINABLE BUILDING PRACTICES, AND ALLOW CITY RESIDENTS TO HAVE A SYMBIOTIC RELATIONSHIP WITH THE NATURAL WORLD.

THE INVERTED CITY WILL ISOLATE THE DENSE POPULATION WITHIN A FOREST, ALLOWING THOSE WHO LIVE THERE TO GROUND THEMSELVES IN NATURE WHICH WILL HAVE A SIGNIFICANT IMPACT ON THE THEIR WELL-BEING.

THE ELIMINATION OF CARS AND INTRODUCTION OF ZEPPELINS AS TRANSPORTATION WILL SLOW ACCESS TO THE CITY AND CREATE NEW RHYTHM OF LIFE - POLAR OPPOSITE TO THAT WE EXPERIENCE TODAY.

55