AframNews.com

“Addressing

Current & Historical Realities Affecting Our Community”

“Addressing

Current & Historical Realities Affecting Our Community”

By: Roy Douglas Malonson

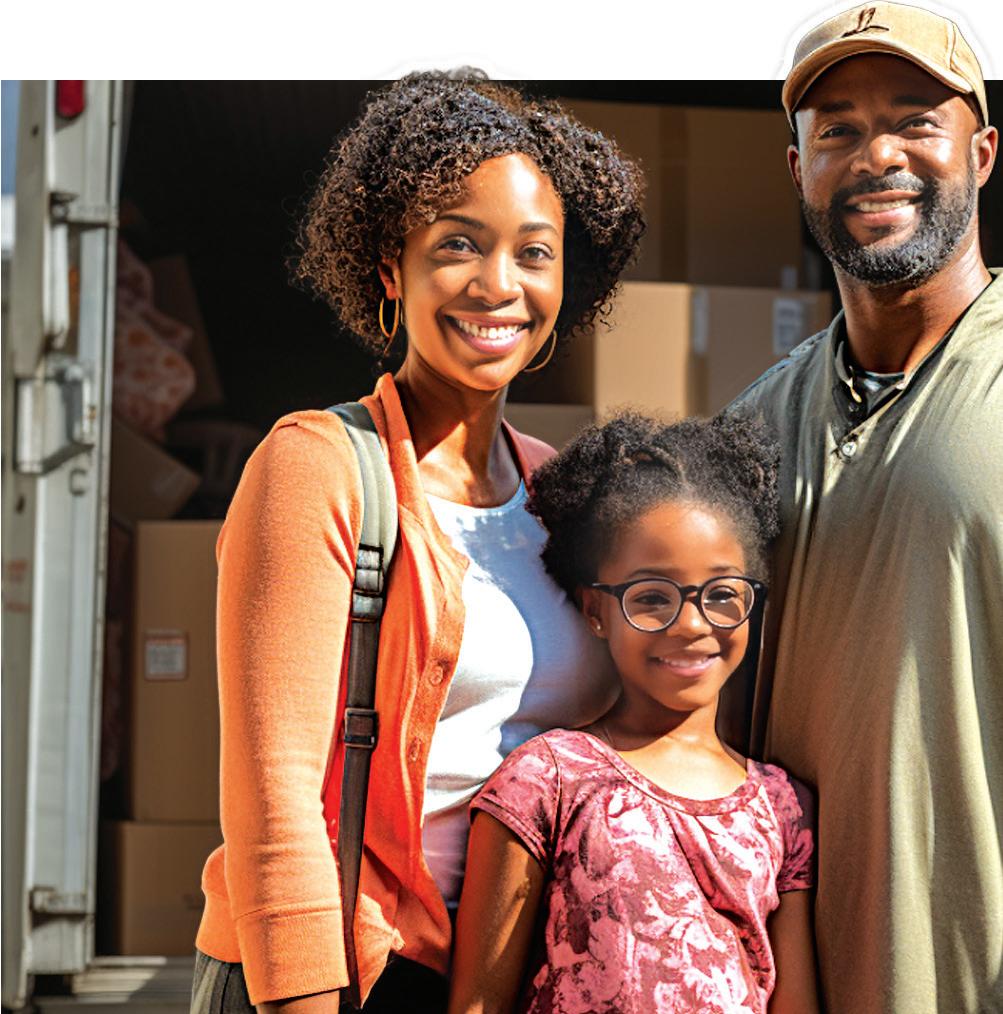

Harris County is at a turning point. For the rst time in several years, more people are moving out of the county than moving in, according to a new study that highlights a growing sense of uncertainty about long-term stability in the region. While Houston continues to attract newcomers overall, the data reveals a rising trend of domestic out-migration from both the city and the county, signaling deeper concerns about cost, safety, infrastructure, and quality of life that are in uencing residents across income levels and backgrounds.

One of the most signi cant factors driving this shi is ooding risk. e study shows that more than 31 percent of homes in Harris County are now classi ed as high ood risk, a gure that has become impossible to ignore a er years of severe weather events. Recent storms have le many homeowners facing repeated repairs, higher ood insurance premiums, and lingering anxiety about the next major rainfall. For families who have experienced ooding more than once, the question is no Harris County on pg. 3

TO TIRZS TOPS $200 MILLION

By: Bill King

Per the recently released City of Houston audit, the City’s contribution of property tax revenue to the TIRZs exceeded $200 million. at is the bad news. e good news is that the contribution was slightly lower than last year ($203MM → $201MM).

The City has increased its contributions to the TIRZs by nearly 50% since 2018. However, the other taxing entities participating in the TIRZs have steadily reduced their contributions.

I think there are two takeaways from these trends. First, the theory that the TIRZs are generating property tax values faster than the rest of the City, thus justifying their receiving preferential revenue, is breaking down. If the value of properties in the TIRZs were perpetually increasing faster than the City generally, then their increment should be steadily increasing. Many of the properties in the TIRZs are o ce buildings, whose value is under severe stress, and I suspect they will likely continue to drive TIRZ revenues down.

Second, it is interesting that taxing entities other than the City have been steadily reducing their participation. ere are likely two reasons for that. First, they see no bene t from their participation. Second, and probably more importantly, their taxpayers have not imposed a property tax revenue limitation, so they have no motivation to create a subterfuge to duck the taxpayers’ wishes.

Ironically, if the values in the TIRZs begin growing more slowly than the rest of the City, it will actually make the restrictions of the property tax cap more severe. Won’t that be poetic justice!

By Travis McGee

Here in Houston, Tx you would think drainage would be priority #1 other than crime however, on January 7,2026 some may consider the 9-7 vote to rob Peter to pay Paul to be a crime. is vote will take $30,000,000.00 from stormwater/ drainage to demo at least 350 abandoned/ dangerous buildings, or crack houses citywide, however most if not all of those buildings had drainage issues before they became blight in our communities.

We not saying we don’t won’t the buildings torn down, we just don’t want the city to use drainage money to do it. Just like the rest of Houston it’s a very good chance those buildings experienced previous ooding and

drainage issues in or around their neighborhoods/ communities due to various Flooding and storm events when they were occupied and not blighted.

e ooding, drainage, and infrastructure is so bad that in 2010 voters voted for a blank check aka” Rebuild Houston” which was said to be a dedicated drainage fund just as the Stormwater fund was said to be a dedicated fund to only be used for drainage, however Rebuild Houston was used for everything, but drainage.

We were told that it would be a Lock Box, but evidently too many people had the combination and keys to the Box that never stayed locked. Eventually Rebuild Houston aka Drainage Utility Fee ordinance was supposed to collect hundreds of millions annually and invest just as much or more back in to our drainage, infrastructure, and streets, however it ended up in court for doing the complete opposite. It paid more city debt than it invested

Bobby Mills, Ph.D.

e Trump Administration is boldly rationalizing, irrationality, and devilishly attempting to make wrong right, and make it work. As a result, American society is experiencing a signi cant nightmare, national governance crisis. e GOP, as a national party, lacks collective responsibility integrity and does not hold the President accountable. In fact, e GOP is allowing President Trump to ungodly believe that anything he does is constitutionally legal. Unfortunately, to America’s nation-state detriment the Supreme Court has also sanctioned this Presidential leadership approach to sanctioned this Presidential

nation-state democratic governance. What a disgraceful shame. Ownership belongs to God, because: “the earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein”. (Psalm 24:1). us, stewardship collective responsibility belongs to every American. America, even though, we are in a national nightmare, because President Trump believes that everything he says, and does is legal, we can imitate King David and boldly declare: “O Lord do I li up my soul…. shew me thy ways, O Lord; teach me thy paths. Lead me in thy truth, and teach me: for thou art the God of my salvation: on thee do I wait all the day.” (Psalm 25: 1,4-5). America, because the earth is the Lord’s, all of us are stewards and caretakers. Sadly, President Trump and e GOP MAGA-Cult

Irrationality on pg. 3

Harris County Cont.

longer if it will happen again, but when. at uncertainty is pushing residents to reconsider whether remaining in ood-prone areas makes nancial or emotional sense.

Extreme weather has also exposed concerns about infrastructure reliability. Power outages following major storms have disrupted daily life for hundreds of thousands of residents, sometimes lasting days. For seniors, families with young children, and those managing health conditions, these outages pose serious safety risks. For working households, unreliable electricity interrupts jobs, schooling, and access to essential services. Over time, repeated failures erode con dence in the systems meant to support a growing population, making relocation feel like a practical response rather than a drastic one.

Rising living costs add further pressure. Home prices in Harris County have climbed steadily, while property taxes and insurance premiums continue to increase. Renters are facing higher monthly costs as well, limiting their ability to save or plan for the future. For many residents, wages have not kept pace with these increases, creating a growing gap between income and the true cost of staying. What once felt a ordable now feels increasingly out of reach, particularly for middle- and workingclass families trying to

maintain stability. ese economic pressures are not new, but their cumulative e ect is becoming harder to manage. Communities that historically faced underinvestment are o en the same areas dealing with higher ood risk and older infrastructure, compounding the challenges residents face. African American families, along with other long-established communities, o en feel these pressures more acutely due to generational disparities in home equity, insurance access, and recovery resources a er disasters. While the trend a ects residents broadly, its impact is uneven, shaped by history as much as by present-day conditions. As some residents leave Harris County, many are not leaving the region entirely. Instead, they are relocating to surrounding suburban counties perceived as safer or more predictable. Montgomery County, for example, has seen a signi cant in ux of new residents, driven largely by lower ood risk and newer infrastructure. However, this outward movement raises important questions about access and a ordability. As suburban areas grow, housing prices rise, and long-time residents in those communities may face displacement of their own, continuing a cycle that reshapes the region.

Political and social

preferences are also in uencing decisions. Some residents cite a desire for di erent governance, policies, or community environments as part of their reasoning for moving. While these preferences vary, they re ect a broader search for places where people feel heard, supported, and con dent in the direction of local leadership. For many, relocation is not about abandoning Houston, but about nding alignment between personal values and daily living conditions. e growing outmigration trend does not mean Harris County is declining, but it does signal a warning that growth alone is not enough. Residents are weighing risk, cost, and reliability more carefully than ever before. e data captures movement, but behind each move is a household making a calculated decision about safety, nances, and future opportunity. Ultimately, the question facing Harris County is not simply why people are leaving, but what must change to make staying a sustainable choice. Addressing ooding, infrastructure resilience, housing a ordability, and longstanding inequities will determine whether the county can retain the diverse communities that have shaped its identity and fueled its growth for generations.

falsely believe that the earth belongs to them. In e Gospel of Luke (chapter 12:16-21) the parable of a rich barn builder is told: “ e ground of a certain rich man brought forth plenty: and he thought to himself, saying What shall I do, because I have no room where to store my fruits? And he said this I will do: I will pull down my barns, and build greater; and there I will bestow all my fruits and goods. And I will say to my soul. Soul, thou hast much goods laid up for many years; take thine ease, eat, drink, and be merry. But God said unto him, ou fool, this night thy soul shall be required of thee: then whose shall those things be, which thou has provided? in any drainage. How can a city that has seen some of the worst Floods and storms in America’s history not make drainage priority and invest more money in drainage and infrastructure. Houston has 3,300 miles of storm sewer, 6,000 miles of streets, 2,800 miles of roadside ditches, and 22 bayous making up 2,500 miles.

Now that’s a lot of drainage not to be priority considering we will ood due to just a simple rain event vs a natural disaster event. We also know that illegal dumping is a problem, however

So is he that layeth up treasure for himself, and is not rich toward God.” (Luke 12: 16-21). e rich man only thought about sel sh hoarding, not sharing.

America is experiencing a unique constitutional moment, because President Trump asserts that all his actions and statements are always legal. When, in fact, everything the Trump Administration does is immoral, illegal, and undermines the leadership moral-integrity and democratic authority of America in the world community. What a disgraceful shame!

Sadly, President Trump’s leadership mentality is institutionalizing and normalizing governmental corruption. Consequently, America is experiencing both the

not enforcing illegal dumping to the fullest extent of the law is an even bigger problem.

e city staying behind on heavy trash pickup contributes to illegal dumping, but saying that dangerous buildings attract illegal dumping and tearing the building down improves drainage is farfetched. We not Redlined due buildings, but we are Redlined due to FLOODING. Insurance premiums are either raised or the insured dropped all together and coincidently your property taxes aren’t concerned by how many blighted buildings in your area either.

If the decisions like this

Read more at

BIG RIP-OFF as well as the BIG PAY-BACK. e key spiritual and moral issue is how we choose to live. Lying and hating on one another is not living. King David found the secret to a Joy. King David found out that true joy is spiritually deeper than temporal happiness this is limited by time, because the joy that God gives is eternal. e world did give it, and the world cannot take it away. Praise God! Hence, King David wrote: “ ou wilt shew me the path of life: in thy presence is fullness of joy; at thy right hand there are pleasures for evermore.” (Psalm 16: 11). Glory Hallelujah To e King of Kings. have to be made, they should be made by the taxpayers because at the end of the day when, not if the next Flood come, they will have to be HOUSTON STRONG a er being told to call 311 and turn around don’t drown.

An article published on January 16, 2025 titled “Should the City Use Stormwater Funds to Demolish Abandoned Buildings?” incorrectly listed the writer credit. e article was written by Bill King, not Travis McGee. We regret the error and apologize to our readers and to the writer for the mistake.

1955 1957 1963 1960 1964 1960 1963

December 1, 1955: Rosa Parks refuses to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. Her de ant stance prompts a year-long Montgomery bus boycott.

January 10-11, 1957: Sixty Black pastors and civil rights leaders from several southern states— including Martin Luther King Jr.—meet in Atlanta, Georgia to coordinate nonviolent protests against racial discrimination and segregation.

July 2, 1964: President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, preventing employment discrimination due to race, color, sex, religion or national origin.

May 2, 1963: More than 1,000 Black school children march through Birmingham, Alabama in a demonstration against segregation. e goal of the non-violent demonstration, which became known as the “Children’s Crusade,” was to provoke the city’s leaders to desegregate.

February 1, 1960: Four African American college students in Greensboro, North Carolina refuse to leave a Woolworth’s “whites only” lunch counter without being served. e Greensboro Sit-In, as it came to be called, sparks similar “sitins” throughout the city and in other states.

November 14, 1960: Six-year-old Ruby Bridges is escorted by four armed federal marshals as she becomes the rst student to integrate William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans. Her actions inspired Norman Rockwell’s painting e Problem We All Live With (1964).

June 11, 1963: Governor George C. Wallace stands in a doorway at the University of Alabama to block two Black students from registering. e stando continues until President John F. Kennedy sends the National Guard to the campus.

A gas pipeline operator has agreed to pay **$1.425 million** to settle federal allegations that safety violations contributed to the death of an employee in 2020, who was fatally struck by a dislodged cleaning tool. The company stated that it cooperated fully with the investigation and has since implemented enhanced safety protocols and training measures.

Hamilton ISD recognized its 2025 Class 2A Division I state champion football team during a victory bell ceremony, with a championship parade scheduled for Wednesday evening.

Houston Congressman Wesley Hunt is seeking to secure support from Lubbock voters in the upcoming primary election.

Southstar, a New Braunfels–based developer, purchased the Lone Star property in San Antonio. The Lone Star Brewery site is a historically significant industrial property in San Antonio that has long been viewed as a key opportunity for large-scale redevelopment and adaptive reuse.

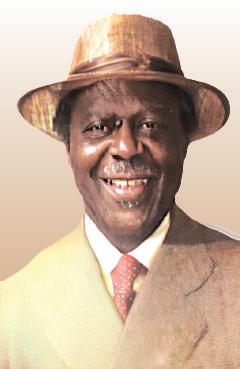

Family members, friends, and community residents gathered Wednesday to commemorate the life and legacy of Tommy Lee Wyatt, who died earlier this month at the age of 88.

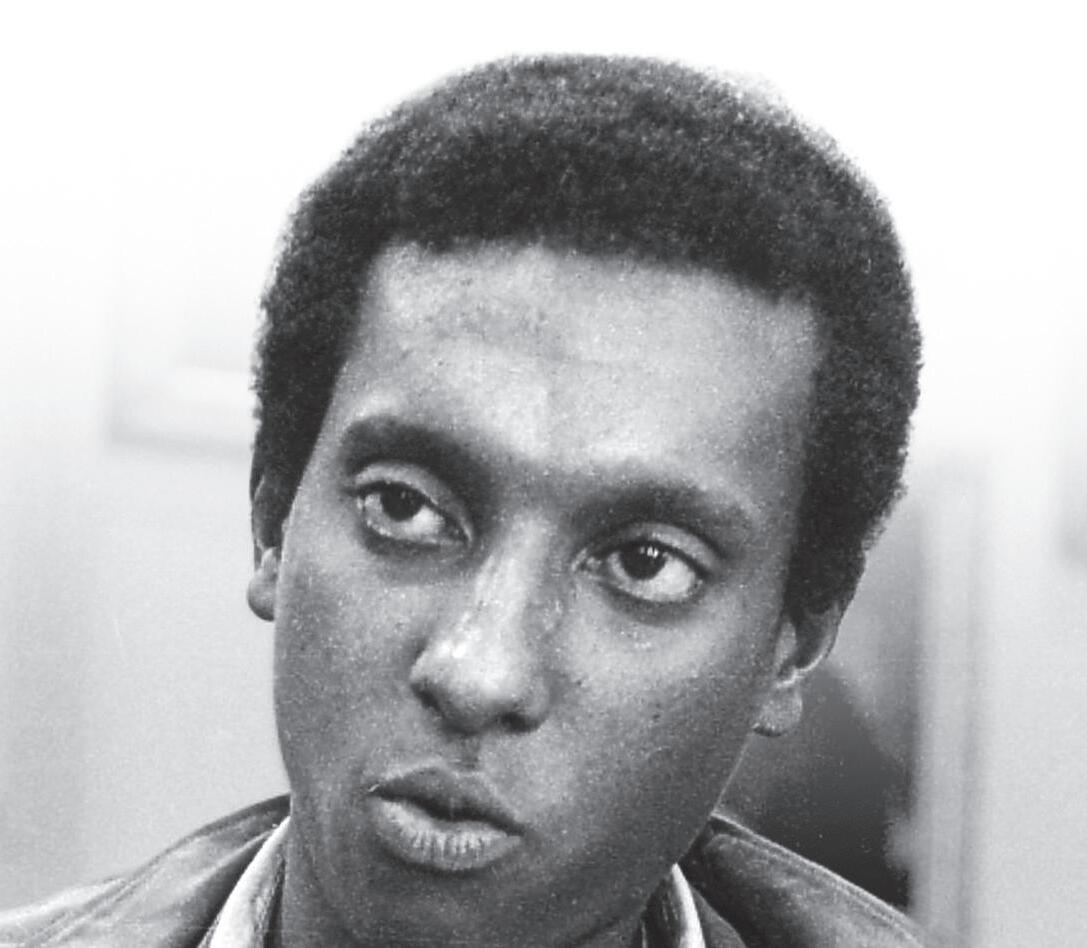

Stokely Carmichael (1941–1998), later known as Kwame Ture, was a prominent Trinidadian-American activist who fundamentally reshaped the U.S. civil rights movement in the 1960s. He is most famous for popularizing the slogan “Black Power” and for leading the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) toward a more militant, separatist ideology.

By: Fred Smith

H-E-B’s rise to the top as Texas’ No. 1 grocery chain and America’s best supermarket is the result of decades of customer-focused innovation, community commitment, and operational excellence. Founded in 1905 in Kerrville, Texas, H-E-B has grown from a small family-owned store into a retail powerhouse while maintaining a distinctly local

re ects not just consistent

of the communities it serves.

performance across quality, value, and customer trust. One of the biggest reasons H-E-B stands out is its deep understanding of Texas shoppers. Unlike many national chains, H-E-B tailors its stores to the speci c tastes of the communities it serves. Product selections vary by region, with shelves stocked for local cultures, cuisines, and preferences—from South Texas Mexican staples to Hill Country favorites. is localization customers feel seen and valued, turning routine grocery trips into a more personal

Product selections vary by region, with shelves stocked for local cultures, cuisines, and preferences—from South makes

rival or exceed national brands in quality while remaining more a ordable. From H-E-B Organics to Hill Country Fare and Central Market lines, the company invests heavily in product development and quality control. Shoppers consistently report high satisfaction with these store-brand items, reinforcing the perception that H-E-B delivers exceptional value without compromising standards. Customer service plays a central role in H-E-B’s top ranking as well. Employees— referred to as “Partners”—are known for their friendliness, e ciency, and willingness to help. e company’s strong workplace culture translates directly to the shopping experience, as motivated employees create cleaner stores, faster checkouts, and more attentive service. is human connection sets H-E-B apart in an increasingly automated retail landscape.

Beyond the aisles, H-EB’s commitment to Texas communities strengthens its

reputation nationwide. e company is highly visible in disaster relief e orts, education initiatives, and hunger relief programs. When hurricanes, freezes, or other emergencies strike, H-E-B is o en among the rst to respond with supplies and support. is reliability has earned deep loyalty from Texans, who see the brand as more than just a grocery store. Ultimately, H-E-B’s ranking as America’s best supermarket re ects a rare balance of scale and heart. While it operates hundreds of stores and competes with national giants, it has never lost sight of its core values: quality, service, and community. For Texans, H-E-B is a point of pride; for the rest of the country, its success serves as a model for what modern grocery retail can achieve when customers truly come rst.

H-E-B’s history begins in 1905, when Florence Butt opened a small grocery store on the ground oor of her family home in Kerrville, Texas. With just $60 in startup money, she focused on fair prices, honest dealings, and personal service—principles that still guide the company today. Her son, Howard E. Butt, for whom the company is named, later took over the business and began expanding it beyond its original location. Under Howard E. Butt’s leadership in the 1920s and 1930s, H-E-B embraced innovation early. e company was one of the rst grocery chains in Texas to adopt self-service shopping,

replacing clerk- lled orders with aisles customers could browse themselves. is shi improved e ciency and convenience, helping H-E-B grow steadily during a time when many small grocers struggled to survive.

e mid-20th century marked a major expansion period for H-E-B as it moved into larger Texas cities, including San Antonio, Austin, and Houston. Even as it expanded, the company remained family-owned and Texas-based, avoiding the pressure to become a national chain. is independence allowed H-E-B to make long-term investments in infrastructure, distribution, and employee development, setting the foundation for its modern success.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, H-E-B continued evolving with the times by launching Central Market, an upscale specialty grocery concept, and later expanding into e-commerce, curbside pickup, and home delivery. roughout more than a century of change, the company has remained guided by the Butt family and its original mission. at continuity—blending tradition with innovation— has been key to H-E-B’s enduring reputation and its rise to the top of the American grocery industry.

By: Jamal Carter

In 1865, the United States Congress passed the irteenth Amendment to the Constitution, a landmark moment in the nation’s history. is action came near the end of the Civil War, at a time when the country was deeply divided but increasingly aware that slavery—the institution at the heart of the con ict—had to be permanently abolished. Although President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, that order applied only to states in rebellion and was considered a wartime measure, not a lasting constitutional guarantee.

e irteenth Amendment went further by seeking to eliminate slavery everywhere in the United States. Its

key language declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime,” would exist within the nation. By embedding this principle in the Constitution, Congress aimed to ensure that slavery could not be restored once the war ended, regardless of changes in political leadership or court rulings. e vote in Congress was hard-fought, especially in the House of Representatives, where a two-thirds majority was required. Debates were intense, re ecting long-standing political, moral, and economic divisions. Some lawmakers opposed the amendment on constitutional or racial grounds, while others feared its impact on Southern society.

By: Roy Douglas Malonson

Supporters, including Lincoln and many abolitionists, argued that the nation could not truly reunite without formally rejecting slavery.

e passage of the amendment represented a signi cant shi in federal authority. For the rst time, the Constitution explicitly empowered the federal government to protect freedom by prohibiting slavery nationwide. is marked a departure from earlier compromises that had allowed slavery to persist in certain states and territories. It also signaled a new understanding of liberty as a national value rather than a matter le to individual states.

When Texas Governor

Greg Abbott set a January 31 runo election to replace longtime U.S. Rep. Sylvester Turner, it quietly con rmed something many African American voters in Houston already felt — our political representation is once again being treated as optional, delayed, and expendable. Addressing Current & Historical Realities Affecting Our Community. e Houston-based congressional seat has now gone nearly a year without representation in Washington. Eleven months without a vote in Congress is not a procedural hiccup; it is a policy decision with real consequences. During that time, Congress has debated and voted on federal budgets, disaster relief, healthcare funding, housing policy, infrastructure investments, and foreign aid — all without a voice from one of the most diverse and economically vulnerable districts in Texas. For Black communities in Houston, this absence is especially costly. Representation is not symbolic. It is practical power. It is someone advocating for ood mitigation dollars a er repeated storms, pushing back against cuts to healthcare access, ghting for fair

housing, and ensuring federal resources reach neighborhoods that have historically been underfunded and overpoliced. When that seat is empty, those priorities fall to the bottom of the stack.

e timing of the runo has raised di cult but necessary questions. Why did it take so long to schedule a decisive election? Why must voters wait nearly a year to restore representation that should have been immediate? And why does this pattern seem to repeat itself most o en in districts with large Black and Brown populations?

is delay is not occurring in a vacuum. Texas has a long history of political maneuvering that indirectly suppresses turnout and in uence — from restrictive voting laws to election timing that favors low participation.

Special elections and runo s held outside of major election cycles o en see dramatically reduced voter turnout, particularly among working-class voters who face transportation, scheduling, and information barriers.

e result is predictable: fewer voices heard, and outcomes shaped by a smaller, less representative slice of the electorate.

e legacy of Sylvester Turner matters here. His career represented continuity, advocacy, and institutional knowledge for Houston at the federal level. Replacing that kind of leadership requires urgency, transparency, and respect for the district’s voters. Instead, what residents have experienced is silence — from Washington and, too o en, from state leadership. is moment should serve as a wake-up call, not just about one seat, but about how political power is managed in Texas. When representation gaps are allowed to stretch for nearly a year, it sends a message about whose voices can be paused and whose cannot. It reinforces a dangerous normalization of absence — the idea that Black communities can wait while decisions are made without them. Yet, history also shows that moments like this can become turning points. Runo elections may be quieter, but they are no less consequential. e January 31 runo is not merely about lling a vacancy; it is about reclaiming a voice that should never have been

H-E-B was founded on the unwavering belief that Each and Every Person Counts.

H-E-B is committed to supporting education and inclusion across our great state.